Abstract

A sliding mode predictive control (SMPC) scheme integrated with an extreme learning machine (ELM) disturbance observer is proposed for the trajectory tracking of a flexible air-breathing hypersonic vehicle (FAHV). To streamline the controller design, the longitudinal model is decoupled into a velocity subsystem and an altitude subsystem. For the velocity subsystem, a proportional-integral sliding mode surface is designed, and the control law is derived by minimizing a cost function that weights the predicted sliding mode surface and the control input. For the altitude subsystem, a backstepping control framework is adopted, with the SMPC strategy embedded in each step. Multi-source disturbances are modeled as composite additive disturbances, and an ELM-based neural network observer is constructed for their real-time estimation and compensation, thereby enhancing system robustness. The semi-globally uniformly ultimately bounded (SGUUB) stability of the closed-loop system is rigorously proven using Lyapunov stability theory. Simulation results demonstrate the comprehensive superiority of the proposed method: it achieves reductions in Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) of 99.60% and 99.22% for velocity and altitude tracking, respectively, compared to Prescribed Performance Control with Backstepping Control (PPCBSC), and reductions of 98.48% and 97.12% relative to Terminal Sliding Mode Control (TSMC). Under parameter uncertainties, the developed ELM observer outperforms RBF-based observer and Extended State Observer (ESO) by significantly reducing tracking errors. These findings validate the high precision and strong robustness of the proposed approach.

1. Introduction

A hypersonic vehicle (HV) refers to an aircraft operating in near space at flight Mach number ≥ 5. With its extremely high flight speed and altitude, as well as strong penetration capability, it has revolutionary potential in military strategy and civil fields, and has become a frontier hotspot in international research [1,2]. However, its unique configuration and extreme flight environment result in complex characteristics such as strong nonlinearity, strong coupling, and fast time-variation in its dynamic model [1]. A more severe challenge stems from multi-source uncertainties, including aerodynamic parameter perturbations, unmodeled elastic modal dynamics, and unpredictable external wind disturbances [2]. These uncertainties are often equivalent to composite additive disturbances, which, if not properly handled, will severely deteriorate control performance and even lead to system instability [2]. Therefore, designing a robust controller capable of effectively suppressing strong uncertainties while maintaining high-precision tracking performance is a critical issue to be addressed in the field of HV control.

Regarding the above challenge in this field, researchers both domestically and internationally have proposed various methods, including backstepping control [3,4], sliding mode control [5,6,7], predictive control [8,9], and prescribed performance control [10], etc. A summary of the key advantages and disadvantages of these representative methods is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of Primary Control Methods for Hypersonic Vehicles.

As illustrated in Table 1, among these strategies, Sliding Mode Control (SMC) has been widely studied for HVs primarily due to its inherent robustness against matched uncertainties and straightforward implementation. However, traditional SMC also exhibits notable drawbacks, such as chattering and limited performance under mismatched disturbances. To overcome these limitations, researchers have developed multiple improved SMC schemes in recent years, which can be categorized into three main directions:

(1) SMC for Chattering Suppression. Chattering remains a critical issue for HV actuators, prompting two key improvements: High-order SMC (HOSMC) achieves continuous control signals but suffers from amplified sensor noise due to precise derivative calculations [5]; SMC with continuous switching functions reduces chattering but relies on empirical parameter tuning, with excessive smoothing weakening disturbance rejection [6].

(2) SMC for Mismatched Disturbance Rejection. To handle mismatched disturbances, SMC is increasingly paired with disturbance observers (DOs): dynamic decomposition strategies apply SMC to matched subsystems but increase complexity and rely on strict decoupling, hard to satisfy for strongly coupled HVs [7]; NDO-based SMC improves rejection but shows slow convergence for fast-time-varying disturbances, causing residual errors [11].

(3) Intelligent SMC for Uncertainty Approximation. For unmodeled uncertainties, SMC integrates neural networks (NNs) or fuzzy logic: NN-SMC enhances transient performance but suffers from high latency due to online RBF-NN tuning [12]; fuzzy SMC adapts gains via rules but degrades under unforeseen disturbances due to incomplete rule bases [13].

However, existing SMC schemes still face three critical limitations when dealing with HV multi-source disturbances:

(1) Passive robustness and performance trade-offs. Many robust control strategies (such as adaptive control [14] and intelligent control [15]) inherently rely on the controller’s own adjustment mechanisms to passively suppress disturbances. Such passive compensation often compromises nominal tracking performance [13]. Furthermore, when encountering strong disturbances, their limited regulation capability may lead to performance degradation or even instability [13].

(2) Inadequate disturbance estimation and compensation. While existing approaches (such as the Nonlinear Disturbance Observer (NDO) in [11]) can estimate disturbances, they still confront challenges in estimation accuracy, convergence speed, when dealing with complex, fast-time-varying compound disturbances within HV models. Particularly for disturbances arising from difficult-to-measure elastic modes [16], there is a lack of efficient and rapid online estimation and compensation mechanisms.

(3) Perturbation estimation overly relies on the system model. Existing disturbance estimation methods, such as nonlinear disturbance observers, neural network disturbance observers, and extended state observers, all need to be based on the system’s dynamic equations. Therefore, it is necessary to develop new disturbance estimation methods to realize disturbance observation under the condition of limited prior knowledge, so as to meet the strong robust control requirements of the HV.

To address the aforementioned challenges, this paper proposes a decoupled sliding mode predictive control (SMPC) method integrated with an Extreme Learning Machine (ELM)-based disturbance observer. The key innovations are summarized as follows:

(1) Integrated design of sliding mode predictive controller. For the velocity subsystem, a proportional-integral sliding mode surface is designed, and the optimal control law is directly obtained through predictive optimization. For the altitude subsystem, sliding mode predictive controllers are embedded step by step in the backstepping framework, and an objective function-driven optimization mechanism is constructed for the virtual control law, realizing the deep coupling of the structural advantages of backstepping and the rolling optimization capability of sliding mode prediction.

(2) Active compensation driven by model-free ELM disturbance observer. An ELM disturbance observer is constructed based on tracking errors. Utilizing its characteristics of random feature mapping and least squares analytical solution to achieve fast estimation, the multi-source disturbance estimation values are feedforward compensated into the control laws of each subsystem, significantly enhancing the system’s active suppression capability against unknown disturbances, thus overcoming the limitation of passive robustness.

(3) Stability and performance analysis. Based on Lyapunov stability theory, the semi-global uniform ultimate boundedness (SGUUB) of all error signals in the closed-loop system is strictly proved. The influences of parameters such as prediction horizon, control weighting, and integral coefficient on system convergence and stability are analyzed in depth, providing theoretical guidance for parameter tuning.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the flexible air-breathing hypersonic vehicle (FAHV) model and preliminaries. The controller design and system stability analysis are developed in Section 3 and Section 4, respectively. Simulation studies are made in Section 5 and the conclusions are presented in Section 6.

2. Flexible Air-Breathing Hypersonic Vehicle Model

Considering the longitudinal dynamic model of the FAHV established by Bolender and Doman [17], it consists of five rigid-body states (velocity , flight path angle , altitude , angle of attack , and pitch rate ) and a vector of elastic modes , which are described by first-order differential equations:

where denote gravitational acceleration, moment of inertia, vehicle mass, natural frequencies of elastic modes, and damping ratios, respectively. represent system disturbances, including parameter perturbations and unknown external disturbances. The expressions for lift , drag , thrust , pitching moment , and generalized elastic force are given as follows [18]:

where . , , and denote reference area, thrust arm, and mean aerodynamic chord, respectively. The dynamic pressure is calculated using , the air density model is with , where is the instantaneous altitude and is the scale altitude.

The expressions for aerodynamic parameters under nominal conditions are given as follows [18]:

where , and denote fuel equivalence ratio, elevator deflection angle, and canard deflection angle, respectively, which are the control inputs of the vehicle. Since the canard deflection and elevator deflection have a negative gain relationship , the actual control inputs to be designed are . The meanings and specific values of the coefficients in Equation (3) refer to Reference [18].

It can be seen from Equations (1)–(3) that the longitudinal model of the FAHV is a highly nonlinear, strongly coupled uncertain system, and elastic states have a significant impact on thrust, lift, drag, and moments. However, the elastic states of the system are difficult to measure [16]. Therefore, during controller design process, they can be treated as disturbances to the rigid-body model, estimated by a disturbance observer, and compensated in the control law. Based on the above analysis, the control-oriented model is established as follows:

where the expressions of each function are:

In the above equations, , , , represent comprehensive uncertainties caused by aerodynamic parameter uncertainties, external disturbances, and elastic modes.

The control objective of this paper is to achieve high-precision tracking of velocity and altitude reference signals for hypersonic vehicles under various disturbances. To this end, the fuel equivalence ratio and elevator deflection angle are designed by integrating backstepping control, sliding mode predictive control, and an ELM neural network disturbance observer.

3. Controller Design

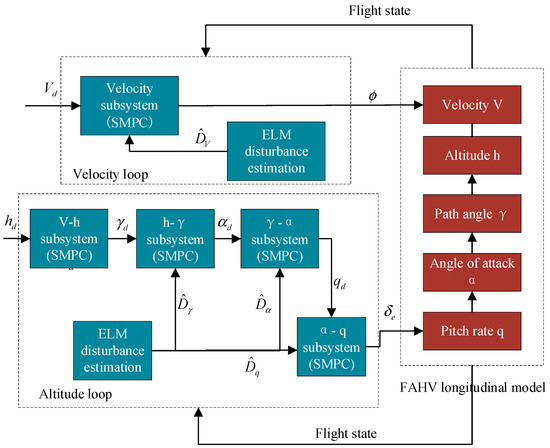

The block diagram of the designed control system is shown in Figure 1. Therein, SMPC denotes sliding mode predictive control. To handle system disturbances, an ELM neural network is designed for estimation, and SMPC laws are designed for the velocity and altitude subsystems, respectively. For the velocity subsystem, the weighted sum of the velocity tracking error and its integral is selected as the sliding mode surface, and the SMPC law is designed based on optimal control theory and disturbance estimation signals. For the altitude subsystem, by integrating backstepping control strategy with optimal control theory, SMPC laws for each channel are devised, and the control laws are compensated using disturbance estimation signals. To solve the “explosion of derivatives” inherent problem in backstepping and further enhance control accuracy, an arctangent tracking differentiator is introduced to replace the traditional first-order low-pass filter for calculating the derivative of the virtual control law.

Figure 1.

Block Diagram of Hypersonic Vehicle Control System.

3.1. ELM Neural Network Disturbance Observer

During the cruise phase of HV, it encounters complex situations such as parameter uncertainty, strong nonlinearity, and strong coupling. The system disturbances suffered by the system will seriously degrade the control performance. Traditional disturbance observers, which depend on precise system models, often suffer from reduced disturbance estimation accuracy under model uncertainty, and their design process is relatively intricate.

The ELM neural network exhibits strong nonlinear approximation capability. It does not need to rely on an accurate system model and can learn the characteristics of disturbances only based on the tracking error state. Moreover, the connection weights between the input and hidden layers, along with the neuron thresholds of the hidden layer, are randomly generated, resulting in a simple and efficient design that provides a new approach for accurately estimating disturbance signals.

To handle , , , in system (4) and make full use of the advantages of neural networks, an ELM neural network disturbance observer that does not rely on the system model and be based on the tracking error state is constructed. This observer enables the effective estimation and compensation of disturbances and improve the control performance of the HV.

The ELM disturbance observer is constructed as:

where is the input signal of the neural network, is the output signal of the hidden layer, is the estimated output weight, ( is the number of hidden layer nodes), and are randomly generated input weights and hidden layer node biases, respectively.

According to the universal approximation theorem of single-hidden-layer neural networks [19], there exists an optimal output weigh satisfying:

where is the approximation error and is bounded [20], i.e.,

Subtracting Formula (9) from Formula (10), the disturbance estimation error satisfies

where, represents the disturbance estimation error, and is the output weighting error of the neural network.

The estimated value of the output weight is updated by the following adaptive law:

where denotes the learning rate of the neural network, and represents the sliding mode surface of the corresponding channel, whose specific design is given in Section 3.2 and Section 3.3.

3.2. Velocity Controller Design

In this section, the controller is designed based on the first dynamic equation of Equation (4), i.e., the velocity subsystem. The ELM neural network disturbance observer presented in Section 3.1 is used to estimate disturbances, and on this basis, a SMPC law with a proportional-integral sliding mode surface is designed to enable the velocity track the given reference signal accurately.

Define the velocity error as

where is the velocity reference command.

Taking the derivative of gives

The sliding mode function is designed as

where .

The predicted sliding mode surface after time is

can also be expressed as

with

The objective function is designed as

where is the control weighting.

According to optimal control theory, the condition must be satisfied, i.e.,

From Equations (14)–(16), (18) and (19), it can be obtained that

Substituting Formulas (18) and (22) into (21), we obtain

Then the control law is derived as

In the above equation, is estimated by the ELM disturbance observer in Section 3.1:

3.3. Altitude Controller Design

In this section, the controller is designed for the other four dynamic equations in Equation (4), i.e., the altitude subsystem. The ELM neural network is used to estimate system disturbances, and a sliding mode predictive controller is designed based on backstepping control. The controller design process is as follows:

- Step 1: Design the virtual control input

Define the altitude tracking error

where is the altitude reference command.

Taking the derivative of gives

The sliding mode surface is designed as

where .

The predicted sliding mode surface after time is

can also be expressed as

where

The objective function is designed as

According to optimal control theory, it is necessary to satisfy the condition , that is,

Based on Equations (26)–(28) and (31), it is obtained that

Then the optimal control condition is transformed into

That is

Hence, the virtual control law is designed as

- Step 2: Design the virtual control input

The flight path angle tracking error is defined as

Taking the derivative of gives

The sliding mode surface is designed as

where .

The objective function is designed as

where is the predictive time.

Similarly to the derivation process in Step 1, the virtual control law is designed as

where is estimated by the ELM neural network in Section 3.2:

- Steps 3: Design the virtual control input

Define the angle of attack tracking error

Differentiating the angle of attack error yields

Design the sliding mode surface as

where .

The objective function is designed as

where is the predicted duration.

Similarly to the derivation process in step 1, the virtual control law is obtained as:

where, is estimated by the following ELM neural network.

- Step 4: design the actual control input

Define the pitch rate tracking error

Differentiating the pitch rate error yields

Design the sliding mode surface as

where .

Design the objective function as

Similarly to the derivation process of the velocity controller in Section 3.2, the control law is obtained as

where, is the prediction time, and is the weight of the control quantity . is estimated by the following ELM neural network

It can be seen from the control law calculation Formulas (42), (48) and (54) that they all require the first-order derivative of the virtual control law. To solve the “differential explosion” problem and further improve control accuracy, an arctangent tracking differentiator is designed to obtain the derivative of the virtual control law.

In the above formula, corresponds to , or , or , respectively; corresponds to , or , or , respectively; it is the input signal of the tracking differentiator, that is, the virtual control law designed in this paper. are the design parameters of the differential tracker, and their values should all be greater than 0.

4. Stability Analysis and Controller Parameter Design

4.1. Stability Analysis

The stability of the closed-loop system can be summarized in the following theorem.

Theorem 1.

Consider system (4) with control laws (24), (37), (42), (48), (54), and tracking differentiator (56), and neural network disturbance observer update laws (25), (43), (49), (55). All error signals in the closed-loop system are semi-globally uniformly ultimately bounded.

Proof.

Select the Lyapunov function as

where , , , are the estimation errors of the neural network output weights for the velocity, flight path angle, angle of attack, and pitch rate channels, respectively.

Taking the first derivative of , we obtain

It is obtained from the control law calculation Formula (24)

If condition is met, then

Therefore,

A similar calculation process can be obtained

When , the following equation is satisfied

Substitute Formulas (61)–(65) into Equation (58), and according to Formula (12), it is obtained that

The neural network output weighted update laws (25), (43), (49) and (55) are substituted into (66), and the result is obtained as

Define the sets

If the selected control parameters satisfy , , , , and , then if , or , or , or , or , the first-order derivative . Therefore, the error states of the system , , , and are semi-globally uniformly ultimately bounded. □

In the proof process above, for the sake of convenience in writing, , , , and are abbreviated as , , , and , respectively. , , , , are abbreviated as , , , and , respectively. , , , and are abbreviated as , , , and , respectively.

4.2. Influence of Parameters on Convergence

Next, taking the velocity channel as an example, the influence of system parameter selection on convergence is analyzed. The analysis process for other channels is similar and will not be repeated.

- (1)

- Selection of prediction horizon and control quantity weighting parameter

From the above stability analysis process, it can be known that if , then when , the system can be guaranteed to be semi-globally uniformly stable. And is used to adjust the control energy and does not affect the stability of the system. However, since the condition needs to be satisfied, the selection of is limited by the prediction horizon parameter .

- (2)

- Selection of integral coefficient

Under the condition that the system is stable, i.e., , the control law (24) is equivalent to

Substitute Formula (73) into (15) and (19) to obtain

Ignoring the disturbance estimation error , compute the zero-input response of Equation (74) to obtain

It can be seen from Formula (75) that as long as , , and , both the sliding mode surface and the tracking error converge exponentially. Among them, the convergence speed of the sliding mode surface depends on ; the smaller is, the faster the convergence speed is. The convergence speed of the tracking error depends on and ; the smaller is and the larger is, the faster the convergence speed is. Overall, its convergence speed depends on the slower pole (that is, the characteristic root with a smaller amplitude, ).

In summary, restricted by the control energy constraint, the value of should not be too small; otherwise, it will lead to control input saturation. The value of needs to be balanced between system stability and convergence speed. Theoretically, a larger value of is, the more conducive it is to improving the convergence performance. However, when , the convergence speed of the velocity tracking error is dominated by . At this time, further increasing has little impact on improving the convergence speed and may even exacerbate chattering.

4.3. Practical Parameter Tuning Guidelines

Based on the above theoretical analysis, this subsection provides a systematic procedure for tuning the parameters , , and in practical applications. Given that the system is nonlinear and the analytical control law is derived after decoupling design, the following guidelines offer qualitative insights that are generally valid across the operating envelope, as opposed to precise quantitative relationships.

- Step 1: Initialize the Prediction Horizon (TV)

- Purpose: Directly controls the convergence rate of the sliding surface .

- Practical Guidance: Set its initial value based on the desired response speed of the sliding dynamics. For instance, if a desired time constant is , start with .

- Key Consideration: Recall that a smaller tightens the critical stability condition , which may necessitate a smaller and consequently higher control effort.

- Step 2: Tune the Integral Coefficient ()

- Purpose: Primarily determines the convergence rate of the tracking error .

- Practical Guidance: As a rule of thumb, set to ensure the error converges faster than the sliding surface.

- Key Consideration: Note that for , the convergence speed becomes dominated by (see Equation (75)). Further increasing has limited benefit and can amplify noise, leading to chattering.

- Step 3: Configure the Control Weight ()

- Purpose: Used to manage control energy and prevent actuator saturation.

- Practical Guidance: The stability condition mandates . A practical initial choice is with .

- Key Consideration: This is the primary parameter for trading off performance against control effort. Increase if saturation occurs; decrease it (within the stability limit) if convergence is too slow and control authority is underutilized.

5. Simulation Results and Analysis

To verify the effectiveness of the proposed control strategy, simulations are conducted under three cases. The initial states and controller parameters are given in Table 2 and Table 3, respectively. Control input constraints are and .

Table 2.

Initial cruise flight conditions.

Table 3.

Controller parameters.

The reference signals for velocity and altitude are generated by a second-order filter,

with final values and

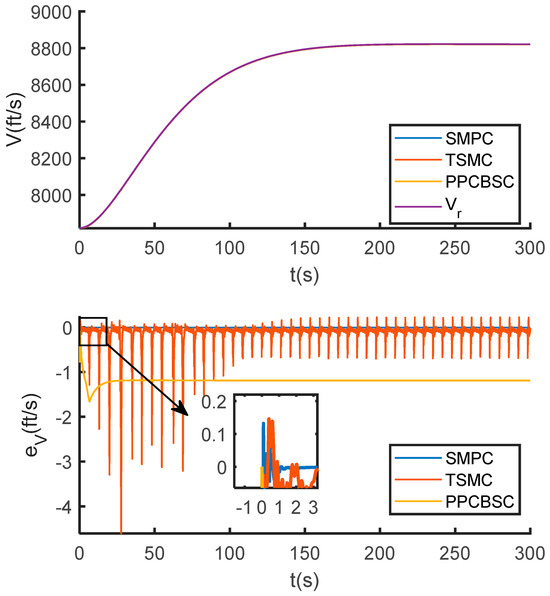

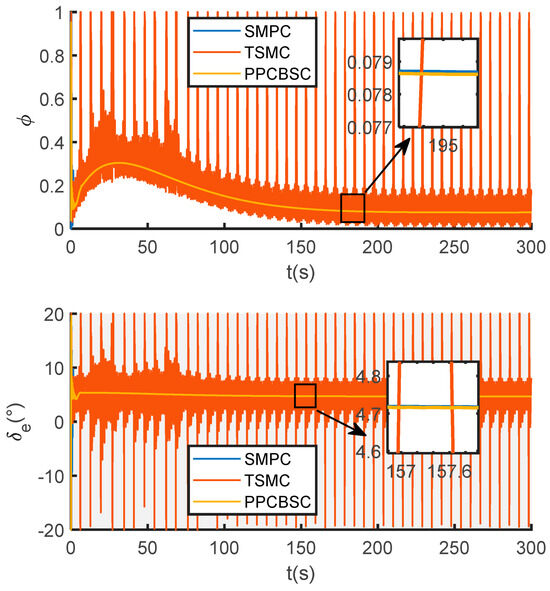

Case 1: The simulation is carried out under the nominal condition, and the results are shown in Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5.

Figure 2.

Velocity tracking curve and error curve.

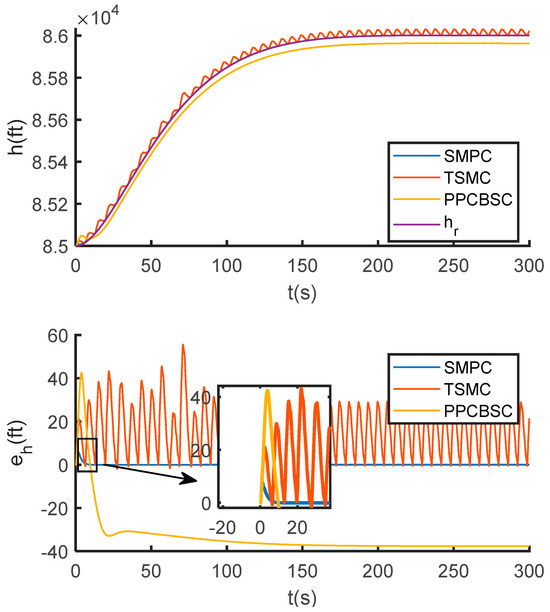

Figure 3.

Altitude tracking curve and error curve.

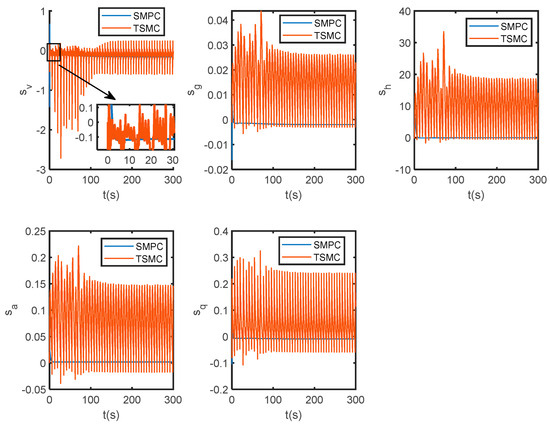

Figure 4.

The variation curve of the sliding mode surface.

Figure 5.

Control law variation curve.

As shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3, the SMPC-based system rapidly converges to the reference commands for both velocity and altitude, with tracking errors approaching zero. Furthermore, the sliding surfaces of all subsystems converge quickly to zero (Figure 4), while the control inputs strictly adhere to the constraints at all times (Figure 5).

In contrast, the Terminal Sliding Mode Control (TSMC) exhibits significant chattering, which leads to observable steady-state errors in velocity and persistent oscillations in altitude tracking. The Prescribed Performance Control with Backstepping Control (PPCBSC), although chatter-free, incurs large steady-state errors in both velocity and altitude due to the inherent limitations on control degrees of freedom imposed by its performance constraints.

Quantitative results from Table 4 underscore this performance gap. SMPC reduces the velocity RMSE from 0.3132 ft/s (TSMC) to 0.0048 ft/s, and the altitude RMSE from 19.9532 ft (TSMC) to 0.5751 ft. The RMSE values for PPCBSC are considerably higher (1.1936 ft/s for velocity and 34.9274 ft for altitude). Moreover, the root mean square value of the altitude sliding surface, a metric for chattering, is 0.5752 for SMPC—over 95% lower than the 12.9737 recorded for TSMC.

Table 4.

Performance value of different tracking strategies in nominal condition.

The underlying reasons for these differences are clear: TSMC’s switching mechanism induces chattering that compromises accuracy, while PPCBSC’s design is inherently constrained by its performance boundaries, limiting its tracking precision. SMPC, by harmonizing prediction and constraint handling, effectively smoothens the control signal, suppresses chattering, and avoids the accuracy loss associated with the other two methods, thereby achieving superior tracking performance and steady-state accuracy.

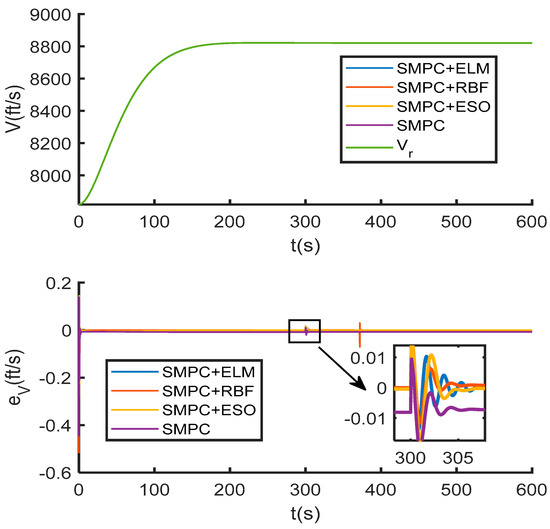

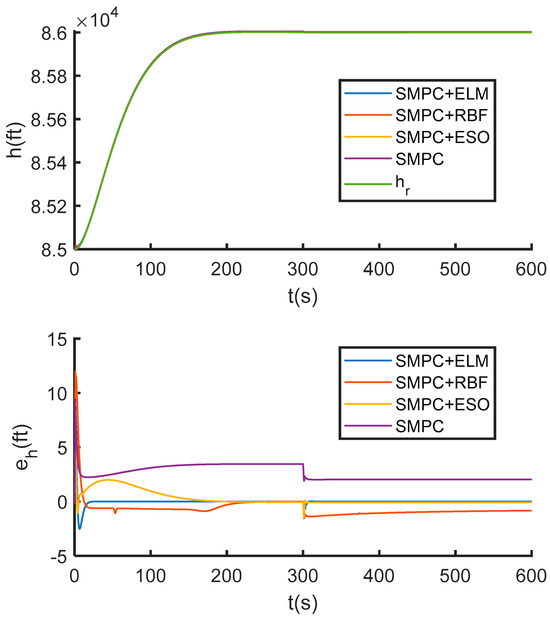

To validate the inherent robustness of the sliding mode predictive control (SMPC) method and the enhanced performance provided by the Extreme Learning Machine (ELM) disturbance observer, this study further conducts simulations under two cases: aerodynamic parameter perturbations and external disturbances. The control performance of standalone SMPC, SMPC combined with Radial Basis Function [12] (donated as SMPC + RBF) or Extended State Observer [21] (donated as SMPC + ESO), and SMPC integrated with the ELM disturbance observer (donated as SMPC + ELM) are compared.

Case 2: Referring to reference [22], the following aerodynamic coefficient uncertainties are considered

where, represents the nominal value of the corresponding aerodynamic coefficient; represents the uncertainty. The uncertainties of drag, lift, thrust, and pitching moment are taken as 15%, −15%, −15%, and −15%, respectively.

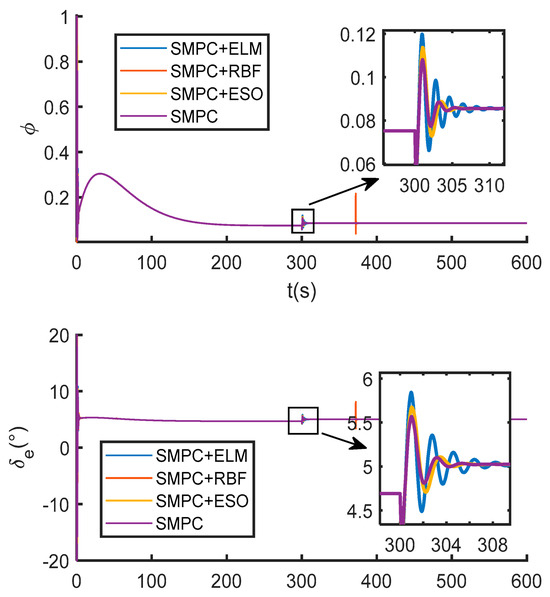

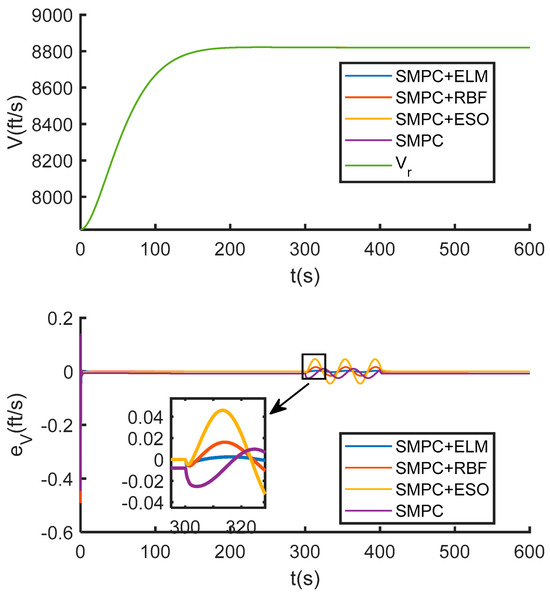

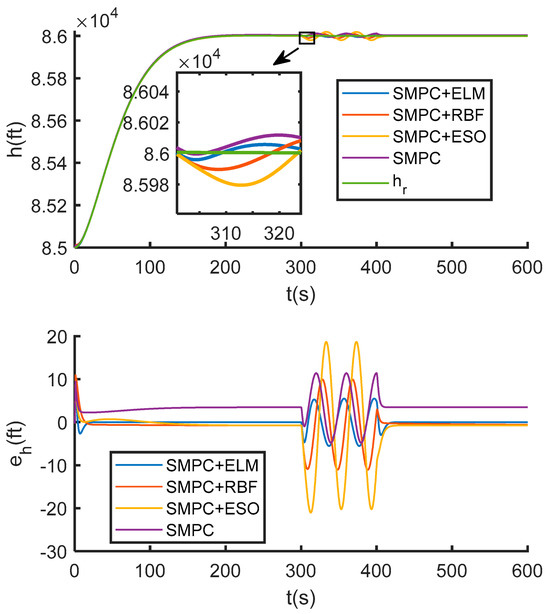

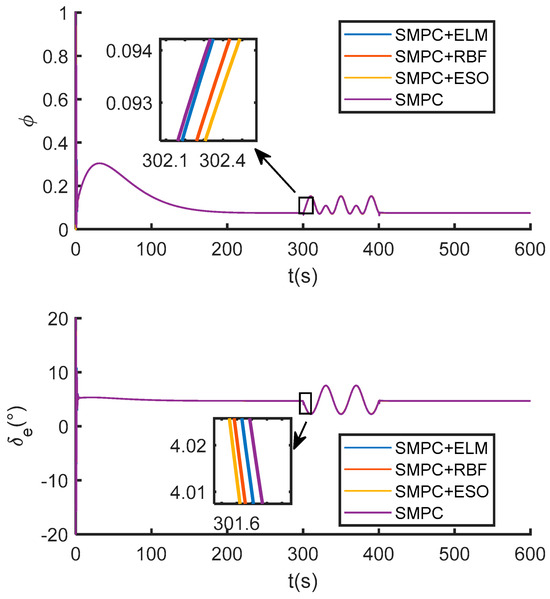

Simulation results are presented in Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8. As shown in Figure 6 and Figure 7, during the initial flight phase (0–300 s) where elastic modes are dominant, the standalone SMPC exhibits minor tracking errors, while all observer-enhanced SMPC methods achieve accurate tracking. This demonstrates the effectiveness of disturbance observers in compensating for unmodeled elastic dynamics. When parameter uncertainties are introduced (300–600 s), the standalone SMPC shows significantly increased altitude errors, revealing its limited robustness. In contrast, SMPC + ELM recovers high-precision tracking after a brief transient. Compared to SMPC + ELM, both SMPC + RBF and SMPC + ESO exhibit slower response and larger error fluctuations. Furthermore, Figure 8 confirms that all control inputs satisfy the prescribed constraints.

Figure 6.

The velocity tracking curve and error curve under parameter uncertainties.

Figure 7.

Altitude tracking curve and error curve under parameter uncertainties.

Figure 8.

Control law variation curve under parameter uncertainties.

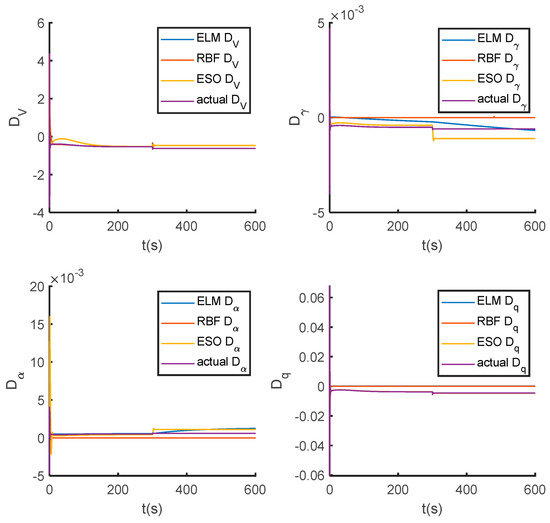

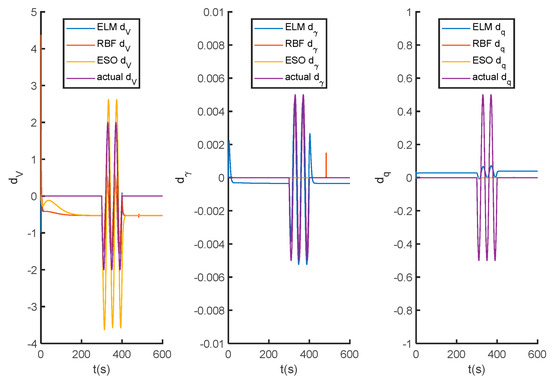

The superior performance of SMPC + ELM is directly attributable to its precise disturbance estimation capability. As evidenced in Figure 9, the ELM observer (blue curve) accurately estimates the composite disturbances , , , and , closely aligning with the actual values (purple). In contrast, the RBF (orange) and ESO (yellow) observers exhibit significant estimation deviations. This accurate estimation enables more effective compensation, which is quantitatively reflected in the RMSE data in Table 5, where SMPC + ELM yields the lowest tracking errors for both velocity and altitude. In summary, the ELM observer’s estimation accuracy underlies the enhanced tracking precision and robustness of the proposed method.

Figure 9.

The result of uncertainty estimation curves under different disturbance observers.

Table 5.

Performance value of different tracking strategies under parameter uncertainties.

Case 3: Considers the following unknown external disturbances:

Simulation results are shown in Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12. As shown in Figure 10 and Figure 11, during the 300–400 s disturbance period, the standalone SMPC exhibits fluctuations in both altitude and velocity tracking errors, with performance recovering after disturbance removal, demonstrating its inherent robustness. In comparison, the proposed SMPC + ELM strategy shows significantly smaller error amplitudes and a faster recovery to high-precision tracking than SMPC + RBF, SMPC + ESO, and standalone SMPC. The superior performance of SMPC + ELM is quantitatively confirmed by its lowest Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) values for both velocity and altitude, as documented in Table 6. Furthermore, Figure 12 verifies that the control inputs of all strategies remain within the prescribed constraints throughout the operation.

Figure 10.

The velocity tracking curve and error curve under external disturbance.

Figure 11.

Altitude tracking curve and error curve under external disturbance.

Figure 12.

Control law variation curve under external disturbance.

Table 6.

Performance values of different tracking strategies under external disturbance.

The exceptional tracking performance of SMPC + ELM is directly attributable to the precise estimation capability of the ELM disturbance observer. As evidenced in Figure 13, the ELM observer accurately estimates the disturbances , and , with its estimation curve closely following the actual values even during rapid pulse disturbances. In contrast, the RBF observer shows limited responsiveness, particularly in estimating and , while ESO exhibits significant fluctuations in estimating and fails to estimate and effectively. The accurate estimation provided by the ELM observer enables timely and effective compensation, which is the fundamental reason for the enhanced tracking accuracy and robustness of the closed-loop system under external disturbances.

Figure 13.

Disturbance estimation curves under different disturbance observers.

6. Conclusions

This study has addressed the challenge of multi-source disturbances in hypersonic vehicles by developing a sliding mode predictive control (SMPC) strategy integrated with an Extreme Learning Machine (ELM)-based estimator. The core of the approach lies in the design of a model-free disturbance observer, which utilizes real-time tracking error data to accurately estimate and compensate for composite disturbances, thereby significantly simplifying the control design process. Furthermore, the innovative embedding of the SMPC scheme within a backstepping framework for the altitude subsystem has effectively enhanced its dynamic tracking performance. Theoretical analysis has rigorously proven that the proposed control law guarantees the semi-global uniform ultimate boundedness (SGUUB) of all tracking errors. Comprehensive simulation results under various scenarios confirm that the method possesses a superior capability to suppress multi-source disturbances and robustly maintain tracking accuracy. In summary, this work provides a feasible and effective technical solution for achieving stable and high-precision control of hypersonic vehicles. Future research will focus on conducting hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) tests to validate the strategy’s performance under realistic computational constraints and further advance its practical implementation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.L. and H.G.; methodology, Z.L. and H.G.; software, Z.L. and H.G.; validation, Z.L. and H.G.; formal analysis, H.G.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.L.; writing—review and editing, Z.L., H.G., J.Z. and W.T.; supervision, H.G., J.Z., and W.T.; project administration, H.G., J.Z. and W.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 62463017) and the Natural Science Foundation of Xiamen, China (Grant No. 3502Z202573079).

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ding, Y.; Yue, X.; Chen, G.; Si, J. Review of control and guidance technology on hypersonic vehicle. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2022, 35, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Shi, Z. An overview on flight dynamics and control approaches for hypersonic vehicles. Sci. China Inf. Sci 2015, 58, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, X.; Lei, H.; He, G.; Gao, Y.; Zhao, Y. Adaptive Neural Back-Stepping Control of Flexible Air-Breathing Hypersonic Vehicles with Parametric Uncertainties. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2018, 10, 1687814018782841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, X.; Liu, J.; Liu, B.; Zhang, Q. Backstepping Control of Hypersonic Vehicles under Input and Output Constraints with Model Uncertainties and Disturbances. Int. J. Control. 2024, 98, 1147–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, C.; Cheng, L.; Gong, S.; Huang, X. Dynamic-matching adaptive sliding mode control for hypersonic vehicles. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2024, 149, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Wang, C.; Shan, L.; Gao, H. Adaptive terminal sliding mode control of hypersonic vehicles based on ESO. Aircr. Eng. Aerosp. Technol. 2025, 97, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, X. Longitudinal coordination control of hypersonic vehicle based on dynamic equation. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part G J. Aerosp. Eng. 2019, 233, 5205–5216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Chen, M. Dynamic Event-Triggered Robust Feedback Model Predictive Tracking Control of Air-Breathing Hypersonic Vehicle Based on Disturbance Preview. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2025, 61, 3291–3305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, P.; Gao, C.; An, R. Fault-Observer-Based Iterative Learning Model Predictive Controller for Trajectory Tracking of Hypersonic Vehicles. J. Syst. Eng. Electron. 2025, 36, 803–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, X.; Jiang, B.; Lei, H. Nonfragile Quantitative Prescribed Performance Control of Waverider Vehicles with Actuator Saturation. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2022, 58, 3538–3548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Hu, W.; Wei, C.; Xu, T. Nonlinear Disturbance Observer Based Adaptive Super-Twisting Sliding Mode Control for Generic Hypersonic Vehicles with Coupled Multisource Disturbances. Eur. J. Control. 2020, 57, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Wei, C.; Zhang, L.; Mu, R. Neural Network Based Adaptive Nonsingular Practical Predefined-Time Fault-Tolerant Control for Hypersonic Morphing Aircraft. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2024, 37, 421–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wang, P.; Tang, G. Fuzzy Disturbance Observer-Based Fixed-Time Sliding Mode Control for Hypersonic Morphing Vehicles with Uncertainties. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2023, 59, 3521–3530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xu, B. Robust Adaptive Control of Hypersonic Flight Vehicle with Aero-Servo-Elastic Effect. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2023, 59, 1955–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; An, H.; Wang, Y.; Xia, H.; Ma, G. Intelligent control of air-breathing hypersonic vehicles subject to path and angle-of-attack constraints. Acta Astronaut. 2022, 198, 606–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Tong, Y.; Jin, F. Control law design of hypersonic vehicles using the elastic surrogate model. J. Low Freq. Noise Vib. Act. Control. 2020, 39, 216–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolender, M.A.; Doman, D.B. Nonlinear Longitudinal Dynamical Model of an Air-Breathing Hypersonic Vehicle. J. Spacecr. Rocket. 2007, 44, 374–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorentini, L. Nonlinear Adaptive Controller Design for Air-Breathing Hypersonic Vehicles. Ph.D. Thesis, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, G.B.; Chen, L.; Siew, C.K. Universal approximation using incremental constructive feedforward networks with random hidden nodes. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 2006, 17, 879–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, H.J.; Zhao, G.S. Direct adaptive neural control of nonlinear systems with extreme learning machine. Neural Comput. Appl. 2013, 22, 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, S.; Fu, W.; Ni, M. Prescribed Performance Optimal Backstepping Control for Hypersonic Vehicles Based on Reinforcement Learning with Disturbance Observer. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2025, 61, 14855–14867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Yuanli, C.; Zhenhua, Y. Adaptive neural network disturbance observer based nonsingular fast terminal sliding mode control for a constrained flexible air-breathing hypersonic vehicle. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part G J. Aerosp. Eng. 2018, 233, 095441001878482. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).