Abstract

Establishing a sustainable human presence on the Moon and Mars will require the use of locally available resources for construction. A binder material similar to concrete is a promising candidate, provided that its production and performance under reduced gravity can be reliably understood. Previous microgravity investigations demonstrated the feasibility of mixing cementitious materials in space but produced irregular or low-quality specimens that limited standardized mechanical testing. To address these limitations, the MASON (Material Science on Solidification of Concrete) team developed the first-generation MASON Concrete Mixer (MCM), which enabled the safe production of cylindrical specimens aboard the International Space Station (ISS). However, its fully manual operation introduced variability and required significant astronaut time. Building on this foundation, the development of an automated MCM prototype is presented in this study. It integrates motorized mixing and programmable process control into the established containment architecture. This system enables reproducible specimen production by eliminating operator-dependent variations while reducing crew workload. In comparison to manually mixed samples, the automated MCM demonstrated reduced variability in the tested concrete properties. The automated MCM represents a first step toward autonomous space instrumentation for high-quality materials research and provides a scalable path to uncrewed missions and future extraterrestrial construction technologies.

1. Introduction

When humans return to the Moon, their greatest engineering challenge may not only be the journey but building a home that can withstand its extreme environment. International exploration roadmaps like NASA’s Artemis program [1,2] or ESA’s Moon Village concept [3,4] envision a sustained human and robotic presence on the Moon and, later, on Mars. Achieving these goals will require the use of locally available resources to produce building materials for habitats, landing pads, and radiation shielding [5,6,7,8]. A regolith-based binder similar in function to concrete—the most widely used construction material on our planet—is a promising candidate if its production and performance under reduced gravity and harsh environmental conditions can be reliably understood and controlled [9,10].

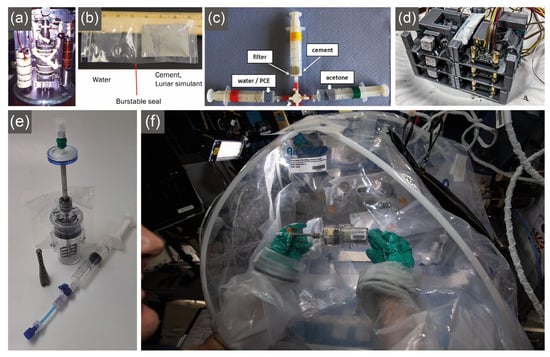

For this purpose, dedicated research under varying gravity conditions in space is essential. A comprehensive review has discussed the impact of lower gravity on the mixing and solidification processes of space concrete, underscoring the critical role of gravity in material development [11]. Research on cement hydration and hardening in microgravity has been constrained by hardware limitations (Figure 1), which have directly affected sample quality, geometry, and the ability to perform meaningful mechanical tests. The earliest attempt to mix cement-based concrete in space was NASA’s 1994 ConCIM (Concrete Curing in Microgravity) experiment (Figure 1a), which produced a single cylindrical sample. Due to a hardware malfunction, the specimen quality was poor, preventing reliable mechanical or microstructural analysis [12].

Subsequent investigations during parabolic flights used syringe-based systems to prepare very small paste samples [13,14] (Figure 1c). While these setups enabled short-duration microgravity studies, the small volume and undefined geometry of the specimens made them unsuitable for standard mechanical testing.

The BRIC (Biopolymer Research in Concrete) project investigates the influence of microgravity on producing a concrete alternative from an organic binder, water, and in situ materials such as lunar or Martian regolith. For this purpose, a dedicated hardware system was developed to fabricate six cubic specimens with an edge length of about 10 mm aboard the ISS in microgravity [15] (Figure 1d). Standard mechanical testing was also not feasible due to the specimens’ small volume.

The MICS (Microgravity Investigation of Cement Solidification) experiment introduced a lightweight and straightforward burst-pouch mixing method to produce small bagged cement paste specimens on the ISS [16] (Figure 1b). This approach had clear advantages in terms of simplicity, very low mass, and ease of integration into ISS operations, and it successfully demonstrated the feasibility of long-duration hydration in microgravity. Part of MICS was also an experiment with the Techshot® MVP onboard the ISS. The samples were produced with the same pouch method and placed into this device. It was used to produce gravitational accelerations of 0.17 g (Moon), 0.38 g (Mars), and 0.7 g through centrifugal motion [17]. However, the resulting samples had irregular shapes and varying volumes, which limited their suitability for standardized mechanical testing and precise quantitative comparisons with ground-produced specimens [18].

The first-generation MASON Concrete Mixer (MCM, Figure 1e,f) [19,20], developed for ESA’s Cosmic Kiss mission in 2022, represented a major step forward. It allowed for safe and reproducible production of defined cylindrical concrete specimens aboard the ISS, meeting strict containment requirements for cement powder. These uniform specimens enabled direct comparison of microstructure, pore distribution, and mechanical properties between space- and ground-produced concrete [9,21,22]. However, the MCM was fully manual, requiring the astronaut to inject water, mix, and compress each sample inside a glove bag (Figure 1f).

In materials research—and especially for the MASON experiments—the mixing process is a decisive step influencing both fresh concrete behavior and hardened properties. Studies have shown that mixing speed, duration, and motion pattern directly affect cement particle distribution, porosity, and ultimately strength and durability [23]. Poor or inconsistent mixing can lead to large inhomogeneities, while excessive mixing can cause overmixing and deterioration of properties [24]. Moreover, the optimal mixing parameters depend on the specific composition of the concrete; thus, both repeatability and adaptability are essential [25,26].

In the first-generation MCM, these parameters depended entirely on human execution. Even with detailed procedures, it is impossible to guarantee identical operation for each sample. Variations in mixing speed, number of blade revolutions, vertical motion cycles, and the operator’s stamina inevitably lead to differences in applied mixing energy, especially over multiple sequential mixes. On the ISS, this reduced reproducibility; in future uncrewed missions—such as lunar surface experiments or suborbital flights on platforms like Morpheus—manual operation will not be possible at all.

The automation of the MCM described here addresses these challenges. By integrating motorized mixing, automated liquid dosing, and programmable control into the proven safety architecture, the automated MCM will execute a complete, reproducible mixing cycle with minimal or no crew interaction. This enables higher throughput, eliminates human variability, and makes the hardware suitable for both crewed and uncrewed missions. The present work describes the development and testing of an automated MCM prototype as a foundation for future space-qualified versions, capable of supporting high-quality, reproducible concrete specimen production across a wide range of mission scenarios. The purpose of this study is to present the design concept, implementation, and performance evaluation of this automated system as a key step toward fully autonomous materials research in space.

Figure 1.

Hardware developments for the production of cementitious specimens in microgravity. Top row: ConCIM apparatus (a) [27], MICS burst pouches (b) [27], syringes used in parabolic flights (c) [14], and BRIC production hardware (d) [15]. Bottom row: MCM kit with mixing tool and syringe (e) and MCM in operation on the ISS (f) [19].

2. Development of an Automated Prototype of the MCM

2.1. Preliminary Considerations, Requirements, and Experiments to Determine the Specifications

For a starting point, a list of requirements is created, which defines the basic requirements for the prototype, focusing on the production of the concrete sample as the main task. It is important to note that the current prototype is not intended to be a product that will ultimately be used to produce these samples in space. Rather, it is intended to demonstrate that gradual automation of the process is possible and that further research and development are necessary to optimize, further develop, and ultimately utilize this fundamental principle. This is also due to the fact that the prototype is not currently being designed for a specific application but is intended to serve as preparation for possible further experiments on the ISS, on board another spacecraft, or even on the Moon. The formulated requirements relate to both the task at hand and the analysis of the factors influencing the quality of the samples:

- Automation of the MASON experiment in the form of automation of the mixing process and thus standardization of the production of cylindrical concrete samples;

- Integration of the MCM, as it is already approved as space hardware and meets all requirements for the production of the test specimens;

- Development and production of a prototype that can be used in a laboratory-like environment to enable further developments within the MASON project;

- Fulfillment of the necessary performance specifications required by the process;

- Implementation of a modular structure to allow for subsequent changes to hardware and process and thus provide space for subsequent research;

- Development of a general concept that can be adapted for use in space by using suitable hardware components and adding system modules.

This list summarizes the general conditions that apply to the prototype. After product development and testing, these conditions must be reviewed and assessed to determine whether they have been adequately met.

The list determines that the MCM would remain as a system component, forming the basic system. The use of the first-generation MCM is described briefly as follows: the dry components were stored in the lower part of the mixer and remained sealed until the experiment. The syringe was attached to the upper end of the mixing tube, and water was injected through an opening at the lower end of the tube directly into the dry material. The components were then mixed for two minutes using the manual mixing tool. After mixing, the blade was retracted upward into the retention chamber to avoid interference with the specimen. In the final step, the two container parts were pressed together to compress the fresh sample, with excess air escaping through a filter. After hardening, the MCM was disassembled, and a specimen of approximately 50 mm in length and 30 mm in diameter was retrieved for analysis (detailed description in [9,19]). The MCM forms the central building block around which the new system is planned. From a mechanical perspective, the mixing process requires a mixing unit that performs the movements previously performed manually. This mixing unit is controlled and driven by electronic components that ensure the flow of energy and information.

In order for the mix components to be processed into a concrete sample in the MCM, the MCM must be mechanically connected to the new mixing unit. The analysis and description of the test procedure states that the mixing process consists of two movements—a rotation and a linear movement of the mixer blade in the mixing chamber. From a purely mechanical perspective, it is possible to link these two types of movement so that only one motor would be needed to drive them. However, in this case, there is always a dependency between the two movements. For this reason, a separate drive is provided for each movement. The drives and movement elements together form the mixing unit.

Both drives are powered by electrical energy, so they must be connected to a power supply, which in turn is supplied with electrical energy from outside the system. In addition to the drives, the power supply also transmits energy to all other electronic components. These include the controller, the operating element, the display device, and the sensors. The controller is at the center of the electronics, as it processes all incoming information flows and uses this information to forward them to the drives. The system status is monitored via the sensors, and information about any status changes is transmitted to the controller. Users can transmit commands to the controller via the operating element (as a human–machine interface) and receive information about the system status back from the display device in order to carry out manual steps. This means that all input and output variables are taken into account and classified within the system.

To connect the MCM, drive unit, and electronics, a frame is also integrated into the system. This frame is required to connect the components selected for the building blocks later. The developed system structure has the advantage that each building block can be individually designed, and suitable concepts and products can be selected. Furthermore, the structure is designed in a general way, considering the necessary input and output variables, and is thus independent of other environmental conditions. These can be used and considered accordingly for the specific application, so that the structure applies not only to the prototype, but also to all subsequently developed systems (for example, for use on the ISS or the Moon).

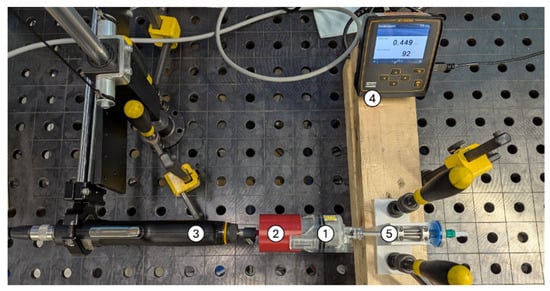

In order to select and calculate the necessary components for the mixing unit, data must first be collected to enable this design. For this purpose, torque tests are carried out with the MCM. After obtaining an approximate measuring range (0–3 Nm), a fitting test setup is developed. Since a measuring range of less than 3 Nm involves low torques, specialized and high-resolution measuring equipment is required to directly measure the dynamic torque during mixing. This equipment is located in the tightening laboratory of Atlas Copco Tools Central Europe GmbH in Essen and is extended by suitable fixing elements. The complete setup is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Test setup for the torque tests.

In the center of the test setup lies an MCM (1, see Figure 2), which is connected to the measuring tool (3) by a nut (2) produced using additive manufacturing. This measuring tool is connected to a controller (4), which specifies the sequence of rotary movements to be performed by the tool and transmits all recorded values to a computer. The mixing tool is attached to the mixer tube and is secured against slipping along the tube by two shaft clamping rings. To prevent the mixer tube from rotating, it is embedded in a component that is also additively manufactured, which is fastened to the table with screw clamps (5).

The measuring tool is an Atlas Copco ETD MT41-250-I06 [28], a small handheld electric screwdriver, which, with its integrated measuring transducer for determining torque and angle of rotation, achieves an accuracy of ±5% [29]. This can record torques from 0.02 to 2.5 Nm and thus covers most of the assumed range. To maintain their accuracy, electric tightening tools must be tested regularly [30]. In the case of the tool used, this is done at least annually in the form of a dynamic counter measurement across the entire measuring range. The counter measurement is carried out using calibrated measuring cells, ensuring metrological traceability [31]. The control system (Atlas Copco MTF6000 [32]) records the time and the associated values for speed, torque, and angle of rotation for each test run at a sampling rate of 1000 Hz. Details of the test procedures and results are provided in Appendix A.

The movements performed should simulate and imitate the actual mixing process as closely as possible. To this end, measurements are taken both during the mixing of the components before and after the addition of water. The selected mixtures were perceived as particularly challenging in both the experiments on Earth and on the ISS. For this reason, the highest torques should occur when mixing these components, so that subsequent design based on this ensures that all experiments can also be carried out by the automated hardware.

In addition to their relevance to the research project, the mixtures consist of particles of different sizes (see Table 1). R and R-R exhibit a very fine-grained, powder-like structure due to the cement and the Regolith simulant EAC-1A, while the CEN standard sand, according to DIN EN 196, added to R-SS consists of grains up to a maximum of 2 mm [33]. In comparison, the cement has an average grain size of 5–20 µm [34], while that of regolith EAC-1A is between 100 and 200 µm [35].

Table 1.

Mixtures in the torque tests.

The most important value from these tests is that a torque of 112.4 cNm was not exceeded in the present setting (see Table 2). However, since the measured data fluctuates considerably, particularly with the associated mixture (R-SS), a safety factor must be factored in to ensure that the technology does not fail even at higher required torques. This value should therefore only be understood as a necessary lower limit. In addition, two further factors that influence the measured results must be taken into account: the accuracy of the tool used (±5%) and the use of the same MCM across all tests. On the other hand, it was already determined in the preliminary tests and also in the test with R and water that the torque absorbable by the mixer blade is limited. In the range between 230 and 250 cNm (i.e., 2.3–2.5 Nm), the carbon, the weakest element of the MCM, breaks, preventing full functionality. A torque of 2 Nm is therefore not only sufficient for the drive unit but also serves as a safety measure to prevent damage to the MCM. To prevent these values from being exceeded, the mixing program should be designed so that high torques are never reached. This could be achieved by regularly reversing the direction of rotation or by torque monitoring.

Table 2.

Maximum determined torques.

2.2. Design and Production of the Prototype

Based on the developed system structure, suitable solutions for the individual system components, as well as possible products for use in the prototype, are sought, taking into account the stated requirements and the necessary torque. Since the system should also be adaptable for use in space, and it has already been decided that it should be powered by electric motors, the first step is to determine which motor types are suitable. In addition to stepper motors and piezoelectric motors, both brushed and brushless direct current (DC) motors are available for implementing rotations [36,37,38,39]. Linear motors can also be used to generate linear movements without additional mechanical components. However, these are usually designed for use in short linear movements of less than 50 mm [36].

First, the mixing unit, which carries out the movements of the mixing process, is considered for the prototype. For this, both a rotary and a linear movement must be implemented in isolation from one another. As previously mentioned, it would be possible to implement both movements using a single motor, which would mean coupling them. However, in order to optimize the mixing process, it is necessary to be able to control these movements independently. The other system components for the transmission of force and motion, besides the motors, must also be taken into account. The rotary movement must be continuous, and the drive must provide a torque of approximately 2 Nm. No force was determined to be applied for the linear drive, but the design of the MCM results in a movement length of approximately 85 mm, which corresponds to the distance from the floor of the mixing chamber to the storage chamber for the mixer blade, i.e., the maximum distance that the mixer blade can travel inside the MCM lengthwise. Both movements should be controllable as precisely as possible, on the one hand to prevent damage to the MCM and on the other hand to enable precise adjustment of the mixing process.

During the torque tests, it has already been determined that there are two possible starting points for attaching a drive: the mixer tube and the lower section of the MCM, consisting of the mixing and storage chambers. However, while the torque tests only considered the rotational movement, both movements must now be combined. In contrast to the tests, in which the rotation was transmitted via the mixing chamber, it makes sense to perform both movements on the mixer tube, similar to the MASON experiments on the ISS. Consequently, the lower section of the MCM must be fixed, whereby the movement of the mixer tube is restricted to two degrees of freedom. One of these degrees of freedom is rotation around its own axis, and the other is translational movement along this axis from the floor of the mixing chamber into the storage chamber.

Linear relative movements of components can be achieved mechanically using linear guides. These exist in various designs and are used, for example, in tools or special machine tools to guide tables and slides [40]. Manufacturers such as Maxon Motor GmbH also offer versions for use as space hardware. The spindle drive used converts a rotary movement—generated by a motor—into a linear movement [37]. Such spindle drives are used in many industrial applications and can therefore be found in the product portfolios of many manufacturers. A suitable module for this application is the lubrication-free drylin® SHT linear module from Igus GmbH. It is available in various designs and, with a standard stroke length of 100 mm and self-locking in size 12—related to the shafts—meets the necessary requirements for the linear drive [41]. The spindle drive moves the slide along two shafts by 2 mm with each revolution. In addition to the purely mechanical linear module, the manufacturer also offers the necessary drive technology. In this case, a stepper motor of size NEMA 17 with a holding torque of 0.5 Nm and a step angle of 1.8° (±5%) and including a suitable control system (Igus dryve D7) is proposed [42,43].

Stepper motors are a special variant of synchronous motors. Cyclically pulsed voltages are applied to the internal windings to rotate the rotor by a specified step angle. This ensures precise positioning of the motor and, in some applications, also of the linear guide. However, in addition to the motor itself, an external stepper motor controller (also called a driver) is required to process the input voltage and control signals. These motors have a long service life, are robust, and generate only a low noise level. For these reasons, they are used in testing technology and for positioning drives [44].

Since the adaptation of the mixing process places demands on the drive unit, a stepper motor is also used for the rotary movement. To simplify things, the same model is used as for the linear guide. Although less efficient for continuous rotation, it enables control identical to that of the linear drive motor and provides higher programming precision, enabling features such as accurate synchronization of the mixing sequence or position detection of the mixer tube and blade in further development. However, there are two problems with using it as a rotary drive: Firstly, the maximum torque generated of 0.5 Nm is not sufficient to drive the mixer directly. Secondly, a direct connection between the motor and the mixer tube would close off the connection for the syringe. Therefore, the motor was connected to the tube via a gearbox, which, on the one hand, enables off-center mounting of the motor and, on the other hand, increases the torque to the desired 2 Nm.

Due to the opening required for water injection at the top of the mixer tube, a gearbox is selected that enables power transmission from a motor located on the side. Therefore, a gearbox with crossed axes is required. In addition to offset bevel gears, worm gears, which belong to the group of helical gears, are also suitable for this purpose. Each gear stage consists of a worm and a worm wheel. Worm gears allow for a wide gear ratio range and ensure high load capacity [45].

Manufacturers such as Ganter offer worm gears with compact dimensions, which enable power transmission even in small drive units. In addition, the hollow shaft on the output side makes it possible to push the mixer pipe all the way through. This leaves the opening for injecting the water accessible [46]. The basic conditions for selecting a suitable gear unit are the required output torque (2 Nm, derived from the torque tests), the maximum speed that can be achieved with the motor control unit and the associated motor torque (approx. 0.35 Nm at 500 rpm), and a realistic output speed of 25–50 rpm for the mixing process [46]. The required input torque for an output torque of 2 Nm is below the 0.35 Nm provided by the motor at 500 rpm for all ratios. Therefore, the output speed is the deciding factor for the gearbox used, so the smallest ratio (i = 13) is selected.

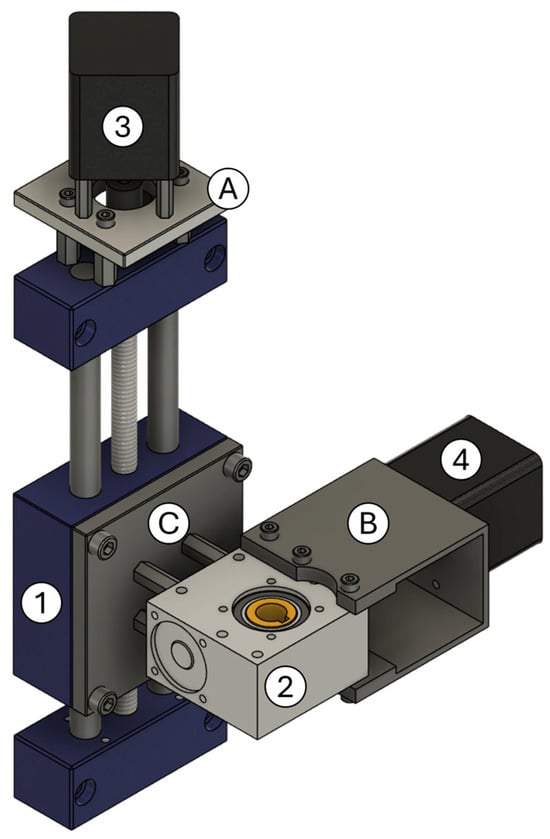

With the linear guide (1, see Figure 3), the worm gear (2), and the two motors (3,4), all components for the mixing unit are defined and specified. Suitable connecting elements are required to combine these components. To transmit the rotary movement and torque, the motor shafts must each be connected to the corresponding drive mechanism. For this purpose, simple, non-switchable shaft couplings are used; these are slipped onto the shafts and then clamped onto them with a screw [45,47]. Since the manufacturer Ganter offers matching shaft couplings in addition to a suitable worm gear, both the gear and the shaft couplings are taken from their product range. In addition to the GN 3975 worm gear with i = 13, two GN 2240 shaft couplings are selected, which are also suitable for use with stepper motors [46,48].

Figure 3.

Design of the mixing unit.

The remaining connecting elements result from the design of the mixing unit shown in Figure 3. The connecting elements are selected and designed based on screw connections so that the prefabricated threads on the linear guide and worm gear can be used for fastening. In addition to standard components such as screws and spacer bolts with internal and external threads, three custom connecting elements are required. These are developed taking into account the principles of design theory [49,50]. Since the shaft couplings only serve to transmit motion and torque, additional mechanical connecting elements must be used between the motor and the mechanical system.

For the linear guide (1, see Figure 3), a plate with through holes for the screws and coupling is designed (A), taking into account the length of the spacer bushings and the shaft. The connection between the other motor and the worm gear is achieved by a component that encloses the gear and, in addition to the holes for the motor currently in use, has further holes to accommodate a NEMA 23 or 24 motor (B). Depending on further development, a correspondingly more powerful motor could be installed. A second connecting plate is inserted between the carriage of the linear guide and the worm gear (C). Spacer bushings are also used here to create a distance between the components. Dimensions and tolerances, particularly for the through holes, can be found in the relevant tables.

Starting with the mixing unit, the next step is to design the frame, which will hold all mechanical and electronic components. For similar structures, aluminum profiles are often used in mechanical engineering. These profiles are offered by various manufacturers such as Bosch, MayTec, or Item. The profiles from these manufacturers are compatible with each other and are offered with a wide range of accessories for connecting the profiles to each other or to other components. The profiles are available in different dimensions and cross-sections for various applications. For the described application, the designation aluminum profile 40 × 40 light, groove 8 I-type is chosen. The dimensions and the groove shape also determine the options for selecting accessories. The basis is threaded T-nuts that can be inserted into the groove. These allow add-on components to be attached to the profile using screws and the connection to be released again as required. This setup facilitates subsequent modifications to the prototype without great effort. To simplify the assembly, a frame was developed consisting of five 500 mm long profiles.

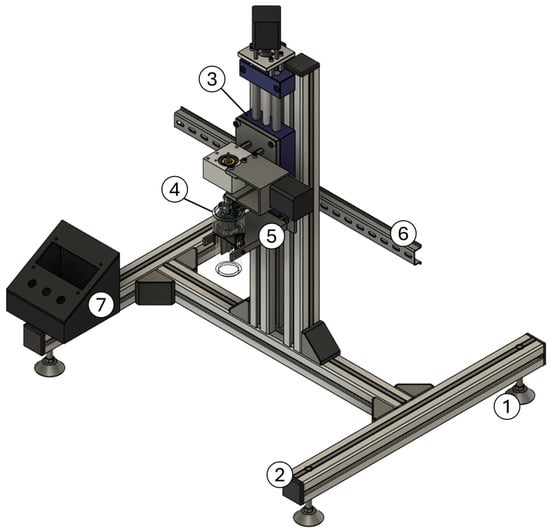

To allow the prototype to be placed and leveled on a work surface, adjustable feet are mounted beneath the profiles at all four corners (1, see Figure 4). For operator protection and aesthetic reasons, all angles and open profile ends are also provided with cover caps (2). In addition to accommodating T-nuts, the slots can later accommodate electronic cables. To protect them, the slots are closed with cover profiles.

Figure 4.

Overall design of the structure.

The setup shown in Figure 4 enables the mixing unit (3, comp. Figure 3) and the MCM (4) to be positioned vertically. For this purpose, the mixing unit is attached to the frame via the linear guide using screws and T-nuts. The mixer tube of the MCM is guided from below through the worm gear, and the MCM is attached separately to the frame. This attachment is achieved using another component designed for this setup, which is screwed on below the linear guide (5). It surrounds the MCM from the right and left and, thanks to the elongated holes on the sides, enables the MCM to be attached using screws that engage in threaded bushings embedded in the mixing chamber. With just two screws, this setup prevents the MCM from making any translational or rotational movements, so that only the mixer tube is moved by the mixing unit. An adapter for the mixer tube is also required for the different shaft sizes of the tube and worm gear. This consists of two parts, one of which is inserted laterally onto the two milled surfaces on the mixer tube, and the other is then inserted along the mixer tube. This creates a positive connection between the mixer tube and adapter, as well as between the adapter and the worm gear for rotating the mixer tube. A shaft clamping ring is inserted above and below the worm gear to transmit the linear movement to the tube.

To mount the electronics, only a DIN rail is initially planned on the back of the frame (6). The black box, integrated into the overall design (7), will only be added during production, once the electronic components have been selected and their dimensions have been determined.

The overall design thus takes into account the requirements defined at the outset as well as the subsequently developed system properties. By combining a linear guide with a worm gear, both necessary movements (rotation and translation) can be performed, meeting all requirements for automating the mixing process. The torque determined and required for mixing, which is generated by the stepper motor and worm gear drive, is also taken into account. For both the mechanical and electronic components of the mixing unit, products are used that, although not themselves approved as space hardware, exist in versions with the necessary approvals [36,37,38].

The design is based on the developed system structure and integrates suitable solutions and products. These largely rely on commercially available products, making them not only easy to procure but also easily combined with other design elements. In particular, the choice of aluminum profiles for the frame results in a structure that is easily adaptable and expandable. The integration of the MCM was successful without modifying its components, meaning that no costly modifications to the injection molds were required to use it in the prototype.

By implementing the overall design as a CAD project, a digital twin of the structure is created, which can be used as the basis for producing the prototype. In the first step, products that can be ordered and individually manufactured are identified and categorized into mechanical components, such as the linear guide, the gear unit, and the shaft couplings, aluminum profiles and fastening accessories, electronic components like stepper motors and the associated control and supply electronics and lastly all elements that are not available as a finished product and therefore have to be specially manufactured for the prototype.

Since the prototype primarily involves product development in the mechanical field, the selection of electronic components, as a discipline of mechatronics, offers only a limited technical relevance. The selection of stepper motors and the associated controllers already provides a starting point for further planning. Based on the system structure and the necessary properties, existing or pre-configured electronic systems are researched, and suitable components are selected on this basis. In addition to industrial controllers, the manufacturer of the stepper motors and controllers (Igus GmbH) also suggests microcomputers such as Arduino [51]. Arduino offers a simple and cost-effective solution for electronic control, particularly in the construction of prototypes and test assemblies. Due to its compatibility with a wide variety of other electronic components and user-friendly programming using a simplified version of the C and C++ programming languages, it is also suitable for use in prototypes [52,53]. For the human–machine interface, i.e., for controlling the experiment without connecting a computer, an LCD (liquid crystal display) and three push buttons are used, which are embedded in a two-part box. The power supplies for Arduino (5–12 V) and step-per motor controllers (24 V) are separate due to the different voltages required; two separate power supplies are used for this. To limit the travel of the mixer tube, two microswitches with specially designed holders are used to define the end. For wiring, a suitable wiring plan is developed, and cables, stranded wires, wire end ferrules, and DIN rail terminals are procured and used.

In parallel with the procurement of the commercially available products, the individually designed components are manufactured. Due to the expected increased mechanical stress in the mixing unit caused by the drives, the connecting elements between the motors, the linear guide, and the worm gear are manufactured conventionally from aluminum. For the remaining components, the principles of rapid prototyping and rapid manufacturing are applied in order to produce them using additive manufacturing processes. Material extrusion (MEX) is used as the standard process and is particularly suitable for the higher-volume parts, such as the box and the MCM holder, but also the holder for the microswitches. Due to the close tolerances and the positive connection, the two-part shaft adapter for transmitting the rotary movement of the worm gear to the mixer tube is manufactured using SLA. The first of the two parts can therefore be placed laterally on the mixer tube as planned, the second can then be pushed in, and the mixer can be guided through the hollow shaft.

Once all the components identified in the parts list are available, the prototype can be built based on its digital twin. First, the frame is assembled by connecting the individual aluminum profiles with screws, T-nuts, and brackets. The feet are also mounted to ensure stability on the work surface, and then all the cover caps are added. The mixing unit can then be attached. The linear guide is screwed to the aluminum profiles, creating the distance between the two vertically positioned profiles. The remaining parts of the mixing unit are added accordingly. The bracket for the MCM is attached below the mixing unit, and the DIN rail for the electronic components is attached to the rear. The latter are then assembled—Arduino is inserted into a housing and connected to the DIN rail along with the 24 V power supply, the two motor controllers, and the terminals. The microswitches are glued to their brackets and screwed to the sides of the vertically positioned aluminum profiles. The display and buttons are screwed into the lid of the box, which in turn is connected to the box by means of pressed-in magnets. The final step is to wire all electronic components together, with the cables being routed through the grooves in the aluminum profiles and then covered with profiles.

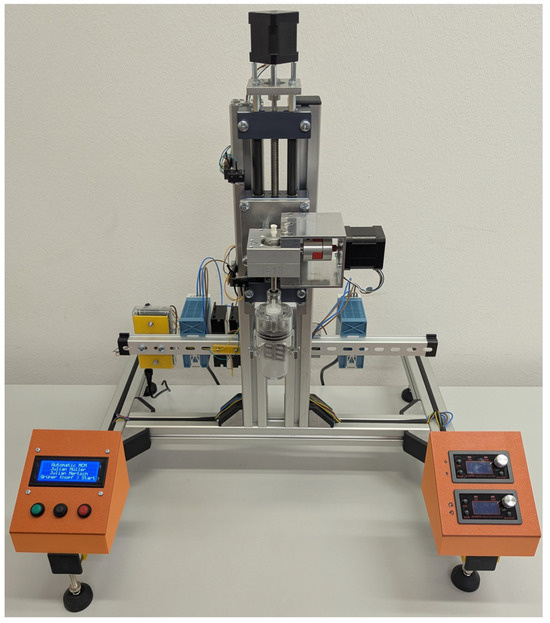

This results in the prototype shown in Figure 5 with the MCM installed. The box on the right contains two additional, unconnected motor controllers, which can be used to manually control the two stepper motors. These were used to simplify manufacturing and allow for different positioning of the mixing unit during the assembly process.

Figure 5.

Finished prototype.

2.3. Testing

To ensure that the structure meets the requirements and can be used for producing samples from the MASON experiments, its functionality is tested. This type of review of the described and defined requirements in the context of the predefined intended use is also referred to as validation.

To verify the functionality of the prototype, experiments based on the MASON experiments are conducted. The primary goal is to determine whether the main requirement of semi-automated execution (see requirements list) is met. For the reasons stated above, the same three mixture compositions are used as in the torque tests—R, RR, and R-SS. The respective components can be found in Table 1. As in the MASON experiments, the dry components are first loosened with the mixer, then water is added, and the mixing is carried out.

Since, in contrast to the torque tests, a combination of rotary and longitudinal movement is now possible, the control system is programmed according to the manual mixing process. The movements of the mixer described in this section are integrated in the program code but can be extended in later developments to include system reactions based on system states reported by sensors. For both dry and wet mixing, the two motors are operated in jog mode, i.e., at a fixed, constant speed, which is 50 rpm when driving the linear guide and 500 rpm when driving the worm gear, resulting in a mixer speed of around 38.5 rpm. Once the MCM has been filled with the dry ingredients and inserted into the switched-on prototype, the first of the two mixing phases is started by pressing the green button. The mixer blade then moves to the upper stop and begins loosening by repeatedly moving the linear guide downwards for 400 ms and then performing a short clockwise and counterclockwise movement. This process is repeated until the lower stop is reached and the mixer blade has reached the bottom of the mixing chamber, which is detected by the linear guide triggering the lower stop. The water is then slowly pumped manually through the mixer tube into the mixing chamber using a syringe. Based on the instructions for the mixing process on the ISS, all components are mixed together for two minutes. For this purpose, both motors run continuously—the linear guide is moved back and forth between the upper and lower stops, while a constant stirring motion takes place. Each time the lower stop is reached, the direction of rotation of the mixer blade reverses to ensure the best possible mixing. After the two minutes have elapsed, the mixer blade stops automatically, and the linear guide moves to the upper stop so that the mixer blade is pulled out of the mixing chamber, and the mixing chamber can be removed with the finished mixed concrete. The MCM and the prototype are visually inspected after each test run, and any observations are documented.

To ensure comparability with the MASON samples, three samples of each composition are produced. To assess the concrete properties, the mixing chambers are sealed and compressed by placing the holding chamber on top and squeezing it shut. After a curing period of 14 days, the samples are removed, subjected to a visual inspection, and subjected to several standard tests to check their mass, dimensions [54], density [55], porosity [56], and compressive strength [57]. The resulting parameters are compared with those of the MASON samples, which were mixed manually using the MCM, to evaluate whether the automated prototype can produce samples of comparable quality and uniformity.

This approach evaluates whether the prototype meets the defined requirements for use and also allows potential for improvement to be identified, which provides direct starting points for further research.

3. Results and Discussion

To validate the successful development and production of the prototype, ten concrete samples were produced using the prototype according to the procedure defined before. The first run with the AMCM was conducted to verify the overall configuration and validate the mixing process. During this run, the sample R-1 was produced and exhibited an inhomogeneous region in the bottom few millimeters of the mixing chamber. This inhomogeneity resulted from an incorrect positioning of the lower microswitch, which prevented the mixer blade from reaching the bottom of the chamber. Following this initial test, the microswitch position was corrected, ensuring that in all subsequent runs the mixer blade could fully reach the bottom of the chamber.

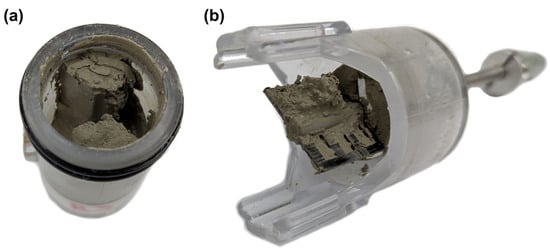

After each mix, the MCM was removed, and the individual components, as well as the mixed, fresh samples, were visually inspected. The properties recorded in Figure 6 are examples of the R mix, a stiff mixture of cement with water. A comparable picture emerges for all three mix compositions.

Figure 6.

MCM after automated mixing: (a) mixing chamber with fresh mixture; (b) retention chamber and mixer blade.

For the nine following samples, all of the mixture components appear to be well blended, resulting in a homogeneous mass. However, the final positioning of the mixer blade is clearly visible in the upper region of the mixture, and a significant amount of the mixture still adheres to the mixer blade after the MCM has been started up and removed from the prototype. This condition is least pronounced in the R-R samples, although these also have the most fluid consistency of the three selected mixtures. Thus, in all tests, no cylindrical shape was created through mixing alone, so compression by placing the retention chamber on top and then squeezing it together is necessary. The imprint of the mixer blade in the upper region can possibly be explained by the fact that the program defines that the mixer blade stops after the mixing time has elapsed and then moves up. During this period, there is no further rotational movement, so the mixer blade leaves an imprint and then moves upwards. This problem was resolved by adjusting the mixing program.

To end the mixing process, the mixer blade does not move all the way to the top of the retention chamber, but only to the upper stop of the mixing chamber, which is set by one of the microswitches. In the MASON tests, a large portion of the material residue still adhering to the mixer blade is wiped off by the sealing lip before the mixer blade is pulled all the way to the top of the retention chamber [9]. This procedure is currently not possible in the automated configuration because, on the one hand, a second upper stop would have to be implemented and, on the other hand, the positioning of the mixer blade would have to be monitored. Although the position of the retention chamber is set by the MCM holder, the stepper motor connected to the worm gear does not save the position. Therefore, the prototype would have to be supplemented with a sensor (mechanical or optical) to ensure that the mixer blade is aligned with the storage chamber and is then pulled all the way to the top to be wiped off the sealing lip. Another possibility to reduce or, ideally, prevent adhesion to the mixer blade would be to research other geometries or materials for the mixer blade.

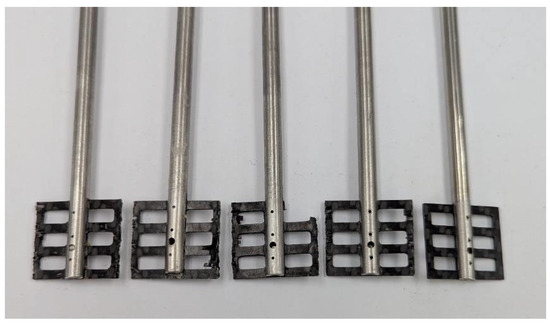

Another problem became apparent after cleaning the components on the carbon mixer blades. Figure 7 shows all five mixer blades used for the nine test mixtures. The original plan was—as in the torque tests—to reuse as many MCM components as possible. However, the mixing process damaged a total of four of the mixer blades in the nine tests, meaning that each one had to be replaced with a new, undamaged one. The damage to the middle mixer blade was particularly severe; one of the ribs had broken off and is now embedded in the test specimen. With the exception of the blade on the far right, all the other blades showed damage on the sides, i.e., where there was only a small gap between the blade and the mixing chamber during mixing. This suggests that this damage is caused by the abrasive mechanisms of larger grains in the mixture compositions. However, since such damage did not occur during the qualification of the MCM in 2021 when conducting the experiments manually, it is necessary to investigate possible causes and how these can be ruled out.

Figure 7.

Mixer blades after the test mixtures.

As part of the investigations for this work, damage to the mixer blades occurred during torque tests. If critical torques of around 2.3 Nm are reached or exceeded, the mixer blade, as the weakest component in the MCM, gives way and, in the worst case, is even destroyed. Since the torque is not monitored in the prototype, it is theoretically possible that this critical torque is reached and thus causes damage to the carbon. However, it should be noted that the mixer blades used for the Cosmic Kiss mission were manufactured in 2021 and are therefore already almost four years old. Various studies have investigated the aging behavior of carbon and carbon composite materials and have concluded that the mechanical properties of the material, in particular, deteriorate significantly over time. However, the exact influence of aging cannot be precisely predicted [58,59,60].

Accordingly, tests would have to be conducted on the existing mixer blades from 2021 as well as new ones, primarily checking their mechanical properties. If aging has occurred, reproducing the mixer blades could be sufficient to prevent further damage. Additionally, other materials and different mixer blade geometries could be investigated for this purpose. For example, a series of tests could be conducted to determine the torques at which the respective mixer blade design fails. In addition, direct or indirect torque monitoring could be used on the prototype to stop the mixing process at maximum torque or reverse the direction of rotation. In manual operation, the operator intuitively reverses the direction of rotation once the resistance becomes too high, thereby preventing the application of critical torque levels. This torque is further limited by the short length of the mixing tool, which would otherwise require substantial manual force to reach such critical conditions. In contrast, the motor of the automated setup applies torque up to its mechanical limit without such feedback or self-limitation, which can lead to material damage, which did not occur during manual operation for the qualification of the MCM in 2021.

Additional tests involving manual mixing were conducted in the meantime. In these experiments, the same mixer blades were used repeatedly to mix the R-SS composition. Similar types of damage were observed on the blades, indicating that the issue is not exclusive to the automated setup, although damage occurs more quickly. Therefore, this issue is not related to manual versus automated operation, but rather to the material properties of the mixer blades. Consequently, alternative materials for the mixing blades are under investigation. This aspect is part of ongoing research and will be addressed in future publications.

Overall, however, it can be stated that the prototype successfully fulfilled its main task and thus the most important requirement—the automated mixing process—in all nine cases. The electronic and mechanical components carry out the exact mixing movement specified by the programmed process. The MCM no longer needs to be operated by a human, thus eliminating human influence on the mixing process. The mixing process can then be adjusted as desired, and experiments can be carried out with different speeds and times for the two phases (loosening the dry ingredients and mixing after adding water). After the successful automation of mixing as a single process step, the prototype can also be expanded to include additional functions, such as automatic injection of water between the two phases or automatic replacement of the filled mixing chamber.

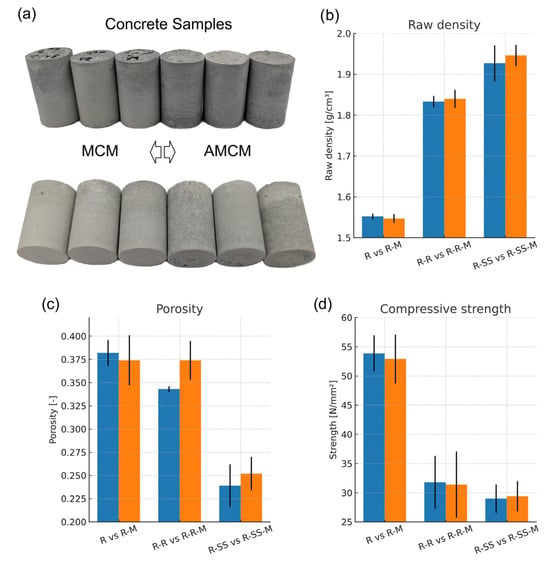

This assessment is also confirmed by the examination of the concrete samples dried and cured for two weeks, shown in Figure 8. Apart from test specimen R-SS 3, none of the cylinders exhibited any major cavities or defects. As already observed in the fresh state, the mixture components were evenly distributed, resulting in homogeneous samples. For comparison, nine further test specimens were produced by hand with the manual MCM and also examined. It can be seen overall that not only similar but above all uniform values were achieved, especially for bulk density and porosity.

Figure 8.

(a) Concrete samples produced by MCM and AMCM (mixture R-R top row, mixture R-SS bottom row). Comparison of concrete sample properties, raw density (b), porosity (c), and compressive strength (d), for 18 samples of the mixtures R, R-R, and R-SS produced with the AMCM (blue bars) and R-M, R-R-M, and R-SS-M produced with the manual MCM (orange bars). Error bars correspond to the standard deviation.

Validation in the form of test mixtures thus shows that the prototype is generally suitable for its intended use. The weaknesses uncovered, such as material adhesion or defects in the mixer blade, provide starting points for further research. To optimize the design, the mixer blade in particular should be redesigned, various mixing processes should be investigated and implemented through reprogramming, and the design should be supplemented with additional sensors for position and performance monitoring.

4. Conclusions

The developed prototype is fully functional and enables uniform sample production on Earth. Due to the fulfillment of all requirements, prototype development can be considered successful. The automation of the mixing process has been implemented and tested through validation. The MCM serves as the basic system in the prototype and is thus integrated into the structure. The use of aluminum profiles and other standard components results in a robust yet modular structure that can be easily adapted for further research approaches. The underlying system structure also serves as the basis for the development of a design for use on the Moon, confirming its adaptability to use in space.

This marks the next step in the MASON project and provides numerous starting points for subsequent investigations. First, the developed design must be optimized and adjusted in some areas. The focus is primarily on the mixer blade, where both geometric and material-related adjustments need to be reconsidered. At this point, it is unclear whether the damage during the tests is due to carbon aging or to the general material properties and geometry. Changing these properties could also prevent or reduce adhesion and thus material loss.

Adjusting the process parameters (mixing sequence, mixing duration, and speed) could also prevent damage to the mixer blade and offers further optimization potential. It has already been studied and shown several times that the mixing process has a significant influence on the properties of the concrete during curing and in its specific application [58,59,60]. Furthermore, minor adjustments, such as raising the mixer blade into the retention chamber, are conceivable as process optimization. However, this would require the prototype to be expanded with additional sensors. Other possible extensions could automate further steps of the experiment or add more. These could include, for example, the automatic injection of water between mixing phases or the compression and compaction of the concrete after mixing. For this purpose, a vibrator could be attached, as for conventional concrete compaction, or a mechanism could be added that automatically compresses the concrete in the mixing chamber. The test mixes have shown that gravity is not sufficient for the tested mixtures to distribute the mixture evenly within the mixing chamber. The water injection could be automated by using a motor to advance the plunger in the syringe. This would also require redesigning the syringe connection, as the syringe would rotate continuously with its current thread.

The main limitation of this study lies in the fact that all validation experiments were conducted under terrestrial conditions; therefore, the system’s performance under microgravity or lunar gravity remains to be demonstrated experimentally. Additional long-duration testing, along with evaluations of diverse mix compositions, is required to fully assess the durability of the mixing components and automation mechanisms.

Once the functional prototype of the AMCM is fully automated, it will be optimized for specific applications in space. A concept for a lunar version—lighter, fully automated, and based on space-qualified components—has already been conceptualized, representing a decisive step toward in situ building material production. This development not only supports sustainable lunar infrastructure but also lays the foundation for future construction technologies on the Moon and beyond.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.H.M., J.T.I.M., S.K. and B.R.; methodology, J.H.M. and J.T.I.M.; software, J.H.M.; validation, J.H.M. and J.T.I.M.; investigation, J.H.M. and J.T.I.M.; resources, J.T.I.M., S.K. and B.R.; data curation, J.H.M. and J.T.I.M., writing—original draft preparation, J.H.M.; writing—review and editing, J.H.M., J.T.I.M., S.K., B.R. and M.S.-H.; visualization, J.H.M. and J.T.I.M.; supervision, J.T.I.M. and S.K.; project administration, J.T.I.M.; funding acquisition, J.T.I.M. and M.S.-H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data generated and analyzed during the current study are available upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the German Aerospace Center for the trusting and constructive collaboration on the MASON project. They furthermore want to express thanks to the laboratory staff of the Institute for Structural Concrete and the Institute of Product Engineering. Thanks are also granted to the MICS team of Pennsylvania State University and NASA for the in-depth discussion. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used DeepL and Google Translate for the purposes of translation and grammar checking. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication. We acknowledge support from the Open Access Publication Fund of the University of Duisburg-Essen.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NASA | National Aeronautics and Space Administration |

| ESA | European Space Agency |

| ISS | International Space Station |

| MASON | Material Science on Solidification of Concrete |

| MCM | MASON Concrete Mixer |

| AMCM | Automated MASON Concrete Mixer |

Appendix A. Torque Tests

Appendix A.1. Mixing Procedure

For the measurements with and without water, a procedure is defined that represents the real mixing process.

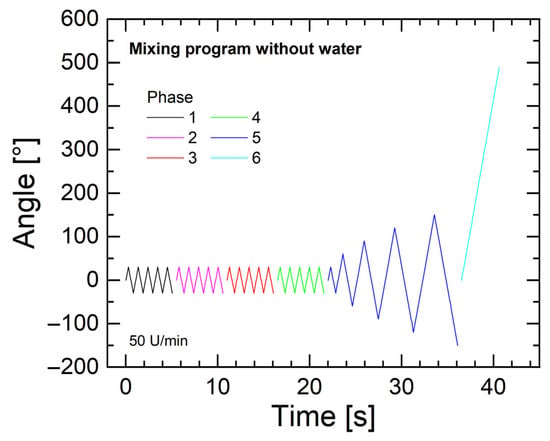

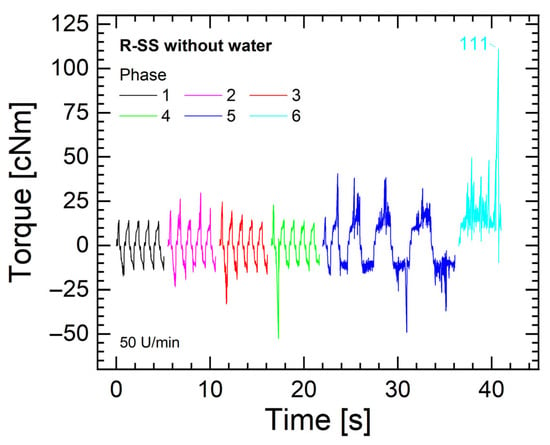

The mixing program for the dry ingredients is shown in Figure A1 using a time-angle diagram and is divided into up to six phases. The phases are separated from one another in the diagram by color and time intervals. During these intervals, the mixer tube is moved longitudinally by hand, as simultaneous rotational and longitudinal movement is neither planned nor possible in this test setup. First, the mixer blade is immersed in the material, and the material is slightly loosened. This process is illustrated in phases 1–4 by a back-and-forth movement of the mixer. Positive values for the angle of rotation indicate a clockwise rotation, while negative values represent a counterclockwise rotation. After a clockwise rotation of 30°, there are five alternating left and right rotations of 60° each within a phase. Between the phases, the mixer blade is always moved a little further towards the bottom of the mixing chamber. Depending on the mixture components, three or four repetitions may be necessary (phase 4 is therefore optional). Once the bottom of the mixing chamber is reached, the mixer blade is moved back a bit, and increasing loosening occurs in Phase 5. Thus, with each change in rotation direction, the subsequent angle of rotation is increased by 30°, as the material becomes looser and more mobile each time. As in the manual tests, a complete rotation of the mixer blade should now be possible (phase 6), so that the material is sufficiently loosened and the mixer tube is positioned correctly for subsequent water injection.

Figure A1.

Torque test process without water.

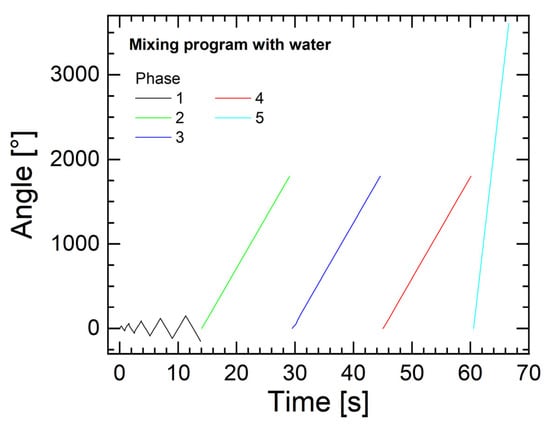

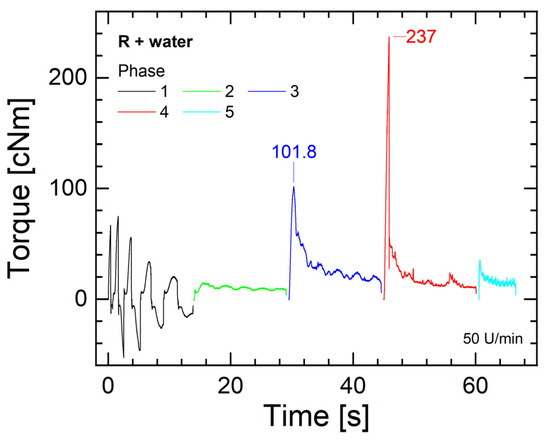

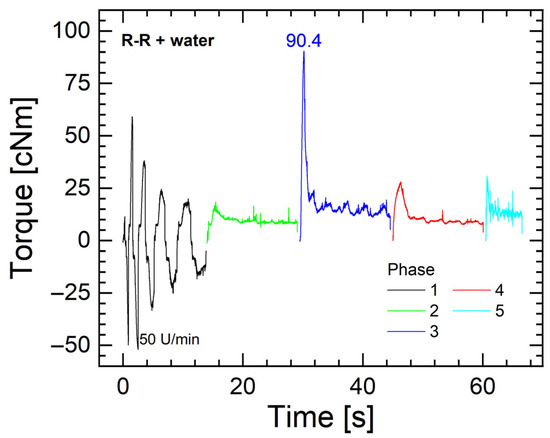

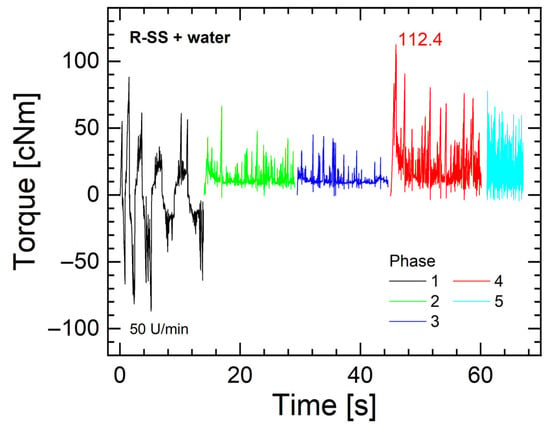

In contrast to the loosening movement during the mixing process without water, a constant mixing movement after the water addition and distribution is crucial. To ensure that the water is initially distributed throughout the mixing chamber, the fifth phase of dry mixing is repeated first. Then, three times, five revolutions each are performed—at the bottom, in the middle, and in the upper area of the mixing chamber, so that the material is thoroughly mixed across the entire sample length. Finally, a further mixing process (phase 5) takes place at twice the speed and rotation speed, i.e., 10 more revolutions are performed at 100 rpm (see Figure A2).

Figure A2.

Torque test process with water.

Data are recorded in real time during the test and is displayed by the associated software. Subsequent evaluation and analysis focus primarily on the maximum torque values achieved, as these significantly influence the design of the necessary hardware.

Appendix A.2. Results of the Torque Tests

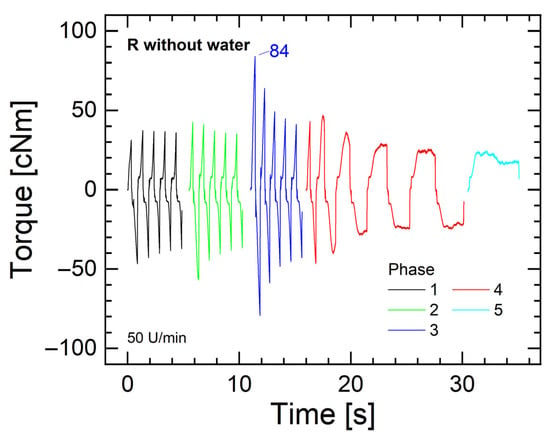

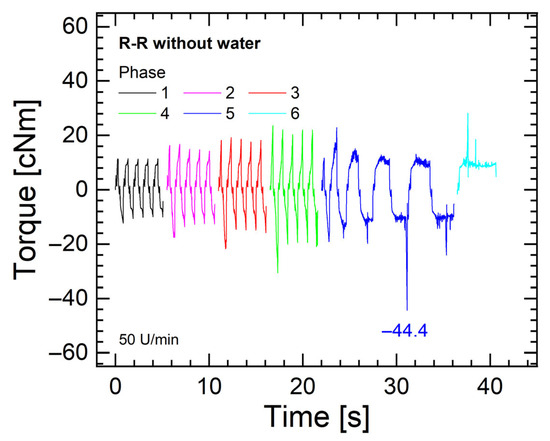

As mentioned, the main part of the torque tests consists of realistic experiments with filled MCMs, with the mixing process being observed both before and after the addition of water. The evaluation focuses on the maximum torques achieved, as these determine the specifications required for the drive unit to drive the MCM. First, the dry components of the three specified mixtures are loosened and mixed according to the procedure in Appendix A.1.

The results for the mixtures are shown in Figure A3, Figure A4 and Figure A5. Since the direction of rotation in these tests changes several times within the phases, it is no longer possible to represent the torque curve in a rotation angle–torque diagram, so that both here and in the tests with water, time is shown as a variable on the x-axis. In order to nevertheless illustrate the relationship, the color representation of the phases is the same as in the program description (see Figure A1). In the result diagrams, both positive and negative torques are recorded, with the sign indicating the direction of rotation—positive torques represent clockwise rotation and negative torques represent anti-clockwise rotation. Therefore, in the subsequent evaluation, the absolute value of the minimum and maximum values must be considered in order to determine the maximum torque occurring (entered as a numerical value in the graphics). In phases 1–5, it is clear that the torque continues to increase until the direction of rotation is reversed, creating a peak at these points. During the continuous rotation in phase 6, however, after an initial sharp increase, the torque stabilizes at a certain value, with individual outliers deviating from this. This curve is similar for all mixtures examined, even though the maximum torque occurs in different phases of the loosening process. For R, the maximum value of 84.0 cNm occurs in the third phase, and thus, the back and forth movement at the bottom of the mixing chamber. For the R-R mixture, the maximum value is 44.4 cNm and is reached in phase 5. The torque maximum for R-SS without water is the highest at 111 cNm and is recorded during the complete rotation in phase 6. For this mixture, the graph is also significantly more unstable.

Figure A3.

Time–torque diagram for R without water.

Figure A4.

Time–torque diagram for R-R without water.

Figure A5.

Time–torque diagram for R-SS without water.

When comparing the three mixes, it is noticeable that in phases 1–4 (R-R and R-SS) and 1–3 (R), progressively higher torques are achieved. This is due to the fact that the mixer blade is increasingly immersed in the material, thus increasing the amount of material surrounding it that needs to be displaced. In phase 5, the achieved torques generally decrease with each change of direction, even though the angle of rotation is increased each time. This could indicate that the mix is becoming increasingly loose. This is particularly evident when loosening the pure cement (R, see Figure A3).

After loosening the dry mixture components, water is injected, and all components are mixed to produce the test specimens. The results for mixing after adding the water to the mixtures are shown in Figure A6, Figure A7 and Figure A8. Again, the maximum torque achieved is considered in each case.

Figure A6.

Time–torque diagram for R with water.

Figure A7.

Time–torque diagram for R-R with water.

Figure A8.

Time–torque diagram for R-SS with water.

The representation is again in a time–torque diagram with color-coded demarcation of the different phases in the mixing process. In this case, however, negative torque values are only reached in the first phase, as all subsequent phases describe a pure clockwise rotation. When mixing with water, the highest values are always reached right at the beginning of the phase. The torque builds up at the beginning of the phase, then drops and remains at a similar level for the remainder of the individual rotational movement. For all mixtures, a higher maximum value is reached than in the tests without water, whereby the order of the different mixtures is the same. The smallest maximum is reached by R-R at 90.4 cNm in phase 3, followed by R at 101.8 cNm, also in phase 3. The highest value is measured at 112.4 cNm for R-SS in phase 4.

In this context, the maximum value of 237.0 cNm shown in Figure A6 must be critically examined and questioned. The corresponding test is the last run, in which the mixer blade is located partially in the storage chamber at the beginning of Phase 4. There, the upper section of the carbon is torn off, which requires a torque of 237 cNm. This value, therefore, does not provide an indication of the torque to be provided by the drive, but does show the limits of the mixer blade, so that such high torques should be avoided in use. For this reason, the second highest torque of 101.8 cNm is adopted as the maximum value for R.

Compared to the other two mixtures, R-SS exhibits significantly greater fluctuations across all phases. Further observations can be linked to the determined torque curves. During the test run, as in the runs without water, an irregular cracking noise can be heard, which creates a strong spike on the torque curve in the real-time monitoring. This noise presumably originates from the large grains in the standard sand, whose diameter is larger than the distance between the mixer blade and the mixing chamber. Thus, the mixer blade strikes one of the grains and must apply a higher torque to move it along with the rest of the mixture.

References

- NASA’s Plan for Sustained Lunar Exploration and Development. Available online: https://www.nasa.gov/feature/nasa-outlines-lunar-surface-sustainability-concept (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- NASA’s Lunar Exploration Program Overview. Available online: https://www.nasa.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/artemis_plan-20200921.pdf (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- Moon Village. Available online: https://www.esa.int/About_Us/Ministerial_Council_2016/Moon_Village (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- Köpping Athanasopoulos, H. The Moon Village and Space 4.0: The ‘Open Concept’ as a New Way of Doing Space? Space Policy 2019, 49, 101323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinton, R.G.; Edmunson, J.E.; Effinger, M.R.; Pickett, C.C.; Fiske, M.R.; Ballard, J.; Jensen, E.; Yashar, M.; Morris, M.; Ciardullo, C.; et al. NASA’s Moon-to-Mars Planetary Autonomous Construction Technology Project: Overview and Status, 73rd ed.; International Astronautical Congress: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Moraes, R.M. The Moon Builders: Practical Solutions to Overcome the Early Challenges in Lunar Construction; Space Geotech Publishing Ltd.: Bengaluru, India, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Cesaretti, G.; Dini, E.; Kestelier, X.D.; Colla, V.; Pambaguian, L. Building components for an outpost on the Lunar soil by means of a novel 3D printing technology. Acta Astronautica 2014, 93, 430–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fateri, M.; Meurisse, A.; Sperl, M.; Urbina, D.; Madakashira, H.K.; Govindaraj, S.; Gancet, J.; Imhof, B.; Hoheneder, W.; Waclavicek, R.; et al. Solar Sintering for Lunar Additive Manufacturing. J. Aerosp. Eng. 2019, 32, 04019101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, J.T.I. Zum Beton in Realer und Simulierter Mikrogravitation. Phd Thesis, University of Duisburg-Essen, Essen, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naser, M.Z. Extraterrestrial construction materials. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2019, 105, 100577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Yu, Z.; Shao, R.; Li, J. A comprehensive review of extraterrestrial construction, from space concrete materials to habitat structures. Eng. Struct. 2024, 318, 18723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bury, M.A.; Blakely, J.R.; Jalbert, L.B.; Mustaikis, S. Concrete and Mortar Research in Microgravity Aboard the NASA Space Shuttle. Concr. Int. 1994, 16, 42–46. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, L.; Meier, M.R.; Rinkenburger, A.; Zheng, B.; Fu, L.; Plank, J. Early Hydration of Portland Cement Admixed with Polycarboxylates Studied Under Terrestric and Microgravity Conditions. J. Adv. Concr. Technol. 2016, 14, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Meier, M.R.; Sarigaphuti, M.; Sainamthip, P.; Plank, J. Early hydration of Portland cement studied under microgravity conditions. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 93, 877–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biopolymer Research for In-Situ Capabilities. Available online: https://www.nasa.gov/missions/station/iss-research/soil-satellites-and-climate-modeling-among-investigations-riding-spacex-crs-25-dragon-to-international-space-station/ (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- Moraes Neves, J.; Collins, P.J.; Wilkerson, R.P.; Grugel, R.N.; Radlińska, A. Microgravity Effect on Microstructural Development of Tri-calcium Silicate (C3S) Paste. Front. Mater. 2019, 6, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, P.J.; Thomas, R.J.; Radlińska, A. Influence of gravity on the micromechanical properties of Portland cement and lunar regolith simulant composites. Cem. Concr. Res. 2023, 172, 107232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, P.J.; Grugel, R.N.; Radlińska, A. Hydration of tricalcium aluminate and gypsum pastes on the International Space Station. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 285, 122919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, J.T.I.; Rattenbacher, B.; Tell, K.; Rösch, C.; Welsch, T.; Maurer, M.; Sperl, M.; Schnellenbach-Held, M. Space hardware for concrete sample production on ISS “MASON concrete mixer”. NPJ Microgravity 2023, 9, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperl, M.; Tell, K.; Rattenbacher, B.; Welsch, T.; Schnellenbach-Held, M.; Müller, J.; Kanthak, S. Mischvorrichtung sowie. Mischsystem. Patent DE 10 2021 128 232 A1, 13 October 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, J.; Welsch, T.; Tell, K.; Rattenbacher, B.; Sperl, M. MASON: Betonerhärtung in Schwerelosigkeit—Simulationen mit dem Klinostaten. Beton Und Stahlbetonbau 2023, 118, 406–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, J.T.I.; Welsch, T.; Schnellenbach-Held, M.; Rattenbacher, B.; Tell, K.; Walls, W.; Sperl, M. Structural Performance of Cement Paste Cylinders Cured in Microgravity on the ISS: Effects of Air-Entraining Agent and Simulated Microgravity Conditions. Prepr. Build. Constr. Mater. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Mazanec, O.; Lowke, D.; Schießl, P. Mixing of high performance concrete: Effect of concrete composition and mixing intensity on mixing time. Mater. Struct. 2010, 43, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juilland, P.; Kumar, A.; Gallucci, E.; Flatt, R.J.; Scrivener, K.L. Effect of mixing on the early hydration of alite and OPC systems. Cem. Concr. Res. 2012, 42, 1175–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dils, J.; Schutter, G.D.; Boel, V. Influence of mixing procedure and mixer type on fresh and hardened properties of concrete: A review. Mater. Struct. 2012, 45, 1673–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rejeb, S.K. Improving compressive strength of concrete by a two-step mixing method. Cem. Concr. Res. 1996, 26, 585–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radlińska, A.; Collins, P.J. MICS Microgravity Investigation of Cement Solidification. In Proceedings of the MASON/MICS Workshop 1, Cologne, Germany, 11 December 2020. [Google Scholar]

- ETD MT41-250-I06. Available online: https://servaid.atlascopco.com/AssertWeb/en-US/AtlasCopco/Catalogue/318771 (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- MicroTorque Smart Integrated Electronics. Available online: https://www.atlascopco.com/content/dam/atlas-copco/local-countries/thailand/documents/Electronics%20Leaflet.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- VDI/VDE 2647:2021-12; Typprüfung von Schraubwerkzeugen; Drehmoment-und Drehmoment-/Drehwinkelprüfung. VDI Verein Deutscher Ingenieure e.V. & Verband der Elektrotechnik, Elektronik, Informationstechnik Beuth: Berlin, Germany, 2021.

- Czichos, H. Measurement, Testing and Sensor Technology—Fundamentals and Application to Materials and Technical Systems, 1st ed.; Springer: Cham, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- ETD MT41-250-I06. Available online: https://servaid.atlascopco.com/AssertWeb/en-US/AtlasCopco/Catalogue/2868 (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- DIN EN 196-1:2016-11; Prüfverfahren für Zement; Teil 1: Bestimmung der Festigkeit. DIN Deutsches Institut für Normung e.V. Beuth: Berlin, Germany, 2016.

- Sicherheitsdatenblatt Portlandzement. Available online: https://alpacem.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/SDB-Zement-chromatarm_AT_7.1_2023.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Engelschiøn, V.S.; Eriksson, S.R.; Cowley, A.; Fateri, M.; Meurisse, A.; Kueppers, U.; Sperl, M. EAC-1A: A novel large-volume lunar regolith simulant. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 5473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favre, E.; Wavre, N.; Gay-Crosier, P.; Verain, M. European electric space rated motors handbook. In Proceedings of the 8th European Space Mechanisms and Tribology Symposium, Toulouse, France, 29 September–1 October 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Drive Systems for Space Applications. Available online: https://www.maxongroup.net.au/medias/sys_master/root/9227156127774/Space-Catalog-2023-EN.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Lekshmi, V.; Varaprasad, B.; Navle Sonal, G.; Vishnu, T.S. Configurable Drive Scheme for Stepper Motors in Space Application. In Proceedings of the First International Conference on Electrical, Electronics, Information and Communication Technologies (ICEEICT), Trichy, India, 16–18 February 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Modreanu, M.; Ionica, I.; Boboc, C. Stepper motors for space applications-ICPE Activities. In Proceedings of the Aerospace Europe 6th CEAS Conference, Berlin, Germany, 3–5 May 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Künne, B. Einführung in die Maschinenelemente—Gestaltung, Berechnung, Konstruktion, 2nd ed.; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Drylin® Lineare Antriebstechnik. Available online: https://igus.widen.net/s/vwgqwlzzjj/de_igus_dry-tech_lin1_2023_katalog_04-01_drylin_antriebstechnik_sht (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- Drylin® E Schrittmotor mit Litzen, NEMA 17. Available online: https://igus.widen.net/content/72wxeildd2/original/DRE_DATA_MOT-AN-S-060-005-042-L-A-AAAA_DE.pdf?u=gqh1pb&download=true (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- Dryve D7, Takt/Richtung Schrittmotor-Steuerung. Available online: https://igus.widen.net/content/mlicqithpj/original/Handbuch-dryve-D7-V1.2-DE.pdf?u=gqh1pb&download=true (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- Garbrecht, F.W. Auswahl von Elektromotoren—Leicht Gemacht—Der Weg von der Anwendungsanalyse Zum Richtig Dimensionierten Elektromotor, 2nd ed.; VDE VERLAG GMBH: Berlin/Offenbach, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sauer, B.; Albers, A.; Deters, L.; Linke, H.; Wallaschek, J.; Poll, G. Konstruktionselemente des Maschinenbaus 2, 9th ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Highlights—Getriebe. Available online: https://www.ganternorm.com/fileadmin/user_upload/downloads/highlights%20produkt-infos/Getriebe.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Conrad, K.-J. Taschenbuch der Konstruktionstechnik, 3rd ed.; Hanser: München, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Highlights—Wellenkupplungen. Available online: https://www.ganternorm.com/fileadmin/user_upload/downloads/highlights%20produkt-infos/wellenkupplungen_2020_de.pdf (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- Feldhusen, J.; Grote, K.-H. Konstruktionslehre; Methoden und Anwendung erfolgreicher Produktentwicklung, 8th ed.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sauer, B. Konstruktionselemente des Maschinenbaus 1. In Grundlagen der Berechnung und Gestaltung von Maschinenelementen, 10th ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Musterprogramme für Ihre Drylin E Motorsteuerung. Available online: https://www.igus.de/motorsteuerung/musterprogramme (accessed on 22 May 2025).

- Malott, J. Accessible Prototyping for KUKA Robotic Arms with Arduino. SSRN J. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maity, I.; Bhattacharya, S.; Bhattacharjee, A.; Bhaumik, S.; Shit, A.; Paul, S.; Gangopadhyay, M. Exploring Arduino based Electronic Circuit Design: A Study of Innovative Applications and Prototypes. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Electronics, Materials Engineering & Nano-Technology (IEMENTech), Kolkata, India, 10–20 December 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Scrivener, K.; Snellings, R.; Lothenbach, B. A Practical Guide to Microstructural Analysis of Cementitious Materials; First issued in paperback ed.; CRC Press: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- DIN EN 1015-10:2007-05; Prüfverfahren für Mörtel für Mauerwerk; Teil 10: Bestimmung der Trockenrohdichte von Festmörtel. DIN Deutsches Institut für Normung e.V. Beuth Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2007.

- Locher, F.W. Cement—Principles of Production and Use; Bau+Technik Gmbh: Düsseldorf, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- DIN EN 12390-3:2019-10; Prüfung von Festbeton; Teil 3: Druckfestigkeit von Probekörpern. DIN Deutsches Institut für Normung e.V. Beuth Verlag GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2019.

- Afzal, A.; Bangash, M.K.; Hafeez, A.; Shaker, K. Aging Effects on the Mechanical Performance of Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Composites. Int. J. Polym. Sci. 2023, 2023, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isa, A.; Nosbi, N.; Che Ismail, M.; Md Akil, H.; Wan Ali, W.F.F.; Omar, M.F. A Review on Recycling of Carbon Fibres: Methods to Reinforce and Expected Fibre Composite Degradations. Materials 2022, 15, 4991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viña, J.; Argüelles, A.; Castrillo, M.A.; García, M.A. Effects of natural aging for eight years on static properties of glass or carbon fibre reinforced polyetherimide. Corros. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2007, 42, 61–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).