Abstract

Globularia alypum L. (Plantaginaceae) is widespread in the Mediterranean region and traditionally used against diabetes, digestive disorders, infections, and skin problems. This review summarizes its botanical features, ethnobotanical uses, phytochemistry, pharmacological effects, and toxicological profile. Relevant studies published between 1991 and 2024 were retrieved from Web of Science, Scopus, PubMed, and other relevant databases using targeted keywords in English and French. Extracts of G. alypum have shown significant antidiabetic, antioxidant, anticancer, antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, anticoagulant, nephroprotective, and wound-healing activities in vitro and in vivo, which were largely attributed to its diverse secondary metabolites such as phenolics, flavonoids, and iridoids. Toxicological studies indicate generally low risk at tested doses. However, further research is needed to elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying these activities, validate its efficacy through clinical trials, and evaluate long-term safety, thereby bridging traditional knowledge with modern pharmacological evidence.

1. Introduction

Since early times, phytotherapy has incited scientific interest for the wide range of natural substances extracted from medicinal plants [1,2,3]. It has been proved that many of these plants do have a strong potential as alternative medications against various infectious diseases to be advantageous for food preservation and in the cosmetic industries [1,4,5].

In the last two decades, a focus on the link between plant phytoconstituents and human health has taken considerable place. Phytochemical substances such as vitamins, polyphenols, flavonoids, and phytosterols are acknowledged to prevent innumerable human diseases [6,7].

Thanks to its rich and diverse flora, the traditional pharmacopoeia in Morocco provides a wide arsenal of plant remedies [8]. Moroccan people have a long therapeutic tradition related to a rich traditional know-how of plant medications, which forms a part of their civilization [2,8]. There are about 800 taxa potentially used as aromatic and medicinal plants in Morocco [2,9].

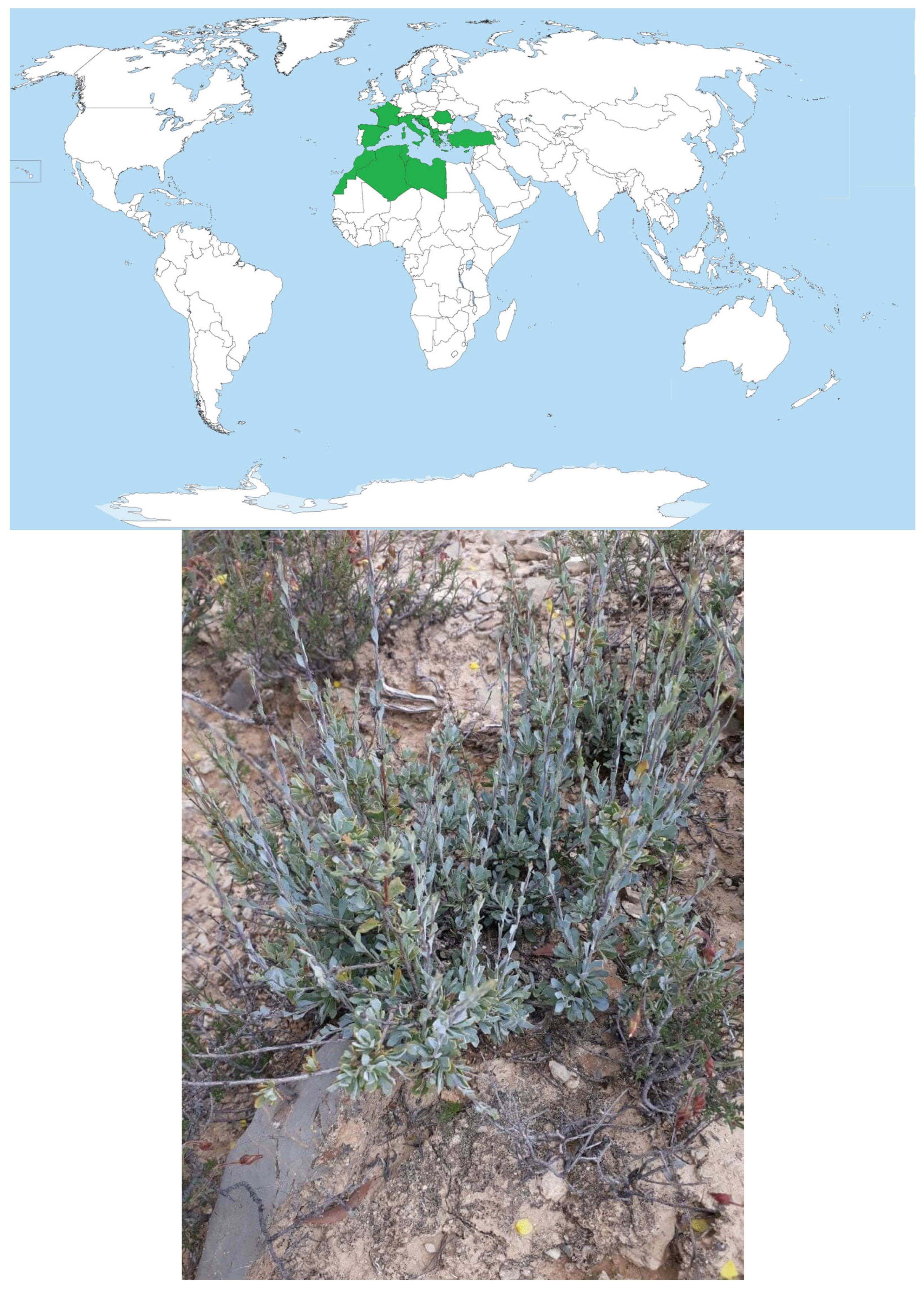

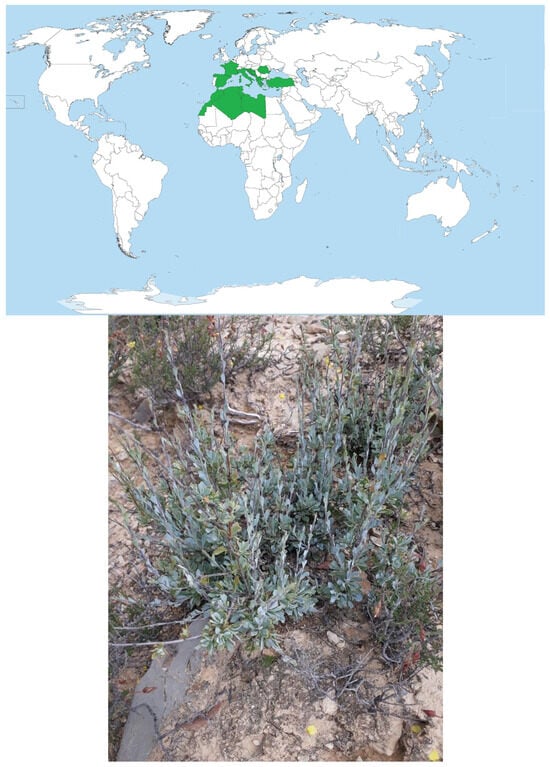

The family Plantaginaceae (Globulariaceae) is formed by shrubs or sub-shrubs with zygomorphic flowers [10]. In Morocco, there is one genus and three species, namely G. naini Batt. and G. liouvillei Jahand. & Maire, both endemic [10,11], whereas the third one, G. alypum L., is common in shrublands of Mediterranean climate regions [10,12,13] and is native to Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Turkey, Serbia, Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, North Macedonia, Slovenia, Albania, Baleares, Corse, East Aegean, Greece, Italy, Kriti, Sardinia, Sicilia, France, and Spain (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution area of Globularia alypum in the world and illustration of the species collected in Taza region, northern Morocco.

Globularia alypum L. (Alypo Globe Daisy, G. alypum hereafter) is a wild perennial evergreen shrub [10,13]. It has erected ligneous stems, its leaves are spatulate, lanceolate, or slightly tridentate at the apex; the flowers are purplish blue with a very short upper lip and perceptible and imbricate bracts [10,14]. It is a seeder and resprouting species [14]. In Morocco, G. alypum is found in Tetraclinis articulata (Vahl) Masters and Pinus halepensis Miller forest stands, as well as in scrublands and matorrals, in Infra- and Meso-Mediterranean vegetation belts from the plains up to altitudes around 1800 m, under the hot and fresh variants of the semi-arid and subhumid bioclimates, and it often grows on calcareous and superficial soils [10].

Known locally as” Taselgha” or” Ain Larneb” (i.e., rabbit’s eye), G. alypum constitutes one of the most remarkable herbs not only in Moroccan [8,15,16] but also in Arab folk medicine such as Algerian [6,17,18] and Tunisian [19,20]. Ethnobotanical surveys revealed that the treatment of numerous diseases using this medicinal plant is common across different Moroccan regions, including oriental [21,22] north center (Fez–Boulemane: [8]; Meknès-Tafilalet: [23]; Al Haouz-Rhamna: [24]; Sefrou: [25]; central Middle Atlas: [26]; southern (Tafilalet: [27]; Souss Massa Draa: [5]; Taroudant: [28]; Sahara (Tan-Tan: [29], and more recently in northern region (Taza: [3]). In traditional medicine, ethnobotanical surveys reported that G. alypum is widely used, either as decoction or infusion, against various health disorders and diseases. Indeed, it is used as cholagogue, hypoglycemic, laxative, purgative, stomachic, stimulant, depurative, diuretic, and sudorific agent, as well as in the treatment of diabetes, anemia, boils, intermittent fever, constipation, arthritis, skin diseases especially eczema, gout, rheumatism, intermittent fever, typhoid, renal, and cardiovascular disorders [6,8,13,20,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37].

Different phytochemical analyses indicated that G. alypum encompasses numerous classes of bioactive compounds such as phenolic compounds [3,4,7,13,14,20,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44], phenylethanoids [13,35,37,45,46], phenylethyl glycosides [47,48], flavonoids [3,4,5,7,13,14,19,20,35,38,39,41,42,43,45,48,49], terpenoids [4], anthocyanins [20,38,43,50], iridoids [3,35,37,45,46,48,51], tannins [7,19,43], coumarins [19], sterols [19], phytosterols [7], and secoiridoids [35], as well as volatile compounds [3]. In addition, the important nutritional value of the species is noticeable thanks to the presence of four vitamins (i.e., D, K, E, and A), several minerals (mainly Ca, Na, K, Fe, Mn, Zn, and Mg), five sugars (i.e., arabinose, fructose, glucose, sucrose, and maltose), and high protein contents [7].

Numerous in vitro and in vivo investigations using different parts of the plant (i.e., leaves, flowers, stems, and branches), have proved that G. alypum extracts, and to a lesser extent essential oils, had several biological effects such as antioxidant [1,3,5,6,13,14,19,20,34,38,39,40,41,42,45,52,53], antihyperglycemic [4,8,18,34,41,42,51,54], antibacterial [1,40,41,43,55], anti-inflammatory [40,46,56,57], burn wound healing [40], antiproliferative and cytotoxic [20], antihypertriglyceridemic and antihypercholesterolemic [4,51,58], anti-ulcer [59], antifungal [1,3,41], antiviral [60], vasodilatory [61], antileukemic [62], good protection against lipid peroxidation [4,20], spermatogenesis activation [63], as well as inhibition of radical-induced red blood cell hemolysis inhibition [6,42]. Furthermore, the plant has been reported to be active against neoplastic cell culture [37,64], and constipation [65]. It is also reported to decrease plasma lipids, creatinine, urea, transaminases activities [34], and nifuroxazide genotoxicity in Escherichia coli [19].

Most of its biological activities have been linked to the different bioactives formerly described in G. alypum, such as phenolic compounds and iridoids [13,14,19,40,42,43,45,66,67]. Compared to other medicinal plants, G. alypum was found to be among the species with the highest total phenolic levels [5,6,7], and thus the highest antioxidant activity [1,7,39].

Recently, several review papers have explored the properties of medicinal plants such as Thymus satureioides Coss. [68], Matricaria chamomilla L. [69], Centaurium erythraea Rafn. [70], Daphne gnidium L. [71], Chenopodium album L. [72], Bulbophyllum spp. [73], Chamaerops humilis [74], and Crocus sativus [75]. Despite the abundant literature reporting the ethnomedicinal uses and pharmacological properties of G. alypum, to our knowledge, there is no systematic review on the use of G. alypum as a potential source of natural substances having diverse biological activities against several diseases and health disorders, which could drive future studies for this species.

The present narrative review aims to critically summarize all studies on ethnomedicinal uses, phytochemistry, and pharmacological activities of G. alypum, as well as to discuss future challenges and opportunities. Indeed, this review is not only important because it resumes the advances undertaken until present, but also it identifies the unexplored pharmacological effects of this plant species. This step seems to be crucial for future investigations, especially for addressing the mechanisms of action of G. alypum extracts and/or its essential oils. More specifically, more than 150 articles that investigated G. alypum, published between 1991 and 2024, were reviewed. At first, the ethnomedicinal uses of the species were assessed, followed by exploration of its phytochemical composition, and its pharmacological activities. Finally, the main gaps in the knowledge of biological potentialities of this species and future steps to fill in these gaps were highlighted.

2. Literature Search Methodology

The present narrative review gathers all relevant information on botanical description, ethnobotanical usage, phytochemical components, and pharmacological and toxicological properties of G. alypum. A literature search across Web of Science, Scopus, PubMed, and other databases, covering studies published between 1991 and 2024 in English and French, was conducted. The literature search was updated till December 2024. The search employed specific keywords, namely “antioxidant activities”, “antidiabetic effects”, “antimicrobial effects”, “anticancer effects”, “anti-inflammatory effects”, “antiproliferative effects”, and “wounds healing effects” in conjunction with G. alypum. The investigation prioritized titles as the initial criterion for identifying and reviewing the relevant literature. In cases where ambiguity arose from the study’s title and abstract, a thorough examination of the full text was undertaken.

3. Taxonomy, Botanical Description, and Distribution

Globularia alypum belongs to the order Lamiales, family Plantaginaceae (Syn. Globulariaceae), and Tribu Globularieae Rchb. (1837). The family is formed of shrubs or sub-shrubs with zygomorphic flowers [10]. In Morocco, there is one genus and three species, namely G. naini Batt. and G. liouvillei Jahand. & Maire, both endemic [10,11], whereas the third one, G. alypum L., is common in shrublands of Mediterranean climate regions [10,12,13,76], and is native to Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Turkey, Albania, Baleares, Corse, East Aegean, Greece, Italy, Kriti, Sardinia, Sicilia, France, and Spain (Figure 1). G. alypum is a wild perennial evergreen shrub [10,13]. It has erected ligneous stems, its leaves are spatulate, lanceolate, or slightly tridentate at the apex; the flowers are purplish blue with a very short upper lip and perceptible and imbricate bracts [10,14]. It is a seeder and resprouting species [14]. In Morocco, G. alypum is found in T. articulata and P. halepensis Mill. forest stands, as well as in scrublands and matorrals, in Infra- and Meso-Mediterranean vegetation belts from the plains up to altitudes around 1800 m, under the hot and fresh variants of the semi-arid and subhumid bioclimates, and it often grows on calcareous and superficial soils [10].

4. Ethnomedicinal Uses

Table 1 lists the parts, mode of preparation, and therapeutic uses of G. alypum, commonly used in traditional Moroccan, Algerian, and Tunisian medicine [8,77,78]. Medicinal utilization is related to its used parts. Interestingly, the most widespread usage is linked to its antidiabetic properties [28,79]. Ouhaddou et al. reported that the infusion, decoction, and the powder of the whole plant of G. alypum in the Agadir Ida Ou Tanane province of Morocco has been commonly used against digestive disorders, skin infections, and respiratory and urinary tract diseases [80]. In the Northeast of Morocco, the decoction of G. alypum leaves has been recommended by the local population against diabetes [81], and to manage kidney diseases [82]. Another survey, proposed by Fakchich et al., highlighted the use of G. alypum decoction and infusion against diabetes, allergy, and digestives diseases [83]; on the hand, in the city of Agadir, El-Ghazouani et al. discussed the use of G. alypum for burns healing [84]. In Algeria G. alypum has been used for diabetes [77,85], but also as anti-jaundice [86], antihypertensive, astringent, digestive, sudorific, cholagogue, depurative, diuretic, laxative, and diaphoretic [36,87,88,89]. In the Taza province the decoction of G. alypum leaves has been reported against stomach pain, rheumatism, carminative, purgative, anxiolytic, and as menstrual-pain analgesic [90]. The infusion of G. alypum has been used instead by the Ksar Lakbir population for bilious stimulation [91] and against skin cancer [92]. Traditionally, G. alypum has been used primarily for the management of diabetes, digestive disorders, and skin ailments, with additional applications reported for urinary, circulatory, and inflammatory conditions. These dominant ethnomedicinal indications correlate closely with its main classes of bioactive metabolites: iridoids and phenylethanoid glycosides, which have demonstrated antidiabetic, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant activities; flavonoids, which are associated with antioxidant and skin-protective effects; and terpenoids, which may contribute to digestive and antimicrobial properties. This integrative perspective underscores a clear link between traditional knowledge and the pharmacological potential of the plant, supporting the rationale for its continued use and further experimental investigation.

Table 1.

Ethnomedicinal uses of G. alypum.

5. Phytoconstituents of G. alypum

G. alypum phytochemistry was extensively studied in the literature (Table 2 and Table 3). The main focus was on organic extracts chemical profiling of various plant parts (leaves, flowers, stem, and underground parts). An overview of the peer-reviewed literature is summarized in Table 2. Friščić et al. performed a comparative phytochemical study of four Globularia species collected in Croatia. These authors reported that the level of all secondary metabolites is significantly (p < 0.05) higher in G. punctata, G. cordifolia, and G. meridionalis as compared to those of G. alypum. According to the same authors, G. punctata contains the greatest concentration of total flavonoids (48.49–63.03 mg QE/g DE) as well as iridoids (343.33–440.04 mg AE/g dry extract (DE)). With respect to the other studied species, the aerial parts from G. alypum contained the highest amount of TPC (112.34 mg GAE/g DE). No significant variations (p > 0.05) in TPC and TFC were observed between G. cordifolia and G. meridionalis extracts. As demonstrated by Friščić et al., G. alypum is a rich source of flavonoids, iridoids, lignans, and phenylethanoids among others. Major metabolites were represented by globularin and verbascoside [124]. Some works, carried out by liquid chromatography in combination with mass spectrometry (LC-MS) highlighted important quantitative differences in major compounds in the leaf and aerial part extracts; considering the shrubby nature of this plant, such variations could be assigned partially to a relatively high share of stems of G. alypum aerial parts subjected to extraction. Also, the stems of G. alypum were found to be less rich in terms of secondary metabolites than their leaves and flowers [50,125,126,127]. In a study by Kırmızıbekmez et al., three new phenylethyl glycosides were isolated from G. alypum leaves, along with two known phenylethyl glycosides, calceolarioside A and verbascoside, and eight iridoid glucosides, all identified by 1D- and 2D-NMR and HR-MALDI-MS [47].

Friščić et al. employed LC-MS/MS for the analysis of the methanolic extracts of the aerial parts obtained from four Globularia species leading to the identification of up to 85 compounds, mainly represented by globularin, globularifolin, asperuloside, and verbascoside. While studying hypoglycemic and hypolipidemic activities of G. alypum leaves, collected in Achba-Tlemcen, Algeria, during the species fructification period (July), Merghache et al. (2023) isolated globularin, an iridoid glucoside, from the plant leaves (3.4%) [128]. Likewise, Sertić et al. used a similar analytical platform for the analysis of the methanolic extracts from four Globularia species. Two iridoid glucosides, viz. aucubin and catalpol, were positively identified. Flowers had the greatest amount of investigated iridoids and catalpol content being 1.6% in G. punctata flowers. Compared to G. alypum, the other related species presented a major amount of the iridoid content [129]. Finally, Mamoucha et al. employed UHPLC-HRMS analysis for the elucidation of the chemical pattern and seasonal variations of G. alypum collected in Greece. A total of 24 compounds belonging to iridoids, flavonoids, and phenylethanoid glycosides were positively identified. Regarding iridoids, (E)-globularicisin was the most abundant one (up to 70%). According to the same authors, total iridoid was raised by 48.1% in summer. In a similar trend, flavonoid anabolism was more active for the same period, with less noticeable seasonal variation accounting for about 25.6%. On the other hand, a sharp fall (33.5%) of phenylethanoids was observed for the summer season [48]. Based on the compiled data, iridoids such as globularin, globularifolin, and aucubin/catalpol appear to be the most consistent candidate marker compounds distinguishing G. alypum from other Globularia species. In addition, the relative abundance of phenylpropanoid derivatives and certain flavonoids suggests a chemotype tendency characteristic of G. alypum within the genus.

Table 2.

Phytoconstituents of G. alypum extracts.

Table 2.

Phytoconstituents of G. alypum extracts.

| Plant Part | Region | Chemical Composition of Organic Extracts/Essential Oil (Major Components) | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leaves, flowers, woody stems, and underground parts of four G. alypum L. species | Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina | Aucubin (0.58–0.92 mg/g DM) in ME Catalpol (1.79–12.85 mg/g DM) in ME | [129] |

| Leaves | Algeria (Bajaia) | Hydroxyluteolin 7-Olaminaribioside, Gallocatechin/ Epigallocatechin, Eriodictiol 7-O-sophoroside, Quercetin glucoside, Luteolin sophoroside, Cynaroside, Amurensin, Nepitrin, Phellamurin. | [130] |

| Aerial parts | Morocco (Taza) | Syringin, four phenylethanoids, four flavonoids and six iridoids | [45] |

| Aerial parts | Morocco (Taza) | Iridoids globularin, globularicisin, globularidin, globularinin, globularimin, chlorinated iridoid glucoside (globularioside) | [37] |

| Leaves | Tunisia (Gafsa) | Decaffeoylverbascoside, Caffeoyl hexoside 1, 6-O-caffeoyl-b-D-glucopyranosyl-(1-6)-glucitol (hebitol II), Caffeoyl hexoside 2, Syringin, Caffeoyl hexoside, Coumaroyl hexosyl glucitol, 6-O-caffeoyl-3,4-dihydrocatalpol, (dihydroverminoside), 6-O-feruloyl-b-D-glucopyranosyl-(1-6)-glucitol (globularitol), 6-O-Caffeoylcatalpol, 6-Hydroxyluteolin 7-O-laminaribioside, Specioside, 6-Hydroxyluteolin 7-O-glucoside, Luteolin di-hexoside, Globularinin, Globularimin, Calceolarioside A/calceolarioside B, Rossicaside A, Luteolin 7-O-glucoside (cynaroside), Verbascoside or acteoside isomer 1, Calceolarioside A/calceolarioside B, Caffeoyl hexoside derivative, 6-Methoxyluteolin-7-O-glucoside (nepitrin), Globularicisin, Methylcaffeoyl derivative, Verbascoside or acteoside isomer 2, Globularidin, Hydroxyphenylethyl-caffeoyl-hexoside, Diydroxyphenylethyl-coumaroyl-hexoside, Globularin, Dihydroxyphenylethyl-methylcaffeoyl-hexoside, 6-Methoxyluteolin (nepetin), Martynoside, Globularioside, Hydroxyphenylethyl-methylcaffeoyl-hexoside, 6-O-caffeoylverbascoside, Galypumoside A, Galypumoside B, Galypumoside C | [131] |

| Aerial parts | Croatia (Konavle cliffs, Grobnik field, Baške Oštarije, Velebit, Alan, Velebit) | Leaves extracts TPC = 130.46 ± 5.99–131.39 ± 2.89 mg GAE/g dry extract (DE, ME) using ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE) TFC = 30.43 ± 0.29- 32.26 ± 1.37 mg QE/g DE (ME) using UAE Iridoids 12.07 ± 0.18–27.49 ± 3.08 mg aucubin equivalents (AE)/g DE (ME) using UAE Condensed tannins: 2.66 ± 0.09–3.00 ± 0.06 mg catechin equivalents (CE)/g DE using UAE Aerial parts (flowers and stems) extracts TPC = 112.34 ± 2.17 mg GAE/g DE ME using Soxhlet extraction. TFC = 26.85 ± 0.46 mg QE/g DE ME using Soxhlet extraction. LC-MS profile for Methanolic leaf extracts (UAE) from G. alypum Mannitol, sucrose, catalpol, aucubin, 1′-O-Hydroxytyrosol glucoside, Caffeoylglucoside isomer, Hebitol II (6′ -O-Caffeoyl-β-D-glucopyranosyl-(1→6)-mannitol), Globularitol (6′ -O-Feruloyl-β-D-glucopyranosyl-(1→6)-mannitol), Verminoside (6-O-Caffeoylcatalpol), Geniposide, Vicenin-2 (Apigenin-6,8-di-C-glucoside), Specioside (6-O-(p-Coumaroyl)-catalpol), 6-Hydroxyluteolin 7-O-sophoroside, 6-Hydroxyluteolin 7-O-glucoside, Alpinoside, Globularinin, Globularimin, Liriodendrin ((+)-Syringaresinol di-O-β-glucopyranoside), Isoquercitrin (Quercetin 3-O-glucoside), Calceolarioside A, Calceolarioside B, Nepetin 7-O-glucoside, Rossicaside A, Verbascoside, Globularidin, Isoverbascoside, Forsythoside A, Globularin (10-O-trans-Cinnamoylcatalpol), Leucosceptoside A, 6′ -O-Feruloyl-10 -O-hydroxytyrosol glucoside, Globularioside, Alpinoside-alpinoside dimer, Globusintenoside isomer, Desrhamnosyl 6′ -O-caffeoylverbascoside, 6′ -O-Caffeoylverbascoside, Globuloside A (Alpinoside-globularin dimer), Galypumoside B (6′ -O-Feruloylverbascoside), Desrhamnosyl galypumoside B, Oxo-dihydroxy-octadecenoic acid, Galypumoside C, Trihydroxy-octadecenoic acid LC-MS profile for Methanolic aerial parts extracts (Soxhlet) from G. alypum Mannitol, sucrose, catalpol, Caffeoylglucoside isomer, Gardoside, Verminoside (6-O-Caffeoylcatalpol), Geniposide, Specioside, 6-Hydroxyluteolin 7-O-sophoroside, 6-Hydroxyluteolin 7-O-glucoside, Alpinoside, Globularinin, Globularimin, Liriodendrin ((+)-Syringaresinol di-O-β-glucopyranoside), Calceolarioside A (Desrhamnosyl verbascoside), Calceolarioside B, Rossicaside A, Verbascoside, Isoverbascoside, Forsythoside A, Globularin (10-O-trans-Cinnamoylcatalpol), Leucosceptoside A, 6′ -O-Feruloyl-10 -O-hydroxytyrosol glucoside, Globularioside, Globusintenoside isomer, 6′ -O-Caffeoylverbascoside, Apigenin, Globuloside A, Galypumoside B | [125] |

| Fresh leaves | Tunisia (Beja region) | Yield (%) 14.20 ± 0.28, total sugars (%) 71.56 ± 0.64, Sulfate (%) 13.29 ± 0.84 Proteins (%) 0.74 ± 0.02, Lipids 1.45 ± 0.08, Moisture (%) 7.53 ± 0.35, Ash (%) 6.8 ± 0.62 | [132] |

| Fresh leaves | Tunisia (Beja region) | Methanolic extracts: Glycerol, tris (TMS) ether (2.65%), Cinnamic acid, TMS ester (1.53%), Cinnamic acid (1.32%), Cinnamic acid, (E) (0.32%), Cinnamic acid, TMS ester (23.21%), 4-Hydroxyphenylethanol, di-TMS (4.70%), Ethanol, (2-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)-, tris(TMS) (6.61%), D-Fructose, 1,3,4,5,6-pentakis-O- (TMS) (12.24%), 3,4-Heptadien-2-one, 3,5-dicyclopentyl-6-methyl- (12.46%), Bicyclo [4.4.0]dec-2-ene-4-ol, 2-methyl-9-(prop-1-en-3-ol-2-yl) (30.96%), Talose, 2,3,4,5,6-pentakis-O-(TMS)- (0.62%), Palmitic acid, TMS ester (6.07%), Silane, [(3,7,11,15-tetramethyl-2-hexadecenyl)oxy] TMS (0.47%), Linoleic acid, TMS ester (0.40%), Oleic acid, TMS ester (1.48%), Stearic acid, TMS ester (0.75%), 1-(3′, 5′ -dichlorophenyl)-5-oxo-4,4-diphenyl-2-imidazolin-2-yl] guanidine (0.3%) | [40] |

| Dried aerial parts | Croatia | α-himachalene (35.34%), β-himachalene (13.62%), γ-himachalene (12.6%), cedrol (10.32%), isocedranol (5.52%) and α-pinene (5.5%) | [128] |

| Aerial part (flowers, leaves and stems) | Algeria (Batna) | Diethyl ether (TPC = 331.88 ± 17.80 µg GAE/mg DE), TFC = 223.46 ± 2.37 µg CE/mg DE) Ethyl acetate (TPC = 103.62 ± 1.09 µg GAE/mg DE), TFC = 139.58 ± 4.08 µg CE/mg DE) n-butanol (TPC = 127.70 ± 0.82 µg GAE/mg DE), TFC = 173.5 ± 4.71 µg CE/mg DE) Gallic acid, p-coumaric acid, rutin, naringenin and quercitin (diethyl ether fraction) Gallic acid, quercetin, rutin, and ferulic acid (ethyl acetate fraction) | [42] |

| Aerial (flowers, leaves, and woody stems) and underground parts | Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina | Methanolic extracts (ultrasonic extraction) Aucubin (mg/g DE): Leaves 0.58 ± 0.01, Flowers 0.92 ± 0.00, Woody stems 0.58 ± 0.01 Catalpol (mg/g DE): Leaves 1.79 ± 0.03, Flowers 12.58 ± 0.03, Woody stems 1.47 ± 0.02 | [129] |

| Fresh aerial parts | Morocco (Taza) | Aqueous MeOH extract: Phenolics: 6-hydroxyluteolin 7-O-laminaribioside, eriodictyol 7-O-sophoroside, and 6′- O-coumaroyl-1′-O-[2-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl) ethyl]-β-D-glucopyranoside, Phenylethanoid glycosides: acteoside, isoacteoside, and forsythiaside Flavonoid glycosides: 6-hydroxyluteolin 7-O-β-D-glucopyranoside and luteolin 7-O-sophoroside | [13] |

| Fresh leaves | Morocco (Taza) | Ethyl acetate: TPC = 56.5 ± 0.61 µg GAE/mg of extract, TFC = 30.2 ± 0.55 µg CE/mg of extract Chloroform: TPC = 18.9 ± 0.48 µg GAE/mg of extract, TFC = 18.0 ± 0.36 µg CE/mg of extract n-hexane fraction (CG-MS): A total of 73 compounds: the major compounds were n-hexadecanoic acid (13.5%), oleic acid (12.98%), and linoleic acid (11.58%) Ethyl acetate extract (HPLC-DAD-ESI/MS): Gallic acid (4.3 ± 0.12 mg/100 g), Gallic acid ethyl ester (4.2 ± 0.20 mg/100 g), Quercetin glucoside (4.7 ± 0.20 mg/100 g), Quercetin rhamnoside (14.5 ± 1.20 mg/100 g), Kaempferol derivative (10.8 ± 0.50 mg/100 g), Quercetin acetyl hexoside (0.3 ± 0.01 mg/100 g), Quercetin glucoside (7.8 ± 0.30 mg/100 g) | [3] |

| Aerial parts | Tunisia (Seliana) | Ethanolic extracts TPC = 23.95 ± 0.24 (mg GAE/g DE), TFC = 11.93 ± 0.05 (mg CE/g DE) and TCT = 21.43 ± 0.38 (mg CE/g DE) RP-HPLC/UV of ethanolic extracts: Phenolic acids: p-coumaric acid (15.02 ± 1.55 mg/g DE), Sinapic acid (3.62 ± 0.03 mg/g DE), Trans-hydroxycinnamic acid (34.21 ± 3.24 mg/g DE) Flavonoids: Quercetin (0.11 ± 0.00 mg/g DE), Catechin hydrate (16.01 ± 1.87 mg/g DE) | [133] |

| Dried whole plant | Switzerland | Methanolic/aqueous extracts: globularicisin, globularidin, globularimin, globularinin, lignan diglucoside liriodendrin, syringin, globularin, catalpol | [134] |

| Fresh leaves | Algeria (Souk Ahras) | Petroleum ether extract (GC-MS): Ethylbenzene, Xylene, D-Fenchone, Camphor, alpha-Terpineol, Neohexane, alpha-Fenchyl acetate, n-Tetradecane, Sabinyl acetate, 1-Ethyl-1,5-cyclooctadiene, Eugenol, Isoeugenol, Diethylmethyl-borane, Eicosane, 17-Pentatriacontene, Nonadecane, Pentadecane, n-Octadecyl chloride, Bicyclopentyl-2′-en-2-yl-dimethylamine, 3-Cyclopentyl-pentane, Lignocerol, Viridiflorol, Cetane, alpha-Cadinol, Aromadendrene, 2,2-Dimethyl-6,10-dithiaspiro [4.5] decan-1-ol, Hexatriacontane, Neoclovene, Dehydroionone Amphetamine oxime acetate, Phthalic acid | [135] |

| Dried leaves | Tunisia (Boussalem) | Aqueous extract: Catalpol, Shanzhizide, Hebitol, Globuralitol, Varminoside, Gallocatechin, Quercetin-glucoside, Verbascoside, Isoverbascoside, Decumbeside, Phellamurin, Serratoside, Globularioside | [46] |

| Leaves | Tunisia (Zaghouan) | Ethanolic extracts: TPC 25.33 ± 1.52 mg GAE/g DW, TFC 4.71 ± 0.50 mg CE/g DW, tannins 4.30 ± 0.35 mg CE/g DW HPLC-PDA-ESI-MS/MS: p-coumaroyl sugar ester, Apigenin acetoxydeoxyhexose, Tetragalloyl hexoside, HHDP-hexose, Sinapic acid derivative, Apigenin glucuronide, Amentoflavone, I3, II8-Biapigenin, Myricetin, Kaempfreol glucoside, Naringenin diglucoside | [136] |

| Leaves | Greece (Athens) | UHPLC- (-) ESI/HRMS: Gardoside/Geniposidic Acid, Cornoside, Mussaenosidic acid, (epi)loganic acid, Secoxyloganin methylester, Acetylbarlerin, Globularitol, Hydroxyluteolin diglucoside, Eriodictiol diglycoside, Luteolin diglycoside, Quercetin glucoside, Alpinoside, Verbascoside, Agnuside, Globularinin, Calceolarioside B, Isoverbascoside, Nepitrin, Gallocatechin/Epigallo- catechin, (Z)-Globularicisin, Globularidin, (E)-Globularicisin, Globularioside/Baldac-cioside, Verminoside | [48] |

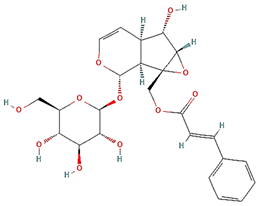

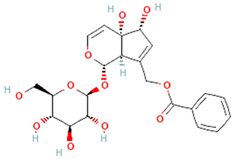

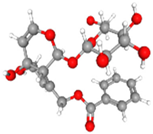

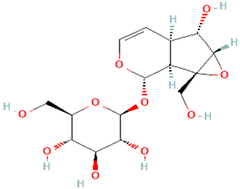

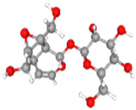

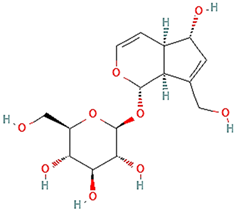

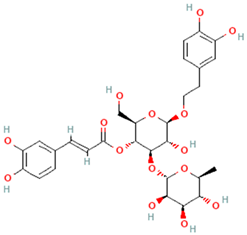

Table 3.

Representative bioactive compounds of Globularia alypum showing their 2D and 3D structures.

Table 3.

Representative bioactive compounds of Globularia alypum showing their 2D and 3D structures.

| Compound Name | 2D Structure | 3D Structure |

|---|---|---|

| Globularin |  |  |

| Globularifolin |  |  |

| Catalpol |  |  |

| Aucubin |  |  |

| Verbascoside |  |  |

6. Pharmacological Activities

6.1. Antioxidant Activity

Oxidative processes, such as energy production, fat metabolism, alcohol and drug detoxification, and digestion, naturally generate free radicals in the human body. While endogenous antioxidant systems work to neutralize these species, excessive accumulation may disrupt cellular processes, damage membranes and DNA, and impair energy metabolism [137]. Oxidative stress has been associated with the progression of various metabolic, chronic disorders, and cancers [138,139,140]. Antioxidants are molecules capable of stabilizing free radicals, thereby limiting their potential harmful effects [141,142].

As summarized in Table 4, extracts from different parts, namely leaves, fruit, and seeds, of G. alypum have been explored through DPPH, FRAP, β-carotene, and ABTS. In a vitro study, Asraoui et al. studied the antioxidant capacity of the organics extracts of Moroccan G. alypum using DPPH, ABTS, and FRAP assays. The crude extracts from G. alypum leaves collected from Taza region revealed attractive antioxidant effect (IC50 = 12.3 ± 3.83 µg/mL for DPPH test, IC50 = 37.0 ± 2.45 µg/mL for ABTS test, and 531.1 ± 1.08 mg AAE/g DW for FRAP test) for the EtOAc extract [3]. Such results agree with the study by Khantouche et al. on the ethanolic extract of Tunisian G. alypum leaves expressing an IC50 value of 29.8 ± 0.20 µg/mL and 42.53 ± 0.24 µg/mL, respectively, for DPPH and β-carotene assays; however, the ABTS assay showed a value of 89.5 ± 0.32 mg EVC/g DW, compared to Vitamin C, Vitamin E, and BHT [143]. Another work revealed that the diethyl ether extract from the aerial part of G. alypum yielded an antioxidant activity, corresponding to an IC50 value of 20.54 ± 0.48 µg/mL and an EC50 value of 283.7 ± 82.59 µg/mL for DPPH and FRAP tests, respectively, lower with respect to the standard ascorbic acid (IC50 = 3.74 ± 0.11 µg/mL, EC50 = 79.3 ± 2.08 µg/mL, respectively) [42]. A remarkable anti-DPPH effect (IC50 = 4.95 ± 0.94 µg/mL) compared to ascorbic acid (IC50 = 0.89 ± 0.06 mg/mL) was found in a study conducted by Touaibia et al. on leaves ethanolic extracts [40]. In another study, focused on the roots, leaves, and steams ethyl acetate and methanolic extracts of G. alypum, harvested from Taounat region of Morocco, IC50 values as high as 33.67 µg/mL, 48.28 µg/mL, and 18.85 µg/mL, respectively, compared with the positive control BHT (3.32 µg/mL) were obtained. Roots extract of G. alypum yielded a higher IC50 value followed by steams, and leaves (10.01 µg/mL vs. 22.11 µg/mL vs. 25.65 µg/mL) [144]. Feriani et al. reported, for the methanolic extract of G. alypum leaves, a moderate anti-DPPH activity with an IC50 value of 203 ± 1.83 µg/mL compared to IC50 = 168.85 ± 2.05 µg/mL and an EC50 of 15.25 ± 0.49 mg/mL for ABTS and reducing power, respectively [131]. In addition to leaves, flowers of G. alypum were investigated by Chograni et al. [14], reporting RSA and FRAP values ranging from 230 to 295 µmol TEAC/g and from 24.27 to 21.81 mmol Fe2+/L, respectively. Notably, different extracts, namely aqueous, methanol, petroleum ether, and ethyl acetate extracts from G. alypum leaves, were exploited by Harzallah et al. [19], highlighting the major antioxidant results for the aqueous extract (8.9 mM TE).

Table 4.

Antioxidant results of G. alypum extracts.

6.2. Antimicrobial Activity

Excessive and incorrect antibiotic usage has led to antimicrobial resistance, a significant global concern and threat to humanity. Traditional pharmacological therapies are losing effectiveness, prompting the development of new antimicrobial medicines based on natural metabolites for their chemical variety and efficacy. They suppress pathogen growth, including bacteria, fungi, and viruses, and enhance antibiotic efficacy, potentially overcoming antimicrobial resistance [149]. For this reason, different extracts of G. alypum have been subjected to several antimicrobial investigations.

Table 4 summarizes all studies that studied the antibacterial and antifungal activity of G. alypum, including the used part, type of extract, antimicrobial methods, tested microorganisms, and results. Various works showed the antibacterial potential of organic extracts and essential oil from different parts of G. alypum; Krimat et al. evaluated in vitro the antibacterial activity of hydroethanolic extract of G. alypum collected from Setif, Algeria against four bacterial strains and one yeast. Notably, B. subtilis, S. aureus, and C. albicans turned out to be the most sensitive to the extract with a diameter of inhibition zone ranging from 9.0 to 11.0 mm. However, no inhibitory effect was observed for E. coli and P. aeruginosa [1]. A larger study was carried out by Boussoualim et al., who studied the antibacterial effect of Algerian G. alypum different extracts against 11 bacterial strains (P. aeruginosa, E. coli, S. typhimurium, A. baumanii, C. freundii, P. mirabilis, K. pneumoniae, S. aureus, B. cereus, E. faecalis, and L. monocytogenes). Methanol (CrE), chloroform (ChE), and ethyl acetate (AcE) extracts revealed the highly inhibitory potential; particularly, ChE and AcE extracts were found the most active. Aqueous (AqE) extracts presented a poor effect of inhibition. AcE and CrE were the most active towards S. aureus, with an inhibition zone diameter of 16 and 15 mm, respectively; on the other hand, ChE against S. aureus had an inhibition zone diameter of 13 mm, whereas 12 mm was obtained towards A. baumanii. The lowest effect on the totality of bacteria was attained for the aqueous extract, except towards K. pneumoniae [150]. Ghlissi et al. examined the antibacterial activity of leaves methanolic extracts by means of agar-well diffusion assay against six microorganisms, three Gram-positive and three Gram-negative bacteria species, at a concentration of 50 mg/mL, using ampicillin as positive control. The potent antibacterial activity could be explained by the dominance of cinnamic acid compounds (26.38%), and in particular, the occurrence of cinnamic acid-TMS ester (23.21%) [40]. The aqueous extracts of G. alypum, obtained by four extraction methods, against four bacterial strains, isolated from patients with urinary infections, compared to antibiotics (Kanamicin, Colistin, Amoxillin, Gentamicin and Ampicillin), served as standards and was carried out by Bouabdelli et al. The bacterial strains tested were E. coli, P. mirabilis, P. aeruginosa, and S. aureus using the disc diffusion method. The results demonstrated that all the extracts showed a positive effect, and all the tested bacteria were sensitive to G. alypum extracts with an inhibition zone diameter ranging from 7 mm to 15 mm with a concentration of 50 mg/mL. Such results highlight the importance of the method extraction on the antibacterial potential of plant extracts [151]. Another study proved the antibacterial properties of the ethyl acetate and methanol extracts from different parts of plant (leaves, stems, and root) against selected bacteria strains. Notably, only the ethyl acetate extracts showed inhibitory effects against M. luteus. In addition, the ethyl acetate extract of roots turned out to be the most active with a MIC value of 0.5 mg/mL against both bacterial strains; on the other hand, the MBC values of the extracts were equal to the MIC values, showing a positive bactericidal effect. B. subtilis was more susceptible to the methanolic extracts of roots and stems, differently from S. aureus, being more sensitive to leaves methanolic extract [144]. An interesting work carried out on the essential oil obtained from the aerial parts of G. alypum collected by two localities against seven Gram negative bacteria and five Gram positive bacteria using macro-dilution assay was reported by Ramdani et al. The results showed a variable antimicrobial effect of the tested oil against all clinical bacteria pathogens. The essential oil of Boutaleb and Khenchela populations presented important potential against Gram-negative bacteria with a moderate inhibition against A. baumanii. A low activity was obtained against K. pneumoniae and P. mirabilis, whereas S. aureus, B. cereus, K. pneumoniae, and P. mirabilis were found to be resistant to this essential oil [55]. The antimicrobial and antifungal effects of the hydro-alcoholic and aqueous leaf extracts of G. alypum collected from the region of Laghouat, Algeria, was investigated by Kraza et al. Up to five bacterial strains (S. aureus, E. faecalis, P. aeruginosa, E. coli, and S. typhi) and three pathogenic fungal strains (Aspergillus flavus, Penicillium spp., and Fusarium oxysporum) were tested and the authors reported the inhibition of the growth against strains tested of ethyl acetate, butanol, and aqueous extracts at different concentrations (50, 60, 80, and 100 mg/mL). The antibacterial effect was proportional to the concentration of the extract, and the ethyl acetate extract exhibited meaningly the highest antibacterial action against all pathogenic bacteria, with a maximum inhibition zone (15.5 ± 0.2 against P. aeruginosa) [41].

The antibacterial potential of G. alypum of methanolic extracts of aerial parts obtained by Soxhlet extraction was reported by Frišcic et al. Considering the former method, G. alypum had the highest inhibitory activity against S. aureus (25.0 mm), whereas lower against B. cereus, B. subtilis, and P. aeruginosa (8.3 mm, 7.7 mm, and 9.7 mm); on the other hand, considering the latter, the assessed MIC value against S. aureus ATCC 6538 was reported with a MIC of 1.42 mg/mL, whereas a comparable antibacterial activity was attained against methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MIC = 2–4 mg/mL) [125]. Recently, research conducted by Asraoui et al. examined the antifungal and antibiofilm properties of leaf extracts from of G. alypum against Candida, both in vitro and in vivo. Such a study assessed the ability of these extracts to inhibit the growth of Candida albicans and Candida glabrata in their planktonic and sessile forms. Additionally, an in vivo infection model involving Galleria mellonella larvae infected with Candida and treated with the extracts was conducted. All tested extracts exhibited strong fungicidal activity with minimum fungicidal concentrations (MFC) ranging from 128 to 512 μg/mL. It is noteworthy that the methanolic extracts demonstrated the lowest MFC value (128 μg/mL), capable of effectively inhibiting 90% of biofilm formation. In vivo experiments on Galleria mellonella larvae indicated that the extracts might enhance the survival rate of larvae infected with Candida, holding promise as novel antifungal and biofilm-inhibiting agents for applications in pharmaceuticals and agro-food industries [152]. The differences in the inhibition zone diameter (expressed in mm), along with MICs, and MBCs values of the extracts versus a varied range of bacterial and fungal strains, listed in Table 5, could be explained by the difference in the chemical composition of the different extracts. In particular, the used solvent, the plant part, and the origin of species significantly impacted the variety and the level of bioactive compounds and consequently might affect the antimicrobial capacity.

Table 5.

Antimicrobial results of G. alypum extracts.

6.3. Anti-Hyperglycemic Activity

Oral anti-hyperglycemic agents are often associated with adverse effects, leading sometimes in drug discontinuation [153]. In such a context, phytotherapy provides a valuable opportunity for the discovery of novel natural molecules capable of avoiding the harmful effects of synthetic therapeutic agents.

G. alypum is described as a well-known antidiabetic plant in traditional medicine in Morocco. The leaves of this plant are usually prepared by infusion or decoction (according to the region) [8,21,24,27,31,83,154,155]. The antidiabetic effect of G. alypum extracts was reported by in vitro investigations of several researchers showing how the main compounds do possess antidiabetic effect by increasing insulin secretion in addition to controlling the synthesis of hepatic glycogen, and the regulation of glycemia.

Ouffai et al. evaluated the inhibitory effect of several G. alypum extracts against α-amylase and α-glucosidase. The diethyl ether fraction yielded the most satisfactory inhibitory properties against both α-amylase (IC50 = 0.57 ± 0.05 mg/mL) and α-glucosidase (IC50 = 0.52 ± 0.02 mg/mL) with respect to acarbose served as a positive control. Such effects, especially on insulin secretion, were correlated to the phenolic content of the plant extracts [42].

Zennaki et al. evaluated the antidiabetic activity of the aerial parts extracts of G. alypum. In STZ-induced diabetic rats, the administration of G. alypum extract significantly reduced blood glucose and glycosylated hemoglobin levels. The treatment with the G. alypum methanolic extract revealed a notable reduction in GSH levels in liver, brain, and kidney [34].

In 2014, Djellouli et al. evaluated the effects of G. alypum methanolic extract on glycaemia, and reverse cholesterol transport, in addition to lipoprotein peroxidation in STZ-induced diabetic rats. As a result, they found that after 28 days of treatment with the methanolic extract of G. alypum, there was a notable hypoglycemic effect; however, the blood glucose level reached a mean value of 5.32 ± 0.15 mmol/L, in comparison to 27.83 ± 0.41 mmol/L obtained in the diabetic group. The increased serum insulin levels in G. alypum treated diabetic rats was inferred by the authors to the insulinotropic molecules occurring in G. alypum extract that persuade the whole functional β-cells of the Langerhans islet to produce insulin [4]. Skim et al. studied the hypoglycemic effect of the aqueous extract of G. alypum leaves alloxan-diabetic rats. The infusion of G. alypum leaves demonstrated a hypoglycemic effect after both oral and intraperitoneal administration. Such an effect was like common hypoglycemic compounds, e.g., metformin and glibenclamide, at a concentration of 11.3 and 0.13 mg/kg, respectively [54]. Merghache et al. studied the hypoglycemic effect of globularin isolated from G. alypum. Notably, a single intraperitoneal administration of globularin at a dose 100 mg/kg body weight produced the maximum decrease in blood glucose levels [51]. In a recent study, Tiss et al. assessed the in vitro antidiabetic effect of G. alypum extracts (methanol and water), via the inhibition of α-amylase activity. Notably, the methanolic extract exhibited the highest anti-α-amylase activity with half inhibitory concentration IC50 = 2.97 mg/mL [156]. On the other hand, the study of Jouad et al. demonstrated that oral administration of the aqueous extract of G. alypum leaves did not change blood glucose levels in normal rats, differently from streptozotocin (STZ) diabetic rats, where a significant decrease in blood glucose levels was noticed [157]. Another recent study of Frišcic et al. reported the effect of G. alypum methanolic extracts against α-glucosidase activity, and the results showed the effectiveness of G. alypum at the concentrations tested (0.5 and 1.0 mg/mL) with a percentage of inhibition ranging from 30.0 to 45.7% [125].

A thorough work was carried out by Tiss and Hamden on the effect of G. alypum methanolic and aqueous leaves extracts on hyperglycemia, pancreas, liver, kidney, testes, and bone tissue.

The pancreas tissue was destroyed after administration of alloxan, and despite this, destruction was minimized in GAWE and GAME diabetic-treated rats [158].

6.4. Anti-Inflammatory Activity

Inflammation is an important process in the immune system that plays a crucial role in the body’s defense mechanism against harmful stimuli [159]. However, when inflammation becomes excessive, it can lead to health problems and the development of various diseases [160]. In the last case, the inhibition of inflammation represents a physiological mechanism that is naturally implicated or can be targeted via treatments. This process is of high importance to the treatment of inflammatory diseases or illnesses linked to excessive inflammation such as cancer and autoimmune diseases [161,162]. Vegetables and fruits, rich in antioxidants and polyphenols, showed a great ability to protect against inflammation [163,164]. In addition, a considerable number of medicinal plants, such as Allium sativum and Pinus pinaster, are known for their anti-inflammatory activity as a source of anti-inflammatory compounds [165,166,167]. G. alypum is one of the medicinal plant species of the Mediterranean region that possesses an anti-inflammatory activity (Table 6). Ethnobotanical studies reported that G. alypum is used in the treatment of many diseases related to inflammation such as rheumatism, arthritis, eczema, and colic [17,35,168]. In addition, this species is used in the treatment of burns and wounds by the Moroccan population [84,136].

Studies showed that G. alypum has an important anti-inflammatory effect through the reduction in lipid peroxidation, pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6 and TNF-α) levels, nuclear factor NF-kB expression and cyclooxygenase and lipoxygenase (key-enzymes linked to pain and inflammation) activity, with the amelioration of the reverse cholesterol transport [4,56,169,170]. In addition, G. alypum significantly decreases the C-reactive protein levels, used as a marker of inflammation [40]. As results, G. alypum extracts have been found able to prevent lipid disorder in STZ-induced diabetic and in hypercholesterolemia rats [4,169], as well as showing an anti-inflammatory effect on human colon [170]. Moreover, oral administration of G. alypum extract in rats induced a noticeable reduction in the ulcer index (UI) of gastric lesions produced by EtOH-HCl from 2.66 to 1.66 mm, resulting in recovery of the gastric mucosa with a percentage of protection of 30% and a healing rating of 37.59% [133].

In fact, the methanolic extract of G. alypum leaves showed a potent inhibitory activity against 5-lipoxygenase enzyme with an IC50 value of 79 mg/L [56], and against cyclooxygenase-1 enzyme with a percentage inhibition of 51.3% in the TMPD assay and 40.6% in the PGE2 assay at a concentration of 50 µg/mL [125]. In contrast, another study showed that the methanolic extract of G. alypum leaves presented a weak inflammatory activity, with a cyclooxygenase-1 inhibition by only 5.33% at a concentration of 33 µg/mL, while the flowers showed a potent inhibition of cyclooxygenase-1 enzyme by 61.05% with an IC50 value of 0.122 mg/mL at the same concentration (33 µg/mL) [35]. To our knowledge, there are no further studies comparing the anti-inflammatory activity of G. alypum leaves and flowers to confirm the results of Amessis-Ouchemoukh and collaborators.

The methanolic extract of G. alypum leaves inhibited inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) expression and NO production by 45% at a concentration of 150 mg/L and by 66% at 600 mg/L in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages [56]. However, Ben Mansour et al. found that the ethanolic extract of G. alypum leaves has a moderate inhibitory effect on NO generation (29% at a concentration of 200 mg/mL) in comparison to methanolic extract [133]. The anti-inflammatory activity of G. alypum was tested in vivo against carrageenan-induced paw oedema. The results showed a significant reduction in oedema size and swelling in the groups treated with G. alypum extracts in comparison to the control groups in a dose- and time-depending manner [40,57,171]. The methanolic extracts of the aerial part of G. alypum decreased the oedema volume from 64 to 28 μL with a percentage inhibition of 56.2% at a concentration of 500 mg/kg in mice [171], while at a concentration of 200 mg/kg the paw size deceased significantly by 40% in rats [40]. In addition, the flavonic extract of G. alypum exhibited a percentage inhibition of paw oedema of 33.01% at a concentration of 0.3 g/mL in mice [57].

The anti-inflammatory effect of G. alypum could be linked to many compounds detected in their extracts and that are known for their anti-inflammatory activity such as cinnamic acids [172], catalpol and its derivatives like globularin [173], liriodendrin [174], and verbascoside [175]. However, as in most medicinal plants, the chemical composition of G. alypum might change according to different factors such as season, geographical origin, environment conditions, and part of plant, which explains the heterogeneity in obtained results in terms of efficiency according to plant part and chemical composition.

Table 6.

Anti-inflammatory results of G. alypum extracts.

Table 6.

Anti-inflammatory results of G. alypum extracts.

| Part Used | Extracts | Experimental Approach | Key Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aerial part | Flavonic extract (Butanolic fraction) | Carrageenan-induced inflammation | Reduction in paw oedema volume by 8.55% at a concentration of 0.1 g/mL 27.15% at a concentration of 0.2 g/mL 33.01% at a concentration of 0.3 g/mL | [57] |

| Aerial part | Methanol extract | Carrageenan-induced inflammation | Inhibition by 56.2% | [171] |

| Leaves | Methanol extract | Carrageenan-induced inflammation. and Determination of C-reactive protein | Reduction in paw oedema volume by 40% A significant decrease in the inflammatory cells and C-reactive protein (CRP) level in serum samples | [40] |

| Leaves and flowers | Methanol extract | Cyclooxygenase inhibition | Flower: Cox-1 IC50 = 0.122 Cox-1 inhibition by 61.05% at a concentration of 0.033 mg/mL Leaves: Cox-1 inhibition by 5.33% at a concentration of 0.033 mg/mL | [35] |

| Leaves | Ethanol extract | Nitric oxide (NO) production | Decreases the cellular nitric oxide (NO) generation by 29% at 200 mg/mL Decreases the ulcer index (UI) from 2.66 mm to 1.66 mm | [133] |

| Leaves | Methanol extract | Lipoprotein peroxidation assay | Reduction in VLDL-LDL peroxidation up to 47% | [169] |

| Leaves | Methanol extract | Cyclooxygenase inhibition (TMPD and PGE2 assays) | COX-1 inhibition by 51.3% in TMPD assay COX-1 inhibition by 40.6% in PGE2 assay | [125] |

| Leaves | Aqueous extract | Cyclooxygenase inhibition and proinflammatory markers expression | Decrease in the COX-2 expression and EC-LPS effect on colon proinflammatory proteins | [170] |

| Leaves | Methanol extract | 5-lipoxygenase assay and nitric oxide (NO) production | Inhibition of 5-lipoxygenase: IC50 = 79 ± 0.8 mg/L NO production by 66% at 600 mg/L | [56] |

| Aerial part | Aqueous extract | Dosage of tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) | Decrease in lipid peroxidation and pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6 and TNF-α) levels | [169] |

6.5. Antiproliferative and Cytotoxic Activities

Cancer has historically been considered one of the most severe human diseases, primarily due to its elevated rates of morbidity and mortality [176]. Conventional cancer treatments such as radiotherapy, surgery, and chemotherapy have, to some extent, saved lives; however, their effectiveness is hindered by severe side effects and high rates of relapse, limiting their ability to control and, in certain cases, cure tumors. Consequently, there is an urgent need for the development of more diverse and effective medications from various sources, as emphasized by Jemal et al. [176]. Natural compounds derived from plants are gaining attention for their lower toxicity and high selectivity toward targets compared to synthetic chemotherapeutic drugs. Therefore, exploring the potential of medicinal plants as anticancer agents is crucial. G. alypum has exhibited notable anticancer potential, as evidenced by multiple studies demonstrating potent effects of various extracts against tumor cell lines. Nouir et al. investigated the antiproliferative effects of G. alypum leaf extracts on SW620 at various concentrations, revealing concentration-dependent inhibition of cell line proliferation. The methanolic extract, obtained through sonication, demonstrated the highest antiproliferative effect, with an IC50 value of 20 µg/mL after 48 h of incubation [148]. Likewise, Friscic et al. evaluated the anticancer potential of methanolic leaves extracts from G. alypum, against the A1235 glioblastoma cell line using the MTT assay, resulting in a promising IC50 value of 231.43 µg/mL [125].

6.6. Other Activities

The process of wound healing presents four sequential phases: homeostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling. These stages involve intricate biological and chemical mechanisms that safeguard the wounded area against infections while fostering the regeneration of tissues. G. alypum, a plant with a history of use in traditional medicine for addressing surface wounds, underwent testing to evaluate its effectiveness in promoting wound healing.

The wound healing activity of G. alypum extract was investigated by Ghlissi et al. and they examined the burn wound healing activity of the methanolic extract of G. alypum, (GAME) on a group of 20 rats with burn induction during sixteen days of treatment. As a result, the macroscopic characteristics and size variations of burn wounds in rats treated with GAME (group specified) and other groups show that on day 4, the untreated burn-injured animals exhibited extensive areas of unhealed wounds. By day 16, these wounds were covered with irregularly dried burn eschar, displaying signs of wound contraction. In contrast, rats treated with GAME consistently demonstrated enhanced wound coverage by day 4, and this improvement persisted through day 16. Notably, the wound area significantly decreased in the GAME-treated group on day 12 and day 16 when compared to the untreated group. The visual observations align with variations in hydroxyproline content, as indicated in Table 6. The group treated with GAME exhibited an increased level of hydroxyproline (26.23 ± 1.90 mg/g of tissue), which suggests a more accelerated wound healing process compared to the untreated group. In the healed biopsies of the CC-treated group, significant tissue improvement was noted, with structured epidermal layers but persistent signs of inflammation. However, in the tissue sections of the GAME-treated group, the skin layers were clearly identified, with normal epidermis and dermis [40].

Ghlissi et al. evaluated the anticoagulant effect of the sulphated polysaccharide in vivo and in vitro, extracted from G. alypum leaves (GASP). The in vitro anticoagulant activity of GASP was performed by the activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), thrombin time (TT), and prothrombine time (PT) assays, and the in vivo anticoagulant activity of GASP was tested on male Wistar rats injected subcutaneously with 200 mg/kg b.w and 500 mg/kg b.w of GASP. Both doses of GASP demonstrate effective anticoagulant activities both in vitro and in vivo. Furthermore, toxicological assessments involving plasma transaminases, oxidative status, and liver tissue histopathology confirm the absence of hepatocyte necrosis, oxidative stress, or morphological alterations in the liver. Notably, GASP administered at 500 mg/kg body weight emerges as a more promising candidate for further evaluation, given its superior pharmacological and toxicological profile compared to doses of 200 mg/kg body weight and calciparin [132].

The nephroprotective effect was investigated using the methanolic extract derived from G. alypum leaves on adult male Wistar rats. Feriani et al. demonstrated the potential of the G. alypum methanolic extracts to mitigate the nephrotoxic effects induced by Deltamethrin in rats. G. alypum administration effectively restored disrupted parameters such as creatinine, urea, and uric acid levels caused by Deltamethrin treatment. Furthermore, G. alypum administration led to a reduction in kidney lipid peroxidation and protein carbonyl content, both of which were elevated by Deltamethrin exposure. These biochemical findings were supported by G. alypum ability to protect against DNA damage and its positive impact on kidney fibrosis, as observed in histopathological studies following deltamethrin administration. These outcomes align with the phytochemical composition of this plant, suggesting that G. alypum leaves may serve as a valuable source of antioxidants, contributing to potential health benefits [131].

In another study, Chokri and collaborators evaluated the myorelaxant and spasmolytic effects of the methanolic extract of G. alypum on rabbit jejunum. Methanolic extract has a relaxant and spasmolytic effect on rabbit jejunum, thus confirming the use of this plant on traditional medicine for the treatment of gastrointestinal disorders [61].

6.7. Toxicology and Safety

Ghlissi et al. evaluated the toxicity of G. alypum by inspection of plasma transaminases and the status of liver tissue of the sulfated polysaccharide extract from G. alypum leaves. Such a work confirmed that such compounds are not responsible for the negative changes in the liver [132]. The in vivo effect of the aqueous extract of G. alypum leaves was investigated to evaluate the acute toxicity in male Wistar rats based on their body weight at different concentrations (0, 2.5, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, and 14 g/kg). The LD50 value of the GA aqueous extract was 14.5 g/kg, appearing to have minimal detrimental effects in terms of LD50 values [157]. Moreover, Skim et al. investigated the acute and chronic toxicity of water extract of G. alypum leaves from Morocco on Wistar rats. For the evaluation of the acute toxicity, six different concentrations of the extract (1, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 g/kg bw) were administered orally to the rats, and for the chronic toxicity, the rat group was given, orally, 0.7 g/kg bw of the plant infusion daily for 8 weeks. All rats treated with different concentrations of the infusions of G. alypum remained alive during the 7 days of observation. This suggested that the LD50 of the infusion extract was higher than 10 g/kg. The infusion of the leaves of G. alypum at a dose of 0.7 g/kg exerted no ill effects during the treatment for 8 weeks [54]. In the study by Shanab and Auzi based on Lorke’s method of aqueous extract of Libyan G. alypum in albino mice, injected with different concentration of the extract viz., 10 mg/kg, 100 mg/kg, and 1000 mg/kg and 1600, 2900, and 5000 mg/kg body weight, no mortality was found [177]. In another study conducted by Fehri et al., it was demonstrated that even at a dose of 10,000 mg/kg, the extract does not cause death when supplied orally. The extract’s LD50 was reported to be 2750 and 2550 mg/kg when administered intraperitoneally to female and male mice, respectively [63].

These studies suggest that the different portions of the plant did not exhibit major side effects when compared to the doses examined, and further chronic toxicity studies are required to investigate the adverse consequences of G. alypum use for an extended period.

7. Conclusions

In this review, comprehensive information on the ethnobotanical uses, phytochemistry, pharmacology, and toxicological studies of Globularia alypum L. is summarized. This plant, abundant in the Mediterranean region, is employed by diverse populations for treating various ailments. Ethnobotanical surveys have highlighted a broad spectrum of applications influenced by the plant part used, the treated ailment, mode of use, and geographical region. The intimate relationship each population shares with the plant is evident, with knowledge transmission in traditional medicine forming the foundation for regional variations in its utilization.

The observed disparities in biological outcomes among regions can be attributed to variations in bioactive compounds expressed by G. alypum. Distinct environmental conditions affecting the plant’s chemical composition explain its diverse effects in different regions. Phytochemical analyses have identified a range of bioactive compounds, such as flavonoids, phenolic acids, lipids, alkanes, alcohols, and terpenoids. The chemical profile of G. alypum varies based on collection location, likely influenced by climatic factors affecting secondary metabolite synthesis and secretion through epigenetic control.

Promising results regarding antioxidant and anti-hyperglycemic effects have been reported. Studies indicate that phenolic compounds in G. alypum extracts play a crucial role, exhibiting notable antioxidant and antidiabetic actions. This underscores the significance of pharmacological research in uncovering novel natural molecules from this plant. G. alypum extracts also exhibit other biological activities, including anticancer and anti-inflammatory effects. While the plant shows efficacy against these pathologies, the precise pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic mechanisms remain unclear.

It should be noted that the present work is a narrative compilation summarizing the available knowledge rather than a systematic review. We therefore emphasize the need for future systematic investigations focusing on standardized extract characterization, study quality assessment, and structure–activity relationship analyses. Furthermore, comprehensive preclinical and clinical research remains essential to elucidate the mechanisms of action of G. alypum bioactive compounds, validate its pharmacological potential in clinical settings, and assess long-term safety to support its development as a standardized phytotherapeutic agent.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.A., M.B.-S., M.B. and E.H.S.; methodology, F.A., M.B.-S., M.B. and E.H.S.; validation, A.L., J.B. and F.E.M.; investigation, F.A., N.E.M. and I.B.; resources, F.E.M. and N.O.-L.; data curation, F.A., M.B.-S., M.B. and E.H.S.; writing—original draft preparation, F.A., M.B.-S., E.H.S. and M.B.; writing—review and editing, M.P.L., F.C. and F.E.M.; visualization, A.L., F.C. and F.E.M.; supervision, A.L. and F.E.M.; supervision, F.C. and F.E.M., project administration A.L., J.B. and F.E.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

The results of this paper are framed in the IM-PACK project, which is supported by the PRIMA Program. The PRIMA program is supported by the European Union.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Soumia, K.; Tahar, D.; Lynda, L.; Saida, B.; Chabane, C.; Hafidha, M. Antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of selected medicinal plants from Algeria. J. Coast. Life Med. 2014, 2, 478–483. [Google Scholar]

- Elachouri, M. Ethnobotany/ethnopharmacology, and bioprospecting: Issues on knowledge and uses of medicinal plants by Moroccan people. Chapter 5. In Natural Products and Drug Discovery; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 105–118. [Google Scholar]

- Asraoui, F.; Kounnoun, A.; Cadi, H.E.; Cacciola, F.; Majdoub, Y.O.E.; Alibrando, F.; Mandolfino, F.; Dugo, P.; Mondello, L.; Louajri, A. Phytochemical investigation and antioxidant activity of Globularia alypum L. Molecules 2021, 26, 759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djellouli, F.; Krouf, D.; Bouchenak, M.; Lacaille-Dubois, M.A. Favorable Effects of Globularia alypum L. Lyophilized Methanolic Extract on the Reverse Cholesterol Transport and Lipoprotein Peroxidation in Streptozotocin–Induced Diabetic Rats. Int. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. Res. 2014, 6, 758–765. [Google Scholar]

- El Guiche, R.; Tahrouch, S.; Amri, O.; El Mehrach, K.; Hatimie, A. Antioxidant activity and total phenolic and flavonoid contents of 30 medicinal and aromatic plants located in the South of Morocco. Int. J. New Technol. Res. 2015, 1, 263695. [Google Scholar]

- Djeridane, A.; Yousfi, M.; Nadjemi, B.; Boutassouna, D.; Stocker, P.; Vidal, N. Antioxidant activity of some Algerian medicinal plant’s extracts containing phenolic compounds. Food Chem. 2006, 97, 654–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athmouni, K.; Belghith, T.; El Fek, A.; Ayadi, H. Phytochemical composition and antioxidant activity of extracts of some medicinal plants in Tunisia. Int. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2016, 4, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouad, H.; Haloui, M.; Rhiouani, H.; El Hilaly, J.; Eddouks, M. Ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants used for the treatment of diabetes, cardiac and renal diseases in the North centre region of Morocco (Fez–Boulemane). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2001, 77, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fennane, M.; Tattou, M.I.; Valdés, B. Catalogue des plantes vasculaires rares, menacées ou endémiques du Maroc. Bocconea 1998, 8, 1–243. [Google Scholar]

- Benabid, A. Flore et Écosystèmes du Maroc. Evaluation et présentation de la Biodiversité; Ed. Ibis Press: Paris, France, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Rankou, H.; Culham, A.; Jury, S.L.; Christenhusz, M.J. The endemic flora of Morocco. Phytotaxa 2013, 78, 1–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quézel, P.; Santa, S. Nouvelle Flore de l’Algérie et des Régions Désertiques Méridionales; CNRS: Paris, France, 1962; Volume 1, pp. 11–12. [Google Scholar]

- Es-Safi, N.-E.; Khlifi, S.; Kerhoas, L.; Kollmann, A.; El Abbouyi, A.; Ducrot, P.-H. Antioxidant constituents of the aerial parts of Globularia alypum growing in Morocco. J. Nat. Prod. 2005, 68, 1293–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chograni, H.; Riahi, L.; Zaouali, Y.; Boussaid, M. Polyphenols, flavonoids, antioxidant activity in leaves and flowers of Tunisian Globularia alypum L. (Globulariaceae). Afr. J. Ecol. 2013, 51, 343–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benabid, A.; Bellakhdar, J. Relevés floristiques et catalogue des plantes médicinales dans le Rif occidental. Biruniya 1987, 3, 87–120. [Google Scholar]

- Hammiche, V.; Merad, R.; Azzouz, M. Phytothérapie Traditionnelle en Algérie. Plantes Toxiques à Usage Médicinal du Pourtour Méditerranéen; Springer: Paris, France, 2013; pp. 18–20. [Google Scholar]

- Boudjelal, A.; Henchiri, C.; Sari, M.; Sarri, D.; Hendel, N.; Benkhaled, A.; Ruberto, G. Herbalists and wild medicinal plants in M’Sila (North Algeria): An ethnopharmacology survey. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 148, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Telli, A.; Esnault, M.-A.; Khelil, A.O.E.H. An ethnopharmacological survey of plants used in traditional diabetes treatment in south-eastern Algeria (Ouargla province). J. Arid Environ. 2016, 127, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harzallah, H.J.; Neffati, A.; Skandrani, I.; Maaloul, E.; Chekir-Ghedira, L.; Mahjoub, T. Antioxidant and antigenotoxic activities of Globularia alypum leaves extracts. J. Med. Plants Res. 2010, 4, 2048–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, R.B.; Gargouri, B.; Gargouri, B.; Elloumi, N.; Jilani, I.B.; Ghrabi-Gammar, Z.; Lassoued, S. Investigation of antioxidant activity of alcoholic extract of Globularia alypum L. J. Med. Plants Res. 2012, 6, 4193–4199. [Google Scholar]

- Ziyyat, A.; Legssyer, A.; Mekhfi, H.; Dassouli, A.; Serhrouchni, M.; Benjelloun, W. Phytotherapy of hypertension and diabetes in oriental Morocco. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1997, 58, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alami, Z.; Aynaou, H.; Alami, B.; Hdidou, Y.; Latrech, H. Herbal medicines use among diabetic patients in Oriental Morocco. J. Pharmacogn. Phytother. 2015, 7, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Amrani, F.; Rhallab, A.; Alaoui, T.; Badaoui, K.; Chakir, S. Étude ethnopharmacologique de quelques plantes utilisées dans le traitement du diabète dans la région de Meknès-Tafilalet (Maroc). Phytothérapie 2010, 3, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benkhnigue, O.; Akka, F.B.; Salhi, S.; Fadli, M.; Douira, A.; Zidane, L. Catalogue des plantes médicinales utilisées dans le traitement du diabète dans la région d’Al Haouz-Rhamna (Maroc). J. Anim. Plant. Sci. 2014, 23, 3539–3568. [Google Scholar]

- Bousta, D.; Boukhira, S.; Aafi, A.; Ghanmi, M.; El-Mansouri, L. Ethnopharmacological Study of anti-diabetic medicinal plants used in the Middle-Atlas region of Morocco (Sefrou region). Int. J. Pharm. Res. Health Sci. 2014, 2, 75–79. [Google Scholar]

- Hachi, M.; Hachi, T.; Essabiri, H.; El Yaakoubi, A.; Zidane, L. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in the Central Middle Atlas region (Morocco). IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1090, 012027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddouks, M.; Maghrani, M.; Lemhadri, A.; Ouahidi, M.L.; Jouad, H. Ethnopharmacological survey of medicinal plants used for the treatment of diabetes mellitus, hypertension and cardiac diseases in the south-east region of Morocco (Tafilalet). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2002, 82, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katiri, A.; Barkaoui, M.; Msanda, F.; Boubaker, H. Ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants used for the treatment of diabetes in the Tizi n’Test region (Taroudant Province, Morocco). J. Pharmacogn. Nat. Prod. 2017, 3, 2472-0992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghourri, M.; Zidane, L.; Douira, A. Usage des plantes médicinales dans le traitement du Diabète Au Sahara marocain (Tan-Tan). J. Anim. Plant Sci. 2013, 17, 2388–2411. [Google Scholar]

- Balansard, J.; Delphant, J. La globulaire: Un purgatif oublié. Rev. De Phytothérapie 1948, 12, 213–234. [Google Scholar]

- Bellakhdar, J.; Claisse, R.; Fleurentin, J.; Younos, C. Repertory of standard herbal drugs in the Moroccan pharmacopoeia. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1991, 35, 123–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sijelmassi, A. Les Plantes Médicinales du Maroc, 3rd ed.; Fennec: Casablanca, Morocco, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Allali, H.; Benmehdi, H.; Dib, M.A.; Tabti, B.; Ghalem, S.; Benabadji, N. Phytotherapy of diabetes in west Algeria. Asian J. Chem. 2008, 20, 2701. [Google Scholar]

- Zennaki, S.; Krouf, D.; Taleb-Senouci, D.; Bouchenak, M. Globularia alypum L. lyophilized methanolic extract decreases hyperglycemia and improves antioxidant status in various tissues of streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. J. Complement. Integr. Med. 2009, 6, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amessis-Ouchemoukh, N.; Abu-Reidah, I.M.; Quirantes-Piné, R.; Rodríguez-Pérez, C.; Madani, K.; Fernández-Gutiérrez, A.; Segura-Carretero, A. Tentative characterisation of iridoids, phenylethanoid glycosides and flavonoid derivatives from Globularia alypum L. (Globulariaceae) leaves by LC-ESI-QTOF-MS. Phytochem. Anal. 2014, 25, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miara, M.D.; Bendif, H.; Rebbas, K.; Rabah, B.; Hammou, M.A.; Maggi, F. Medicinal plants and their traditional uses in the highland region of Bordj Bou Arreridj (Northeast Algeria). J. Herb. Med. 2019, 16, 100262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Es-Safi, N.-E.; Khlifi, S.; Kollmann, A.; Kerhoas, L.; El Abbouyi, A.; Ducrot, P.-H. Iridoid glucosides from the aerial parts of Globularia alypum L. (Globulariaceae). Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2006, 54, 85–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Khantouche, L.; Motri, S.; Mejri, M.; BenAbderabba, M. Evaluation of polyphenols and antioxidant properties of extracts Globularia alypum leaves. J. New Sci. Agric. Biotechnol. 2015, 24, 1086–1090. [Google Scholar]

- Boussoualim, N.; Krache, I.; Baghiani, A.; Trabsa, H.; Aouachria, S.; Arrar, L. Human xanthine oxidase inhibitory effect, antioxidant in vivo of Algerian extracts (Globularia alypum L.). Int. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. Res. 2016, 8, 645–650. [Google Scholar]

- Ghlissi, Z.; Kallel, R.; Sila, A.; Harrabi, B.; Atheymen, R.; Zeghal, K.; Bougatef, A.; Sahnoun, Z. Globularia alypum methanolic extract improves burn wound healing process and inflammation in rats and possesses antibacterial and antioxidant activities. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2016, 84, 1488–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraza, L.; Mourad, S.M.; Halis, Y. investigation of the antioxidant and antimicrobial effects of hydro-alcoholic and aqueous extracts of Globularia alypum L. Acta Sci. Nat. 2020, 7, 46–58. [Google Scholar]

- Ouffai, K.; Azzi, R.; Abbou, F.; Mahdi, S.; El Haci, I.A.; Belyagoubi-Benhammou, N.; Bekkara, F.A.; Lahfa, F.B. Phenolics compounds, evaluation of Alpha-amylase, alpha-glucosidase inhibitory capacity and antioxidant effect from Globularia alypum L. Vegetos 2021, 34, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khlifi, D.; Hamdi, M.; Hayouni, A.E.; Cazaux, S.; Souchard, J.P.; Couderc, F.; Bouajila, J. Global chemical composition and antioxidant and anti-tuberculosis activities of various extracts of Globularia alypum L. (Globulariaceae) leaves. Molecules 2011, 16, 10592–10603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touaibia, M.; Chaouch, F. ZGlobal chemical composition and antioxidative effect of the ethanol extracts prepared from Globularia alypum leaves. Nat. Technol. 2016, 2, 2–6. [Google Scholar]

- Es-Safi, N.-E.; Kerhoas, L.; Ducrot, P.H. Fragmentation study of globularin through positive and negative ESI/MS, CID/MS, and tandem MS/MS. Spectrosc. Lett. 2007, 40, 695–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajji, N.; Jabri, M.-A.; Tounsi, H.; Wanes, D.; Ali, I.B.E.H.; Boulila, A.; Marzouki, L.; Sebai, H. Phytochemical analysis by HPLC-PDA/ESI-MS of Globularia alypum aqueous extract and mechanism of its protective effect on experimental colitis induced by acetic acid in rat. J. Funct. Foods 2018, 47, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kırmızıbekmez, H.; Bassarello, C.; Piacente, S.; Çalış, İ. Phenylethyl glycosides from Globularia alypum growing in Turkey. Helv. Chim. Acta 2008, 91, 1525–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamoucha, S.; Tsafantakis, N.; Fokialakis, N.; Christodoulakis, N.S. A two-season impact study on Globularia alypum: Adaptive leaf structures and secondary metabolite variations. Plant Biosyst. 2018, 152, 1118–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutiti, A.; Benguerba, A.; Kitouni, R.; Bouhroum, M.; Benayache, S.; Benayache, F. Secondary metabolites from Globularia alypum. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2008, 44, 543–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassine, B.B.; Bui, A.M.; Mighri, Z.; Cave, A. Flavonoids and anthocyanins from Globularia alypum L. Plantes Med. Phytother. 1982, 16, 197–205. [Google Scholar]

- Merghache, S.; Zerriouh, M.; Merghache, D.; Tabti, B.; Djaziri, R.; Ghalem, S. Evaluation of hypoglycaemic and hypolipidemic activities of globularin isolated from Globularia alypum L. in normal and streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Oran, A.S.; Kochkar, N.; Raies, A. Biosystematics of two species of the genus Globularia L. in Jordan and Tunisia (Research Note). Dirasat Pure Sci. 1999, 26, 203–210. [Google Scholar]

- Khlifi, S.; El Hachimi, Y.; Khalil, A.; Es-Safi, N.; El Abbouyi, A. In vitro antioxidant effect of Globularia alypum L. hydromethanolic extract. Indian J. Pharmacol. 2005, 37, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skim, F.; Lazrek, H.B.; Kaaya, A.; El Amri, H.; Jana, M. Pharmacological studies of two antidiabetic plants: Globularia alypum and Zygophyllum gaetulum. Therapie 1999, 54, 711–715. [Google Scholar]

- Ramdani, M.; Lograda, T.; Ounoughi, A.; Chalard, P.; Figueredo, G.; Laidoudi, H.; El Kolli, M. Chemical composition, antimicrobial activity and chromosome number of Globularia alypum from Algeria. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2014, 3, 306–318. [Google Scholar]

- Khlifi, D.; Sghaier, R.M.; Laouni, D.; Hayouni, A.A.; Hamdi, M.; Bouajila, J. Anti-inflammatory and acetylcholinesterase inhibition activities of Globularia alypum. J. Med. Bioeng. 2013, 2, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutemak, K.; Safta, B.; Ayachi, N. Study of the anti-inflammatory activity of flavonic extract of Globularia alypum L. Acta Phys. Pol. A 2015, 128, 238. [Google Scholar]

- Taleb-Dida, N.; Krouf, D.; Bouchenak, M. Globularia alypum aqueous extract decreases hypertriglyceridemia and ameliorates oxidative status of the muscle, kidney, and heart in rats fed a high-fructose diet. Nutr. Res. 2011, 31, 488–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehri, B.; Aiache, J.M. Effects of Globularia alypum L. on the gastrointestinal tract. J. Nat. Prod. 2010, 3, 141–146. [Google Scholar]

- Soltan, M.M.; Zaki, A.K. Antiviral screening of forty-two Egyptian medicinal plants. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2009, 126, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chokri, A.; El Abida, K.; Zegzouti, Y.F.; Ben Cheikh, R. Endothelium-dependent vascular relaxation induced by Globularia alypum extract is mediated by EDHF in perfused rat mesenteric arterial bed. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2012, 90, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldes, G.; Prescott, B.; King, J.R. A potential antileukemic substance present in Globularia alypum. Planta Med. 1975, 27, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehri, B.; Aiache, J.M.; Ahmed, K.M. Active spermatogenesis induced by a reiterated administration of Globularia alypum L. aqueous leaf extract. Pharmacogn. Res. 2012, 4, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, R.; Moreno, L.; Primo-Yúfera, E.; Esplugues, J. Globularia alypum L. extracts reduced histamine and serotonin contraction in vitro. Phytother. Res. 2002, 16, 389–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fehri, B.; Tebbett, I.R.; Freiburger, B.; Karlix, J. The immunosuppressive effects of Globularia alypum extracts. Phytother. Res. 1996, 10, 539–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajji, N.; Wannes, D.; Jabri, M.A.; Rtibi, K.; Tounsi, H.; Abdellaoui, A.; Sebai, H. Purgative/laxative actions of Globularia alypum aqueous extract on gastrointestinal physiological function and against loperamide-induced constipation coupled to oxidative stress and inflammation in rats. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2020, 32, e13858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taskova, R.M.; Gotfredsen, C.H.; Jensen, S.R. Chemotaxonomy of Veroniceae and its allies in the Plantaginaceae. Phytochemistry 2006, 67, 286–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hachlafi, N.; Chebat, A.; Fikri-Benbrahim, K. Ethnopharmacology, phytochemistry, and pharmacological properties of Thymus satureioides Coss. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2021, 27, 6673838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Mihyaoui, A.; Esteves da Silva, J.C.; Charfi, S.; Candela Castillo, M.E.; Lamarti, A.; Arnao, M.B. Chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla L.): A review of ethnomedicinal use, phytochemistry and pharmacological uses. Life 2022, 12, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Menyiy, N.; Guaouguaou, F.-E.; El Baaboua, A.; El Omari, N.; Taha, D.; Salhi, N.; Shariati, M.A.; Aanniz, T.; Benali, T.; Zengin, G.; et al. Phytochemical properties, biological activities and medicinal use of Centaurium erythraea Rafn. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 276, 114171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khouchlaa, A.; El Menyiy, N.; Guaouguaou, F.-E.; El Baaboua, A.; Charfi, S.; Lakhdar, F.; El Omari, N.; Taha, D.; Shariati, M.A.; Rebezov, M.; et al. Ethnomedicinal use, phytochemistry, pharmacology, and toxicology of Daphne gnidium: A review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 275, 114124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]