Abstract

Anthracnose of pepper is a significant disease caused by Colletotrichum spp. In 2017 and 2021, 296 isolates were obtained from 69 disease samples. Through morphological analysis, pathogenicity detection, and polygenic phylogenetic analysis, the above strains were attributed to 10 species: C. scovillei, C. fructicola, C. karstii, C. truncatum, C. gloeosporioides, C. kahawae, C. boninense, C. nymphaeae, C. plurivorum, and C. nigrum. C. scovillei had the most strains (150), accounting for 51.02% of the total isolates; C. fructicola came in second (72 isolates), accounting for 24.49%. Regarding regional distribution, Zunyi City has the highest concentration of strains—92 strains total, or 34.18%—across seven species. Notably, this investigation showed that C. nymphaeae infected pepper fruit for the first time in China. Genetic diversity analysis showed that C. fructicola could be divided into seven haplotypes, and the population in each region had apparent genetic differentiation. However, the genetic distance between each population was not significantly related to geographical distance. Neutral detection and nucleotide mismatch analysis showed that C. fructicola might have undergone population expansion.

1. Introduction

Pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) is an important vegetable crop. There are about 2.1 million hectares of pepper planting area in China, and Guizhou Province has exceeded 300 thousand hectares [1], ranking first in China. In 2019, the chili pepper industry was listed as one of the “Twelve Characteristic Agricultural Industries” in Guizhou. The wider development of this industry has led to the annual expansion of the planting area. Factors such as limited cultivated land area have led to the increasingly prominent phenomenon of pepper continuous cropping, and the occurrence of soil-borne diseases, especially pepper anthracnose, has become increasingly severe.

Anthracnose is one of the principal plant diseases, the pathogen belonging to the genus Colletotrichum of the Coelomycetes of Deuteromycotina, and the fungi of this genus have a wide host range and often cause anthracnose of various crops [2]. The classification of Colletotrichum is complex because the genus has extremely complex genetic variation characteristics. Currently, the genus includes at least 14 species complexes and 13 singleton species [3]. Taxonomic research has evolved from morphological identification to a comprehensive evaluation system that includes morphological identification, pathogenicity detection, physiological characteristics, multi-gene joint tree-building analysis, and other indicators. Morphological identification mainly adopts the methods of Cai [4] and Sutton [5]. Detection indexes include colony culture morphology and growth rate, morphology and size of conidia and appressoria, presence and morphology of setae and sclerotia, etc. For phylogenetic analysis, at least 22 genes—including internal transcribed space (ITS), β-tubulin 2 (TUB2), actin (ACT), calmodulin (CAL), glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), histone3 (HIS3), chitin synthase 1 (CHS-1), histidinol dehydrogenase (HIS4), glutamine synthetase (GS), elongation factor 1α (EF1α), portions of the single-copy manganese superoxide dismutase (SOD 2), the 3′ end of the apurinic DNA lyase 2 (Apn2), the combined 5′ end of the mating-type idiomorph MAT1, the intergenic region of Apn2 and Mat1-2-1 (ApMat), and others—were used for molecular identification of Colletotrichum spp. [3]. In specific studies, the types and numbers of genes used by different scholars vary [4,6,7], with the top seven genes being used more frequently. Damm et al. [6,8,9,10,11,12] have used the above genes in studying multiple composite populations of Colletotrichum, as have Yang et al. [13], Liu et al. [14], and Diao et al. [15] when researching the pathogen of different plant anthracnose.

According to statistics, there were at least 31 species of pathogens causing pepper anthracnose [3,14,16,17], identified by multi-locus phylogeny, which were distributed in seven species complexes: C. acutatum complex (8), C. boninense complex (3), C. gloeosporioides complex (12), C. magnum complex (2), C. orchidearum complex (2), C. truncatum complex (1), C. spaethianum complex (1), and two singleton species, C. coccodes and C. nigrum. As many as 22 species have been reported in China [14,15,18]; among them, C. fructicola, C. gloeosporioides, C. scovillei, and C. truncatum were common strains. Effectively preventing and controlling anthracnose has become an important task. Currently, anthracnose prevention and control methods include using resistant varieties [19,20] and chemical agents [21,22] and identifying and screening biocontrol microorganisms [23,24]. Most of the above techniques target one or several types of anthrax bacteria. However, the pathogenicity of different strains of pepper and their sensitivity to pesticides are different [25,26,27,28], which makes it difficult to prevent and control pepper anthracnose.

To clarify the occurrence, main pathogen species, and distribution of pepper anthracnose in the main pepper-producing areas of Guizhou province, the disease survey and collection of disease samples were conducted in eight cities (prefectures). Pathogen isolation and purification, pathogenicity determination, and strain identification were carried out to pave the way for the next step of prevention and control.

2. Results

2.1. Typical Symptoms of Pepper Anthracnose

The survey found that pepper anthracnose could occur from seedling to harvest and infect stems, leaves, and fruits (Figure 1). The pepper seedlings in the cold bed nursery and the leaves and stems from the field transplanting to the fruiting period (April to May) were susceptible to infection (Figure 1A–E). The pepper fruit from the green ripening period to the harvest period (mid-late July to late September) was the most seriously affected, which could easily cause severe economic losses.

Figure 1.

Typical symptoms of pepper anthracnose. Notes: (A)—initial symptoms of leaf infection with Colletotrichum sp.; (B,C)—acervuli on leaf; (D)—initial symptoms of stem infection with Colletotrichum sp.; (E)—the later symptoms of stem infection with Colletotrichum sp.; (F–H)—initial symptoms of fruits infection with Colletotrichum sp.; (I–R)—different symptoms of fruits infection with Colletotrichum sp. in the later stage.

At the initial stage of infection, the leaves and stems showed dark green water-immersed spots (Figure 1A,D), and at the later stage, the centers of the disease spots were brown or gray-white, commonly with black acervuli, either scattered or in concentric rings (Figure 1B,C,E).

At the early stage of the disease, it appeared in the pepper fruit as a round disease spot, usually in the form of water immersion (Figure 1F–H), and at the later stage, it formed a concave or non-concave disease spot. The disease spot had obvious or non-obvious concentric rings, and the color of the disease spot was brown, gray-white, or black. When the humidity was high, it was easy to produce an orange-red conidia pile; when the air was dry, the black acervuli with or without setae could be seen (Figure 1I–R), or the fruit peel was membranous and cracked.

2.2. Pathogen Morphological Characteristics

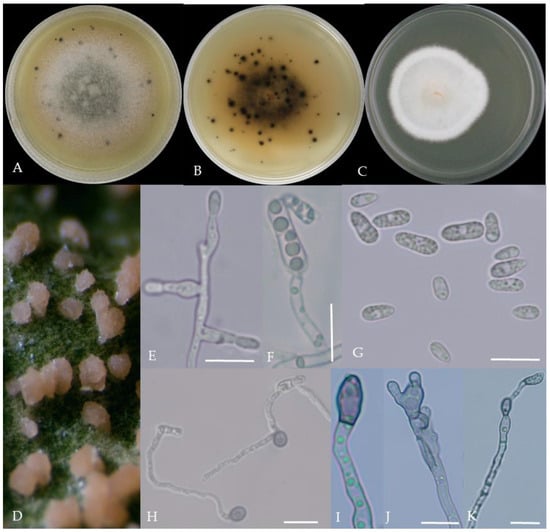

From the perspective of colony morphology (Table 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11), the isolate could be divided into 10 groups. Group 1 was significantly different from other colonies. After seven days of colony growth, these became orange-red, milky white, or gray, and villiform; a large number of cylindrical to oval conidia were produced on the mycelium, and about 1 month later, they produced black sclerotia.

Table 1.

Morphological characteristics of each Colletotrichum group.

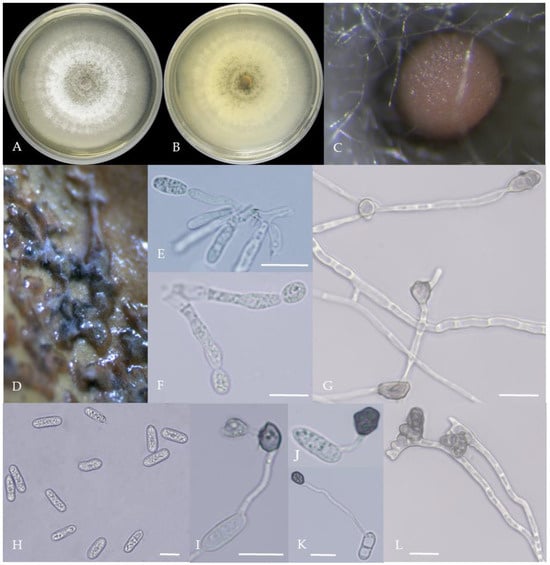

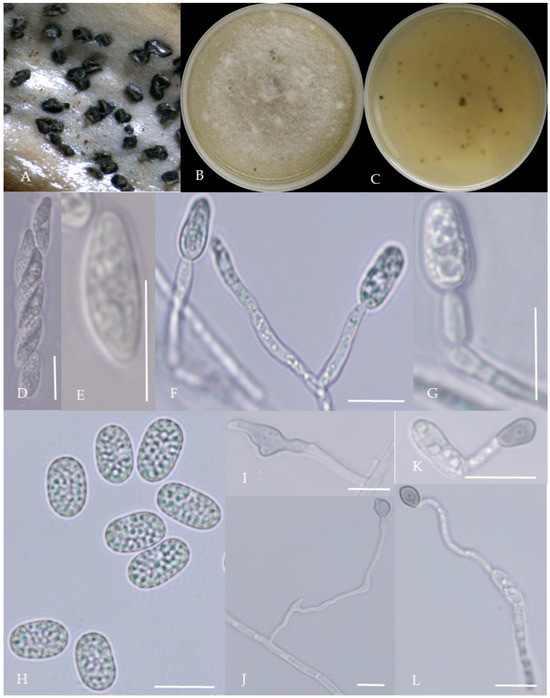

Figure 2.

Morphological characteristics of Group 1 (C. scovillei). Notes: (A–C)—colonies on PDA above and below; (D)—conidia piles on the host; (E,F)—conidiophore; (G)—conidia; (H)—conidia appressorium; (I–K)—hyphal appressorium. Scale bars are 10 μm, the same as below.

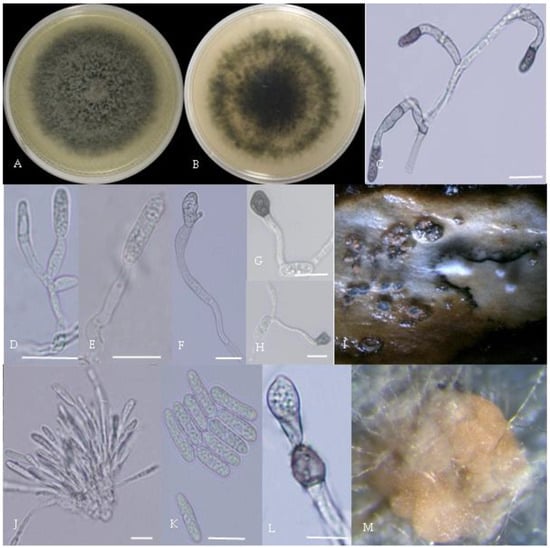

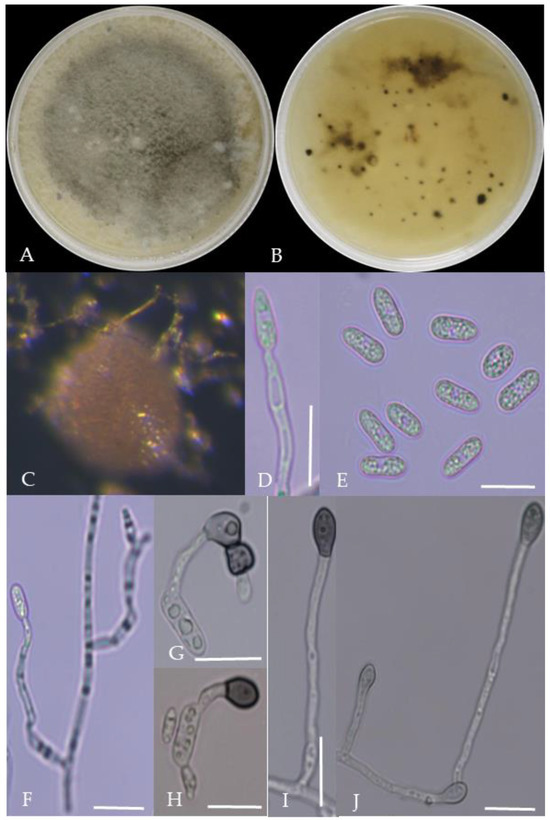

Figure 3.

Morphological characteristics of Group 2 (C. fructicola). Notes: (A,B)—front and back of colony; (C,F,L)—hyphal appressorium; (D,E)—conidial peduncle and conidial disk; (G,H)—conidia appressorium; (I,J)—conidia disk on the host; (K)—conidia; (M)—conidia pile.

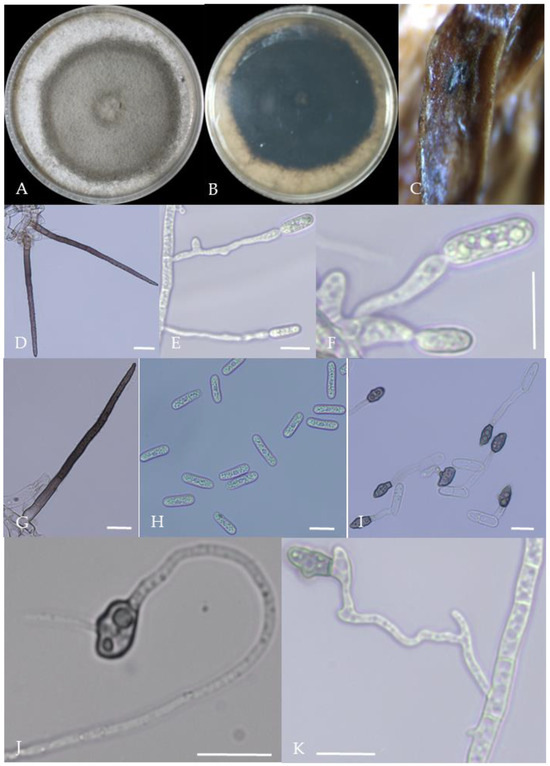

Figure 4.

Morphological characteristics of Group 3 (C. karstii). Notes: (A,B)—colony front and back; (C)—conidia pile on PDA; (D)—conidia pile on the host; (E,F)—conidiophore; (H)—conidia; (I–K)—conidia appressorium; (G,L)—hyphal appressorium.

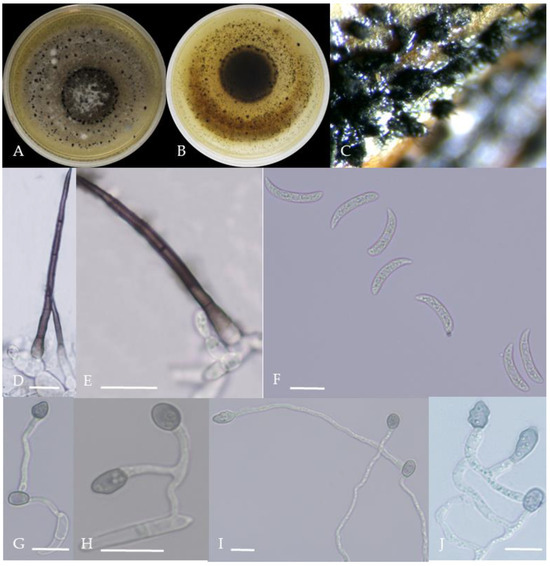

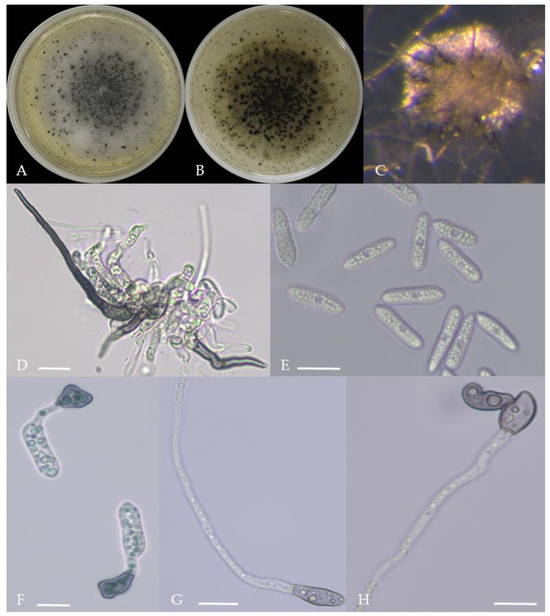

Figure 5.

Morphological characteristics of Group 4 (C. truncatum). Notes: (A,B)—colony front and back; (C)—the conidia pile on the host; (D,E)—bristles; (F)—conidia; (G,H)—conidia appressorium; (I,J)—hyphal appressorium.

Figure 6.

Morphological characteristics of Group 5 (C. gloeosporioides). Notes: (A)—disease spots on the host caused by C. gloeosporioides; (B,C)—front and back of colony; (D)—conidia; (E–H)—hyphal appressorium.

Figure 7.

Morphological characteristics of Group 6 (C. kahawae). Notes: (A,B)—colony above and below; (C)—conidia pile on the host; (D)—conidia pile on WA; (E,F)—conidiophore; (G)—conidia; (H,I)—conidia appressorium; (J,K)—hyphal appressorium.

Figure 8.

Morphological characteristics of Group 7 (C. boninense). Notes: (A)—conidia disk on the host; (B,C)—above and below of colony; (D,E)—sporangium and ascospore; (F,G)—conidiophore; (H)—conidia; (I,J)—hyphal appressorium; (K,L)—conidia appressorium.

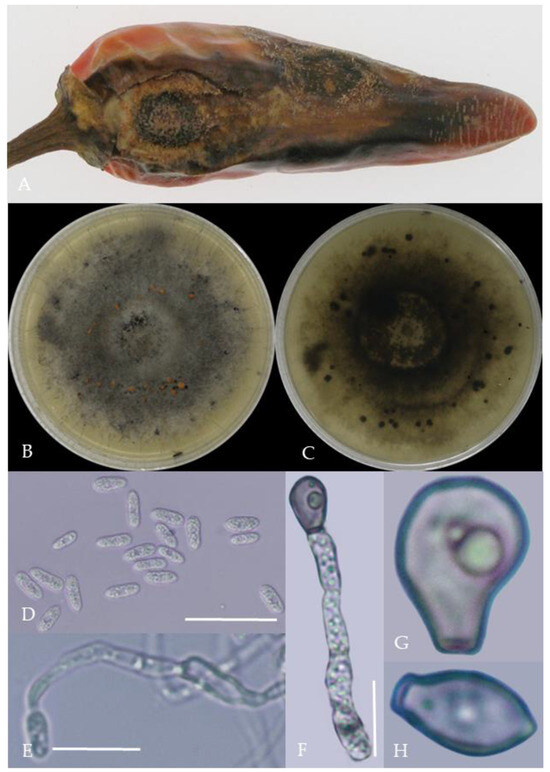

Figure 9.

Morphological characteristics of Group 8 (C. nymphaeae). Notes: (A,B)—colony above and below; (C)—conidia pile on WA; (D,F)—conidiophore; (E)—conidia; (G,H)—conidia appressorium; (I,J)—hyphal appressorium.

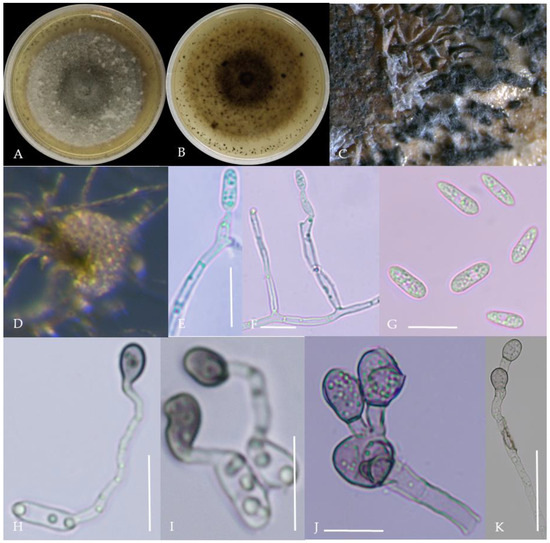

Figure 10.

Morphological characteristics of Group 9 (C. plurivorum). Notes: (A,B)—colony above and below; (C)—disease spot on the host; (D,G)—bristles; (E,F)—conidiophore; (H)—conidia; (I)—conidia appressorium; (J,K)—hyphal appressorium.

Figure 11.

Morphological characteristics of Group 10 (C. nigrum). Notes: (A,B)—colony above and below; (C)—conidia pile on WA; (D)—seta; (E)—conidia; (F)—conidia appressorium; (G,H)—hyphal appressorium.

Gray colonies included seven groups. Group 2 colonies were gray, with lush and fluffy hyphae, grayish green on the back, with no sclerotia and long cylindrical conidia; orange-red conidia piles could be produced on WA media. Group 4 was dark gray to light gray, with sparse hyphae, producing many scattered black sclerotia and crescent-shaped conidia, with one end rounded and one tapered. The colonies of Group 5 were light gray and fluffy, with orange-red conidia piles and black sclerotia produced in the later stage, and the conidia were cylindrical to oval in shape. The colonies of Group 6 were light gray, with dense hyphae that were like a tapestry, and the back of the colonies were brown; in the later stage, scattered black small sclerotia and conidia piles formed on the WA, and the conidia were cylindrical to oval in shape. Group 8 was light gray, with dense tapestry-like hyphae, milky white to light yellow on the back, scattered with a small number of sclerotia; orange conidia piles were produced on the WA, and the conidia were nearly round or cylindrical. Group 9 colonies were dark gray in the middle, with milky white edges, dense tapestry-shaped hyphae, dark gray to black on the back, and long cylindrical conidia. The colonies of Group 10 were gray, with a darker color in the middle; the hyphae were luxuriant and fluffy, with a large number of black sclerotia scattered; orange conidia piles produced on the WA, and brown seta were visible; the conidia were obtusely rounded at both ends, forming a long cylindrical shape, or one end was obtusely rounded and the other end was gradually pointed, forming a stick shape.

There were two groups with white colonies. Group 3 had white colonies with apparent concentric rings, and in the later stage, gray sclerotia was produced in the center of the colonies, while the back of the colonies was light yellow; orange-red conidia piles produced on WA medium, and the conidia were cylindrical-shape. Group 7 colonies were white, with dense tapestry-like hyphae, pale yellow on the back, producing gray sclerotia and cylindrical conidia; sometimes sexual asci and ascospores could be seen, and the ascus contained 6–8 ascospores, which were spindle-shaped.

2.3. Pathogenicity Test

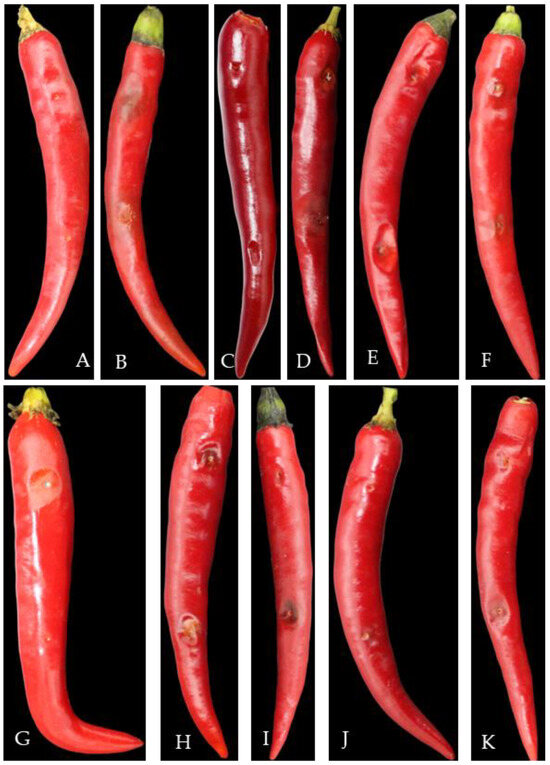

Seven days after inoculation with different pathogens, pepper fruit showed different symptoms of disease spots, similar to the symptoms of natural disease in the field, and no disease symptoms were observed in the control treatment (Figure 12). The pathogens isolated from diseased fruits had the same morphological characteristics as the inoculated pathogens.

Figure 12.

Pathogenicity test of pepper anthracnose pathogens. Note: (A)—CK, (B)—C. fructicola, (C)—C. gloeoporioides, (D)—C. nymphaeae, (E)—C. scovillei, (F)—C. kahawae, (G)—C. boninense, (H)—C. nigrum, (I)—C. plurivorum, (J)—C. karstii, (K)—C. truncatum.

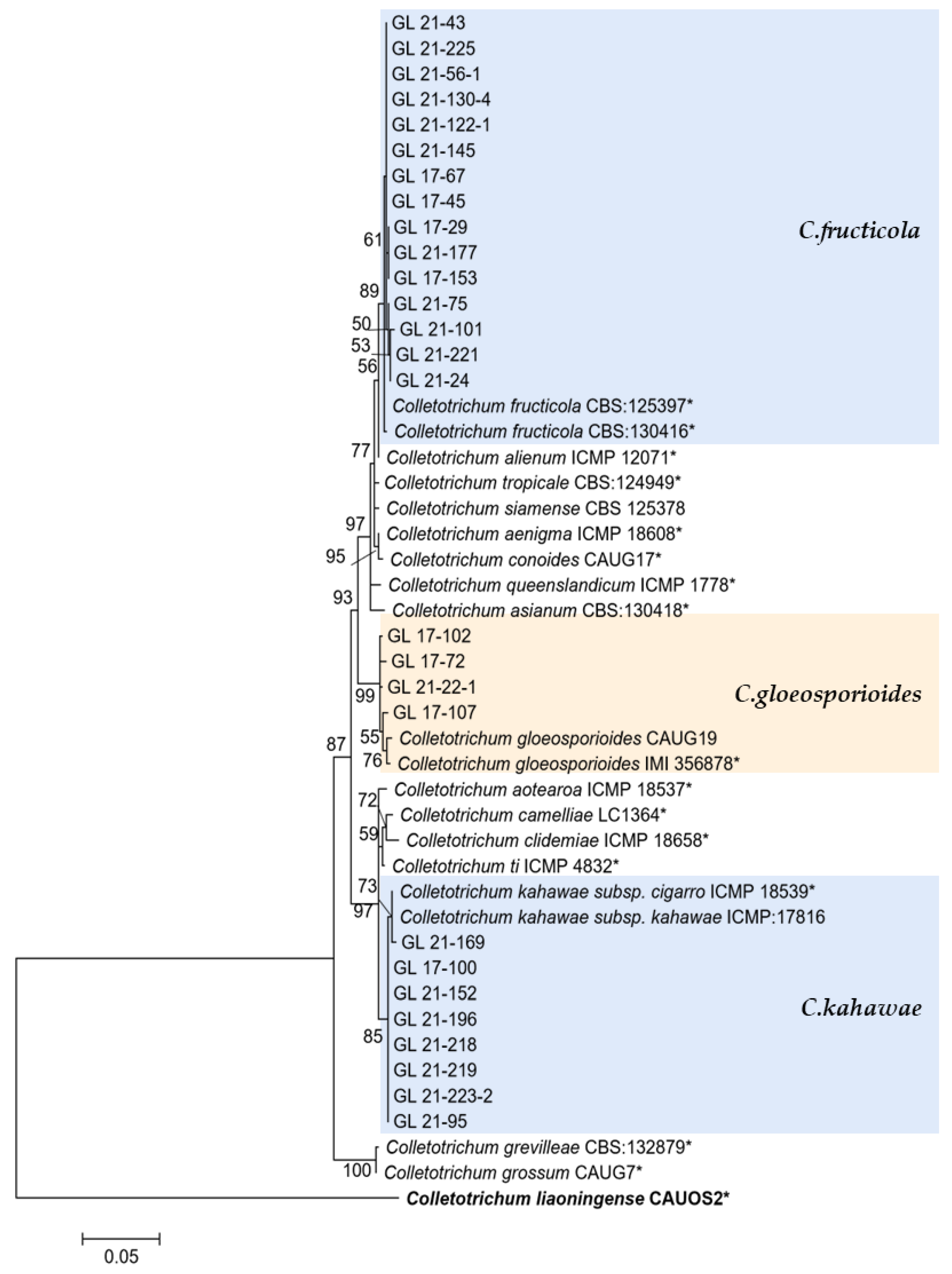

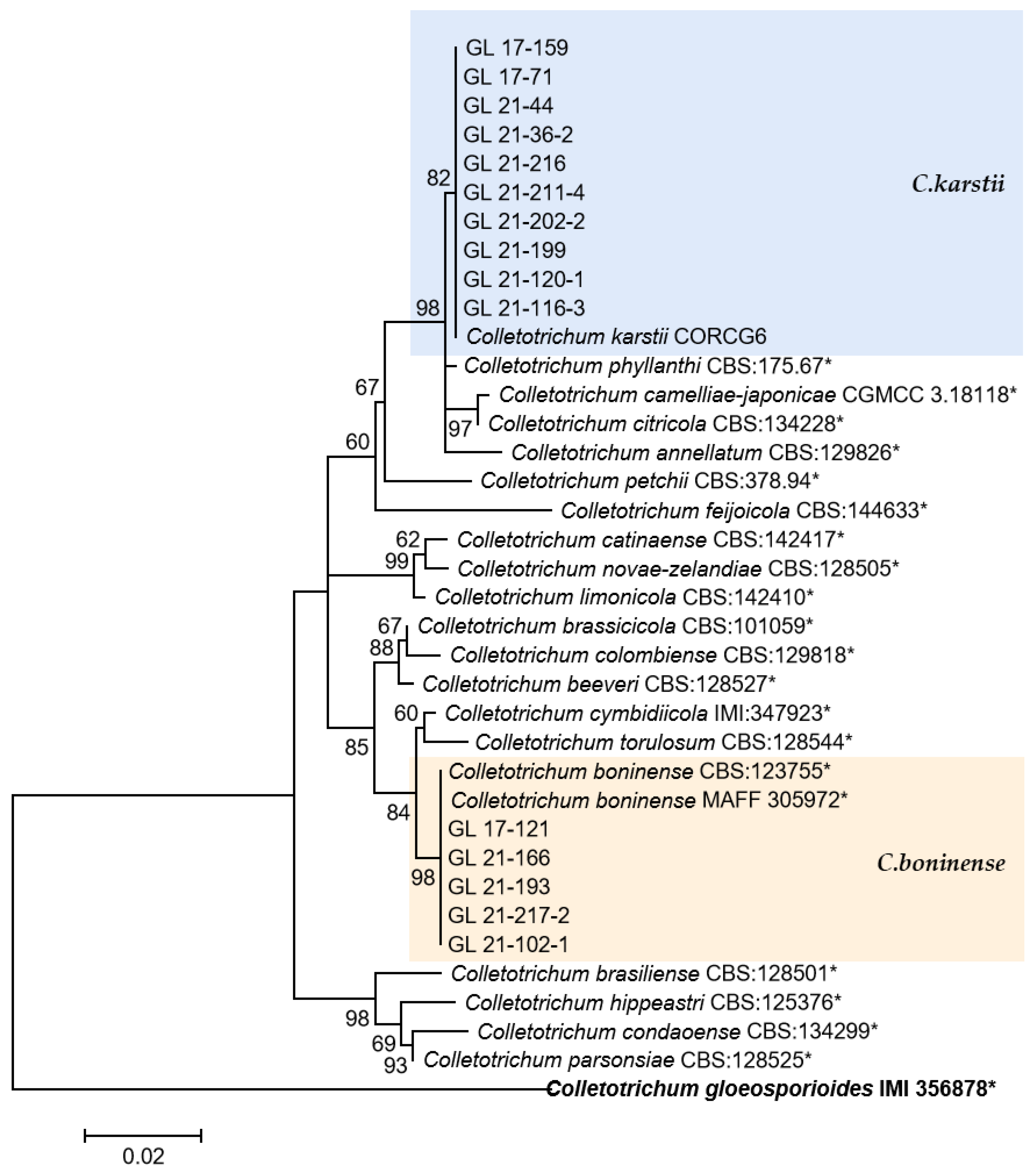

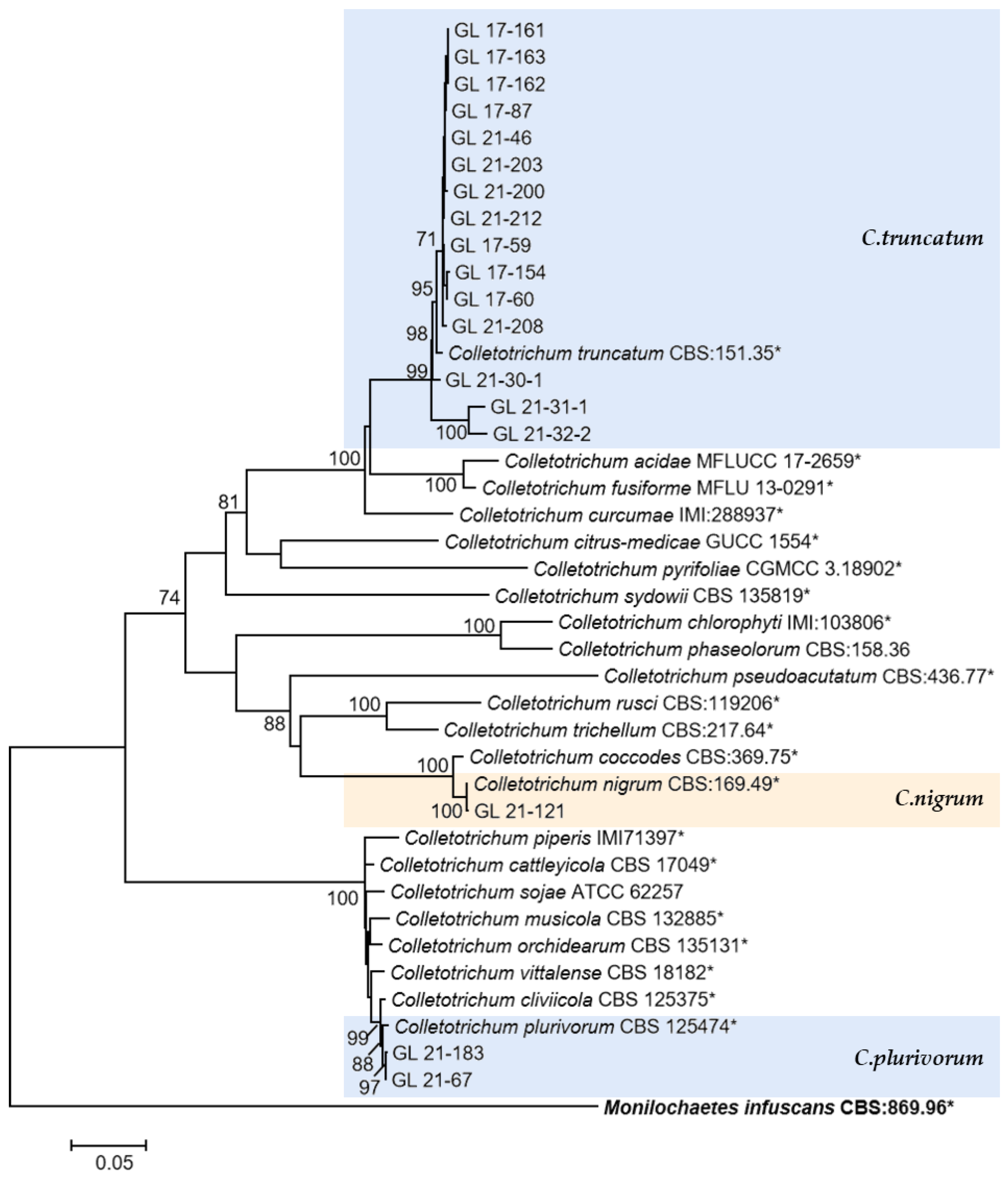

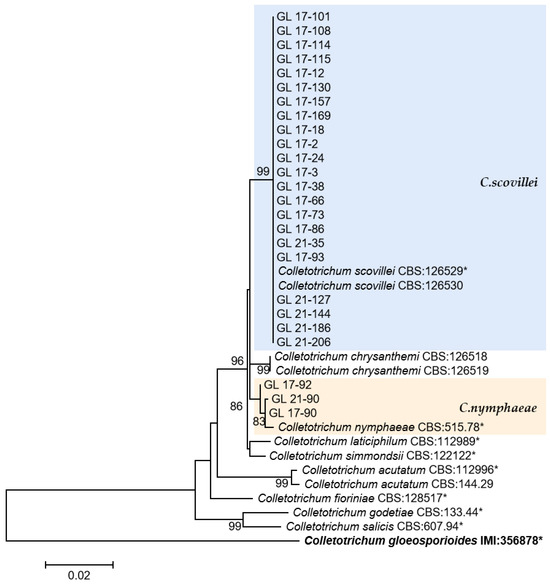

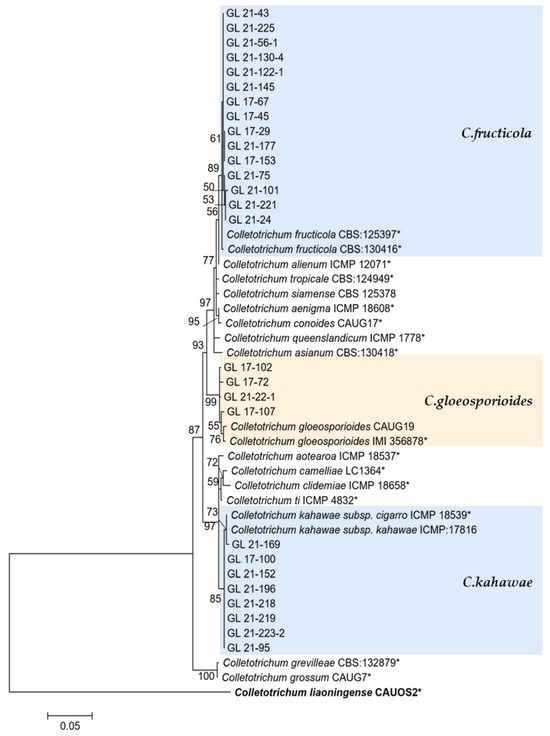

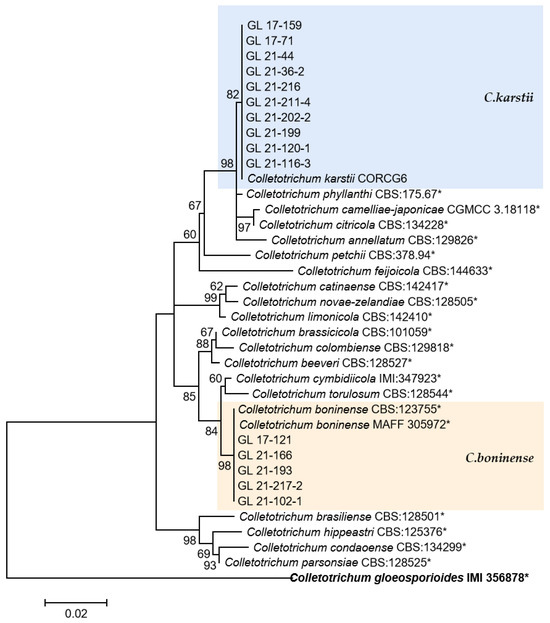

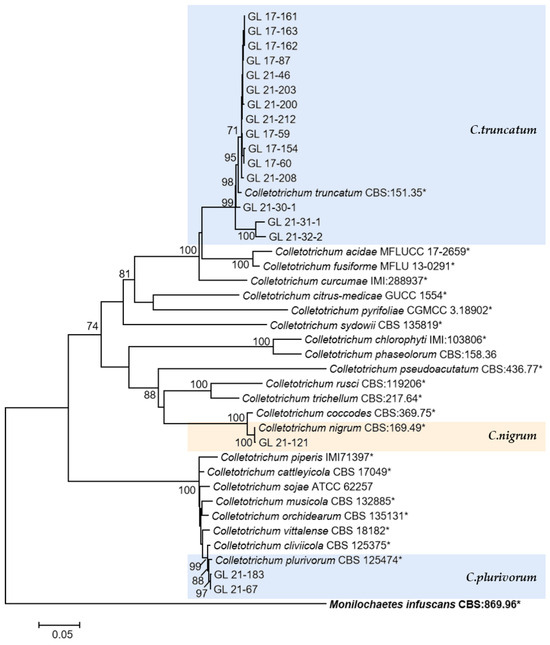

2.4. Polygenic Phylogenetic Analysis

The multi-locus phylogenetic analysis based on five to six genes (Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5) showed that 296 isolates belonged to 10 species (Figure 13, Figure 14, Figure 15 and Figure 16), of which 150 isolates were identified as C. scovillei, accounting for 51.02% of the total number of strains, followed by C. fructicola, C. karstii, C. truncatum, C. gloeosporioides, C. kahawae, and C. boninense. They numbered 74, 19, 17, 12, 10, and 8 isolates, respectively, accounting for 25.17%, 6.46%, 5.78%, 4.08%, 3.40%, and 2.72% of the total isolates. In addition, there were 3, 2, and 1 strains of C. nymphaeae, C. plurivorum, and C. nigrum, respectively.

Table 2.

The information on stains and isolates used for phylogenetic analysis of the C. acutatum species complex.

Table 3.

The information on stains and isolates used for phylogenetic analysis of the C. gloeosporioides species complex.

Table 4.

The information on stains and isolates used for phylogenetic analysis of the C. boninense species complex.

Table 5.

The information on stains and isolates used for phylogenetic analysis of the C. truncatum species complex and other species.

Figure 13.

The C. acutatum complex. Notes: This development tree was constructed by the Maximum Likelihood method in MEGA 6.06 software after six genes, such as ITS, ACT, CHS-1, GADPH, TUB2, and HIS 3, were compared and spliced by SequenceMatrix. The number on the branch node represents the support rate obtained by Bootstrap replication calculation 1000 times. The sample strains in the figure were only representative strains in the isolated strains, and the strains with * were type, ex-type, or ex-epitype strains. Bold represents the outgroup.

Figure 14.

The C. gloeosporioides complex. Notes: The strains with “*” were ex-type or ex-epitype cultures. Bold represents the outgroup.

Figure 15.

The C. boninense complex. Notes: The strains with “*” were ex-type or ex-epitype cultures. Bold represents the outgroup.

Figure 16.

The C. truncatum complex, C. orchidearum complex, and the singleton species. Notes: The strains with “*” were ex-type or ex-epitype cultures. Bold represents the outgroup.

This was the first report of C. nymphaeae-caused anthracnose in chili peppers in China. Two isolates were isolated from Huangping County of Qiandongnan State in 2017 and one isolate was from Ziyun County of Anshun City in 2021. Whether there is a risk of diffusion of this pathogen in chili peppers remains to be studied.

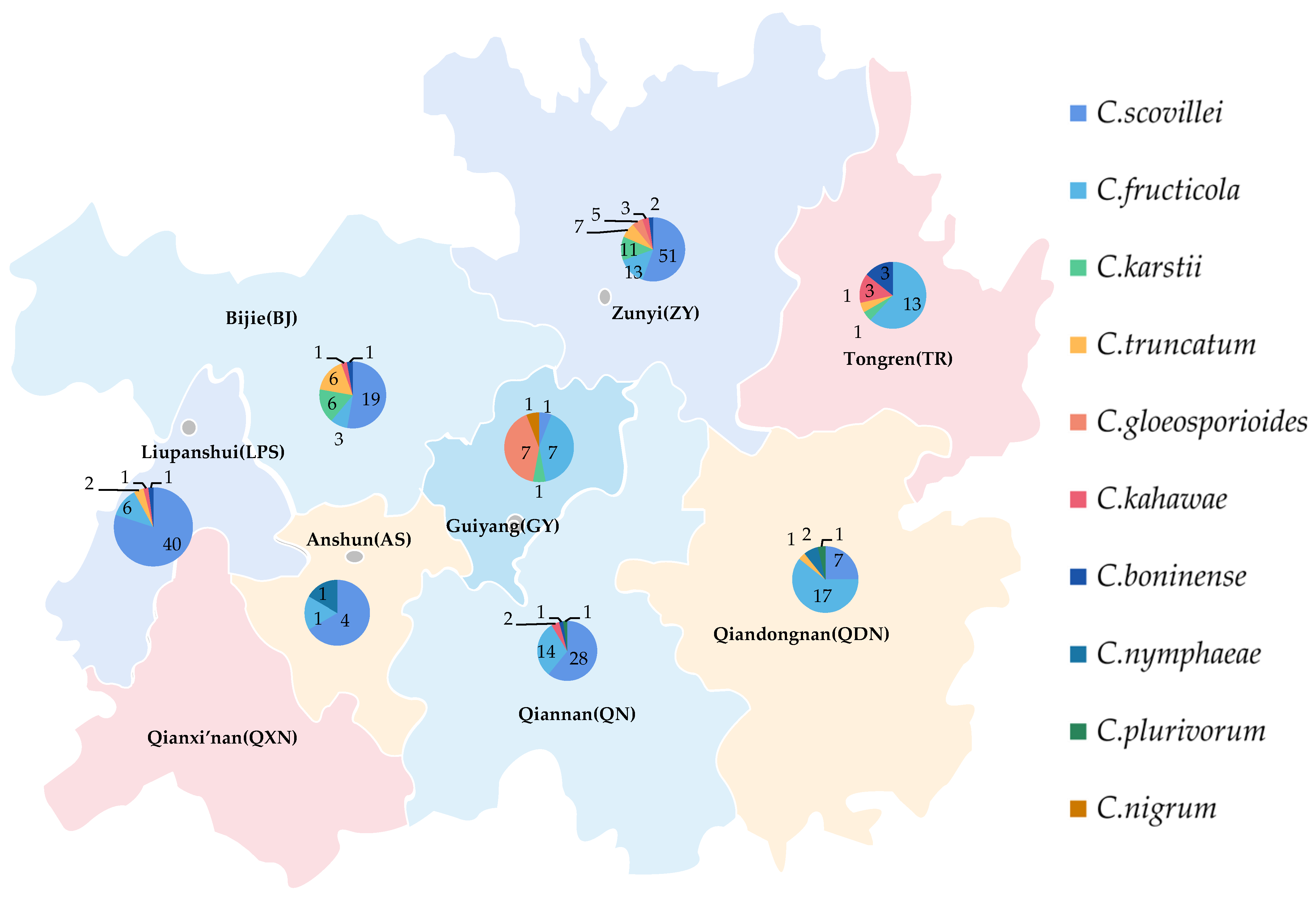

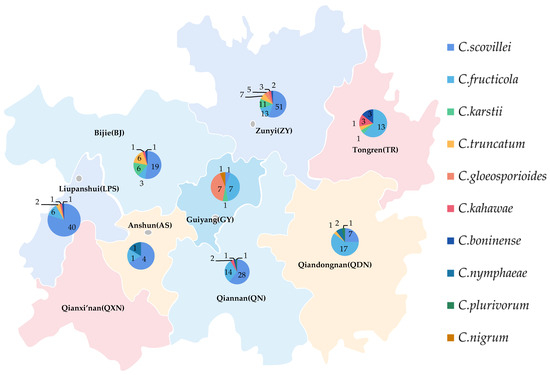

2.5. Geographical Distribution of Pathogens

There was a significant disparity in the strains’ number of different species obtained from different times and locations (Figure 17). In total, 103 strains of C. scovillei were isolated in 2017, and 47 were isolated in 2021, ranking first in number of all species, which should make this the most important pathogen of pepper anthracnose in Guizhou Province. The number of strains of C. fructicola was 7 in 2017 and 67 in 2021; the number of strains identified as C. karstii was 2 and 17, respectively. The increasing number of strains of the above two species might indicate that the types of primary pathogens would change.

Figure 17.

Geographical distribution ten species of Colletotrichum spp. in Guizhou.

The distribution proportions of isolates’ number of different species in various regions were quite distinct (Figure 17). Among the eight regions, 91 isolates of the primary pathogens C. scovillei were isolated in Zunyi (ZY) and Liupanshui (LPS), accounting for 60.67% of the isolates of this species, followed by Qiannan (QN) and Bijie (BJ), with 28 and 19 isolates, respectively. The pathogens isolated in ZY included seven species, 92 isolates in total, accounting for 31.08% of the isolates. They were followed by LPS, QN, and BJ, accounting for 16.89% (five species), 15.88% (five species), and 12.16% (six species), respectively. The number of isolates and species from Anshun (AS) was the least, at six and three, respectively. The least number of species was of C. nigrum, whose only isolate was from Guiyang (GY).

2.6. Genetic Diversity of C. scovillei and C. fructicola

Polymorphism analysis was conducted on six genes of the top two species of isolate quantity, C. scovillei and C. fructicola. All six genes of 150 C. scovillei strains had no mutation sites. Therefore, no further analysis was conducted on this species.

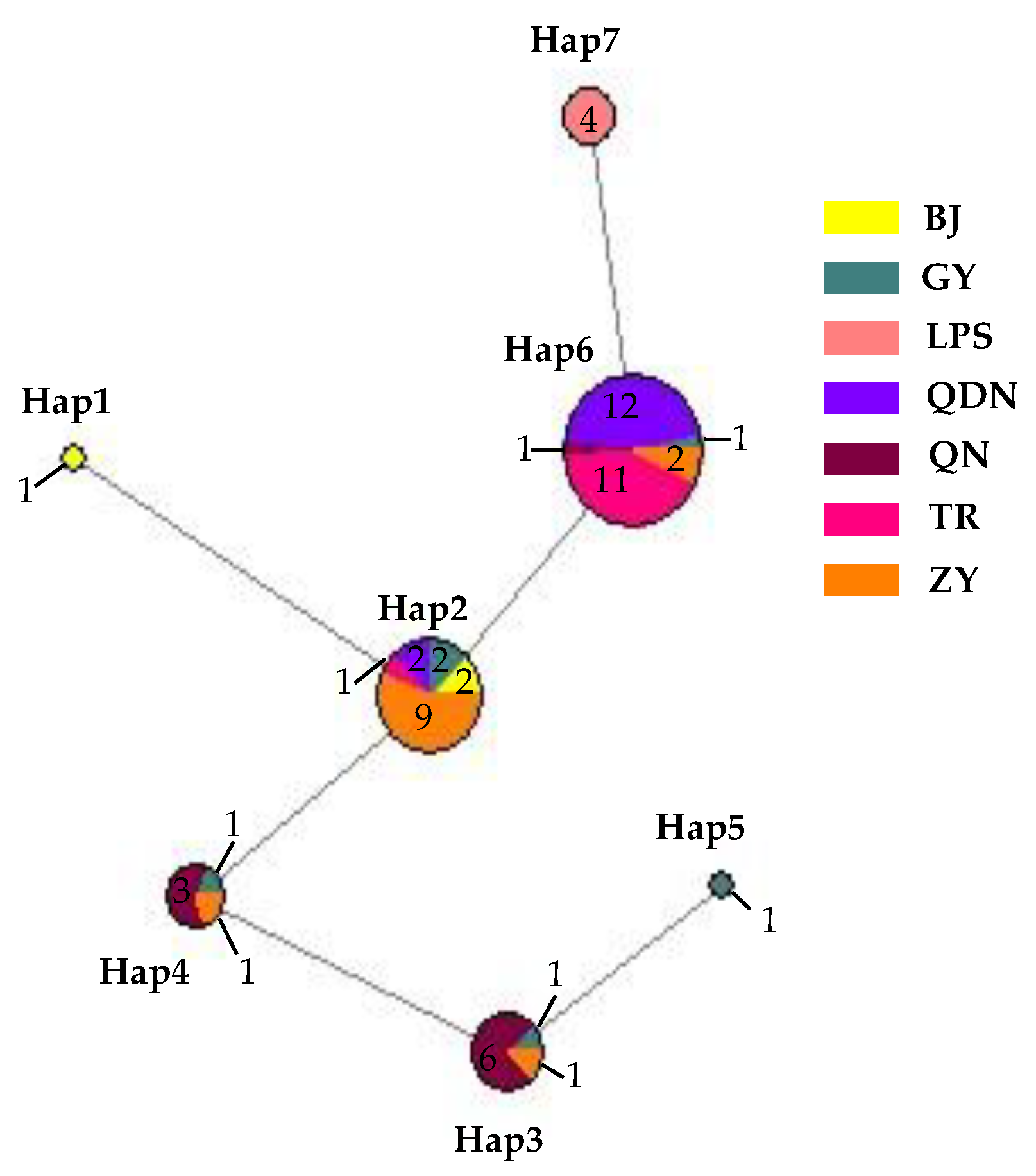

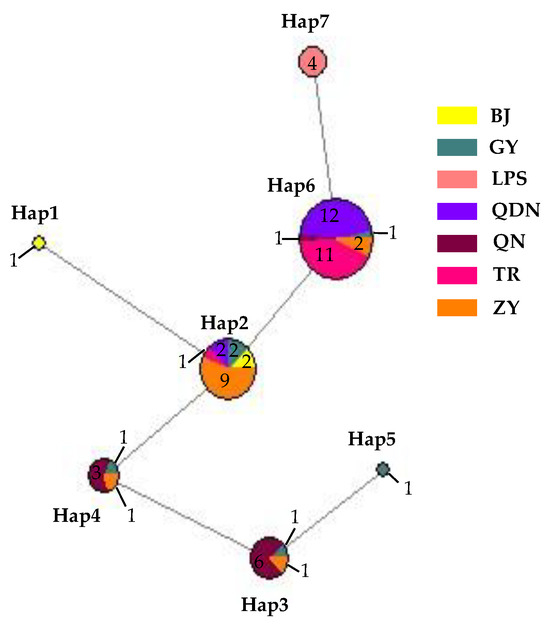

Nucleotide composition analysis of ITS-ACT-CHS1-GAPDH-TUB2-HIS3 from 62 isolates of C. fructicola showed a G+C content of 0.559, with seven sites with alignment gaps or missing data and a total of six polymorphic sites, including three parsimony informative sites and three singleton variable sites. These polymorphic sites produced a total of seven haplotypes (Hd = 0.7277) (Figure 18), with the highest number being haplotype 6 (abbreviated as Hap 6, the same below). It had 27 isolates, accounting for 43.55% of the total, with 12 isolates in QDN and 11 isolates in TR, which was the leading distribution area; in addition, ZY had two isolates, and GY and QN each had one isolate. The second was Hap 2, with a total of 16 isolates, accounting for 25.80% of the total number of isolates, mainly distributed in ZY (9); in addition, there were two each in GY, BJ, and QDN, and one isolate in TR, respectively. Hap 1 and Hap 5 had one isolate isolated from BJ and GY, respectively. From the distribution of different haplotypes in various regions, the number of GY isolates was small, but the haplotypes were the highest, including all haplotypes except for Hap 1 and Hap 7; next was ZY, which contains 4 haplotypes; and the least was LPS, which only has Hap 7, and this haplotype was only distributed here, not found in other regions.

Figure 18.

Network diagram and geographical distribution of C. fructicola.

The analysis results conducted using GeneAlex showed a positive correlation (Rxy = 0.004) between the genetic distance and the geographical distance of C. fructicola. However, the correlation was not significant (p = 0.440). That indicated a certain degree of genetic differentiation among the population in different regions of Guizhou Province, but that this differentiation was not significantly correlated with geographical distance.

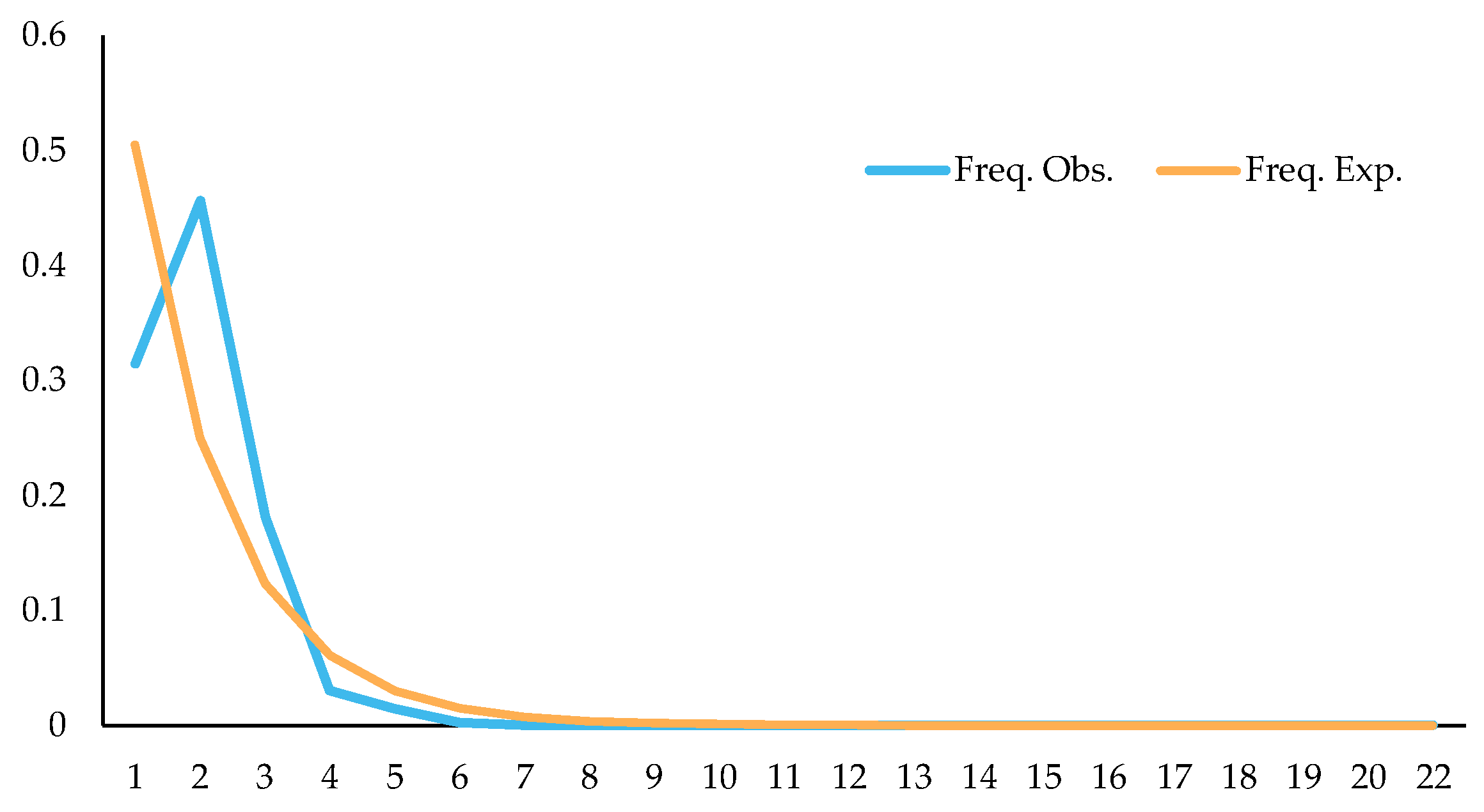

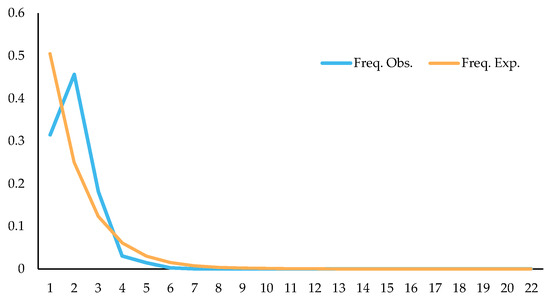

Studying changes in population dynamics by using neutral detection methods, results showed that Tajima’s D = −0.5689 (p > 0.10), Fu and Li’s D = −1.5171 (p > 0.10), and Fu and Li’s F = −1.4243 (p > 0.10); through mismatch distribution analysis of splicing sequences, it was found that the expected values were roughly consistent with the observed values, and the observed values showed a single peak (Figure 19). The above detection results indicated that C. fructicola might have population expansion, which might be why the population has no clear genetic differentiation among some regions, and one of the reasons why the correlation between genetic distance and geographical distance was not significant.

Figure 19.

Mismatch distribution of C. fructicola population.

The Fst value (Table 6) could be used to preliminarily analyze the genetic differentiation relationship of the C. fructicola populations among different regions. Analysis results demonstrated that there was minimal genetic differentiation in the C. fructicola population of BJ and ZY, GY and ZY, LPS and QDN, and QDN and TR (0.05 < Fst < 0.15), while there was no genetic differentiation between LPS and TR (Fst = 0). Meanwhile, the Fst between other populations was greater than 0.25, which indicates significant genetic differentiation among the C. fructicola populations between these regions.

Table 6.

Fst of C. fructicola between different populations.

3. Discussion

This study aimed to understand the main hazards and typical symptoms of pepper anthracnose and identify the types and distribution of pathogens that cause pepper anthracnose in Guizhou Province. Field observations found that this disease could occur from the seedling stage to the fruit ripening period. At the seedling stage, it mainly infected leaves, and it became increasingly severe from the green ripening to the complete ripening stage of fruits, with the occasional occurrence of stem infections. At the early stage of the disease, various tissues often exhibited light brown water-soaked lesions. At the later stage of the disease, most leaves and stems showed spherical black acervuli with seta, while the fruit symptoms were relatively diverse. Some lesions were sunken, and some were characterized by exfoliation of the stratum corneum without significant sunkenness. On some could be seen scattered or ring-shaped black acervuli, and on others orange-red conidial masses; the above symptoms may be related to the climatic environment [29]. Some disease spots might have compound infections and complex symptoms. In short, it was difficult to distinguish the types of pathogens from disease symptoms, and scientific methods were needed to identify them.

Through morphological and phylogenetic analysis, and pathogenicity identification, 296 strains of Colletotrichum were identified as C. scovillei (150 strains, 51.02%), C. fructicola (74 strains, 25.17%), C. karstii (19 strains, 6.46%), C. truncatum (17 strains, 5.78%), C. gloeosporioides (12 strains, 4.08%), C. kahawae (10 strains, 3.40%), C. boninense (8 strains, 2.72%), C. nymphaeae (3 strains, 1.02%), C. plurivorum (2 strains, 0.68%) and C. nigrum (1 strain, 0.34%), respectively.

Morphological identification is the most fundamental aspect of fungal species identification. Cai et al. [4] suggested that a mycelial disc (about 4 mm) be taken from the edge of a five-day-old colony with vigorous activity and inoculated in PDA plates at 20 °C, 25 °C, and 30 °C under constant fluorescence light to observe the growth rate and morphological characteristics of the Colletotrichum fungi. However, Damm et al. [8,9,10,11,12] still used their method to observe the features of the colony and characteristic structures. They used the SNA and OA cultures to incubate at 20 °C under near-UV light with a 12 h photoperiod for 10 d. Torres-Calzada et al. [30] placed the mycelial plugs onto the PDA dishes and incubated them at 25 °C for seven days to describe the colonies’ growth rate, color, shape, and conidial morphology of C. truncatum. By this token, there is still no unified standard for the cultural conditions used for the morphological identification of Colletotrichum. In the present study, we used PDA culture medium; the colony growth diameter and spore production were measured after seven days of natural light cultivation at 28 °C. After 30 days of cultivation, we observed whether the sclerotia and spore production structure were produced. The isolates had significant morphological differences, and preliminary grouping could be conducted based on morphological characteristics. Still, the results differed from those of Liu et al. [14] regarding growth rate, conidia, and appressorium morphology. Different cultural conditions probably caused this. The morphology of pathogens was relatively sensitive to environmental conditions. Therefore, Cai et al. [4] believed that many problems in species identification could not be solved entirely solely through physiology, but that it was possible to establish specification boundaries for existing names and introduce new specifications through the polymorphic approach.

From the analysis of morphological characteristics, most of the colonies of C. scovillei were orange-red or light gray, villous, and had significant differences in morphology from other Colletotrichum species, making them easier to distinguish. However, in this study, one isolate that did not produce orange-red pigment or conidia and had a slow growth rate was identified as C. scovillei by phylogenetic analysis. Pathogenicity testing showed that this strain could cause anthracnose in green and red ripe fruits of chili peppers; when the humidity was high, orange-red conidia piles were produced. The strain obtained from re-isolation was similar to other C. scovillei isolates. The reason for the variation of this isolate was still unclear. The setae of C. fructicola were rarely found. Yang [18] found no seta in the strain isolated from chili peppers. Liu et al. [31] only found one bristle in C. fructicola isolated from Camellia. In this study, setae were found on one conidial disk of WA medium, and their morphological characteristics were consistent with Liu et al.’s description.

Multi-gene phylogenetic analysis is one of the critical research contents of Colletotrichum species identification, but different research teams use different genes. Crouch et al. used ITS, HMG, Apn2, Mat1-2, and SOD2 in 2006 and 2009 to identify various gramineous plant anthracnose pathogens and conducted phylogenetic and population genetic differences analysis on Colletotrichum cereale in different grassland populations. The Cai research group [13,15,32,33] conducted a classification analysis of Colletotrichum spp. They were isolated from different plants using ITS, ACT, GAPDH, HIS3, CHS-1, TUB2, CAL, and GS. Damm et al. [6,8,9,10,11,12,34] used the same genes (except GS) to comprehensively descript and identify Colletotrichum spp., which include Colletotrichum with curved conidia, C. acutatum, C. destructivum, C. dracaenophilum, C. magnum, and C. orchidearum species complexes, as well as C. eriobotryae sp. nov. and C. nymphaeae isolated from loquat fruit. This study utilized six common genes from the Cai research group and Damm et al. to conduct multi-locus phylogenetic analysis on isolates and identified 296 isolates as 10 Colletotrichum species.

Research has found that distinguishing between C. scovillei and C. guajavae in the C. acutatum complex is challenging. The GAPDH sequence between the two species has 7 bp base difference, making it the sequence with the most significant difference; ITS only has a 1 bp base difference, while there was no difference between the other four gene sequences. This research result was similar to the research conclusion of Damm et al. [8]. C. scovillei might have been isolated initially from chili peppers by Nierenberg et al. [35], and BBA 70349 (PD 94/921-3) and PD 94/921-4 isolated from Capsicum annuum were identified as C. acutatum based on morphology and RAPD-PCR. In 2008, Than et al. [36] isolated Mj6 from Capsicum annuum and identified it as C. acutatum based on morphological observations and phylogenetic trees established by ITS and TUB; Damm et al. [8] found a multi-locus phylogenetic tree using six genes, corrected the above three strains to be C. scovillei, and used one of them as an ex-type strain. Subsequently, Kanto et al. [37], Liu et al. [14], and Diao et al. [15] isolated C. scovillei from the anthracnose samples of Capsicum spp. In this study, C. scovillei accounted for 51.02% of the total isolates, suggesting that this species may be the primary pathogen causing pepper anthracnose in Guizhou Province.

In this study, except for C. scovillei, C. nymphaeae was the only other species from the C. acutatum species complex. The six gene sequences of this species had 2–7 bp differences from C. scovillei, respectively. This species has been reported to attack crops including strawberries [38], apples [39], citrus [40], tomatoes [41], and more. In China, diseases caused by C. nymphaeae infection have been found in grapevine [14], loquat [42], peach [43], walnut [44], tobacco [45], Camellia oleifera [46], et al. In 2016, this strain was isolated from chili peppers in Malaysia [47], and in this study, it was found for the first time that this species caused pepper anthracnose in China.

This study’s C. gloeosporioides species complex strains isolated from diseased chili peppers include C. gloeosporioides, C. fructicola, and C. kahawae. From the perspective of the phylogenetic tree structure, the distribution of these three species was similar to the research conclusion of Weir et al. [48], indicating that the six genes used in this study were reliable in the identification of C. gloeosporioides species complex isolates. There have been widespread reports of C. gloeosporioides infecting chili peppers, including in China [14,15,18], Malaysia [49], and India [50]. The C. gloeosporioides isolated in this study only accounted for 4.08% of the total isolates, and there were more isolates in 2017 (10), indicating that C. gloeosporioides might not be the main pathogen of chili anthracnose in Guizhou, and that its harm had a decreasing trend. C. fructicola was first discovered on coffee berries in Thailand, but it was later discovered that the strain had a very wide host and distribution range and had records of infecting chili peppers worldwide [51]. There were records of this species causing chili anthracnose in various chili planting areas in China [14,15,18]. In this study, given that a total of seven isolates were isolated in 2017, and 67 isolates were isolated in 2021, it was the second most abundant strain, so it was one of the main pathogens of pepper anthracnose in Guizhou. C. kahawae was initially isolated from coffee berries and later used to define Colletotrichum sp. in the same host. Weir et al. [48] divided this species into two subspecies based on their pathogenicity to coffee berries—C. kahawae subsp. kahawae could trigger Coffee Berry Disease (CBD) and C. kahawae subsp. ciggaro could not cause CBD. The former only infected African coffee berries, while the latter had a wide distribution and host range [52,53]. The two subspecies could be distinguished and identified through GS and ApMat. Cabral et al. [52] proposed upgrading the C. kahawae subsp. ciggaro to a species and naming it C. ciggaro. However, this study did not conduct GS and ApMat sequencing, so the two subspecies could not be completely distinguished in the phylogenetic tree. Thus, 10 isolates similar to the two species were temporarily classified as C. kahawae. Their accurate classification will be further studied. There were more strains (nine) isolated in 2021 of C. kahawae, and further research was needed to determine whether this species will rise to become the main pathogen of pepper anthracnose in Guizhou.

The C. boninense and C. karstii isolates belong to the C. boninense species complex. Among them, C. boninense was first isolated from Crinum asiaticum in the Bonin Islands of Japan and later found on diseased and healthy plants such as Orchidaceae, Amaryllidaceae, Bigoniaceae, Podocarpaceae, Proteaceae, Solanaceae, and Theaceae, indicating a wide range of hosts and diverse lifestyles [9]. In 2009, Tozze et al. [54] first reported that C. boninense caused pepper anthracnose. In China, Yang [18] first isolated one strain of this species from diseased pepper fruits in Duyun, Guizhou. In 2013, Diao reported for the first time that C. boninense was isolated and identified on chili peppers in Sichuan, China [55]. In this study, eight strains of the species were isolated and distributed in five cities and prefectures in Guizhou Province, indicating that the fungus might have epidemic risks. C. karstii was collected from Vanda sp. leaves in Luodian County, Guizhou Province, by Yang et al. in 2009 [13], named after the geological characteristics of the collection site—karst. It is the most widely distributed strain in the C. boninense complex, and its hosts include Orchidaceae, Annonaceae, Area, Bombacaceae, Theaceae, and Solanaceae [9]. Yang [18] isolated this strain from Anshun, Duyun, and Tongzi chili peppers in Guizhou Province. The 19 isolates of C. karstii in this study were distributed in four cities and states; among them, there were more strains (11 and 6) in Zunyi and Bijie, indicating a wide distribution range of this pathogen, with northern Guizhou as the main distribution area.

The only species of Colletotrichum with curved conidia isolated in this study was C. truncatum, which is hosted by over 460 plant species and has been reported to harm chili peppers in multiple countries and regions, and this species has been isolated and identified in most chili planting areas in China [15]. In this study, 17 isolates of this species were isolated. From the phylogenetic tree structure, there was a clear grouping between the C. truncatum isolates isolated from the diseased fruits of Bijie (GL 21-30-1, GL 21-31-1, and GL 21-32-2) and other isolates. From the six gene sequences, there were 37 variable sites among all isolates, among which there were 28 variable sites between Bijie isolates and others, including 24 parsimony informative sites and four singleton variable sites. The reason for these site changes and their impact on strain characteristics need further research. Additionally, the relationship analysis between genetic diversity and geographical distribution had yet to be conducted due to the limited number of isolated strains.

C. plurivorum belongs to the C. orchidearum species complex, isolated originally from Sichuan diseased chili fruit by Liu et al. [14] and named C. sichuanensis. It was later recognized as the homonymous species of C. cliviicola in Douanla-Meli et al.’s study [56], while Damm et al.’s study [12] identified them as two different species. The former has a wide host range, and the latter was named after its host Clivia, which GAPDH, TUB2, and HIS3 sequences could distinguish. In the phylogenetic tree of this study, the support rate on the branches of C. plurivorum and C. cliviicola was 98, indicating a close phylogenetic relationship between the two species. From the six gene sequences, there was one mutated base for ITS and CHS-1, two for GAPDH, three for ACT and TUB2, and five mutated bases for HIS3, which was similar to the research conclusion of Damm et al. [12].

Halsted [57] reported on the New Jersey pepper anthracnose disease caused by C. nigrum. In 1896, it was reported that this species was the main causal agent of the American pepper anthracnose disease. Subsequent studies found that the fungus had a wide range of hosts and, like C. coccodes, could cause anthracnose in chili peppers and tomatoes, but that only C. coccodes could cause potato black spots. From the phylogenetic tree, the phylogenetic relationship between C. coccodes and C. nigrum was extremely close, consistent with the research results of Liu et al. [58], with a support rate of 100 on both species’ branches. ITS had no differential bases from the gene sequence perspective, while ACT, CHS-1, GAPDH, TUB2, and HIS3 have 2, 3, 6, 8, and 11 differential bases, respectively. This differed from the report by Jayawardena et al. [3], which reported that the two species could be distinguished with ITS. This might be related to the different gene fragments used. In addition, regarding conidia morphology, C. nigrum had longer conidia and larger L/W values than C. coccodes. The conidia size of the isolates in this study was 9.41–17.45 × 3.14–4.31 μm; it was closer to the C. nigrum described by Liu et al. [58]. Therefore, the isolate was classified as C. nigrum.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Sample Collection, Pathogen Isolation and Purification

During the 2017 and 2021 Guizhou pepper industry censuses, 69 samples of fruits, leaves, and stems of pepper with anthracnose symptoms were collected from 44 locations in Guizhou Province by personnel related to pepper disease research. Using the stereoscopic microscope (Olympus SZX16, Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) and the optical microscope (Olympus CX31, Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan), we observed the scabs and pathogen and took photos to record the samples infected with Colletotrichum spp.

Two methods were used to isolate and purify pathogens. If conidia had already been produced on tissues of pepper in nature, we used a sterile insect needle (2#) to pick up the conidia into sterile water, prepared a suspension of 1.0 × 104 spores/mL of conidia, took 100 μL of the above suspension, uniformly spread with a stainless steel spreader (triangle End 16 mm, 5 mm × 200 mm, Sangon Biotech (Shanghai) Co., Ltd., “Sangon” for short) on water agar medium (WA), and incubated it at 28 °C for 24 h, and then selected the germinated single conidium under the stereoscopic microscope, transferred it to a new PDA medium for cultivation, and selected more than five single spores from each WA medium, selected a well-growing strain for standby. Scabs without conidia were isolated and purified using the tissue separation method [4]. The purified isolates were stored at 4 °C, PDA slants, and −80 °C, 20% glycerol for short-term and long-term storage. The information on isolates is shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

The list of all Colletotrichum spp. collected from pepper in Guizhou based on preliminary identification.

4.2. Morphological and Cultural Characterization

Morphology and cultural characterization followed the method of Diao et al. [15]. A 5 mm mycelial plug was taken from the edge of a vigorously growing colony and placed on a new 2% PDA plate. It was incubated for seven days under natural light at 28 °C, and then the colony’s diameter was measured, and color and texture were observed. After about one month, conidia pile, exudate, and sclerotia production were observed. For strains not prone to producing conidia, we used a culture with WA medium under the same conditions as PDA medium, with a cultivation time of 7–30 days. The shape, color, and size of setae, conidia, sporogenous cells, conidia appressoria, and mycelium appressoria were observed using the Olympus CX31 microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

4.3. Pathogenicity Identification

The acupuncture inoculation method was used for inoculation identification. Healthy red ripe pepper fruits that had not been sprayed with fungicide were selected, disinfected with 75% alcohol, washed with sterile water, and dried. We used a sterilized toothpick to prick a wound at the part near the fruit stalk and the tip, with a diameter of about 1 mm, subjected to piercing the flesh. Each wound was inoculated with 1.0 × 105 spores/mL conidia suspension 5 μL, using sterile water instead of spore suspension as a control treatment (abbreviated as CK). Each strain treated five pepper fruits, which were placed in a PP food preservation box covered with wet filter paper, and cultured at 25 °C for seven days. Then, the incidence of the fruit was observed and recorded. According to Koch’s formula, the pathogens on the diseased fruit were re-separated and purified, and whether the new isolate was the same as the inoculated pathogen was observed.

4.4. DNA Extraction, PCR Amplification, and DNA Sequencing

The aerial hyphae of the isolates cultured on a PDA plate for roughly 10 days were scraped, and DNA extracted using the plant genomic DNA kit (DP305) of Tiangen Biotech (Beijing) Co., Ltd., Beijing, China (from now on referred to as Tiangen). Firstly, the ITS sequence (ITS1/ITS4) [59] was amplified and sequenced, and tentative identification was established based on the NCBI comparison results and morphological assessment. The isolates that were identified as Colletotrichum spp. were further amplified for ACT (ACT-512F/ACT-783R) [60], CHS-1 (CHS-79F/CHS-354R) [60], GADPH (GDFI/GDRI) [61], TUB2 (T1/βt2b) [62,63], and HIS3 (CYLH3F/CYLH3R) [64], and these PCR products were sent to Sangon for sequencing after detecting by electrophoresis on 1.2% agarose gel.

4.5. Phylogenetic Analysis

Using NCBI’s Blast tool to look for sequences with high homology and that belong to comparable pattern strains, the following sequences (Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5) were compared using Cluster W to align. If necessary, Bioedit 7.2.6.1 was used for manual correction, and the corrected sequences were submitted to GenBank to receive accession numbers. The aligned sequences were concatenated by using SequenceMatrix-Windows-1.7.8 in the order ITS-ACT-CHS-1-GADPH-TUB2-HIS3. The concatenated sequences were translated using seaview4.0 format, and a phylogenetic tree was created using the Maximum Likelihood (ML) method in MEGA 6.06 [65]. In total, 1000 repeated bootstrap tests were conducted to establish branch support, which was not displayed when the support rate was less than 50%.

4.6. Genetic Diversity Analysis

In this study, there were a large number of isolates of C. scovillei and C. fructicola, and they had a wide distribution range, so genetic diversity analysis was conducted on the two species respectively. We took the spliced sequences used for phylogenetic tree construction as the analysis object and strains collected from different regions as different populations. The sequences’ base composition, variable sites (including gaps or missing sites in alignment, parsimony informative sites, and singleton variable sites), haplotype diversity, and fixation index (Fst) were analyzed using DNASP v5.0. Population dynamics were analyzed using Tajima’s test and Fu and Li’s test for neutrality testing. The correlation between genetic distance (GD) and geographical distance (GGD) was analyzed using GenAlEx 6.51b2. Additionally, a haplotype network diagram was constructed using Network 10.2.

5. Conclusions

This study found that the pathogen of Guizhou pepper anthracnose disease included 10 species: C. scovillei, C. fructicola, C. karstii, C. truncatum, C. gloeosporioides, C. kahawae, C. boninense, C. nymphaeae, C. plurivorum, and C. nigrum. C. scovillei and C. fructicola had a relatively large number of isolated strains, which might be the primary pathogenic fungi of pepper anthracnose in Guizhou. C. nymphaeae was isolated from Chinese chili peppers for the first time. Genetic diversity analysis has found that there might be population expansion in C. fructicola, which should be taken seriously in disease prevention and control.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.L. and Z.Y.; methodology, B.L., L.L., X.X. and A.Z.; validation, B.L., Y.S. and Z.Y.; formal analysis, B.L., L.L., X.X. and A.Z.; investigation, B.L., L.L., X.X., A.C. and A.Z.; resources, B.L., Y.S., Z.Y. and A.Z.; data curation, B.L., L.L., X.X. and A.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, A.Z.; writing—review and editing, L.L., X.X., B.L., Z.Y. and A.Z.; visualization, B.L., Z.Y., L.L. and A.Z.; supervision, B.L. and Z.Y; project administration, B.L. and Y.S.; funding acquisition, B.L., A.Z. and D.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Guizhou Provincial Science and Technology Projects, grant number Qiankehezhicheng [2019]2260, and Technical System of Pepper Industry in Guizhou Province, grant number GZSLJCYTX-2024.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. These data can be found here: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ (accessed on 1 December 2022).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zou, X.X.; Hu, B.; Xiong, C.; Dai, X.Z.; Liu, F.; Ou, L.J.; Yang, B.Z.; Liu, Z.B.; Suo, H.; Xu, H.; et al. Review and prospects of pepper breeding for the past 60 years in China. Acta Hortic. Sin. 2022, 49, 2099–2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, R.; Van Kan, J.A.L.; Pretorius, Z.A.; Hammond-Kosack, K.E.; Di Pietro, A.; Spanu, P.D.; Rudd, J.J.; Dickman, M.; Kahmann, R.; Ellis, J.; et al. The Top 10 fungal pathogens in molecular plant pathology. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2012, 13, 414–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayawardena, R.S.; Bhunjun, C.S.; Hyde, K.D.; Gentekaki, E.; Itthayakorn, P. Colletotrichum: Lifestyles, biology, morpho-species, species complexes and accepted species. Mycosphere 2021, 12, 519–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Hyde, K.D.; Taylor, P.; Weir, B.S.; Liu, Z.Y. A polyphasic approach for studying Colletotrichum. Fungal Divers. 2009, 39, 183–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, B.C. Colletotrichum: Biology, pathology and control. In The Genus Glomerella and Its Anamorph Colletotrichum; Bailey, J.A., Jeger, M.J., Eds.; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 1992; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Damm, U.; Woudenberg, J.H.C.; Cannon, P.F.; Crous, P.W. Colletotrichum species with curved conidia from herbaceous hosts. Fungal Divers. 2009, 39, 45–87. [Google Scholar]

- Crouch, J.A. Colletotrichum caudatum s.l. is a species complex. IMA Fungus 2014, 5, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damm, U.; Cannon, P.F.; Woudenberg, J.H.; Crous, P.W. The Colletotrichum acutatum species complex. Stud. Mycol. 2012, 73, 37–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damm, U.; Cannon, P.F.; Woudenberg, J.H.; Johnston, P.R.; Weir, B.S.; Tan, Y.P.; Shivas, R.G.; Crous, P.W. The Colletotrichum boninense species complex. Stud. Mycol. 2012, 73, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damm, U.; O’Connell, R.J.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Crous, P.W. The Colletotrichum destructivum species complex—Hemibiotrophic pathogens of forage and field crops. Stud. Mycol. 2014, 79, 49–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damm, U.; Sun, Y.C.; Huang, C.J. Colletotrichum eriobotryae sp. nov. and C. nymphaeae, the anthracnose pathogens of loquat fruit in central Taiwan, and their sensitivity to azoxystrobin. Mycol. Prog. 2020, 19, 367–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damm, U.; Sato, T.; Alizadeh, A.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Crous, P.W. The Colletotrichum dracaenophilum, C. magnum and C. orchidearum species complexes. Stud. Mycol. 2019, 92, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.L.; Liu, Z.Y.; Cai, L.; Hyde, K.D.; Yu, Z.N.; Mckenzie, E.H.C. Colletotrichum anthracnose of Amaryllidaceae. Fungal Divers. 2009, 39, 123–146. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F.; Wang, M.; Damm, U.; Crous, P.W.; Cai, L. Species boundaries in plant pathogenic fungi: A Colletotrichum case study. BMC Evol. Biol. 2016, 16, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, Y.Z.; Zhang, C.; Liu, F.; Wang, W.Z.; Liu, L.; Cai, L.; Liu, X.L. Colletotrichum species causing anthracnose disease of chili in China. Persoonia 2017, 38, 20–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.Y.; Li, X.X.; He, L.F.; Li, B.X.; Mu, W.; Liu, F. Effect of application rate and timing on residual efficacy of pyraclostrobin in the control of pepper anthracnose. Plant Dis. 2020, 104, 958–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Silva, D.D.; Ades, P.K.; Crous, P.W.; Taylor, P.W.J. Colletotrichum species associated with chili anthracnose in Australia. Plant Pathol. 2017, 66, 254–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.L. Multi-Locus Phylogeny of Colletotrichum Species in Guizhou, Yunnan and Guangxi, China; Huazhong Agriculture University: Wuhan, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.N.; Mei, Y.; Wang, W.W.; Wu, Y.C.; Chen, C.J.; Liu, Z.; Shen, F.; Feng, R.C.; Zu, Y.X.; Zheng, J.Q. Evaluation of fruit stage resistance of salt tolerant pepper strains (species) to anthracnose in coastal protected areas of northern Jiangsu. Jiangsu Agric. Sci. 2023, 51, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.Y.; Wu, M.; Wang, X.; Gu, H.P.; Chen, X.; Cui, X.Y. Identification of the causing agents of soybean anthracnose and evaluation of soybean germplasm for resistance to the main anthracnose pathogen. Acta Phytopathol. Sin. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.P.; Xi, S.W.; Zhang, G.F.; Ding, S.W.; He, L.F.; Mu, W.; Liu, F. Inhibitory activity of benzovindiflupyr against fruit rot pathogen Colletotrichum acutatum and its control efficacy to pepper anthracnose. J. Plant Prot. 2023, 50, 830–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Peng, L.; Shao, Z.W.; Fu, C.R.; Gao, J.; Liu, L.P. Biological characteristics and indoor fungicide screening of Colletotrichum brevisporum causing pumpkin anthracnose. Plant Prot. 2021, 47, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.J.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, Y.K.; Feng, J.T.; Chen, Y.F.; Li, K.; Zhang, M.Y.; Qi, D.F.; Zhou, D.B.; Wei, Y.Z.; et al. Biocontrol potential of volatile organic compounds produced by Streptomyces corchorusii CG-G2 to strawberry anthracnose caused by Colletotrichum gloeosporioides. Food Chem. 2023, 437, 137938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.Q.; Fang, S.X.; Liu, D.M.; Zheng, A.Z.; Zhang, Q.C.; Pei, D.L. Screening, identification and antifungal mechanism of bacterial biocontrol strainsagainst hot pepper anthracnose. J. Plant Prot. 2023, 50, 913–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.Y.; He, L.F.; Li, B.X.; Mu, W.; Lin, J.; Liu, F. Sensitivity of Colletotrichum acutatum to six fungicides and reduction in incidence and severity of chili anthracnose using pyraclostrobin. Australas. Plant Pathol. 2017, 46, 521–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.Y.; He, L.F.; Mu, W.; Li, B.X.; Lin, J.; Liu, F. Assessment of the baseline sensitivity and resistance risk of Colletotrichum acutatum to fludioxonil. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2017, 150, 639–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.Y.; Ma, M.T.; Zhang, S.P.; Li, H. Baseline sensitivity and resistance mechanism of Colletotrichum isolates on tea-oil trees of China to tebuconazole. Phytopathology® 2023, 113, 1022–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelain, J.; Lykins, S.; Rosa, P.F.; Soares, A.T.; Dowling, M.E.; Schnabel, G.; May De Mio, L.L. Identification and fungicide sensitivity of Colletotrichum spp. from apple flowers and fruitlets in Brazil. Plant Dis. 2023, 107, 1183–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, P.F.; Bridge, P.D.; Monte, E. Linking the past, present, and future of Colletotrichum systematics. In Colletotrichum: Host Specificity, Pathology, and Host-Pathogen; Prusky, D., Freeman, S., Dickman, M., Eds.; APS Press, Interaction: St Paul, MN, USA, 2000; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Calzada, C.; Tapia-Tussell, R.; Higuera-Ciapara, I.; Huchin-Poot, E.; Martin-Mex, R.; Nexticapan-Garcez, A.; Perez-Brito, D. Characterization of Colletotrichum truncatum from papaya, pepper and physic nut based on phylogeny, morphology and pathogenicity. Plant Pathol. 2018, 67, 821–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Weir, B.S.; Damm, U.; Crous, P.W.; Wang, Y.; Liu, B.; Meng, Z.; Cai, L. Unravelling Colletotrichum species associated with Camellia: Employing ApMat and GS loci to resolve species in the C. gloeosporioides complex. Persoonia Mol. Phylogeny Evol. Fungi 2015, 35, 63–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, G.; Liu, Z.Y.; Liu, F.; Gao, Y.H.; Cai, L. Endophytic Colletotrichum species from Bletilla ochracea (Orchidaceae), with descriptions of seven new speices. Fungal Divers. 2013, 61, 139–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Damm, U.; Cai, L.; Crous, P.W. Species of the Colletotrichum gloeosporioides complex associated with anthracnose diseases of Proteaceae. Fungal Divers. 2013, 61, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damm, U.; Baroncelli, R.; Cai, L.; Kubo, Y.; O’Connell, R.; Weir, B.S.; Yoshino, K.; Cannon, P.F. Colletotrichum: Species, ecology and interactions. IMA Fungus 2010, 1, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nirenberg, H.I.; Feiler, U.; Hagedorn, G. Description of Colletotrichum lupini comb. nov. in modern terms. Mycologia 2002, 94, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Than, P.P.; Jeewon, R.; Hyde, K.D.; Pongsupasamit, S.; Mongkolporn, O.; Taylor, P.W.J. Characterization and pathogenicity of Colletotrichum species associated with anthracnose on chilli (Capsicum spp.) in Thailand. Plant Pathol. 2008, 57, 562–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanto, T.; Uematsu, S.; Tsukamoto, T.; Moriwaki, J.; Yamagishi, N.; Usami, T.; Sato, T. Anthracnose of sweet pepper caused by Colletotrichum scovillei in Japan. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 2013, 80, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, K.; Babai Ahari, A.; Arzanlou, M.; Amini, J.; Pertot, I.; Rota-Stabelli, O. Application of the consolidated species concept to identify the causal agent of strawberry anthracnose in Iran and initial molecular dating of the Colletotrichum acutatum species complex. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2016, 147, 375–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velho, A.C.; Stadnik, M.J.; Casanova, L.; Mondino, P.; Alaniz, S. First Report of Colletotrichum nymphaeae causing apple bitter rot in southern Brazil. Plant Dis. 2014, 98, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascarin, G.M.; Guarín-Molina, J.H.; Arthurs, S.P.; Humber, R.; Alan, R.d.A.D.; Moral, C.G.B.; Delalibera, Í. Seasonal prevalence of the insect pathogenic fungus Colletotrichum nymphaeae in Brazilian citrus groves under different chemical pesticide regimes. Fungal Ecol. 2016, 22, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimayacyac, D.A.; Balendres, M.A. First report of Colletotrichum nymphaeae causing post-harvest anthracnose of tomato in the Philippines. New Dis. Rep. 2022, 46, e12125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.X.; Liu, Y.; Huang, X.Q.; Zhang, L. First report of anthracnose caused by Colletotrichum nymphaeae on loquat fruit in China. Plant Dis. 2018, 102, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, H.M.; Tan, Q.; Fan, F.; Karim, M.M.; Yin, W.X.; Zhu, F.X.; Luo, C.X. Sensitivity of Colletotrichum nymphaeae to six fungicides and characterization of fludioxonil-resistant isolates in China. Plant Dis. 2022, 106, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, X.; Cai, F.; Huang, F.; Chen, W.; Wang, Q. First Report of Colletotrichum nymphaeae causing walnut anthracnose in China. Plant Dis. 2022, 106, 2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.F.; Li, Y.Y.; Li, X.H.; Liu, H.; Huang, J.B.; Zheng, L. First report of tobacco anthracnose caused by Colletotrichum nymphaeae in China. Plant Dis. 2023, 107, 2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.Z.; Li, H. First report of Colletotrichum nymphaeae causing anthracnose on Camellia oleifera in China. Plant Dis. 2020, 104, 1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasehi, A.; Kadir, J.; Rashid, T.S.; Awla, H.K.; Golkhandan, E.; Mahmodi, F. Occurrence of anthracnose fruit rot caused by Colletotrichum nymphaeae on pepper (Capsicum annuum) in Malaysia. Plant Dis. 2016, 100, 1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weir, B.S.; Johnston, P.R.; Damm, U. The Colletotrichum gloeosporioides species complex. Stud. Mycol. 2012, 73, 115–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, N.M.; Zakaria, L. Identification and characterization of Colletotrichum spp. associated with chili anthracnose in peninsular Malaysia. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2018, 151, 961–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoch, A.; Sharma, P.; Sharma, P.N. Identification of Colletotrichum spp. associated with fruit rot of Capsicum annuum in North Western Himalayan region of India using fungal DNA barcode markers. J. Plant Biochem. Biotechnol. 2016, 26, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GCM Global Catalogue of Microorganisms. Available online: https://gcm.wdcm.org/species?taxonid=690256&type=Overview (accessed on 27 June 2023).

- Cabral, A.; Azinheira, H.G.; Talhinhas, P.; Batista, D.; Ramos, A.P.; Silva, M.d.C.; Oliveira, H.; Várzea, V. Pathological, morphological, cytogenomic, biochemical and molecular data support the distinction between Colletotrichum cigarro comb. et stat. nov. and Colletotrichum Kahawae. Plants 2020, 9, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes-Aragón, D.; Silva-Rojas, H.V.; Guarnaccia, V.; Mora-Aguilera, J.A.; Aranda-Ocampo, S.; Bautista-Martínez, N.; Téliz-Ortíz, D. Colletotrichum species causing anthracnose on avocado fruit in Mexico: Current status. Plant Pathol. 2020, 69, 1513–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tozze, H.J.; Massola, N.M.; Câmara, M.P.S.; Gioria, R.; Suzuki, O.; Brunelli, K.R.; Braga, R.S.; Kobori, R.F. First report of Colletotrichum boninense causing anthracnose on pepper in Brazil. Plant Dis. 2009, 93, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, Y.Z.; Fan, J.R.; Wang, Z.W.; Liu, X.L. First report of Colletotrichum boninense causing anthracnose on pepper in China. Plant Dis. 2013, 97, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douanla-Meli, C.; Unger, J.G.; Langer, E. Multi-approach analysis of the diversity in Colletotrichum cliviae sensu lato. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2017, 111, 423–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halsted, B.D. A new anthracnose of peppers. Bull. Torrey Bot. Club 1891, 18, 14–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Cai, L.; Crous, P.W.; Damm, U. Circumscription of the anthracnose pathogens Colletotrichum lindemuthianum and C. nigrum. Mycologia 2013, 105, 844–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, T.J.; Bruns, T.; Lee, S.; Taylor, J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications; Academic Press, Inc.: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1990; Volume 18, pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Carbone, I.; Kohn, L.M. A method for designing primer sets for speciation studies in filamentous ascomycetes. Mycologia 1999, 91, 553–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerber, J.C.; Liu, B.; Correll, J.C.; Johnston, P.R. Characterization of diversity in Colletotrichum acutatum sensu lato by sequence analysis of two gene introns, mtDNA and intron RFLPs, and mating compatibility. Mycologia 2003, 95, 872–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, K.; Cigelnik, E. Two divergent intragenomic rDNA ITS2 types within a monophyletic lineage of the fungusfusariumare nonorthologous. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 1997, 7, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, N.L.; Donaldson, G.C. Development of primer sets designed for use with the PCR to amplify conserved genes from filamentous ascomycetes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1995, 61, 1323–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crous, P.W.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Risède, J.M.; Simoneau, P.; Hywel-Jones, N.L. Calonectria species and their Cylindrocladium anamorphs: Species with sphaeropedunculate vesicles. Stud. Mycol. 2004, 50, 415–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Peterson, D.; Filipski, A.; Kumar, S. MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 2725–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).