Abstract

Explosive volcanic eruptions are key drivers of climate variability, yet their hemispheric-dependent impacts remain uncertain. Using multi-model ensembles from Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) historical data and Decadal Climate Prediction Project (DCPP) simulations, this study examines how the spatial distribution of volcanic aerosols modulates climate responses to Northern Hemisphere (NH), Tropical (TR), and Southern Hemisphere (SH) eruptions. The CMIP6 ensemble captures observed temperature and precipitation patterns, providing a robust basis for assessing volcanic effects. The results show that the hemispheric distribution of aerosols strongly controls radiative forcing, surface air temperature, and hydrological responses. TR eruptions cause nearly symmetric cooling and widespread tropical rainfall reduction, while NH and SH eruptions produce asymmetric temperature anomalies and clear Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) displacements away from the perturbed hemisphere. The vertical temperature structure, characterized by stratospheric warming and tropospheric cooling, further amplifies hemispheric contrasts through enhanced cross-equatorial energy transport and shifts in the Hadley circulation. ENSO-like responses depend on eruption latitude, TR and NH eruptions favor El Niño–like warming through westerly wind anomalies and Bjerknes feedback, and SH eruptions induce La Niña–like cooling. The DCPP experiments confirm that these signals primarily arise from volcanic forcing rather than internal variability. These findings highlight the critical role of aerosol asymmetry and vertical temperature structure in shaping post-eruption climate patterns and advancing the understanding of volcanic–climate interactions.

1. Introduction

The eruption of volcanoes with explosive force is a significant factor in causing climate fluctuations, with profound impacts on ocean dynamics, hydroclimatic conditions, monsoon systems, large-scale atmospheric circulation, and the winter climate of the Northern Hemisphere [1,2,3,4]. During such eruptions, large quantities of sulfurous gases are injected into the stratosphere, where photochemical reactions gradually produce sulfate aerosols. By absorbing and scattering solar radiation, sulfate aerosols decrease direct solar radiation at the ground level, and the resultant surface temperature decline leads to a slowdown in atmospheric moisture dynamics globally [1,2,5].

Much research has focused on modeling the impacts of tropical volcanic eruptions, highlighting their role in reducing monsoonal precipitation by suppressing the ascending branch of the Hadley Cell, shifting the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) equatorward, and modulating ENSO dynamics [6,7,8,9]. Although volcanic eruptions have been shown to influence El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) variability, most modeling efforts have primarily focused on tropical eruptions. In comparison, the climatic impacts of volcanic eruptions occurring in either the Northern or Southern Hemisphere remain underexplored [10,11,12,13]. Yet, studies suggest that the climate response to volcanic forcing is closely tied to the latitudinal distribution of stratospheric sulfate aerosols, leading to spatially asymmetric climate effects [14,15,16,17]. The spatial pattern of stratospheric sulfate aerosols resulting from volcanic eruptions varies depending on eruption location and dynamics. Such differences in aerosol loading are expected to induce distinct climate responses, with high-latitude climate effects generally affected by the regions of volcanic forcing.

The ENSO-like response to volcanic forcing remains a complex and inconclusive issue, with multiple mechanisms suggested in the literature to account for the diversity of model results and observations. One proposed mechanism involves oceanic processes, the preferential cooling in the western Pacific reduces the zonal sea surface temperature (SST) gradient, a process often referred to as the “ocean dynamical thermostat” [18,19]. Another explanation focuses on the land–ocean thermal contrast following volcanic eruptions, resulting from the faster radiative cooling of continental surfaces after eruptions. This gradient can initiate westerly wind anomalies in the western equatorial Pacific, triggering El Niño–like conditions through the Bjerknes feedback [20,21,22]. Additionally, atmospheric teleconnections associated with a weakened West African monsoon may alter the Walker circulation, leading to El Niño–like anomalies [23]. Finally, changes in wind stress curl during the eruption year, as part of the recharge-discharge theory of ENSO, have also been suggested as a key trigger for post-eruption ENSO-like responses [10].

In addition, volcanic impacts have been linked to broader modes of variability, such as the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) and Arctic Oscillation, through stratosphere–troposphere coupling and modifications of polar vortex strength [24]. These stratospheric pathways can further shape regional climate responses, especially in high-latitude winters, underscoring the need for a more integrative assessment that considers multiple modes of variability. Despite these advances, the underlying dynamics of ENSO-like and extratropical responses remain uncertain.

Previous research investigating volcanic impacts on climate has relied on single-model ensemble simulations. Significant advances in climate modeling capabilities have emerged, particularly through the Coupled Model Intercomparison Projects Phase 5 (CMIP5) [25]. Building upon this, CMIP6 further enhanced the modeling capability by incorporating large ensemble simulations with historical forcing across various models [26]. These developments collectively provide an unprecedented framework for systematically assessing the robustness of forced climate responses across multiple models and realizations [17]. This advancement represents a critical step forward in understanding the complex interactions between volcanic forcing and polar climate dynamics.

Although a previous study [11] showed distinct El Niño responses to volcanic forcing across latitudes, the author used single-model ensemble experiments. From a modeling perspective, large-ensemble simulations are the most effective approach for isolating volcano-induced signals from internal climate variability [10,27,28]. However, most existing studies have focused on interannual scale responses, leaving short-term processes, such as monthly evolution, less explored. This study leverages the CMIP6 multi-model ensemble to investigate ENSO-like responses to Tropical, Northern Hemisphere, and Southern Hemisphere volcanic eruptions. By analyzing both the spatial and temporal characteristics of climate anomalies, this study aims to elucidate the mechanisms driving these responses and contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the climatic impacts of volcanic eruptions. The findings are expected to inform improvements in the representation of volcanic forcing in climate models.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Models and Experiments

This study utilizes outputs from the historical simulations of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) to analyze monthly mean surface air temperature (SAT), sea surface temperature (SST), precipitation, and 850 hPa wind components (i.e., zonal and meridional winds). The CMIP6 models analyzed in this study and listed in Table 1 were selected to ensure a consistent and robust assessment of volcanic climate responses. Model selection was based on the availability of continuous historical simulations covering 1850–2014, a complete set of required variables, and a minimum of 10 ensemble members.

The historical simulations span the period 1850–2014 (Table 1) and are integrated with both anthropogenic and natural (solar and volcanic) forcing. For each model, at least 10 ensemble members of the historical experiments were selected, using different versions of perturbed physics configurations to provide the full set of variables required for this analysis.

To assess the role of internal variability and to isolate the climatic response to volcanic forcing, we analyze simulations from the CMIP6 Decadal Climate Prediction Project (DCPP) [29], following protocols A and C (Table 2). DCPP-A consists of 10-member ensembles of 10-year-long retrospective predictions initialized from observation-based states every year from 1960 to 2018 combined with CMIP6 historical radiative forcing, including volcanic aerosols. In contrast, DCPP-C repeats the same initialized predictions for major volcanic events (Mount Agung in 1963, El Chichón in 1982, and Mount Pinatubo in 1991) but replaces the volcanic forcing with a background aerosol climatology averaged over 1850–2014. The volcanic impact is quantified by differentiating paired simulations with and without volcanic aerosols (DCPP-A minus DCPP-C), thereby effectively separating the forced volcanic response from internal climate variability.

To evaluate the model performance, observational datasets are employed, including HadCRUT5 [30] for near-surface temperature and the Global Precipitation Climatology Centre’s (GPCC) [31] Full Data Reanalysis Version 6 for precipitation. HadCRUT5 is the latest version of the Hadley Centre Climatic Research Unit global surface temperature dataset, providing near-surface air temperature anomalies based on a combination of land station and marine observations, together with an ensemble-based estimate of observational uncertainty. Precipitation is evaluated using the GPCC Full Data Reanalysis Version 6, which is constructed from quality-controlled rain gauge observations and provides a reliable reference for assessing climatological precipitation patterns and large-scale variability simulated by climate models.

All selected models include the major volcanic eruptions since the 1850s, which form the basis of this study. Volcanic forcing in the historical simulations is prescribed using the CMIP6 standard dataset, with stratospheric aerosol optical properties referenced at the 550 nm wavelength, following the climatology of Thomason et al. [32]. For the analysis of spatial patterns, all model outputs are bilinearly interpolated onto a uniform 2.5° × 2.5° grid, to which a consistent land–sea mask is applied.

Table 1.

CMIP6 models and ensemble members of the historical simulations used in this study.

Table 1.

CMIP6 models and ensemble members of the historical simulations used in this study.

| Model Name | Institution | Volcanic Forcing |

|---|---|---|

| ACCESS-CM2 | Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Climate System Science | Interactive |

| ACCESS-ESM1-5 | Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Climate System Science | Sato et al. [33] |

| CanESM5 | Canadian Centre for Climate Modelling and Analysis | Interactive |

| CESM2 | National Centre for Atmospheric Research | Neely and Schmidt [34] |

| CNRM-CM6-1 | National Center for Meteorological Research | Thomason et al. [32] |

| GISS-E2-1-G | National Aeronautics and Space Administration | Thomason et al. [32] |

| GISS-E2-1-H | National Aeronautics and Space Administration | Thomason et al. [32] |

| INM-CM5-0 | Russian Academy of Science | Interactive |

| IPSL-CM6A-LR | Institute Pierre Simon Laplace | Thomason et al. [32] |

| MIROC-ES2L | Atmosphere and Ocean Research Institute | Interactive |

| MIROC6 | Atmosphere and Ocean Research Institute | Thomason et al. [32] |

| MPI-ESM 1-2-HR | Deutsches Klimarechenzentrum | Interactive |

| MPI-ESM 1-2-LR | Deutsches Klimarechenzentrum | Interactive |

| MRI-ESM 2-0 | Meteorological Research Institute | Thomason et al. [32] |

| NorCPM1 | Korea Meteorological Administration | Thomason et al. [32] |

| UKESM1-0-LL | Korea Meteorological Administration | Interactive |

Table 2.

CMIP6 DCPP-A and DCPP-C simulations and runs used in this study.

Table 2.

CMIP6 DCPP-A and DCPP-C simulations and runs used in this study.

| Model Name | Initialization | Institution | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| EC-Earth3 | Full-field | Barcelona Supercomputing Center | Bilbao et al. [35] |

| CESM1-1-CAM5-CMIP5 | Full-field | National Centre for Atmospheric Research | Yeager et al. [36] |

| CMCC-CM2-SR5 | Full-field | Centro Euro-Mediterraneo sui Cambiamenti Climatici | Nicolì et al. [37] |

| CanESM5 | Full-field | Canadian Centre for Climate Modelling and Analysis | Sospedra-Alfonso et al. [38] |

| HadGEM3-GC31 | Full-field | UK Meteorological Office | Williams et al. [39] |

2.2. Classification of Volcano Events

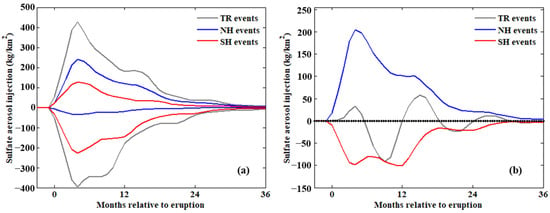

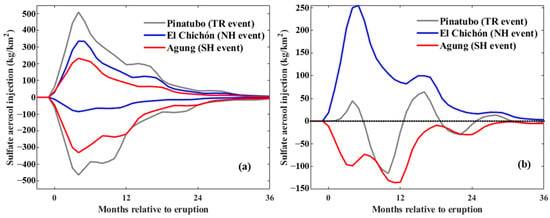

Volcanic eruptions are grouped into three classes according to their stratospheric aerosol dispersal patterns across latitudes, as different eruptions produce distinct hemispheric aerosol patterns. Given the sensitivity analysis performed, we focus on volcanic eruptions with a Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI) ≥ 4. The classification is performed according to the ratio of aerosol loading between the Northern and Southern Hemispheres, following approaches similar to Liu et al. [40] and Stevenson et al. [41]. Based on the distributions of volcanic aerosols in the Northern and Southern Hemispheres, events with an aerosol ratio greater than 1.3 are classified as Northern Hemisphere (NH) events, those with a ratio below 0.7 as Southern Hemisphere (SH) events, and those between 0.7 and 1.3 as Tropical (TR) events. The latest volcanic aerosol reconstruction dataset [42] is used for this classification. All volcanic events between 1850 and 2000 were identified, with 3 NH events, 2 TR events, and 2 SH events (Table 3). The monthly evolution of hemispheric sulfate aerosol loading for the three eruption categories, as well as the interhemispheric loading asymmetry, is presented in Figure 1.

Table 3.

Summary of volcanic eruptions since 1850 included in this study.

Figure 1.

Hemispheric sulfate loading for the three types of volcanic events and the interhemispheric loading difference. (a) Monthly mean hemisphere sulfate loading for each type. (b) The difference in sulfate loading between hemispheres (Northern Hemisphere minus Southern Hemisphere).

There is a limitation in classifying volcano type according to the sulfate dataset. For most historical events, the precise eruption season is unknown and thus the eruption month is artificially set to April [43]. Since the climatic and dynamic responses to volcanic forcing are highly sensitive to the timing of the eruption, this assumption may introduce a bias toward the climatic effects of eruptions occurring in the boreal spring. Moreover, it is the distribution of aerosol loading in the stratosphere, not necessarily the geographic location of the volcano, that plays a critical role in shaping the climate response. The interhemispheric asymmetry in sulfate aerosols has been shown to significantly influence the hydrological cycle, atmospheric energy balance, and other aspects of climate variability.

2.3. Superposed Epoch Analysis

To assess the relationship between volcanic eruptions and climate variability, we employ Superposed Epoch Analysis (SEA) [44,45]. SEA is a widely used statistical technique for quantifying climatic responses to discrete events such as volcanic eruptions [46,47]. It has been extensively applied in both climatology and dendroclimatology to investigate the impacts of volcanic forcing on various climate variables [45,48,49]. SEA requires two independent datasets. The first is an event list, typically the years of identified volcanic eruptions. The second variable is a long, continuous, and evenly sampled time series, such as instrumental climate records or paleoclimate reconstructions. The fundamental assumption of SEA is that these discrete events either influence, or are associated with, specific patterns in the continuous time series. By aligning and averaging the data across all selected events, SEA aims to enhance the signal-to-noise ratio, thereby isolating the sign, magnitude, and timing of the event-related climate response.

Annual and monthly data are categorized based on the timing of volcanic events listed in Table 2. The year with peak volcanic aerosol mass is assigned as year 0, with the compositing window defined from 4 years prior to the eruption to 7 years after. For each grid cell, relative climate responses are calculated as anomalies from the 5-year pre-eruption mean specific to each volcanic event. This reference period helps to minimize the influence of low-frequency variability on the results and reduces the risk of bias in the composite mean due to individual large events [50].

3. Results

3.1. Model Performance and Evaluation

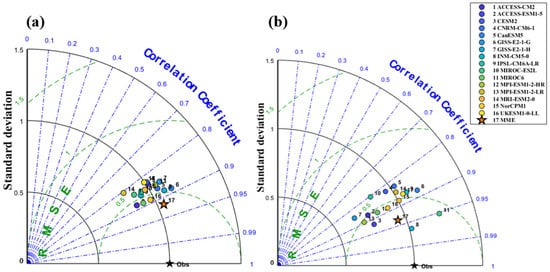

The CMIP6 models exhibit varying abilities in reproducing the observed climatological patterns of SAT and precipitation. To better understand the inter-model spread in volcanic response, we evaluated the climatological performance of each model using Taylor diagrams. Most models capture the large-scale distribution of SAT reasonably well, with correlation coefficients between 0.8 and 0.91 and normalized standard deviations close to unity (Figure 2a). The precipitation simulations show larger inter-model spread (Figure 2b), mainly reflecting the difficulty in reproducing tropical convection and ITCZ patterns. Relative to the single-model result, the multi-model ensemble mean (MME) exhibits improved performance in simulating the spatial patterns of surface air temperature as well as precipitation. These results indicate that the CMIP6 ensemble provides a reasonable representation of the observed climatology, although uncertainties in tropical precipitation remain.

Figure 2.

Taylor diagram of the performance of CMIP6 models for simulating (a) surface air temperature and (b) precipitation climatology during 1980–2000, relative to observations. The reference observation is marked by a black five-pointed star at a correlation of 1 and normalized standard deviation of 1. Better model performance corresponds to smaller RMSE values and correlation (COR) and standard deviation (SD) values closer to 1.

3.2. Radiative Forcing and SAT Response

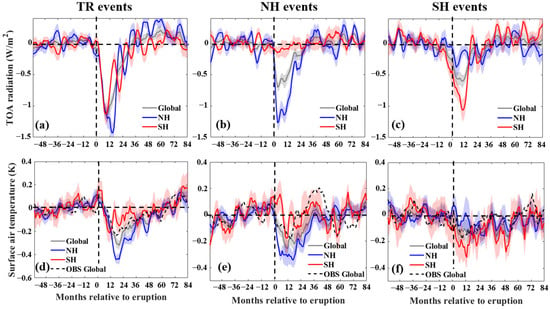

The net top of atmosphere (TOA) radiation flux and surface air temperature (SAT) response to the three types of volcanic events are shown in Figure 3. To illustrate the dominant radiative impacts of volcanic aerosols, we analyze the time series of net TOA radiation flux. The TOA radiative flux reaches its maximum negative anomaly within the first year after the eruption. Subsequently, the anomaly gradually diminishes, returning to near-zero levels by years 3 to 4 post-eruption (Figure 3a–c). Shaded bands in Figure 3 represent the 95% confidence intervals across models, showing the robustness of the ensemble-mean responses. SAT anomaly associated with tropical, northern, and southern volcanoes are shown in Figure 3d–f. Significant cooling occurs after the volcanic eruptions, with the strongest temperature reductions typically occurring in the year following the eruption (year +1), persisting for approximately 2 to 3 years, and subsequently recovering in approximately 5 years. In addition to the model ensemble mean and confidence intervals, we also include HadCRUT5 observational data as a reference, which shows a consistent post-eruption cooling tendency with the simulated SAT responses.

Figure 3.

Top of atmosphere radiation (a–c) and surface air temperature response (d–f) response to the three types of volcanic events, averaged globally (grey), northern hemispherically (blue), and southern hemispherically (red). HadCRUT5 is used as the observational reference (dashed line). Shadings represent 95% confidence intervals of the ensemble means. All the quantities are smoothed by a 5-month running average.

The TR events show little difference between the Northern and Southern Hemisphere flux anomalies (Figure 3a); nonetheless, the hemispheric mean TOA radiation anomalies display notable variations on the annual timescale. This seasonal modulation arises because solar radiation is scattered more effectively in the summer hemisphere than in the winter hemisphere, even when the aerosol burden is similar across both hemispheres. It should be noted that this interpretation is contingent on the prescribed eruption; most eruptions are assumed to occur in April due to the lack of data on the precise historical eruption month. Consequently, the diagnosed hemispheric contrast reflects a boreal spring–summer initialization; eruptions occurring in other seasons could produce different seasonal and hemispheric radiative responses. However, SAT responses exhibit clear hemispheric differences (Figure 3d), which are primarily attributed to the unequal distribution of land and ocean between the hemispheres. Because land has a lower heat capacity and responds more rapidly to radiative perturbations than oceans, surface cooling tends to be stronger and more persistent over the land-dominated hemisphere, influencing the hemispheric SAT contrast following volcanic forcing [15,51].

The NH events show strong hemispheric volcanic forcing, with the TOA radiation anomaly much stronger in the NH than SH (Figure 3b). This asymmetric forcing leads to interhemispheric differential cooling, resulting in a stronger SAT response in the NH (Figure 3e). The amplified surface cooling in the NH is further enhanced by the larger land fraction in the Northern Hemisphere, which responds more rapidly to radiative perturbations than the ocean. Consequently, the SAT anomalies following NH eruptions are significantly greater in the NH than in the SH.

The SH events exhibit a meridional forcing structure opposite to that of NH events, with stronger radiative forcing concentrated in the SH (Figure 3c). As a result of the larger TOA radiative flux anomaly in the SH, the corresponding SAT response is also more pronounced in the SH compared to the NH (Figure 3f).

Although the maximum negative TOA radiative anomaly occurs within the first year after the eruption, the strongest SAT cooling typically lags by several months and peaks around year +1. This temporal offset reflects the thermal inertia of the climate system, especially the role of the ocean in integrating radiative perturbations. As a result, SAT anomalies persist longer than TOA radiative anomalies, leading to a slower recovery of surface temperatures.

The response to the three types of volcanic events are broadly consistent with the results of Pausata et al. [52], who use idealized simulations with NorESM1-M to assess asymmetric hemispheric cooling. While previous studies often relied on single-model or idealized simulations, our analysis, based on a large CMIP6 multi-model ensemble, demonstrates that these asymmetric cooling responses are robust across models and not strongly model dependent.

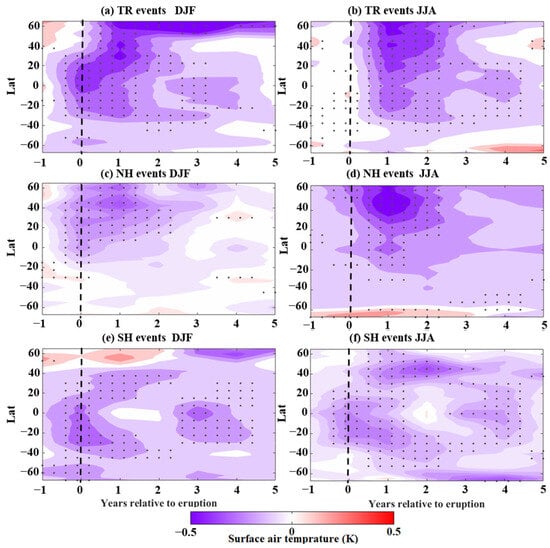

To further understand the response by latitude, we determined the zonally averaged temperature anomaly for different types of eruptions, as document in Figure 4. The TR events have comparable excursions in the NH and SH, with slightly stronger results in the NH than SH. The interhemispheric asymmetry in radiative forcing leads to contrasting surface temperature responses following NH events and SH events. In the tropics, SAT anomalies generally diminish and become negligible within 3–4 years after the eruption. However, an interesting feature of the SAT response is its longer persistence in the Northern Hemisphere extratropics compared to the tropics. This extended cooling is likely associated with larger internal variability driven by synoptic-scale weather systems, as well as feedback processes such as ice–albedo interactions in high-latitude regions [15,53].

Figure 4.

Temporal composites of zonally averaged surface air temperature for (a,b) tropical, (c,d) northern, and (e,f) southern volcanic eruptions. The vertical black line indicates the onset of the volcanic event. The stippled areas in the figure indicate that the response passed the Monte Carlo test at a 95% confidence level.

3.3. Precipitation and Zonal-Mean Response

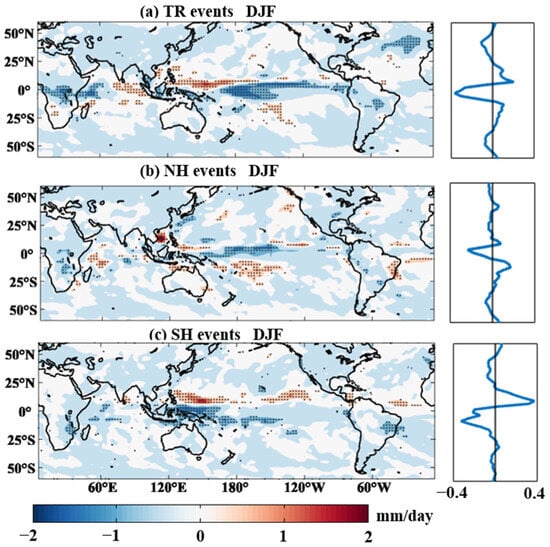

Figure 5 shows the precipitation anomalies after the first winter following the eruptions. The TR events lead to a broad reduction in precipitation across the tropics, with weaker zonal coherence and slight increases in subtropical regions. In contrast, the NH and SH events induce a pronounced displacement of the ITCZ away from the hemisphere of the eruption, accompanied by significant precipitation changes in the tropics and subtropics. These features are consistent with previous single-model and idealized studies [2,54], which reported a weakly coherent tropical precipitation reduction for symmetric eruptions. The ITCZ shift in NH and SH events tends to result in precipitation increases in the hemisphere that is least forced.

Figure 5.

Precipitation anomalies following (a) tropical, (b) northern, and (c) southern volcanic eruptions in the first winter (DJF) after eruptions. Zonally asymmetric component responses are shown in the map, and the side panels show the zonal mean response. The stippled areas in the figure indicate that the response passed the Monte Carlo test at a 95% confidence level.

The zonal-mean precipitation responses are further illustrated in Figure 5 in the right panels. For tropical eruptions, the zonal-mean precipitation anomaly shows a reduction in the tropics and a slight increase in the subtropics, consistent with the symmetric cooling effect. For NH and SH eruptions, the ITCZ shifts away from the forced hemisphere, leading to asymmetric precipitation changes. This asymmetric response is driven by the interhemispheric temperature gradient induced by the volcanic forcing, which alters the atmospheric circulation and redistributes tropical precipitation.

The latitudinal distribution of precipitation responses differs significantly from that of surface temperature. TR eruptions induce a distinct precipitation response, characterized by substantial rainfall reduction in tropical regions and modest decreases at high latitudes, coupled with enhanced subtropical precipitation. This pattern markedly differs from the “wet-gets-wetter” paradigm characteristic, of greenhouse gas-driven warming scenarios [55]. In contrast, the hemisphere-asymmetric eruptions (NH events and SH events) exhibit a distinct pattern, where precipitation is significantly suppressed in the hemisphere with enhanced stratospheric aerosol loading while concurrently increasing over the opposite hemisphere. This hemispheric asymmetry in rainfall response is evident in both tropical and subtropical regions.

3.4. ENSO-like Response

The space–time evolution of the climate response to volcanic eruptions is closely linked to the structure of sulfate aerosol forcing and is often accompanied by ENSO-like variations. These responses typically persist for several years following an eruption. While many studies have documented the occurrence of ENSO-like anomalies in the aftermath of volcanic events, the characteristics and mechanisms of this response remain inconsistent across different analyses [13,56,57].

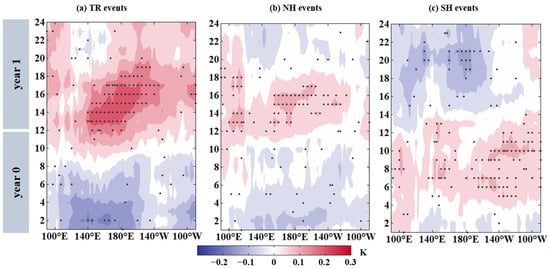

To understand the ENSO response to the TR events, NH events, and SH events, we present the tropical Pacific relative SST anomalies (SSTA) over a 2-year period. To separate the dynamic ENSO response from the background volcanic cooling effect, relative SST anomalies are calculated as deviations from the tropical mean SST (20° N–20° S), following the methodology of Khodri et al. [23]. Figure 6 shows the longitude-time sections of the relative sea surface temperature (RSST) anomaly for the three types of volcanic events over the 2-year period. For the TR events and NH events, significant positive RSST anomalies develop in the central and eastern Pacific in the year following the eruption (year 1), indicative of El Niño–like warming. For the SH events, the response is the opposite, with positive RSST anomalies in year 0 and negative anomalies in year 1, resembling La Niña–like cooling. These results show the contrasting ENSO-like responses to different eruption types, with TR and NH eruptions favoring El Niño–like conditions and SH eruptions favoring La Niña–like conditions.

Figure 6.

Longitude-time sections of relative sea surface temperature (RSST) anomaly along the equatorial regions over the 2-year period following (a) tropical, (b) northern, and (c) southern volcanic eruptions in CMIP6. The stippled areas in the figure indicate that the response passed the Monte Carlo test at a 95% confidence level.

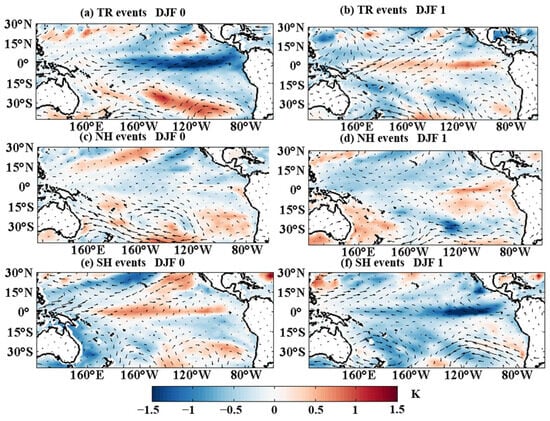

The spatial distribution of SST anomalies and 850 hPa wind anomalies during the first two winters (DJF) following the eruptions further elucidate these responses (Figure 7). Following TR events (Figure 6a), a pronounced cold SST anomaly dominates in year 0 after the eruption, which is likely associated with the direct radiative cooling induced by the volcanic aerosol cloud. For TR events and NH events in year 1, warm SST anomalies develop in the eastern Pacific, forming a clear El Niño–like pattern. This warming is associated with westerly wind anomalies, and warm SSTs begin to develop from the eastern Pacific, associated with the westerly wind anomalies via the Bjerknes feedback. After SH events, cold SST anomalies emerge in the eastern Pacific, consistent with a La Niña–like pattern; the associated enhanced upwelling inhibits the development of warm SST anomalies, again mediated by the Bjerknes feedback process [11].

Figure 7.

SST anomaly (shading) and 850 hPa wind anomalies (vectors) following (a,b) tropical, (c,d) northern, and (e,f) southern volcanic eruptions in the first two winters (DJF) after the eruptions. The “0” denotes the eruption year, and “1” indicates the first post-eruption year.

4. Discussion

4.1. Vertical Structure of Temperature Anomalies and Mechanisms of Volcanic Eruptions

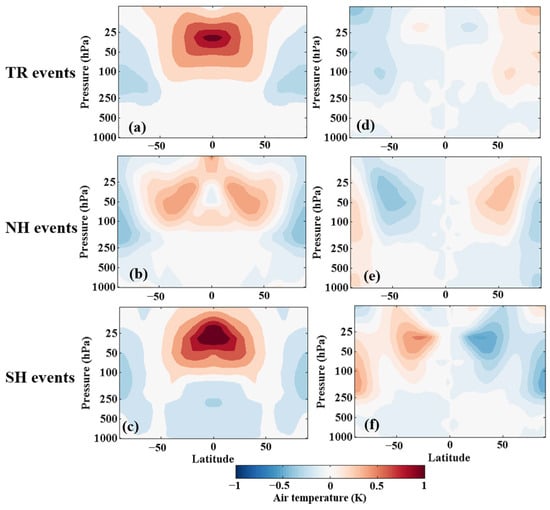

The latitude–height cross sections of temperature anomalies provide further insight into the mechanisms of climate response to different volcanic forcing patterns (Figure 8). The latitude–height structures reveal that the climate response to volcanic eruptions is strongly shaped by the meridional distribution of stratospheric aerosol heating. All eruption types exhibit a characteristic pattern of stratospheric warming and tropospheric cooling, but the amplitude and hemispheric structure vary substantially with eruption type, in agreement with the idealized and single-model results reported by a previous study [13]. Our multi-model CMIP6 analysis further demonstrates that these vertical and hemispheric response patterns are robust across different eruption types and model configurations.

Figure 8.

Latitude–height cross sections of temperature anomalies following different types of volcanic eruptions in CMIP6 models. The first column shows the hemispherically symmetric component, and the second column shows the hemispherically antisymmetric component. Panels (a,d) correspond to TROP events, (b,e) to NH events, and (c,f) to SH events, representing the average temperature anomalies during the first year after the eruptions.

Tropical eruptions generate a largely symmetric vertical structure, reflecting efficient aerosol transport by the Brewer–Dobson circulation. This symmetry indicates that their climate impacts arise primarily from a global radiative deficit rather than hemispheric energy imbalances, consistent with relatively small cross-equatorial circulation shifts. In contrast, northern and southern eruptions produce pronounced asymmetric anomalies, with stronger lower-stratospheric warming in the erupting hemisphere. This hemispheric temperature contrast enhances cross-equatorial energy transport and drives shifts in the Hadley circulation and subtropical jets. The strong antisymmetric component therefore explains why extratropical eruptions often yield regionally focused and circulation-dominated responses. These results highlight that the vertical distribution of stratospheric heating governs how volcanic forcing projects onto large-scale circulation. The mechanisms discussed here underscore the need to account for volcanic forcing structure when interpreting past climatic impacts or comparing model responses within CMIP6.

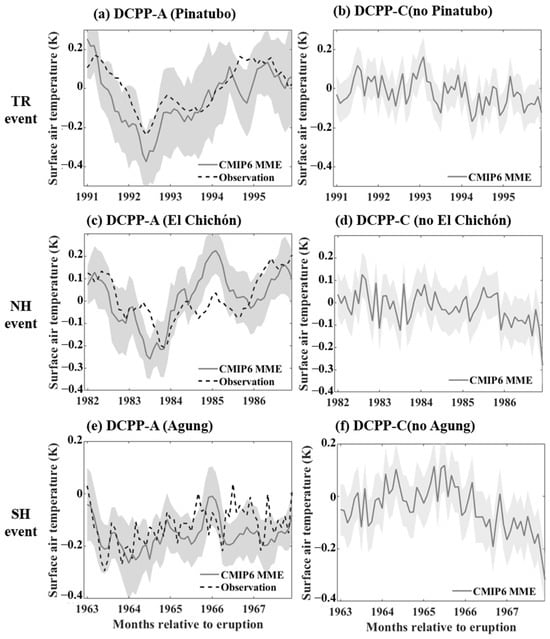

4.2. Contribution of Internal Variability Based on DCPP Experiments

The climatic anomalies observed following volcanic eruptions, including surface cooling, precipitation shifts, and ENSO-like variability. They are often attributed to the radiative effects of volcanic aerosols. However, distinguishing volcanic-forced responses from internal climate variability remains a critical challenge. To address this, we utilized the CMIP6 DCPP-A (with volcanic forcing) and DCPP-C (without volcanic forcing) experiments, which provide controlled simulations with and without volcanic forcing (Table 4; Figure 9). These experiments allow us to isolate the impact of volcanic aerosols from internal variability. Surface air temperature (SAT) anomalies in the DCPP experiments reveal a clear signal of volcanic forcing. In simulations with volcanic forcing, significant cooling is observed across all three eruption types (TR, NH, and SH), with maximum anomalies occurring in the first year and persisting for 2–3 years. Shaded bands in Figure 10 indicate the 95% confidence intervals across ensemble members, showing the robustness of the simulated response. In contrast, simulations without volcanic forcing exhibit only minor fluctuations, consistent with internal variability (Figure 10). HadCRUT5 observational data are included as a reference and reproduce the overall post-eruption cooling tendency captured by the DCPP-A experiments, which strengthens the conclusion that the observed cooling is primarily driven by volcanic aerosols rather than natural climate variability.

Table 4.

List of the volcanic eruptions used in CMIP6 DCPP.

Figure 9.

Hemispheric sulfate loading for the three volcanic events and the interhemispheric loading difference. (a) Monthly mean hemisphere sulfate loading for each event. (b) The difference in sulfate loading between hemispheres (Northern Hemisphere minus Southern Hemisphere).

Figure 10.

Surface air temperature (SAT) anomalies from the DCPP-A experiments (with volcanic forcing) and DCPP-C experiments (without volcanic forcing) for (a,b) Pinatubo, (c,d) El Chichón and (e,f) Agung eruptions. HadCRUT5 is used as the observational reference (dashed line). Shadings represent 95% confidence intervals of the ensemble means.

4.3. Uncertainties and Limitations

While our study provides robust evidence linking SAT anomalies to volcanic forcing, several limitations and uncertainties should be acknowledged. First, the response to volcanic eruptions may be modulated by background climate variability, such as the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO). For example, volcanic eruptions occurring during different ENSO phases may amplify or dampen the simulated ENSO-like responses. Second, potential biases in the forcing datasets need to be considered. In particular, the uncertainties in reconstructed volcanic aerosol optical depth (AOD) datasets may affect both the magnitude and spatial distribution of radiative forcing. Third, assumptions regarding eruption timing, for instance, prescribing April as the eruption month for all events, could introduce artificial seasonality in the modeled responses. Fourth, although superposed epoch analysis (SEA) is effective for detecting average responses, it may not fully isolate robust signals when the number of eruptions is limited or when internal variability coincides with volcanic events. Finally, the DCPP experiments are based on a relatively small number of ensemble members, which may underestimate the spread of internal variability and the uncertainty range of volcanic impacts.

Recognizing these limitations is important for interpreting our results. Future work should therefore (1) employ improved volcanic forcing reconstructions and large ensembles to better capture uncertainty, (2) explicitly account for eruption seasonality and background climate states, and (3) explore the interactions between volcanic forcing and other climate drivers, such as greenhouse gas increases and decadal-to-multidecadal variability. Addressing these issues will help refine our understanding of volcanic impacts on the climate system and improve projections of their future consequences.

5. Conclusions

The spatial structure of volcanic forcing plays a crucial role in determining the cli-mate response to volcanic eruptions. In this study, we assess the impacts of three types of volcanic events (TR, NH, and SH events) since the 1850s, each exhibiting distinct aerosol distributions and radiative forcing patterns. Using simulations from state-of-the-art CMIP6 global climate models, we investigate the climatic responses to three types of volcanic events focusing on radiative forcing, surface air temperature, precipitation, and ENSO-like variability. Our results show the distinct impacts of eruption on global and regional climate, driven by differences in aerosol distribution, hemispheric forcing asymmetry, and ocean–atmosphere interactions.

We show that TR eruptions induce largely symmetric radiative forcing and surface cooling across hemispheres, whereas NH and SH eruptions generate pronounced hemispheric asymmetries in both TOA radiative fluxes and surface air temperature responses. This asymmetric forcing leads to differential cooling between hemispheres and strongly influences atmospheric circulation and precipitation patterns. In particular, NH and SH eruptions drive shifts of the ITCZ away from the forced hemisphere, resulting in distinct zonal-mean precipitation anomalies.

Volcanic eruptions also trigger contrasting ENSO-like responses, depending on eruption location. TR and NH eruptions tend to favor El Niño–like warming in the tropical Pacific, while SH eruptions are more likely to induce La Niña–like conditions. These differences highlight the sensitivity of coupled ocean–atmosphere feedback to the meridional distribution of volcanic aerosol forcing.

Comparisons with DCPP experiments further confirm that the post-eruption cooling and circulation responses identified here are primarily driven by volcanic forcing rather than internal climate variability. Overall, our results underscore the importance of accounting for volcanic forcing asymmetry when interpreting past volcanic impacts and assessing their role in climate variability.

These findings provide a mechanism for understanding how eruption shapes climate feedback and underscore the necessity of accounting for volcanic forcing structure in interpreting historical climate variability. Future research should refine the mechanisms underlying ENSO-like responses, particularly the role of ocean dynamics and feedback processes, and explore interactions between volcanic forcing, greenhouse gas forcing, and internal variability to improve predictions of future volcanic impacts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.Z. and S.C.; methodology, Q.Z.; software, Q.Z.; validation, Q.Z. and S.C.; formal analysis, Q.Z. and S.C.; investigation, Q.Z. and S.C.; resources, S.C.; data curation, Q.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.Z.; writing—review and editing, Q.Z. and S.C.; visualization, Q.Z.; supervision, S.C.; project administration, S.C.; funding acquisition, S.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by research grants from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2020YFA0714103) and the Department of Emergency Management of Jilin Province (JLSZC202002826-1).

Data Availability Statement

The climate model data used in this study are openly available from the Earth System Grid Federation (ESGF) at the following URL: https://esgf-node.llnl.gov/search/cmip6/ (accessed on 25 December 2025).

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the World Climate Research Programme (WCRP), which, through its Working Group on Coupled Modelling, coordinated and promoted CMIP6. We thank the climate modeling groups for producing and making available their model output, the Earth System Grid Federation (ESGF) for archiving the data and providing access, and the multiple funding agencies who support CMIP6 and ESGF.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CMIP6 | Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 |

| DCPP | Decadal Climate Prediction Project |

| DCPP-A | Decadal Climate Prediction Project Component A |

| DCPP-C | Decadal Climate Prediction Project Component C |

| ITCZ | Intertropical convergence zone |

| ENSO | El Niño–Southern Oscillation |

| SAT | Surface Air Temperature |

| SST | Sea Surface Temperature |

| TR | Tropical |

| NH | Northern Hemisphere |

| SH | Southern Hemisphere |

References

- Trenberth, K.E.; Dai, A. Effects of Mount Pinatubo Volcanic Eruption on the Hydrological Cycle as an Analog of Geoengineering. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2007, 34, L15702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iles, C.E.; Hegerl, G.C.; Schurer, A.P.; Zhang, X.B. The Effect of Volcanic Eruptions on Global Precipitation. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2013, 118, 8770–8786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, W.M.; Zhou, T.J.; Jungclaus, J.H. Effects of Large Volcanic Eruptions on Global Summer Climate and East Asian Monsoon Changes during the Last Millennium: Analysis of MPI-ESM Simulations. J. Clim. 2014, 27, 7394–7409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambri, B.; Robock, A. Winter Warming and Summer Monsoon Reduction after Volcanic Eruptions in Coupled Model Intercomparison Project 5 (CMIP5) Simulations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2016, 43, 10920–10928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinsted, A.; Moore, J.C.; Jevrejeva, S. Observational Evidence for Volcanic Impact on Sea Level and the Global Water Cycle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 19730–19734. [Google Scholar]

- Mass, C.F.; Portman, D.A. Major Volcanic Eruptions and Climate: A Critical Evaluation. J. Clim. 1989, 2, 566–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, R.; Zeng, N. Seasonally Modulated Tropical Drought Induced by Volcanic Aerosol. J. Clim. 2011, 24, 2045–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadnavis, S.; Müller, R.; Chakraborty, T.; Sabin, T.P.; Laakso, A.; Rap, A.; Griessbach, S.; Vernier, J.-P.; Tilmes, S. The Role of Tropical Volcanic Eruptions in Exacerbating Indian Droughts. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 2714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogar, M.M.; Hermanson, L.; Scaife, A.A.; Visioni, D.; Zhao, M.; Hoteit, I.; Graf, H.-F.; Dogar, M.A.; Almazroui, M.; Fujiwara, M. A Review of El Niño Southern Oscillation Linkage to Strong Volcanic Eruptions and Post-Volcanic Winter Warming. Earth Syst. Environ. 2023, 7, 15–42. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson, S.; Fasullo, J.T.; Otto-Bliesner, B.L.; Tomas, R.A.; Gao, C.C. Role of Eruption Season in Reconciling Model and Proxy Responses to Tropical Volcanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 1822–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Li, J.B.; Wang, B.; Liu, J.; Li, T.; Huang, G.; Wang, Z.Y. Divergent El Niño Responses to Volcanic Eruptions at Different Latitudes over the Past Millennium. Clim. Dyn. 2018, 50, 3799–3812. [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, M.; Man, W.; Zhou, T.; Guo, Z. Different Impacts of Northern, Tropical, and Southern Volcanic Eruptions on the Tropical Pacific SST in the Last Millennium. J. Clim. 2018, 31, 6729–6744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erez, M.; Adam, O. Energetic Constraints on the Time-Dependent Response of the ITCZ to Volcanic Eruptions. J. Clim. 2021, 34, 9989–10006. [Google Scholar]

- Toohey, M.; Krüger, K.; Schmidt, H.; Timmreck, C.; Sigl, M.; Stoffel, M.; Wilson, R. Disproportionately Strong Climate Forcing from Extratropical Explosive Volcanic Eruptions. Nat. Geosci. 2019, 12, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Vecchi, G.A.; Fueglistaler, S.; Horowitz, L.W.; Luet, D.J.; Muñoz, Á.G.; Paynter, D.; Underwood, S. Climate Impacts from Large Volcanic Eruptions in a High-Resolution Climate Model: The Importance of Forcing Structure. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2019, 46, 7690–7699. [Google Scholar]

- Zanchettin, D.; Bothe, O.; Timmreck, C.; Bader, J.; Beitsch, A.; Graf, H.-F.; Notz, D.; Jungclaus, J.H. Inter-Hemispheric Asymmetry in the Sea-Ice Response to Volcanic Forcing Simulated by MPI-ESM (COSMOS-Mill). Earth Syst. Dyn. 2014, 5, 223–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauling, A.G.; Bushuk, M.; Bitz, C.M. Robust Inter-Hemispheric Asymmetry in the Response to Symmetric Volcanic Forcing in Model Large Ensembles. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2021, 48, e2021GL092558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clement, A.C.; Seager, R.; Cane, M.A.; Zebiak, S.E. An Ocean Dynamical Thermostat. J. Clim. 1996, 9, 2190–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirono, M. On the Trigger of El Niño Southern Oscillation by the Forcing of Early El Chichón Volcanic Aerosols. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 1988, 93, 5365–5384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjerknes, J. Atmospheric Teleconnections from the Equatorial Pacific. Mon. Weather Rev. 1969, 97, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Predybaylo, E.; Stenchikov, G.L.; Wittenberg, A.T.; Zeng, F. Impacts of a Pinatubo-Size Volcanic Eruption on ENSO. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2017, 122, 925–947. [Google Scholar]

- Maher, N.; McGregor, S.; England, M.H.; Sen Gupta, A. Effects of Volcanism on Tropical Variability. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2015, 42, 6024–6033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodri, M.; Izumo, T.; Vialard, J.; Janicot, S.; Cassou, C.; Lengaigne, M.; Mignot, J.; Gastineau, G.; Guilyardi, E.; Lebas, N.; et al. Tropical Explosive Volcanic Eruptions Can Trigger El Niño by Cooling Tropical Africa. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1234. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stenchikov, G.; Hamilton, K.; Stouffer, R.J.; Robock, A.; Ramaswamy, V.; Santer, B.; Graf, H. Arctic Oscillation Response to Volcanic Eruptions in the IPCC AR4 Climate Models. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2006, 111, D07107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deser, C.; Lehner, F.; Rodgers, K.B.; Ault, T.; Delworth, T.L.; DiNezio, P.N.; Fiore, A.; Frankignoul, C.; Fyfe, J.C.; Horton, D.E.; et al. Insights from Earth System Model Initial-Condition Large Ensembles and Future Prospects. Nat. Clim. Change 2020, 10, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyring, V.; Bony, S.; Meehl, G.A.; Senior, C.A.; Stevens, B.; Stouffer, R.J.; Taylor, K.E. Overview of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) Experimental Design and Organization. Geosci. Model Dev. 2016, 9, 1937–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanchettin, D.; Khodri, M.; Timmreck, C.; Toohey, M.; Schmidt, A.; Gerber, E.P.; Hegerl, G.; Robock, A.; Pausata, F.S.R.; Ball, W.T.; et al. The Model Intercomparison Project on the Climatic Response to Volcanic Forcing (VolMIP): Experimental Design and Forcing Input Data for CMIP6. Geosci. Model Dev. 2016, 9, 2701–2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pausata, F.S.R.; Chafik, L.; Caballero, R.; Battisti, D.S. Impacts of High-Latitude Volcanic Eruptions on ENSO and AMOC. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 13784–13788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boer, G.J.; Smith, D.M.; Cassou, C.; Doblas-Reyes, F.; Danabasoglu, G.; Kirtman, B.; Kushnir, Y.; Kimoto, M.; Meehl, G.A.; Msadek, R.; et al. The Decadal Climate Prediction Project (DCPP) Contribution to CMIP6. Geosci. Model Dev. 2016, 9, 3751–3777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morice, C.P.; Kennedy, J.J.; Rayner, N.A.; Winn, J.P.; Hogan, E.; Killick, R.E.; Dunn, R.J.H.; Osborn, T.J.; Jones, P.D.; Simpson, I.R. An Updated Assessment of Near-Surface Temperature Change from 1850: The HadCRUT5 Dataset. J. Geophys. Res. 2021, 126, e2019JD032361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, U.; Becker, A.; Finger, P.; Meyer-Christoffer, A.; Ziese, M.; Rudolf, B. GPCC’s New Land Surface Precipitation Climatology Based on Quality-Controlled In Situ Data and Its Role in Quantifying the Global Water Cycle. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2014, 115, 15–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomason, L.W.; Ernest, N.; Millán, L.; Rieger, L.; Bourassa, A.; Vernier, J.-P.; Manney, G.; Luo, B.; Arfeuille, F.; Peter, T. A Global Space-Based Stratospheric Aerosol Climatology: 1979–2016. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2018, 10, 469–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, M.; Hansen, J.E.; McCormick, M.P.; Pollack, J.B. Stratospheric Aerosol Optical Depths, 1850–1990. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 1993, 98, 22987–22994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neely, R.R., III; Schmidt, A. VolcanEESM: Global Volcanic Sulphur Dioxide (SO2) Emissions Database from 1850 to Present; Centre for Environmental Data Analysis: Chilton, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilbao, R.; Wild, S.; Ortega, P.; Acosta-Navarro, J.; Arsouze, T.; Bretonnière, P.-A.; Caron, L.-P.; Castrillo, M.; Cruz-García, R.; Cvijanovic, I.; et al. Assessment of a Full-Field Initialized Decadal Climate Prediction System with the CMIP6 Version of EC-Earth. Earth Syst. Dyn. 2021, 12, 173–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeager, S.G.; Danabasoglu, G.; Rosenbloom, N.A.; Strand, W.; Bates, S.C.; Meehl, G.A.; Karspeck, A.R.; Lindsay, K.; Long, M.C.; Teng, H.; et al. Predicting Near-Term Changes in the Earth System: A Large Ensemble of Initialized Decadal Prediction Simulations Using the Community Earth System Model. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2018, 99, 1867–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolì, D.; Bellucci, A.; Ruggieri, P.; Athanasiadis, P.J.; Materia, S.; Peano, D.; Fedele, G.; Hénin, R.; Gualdi, S. The Euro-Mediterranean Center on Climate Change (CMCC) Decadal Prediction System. Geosci. Model Dev. 2023, 16, 179–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sospedra-Alfonso, R.; Merryfield, W.J.; Boer, G.J.; Kharin, V.V.; Lee, W.-S.; Seiler, C.; Christian, J.R. Decadal Climate Predictions with the Canadian Earth System Model Version 5 (CanESM5). Geosci. Model Dev. 2021, 14, 6863–6891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.D.; Copsey, D.; Blockley, E.W.; Bodas-Salcedo, A.; Calvert, D.; Comer, R.; Davis, P.; Graham, T.; Hewitt, H.T.; Hill, R.; et al. The Met Office Global Coupled Model 3.0 and 3.1 (GC3.0 and GC3.1) Configurations. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 2018, 10, 357–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Chai, J.; Wang, B.; Liu, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Z.Y. Global Monsoon Precipitation Responses to Large Volcanic Eruptions. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 24331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, S.; Otto-Bliesner, B.; Fasullo, J.; Brady, E. “El Niño Like” Hydroclimate Responses to Last Millennium Volcanic Eruptions. J. Clim. 2016, 29, 2907–2921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigl, M.; Winstrup, M.; McConnell, J.R.; Welten, K.C.; Plunkett, G.; Ludlow, F.; Büntgen, U.; Caffee, M.W.; Chellman, N.; Dahl-Jensen, D.; et al. Timing and Climate Forcing of Volcanic Eruptions for the Past 2500 Years. Nature 2015, 523, 543–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, C.C.; Robock, A.; Ammann, C. Volcanic Forcing of Climate over the Past 1500 Years: An Improved Ice Core-Based Index for Climate Models. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2008, 113, D23101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haurwitz, M.W.; Brier, G.W. A Critique of the Superposed Epoch Analysis Method: Its Application to Solar Weather Relations. Mon. Weather Rev. 1981, 109, 2074–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, M.P.; Cook, E.R.; Cook, B.I.; Anchukaitis, K.J.; D’Arrigo, R.D.; Krusic, P.J.; LeGrande, A.N. A Double Bootstrap Approach to Superposed Epoch Analysis to Evaluate Response Uncertainty. Dendrochronologia 2019, 55, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.J.; Gao, C.C. European Hydroclimate Response to Volcanic Eruptions over the Past Nine Centuries. Int. J. Climatol. 2017, 37, 4146–4157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, L.; Smerdon, J.E.; Pretis, F.; Hartl-Meier, C.; Esper, J. A New Archive of Large Volcanic Events over the Past Millennium Derived from Reconstructed Summer Temperatures. Environ. Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 094002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trouet, V.; Babst, F.; Meko, M. Recent Enhanced High-Summer North Atlantic Jet Variability Emerges from Three-Century Context. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esper, J.; Schneider, L.; Krusic, P.J.; Luterbacher, J.; Büntgen, U.; Timonen, M.; Sirocko, F.; Zorita, E. European Summer Temperature Response to Annually Dated Volcanic Eruptions over the Past Nine Centuries. Bull. Volcanol. 2013, 75, 736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.B.; Mann, M.E.; Ammann, C.M. Proxy Evidence for an El Niño-like Response to Volcanic Forcing. Nature 2003, 426, 274–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roychowdhury, R.; DeConto, R. Interhemispheric Effect of Global Geography on Earth’s Climate Response to Orbital Forcing. Clim. Past 2019, 15, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pausata, F.S.R.; Zanchettin, D.; Karamperidou, C.; Caballero, R.; Battisti, D.S. ITCZ Shift and Extratropical Teleconnections Drive ENSO Response to Volcanic Eruptions. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaaz5006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, D.P.; Ammann, C.M.; Otto-Bliesner, B.L.; Kaufman, D.S. Climate Response to Large, High-Latitude and Low-Latitude Volcanic Eruptions in the Community Climate System Model. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2009, 114, D19101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colose, C.M.; LeGrande, A.N.; Vuille, M. Hemispherically Asymmetric Volcanic Forcing of Tropical Hydroclimate During the Last Millennium. Earth Syst. Dyn. 2016, 7, 681–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Held, I.M.; Soden, B.J. Robust Responses of the Hydrological Cycle to Global Warming. J. Clim. 2006, 19, 5686–5699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGregor, S.; Timmermann, A. The Effect of Explosive Tropical Volcanism on ENSO. J. Clim. 2011, 24, 2178–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.B.; Xie, S.P.; Cook, E.R.; Morales, M.S.; Christie, D.A.; Johnson, N.C.; Chen, F.; D’Arrigo, R.; Fowler, A.M.; Gou, X.; et al. El Niño Modulations over the Past Seven Centuries. Nat. Clim. Change 2013, 3, 822–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.