Abstract

Crop–weed competition markedly reduces cereal yield. Integrative weed management approaches, involving the use of humic acid (HA) and seaweed extract (SWE), have gained attention as herbicide efficacy declines and environmental concerns grow. However, potential synergistic effects between HA and SWE have not yet been investigated. We evaluated the effects of HA, SWE, and their combination (HA+SWE) on the growth, yield, and competitive ability of cereals against wild weed beets (Beta vulgaris L.). A single-season field experiment was conducted using a split-plot design within a randomised complete block to assess the effects of treatment amendments on wheat, barley, and oats. The results showed that HA and HA+SWE organic amendments consistently improved grain yield and biomass across crop species. SWE responses varied across species, indicating species-dependent sensitivity. In addition, HA enhanced barley weed suppression, highlighting its dual roles in improving crop vigour and reducing weed proliferation. In contrast, SWE modestly increased spike length in oats, emphasising its effect on crop growth characteristics. Overall, these preliminary findings support targeted biostimulant use to enhance cereal yield and integrate weed management into sustainable cropping systems.

1. Introduction

Cereals such as wheat (Triticum aestivum L.), barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) and oat (Avena sativa L.) are of major economic and nutritional value [1,2]. As staple food crops, they provide > 50% of human caloric intake and serve as animal feed and industrial raw materials. However, their productivity is strongly limited by crop–weed competition [3,4].

Wild weed beets (Beta sp.) are derived from self-domestication, hybridisation with sea beets [Beta vulgaris subsp. maritima (L.) Arcang.], or the cultivation of sugar beets (Beta vulgaris L.) [5,6]. Recently, they have been extensively distributed across European sugar beet fields due to hybridisation between cultivated sugar beets and their wild relatives. Gene flow has resulted in feral hybrids with enhanced competitiveness, making wild weed beets more problematic and difficult to control in cereal–beet rotations [7,8,9].

Weed infestation remains a major challenge in cropping systems, especially cereals, where weeds compete for light, nutrients, water, and space, often causing substantial yield losses. Estimated cereal yield reductions due to weed interference range from approximately 26% to 40%, and may be higher under severe pressure [10,11,12]. Moreover, several dominant weed species associated with sugar beet production have evolved resistance to commonly used herbicides, thereby reducing the effectiveness of chemical control [13,14]. Concerns also persist regarding the long-term impacts of herbicide application on sustainability and food safety, as the overuse of herbicides contributes to herbicide resistance [15], soil biodiversity loss, water contamination, and increased production costs when the environmental externalities are considered [16,17]. Similar trends have been recorded in other cropping systems, where herbicides exert only a minor impact on weed community structure compared with environmental and cultural factors, highlighting the limitations of management strategies based on herbicides [18]. Therefore, there is increasing interest in non-chemical and eco-friendly weed management strategies [19,20], such as using organic amendments [e.g., humic acid (HA) and seaweed extract (SWE)] to improve crop competitiveness and, thus, address the environmental and economic problems caused by weed infestation [19,20].

HA is a naturally occurring polymer and heterocyclic compound with biostimulant and soil-conditioning properties [21,22]. It plays an essential role in enhancing plant growth and stress tolerance, as evidenced by its ability to increase plant dry biomass and improve crop resistance to environmental stressors [23,24,25]. Moreover, HA application in cereals such as maize has been shown to increase grain yield by enhancing the uptake of essential nutrients, including nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium [26,27,28,29], thereby improving crop growth [30,31]. Furthermore, a recent meta-analysis reported that HA application can increase crop production by approximately 12% and nitrogen use efficiency by 27% across various agroecological zones, highlighting its important role in sustainable agriculture [32]. Although HA is widely used in intensive technologies to enhance the physiological potential of crops [33,34,35,36], it elicits a restrictive effect on crop genotypes [36,37] because it is not a universal agent that promotes the occurrence of novel, non-inherent plant growth characteristics [36]. By modulating hormone-like activity, photosynthesis and respiration, the carboxyl and phenolic groups in HA enhance nutrient availability, water retention, microbial activity and stress tolerance at the molecular and edaphic levels [34,35,38].

Aside from promoting crop growth, previous studies have reported that HA is instrumental in enhancing soil physical and biochemical properties. It improves soil structure, texture, water-holding capacity and microbial activity, increases macro- and micronutrient availability [34,38,39,40,41], and reduces the mobility of toxic heavy metals in the soil [38,42]. However, the effects of HA stimulants on crop performance and soil conditions remain inconsistent [38,43,44,45,46] largely due to conflicting research findings across varying HA doses and soil characteristics. For instance, Rose et al. [24] reported that HA application influenced soil chemical characteristics; however, its effects on crop growth traits remain uncertain. Meanwhile, Gollenbeek and Van Der Weide [47] found that HA application improved soil physical properties.

Furthermore, HA may indirectly suppress weed proliferation by increasing crop vigour and canopy closure, reducing competitive ecological niches and inducing allopathic shifts in soil microbial communities in favour of crops [31,36]. Canopy formation and other competitive characteristics of crops play an important role in reducing weed biomass by quickly closing the canopy, thereby restricting the access of weeds to light [19]. Moreover, field experiments revealed that humic preparations, especially when combined with herbicides or nitrogen-based fertilisers, may improve crop yield and enhance weed control efficacy, as in the case of wheat [36].

As with HA, previous studies have shown that the method and frequency of SWE application can significantly influence crop growth responses [48,49,50]. Seaweeds are macroalgae that are integral components of marine and coastal ecosystems; they contribute to marine biodiversity and the biosphere [51]. Seaweeds are rich in phytohormones (e.g., auxins, cytokinins and gibberellins), polysaccharides, amino acids, and minerals that regulate germination, root growth, chlorophyll biosynthesis and photosynthesis. Consequently, SWE enhances plant tolerance to both abiotic (e.g., drought, salinity and temperature) and biotic (e.g., fungal, bacterial and viral pathogens) stressors [48,51,52]. SWE has been documented to improve crop performance in terms of germination, seed vigour, biomass, and yield quality in several crop species, including tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.), sweet pepper (Capsicum annuum L.), lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.), cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.), strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa (Duchesne ex Weston) Duchesne ex Rozier), grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) and kiwifruit (Actinidia deliciosa L.) [51,52,53,54]. However, SWE responses are species- and context-specific, and benefits are often more pronounced when combined with nitrogen fertilisers [55,56,57].

Although HA and SWE are being considered in sustainable farming, their combined effects on cereal competitiveness against wild weed beets, especially under the semi-arid conditions of southern Iraq, have not yet been investigated. Integrating HA and SWE could offer complementary advantages as HA mainly improves soil productivity and root growth, while SWE accelerates shoot enlargement and accentuates reproductive characteristics. For instance, it has been recently reported that the foliar application of a combination of HA and SWE on fruit crops grown in arid environments can greatly improve their nutrient uptake, yield and quality [58,59]. Meanwhile, the preliminary results of the combined application of HA and SWE to barley suggest synergistic effects; however, comprehensive multi-environment trials validating these findings are still lacking [60].

Hence, this study was conducted to evaluate the synergistic effects of HA and SWE on the growth, yield, and weed-suppression ability of three cereal crops grown in competition with wild weed beets. Specifically, the objectives were to determine (i) species-specific reactions of wheat, barley and oats to HA, SWE and HA+SWE organic amendment; (ii) weed suppression dynamics based on the responses of aggressive wild weed beets to biostimulants; (iii) synergistic interactions between HA and SWE; and (iv) biostimulant effects under semi-arid conditions. The overall aim was to evaluate the combined effects of humic acid and seaweed extract on cereal crop performance and weed suppression to support the development of species-specific amendment strategies to enhance crop competitiveness, yield, and quality.

2. Results

2.1. Effects of Organic Amendments on Spike Length

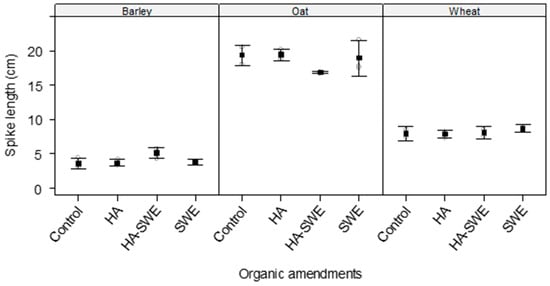

The two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed that the effects of organic amendments on the spike length of the cereal crops were not significant (F3,18 = 1.78, p = 0.197; Table 1), indicating consistent results across replicates (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Significance levels from analysis of variance for crop parameters and wild beet biomass.

Figure 1.

Effect of humic acid (HA), seaweed extract (SWE), and a mixture of HA and SWE (HA+SWE) on the spike length of cereal crops. The black squares represent the mean spike length (cm) of the crops under each organic amendment. The vertical bars represent a 95% confidence interval. The hollow circles represent the replicates. Data were collected at the conclusion of the 2021–2022 winter growing season experiment. Each mean value represents n = 3 replicates per treatment × crop species.

In contrast, highly significant differences were observed among the crop species (F2,18 = 615.70, p < 0.000001; Table 1). Across all treatments, oats had the longest spikes (18.65 cm), whereas barley had the shortest (4.11 cm; Figure 1).

The results also showed a significant interaction between crop species and treatments (F6,18 = 2.76, p = 0.0443; Table 1), suggesting that the response of spike length to organic amendments varied by cereal species. For instance, the spikes of oats were longest under the HA organic amendment (19.47 cm), followed by the SWE (19.0 cm) and HA+SWE organic amendment (16.85 cm). However, barley had the tallest spikes under the combined amendment (5.12 cm) compared with that of the others organic amendments, but it had overall the shortest spikes across organic amendments in comparison with the other crop species (Figure 1).

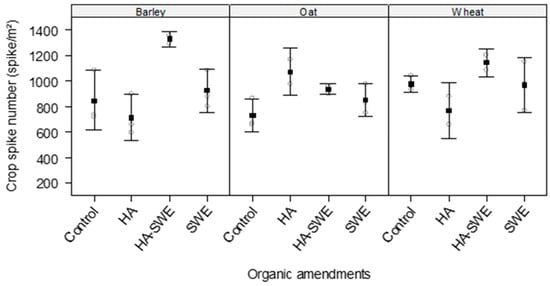

2.2. Effects of Organic Amendments on Spike Number

The results of ANOVA revealed that the organic amendments had highly significant effects on the spike number of the cereal crops (F3,18 = 5.32, p = 0.00838; Table 1). The HA+SWE organic amendment produced the highest spike number (1109 spikes m−2), followed by the SWE organic amendment (914 spikes m−2). In contrast, spike number did not significantly differ among the crop species (F2,18 = 0.85, p = 0.44; Table 1).

Nonetheless, a significant interaction between crop species and treatments (F6,18 = 3.41, p = 0.020) was observed (Table 1), indicating that the response of spike number to organic amendments varied by cereal species (Figure 2). The spike number of barley (1328 spike m−2) and wheat (1144 spikes m−2) was highest under the HA+SWE organic amendment, whereas that of oats was highest under the HA organic amendment (1072 spikes m−2).

Figure 2.

Effect of humic acid (HA), seaweed extract (SWE), and a mixture of HA and SWE (HA+SWE) on the spike number of cereal crops. The black squares represent the mean spike number (spikes m−2) of cereal crops under each treatment. The vertical bars represent a 95% confidence interval. The hollow circles represent the replicates. Data were collected at the conclusion of the 2021–2022 winter growing season experiment. Each mean value represents n = 3 replicates per treatment × crop species.

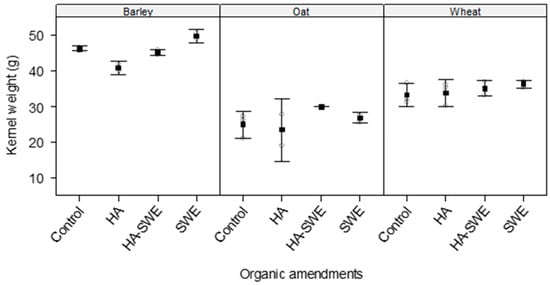

2.3. Effects of Organic Amendments on Kernel Weight

The results of ANOVA revealed highly significant differences (F3,18 = 6.09, p = 0.00479) among the organic amendments in terms of kernel weight (Table 1). Kernel weight was highest under the HA+SWE organic amendment (37.5 g), whereas the lowest occurred under the HA organic amendment (32.8 g; Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Effect of humic acid (HA), seaweed extract (SWE), and a mixture of HA and SWE (HA+SWE) on the kernel weight of cereal crops. The black squares represent the mean kernel weight (g) of cereal crops under each treatment. The vertical bars represent a 95% confidence interval. The hollow circles represent the replicates. Data were collected at the conclusion of the 2021–2022 winter growing season experiment. Each mean value represents n = 3 replicates per treatment × crop species.

Similarly, crop species had a strong influence on kernel weight (F2,18 = 187.98, p < 0.000001; Table 1), with barley producing the greatest kernel weight across the treatments (Figure 3).

Additionally, the interaction between crop species and the organic amendment treatments was significant (F6,18 = 2.67, p = 0.04945), demonstrating that the response of kernel weight to the biostimulants varied by crop species (Table 1). Under the SWE and HA+SWE organic amendment, barley displayed the greatest kernel weight (49.4 and 45.0 g, respectively), followed by wheat (36.2 and 35.0 g, respectively; Figure 3). Although the SWE organic amendment increased the kernel mass of barley by 7%, it had a limited effect on wheat.

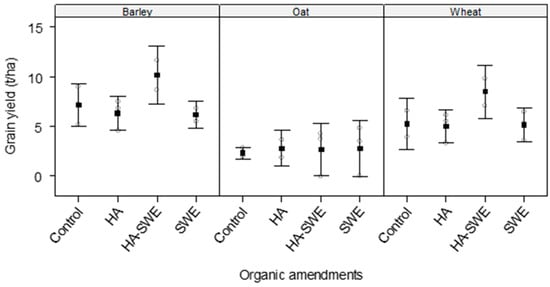

2.4. Effects of Organic Amendments on Grain Yield

The results of ANOVA revealed highly significant differences (F3,18 = 6.88, p = 0.00389) among the organic amendments in terms of grain yield (Table 1). Grain yield was highest under the HA+SWE organic amendment (6.49 t ha−1), showing an approximately 32.7% increase compared with that of the control; in contrast, it was lowest under the SWE organic amendment, regardless of crop species (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Effect of humic acid (HA), seaweed extract (SWE), and a mixture of HA and SWE (HA+SWE) on the grain yield of cereal crops. The black squares represent the mean grain yield (t ha−1) of cereal crops under each treatment. The vertical bars represent a 95% confidence interval. The hollow circles represent the replicates. Data were collected at the conclusion of the 2021–2022 winter growing season experiment. Each mean value represents n = 3 replicates per treatment × crop species.

The results of ANOVA also revealed that the crop species elicited an extremely strong effect on grain yield (F2,18 = 24.67, p < 0.0001). Among the crop species, barley produced the greatest grain yield (7.3 t·ha−1), whereas oats produced the lowest grain yield (2.65 t ha−1; Figure 4).

However, the interaction between crop species and organic amendments was not significant (F6,18 = 0.57, p = 0.74784), suggesting that yield improvements conferred by the amendments were broadly similar across the cereal crops (Figure 4). Compared with the control, the HA and SWE organic amendments increased the grain yield of oats by approximately 14–19%, whereas the HA+SWE organic amendment increased the grain yield of barley and wheat by 42% and 60%, respectively.

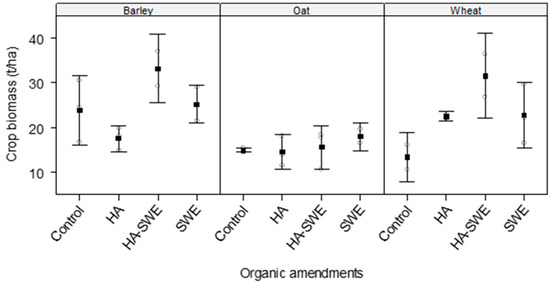

2.5. Effects of Organic Amendments on Aboveground Crop Biomass

The results showed that the organic amendments significantly influenced aboveground crop biomass (F3,18 = 4.56, p = 0.016) compared with that of the control (Table 1). Biomass was greatest under the HA+SWE organic amendment (25.20 t ha−1; Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Effect of humic acid (HA), seaweed extract (SWE), and a mixture of HA and SWE (HA+SWE) on the aboveground biomass of cereal crops. The black squares represent the mean biomass (t ha−1) of cereal crops under each treatment. The vertical bars represent a 95% confidence interval. The hollow circles represent the replicates. Data were collected at the conclusion of the 2021–2022 winter growing season experiment. Each mean value represents n = 3 replicates per treatment × crop species.

Similarly, crop species exerted a highly significant effect on aboveground crop biomass (F2,18 = 10.02, p = 0.00133), reflecting substantial differences in biomass accumulation among the three cereal crops (Table 1). Barley (24.25 t ha−1) produced the greatest biomass, followed by wheat (22.61 t ha−1) and oats (15.57 t ha−1; Figure 5).

The interaction between crop species and treatment was not significant (F6,18 = 2.38, p = 0.07512), suggesting species-specific responses to amendment type (Figure 5). Under the HA organic amendment, wheat produced the greatest biomass, followed by barley and oats. Meanwhile, under the SWE and HA+SWE organic amendment, barley produced the greatest biomass, whereas oats produced the lowest biomass (Figure 5).

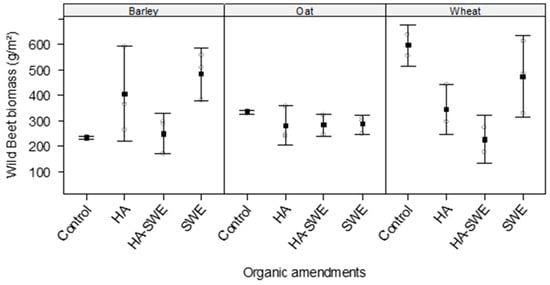

2.6. Effects of Organic Amendments on the Biomass of Wild Weed Beets

The results of ANOVA revealed that the organic amendments (F3,18 = 5.63, p = 0.0067) significantly affected the dry weight of wild weed beets (Table 1). Specifically, it decreased to 256 g m−2 under the HA+SWE organic amendment compared with that of the other organic amendment treatments (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Effect of humic acid (HA), seaweed extract (SWE), and a mixture of HA and SWE (HA+SWE) on the biomass of wild weed beets (g m−2). The black squares represent the mean dry weight of wild weed beets in competition with cereal crops under each treatment. The vertical bars represent a 95% confidence interval. The hollow circles represent the replicates. Data were collected at the conclusion of the 2021–2022 winter growing season experiment. Each mean value represents n = 3 replicates per treatment × crop species.

The results also showed that the crop species significantly differed in their effects on the dry weight of wild weed beets (F2,18 = 5.50, p = 0.01365). The highest dry weight of wild weed beets was recorded in the wheat plots (410.42 g m−2), whereas the lowest was recorded in the oat plots (291.84 g m−2).

Similarly, the interaction between cereal crop species and organic amendments was highly significant (F6,18 = 5.19, p = 0.00294; Table 1). Under the HA+SWE organic amendment, the lowest dry weight of wild weed beets was recorded in the wheat plots (226 g m−2), followed by the oat plots (282.45 g m−2). Meanwhile, under the HA organic amendment, the lowest dry weight of wild weed beets (280.27 g m−2) was recorded in the oat plots (Figure 6).

3. Discussion

This study demonstrates that HA and SWE applications can modulate both crop growth performance and weed suppression, eliciting species-specific responses. The HA-SWE treatments consistently produced the largest spike number (Figure 2), greatest kernel weight (Figure 3), grain yield (Figure 4), biomass (Figure 5) and lowest wild beet biomass (Figure 6). These findings align with Nasiroleslami et al. [22], who found that wheat yield was significantly increased following combined HA and SWE application, particularly under increased nitrogen fertiliser at higher rates. They attributed these improvements to physiological and nutritional processes such as the creation of a nutrient sink, new tissue formation, and enhanced photosynthesis [61]. It was also reported that the combination of HA and SWE may improve soil characteristics and promote rhizosphere for nutrient uptake. A similar finding was reported in maize, where organic amendments improved growth and grain yield, potentially through nitrogen use efficiency, micronutrient and macronutrient recovery, phosphorus solubilization and uptake by the plants and enhanced potassium availability for crop plants [62].

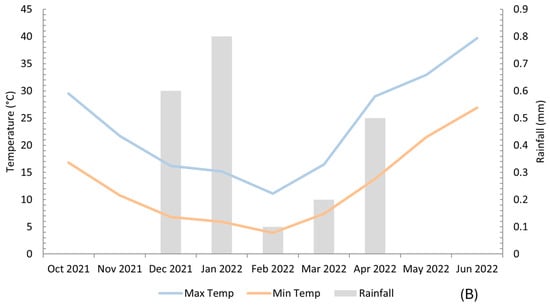

Although the study area was irrigated, the weather conditions during the 2021–2022 season likely shaped treatment responses. Extremely low rainfall (2.2 mm) and moderate winter temperatures implied that crop growth depended largely on irrigation. Under these conditions, biostimulants enhancing nutrient uptake and physiological efficiency, particularly HA and HA+SW, would be expected to confer additional benefits, consistent with the increased biomass and yield observed. The variable response to SWE alone may reflect the greater sensitivity of its hormone-mediated effects to environmental fluctuations, even under irrigation.

The increased kernel weight observed in HA-treated barley samples supports the findings of As et al. [60], who reported that growth regulators, such as HA, positively influence source–sink dynamics, particularly during grain filling.

Consistent with our results that the HA organic amendment significantly improved cereal biomass (Figure 6) and grain yield (Figure 5) under semi-arid conditions, a recently published global meta-analysis synthesising 120 field studies and encompassing 479 paired observations [32] revealed that HA increases yield, nitrogen use efficiency and nitrogen uptake in upland cereals and cash crops cultivated in neutral-to-alkaline soils (pH ≥ 6) and regions receiving > 300 mm of annual precipitation remarkably. It further elucidates that HA enhances soil fertility through cation-exchange complexation, stimulation of microbial activity, and formation of organo-mineral associations that improve nitrogen retention and uptake efficiency.

Moreover, the ability of HA to stimulate root growth, improve photosynthetic activity, and accelerate nutrient uptake by modulating phytohormone balance and enzymatic activities [38,39] collectively enhances soil fertility and plant vigour, which likely contributed to the improved cereal performance observed in this study. At the soil surface, HA improves soil structure by improving its cation exchange, water-holding capacities, and reducing the mobility of toxic heavy metals [27,31,42]. These functions are particularly beneficial in the semi-arid conditions of southern Iraq, where soil organic matter content is low and rainfall is restricted. Such mechanisms likely explain the uniform increase in biomass observed in the HA-treated plots. In addition, the stronger response of barley than that of wheat confirms genotype-specific variation in sensitivity to HA [36]. Overall, the uniform response across the cereal crops indicates that these organic amendments can enhance cereal yield.

The HA organic amendment significantly induced weed suppression, as indicated by the reduced biomass of wild weed beets in the barley plots. The influence of HA on crop yield components and wild weed beet biomass can be attributed to its role in improving nutrient uptake and stress resistance by modulating hormonal and redox metabolisms [38,63]. These processes enhanced soil function and barley’s competitive ability, thereby reducing weed growth [61,64].

However, the interaction between crop species and organic amendments indicates that the suppressive effect of the HA organic amendment on wild weed beets varied across cereal species, highlighting crop-specific enhancement of competitive ability. Weed biomass was more greatly reduced in the HA-treated barley plots than in the HA-treated oat and wheat plots (Figure 6), suggesting that oats and wheat require different stimulant treatments to achieve weed suppression levels similar to those observed in barley. The more pronounced effect of HA on the enhanced competitiveness of barley against wild weed beets may be attributed to the rapid early growth and denser canopy of barley, which, together with HA-enhanced vigour, improved its ability to acquire resources and reduce the ecological niche available for wild weed beets [19,20]. This interpretation is further supported by the higher above-ground biomass accumulation observed in barley (Figure 5), although it should be viewed within the limits of the presented data. Further quantification of early growth dynamics and canopy structure is recommended to confirm the underlying mechanism. Similar outcomes were noted by Stybayev et al. [65], who observed that the introduction of cover crops in north-eastern Kazakhstan during spring was an effective way to suppress weeds and enhance forage-crop productivity in the arid steppe soils, highlighting that non-chemical interventions can sustainably improve crop competitiveness by lowering weed pressure while maintaining productivity.

The SWE induced a modest increase in oat spike length and varied effects on spike number in wheat and barley [55,57], consistent with previous findings that SWE may increase kernel weight and crop yield under various nitrogen fertiliser levels [56]. However, inconsistencies in the influence of SWE on crop yield suggest that different cereal species require different optimal doses and application times. Such variation likely reflects the complex bioactive composition (e.g., cytokinins, auxins, betaines, and gibberellin-like compounds), which functions in various ways based on species and developmental stage [39,51].

Recent studies also indicate that the benefits of SWE are amplified when supplemented with nutrient amendments, such as nitrogen [55,56,57]. This is supported by the agronomic practice of synchronising SWE application with crop nutritional status to achieve optimal results.

The combination of HA and SWE reflected the effects of HA alone; however, slight additional improvements in biomass were observed, suggesting potential synergistic interactions. Mechanistically, this can be attributed to the complementary functions of HA (e.g., root and soil enhancement) and SWE (e.g., shoot elongation and reproductive stimulation); hence, a combination of HA and SWE may support both vegetative and reproductive growth [60].

For instance, Al-Saif et al. [59] reported that the foliar application of a combination of HA (2000 mg L−1) and SWE (3000 mg L−1) on apricot (Prunus armeniaca L.) plants grown under arid conditions significantly increased their fruit set, yield, and nutrient content (nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, calcium, magnesium, iron, zinc, and manganese). Although apricot is a perennial fruit crop, the same mechanism—increasing nutrient uptake and stimulating metabolism—is involved behind the yield-enhancing effects of combined HA and SWE applications on apricots and cereals. Such cross-crop evidence indicates that HA+SWE enhances crop nutrient use efficiency in water- and nutrient-limited environments.

Similarly, Abdel-Sattar et al. [58] observed that combined HA and SWE applications improved the nutrient assimilation, chlorophyll synthesis, carbohydrate accumulation, and fruit yield of mangoes (Mangifera indica L.) under arid conditions. Although their [58] work focused on fruit physiology, they confirm that HA and SWE act synergistically to enhance crops’ photosynthetic efficiency and metabolic performance—processes fundamental to spike and grain development in cereals. The parallel mechanisms underlying the enhancement of fruit physiology and improvement of cereal yield substantiate the complementary functions of HA and SWE.

Beyond increasing crop yield, the combination of SWE and HA may reinforce crop vitality via indirect competitive strategies. SWE derived from Ascophyllum nodosum enhances leaf area, chlorophyll content, and antioxidant activity of cereals [48,52,54,55,56], resulting in rapid crop establishment and enhanced physiological performance. These traits enhance crop competitiveness by improving resource capture; however, none of the cited studies directly assessed the effects of HA and SWE on weed suppression, rhizosphere microbial community composition, or allelopathic interactions between crops and weeds.

Evidence for weed suppression via combined HA and SWE applications in cereals remains limited. Nevertheless, HA+SWE organic amendment has been shown to enhance foliar nutrient content, chlorophyll concentration, and yield in fruit crops [58,59], supporting the possibility of enhancing crop vigour and competitiveness under semi-arid conditions.

As the field experiment was conducted under the semi-arid conditions of southern Iraq, characterised by low precipitation and limited soil organic matter, the results of this study suggest biostimulants as sustainable substitutes for chemical herbicides and fertilisers. Meanwhile, despite being targeted, SWE’s dose- and time-manipulative response underscores the imperative of site-specific calibration of dose, time and crop selection. Such biostimulant application procedures fit within integrated weed management [15,66], enabling stable cereal yield in semi-arid environments.

The interpretability of the present findings is framed by the experimental context. Since the trial was conducted at a single semi-arid site and at fixed HA and SWE rates, the observed responses reflect performance under a single set of climatic and edaphic conditions rather than the full range of environments whereby cereals are cultivated. Similarly, wheat, barley, and oats responded to a single dominant weed competitor, indicating that crop weed dynamics may differ in alternative community compositions. These constraints do not undermine the trends identified here but clarify that the mechanisms proposed, particularly the differential enhancement of crop vigour and weed suppression, should be considered under contrasting environmental conditions and management intensities to assess their stability.

4. Materials and Methods

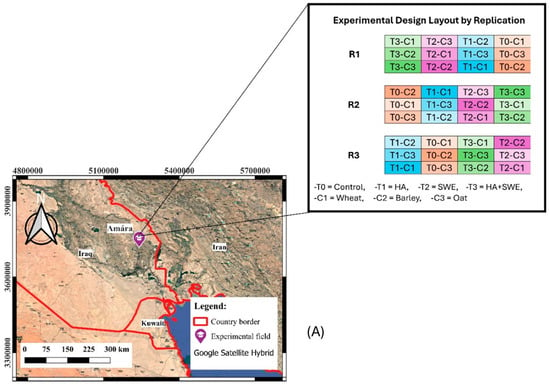

4.1. Site Description

A field experiment was conducted during the 2021–2022 winter season at the Forest Nursery Farm in Amarah City, southeast Iraq (31.88898 °N latitude and 47.08025 °E longitude). The study site was 12 m above the mean sea level. Prior to planting, composite soil samples were collected from multiple locations across the experimental field to analyse key soil physical and chemical properties using the standard procedures outlined by Black [67] and Page et al. [68].

Amarah City has a hot desert climate, characterised by extremely hot, dry summers and cool, wet winters. The temperature ranges between −1 °C and 26 °C from December to February and 33–40 °C from March to May, reflecting its characteristic dryness and significant thermal fluctuation throughout the year. The climatic characteristics of the study site are presented in Figure 7. The mean temperature during the growing season was approximately 18.1 °C, and the total rainfall was approximately 2.2 mm. Figure 7B shows the monthly average temperature and precipitation during the study period. The average temperature decreased from October to February, then increased from March to June. In contrast, the average precipitation exhibited a fluctuating pattern: it steeply increased from October to January and from March to April, then drastically declined from January to February and from April to June [69,70].

Figure 7.

Overview of the experimental field and data collection procedure. (A) Geographical map of the study area and field layout showing different combinations of treatments and cereal crop species. To represent the same treatment, blocks R1, R2 and R3 are of the same colour. (B) Monthly maximum and minimum air temperatures and rainfall at the experimental site in Amarah, Iraq, during the 2021–2022. Temperature values represent monthly means, while rainfall values represent total monthly precipitation.

Based on texture, the soil in the experimental field was classified as silty clay loam. Soil pH was 7.82, determined according to the method described by Page (1982) [68], organic matter content was low (0.98%) and nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium concentrations were 28.50, 16.25 and 21.00 g·kg−1, respectively, expressed on dry soil basis (Table 1). Other soil physical and chemical properties are listed in Table 1.

4.2. Experimental Design

The experiment was conducted during the 2021–2022 winter season by applying a randomised completely blocked design (RCBD) using a split-plot arrangement with three replicates. A summary of the crop characteristics, plot layout, and experimental design is provided in Table 2. Each block was divided into four whole plots; then, each whole plot was further subdivided into three subplots. Each subplot had an area of 4 m2, consisting of eight crop lines with 25 cm row spacing. The whole plots were randomly assigned to four experimental setups corresponding to biostimulant (organic amendment) application: control (no organic amendment), HA (5 mL·L−1), SWE (Ascophyllum nodosum, 3 mL·L−1) and a combination of HA and SWE (HA+SWE). Meanwhile, three cereal crops that are adaptable to the semi-arid environments in southern Iraq, a Spanish wheat variety (Triticum aestivum cv. Ibaa 99), barley (Hordeum vulgare cv. Bohoth 244) and an oat variety that has adapted to the study site (Avena sativa cv. Shifa) were randomly planted across the subplots on 10 December 2021 (Figure 7A).

Table 2.

Summary of continuous and categorical variables used in the field experiment.

The plants emerged at 10–14 weeks after sowing and were irrigated and fertilised regularly during the growing season. The organic amendments were applied approximately 60 days after sowing (i.e., upon reaching the tillering stage). HA and SWE were applied in the early morning under cool conditions (approximately 15–18 °C) and minimal wind, ensuring proper spray deposition, reduced evaporation, and uniform absorption. Standard agronomic practices, including tillage, irrigation, fertilisation, and pest control, were applied uniformly across all plots to ensure consistent growth conditions (Table 2). The most prevalent weed species in the field was wild weed beets. Other weed species emerged sporadically and were cleared by hand during the initial crop cultivation to ensure that wild weed beets served as the primary competitor of the cereal crops.

4.3. Measurements

The spike length, spike number, kernel weight, grain yield and crop biomass of the cereal crops as well as wild beet biomass were recorded at the harvest stage (about 150 days after sowing). The sample size was 0.0625 m2 per subplot (Table 2). The spike number and wild beet biomass were calculated and converted to number and gram per square meter, respectively, while grain yield and total biomass were converted to tons per hectare (t·ha−1). The samples were dried at 75 °C for 72 h and then reweighed to determine the dry biomass to the nearest milligram [71].

4.4. Statistical Analysis

The collected data were statistically analysed using R i386 software v.3.5.3 [72]. Two-way ANOVA was 566 performed to examine the effects of crop species (barley, oats and wheat) and soil amendment treatments (control, HA, SWE and HA+SWE) on aboveground crop biomass. The significant differences among soil amendment treatments were separated at the 0.95% confidence interval [72,73]. A basic linear model was performed with the two-way ANOVA to examine the effects of crop species (barley, oats and wheat) and soil organic amendment treatments (control, HA, SWE and HA+SWE) on aboveground crop biomass. The source of variances and statistical values of all parameters are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Two-way ANOVA results for the effects of crop species, organic amendments, and their interaction on cereal growth parameters. SOV, DF, SS, MS, F-values, and p-values are shown.

5. Conclusions

In this study, the synergistic effects of HA and SWE, which are known biostimulants, on cereal crop competitiveness with wild beets were determined. HA and HA+SWE consistently improved crop biomass and yield components, whereas the effects of SWE alone varied and appeared species dependent. The interaction between cereal crop species and biostimulant treatments highlights the need for crop-specific weed management strategies. These findings provide a solid foundation for recommending tailored amendment regimes to enhance crop competitiveness, suppress weeds and improve the yield and quality of cereal cropping systems. Nonetheless, multi-site and multi-season experiments should be conducted in the future to evaluate the consistency of HA and SWE effects under diverse conditions. Field experiments involving a wider range of doses, varying application schedules, and combinations with different fertilisers will enable management optimisation. Future research combining physiological and molecular studies is required to identify the underlying mechanisms underlying the responses of the crop species included in this study. As our findings revealed, wheat, barley, and oats did not respond equally to HA and SWE organic amendments; thus, it can be postulated that the differences are attributable to variation in hormonal regulation, nutrient transport, or the expression of stress-related genes. The study of these molecular pathways will aid in understanding the mechanisms whereby biostimulants such as HA and SWE regulate crop performance and weed suppression.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.K.A.-M., A.A.H. and H.S.M.K.; data curation, Z.K.A.-M. and A.A.H.; formal analysis, H.S.M.K.; investigation, Z.K.A.-M., I.M.K., H.S.M.K., R.R.S. and A.A.H.; methodology, Z.K.A.-M. and A.A.H.; resources, Z.K.A.-M., H.S.M.K. and A.A.H.; software, Z.K.A.-M., H.S.M.K. and R.R.S., supervision, I.M.K. and V.V.; validation, Z.K.A.-M., I.M.K. and A.A.H.; visualization, Z.K.A.-M. and A.A.H.; writing—original draft, Z.K.A.-M. and H.S.M.K.; writing—review and editing, Z.K.A.-M., H.S.M.K., V.V. and I.M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was funded and supported by the TechCoach (Project ID: 101182908; NRDI ID: 2020-2.1.1-ED-2024-00342) and CSR (Project ID: 101216573; NRDI ID: 2025-3.1.2-KÖA-2025-00020) Horizon Europe projects.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HA | Humic acid |

| SWE | Seaweed extract |

| (HA+SWE) | mixture of HA and SWE |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

References

- Ghasemi-Mobtaker, H.; Kaab, A.; Rafiee, S. Application of life cycle analysis to assess environmental sustainability of wheat cultivation in the west of Iran. Energy 2020, 193, 116768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loskutov, I.G.; Khlestkina, E.K. Wheat, barley, and oat breeding for health benefit components in grain. Plants 2021, 10, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraldeli, A.L.; Silva, G.F.D.; Hijano, N.; Stoinsk, G.; Zucareli, C.; Silva, A.F.M. Weed control periods for two seeding densities in wheat. Int. J. Pest Manag. 2025, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutilloy, E.; Oni, F.E.; Esmaeel, Q.; Clément, C.; Barka, E.A. Plant beneficial bacteria as bioprotectants against wheat and barley diseases. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, C.; Liepelt, S.; Dieckvoss, M.; Bartsch, D.; Ziegenhagen, B.; Ulrich, A. Fast and simple monitoring of introgressive gene flow from wild beet into sugarbeet. J. Sugar Beet Res. 2006, 43, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos, S.; Baião, D.; da Silva, D.V.; Paschoalin, V.M. Beetroot, a remarkable vegetable: Its nitrate and phytochemical contents can be adjusted in novel formulations to benefit health and support cardiovascular disease therapies. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnaud, J.F.; Viard, F.; Delescluse, M.; Cuguen, J. Evidence for gene flow via seed dispersal from crop to wild relatives in Beta vulgaris (Chenopodiaceae): Consequences for the release of genetically modified crop species with weedy lineages. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2003, 270, 1565–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viard, F.; Arnaud, J.F.; Delescluse, M.; Cuguen, J. Tracing back seed and pollen flow within the crop–wild Beta vulgaris complex: Genetic distinctiveness vs. hot spots of hybridization over a regional scale. Mol. Ecol. 2004, 13, 1357–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnaud, J.F.; Fénart, S.; Cordellier, M.; Cuguen, J. Populations of weedy crop–wild hybrid beets show contrasting variation in mating system and population genetic structure. Evol. Appl. 2010, 3, 305–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santín-Montanyá, I.; de Andrés, E.F.; Zambrana, E.; Tenorio, J.L. The competitive ability of weed community with selected crucifer oilseed crops. In Herbicides, Agronomic Crops and Weed Biology; Price, A., Kelton, J., Sarunaite, L., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Khamare, Y.; Chen, J.; Marble, S.C. Allelopathy and its application as a weed management tool: A review. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1034649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdoch, A. Sustainable Weed Control in Small Grain Cereals (Wheat/Barley). In Weed Control: Sustainability, Hazards and Risks in Cropping Systems Worldwide; Korres, N.E., Burgos, N.R., Duke, S.O., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; pp. 215–237. ISBN 9781498787468. Available online: https://centaur.reading.ac.uk/80098/ (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Löbmann, A.; Christen, O.; Petersen, J. Development of herbicide resistance in weeds in a crop rotation with acetolactate synthase-tolerant sugar beets under varying selection pressure. Weed Res. 2019, 59, 479–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweizer, E.E.; Westra, P. Potential for weeds to develop resistance to sugarbeet herbicides in North America. J. Sugar Beet Res. 1991, 28, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powles, S.B.; Yu, Q. Evolution in action: Plants resistant to herbicides. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2010, 61, 317–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Si, R.; Guo, S.; Waqas, M.A.; Zhang, B. Externalities of pesticides and their internalization in the wheat–maize cropping system A case study in China’s Northern Plains. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros-Rodríguez, A.; Rangseekaew, P.; Lasudee, K.; Pathom-Aree, W.; Manzanera, M. Impacts of agriculture on the environment and soil microbial biodiversity. Plants 2021, 10, 2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinke, G.; Karácsony, P.; Czúcz, B.; Botta-Dukát, Z. When herbicides don’t really matter: Weed species composition of oil pumpkin (Cucurbita pepo L.) fields in Hungary. Crop Prot. 2018, 110, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, I.K.S.; Storkey, J.; Sparkes, D.L. A review of the potential for competitive cereal cultivars as a tool in integrated weed management. Weed Res. 2015, 55, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molinari, F.A.; Blanco, A.M.; Vigna, M.R.; Chantre, G.R. Towards an integrated weed management decision support system: A simulation model for weed-crop competition and control. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 175, 105597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.U.; Khan, M.Z.; Khan, A.; Saba, S.; Hussain, F.; Jan, I.U. Effect of humic acid on growth and crop nutrient status of wheat on two different soils. J. Plant Nutr. 2018, 41, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasiroleslami, E.; Mozafari, H.; Sadeghi-Shoae, M.; Habibi, D.; Sani, B. Changes in yield, protein, minerals, and fatty acid profile of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) under fertilizer management involving application of nitrogen, humic acid, and seaweed extract. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2021, 21, 2642–2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çimrin, K.M.; Türkmen, Ö.; Turan, M.; Tuncer, B. Phosphorus and humic acid application alleviate salinity stress of pepper seedling. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2010, 9, 5845–5851. Available online: https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ajb/article/view/92903 (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Rose, M.T.; Patti, A.F.; Little, K.R.; Brown, A.L.; Jackson, W.R.; Cavagnaro, T.R. A meta-analysis and review of plant-growth response to humic substances: Practical implications for agriculture. Adv. Agron. 2014, 124, 37–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalteh, M.; Norouzi, H.A.; Faraji, A.; Haghighi, A.A.; Alamdari, E.G. Effect of plant density, humic acid and weed managements on yield, yield components and water use efficiency in direct-seeded rice (Oryza sativa) production. Rom. Agric. Res. 2021, 38, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balbaa, M.G.; Awad, A.M. Effect of humic acid and micronutrients foliar fertilization on yield, yield components and nutrients uptake of maize in calcareous soils. J. Plant Prod. 2013, 4, 773–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Wang, C.; Wang, F.; Xie, Y. Maize (Zea mays) growth and nutrient uptake following integrated improvement of vermicompost and humic acid fertilizer on coastal saline soil. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2019, 142, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izhar Shafi, M.; Adnan, M.; Fahad, S.; Wahid, F.; Khan, A.; Yue, Z.; Danish, S.; Zafar-ul-Hye, M.; Brtnicky, M.; Datta, R. Application of single superphosphate with humic acid improves the growth, yield and phosphorus uptake of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) in calcareous soil. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Guo, W.; Xu, L.; Shi, L. Beneficial effect of humic acid urea on improving physiological characteristics and yield of maize (Zea mays L.). Acta Physiol. Plant. 2022, 44, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, S.M.; Kerven, L.; Edwardsand, D.G.; Ostatek Boczyski, Z. Characterisation of fulvic and humic acids from leaves of Eucalyptus comaldulensis and from decomposed hey. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2000, 32, 1331–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Fang, F.; Wei, J.; Wu, X.; Cui, R.; Li, G.; Zheng, F.; Tan, D. Humic acid fertilizer improved soil properties and soil microbial diversity of continuous cropping peanut: A three-year experiment. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 12014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Cheng, X.; Zhang, Y. The impact of humic acid fertilizers on crop yield and nitrogen use efficiency: A meta-analysis. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekin, Z. Integrated use of humic acid and plant growth promoting rhizobacteria to ensure higher potato productivity in sustainable agriculture. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, Z.H.; Rehman, H.M.; Akhtar, T.; Alsamadany, H.; Hamooh, B.T.; Mujtaba, T.; Daur, I.; Zahrani, Y.A.; Alzahrani, H.A.S.; Ali, S.; et al. Humic substances: Determining potential molecular regulatory processes in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevisan, S.; Francioso, O.; Quaggiotti, S.; Nardi, S. Humic substances biological activity at the plant–soil interface: From environmental aspects to molecular factors. Plant Signal. Behav. 2010, 5, 635–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korotkova, I.; Marenych, M.; Hanhur, V.; Laslo, O.; Chetveryk, O.; Liashenko, V. Weed control and winter wheat crop yield with the application of herbicides, nitrogen fertilizers, and their HA-SWEs with humic growth regulators. Acta Agrobot. 2021, 74, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goryanina, T. Statistical correlations in winter triticale hybrids. Acta Agrobot. 2019, 72, 1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampong, K.; Thilakaranthna, M.S.; Gorim, L.Y. Understanding the role of humic acids on crop performance and soil health. Front. Agron. 2022, 4, 848621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardi, S.; Ertani, A.; Francioso, O. Soil–root cross-talking: The role of humic substances. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2017, 180, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, M.; Baigorri, R.; González-Gaitano, G.; García-Mina, J.M. New methodology to assess the quantity and quality of humic substances in organic materials and commercial products for agriculture. J. Soils Sediments 2018, 18, 1389–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Tang, C.; Antonietti, M. Natural and artificial humic substances to manage minerals, ions, water, and soil microorganisms. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 6221–6239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Li, R.; Peng, S.; Liu, Q.; Zhu, X. Effect of humic acid on transformation of soil heavy metals. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 207, 012089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bybordi, A.; Ebrahimian, E. Growth, yield and quality components of canola fertilized with urea and zeolite. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2013, 44, 2896–2915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Bassiouny, H.S.M.; Bakry, B.A.; El-Monem Attia, A.A.; Abd Allah, M.M. Physiological role of humic acid and nicotinamide on improving plant growth, yield, and mineral nutrient of wheat (Triticum durum L.) grown under newly reclaimed sandy soil. Agric. Sci. 2014, 5, 687–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A.; Lal, R.; Zimmerman, A.R. Impacts of 1.5-year field aging on biochar, humic acid, and water treatment residual amended soil. Soil Sci. 2014, 179, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelapa, T.; Banyuasin, K. Effects of humic substances on plant growth and mineral nutrients uptake of wheat under conditions of salinity. Asian J. Crop Sci. 2016, 1, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollenbeek, L.; Van Der Weide, R. Prospects for Humic Acid Products from Digestate in the Netherlands; Report WPR-867; Wageningen University & Research: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 5–40. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Mattson, N. Effects of seaweed extract application rate and method on post-production life of petunia and tomato transplants. HortTechnology 2015, 25, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitz, S.R.; Trumble, J.T. Effects of cytokinin-containing seaweed extract on Phaseolus lunatus L.: Influence of nutrient availability and apex removal. Bot. Mar. 1996, 39, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matysiak, K.; Kaczmarek, S.; Krawczyk, R. Influence of seaweed extracts and HA-SWE of humic and fluvic acids on germination and growth of Zea mays L. Acta Sci. Pol. Agric. 2011, 10, 33–45. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, O.; Ramsubhag, A.; Jayaraman, J. Biostimulant properties of seaweed extracts in plants: Implications towards sustainable crop production. Plants 2021, 10, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayorath, P.; Khan, W.; Palanisamy, R.; MacKinnon, S.L.; Stefanova, R.; Hankins, S.D.; Critchley, A.T.; Prithiviraj, B. Extracts of the brown seaweed Ascophyllum nodosum induce gibberellic acid (GA3)-independent amylase activity in barley. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2008, 27, 370–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, V.S.; Sharma, V.; Sharma, S.; Rana, N.; Kumar, V.; Sharma, U.; Almutairi, K.F.; Avila-Quezada, G.D.; Abd _Allah, E.F.; Gudeta, K. Seaweed extract as a biostimulant agent to enhance the fruit growth, yield, and quality of kiwifruit. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, O.; Ramsubhag, A.; Jayaraman, J. Biostimulatory activities of Ascophyllum nodosum extract in tomato and sweet pepper crops in a tropical environment. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0216710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saudi, A.H. Effect of foliar spray with seaweeds extract on growth, yield and seed vigour of bread wheat cultivars. Iraqi J. Agric. Sci. 2017, 48, 886–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossini, A.; Ruggeri, R.; Rossini, F. Combining nitrogen fertilization and biostimulant application in durum wheat: Effects on morphophysiological traits, grain production, and quality. Ital. J. Agron. 2025, 20, 100027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanmayi, C.S.N.; Biswas, R.; Reddy, M.S.L.; Bindu, V.K.; Mitra, B. Influence of seed treatment and foliar spraying of seaweed extracts on wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) in Terai region of West Bengal. J. AgriBiotech Sustain. Dev. 2024, 16, 246–254. Available online: https://epubs.icar.org.in/index.php/JWR/article/view/152738 (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Abdel-Sattar, M.; Mostafa, L.Y.; Rihan, H.Z. Enhancing mango productivity with wood vinegar, humic acid, and seaweed extract applications as an environmentally friendly strategy. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Saif, A.M.; Sas-Paszt, L.; Awad, R.M.; Mosa, W.F. Apricot (Prunus armeniaca) performance under foliar application of humic acid, brassinosteroids, and seaweed extract. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- As, A.A.; Na, S.; Maa, R. Effect of humic acid and seaweed extract rates on yield and yield components of barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). Alex. Sci. Exch. J. 2023, 44, 459–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canellas, L.P.; Olivares, F.L. Physiological responses to humic substances as plant growth promoter. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2014, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, F.; Khan, I.; Ashraf, U.; Shahzad, T.; Hussain, S.; Shahid, M.; Abid, M.; Ullah, S. Effects of organic and inorganic manures on maize and their residual impact on soil physico-chemical properties. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2017, 17, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowry, C.J.; Smith, R.G. Weed control through crop plant manipulations. In Non-Chemical Weed Control; Zimdahl, M., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 73–96. [Google Scholar]

- Varanini, Z.; Pinton, R. Plant-Soil Relationship: Role of Humic Substances in Iron Nutrition. In Iron Nutrition in Plants and Rhizospheric Microorganisms; Barton, L.L., Abadia, J., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stybayev, G.; Zargar, M.; Serekpayev, N.; Zharlygassov, Z.; Baitelenova, A.; Nogaev, A.; Mukhanov, N.; Elsergani, M.I.M.; Abdiee, A.A.A. Spring-Planted Cover Crop Impact on Weed Suppression, Productivity, and Feed Quality of Forage Crops in Northern Kazakhstan. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oerke, E.C.; Dehne, H.W. Safeguarding production—Losses in major crops and the role of crop protection. Crop Prot. 2004, 23, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, A.L.; Power, J.F. Effect of chemical and mechanical fallow methods on moisture storage, wheat yields, and soil erodibility. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1965, 29, 465–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, A.L. (Ed.) Methods of Soil Analysis: Part 2. Chemical and Microbiological Properties, 2nd ed.; Agronomy Monograph 9; American Society of Agronomy, Soil Science Society of America: Madison, WI, USA, 1982; ISBN 978-0-89118-072-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, B.M.; Al Maliki, A.; Alraheem, E.A.; Al-Janabi, A.M.S.; Halder, B.; Yaseen, Z.M. Temperature and precipitation trend analysis of the Iraq region under SRES scenarios during the twenty-first century. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2022, 148, 881–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muter, S.A.; Al-Jiboori, M.H.; Al-Timimi, Y.K. Assessment of spatial and temporal monthly rainfall trend over Iraq. Baghdad Sci. J. 2025, 22, 910–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krähmer, H.; Andreasen, C.; Economou-Antonaka, G.; Holec, J.; Kalivas, D.; Kolářová, M.; Novák, R.; Panozzo, S.; Pinke, G.; Salonen, J.; et al. Weed surveys and weed mapping in Europe: State of the art and future tasks. Crop Prot. 2020, 129, 105010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. parallel: Support for Parallel Computation in R; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Khalaf, H.S.M.; Idan, W.J.; Khashan, A.A.; Hassan, A.A. Response of European wheat to weed competitiveness as affected by potassium fertilizer levels. J. Agric. Sci.–Sri Lanka 2023, 18, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).