Abstract

Chromosome numbers, karyotypes, and genome sizes of 14 Iris L. (Iridaceae Juss.) species in Korea and their closely related taxon, Sisyrinchium rosulatum, are presented and analyzed in a phylogenetic framework. To date, understanding the chromosomal evolution of Korean irises has been hampered by their high chromosome numbers. Here, we report analyses of chromosome numbers and karyotypes obtained via classic Feulgen staining and genome sizes measured using flow cytometry in Korean irises. More than a two-fold variation in chromosome numbers (2n = 22 to 2n = 50) and over a three-fold genome size variation (2.39 pg to 7.86 pg/1 C) suggest the putative polyploid and/or dysploid origin of some taxa. Our study demonstrates that the patterns of genome size variation and chromosome number changes in Korean irises do not correlate with the phylogenetic relationships and could have been affected by different evolutionary processes involving polyploidy or dysploidy. This study presents the first comprehensive chromosomal and genome size data for Korean Iris species. Further studies involving molecular cytogenetic and phylogenomic analyses are needed to interpret the mechanisms involved in the origin of chromosomal variation in the Iris.

1. Introduction

Chromosomal changes play a major role in plant evolution and are thus important in diversification and speciation in angiosperms [1,2,3]. Variation of chromosome numbers, ploidy levels, and genome sizes have been frequently analyzed for a better understanding of evolutionary patterns and species relationships in plants [4,5,6,7]. The genome size values, in combination with data on chromosome numbers, allow ploidy levels to be inferred and can also provide insights into evolutionary relationships between closely related taxa in wild plant groups [7,8,9,10,11,12]. While the monocots are known to have the widest range of genome sizes (0.2–152.2 pg/1 C) among angiosperms [13,14,15], the known genome sizes in the family Iridaceae range from 0.5 pg/1 C in Hesperantha and Sisyrinchium species to 31.4 pg/1 C in Moraea taxa [15,16].

Among monocots, Iris is an excellent system in which to study the evolutionary patterns of chromosome number and genome size evolution because this group has an exceptionally high diversity of chromosome numbers (n = 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 24, 25, 27, 36, 54) [17] and genome sizes (1.05–28.2 pg/1 C) [15]. The genus Iris L. is perennial and comprises approximately 300 species worldwide, with the greatest number of endemic species occurring in the Mediterranean and Asia [18,19,20,21]. Generic and sub-generic classification of the genus Iris has been mainly based on morphological characters of flower organs and roots [22,23]. Subsequently, Wilson [24] recognized nine subgenera in the genus based on phylogenetic analysis of chloroplast sequence data: Iris, Crossiris Spach, Limniris, Lophiris (Tausch) C. A. Wilson, Nepalensis, Pardanthopsis (Hance) Baker, Siphonostylis (W. Schulze) C. A. Wilson, Xiphium, and Xyridon (Tausch) Spach.

Currently, 14 species from Iris (subgenus Limniris and Pardanthopsis) are recognized in Korea: Iris ensata Thunb., I. dichotoma Pall., I. domestica (L.) Goldblatt & Mabb., I. koreana Nakai, I. oxypetala Bunge, I. pseudacorus L., I. uniflora Pall. ex Link, I. laevigata Fisch., I. sanguinea Donn ex Hornem., I. setosa Pall. ex Link, I. odaesanensis Y.N. Lee, I. minutoaurea Makino, I. rossii Baker, I. ruthenica Ker Gawl. [24,25,26,27]. Species of the Korean irises usually have a narrow geographical distribution, and some are endemic (Iris koreana) or subendemic to Korea (Iris odaesanensis with a small/disjunct population in Jilin Province, China) [19,25]. While several species of Korean irises (I. dichotoma, I. laevigata, I. setosa, and I. ruthenica) are either endangered or threatened due to habitat loss caused by anthropogenic activities [25,28], Iris pseudacorus and Sisyrinchium rosulatum were introduced as horticultural elements and are now naturalized [25]. Despite an increasing importance of conservation status of the Korean irises, comprehensive systematic studies including morphological, phylogenetic, and cytological analyzes have not been performed in the group. Molecular phylogenetic analyses based on plastid and nuclear ribosomal DNA data have allowed for the inferring established relationship patterns of major lineages of among the Korean irises [27,29,30], although some sectional and species level relationships still remain unresolved.

Worldwide, chromosome numbers in the genus Iris have been reported for 168 taxa in validly published references (Table S1; Chromosome Counts Database, CCDB, ver. 145, http://ccdb.tau.ac.il/Angiosperms/Iridaceae/Iris/) [17]. Chromosome numbers and karyotypes have been reported for eight species of the Korean irises (I. ensata, I. dichotoma, I. koreana, I. oxypetala, I. pseudacorus, I. uniflora, I. setosa, I. sanguinea), but none of the studied plants were collected from natural populations [31]. Thus, detailed cytogenetic studies of Korean irises from natural populations are required. Analyses of chromosome numbers accompanied by genome size measurements allow for inferences of the incidence of polyploidy [5,7]. Although the genome size data of 44 Iris species have been conducted so far [15], the nuclear DNA amounts using flow cytometry for Korean irises are not available to date [15].

Thus, this study examines the patterns of chromosome number evolution, karyotypes, and genome size variation in a phylogenetic context in the Korean irises. The specific aims of this study are (1) to determine chromosome numbers and size variation as well as karyotypes structure all 14 Korean Iris species from multiple populations; (2) to examine patterns of genome size change in this group of taxa to address to the lack of the C-value data in the genus Iris; and (3) to interpret the patterns of evolution of cytological data within the available phylogenetic framework to better understand the genome evolution in Korean irises.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

A total of 76 individuals representing 36 populations of 14 species of Iris and one outgroup species Sisyrinchium rosulatum were collected from natural populations with few individuals used from other sources (cultivation; Table 1). The plants used in this study were transplanted in a glasshouse in Chungnam National University, Daejeon, Republic of Korea. All individuals were used for analyses of chromosome numbers, karyotypes and measurements of genome size (Table 1). Voucher specimens of the examined plants were deposited in CNUK (Chungnam National University Herbarium). Four Korean Iris species (I. dichotoma, I. laevigata, I. setosa, I. ruthenica) that are endangered and threatened were collected with special permissions from the Korean Government (collected under permits no. 2018-18, 2019-13, 2019-14, 2019-20, and 2019-30; Table 1). In order to avoid illegal removal to the endangered or vulnerable species, we refrain from providing details of the locality information (GPS coordinates) in this study.

Table 1.

Information on the plant material used for the karyotype and genome size analyses of Iris L. in Korea.

2.2. Chromosome Numbers and Karyotype Analysis

Fresh root tips were pretreated in 0.05% colchicine (Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, USA) solution at room temperature in the dark for 4.5 h. The sampled roots were fixed in ethanol:acetic acid (3:1) for two hours at room temperature and then stored at −20 °C. For karyotype and chromosome number analyses, meristematic root cells were used (Table 1). Prior to staining, the fixed roots were washed with tap water, and hydrolyzed in 5 N HCL at room temperature for 30 min. Subsequently, to perform Feulgen staining, the root tips were treated in Schiff′s reagent (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) in darkness for 1 h. Microscopic slides were prepared by squashing the meristematic tissue in 60% acetic acid. A minimum of three well spread chromosome plates were selected for the analyses [32]. The chromosomes were cut using Corel Photo-Paint 12.0 (Corel Company, Ottawa, Canada). For chromosomal measurements, MicroMeasure ver.3.3 program (https://micromeasure.software.informer.com/3.3/) [33] was used, and a minimum of three chromosomal spreads were measured with a comparable medium degree of chromosomal condensation (Table 2).

Table 2.

Karyotype analyses in the genus Iris L. and its related taxon Sisyrinchium rosulatum.

2.3. Genome Size Measurement by Flow Cytometry (FCM)

Genome sizes of 76 individuals of 14 Iris species and Sisyrinchium rosulatum were measured using flow cytometry with Solanum pseudocapsicum (1 C = 1.29 pg) [34] or Pisum sativum “Kleine Rheinländerin” (1 C = 4.42 pg) [35] as an internal standard. Approximately 20–30 mg of fresh leaves of each sample were chopped with an internal reference standard using Otto′s buffer I [36]. Subsequently, each sample was filtered using a nylon mesh, and incubated with RNase A in a water-bath at 37 °C for 30 min. The nuclei staining was conducted using propidium iodide, which contains Otto´s buffer II, and the sample was stored at 4 °C. A total of three measurements of DNA content were estimated for each sample using a flow cytometer (Partec, Münster, Germany). 1 C-values were calculated using estimation of linear fluorescence intensity of nuclei of the examined taxon and internal standard. The coefficient of variation (CV) of all estimations were mostly below 3% on average, and never exceeded 7% [7].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Chromosome Numbers and Karyotypes of Iris L.

Chromosome numbers for 74 individuals of 14 currently recognized the Korean Iris species and two individuals of Sisyrinchium rosulatum are provided in Table 1 and Figure 1 and Figure 2. The karyotype analyses of each species with detailed chromosome size measurements are presented in Table 2 and Figure 2. The previously reported chromosome number for the genus Iris varied from 2n = 14 (I. vorobievii) to 2n = 108 (I. versicolor) representing approximately a 7.7-fold difference (Table S1). To date, the chromosome numbers have been determined for approximately 168 taxa of ca. 300 currently recognized species in the genus Iris worldwide (c. 56%; Table S1) [17].

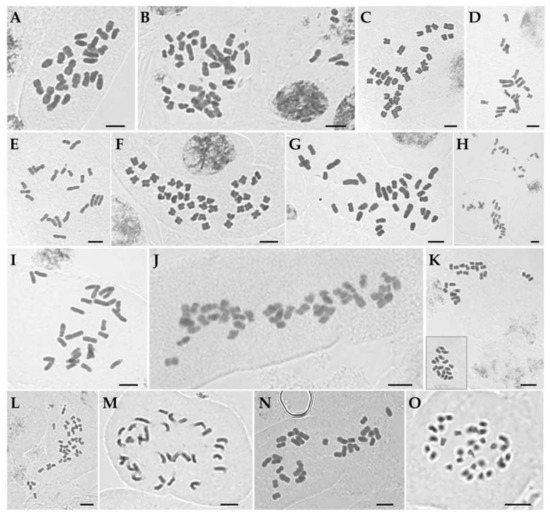

Figure 1.

Mitotic metaphase chromosomes of Korean irises. (A) Iris ensata (2n = 24). (B) I. koreana (2n = 50). (C) I. laevigata (2n = 32). (D) I. minutoaurea (2n = 22). (E) I. odaesanensis (2n = 28). (F) I. oxypetala (2n = 40). (G) I. pseudacorus (2n = 34). (H) I. rossii (2n = 32). (I) I. sanguinea (2n = 28). (J) I. setosa (2n = 38). (K) I. ruthenica (2n = 42). (L) I. uniflora (2n = 42). (M) I. dichotoma (2n = 32). (N) I. domestica (2n = 32). (O) Sisyrinchium rosulatum (2n = 32). Inset in (K) shows same chromosome group of a single cell which were lying at some distance using high magnification objectives. Scale bar = 5 µm.

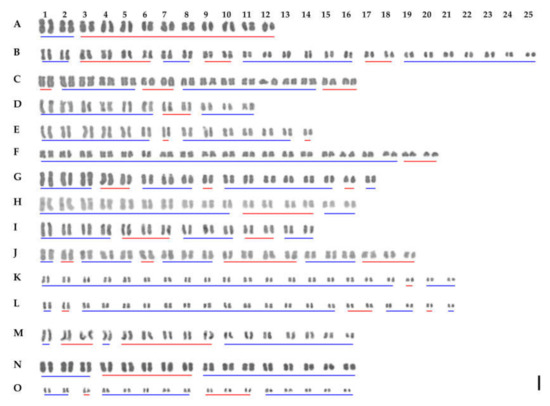

Figure 2.

Karyotypes of the Korean irises. (A) Iris ensata (2n = 24). (B) I. koreana (2n = 50). (C) I. laevigata (2n = 32). (D) I. minutoaurea (2n = 22). (E) I. odaesanensis (2n = 28). (F) I. oxypetala (2n = 40). (G) I. pseudacorus (2n = 34). (H) I. rossii (2n = 32). (I) I. sanguinea (2n = 28). (J) I. setosa (2n = 38). (K) I. ruthenica (2n = 42). (L) I. uniflora (2n = 42). (M) I. dichotoma (2n = 32). (N) I. domestica (2n = 32). (O) Sisyrinchium rosulatum (2n = 32). Blue and red bars indicate metacentric and submetacentric chromosomes, respectively. Scale bar: 5 µm.

3.1.1. Iris L. Subgenus Limniris Spach Section Limniris Spach

The chromosome numbers in sect. Limniris ranged from 2n = 22 in I. minutoaurea to 2n = 50 in I. koreana (Table 1) confirming earlier studies [17]. I. odaesanensis (2n = 28) is reported here for the first time. Both analyzed plants of I. ensata had 2n = 24 (Figure 1A), AsI (asymmetry index) of 66.7% and karyotype formula of 2n = 4 m + 20 sm (Figure 2A) with Haploid Karyotype length (HKL) of 82.5 ± 1.7 µm. The two individuals of I. koreana had 2n = 50 (Figure 1B), with its AsI of 61.9% and the karyotype formula of 34 m + 16 sm (Figure 2B) and HKL of 141.7 ± 9.9 µm. The four plants of I. laevigata had 2n = 32 (Figure 1C). The species had AsI of 61.9%, karyotype formula of 2n = 22 m + 10 sm (Figure 2C) and HKL of 81.8 ± 1.7 µm. All 11 analyzed plants of I. minutoaurea had 2n = 22 (Figure 1D) and AsI of 58.3%. The karyotype formula was 18 m + 4 sm (Figure 2D) with HKL of 75.8 ± 2.4 µm. All eight plants of I. odaesanensis had 2n = 28 (Figure 1E) with AsI of 59.5%, karyotype formula of 2n = 24 m + 4 sm (Figure 2E) and HKL of 86.3 ± 2.4 µm. All four plants of I. oxypetala had 2n = 40 (Figure 2F), AsI of 59.1% and karyotype formula of 2n = 36 m + 4 sm (Figure 2F). HKL of this species was 86.4 ± 3.8 µm. All seven plants of I. pseudacorus had 2n = 34 (Figure 1G), AsI was 62.0% and the karyotype formula was 26 m + 8 sm (Figure 2G) with HKL of 107.1 ± 4.2 µm. All nine plants of I. rossii had 2n = 32 (Figure 1H). This species had AsI of 60.9%, karyotype formula of 2n = 24 m + 8 sm (Figure 2H) and HKL of 100.5 ± 3.0 µm. All seven plants of I. sanguinea possessed 2n = 28 (Figure 1I), AsI of 62.5%, and the karyotype formula of 18 m + 10 sm (Figure 2I) with HKL of 87.2 ± 2.8 µm. All five plants of I. setosa had 2n = 38 (Figure 1J), in agreement with previous reports [17] except for the one study reporting 2n = 40 for this species [31]. This deviating count might have potentially referred to another taxon (either a species or a variety), but it is difficult to verify due to unknown origin of the examined sample (e.g., cultivated material) [31]. Most previous studies used cultivated material. Thus, any discrepancies that might exist between different reports might have been affected by domestication and associated potential hybridization [31], as also suggested for Iberian irises [37]. Iris setosa had AsI of 61.6% and karyotype formula of 2n = 20 m + 18 sm (Figure 2J) with HKL of 122.9 ± 6.9 µm.

3.1.2. Iris L. Subgenus Limniris Spach Section Ioniris Spach

All nine plants of I. ruthenica had 2n = 42 (Figure 1K), in agreement with previous reports (Table S1) [17]. This species had AsI of 58.0% and karyotype formula of 2n = 40 m + 2 sm (Figure 2K) with HKL of 78.3 ± 4.3 µm. The three analyzed plants of I. uniflora had 2n = 42 (Figure 1L) confirming previous reports (Table S1) [17]. Its AsI was 58.3% and karyotype formula of 2n = 34 m + 8 sm (Figure 2L) with HKL of 61.9 ± 1.9 µm.

3.1.3. Iris L. Subgenus Pardanthopis (Hance) Baker

All four examined individuals of I. dichotoma had 2n = 32 (Figure 1M). This number was consistent with previous records for this species from Russian and Chinese populations [17], except for the study of Kim et al. [31], in which analyzed cultivated material was reported to have 2n = 34. This species had AsI of 61.9% and karyotype formula of 2n = 18 m + 14 sm (Figure 2M) with HKL of 97.0 ± 4.4 µm. Iris domestica had 2n = 32 (Figure 1N), which was in agreement with previous reports (Table S1) [17]. Its AsI was 59.7% and karyotype formula was 2n = 22 m + 10 sm (Figure 2N) with HKL of 92.8 ± 4.2 µm.

3.1.4. Sisyrinchium rosulatum E.P.Bicknell.

3.2. Genome Size Variation in Iris L.

DNA content analyses using an internal standard revealed clear and well-defined peaks for all samples with the coefficients of variation (CV) for the internal standard and sample peaks ranging from 1.03% to 5.40% (mean ± S.D. = 2.24 ± 0.80) and from 1.23% to 6.50% (mean ± S.D. = 2.87 ± 1.06), respectively.

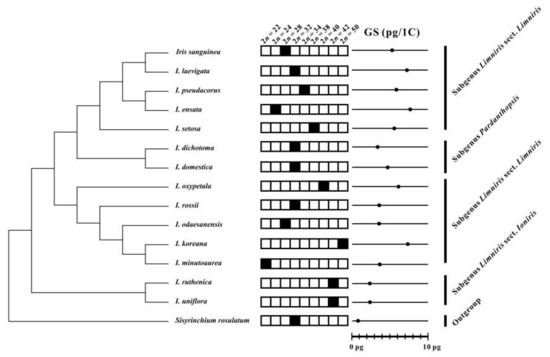

Genome sizes for all Korean irises, except for Iris pseudacorus, are reported here for the first time (Table 1; Figure 3). The analysis revealed a 3.29-fold variation in nuclear DNA content among the analyzed taxa, with genome sizes ranging from 2.39 pg/1 C in Iris ruthenica to 7.86 pg/1 C in I. ensata. To date, the 1 C-values of 44 Iris species have been reported ranging from 1.05 pg/1 C in I. versicolor to 28.20 pg/1 C in I. histrio [15]. Genome size of Iris pseudacorus reported earlier (1 C = 5.67 pg) [38] is very similar with the current data (5.77–6.02 pg/1 C; Table 1). The outgroup species Sisyrinchium rosulatum had 0.90 pg/1 C (Table 1; Figure 3). The 1 C-values in Korean irises vary significantly among species, but are constant within populations and species, as previously observed in closely related species within a genus [10,39]. This suggests that ploidy levels in the populations of Korean irises examined in this study are at least partially stable within species. The new data presented here will allow for better understanding of the dynamics and patterns of chromosomal evolutionary changes in the genus Iris [15].

Figure 3.

Chromosome numbers (2n; solid black squares) and genome sizes (GS) of Korean irises mapped on the phylogenetic tree based on nrITS sequences modified and simplified from Sim et al. [27]. The mean 1 C-values per species are indicated with solid dots.

3.3. Evolution of Chromosome Numbers and Genome Sizes

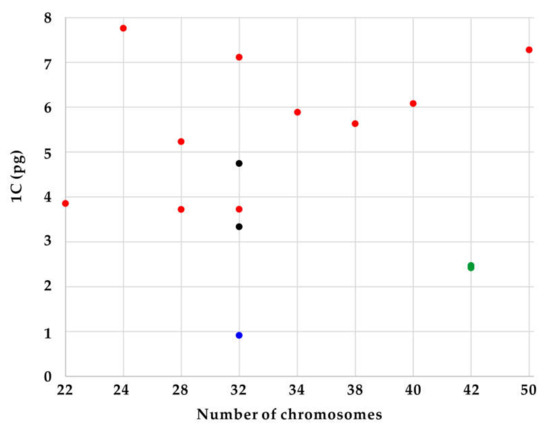

The newly obtained chromosome numbers and genome sizes were mapped on nrITS phylogeny of Korean irises (modified from [27]). The data revealed that there is no correlation between chromosome numbers and genome sizes among the phylogenetic lineages of the analyzed Korean Iris species. As an example, Iris ensata with low chromosome number of 2n = 24 has the highest 1 C-value (7.76 pg/1 C) whereas its close relative I. setosa has 2n = 38, but 1.4-fold lower genome size (Figure 4). It suggests that dysploidy and polyploidy are not solely responsible for the observed variation of genome sizes and chromosome numbers, but also other processes, like independent accumulation or reduction of repetitive DNAs amount (e.g., satellite DNAs and/or transposable elements) play an important role, as previously reported in other plant groups [7,40,41,42,43].

Figure 4.

Distribution of genome size data [1 C (pg)] in relation to chromosome number (2n). Colors represent subgenus Limniris section Limniris (red), section Ioniris (green), subgenus Pardanthopsis (black), and Sisyrinchium rosulatum (blue).

Other lineages within the genus Iris might be more stable evolutionarily. Both Iris ruthenica and I. uniflora (subgenus Limniris section Ioniris) have the same chromosome numbers of 2n = 42 and similar genome sizes (ca. 2.4 pg/1 C). Thus, the current cytogenetic data support the monophyly of this section, as proposed based on phylogenetic analyses of plastid markers [44,45,46], but also suggest low levels of genome dynamics accompanying their evolution. Iris dichotoma and I. domestica of the subgenus Pardanthopsis have also been recovered in monophyletic clade in ITS- and plastid-based phylogenetic analyses [46,47]. However, although they share the same chromosome numbers of 2n = 32, they differ nearly a 1.5-fold in genome sizes. Such variation of genome sizes suggests independent accumulation/loss of repetitive DNAs in the absence of numerical chromosome changes as reported also in other monocot genera [7,40].

In contrast, allopolyploidy can be hypothesized for the origin of Iris koreana (2n = 50) from closely related I. minutoaurea (2n = 22) and I. odaesanensis (2n = 28) [30]. It is also supported from the additive genome size of this taxon. Allopolyploidy has been implied to be an important process in the early diversification of the whole family of Iridaceae [48,49]. Thus, further data employing GISH (genomic in situ hybridization) will allow testing the allopolyploid origin of this and other species in the section Limniris.

The subgenus Limniris section Limniris has previously been shown to be polyphyletic [27,30,44,45,46]. This study shows that there is also quite wide variation of chromosome numbers and genome sizes within the newly identified polyphyletic clades of this subgenus (Figure 3 and Figure 4). It suggests that the genome size and chromosome number evolved rather dynamically in those evolutionary lineages, as indeed also observed in other monocot genera [11,50,51].

4. Conclusions

The present study provides the first comprehensive analyses of chromosome numbers, karyotype features and genome size variation of Korean irises from natural populations. Despite the large variation of chromosome numbers (n = 11, 12, 14, 16, 17, 19, 20, 21, 25), some variation of genome sizes (2.42–7.76 pg/1 C) has been demonstrated. This variation is only partially phylogenetically structured. Numerical chromosomal changes, both polyploidy and dysploidy, seem to be accompanied to a different degree by the likely independent changes in the amounts of repetitive DNAs in different phylogenetic lineages. Various combinations of these processes acting on the genomes of closely related species create complex patterns of genome size and chromosome number variation observed in Korean irises. Further analyses are needed to elucidate how these processes affect the evolution of the genomes of individual species, not only of the Iris species in Korea but ideally in a broader phylogenetic context of whole subgenera/sections.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2223-7747/9/10/1284/s1, Table S1. Chromosome counts from the published data according to Rice et al. [17].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.C. and T.-S.J.; Collection and identification of plant material, B.C., S.S., H.-H.M., and T.-S.J.; Methodology, B.C., E.M.T., and T.-S.J.; Formal analysis, B.C., H.W.-S., E.M.T., and T.-S.J.; Writing—original draft preparation, B.C., H.W.-S., E.M.T., and T.-S.J.; Writing—review and editing, B.C., H.W.-S., and T.-S.J.; Visualization, B.C. and T.-S.J.; Supervision, T.-S.J.; Project administration, T.-S.J.; Funding acquisition, T.-S.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), grant number NRF-2018R1C1B6003170 to T.-S. Jang. Open access funding provided by grants from the Korea National Park Research Institute (NPRI 2019-18).

Acknowledgments

We thank Sun-Yu Kim (Nakdonggang National Institute of Biological Resources), Sungyu Yang and Jun-Ho Song (Korea Institute of Oriental Medicine), Chang-Ho Choi (Chollipo Arboretum), Il Noh (National Park Services), Seon-Wook Lee (National Park Services), Yusun Kweon, Yeongmun Choi, and all the lab members at CNUK (Herbarium of Chungnam National University) for their help in collecting materials for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lysak, M.A.; Berr, A.; Pecinka, A.; Schmidt, R.; McBreen, K.; Schuber, I. Mechanisms of chromosome number reduction in Arabidopsis thaliana and related Brassicaceae species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 5224–5229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schubert, I. Chromosome evolution. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2007, 10, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss-Schneeweiss, H.; Schneeweiss, G.M. Karyotype diversity and evolutionary trends in angiosperms. In Plant Genome Diversity 2: Physical Structure, Behaviour and Evolution of Plant Genomes; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 2013; Volume 2, pp. 209–230. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, M.D.; Leitch, I.J. Nuclear DNA amounts in angiosperms: Targets, trends and tomorrow. Ann. Bot. 2011, 107, 467–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss-Schneeweiss, H.; Blöch, C.; Turner, B.; Villaseñor, J.L.; Stuessy, T.F.; Schneeweiss, G.M. The promiscuous and the chaste: Frequent allopolyploid speciation and its genomic consequences in American Daisies (Melampodium sect. Melampodium; Asteraceae). Evolution 2012, 66, 211–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, T.S.; McCann, J.; Parker, J.S.; Takayama, K.; Hong, S.P.; Schneeweiss, G.M.; Weiss-Schneeweiss, H. rDNA loci evolution in the genus Glechoma (Lamiaceae). PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0167177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, T.S.; Parker, J.S.; Emadzade, K.; Temsch, E.M.; Leitch, A.R.; Weiss-Schneeweiss, H. Multiple origins and nested cycles of hybridization result in high tetraploid diversity in the monocot Prospero. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Róis, A.S.; Castro, S.; Loureiro, J.; Sádio, F.; Rhazi, L.; Guara-Requena, M.; Caperta, A.D. Genome sizes and phylogenetic relationships suggest recent divergence of closely related species of the Limonium vulgare complex (Plumbaginaceae). Plant Syst. Evol. 2018, 304, 955–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassone, A.B.; López, A.; Hojsgaard, D.H.; Giussani, L.M. A novel indicator of karyotype evolution in the tribe Leucocoryneae (Allioideae, Amaryllidaceae). J. Plant Res. 2018, 131, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, B.; Yang, S.; Song, J.H.; Jang, T.S. Karyotype and genome size variation in Ajuga L. (Ajugoideae-Lamiaceae). Nord. J. Bot. 2019, 37, e02337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, G.A.S.; Filho, J.R.M.; Vasconcelos, S.; Gitaí, J.; Campos, J.S.; Viccini, L.F.; Zizka, G.; Leme, E.M.C.; Brasileiro-Vidal, A.C.; Benko-Iseppon, A.M.B. Genome size evolution and chromosome numbers of species of the cryptanthoid complex (Bromelioideae, Bromeliaceae) in a phylogenetic framework. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2020, 192, 887–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tlili, A.; Gouja, H.; Vallés, J.; Garnatje, T.; Buhagiar, J.; Neffati, M. Chromosome number and genome size in Atriplex mollis from southern Tunisia and Atriplex lanfrancoi from Malta (Amaranthaceae). Plant Syst. Evol. 2020, 306, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitch, I.J.; Leitch, A.R. Genome size diversity and evolution in land plants. In Plant Genome Diversity 2: Physical Structure, Behaviour and Evolution of Plant Genomes; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 2013; Volume 2, pp. 307–322. [Google Scholar]

- Schubert, I.; Vu, G.T.H. Genome stability and evolution: Attempting a holistic view. Trends Plant Sci. 2016, 21, 749–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellicer, J.; Leitch, I.J. The plant DNA C-values database (release 7.1): An updated online repository of plant genome size data for comparative studies. New Phytol. 2020, 226, 301–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldblatt, P.; Walbot, V.; Zimmer, E. Estimation of genome size (C-value) in Iridaceae by cytophotometry. Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 1984, 71, 176–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, A.; Glick, L.; Abadi, S.; Einhorn, M.; Kopelman, N.M.; Salman-Minkov, A.; Mayzel, J.; Chay, O.; Mayrose, I. The chromosome counts database (CCDB): A community resource of plant chromosome numbers. New Phytol. 2015, 206, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldblatt, P.; Manning, J.C.; Rudall, P.J. Iridaceae. In The Families and Genera of Vascular Plants. Vol. 3, Flowering Plants. Monocotyledons: Lilianae (Except Orchidaceae); Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1998; pp. 295–333. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.T.; Noltie, H.J.; Mathew, B. Iridaceae. In Flora of China; Missouri Botanical Garden Press: St. Louis, MA, USA, 2000; Volume 24, pp. 297–313. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, C.A. Patterns of evolution in characters that define Iris subgenera and sections. Aliso 2006, 22, 425–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Wilson, C.A. Molecular phylogeny of crested Iris based on five plastid markers (Iridaceae). Syst. Bot. 2013, 38, 987–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodionenko, G.I. The Genus Iris; Academy of Science USSR: Moscow, Russia, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Mathew, B. The Iris; Batsford: London, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, C.A. Subgeneric classification in Iris re-examined using chloroplast sequence data. Taxon 2011, 60, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, J.K. Iridaceae Juss. In The Genera of Vascular Plants of Korea; Academy Publ. Co.: Seoul, Korea, 2007; pp. 1326–1331. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, T.B. Colored Flora of Korea; Hyangmunsa: Seoul, Korea, 2003; Volume II. [Google Scholar]

- Sim, J.K.; Park, H.D.; Park, S.J. Phylogenetic study of Korean Iris (Iridaceae) based on nrDNA ITS sequences. Korean J. Plant Taxon. 2002, 32, 33–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.; Kim, Y.D.; Lim, Y.S.; Kim, Y.I. Endangered vascular plants in the republic of Korea. In Korean Red List of Threatened Species, 2nd ed.; National Institute of Biological Resources: In-Cheon, Korea, 2014; pp. 137–194. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.J.; Park, S.J. A phylogenetic study of Korean Iris L. based on plastid DNA (psbA-trnH, trnL-F) sequences. Korean J. Plant Taxon. 2013, 43, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, O.; Son, S.W.; Suh, G.U.; Park, S.J. Natural hybridization of Iris species in Mt. Palgong-san, Korea. Korean J. Plant Taxon. 2015, 45, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.H.; Park, Y.W.; Yoon, P.S.; Choi, H.W.; Bang, J.W. Karyotype analysis of eight Korean native species in the genus Iris. Korean J. Medicinal Crop Sci. 2004, 12, 401–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, B.; Kim, S.Y.; Jang, T.S. Micromorphological and cytological comparisons between Youngia japonica and Y. longiflora using light and scanning electron microscopy. Microsc. Res. Techniq. 2020, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MicroMeasure 3.3 Program. Available online: https://micromeasure.software.informer.com/3.3 (accessed on 1 August 2020).

- Temsch, E.M.; Greilhuber, J.; Krisai, R. Genome size in liverworts. Preslia 2010, 82, 63–80. [Google Scholar]

- Greilhuber, J.; Ebert, I. Genome size variation in Pisum sativum. Genome 1994, 37, 646–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, F.; Oldiges, H.; Gohde, W.; Jain, V.K. Flow cytometric measurement of nuclear DNA content variations as a potential in vivo mutagenicity test. Cytometry 1981, 2, 189–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, J.; Vargas, P.; Luceño, M.; Cuadrado, Á. Evolution of Iris subgenus Xiphium based on chromosome numbers, FISH of nrDNA (5S, 45S) and trnL-trnF sequence analysis. Plant Syst. Evol. 2010, 289, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siljak-Yakovlev, S.; Pustahija, F.; Šolić, E.M.; Bogunić, F.; Muratović, E.; Bašić, N.; Catrice, O.; Brown, S.C. Towards a genome size and chromosome number database of Balkan Flora: C-values in 343 taxa with novel values for 242. Adv. Sci. Lett. 2010, 3, 190–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samad, N.A.; Dagher-Kharrat, M.B.; Hidalgo, O.; Zein, R.E.; Douaihy, B.; Siljak-Yakovlev, S. Unlocking the karyological and cytogenetic diversity of Iris from Lebanon: Oncocyclus section shows a distinctive profile and relative stasis during its continental radiation. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0160816. [Google Scholar]

- Emadzade, K.; Jang, T.S.; Macas, J.; Kovařík, A.; Novák, P.; Parker, J.; Weiss-Schneeweiss, H. Differential amplification of satellite PaB6 in chromosomally hypervariable Prospero autumnale complex (Hyacinthaceae). Ann. Bot. 2014, 114, 1597–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss-Schneeweiss, H.; Leitch, A.R.; McCann, J.; Jang, T.S.; Macas, J. Employing next generation sequencing to explore the repeat landscape of the plant genome. In Next Generation Sequencing in Plant Systematics. Regnum Vegetabile 157; Koeltz Scientific Books: Königstein, Germnay, 2015; Volume 158, pp. 155–179. [Google Scholar]

- Macas, J.; Novák, P.; Pellicer, J.; Čížková, J.; Koblížková, A.; Neumann, P.; Fuková, I.; Doležel, J.; Kelly, L.J.; Leitch, I.J. In depth characterization of repetitive DNA in 23 plant genomes reveals sources of genome size variation in the legume tribe Fabeae. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0143424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCann, J.; Jang, T.S.; Macas, J.; Schneeweiss, G.M.; Matzke, N.J.; Novák, P.; Stuessy, T.F.; Villaseñor, J.L.; Weiss-Schneeweiss, H. Dating the species network: Allopolyploidy and repetitive DNA evolution in American Daisies (Melampodium sect. Melampodium, Asteraceae). Syst. Biol. 2018, 67, 1010–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makarevitch, I.; Golovnina, K.; Scherbik, S.; Blinov, A. Phylogenetic relationships of the Siberian Iris species inferred from noncoding chloroplast DNA sequences. Int. J. Plant Sci. 2003, 164, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, C.A. Phylogenetic relationships among the recognized series in Iris section Limniris. Syst. Bot. 2009, 34, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.L.; Huang, Z.; Liao, J.Q.; Song, H.X.; Luo, X.M.; Gao, S.P.; Lei, T.; Jiang, M.Y.; Jia, Y.; Chen, Q.B.; et al. Phylogenetic analysis of Iris L. from China on chloroplast trnL-F sequences. Biologia 2018, 73, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, C.A. Phylogeny of Iris based on chloroplast matK gene and trnK intron sequence data. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2004, 33, 402–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldblatt, P.; Takei, M. Chromosome cytology of Iridaceae—Patterns of variation, determination of ancestral base numbers, and modes of karyotype change. Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 1997, 84, 285–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, K.Y.; Matyasek, R.; Kovařík, A.; Leitch, A.R. Parental origin and genome evolution in the allopolyploids Iris versicolor. Ann. Bot. 2007, 100, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jersáková, J.; Trávníček, P.; Kubátová, B.; Krejčíková, J.; Urfus, T.; Liu, Z.J.; Lamb, A.; Ponert, J.; Schulte, K.; Curn, V.; et al. Genome size variation in Orchidaceae subfamily Apostasioideae: Filling the phylogenetic gap. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2013, 172, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šmarda, P.; Bureš, P.; Horová, L.; Leitch, I.J.; Mucina, L.; Pacini, E.; Tichý, L.; Grulich, V.; Rotreklová, O. Ecological and evolutionary significance of genomic GC content diversity in monocots. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 4096–4102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).