Abstract

Mosquito-borne diseases are a large problem in Vietnam as elsewhere. Due to environmental concerns regarding the use of synthetic insecticides as well as developing insecticidal resistance, there is a need for environmentally-benign alternative mosquito control agents. In addition, resistance of pathogenic microorganisms to antibiotics is an increasing problem. As part of a program to identify essential oils as alternative larvicidal and antimicrobial agents, the leaf, stem, and rhizome essential oils of several Zingiber species, obtained from wild-growing specimens in northern Vietnam, were acquired by hydrodistillation and investigated using gas chromatography. The mosquito larvicidal activities of the essential oils were assessed against Culex quinquefasciatus, Aedes albopictus, and Ae. aegypti, and for antibacterial activity against a selection of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, and for activity against Candida albicans. Zingiber essential oils rich in α-pinene and β-pinene showed the best larvicidal activity. Zingiber nudicarpum rhizome essential oil showed excellent antibacterial activity against Enterococcus faecalis, Staphylococcus aureus, and Bacillus cereus, with minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) of 2, 8, and 1 μg/mL, respectively. However, the major components, α-pinene and β-pinene, cannot explain the antibacterial activities obtained.

Keywords:

ginger; Aedes aegypti; Aedes albopictus; Culex quinquefasciatus; antibacterial; antifungal 1. Introduction

Vietnam is located in the tropics of Southeast Asia, and several mosquito-borne diseases are endemic, including Japanese encephalitis [1], dengue fever [2], and Zika [3]. Culex species are considered to be important vectors of Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV), including Culex quinquefasciatus Say (Diptera: Culicidae) [4], but other mosquito genera may also serve as competent vectors of the virus [5,6]. Dengue fever is hyperendemic to Vietnam with all four serotypes of the virus in circulation, resulting in periodic acute epidemics of both dengue fever and dengue hemorrhagic fever [7,8]. Aedes aegypti (L.) and Aedes albopictus (Skuse) (Diptera: Culicidae) mosquitoes are the principal vectors of dengue fever virus (DFV) in Vietnam [9]. Zika virus (ZIKV) first appeared in Vietnam in 2016, where the primary transmission vector is Aedes mosquitoes [10]. Exacerbating this problem is the increasing insecticide resistance in Aedes [11,12,13] and Culex mosquitoes [14,15].

As observed throughout the world, antimicrobial resistance is an increasing problem in Vietnam [16]. Particularly noteworthy are antibiotic-resistant organisms in hospital settings, including Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa [17], Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae [18], Escherichia coli, and Staphylococcus aureus [19].

Zingiber Mill. is a species-rich genus within the subfamily Zingireroideae of Zingiberaceae, which are native to Southeast Asia [20]. The Plant List currently has 146 accepted names for Zingiber species [21]. The phytochemistry, particularly essential oil chemistry, and the pharmacology of Zingiber have been reviewed [22]. Currently, at least thirty-six species of Zingiber have been reported in Vietnam [23,24,25].

There is a need to discover new and alternative insect-control agents and antimicrobial agents. In this work, essential oils from seven species of Zingiber growing in Vietnam were collected and analyzed by gas chromatographic methods. Six species were screened for mosquito larvicidal activity and antibacterial and antifungal activity.

Zingiber cornubracteatum Triboun & K. Larsen was first recorded in northern Thailand (Mae Hong Son) [26], but has since been collected in northern Vietnam (Thanh Hoa, Nghe An, and Quang Binh provinces) [25]. There have been no reports on the phytochemistry of this plant. Zingiber neotruncatum T.L. Wu, K. Larsen & Turland has been recorded from southern and western Yunnan province, China [27] and Nghệ An province, Vietnam [28]. There have been no previous reports on the essential oil of this species. Zingiber nitens M.F. Newman is known from Bolikhamsai Province, Laos [29], and Nghệ An Province, Vietnam [30]. The essential oil composition of Z. nitens from Vietnam has been previously published [31]. Zingiber nudicarpum D. Fang has been recorded in Guangxi Province, China [27], Laos [32], and Vietnam [33]. The essential oil composition of Z. nudicarpum from Vietnam has been previously published [34]. Zingiber ottensii Valeton is native to Southeast Asia, including Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia, Laos, Myanmar, and Vietnam [35,36]. Essential oil compositions of Z. ottensii have been reported from Malaysia [37,38], Thailand [39,40], and Indonesia [41]. Zingiber recurvatum S.Q. Tong & Y.M. Xia has been recorded in southern Yunnan Province, China [42], northern Laos [32], and Vietnam [43,44]. There are apparently no reports on the volatile phytochemistry of this plant. Zingiber vuquangensis Lý N.S., Lê T.H., Trịnh T.H., Nguyễn V.H., Đỗ N.Đ. is a new species, only recently recorded in Vietnam [45]. The essential oil composition of Z. vuquangensis has been reported [46].

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Essential Oil Compositions

The Zingiber plant tissues (leaves, stems, or rhizomes) were collected from north-central Vietnam and the plant tissues subjected to hydrodistillation to obtain the respective essential oils (Table 1, Figure 1). Gas chromatographic–mass spectral (GC-MS) and gas chromatographic–flame ionization detection (GC-FID) were used to analyze the essential oil compositions, which are compiled in Table 2.

Table 1.

Plant collection and hydrodistillation details of Zingiber species from north-central Vietnam.

Figure 1.

Distribution map of Zingiber species from the north-central Vietnam. (A): Zingiber cornubraceatum Triboun & K. Larsen (red squares); Z. neotruncatum Triboun & K. Larsen (blue triangle), Z. nitens M.F. Newman (orange circle), Z. nudicarpum D.Fang (green stars). (B): Zingiber ottensii Valeton (red square), Z. recurvatum S.Q. Tong & Y.M. Xia (blue circle), Z. vuquangensis Ly N.S., Le T.H., Trinh T.H., Nguyen V.H., Do N.D. (orange star).

Table 2.

Chemical compositions of essential oils of Zingiber species from north-central Vietnam.

The rhizome essential oils of Z. cornubracteatum were predominantly composed of monoterpene hydrocarbons and oxygenated monoterpenoids. The major components were α-pinene (8.2–14.5%), β-pinene (8.8–33.1%), limonene (1.0–5.1%), 1,8-cineole (2.5–10.4%), and linalool (0.4–31.0%). Both α-pinene and β-pinene were major components in the leaf essential oils of Z. cornubracteatum (2.7–10.1% and 18.8–67.3%, respectively). However, sesquiterpene hydrocarbons, including (E)-caryophyllene (1.8–13.9%), germacrene D (0.7–13.7%), bicyclogermacrene (2.7–18.9%), as well as the sesquiterpenoid (E)-nerolidol (0.9–23.0%), were also abundant in the leaf essential oils.

The leaf essential oils of Z. nudicarpum were also rich in α-pinene (5.0–10.9%), β-pinene (0.7–34.0%), in addition to the sesquiterpene hydrocarbons (E)-caryophyllene (6.4–24.3%), α-humulene (2.1–6.4%), germacrene D (0.6–6.5%), and bicyclogermacrene (3.3–16.1%). The leaf essential oil of Z. nudicarpum from Pù Hoạt Nature Reserve previously reported also showed α- and β-pinenes (2.4% and 11.7%, respectively) [34]. Important differences are apparent between the previously reported essential oil and those from the present study. The previous report found no (E)-caryophyllene or germacrene D, but large concentrations of cedrol (14.8%) and β-eudesmol (13.8%), which were not observed in this current study. Interestingly, the stem essential oils of Z. nudicarpum showed wide variation in monoterpene hydrocarbon concentrations, with the sample from Pù Hoạt Nature Reserve showing only low concentrations of monoterpene hydrocarbons compared to samples from Nam Đông or Bạch Mã National Park. For example, the concentrations were: α-pinene (0.0, 10.6, 6.1%), β-pinene (0.5, 9.0, 5.6%), p-cymene (0.0, 6.0, 0.1%), and limonene (0.0, 2.1, 6.0%). The Pù Hoạt stem essential oil had a high concentration of (E)-caryophyllene (52.6%). The rhizome essential oil from Pù Hoạt Nature Reserve had α-pinene (18.7%) and β-pinene (58.3%) as dominant constituents, and is qualitatively similar to a sample earlier reported from that collection site [34]. α-Pinene and β-pinene concentrations were lower in the rhizome essential oil sample from Nam Đông (4.0% and 9.8%, respectively).

The most abundant constituents in the rhizome essential oil of Z. neotruncatum were perillene (51.3%), neral (12.3%), and geranial (17.0%). Perillene is a major component of Perilla frutescens (perillene chemotype) [47] and Elsholtzia polystachya (perillene chemotype) [48], but has been found in Zingiber essential oils in small concentrations, e.g., Z. officinale rhizome oil (0.1–0.6%) [40,49,50] and Z. zerumbet leaf oil (1.2%) [51]. Neral and geranial are also major components of Z. officinale rhizome oil [49,50].

Camphene (40.4%) dominated the rhizome essential oil composition of Z. nitens, followed by bornyl acetate (14.5%), (E)-β-ocimene (12.7%), and α-pinene (10.5%). In comparison, the rhizome essential oil of Z. nitens from Pù Mát National Park previously reported contained bornyl acetate (11.8%), (E)-β-ocimene (1.1%), and α-pinene (7.3%), along with β-pinene (21.0%), and δ-elemene (12.8%) [31]. In contrast, the leaf essential oil of Z. nitens was composed largely of α-zingiberene (17.4%), α-pinene (11.2%), β-sesquiphellandrene (10.1%), (E)-nerolidol (10.0%), zingiberenol (7.2%), β-pinene (6.0%), and ar-curcumene (5.2%). The previously reported Z. nitens leaf essential oil was devoid of α-zingiberene, β-sesquiphellandrene, zingiberenol, and ar-curcumene, but contained large concentrations of δ-elemene (17.0%) and ledol (8.1%), which were not observed in the present sample. In addition, concentrations of trans-β-elemene, germacrene D, and bicyclogermacrene were high in the previous report (8.8%, 8.2%, and 8.3%, respectively), but low in the present sample (0.8%, 0.7%, and 1.5%, respectively). The variations in chemical constituents can likely be attributed to the different geographical collection sites as well as climatic factors. The Pù Mát sample was collected in May, 2014 (beginning of the rainy season), while the sample from Vũ Quang National Park (this work) was collected in September, 2018 (height of the rainy season).

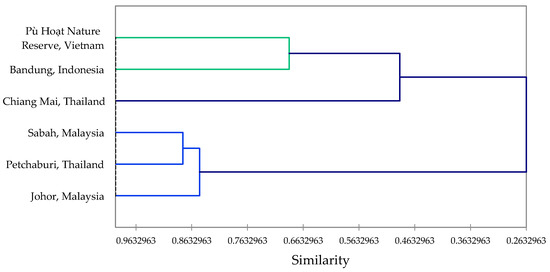

The essential oil from the leaves of Z. ottensii had abundant sesquiterpene hydrocarbons, including (E)-caryophyllene (28.0%) and trans-β-elemene (17.0%), along with the monoterpene β-pinene (17.1%). (E)-Caryophyllene (19.6%) and trans-β-elemene (12.3%) were also found to be key constituents in Z. ottensii leaf oil from Bandung, West Java, Indonesia [41]. However, zerumbone was a major component (11.4%) in the leaf oil from Indonesia, but was not detected in the sample from Vietnam. The rhizome essential oil from Vietnam had monoterpenes as the major components, such as sabinene (21.6%), β-pinene (11.7%), γ-terpinene (5.5%), and terpinen-4-ol (17.1%), in addition to the sesquiterpenoid zerumbone (12.5%). Rhizome essential oils of Z. ottensii from other geographical locations have been reported; the major components are presented in Table 3. A hierarchical cluster analysis using the eight major constituents (Figure 2) reveals the similarities between these rhizome essential oils. The clusters are largely defined by the zerumbone concentrations.

Table 3.

Comparison of the major components of Zingiber ottensii rhizome essential oils from different geographical locations.

Figure 2.

Dendrogram obtained from agglomerative hierarchical cluster analysis of the rhizome essential oils from Zingiber ottensii from different geographical locations.

The monoterpenes α-pinene (16.3%) and β-pinene (71.6%) dominated the leaf essential oil composition of Z. recurvatum. The major components in the rhizome essential oil of Z. recurvatum were (E)-caryophyllene (11.3%), bornyl acetate (10.4%), α-humulene (6.9%), and bicyclogermacrene (5.1%).

Zingiber vuquangensis leaf and rhizome essential oils were both rich in α-pinene (11.3% and 9.8%, respectively) and β-pinene (38.5% and 45.0%, respectively). The sesquiterpene hydrocarbons trans-β-elemene (5.9% and 10.0%), and (E)-caryophyllene (12.2% and 14.4%) were major components in the leaf and stem essential oils, respectively. The leaf, stem, and rhizome essential oils from Z. vuquangensis from Vu Quang National Park, Ha Tinh Province, Vietnam, have been previously published [46]. A comparison of the major components is summarized in Table 4. Although there are qualitative similarities in the essential oil compositions from these two collections (α-pinene, β-pinene, and (E)-caryophyllene are major components), there are some notable differences. Bornyl acetate and zerumbone were major components in the rhizome essential oil from the Vu Quang collection, but were not observed in the Pù Hoạt sample; trans-β-elemene was observed in relatively small concentrations in the sample from Vu Quang, but was a major component in the leaf and stem essential oils from Pù Hoạt. The differences in chemical composition can be attributed to the geographical locations of the two collections and/or the season when the samples were collected. The Vu Quang sample was collected in August, 2014 (rainy season), while the Pù Hoạt sample was collected in April, 2019 (dry season).

Table 4.

Major components in the leaf, stem, and rhizome essential oils of Zingiber vuquangensis.

2.2. Mosquito Larvicidal Activity

Several of the Zingiber essential oils (depending on availability) were assayed for insecticidal activity against larvae of Aedes aegypti, Aedes albopictus, and Culex quinquefasciatus mosquitoes. The 24- and 48-h larvicidal activities are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Larvicidal activities of Zingiber essential oils from north-central Vietnam.

The essential oils showing the best larvicidal activity against Ae. aegypti were Z. cornubracteatum rhizome essential oil from Bến En National Park (24-h LC50 = 17.0 μg/mL) and Z. nudicarpum leaf essential oil from Pù Hoạt Nature Reserve (24-h LC50 = 19.3 μg/mL). The rhizome essential oil of Z. cornubracteatum also demonstrated remarkable activity against Ae. albopictus (24-h LC50 = 12.7 μg/mL). Both Z. nudicarpum leaf essential oil and rhizome essential oil were very active against Cx. quinquefasciatus larvae, with LC50 values of 12.4 and 11.5 μg/mL, respectively.

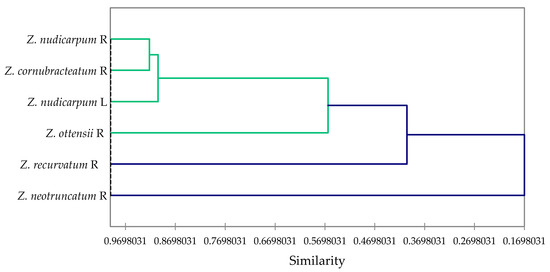

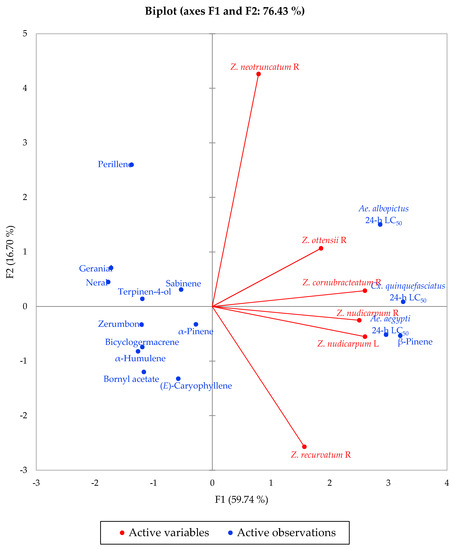

Multivariate analysis of the concentrations of the major components in the essential oils that were used for larvicidal activity screening (α-pinene, sabinene, β-pinene, perillene, terpinene-4-ol, neral, geranial, bornyl acetate, (E)-caryophyllene, α-humulene, bicyclogermacrene, and zerumbone), along with their 24-h larvicidal activities, reveals the correlation between activity and composition. The agglomerative hierarchical cluster (AHC) analysis (Figure 3) shows a cluster of largely active essential oils (Z. nudicarpum rhizome, Z. cornubracteatum rhizome, and Z. nudicarpum leaf), along with a marginally active essential oil (Z. ottensii rhizome), and two less active essential oils (Z. recurvatum rhizome and Z. neotruncatum rhizome). The concentrations of β-pinene and, to some extent, α-pinene, are largely responsible for the larvicidal activities of Zingiber essential oils, as seen in the principal component analysis (PCA) (Figure 4). Consistent with this correlation, β-pinene has shown larvicidal activity against Ae. Aegypti, with LC50 values ranging from 12.1 to 42.5 μg/mL [52]. β-Pinene has also shown larvicidal activities against Ae. albopictus (LC50 of 47.33 and 42.39 μg/mL for (+)-β-pinene and (−)-β-pinene, respectively) [53] and Cx. quinquefasciatus (LC50 = 19.6 μg/mL) [54]. α-Pinene and sabinene have also shown larvicidal activity against Ae. aegypti [52], Ae. albopictus [53,55,56], and Cx. quinquefasciatus [57,58].

Figure 3.

Dendrogram obtained from agglomerative hierarchical cluster analysis of the Zingiber essential oils screened for larvicidal activity.

Figure 4.

Principal component biplot of PC1 and PC2 scores and loadings indicating the correlations between Zingiber essential oil major components and larvicidal activities.

Several Zingiber essential oils have been screened for mosquito larvicidal activity. Consistent with the correlation of α- and β-pinene with Zingiber essential oil larvicidal activities, Z. nimmonii rhizome essential oil, with no α-pinene and only low β-pinene (0.8%), showed relatively marginal larvicidal activity against Ae. aegypti and Cx. quinquefasciatus (LC50 values of 44.5 and 48.3 μg/mL, respectively) [59]. Similarly, Z. cernuum rhizome essential oil, with 1.6% α-pinene and 1.2% β-pinene, showed relatively marginal larvicidal activities against Ae. aegypti (LC50 44.9 μg/mL), Ae. albopictus (LC50 55.8 μg/mL), or Cx. quinquefasciatus (LC50 48.4 μg/mL) [60], and the larvicidal activity of Z. zerumbet rhizome essential oil (0.8% α-pinene, 0.1% β-pinene) showed larvicidal activities against Ae. albopictus and Cx. quinquefasciatus with LC50 = 55.8 and 33.3 μg/mL, respectively [61]. Finally, Z. officinale rhizome oil showed relatively weak activity on Cx. quinquefasciatus larvae (LC50 = 50.8 μg/mL) [62]. Although the Z. officinale rhizome essential oil composition was not determined in this study, commercial Z. officinale oil (doTERRA International) contains 4.0% α-pinene and 0.4% β-pinene. In contrast, Z. collinsii rhizome essential oil, with 9.0% α-pinene and 16.3% β-pinene, demonstrated more effective larvicidal activity against Ae. albopictus with an LC50 of 25.5 μg/mL [63].

2.3. Antimicrobial Activity

Several of the essential oils from Zingiber species were tested for antibacterial activity against a panel of Gram-positive (Enterococcus faecalis, Staphylococcus aureus, and Bacillus cereus), and Gram-negative (Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Salmonella enterica) bacteria, and for anticandidal activity against Candida albicans (Table 6). The essential oils generally showed good to excellent activity against the Gram-positive organisms compared to Gram-negative. It has frequently been noted that Gram-positive bacteria demonstrate a higher susceptibility to essential oils than do Gram-negative organisms [64,65,66]. This phenomenon has been attributed to the existence of cell wall lipopolysaccharides in the Gram-negative bacteria, which can inhibit the hydrophobic essential oil constituents from diffusing into the cells [67,68]. Candida albicans was also relatively sensitive to the Zingiber essential oils.

Table 6.

Antibacterial and antifungal activities of Zingiber essential oils from north-central Vietnam.

The essential oil with the best overall antimicrobial activity was Z. nudicarpum rhizome essential oil from Pù Hoạt Nature Reserve with MIC < 10 μg/mL against all three Gram-positive organisms and MIC = 16 μg/mL against P. aeruginosa and C. albicans. It is difficult to correlate essential oil composition with antimicrobial activity, however. The rhizome essential oil of Z. nudicarpum was rich in α-pinene (18.7%) and β-pinene (58.3%). The antimicrobial activities of α-pinene and β-pinene have ranged from excellent to inactive against E. faecalis, S. aureus, B. cereus, or C. albicans [69,70,71]. However, the presence of these two compounds as major components is not enough to impart good antimicrobial activity. The leaf essential oil of Z. recurvatum and the leaf and stem essential oils of Z. cornubracteatum from Bến En National Park were also rich in α-pinene (16.3%, 10.1%, and 9.9%, respectively) and β-pinene (71.6%, 67.3%, and 66.8%), but these essential oils showed significantly lower antimicrobial activity. There are likely synergistic and/or antagonistic effects of minor components responsible for the activities.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Plant Material

3.2. Gas Chromatographic Analysis

Gas chromatography with flame ionization detection (GC-FID) was carried out as previously described [72]: Agilent Technologies HP 7890A Plus Gas chromatograph (Santa Clara, CA, USA), flame ionization detector (FID), HP-5ms column (30 m × 0.25 mm, film thickness 0.25 μm, Agilent Technologies), H2 carrier gas (1 mL/min), injector temperature = 250 °C, detector temperature = 260 °C, column temperature program: 60 °C (2 min hold), increase to 220 °C (4 °C /min), 220 °C (10 min hold), inlet pressure = 6.1 kPa, split mode injection (10:1) split ratio), 1.0 μL injection volume.

Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) was carried out as previously described [72]: Agilent Technologies HP 7890A Plus Chromatograph (Santa Clara, CA, USA), HP-5ms (30 m × 0.25 mm, film thickness 0.25 μm) column, HP 5973 MSD mass detector, He carrier gas (1 mL/min), MS ionization voltage = 70 eV, emission current = 40 mA, acquisitions range = 35–350 amu, sampling rate = 1.0 scan/s. The GC operating conditions were the same as those used for GC-FID. The chemical components of the essential oils were identified based on their retention indices (RI) based on a series of n-alkanes, co-injection with pure compounds when available (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) or identified essential oil components, MS library search (NIST 17 and Wiley Version 10) and by comparing with the literature MS fragmentation [73]. The relative concentrations (%) of the components were calculated based on the GC peak area (FID response) without correction factors. The measurements were carried out in triplicate.

3.3. Mosquito Larvicidal Screening

Larvae of Ae. aegypti, Ae. albopictus, and Cx. quinquefasciatus were raised in the laboratory as previously described [74]. Aedes aegypti larvae were reared from eggs (Institute of Biotechnology, Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology). Adults of Culex quinquefasciatus and Aedes albopictus were collected in Hoa Khanh Nam ward, Lien Chieu district, Da Nang city (16°03′14.9″ N, 108°09′31.2″ E) and were maintained as described previously [74]. Eggs were hatched and the larvae reared as previously described [74].

Fourth instar larvae of each mosquito species were used for the larvicidal assays, which were carried out as previously described [74]: 250-mL beakers, 150 mL of water, and 20 larvae, aliquots of the Zingiber essential oils dissolved in EtOH (1% stock solution) were added to give final concentrations of 100, 50, 25, 12.5, 6, and 3 μg/mL; EtOH only was the negative control, permethrin was the positive control, mortality was recorded after 24 and 48 h of exposure, experiments were carried out at 25 ± 2 °C, assays were carried out in quadruplicate. The larvicidal data were subjected to log-probit analysis [75] to obtain LC50 values, LC90 values and 95% confidence limits using Minitab® 19.2020.1 (Minitab, LLC, State College, PA, USA).

All procedures involving vertebrates (mice, chicks) were carried out in accordance with the “Guideline for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” which was approved by the Medical-Biological Research Ethics Committee of Duy Tan University (DTU/REC2020/NHH01), Vietnam.

3.4. Antimicrobial Screening

Antimicrobial activity of Zingiber essential oils was carried out on three Gram-negative organisms, Salmonella enterica (ATCC 13076), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC 27853), and Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922); three Gram-positive organisms, Bacillus cereus (ATCC 14579), Enterococcus faecalis (ATCC 299212), and Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 25923); and the pathogenic yeast, Candida albicans (ATCC 10231), using the microbroth dilution assay as previously described [72]. Dilutions were formulated from 16,384 to 2 μg/mL in sterile distilled water and pipetted into 96-well microplates. Bacteria were grown in tryptic soy broth or Mueller–Hinton broth (double-strength), fungi were grown in Sabouraud dextrose broth (double-strength). Bacteria and fungi were standardized to 5 × 105 CFU/mL for bacteria and 1 × 103 CFU/mL for the yeast. The final lane, containing only serial dilutions of the essential oil without bacteria or yeast, was treated as the positive control. Sterile water (no sample) and media with microorganisms were the negative controls; streptomycin was the positive antibiotic standard; cycloheximide and nystatin served as positive antifungal standards. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h and the minimum inhibitory concentrations were established as the well with the lowest concentration completely inhibiting microbial growth based on turbidity. The IC50 values were determined spectrophotometrically (EPOCH2C spectrophotometer, BioTeK Instruments, Inc Highland Park Winooski, VT, USA) and computed according to the following

where OD = optical density, control(−) = cells with medium but no antimicrobial agent, test agent is a known concentration of antimicrobial agent, control(+) = culture medium without cells, Highconc/Lowconc = concentration of test agent at high concentration/low concentration and Highinh%/Lowinh% = %inhibition at high concentration/% inhibition at low concentration). The antimicrobial assays were carried out in triplicate.

4. Conclusions

There are wide variations in essential oil compositions from the Zingiber species in this study, not only between species and tissues, as expected, but also between essential oils from the same species and tissues collected from different locations. This is an important consideration if the essential oils are to be used for agricultural or medicinal uses, but also if commercialization is considered. The monoterpenes α-pinene and β-pinene seem to be largely responsible for the mosquito larvicidal activities observed. It is worth investigating whether Zingiber or other essential oils rich in these components are viable alternatives for vector control. The presence of α-pinene and β-pinene cannot explain the antimicrobial activities of Zingiber essential oils, and synergistic or antagonistic interactions likely contribute. Nevertheless, several Zingiber essential oils have shown excellent antimicrobial activity and should be investigated further for controlling Gram-positive bacterial and yeast infections.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.T.H. and W.N.S.; methodology, L.T.H. and W.N.S.; software, L.T.H, D.N.D, and W.N.S.; validation, L.T.H., D.N.D., and W.N.S.; formal analysis, D.N.D. and W.N.S.; investigation, L.T.H., N.T.C., L.N.S., T.T.H., L.D.L., I.A.O., and N.H.H.; resources, L.T.H.; data curation, W.N.S.; writing—original draft preparation, L.T.H. and W.N.S.; writing—review and editing, L.T.H., W.N.S., and D.N.D.; visualization, L.T.H.; supervision, L.T.H.; project administration, L.T.H.; funding acquisition, L.T.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Vietnam National Foundation for Science and Technology Development (NAFOSTED), grant number 106.03-2017.328.

Acknowledgments

W.N.S. participated in this work as part of the activities of the Aromatic Plant Research Center (APRC, https://aromaticplant.org/).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Nealon, J.; Taurel, A.-F.; Yoksan, S.; Moureau, A.; Bonaparte, M.; Quang, L.C.; Capeding, M.R.; Prayitno, A.; Hadinegoro, S.R.; Chansinghakul, D.; et al. Serological evidence of Japanese encephalitis virus circulation in Asian children from dengue-endemic countries. J. Infect. Dis. 2019, 219, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thao, T.T.N.; de Bruin, E.; Phuong, H.T.; Vy, N.H.T.; van den Ham, H.-J.; Wills, B.A.; Tien, N.T.H.; Le Duyen, H.T.; Trung, D.T.; Whitehead, S.S.; et al. Using NS1 flavivirus protein microarray to infer past infecting dengue virus serotype and number of past dengue virus infections in Vietnamese individuals. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinh, T.C.; Bac, N.D.; Minh, L.B.; Ngoc, V.T.N.; Pham, V.-H.; Vo, H.-L.; Tien, N.L.B.; Van Thanh, V.; Tao, Y.; Show, P.L.; et al. Zika virus in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia: Are there health risks for travelers? Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2019, 38, 1585–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karna, A.K.; Bowen, R.A. Experimental evaluation of the role of ecologically-relevant hosts and vectors in Japanese encephalitis virus genotype displacement. Viruses 2019, 11, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Wispelaere, M.; Desprès, P.; Choumet, V. European Aedes albopictus and Culex pipiens are competent vectors for Japanese encephalitis virus. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2017, 11, e0005294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A.R.S.; Cohnstaedt, L.W.; Cernicchiaro, N. Japanese encephalitis virus: Placing disease ectors in the epidemiologic triad. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 2018, 111, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ta, T.; Tran, H.T.; Ha, Q.N.T.; Nguyen, X.T.; Tran, V.K.; Pham, H.T.; Simmons, C. The correlation of clinical and subclinical presentations with dengue serotypes and plasma viral load: The case of children with dengue hemorrhagic fever in Vietnam. Int. J. Res. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 10, 2578–2585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tun, M.M.N.; Nguyen, T.T.T.; Ando, T.; Dumre, S.P.; Soe, A.M.; Buerano, C.C.; Nguyen, M.T.; Le, N.T.N.; Pham, V.Q.; Nguyen, T.H.; et al. Clinical, virological, and cytokine profiles of children infected with dengue virus during the outbreak in southern Vietnam in 2017. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2020, 102, 1217–1225. [Google Scholar]

- Higa, Y.; Yen, N.T.; Kawada, H.; Son, T.H.; Hoa, N.T.; Takagi, M. Geographic distribution of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus collected from used tires in Vietnam. J. Am. Mosq. Control. Assoc. 2010, 26, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, D.-T.; Ngoc, V.T.N.; Tao, Y. Zika virus infection in Vietnam: Current epidemic, strain origin, spreading risk, and perspective. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2017, 36, 2041–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, T.T.; Van Dung, N.; Chinh, V.D.; Trung, H.D. Mapping insecticide resistance in dengue vectors in the northern Viet Nam, 2010–2013. Vector Biol. J. 2016, 1, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thi, K.P.; Viet, H.H.; Nguyen, H.M. Major resistant mechanism to insecticides of Aedes aegypti mosquito: A vector of dengue and Zika virus in Vietnam. SM Trop. Med. J. 2016, 1, 1010. [Google Scholar]

- Kasai, S.; Caputo, B.; Tsunoda, T.; Cuong, T.C.; Maekaw, Y.; Lam-Phua, S.G.; Pichler, V.; Itokawa, K.; Murota, K.; Komagata, O.; et al. First detection of a Vssc allele V1016G conferring a high level of insecticide resistance in Aedes albopictus collected from Europe (Italy) and Asia (Vietnam), 2016: A new emerging threat to controlling arboviral diseases. Euro Surveill. 2019, 24, 1700847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasteur, N.; Marquine, M.; Hoang, T.H.; Nam, V.S.; Failloux, A.B. Overproduced esterases in Culex pipiens quinquefasciatus (Diptera: Culicidae) from Vietnam. J. Med. Entomol. 2001, 38, 740–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itokawa, K.; Komagata, O.; Kasai, S.; Kawada, H.; Mwatele, C.; Dida, G.O.; Njenga, S.M.; Mwandawiro, C.; Tomita, T. Global spread and genetic variants of the two CYP9M10 haplotype forms associated with insecticide resistance in Culex quinquefasciatus Say. Heredity 2013, 111, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lien, L.T.Q.; Lan, P.T.; Chuc, N.T.K.; Hoa, N.Q.; Nhung, P.H.; Thoa, N.T.M.; Diwan, V.; Tamhankar, A.J.; Lundborg, C.S. Antibiotic resistance and antibiotic resistance genes in Escherichia coli isolates from hospital wastewater in Vietnam. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, G.M.; Ho-Le, T.P.; Ha, D.T.; Tran-Nguyen, C.H.; Nguyen, T.S.M.; Pham, T.T.N.; Nguyen, T.A.; Nguyen, D.A.; Hoang, H.Q.; Tran, N.V.; et al. Patterns of antimicrobial resistance in intensive care unit patients: A study in Vietnam. BMC Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van, P.H.; Binh, P.T.; Minh, N.H.L.; Morrissey, I.; Torumkuney, D. Results from the Survey of Antibiotic Resistance (SOAR) 2009-11 in Vietnam. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2016, 71, i93–i102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dat, V.Q.; Vu, H.N.; Nguyen The, H.; Nguyen, H.T.; Hoang, L.B.; Vu Tien Viet, D.; Bui, C.L.; Van Nguyen, K.; Nguyen, T.V.; Trinh, D.T.; et al. Bacterial bloodstream infections in a tertiary infectious diseases hospital in northern Vietnam: Aetiology, drug resistance, and treatment outcome. BMC Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabberley, D.J. Mabberley’s Plant-Book, 3rd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008; ISBN 978-0-521-82071-4. [Google Scholar]

- Kew Royal Botanic Gardens. The Plant List. Available online: http://www.theplantlist.org/tpl1.1/search?q=Zingiber (accessed on 21 July 2020).

- Sharifi-Rad, M.; Varoni, E.M.; Salehi, B.; Sharifi-Rad, J.; Matthews, K.R.; Ayatollahi, S.A.; Kobarfard, F.; Ibrahim, S.A.; Mnayer, D.; Zakaria, Z.A.; et al. Plants of the genus Zingiber as a source of bioactive phytochemicals: From tradition to pharmacy. Molecules 2017, 22, 2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong-Skornikova, J.; Newman, M. Gingers of Cambodia, Laos & Vietnam.; Oxford Graphic Printers Pte Ltd.: Singapore, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ly, N.-S. Zingiber skornickovae, a new species of Zingiberaceae from Central Vietnam. Phytotaxa 2016, 265, 139–144. [Google Scholar]

- Le, T.H.; Trinh, T.H.; Ly, N.S. Zingiber cornubracteatum Triboun & K. Larsen (Zingiberaceae), a new record for flora in Vietnam (in Vietnamese). J. Agric. Rural Dev. 2019, 21, 111–114. [Google Scholar]

- Triboun, P.; Larsen, K.; Chantaranothai, P. A key to the genus Zingiber (Zingiberaceae) in Thailand with descriptions of 10 new taxa. Thai J. Bot. 2014, 6, 53–77. [Google Scholar]

- Flora of China. Volume 24. Available online: http://www.efloras.org/flora_page.aspx?flora_id=2 (accessed on 14 July 2020).

- Nguyen, D.H.; Tran, M.H.; Ly, N.S.; Le, T.H.; Do, N.D. Zingiber neotruncatum T.L. Wu, K. Larsen & Turland, new record for flora in Vietnam (in Vietnamese). J. Sci. Nat. Sci. Technol. 2020, 36. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, M.F. A new species of Zingiber (Zingiberaceae) from Lao P.D.R. Gard. Bull. Singap. 2015, 67, 123–127. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, V.H.; Le, T.H.; Do, N.D.; Ly, N.S.; Nguyen, T.T. A new record Zingiber nitens M. F. Newman (Zingiberaceae) for flora of Vietnam (in Vietnamese). J. Sci. Nat. Sci. Technol. 2017, 33, 46–50. [Google Scholar]

- Hung, N.V.; Dai, D.N.; Thai, T.H.; San, N.D.; Ogunwande, I.A. Zingiber nitens M.F. Newman: A new species and its essential oil constituent. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants 2017, 20, 69–75. [Google Scholar]

- Souvannakhoummane, K.; Leong-Skorničková, J. Eight new records of Zingiber Mill. (Zingiberaceae) for the flora of Lao P.D.R. Edinb. J. Bot. 2018, 75, 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ly, N.-S.; Dang, V.-S.; Do, D.-G.; Tran, T.-T.; Do, N.-D.; Nguyen, D.-H. Zingiber nudicarpum D. Fang (Zingiberaceae), a newly recorded species for Vietnam. Biosci. Discov. 2017, 8, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Hung, N.D.; Huong, L.T.; Sam, L.N.; Hoi, T.M.; Ogunwande, I.A. Constituents of essential oil of Zingiber nudicarpum from Vietnam. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2019, 55, 361–363. [Google Scholar]

- Ly, N.-S.; Truong, B.-V.; Le, T.H. Zingiber ottensii Valeton (Zingiberaceae)—A newly recorded species for Vietnam. Biosci. Discov. 2016, 7, 93–96. [Google Scholar]

- Aung, M.M.; Tanaka, N. Seven taxa of Zingiber (Zingiberaceae) newly recorded for the flora of Myanmar. Bull. Natl. Museum Nat. Sci. Ser. B Bot. 2019, 45, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Sirat, H.M.; Nordin, A.B. Essential oil of Zingiber ottensii Valeton. J. Essent. Oil Res. 1994, 6, 635–636. [Google Scholar]

- Malek, S.N.A.; Ibrahim, H.; Lai, H.S.; Serm, L.G.; Seng, C.K.; Yussoff, M.M.; Ali, N.A.M. Essential oils of Zingiber ottensii Valet. and Zingiber zerumbet (L.) Sm. from Sabah, Malaysia. Malays. J. Sci. 2005, 24, 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Thubthimthed, S.; Limsiriwong, P.; Rerk-Am, U.; Suntorntanasat, T. Chemical composition and cytotoxic activity of the essential oil of Zingiber ottensii. Acta Hortic. 2005, 675, 107–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theanphong, O.; Jenjittikul, T.; Mingvanish, W. Chemotaxonomic study of volatile oils from rhizomes of 9 Zingiber species (Zingiberaceae). Thai J. Bot. 2016, 8, 127–139. [Google Scholar]

- Marliani, L.; Subarnas, A.; Moelyono, M.W.; Halimah, E.; Pratiwi, F.W.; Suhardiman, A. Essential oil components of leaves and rhizome of Zingiber ottensii Val. from Bandung, Indonesia. Res. J. Chem. Environ. 2018, 22, 54–57. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, S.; Xia, Y. New taxa of Zingiberaceae from southern Yunnan. Acta Phytotaxon. Sin. 1987, 25, 460–471. [Google Scholar]

- Averyanov, L.V.; Nguyen, T.H.; Nguyen, S.K.; Nguyen, T.S.; Ngan, C.Q.; Maisak, T.V. Conservation Assessment of Engandered Lao-Vietnamese Stenoendemic—Pinus Cernua (Pinaceae); Mohamed bin Zayed Species Conservation Fund: Abu Dhabi, UAE, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.C.; Ly, N.S.; Le, T.H. Zingiber recurvatum, new record for flora in Vietnam (in Vietnamese). J. Agric. Rural Dev. 2020, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Le, T.-H.; Trinh, T.-H.; Do, N.-D.; Nguyen, V.-H.; Ly, N.-S. Zingiber vuquangense (Sect. Cryptanthium: Zingiberaceae): A new species from north central coast region, Vietnam. Phytotaxa 2019, 388, 295–300. [Google Scholar]

- Huong, L.T.; Huong, T.T.; Huong, N.T.T.; Chau, D.T.M.; Sam, L.N.; Ogunwande, I.A. Zingiber vuquangensis and Z. castaneum: Two newly discovered species from Vietnam and their essential oil constituents. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2018, 13, 763–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, M.; Toyoda, M.; Honda, G. the essential oil of Perilla frutescens. Nat. Med. 1999, 53, 32–36. [Google Scholar]

- Mathela, C.S.; Melkani, A.B.; Bisht, J.C.; Pant, A.K.; Bestmann, H.J.; Erler, J.; Kobold, U.; Rauscher, J.; Vostrowsky, O. Chemical varieties of essential oils from Elsholtzia polystachya from two different locations in India. Planta Med. 1992, 58, 376–379. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, S.; Pandotra, P.; Ram, G.; Anand, R.; Gupta, A.P.; Husain, M.K.; Bedia, Y.S.; Mallavarapu, G.R. Composition of a monoterpenoid-rich essential oil from the rhizome of Zingiber officinale from north western Himalayas. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2011, 6, 93–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Höferl, M.; Stoilova, I.; Wanner, J.; Schmidt, E.; Jirovetz, L.; Trifonova, D.; Stanchev, V.; Krastanov, A. Composition and comprehensive antioxidant activity of ginger (Zingiber officinale) essential oil from Ecuador. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2015, 10, 1085–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chane-Ming, J.; Vera, R.; Chalchat, J.-C. Chemical composition of the essential oil from rhizomes, leaves and flowers of Zingiber zerumbet Smith from Reunion Island. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2003, 15, 202–205. [Google Scholar]

- Dias, C.N.; Moraes, D.F.C. Essential oils and their compounds as Aedes aegypti L. (Diptera: Culicidae) larvicide: Review. Parasitol. Res. 2014, 113, 565–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giatropoulos, A.; Papachristos, D.P.; Kimbaris, A.; Koliopoulos, G.; Polissiou, M.G.; Emmanouel, N.; Michaelakis, A. Evaluation of bioefficacy of three Citrus essential oils against the dengue vector Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) in correlation to their components enantiomeric distribution. Parasitol. Res. 2012, 111, 2253–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade-Ochoa, S.; Sánchez-Aldana, D.; Chacón-Vargas, K.F.; Rivera-Chavira, B.E.; Sánchez-Torres, L.E.; Camacho, A.D.; Nogueda-Torres, B.; Nevárez-Moorillón, G.V. Oviposition deterrent and larvicidal and pupaecidal activity of seven essential oils and their major components against Culex quinquefasciatus Say (Diptera: Culicidae): Synergism—Antagonism effects. Insects 2018, 9, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindarajan, M.; Rajeswary, M.; Hoti, S.L.; Bhattacharyya, A.; Benelli, G. Eugenol, α-pinene and β-caryophyllene from Plectranthus barbatus essential oil as eco-friendly larvicides against malaria, dengue and Japanese encephalitis mosquito vectors. Parasitol. Res. 2016, 115, 807–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade-Ochoa, S.; Sánchez-Torres, L.E.; Nevárez-Moorillón, G.V.; Camacho, A.D.; Nogueda-Torres, B. Aceites esenciales y sus constituyentes como una alternativa en el control de mosquitos vectores de enfermedades. Biomedica 2017, 37, 224–243. [Google Scholar]

- Govindarajan, M. Chemical composition and larvicidal activity of leaf essential oil from Clausena anisata (Willd.) Hook. f. ex Benth (Rutaceae) against three mosquito species. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2010, 3, 874–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade-Ochoa, S.; Correa-Basurto, J.; Rodríguez-Valdez, L.M.; Sánchez-Torres, L.E.; Nogueda-Torres, B. In vitro and in silico studies of terpenes, terpenoids and related compounds with larvicidal and pupaecidal activity against Culex quinquefasciatus Say (Diptera: Culicidae). Chem. Cent. J. 2018, 12, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Govindarajan, M.; Rajeswary, M.; Arivoli, S.; Tennyson, S.; Benelli, G. Larvicidal and repellent potential of Zingiber nimmonii (J. Graham) Dalzell (Zingiberaceae) essential oil: An eco-friendly tool against malaria, dengue, and lymphatic filariasis mosquito vectors? Parasitol. Res. 2016, 115, 1807–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajeswary, M.; Govindarajan, M.; Alharbi, N.S.; Kadaikunnan, S.; Khaled, J.M.; Benelli, G. Zingiber cernuum (Zingiberaceae) essential oil as effective larvicide and oviposition deterrent on six mosquito vectors, with little non-target toxicity on four aquatic mosquito predators. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 10307–10316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huong, L.T.; Chinh, H.V.; An, N.T.G.; Viet, N.T.; Hung, N.H.; Thuong, N.T.H.; Giwa-Ajeniya, A.O.; Ogunwande, I.A. Zingiber zerumbet rhizome essential oil: Chemical composition, antimicrobial and mosquito larvicidal activities. Eur. J. Med. Plants 2019, 30, 53652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushpanathan, T.; Jebanesan, A.; Govindarajan, M. The essential oil of Zingiber officinalis Linn (Zingiberaceae) as a mosquito larvicidal and repellent agent against the filarial vector Culex quinquefasciatus Say (Diptera: Culicidae). Parasitol. Res. 2008, 102, 1289–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huong, L.T.; Huong, T.T.; Huong, N.T.T.; Hung, N.H.; Dat, P.T.T.; Luong, N.X.; Ogunwande, I.A. Mosquito larvicidal activity of the essential oil of Zingiber collinsii against Aedes albopictus and Culex quinquefasciatus. J. Oleo Sci. 2020, 69, 153–160. [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Palmer, A.; Stewart, J.; Fyfe, L. Antimicrobial properties of plant essential oils and essences against five important food-borne pathogens. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 1998, 26, 118–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izadi, Z.; Esna-Ashari, M.; Piri, K.; Davoodi, P. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of feverfew (Tanacetum parthenium) essential oil. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 2010, 12, 759–763. [Google Scholar]

- Djihane, B.; Wafa, N.; Elkhamssa, S.; Pedro, D.H.J.; Maria, A.E.; Mohamed Mihoub, Z. Chemical constituents of Helichrysum italicum (Roth) G. Don essential oil and their antimicrobial activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, filamentous fungi and Candida albicans. Saudi Pharm. J. 2017, 25, 780–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inouye, S.; Takizawa, T.; Yamaguchi, H. Antibacterial activity of essential oils and their major constituents against respiratory tract pathogens by gaseous contact. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2001, 47, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazzaro, F.; Fratianni, F.; De Martino, L.; Coppola, R.; De Feo, V. Effect of essential oils on pathogenic bacteria. Pharmaceuticals 2013, 6, 1451–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Zyl, R.L.; Seatlholo, S.T.; van Vuuren, S.F.; Viljoen, A.M. The biological activities of 20 nature identical essential oil constituents. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2006, 18, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, N.T.G.; Huong, L.T.; Satyal, P.; Tai, T.A.; Dai, D.N.; Hung, N.H.; Ngoc, N.T.B.; Setzer, W.N. Mosquito larvicidal activity, antimicrobial activity, and chemical compositions of essential oils from four species of Myrtaceae from central Vietnam. Plants 2020, 9, 544. [Google Scholar]

- De Carlo, A.; Zeng, T.; Dosoky, N.S.; Satyal, P.; Setzer, W.N. The essential oil composition and antimicrobial activity of Liquidambar formosana oleoresin. Plants 2020, 9, 822. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, N.T.; Huong, L.T.; Hung, N.H.; Hoi, T.M.; Dai, D.N. Chemical composition of Actinodaphne pilosa essential oil From Vietnam, mosquito larvicidal activity, and antimicrobial activity. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2020, 15, 1934578X20917792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.P. Identification of Essential Oil Components by Gas. Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry, 4th ed.; Allured Publishing: Carol Stream, IL, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-1-932633-21-4. [Google Scholar]

- Hung, N.H.; Satyal, P.; Do, N.D.; Tai, T.A.; Huong, L.T.; Chuong, N.T.H.; Hieu, H.V.; Tuan, P.A.; Van Vuong, P.; Setzer, W.N. Chemical compositions of Crassocephalum crepidioides essential oils and larvicidal activities against Aedes aegypti, Aedes albopictus, and Culex quinquefasciatus. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2019, 14, 1934578X19850033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finney, D. Probit Analysis, Reissue ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009; ISBN 978-0521135900. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).