Abstract

Cooperative pursuit using multi-UAV systems presents significant challenges in dynamic task allocation, real-time coordination, and trajectory optimization within complex environments. To address these issues, this paper proposes a reinforcement learning-based task planning framework that employs a distributed Actor–Critic architecture enhanced with bidirectional recurrent neural networks (BRNN). The pursuit–evasion scenario is modeled as a multi-agent Markov decision process, enabling each UAV to make informed decisions based on shared observations and coordinated strategies. A multi-stage reward function and a BRNN-driven communication mechanism are introduced to improve inter-agent collaboration and learning stability. Extensive simulations across various deployment scenarios, including 3-vs-1 and 5-vs-2 configurations, demonstrate that the proposed method achieves a success rate of at least 90% and reduces the average capture time by at least 19% compared to rule-based baselines, confirming its superior effectiveness, robustness, and scalability in cooperative pursuit missions.

1. Introduction

Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) have emerged as indispensable assets across military and civilian applications, leveraging their high mobility, rapid deployment, and operational flexibility [1,2,3]. In particular, cooperative multi-UAV systems have attracted significant research interest due to their capability to execute complex missions—including surveillance [4], search and rescue [5], environmental monitoring [6], and target interception [7]. Within this context, multi-UAV cooperative pursuit and interception represent a critical class of adversarial scenarios, requiring seamless collaboration among UAVs to jointly detect, track, and capture unauthorized intruders within a constrained airspace [8,9]. The inherent challenges of dynamic target behavior, real-time decision-making, and stringent coordination underpin the pressing need for advanced planning frameworks capable of ensuring mission success in such high-stakes environments.

Traditionally, multi-UAV pursuit tasks have been tackled through centralized optimization or handcrafted rule-based strategies. Optimization approaches, such as discrete particle swarm optimization (PSO) used by Guo et al. [10] for task allocation, often depend on static inputs like shortest paths and struggle in dynamic environments. Xiong et al. [11] improved task-path integration via an alternating iterative framework combining coalition formation and enhanced PSO, yet the method remains limited in real-time responsiveness. To better handle uncertainty and decentralization, distributed models have been explored. Bernstein et al. [12] proposed a distributed Markov Decision Process (MDP) formulation for decentralized planning, though it faces scalability issues due to exponential state-space growth. In pursuit–evasion settings, metaheuristic algorithms such as the discrete PSO by Souidi et al. [13] enable dynamic coalition formation but rely on pre-specified evader behaviors. Chi et al. [14] developed a differential game-based interception strategy offering precision in single-target scenarios but poor generalization to multi-agent tasks. Fuzzy decision-making models, such as that of Li et al. [15], facilitate threat assessment yet lack adaptability in rapidly changing conditions. Hyper-tangent PSO (HT-PSO) by Haris et al. [16] accelerates convergence but does not explicitly model inter-agent coordination. Huang et al. [17] introduced a hierarchical probabilistic graph framework that supports self-organization but depends on predefined graph templates, limiting flexibility.

In summary, existing methods fall into two categories: (i) centralized or heuristic optimization, which offer computational efficiency but poor adaptability; and (ii) game-theoretic and distributed planning, which improve coordination but suffer from scalability constraints and limited real-time capability.

Reinforcement Learning (RL), and particularly Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning (MARL), has emerged as a powerful paradigm for autonomous decision-making in dynamic and uncertain environments. Existing MARL approaches can be broadly categorized into several groups. Hierarchical methods, such as the framework by Banfi et al. [18] that combines graph neural networks with mixed-integer programming, improve modularity but often rely on static structures that limit adaptability. Interaction-based methods, including the proposer-responder mechanism with experience replay by Liu et al. [19], enhance coordination but lack implicit communication capabilities, reducing effectiveness in large-scale settings. Digital twin-assisted approaches, like that of Tang et al. [20], improve physical consistency but often overlook collaborative behavior under adversarial conditions. Similarly, Liu et al. [21] proposed an adaptive task planning method (AMCPP) aimed at minimizing flight time and path length, but the method assumes fully observable environments and lacks robustness in partially observable or adversarial contexts. Zhao et al. [22] modeled multi-UAV task planning as a multi-traveling salesman problem and applied MARL to jointly optimize task assignment and trajectory generation. While effective for basic deconfliction and resource distribution, the approach does not explicitly consider adversarial dynamics or coordinated interception. Chi et al. [23] extended deep RL to integrate trajectory design, resource scheduling, and task allocation. Although comprehensive, their model complexity hinders real-time deployment and scales poorly in high-dimensional mission spaces. Decentralized frameworks have also been studied to address observability and communication limitations. Huang et al. [24] and Yang et al. [25] formulated task planning as decentralized partially observable MDPs (Dec-POMDPs) and proposed scalable MARL-based solutions. These models improve policy generalization under uncertainty but often suffer from unstable convergence due to communication sparsity and delayed feedback. To enhance information representation, Du et al. [26] embedded graph neural networks into distributed learning frameworks, improving structural awareness but lacking explicit temporal modeling. Chen et al. [27] introduced a Transformer-based MARL architecture for long-horizon trajectory planning, which improves temporal reasoning but increases computational complexity. Liu et al. [28] proposed GA-MASAC-TP Net, combining graph attention and trajectory prediction into an actor–critic framework. Although effective in adversarial coordination, it lacks structured communication between agents and does not explicitly address role-based cooperation. Bai et al. [29] proposed a Q-learning-based region coverage algorithm in a discrete setting, tailored to the 3-vs-1 interception problem in 3D space. Their method introduces the Ahlswede ball model to design cooperative interception zones and proves convergence using a Lyapunov function. Although the Q-learning-cover strategy simplifies coordination through region partitioning, its performance heavily relies on spatial symmetry assumptions and lacks generalization to heterogeneous team sizes or dynamic environments.

In summary, existing RL-based approaches for multi-UAV coordination can be broadly classified into three categories: (i) hierarchical or modular frameworks, which enhance scalability at the expense of flexibility in dynamic coordination; (ii) communication-sparse Dec-POMDP models, which accommodate environmental uncertainty but often exhibit unstable training convergence; and (iii) advanced neural architectures such as GNNs and Transformers, which improve spatiotemporal representation learning yet introduce considerable computational overhead and reduce interpretability.

While several communication mechanisms have been proposed in MARL literature, our BRNN-driven approach distinguishes itself in both architectural design and functional efficacy. CommNet [30] employs a continuous communication channel through averaging, enabling basic information sharing but lacking structured interaction and contextual awareness. IC3Net [31] introduces gated mechanisms for intermittent communication, improving adaptability at the cost of limited temporal consistency. DGN (Deep Graph Network) [32] leverages graph neural networks to model agent relationships, but relies on predefined or dynamically constructed graphs that may not generalize well in highly adversarial settings. MAAC (Multi-Actor Attention Critic) [33] utilizes attention mechanisms to weight inter-agent messages, boosting focus on relevant inputs but incurring significant computational overhead. Our BRNN-driven communication mechanism captures bidirectional temporal dependencies without presuming interaction structures, enabling persistent, context-aware coordination while maintaining decentralized execution and training stability.

To overcome these limitations and address the critical challenges of dynamic task allocation, real-time coordination, and trajectory optimization in adversarial multi-UAV environments, this paper proposes a novel communication-aware multi-agent reinforcement learning framework for cooperative pursuit planning. Our approach centers on a distributed decision-making model in which each UAV operates as an autonomous agent, augmented with a structured communication mechanism via a bidirectional recurrent neural network (BRNN) [34]. This architecture enables UAVs to selectively share policy-relevant features and intentions while preserving decentralized control, thereby significantly enhancing joint policy stability and collective coordination efficacy without compromising operational autonomy. The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

- A multi-UAV cooperative pursuit problem is formally modeled as a multi-agent Markov Decision Process (MDP) within a 3D bounded environment, explicitly capturing the dynamic interactions between pursuers and evaders under realistic kinematic and spatial constraints;

- A comprehensive state–action representation is introduced, incorporating a structured observation space, a continuous control action space, and a novel multi-stage reward mechanism. This design promotes efficient target tracking, phased proximity convergence, and final interception success through dense and interpretable feedback;

- A communication-aware multi-agent reinforcement learning architecture enhanced with bidirectional recurrent neural networks (BRNNs) is proposed. This structure facilitates inter-agent policy alignment and context-aware decision-making, significantly improving coordination stability and adaptation capability in highly dynamic and adversarial pursuit scenarios.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 formulates the cooperative pursuit problem within a multi-agent Markov decision process framework, including the definitions of the state space, action space, and reward mechanism. Section 3 presents the proposed multi-agent reinforcement learning framework with BRNN-based communication and coordination strategies. Section 4 provides simulation experiments under various pursuit scenarios and evaluates the performance of the proposed algorithm. Finally, Section 5 summarizes the key findings and outlines future research directions.

2. Problem Formulation

2.1. Cooperative Pursuit Scenario Description

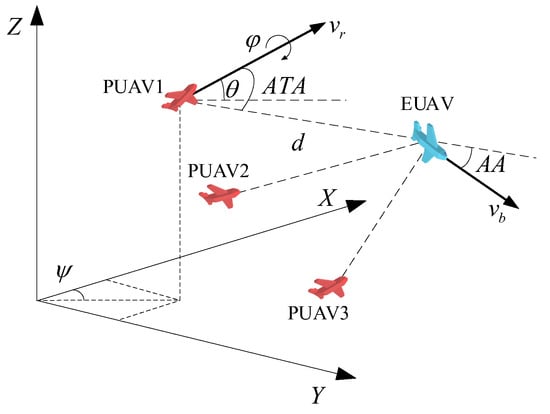

We consider a three-dimensional cooperative pursuit scenario involving multiple UAVs engaged in an interception task. The operational environment is a bounded 3D space, free of static obstacles, where several evading UAVs (EUAV) intrude into a restricted airspace and attempt to escape. A group of pursuing UAVs (PUAV) is deployed near the boundaries and must collaboratively intercept the intruders through coordinated maneuvering. Figure 1 illustrates a typical 3-vs-1 cooperative pursuit scenario in 3D space, with the evader (blue) attempting to escape while three pursuers (red) coordinate to intercept.

Figure 1.

3D cooperative multi-UAV pursuit scenario with one evader (blue) and three pursuers (red).

The relative distance between a pursuer and the evader is denoted by d, and the velocities of the pursuer and the evader are denoted as and , respectively. Each agent’s orientation in space is described using Euler angles: roll (), pitch (), and yaw (). Angle-to-Approach (ATA) is the angle between the pursuer’s velocity vector and the line-of-sight vector. Aspect Angle (AA) is the angle between the evader’s velocity vector and the line-of-sight vector.

The pursuit task is adversarial in nature, where the pursuers aim to minimize the escape success of the evaders while maintaining coordination and efficiency. Each pursuer must dynamically select its trajectory based on the evolving positions of the targets and its own teammates. The scenario is symmetric in capability—both teams are assumed to have similar mobility characteristics such as maximum speed, acceleration, and turn rate.

The success conditions for the task are defined as follows:

- Successful capture: An evading UAV is considered intercepted if it enters the capture radius of a sufficient number of pursuing UAVs simultaneously.

- Successful escape: An evading UAV is said to escape successfully if it leaves the boundary of the restricted zone without being intercepted.

2.2. Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning Framework for Cooperative UAV Pursuit

To enable efficient coordination among multiple UAVs in adversarial environments, a MARL framework tailored for cooperative pursuit tasks is adopted. A multi-agent system (MAS) consists of multiple intelligent agents operating in a shared environment, each capable of making decisions based on local observations and learning from experience. MARL extends traditional reinforcement learning by allowing agents to interact not only with the environment but also with one another, learning decentralized policies that lead to joint task success.

A key challenge in MARL is the non-stationarity of the environment. From the perspective of a single agent, the environment appears dynamic and unpredictable because the behaviors of other agents are constantly changing. If each agent learns independently without communication, it may treat the actions of others as external noise, leading to unstable convergence and poor coordination. This severely limits the scalability and effectiveness of MARL in complex, multi-agent missions.

To address the challenges of inefficient coordination and limited situational awareness in multi-UAV systems, we incorporate an inter-agent communication mechanism into the learning process. Through structured message exchange channels, each UAV agent can access relevant state or policy information from teammates, thereby enhancing situational awareness and coordination. This communication-aware structure mitigates the impact of non-stationarity and accelerates the convergence of cooperative strategies.

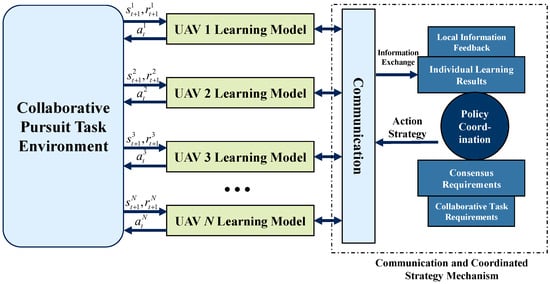

Building on these principles, a distributed MARL framework for cooperative UAV pursuit is designed, as shown in Figure 2. Each pursuing UAV is modeled as an independent learning agent, with a local policy network grounded in its kinematic control model and a shared state encoding format, where represents the state of UAV i at time t, represents the action, and represents the reward. Agents exchange intermediate features or policy parameters through the communication channel, forming a joint decision system.

Figure 2.

Communication-aware MARL framework for cooperative multi-UAV pursuit.

To further enhance team performance, we integrate a strategy coordination module into the framework. This module aligns tactical behaviors across the UAV team, enabling real-time encirclement, multi-target assignment, and spatial coverage. It jointly considers agent autonomy and collective objectives, supporting robust decision-making under adversarial conditions.

2.3. Problem Formulation via Markov Decision Process

The cooperative pursuit task among multiple UAVs is formulated as a Markov Decision Process (MDP), which provides a formal framework to describe the interaction between agents and their environment. The MDP includes the observation structure, action space, reward function, and transition dynamics, which collectively define the decision-making process for each UAV agent. To simplify the learning process and focus on the exploration of cooperative strategies, we assume that the environmental dynamics are deterministic. Specifically, the state transition function is deterministic, meaning that given the current state and joint action, the next state is determined by a deterministic kinematic model. This assumption has been widely adopted in UAV motion planning research and effectively supports the training of algorithms.

2.3.1. Observation Space

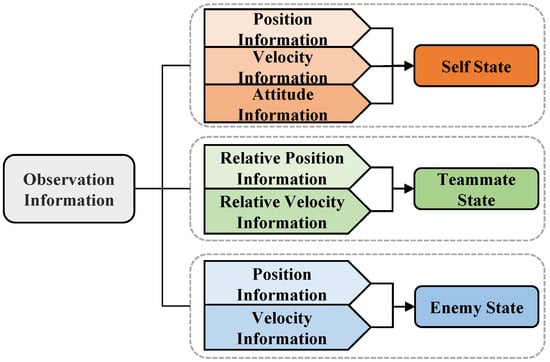

In MARL, the quality of state observations plays a critical role in policy effectiveness and learning convergence. Under partial observability constraints, each UAV agent relies on local perception centered on its nearest evader, including relative angle, distance, and velocity measurements. This limited observation scope requires agents to learn effective coordination strategies despite incomplete global information. To accurately represent the environment and facilitate multi-agent coordination, the observation for each UAV is structured into three components:

- Self-state: The UAV’s current position, velocity, and attitude information;

- Relative state of allies: Relative positions and velocities of other friendly UAVs;

- Relative state of enemies: Relative positions and velocities of enemy UAVs.

As illustrated in Figure 3, the self-state forms the basis of each agent’s awareness, and relative observations enhance spatial coordination. To ensure numerical stability and improve generalization, all relative vectors are normalized.

Figure 3.

Composition of UAV observation information in the cooperative pursuit task.

The self-state vector is defined as:

where are the 3D position coordinates of the UAV in the global coordinate system, is the roll angle representing the rotation around the UAV’s body axis, is the pitch angle representing the rotation around the lateral axis of the UAV, and v is the velocity of UAV.

For the relative information between agent i and its teammate j, the relative position and velocity are computed as:

where , , and denote the normalized relative position components along the x, y, and z axes, respectively; represents the normalized relative distance between UAV i and UAV j with respect to the capture threshold ; and is the normalized relative velocity between the two UAVs based on the maximum UAV speed . The variables , , and , , denote the 3D coordinates of UAV i and UAV j, respectively, while and are their respective velocities.

Similar equations are applied to compute the relative state between UAV i and an enemy target k. These normalized features form the complete observation input for each agent, enabling the policy network to accurately infer spatial relations and adjust actions accordingly.

2.3.2. Action Space

In the MARL framework, the action space defines the set of all possible control inputs an agent can apply at each decision step. The design of the action space plays a vital role in shaping the interaction between the agent and its environment, directly impacting the effectiveness and flexibility of learned policies.

To enable maneuverable yet tractable control, we adopt a simplified 3-DOF UAV kinematic model, where each agent’s action is defined as a continuous vector composed of three components:

where:

- : pitch angle command, constrained within ;

- : yaw angle command, constrained within ;

- : overload (normal acceleration) command, limited to .

These action variables serve as direct control inputs to the UAV’s motion model. The resulting displacement along each axis can be computed as:

where:

- : velocity components along the x, y, and z axes, respectively

- : normal acceleration command (overload)

- : gravitational acceleration constant

- : pitch angle command

- : yaw angle command

- are independent Gaussian noise terms representing environmental perturbations and sensor inaccuracies. During training, these noise terms are actively injected to enhance policy robustness against real-world uncertainties

The trigonometric terms , , and represent the direction cosines that project the acceleration vector onto the three coordinate axes. The gravity term in the z-axis equation accounts for gravitational effects on vertical motion.

Through coordinated modulation of pitch, yaw, and acceleration, each UAV can dynamically adjust its flight trajectory in response to task requirements. The use of a continuous action space allows for smooth transitions between control commands, which is critical for realistic and high-precision pursuit behavior in three-dimensional environments.

To enhance robustness and simulate real-world uncertainties, the state transitions incorporate stochastic elements. During training, Gaussian noise is added to control actions, and environmental perturbations are introduced to model sensor inaccuracies and atmospheric disturbances. This stochastic formulation ensures that the learned policies are resilient to real-world uncertainties.

2.3.3. Reward Function

In reinforcement learning, the reward function provides the primary feedback signal that guides agents to learn optimal policies through trial and error. For MARL settings, particularly in cooperative tasks like multi-UAV pursuit, the reward design is critical for achieving convergence and coordination efficiency. A well-designed reward function not only accelerates learning but also ensures that agent behavior aligns with global mission objectives.

To effectively drive the agents toward coordinated target interception, a three-part composite reward function is designed based on the strategic characteristics of the pursuit task:

- (1)

- Tracking Reward: Encourages alignment in velocity and direction between the pursuer and its designated evader. A positive reward is given when the relative distance is reduced and heading alignment is high; otherwise, a penalty is applied.

- (2)

- Multi-stage Distance Reward: Assigns rewards based on the current distance between the pursuer and its target, segmented into far, mid, and near stages. The closer the UAV gets, the higher the reward.

- (3)

- Capture Success Reward: A large positive reward is granted when the agent successfully enters the capture zone of a target; conversely, if the evader escapes the mission boundary, a penalty is imposed.

At each timestep, the pursuing UAV selects the nearest target according to:

where T denotes the selected evading UAV target, and D is the set of distances between the current pursuer and all evaders. Each pursuing UAV locks onto the nearest evader to facilitate the subsequent calculation of advantage metrics.

- (1)

- Tracking Reward

In cooperative pursuit tasks, the flight speed and direction of the UAV determine the effectiveness of the pursuit. As observed in the figure, when the two UAVs are flying towards each other, the pursuit UAV rapidly approaches the target, gaining a more significant angular advantage. Conversely, if the pursuit UAV is flying in the same direction as the target, it will be positioned behind and must chase the target. When the UAV approaches the target at high speed and its flight direction is roughly aligned with the target’s direction, the tracking efficiency is significantly improved, laying a solid foundation for subsequent cooperative interception. Based on this, the tracking reward is computed as:

where represents the tracking reward, V denotes the speed of the pursuit UAV, and represent the relative heading angles of the target evasion UAV and the pursuit UAV, and are the heading angles of the target evasion UAV and the pursuit UAV, respectively, and is the angle between the two UAVs.

Based on the characteristics of the tracking reward function, when the UAV’s decision-making mechanism optimizes primarily for tracking rewards, the UAV will actively adjust its trajectory and speed to ensure that it maintains a favorable relative position and speed with respect to the target evasion UAV. This significantly enhances the overall pursuit efficiency and success rate. By prioritizing the tracking reward in the optimization process, the UAV will naturally adjust its trajectory and speed to continuously maintain an advantage in both speed and position relative to the target, thereby improving the overall pursuit efficiency and task success rate.

- (2)

- Multi-Stage Distance Reward

We design a multi-stage task reward function to clearly and effectively guide the UAVs in executing the pursuit task in complex environments. This method divides the pursuit task into three consecutive stages based on the distance between the UAV and the target evasion UAV: long-distance approach, medium-distance tracking, and close-range capture. Each stage has a different strategic focus and corresponding reward mechanism.

In the long-distance approach phase, the UAV should quickly reduce the distance to the target evasion UAV. Therefore, a relatively low reward value is set in this stage, with emphasis on the UAV’s rapid approach actions. As the UAV enters the medium-distance tracking phase, the reward increases to encourage the UAV to precisely adjust its flight path and speed, ensuring stable and continuous tracking of the target. Finally, in the close-range capture phase, the reward reaches its maximum to ensure that the UAV team swiftly and decisively completes the capture action, creating a significant strategic advantage.

The specific multi-stage task reward function is expressed as:

where is the distance advantage reward the UAV receives at different stages, D is the distance between the UAV and the target evasion UAV, and represent the distance thresholds for entering the tracking, surrounding, and capture stages, respectively. When crossing each threshold, the UAV enters a higher reward stage. The reward values for the long-distance approach, medium-distance tracking, and close-range capture stages are represented by , respectively, where to reflect the distance advantage.

We have designed a multi-stage distance reward function with a piecewise linear form. Its primary purpose is to provide the agent with clear and progressive guidance signals, enabling it to understand the incremental task phases from “long-distance approach” to “mid-distance tracking” and finally to “close-range capture”. Compared to continuous functions such as exponential decay, the piecewise function introduces noticeable changes in reward signals at specific distance thresholds. This helps the agent more explicitly perceive its current task phase, thereby facilitating the learning of stage-specific strategies. The values of the distance thresholds are set empirically based on the UAV’s kinematic capabilities and the relative scale of the task space. Specifically, is set slightly larger than the capture radius to ensure the UAV receives high rewards even before entering the capture range, incentivizing it to complete the final approach. Whereas and are determined according to the size of the task space and the UAV’s minimum time-to-approach, ensuring that each phase provides sufficient scope for strategy learning.

Through this staged reward mechanism, the UAV team can effectively optimize its flight strategy, smoothly transition from the initial approach phase to precise tracking, and ultimately achieve efficient and stable target capture.

- (3)

- Capture Success Reward

When the UAV successfully enters the capture phase, i.e., when its relative distance to the target evasion UAV falls below a specific threshold or meets predefined capture conditions, a one-time large positive reward is triggered to significantly enhance the UAV’s motivation for executing the capture action. Simultaneously, if the evasion UAV exceeds the predefined boundary of the area, a corresponding negative reward is assigned to prevent the UAV from leaving the effective pursuit range, ensuring that it remains within the designated task area at all times. The specific form of the capture success reward function is given as:

- (4)

- Overall Reward Integration

The total reward for each agent at time step t is sum of the above components:

This composite reward structure provides both dense feedback and strategic guidance throughout the pursuit process, significantly improving the learning efficiency and coordination effectiveness among agents.

3. Methodology

3.1. Distributed Cooperative Decision-Making Framework

In cooperative multi-UAV pursuit missions, each UAV must dynamically make decisions by integrating its own observations, task objectives, and coordination requirements with teammates. The overall success of the mission hinges on the system’s ability to achieve effective group-level cooperation. Thus, the design of a reliable distributed decision-making and coordination mechanism is essential.

Although the observation space, action space, and reward function have been formally defined in previous sections, directly applying a DDPG-based independent policy for each UAV often leads to instability. This is due to the non-stationarity of the environment in multi-agent settings, where the dynamics perceived by one agent are affected by the evolving policies of others. Moreover, centralized architectures lack flexibility and scalability when applied to variable-size UAV teams and complex mission environments.

To overcome these challenges, we propose a distributed decision-making framework based on the Multi-Agent System (MAS) paradigm. In this structure, each UAV independently learns its policy while interacting with shared observations and rewards. Meanwhile, a coordination mechanism ensures that UAVs maintain mutual awareness and act cohesively. This distributed design significantly improves scalability and robustness, allowing the system to adapt to agent quantity and task complexity with improved responsiveness and decision quality.

The pursuit task can be modeled as a competitive game between the pursuing UAV team and evading targets. Formally, let S denote the shared observation space, and the respective action spaces of the pursuers and evaders. Let be a deterministic transition function, and let be the joint reward function.

To evaluate collective performance, a global reward is defined as the average of individual rewards across all UAV agents:

For simplicity, the time step subscript is omitted, assuming that at a given time t, when the pursuit UAV team selects a joint action , and the target evasion UAV takes action , the pursuit team receives the instantaneous reward as shown above. The goal of multi-agent systems is to learn a joint strategy that maximizes the long-term discounted cumulative expectation of the global reward . Here, represents the discount factor, which reflects the decay of future rewards.

In this game, the pursuit team aims to maximize its global reward, while the target evasion UAV seeks to minimize this reward, creating a typical adversarial strategy game:

where represents the state at time , which is determined by the transition function . denotes the optimal action-value function, which follows the Bellman equation.

In traditional reinforcement learning methods, the policy is modeled using parameterized deterministic policy functions. Specifically, the pursuit UAV’s policy is denoted as , and the target’s policy is denoted as , where and are the respective policy parameters. To establish a controlled yet challenging training environment, the evading UAVs employ a predefined but adaptive policy that responds dynamically to threat levels, while the pursuit team’s policy is the primary focus of optimization. This setup allows us to systematically evaluate the coordination capabilities of the proposed approach against strategically competent opponents.

Thus, the original two-player game model degenerates into a Markov Decision Process dominated by the pursuit agent:

The global reward determined by Equation (14) represents the overall capture advantage of the UAV team, but it does not reflect the individual contribution of each agent in the collaboration. The overall cooperative effect is composed of the individual goals of each agent. Therefore, the reward function for each agent is defined as:

which describes the reward obtained by the UAV at time t, given that the environment is in state , the pursuit UAV takes action , and the target evasion UAV performs action . represents the relative situational advantage value of UAV i with respect to the pursuit target.

Based on the above reward, for n agents, there are n Bellman equations, with the policy functions sharing the parameter set :

During the learning and training phase, the rewards are allocated appropriately, clarifying the action feedback of each agent in target allocation and capture advantage. By learning and training collaboratively, the agents’ policies converge, ensuring that each UAV’s actions synchronize with those of its teammates, eliminating the need for centralized target allocation. The individual reward structure supports local adaptation, while global averaging ensures system-level cooperation. This framework lays the foundation for scalable, decentralized coordination in the following learning architecture.

3.2. Communication-Aware Policy Learning

While each UAV can learn an individual policy using DDPG or similar reinforcement learning algorithms, such methods typically focus on optimizing single-agent performance and lack modeling capabilities for inter-agent cooperation. This makes them insufficient for complex multi-agent pursuit tasks that demand synchronized behaviors.

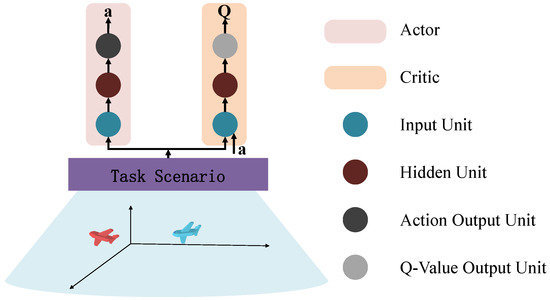

To achieve effective coordination, we introduce a communication-aware multi-agent learning architecture based on Bidirectional Recurrent Neural Networks (BRNNs). In this architecture, each UAV considers not only its own state but also integrates relevant information shared by other agents, such as policy embeddings and environmental observations. This enables policy sharing, decision alignment, and dynamic response adaptation.

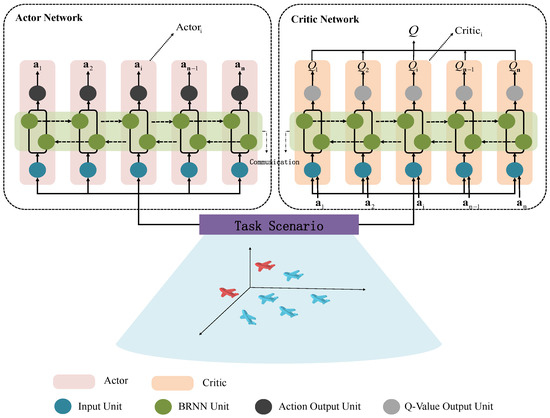

As shown in Figure 4, a single UAV model is constructed using an Actor–Critic framework, where the Actor generates control actions and the Critic evaluates them. The Actor network maps observation inputs to action outputs, while the Critic estimates the value of state–action pairs, enabling stable policy learning.

Figure 4.

Detailed Architecture of the Actor–Critic network for a single UAV agent.

To extend this to a cooperative system, we integrate multiple such units into a BRNN-enhanced architecture. Each agent’s policy and value network include BRNN units that allow information to flow bidirectionally among agents while maintaining local memory. The overall multi-agent structure is illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

BRNN-based collaborative decision-making model for multi-UAV pursuit.

In the proposed framework, both Actor and Critic networks consist of structured submodules, one for each UAV. These submodules are connected using BRNN cells across the agent dimension. The Actor takes the current task state as input and outputs UAV actions, while the BRNN facilitates communication across the team. During forward propagation, it enables real-time information exchange, and during backward propagation, it retains temporal dependencies and aligns policy updates.

The BRNN is trained using Backpropagation Through Time (BPTT), where the network is unrolled across a number of time steps equal to the number of agents. At each unrolled step, the policy output and corresponding local reward are calculated, and gradients are propagated backward across the agent chain. Through the backpropagation gradient mechanism, the strategies and value function parameters of each UAV are jointly optimized, enabling multi-agent cooperative learning. Each UAV adjusts its policy based on the reward it receives, while the shared gradient information in the network ensures that its actions positively guide the overall collective reward of the group.

In terms of the objective function definition, the overall optimization goal of the system is the weighted expected cumulative sum of all individual rewards, which reflects the overall collaborative performance of the multi-UAV system. Given that, under the influence of the policy function and the state transition function, the system state distribution tends to reach a steady state, the objective functions of the multiple agents can be expressed as:

where is the reward function for agent i, represents the state, and is the action taken by the agent under the policy in state .

According to the deterministic policy gradient theorem for multi-agent systems, the gradient of the objective function for n UAVs with respect to the policy network parameter can be expressed as:

where represents the action taken by agent j under policy at state , and is the action-value function for agent i, evaluating the expected return when taking action in state .

To reduce training variance and enhance learning stability, the model employs an off-policy deterministic Actor–Critic algorithm. The Critic network is used to estimate the action-value function, with the squared error loss function during training, defined as:

where is the immediate reward received by agent i when taking action in state , is the discount factor applied to future rewards, and is the value function for agent i under the Critic network parameter .

The loss function is optimized using Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD), gradually updating the parameters of the policy network and the value network.

In the interactive training process, the system continuously interacts with the environment to collect experience data. By leveraging the information integration capability of the BRNN model and the policy optimization capability of the DDPG algorithm, deep collaboration among the UAVs is achieved. This mechanism guarantees the consistency and cooperation of the multi-UAV system’s strategies in complex pursuit scenarios, thus enhancing the overall task completion efficiency and system robustness.

3.3. Learning Procedure and Algorithm Summary

Based on the distributed Actor–Critic framework and coordinated reward design, this section outlines the training pipeline for the cooperative UAV pursuit policy. The goal is to enable the pursuing UAV team to effectively intercept multiple dynamic evaders in a closed-loop simulation environment, forming a strategic interaction between pursuit and evasion.

The training process begins with initializing the task scenario, including the number of pursuers and evaders, as well as their initial positions and velocities. The system state is constructed by aggregating the positions and velocities of all agents. Each UAV is controlled by a pair of Actor and Critic networks, initialized randomly. Target networks are synchronized from the main networks. A replay buffer R is constructed to store experience tuples, and a noise process is added for exploration.

Each episode in training represents a full pursuit process. At each time step within an episode, every pursuing UAV selects an action based on its current policy and exploration noise, while evaders follow a predefined behavior strategy. After action execution, the system transitions to the next state , and individual rewards are computed using the reward function defined previously. The transition tuple is stored in buffer R.

At each update step, a mini-batch is sampled from R. For each UAV agent, the target Q-value is computed:

where is the target Q-value for agent i in the mini-batch, is the reward received by agent i at time t, is the discount factor, and is the action-value function predicted by the target Critic network .

The Critic network gradient is then estimated as:

where represents the gradient of the action-value function with respect to the Critic network parameters , and the term inside the brackets represents the temporal difference error between the target and current Q-values.

And the Actor network gradient is computed as:

where is the gradient of the action taken by agent j under policy with respect to the policy parameters, and is the gradient of the action-value function with respect to the action of agent j.

The optimizer updates the online Actor and Critic network parameters based on these gradients. A soft update mechanism is used to adjust the target networks:

where is the soft update coefficient, which is used to balance the speed and stability of the parameter update.

Episodes continue until reaching the maximum number of training steps or satisfying the task termination condition (e.g., all targets captured or escaped). Once training is complete, the learned Actor networks can be deployed for real-time policy inference in real-world or simulated multi-UAV pursuit applications.

The full algorithmic procedure is summarized in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1 Multi-UAV Cooperative Pursuit Training |

|

4. Experiments and Results

4.1. Scenario Design

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed multi-agent reinforcement learning algorithm in cooperative pursuit tasks, we design two simulation scenarios: a 3-vs-1 and a 5-vs-2 UAV engagement. These configurations allow assessment of the algorithm’s scalability, coordination efficiency, and robustness under dynamic conditions.

In each scenario, the pursuer UAVs are equipped with the proposed reinforcement learning-based decentralized decision-making model. Their policies are updated throughout training based on interaction with the environment. In contrast, the evader UAVs adopt a predefined, threat-aware escape strategy, adjusting their flight direction, speed, and overload in real-time according to the perceived proximity of the nearest pursuer.

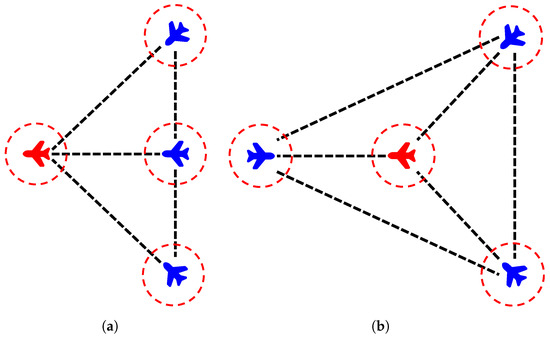

3-vs-1 Scenario: Three pursuer UAVs collaborate to capture a single evading target UAV. Two distinct initial formations are explored:

- Fan-shaped deployment: Pursuers are initialized in a fan-like formation ahead or behind the target UAV. This layout provides a wide coverage area and enables quick convergence toward the target. It is particularly effective when the target’s escape direction is known or constrained.

- Triangular encirclement: Pursuers are positioned at the vertices of an equilateral triangle centered on the target. This symmetric layout creates an initial full-surround structure, reducing escape options and enhancing early-stage containment. It is suitable for open areas with uncertain target headings.

Figure 6 illustrates initial deployment modes used in the 3-vs-1 experiments.

Figure 6.

Initial pursuit configurations: (a) fan-shaped deployment; (b) triangular encirclement.

5-vs-2 Scenario: Five pursuers cooperate to intercept two evading targets. This more complex setting introduces multiple objectives and increased decision coupling, providing a rigorous test of the algorithm’s adaptability and inter-agent coordination.

Target Strategy: Each evader UAV continuously monitors the nearest pursuer and determines its threat level based on distance d. Table 1 outlines the dynamic maneuvering behavior selected at each threat level.

Table 1.

Threat-Based Evasion Strategy.

All experiments were conducted over multiple independent runs to ensure statistical reliability. Performance metrics including success rates and capture times are reported as mean values calculated across these independent trials.

4.2. Experimental Results

To verify the effectiveness and adaptability of the proposed reinforcement learning algorithm in multi-UAV cooperative pursuit tasks, simulations are conducted on both 3-vs-1 and 5-vs-2 scenarios using different initial configurations. Training performance is evaluated based on accumulated rewards, mission success rates, and trajectory coordination. For comparison, we implement a rule-based heuristic strategy [35], where each UAV pursuer selects the closest evading target and moves towards it at maximum speed; and MADDPG, a mainstream multi-agent reinforcement learning method that employs centralized training with decentralized execution.

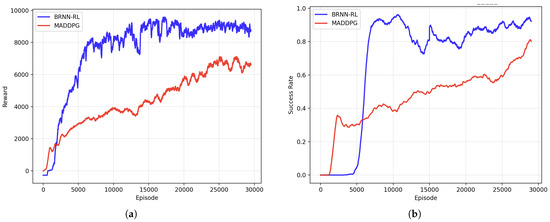

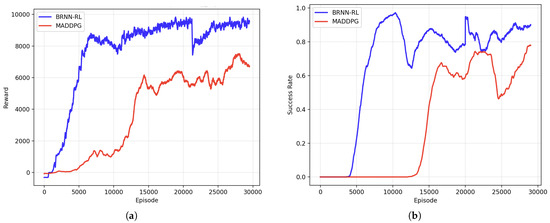

(1) 3-vs-1: Fan-Shaped Deployment

In the fan-shaped pursuit deployment scenario, the UAV team was trained over 30,000 episodes. The performance metrics during the training process are illustrated in Figure 7a,b, with an explanation that a moving average filter (window size = 1000) was applied to smooth both the training and success rate curves. Figure 7a presents the average reward per episode throughout the training process. A rapid increase is observed during the initial 5000 episodes, reflecting the agents’ accelerated policy learning and decision quality improvement. After approximately 15,000 episodes, the reward curve gradually plateaued, and the fluctuations diminished, demonstrating that the policy had converged toward an optimal strategy and that the system had reached a stable training state.

Figure 7.

Training performances of the proposed algorithm and MADDPG in the 3-vs-1 fan-shaped pursuit scenario: (a) reward per episode, and (b) task success rate over iterations.

As shown in Figure 7b, during the early training phase (within the first 5000 episodes), the success rate remained relatively low. However, it quickly improved and reached approximately 90% around the 800th episode. As training progressed, the success rate stabilized and consistently maintained near 95%, indicating that the agents had effectively learned the cooperative pursuit strategy.

The comparative performance of the proposed reinforcement learning method, a rule-based heuristic strategy and MADDPG in this deployment scenario is summarized in Table 2. The proposed BRNN-RL method achieves a task success rate of 94.8%, statistically outperforming the heuristic baseline (68.3%) and the MADDPG baseline (80.2%). Furthermore, the proposed algorithm demonstrates superior time efficiency, reducing the average capture time to 38.1 s, compared to 50.7 s for the heuristic method and 42.3 s for MADDPG. As shown in Figure 7, whether in the training curve or the test results, the performance of BRNN-RL outperforms that of MADDPG.

Table 2.

Performance Comparison: Fan-Shaped Deployment.

The performance improvement of BRNN-RL stems from its core design. The BRNN communication enables strategic coordination among pursuers, enhancing capture success. Meanwhile, its phased optimization prevents policy oscillations, ensuring smoother pursuit and faster capture times.

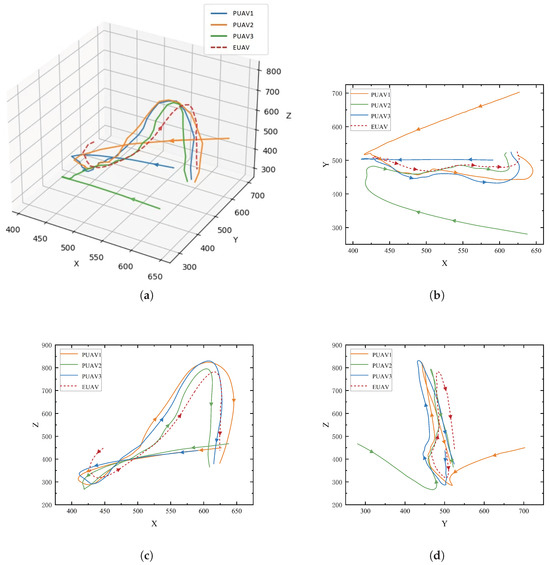

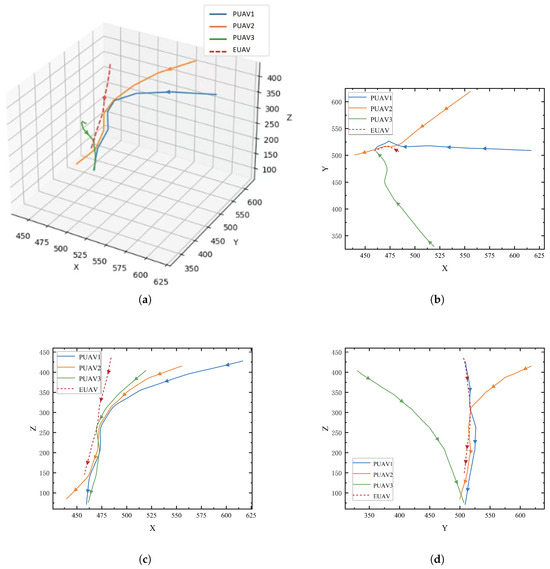

The trajectory of the 3-vs-1 fan-shaped deployment is shown in Figure 8, illustrating the coordinated pursuit strategy of the UAV team. Panel (a) presents the 3D view, where the three pursuers (PUAV1, PUAV2, PUAV3) are shown closing in on the evader (EUAV) in a three-dimensional space. The trajectories of the UAVs demonstrate a coordinated fan-shaped formation, with the pursuers converging towards the evader from different directions.

Figure 8.

Trajectory of the 3-vs-1 fan-shaped deployment: (a) 3D view; (b) XY-plane projection; (c) XZ-plane projection; (d) YZ-plane projection.

Panels (b), (c), and (d) show the projections of the UAVs’ trajectories on the XY, XZ, and YZ planes, respectively. In panel (b), the XY-plane projection highlights the horizontal movement of the UAVs, where the pursuers gradually surround the evader. The XZ-plane projection in panel (c) illustrates the vertical maneuvering, showing how the UAVs adjust their altitude to maintain pursuit. Finally, panel (d) presents the YZ-plane projection, demonstrating the UAVs’ vertical coordination to restrict the evader’s movement in the vertical direction, further tightening the encirclement.

(2) 3-vs-1: Triangular Deployment

Figure 9a,b show faster reward convergence with minor fluctuations in success rate. As illustrated in Figure 9a, the reward curve exhibits a rapid upward trend during the initial training phase (approximately the first 5000 episodes), indicating the agents’ efficient policy learning. Between 8000 and 9000 episodes, the reward stabilizes. A noticeable fluctuation appears around episode 20,000, but the curve quickly recovers and remains steady, reflecting a temporary instability in the strategy that is promptly corrected through further training.

Figure 9.

Training performances of the proposed algorithm and MADDPG in the 3-vs-1 riangular pursuit scenario: (a) reward per episode, and (b) task success rate over iterations.

Figure 9b shows the evolution of the task success rate. The success rate rises sharply during the early episodes and reaches nearly 90% around episode 8000. Although a slight decline is observed after approximately 10,000 episodes, the overall success rate remains high and stable, indicating that the learned strategy is both effective and robust under this deployment scheme.

As reported in Table 3, statistically, the BRNN-RL method achieves a 90.3% success rate, compared to 76.8% for the heuristic method and 78.9% for MADDPG. The average capture time is also reduced from 45.6 s (heuristic) and 43.3 s (MADDPG) to 34.6 s. As shown in Figure 9, whether in the training curve or the test results, the performance of BRNN-RL outperforms that of MADDPG, demonstrating improved efficiency.

Table 3.

Performance Comparison: Triangular Deployment.

The trajectory of the 3-vs-1 triangular deployment is shown in Figure 10, showcasing the movement patterns of the three pursuers (PUAV1, PUAV2, and PUAV3) and the evader (EUAV) in both 3D and 2D projections. In panel (a), the 3D view reveals the coordinated maneuvers of the UAVs as they move through space. This 3D view highlights the complexity of the pursuit, where the UAVs use three-dimensional space to their advantage, adjusting their trajectories to ensure effective collaboration. The evader, in contrast, displays evasive maneuvers, attempting to create gaps and escape the encirclement.

Figure 10.

Trajectory of the 3-vs-1 triangular deployment: (a) 3D view; (b) XY-plane projection; (c) XZ-plane projection; (d) YZ-plane projection.

Panels (b), (c), and (d) offer projections of the UAVs’ trajectories onto the XY, XZ, and YZ planes, respectively, providing a clearer view of the UAVs’ actions in different dimensions. In the XY-plane projection (b), the horizontal movement of the UAVs is more apparent, showing how the pursuers close in on the evader from different angles. This projection emphasizes the horizontal coordination and tactical positioning of the UAVs. In the XZ-plane projection (c), the vertical adjustments of the UAVs are depicted, where they modify their altitude to maintain alignment with the evader’s trajectory, showcasing their ability to adapt to the target’s movement in the vertical dimension. Lastly, in the YZ-plane projection (d), the vertical chase becomes more pronounced, with the pursuers aligning their height adjustments to restrict the evader’s movement along the vertical axis. The combined efforts of the UAVs in both horizontal and vertical dimensions create a dynamic and coordinated pursuit strategy, effectively limiting the evader’s movement space and gradually tightening the encirclement.

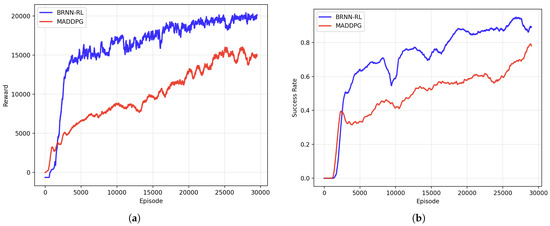

(3) 5-vs-2: Multi-Target Scenario

In this higher-complexity task, training proceeds for 50,000 episodes. As shown in Figure 11a, the average reward increases rapidly during the initial 5000 episodes, reflecting the agents’ rapid learning and policy improvement. After this phase, the reward curve enters a relatively stable region and stabilizes near a high reward value of around 20,000. This pattern indicates that the agents progressively refine their strategies, achieving near-optimal behavior while maintaining high adaptability in complex interactions.

Figure 11.

Training performances of the proposed algorithm and MADDPG in the 5-vs-2 scenario: (a) reward per episode, and (b) task success rate over iterations.

Figure 11b demonstrates a similar trend in success rate. Initially, the performance exhibits volatility, especially within the first 15,000 episodes. However, after this early phase, the success rate improves steadily and surpasses 90% by around episode 20,000. The curve then converges to near 95% success and maintains this performance with minimal fluctuation, indicating the robustness and effectiveness of the learned cooperative policy.

Table 4 shows that the proposed BRNN-RL algorithm achieves a statistically significantly higher success rate (97.4%) compared to the heuristic baseline (80.3%) and MADDPG (79.5%). Furthermore, the RL-based strategy reduces the average target capture time from 75.8 s (heuristic) and 74 s (MADDPG) to 61.2 s. As shown in Figure 11, whether in the training curve or the test results, the performance of BRNN-RL outperforms that of MADDPG. These improvements highlight the superiority of BRNN-RL in multi-target, multi-agent environments, where dynamic coordination and flexibility are critical for performance.

Table 4.

Performance Comparison: 5-vs-2 Scenario.

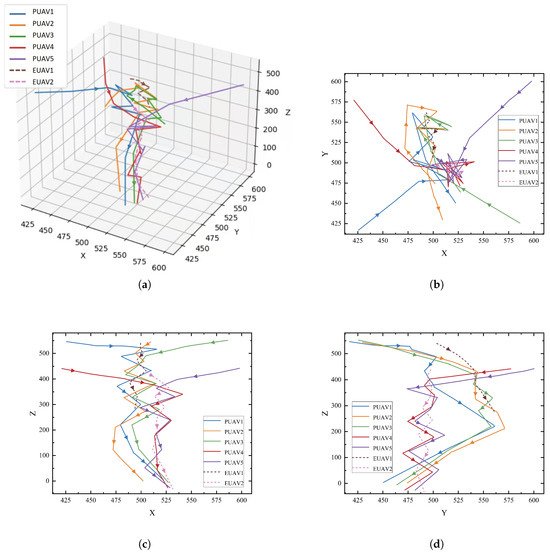

The trajectory of the 5-vs-2 scenario is depicted in Figure 12, showcasing the dynamic pursuit and evasion paths of five pursuers (PUAV1 to PUAV5) and two evaders (EUAV1 and EUAV2). In panel (a), the 3D view illustrates the relative movement of the UAVs in three-dimensional space. The pursuers adjust their positions and trajectories to close in on the evaders. The evaders, in turn, attempt to maneuver and evade capture by altering their paths. The 3D trajectories show the overall movement of each UAV, highlighting the complexity of multi-agent coordination in a pursuit–evasion task.

Figure 12.

Trajectory of the 5-vs-2 scenario: (a) 3D view; (b) XY-plane projection; (c) XZ-plane projection; (d) YZ-plane projection.

Panels (b), (c), and (d) show the UAVs’ trajectories projected onto the XY, XZ, and YZ planes, respectively. In the XY-plane projection (b), the horizontal pursuit strategy is evident, with the pursuers surrounding the evaders from different directions, creating a converging formation. The XZ-plane projection (c) emphasizes the vertical movement of the UAVs, demonstrating how they adjust their altitude during the pursuit to control the evaders’ vertical escape. Finally, in the YZ-plane projection (d), the coordination between pursuers and evaders is more apparent in the vertical dimension, showing how the UAVs restrict the evaders’ movement and compress their escape routes. The combined trajectories in all projections demonstrate the collaborative effort of the pursuers in gradually closing in on the evaders and successfully limiting their escape space.

In summary, across all evaluated configurations, the proposed multi-agent RL algorithm demonstrates rapid convergence, stable performance, and superior pursuit effectiveness. These results confirm the method’s potential for real-world application in large-scale, cooperative UAV interception tasks.

4.3. Hyperparameter Setting

The training of the proposed BRNN-RL framework relies on a set of carefully selected hyperparameters that govern the learning dynamics and policy optimization process. These parameters were determined through systematic experimentation and remain fixed across all training scenarios to ensure consistent performance evaluation. Table 5 summarizes the key hyperparameter values employed in our experiments.

Table 5.

Hyperparameter configuration for BRNN-RL training.

4.4. Hyperparameter Sensitivity Analysis

The performance of reinforcement learning algorithms is critically influenced by the selection of hyperparameters, which govern both the learning dynamics and policy optimization process. To systematically evaluate the robustness of the proposed BRNN-RL framework and provide practical guidance for parameter tuning, we conduct a comprehensive sensitivity analysis focusing on two pivotal hyperparameters: the learning rate () and the discount factor ().

The learning rate controls the step size during policy and value network updates, balancing between convergence stability and training speed. An excessively high learning rate may lead to training divergence, while an overly conservative value can result in slow convergence or suboptimal policies. The discount factor determines the relative importance of future rewards versus immediate returns, directly influencing the agent’s planning horizon and strategic behavior in long-term pursuit tasks.

We select the 3-vs-1 fan-shaped deployment scenario for this analysis due to its balanced complexity and computational efficiency. This configuration provides sufficient interaction dynamics to meaningfully evaluate hyperparameter effects while maintaining reasonable training times for extensive parameter sweeps. The evaluation employs the same performance metrics as previous experiments: success rate and average capture time.

The sensitivity analysis follows a controlled experimental design where one hyperparameter is varied while the other remains fixed at its baseline value. Table 6 summarizes the parameter ranges and experimental configurations.

Table 6.

Hyperparameter Sensitivity Analysis Configuration.

For each parameter combination, we perform independent training runs with identical random seeds to ensure fair comparison. The training process monitors both the learning curves (episodic rewards) and success rates, while final performance is evaluated over test episodes to obtain statistically reliable measurements of success rates and capture efficiency.

4.4.1. Learning Rate Sensitivity

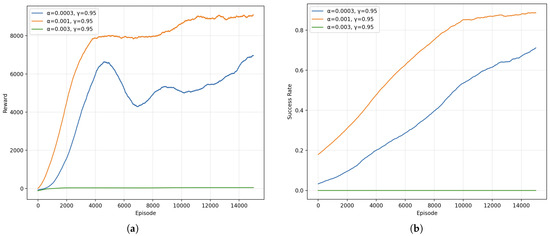

Figure 13 presents the training curves under three learning rates with fixed . Panel (a) shows the episodic reward curves, while panel (b) displays the corresponding success rate evolution. The mid-scale learning rate exhibits the fastest reward growth and the highest asymptotic success rate, while learns more conservatively with slower improvement and a lower final plateau. In contrast, fails to learn, showing near-zero rewards and success rates throughout training, indicative of unstable updates and divergence.

Figure 13.

Training performance under different learning rates (): (a) episodic reward curves, and (b) success rate curves for learning rates .

Table 7 summarizes the test performance over episodes. The setting achieves the best robustness and efficiency, reaching a success rate and the shortest average capture time. The smaller step size attains a success rate with longer capture time, reflecting slower convergence and less decisive policies. The large step size completely collapses, consistent with the flat training curves. Overall, these results indicate a clear stability–speed trade-off and suggest as a reliable default for BRNN-RL in the scenario.

Table 7.

Learning rate sensitivity: test performance (, ).

From the learning curves in Figure 13, reaches high reward rapidly and maintains stable performance after early saturation, whereas shows a slower ascent with mid-training oscillations before steady improvement. The instability at can be attributed to overly aggressive gradient steps that amplify estimation noise in value updates, preventing effective policy refinement. Consequently, moderate learning rates balance exploration of the parameter space and stability of BRNN-RL optimization, yielding superior capture efficiency and success.

4.4.2. Discount Factor Sensitivity

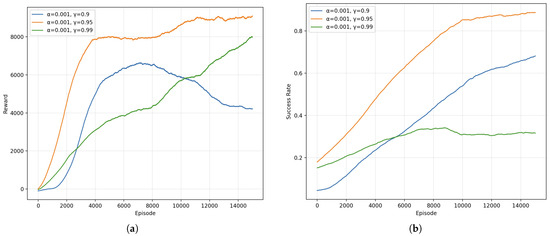

To isolate the influence of temporal credit assignment, we vary the discount factor while fixing the learning rate at . Figure 14 depicts the corresponding training dynamics for . Panel (a) shows the episodic reward curves, while panel (b) presents the success rate evolution. The intermediate discount consistently yields the fastest reward accumulation and the highest success rate, indicating an effective balance between near-term gains and long-horizon planning. The shorter horizon setting learns reasonably well but plateaus at a lower reward and success rate, suggesting premature emphasis on immediate returns. In contrast, the very long horizon exhibits slow reward growth and an early saturation at a low success rate, reflecting diluted credit assignment and increased variance in value estimation that hinders stable policy improvement.

Figure 14.

Training performance under different discount factors (): (a) episodic reward curves, and (b) success rate curves for discount factors .

Table 8 reports the test performance over episodes. The configuration achieves the highest robustness and efficiency, with a success rate of and the shortest average capture time. The shorter horizon attains a moderate success rate and longer capture time, consistent with the lower asymptotic reward observed during training. The very high discount performs poorly ( success rate), accompanied by the longest capture time, corroborating the stagnation and low success-rate plateau in Figure 14b.

Table 8.

Discount factor sensitivity: test performance (, ).

Overall, the results in Figure 14 reveal a non-monotonic relationship between and performance: both overly short and excessively long horizons degrade capture efficiency and success. The inferior outcomes at stem from myopic behavior that undervalues coordinated pursuit sequences, while amplifies bootstrap variance and postpones reward attribution, slowing policy refinement. The intermediate discount offers a robust compromise, aligning temporal credit assignment with the typical pursuit horizon in the scenario and serving as a reliable default for BRNN-RL.

5. Conclusions

This paper proposes a reinforcement learning-based cooperative pursuit algorithm for multi-UAV systems, with a focus on distributed coordination and adaptive strategy learning. The pursuit–evasion problem is formulated as a multi-agent Markov decision process (MDP), and a bidirectional communication mechanism based on BRNN-enhanced Actor–Critic networks is introduced to effectively capture spatiotemporal dependencies among UAV agents. This design supports dynamic task allocation and real-time trajectory optimization in complex environments.

Extensive simulations conducted in various scenarios, including 3-vs-1 and 5-vs-2 configurations, demonstrate that the proposed algorithm statistically significantly outperforms heuristic baselines in both pursuit success rate and capture efficiency. The results indicate that the UAV team can effectively adapt to both single-target and multi-target missions, performing sophisticated spatial maneuvers to achieve coordinated encirclement. The experiments further confirm the algorithm’s fast policy convergence and strong generalization capability under diverse mission conditions.

Future research will integrate energy-aware constraints, limited communication bandwidth, and adversarial learning strategies to enhance the algorithm’s practicality and robustness. Within this framework, the adversarial approach formulates the pursuit–evasion problem as a bilateral multi-agent reinforcement learning task, where pursuers and evaders co-evolve through competitive interactions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.R., C.H. and D.A.; methodology, H.R., C.H. and D.A.; software, H.R., H.P. and K.H.; validation, H.R. and C.H.; formal analysis, H.P. and S.L.; investigation, C.H.; resources, C.H., J.S. and H.P.; data curation, H.P. and K.H.; writing—original draft preparation, H.R.; writing—review and editing, H.R. and C.H.; visualization, J.S., S.L. and K.H.; supervision, J.S. and S.L.; project administration, D.A.; funding acquisition, H.P., J.S. and S.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Key Laboratory of Multi-domain Data Collaborative Processing and Control Foundation of China (Grant No. MDPC-20240303).

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Song, J.; Zhao, K.; Liu, Y. Survey on mission planning of multiple unmanned aerial vehicles. Aerospace 2023, 10, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Huang, W.; Li, H.; Li, W.; Chen, J.; Wu, W. A review of collaborative trajectory planning for multiple unmanned aerial vehicles. Processes 2024, 12, 1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaltsis, G.M.; Shin, H.S.; Tsourdos, A. A review of task allocation methods for UAVs. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2023, 109, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, C. End-to-end multi-task reinforcement learning-based UAV swarm communication attack detection and area coverage. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2025, 316, 113390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponniah, J.; Dantsker, O.D. Strategies for scaleable communication and coordination in multi-agent (uav) systems. Aerospace 2022, 9, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Poon, M.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Lim, A. The multi-visit traveling salesman problem with multi-drones. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2021, 128, 103172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S. MILP-based cost and time-competitive vehicle routing problem for last-mile delivery service using a swarm of UAVs and UGVs. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2025, 124, 102736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, C.; Chen, J.; Du, C. Prioritized Experience Replay–Based Path Planning Algorithm for Multiple UAVs. Int. J. Aerosp. Eng. 2024, 2024, 1809850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Z.; Pan, W.; Weng, K.; Fang, T. A branch-and-price-and-cut algorithm for the unmanned aerial vehicle delivery with battery swapping. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2024, 62, 7030–7055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Huang, L.; Tian, K. Combinatorial optimization for UAV swarm path planning and task assignment in multi-obstacle battlefield environment. Appl. Soft Comput. 2025, 171, 112773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, K.; Cui, G.; Liao, M.; Gan, L.; Kong, L. Transmit-receive assignment and path planning of multistatic radar-enabled UAVs for target tracking in stand-forward jamming. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2024, 60, 5702–5714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, D.S.; Givan, R.; Immerman, N.; Zilberstein, S. The complexity of decentralized control of Markov decision processes. Math. Oper. Res. 2002, 27, 819–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souidi, M.E.H.; Haouassi, H.; Ledmi, M.; Maarouk, T.M.; Ledmi, A. A discrete particle swarm optimization coalition formation algorithm for multi-pursuer multi-evader game. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2023, 44, 757–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, Y.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, L.; Qiu, Z.; Zheng, X.; Li, Z. Collaborative Control of UAV Swarms for Target Capture Based on Intelligent Control Theory. Mathematics 2025, 13, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, W.; Liu, S.; Yang, G.; He, F. Multi-UAV Cooperative Air Combat Target Assignment Method Based on VNS-IBPSO in Complex Dynamic Environment. Int. J. Aerosp. Eng. 2024, 2024, 9980746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haris, M.; Bhatti, D.M.S.; Nam, H. A fast-convergent hyperbolic tangent PSO algorithm for UAVs path planning. IEEE Open J. Veh. Technol. 2024, 5, 681–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Xiang, X.; Yan, C.; Zhou, H.; Tang, D.; Lai, J. Hierarchical probabilistic graphical models for multi-UAV cooperative pursuit in dynamic environments. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2025, 185, 104890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banfi, J.; Messing, A.; Kroninger, C.; Stump, E.; Hutchinson, S.; Roy, N. Hierarchical planning for heterogeneous multi-robot routing problems via learned subteam performance. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2022, 7, 4464–4471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Dou, L.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, X.; Zong, Q. Multi-agent reinforcement learning-based coordinated dynamic task allocation for heterogenous UAVs. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2022, 72, 4372–4383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Li, X.; Yu, R.; Wu, Y.; Ye, J.; Tang, F.; Chen, Q. Digital-twin-assisted task assignment in multi-UAV systems: A deep reinforcement learning approach. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 10, 15362–15375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Long, X.; Li, Y.; Yan, J.; Li, M.; Chen, C.; Gu, F.; Pu, H.; Luo, J. Adaptive multi-UAV cooperative path planning based on novel rotation artificial potential fields. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2025, 317, 113429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Wang, Y.; Mu, T.; Meng, Z.; Wang, Z. Reinforcement learning assisted multi-UAV task allocation and path planning for IIoT. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 26766–26777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, K.; Li, F.; Zhang, F.; Wu, M.; Xu, C. Aoi optimal trajectory planning for cooperative uavs: A multi-agent deep reinforcement learning approach. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 5th International Conference on Electronic Information and Communication Technology (ICEICT), Hefei, China, 21–23 August 2022; pp. 57–62. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.; Wang, F.; Liu, C. A Scale-Independent Deep Reinforcement Learning Framework for Multi-UAV Communication Resource Allocation in Unmanned Logistics. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 11th Joint International Information Technology and Artificial Intelligence Conference (ITAIC), Chongqing, China, 8–10 December 2023; Volume 11, pp. 1609–1618. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, B. An MARL-based Task Scheduling Algorithm for Cooperative Computation in Multi-UAV-Assisted MEC Systems. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Future Communications and Networks (FCN), Queenstown, New Zealand, 17–20 December 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Y.; Qi, N.; Li, X.; Xiao, M.; Boulogeorgos, A.A.A.; Tsiftsis, T.A.; Wu, Q. Distributed multi-UAV trajectory planning for downlink transmission: A GNN-enhanced DRL approach. IEEE Wirel. Commun. Lett. 2024, 13, 3578–3582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Qi, Q.; Fu, Q.; Wang, J.; Liao, J.; Han, Z. Transformer-based reinforcement learning for scalable multi-UAV area coverage. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 25, 10062–10077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Zong, Q.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, R.; Dou, L.; Tian, B. Game of drones: Intelligent online decision making of multi-uav confrontation. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Top. Comput. Intell. 2024, 8, 2086–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Zhou, D.; He, Z. Pursuit-Interception Strategy in Differential Games Based on Q-Learning-Cover Algorithm. Aerospace 2025, 12, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukhbaatar, S.; Szlam, A.; Fergus, R. Learning Multiagent Communication with Backpropagation. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS) 29, NeurIPS, Barcelona, Spain, 5–10 December 2016; pp. 2252–2260. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.; Jain, T.; Sukhbaatar, S. Learning when to Communicate at Scale in Multiagent Cooperative and Competitive Tasks. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1812.09755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Dun, C.; Huang, T.; Lu, Z. Graph Convolutional Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR) 2020, Online, 26–30 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, S.; Sha, F. Actor-Attention-Critic for Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML, Long Beach, CA, USA, 9–15 June 2019; Volume 97, pp. 2961–2970. [Google Scholar]

- Schuster, M.; Paliwal, K.K. Bidirectional recurrent neural networks. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 1997, 45, 2673–2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Wang, C.; Xie, L.; Chen, J. Cooperative pursuit with multi-pursuer and one faster free-moving evader. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2020, 52, 1405–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).