Abstract

Intensity–Duration–Frequency (IDF) curves are essential tools in the design of stormwater management systems and are often used over long periods without frequent updates. However, the continuous collection of rainfall data and the expansion of monitoring networks call for regular revisions of these curves. In Romania, current engineering and hydrological practices still rely on regionalized IDF graphs developed in 1973. Given the ongoing effects of climate change—particularly the increased frequency and, more significantly, intensity of extreme rainfall events—updating these curves has become critical. Incorporating recent observations is essential not only for methodological accuracy but also to support climate-resilient infrastructure design. This study employs updated IDF curves provided by the National Administration of Meteorology, based on 30 years of precipitation records from 68 meteorological stations across Romania. The main objective is to evaluate alternative regionalization approaches—including clustering methods, geographic proximity analysis, and hourly precipitation isolines for a 1:10 Annual Exceedance Frequency—to develop a new regionalization model and the corresponding nationwide IDF relationships. A comparative analysis using raster-based regional rainfall datasets from both the 1973 and 2025 regionalizations revealed significant changes in precipitation patterns. Short-duration rainfall events (5, 10, and 30 min) have increased in intensity across most regions, while long-duration events (3, 6, 12, and 24 h) have generally decreased in magnitude in several areas. These findings highlight a growing trend toward more intense short-term convective storms, underlining the urgent need for improved flash flood prevention and urban stormwater management strategies.

1. Introduction

1.1. Theoretical Review of IDF Curves

Intensity–Duration–Frequency (IDF) curves quantitatively describe the average intensity of annual maximum rainfall as a function of rainfall duration and frequency (or return period) [1,2]. Koutsoyiannis et al. [3] emphasized that “frequency” should be interpreted as the Annual Frequency of Exceedance (AFE). Mathematically, the IDF relationship can be expressed as

where d is the rainfall duration, and is the average number of years in which a rainfall event of duration is equaled or exceeded. The term denotes the AFE—that is, the frequency that a certain rainfall intensity is equaled or exceeded in any given year.

IDF curves are empirical relationships derived from the statistical analysis of rainfall data for various durations. For each duration , the series of maximum intensities recorded over N ≥ 30 years is analyzed. The first empirical IDF relationship was proposed by Talbot (1881) (Sosrodarsono and Takeda, 1983, cited in [4]), followed by improvements by Sherman (1905), Bernard (1932), Wenzel (1982), Kimijima, and Koutsoyiannis (1998) [1,3,5].

Two primary statistical approaches are used in the analysis of hydrological extremes (e.g., peak flow, rainfall, temperature):

- Annual Maxima Series (AMS), also known as Block Maxima (BM);

- Partial Duration Series (PDS), also known as the Peak Over Threshold (POT) method [1,3,6,7,8,9].

The AMS/BM method was first applied in hydrology [10,11], while the PDS/POT method has evolved over the past 50 years, with a comprehensive synthesis by Cunnane [12,13,14,15]. In the POT method, successive values must be statistically independent, and the threshold must be set so that the resulting series contains N events [3,16]. If the threshold leads to more or fewer than N events, the probabilities must be adjusted to annual exceedance probabilities [17]. A threshold set too low may lead to serial correlation. Several studies have compared BM and POT methods for both streamflow [18,19,20,21,22] and rainfall intensity [9,16,23,24].

Various probability distributions have been used to model rainfall extremes, including the Extreme Value Type I (Gumbel) [1,8], Pearson Type III [5], and Generalized Pareto (GP) distributions [9]. Others include the Generalized Extreme Value (GEV) distribution (which encompasses EV Types I–III), two-parameter Gamma, Log-Pearson III, lognormal, exponential, and three-parameter Pareto distributions [3]. Among these, the Gumbel distribution is widely used due to its simplicity—it requires only two parameters (mean and standard deviation). In contrast, three-parameter models, which require skewness estimation, introduce greater uncertainty [25]. According to Ben-Zvi [9], the Gumbel and lognormal distributions best fit AMS data, while the GP distribution performs better for PDS datasets. However, the GP distribution is not suitable for AMS data. The RainIDF software [26] automates the derivation of IDF curves using the GEV distribution for AMS and the GPA (Generalized Pareto) distribution for PDS.

In Romania, as in many countries, maximum rainfall analysis has traditionally relied on the Gumbel distribution applied to AMS, often without considering the PDS approach. Koutsoyiannis [16,24,25], however, showed that Gumbel tends to underestimate extreme rainfall for long datasets, though it is acceptable for shorter periods. He suggested that the Extreme Value Type II (Fréchet) distribution may offer a more appropriate model.

IDF curves are first calculated at the station level using the least squares method to estimate local parameters. However, At-Site Frequency Analysis (AFA) can produce biased results when the length of local records is short. To address this, Regional Frequency Analysis (RFA), also called regionalization, divides the study area into homogeneous regions [27,28]. RFA compensates for short local records by aggregating data from multiple stations in a homogeneous region, thereby increasing sample size and improving quantile estimates [28]. Ideally, all rainfall records used in RFA should cover the same time period. RFA generally outperforms AFA for low-frequency events (e.g., 1:30, 1:50, 1:100), while AFA may be more reliable for high-frequency events (e.g., 1:2, 1:3) when sufficient local data are available [28]. Despite its benefits, regionalization based on homogeneous zones has limitations, such as discontinuities at region boundaries, neglect of local topography and climate influences, and potential over- or underestimation of quantiles—even at the site level—due to regional averaging [29]. A more flexible alternative is boundaryless regionalization, which uses geostatistical interpolation of at-site parameters [29,30].

Different methods have been used for regionalization. Based on local IDF relationships, regional maps of rainfall intensities or depths for various durations and frequencies have been created [1,10]. Other researchers have derived isolines for IDF parameters at each AFE. For example, Nhat et al. [5] developed contour maps of the three Kimijima parameters for Vietnam. Using these maps, IDF curves can be derived for any location and frequency. Another common method involves dividing the country into homogeneous zones, assigning a specific set of IDF curves to each.

1.2. Practical Applications of IDF Curves

IDF curves are indispensable tools in hydrological design and planning. They are used for

- Defining design storms to estimate design or verification flows for the rehabilitation and expansion of sewerage systems or the development of new drainage networks;

- Establishing flood risk management measures, particularly in urban drainage basins and small catchments;

- Providing meteorological input for spatial planning decisions involving land-use changes.

IDF relationships developed at meteorological stations can be extrapolated to adjacent areas considered meteorologically homogeneous, typically within approximately 50 km2. Rainfall durations used in IDF analyses generally range from 5 to 1440 min. Temporal resolution is finer (every 5 min) for durations up to 120 min and becomes coarser for longer durations (e.g., 140, 160, 180, 240, 300, 360, 720, and 1440 min). IDF curves are typically produced for frequencies of 1:2, 1:3, 1:5, 1:10, 1:20, 1:50, and 1:100 years. In cases where high-resolution rainfall data are unavailable, more commonly available daily rainfall records can be used to estimate IDF curves for short-duration events by applying scaling relationships [3,31].

1.3. Frequency Standards

In Romania, sewerage systems have traditionally been designed using frequencies ranging from 1:2 for villages or small towns to 1:3 for large cities. These design criteria are generally aligned with those adopted in many European countries, although certain critical infrastructure components may be designed for higher frequencies, up to 1:50 [24]. The European standard EN 752-2 [32] recommends design rainfall frequencies for gravity drainage systems located outside buildings in the range of 1:1 to 1:10 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Design frequencies recommended in the EU standard EN 752-2.

Urban flooding generally occurs less frequently than the design storm frequency because sewer systems are designed to operate without surcharge. Under pressurized flow conditions, their discharge capacity increases significantly, meaning that street flooding tends to occur only during more extreme events [33,34].

The new Romanian regulations [35] specify design frequencies of 1:5 for settlements with fewer than 100,000 inhabitants and 1:10 for larger cities.

1.4. Objective and Organization of the Paper

The main objective of this study is to evaluate various approaches for the regionalization of IDF curves across the entire territory of Romania, including

(a) Clustering techniques (e.g., k-means, DBSCAN, and hierarchical clustering);

(b) Isolines of statistical parameters derived from annual maximum daily rainfall;

(c) Similarity analysis among IDF curves from different meteorological stations; and

(d) Isolines of 1 h rainfall depth corresponding to a 1:10 Annual Frequency of Exceedance (AFE).

The structure of the paper is as follows:

- Section 1 introduces the background, theoretical framework, and objectives of the study.

- Section 2 describes the study area and the methodological framework.

- Section 3 presents the results obtained from the applied approaches and their comparative evaluation.

- Section 4 discusses the coefficients a, b, and c, which characterize each region and vary depending on the Annual Frequency of Exceedance (AFE). This section also addresses the main constraints, analyzes variability within homogeneous zones, the uncertainty of representative IDF curves, and the potential influence of climate change.

- Section 5 summarizes the main conclusions and outlines directions for future research.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

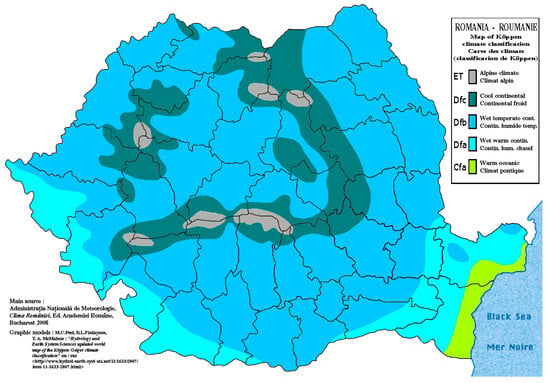

Romania covers an area of 238,397 km2, located in Southeastern Europe and bordered by Ukraine, Hungary, Serbia, Bulgaria, the Republic of Moldova, and the Black Sea. The country lies between 43° and 49° N latitude and 20° and 30° E longitude. The Carpathian Mountains dominate central Romania, surrounded by the Moldavian and Transylvanian Plateaus, the Pannonian Plain, and the Wallachian Plain [36]. Romania has a continental climate, with notable regional variations: Mediterranean influences are present in the western regions (especially Banat), a more pronounced continental climate dominates the eastern regions, and maritime influences from the Black Sea affect the Dobrogea region (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Köppen climate classification map of Romania [36].

Significant rainfall over short time intervals is closely linked to the development of cyclones, particularly those originating in the Mediterranean region. The formation and movement of such cyclones are often strongly influenced by orographic conditions along their trajectories [37]. High-intensity rainfall events lasting between 8 and 12 h or extending up to 24–72 h can cause widespread flooding across basin areas ranging from 3000 to 25,000 km2. Within these basins, localized cores of extremely intense rainfall—lasting 2–3 h or less—may develop, often triggering flash floods.

2.2. Research Framework

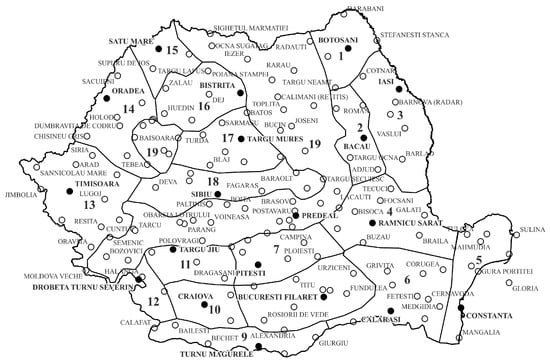

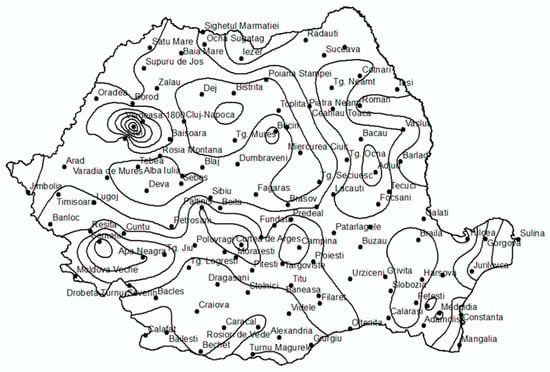

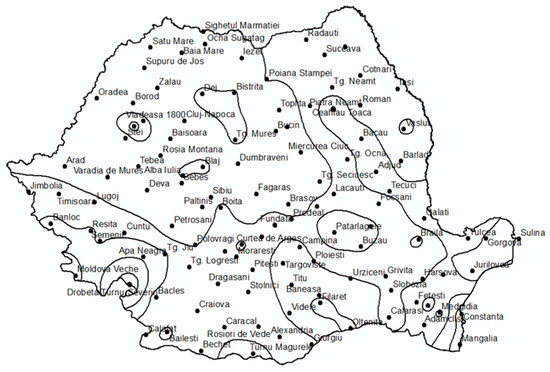

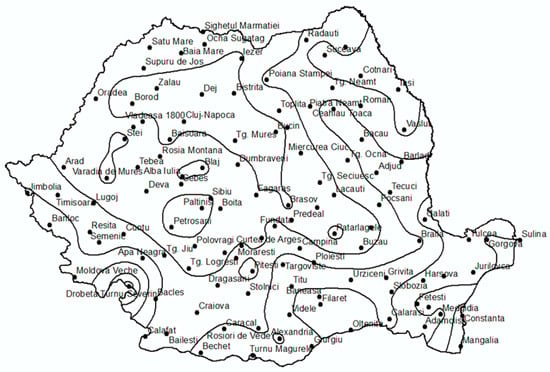

The regionalization currently applied in Romania, as established by Romanian Standard STAS 9470:1973 [38], is primarily based on geographical and geomorphological criteria and consists of nineteen polygons (Figure 2). The black dots on the map indicate the representative meteorological stations for each polygon, while the combined black and white dots represent all stations that existed at that time. Each polygon defines the area of influence of its representative station, meaning that the corresponding IDF curve is assumed to be valid throughout the entire polygon.

Figure 2.

IDF regionalization applied since 1973. Legend: black dots = representative stations for each polygon; white dots = other meteorological stations.

The original IDF curves published in STAS 9470:1973 [38] were only available in printed graphical form, with no accompanying numerical datasets. For this study, the historical curves were first obtained from a scanned version of the original normative document and then digitized using dedicated software. The digitization process followed a rigorous protocol: the axes were georeferenced, each curve was manually traced, and data points were extracted at sufficiently high resolution to minimize reading errors. Occasional ambiguities caused by line thickness or curve overlap were resolved through repeated extractions and cross-checks to ensure internal consistency. Although minor uncertainties are inherent in any reconstruction of historical graphical data, the resulting digitized values closely replicate the original curves and are suitable for comparative analysis with the newly derived IDF relationships.

Meteorological data have been continuously collected since 1973, with new monitoring stations commissioned over time. This expansion necessitates updating the historical IDF curves to support infrastructure adaptation to evolving climate conditions. Climate change plays a critical role, significantly altering both the frequency and intensity of extreme rainfall events—further justifying the need for such updates. High Hurst index values indicate, with strong probability, an upward trend in the frequency of extreme rainfall events [39]. To assess the effects of climate change, IDF curves based on rainfall data from the past 30 years were analyzed and compared with those developed in 1973.

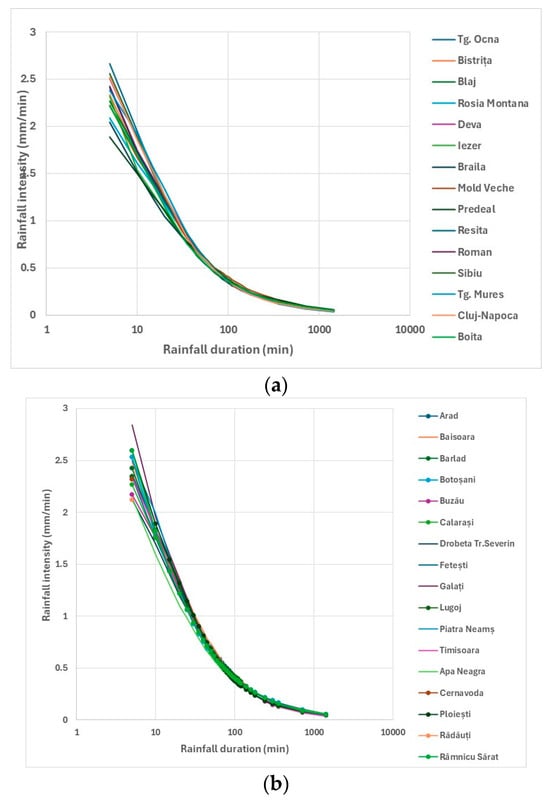

Out of 102 meteorological stations with continuous records, 68 were selected based on their relevance and proximity to settlements with populations exceeding 2000 inhabitants. The 2025 IDF curves were provided—both graphically and numerically—by the Romanian National Meteorological Administration (ANM). As with the 1973 curves, these were converted into analytical expressions using Sherman’s equation.

Appropriate regionalization is a prerequisite for conducting Regional Frequency Analysis (RFA) of rainfall. Several approaches were tested to identify the most consistent and robust regionalization, as outlined below:

- First approach: Annual maximum daily rainfall values were analyzed, and the stations were grouped according to their coefficient of variation, applying different clustering methods: k-means, DBSCAN, and Hierarchical Clustering.

- Second approach: For the same annual maximum daily rainfall values, contour maps were generated for each statistical parameter (mean, standard deviation, coefficient of variation) and analyzed for their spatial plausibility.

- Third approach: Pairwise similarity analysis was performed between stations, where similarity was accepted when both the correlation coefficient and the Nash–Sutcliffe Efficiency (NSE) exceeded 0.99.

- Fourth approach: Regionalization based on the 1 h rainfall depth corresponding to a 1:10 Annual Frequency of Exceedance (AFE) for each station.

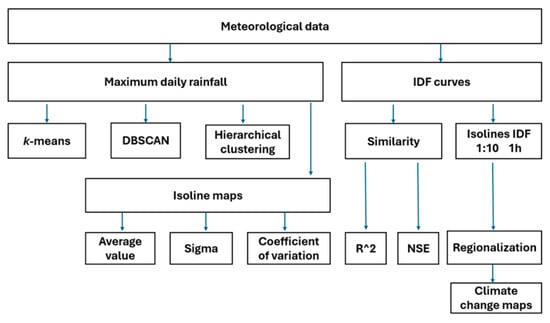

To further assess the impact of climate change, the percentage differences between the rasters corresponding to the 2025 regionalization (based on the 1 h maximum depth) and those from 1973 were computed. A flowchart illustrating the adopted procedures is presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Flowchart of the approach adopted.

2.2.1. Clustering—Overview

In hydrology and meteorology, identifying homogeneous regions is essential for frequency analysis, water resource management, and climate risk assessment. Cluster analysis is a powerful tool for this purpose, as it classifies data points (e.g., meteorological stations) into groups (clusters) with similar characteristics—thus revealing spatial patterns and reducing data complexity [27].

In this study, the coefficient of variation () of annual maximum daily rainfall was selected as the primary attribute for clustering. is a normalized measure of dispersion, defined as the ratio of the standard deviation to the mean, and is particularly well suited for comparing the relative variability of extreme rainfall across stations with differing mean precipitation levels. Clustering based on aims to group stations that exhibit similar statistical behavior in terms of the interannual variability of extremes—an essential step in supporting Regional Frequency Analysis.

The choice of the coefficient of variation as the clustering variable was motivated by the need to ensure methodological consistency across the national dataset. Certain geographical and climatic variables—such as elevation, slope, aspect, or orographic exposure—were either unavailable at uniform resolution for all stations or derived from heterogeneous data sources. To avoid introducing additional uncertainty or bias stemming from mixed-quality auxiliary variables, we selected a descriptor based solely on precipitation: directly measurable, station-specific, and fully comparable across Romania.

Moreover, relying on a single, robust statistical indicator allowed for a clearer interpretation of the clustering results and minimized the risk of overfitting or generating clusters influenced by secondary correlations rather than by the intrinsic variability of extreme precipitation. Although multivariate clustering could potentially refine regional boundaries, such an approach requires a dedicated assessment of interdependencies among multiple features—an extension that falls beyond the scope of this study but represents a valuable direction for future research.

As shown above, homogeneous regions can be identified through cluster analysis, which classifies data into similar overlapping or non-overlapping groups [27].

Several cluster validity indices—such as the Partition Coefficient, Partition Entropy, Extended Xie–Beni Index, Fukuyama–Sugeno Index, and Kwon Index—can be used to evaluate the quality of partitions generated by different algorithms [27]. In this study, we employed the following clustering algorithms:

- k-means

This centroid-based algorithm requires the predefinition of the number of clusters (k). It partitions meteorological stations by minimizing the within-cluster variance, using Euclidean distance as the similarity metric. For two stations, and , characterized by their geographical coordinates (, ) and coefficient of variation , the distance is calculated as follows:

where are the geographical coordinates, and is the coefficient of variation for station .

In this study, 68 stations were grouped using the coefficient of variation in annual maximum daily rainfall as the primary clustering attribute.

DBSCAN (Density-Based Spatial Clustering of Applications with Noise)Unlike k-means, DBSCAN does not require a predefined number of clusters. It identifies dense regions of points (clusters) and labels points in low-density areas as outliers. The algorithm’s performance is sensitive to two key parameters: the maximum distance between neighboring points (eps) and the minimum number of points required to form a cluster (minPts).

Hierarchical Clustering: This algorithm constructs a nested tree of clusters (a dendrogram) based on pairwise distances, without requiring the number of clusters to be specified in advance. The final partition is obtained by cutting the dendrogram at a selected level.

2.2.2. Isolines of Statistical Parameters of the Annual Series of Maximum Daily Rainfall

These maps present isolines of key statistical parameters—mean, standard deviation, and coefficient of variation—calculated from the annual series of maximum daily rainfall at each station.

Annual maximum daily rainfall series have been widely used in previous studies. For example, Koutsoyiannis [25] and Koutsoyiannis and Baloutsos [40] analyzed such data for Athens, Greece, over the period 1860–1995. Kuo et al. [41] investigated trends in annual maximum rainfall during extreme events in southern Taiwan, considering both 24 h and 1 h durations. Similarly, Deidda et al. [29] and Mínguez and Herrera [30] examined 24 h rainfall records in studies on extreme precipitation in Sardinia and the Basque Country, respectively. Given the continued relevance of daily-resolution rainfall maxima in hydrological analyses, isolines of statistical parameters for 24 h precipitation were generated as part of this study.

2.2.3. Similarities Between Meteorological Stations—Overview

The similarity between IDF curves at any two stations (i and j) was assessed using the Coefficient of Determination () and the Nash–Sutcliffe Efficiency () metric.

These indicators offer a more reliable and comprehensive evaluation of similarity compared to traditional measures [42].

- The Coefficient of Determination

- The Nash–Sutcliffe Efficiency () coefficient is computed as one minus the ratio of the error variance between time series i and j to the variance of series j:

2.2.4. Isolines of the 1 h Accumulated Rainfall Depth Corresponding to a 1:10 AFE

All raster layers and isolines were generated using the Inverse Distance Weighting (IDW) method, ensuring that local variability was accurately represented based on proximity to observation points. This interpolation technique was chosen to maintain consistency across Annual Frequencies of Exceedance (AFEs) and to minimize deviations from observed values.

The isolines were produced using an appropriate discretization step, which resulted in the division of the territory into homogeneous zones. To characterize the region between two adjacent isolines, the IDF curve that provided conservative hydrological estimates was selected.

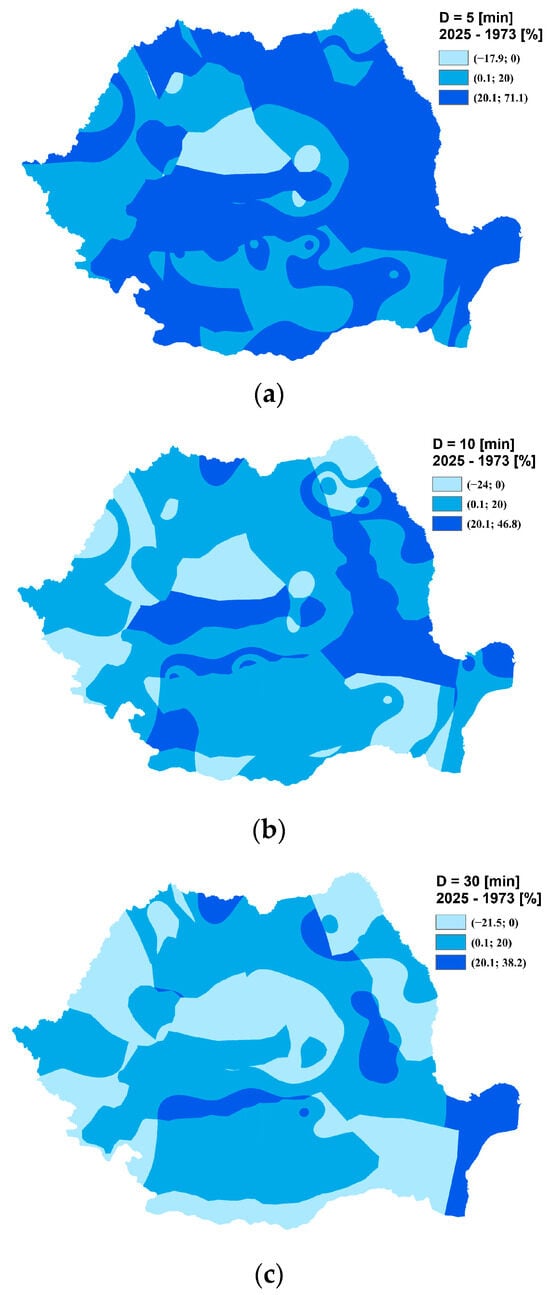

2.2.5. Investigating Climate Change

Using regionalized rainfall raster data for the years 1973 and 2025, percentage differences in rainfall intensity were computed for the following durations: 5, 10, 30, and 60 min, as well as 3, 6, 12, and 24 h. The resulting maps highlight changes in rainfall patterns between 1973 and 2025, offering a clear depiction of climatic shifts across multiple temporal scales.

2.2.6. Using the Sherman RELATION for IDF Curves

Rainfall intensity is inversely proportional to storm duration raised to a power, which acts as a scaling factor [3]. The most general form of the IDF relationship was proposed by Koutsoyiannis et al. [3]:

where I is the mean rainfall intensity corresponding to duration d, and all coefficients are non-negative. The numerator reflects the influence of rainfall frequency, while the denominator is a function of storm duration [3]. The shape of the IDF curve is primarily controlled by the denominator: the parameter defines the slope of the linear segment, while θ determines the curvature transition point [43].

All IDF relationships currently in use can be derived as special cases of Equation (5) by setting or [3]. To prevent intersection among IDF curves, the coefficients must satisfy the following conditions:

For , Equation (5) reduces to the Sherman equation:

where denotes the average rainfall intensity over a duration D, and , , and are non-negative coefficients.

The coefficients of Equations (6) and (7) are related as follows:

If the concentration time for a specific location falls between the tabulated durations and interpolation is required, the Sherman analytical expression can be used to approximate the corresponding IDF curve:

where

a, b, and c are parameters of the IDF curve for the chosen AFE; and

= is the rainfall duration, assumed equal to the time of concentration .

The parameter values for each AFE and each homogeneous zone were determined using the least squares method by minimizing the following objective function:

where represents the rainfall intensity corresponding to the analyzed AFEs for standard durations ranging from 5 to 1440 min, and a, b, and c are specific to each AFE and homogeneous zone.

3. Results

3.1. Clustering—Commented Results

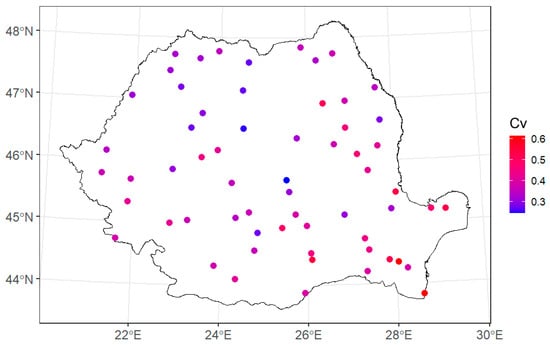

The spatial distribution of the 68 meteorological stations across Romania, color-coded by their coefficient of variation values (Figure 4), indicates a gradual spatial pattern but does not reveal clearly defined homogeneous zones.

Figure 4.

Spatial distribution of meteorological stations across Romania, color-coded by the coefficient of variation in annual maximum daily rainfall.

To objectively identify groups of stations with similar coefficient of variation values, clustering techniques were applied—effectively regionalizing the territory based on the relative variability of extreme daily rainfall. This regionalization serves several key purposes:

- It simplifies complex spatial data by aggregating stations into coherent units;

- It highlights regions with potentially different risk profiles related to rainfall extremes;

- It provides a spatial framework for validating the interpolation of climatic indices and supporting future Regional Frequency Analysis;

- It reveals underlying spatial structures in climate variability across Romania [40,41,42,44,45,46,47,48,49].

Clustering techniques in hydrology and meteorology are especially valuable for regionalizing precipitation and temperature models. These methods group stations with comparable climatic characteristics, reduce data complexity by aggregating information into coherent units, identify areas at higher risk of extreme weather events, and support regional interpolation by providing a framework for climatic and hydrological modeling. Thus, clustering serves not only as a classification tool but also as a means of revealing spatial structures and patterns of climate variability at both national and regional scales [44,45,46,50,51].

- k-means Clustering

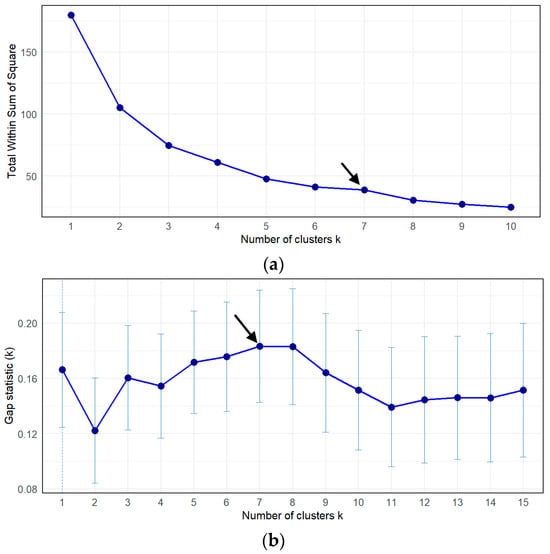

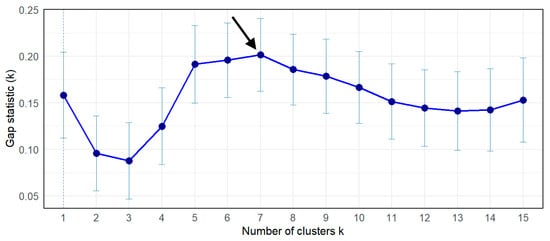

The optimal number of clusters (k) was determined using the Elbow method—based on the Within-Cluster Sum of Squares (WSS)—and the Gap Statistic (Figure 5a,b).

Figure 5.

Methods for determining the optimal number of clusters: (a) Elbow method (WSS); (b) Gap Statistic. Blue dots indicate the values of the Gap statistic computed for each tested number of clusters k.

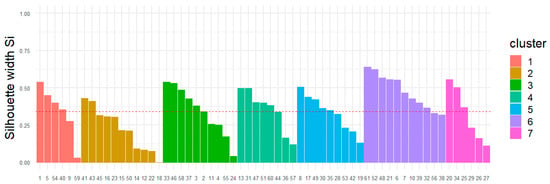

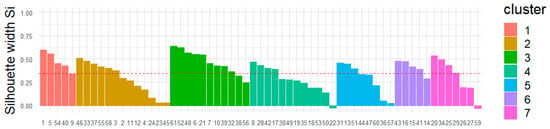

Both methods indicated k = 7 as the optimal number of clusters. The quality of this 7-cluster partition was further evaluated using the average Silhouette score (Figure 6)

Figure 6.

Silhouette plot for k-means clustering (k = 7).

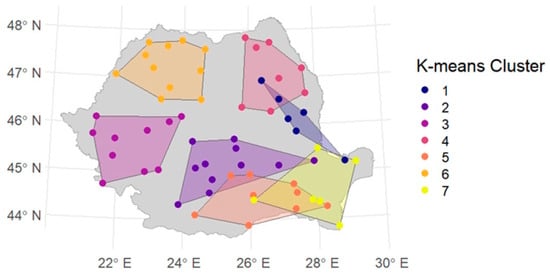

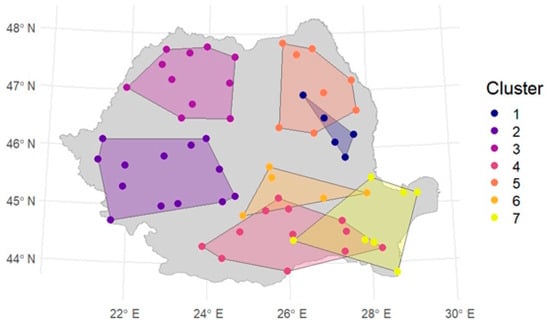

A Silhouette score of 0.342 was obtained, indicating a moderate clustering structure in which stations are reasonably assigned to their respective clusters. (For reference: values close to 1.0 indicate well-separated clusters; 0.5–0.7 denote good clustering; 0.3–0.5 suggest moderate clustering; and values below 0.3 imply poor clustering). The spatial distribution resulting from the k-means algorithm with k = 7 is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Results of k-means clustering (k = 7), with convex hulls and cluster assignments.

- DBSCAN Clustering

DBSCAN identified only four clusters, with an average Silhouette score of 0.17, indicating poor clustering quality. This suggests that DBSCAN—designed to detect dense, non-spherical clusters and isolate noise—is less suitable for this dataset, where stations are relatively uniformly distributed in space and exhibit a continuous gradient in the attribute.

- Hierarchical Clustering

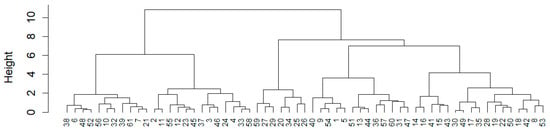

The dendrogram generated from hierarchical clustering using Ward’s method is presented in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Hierarchical clustering dendrogram (Ward’s method), based on and station coordinates.

Cutting the dendrogram to obtain k = 7 clusters—also supported by the Gap Statistic (Figure 9)—resulted in an average Silhouette score of 0.345 (Figure 10), indicating a performance comparable to that of k-means.

Figure 9.

Gap Statistic plot for determining the optimal number of clusters. Blue dots indicate the values of the Gap statistic computed for each tested number of clusters k.

Figure 10.

Silhouette plot for hierarchical clustering (k = 7).

The spatial grouping (Figure 11) shows strong consistency with the k-means result (Figure 7), confirming the robustness of the identified regional pattern.

Figure 11.

Hierarchical clustering results (k = 7), with convex hulls and station locations.

A comparison between Figure 7 and Figure 11 shows that k-means and hierarchical clustering yield very similar spatial distributions. Both methods identified seven optimal clusters, as determined by the Elbow and Gap Statistic approaches, ensuring maximum between-cluster separation and minimal within-cluster variance. To statistically assess the homogeneity of the clusters—using the k-means result as a reference—the Hosking homogeneity index (H) was computed for each cluster (Table 2).

Table 2.

Hosking’s H-index values for k-means clusters.

Negative H values indicate that the dispersion of values within a cluster is lower than what would be expected for a homogeneous region derived from the overall dataset, thereby confirming that the clusters are acceptably homogeneous. Cluster 4 contained too few stations to allow for a reliable H calculation. It is important to note that, although the clusters are statistically homogeneous, the clustering approach—based solely on a single attribute () and station coordinates—does not guarantee full geographic contiguity or complete spatial coverage. As a result, certain areas remain unclassified, leaving spatial gaps in the regionalization. In conclusion, while clustering provides a useful data-driven method for identifying homogeneous groups, it fails to ensure complete territorial coverage, particularly in regions with sparse station density.

3.2. Isolines of the Main Parameters for the Annual Maximum Daily Rainfall

Figure 12, Figure 13 and Figure 14 present isoline maps for three key statistical parameters that characterize the annual maximum daily rainfall: the mean, standard deviation, and coefficient of variation.

Figure 12.

Isolines of the mean daily rainfall values.

Figure 13.

Isolines of the standard deviation of daily rainfall.

Figure 14.

Isolines of the coefficient of variation in annual maximum daily rainfall.

These maps illustrate the spatial variability of daily precipitation across Romania. Among the three parameters, only the isolines offer a viable basis for regionalization, as they effectively reflect normalized spatial variation. However, from a hydrological design perspective—particularly in urban areas and regions prone to flash flooding—sub-daily rainfall events are far more relevant. Daily maximum values are not suitable for such analyses, as the design of sewerage systems typically relies on rainfall durations corresponding to the time of concentration, which in Romanian conditions is generally around one hour. Moreover, small river basins are characterized by short concentration times, further reinforcing the need to use sub-daily rainfall data in modeling and infrastructure design.

3.3. Similarities Between Meteorological Stations Commented Results

The similarity between any pair of meteorological stations (i and j) was quantified using two statistical indicators: the Coefficient of Determination () and the Nash–Sutcliffe Efficiency (NSE), both calculated across all durations of the IDF curves corresponding to a 1:10 Annual Frequency of Exceedance (AFE). Given the symmetric nature of station-to-station similarity, the and NSE values were organized into an upper triangular matrix for efficient representation and analysis.

Table 3 presents the NSE coefficients for a selection of randomly chosen stations. In several cases, stations i and j are geographically close and belong to the same homogeneous cluster, as expected. However, high similarity scores are also observed between geographically distant stations. For example, Arad shows high NSE values not only with nearby stations such as Lugoj (69.62 km) and Timișoara (49.48 km), but also with distant ones like Fetești (546.98 km) and Bârlad (488.40 km), despite the orographic barrier of the Carpathian Mountains. These findings suggest that high R2 or NSE values do not necessarily imply spatial proximity or regional coherence.

Table 3.

NSE coefficients for a few randomly selected stations.

The high NSE values result from considering the full range of rainfall durations between 5 and 1440 min. When the analysis is restricted to shorter durations (e.g., 3 or 6 h), NSE values tend to decrease, although the overall similarity pattern remains largely unchanged. Thus, while and NSE are reliable metrics for assessing pointwise similarity between IDF curves, they are insufficient for delineating coherent regional rainfall patterns. High similarity scores may occur between stations that are geographically distant, meaning that similar IDF curves do not necessarily imply spatial proximity or continuity. Consequently, similarity-based approaches cannot be directly used for regionalization, as they may fail to capture the spatial structure and coherence required for hydrological modeling.

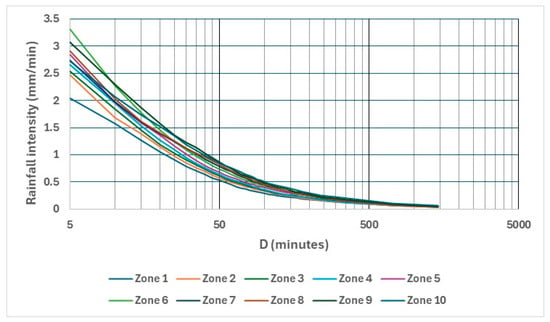

3.4. Regionalization Based on 1 h Accumulated Rainfall Depth

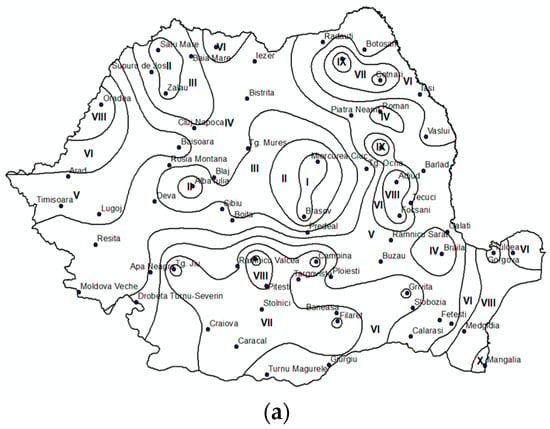

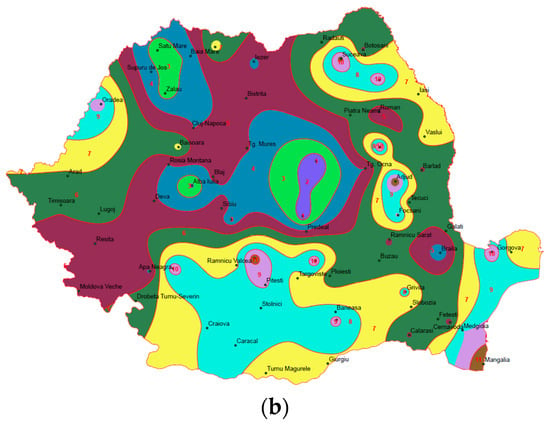

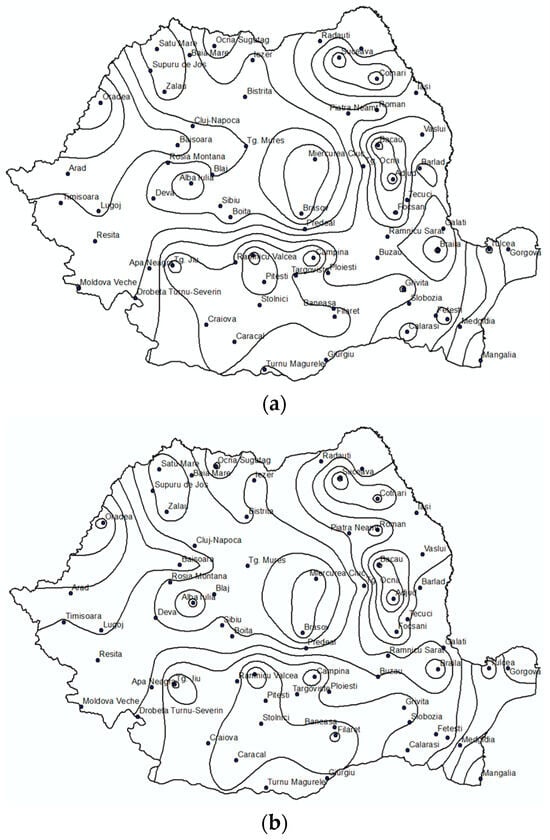

Urban catchments typically exhibit short hydrological response times, often less than one hour [52]. Consequently, the 1 h rainfall depth is a critical variable in urban hydrology and infrastructure design. Bell [53] developed a generalized IDF equation based on 1 h rainfall depths, and numerous subsequent studies—including Kuo et al. (2011)—have confirmed its practical relevance. Research conducted within the Pannonian Basin also frequently relies on sub-daily rainfall data—particularly 1 h, 3 h, and 6 h maxima—due to their implications for flash flood risk in mountainous areas [54]. Short-duration, high-intensity rainfall events are the main drivers of urban flash flooding, owing to the short concentration times characteristic of urban basins [28]. Therefore, the annual maximum 1 h rainfall depth was selected as the reference variable for regionalization, using a 1:10 Annual Frequency of Exceedance (AFE) threshold (Figure 15).

Figure 15.

Regionalization of 1 h rainfall depth for a 1:10 AFE: (a) Isolines; (b) Resulting polygons.

Most urban areas in Romania have a concentration time of less than one hour. The main exception is Bucharest, which spans approximately 250 km2 and has a concentration time of 2 h and 30 min. Future expansions or upgrades of sewerage systems are expected to adopt a design frequency of 1:10 AFE. Accordingly, the 1 h accumulated precipitation depth corresponding to a 1:10 AFE was selected as the basis for regionalization (Figure 15). The 1 h rainfall depths ranged from 26.8 mm to 46.6 mm. Based on this range, ten rainfall classes were defined: <28; 28–30; 30–32; …; 40–42; 42–44; and >44 mm. These intervals were used to delineate ten homogeneous regions across the country, forming the foundation of a new regionalization scheme proposed for 2025. Figure 15a presents the isolines of the 1 h rainfall depth, while Figure 15b shows the corresponding regionalization polygons derived from rainfall classes.

To evaluate the applicability of this regionalization across other rainfall frequencies, equivalent maps were generated for 1:5 and 1:20 AFEs (Figure 16), as well as for 1:50 and 1:100 AFEs. Only negligible spatial differences were observed between these maps, supporting the use of the 1:10 AFE regionalization as a representative baseline across all analyzed frequencies.

Figure 16.

Regionalization of 1 h rainfall depth: (a) 1:5 AFE; (b) 1:20 AFE.

To justify the selection of the 1 h precipitation isoline corresponding to the 10-year return period, basic statistical indicators (mean, standard deviation, and coefficient of variation, CV) were calculated for the raster layers representing 1 h rainfall values associated with the five AFE values (Table 4).

Table 4.

Statistical parameters as a function of Annual Frequency of Exceedance.

The coefficient of variation increases for lower AFE values, indicating greater spatial variability of extreme rainfall events. In contrast, the 1:10 AFE exhibits a moderate , offering an optimal balance between spatial coherence and the representativeness of intense rainfall. In addition, the 1:10 AFE aligns with European Union guidelines for urban sewerage system design, further reinforcing its suitability as a reference frequency for regional analyses. For each delineated zone, a representative meteorological station was selected based on the highest IDF curve intensities corresponding to the 1:10 AFE condition.

3.5. Summary Remarks on Regionalization Approaches

Several regionalization methods were evaluated, each with specific strengths and limitations:

- Clustering techniques—Provided valuable insights but failed to ensure complete national coverage, leaving unclassified spatial areas.

- Daily rainfall-based maps—Useful for general climatic characterization, but inadequate for modeling short-duration, high-intensity events relevant to urban hydrology.

- Station similarity (, NSE)—Demonstrates high pairwise similarity even across distant stations, which undermines its effectiveness for spatial delineation.

- One-hour rainfall depth at 1:10 AFE—Offers the best national coverage and practical applicability. It aligns with typical urban concentration times and with European design standards, making it the most suitable basis for updated regionalization.

The representativity of the 1:10 AFE regionalization was primarily assessed through comparative visual analysis. Specifically, the isolines for the 1:10 AFE were compared to those corresponding to lower frequencies (1:50 and 1:100), focusing on the spatial coherence of regional boundaries. This qualitative assessment was further supported by examining the consistency between each AFE map and the spatially continuous fields of the three parameters in the Sherman equation, calculated for the same frequencies. Although no quantitative stability metrics (e.g., spatial overlap indices) were computed at this stage, the visual consistency of regional boundaries across different AFEs suggests that the 1:10 AFE configuration provides a reasonable and stable foundation for regionalization. Incorporating quantitative boundary stability indicators is recommended as a future step toward refining and validating this approach.

4. Discussion

4.1. Considerations Regarding the Coefficients a, b, and c

For each of the ten homogeneous zones identified in Sub-Section 3.4, the parameters , , and of the IDF curves were estimated (see Table 5, Table 6, Table 7, Table 8 and Table 9). These coefficients enable analytical interpolation for non-standard rainfall durations, based on the Sherman equation.

Table 5.

Estimated coefficients and for the 1:5 AFE intensity (expressed in mm/min).

Table 6.

Estimated coefficients , , and for the 1:10 AFE intensity (expressed in mm/min).

Table 7.

Estimated coefficients , and for the 1:20 AFE intensity (expressed in mm/min).

Table 8.

Estimated coefficients , , and for the 1:50 AFE intensity (expressed in mm/min).

Table 9.

Estimated coefficients , and for the 1:100 AFE intensity (expressed in mm/min).

The theoretical constraints defined in Equation (6) are only partially satisfied in practice. For two frequencies and , where > , the following inequality should hold:

with the following parameter equivalences:

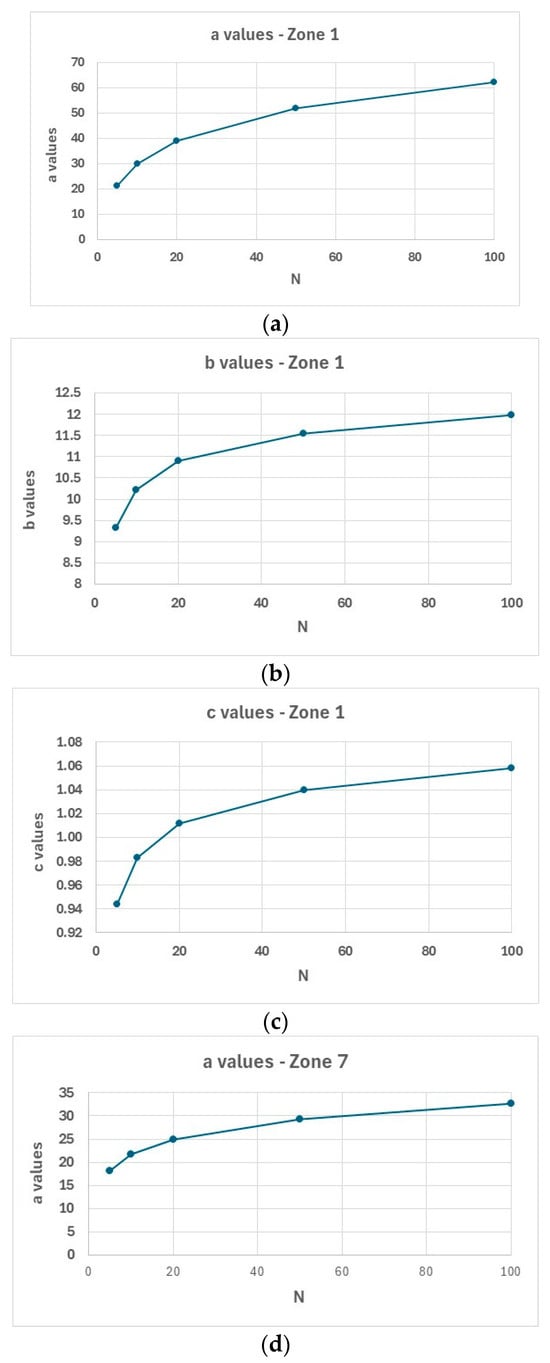

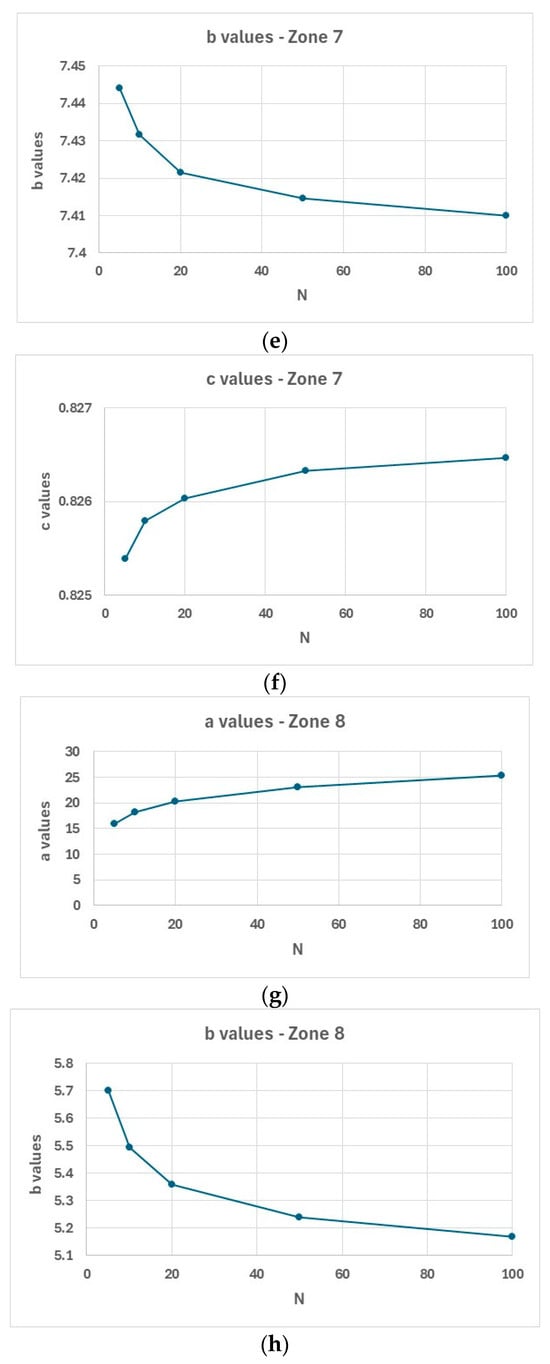

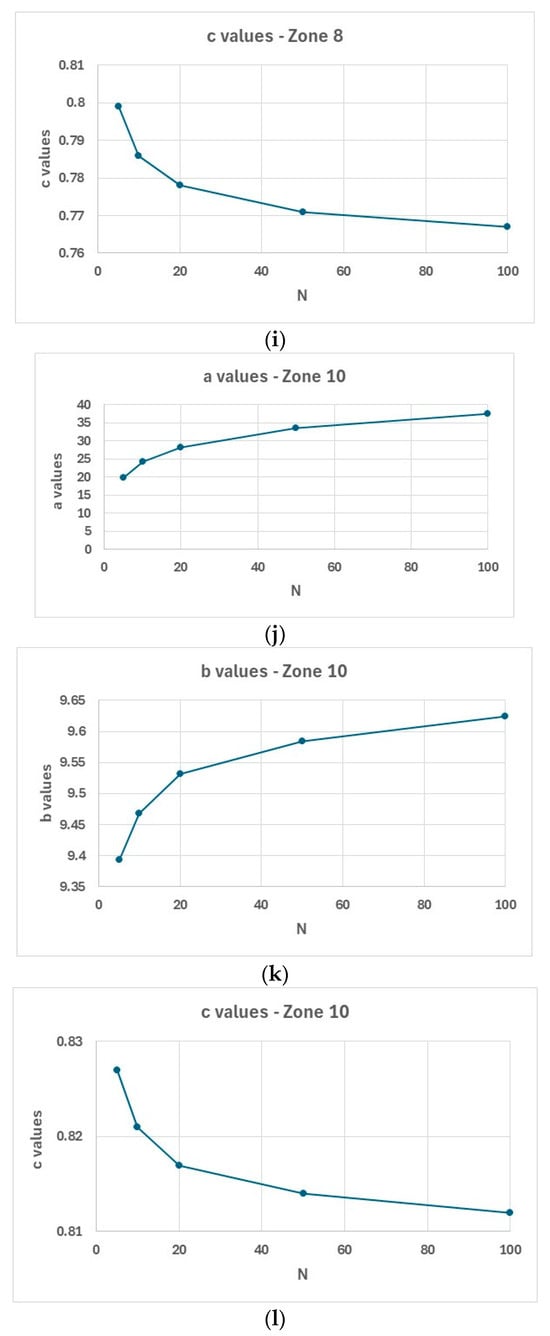

Figure 17 illustrates the variation in these coefficients across homogeneous zones 1, 7, 8, and 10.

Figure 17.

Coefficients plots: (a–c)—zone 1; (d–f)—zone 7; (g–i)—zone 8; (j–l)—zone 10; Panels by parameter: (a,d,g,j)—coefficient ; (b,e,h,k)—coefficient ; (c,f,i,l)—coefficient .

The coefficients , , and in the Sherman IDF equation are functions of the Annual Frequency of Exceedance (AFE) of rainfall. Among them, only coefficient shows a consistent trend across all zones: it increases as AFE decreases, meaning that rarer rainfall events (e.g., 1:50, 1:100) are associated with higher values. In contrast, coefficients and (i.e., and ) exhibit zone-dependent behaviors:

- They may increase or decrease monotonically with frequency;

- Their variation is not always synchronized;

- They generally show limited variability.

This supports the conclusion of Koutsoyiannis et al. [3], who demonstrated that real-world families of IDF curves can often be well approximated by assuming constant values for and , i.e., and . An interesting observation is that coefficient is typically subunitary, except for zone 1, where values slightly exceed 1 for AFE values greater than 1:10.

When the variability of the coefficients is expressed as a function of the frequency F, the general IDF relationship (Equation (7)) can be reformulated as

4.2. Variability Within Homogeneous Zones

As revealed by at-site frequency analysis (AFA), multiple IDF curves can be distinguished within zones 4 and 5, even though the differences between them are relatively minor (see Figure 18). To more effectively illustrate these subtle variations in rainfall intensities, the ordinate axis in the figure was plotted using a Cartesian (linear) scale, which enhances the visibility of inter-curve differences.

Figure 18.

IDF curves for a 1:10 AFE: (a)—zone 4; (b)—zone 5.

The discrepancies between the extreme IDF curves within each zone reach 19.6% in zone 4 and 21.5% in zone 5. To ensure robust and conservative design parameters, the most conservative IDF curve was selected for each zone, rather than relying on average values. Figure 19 presents the resulting representative IDF curves for all ten homogeneous zones, based on this selection approach.

Figure 19.

Representative IDF curves for the ten homogeneous areas.

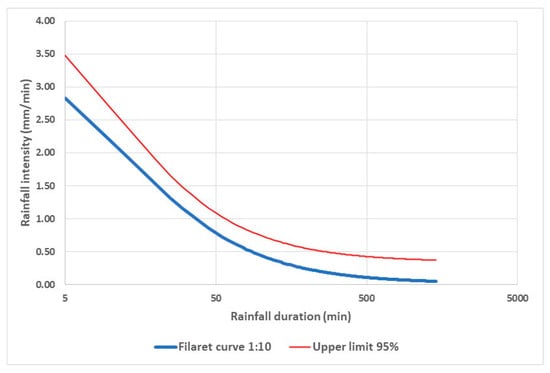

4.3. Uncertainty of Representative IDF Curves

The derivation of IDF curves is inherently affected by two types of uncertainty:

- Epistemic uncertainty, resulting from incomplete knowledge about the true statistical distribution of extreme rainfall;

- Aleatory uncertainty, reflecting natural variability and the limitations of available data series.

These sources of uncertainty impact both the parameter estimation and the resulting IDF curves themselves. Under current operational conditions in Romania, the National Meteorological Administration (ANM) exclusively employs the Gumbel distribution to model annual maxima. This approach does not account for epistemic uncertainty, as it assumes a fixed distribution form, regardless of local or regional deviations from the Gumbel behavior.

Moreover, the number of weather stations with long-term, continuous datasets remains relatively limited, which further contributes to aleatory uncertainty. To address this issue, confidence intervals can be computed either for the IDF coefficients or directly for the resulting curves. A confidence interval defines a range within which the true value of a parameter is expected to lie, with a specified probability—typically 95%. As formulated by [55], “there is a 95% probability that the 95% confidence interval calculated from a given future sample will include the true value of the population parameter.”

Common techniques for estimating confidence intervals include bootstrapping and applications of the Central Limit Theorem (CLT). In this study, the CLT-based approach was used. Figure 20 illustrates the confidence interval for the IDF curve corresponding to the Filaret weather station (Zone 9). For practical purposes, only the upper confidence bound is shown in the figure, representing a conservative estimate relevant for hydrological design.

Figure 20.

IDF curve and the upper bound of its 95% confidence interval at Filaret meteorological station (Zone 9), illustrating the conservative envelope used in hydrological design.

The maximum deviation observed between the IDF curve and its upper confidence limit is approximately 17.5%. This deviation is significant from a design perspective, particularly when accounting for both climate change-induced hazards and the vulnerability of critical infrastructure. To address these compounded risks, the upcoming revision of the Romanian standard—STAS 9470:2025 [56]—proposes the introduction of safety coefficients, calibrated based on the importance category of the construction (e.g., residential, critical infrastructure, industrial). These coefficients are detailed in Table 10.

Table 10.

Safety factors proposed for urban flood risk management under the new Romanian Standard STAS 9470:2025, differentiated by building importance category.

The introduction of these safety factors represents a first and necessary step toward more effective urban flood risk management in the context of increasingly frequent and intense precipitation events. To enhance decision-making in the design and performance evaluation of stormwater conveyance systems, future developments should incorporate cost–benefit analyses that account for both direct and indirect impacts. This approach aligns with the provisions of the European Standard EN 752-2, which differentiates between rural areas, residential zones, industrial/commercial districts, and urban cores, while explicitly considering the tangible and intangible consequences of flooding [33,34].

4.4. Climate Change Investigation

The 1973 regionalization was developed based on historical rainfall records available at that time, while the proposed 2025 regionalization relies on more recent data collected over the past 30 years. Although the two datasets are non-overlapping, their comparison enables a valuable assessment of temporal changes in rainfall intensity patterns, offering insights into the impact of climate change on extreme precipitation across Romania.

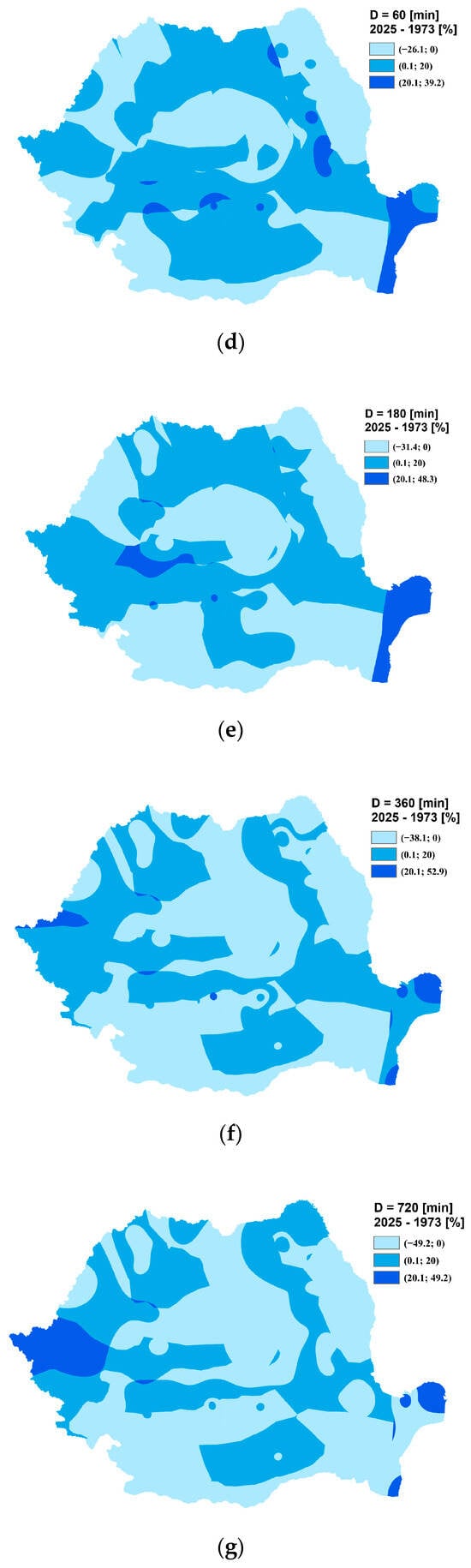

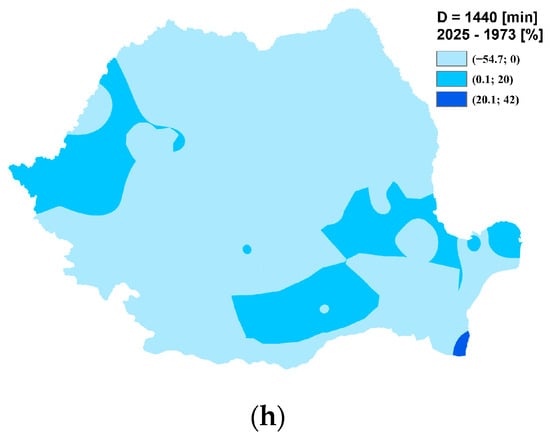

To evaluate the influence of climate change on rainfall regimes, raster datasets corresponding to the 2025 and 1973 regionalizations were comparatively analyzed across multiple rainfall durations. The computed percentage differences reveal a pronounced intensification of short-duration rainfall events, particularly in the 5- to 10 min range:

- For the 5 min duration, increases between 10% and 71% were recorded (Figure 21a);

Figure 21. Percentage differences in rainfall depth between the 2025 and 1973 regionalization, by rainfall duration: (a) 5 min; (b) 10 min; (c) 30 min; (d) 60 min; (e) 180 min; (f) 360 min; (g) 720 min; (h) 1440 min.

Figure 21. Percentage differences in rainfall depth between the 2025 and 1973 regionalization, by rainfall duration: (a) 5 min; (b) 10 min; (c) 30 min; (d) 60 min; (e) 180 min; (f) 360 min; (g) 720 min; (h) 1440 min. - The 10 min duration showed increases ranging from 10% to 46.8% (Figure 21b);

- For intermediate durations (30–60 min), the spatial distribution of changes was more heterogeneous, with relatively balanced areas experiencing either increases or decreases in rainfall depth (Figure 21c,d);

- In contrast, longer durations (180–360 min) exhibited a predominance of negative changes, suggesting a trend toward reduced precipitation accumulation during extended rainfall events (Figure 21e,f);

- Finally, for durations of 720 and 1440 min, clearly dominant decreasing trends were observed (Figure 21g,h), indicating a general decline in total rainfall volume for events of daily or near-daily scale.

These findings corroborate results from the Pannonian Basin Experiment (PannEx), developed under the Global Energy and Water Exchanges Project (GEWEX) [54]. Within this framework, high-resolution analyses of hourly precipitation datasets across the Pannonian–Carpathian Basin highlighted significant spatial variability in both annual and absolute 1 h maxima. Between 1998 and 2019, seasonal spatial patterns of 1 h rainfall intensities varied markedly. In Hungary, recent decades have shown shortened return/exceedance periods for extreme short-duration events, indicating a notable increase in frequency [58]. In the Czech Republic, an analysis covering the 1961–2011 period revealed that stations with statistically significant positive trends in sub-daily summer precipitation outnumbered those with negative trends. This suggests a general intensification of convective events, accompanied by shorter durations and higher peak intensities. Comparable or slightly lower 1 h rainfall maxima were reported in Slovenia, Croatia, and Romania, according to medium-term observational records (31–50 years). In contrast, stations with longer observation periods (>50 years) in Central–Western Romania (Transylvania region) consistently recorded lower 1 h maxima compared to southern regions. However, no consistent spatial trend was identified, and temporal coherence remained ambiguous. Approximately 70% of the analyzed Standardized Precipitation Intensity Index time series showed positive trends; however, localized negative trends were also identified, particularly in the southeastern Carpathians.

To highlight the changes in rainfall values, we calculated the percentage differences in precipitation intensity for the main cities in Romania (Table 11).

Table 11.

Percentage Differences in Precipitation Intensity.

It can be observed that, in most cases, the increase in rainfall intensity occurs over short durations. The maximum increase is approximately 30%, which has implications for the existing infrastructure and for the planned expansion of the sewerage network.

5. Conclusions

Comparative analysis of rainfall depths over various durations between the 1973 and 2025 regionalizations revealed significant shifts attributable to climate change, most notably an increase in rainfall intensity over shorter durations. These findings provide crucial insights for climate adaptation planning. The observed trends of increasing short-duration rainfall intensities and decreasing long-duration intensities, as reflected in the updated IDF curves, align with broader regional and continental observations. Recent climatological studies have reported a general intensification of convective precipitation in Central and Eastern Europe, associated with warming temperatures and increased atmospheric moisture availability [59,60]. Moreover, regional climate model projections over the Carpathian Basin suggest a shift toward more frequent and intense short-duration rainfall events [61]. While a formal climate attribution analysis was not conducted in this study, the IDF changes documented here are consistent with physically plausible mechanisms, such as enhanced convective activity and altered precipitation regimes under climate change. Further research incorporating reanalysis datasets (e.g., ERA5) or regional climate simulations could improve understanding of the atmospheric drivers behind these trends.

The two IDF datasets (those corresponding to STAS 9470:1973 and the upcoming STAS 9470:2025) are based on non-overlapping time periods. This raises the possibility of confounding climate signals with data heterogeneity. Since the two standards do not share a common reference period, a formal consistency check to isolate data heterogeneity is not feasible. As such, the comparative approach adopted here should be interpreted as exploratory, aiming to highlight long-term trends rather than to establish direct statistical equivalence. In addition to the effects of climate change, further sources of variability may arise from differences in data quality, instrumentation, and spatial or temporal coverage between the two reference periods. These differences represent an inherent limitation of the comparative analysis.

Given the growing hazard posed by extreme rainfall events and the varying vulnerability of different building categories, updated design guidelines now incorporate safety coefficients applied to scale IDF values. These revisions, formally introduced in the updated Romanian standard STAS 9470:2025, aim to enhance urban resilience to pluvial flooding. This approach aligns with international guidelines (e.g., EN 752-2), which advocate for differentiated hydrological design based on land use, exposure, and potential economic losses. The integration of climate-informed safety factors and zone-specific IDF curves represents a significant advancement toward a comprehensive, risk-based design paradigm for urban stormwater systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.D. and N.S.; methodology, R.D. and N.S.; software, N.S.; validation, N.S., R.D. and G.R.; resources, G.R.; writing—original draft preparation, R.D.; writing—review and editing, N.S. and G.R.; visualization, N.S.; supervision, G.R.; project administration, G.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The present work was funded by the Romanian Ministry of Public Works and Development through the National Romanian Standardization Organism, being a part of the effort for revision of the original national Romanian standards.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to access to the national standards, which requires approval of the National Romanian Standardization Organism.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| IDF | Intensity–Duration–Frequency curves |

| AFA | At-site frequency analysis |

| AFE | Annual Frequency of Exceedance |

| RFA | Regional frequency analysis |

| STAS | State standard (or state norms in Romania) |

| ANM | National Administration of Meteorology, Bucharest, Romania |

References

- Chow, V.T.; Maidment, D.R.; Mays, L.W. Applied Hydrology; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1988; pp. 383–384, 446–451, 454–459. [Google Scholar]

- Maidment, D.R. Handbook of Hydrology; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 50–52. [Google Scholar]

- Koutsoyiannis, D.; Kozonis, D.; Manetas, A. A mathematical framework for studying rainfall intensity-duration-frequency relationships. J. Hydrol. 1998, 206, 118–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeleb, A.M.; Fajriani, Q.R.; Ximenes, M.A. Determination of Rainfall Intensity Formula and Itensity-Duration-Frequency (IDF) Curve at the Quelicai Administrative Post, Timor-Leste. Timor-Leste J. Eng. Sci. 2022, 3, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Nhat, L.M.; Tachikawa, Y.; Takara, K. Establishment of Intensity-Duration-Frequency Curves for Precipitation in the Monsoon Area of Vietnam. Annu. Disas. Prev. Rest. Inst. Kyoto Univ. 2006, 49B, 93–103. [Google Scholar]

- Kite, G.W. Frequency and Risk Analysis in Hydrology; Fourth Printing; Water Resources Publications: Fort Collins, CO, USA, 1988; pp. 4–26. [Google Scholar]

- Stedinger, J.R.; Vogel, R.M.; Foufoula-Georgiou, E. Frequency Analysis of Extreme Events. In Handbook of Hydrology; Maidment, D.R., Ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 37–42. [Google Scholar]

- Meylan, P.; Favre, A.C.; Musy, A. Hydrologie Fréquentielle—Une Science Predictive; Presses Polytechniques et Universitaires Romandes, EPFL: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2008; pp. 119–131. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Zvi, A. Rainfall intensity–duration–frequency relationships derived from large partial duration series. J. Hydrol. 2009, 367, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, V.T. Handbook of Applied Hydrology; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1964; pp. 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Yevjevich, V. Probability and Statistics in Hydrology; Water Resources Publications: Littleton, CO, USA, 1972; pp. 68–82. [Google Scholar]

- Cunnane, C. A particular comparison of annual maxima and partial duration series methods of flood frequency prediction. J. Hydrol. 1973, 18, 257–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunnane, C. Unbiased and biased estimators of the distribution of maximum daily precipitation. Water Resour. Res. 1978, 14, 799–804. [Google Scholar]

- Cunnane, C. One-dimensional and multi-dimensional frequency analysis of floods. Hydrol. Sci. J. 1989, 34, 541–557. [Google Scholar]

- Cunnane, C. Statistical Distributions for Flood Frequency Analysis; Secretariat of the World Meteorological Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1989; pp. 1–61. Available online: https://library.wmo.int/viewer/33760/download?file=wmo_718.pdf&type=pdf&navigator=1 (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Koutsoyiannis, D. Statistics of extremes and estimation of extreme rainfall: I. Theoretical investigation. Hydrol. Sci.—J. Des Sci. Hydrol. 2004, 49, 575–590. [Google Scholar]

- Drobot, R.; Draghia, A.F.; Ciuiu, D.; Trandafir, R. Design Floods Considering the Epistemic Uncertainty (Appendix A). Water 2021, 13, 1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, H.; Rasmussen, P.F.; Rosbjerg, D. Comparison of annual maximum series and partial duration series methods for modeling extreme hydrologic events. 1. At-site modeling. Water Resour. Res. 1997, 33, 747–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, H.; Pearson, C.P.; Rosbjerg, D. Comparison of annual maximum series and partial duration series methods for modeling extreme hydrologic events. 2. Regional modeling. Water Resour. Res. 1997, 33, 759–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, E.S.; Stedinger, J.R. Historical information in a generalized maximum likelihood framework with partial duration and annual maximum series. Water Resour. Res. 2001, 37, 2559–2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, D.S., Jr.; Stedinger, J.R. Bayesian MCMC flood frequency analysis with historical information. J. Hydrol. 2005, 313, 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- England, J.F., Jr.; Cohn, T.; Faber, B.; Stedinger, J.R.; Thomas, W.O., Jr.; Veilleux, A.G.; Kiang, J.E.; Mason, R.R., Jr. Guidelines for Determining Flood Flow Frequency Bulletin 17 C. Chapter 5 of Section B, Surface Water. In Book 4, Hydrologic Analysis and Interpretation; Techniques and Methods 4–B5, Version 1.1; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VI, USA, 2019; pp. 5–18. [Google Scholar]

- Madsen, H.; Mikkelsen, P.S.; Rosbjerg, D.; Harremoës, P. Regional estimation of rainfall intensity-duration-frequency curves using generalized least squares regression of partial duration series statistics. Water Resour. Res. 2002, 38, 21.1–21.11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsoyiannis, D. Statistics of extremes and estimation of extreme rainfall: II. Empirical investigation of long rainfall records. Hydrol. Sci.—J. Des Sci. Hydrol. 2004, 49, 591–610. [Google Scholar]

- Koutsoyiannis, D. On the appropriateness of the Gumbel distribution in modelling extreme rainfall. In Proceedings of the ESF LESC Exploratory Workshop, Bologna, Italy, 24–25 October 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, K.B.; Lai, S.H.; Faridah, O. RainIDF: Automated derivation of rainfall intensity–duration–frequency relationship from annual maxima and partial duration series. J. Hydroinform. 2013, 15, 1224–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, M.K.; Gupta, V. Identification of Homogeneous Rainfall Regimes in Northeast Region of India using Fuzzy Cluster Analysis. Water Resour. Manag. 2014, 28, 4491–4511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Sung, K.; Shin, J.-Y.; Heo, J.-H. At-Site Versus Regional Frequency Analysis of Sub-Hourly Rainfall for Urban Hydrology Applications During Recent Extreme Events. Water 2025, 17, 2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deidda, R.; Hellies, M.; Langousis, A. A critical analysis of the shortcomings in spatial frequency analysis of rainfall extremes based on homogeneous regions and a comparison with a hierarchical boundaryless approach. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2021, 35, 2605–2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minguez, R.; Herrera, S. Spatial extreme model for rainfall depth: Application to the estimation of IDF curves in the Basque country. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2023, 37, 3117–3148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nhat, L.M.; Tachikawa, Y.; Sayama, T.; Takara, K. Derivation of Rainfall Intensity-Duration-Frequency Relationships for Short-Duration Rainfall from Daily Data. In Proceedings of the International Symposium of Managing Water Supply for Growing Demand, Bangkok, Thailand, 16–20 October 2006; IHP Technical Document in Hydrology. No. 6. pp. 89–96. [Google Scholar]

- EN 752:2017/pr.A1; Drain and Sewer Systems Outside Buildings—Sewer System Management. European Standard; CEN-CENELEC Management Centre: Brussels, Belgium, 2017.

- Schmitt, T.G.; Schilling, W.; Sasgrov, S.; Nieschulz, K.P. Flood risk management for urban drainage systems by simulation and optimization. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Urban Drainage, Portland, OR, USA, 8–13 September 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, T.G.; Thomas, M.; Ettrich, N. Analysis and modeling of flooding in urban drainage systems. J. Hydrol. 2004, 299, 300–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Development, Public Works and Administration. NP 133-2022 Regulation on the Design, Execution and Operation of Water Supply and Sewerage Systems of Localities, Volume II, Sewerage Systems; Ministry of Development, Public Works and Administration: Bucharest, Romania, 2022. (In Romanian) [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Romania (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Stănescu, V.A.; Drobot, R. Non-Structural Measures for Flood Management; HGA: Bucharest, Romania, 2002; pp. 80–86. (In Romanian) [Google Scholar]

- STAS 9470-73; Maximum Rainfall. Intensity-Duration-Frequency. Romanian Institute of Standardization: Bucharest, Romania, 1973. (In Romanian)

- Yang, S.; Wang, X.; Guo, J.; Chang, X.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Ju, S. Trend Analysis of Extreme Precipitation and Its Compound Events with Extreme Temperature Across China. Water 2025, 17, 2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsoyiannis, D.; Baloutsos, G. Analysis of a long record of annual maximum rainfall in Athens, Greece, and design rainfall inferences. Nat. Hazards 2000, 22, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, Y.-M.; Chu, H.-J.; Pan, T.-Y.; Yu, H.-L. Investigating common trends of annual maximum rainfall during heavy rainfall events in southern Taiwan. J. Hydrol. 2011, 409, 749–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rugină, A.M. Alternative Hydraulic Modeling Method Based on Recurrent Neural Networks: From HEC-RAS to AI. Hydrology 2025, 12, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Vyver, H. Bayesian estimation of rainfall intensity–duration–frequency relationships. J. Hydrol. 2015, 529, 1451–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everitt, B.S.; Landau, S.; Leese, M.; Stahl, D. Cluster Analysis, 5th ed.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2011; pp. 1–330. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, A.K. Data Clustering—50 Years Beyond K-Means. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2010, 31, 651–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legendre, P.; Legendre, L. Numerical Ecology, 3rd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; Volume 24, pp. 1–1006. [Google Scholar]

- Ester, M.; Kriegel, H.P.; Sander, J.; Xu, X.A. Density-Based Algorithm for Discovering Clusters in Large Spatial Databases with Noise. In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (KDD-96), Portland, OR, USA, 2–4 August 1996; AAAI Press: Menlo Park, CA, USA; pp. 226–231. [Google Scholar]

- Daszykowski, M.; Walczak, B. Clustering of Multivariate Data—A Survey. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2009, 96, 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Charrad, M.; Ghazzali, N.; Boiteau, V.; Niknafs, A. NbClust—An R Package for Determining the Relevant Number of Clusters in a Data Set. J. Stat. Softw. 2014, 61, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennig, C.; Meila, M.; Murtagh, F.; Rocci, R. (Eds.) Handbook of Cluster Analysis; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016; pp. 1–754. [Google Scholar]

- Saxena, A.; Mittal, M.; Goyal, L.M. Comparative Analysis of Clustering Methods. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 2015, 118, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, T.D.; Andrieu, H.; Hamel, P. Understanding, management and modelling of urban hydrology and its consequences for receiving waters: A state of the art. Adv. Water Resour. 2013, 51, 261–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, F.C. Generalized rainfall-duration-frequency relationships. J. Hydraul. Div. Am. Soc. Civ. Eng. 1969, 95, 311–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakatos, M.; Szentes, O.; Cindric Kalin, K.; Nimac, I.; Kozjek, K.; Cheval, S.; Dumitrescu, A.; Irașoc, A.; Stepanek, P.; Farda, A.; et al. Analysis of Sub-Daily Precipitation for the PannEx Region. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neyman, J. Outline of a Theory of Statistical Estimation Based on the Classical Theory of Probability. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 1937, 236, 333–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- STAS 9470-2005; Maximum Rainfall. Intensity-Duration-Frequency. National Romanian Standardization Organism: Bucharest, Romania, 2025. (In Romanian)

- REGULATION of November 21, 1997 on the Classification of Building Importance (Annex No. 3). Available online: https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocumentAfis/194015 (accessed on 20 December 2025). (in Romanian).

- Lakatos, M.; Izsák, B.; Szentes, O.; Hoffmann, L.; Kircsi, A.; Bihari, Z. Return values of 60-minute extreme rainfall for Hungary. Időjárás 2020, 124, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Púčik, T.; Groenemeijer, P.; Rýva, D.; Kolář, M. Proximity soundings of severe and nonsevere thunderstorms in Central Europe. Mon. Weather. Rev. 2017, 143, 4805–4821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prein, A.F.; Langhans, W.; Fosser, G.; Ferrone, A.; Ban, N.; Goergen, K.; Keller, M.; Tölle, M.; Gutjahr, O.; Feser, F.; et al. A review on regional convection-permitting climate modeling: Demonstrations, prospects, and challenges. Rev. Geophys. 2016, 53, 323–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartholy, J.; Pongrácz, R.; Kis, A. Projected changes of extreme precipitation using a multi-model approach. Időjárás 2015, 119, 129–142. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.