Abstract

Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge is a traditional Chinese medicinal plant whose roots are rich in water-soluble phenolic acids. Rosmarinic acid and salvianolic acid B are representative components that confer antibacterial, antioxidant, and cardio-cerebrovascular protective activities. However, these metabolites often accumulate at low and unstable levels in planta, which limits their efficient development and use. This review summarises recent advances in understanding salvianolic acid biosynthesis and its transcriptional regulation in S. miltiorrhiza. Current evidence supports a coordinated pathway composed of the phenylpropanoid route and a tyrosine-derived branch, which converge to generate rosmarinic acid and subsequently more complex derivatives through oxidative coupling reactions. Key findings on transcription factor families that fine-tune pathway flux by regulating core structural genes are synthesised. Representative positive regulators such as SmMYB111, SmMYC2, and SmTGA2 activate key nodes (e.g., PAL, TAT/HPPR, RAS, and CYP98A14) to promote phenolic acid accumulation. Conversely, negative regulators such as SmMYB4 and SmMYB39 repress pathway genes and/or interfere with activator complexes. Major regulatory features include hormone-inducible signalling, cooperative regulation through transcription factor complexes, and emerging post-transcriptional and post-translational controls. Future directions and challenges are discussed, including overcoming regulatory redundancy and strong spatiotemporal specificity of transcriptional control. Integrating spatial and single-cell omics with functional genomics (e.g., genome editing and rational TF stacking) is highlighted as a promising strategy to enable predictive metabolic engineering for the stable, high-yield production of salvianolic acid-type compounds.

1. Introduction

Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge (Danshen) is a perennial herb of the Lamiaceae family whose dried roots and rhizomes are widely used in traditional Chinese medicine to promote blood circulation, resolve blood stasis, and alleviate pain and restlessness [1,2]. Phytochemical studies have identified more than 100 constituents from S. miltiorrhiza [3]. The pharmacological activities of Danshen are mainly attributed to two major groups of specialised metabolites: lipophilic diterpenoids and water-soluble phenolic acids, among which rosmarinic acid (RA) and salvianolic acid B (Sal B) are the most representative compounds [4,5]. These phenolic acids, collectively referred to as salvianolic acids, exhibit antibacterial, antioxidant, antiviral, and cardio-cerebrovascular protective effects and are widely used for the treatment of vascular disorders such as atherosclerosis and myocardial ischaemia, conferring high medicinal and economic value [6,7]. Nevertheless, salvianolic acids typically accumulate at relatively low levels in planta, and their production is tightly controlled by multiple internal and environmental factors, which hampers the stable supply required for efficient exploitation of these bioactive ingredients. Therefore, a comprehensive understanding of the biosynthetic pathways and regulatory mechanisms underlying salvianolic acid formation is critical for the rational improvement, development, and utilisation of these valuable metabolites.

With the publication of the S. miltiorrhiza genome and the rapid accumulation of multi-omics datasets, substantial progress has been made in elucidating the biosynthetic pathway of salvianolic acids and in identifying key structural genes, including phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL), cinnamate 4-hydroxylase (C4H), 4-coumarate:CoA ligase (4CL), tyrosine aminotransferase (TAT), and 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate reductase (HPPR). These efforts have largely clarified the overall architecture of the phenylpropanoid and tyrosine-derived branches. In parallel, several transcription factor (TF) families, such as MYB, basic helix–loop–helix (bHLH), APETALA2/ethylene-responsive factor (AP2/ERF), and WRKY, have been shown to act as positive or negative regulators of salvianolic acid biosynthesis by modulating the transcription of pathway genes, thereby altering salvianolic acid accumulation. Collectively, these findings outline an emerging regulatory cascade connecting external and endogenous cues with TFs, structural genes, and ultimately metabolite production.

In this review, recent progress in TF–mediated regulation of salvianolic acid biosynthesis in S. miltiorrhiza is summarised, with emphasis on the functional features, regulatory mechanisms, and network interactions of different TF families. The aim is to provide a conceptual framework and reference for further dissection of the regulatory networks controlling salvianolic acid metabolism and for the rational improvement and efficient utilisation of these valuable metabolites.

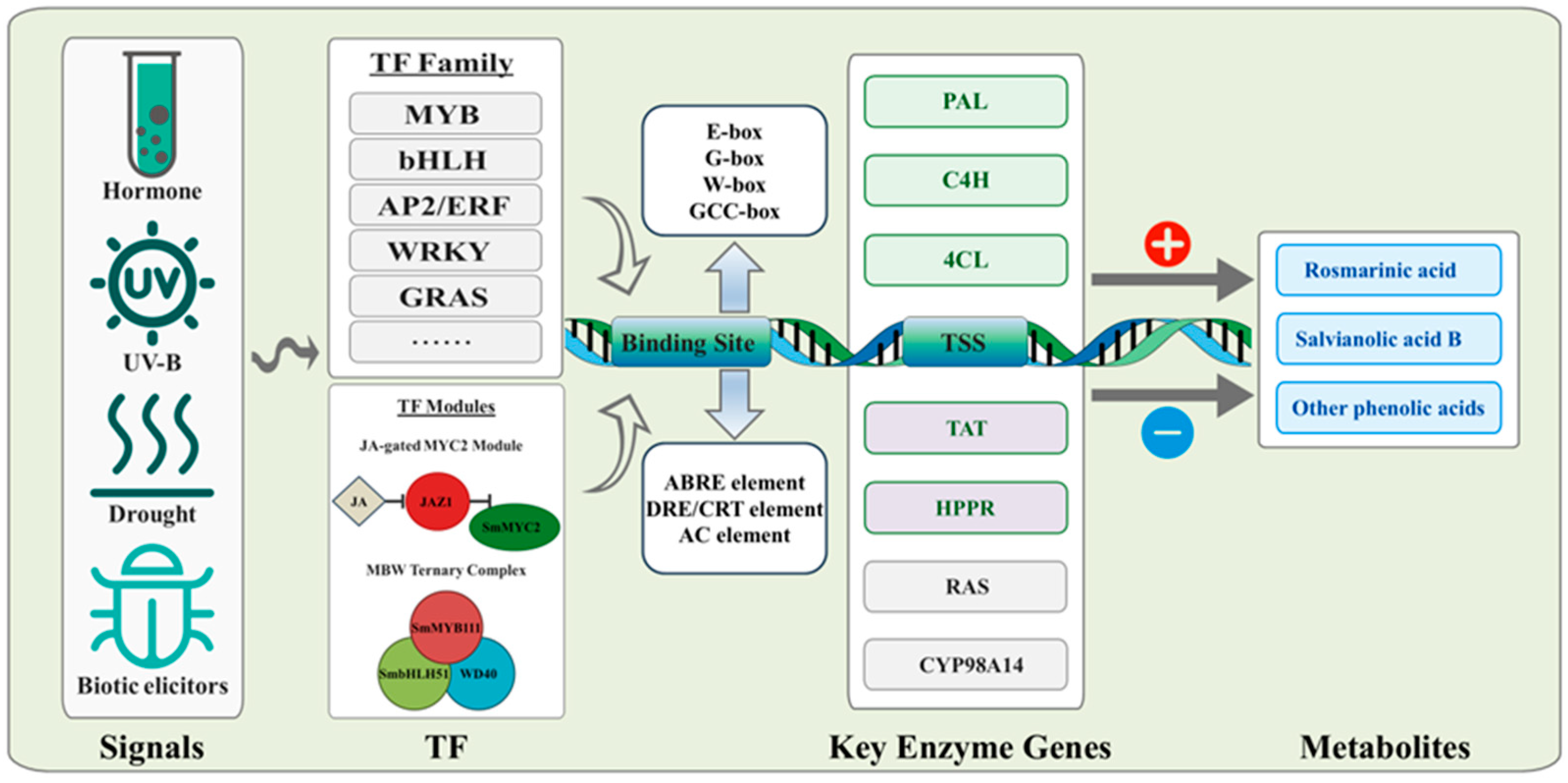

Based on the available evidence, an integrated model linking signals, regulatory modules, promoter cis-elements, key enzyme genes, and metabolite outputs is proposed (Figure 1). This model provides a conceptual framework for the family-by-family discussion below.

Figure 1.

Integrated regulatory framework for salvianolic acid biosynthesis in S. miltiorrhiza.

2. Literature Search Strategy

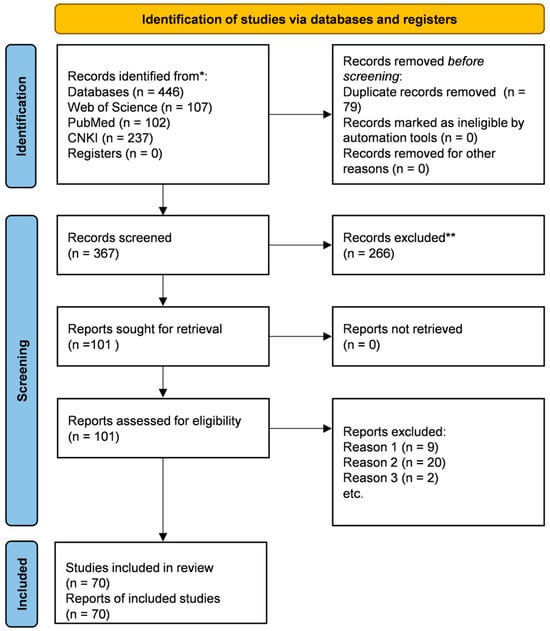

To ensure a comprehensive and reproducible overview of recent advances, a systematic literature search was conducted following the PRISMA 2020 guidelines [8]. The primary objective was to identify all relevant studies investigating transcription factor-mediated regulation of salvianolic acid biosynthesis in S. miltiorrhiza.

Electronic searches were performed in the Web of Science Core Collection, PubMed, and the China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) databases, covering the period from January 2000 up to the date of the search (December 2025). The search strategy combined keywords and Boolean operators: (“Salvia miltiorrhiza” OR “S. miltiorrhiza” OR Danshen) AND (“salvianolic acid” OR “rosmarinic acid” OR “phenolic acid”) AND (“transcription factor” OR “transcriptional regulat*” OR MYB OR bHLH OR WRKY OR ERF OR NAC). The search was limited to studies published in English or Chinese.

The retrieved records were screened in two stages based on predefined criteria. Inclusion criteria were: (1) original research or review articles focusing on the identification, characterisation, or functional analysis of transcription factors in S. miltiorrhiza; (2) studies explicitly linking TF function to the salvianolic acid/rosmarinic acid biosynthetic pathway; (3) studies providing molecular evidence (e.g., gene expression, promoter binding, transgenic validation). Exclusion criteria were: (1) studies focusing solely on chemical profiling, pharmacological effects, or other metabolic pathways (e.g., tanshinones) without mechanistic regulatory insights; (2) conference abstracts, or non-peer-reviewed articles without sufficient experimental detail.

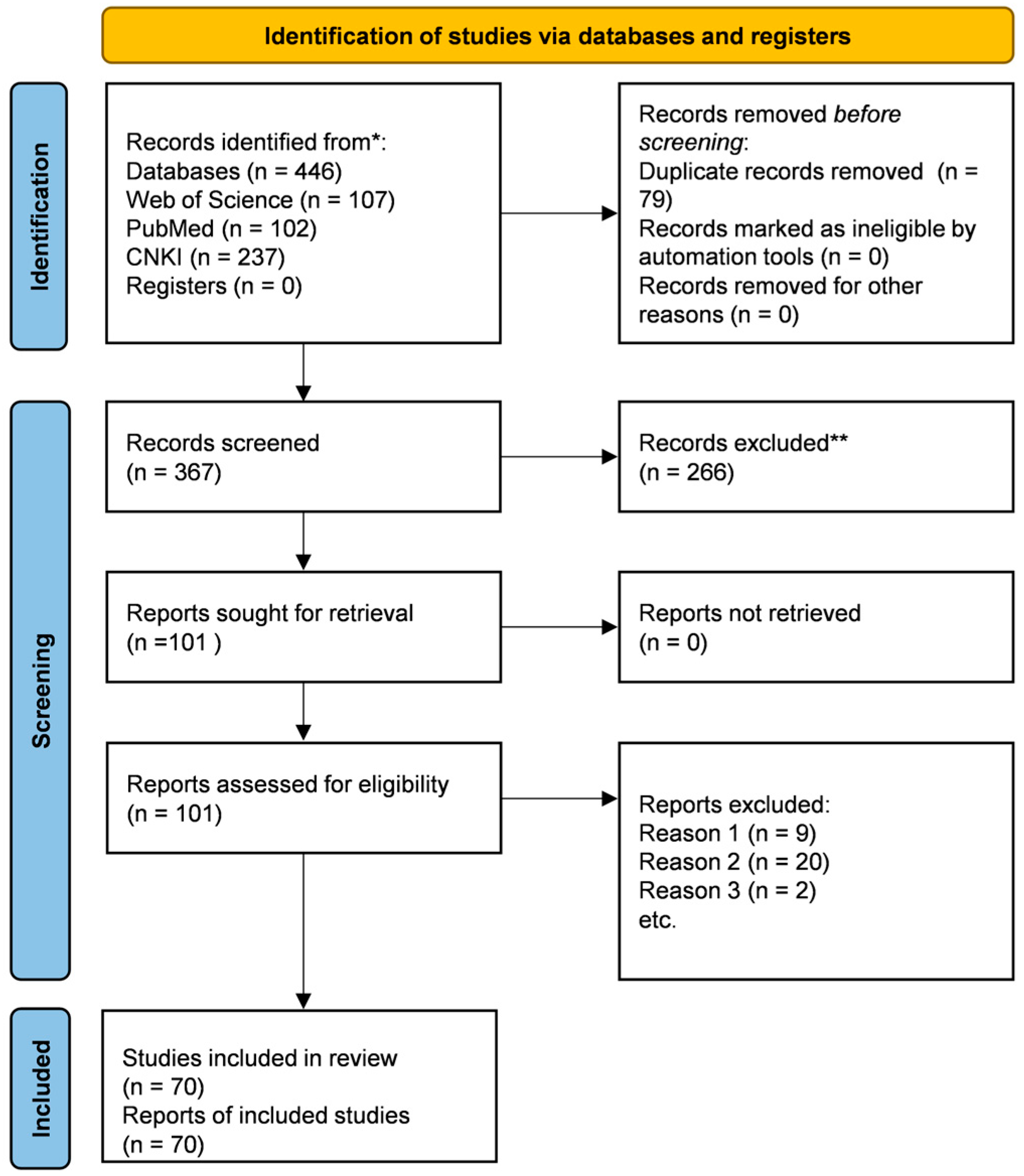

The screening process is summarised in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 2). A total of 446 records were identified through database searching (107 from Web of Science, 102 from PubMed, 237 from CNKI). After removing 79 duplicates, 367 unique records were screened by title and abstract. Of these, 266 records were excluded, and 101 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. After full-text review, 31 articles were excluded for the following reasons: (1) duplicate or overlapping study (where a more comprehensive report was available); (2) the studied regulator did not meet our core criteria for an S. miltiorrhiza transcription factor (e.g., non-TF proteins or heterologous TFs); or (3) insufficient mechanistic evidence to confirm a direct regulatory function. Consequently, 70 studies were included for qualitative synthesis in this review. Data regarding TF names, families, functions, regulatory mechanisms, and experimental evidence were extracted and thematically organised to construct the current synthesis.

Figure 2.

PRISMA flow diagram of the literature search and selection process for studies on transcription factor-mediated regulation of salvianolic acid biosynthesis in S. miltiorrhiza. Notes: * The number of records identified is reported for each database/register searched. ** No automation tools were used; all records were screened and excluded by the reviewers.

3. Biosynthetic Pathways of Salvianolic Acids and Transcriptional Regulation

3.1. Salvianolic Acid Biosynthetic Pathways

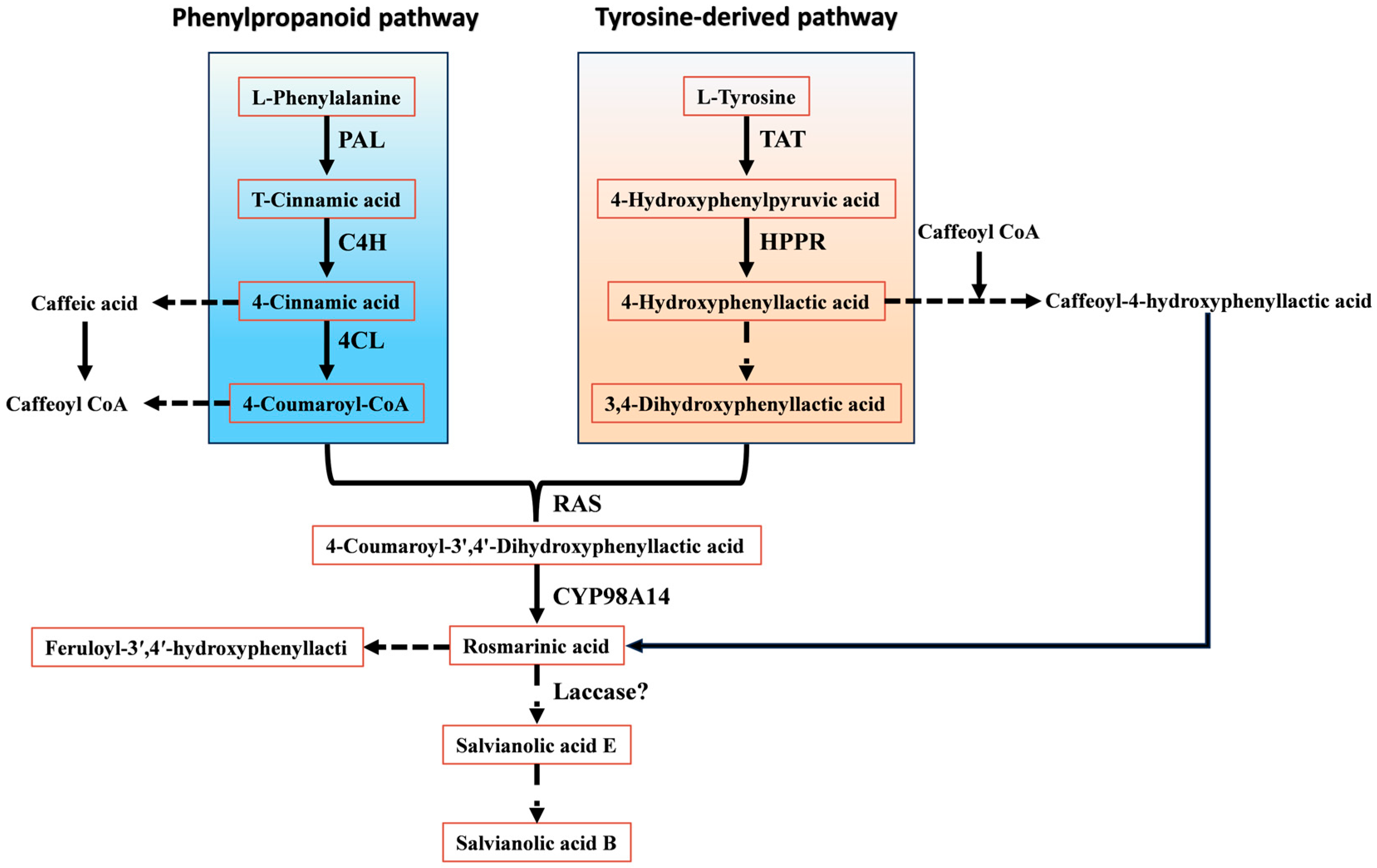

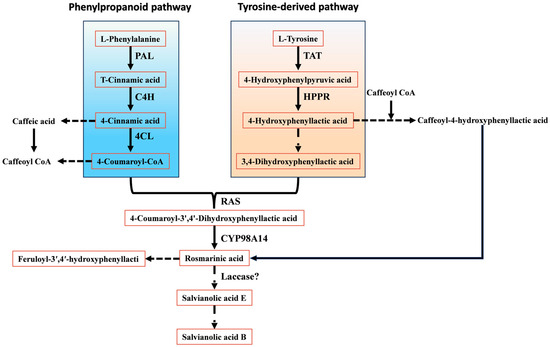

Recent work indicates that salvianolic acid biosynthesis in S. miltiorrhiza is orchestrated through coordinated operation of the phenylpropanoid pathway and a tyrosine-derived branch [9]. The phenylpropanoid route provides 4-coumaroyl-CoA, whereas the tyrosine-derived route generates 4-hydroxyphenyllactic acid; together, these compounds act as central precursors for RA formation. In the phenylpropanoid pathway, phenylalanine is first deaminated to cinnamic acid by PAL. Cinnamic acid is then hydroxylated and activated to 4-coumaroyl-CoA by C4H and 4CL, respectively. In parallel, tyrosine is converted to 4-hydroxyphenyllactic acid through successive reactions catalysed by TAT and HPPR. These two branches ultimately converge when rosmarinic acid synthase (RAS) and the cytochrome P450 monooxygenase CYP98A14 catalyse condensation of 4-coumaroyl-CoA and 4-hydroxyphenyllactic acid to yield RA, a pivotal intermediate in salvianolic acid biosynthesis (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Biosynthetic pathways of salvianolic acids.

Notably, Di et al. [10] proposed an alternative major route for RA formation. In this phenylpropanoid branch, 4-coumaric acid is first hydroxylated to caffeic acid (CA) rather than being directly activated to a CoA thioester; CA is subsequently converted to caffeoyl-CoA. In S. miltiorrhiza, RAS then catalyses coupling of caffeoyl-CoA with 4-hydroxyphenyllactic acid to produce caffeoyl-4-hydroxyphenyllactic acid, which is finally converted to RA by CYP98A14.

RA serves not only as an end product in S. miltiorrhiza but also as a common precursor for most salvianolic acids. On the RA scaffold, further oxidative coupling and polymerisation reactions give rise to structurally more complex phenolic acids, such as salvianolic acid A (Sal A) and Sal B. Current evidence suggests that Sal B biosynthesis proceeds through phenoxy radical–mediated coupling between RA and its derivatives, although the complete set of catalytic enzymes has not yet been comprehensively identified. Structurally, Sal B can be regarded as a condensation product of two CA moieties and two molecules of danshensu, or alternatively as a dimerisation product derived from RA–based phenoxy radicals. Li et al. [11,12] proposed that Sal B may be generated from two RA molecules via radical formation at the 2-position of the aromatic ring and the corresponding α-carbon, followed by radical coupling to yield Sal B directly, or through salvianolic acid E as an intermediate under the action of laccases and other oxidative enzymes. In addition, Xu et al. [13] reconstructed a de novo RA biosynthetic pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by heterologous expression of PAL, C4H, 4CL, TAT, HPPR, RAS, and CYP98A14. Interestingly, low levels of Sal B were detected in the engineered yeast even without introduction of a specific polymerase, suggesting that RA may undergo spontaneous oxidative coupling under certain conditions.

Most key structural genes required for salvianolic acid biosynthesis, including PAL, C4H, 4CL, TAT, HPPR, RAS, and CYP98A14, have been cloned and functionally characterised. Among these enzymes, PAL in the phenylpropanoid pathway is widely regarded as the first rate-limiting step, and its transcript abundance is often positively associated with accumulation of downstream phenolic compounds [14]. TAT and HPPR play critical regulatory roles in the tyrosine-derived branch, and HPPR in particular is considered a major bottleneck enzyme that determines the supply capacity of 4-hydroxyphenyllactic acid [15,16].

3.2. Transcription Factors Regulating Salvianolic Acid Biosynthesis

TFs occupy central positions in the regulatory network controlling salvianolic acid biosynthesis and fine-tune pathway output through three principal modes. First, salvianolic acid formation depends on multiple interconnected metabolic routes, including the phenylpropanoid pathway, terpenoid biosynthesis, and polyphenol metabolism. TFs modulate metabolic flux by recognising and binding cis-regulatory elements in the promoters of key structural genes such as PAL, C4H, TAT, HPPR, and CYP98A14, thereby altering their transcriptional activity [17]. For example, several MYB TFs, including SmMYB4, repress expression of SmPAL, SmC4H, Sm4CL2, and SmTAT, which results in reduced salvianolic acid accumulation [18], whereas others such as SmMYB1 act as positive regulators that activate these pathway genes and enhance metabolite production [19]. Second, certain TFs control secondary metabolism by responding to external or endogenous signals; for instance, SmERF1L1 is induced by jasmonic acid (JA) and markedly decreases the levels of RA and salvianolic acid A. Third, different classes of TFs, including MYB, bHLH, WRKY, and NAC proteins, frequently engage in protein–protein interactions to assemble regulatory complexes that coordinately regulate target gene expression, thereby forming a complex transcriptional network. Within the bHLH family, the core regulator SmMYC2 has been shown to interact with SmMYB111, which attenuates transcriptional activation of key genes in the phenolic acid biosynthetic pathway [20].

To date, members of multiple TF families have been identified as positive or negative regulators of salvianolic acid biosynthesis. Systematic synthesis of their regulatory mechanisms will help refine current models of transcriptional control over salvianolic acid production.

4. Characteristics of Transcription Factors Regulating Salvianolic Acid Biosynthesis

4.1. Transcription Factor Families and Structural Features

TFs are key components of regulatory networks that control plant secondary metabolism. By recognising specific cis-acting elements in the promoters of target genes, they modulate transcriptional activity and thereby affect the synthesis and accumulation of specialised metabolites. In S. miltiorrhiza, several TF families have been associated with salvianolic acid metabolism, including AP2/ERF, bHLH, R2R3-MYB, WRKY, GRAS, basic leucine zipper (bZIP), NAC, TCP, SQUAMOSA promoter-binding protein-like (SPL), and LATERAL ORGAN BOUNDARIES DOMAIN (LBD) proteins.

The MYB family is the largest TF family in plants and has roles in disease resistance, nutrient uptake, responses to environmental stresses, plant development, and regulation of secondary metabolite biosynthesis, such as flavonoids and terpenoids [21]. A defining feature of MYB proteins is the presence of one or more MYB DNA-binding domains, each consisting of an imperfect repeat (R) of approximately 52 amino acids that forms a helix–turn–helix structure [22]. This structure enables specific recognition of MYB core motifs and AC-rich cis-acting elements in target promoters [23]. Based on the number of repeats within the MYB domain, plant MYB proteins are classified into four groups: 1R-MYB, R2R3-MYB, 3R-MYB, and 4R-MYB, among which R2R3-MYB proteins represent the most abundant subtype [24]. In S. miltiorrhiza, 110 R2R3-MYB transcription factors have been identified [25]. Most MYB regulators functionally implicated in specialised metabolism (including phenolic acids and tanshinones) reported to date belong to the R2R3-MYB subgroup.

The bHLH family is the second largest TF family in plants after MYB. bHLH proteins share a conserved domain of approximately 60 amino acids, comprising an N-terminal basic region of 15–20 residues responsible for DNA recognition and a C-terminal helix–loop–helix region of 40–50 residues that mediates protein dimerisation. These TFs preferentially bind E-box elements (CANNTG), with the canonical G-box motif (CACGTG) as a common target [26,27]. Based on conserved structural features and phylogenetic relationships, 127 bHLH members have been identified in S. miltiorrhiza and assigned to 25 subfamilies [28].

AP2/ERF TFs are plant-specific and are characterised by the presence of a signature AP2 DNA-binding domain and responsiveness to ethylene signalling. The AP2 domain comprises approximately 60–70 amino acids and adopts a typical three-dimensional structure consisting of one α-helix and three β-sheets, which enables recognition of GCC-box (AGCCGCC) elements in target promoters [29]. According to the number and structural features of AP2 domains, the AP2/ERF superfamily is commonly divided into four subfamilies: AP2, ERF/DREB, related to RAV, and Soloist. The ERF/DREB subfamily contains a single AP2 domain and can be further subdivided into the ERF and DREB groups, which are mainly distinguished by the amino acid residues at positions 14 and 19 within this domain [30]. In most plant species, the AP2/ERF family includes more than 100 members, with ERF and DREB constituting the largest groups, followed by AP2 [31]. In S. miltiorrhiza, 170 AP2/ERF-type TFs have been identified, and a subset is predicted to regulate salvianolic acid biosynthesis [32].

The WRKY family is named after the conserved N-terminal heptapeptide sequence WRKYGQK within the WRKY domain. WRKY proteins typically contain one or two WRKY domains together with a C2H2- or C2HC-type zinc-finger motif, which enables specific binding to W-box elements ((T)TGAC(C/T)) in target gene promoters [33]. Based on the number of WRKY domains and the type of zinc finger, WRKY TFs are classified into three major groups: group I proteins possess two WRKY domains and a C2H2 zinc-finger motif; group II proteins contain a single WRKY domain and a C2H2 zinc-finger motif; and group III proteins harbour one WRKY domain and a C2HC zinc-finger motif [34]. In S. miltiorrhiza, 69 WRKY family members have been identified to date [35].

The GRAS TF family is named after its initially characterised members GIBBERELLIN INSENSITIVE (GAI), REPRESSOR OF ga1-3 (RGA), and SCARECROW (SCR). GRAS proteins generally comprise 400–770 amino acids and contain a highly conserved C-terminal region with five characteristic motifs: leucine heptad repeat I (LHR I), the VHIID core motif, leucine heptad repeat II (LHR II), and the PFYRE and SAW motifs. In contrast, the N-terminal region is highly variable, except in the DELLA subfamily, and often includes intrinsically disordered regions associated with regulatory functions [36,37]. Based on sequence similarity and phylogenetic relationships, the GRAS family is divided into several subfamilies, including DELLA, SHORT-ROOT (SHR), SCR, and PHYTOCHROME A SIGNAL TRANSDUCTION 1 (PAT1). In S. miltiorrhiza, 34 GRAS family members have been identified [38].

bZIP TFs represent another family that regulates salvianolic acid biosynthesis. They are characterised by a conserved bZIP domain comprising a basic region responsible for nuclear localisation and DNA binding, and a leucine zipper region formed by heptad repeats of leucine or other hydrophobic residues (L-X6-L-X6-L) that mediates dimerisation. Two bZIP monomers associate through this zipper to form dimers that preferentially recognise cis-acting elements containing an ACGT core sequence [39,40]. Plant bZIP proteins are generally classified into multiple subgroups (A–S), whose members function in hormone signalling, adaptation to environmental stresses, and regulation of secondary metabolism. In S. miltiorrhiza, 70 bZIP TFs have been identified [41].

NAC TFs, named after NO APICAL MERISTEM (NAM) in Petunia hybrida and Arabidopsis thaliana TRANSCRIPTION ACTIVATION FACTOR1/2 (ATAF1/2) and CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON1/2 (CUC1/2) in A. thaliana, function across diverse processes, including plant development and responses to biotic and abiotic stresses. NAC proteins possess a highly conserved N-terminal NAC domain subdivided into five subdomains (A–E) that mediate DNA binding, dimer formation, and nuclear localisation. By contrast, the C-terminal region is a diversified transcriptional activation region (TAR). Some NAC proteins contain an additional C-terminal transmembrane motif and are referred to as NTLs (NAC with transmembrane motif) [42]. In S. miltiorrhiza, 84 NAC genes (SmNACs) have been identified [43].

TCP TFs constitute a plant-specific family characterised by a highly conserved TCP domain of approximately 58–62 amino acids. This domain forms an atypical bHLH-like structure, consisting of a stretch enriched in basic residues followed by two α-helices connected by a loop [44]. Structural analyses indicate that the TCP domain forms a β-strand at the dimer interface and uses a flexible basic loop at the N-terminus to contact DNA, establishing a distinctive three-site recognition mode. Based on structural features, TCP proteins are divided into two classes: class I (PCF type) and class II (CIN and CYC/TB1 types). Class I proteins lack four amino acids in the basic region, whereas class II proteins typically contain additional motifs such as the R domain or the ECE motif [45]. In S. miltiorrhiza, 84 TCP genes (SmTCPs) have been identified [46].

SPL TFs are defined by the SBP domain of approximately 76 amino acids. This domain contains two zinc-finger motifs and a nuclear localisation signal that partially overlaps with the second zinc finger, enabling specific recognition of GTAC-containing motifs in target promoters. Outside the SBP domain, SPL protein sequences show limited conservation, but distinct structural features correspond to different evolutionary groups. For example, groups I and II typically contain N-terminal phosphorylation sites that regulate protein stability under stress conditions, whereas groups III and IV possess C-terminal glutamine-rich regions that facilitate protein–protein interactions [47]. In S. miltiorrhiza, 15 SPL genes (SmSPLs) have been identified [48].

LBD TFs are defined by a characteristic LOB domain of approximately 100 amino acids. This domain contains a CX2CX6CX3C zinc-finger motif that mediates DNA binding, a central GAS region with a conserved glycine residue critical for function, and an LZL (leucine zipper-like) coiled-coil motif that supports protein dimerisation. Based on differences in the LOB domain, LBD proteins are divided into two classes: class I members possess an intact C block and LZL motif, whereas class II proteins retain the complete C block but show partial degeneration of the LZL motif. Some LBD proteins also contain a nuclear localisation signal, and their DNA-binding specificity is relatively flexible, enabling recognition of LBD motifs such as the consensus “LBDmotif” and CATTTAT-like sequences. Both homodimerisation and heterodimerisation are generally required for LBD proteins to exert regulatory activity [49]. In S. miltiorrhiza, 51 LBD genes (SmLBDs) have been identified [50].

4.2. Expression Patterns and Subcellular Localisation of Transcription Factors

Based on the 80 S. miltiorrhiza TFs summarised in Table 1, most genes are expressed in roots, stems, leaves, and flowers, but they show clear tissue-preferential patterns. Roots and root-associated tissues represent the most frequent expression maxima, with many genes enriched in the periderm, phloem, and xylem, where secondary metabolism is particularly active. Leaf-preferred, stem-preferred, and fibrous/lateral root–preferred expression patterns are also observed. For example, SmMYB52, SmMYB111, SmbHLH124, SmbHLH148, and SmTGA5 are predominantly expressed in roots or root systems [51,52,53,54,55], whereas SmHY5 and SmbHLH130 accumulate at higher levels in leaves [56,57]. SmMYB4, SmMYB39, and SmERF1L1 show relatively higher expression in stems [58,59]. Overall, this spatial expression landscape is consistent with the predominant accumulation of salvianolic acids in the roots of S. miltiorrhiza.

With respect to subcellular localisation, the majority of TFs are targeted to the nucleus. Among the reported entries, 74.4% are exclusively localised in the nucleus, and an additional 8.5% are detected mainly in the nucleus but also in other compartments, resulting in 82.9% of TFs showing nucleus-associated localisation. The remaining factors are either unreported or not clearly defined. Examples of TFs localised solely in the nucleus include SmMYB71, SmTCP6, SmMYB98, SmbHLH124, and SmWRKY54 [9,46,53,60,61]. Dual localisation most commonly appears as “nucleus + cytoplasm” or “nucleus + plasma membrane,” as reported for SmMYB9a, SmGRAS/DELLA proteins (SmGRAS16/19/20/21), SmMYB52, and SmbHLH53 [51,62,63,64]. This distribution is consistent with the role of TFs as transcriptional regulators. For the smaller group showing dual localisation, signal-dependent nucleo–cytoplasmic shuttling, recruitment to membrane-associated complexes, or specific protein–protein interactions may account for their subcellular patterns.

4.3. Hormone- and Stress-Induced Signalling in the Regulation of Salvianolic Acid Biosynthesis

AP2/ERF, bHLH, MYB, bZIP, WRKY, and GRAS TF families in S. miltiorrhiza show strong responsiveness to multiple elicitors, including methyl jasmonate (MeJA), JA, salicylic acid (SA), abscisic acid (ABA), and gibberellic acid (GA), and many of these factors modulate salvianolic acid biosynthesis. Overall, JA/MeJA act as the predominant upstream signals, followed by SA and ABA, whereas GA elicits detectable transcriptional responses in a subset of genes. JA/MeJA-responsive regulation is mainly associated with MYB, bHLH, WRKY, and GRAS factors, such as SmMYB1/2/52, SmMYC2/2b, and SmWRKY14/61 [19,51,65,66,67,68]. ABA-related responses are largely mediated by bZIP and TCP proteins, including SmbZIP1/3/38, SmAREB1 (identical to SmbZIP38), and SmTCP17/21/19 [46,69,70,71,72]. SA- and ethylene-responsive regulation is frequently observed among WRKY and AP2/ERF members, exemplified by SmWRKY54 and SmERF115/2/1L1 [59,61,73,74]. In addition, GA- or GA3-induced responses are centred on GRAS (DELLA) proteins such as SmGRAS16/19/20/21 [63] and are also detected in a limited number of MYB and bHLH TFs, including SmMYB71/111 and SmbHLH130/148/53 [52,54,57,60,64].

Table 1.

Characteristics and regulatory information of reported transcription factor family members in S. miltiorrhiza.

Table 1.

Characteristics and regulatory information of reported transcription factor family members in S. miltiorrhiza.

| TF Family | Number | Member | Regulatory Role | Inducer | Expression Pattern | Subcellular Localisation | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MYB(R2R3) | 110 | SmMYB1 | Positive | MeJA | leaf | Nucleus | [19] |

| SmMYB2 | Positive | MeJA | Root | Nucleus | [65] | ||

| SmMYB4 | Negative | MeJA, ABA, SA | Root | Nucleus | [18] | ||

| SmMYB18 | Positive | / | Root | Nucleus | [75] | ||

| SmMYB52 | Positive | MeJA, IAA | Root | Nucleus, Plasma membrane | [51] | ||

| SmMYB111 | Positive | MeJA, SA, GA | Root | Nucleus | [20,52,58,76] | ||

| SmMYB39 | Negative | MeJA | Root | Nucleus | [58,76] | ||

| SmMYB98 | Positive | / | Root | Nucleus | [9] | ||

| SmMYB9a | Negative | / | Root | Nucleus, Cytoplasm | [62] | ||

| SmMYB76 | Negative | MeJA | Root | Nucleus | [77] | ||

| SmMYB36 | Negative | / | / | Nucleus | [78,79,80] | ||

| SmMYB71 | Negative | GA3 | Root | Nucleus | [60] | ||

| SmMYB97 | Positive | MeJA | Root | Nucleus | [81] | ||

| SmPAP1 | Positive | MeJA, ABA, SA | leaf | / | [82] | ||

| SmMYB37 | Positive | MeJA | / | / | [83] | ||

| SmMYB75 | Positive | ABA, SA, GA, MeJA, ET, GA3 | leaf | Nucleus | [84] | ||

| SmMYB90 | Positive | ABA, SA, GA, MeJA, ET, GA3 | leaf | Nucleus | [84] | ||

| BHLH | 127 | SmMYC2 | Positive | MeJA | Root | Nucleus | [20,85,86,87] |

| SmbHLH3 | Negative | / | Root | Nucleus | [88] | ||

| SmbHLH92 | Negative | / | Root | Nucleus | [89] | ||

| SmJRB1 | Positive | MeJA | leaf | Nucleus | [90] | ||

| SmbHLH148 | Positive | MeJA, ABA, GA | Root | Nucleus | [54] | ||

| SmbHLH60 | Negative | MeJA | Root | Nucleus | [85] | ||

| SmbHLH59 | Positive | MeJA | Root | Nucleus | [91] | ||

| SmbHLH51 | Positive | MeJA | Root | Nucleus | [52,58,76] | ||

| SmbHLH37 | Negative | MeJA | leaf | Nucleus | [86] | ||

| SmbHLH53 | - | MeJA, ABA, IAA, GA3 | leaf | Nucleus, Plasma membrane | [64] | ||

| SmbHLH125 | - | / | Root | Nucleus | [92] | ||

| SmbHLH7 | Positive | MeJA, ABA, SA, GA | Root | Nucleus | [57] | ||

| SmbHLH130 | Positive | MeJA, ABA, GA | leaf | Nucleus | [57] | ||

| SmMYC2b | Positive | MeJA | Root | Nucleus | [67] | ||

| SmbHLH124 | Negative | / | Stem | Nucleus | [53] | ||

| AP2/ERF | 170 | Sm008 | / | / | Root | / | [32] |

| Sm166 | / | / | / | / | [32] | ||

| SmERF115 | Positive | MeJA, ET, SA | leaf | Nucleus | [73] | ||

| SmERF2 | Negative | ET, SA, MeJA | Root | Nucleus | [74] | ||

| SmO3L3 | Positive | MeJA | Root | Nucleus | [74] | ||

| SmERF1L1 | Negative | MeJA, ET, SA | leaf | Nucleus | [59] | ||

| SmERF005 | Negative | MeJA, ABA, GA | / | Nucleus | [93] | ||

| TRINITY_DN14213_c0_g1 | / | / | / | / | [94] | ||

| BZIP | 70 | SmbZIP1 | Positive | ABA | Periderm | Nucleus | [69] |

| SmbZIP2 | Negative | ABA | Root | Nucleus | [95] | ||

| SmbZIP3 | Positive | ABA | / | Nucleus | [70] | ||

| SmHY5 | Positive | IAA | Root | Nucleus | [56] | ||

| SmbZIP38 | Positive | ABA | / | / | [71] | ||

| SmTGA2 | Positive | SA, GA | Root | Nucleus | [96] | ||

| SmTGA5 | Positive | SA, GA | Root | Nucleus | [55] | ||

| SmAREB1 | Positive | ABA | Root | Nucleus | [72] | ||

| SmbZIP6 | Positive | / | / | / | [97] | ||

| SmbZIP18 | Positive | / | / | / | [97] | ||

| SmbZIP19 | Positive | / | / | / | [97] | ||

| WRKY | 69 | SmWRKY34 | Negative | ABA | Root | Nucleus | [70] |

| SmWRKY61 | Positive | / | Stem | / | [68] | ||

| SmWRKY20 | Positive | MeJA, ET, ABA, SA | leaf | Nucleus | [98] | ||

| SmWRKY14 | Positive | MeJA | Root | Nucleus | [99] | ||

| SmWRKY9 | - | ET, ABA, SA, MeJA | Root | Nucleus | [100] | ||

| SmWRKY54 | Negative | ET, ABA, SA, MeJA, GA3 | leaf | Nucleus | [61] | ||

| GRAS | 34 | SmGRAS1 | Negative | MeJA, ABA, SA, GA | Root | Nucleus | [101,102] |

| SmGRAS2 | Negative | MeJA, ABA, GA | Root | Nucleus | [101,102] | ||

| SmGRAS3 | Negative | MeJA, ABA, SA, GA | Root | Nucleus | [101] | ||

| SmGRAS4 | Positive | MeJA, SA, GA | Root | Nucleus | [101] | ||

| SmGRAS5 | Negative | ABA, GA | Root | Nucleus | [101] | ||

| SmGRAS21 | Positive | MeJA, GA3 | Root | Nucleus, Cytoplasm | [63] | ||

| SmGRAS20 | Positive | MeJA, GA3 | Root | Nucleus, Cytoplasm | [63] | ||

| SmGRAS19 | Positive | MeJA, GA3 | Root | Nucleus, Cytoplasm | [63] | ||

| SmGRAS16 | Positive | MeJA, GA3 | Root | Nucleus, Cytoplasm | [63] | ||

| NAC | 84 | SmNAC36 | Positive | / | Root | Nucleus | [75] |

| SmNAC1 | Positive | / | / | / | [103] | ||

| SmNAC2 | Negative | / | Root | / | [104] | ||

| SmNAC3 | Negative | / | Root | / | [104] | ||

| LBD | 51 | LBD50 | Negative | MeJA | Root | / | [50] |

| LBD44 | Negative | MeJA | Root | Nucleus | [105] | ||

| LBD23 | Negative | MeJA | Root | Nucleus | [106] | ||

| LBD16 | Negative | MeJA | Root | Nucleus | [106] | ||

| SPL | 11 | SmSPL2 | Negative | / | Flower | Nucleus | [107] |

| SmSPL6 | Positive | MeJA, GA, ABA, IAA | leaf | Nucleus | [108] | ||

| SmSPL7 | Negative | MeJA, ABA, IAA | leaf | Nucleus | [109] | ||

| TCP | 33 | SmTCP17 | Positive | ABA | Root | Nucleus | [46] |

| SmTCP21 | Positive | ABA | Root | Nucleus | [46] | ||

| SmTCP6 | Negative | ABA | Root | Nucleus | [46] | ||

| SmTCP1 | - | ABA | Root | Nucleus | [46] | ||

| SmTCP19 | - | ABA | Root | Nucleus | [46] |

Beyond phytohormonal regulation, salvianolic acid biosynthesis is also responsive to diverse environmental challenges that activate distinct signalling pathways converging on a shared transcriptional network. Abiotic stresses such as UV-B irradiation induce SmNAC1, thereby activating upstream pathway genes and promoting phenolic acid accumulation, which is consistent with an antioxidant defence response [107]. Drought stress, largely mediated by ABA signalling, engages transcription factors including SmWRKY34 and SmbZIP38 to fine-tune the expression of biosynthetic genes, thereby reshaping pathway flux under water-deficit conditions [70,71]. Biotic challenges and elicitors typically activate jasmonate (JA)-associated signalling. In this context, the core JA regulator SmMYC2, together with interacting partners such as SmMYB factors, can upregulate phenolic acid biosynthetic genes, potentially strengthening chemical defence capacity [19,87]. This induction is further modulated by repressor proteins such as SmJAZ1 and SmJAZ8, illustrating how stress cues are gated and integrated at the transcriptional level [58,90]. Collectively, these examples indicate that the salvianolic acid regulatory network functions as an integrative hub, translating both abiotic and biotic-associated stimuli into tailored adjustments of phenolic metabolism, enabling dynamic optimisation of specialised metabolite profiles under fluctuating environments.

5. Transcriptional Regulation of Salvianolic Acids by Transcription Factors

The transcriptional regulation of salvianolic acid biosynthesis involves multiple TF families, within which individual members can function as activators, repressors, or context-dependent regulators. This functional divergence often reflects evolutionary specialisation into distinct clades or subfamilies. Mechanistically, it is shaped by differences in transcriptional complex assembly, target gene selection across key enzymatic nodes, and tissue- or condition-specific expression. The following sections discuss the major TF families using this integrative framework, with an emphasis on positive regulation, negative regulation, and complex-mediated regulation. This mechanistic understanding is essential for the rational selection and stacking of TFs to achieve predictable metabolic engineering outcomes.

Unless otherwise specified, functional evidence for the TFs summarised below was mainly obtained from S. miltiorrhiza hairy-root cultures and/or root tissues, where phenolic acids are typically enriched; TF–target relationships were further supported by promoter-binding and transient expression assays. Information on tissue/organ expression patterns is summarised in Table 1.

5.1. Regulatory Roles of MYB Transcription Factors in Salvianolic Acid Biosynthesis

Several R2R3-MYB TFs in S. miltiorrhiza function as transcriptional activators that directly upregulate key enzymes in both the phenylpropanoid and tyrosine-derived branches, thereby significantly enhancing salvianolic acid accumulation. SmMYB1 is induced by MeJA and activates multiple pathway genes, including PAL1, C4H1, 4CL1, TAT1, HPPR1, RAS1, and CYP98A14, which results in increased salvianolic acid production. In SmMYB1-overexpressing hairy roots, total salvianolic acids reach approximately twice the level of the control, whereas expression of a dominant repressor version (SmMYB1-SRDX) reduces the content to 57.3% of the control [19]. Overexpression of SmPAP1, a homologue of AtPAP1, also strongly stimulates the pathway. Transgenic plants exhibit 1.52–1.95-fold higher RA and 1.39–1.88-fold higher Sal B than the wild type, accompanied by upregulation of PAL, C4H, 4CL, and other structural genes, which indicates strong activation of the phenylpropanoid route [82]. In transgenic hairy roots, SmMYB2 overexpression increases total phenolic acids to nearly threefold that of the control, whereas suppression of SmMYB2 results in reduced levels [65]. SmMYB18 primarily targets the tyrosine-derived branch. In overexpression lines, SmTAT2 transcripts increase by 2.16–12.58-fold, with RA and Sal B levels elevated by 2.06–2.68-fold and 1.64–2.36-fold, respectively, whereas knockout of SmMYB18 causes significant decreases in these metabolites [75].

Consistent pro-accumulation effects are also reported for SmMYB52, SmMYB97, SmMYB98, SmMYB75, SmMYB90, and SmMYB111. In SmMYB52-overexpressing lines, Sal B increases by 2.1–2.2-fold, and both total phenolics and RA are significantly elevated, whereas RNAi-mediated silencing reduces Sal B by 4.5–5.5-fold [51]. SmMYB97 overexpression results in 1.6–2.0-fold higher RA and 1.3–2.5-fold higher Sal B [81], and SmMYB98 overexpression results in up to 1.5-fold increases in total RA + Sal B, which decline substantially in knockout backgrounds [9]. SmMYB75 and SmMYB90 are MeJA-responsive R2R3-MYB factors that positively regulate salvianolic acid accumulation. Overexpression of either TF enhances expression of key pathway genes such as Sm4CL1, SmTAT, SmRAS, and SmCYP98A14, whereas repression of SmMYB75 or SmMYB90 in hairy roots significantly decreases total salvianolic acid content [84]. SmMYB37 is a target of miR396b and binds to the promoter of the phenylpropanoid gene C4H. Overexpression of miR396b markedly reduces SmMYB37 transcript levels, and total phenolic acids decline to 72.1% of the control, which suggests a negative correlation and implies that elevated SmMYB37 expression promotes phenolic acid accumulation [83]. Among these activators, SmMYB111 shows a strong effect. In SmMYB111-overexpressing hairy roots, RA content increases by approximately 2.19-fold, and Sal B reaches up to 4.65-fold of the wild-type level [20,52,58].

Substantial evidence also indicates that several MYB TFs act as negative regulators of salvianolic acid biosynthesis. SmMYB4 binds to the promoters of SmPAL, SmC4H, and SmTAT1 and represses their transcription. In SmMYB4-overexpressing plants, RA and Sal B contents decrease to 56.6% and 57.6% of wild-type levels, respectively, whereas in RNAi lines total phenolic acids increase to approximately 1.8-fold of the wild type [18]. When CA, RA, and Sal B were quantified in SmMYB9a-overexpressing and -silenced hairy roots, little change was detected in overexpression lines, whereas in RNAi lines CA, RA, and Sal B increase to 1.9-, 1.47-, and 2.4-fold of wild-type levels, respectively [62]. Overexpression of SmMYB76 reduces total phenolic acid levels by 39–69%, whereas knockout of SmMYB76 results in a 47–132% increase compared with the control [77]. Similarly, loss of SmMYB71 function raises RA and Sal B contents to 1.5- and 2-fold of wild-type levels, respectively, whereas SmMYB71 overexpression reduces RA to 30% and Sal B to 60% of the wild type, which demonstrates a strong negative regulatory role [60]. SmMYB36 represses transcription of the key phenolic acid biosynthetic genes SmRAS and SmGAPC by directly binding to MYB recognition elements in their promoters and simultaneously downregulates the upstream TF SmERF115, thereby restricting accumulation of downstream products. In SmMYB36-overexpressing hairy roots, RA and Sal B contents decrease by more than 50%, whereas in SmMYB36-SRDX dominant-interference lines both metabolites increase by more than 1.5-fold, consistent with the observed gene expression changes [78,79].

SmMYB39 not only represses multiple pathway genes but also disrupts assembly and activity of the MYB–bHLH–WD40 regulatory complex. SmMYB39 interacts with all components of the SmMYB111–SmbHLH51–SmTTG1 complex, which blocks complex formation, and directly suppresses transcriptional activation of SmC4H1 and other targets by SmbHLH51. Therefore, SmMYB39 exerts negative regulation at both transcriptional and protein–protein interaction levels. In SmMYB39-overexpressing hairy roots, RA and Sal B contents decline to approximately 5% and 22.6% of wild-type levels, respectively, whereas RNAi-mediated silencing increases RA and Sal B to approximately 3.81- and 4.23-fold of the wild type. SmMYB39 also interacts with the jasmonate signalling repressor SmJAZ1, forming a higher-order negative regulatory module within the JA–TF network [58].

SmMYB111 does not function alone but cooperates with SmbHLH51 and SmTTG1 to form an MYB–bHLH–WD40 (MBW) ternary complex that strongly enhances transcriptional activation of target genes [52,110]. Activity of SmMYB111 is further regulated at multiple levels. The microRNA Smi-miR858a targets SmMYB111 transcripts for cleavage, which reduces its expression and downregulates downstream pathway genes, leading to decreased phenolic acid accumulation. In Smi-miR858a-overexpressing plants, Sal B content is reduced by 87.2% relative to the wild type [111]. SmMYB76 interacts with the jasmonate signalling repressor SmJAZ9, and together they strengthen transcriptional repression of downstream genes. SmJAZ9 promotes SmMYB76 expression and enhances its repressive activity, whereas MeJA treatment induces SmJAZ9 degradation, which alleviates SmMYB76-mediated repression of SmPAL, Sm4CL2, and SmRAS1 and releases inhibition of phenolic acid biosynthesis [77]. SmMYB36 interacts with SmCSN5, which stabilises SmMYB36 by inhibiting ubiquitin-mediated degradation and thereby reinforces its suppressive effect on phenolic acid production [80]. When SmMYB36 is fused to the strong activation domain VP16 to generate SmMYB36–VP16, its ability to activate SmRAS is greatly enhanced, and RA content reaches 5.05-fold that of the control [112]. SmMYB1 can also form a complex with SmMYC2. Dual-luciferase assays show that combined action of SmMYB1 and SmMYC2 activates CYP98A14 more strongly than SmMYB1 alone, which indicates that their cooperation substantially increases phenolic acid biosynthetic activity [19].

5.2. Regulatory Roles of bHLH Transcription Factors in Salvianolic Acid Biosynthesis

bHLH TFs participate in both positive and negative regulation of phenolic acid biosynthesis in S. miltiorrhiza. On the positive side, SmMYC2/SmMYC2b, SmJRB1, SmbHLH59, SmbHLH51, SmbHLH7, SmbHLH130, and SmbHLH148 promote salvianolic acid accumulation. SmMYC2 is strongly induced by MeJA and binds E/G-box elements in target promoters to activate key enzymes such as SmPAL, SmTAT1, and SmCYP98A14, thereby enhancing synthesis of RA, Sal B, and related metabolites. In SmMYC2-overexpressing plants, root Sal B content increases by approximately 1.88-fold relative to the control [85,87], whereas RNAi knockdown of SmMYC2b reduces RA and Sal B to 0.09- and 0.05-fold of control levels, respectively [67]. SmJRB1 is rapidly induced by MeJA, directly targets a G-box in the RAS1 promoter, and coordinately upregulates RAS1, CYP98A14, and multiple upstream genes, including PAL, 4CL, TAT, and HPPR, which promotes RA and Sal B accumulation [90]. SmbHLH59 binds promoter elements in both the phenylalanine- and tyrosine-derived precursor branches and at their convergence node to enhance transcriptional activity; its function is repressed by SmJAZ1 and SmJAZ8, representing a canonical MeJA–JAZ–bHLH regulatory module [91]. SmbHLH51 increases RA and Sal B production by directly or indirectly activating key pathway genes and forms an MBW complex with SmMYB111 and SmTTG1 that further amplifies transcriptional output [76]. In addition, SmbHLH7 and SmbHLH130 bind G-box motifs in the promoters of C4H1, TAT, HPPR, and CYP98A14 to activate transcription, leading to significant increases in RA and Sal B levels in overexpressing hairy roots [57]. SmbHLH148 is strongly induced by ABA, and its overexpression causes sustained upregulation of most genes in both the phenolic acid and tanshinone pathways. In the OEbHLH148-3 line, Sal B content reaches approximately 5.99-fold that of the control [54].

Several bHLH TFs, including SmbHLH3, SmbHLH60, SmbHLH92, SmbHLH37, and SmbHLH124, act as negative regulators of phenolic acid biosynthesis. SmbHLH3 directly binds G-box motifs in the SmTAT and SmHPPR promoters to repress transcription; in SmbHLH3-overexpressing lines, RA and Sal B levels decrease to approximately 50% and 38% of the control, respectively [88]. Overexpression of SmbHLH60 similarly reduces phenolic acid accumulation, whereas CRISPR/Cas9 knockout of SmbHLH60 results in a marked increase in phenolic acids. Notably, SmbHLH60 transcript levels are rapidly downregulated after MeJA treatment, consistent with a negative feedback mechanism that attenuates excessive JA signalling [85]. RNAi-mediated suppression of SmbHLH92 upregulates PAL1, CYP98A14, and other pathway genes and increases phenolic acid accumulation, indicating a repressive role for SmbHLH92 [89]. SmbHLH37 binds the promoters of SmTAT1 and SmPAL1 and counteracts the activating effect of SmMYC2; in SmbHLH37-overexpressing material, Sal B is reduced by approximately 1.6–1.8-fold and RA by approximately 1.7–2.0-fold, accompanied by broad downregulation of phenolic acid pathway genes [86]. Overexpression of SmbHLH124 causes coordinated repression of multiple pathway nodes, including PAL3, 4CL3/4/9, RAS1, and HPPR3, which leads to substantial decreases in RA and Sal B [53].

Some bHLH members display context-dependent or bidirectional effects. For example, SmbHLH53 represses SmTAT1, SmPAL1, and SmC4H1 while activating Sm4CL9. In the corresponding transgenic lines, opposing changes in upstream and downstream genes largely offset each other, resulting in no significant difference in total RA and Sal B content relative to the control [64]. SmbHLH125 binds the Sm4CL3 promoter and negatively regulates its expression. Gene editing of SmbHLH125 produces a differential metabolic response, with decreased RA and increased Sal B levels, which suggests branch-selective control over metabolic flux partitioning [92].

5.3. Regulatory Roles of ERF Transcription Factors in Salvianolic Acid Biosynthesis

SmERF115 is a jasmonate-responsive TF. Its overexpression in S. miltiorrhiza hairy roots significantly upregulates SmRAS1, accompanied by increased expression of PAL3, 4CL5, TAT3, and RAS4, and results in an average increase of approximately 1.43-fold in Sal B, whereas RA and Sal A show no significant changes. Conversely, in SmERF115-RNAi lines, Sal B levels decline to approximately 50% of those in the control [73]. Another ERF member, SmO3L3, a close homologue of A. thaliana ERF113, similarly enhances phenolic acid accumulation when overexpressed in hairy roots, with the best line reaching 1.86-fold higher total salvianolic acids than the control. In SmO3L3 RNAi lines, salvianolic acid content averages 73% of control levels [74].

Some AP2/ERF members in S. miltiorrhiza function as repressors of phenolic acid accumulation through direct inhibition of key biosynthetic genes or competition for metabolic flux. SmERF005 is responsive to both ABA and MeJA. Under 50 μM ABA treatment, its transcript level declines rapidly, reaching a minimum of 5.79% at 12 h. Functional assays show that SmERF005 binds the GCC-box element in the SmCYP98A14 promoter and reduces promoter activity to 29% of the control in dual-luciferase assays. Because biomass of SmERF005-overexpressing lines was insufficient, metabolite levels were not quantified; however, in SmERF005 RNAi hairy roots, total phenolic acids increase by approximately 28% relative to the control [93]. SmERF1L1 is a JA-sensitive AP2/ERF factor that is rapidly induced by MeJA and related elicitors. Overexpression of SmERF1L1 in hairy roots reduces total phenolic acids to approximately 66% of control levels, with significant decreases in RA and Sal A. Most core phenolic acid biosynthetic genes show no obvious transcriptional changes, whereas SmHPPD is differentially expressed, consistent with its position at a pathway branch point [59]. SmERF2 also acts as a negative regulator of salvianolic acid biosynthesis. Overexpression reduces total salvianolic acids to approximately 66% of control levels, whereas SmERF2 RNAi lines show contents comparable to the control, likely reflecting functional redundancy among AP2/ERF members [74].

Reports describing ERF TFs that directly regulate salvianolic acid biosynthesis in S. miltiorrhiza remain limited. Based on available expression profiles and functional assays, three additional TFs have been proposed as candidates in this pathway. quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT–PCR) analysis indicates that Sm008 and Sm166 show highest expression in the phloem and xylem of roots, with tissue-specific patterns closely matching that of SmRAS1. They also display strong co-expression with SmRAS, which suggests a positive association with salvianolic acid biosynthesis [32]. In contrast, the drought-induced DREB-type factor TRINITY_DN14213_c0_g1 has direct functional support. Dual-luciferase assays show significant transactivation of the SmC4H and SmRAS promoters, indicating that this factor may act as a positive regulator of salvianolic acid production [94].

5.4. Regulatory Roles of WRKY Transcription Factors in Salvianolic Acid Biosynthesis

SmWRKY40, identified from a Sichuan ecotype of S. miltiorrhiza, is a core component of the phenolic acid biosynthetic gene cluster and functions as an important positive regulator of salvianolic acid biosynthesis. Overexpression of SmWRKY40 in hairy roots significantly increases RA and Sal B levels, accompanied by coordinated upregulation of key pathway genes, including SmTAT2, SmHPPR, SmRAS, and SmCYP98A14. Conversely, CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knockout of SmWRKY40 causes marked reductions in RA and Sal B, together with inhibited root growth and softened root texture. This regulatory function appears conserved across species. In A. thaliana, SmWRKY40 overexpression or complementation of the wrky40 mutant promotes accumulation of phenolic acid–related metabolites [113].

SmWRKY20 was identified from YE/Ag+-treated transcriptomes as another WRKY factor regulating salvianolic acid biosynthesis. In SmWRKY20-overexpressing lines, Sal B increases by 13–40% and total salvianolic acids by 16–40%, whereas in RNAi lines these values decrease by 15–40% and 8–37%, respectively, which indicates a positive regulatory role. SmWRKY20 shows no autoactivation activity in yeast, which suggests that cofactors may be required in planta to achieve full transcriptional activity [98]. Jasmonate signalling studies further show that SmWRKY14 directly binds and activates the promoters of SmPAL1, SmC4H1, SmTAT1, SmHPPR, and SmRAS1, which leads to substantial increases in phenolic acid content. Overexpression of SmWRKY14 in hairy roots raises total phenolic acids and Sal B to approximately 1.46-fold and 2.99-fold of control levels, respectively. SmWRKY14 also participates in jasmonate signalling through interaction with JAZ proteins, forming a hormone-responsive regulatory node that connects defence signalling with secondary metabolism [99]. Although SmWRKY61 was initially characterised for its role in tanshinone biosynthesis, its overexpression in hairy roots also causes a pronounced increase in RA to 3.33-fold of control levels, whereas Sal B and CA remain unchanged. Consistently, RA-branch genes such as Sm4CL3, SmTAT1, and SmCYP98A14 are upregulated, which indicates that SmWRKY61 preferentially promotes the RA branch of the phenolic acid pathway [68].

In contrast, SmWRKY34, a subgroup IIa WRKY TF induced by ABA, functions as a strong repressor of phenolic acid accumulation. Overexpression of SmWRKY34 reduces total phenolic acids to an average of 22.7% of control levels, with some lines declining to 6.3%, whereas CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knockout increases total phenolic acids to approximately 1.5-fold of the control [70]. SmWRKY54 also acts as a negative regulator. Its overexpression in hairy roots decreases total salvianolic acids to 29.1% of control levels, while RNAi-mediated suppression elevates them to approximately 1.2-fold relative to the control [61]. Mechanistic evidence suggests that SmWRKY54 redirects metabolic flux away from phenolic acid biosynthesis by downregulating Sm4CL1 and upregulating SmHPPD, which limits salvianolic acid accumulation.

SmWRKY9 shows a more complex regulatory profile. Overexpression of SmWRKY9 increases RA content to 2.22-fold of control levels, whereas expression of a dominant repressor (SmWRKY9-SRDX) markedly reduces RA. SmWRKY9 directly binds to and activates the promoters of SmRAS1 and SmCYP98A14 and also upregulates SmPAL3 and Sm4CL2/3/8, thereby promoting RA biosynthesis. Notably, SmWRKY9 shows a negative association with Sal B. Both overexpression and SRDX lines exhibit lower Sal B levels than the control, which suggests that SmWRKY9 may restrict or redirect metabolic flux at the step converting RA to Sal B [100].

5.5. Regulatory Roles of bZIP Transcription Factors in Salvianolic Acid Biosynthesis

In S. miltiorrhiza, several bZIP TFs positively regulate salvianolic acid biosynthesis and often function as integrative nodes that connect hormone and light signalling with pathway gene expression. Overexpression of SmbZIP1 in hairy roots increases C4H1 transcript levels by approximately 3.5-fold and HPPR by approximately 2.5-fold, which results in a substantial rise in total phenolic acids. In the strongest line (OE-4), total salvianolic acids reach approximately 4.1-fold of the control, whereas CRISPR/Cas9 knockout of SmbZIP1 significantly decreases Sal B, with the lowest line retaining only 53.1% of control levels [69]. Within the SA signalling pathway, SmTGA2 shows strong positive effects on salvianolic acid production. In SmTGA2-overexpressing hairy roots, RA and Sal B reach 2.02- and 1.29-fold of wild-type levels, respectively, whereas antisense suppression reduces them to 0.82- and 0.56-fold of the wild type. At the mechanistic level, SmTGA2 upregulates SmPAL1, SmTAT1, SmRAS1, SmCYP98A14, SmC4H1, and SmHPPR1, with SmCYP98A14 showing the strongest induction (3.45–9.56-fold). SmTGA2 also interacts specifically with the SA receptor SmNPR1, forming an SA–SmNPR1–SmTGA2 module that promotes salvianolic acid biosynthesis [96].

The light signalling factor SmHY5 also positively regulates phenolic acid accumulation. In SmHY5-overexpressing plants, RA and Sal B increase significantly, reaching up to 1.81- and 1.39-fold of wild-type levels, respectively. In RNAi lines, both metabolites decrease markedly. Notably, Sal A in the RNAi-18 line increases to 2.67-fold of the wild type, which suggests redistribution of metabolic flux through alternative branches or bypass routes [56]. As an ABA-responsive bZIP, SmAREB1 forms homodimers and binds ABRE cis-elements in the SmTAT promoter to directly activate transcription, while also upregulating SmRAS, SmPAL1, and Sm4CL1. These coordinated changes increase channelling of precursors towards salvianolic acids. In SmAREB1-overexpressing hairy roots, RA, Sal B, and total salvianolic acids reach 1.16-, 1.22-, and 1.19-fold of control levels, respectively, whereas in RNAi lines they decline to 71%, 86%, and 75% of the control [71]. Another family member, SmbZIP3, directly recognises two ABRE motifs in the SmTAT promoter and activates this gene. In SmbZIP3-overexpressing lines, PAL and TAT transcripts increase, whereas RAS and CYP98A14 decrease; nevertheless, overall metabolic flux shifts towards RA and Sal B, and total phenolic acids average approximately 1.59-fold of the control. These results indicate that SmbZIP3 enhances early steps in the tyrosine-derived branch to increase precursor supply despite negative feedback at later modification steps [69]. At the level of hormone–kinase–TF crosstalk, SmSnRK2.6 and SmAREB1 form an ABA-activated regulatory module. Overexpression of either component increases RA and Sal B levels, which highlights a tightly coupled ABA–SnRK2–bZIP cascade that promotes salvianolic acid biosynthesis [72].

Among bZIP TFs that repress salvianolic acid biosynthesis, SmbZIP2 has the most direct experimental support. In SmbZIP2-overexpressing hairy roots, total salvianolic acids average only 54% of the empty-vector control, whereas CRISPR/Cas9-induced mutations in SmbZIP2 increase salvianolic acid levels by 23–53% relative to the control. Mechanistic analyses show that SmbZIP2 represses transcription of PAL, a key rate-limiting enzyme in the pathway [95].

Some bZIP TFs remodel salvianolic acid flux through more complex, indirect mechanisms that include signalling integration, protein–protein interactions, and competition between metabolic branches. First, within the SA pathway, SmTGA5 activates SmTAT1 and promotes salvianolic acid accumulation, but the SmNPR4–SmTGA5 module imposes an upper limit on this response under SA induction. In SmNPR4-overexpressing lines, Sal B levels decrease to 46–56% of the control, whereas in SmNPR4-RNAi lines the SA-induced increases in RA and Sal B reach 1.19- and 1.23-fold of the control, respectively. These findings indicate that receptor–TF pairing provides threshold control over SA-mediated stimulation of phenolic acid biosynthesis [55]. Second, SmbZIP1 displays an antagonistic regulatory pattern across the two major secondary metabolic pathways. It upregulates C4H1 and HPPR, which strongly increases salvianolic acid accumulation, while binding the G-box in the geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase (GGPPS) promoter to repress its transcription. This repression results in up to 95.3% reduction in total tanshinones in overexpression lines, with significant increases observed in knockout lines. These results indicate that SmbZIP1 contributes to metabolic partitioning between competing branches and indirectly favours synthesis of water-soluble salvianolic acids [69].

Third, PAL, a pivotal enzyme in the phenolic acid pathway, is transcriptionally repressed by SmbZIP2. SmbZIP2 physically interacts with SmSnRK2.6, which suggests that SmSnRK2.6 may modulate SmbZIP2 activity through phosphorylation [95]. In addition, several other bZIP proteins, including bZIP6, bZIP18, and bZIP19, bind promoters of pathway genes, although their metabolic roles remain incompletely defined. Yeast one-hybrid and electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) assays show specific binding of bZIP18 to the Sm4CL2 promoter and of bZIP6 and bZIP19 to the SmTAT promoter, which suggests that these factors may influence phenolic acid biosynthesis by acting at key regulatory nodes such as 4CL and TAT [97].

5.6. Regulatory Roles of GRAS Transcription Factors in Salvianolic Acid Biosynthesis

Overexpression of SmGRAS4 significantly upregulates key genes in the salvianolic acid biosynthetic pathway, including SmC4H1, Sm4CL1, and SmCYP98A14, which leads to increased phenolic acid accumulation. In SmGRAS4-overexpressing hairy roots, RA reaches 1.19–1.58-fold and Sal B 1.13–1.29-fold of the empty-vector control, whereas antisense lines show reduced levels of both metabolites. In addition, interference lines targeting the four members of the SmDELLA subfamily (SmDELLA1–4) all show lower total phenolic acid contents than the control, with SmDELLA1 and SmDELLA3 exhibiting particularly strong reductions to 34% and 37% of control levels, respectively. These results indicate that SmDELLA genes act as positive regulators of total phenolic acid accumulation in S. miltiorrhiza [63].

In contrast, SmGRAS1, SmGRAS2, SmGRAS3, and SmGRAS5 function as negative regulators of phenolic acid biosynthesis in S. miltiorrhiza. Overexpression of these TFs markedly downregulates expression of key genes in the salvianolic acid pathway, which results in pronounced decreases in metabolite accumulation. RA levels decline to 0.68–0.83-fold and Sal B to 0.42–0.89-fold of the empty-vector control. In antisense lines, both metabolites increase significantly. For example, RA in SmGRAS3 antisense lines reaches up to 1.63-fold of the control, which further supports the repressive roles of these GRAS factors in phenolic acid production [101,102].

5.7. Regulatory Roles of Other Transcription Factor Families in Salvianolic Acid Biosynthesis

In addition to the TF families described above, several regulators of salvianolic acid biosynthesis belong to the NAC, LBD, SPL, and TCP families.

SmNAC36 binds ABRE elements in the promoters of SmMYB18 and SmTAT2 and activates their transcription. SmMYB18 subsequently recognises an MBS motif in the SmTAT2 promoter and enhances its transcription, which increases activity of the tyrosine-branch enzyme TAT2 and markedly elevates RA and Sal B accumulation. In SmNAC36-overexpressing hairy roots, RA increases by 2.51–3.66-fold and Sal B by 2.72–7.02-fold relative to the control [75]. ultraviolet B (UV-B)–induced SmNAC1 acts as an upstream regulator that directly binds and activates CATGTG/CATGTC motifs in the PAL3 and TAT3 promoters. This activation upregulates PAL3, TAT3, and HPPR3, enhances PAL and TAT enzyme activities, and results in significant increases in RA and Sal B in overexpression lines, with corresponding decreases in RNAi lines [103]. Overexpression of SmNAC2 significantly elevates RA content, whereas its silencing markedly increases Sal B to 2.43–3.21-fold of wild-type levels. At the transcriptional level, SmNAC2 overexpression upregulates upstream 4CL and TAT transcripts, whereas RNAi lines show further induction of PAL1, 4CL, TAT, and CYP98A14. By contrast, SmNAC3 overexpression reduces both RA and Sal B, whereas SmNAC3 silencing increases their levels. SmNAC3 primarily affects C4H expression, and its RNAi also upregulates PAL2, which indicates that SmNAC3 represses the upstream phenylpropanoid pathway [104].

SmLBD50 overexpression markedly reduces total phenolic acids and RA in S. miltiorrhiza. Mechanistically, SmLBD50 downregulates multiple genes in both the phenylpropanoid branch (PAL1/3, C4H1, 4CL2/3) and the tyrosine-derived branch (TAT1/3, HPPR1), and simultaneously represses downstream SmRAS and CYP98A14, thereby inhibiting phenolic acid biosynthesis. In SmLBD23-overexpressing lines, root RA content decreases to 21–51% of the control, whereas in SmLBD16 RNAi roots RA levels increase to 1.46–1.91-fold of the control [106]. SmLBD44 also acts as a negative regulator of total phenolic acid accumulation. In overexpression lines, total phenolic acids decrease to approximately 52–84% of control levels, whereas in RNAi lines they increase to 1.28–1.51-fold. Bimolecular fluorescence complementation assays show that SmLBD44 interacts with SmJAZ1, and transient transcription assays indicate that SmJAZ1 abolishes SmLBD44-mediated repression of the SmKSL1 promoter. These findings indicate that JAZ–LBD interactions modulate the balance between competing specialised metabolic pathways [105].

SmSPL2 represses salvianolic acid biosynthesis by downregulating multiple pathway genes across different branches, including SmTAT1, SmPAL, Sm4CL9, SmC4H1, and SmRAS2. In SmSPL2-overexpressing plants, RA and Sal B decrease markedly, with root RA reaching 59–78% and Sal B 20–36% of control levels [107]. By contrast, SmSPL6 functions as a positive regulator. In SmSPL6-overexpressing lines, both RA and Sal B increase significantly, and root Sal B reaches 5.18–8.19-fold of the control [108]. SmSPL7 shows an intermediate pattern and specifically affects the downstream branch towards Sal B. In SmSPL7-overexpressing lines, root Sal B decreases to 35–65% of control levels, whereas RA remains largely unchanged, which suggests selective regulation of flux at the RA-to-Sal B conversion step [109].

Under ABA induction, TCP family members display site-specific binding and context-dependent regulation of the promoters of the branch-specific genes SmRAS1 and SmCYP98A14 in the salvianolic acid pathway. SmTCP17 and SmTCP21 tend to activate both CYP98A14 and RAS1, whereas SmTCP6 represses RAS1. SmTCP1 and SmTCP19 activate CYP98A14 but repress RAS1, which indicates that their net effects on salvianolic acid biosynthesis depend on expression context and protein abundance. Because in planta binding and metabolic phenotypes remain incompletely resolved, these TCP factors are currently regarded as candidate regulators of salvianolic acid biosynthesis [46].

5.8. Core Regulatory Hubs and Design Principles for Metabolic Engineering

Current evidence indicates that TF-mediated control of salvianolic acid biosynthesis is organised around a limited number of recurring regulatory hubs rather than isolated single-factor effects. A JA-gated hub centred on SmMYC2 provides a switch-like mechanism in which JAZ repressors constrain transcriptional activation under basal conditions and JA-associated cues relieve repression to enable coordinated induction of biosynthetic genes. A second hub involves cooperative and antagonistic TF complexes, in which MYB–bHLH partnerships and related multi-protein assemblies shape transcriptional output through partner availability, competitive binding, and complex reconfiguration, thereby producing context-dependent activation or attenuation. A third hub reflects convergent regulation of bottleneck enzymatic nodes, with repeated TF inputs targeting PAL/C4H/4CL in the phenylpropanoid branch and TAT/HPPR/RAS/CYP98A14 in the tyrosine-derived and downstream steps, indicating that flux control is frequently executed by jointly tuning a small set of rate-limiting reactions. These hubs provide practical design principles for precision metabolic engineering, including prioritising TF combinations that coordinately control multiple bottleneck enzymes, selecting regulators that participate in cooperative complexes, and stacking activators with appropriate de-repression or feedback-gating elements to achieve predictable and stable flux rewiring.

6. Conclusions and Perspectives

This review synthesises evidence that the transcriptional regulation of salvianolic acid biosynthesis in S. miltiorrhiza is orchestrated through a limited set of core regulatory hubs rather than by isolated transcription factors. These hubs—primarily the jasmonate-gated switch centred on SmMYC2, the cooperative MYB-bHLH-WD40 complexes, and the multifactor convergent control of bottleneck enzymatic steps—collectively integrate hormonal and environmental signals to fine-tune pathway flux with spatial and temporal precision.

Elucidating these hubs shifts the focus from cataloguing individual regulators to establishing a mechanistic blueprint for rational metabolic engineering. Key design principles emerge from this blueprint, including the stacking of transcription factors that co-target multiple rate-limiting enzymes, the exploitation of cooperative transcription factor complexes for synergistic activation, and the coupling of inducible derepression mechanisms with strong activators to create dynamic, high-yield production systems. Implementing these principles in hairy-root cultures, whole-plant breeding, or synthetic microbial chassis offers a direct route to achieving stable, high-level salvianolic acid production.

Looking forward, translating this blueprint into robust breeding and bioproduction strategies will require overcoming persistent challenges. Key among these are decoding the crosstalk between regulatory hubs, resolving cell-type-specific expression patterns of hub components through spatial and single-cell omics, and balancing engineered metabolic flux with plant growth and development. Integrating the described regulatory logic with emerging technologies—such as CRISPR-based genome editing for precise hub manipulation, synthetic promoter design for context-specific expression, and computational approaches for predicting optimal transcription factor combinations—will enable the next generation of predictive, design-driven improvement of S. miltiorrhiza and other valuable medicinal plants.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.Z., B.H. and C.Z.; methodology, B.H. and M.Z.; literature search and literature review, S.C., F.P., S.T., X.W., H.L., P.W., C.Y., C.M., X.Z. and C.Z.; data curation, S.C., F.P., S.T., X.W., H.L., P.W., C.Y., C.M., X.Z. and C.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, S.C.; writing—review and editing, S.C., C.Z., B.H. and M.Z.; visualisation, S.C. and M.Z.; supervision, M.Z., B.H. and C.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Key Project at Central Government Level: The Ability Establishment of Sustainable Use for Valuable Chinese Medicine Resources (2060302), China Agriculture Research System of MOF and MARA (CARS-21), and Sichuan Province Financial Independent Innovation Project (2022ZZCX076).

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wang, L.; Ma, R.; Liu, C.; Liu, H.; Zhu, R.; Guo, S.; Tang, M.; Li, Y.; Niu, J.; Fu, M.; et al. Salvia miltiorrhiza: A Potential Red Light to the Development of Cardiovascular Diseases. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2017, 23, 1077–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Li, Y.; Xue, L.; Severino, R.P.; Gao, S.; Niu, J.; Qin, L.-P.; Zhang, D.; Brömme, D. Salvia miltiorrhiza: An Ancient Chinese Herbal Medicine as a Source for Anti-Osteoporotic Drugs. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 155, 1401–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, S.; Dai, X.; Yue, G.; Yin, J.; Xu, T.; Shi, H.; Liu, T.; Jia, Z.; Brömme, D.; et al. Salvia miltiorrhiza in Osteoporosis: A Review of Its Phytochemistry, Traditional Clinical Uses and Preclinical Studies (2014–2024). Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1483431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Xu, S.; Liu, P. Salvia miltiorrhiza Burge (Danshen): A Golden Herbal Medicine in Cardiovascular Therapeutics. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2018, 39, 802–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Zhao, X. Research Progress on Regulation of Immune Response by Tanshinones and Salvianolic Acids of Danshen (Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge). Molecules 2024, 29, 1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.M.; Sun, H.; Liu, C.; Yan, G.L.; Kong, L.; Han, Y.; Wang, X.J. Research Advances in Mechanism of Salvianolic Acid B in Treating Coronary Heart Disease. China J. Chin. Mater. Med. 2025, 50, 1449–1457. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Z.; Xu, Y. Myocardium Protective Function of Salvianolic Acid B in Ischemia Reperfusion Rats. Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med. 2016, 13, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Pu, Z.; Cao, G.; You, D.; Zhou, Y.; Deng, C.; Shi, M.; Nile, S.H.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, W.; et al. Tanshinone and Salvianolic Acid Biosynthesis Are Regulated by SmMYB98 in Salvia miltiorrhiza Hairy Roots. J. Adv. Res. 2020, 23, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, P.; Zhang, L.; Chen, J.F.; Tan, H.X.; Xiao, Y.; Dong, X.; Zhou, X.; Chen, W.S. 13C Tracer Reveals Phenolic Acids Biosynthesis in Hairy Root Cultures of Salvia miltiorrhiza. ACS Chem. Biol. 2013, 8, 1537–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, D.; Zhou, H.; Li, J.; Lu, S. Analysis of the Laccase Gene Family and miR397-/miR408-Mediated Posttranscriptional Regulation in Salvia miltiorrhiza. PeerJ 2019, 7, e7605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Feng, J.; Chen, L.; Xu, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhou, Y.; Tan, H.; et al. Genome-Wide Identification and Characterization of Salvia miltiorrhiza Laccases Reveal Potential Targets for Salvianolic Acid B Biosynthesis. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Geng, L.; Zhang, Y.; Jones, J.A.; Zhang, M.; Chen, Y.; Tan, R.; Koffas, M.A.G.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, S. De Novo Biosynthesis of Salvianolic Acid B in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Engineered with the Rosmarinic Acid Biosynthetic Pathway. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 2290–2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, C.-J. Multifaceted Regulations of Gateway Enzyme Phenylalanine Ammonia-Lyase in the Biosynthesis of Phenylpropanoids. Mol. Plant 2015, 8, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Qin, H.; Zhan, H.; Dong, S.; Li, T.; Cao, X. Comparative Analysis of Three SmHPPR Genes Encoding Hydroxyphenylpyruvate Reductases in Salvia miltiorrhiza. Gene 2024, 892, 147868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.-Q.; Chen, J.-F.; Yi, B.; Tan, H.-X.; Zhang, L.; Chen, W.-S. HPPR Encodes the Hydroxyphenylpyruvate Reductase Required for the Biosynthesis of Hydrophilic Phenolic Acids in Salvia miltiorrhiza. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 2017, 15, 917–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Zhu, B.; Qin, L.; Rahman, K.; Zhang, L.; Han, T. Transcription Factor: A Powerful Tool to Regulate Biosynthesis of Active Ingredients in Salvia miltiorrhiza. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 622011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q.; Han, L.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, C.; Li, Y.; Xue, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, D.; Niu, J.; Hua, W.; et al. SmMYB4 Is a R2R3-MYB Transcriptional Repressor Regulating the Biosynthesis of Phenolic Acids and Tanshinones in Salvia miltiorrhiza. Metabolites 2022, 12, 968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Shi, M.; Deng, C.; Lu, S.; Huang, F.; Wang, Y.; Kai, G. The Methyl Jasmonate-Responsive Transcription Factor SmMYB1 Promotes Phenolic Acid Biosynthesis in Salvia miltiorrhiza. Hortic. Res. 2021, 8, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Li, S.; Dong, S.; Wang, L.; Qin, H.; Zhan, H.; Wang, D.; Cao, X.; Xu, H. SmJAZ4 Interacts with SmMYB111 or SmMYC2 to Inhibit the Synthesis of Phenolic Acids in Salvia miltiorrhiza. Plant Sci. 2023, 327, 111565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Xia, M.; Su, P.; Zhang, Y.; Tu, L.; Zhao, H.; Gao, W.; Huang, L.; Hu, Y. MYB Transcription Factors in Plants: A Comprehensive Review of Their Discovery, Structure, Classification, Functional Diversity and Regulatory Mechanism. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 282, 136652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambawat, S.; Sharma, P.; Yadav, N.R.; Yadav, R.C. MYB Transcription Factor Genes as Regulators for Plant Responses: An Overview. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2013, 19, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millard, P.S.; Kragelund, B.B.; Burow, M. R2R3 MYB Transcription Factors—Functions Outside the DNA-Binding Domain. Trends Plant Sci. 2019, 24, 934–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, D.; Gain, H.; Mandal, A. MYB Transcription Factor: A New Weapon for Biotic Stress Tolerance in Plants. Plant Stress 2023, 10, 100252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.Y.; Zhou, J.Z.; Ying, Y.L.; Tang, K.J.; Han, J.Y.; Wang, Q.Y.; Kai, G.Y. Comprehensive Analysis of the R2R3-MYB Transcription Factor Gene Family in Salvia Miltiorrhiza and the Regulatory Role of SmMYB50 in Salvianolic Acid Metabolism. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 2025, 44, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Liu, H.; Mei, Q.; Yang, J.; Ma, F.; Mao, K. Characteristics of bHLH Transcription Factors and Their Roles in the Abiotic Stress Responses of Horticultural Crops. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 310, 111710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, P.; Jiang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Jiang, M.; Ji, X.; Ma, L.; Jin, G.; Li, J.; Zhang, S.; Kong, D.; et al. Functions of Basic Helix–Loop–Helix (bHLH) Proteins in the Regulation of Plant Responses to Cold, Drought, Salt, and Iron Deficiency: A Comprehensive Review. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 10692–10709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Luo, H.; Xu, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Ji, A.; Song, J.; Chen, S. Genome-Wide Characterisation and Analysis of bHLH Transcription Factors Related to Tanshinone Biosynthesis in Salvia miltiorrhiza. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 11244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Wei, S.; Zheng, X.; Tu, P.; Tao, F. APETALA2/Ethylene-Responsive Factors in Higher Plant and Their Roles in Regulation of Plant Stress Response. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2024, 44, 1533–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.-L.; Li, A.-M.; Wang, M.; Qin, C.-X.; Pan, Y.-Q.; Liao, F.; Chen, Z.-L.; Zhang, B.-Q.; Cai, W.-G.; Huang, D.-L. The Role of AP2/ERF Transcription Factors in Plant Responses to Biotic Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, K.; Hou, X.-L.; Xing, G.-M.; Liu, J.-X.; Duan, A.-Q.; Xu, Z.-S.; Li, M.-Y.; Zhuang, J.; Xiong, A.-S. Advances in AP2/ERF Super-Family Transcription Factors in Plant. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2020, 40, 750–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, A.J.; Luo, H.M.; Xu, Z.C.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, Y.J.; Liao, B.S.; Yao, H.; Song, J.Y.; Chen, S.L. Genome-Wide Identification of the AP2/ERF Gene Family Involved in Active Constituent Biosynthesis in Salvia miltiorrhiza. Plant Genome 2016, 9, plantgenome2015.08.0077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, T.; Wang, H.; Zhao, W.; Guo, Z. Transcription Factor WRKY Complexes in Plant Signaling Pathways. Phytopathol. Res. 2025, 7, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahiwal, S.; Pahuja, S.; Pandey, G.K. Review: Structural-Functional Relationship of WRKY Transcription Factors: Unfolding the Role of WRKY in Plants. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 257, 128769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Guo, W.; Yang, D.; Hou, Z.; Liang, Z. Transcriptional Profiles of SmWRKY Family Genes and Their Putative Roles in the Biosynthesis of Tanshinone and Phenolic Acids in Salvia miltiorrhiza. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, C.; Ribeiro, B.; Amaro, R.; Expósito, J.; Grimplet, J.; Fortes, A.M. Network of GRAS Transcription Factors in Plant Development, Fruit Ripening and Stress Responses. Hortic. Res. 2023, 10, uhad220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waseem, M.; Nkurikiyimfura, O.; Niyitanga, S.; Jakada, B.H.; Shaheen, I.; Aslam, M.M. GRAS Transcription Factors Emerging Regulator in Plants Growth, Development, and Multiple Stresses. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2022, 49, 9673–9685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Liu, C.; Liu, J.; Bai, Z.; Liang, Z. Transcriptomic Analysis Reveals the GRAS Family Genes Respond to Gibberellin in Salvia miltiorrhiza Hairy Roots. BMC Genom. 2020, 21, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Dzinyela, R.; Yang, L.; Hwarari, D. bZIP Transcription Factors: Structure, Modification, Abiotic Stress Responses and Application in Plant Improvement. Plants 2024, 13, 2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Wang, C.; Yang, X.; Wang, L.; Ye, J.; Xu, F.; Liao, Y.; Zhang, W. Role of bZIP Transcription Factors in the Regulation of Plant Secondary Metabolism. Planta 2023, 258, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, Z.; Ji, A.; Luo, H.; Song, J. Genomic Survey of bZIP Transcription Factor Genes Related to Tanshinone Biosynthesis in Salvia miltiorrhiza. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2018, 8, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, H.; He, H.; Chang, Y.; Miao, B.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Q.; Dong, F.; Xiong, L. Multiple Roles of NAC Transcription Factors in Plant Development and Stress Responses. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2025, 67, 510–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xu, J.; Chen, H.; Jin, W.; Liang, Z. Characterization of NAC Family Genes in Salvia miltiorrhiza and NAC2 Potentially Involved in the Biosynthesis of Tanshinones. Phytochemistry 2021, 191, 112932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]