First Evidence into the Association of Warming with Stroke and Myocardial Infarction Mortality in the Brazilian Amazon

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

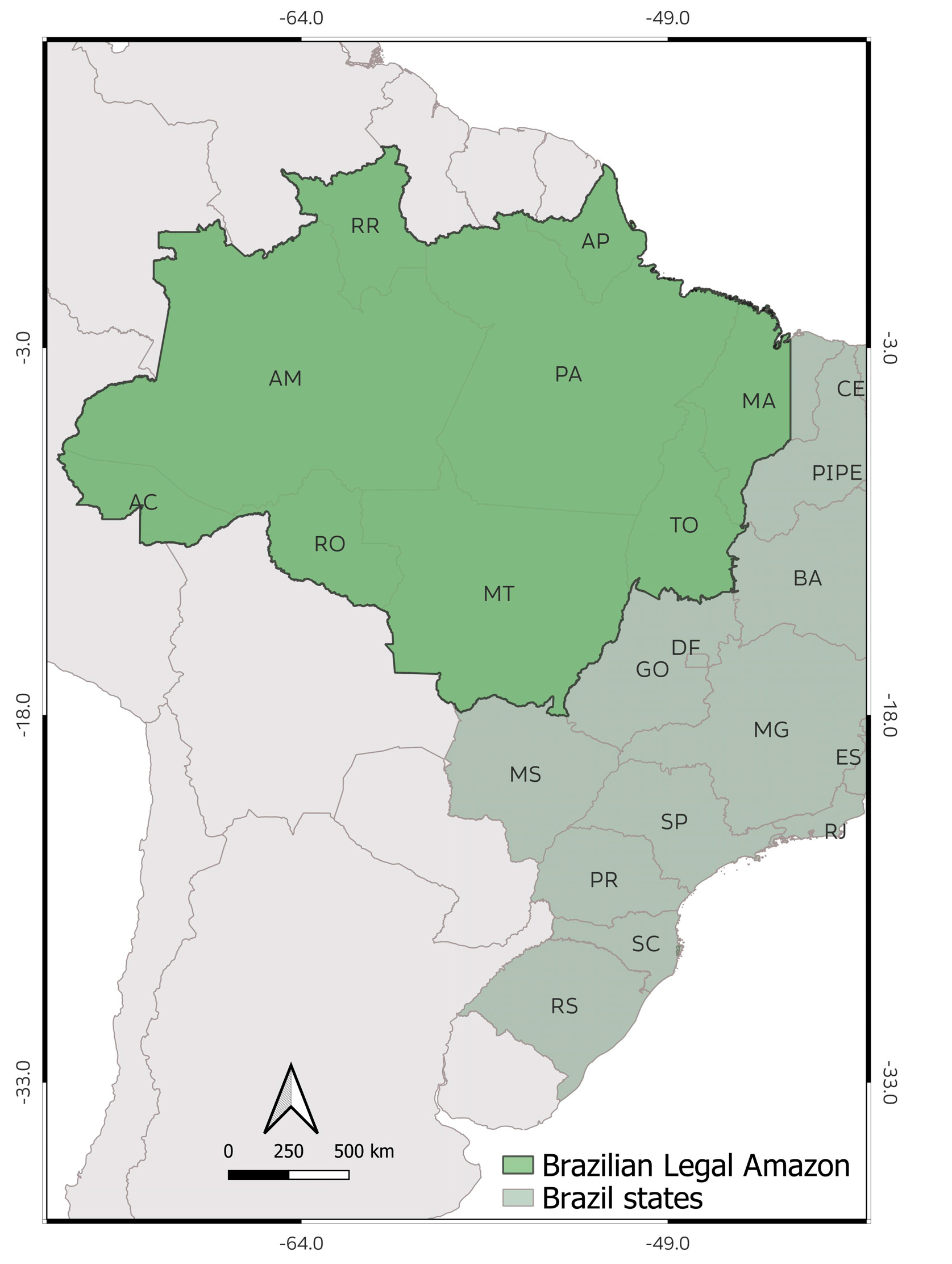

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Statistical Modeling

2.4. Ethical Aspects

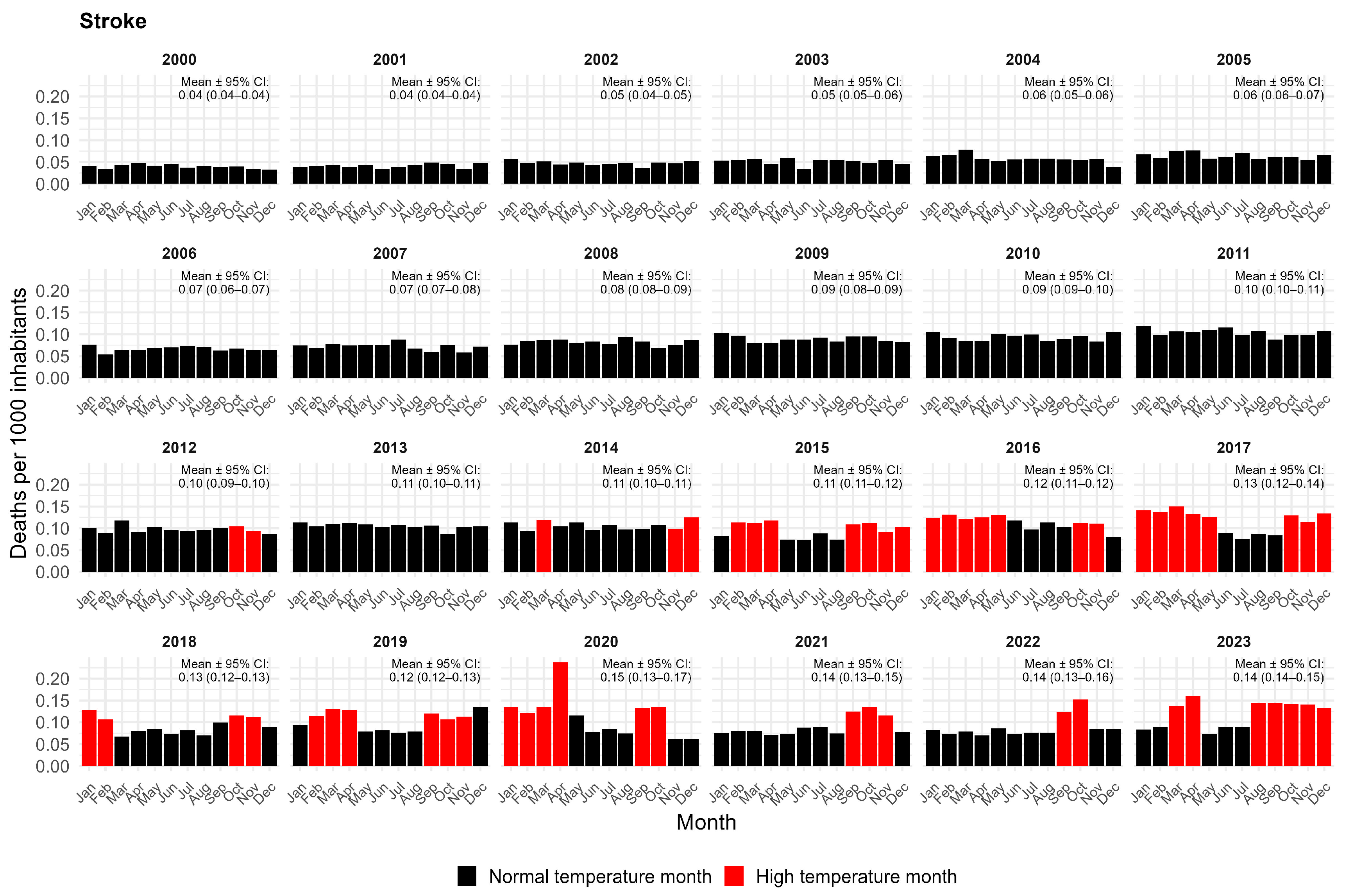

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Model | Stroke | Myocardial Infarction | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Β | p | β | p | |

| excluding extreme years (2000 and 2023) | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.002 |

| temporal 1 month lag | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.02 |

| temporal 2 months lag | 0.03 | 0.001 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| temporal 3 months lag | 0.04 | 0.0001 | 0.02 | 0.001 |

| underreporting (10%) | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.003 |

| overreporting (10%) | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.003 |

References

- Heidari, H.; Mohammadbeigi, A.; Khazaei, S.; Soltanzadeh, A.; Asgarian, A.; Saghafipour, A. The Effects of Climatic and Environmental Factors on Heat-Related Illnesses: A Systematic Review from 2000 to 2020. Urban Clim. 2020, 34, 100720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddington, C.L.; Smith, C.; Butt, E.W.; Baker, J.C.A.; Oliveira, B.F.A.; Yamba, E.I.; Spracklen, D.V. Tropical Deforestation Is Associated with Considerable Heat-Related Mortality. Nat. Clim. Change 2025, 15, 992–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Lin, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J. Study on the health effect of temperature on cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases in Haikou City. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phung, V.L.H.; Oka, K.; Honda, Y.; Hijioka, Y.; Ueda, K.; Seposo, X.T.; Sahani, M.; Wan Mahiyuddin, W.R.; Kim, Y. Daily Temperature Effects on Under-Five Mortality in a Tropical Climate Country and the Role of Local Characteristics. Environ. Res. 2023, 218, 114988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Nie, X.; Xu, R.; Han, G.; Wang, D. Burden Trends and Future Predictions for Hypertensive Heart Disease Attributable to Non-Optimal Temperatures in the Older Adults Amidst Climate Change, 1990-2021. Front. Public Health 2025, 12, 1525357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkart, K.; Khan, M.H.; Kraemer, A.; Breitner, S.; Schneider, A.; Endlicher, W.R. Seasonal variations of all-cause and cause-specific mortality by age, gender, and socioeconomic condition in urban and rural areas of Bangladesh. Int. J. Equity Health 2011, 10, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottino, M.J.; Nobre, P.; Giarolla, E.; da Silva Junior, M.B.; Capistrano, V.B.; Malagutti, M.; Tamaoki, J.N.; de Oliveira, B.F.A.; Nobre, C.A. Amazon savannization and climate change are projected to increase dry season length and temperature extremes over Brazil. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Castro Martins Ferreira, L.; Nogueira, M.C.; de Britto Pereira, R.V.; Marcia de Farias, W.C.; de Souza Rodrigues, M.M.; Bustamante Teixeira, M.T.; Carvalho, M.S. Ambient temperature and mortality due to acute myocardial infarction in Brazil: An ecological study of time-series analyses. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 13790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, H.E.; Zimmermann, N.E.; McVicar, T.R.; Vergopolan, N.; Berg, A.; Wood, E.F. Present and future Köppen-Geiger climate classification maps at 1-km resolution. Sci. Data 2018, 5, 180214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hyndman, R.J.; Khandakar, Y. Automatic time series forecasting: The forecast package for R. J. Stat. Softw. 2008, 27, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasparrini, A. Distributed lag linear and non-linear models in R: The package dlnm. J. Stat. Softw. 2011, 43, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsad, F.S.; Hod, R.; Ahmad, N.; Ismail, R.; Mohamed, N.; Radi, M.F.M.; Osman, Y.; Baharom, M.; Tangang, F. Temperature Related Mortality in a Tropical Climate Country: A Time Series Analysis. Med. Health 2025, 20, 723–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Wang, L.; Wang, S.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Wang, J. Spatial and temporal characteristics of temperature effects on cardiovascular disease in Southern China using the Empirical Mode Decomposition method. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 14775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Luo, B.; Wang, B.; He, L.; Wu, H.; Hou, L.; Zhang, K. Global Spatiotemporal Trends of Cardiovascular Diseases Due to Temperature in Different Climates and Socio-Demographic Index Regions from 1990 to 2019. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 3282–3292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cascio, W.E. Wildland fire smoke and human health. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 624, 586–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattioli, A.V.; Puviani, M.B.; Nasi, M.; Farinetti, A. COVID-19 pandemic: The effects of quarantine on cardiovascular risk. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 74, 852–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivimäki, M.; Steptoe, A. Effects of stress on the development and progression of cardiovascular disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2018, 15, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, A.F.W.; Ho, J.; Ong, M.; Aik, J. Influence of ambient temperature and absolute humidity on sudden cardiac arrest in Singapore: A nationwide time-series study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2025, 79, 954–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, L.; Yan, M.M.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Wang, K.; Wang, Y.Q.; Luo, S.Q.; Wang, F. Global Burden of Cardiovascular Disease Attributable to High Temperature in 204 Countries and Territories from 1990 to 2019. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 2023, 36, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walkowiak, M.P.; Walkowiak, D.; Walkowiak, J. Exploring the paradoxical nature of cold temperature mortality in Europe. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 3181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kephart, J.L.; Sánchez, B.N.; Moore, J.; Schinasi, L.H.; Bakhtsiyarava, M.; Ju, Y.; Gouveia, N.; Caiaffa, W.T.; Dronova, I.; Arunachalam, S.; et al. City-level impact of extreme temperatures and mortality in Latin America. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 1700–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorking, N.; Wood, A.D.; Tiamkao, S.; Clark, A.B.; Kongbunkiat, K.; Bettencourt-Silva, J.H.; Sawanyawisuth, K.; Kasemsap, N.; Mamas, M.A.; Myint, P.K. Seasonality of stroke: Winter admissions and mortality excess a Thailand national stroke population database study. Clin. Neurosurg. 2020, 199, 106261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaiciulis, V.; Jaakkola, J.J.K.; Radisauskas, R.; Tamosiūnas, A.; Luksiene, D.; Ryti, N.R.I. Association between winter cold spells and acute myocardial infarction in Lithuania 2000–2015. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 17062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; He, Y.; Huang, G.; Zeng, Y.; Lu, J.; He, R.; Chen, H.; Gu, Y.; Hu, Q.; Liao, B.; et al. Global Burden of Ischemic Heart Disease in Older Adult Populations Linked to Non-Optimal Temperatures: Past (1990–2021) and Future (2022–2050) Analysis. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1548215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Monteiro, M.F.S.; Oliveira-Machado, T.T.; Roniel, C.; Costa-Guimarães, G.G.P.; Oliveira-Machado, E.A.; Simeone, D.; Oliveira-Filho, A.B. First Evidence into the Association of Warming with Stroke and Myocardial Infarction Mortality in the Brazilian Amazon. Climate 2026, 14, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli14010006

Monteiro MFS, Oliveira-Machado TT, Roniel C, Costa-Guimarães GGP, Oliveira-Machado EA, Simeone D, Oliveira-Filho AB. First Evidence into the Association of Warming with Stroke and Myocardial Infarction Mortality in the Brazilian Amazon. Climate. 2026; 14(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli14010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleMonteiro, Marcele Farias Silva, Thainá Thamara Oliveira-Machado, Cícero Roniel, Gleyce Gabrielle Pereira Costa-Guimarães, Erick Augusto Oliveira-Machado, Diego Simeone, and Aldemir B. Oliveira-Filho. 2026. "First Evidence into the Association of Warming with Stroke and Myocardial Infarction Mortality in the Brazilian Amazon" Climate 14, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli14010006

APA StyleMonteiro, M. F. S., Oliveira-Machado, T. T., Roniel, C., Costa-Guimarães, G. G. P., Oliveira-Machado, E. A., Simeone, D., & Oliveira-Filho, A. B. (2026). First Evidence into the Association of Warming with Stroke and Myocardial Infarction Mortality in the Brazilian Amazon. Climate, 14(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli14010006