Abstract

This study investigated how exogenous 2,4-epibrassinolide (EBR) and nitric oxide (NO) enhance the tolerance of cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) seedlings to NaHCO3-induced alkaline stress under hydroponic conditions. NaHCO3 exposure caused severe sodium toxicity, reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation, and photosynthetic inhibition, which, together, suppressed plant growth. Treatments with either EBR or NO significantly improved plant performance by alleviating these adverse effects. Both regulators enhanced the ROS scavenging system, maintained ionic homeostasis, and alleviated sodium toxicity. They also stimulated the activities of vacuolar H+-ATPase, H+-PPase, and plasma membrane H+-ATPase, and increased the accumulation of citric and malic acids, thereby sustaining higher photosynthetic efficiency under stress conditions. qRT-PCR analysis further revealed that EBR and NO upregulated SOS1 and NHX2 (sodium transporters) as well as PIP1;2 and PIP2;4 (aquaporins), confirming their involvement in ionic and osmotic regulation. Pharmacological experiments showed that application of NO synthesis inhibitors, including tungstate and L-NAME, as well as the NO scavenger cPTIO, markedly weakened the protective effects of EBR. In contrast, application of the brassinosteroid biosynthesis inhibitor brassinazole (BRz) only had a limited effect on NO-mediated stress tolerance. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that NO functions as a downstream signaling mediator of EBR, coordinating multiple defense pathways including photosynthetic regulation, antioxidant protection, ion balance, aquaporin activity, and organic acid metabolism to enhance cucumber resistance to alkaline stress.

1. Introduction

Crops are frequently exposed to various abiotic stresses, which not only reduce yield but also cause major economic losses. Among these stresses, salt–alkali stress is regarded as one of the most detrimental factors limiting global crop productivity. This type of stress is generally divided into two categories: alkaline and neutral salt stress [1,2]. Reports indicate that salt–alkali conditions affect more than 800 million hectares of land worldwide, accounting for about 60% of arable farmland, and approximately 434 million hectares of these soils are characterized by strong alkalinity [3,4]. Plant growth is seriously affected under salt–alkali conditions because of disrupted osmotic balance, ionic toxicity, and the excessive generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which together lead to oxidative damage [3,4]. Under such conditions, the accumulation of sodium ions (Na+) in the rhizosphere often results in potassium (K+) deficiency and severe nutrient imbalance [5]. Alkaline stress, caused mainly by sodium carbonate (Na2CO3) and sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3), is usually more harmful than neutral salt stress, which is mainly associated with sodium chloride (NaCl) and sodium sulfate (Na2SO4). This difference in severity is largely due to the high pH of alkaline stress, which causes the precipitation of essential ions such as magnesium (Mg2+) and phosphate (H2PO4−), further aggravating ionic disequilibrium, metabolic disturbance, and oxidative injury [6,7]. In recent years, researchers have paid increasing attention to how plants adapt to alkaline environments, especially in relation to signal transduction and redox regulation mechanisms [4,8,9]. However, the physiological and molecular bases of plant tolerance to alkaline stress remain unclear, and more detailed studies are still needed to explain how plants coordinate these adaptive responses.

Nitric oxide (NO), a volatile signaling molecule with high diffusivity and nonpolar characteristics, is an important endogenous regulator in plants [10]. It participates in a wide range of physiological and biochemical processes, including seed germination, flowering, ion homeostasis, and stress signaling [11]. NO also functions as a key messenger in redox regulation by promoting the removal of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [6]. Exogenous application of NO has been shown to improve plant stress tolerance by enhancing antioxidant capacity and activating defense responses under adverse environmental conditions [12].

Brassinosteroids (BRs) are naturally occurring plant steroid hormones containing multiple hydroxyl groups. They play essential roles in plant growth and development, regulating photomorphogenesis, cell elongation, and hormone synthesis [13,14]. Beyond developmental regulation, BRs markedly improve plant tolerance to a variety of environmental stresses, including drought, salinity, extreme temperatures, and heavy metal toxicity, as well as biotic stresses such as pathogen attack [13,14]. Previous studies have demonstrated that BRs modulate gene expression by influencing both structural genes and transcriptional regulators, thereby enhancing the plant’s capacity to adapt to stress [14]. BRs also activate antioxidant defense systems by stimulating enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and ascorbate peroxidase (APX), which are essential for maintaining cellular redox homeostasis during stress [15,16]. Furthermore, studies have elucidated the BR signaling cascade, which begins at the membrane receptor level and proceeds through cytoplasmic kinases to nuclear transcription factors [17,18,19]. Through these regulatory networks, BRs promote balanced metabolism and improve crop productivity by reinforcing stress adaptation and optimizing growth-related processes [15,16,19].

Cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) is an agronomically important vegetable crop cultivated worldwide, yet it is highly sensitive to sodic alkaline stress [20,21]. Previous studies from our group demonstrated that exogenous application of either 24-epibrassinolide (EBR, a highly active BR analog) or NO enhances plant tolerance to alkaline stress [22,23]. However, the potential interaction between BRs and NO in regulating cucumber responses to alkaline stress has not been fully elucidated. In this study, we investigated how EBR and NO interact to modulate cucumber seedling responses under NaHCO3-induced alkaline conditions. Our results showed that the stress-alleviating effect of EBR was markedly reduced when NO generation was inhibited by specific scavengers or biosynthesis inhibitors, whereas the protective effect of NO application remained unchanged when BR biosynthesis was disrupted. These observations strongly suggest that NO functions downstream of BR signaling. Overall, this study provides evidence that NO acts as a downstream mediator in BR-regulated tolerance to alkaline stress, thereby enhancing antioxidant defense, maintaining ion balance, improving osmotic stability, and contributing to rhizospheric pH regulation.

2. Results

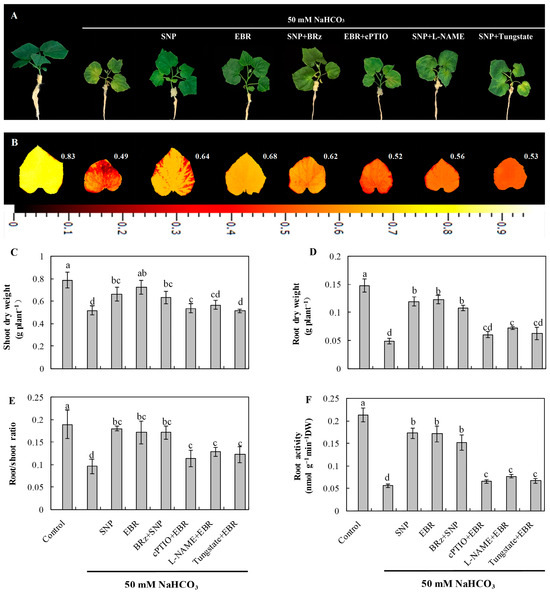

2.1. Exogenous EBR and NO Enhanced Cucumber Tolerance to NaHCO3 Stress

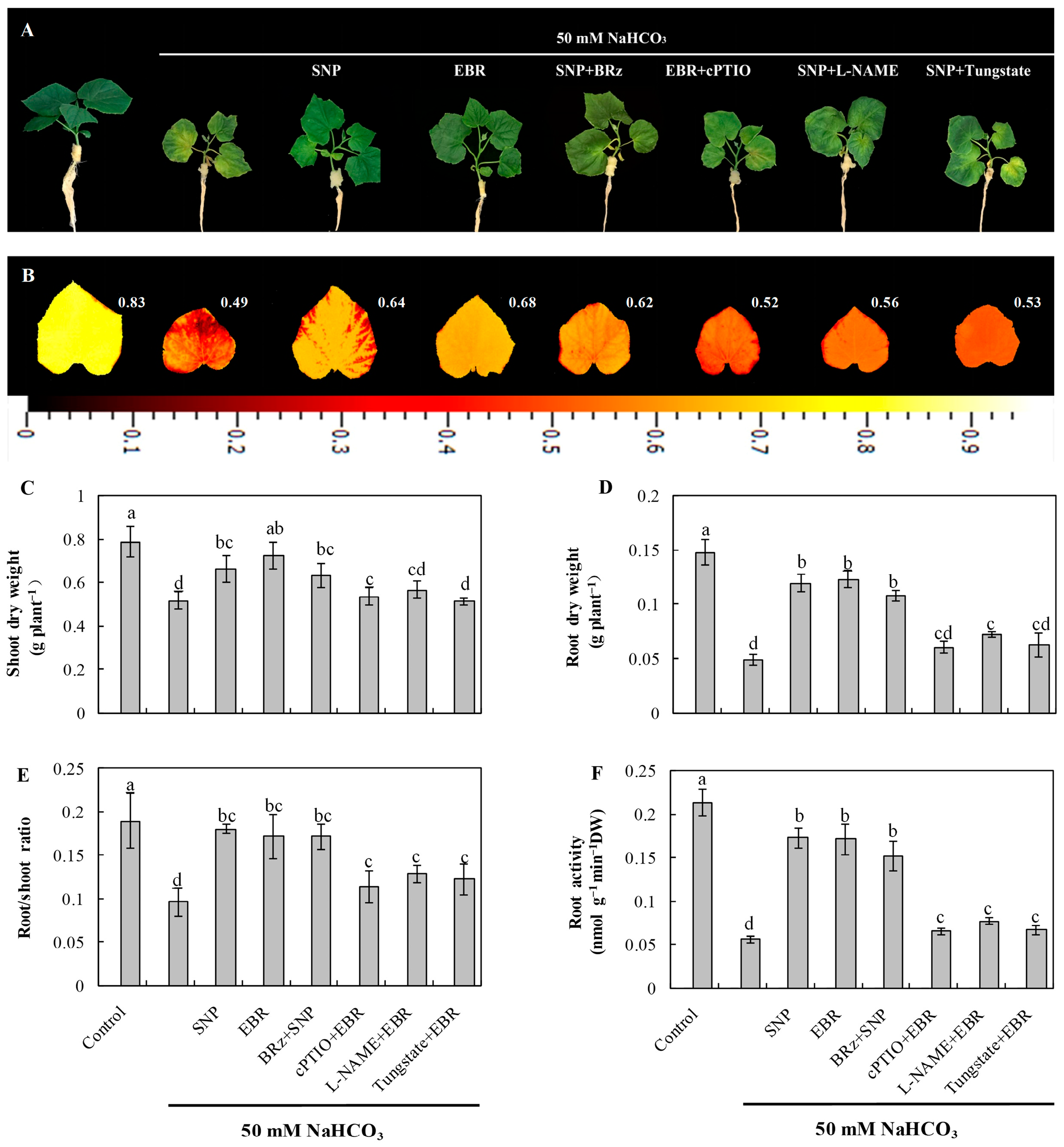

As shown in Figure 1A, NaHCO3 stress caused pronounced chlorosis and wilting of cucumber seedling leaves and significantly reduced the accumulation of shoot and root dry weight (Figure 1C,D). In addition, NaHCO3 stress decreased the maximum quantum efficiency of photosystem II (Fv/Fm) (Figure 1B), the root-to-shoot ratio (Figure 1E), and root activity (Figure 1F). Exogenous application of EBR or the NO donor sodium nitroprusside (SNP) effectively alleviated the damage induced by NaHCO3 stress. Both treatments enhanced shoot and root dry weight accumulation, root-to-shoot ratio, and root activity under stress conditions. Furthermore, the protective effect of SNP was significantly inhibited by the NO scavenger 2-(4-carboxyphenyl)-4,4,5,5-tetramethylimidazoline-1-oxyl-3-oxide (cPTIO), the nitrate reductase (NR) inhibitor tungstate [Na2WO4·2H2O], and the NO synthase (NOS) inhibitor Nω-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME), whereas the BR biosynthesis inhibitor brassinazole (BRz) had little effect on the protective role of SNP. These results indicate that NO may act as a downstream signaling molecule in BR-mediated regulation of alkaline tolerance in cucumber seedlings, thereby mitigating the inhibitory effects of alkaline stress on plant growth.

Figure 1.

Effects of EBR and NO on the growth of cucumber seedlings under NaHCO3 stress. (A) Phenotypic appearance of seedlings after 8 days of exposure; (B) chlorophyll fluorescence images showing the maximum quantum efficiency of photosystem II (Fv/Fm); (C) shoot dry weight; (D) root dry weight; (E) root-to-shoot ratio; (F) root activity. Different lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences among treatments at the 0.05 level (p < 0.05, n = 3). Note that changes to the position of figures and tables may occur during the final steps.

2.2. EBR and NO Maintain Photosynthetic Efficiency Under NaHCO3 Stress

As shown in Table 1, NaHCO3 stress caused a pronounced decline in Pn and pigment contents (Chl a, Chl b, and Car), accompanied by a reduction in Fv/Fm (Figure 1B), reflecting the inhibition of photosystem II (PSII) photochemical activity. In contrast, EBR and NO treatments significantly improved photosynthetic parameters under NaHCO3 exposure, indicating a restoration of PSII efficiency and chlorophyll stability. Moreover, the BR-induced increase in photosynthetic efficiency was strongly suppressed by cPTIO, tungstate, and L-NAME, confirming the involvement of NO in BR-mediated photoprotection. Conversely, BRz had little effect on the NO-induced improvement in photosynthesis, reinforcing the hypothesis that NO acts as a downstream signaling molecule in BR-mediated regulation under alkaline stress.

Table 1.

Effects of exogenous EBR and NO on photosynthetic parameters of cucumber seedlings under NaHCO3 stress.

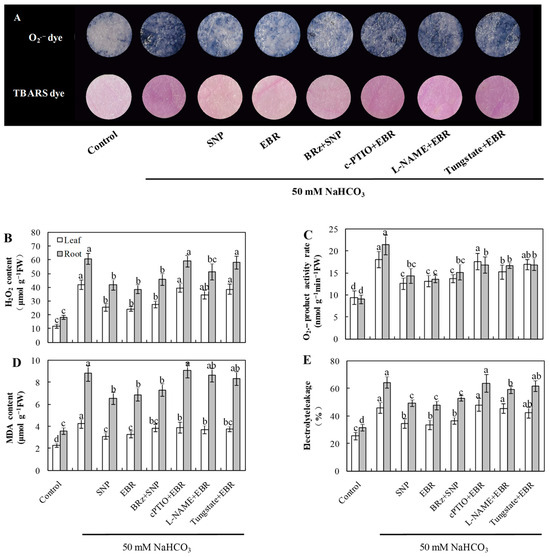

2.3. EBR and NO Reduce ROS Accumulation and Lipid Peroxidation Under NaHCO3 Stress

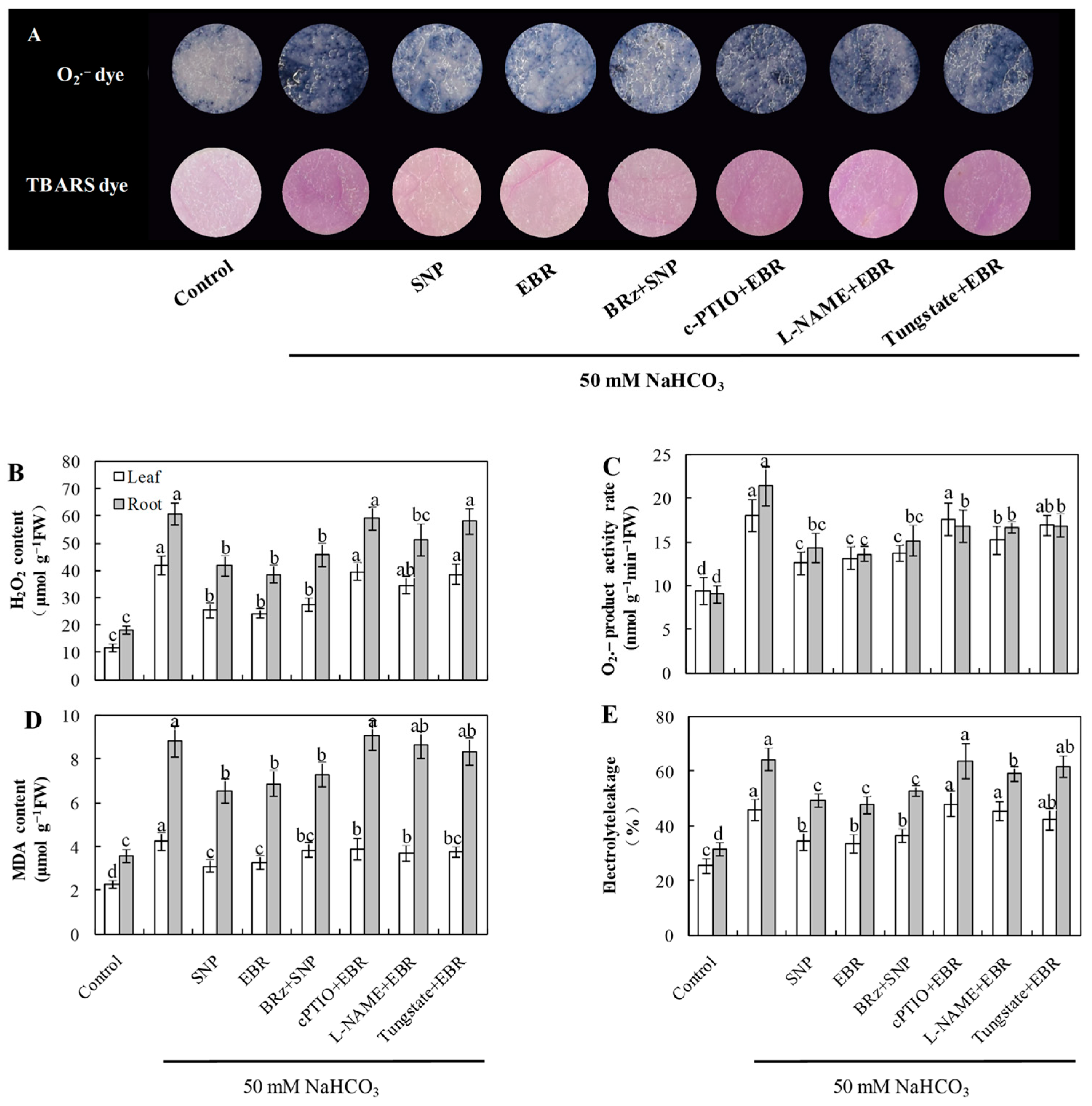

As shown in Figure 2, NaHCO3 exposure led to a marked rise in the levels of O2−, H2O2, and MDA, accompanied by increased electrolyte leakage in both roots and leaves. The addition of EBR and NO markedly reduced ROS and MDA accumulation and decreased EL compared with NaHCO3 treatment alone. Notably, the EBR-induced reductions in O2− and H2O2 levels were largely reversed or markedly weakened by cPTIO, L-NAME, or tungstate, whereas BRz treatment had minimal influence on the NO-mediated decreases in O2− and H2O2 concentrations under NaHCO3 stress. Histochemical staining of ROS and TBARS in cucumber leaves further corroborated these biochemical results (Figure 2A). These observations support the possibility that NO acts as a downstream component in BR-dependent regulation of ROS detoxification in cucumber seedlings under alkaline stress.

Figure 2.

Effects of exogenous EBR and NO on oxidative stress in cucumber seedlings under NaHCO3 stress. (A) Histochemical staining showing superoxide anion (O2−) by NBT and lipid peroxidation by TBARS in cucumber leaves; (B) hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) content; (C) superoxide anion (O2−) production rate; (D) malondialdehyde (MDA) content; (E) electrolyte leakage (EL). Different lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences among treatments at the 0.05 level (p < 0.05, n = 3).

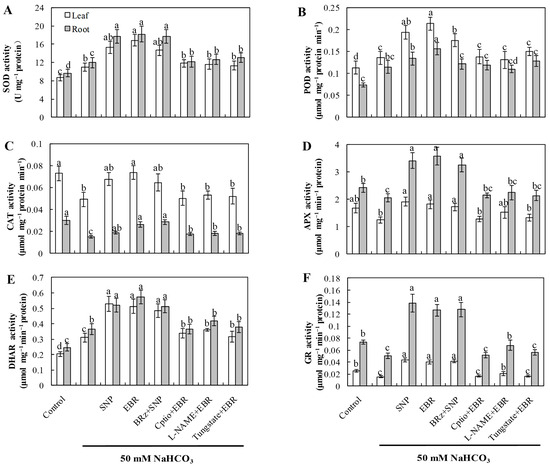

2.4. EBR and NO Increase the Activities of Antioxidant Enzymes Under NaHCO3 Stress

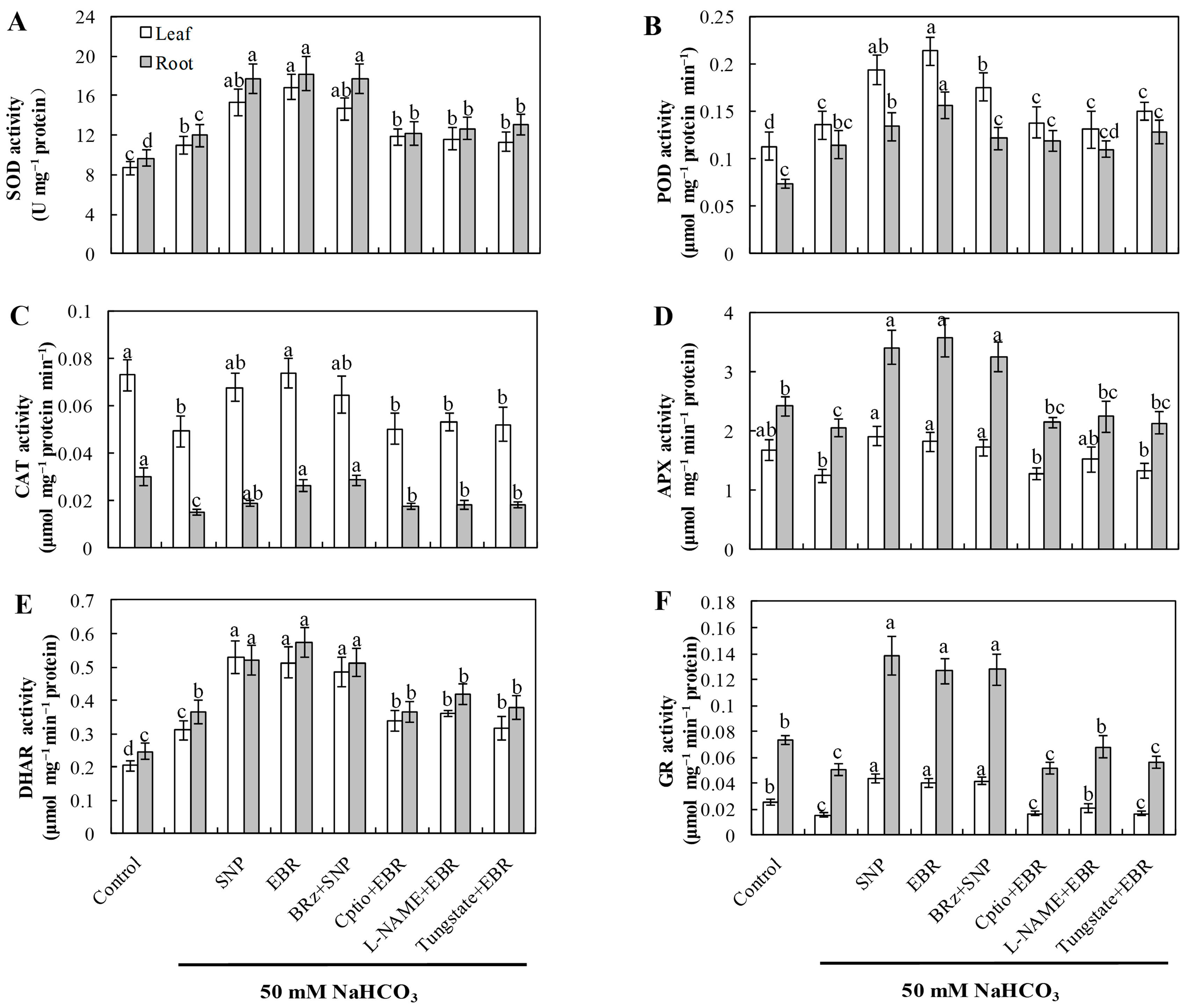

Compared with the control, NaHCO3 stress markedly enhanced the activities of SOD, POD, and DHAR, whereas the activities of CAT, APX, and GR significantly declined (Figure 3). This pattern indicates that although the antioxidant system was activated as a compensatory response, the imbalance among individual enzymes impaired the overall redox equilibrium in cucumber seedlings. Treatment with exogenous EBR or NO notably elevated the activities of all six enzymes, thereby enhancing antioxidant defense capacity and mitigating oxidative damage induced by NaHCO3 stress. Furthermore, the EBR-induced enhancement of antioxidant enzyme activities was markedly suppressed by cPTIO, L-NAME, and tungstate, confirming that NO synthesis is required for the BR-mediated antioxidant response. In contrast, the NO-induced enzyme activation was not significantly affected by BRz treatment. These findings collectively demonstrate that EBR enhances the antioxidant enzyme system primarily through an NO-dependent signaling cascade, contributing to improved oxidative stress tolerance under alkaline conditions.

Figure 3.

Effects of exogenous EBR and NO on antioxidant enzyme activities in cucumber seedlings under NaHCO3 stress. (A) Superoxide dismutase (SOD); (B) Peroxidase (POD); (C) Catalase (CAT); (D) Ascorbate peroxidase (APX); (E) Dehydroascorbate reductase (DHAR); (F) Glutathione reductase (GR). Different lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences among treatments at the 0.05 level (p < 0.05, n = 3).

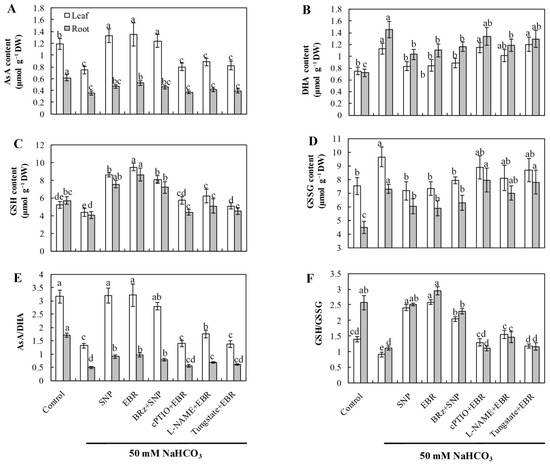

2.5. EBR and NO Improve the AsA–GSH Cycle Under NaHCO3 Stress

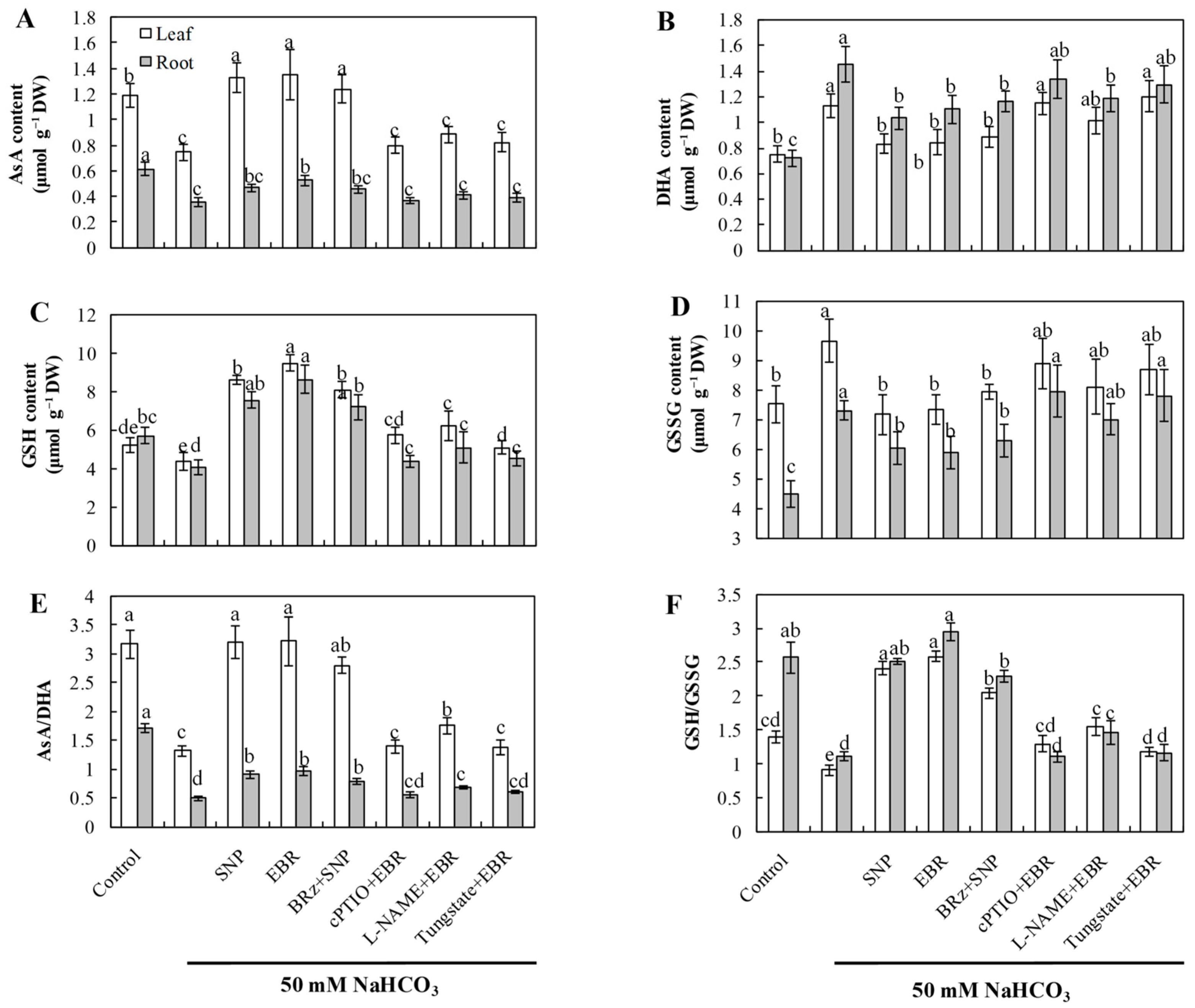

NaHCO3 stress markedly decreased the concentrations of AsA and GSH, along with a significant reduction in the AsA/DHA and GSH/GSSG ratios, indicating a disrupted redox state in the AsA–GSH cycle (Figure 4). Exogenous application of EBR and NO substantially increased AsA and GSH levels and improved both AsA/DHA and GSH/GSSG ratios, thereby restoring cellular redox homeostasis and enhancing antioxidant buffering capacity under alkaline conditions. Importantly, the beneficial effects induced by EBR were largely abolished by treatments with cPTIO, L-NAME, and tungstate, while BRz had minimal effect on the NO-mediated improvements. These results suggest that EBR enhances the AsA–GSH cycle predominantly through NO-dependent signaling, thereby maintaining redox equilibrium during NaHCO3 stress.

Figure 4.

Effects of exogenous EBR and NO on the contents of non-enzymatic antioxidants in cucumber seedlings under NaHCO3 stress. (A) Ascorbic acid (AsA); (B) Dehydroascorbic acid (DHA); (C) Reduced glutathione (GSH); (D) Oxidized glutathione (GSSG); (E) AsA/DHA ratio; (F) GSH/GSSG ratio. Different lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences among treatments at the 0.05 level (p < 0.05, n = 3).

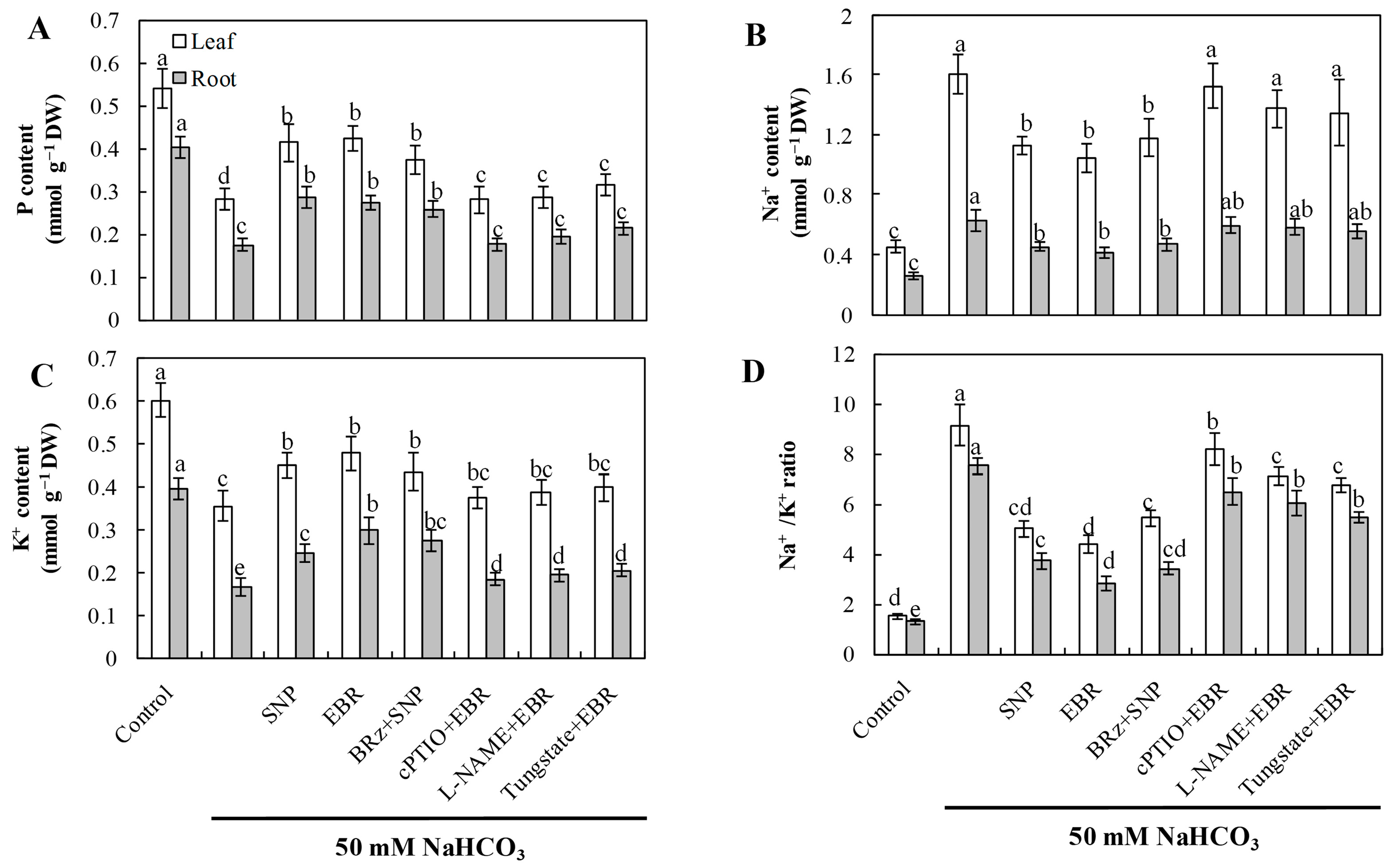

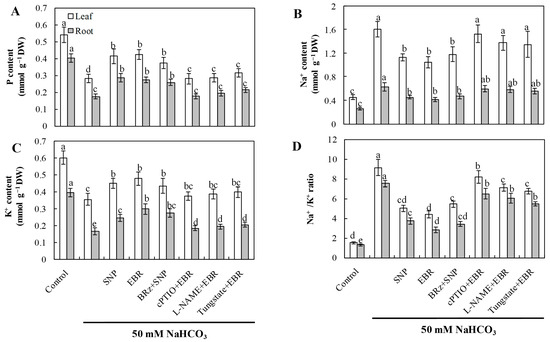

2.6. EBR and NO Improve Ion Homeostasis Under NaHCO3 Stress

NaHCO3 stress caused substantial Na+ accumulation and significantly reduced K+ and P contents, resulting in a markedly elevated Na+/K+ ratio (Figure 5). Exogenous application of EBR and NO effectively reduced Na+ accumulation, promoted K+ uptake, and increased P levels, thus maintaining ion homeostasis in both leaves and roots. The EBR-induced restoration of ion homeostasis was strongly inhibited by cPTIO, L-NAME, and tungstate, whereas BRz exhibited little effect on the NO-mediated regulation. These observations indicate that NO functions as a downstream signaling molecule of EBR to regulate Na+ and K+ transport, contributing to improved ion homeostasis under alkaline stress.

Figure 5.

Effects of exogenous EBR and NO on ion homeostasis in cucumber seedlings exposed to NaHCO3 stress. (A) Phosphorus (P); (B) sodium (Na+); (C) potassium (K+); (D) Na+/K+ ratio in leaves and roots. Different lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences among treatments at the 0.05 level (p < 0.05, n = 3).

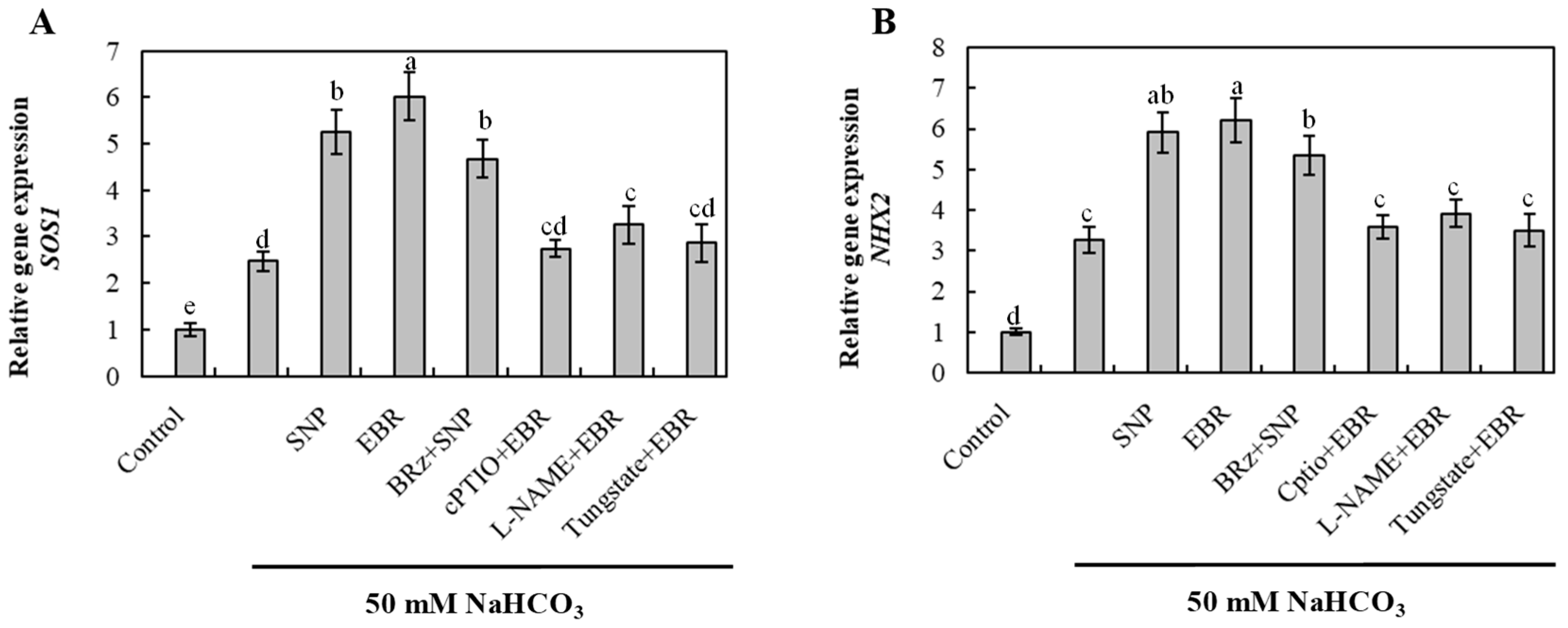

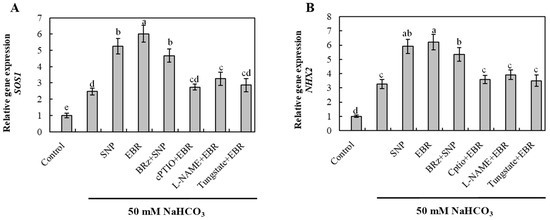

2.7. EBR and NO Upregulate Na+ Detoxification-Related Genes Under NaHCO3 Stress

To elucidate the molecular mechanism involved in Na+ detoxification, the transcript levels of SOS1 (plasma membrane Na+/H+ antiporter) and NHX2 (vacuolar Na+/H+ exchanger) were quantified (Figure 6). NaHCO3 stress significantly upregulated the expression of both genes, suggesting activation of Na+ extrusion and vacuolar compartmentalization processes. EBR and NO treatments further enhanced SOS1 and NHX2 expression, whereas the EBR-induced upregulation was strongly inhibited by cPTIO, L-NAME, and tungstate. Conversely, BRz had a negligible effect on the NO-mediated response. These results indicate that EBR activates Na+ detoxification-related genes primarily through an NO-dependent signaling pathway, thereby effectively strengthening Na+ efflux and vacuolar sequestration in cucumber roots.

Figure 6.

Effects of exogenous EBR and NO on the expression of Na+ detoxification-related genes in cucumber roots under NaHCO3 stress. (A) Salt overly sensitive 1 (SOS1); (B) Na+/H+ exchanger 2 (NHX2). Different lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences among treatments at the 0.05 level (p < 0.05, n = 3).

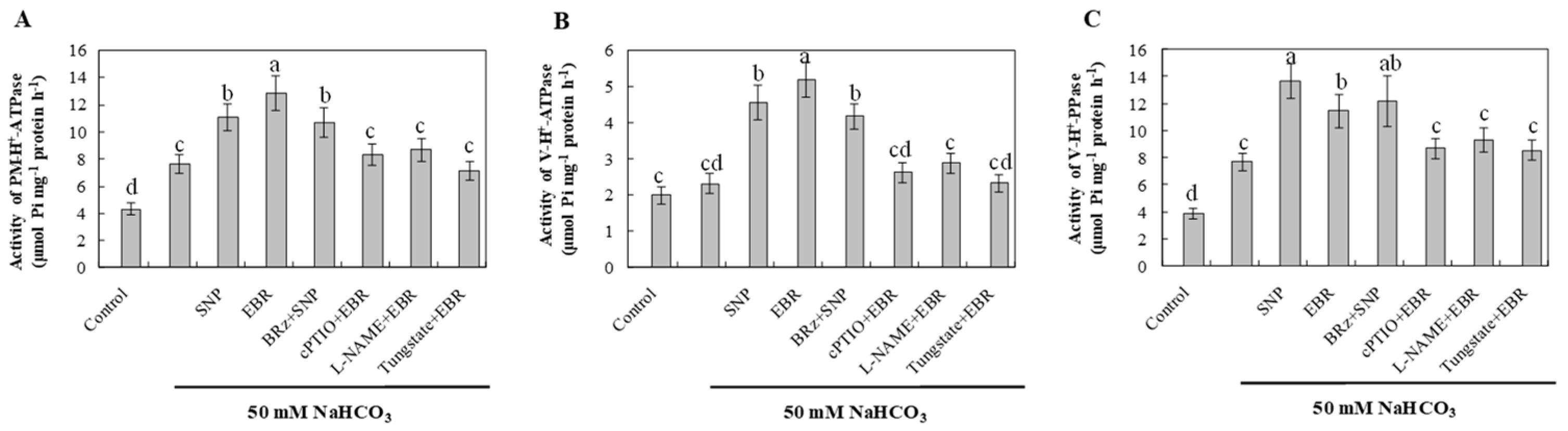

2.8. EBR and NO Enhance H+-Pump Activities Under NaHCO3 Stress

NaHCO3 stress increased the activities of plasma membrane H+-ATPase, tonoplast H+-ATPase, and H+-PPase compared with the control (Figure 7). This enhancement likely reflects an adaptive response that facilitates Na+ extrusion and vacuolar sequestration, helping to maintain ionic balance under alkaline conditions. Treatment with EBR or NO further stimulated the activities of these proton pumps, suggesting that both regulators enhance proton transport and ion compartmentalization in response to NaHCO3 stress. The activation of these enzymes by EBR was markedly suppressed by cPTIO, L-NAME, and tungstate, whereas BRz had a relatively small effect on the NO-mediated enhancement. These results indicate that NO functions as a downstream signaling molecule of EBR. The enhanced proton pump activities induced by either EBR or NO contribute to Na+ efflux, vacuolar compartmentalization, and overall ion homeostasis, thereby improving the alkaline tolerance of cucumber roots.

Figure 7.

Effects of exogenous EBR and NO on proton-pump activities in cucumber roots under NaHCO3 stress. (A) Plasma membrane H+-ATPase (PM H+-ATPase) activity; (B) Tonoplast (vacuolar) H+-ATPase (V-ATPase) activity; (C) Tonoplast H+-pyrophosphatase (H+-PPase) activity. Different lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences among treatments at the 0.05 level (p < 0.05, n = 3).

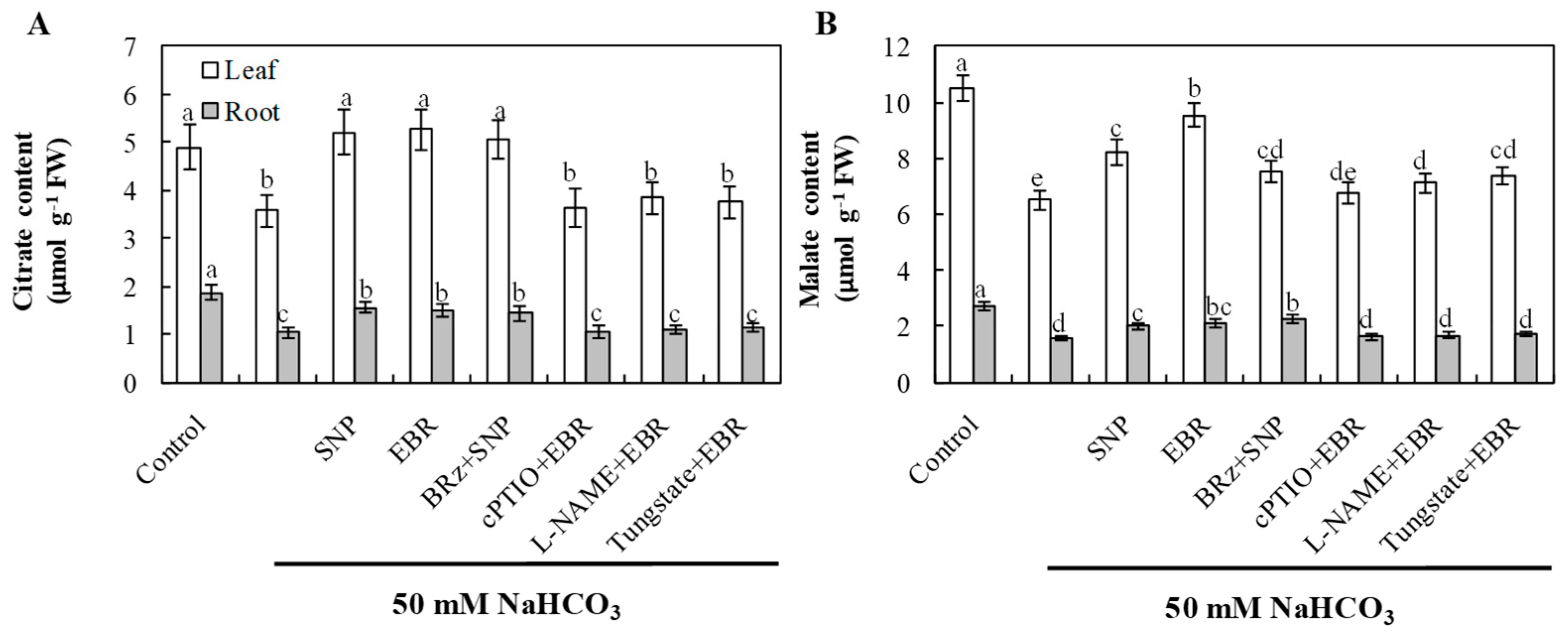

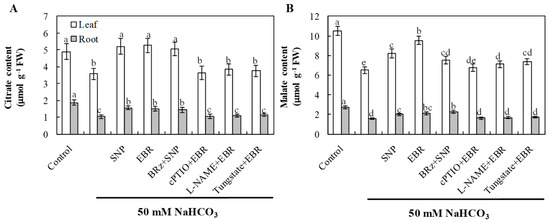

2.9. EBR and NO Promote Organic Acid Accumulation Under NaHCO3 Stress

The elevated contents of citrate and malate may play important roles in buffering cytoplasmic pH and chelating excess Na+, thereby alleviating high-pH stress and maintaining ion homeostasis. NaHCO3 stress significantly decreased the levels of citrate and malate in both leaves and roots, indicating inhibition of organic acid metabolism under alkaline conditions (Figure 8). Application of EBR or NO markedly increased the accumulation of these organic acids compared with NaHCO3 treatment alone. The EBR-induced enhancement of organic acid accumulation was markedly suppressed by cPTIO, L-NAME, and tungstate, whereas BRz had only a slight effect on the NO-induced increases in citrate. Although BRz also reduced the NO-induced accumulation of malate, the extent of reduction was relatively small. These findings suggest that exogenous BR regulates organic acid accumulation under alkaline stress through both NR- and NOS-dependent pathways, but NO does not act entirely as a downstream signal of BR in this regulatory process.

Figure 8.

Effects of exogenous EBR and NO on organic acid accumulation in cucumber seedlings under NaHCO3 stress. (A) Citrate; (B) malate in roots and leaves. Different lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences among treatments at the 0.05 level (p < 0.05, n = 3).

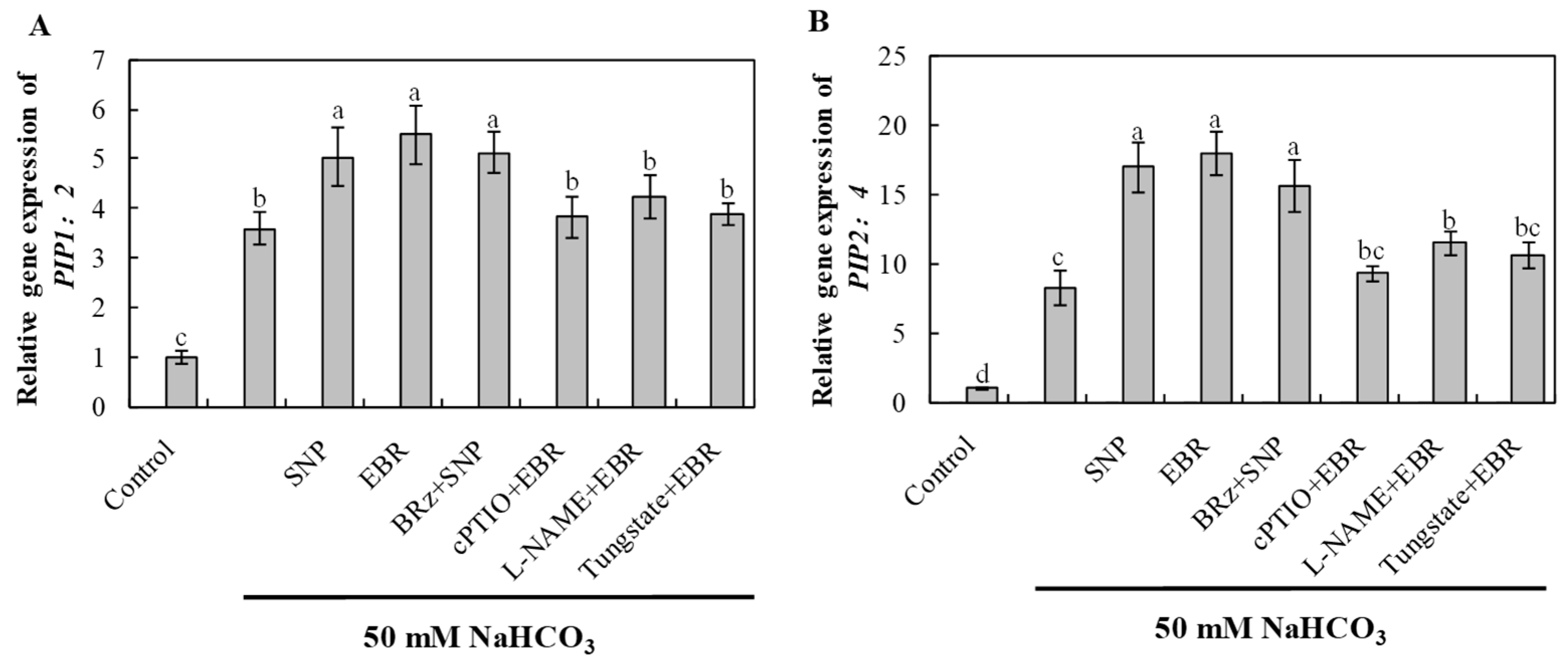

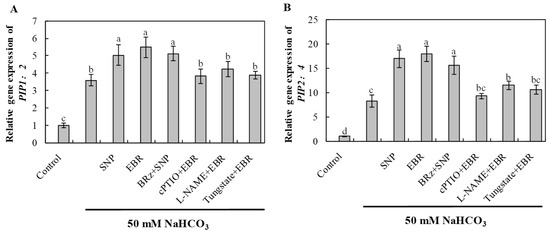

2.10. EBR and NO Enhance Aquaporin Gene Expression Under NaHCO3 Stress

NaHCO3 stress significantly induced the expression of aquaporin genes PIP1;2 and PIP2;4, indicating an adaptive response to maintain water balance under alkaline stress (Figure 9). EBR and NO treatments further enhanced the transcript levels of these genes, thereby facilitating water transport and root hydraulic conductivity. The EBR-induced upregulation was notably inhibited by cPTIO, L-NAME, and tungstate, whereas BRz treatment had little effect on the NO-mediated increase. These results demonstrate that BR regulates aquaporin-mediated water transport via an NO-dependent pathway, improving plant water status under NaHCO3 stress.

Figure 9.

Effects of exogenous EBR and NO on aquaporin gene expression in cucumber roots under NaHCO3 stress. (A) PIP1;2; (B) PIP2;4 after 16 h of treatment. Different lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences among treatments at the 0.05 level (p < 0.05, n = 3).

3. Discussion

Although NO and BRs are well known to enhance plant tolerance to abiotic stresses [22,24], their interaction under alkaline conditions remains unclear. In this study, NaHCO3 stress caused Na+ toxicity, impaired photosynthesis, and excessive ROS accumulation, leading to growth inhibition in cucumber seedlings. The application of exogenous NO or EBR effectively alleviated these negative effects by sustaining photosynthetic efficiency, maintaining ion homeostasis, enhancing antioxidant defense, and promoting the expression of aquaporin genes. The protective effect of EBR was markedly suppressed when NO biosynthesis or activity was inhibited by cPTIO, tungstate, or L-NAME, whereas BRz had little influence on NO-mediated protection, indicating that NO acts downstream of BR signaling in regulating alkaline tolerance. These findings extend previous reports on BR and NO cooperation under abiotic stress and reveal a coordinated BR–NO signaling pathway that confers tolerance to NaHCO3-induced alkaline stress.

Under saline–alkali stress, Na+ concentrations in the rhizosphere are markedly elevated. Maintaining a low Na+ concentration in the cytosol is essential for sustaining normal metabolic processes such as photosynthesis and ROS scavenging [25,26]. Due to their similar hydration and atomic radii, Na+ competitively inhibits K+ uptake through cation channels [27], resulting in Na+ accumulation, K+ deficiency, and a substantially increased Na+/K+ ratio in cucumber plants (Figure 5). Because plants lack a Na+-ATPase, Na+ efflux occurs exclusively via the salt overly sensitive (SOS) signaling cascade, which is crucial for plant adaptation to salt stress [28]. The SOS network consists of SOS1, SOS2, and SOS3, together with NHX transporters [29]. SOS1, localized at the plasma membrane, acts as a Na+/H+ exchanger that senses Na+ signals and exports excess cytosolic Na+ [30]. Salt stress strongly induces SOS1 expression; overexpression enhances salt tolerance, whereas knockout mutants display hypersensitivity [31]. In parallel, NHX proteins on the vacuolar membrane mediate Na+ compartmentalization into vacuoles [32]. Specifically, NHX reduces cytosolic Na+ accumulation by sequestering Na+ into the vacuole [33,34]. NHX proteins also contribute to pH homeostasis, as Arabidopsis nhx mutants exhibit elevated vacuolar pH compared with wild type [35]. Therefore, Na+/H+ counter-transport plays an essential role in maintaining Na+ efflux and vacuolar sequestration during salt and alkaline stress [36]. Because Na+/H+ exchange is an energy-dependent process, it relies on the activity of proton pumps, including plasma membrane H+-ATPase, vacuolar H+-ATPase, and vacuolar H+-PPase [37].

Previous studies have reported that both NO and BR can activate these proton pumps, thereby supplying the energy required for SOS1- and NHX-mediated Na+ transport under saline stress [24,37,38,39,40]. Consistent with these findings, our results (Figure 7) showed that BR and NO treatments markedly increased the activities of PM H+-ATPase, V-ATPase, and H+-PPase in cucumber roots under NaHCO3 stress. This enhancement promoted Na+ extrusion via SOS1 and vacuolar sequestration through NHX2, stabilizing the Na+/K+ ratio and improving ion homeostasis. Furthermore, the BR-induced stimulation of proton pumps was strongly suppressed by cPTIO, L-NAME, and tungstate, whereas BRz had only a minor influence on NO-mediated responses. These results, together with the upregulated expression of SOS1 and NHX2 (Figure 6), indicate that NO functions downstream of BR signaling to regulate the SOS pathway and Na+ detoxification. However, our findings extend this regulatory mechanism to NaHCO3-induced alkaline stress, suggesting that the BR–NO interaction contributes to maintaining ion balance and enhancing tolerance in cucumber seedlings.

Declines in photosynthetic pigment content and suppression of the Pn under alkaline stress largely explain the restriction of plant growth and biomass accumulation. Alkaline–salinity stress disrupts chloroplast ultrastructure, accelerates chlorophyll degradation, and inhibits carbon assimilation, resulting in decreased photosynthetic capacity and impaired growth [9,23,41]. In addition, stress-induced inhibition of respiration and photosynthesis leads to electron leakage, ROS overproduction, and lipid peroxidation, ultimately damaging the photosynthetic apparatus. Similar chloroplast disorganization and oxidative injury have been reported in Solanum lycopersicum and Apocynum venetum L. (Apocynaceae) subjected to alkaline stress [4,41], supporting the view that oxidative impairment of photosynthetic structures is a primary cause of growth inhibition. It is well established that both NO and EBR play critical roles in regulating plant adaptation to abiotic stress. The beneficial influence of these compounds on cucumber biomass during NaHCO3 exposure can be attributed to their ability to maintain photosynthetic efficiency. Previous studies have demonstrated that exogenous NO mitigates chlorosis under alkaline stress [4,10,34], while BRs enhance photosynthetic performance under salt stress [24]. Consistent with these findings, our results showed that NaHCO3 stress significantly reduced chlorophyll content and Pn (Table 2), leading to decreased biomass accumulation (Figure 1), whereas exogenous BR and NO alleviated these effects and improved leaf greenness and photosynthetic rates.

Table 2.

Primers sequences.

Chlorophyll fluorescence is a sensitive indicator of PSII function and has been widely used to assess chloroplast integrity and stability [42,43]. The decline in Fv/Fm values observed under NaHCO3 stress (Figure 1B) indicates photoinhibition and reduced PSII efficiency, likely resulting from restricted electron transport between primary (Qa) and secondary (Qβ) quinone acceptors [34,44]. In contrast, exogenous BR and NO significantly increased Fv/Fm, suggesting protection of PSII reaction centers. Similar improvements in photochemical efficiency by NO or BR treatment have been observed in Solanum lycopersicum, Cyclocarya paliurus, Abelmoschus esculentus L. and Maize under salt and alkaline stress [34,38,45,46]. Moreover, the BR-induced enhancement in Fv/Fm was abolished by cPTIO and markedly reduced by L-NAME and tungstate, while BRz had little effect on NO-mediated protection. These findings indicate that NO acts downstream of BR signaling to preserve photosynthetic machinery under alkaline stress.

Salt and alkaline stress also impose osmotic limitations that disturb water balance in cucumber plants. Such effects arise from reduced extracellular water potential, which limits water uptake, and from impaired aquaporin activity, which restricts transmembrane water transport [47,48]. Aquaporins are key regulators of water permeability and osmotic adjustment, and their activity accounts for 70–90% of root hydraulic conductance [49]. In this study, exogenous BR and NO upregulated the transcription of aquaporin genes (Figure 9), particularly PIP1;2 and PIP2;4, thereby improving root water absorption and translocation under NaHCO3 stress. These genes were significantly induced 16 h after treatment, and their expression was further enhanced by BR or NO application. However, the BR-induced increase was strongly suppressed by cPTIO, tungstate, and L-NAME, whereas BRz had minimal influence on NO-mediated induction. Collectively, these findings suggest that BR modulates aquaporin expression through an NO-dependent pathway, facilitating water transport and contributing to improved stress tolerance.

Salinity stress disrupts photosynthesis and respiration, leading to impaired electron transport and excessive accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [50]. At moderate levels, ROS act as signaling molecules that trigger plant defense pathways [51]; however, when produced excessively, they oxidize lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids, resulting in structural and functional damage. Thus, oxidative stress represents one of the most prominent manifestations of plant injury under saline–alkali conditions [52,53]. Previous studies have demonstrated that EBR can upregulate antioxidant-related genes and enhance enzymatic activity, thereby improving stress resistance [54,55]. In this study, NaHCO3 stress caused a sharp increase in ROS levels, elevated MDA content, and led to pronounced lipid peroxidation of plasma membranes (Figure 2). Exogenous EBR and NO treatments significantly reduced ROS accumulation and MDA levels, thereby alleviating membrane injury. In parallel, the activities of major antioxidant enzymes, including SOD, POD, and CAT, were enhanced in both roots and leaves during stress exposure. Enzymes related to the AsA–GSH cycle, such as APX, GR, and DHAR, also showed increased activities (Figure 3), accompanied by higher AsA and GSH contents (Figure 4). As a result, the NaHCO3-induced accumulation of DHA and GSSG was mitigated, leading to improved AsA/DHA and GSH/GSSG ratios and a more balanced redox state. These changes maintained efficient operation of the AsA–GSH cycle and enhanced the overall ROS-scavenging capacity of cucumber seedlings.

The responses observed align with previous reports showing that EBR enhances antioxidant metabolism under abiotic stress [22,53]. In our study, the EBR-induced activation of the antioxidant system was clearly dependent on endogenous NO. When NO biosynthesis or signaling was blocked by cPTIO, tungstate, or L-NAME, the protective effects of EBR on enzyme activities and non-enzymatic antioxidants were markedly weakened. In contrast, the BR biosynthesis inhibitor BRz had little influence on the NO-induced antioxidant response (Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4), indicating that NO acts downstream of EBR rather than as a parallel regulator. Previous research has shown that NO can modulate antioxidant enzymes [4,19,23], while BRs promote ROS detoxification by stimulating NO generation and enhancing the AsA–GSH recycling system [38,54]. Together with our results, these findings suggest that EBR enhances antioxidant capacity through an NO-dependent signaling pathway, which helps to mitigate oxidative damage and maintain redox homeostasis under NaHCO3 stress.

The accumulation of organic acids represents an important adaptive strategy for plants under adverse environmental conditions. In saline–alkali environments, organic acids act as intracellular pH buffers that counteract the effects of high alkalinity, thereby protecting metabolic activity and maintaining ion balance [56,57]. Among these, citric acid and malic acid are the predominant organic acids in cucurbit crops, functioning both as pH regulators and as intermediates in the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle [58,59]. In our study, NaHCO3 stress led to a marked decline in the contents of citrate and malate (Figure 8), while the application of exogenous EBR or NO significantly increased their accumulation, alleviating high pH–induced damage. Enhanced organic acid biosynthesis under these treatments likely helped to stabilize cellular pH and facilitate ion homeostasis. Similar results have been reported in cotton and rice, where exogenous hormones or signaling molecules promoted organic acid metabolism to enhance tolerance to alkaline stress [60,61]. The promotive effect of EBR on citrate and malate accumulation was largely inhibited by cPTIO, tungstate, and L-NAME, whereas BRz had little influence on the NO-induced response (Figure 8). These results indicate that the regulation of organic acid metabolism by EBR is mediated through NO-dependent signaling rather than direct stimulation. This conclusion is consistent with the observed downstream role of NO in EBR-induced ion and redox regulation. Together, these findings suggest that EBR enhances alkaline tolerance in cucumber by activating NO signaling to stimulate organic acid synthesis and pH-buffering capacity, thereby maintaining metabolic stability under NaHCO3 stress.

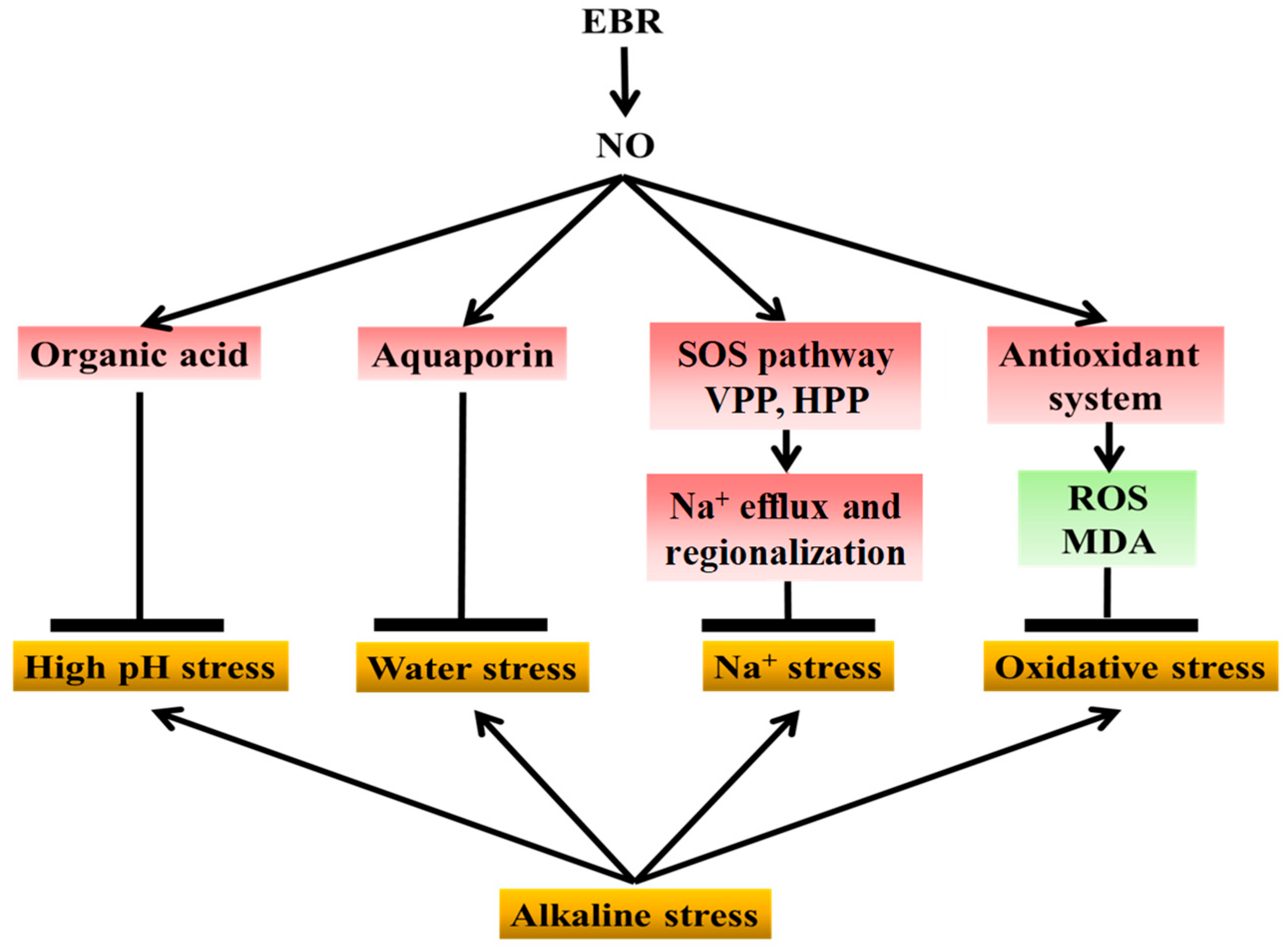

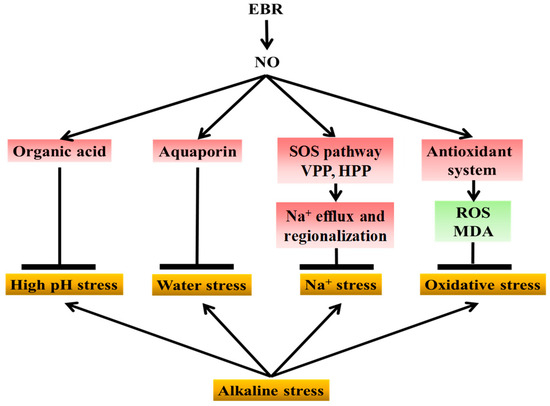

Collectively, and as illustrated in Figure 10, these findings demonstrate that exogenous EBR enhances the tolerance of cucumber seedlings to NaHCO3-induced alkaline stress through NO-dependent signaling. NaHCO3 stress causes Na+ toxicity, oxidative imbalance, water stress, and high-pH-induced metabolic inhibition. As a downstream signal, NO transmits EBR regulation to multiple defense pathways, including antioxidant protection, ion homeostasis, aquaporin activity, and organic acid metabolism, thereby alleviating oxidative damage, ionic imbalance, water stress, and high-pH injury. This coordination maintains cellular stability and higher photosynthetic efficiency, ultimately supporting plant growth under alkaline conditions. Overall, NO acts as a central mediator linking BR perception to physiological and metabolic adjustments that collectively reduce alkaline-induced injury in cucumber. This work elucidates the signaling pathway by which EBR mitigates saline-alkali stress and further clarifies the mechanistic relationship between EBR and NO under abiotic stress.

Figure 10.

Proposed model of NO-mediated EBR regulation of cucumber tolerance to alkaline stress. NaHCO3 stress induces sodium toxicity, oxidative imbalance, high-pH stress, and water stress, thereby inhibiting cucumber growth. Exogenous EBR enhances stress tolerance by relying on NO as a downstream signaling molecule to coordinate multiple defense pathways. EBR-induced NO signaling promotes organic acid accumulation to buffer cellular pH and alleviate high-pH stress; enhances aquaporin expression to relieve water stress; activates the SOS pathway together with H+-ATPase and H+-PPase activities to facilitate sodium efflux and vacuolar compartmentalization; and stimulates the antioxidant system, including antioxidant enzymes and the ascorbate–glutathione cycle, to reduce reactive oxygen species accumulation and oxidative damage. These coordinated effects collectively mitigate growth inhibition in cucumber seedlings exposed to sodium bicarbonate stress (The yellow boxes represent the types of physiological damage caused by alkaline stress; the red boxes indicate factors upregulated by exogenous NO and EBR; and the green boxes indicate factors downregulated by NO and EBR).

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Growth Conditions and Treatment Setup

Seeds of cucumber (Cucumis sativus L. cv. Jinyan 4) were first placed on moist filter paper at 28 °C for 24 h to promote germination. The sprouted seeds were then transferred into vermiculite within a growth chamber. Seedlings were maintained under controlled conditions (25 °C/18 °C day/night) with a 14 h light/10 h dark photoperiod for 8 days. The NaHCO3 concentration (50 mM) was determined based on preliminary tests. Once the first true leaf had fully expanded, uniform seedlings were selected and individually transplanted into 0.8 L plastic pots containing Hoagland nutrient solution (one seedling per pot). Following an 8-day acclimatization period, experimental treatments were initiated.

The study included eight treatment groups:

- Control—Hoagland nutrient solution only.

- NaHCO3—Hoagland solution supplemented with 50 mM NaHCO3.

- NaHCO3 + EBR—50 mM NaHCO3 combined with 0.2 μM 24-epibrassinolide (EBR).

- NaHCO3 + SNP—50 mM NaHCO3 plus 100 μM sodium nitroprusside (SNP, an NO donor).

- NaHCO3 + BRz + SNP—50 mM NaHCO3 with 100 μM SNP and 4 μM brassinazole (BRz, a BR biosynthesis inhibitor).

- NaHCO3 + cPTIO + EBR—50 mM NaHCO3 with 0.2 μM EBR and 150 μM cPTIO (2,4-carboxyphenyl-4,4,5,5-tetramethylimidazoline-1-oxyl-3-oxide, a NO scavenger).

- NaHCO3 + L-NAME + EBR—50 mM NaHCO3 with 0.2 μM EBR and 200 μM L-NAME (N-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester, an inhibitor of NO synthase).

- NaHCO3 + Tungstate + EBR—50 mM NaHCO3 with 0.2 μM EBR and 200 μM tungstate (an inhibitor of nitrate reductase).

Each treatment included 20 plants and was organized following a randomized complete block scheme. The nutrient solution was renewed daily and aerated for 20 min each day. qRT-PCR analysis was conducted 16 h post-treatment to assess gene expression, whereas physiological indices were determined after 8 days of exposure.

4.2. Determination of Biomass and Root Activity

Shoots and roots were first separated and rinsed thoroughly with deionized water. For biomass measurement, plant samples were initially heated at 105 °C for 20 min so that exogenous enzymes became inactive. Afterwards, they were kept in an oven at 75 °C for about three consecutive days, until the dry mass reached a constant level. The final dry weight was then recorded. Root activity was determined using the triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) reduction method [4]. In brief, 1 g of freshly collected root tissue was placed into 20 mL of 0.5 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) containing 0.4% (v/v) TTC and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. To stop the reaction, 2 mL of 1 M H2SO4 was added. The triphenyl formazan generated (TPF) was extracted with ethyl acetate, and finally, its absorbance was measured at 485 nm using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer (UV-1800, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) spectrophotometer.

4.3. Determination of Photosynthetic Apparatus

For photosynthetic measurements, the second fully expanded leaf from each cucumber seedling was chosen. The assessment was carried out using a portable photosynthesis system (LI-6400, LI-COR, Lincoln, NE, USA), which was employed under a photon flux density of 800 μmol m−2 s−1 together with an ambient CO2 concentration of about 340 μmol mol−1. Photosynthetic pigments were analyzed after extraction with 95% ethanol. Absorbance of the pigment solutions was then recorded at 663.3, 646.8, and 470 nm with a spectrophotometer, and the data were subsequently used to calculate the concentrations of chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and carotenoids individually [62].

4.4. Determination of Lipid Peroxidation and Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Levels

Malondialdehyde (MDA) was quantified as an indicator of lipid peroxidation following the method of Schmedes and Hølmer [63] with modifications. Briefly, 1 g of fresh leaf tissue was homogenized in 10 mL of 10% (w/v) trichloroacetic acid (TCA) and centrifuged at 4000× g for 10 min. The supernatant (2 mL) was mixed with an equal volume of 0.6% thiobarbituric acid (TBA) solution, incubated in boiling water for 15 min, rapidly cooled, and centrifuged again. The absorbance of the supernatant was recorded at 532, 600, and 450 nm, and MDA concentration was determined using a standard calibration curve.

The generation rate of superoxide anion (O2−) was measured following the protocol of Elstner and Heupel [64]. Approximately 1 g of fresh tissue was ground in 3 mL phosphate buffer (pH 7.8) and centrifuged at 4000× g for 15 min. A 0.5 mL aliquot of the supernatant was combined with 1 mL hydroxylamine hydrochloride and incubated at 25 °C for 1 h. Subsequently, 1 mL of the reaction solution containing 17 mM p-aminobenzene sulfonic acid and 7 mM α-naphthylamine was added and further incubated for 20 min at 25 °C. Absorbance was measured at 530 nm, and the O2− content was calculated using a calibration curve prepared with NaNO2.

Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) content was determined as described by Patterson et al. [65]. Fresh tissue extracts were reacted with the titanium reagent, and the absorbance of the reaction mixture was read at 415 nm. The H2O2 concentration was calculated by comparison with a standard curve prepared from known concentrations of H2O2.

4.5. Histochemical Staining of MDA and O2−

MDA staining: Lipid peroxidation was assessed using Schiff’s reagent as outlined by Jambunathan [66]. In brief, 0.05 g of basic fuchsin was first dissolved in a solution consisting of 0.5 mL concentrated HCl mixed with 50 mL distilled water. After that, 0.5 g sodium sulfite was added while stirring continuously until the red coloration disappeared completely. Leaf tissues were immersed in the freshly prepared reagent and incubated for 1 h. Subsequently, they were treated with 80% ethanol at 90 °C until a red or purple precipitate became visible, which indicated the formation of thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) linked to MDA buildup.

O2− staining: The accumulation of superoxide was examined following the NBT staining approach described by Fryer et al. [67]. Fresh leaves were rinsed thoroughly with distilled water, then transferred into 10 mL centrifuge tubes containing 0.5 mg mL−1 NBT prepared in 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.8). To ensure sufficient infiltration, samples were vacuum-treated and later kept in darkness at room temperature for 1 h, thereby enabling O2−-dependent NBT reduction and the subsequent appearance of blue formazan.

After staining, both MDA and O2−-treated leaves were heated in 90% ethanol at 90 °C until chlorophyll was fully removed. The decolorized leaves were then photographed under identical conditions to evaluate the staining patterns.

4.6. Determination of Antioxidant Enzyme Activities

Fresh cucumber leaves (0.3 g) were homogenized in 3 mL of chilled 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.8) supplemented with 2 mM ascorbic acid, 0.2 mM EDTA, and 2% polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP). The homogenates were centrifuged at 12,000× g for 20 min at 4 °C, and the supernatants were collected for enzymatic assays.

The activity of superoxide dismutase (SOD) was determined following Elstner and Heupel [64], based on its ability to inhibit nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) photoreduction at 560 nm. Peroxidase (POD) activity was assayed as described by Kochba et al. [68], by monitoring the increase in absorbance at 470 nm due to guaiacol oxidation. Dehydroascorbate reductase (DHAR) activity was assayed according to Shi et al. [69] by monitoring the increase in absorbance at 265 nm due to ascorbate formation in a GSH-dependent reaction. Catalase (CAT) activity was evaluated following Patra et al. [70], by recording the decrease in absorbance at 240 nm caused by H2O2 decomposition. Ascorbate peroxidase (APX) activity was measured according to Nakano and Asada [71], based on the decline in absorbance at 290 nm due to ascorbic acid oxidation. Glutathione reductase (GR) activity was assayed according to Foyer and Halliwell [72], by monitoring the decrease in absorbance at 340 nm linked to NADPH oxidation during the reduction of GSSG.

4.7. Determination of Ascorbate and Glutathione

Ascorbic acid (AsA) and dehydroascorbic acid (DHA) contents were assayed following the method of Hodges et al. [73] with slight adjustments. Fresh cucumber leaves (0.3 g) were homogenized in 2 mL of extraction buffer containing 5% (v/v) metaphosphoric acid and centrifuged at 12,000× g for 20 min at 4 °C. An aliquot of 100 μL supernatant was mixed with 500 μL phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 150 mM potassium iodide (KI) and 5 mM EDTA. For chromogenic development, sequential additions of ethanol (70%) with FeCl3 solution, FeCl3 (30 g L−1), and 10% TCA with 400 μL o-dipyridyl were performed, followed by incubation at 40 °C for 1 h. The absorbance was recorded at 525 nm. DHA concentration was calculated by subtracting the reduced AsA fraction from the total ascorbate pool.

Reduced glutathione (GSH) and oxidized glutathione (GSSG) were determined following the method of Griffith [74] and Ellman [75] using 5,5′-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB). Fresh leaf samples (0.3 g) were ground in 3 mL of extraction solution containing 0.5 mM EDTA and 3% TCA, and centrifuged at 15,000× g for 10 min at 4 °C. From the resulting supernatant, 0.2 mL was combined with 1.5 mL phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 7.0) and 0.2 mM DTNB, followed by incubation at 30 °C for 2 min. Absorbance was measured at 412 nm, and concentrations of GSSG and total glutathione were calculated from a calibration curve. GSH levels were obtained by subtracting GSSG values from the total glutathione content.

The contents of AsA, DHA, GSH, and GSSG were initially determined on a fresh weight (FW) basis and then converted to dry weight (DW) according to the corresponding fresh-to-dry weight ratio of each sample.

4.8. Quantitative RT–PCR Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from cucumber seedlings using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) in accordance with the instructions supplied by the manufacturer. The synthesis of first-strand cDNA was carried out with the TransScript All-in-One First-Strand cDNA Synthesis SuperMix for qPCR (TransGen Biotech, Beijing, China), which ensured efficient and complete reverse transcription.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was subsequently performed with gene-specific primers (sequences are provided in Table 2). Each reaction was prepared with equal amounts of cDNA template, and all assays were run in triplicate to guarantee reproducibility. PCR reactions were conducted using Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (TransGen Biotech, Beijing, China) on an ABI Prism 7900HT Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA).

The amplification profile included an initial denaturation, followed by cycles of annealing and extension under optimized conditions for each primer pair. The final concentration of primers was adjusted to 200 nM. Relative expression levels of target genes were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method, with Actin employed as the reference gene to normalize variations among samples.

4.9. Data Analysis

All data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA (SPSS 22.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), figures were plotted using GraphPad Prism version 9.5.1 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) and significant differences among means were determined by Duncan’s multiple range test at p < 0.05.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.S. and W.N.; validation, Y.G. and Q.H.; formal analysis, P.Q. and J.W.; data curation, H.G. and P.Q.; writing—original draft preparation, W.N.; writing—review and editing, Q.S. and C.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Taishan Scholars Program (tsqn202312290); the Agricultural Scientific and Technological Innovation Project of Shandong Academy of Agricultural Sciences (CXGC2025B05, CXGC2023A16, CXGC2024F19 and CXGC2025F18); the project supported by National Center of Technology Innovation for Comprehensive Utilization of Saline-Alkali Land, Grant (GYJ2023004); the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31372059, 30800751), the handong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (ZR2023QC051) and the Shandong Province “Bohai Grain Silo” Science and Technology Demonstration Project (2019BHLC005).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors affirm that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zou, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, J. Effect of exogenous spermidine on polyamine content and metabolism in tomato exposed to salinity–alkalinity mixed stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2012, 57, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; You, J.; Xu, X.; Yang, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, D.; Mu, L.; Zhuang, X.; Shen, Z.; Guo, C. Physiological and biochemical responses of Melilotus albus to saline and alkaline stresses. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, M.M.; Flexas, J.; Pinheiro, C. Photosynthesis under drought and salt stress: Regulation mechanisms from whole plant to cell. Ann. Bot. 2009, 103, 551–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, B.; Li, X.; Bloszies, S.; Wen, D.; Sun, S.; Wei, M.; Li, Y.; Yang, F.; Shi, Q.; Wang, X. Sodic alkaline stress mitigation by interaction of nitric oxide and polyamines involves antioxidants and physiological strategies in Solanum lycopersicum. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2014, 71, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Xu, Y.; Tang, Z.; Jin, S.; Yang, S. The impact of alkaline stress on plant growth and its alkaline resistance mechanisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Jin, Z.; Wang, S.; Gong, B.; Wen, D.; Wang, X.; Wei, M.; Shi, Q. Sodic alkaline stress mitigation with exogenous melatonin involves reactive oxygen metabolism and ion homeostasis in tomato. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 181, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Zhou, Z.; Cai, R.; Liu, L.; Wang, R.; Sun, Y.; Wang, D.; Yan, Z.; Guo, C. Metabolomic and physiological analysis of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) in response to saline and alkaline stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 207, 108338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Jia, L.; Baluška, F.; Ding, G.; Shi, W.; Ye, N.; Zhang, J. PIN2 is required for the adaptation of Arabidopsis roots to alkaline stress by modulating proton secretion. J. Exp. Bot. 2012, 63, 6105–6114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Tisarum, R.; Kohli, R.K.; Batish, D.R.; Cha-um, S.; Singh, H.P. Inroads into saline-alkaline stress response in plants: Unravelling morphological, physiological, biochemical, and molecular mechanisms. Planta 2024, 259, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, R.; Kapoor, P.; Mir, B.A.; Singh, M.; Parrey, Z.A.; Rakhra, G.; Parihar, P.; Khan, M.N.; Rakhra, G. Unlocking the versatility of nitric oxide in plants and insights into its molecular interplays under biotic and abiotic stress. Nitric Oxide 2024, 150, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, K.J.; Kaladhar, V.C.; Fitzpatrick, T.B.; Fernie, A.R.; Møller, I.M.; Loake, G.J. Nitric oxide regulation of plant metabolism. Mol. Plant 2022, 15, 228–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Ali, S.; Al Azzawi, T.N.I.; Yun, B.-W. Nitric oxide acts as a key signaling molecule in plant development under stressful conditions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajguz, A.; Hayat, S. Effects of brassinosteroids on the plant responses to environmental stresses. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2009, 47, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kagale, S.; Divi, U.K.; Krochko, J.E.; Keller, W.A.; Krishna, P. Brassinosteroid confers tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana and Brassica napus to a range of abiotic stresses. Planta 2006, 225, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, X.J.; Huang, L.F.; Zhou, Y.H.; Mao, W.H.; Shi, K.; Wu, J.X.; Asami, T.; Chen, Z.X.; Yu, J.Q. Brassinosteroids promote photosynthesis and growth by enhancing activation of Rubisco and expression of photosynthetic genes in Cucumis sativus. Planta 2009, 230, 1185–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divi, U.K.; Krishna, P. Brassinosteroid: A biotechnological target for enhancing crop yield and stress tolerance. New Biotechnol. 2009, 26, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vert, G.; Nemhauser, J.L.; Geldner, N.; Hong, F.; Chory, J. Molecular mechanisms of steroid hormone signaling in plants. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2005, 21, 177–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, T.W.; Guan, S.; Sun, Y.; Deng, Z.; Tang, W.; Shang, J.X.; Sun, Y.; Burlingame, A.L.; Wang, Z.Y. Brassinosteroid signal transduction from cell-surface receptor kinases to nuclear transcription factors. Nat. Cell Biol. 2009, 11, 1254–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.X.; Zhou, Y.H.; Ding, J.G.; Xia, X.J.; Shi, K.; Chen, S.C.; Asami, T.; Chen, Z.; Yu, J.Q. Role of nitric oxide in hydrogen peroxide-dependent induction of abiotic stress tolerance by brassinosteroids in cucumber. Plant Cell Environ. 2011, 34, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, W.; Gong, B.; Geng, B.; Wen, D.; Qiao, P.; Guo, H.; Shi, Q. The effects of exogenous 2,4-epibrassinolide on the germination of cucumber seeds under NaHCO3 stress. Plants 2024, 13, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.A.A.; Roosta, H.R.; Esmaeilizadeh, M.; Eshghi, S. Silicon and selenium supplementations modulate antioxidant systems and mineral nutrition to mitigate salinity-alkalinity stresses in cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) plants under hydroponic conditions. J. Plant Process Funct. 2022, 10, 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, W.; He, Q.; Ma, J.; Guo, H.; Shi, Q. Exogenous 2,4-epibrassinolide alleviates alkaline stress in cucumber by modulating photosynthetic performance. Plants 2024, 14, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, B.; Miao, L.; Kong, W.; Bai, J.-G.; Wang, X.; Wei, M.; Shi, Q. Nitric oxide, as a downstream signal, plays vital role in auxin-induced cucumber tolerance to sodic alkaline stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2014, 83, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, J.-X.; Li, X.; Li, C.; Zhao, L. The role of nitric oxide in plant responses to salt stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, W.; Gong, B.; Chen, Y.; Wang, J.; Wei, M.; Shi, Q. Photosynthetic capacity, ion homeostasis and reactive oxygen metabolism were involved in exogenous salicylic acid increasing cucumber seedlings tolerance to alkaline stress. Sci. Hortic. 2018, 235, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahanger, M.A.; Tomar, N.S.; Tittal, M.; Argal, S.; Agarwal, R.M. Plant growth under water/salt stress: ROS production; antioxidants and significance of added potassium under such conditions. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2017, 23, 731–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, A.; Nahar, K.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Fujita, M. Calcium supplementation improves Na+/K+ ratio, antioxidant defense and glyoxalase systems in salt-stressed rice seedlings. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, K.; Wu, Y. Footprints of divergent evolution in two Na+/H+ type antiporter gene families (NHX and SOS1) in the genus Populus. Tree Physiol. 2018, 38, 813–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nehrke, K.; Melvin, J.E. The NHX family of Na+/H+ exchangers in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 29036–29044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, W.-T.; Zhou, L.-B.; Liu, R.-Y.; Jin, W.-J.; Qu, Y.; Dong, X.-C.; Li, W.-J. Synergistic responses of NHX, AKT1, and SOS1 in the control of Na+ homeostasis in sweet sorghum mutants induced by 12C6+-ion irradiation. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 2017, 29, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Wei, P.; Liu, Z.; Yu, B.; Shi, H. Soybean Na+/H+ antiporter GmsSOS1 enhances antioxidant enzyme activity and reduces Na+ accumulation in Arabidopsis and yeast cells under salt stress. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2016, 39, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.-Q.; Hua, Y.-P.; Zhou, T.; Liu, Y.; Huang, J.-Y.; Yue, C.-P. Global landscapes of the Na+/H+ antiporter (NHX) family members uncover their potential roles in regulating the rapeseed resistance to salt stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumwald, E.; Aharon, G.S.; Apse, M.P. Sodium transport in plant cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2000, 1465, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Gong, B.; Jin, Z.; Wang, X.; Wei, M.; Yang, F.; Li, Y.; Shi, Q. Sodic alkaline stress mitigation by exogenous melatonin in tomato needs nitric oxide as a downstream signal. J. Plant Physiol. 2015, 186–187, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassil, E.; Tajima, H.; Liang, Y.-C.; Ohto, M.-A.; Ushijima, K.; Nakano, R.; Esumi, T.; Coku, A.; Belmonte, M.; Blumwald, E. The Arabidopsis Na+/H+ antiporters NHX1 and NHX2 control vacuolar pH and K+ homeostasis to regulate growth, flower development, and reproduction. Plant Cell 2011, 23, 3482–3497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yokoi, S.; Quintero, F.J.; Cubero, B.; Ruiz, M.T.; Bressan, R.A.; Hasegawa, P.M.; Pardo, J.M. Differential expression and function of Arabidopsis thaliana NHX Na+/H+ antiporters in the salt stress response. Plant J. 2002, 30, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, P.; Niyogi, K.; SenGupta, D.N.; Ghosh, B. Spermidine treatment to rice seedlings recovers salinity stress-induced damage of plasma membrane and PM-bound H+-ATPase in salt-tolerant and salt-sensitive rice cultivars. Plant Sci. 2005, 168, 583–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefi, K.; Jamei, R.; Darvishzadeh, R. Exogenous 24-epibrassinolide alleviates salt stress in okra (Abelmoschus esculentus L.) by increasing the expression of SOS pathway genes (SOS1–3) and NHX1,4. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2024, 30, 2051–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Q.; Zheng, X.; Tian, Y.; Wang, C. Exogenous brassinolide alleviates salt stress in Malus hupehensis Rehd. by regulating the transcription of NHX-type Na+(K+)/H+ antiporters. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, S.; Wani, K.I.; Naeem, M.; Khan, M.M.A.; Aftab, T. Cellular responses, osmotic adjustments, and role of osmolytes in providing salt stress resilience in higher plants: Polyamines and nitric oxide crosstalk. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2023, 42, 539–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hu, S.; Wang, X.; Yue, J.; Chen, D.; Han, M.; Qiao, W.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H. Response of anatomical structure and active component accumulation in Apocynum venetum L. (Apocynaceae) under saline stress and alkali stress. Plants 2025, 14, 2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavender-Bares, J.; Bazzaz, F.A. From leaves to ecosystems: Using chlorophyll fluorescence to assess photosynthesis and plant function in ecological studies. In Chlorophyll a Fluorescence: A Signature of Photosynthesis; Papageorgiou, G.C., Govindjee, Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2004; pp. 737–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaji, H.M.; Jajoo, A.; Oukarroum, A.; Brestic, M.; Zivcak, M.; Samborska, I.A.; Cetner, M.D.; Łukasik, I.; Goltsev, V.; Ladle, R.J. Chlorophyll a fluorescence as a tool to monitor physiological status of plants under abiotic stress conditions. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2016, 38, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, P.; Jajoo, A.; Mathur, S.; Bharti, S. Chlorophyll a fluorescence study revealing effects of high salt stress on photosystem II in wheat leaves. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2010, 48, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Yang, W.; Wen, M.; Jin, S.; Liu, Y. Hydrogen sulfide alleviates salinity stress in Cyclocarya paliurus by maintaining chlorophyll fluorescence and regulating nitric oxide level and antioxidant capacity. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 167, 738–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seleiman, M.F.; Ahmad, A.; Tola, E.; Alhammad, B.A.; Almutairi, K.F.; Madugundu, R.; Al-Gaadi, K.A. Exogenous application of 24-epibrassinolide confers saline stress and improves photosynthetic capacity, antioxidant defense, mineral uptake, and yield in maize. Plants 2023, 12, 3559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azaizeh, H.; Steudle, E. Effects of salinity on water transport of excised maize (Zea mays L.) roots. Plant Physiol. 1991, 97, 1136–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Ballesta, M.C.; Martínez, V.; Carvajal, M. Aquaporin functionality in relation to H+-ATPase activity in root cells of Capsicum annuum grown under salinity. Physiol. Plant. 2003, 117, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandeleur, R.K.; Mayo, G.; Shelden, M.C.; Gilliham, M.; Kaiser, B.N.; Tyerman, S.D. The role of plasma membrane intrinsic protein aquaporins in water transport through roots: Diurnal and drought stress responses reveal different strategies between isohydric and anisohydric cultivars of grapevine. Plant Physiol. 2009, 149, 445–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Raihan, M.R.H.; Masud, A.A.C.; Rahman, K.; Nowroz, F.; Rahman, M.; Nahar, K.; Fujita, M. Regulation of reactive oxygen species and antioxidant defense in plants under salinity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, J.; Chan, Z. ROS regulation during abiotic stress responses in crop plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, S.; Hou, X.; Liang, X. Response mechanisms of plants under saline–alkali stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 667458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, P.; Albalawi, T.H.; Altalayan, F.H.; Bakht, M.A.; Ahanger, M.A.; Raja, V.; Ashraf, M.; Ahmad, P. 24-Epibrassinolide (EBR) Confers Tolerance against NaCl Stress in Soybean Plants by Up-Regulating Antioxidant System, Ascorbate-Glutathione Cycle, and Glyoxalase System. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, G.; Xu, H.; Zhang, P.; Su, X.; Zhao, H. Effects of 2,4-epibrassinolide on photosynthesis and Rubisco activase gene expression in Triticum aestivum L. seedlings under a combination of drought and heat stress. Plant Growth Regul. 2017, 81, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Bhardwaj, R. Effects of 24-epibrassinolide on growth and metal uptake in Brassica juncea L. under copper metal stress. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2007, 29, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Xu, L.; Dong, S.; He, N.; Xi, Q.; Yao, D.; Wang, Q.; Zuo, Y.; Ling, C.; Qi, M.; et al. SaTDT enhanced plant tolerance to NaCl stress by modulating the levels of malic acid and citric acid in cells. Plant Mol. Biol. 2024, 115, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, M.; Tang, M.; Zhang, F.; Huang, Y. Influence of arbuscular mycorrhiza on organic solutes in maize leaves under salt stress. Mycorrhiza 2011, 21, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahjib-Ul-Arif, M.; Zahan, M.I.; Karim, M.M.; Imran, S.; Hunter, C.T.; Islam, M.S.; Mia, M.; Hannan, M.A.; Rhaman, M.S.; Hossain, M.A.; et al. Citric acid-mediated abiotic stress tolerance in plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Cui, D.; Zhao, X.; He, M. The important role of the citric acid cycle in plants. Genom. Appl. Biol. 2017, 8, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musazade, E.; Zhao, Z.; Shang, Y.; He, J.; Wang, Z.; Wu, M.; Xu, M.; Guo, L.; Feng, X. Differential responses of rice seedlings to salt and alkaline stresses: Focus on antioxidant defense, organic acid accumulation, and hormonal regulation. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2025, 25, 4323–4340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Lu, X.; Tao, Y.; Guo, H.; Min, W. Comparative ionomics and metabolic responses and adaptive strategies of cotton to salt and alkali stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 871387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnon, D.I. Copper enzymes in isolated chloroplasts. Polyphenoloxidase in Beta vulgaris. Plant Physiol. 1949, 24, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmedes, A.; Hølmer, G. A new thiobarbituric acid (TBA) method for determining free malondialdehyde (MDA) and hydroperoxides selectively as a measure of lipid peroxidation. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 1989, 66, 813–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elstner, E.F.; Heupel, A. Inhibition of nitrite formation from hydroxylammoniumchloride: A simple assay for superoxide dismutase. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 70, 616–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, B.D.; Macrae, E.A.; Ferguson, I.B. Estimation of hydrogen peroxide in plant extracts using titanium(IV). Anal. Biochem. 1984, 139, 487–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jambunathan, N. Determination and detection of reactive oxygen species (ROS), lipid peroxidation, and electrolyte leakage in plants. In Plant Stress Tolerance: Methods and Protocols; Sunkar, R., Ed.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fryer, M.J.; Oxborough, K.; Mullineaux, P.M.; Baker, N.R. Imaging of photo-oxidative stress responses in leaves. J. Exp. Bot. 2002, 53, 1249–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kochba, J.; Lavee, S.; Spiegel-Roy, P. Differences in peroxidase activity and isoenzymes in embryogenic ane non-embryogenic ‘Shamouti’ orange ovular callus lines. Plant Cell Physiol. 1977, 18, 463–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Ding, F.; Wang, X.; Wei, M. Exogenous nitric oxide protect cucumber roots against oxidative stress induced by salt stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2007, 45, 542–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, H.; Kar, M.; Mishra, D. Catalase activity in leaves and cotyledons during plant development and senescence. Biochem. Physiol. Pflanz. 1978, 172, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, Y.; Asada, K. Hydrogen peroxide is scavenged by ascorbate-specific peroxidase in spinach chloroplasts. Plant Cell Physiol. 1981, 22, 867–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foyer, C.H.; Halliwell, B. The presence of glutathione and glutathione reductase in chloroplasts: A proposed role in ascorbic acid metabolism. Planta 1976, 133, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodges, D.M.; Andrews, C.J.; Johnson, D.A.; Hamilton, R.I. Antioxidant compound responses to chilling stress in differentially sensitive inbred maize lines. Physiol. Plant. 1996, 98, 685–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, O.W. Determination of glutathione and glutathione disulfide using glutathione reductase and 2-vinylpyridine. Anal. Biochem. 1980, 106, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellman, G.L. Tissue sulfhydryl groups. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1959, 82, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).