Abstract

The development of the digital economy has highlighted the important value of geospatial data across numerous domains, with data trading being a pivotal link in activating this value. The current user base engaging in data trading is diverse, while trading platforms encounter problems such as disorganized data management and oversimplified retrieval methods. These concerns lead to inefficient retrieval for users with minimal domain knowledge. To address these complexities, this study proposes an intelligent retrieval method for geospatial data oriented toward data trading. This method establishes a geospatial data knowledge graph based on a standardized ontology model and innovatively utilizes large language models to assess user requirements in data trading. It effectively addresses the problems of standardized management for multi-source heterogeneous geospatial data and the poor adaptability of traditional retrieval methods to the ambiguous requirements of users lacking professional domain knowledge. Thus, it improves the efficiency and universality of geospatial data trading while guaranteeing the semantic interpretability of retrieval results. Experimental results confirm that the proposed method considerably outperforms traditional keyword-based retrieval methods. It exhibits particularly notable performance enhancements in scenarios with ambiguous requirements. This research not only effectively extends management approaches for geospatial data but also strengthens the inclusivity of data trading. Thus, it provides technical support for maximizing the value of geospatial data.

1. Introduction

The development of the digital economy has made data a core driver propelling the upgrading of digital industries, and the economic value of these data is becoming increasingly prominent. Against this backdrop, data trading, as a core link in activating the value of data, exhibits strong development momentum. Its typical model includes three main entities: data providers, trading platforms, and data consumers. Providers publish data through platforms, while consumers collect and obtain needed data based on particular requirements. In recent years, the extensive application of geospatial data in fields including logistics and transportation, disaster monitoring, and urban planning has verified its high value and trading potential. Consumers engaging in geospatial data trading mainly include three categories: government and public sectors, enterprises, and scientific research and educational institutions. However, the current geospatial data trading is still in its initial development stage. The lack of well-established data management mechanisms and retrieval systems across trading platforms has resulted in struggle among consumers with limited professional knowledge in accurately acquiring target data. This difficulty severely hinders the full realization of geospatial data value.

At present, mainstream platforms for data trading exhibit great shortcomings in managing geospatial data. As the scale of data trading expands, the geospatial data stored in platforms become increasingly chaotic. This condition leads to a significant increase in data management difficulty. Moreover, most platforms currently adopt metadata models that only discretely record basic data attributes. Furthermore, data from different sources encounter issues such as inconsistent standards and ambiguous descriptions in their attribute definitions. On this basis, platforms can only offer traditional retrieval methods based on keyword matching and multi-condition filtering. For example, the China Geospatial Data Cloud Platform (https://www.gscloud.cn/) only provides a multi-condition advanced search function. This feature allows filtering of data based on criteria such as dataset name, spatial coordinates, time range, cloud cover, and rainfall. In data trading, differences in knowledge backgrounds among users and the polysemy of natural language result in semantic heterogeneity of requirements, which means users cannot accurately describe their needs. As a result, platforms ultimately fail to accurately understand and produce relevant retrieval results. These inadequacies severely impact retrieval efficiency. Therefore, an efficient data management and retrieval method for geospatial data trading is necessary to help users lacking professional domain knowledge quickly and accurately acquire target data from massive, multi-source, and heterogeneous geospatial data resources.

Knowledge graphs are an important research direction in artificial intelligence. They organize and store entities, attributes, and relationships between entities in a structured manner. Thus, they provide machines with an interpretable knowledge representation method. At present, this technology is extensively being utilized in various fields, such as search engines [1], intelligent question-answering systems [2], and recommendation systems [3]. It offers crucial technical support for the standardized management, querying, and sharing of data resources. Neumaier pioneered a method for constructing open data knowledge graphs based on semantic technology [4], introducing a standardized description framework, spatiotemporal entity linking mechanisms, and a metadata quality assessment system. The method effectively achieves semantic integration and improved retrieval of multi-source heterogeneous datasets. Färber et al. established an Open Research Knowledge Graph for scientific data resources (DSKG) in 2021 [5]. This graph systematically reflects the core attributes of over 2000 scientific data resources and their relationships with related scientific publications. Lee et al. proposed a method to extract terms from data resource names, attribute descriptions, and classification tags; the method converts them into standard vocabulary, which successfully achieves unified management and intelligent retrieval of Korean government open data [6]. Xiao et al. constructed an ontology model for habitat suitability assessment using knowledge graph technology, achieving the structured integration of multi-source heterogeneous habitat data [7]. Liu et al. proposed a method that integrates the semantic information of heterogeneous geospatial data to construct a geographical entity knowledge graph while also supporting keyword-based retrieval of geospatial information within the knowledge graph [8]. While knowledge graph technology is currently widely utilized for multi-source data management, its main focus has been on cross-domain government open data and open scientific data. In the geospatial data domain, knowledge graphs derived from large-scale, publicly available datasets have not yet been established.

Semantic retrieval is a data or information search technology based on semantic networks. Its core lies in realizing precise mapping between user query intent and data resources through a knowledge-driven semantic matching mechanism. This technology deeply parses the semantic meaning of search queries and conducts semantic correlation analysis based on domain knowledge bases; as a result, it can identify and return the most semantically relevant results within various data storage systems [9]. In the field of geospatial data retrieval (GDR), Miao et al. further developed an ontology-based semantic retrieval model; this model innovatively proposes a measurement method integrating spatiotemporal similarity and content similarity [10]. By analyzing the semantic similarity between the essential characteristic attributes (space, time, and theme) of data and the search keywords, this model achieves more accurate semantic retrieval. Li et al. proposed a two-layer ranking algorithm (LSATTR) based on latent semantic analysis and revised cosine similarity [11]. This method offers more flexibility than traditional thesaurus-based semantic expansion. However, it involves recalculating the matrix with data updates. The matrix dimensionality also increases with data volume, which demands higher computational performance. Ning et al. proposed an autonomous GIS agent framework driven by a large language model, capable of cross-platform geospatial data crawling through program generation, execution, and debugging [12]. This framework imposes certain requirements on user expertise. Wiegand et al. proposed a task-driven and semantic web-based method for GDR [13]. By formalizing the relationship between task types and required data, they established a task-oriented ontology model supporting users in conducting semantic retrieval based on task requirements and spatial scope. However, this method only achieves a binary matching judgment for retrieval results; it lacks a screening mechanism for the results. Furthermore, Hou et al. and Sun et al. explored semantic association retrieval for geospatial data from the dimensions of time and data source, respectively; however, these studies were limited to assessing single feature dimensions [14,15]. They failed to achieve integrated retrieval across multiple dimensions, which causes difficulty in handling complex semantic situations. Hao et al. designed a knowledge graph and large language model-based geospatial data question-answering (GDQA) system [16]. The system enables users to acquire geospatial information from data through natural language interaction and evaluates results based on reasoning paths within the knowledge graph.

Overall, the clear professional boundaries and unique semantic characteristics of geospatial data have resulted in a lack of knowledge graphs derived from large-scale datasets and applicable construction methods. With regard to data retrieval, technologies including ontologies and latent semantic analysis have been integrated. However, these methods still depend on predefined thesauri for semantic expansion. Their retrieval performance is constrained by the scale and quality of the thesaurus. They often focus on single feature dimensions. Therefore, they lack multi-dimensional analysis capabilities, which make them unsuitable for complex requirement semantics confronted in data trading scenarios. As a result, these methods are inappropriate for users lacking professional domain knowledge in data trading.

To address the abovementioned problems, this study proposes an intelligent retrieval method for geospatial data oriented toward data trading. It involves constructing a standardized ontology model centered on the multi-dimensional characteristic attributes of geospatial data. The model is used to extract knowledge from multi-source data and form a knowledge graph specific to a professional domain. By innovatively utilizing large language models (LLMs) to assess user requirements, it conducts multi-hop reasoning to extend potential requirements before mapping them to entities in the knowledge graph. Simultaneously, an evaluation model for trading value is designed to screen retrieval results. This method effectively solves the problems of standardized management of multi-source heterogeneous geospatial data and the applicability issues of traditional retrieval methods. Its performance enhancement is more pronounced in scenarios with vague user requirements. It enables data trading among users lacking professional domain knowledge to efficiently and accurately obtain target data resources. This feature reduces user retrieval and trial-and-error costs, which ultimately enhances the efficiency and universality of geospatial data trading.

The remaining parts of the paper are organized as follows. Section 2 presents the knowledge graph construction and intelligent retrieval method for geospatial data. Section 3 validates the method through experiments and discusses the implementation of a prototype system. Section 4 reviews the comparison between this method and other retrieval methods and provides discussion. Section 5 elaborates the conclusion of this study and future prospects.

2. Materials and Methods

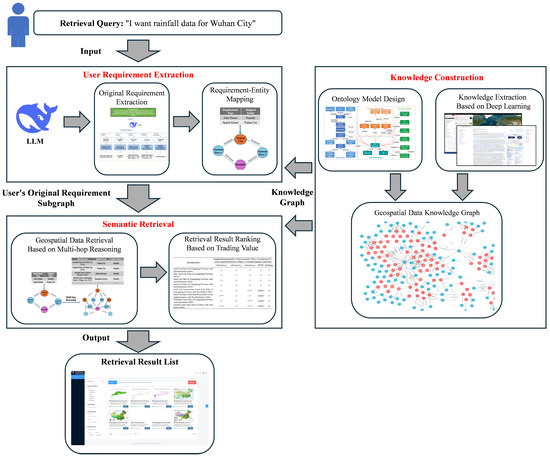

The objective of this study is to address the challenges of data management in geospatial data trading and the inefficiencies faced by users lacking professional domain knowledge. To this end, we propose an intelligent retrieval method for geospatial data within the data trading context. This method analyzes user requirements using a large language model and performs data matching within a geospatial data knowledge graph to output a candidate data list. The specific methodology is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Methodology framework.

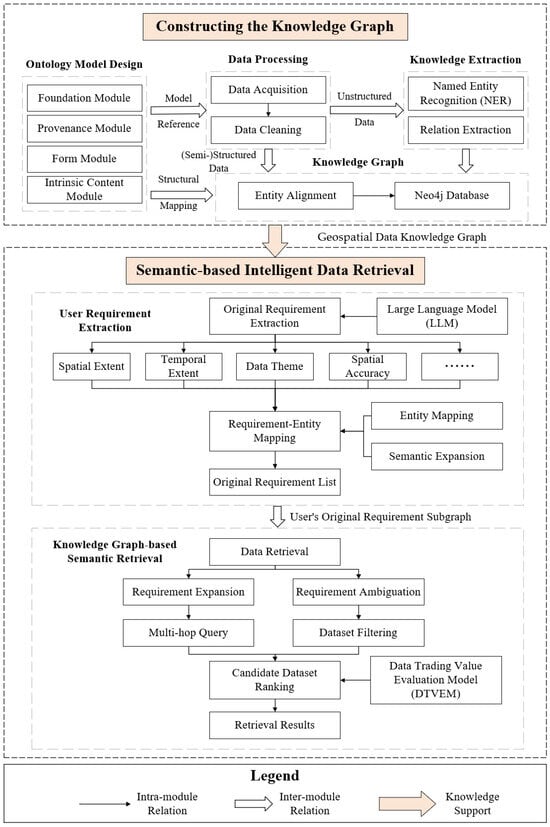

As depicted in Figure 2, the workflow of this method primarily consists of two parts: knowledge graph construction and intelligent data retrieval. First, within the context of geospatial data trading, a standardized ontology model is constructed, and based on this, a domain knowledge base is built to achieve a standardized representation of the multi-dimensional characteristic attributes of geospatial data and to establish a semantic association network among data resources. Subsequently, an LLM is used to perform standardized extraction of user requirements. Then, through entity mapping and the application of semantic expansion algorithms, the original user requirements are mapped to entities within the knowledge graph. Next, a knowledge inference method based on multi-hop path queries is employed to supplement related requirements. Finally, the proposed Data Trading Value Evaluation (DTVE) model is used to comprehensively rank the retrieval results, ultimately returning to the user a data retrieval result list sorted in descending order of trading value. The following sections will provide detailed descriptions of the data and research methods.

Figure 2.

Workflow.

2.1. Geospatial Data Source Analysis

The data for establishing the geospatial data knowledge graph in this study were primarily sourced from industry websites, domain-specific materials, and online encyclopedias. The raw data were acquired through a combination of automated crawling and manual integration. These data were uniformly processed using Python 3.13 scripts. They were then stored in a PostgreSQL database.

2.1.1. Industry Websites

This study mainly acquired metadata information of data resources from two industry websites: the National Earth System Science Data Center (https://www.geodata.cn/main (accessed on 20 March 2025)) and OSCAR (https://space.oscar.wmo.int/satellites (accessed on 1 April 2025)). The former is China’s largest data sharing platform for Earth system science, while the latter is a vital international platform for publishing satellite and meteorological geospatial data. These websites contain a vast amount of multi-source, heterogeneous geospatial data resources, which are mostly organized in structured or semi-structured formats. Data acquisition and processing involved a combination of web crawling and manual curation, and Python scripts were used to standardize the crawled results [17].

2.1.2. Domain-Specific Materials

The domain-specific materials involved in this study mainly comprised the Geoscience Thesaurus and various standards and specifications from related fields. The Geoscience Thesaurus, which was compiled by experts in the field of geography, contains a large number of geographical professional terms in plain text format. It covers terms from China’s administrative regions and physical geographical entities. It also employs the Simple Knowledge Organization System to represent relationships and organize content for various entities.

2.1.3. Online Encyclopedias

Online encyclopedia websites, including Baidu Encyclopedia, are publicly available data collections. They cover knowledge across all domains and can be used to supplement domain knowledge. Spatial extent entities can be established using the metadata (spatial locations) obtained from the National Earth System Science Data Center and the thesaurus terms for administrative regions and physical geographical entities acquired from the Geoscience Thesaurus. However, these data lack detailed descriptions of the geographical locations of the entities. As a result, extracting topological relationships between their spatial extents becomes impossible. Therefore, this study utilized Baidu Encyclopedia as a supplementary data source for the knowledge graph to obtain geographical location descriptions for spatial extent entities.

2.2. Knowledge Graph Construction for Data Trading

To address the challenges of highly heterogeneous data and management difficulties within data trading platforms, this study established a geospatial data knowledge graph based on the characteristics of geospatial data, including multi-source origins, heterogeneity, and a lack of standardization. Compared with conventional knowledge structures, this knowledge graph allows the standardized representation and association of geospatial data attributes; it provides a data foundation for subsequent semantic retrieval [18,19].

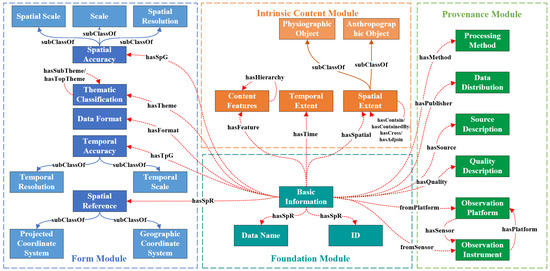

Our research indicates that existing geospatial data trading platforms primarily offer core search and filtering criteria focused on several key dimensions. Users need to locate data content based on data themes and spatial/temporal extent; they must filter available data according to parameters such as data format and spatial resolution; furthermore, they place significant emphasis on information regarding data sources and observation platforms to assess data reliability and practical value. Consequently, to address these user concerns throughout the trading process, we have designed an ontology model for the knowledge graph that comprises a Foundation Module, an Intrinsic Content Module, a Form Module, and a Provenance Module (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Ontology model design.

- The Foundation Module contains the Basic Information class, which is utilized to represent the fundamental information of a data resource, including its name and ID.

- The Intrinsic Content Module comprises the Temporal Extent class, the Spatial Extent class, and the Content Feature class. These classes express the characteristic information of the data resource across the temporal, spatial, and thematic content dimensions. The Temporal Extent class is denoted as the valid time interval of the geographical phenomenon or event recorded by the data resource. The Spatial Extent class is described as the geographical distribution area of the data resource and can be subdivided into Physical Geographical Object classes (e.g., Tibetan Plateau and East Lake) and Human Geographical Object classes (e.g., Wuhan City and Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macao Greater Bay Area). A single data resource can be associated with one or multiple spatial extents. The Content Feature class characterizes the thematic content information recorded by the data.

- The Form Module consists of the Topic Category class, Data Format class, Spatial Reference class, Spatial Accuracy class, and Temporal Accuracy class. In this study, temporal accuracy and spatial accuracy are categorized as follows: Temporal Resolution (e.g., yearly and daily), Temporal Scale (e.g., annual average and daily average), Spatial Resolution, Scale, and Spatial Scale (e.g., provincial level and city level). Spatial Reference is divided into the Geographic Coordinate System and the Projected Coordinate System.

- The Provenance Module includes the Data Publisher class, Processing Method class, Source Description class, Quality Description class, Observation Platform class, and Observation Instrument class. This module describes information related to the production process of the data resource. Users often heavily consider this information when choosing data; for instance, they may prefer authoritative data published by national units when choosing administrative division data, or seek data resources processed from raw data, such as local statistical yearbooks when searching for economic development data related to a specific location.

Apart from data properties, object properties (i.e., “relationship properties”) also exist between some ontology classes. These object properties are used to establish connections between different entities after instantiation. This study denotes the hierarchical relationship between Content Features as the hyponymy relation. By semantically linking different Content Feature entities through hyponymy relations, data resources containing different Content Features become interconnected.

The knowledge extraction phase in the construction of this study’s knowledge graph primarily consisted of three components:

- (1)

- For structured and semi-structured metadata in geospatial data, which typically include attributes such as Spatial Resolution, Data Source, and Data Theme, this study employed rule-based mapping and direct transformation methods to match metadata fields with corresponding relations in the ontology model, converting them into entities within the knowledge graph.

- (2)

- For unstructured metadata in geospatial data, where certain attributes are embedded in unstructured textual content such as data abstracts and descriptions, this study utilized a combined BERT + GlobalPointer model to perform Named Entity Recognition (NER) on the unstructured text present in the metadata. The BERT model encoded the original text, and the GlobalPointer network decoded it, ultimately outputting different types of entities identified in the text to supplement the knowledge graph.

- (3)

- Following entity recognition, the next step comprised establishing spatial relationships between the identified entities. This study employed unstructured geographical description texts, which were primarily sourced from industry websites, domain-specific materials, and online encyclopedias. These texts served as the main corpus for extracting spatial topological relations in the form of Subject–Predicate–Object (SPO) triplets [20].

A common challenge in geospatial data is the presence of different surface forms (names/expressions) referring to the same real-world entity. To address this issue, a synonym dictionary was established based on domain-specific materials. The FastText model was then leveraged to ascertain whether different expressions referred to the same entity, which completed the entity alignment process [21].

Considering the potential performance overhead and operational complexity associated with subsequent multi-hop reasoning and entity modifications, the Neo4j graph database was chosen for knowledge storage due to its inherent capabilities to handle graphs.

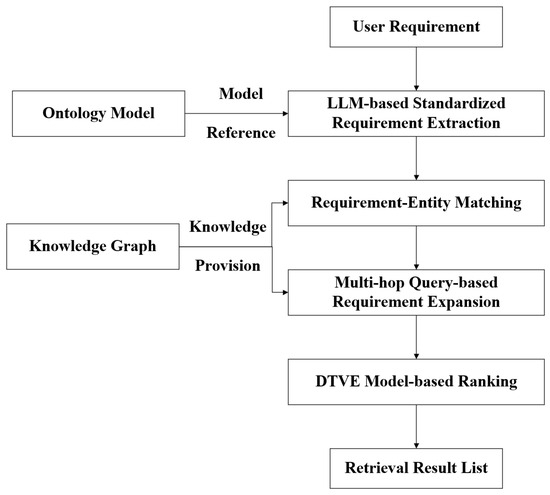

2.3. Intelligent Retrieval of Geospatial Data Based on Trading Value

The intelligent retrieval method proposed in this study utilizes an LLM to conduct semantic understanding of the input retrieval requirements defined by the user. These requirements are then mapped to entities within the knowledge graph and undergo requirement expansion. Finally, the retrieved results are ranked using the DTVE model, which produces a sorted retrieval result list. The overall framework is depicted in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Flowchart of the intelligent retrieval method.

2.3.1. User Requirement Extraction Based on an LLM

In data trading, users possess varying levels of cognition regarding the content and structure of geospatial data. Users with a high level of cognition can accurately describe the various characteristic attributes of the required geospatial data. By contrast, users with a lower level of cognition can only offer vague descriptions of certain features of the needed data. These ambiguous descriptions are difficult to fully match with the geospatial metadata stored in the knowledge graph, which leads to a decrease in retrieval accuracy [22].

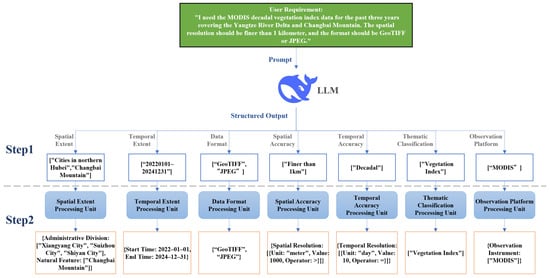

To address the abovementioned issue, this study proposes a user requirement extraction method based on an LLM. This method bridges the gap in retrieval efficiency between users with different levels of data cognition [23]. As illustrated in Figure 5, this method comprises two parts.

Figure 5.

Analysis process of the LLM.

This study used the DeepSeek-V3 model and a few-shot prompting design method to initially decompose user requirements [24]. The Chinese semantic understanding capability of this model ranks among the leading contemporary LLMs, which enables it to effectively comprehend and follow prompts to produce structured outputs [25]. The few-shot prompting method involves embedding multiple input–output demonstration cases within the prompt to enhance the understanding of the task by the model while effectively constraining its output format. The user requirement text is first input into the LLM, which is then guided to perform a preliminary decomposition and extraction of the requirements. Ultimately, a structured list of extracted results for seven types of requirement aspects, namely, Spatial Extent, Temporal Extent, Data Format, Spatial Accuracy, Temporal Accuracy, Data Theme, and Observation System, is generated [26]. Table 1 displays the prompt example for the first stage of the LLM.

Table 1.

Prompt template for user requirement extraction (Step 1).

When confronted with complex semantic reasoning problems, simple prompts are often insufficient to effectively guide the LLM in producing accurate outputs. Therefore, this study adopted Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompt engineering for improved prompting [27]. This method explicitly offers intermediate reasoning steps from input to output within the demonstration cases. It allows the model to simulate human-like logical thinking, which encourages it to “think” before producing an answer. This feature strengthens the capability of the LLM to handle such problems. Table 2 shows the CoT prompt template for the “Temporal Extent” processing unit.

Table 2.

CoT prompt template for the “Temporal Extent” requirement processing unit.

2.3.2. Requirement–Entity Mapping in the Knowledge Graph

Following the extraction of user requirements, “requirement–entity” mapping with the knowledge graph is conducted [28]. However, user requirement points may not obtain exact matches with entities in the knowledge graph. Therefore, this study conducted semantic expansion based on the initial “requirement–entity” mapping. The specific steps are described as follows:

(1) Entity Mapping

Entity mapping refers to the process of mapping the extracted requirement points to entities of the corresponding type within the knowledge graph, which produces a sequence of entities. For instance, after extraction by the LLM, if the original requirement defined by a user contains a Spatial Extent requirement point “Wuhan City,” and an entity “Wuhan City” exists in the graph, then this requirement point can be directly mapped to that entity.

(2) Semantic Expansion

If a requirement point is not found in the graph, then the method uses semantic expansion to search for similar entities. This process replaces the original requirement point with the expanded ones. Semantic expansion maps requirement points that cannot be directly matched to entities via entity mapping to semantically similar entities through semantic similarity calculation. The formula for computing semantic similarity is given as follows:

Here, represents a requirement point, and signifies an entity in the knowledge graph. denotes the text similarity calculated based on the edit distance between the requirement point and the entity [29]. represents the maximum semantic cosine similarity between the requirement point and the entity , which is equivalent to the cosine similarity of their vector representations. is a weight parameter balancing the contribution of the two calculated results.

The formula for calculating is given as follows:

Here, represents the length (number of characters) of the longer text string between the requirement point and the entity . denotes the Levenshtein edit distance between them [30]. The Levenshtein edit distance refers to the minimum number of single-character edits (insertions, deletions, or substitutions) needed to change one string into the other. For instance, the Levenshtein edit distance between the string “” and the string “” is 1, which is achieved by a single character insertion operation at the end.

For a given requirement point , the method iterates over all entities in the knowledge graph that share the same type as . If exceeds a predefined threshold, then and n are considered semantically similar; otherwise, they are deemed semantically unrelated. Let represent the list of entities semantically similar to .

If , then the top two entities with the highest similarity scores that exceed the threshold are selected as the expansion entities for .

If , then no semantically similar entity exists in the knowledge graph for , and is removed from the original requirement list.

When selecting the threshold, if it is set too high, it becomes overly strict, leading to the omission of semantically similar and legitimate expansion entities. The method would then tend to return only exact matches. When faced with vague or non-standard user expressions, it would likely fail to retrieve the data users actually need, resulting in retrieval failure. Conversely, if the threshold is set too low, it becomes overly lenient, allowing entities with weak semantic associations to be erroneously included as expansion entities. This increases noise in downstream retrieval and returns data irrelevant to the user’s needs, interfering with user judgment and selection.

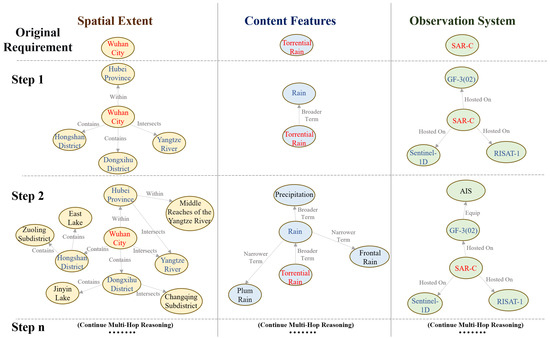

2.3.3. GDR Based on Multi-Hop Reasoning

In the process discussed above, some requirement points map to entities with rich semantic relationships. Using only these entities as constraints for data retrieval may result in the loss of semantic context. Therefore, it potentially fails to guarantee that the retrieval results fully cover the needs of the user, which leads to low recall. Therefore, this study utilized semantic reasoning based on the knowledge graph specifically for three types of requirement points: Spatial Extent, Data Theme, and Observation System. Multi-hop queries were conducted to find entities associated with the original requirements within the graph. This process expanded the requirements and formed a set of associated requirements.

Considering that breadth-first traversal facilitates tracking the path distance between associated requirements and the original requirement within the graph, this study adopted a breadth-first search strategy to perform the multi-hop queries, as depicted in Figure 6 [31]. As the number of search steps increased, the relevance of the discovered entities to the original requirement gradually decreased. “Spatial Extent” requirements correspond to Spatial Extent entities. The queried paths included relationships such as “contains,” “within,” “adjacent to,” and “intersects.” “Data Theme” requirements correspond to Thematic Classification and Content Features entities. The queried paths for Thematic Classification entities comprised “broader theme” and “narrower theme” relationships, while those for Content Features entities consisted of “broader term” and “narrower term” relationships. Queried paths for “Observation Platform” and “Observation Instrument” entities included the “hosted on” and “equipped with” relationships.

Figure 6.

Process of requirement expansion.

During multi-hop reasoning, it is necessary to set a maximum hop depth according to the actual situation. If a relatively large maximum hop depth is set, it will lead to a significant increase in the final retrieval results, most of which will be datasets with lower trading value scores. In practical applications, users are highly unlikely to pay attention to results ranked so far back; this would instead dilute the overall quality of the result set and degrade the user experience. If the maximum hop depth is set too small, there is a risk of losing the user’s potential requirements.

The GDR method based on knowledge graph multi-hop querying comprises the following steps:

- (1)

- Each requirement point in the original requirement lists for “Spatial Extent,” “Data Theme,” and “Observation System” is mapped to corresponding entities within the geospatial data knowledge graph.

- (2)

- A multi-hop query is conducted on the knowledge graph. The process starts from the entities corresponding to the original requirements and traverses along specified relationship types. All entities and relationships discovered through this query are integrated to form the associated requirements, from which a subgraph of the knowledge graph is produced.

- (3)

- Based on this subgraph, the “Basic Information” entities and all their directly connected entities within the geospatial data knowledge graph are queried. This step aims to acquire the sets of geospatial data that correspond to the expanded “Spatial Extent,” “Data Theme,” and “Observation System” requirements.

- (4)

- The resulting geospatial datasets subsequently undergo flexible filtering based on the “Data Format,” “Temporal Extent,” “Spatial Accuracy,” and “Temporal Accuracy” requirements. This process improves the retrieval coverage, which yields a collection of geospatial data that may satisfy the various requirements defined by users.

2.3.4. Retrieval Result Ranking Based on Trading Value

In data trading, the core of trading value relies on the degree to which user requirements are satisfied—data that closely match the needs of the user have higher trading value [32]. However, given that the retrieval process uses knowledge graph multi-hop queries to produce associated requirements and flexible condition filtering, the scope of the original requirement-based retrieval is expanded to some extent. To allow users to efficiently match with the data they need most and improve data trading value, this study proposes a DTVE model for ranking the GDR results by value; this model is based on the seven defined requirement points for geospatial data from the requirement extraction phase [33]. This model calculates relevance scores across eight dimensions: Spatial Extent, Temporal Extent, Data Format, Spatial Accuracy, Temporal Accuracy, Observation System, Thematic Classification, and Content Features. Through this process, it implements DTVE. The final retrieval results are acquired by sorting in descending order of trading value. The specific expression is presented in Formula (3).

In the formula, the value range for each metric is [0, 1]. If the original requirement defined by a user excludes a specific metric, then its value defaults to 1. The detailed calculation methods for each relevance evaluation metric in the model are given as follows:

(1) Spatial Extent Relevance

This relevance is calculated based on the distance between the “Spatial Extent” entity in the knowledge graph corresponding to the geospatial data and the “Spatial Extent” entity corresponding to the requirement defined by the user, as presented in Formula 4.

The spatial extent relevance, , is computed using an exponential decay function, which means the relevance decays at an accelerating rate as the distance between entities increases [34]. Here, represents the relevance decay coefficient, which is set by default to 0.5; a larger causes relevance to decrease faster. denotes the distance between the “Spatial Extent” entity associated with the geospatial data being evaluated and the “Spatial Extent” entity associated with the requirement defined by the user. Its specific calculation is depicted in Formula (5).

Here, is the number of relationship edges between entity and entity .

(2) Temporal Extent Relevance

This relevance is calculated based on the overlap between the temporal extent of the geospatial data, , and the temporal extent of the requirement of the user, , as illustrated in Formula (6).

Here, is the overlapping portion of the data temporal extent and the requirement temporal extent. denotes the duration of this overlap, while and refer to the lengths of the data temporal extent and the requirement temporal extent, respectively. This formula considers the degree to which the data temporal extent covers the requirement temporal extent and the redundancy of the data temporal extent itself.

(3) Data Format Relevance

This relevance is obtained by matching the data format of the geospatial data, , against the set of user-required data formats, , as presented in Formula (7).

(4) Spatial Accuracy Relevance

This relevance is comprehensively calculated from the spatial resolution relevance , the spatial scale relevance , and the spatial measurement scale relevance , as depicted in Formula (8).

Here, . is 0 if the spatial accuracy requirement defined by the user excludes spatial resolution, is 0 if it does not include spatial scale, and is 0 if it excludes spatial measurement scale. The calculation for is presented in Formula (9), that for in Formula (10), and that for in Formula (11).

Here, is the spatial resolution value of the geospatial data, is the range of spatial resolution values required by the user, and is the numerical gap between and . If falls within , then this value is 0. This method accounts for two cases: if is within the range, then is 1; otherwise, gradually decreases toward 0 as the numerical gap increases.

Here, is the spatial scale value of the geospatial data, is the range of spatial scale values required by the user, and is the numerical gap between and . If falls within , then this value is 0.

Here, is the spatial measurement scale of the geospatial data, and is the set of spatial measurement scales required by the user. If matches one of the items in , then is 1; otherwise, is 0.

(5) Temporal Accuracy Relevance

This relevance is comprehensively calculated from the temporal resolution relevance () and the temporal measurement scale relevance (), as presented in Formula (12).

Here, . is 0 if the temporal accuracy requirement defined by the user excludes temporal resolution, and is 0 if it does not include the temporal measurement scale. The calculation for is depicted in Formula (13), and that for in Formula (14).

Here, is the temporal resolution value of the geospatial data, and is the range of temporal resolution values required by the user. This calculation method is the same as that for spatial resolution relevance ().

Here, is the temporal measurement scale of the geospatial data, and is the set of temporal measurement scales required by the user. This calculation method is the same as that for spatial measurement scale relevance ().

(6) Observation System Relevance, Thematic Classification Relevance, Content Features Relevance

The relevance scores for Observation System, Thematic Classification, and Content Features are all computed using the exponential decay method based on the distance between the requirement entities of the user and the corresponding entities in the geospatial data knowledge graph, as illustrated in Formula (15).

, , and represent the Observation System relevance, Thematic Classification relevance, and Content Features relevance, respectively. Here, denotes the relevance decay coefficient, which is set by default to 0.5. , , and refer to the distances in the knowledge graph between the evaluated “Observation Platform,” “Thematic Classification,” and “Content Features” entities and the corresponding user requirement entities, respectively. The specific calculation is presented in Formulas (16)–(18).

Here, is the number of relationship edges between entity and entity .

3. Results

3.1. Data Preprocessing

The experiment was mainly divided into two stages: the construction of the geospatial data knowledge graph and GDR. During the knowledge graph construction phase, the raw geospatial data were sourced from the National Earth System Science Data Center, online encyclopedia websites, and domain-specific materials, such as the Geoscience Thesaurus. Following data governance, this process led to the creation of three datasets and two corpora: the Geospatial Dataset, the Geoscientific Terminology Dataset, the Observation System Dataset, the Implicit Metadata Entity Recognition Corpus, and the Spatial Relation Extraction Corpus [35].

The Geospatial Dataset primarily consists of metadata information for relevant data within the field of Earth science, which were collated from the National Earth System Science Data Center. The dataset contains a total of 5000 records. The metadata items included in each record and their corresponding ontology classes or data properties in the knowledge graph are depicted in Table 3.

Table 3.

Mapping rules for metadata items in geospatial datasets.

The Geoscientific Terminology Dataset contains standard thesaurus terms used to describe Content Features, Physiographic Objects, and Anthropographic objects, along with their broader–narrower relationships. It was compiled from the Geoscience Thesaurus and various relevant domain standards and specifications, and it is used to construct knowledge graph entities and a synonym dictionary. This dataset contains a total of 9602 thesaurus terms, with 6248 terms for the Content Features ontology, 637 terms for Physiographic Objects, and 2717 terms for Anthropographic Objects. A dataset example is presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Example of a Geoscientific Terminology Dataset.

The Observation System Dataset mainly contains the names of currently operational satellites and the sensors they carry. It was utilized to establish the Observation Platform and Observation Instrument entities within the knowledge graph. The dataset was organized from the OSCAR website, with an example presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Example of an Observation System Dataset.

The Implicit Metadata Entity Recognition Corpus was mainly created by annotating the unstructured text values of metadata items, including “Data Abstract” and “Data Source,” within the Geospatial Dataset. This corpus is typically used to extract ontology instances, including spatial resolution and temporal resolution, which completes the metadata information for geospatial data. In this study, 12,724 text instances were chosen from the Geospatial Dataset for annotation. The annotation work was conducted by multiple annotators using the labeling tools provided by the Alibaba Cloud NLP Self-Learning Platform; the process involved multiple rounds of annotation and verification [36].

The Spatial Relation Extraction Corpus is typically used to extract spatial topological relationships between physiographic object entities and anthropographic object entities. In this study, the corpus was collected from Baidu Encyclopedia using the physiographic object and anthropographic object thesaurus terms from the Geoscientific Terminology Dataset as keywords to crawl relevant web content. The corpus contains a total of 8641 text instances. The annotation work was also completed via the NLP Self-Learning Platform.

3.2. Construction of the Geospatial Data Knowledge Graph

The experiment employed BERT+GlobalPointer for NER and utilized GPLinker for relation extraction between entities. Both models were trained using five-fold cross-validation [37]. For both corpora, 80% of the corpus instances were utilized for the iterative splits in cross-validation, while the remaining 20% were held out as a test set. The training parameters for both models are presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Configuration of model parameters.

The NER and relation extraction tasks involve multiple types of entities and multiple types of spatial relations, and the distribution of different entity and relation types in the corpus is imbalanced. Therefore, the performance of the model was evaluated using three metrics: Macro Precision (), Macro Recall (), and Macro F (). Compared with the commonly used micro-averaged F1 score, Macro F1 offers a better indication of the performance of a model in recognizing infrequent entities or relations [38]. If the precision of the model for a single category of entity or relation is and its recall is , then

The final training performance evaluation for the two models is depicted in Table 7. The performance of the entity extraction model is generally lower than that of the relation extraction model. Analysis suggests the reason is the relatively small amount of annotated data available for the current NER task, along with the large number of entity types to be recognized and the low frequency of some entity types in the corpus. These factors prevent the model from adequately learning the features of these entity types, which leads to reduced performance. Nevertheless, the extraction effectiveness of both models meets the research requirements, which demonstrates the viability of the deep learning-based entity and relation extraction methods for domain knowledge extraction.

Table 7.

Evaluation of model training performance.

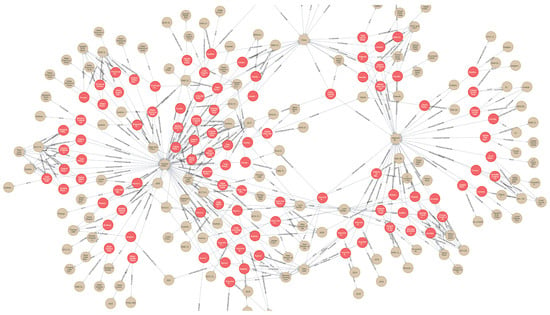

Upon completion of the knowledge extraction, the datasets underwent entity alignment and were stored in a Neo4j graph database. Finally, the construction of the geospatial data knowledge graph was completed. The entities and relations within the knowledge graph were counted according to the module divisions defined in the ontology model, as shown in Table 8. The knowledge graph comprises a total of 31,671 entities and 80,538 relations. Here, the number of relations is counted based on the tail entity in the SPO triple. The number of relations for the Foundation Module is 0, which is because the entities in the Foundation Module typically appear as the head entity in relations. Figure 7 presents a local sample of the knowledge graph, which clearly illustrates the associative relationships formed between different data resources through characteristic attributes, including Spatial Extent, Spatial Accuracy, and Thematic Classification.

Table 8.

Entity and relation statistics within the geospatial data knowledge graph.

Figure 7.

Schematic of the geospatial data knowledge graph.

3.3. Geospatial Data Retrieval

Following the construction of the geospatial data knowledge graph, this study validated the effectiveness of the proposed intelligent retrieval method by comparing its performance against those of retrieval methods used by existing data trading platforms or data sharing websites. For this purpose, a prototype system named GDR was constructed to implement the data retrieval methods. Given that many domestic data trading platforms and data sharing websites currently use keyword matching retrieval that combines full- and segmented-word matching, this study implemented this method within the GDR system for performance comparison with the proposed intelligent retrieval method.

Based on the seven requirement points proposed in the study, this study designed ten retrieval queries, with some of the requirement points intentionally made ambiguous. Specifically, five queries were designed with precise conditions and five with ambiguous conditions, with each query covering 3–4 requirement points to simulate usage by users lacking professional domain knowledge on data trading platforms. Concurrently, this study conducted extensive online research to collect commonly used retrieval needs from users across different domains of geospatial data trading platforms. Experimental results show that 14 out of the total queries were able to successfully retrieve results in the GTDR system. In summary, this experiment tested a total of 24 retrieval queries, as detailed in Table 9.

Table 9.

Design of each retrieval query.

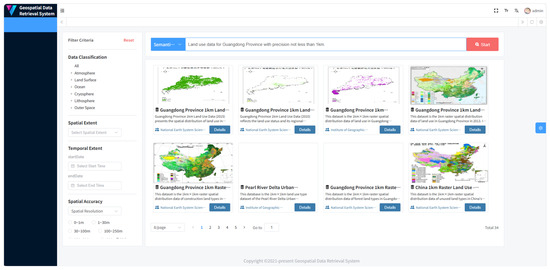

Using Query 1 as an example, the two retrieval modes of the GDR system were compared. Figure 8 depicts the detailed results of retrieving data for Query 1 using the semantic retrieval mode in the GDR system. No data resources exhibiting obvious requirement mismatches are detected. The scores and ranking results for the eight data resources shown were acquired by consulting backend records, as displayed in Table 10. The data resources ranked 1st, 6th, and 8th—“Land Use Data of Guangdong Province with 1 km Resolution (2015),” “Land Use Data of the Pearl River Delta Urban Agglomeration with 1 km Resolution (2010),” and “Unused Land Type Data of China’s 1 km Raster Land Use (2000)”—were chosen for further inspection of the knowledge graph database. Data Resource 1 is fully aligned with all entities from the original requirements defined by the user. The Spatial Extent entity associated with Data Resource 6 has a path distance of 1 to the corresponding entity in the original requirements defined by the user. Furthermore, the Content Features entity and the Spatial Extent entity associated with Data Resource 8 exhibit a path distance of 1 to their respective counterpart entities in the original requirements defined by the user. Therefore, the ranking order of the three data resources is consistent with the sorting results depicted in Table 10. Therefore, the results retrieved by the semantic retrieval mode possess a certain degree of rationality and semantic interpretability.

Figure 8.

Retrieval results of Query 1 (Intelligent Retrieval Mode).

Table 10.

Retrieval result ranking of Intelligent Retrieval Mode.

Figure 9 presents the detailed results of retrieving data for Query 1 (“Land use data for Guangdong Province with precision not less than 1 km”) using the keyword retrieval mode in the GDR system. An incorrect dataset resource, “1:1 Million Land Use Dataset of Guangdong Province (2005),” appears in the second position. From the perspective of user requirement, its spatial accuracy metric (scale) does not conform to the required spatial resolution defined by the user, and therefore, it should not appear in the retrieval results. The spatial extents of the dataset resources ranked sixth and eighth also do not match “Guangdong Province” in the query. The keyword retrieval method based on full-word matching primarily ranks results based on the total frequency of the query keywords appearing across various feature descriptions of the dataset resources. During retrieval, the system backend conducts word segmentation and stop-word removal. These processes retain five keywords: “Guangdong Province,” “not less than,” “1 km,” “precision,” and “land use data.” The basis for result ranking can be summarized by the statistical data in Table 11, where the occurrence counts of all keywords were manually validated by inspecting the detail pages of the dataset resources.

Figure 9.

Retrieval results of Query 1 (Keyword Retrieval Mode).

Table 11.

Frequency statistics of each keyword.

The performance of retrieval methods is typically assessed from three perspectives: Precision, Recall, and F1-score. For the ten retrieval queries designed in Table 9, the evaluation results for the retrieval outcomes of the keyword retrieval method based on full-word matching and the method proposed in this study are presented in Table 12. The proposed intelligent retrieval method exhibits significant performance improvement over the keyword retrieval method, particularly when the queries are ambiguous condition queries.

Table 12.

Evaluation of retrieval results.

4. Discussion

The experimental results reveal that the proposed geospatial data knowledge graph enables the standardized and normalized management of multi-source, heterogeneous geospatial data resources within a unified knowledge system. This approach effectively resolves the issue of semantic heterogeneity among data from different sources and standards. The constructed knowledge graph contains a total of 31,671 entities and 80,538 relations, which suggest a relatively large scale. Furthermore, the relation-to-entity ratios for the Intrinsic Content Module and the Form Module within the graph are 4.58 and 28.28, respectively. These high ratios signify a dense knowledge concentration within these modules. This dense knowledge concentration indicates strong synergistic associativity between data resources, which can offer effective support for subsequent data retrieval research.

Unlike traditional retrieval methods for geospatial data resources, the approach presented in this study, which utilizes LLMs and the knowledge graph for data retrieval, demonstrates superior performance. In particular, the proposed method caters to users with limited professional knowledge and scenarios involving ambiguous requirements in data trading. First, the traditional keyword retrieval method based on full-word matching depends solely on word segmentation and stop-word removal for extracting user requirements. This method can result in erroneous keyword extraction. For example, “data” as a supplementary description, should not be considered a keyword, and “less than” and “100 m” should not be separated, as “less than 100 m” represents the actual requirement defined by the user. By contrast, this study utilizes an LLM to perform deep semantic parsing of the query, which standardizes the extraction of user requirement points. This method effectively adapts to the expression styles of users lacking professional domain knowledge, which offers greater universality in data trading scenarios. Second, analyzing the retrieval results for Query 1 from the comparative experiments reveals that the keyword retrieval method based on full-word matching merely conducts a mechanical count of keyword occurrences; it disregards the semantic features of the keywords, which constitutes a major flaw. The semantic retrieval method proposed herein relies more on reasoning based on path relationships within the knowledge graph, which makes it more rational than keyword retrieval and yields results with greater explainability.

At present, many open platforms are available for managing and sharing geospatial data resources. Widely used examples include PANGAEA (https://pangaea.de/ (accessed on 10 July 2025)), which is jointly operated by the Alfred Wegener Institute in Germany and the Center for Marine Environmental Sciences at the University of Bremen; NASA’s Earth Science Data Systems (ESDS) (https://www.earthdata.nasa.gov/data/catalog (accessed on 10 July 2025)); and China’s National Earth System Science Data Center (https://www.geodata.cn/main/ (accessed on 10 July 2025)), which is operated by the Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences. Table 13 presents a multi-dimensional comparison between the GDR prototype system discussed in this chapter and these platforms regarding data resource management and retrieval. The “Data Feature Dimension” refers to the number of types of data characteristic attributes that are structurally represented on the data detail pages. Among them, spatiotemporal extent, data theme, dataset name, and data abstract are features represented by all platforms. PANGAEA adds characterization of source projects. Meanwhile, ESDS adds features such as spatial resolution, types of observation platforms, and processing levels. The National Earth System Science Data Center adds features including data processing methods and data quality. The GDR system in this study additionally incorporates features such as temporal resolution, temporal scale, and spatial scale beyond those mentioned. With the exception of the GDR system, none of the current platforms provides semantic retrieval services. The reason is that they have not constructed a knowledge graph or semantic network capable of offering semantic association information between data resources.

Table 13.

Comparison of geospatial data resource management and retrieval systems.

5. Conclusions

This study constructed a geospatial data knowledge graph to address the shortcomings in the management of geospatial data resources on trading platforms and the issues of poor precision and narrow coverage associated with traditional keyword retrieval methods. The primary objective involves modeling the multi-dimensional characteristic attributes of data resources. This approach achieves a knowledge-based representation of the multi-dimensional characteristics of multi-source, heterogeneous geospatial data and constructs a semantic association network among data resources. Building upon this foundation, a semantic retrieval method for geospatial data based on the knowledge graph is proposed. Compared with existing retrieval methods employed by data trading platforms, this method achieves a deep-level understanding of the ambiguous retrieval requirements of users lacking professional domain knowledge and effectively enhances data retrieval efficiency. Based on the aforementioned research, this study designs the GDR prototype system. By simulating GDR scenarios with varying difficulties and requirements and comparing the system with other retrieval methods, the effectiveness and superiority of the proposed method are validated.

Although this study has relatively progressed in this field, some aspects still require improvement and optimization. This research will be extended based on the following points:

(1) In the proposed geospatial data knowledge graph, the attributes within the ontology model can still be expanded and refined. Simultaneously, the data collection and preprocessing stages during the graph construction process involve significant manual intervention. Future work in this area will consider introducing LLMs to automate tasks currently reliant on human effort.

(2) The retrieval model proposed in this study is based on a single-turn query–response paradigm, which is designed specifically for the semantic parsing and precise matching of a single user input. However, it lacks support for contextual coherence, multi-turn progressive intent, and dynamic interactive requirements. While this model effectively meets the demands of current GDR scenarios, it struggles to adapt to complex, multi-stage, open-ended information needs (e.g., multi-criteria combined reasoning or progressive data exploration). Future work will consider extending toward a context-aware, conversational retrieval framework. As a result, an interactive retrieval system capable of iterative refinement will be constructed to support dynamic query reformulation based on natural language input and multi-granularity knowledge reasoning.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Jianghong Bo and Xuan Ding; methodology, Jianghong Bo, Wang Li, and Chuli Hu; software, Wang Li; validation, Wang Li and Ran Liu; formal analysis, Ran Liu and Xuan Ding; investigation, Jianghong Bo and Ran Liu; resources, Mu Duan; data curation, Mu Duan; writing—original draft preparation, Jianghong Bo and Wang Li; writing—review and editing, Wang Li, Mu Duan, Xuan Ding, and Chuli Hu; visualization, Ran Liu; supervision, Wang Li and Chuli Hu; project administration, Wang Li. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Nature Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (Grant No. 42401555) and the Hubei Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. JCZRQN202400143).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study is available on request from the corresponding author. The data is not publicly available due to their integration within the team’s internal database, which is structured for internal access and use. Direct public access to this database is not feasible due to operational, privacy, and security protocols.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used DeepSeek-V3 for the purposes of analyzing the requirements of users. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhao, X.; Chen, H.; Xing, Z.; Miao, C. Brain-Inspired Search Engine Assistant Based on Knowledge Graph. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2021, 34, 4386–4400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lipka, N.; Rossi, R.A.; Siu, A.; Zhang, R.; Derr, T. Knowledge Graph Prompting for Multi-Document Question Answering. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2–9 February 2024; Volume 38, pp. 19206–19214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Ji, Y.; Hui, B. A Dynamic Preference Recommendation Model Based on Spatiotemporal Knowledge Graphs. Complex Intell. Syst. 2025, 11, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumaier, S. Semantic Enrichment of Open Data on the Web—Or: How to Build an Open Data Knowledge Graph. Ph.D. Thesis, Technische Universität Wien, Vienna, Austria, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Färber, M.; Lamprecht, D. The Dataset Knowledge Graph: Creating a Linked Open Data Source for Datasets. Quant. Sci. Stud. 2021, 2, 1324–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Park, J. An Approach to Constructing a Knowledge Graph Based on Korean Open-Government Data. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 4095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Wang, P.; Ge, Y.; Luo, J.; Chen, H.; He, Y.; Lin, H. GeoKG-HSA: A Framework for Habitat Suitability Assessment with Geospatial Knowledge Graphs. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinform. 2025, 144, 104921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, H.; Chen, X.; Guo, X.; Zhao, Q.; Li, J.; Kang, L.; Liu, J. A Heterogeneous Geospatial Data Retrieval Method Using Knowledge Graph. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghaei, S.; Angele, K.; Huaman, E.; Bushati, G.; Schiestl, M.; Fensel, A. Interactive Search on the Web: The Story So Far. Information 2022, 13, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, L.; Liu, C.; Fan, L.; Kwan, M.-P. An OGC Web Service Geospatial Data Semantic Similarity Model for Improving Geospatial Service Discovery. Open Geosci. 2021, 13, 245–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Goodchild, M.F.; Raskin, R. Towards Geospatial Semantic Search: Exploiting Latent Semantic Relations in Geospatial Data. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2014, 7, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, H.; Li, Z.; Akinboyewa, T.; Lessani, M.N. An Autonomous GIS Agent Framework for Geospatial Data Retrieval. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2025, 18, 2458688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiegand, N.; García, C. A Task-Based Ontology Approach to Automate Geospatial Data Retrieval. Trans. GIS 2007, 11, 355–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Gao, X.; Luo, K.; Wang, D.; Sun, K. A Chinese Geological Time Scale Ontology for Geodata Discovery. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Geoinformatics (GEOINFORMATICS 2015), Wuhan, China, 18–20 June 2015; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Zhu, Y.; Pan, P.; Hou, Z.; Wang, D.; Li, W.; Song, J. Geospatial Data Ontology: The Semantic Foundation of Geospatial Data Integration and Sharing. Big Earth Data 2019, 3, 269–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yue, P.; Wu, H.; Teng, B.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, C. A Question-Answering Framework for Geospatial Data Retrieval Enhanced by a Knowledge Graph and Large Language Models. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2025, 18, 2510566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stančin, I.; Jović, A. An Overview and Comparison of Free Python Libraries for Data Mining and Big Data Analysis. In Proceedings of the 42nd International Convention on Information and Communication Technology, Electronics and Microelectronics (MIPRO), Opatija, Croatia, 20–24 May 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 977–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Zhu, Y.Q.; Pan, P.; Luo, K.; Wang, D.X.; Hou, Z.W. Morphology-Ontology of Geospatial Data and Its Application in Data Discovery. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Geoinformatics (GEOINFORMATICS 2015), Wuhan, China, 18–20 June 2015; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanović, M.; Stanimirović, A.; Stoimenov, L. Methodology for Geospatial Data Source Discovery in Ontology-Driven Geo-Information Integration Architectures. J. Web Semant. 2015, 32, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, T.; Zhu, H.; Sun, L. TPLinker: Single-Stage Joint Extraction of Entities and Relations Through Token Pair Linking. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.13415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joulin, A.; Grave, E.; Bojanowski, P.; Douze, M.; Jégou, H.; Mikolov, T. Fasttext.zip: Compressing Text Classification Models. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1612.03651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Hagelien, T.F.; Natvig, M.; Li, J. Ontology-Based Semantic Search for Open Government Data. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 13th International Conference on Semantic Computing (ICSC), Newport Beach, CA, USA, 3–5 February 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, A.; Gueta, A.; Gilon, O.; Liu, C.; Erell, S.; Nguyen, L.H.; Hao, X.; Jaber, B.; Reddy, S.; Kartha, R.; et al. LLMs Accelerate Annotation for Medical Information Extraction. In Proceedings of the Machine Learning for Health (ML4H), Baltimore, MD, USA, 12–13 December 2023; PMLR: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023; pp. 82–100. Available online: https://proceedings.mlr.press/v225/goel23a.html (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Rong, J.; Chen, H.; Chen, T.; Yu, X.; Liu, Y. Retrieval-Enhanced Visual Prompt Learning for Few-Shot Classification. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.02243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Feng, B.; Xue, B.; Wang, B.; Wu, B.; Lu, C.; Zhao, C.; Deng, C.; Zhang, C.; Ruan, C.; et al. DeepSeek-V3 Technical Report. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.19437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.X.; Zhou, K.; Li, J.; Tang, T.; Wang, X.; Hou, Y.; Min, Y.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, J.; Dong, Z.; et al. A Survey of Large Language Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.18223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, J.; Wang, X.; Schuurmans, D.; Bosma, M.; Ichter, B.; Xia, F.; Chi, E.; Le, Q.; Zhou, D. Chain-of-Thought Prompting Elicits Reasoning in Large Language Models. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 24824–24837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinanda, R.; Meij, E.; de Rijke, M. Knowledge Graphs: An Information Retrieval Perspective. Found. Trends Inf. Retr. 2020, 14, 289–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ristad, E.S.; Yianilos, P.N. Learning String-Edit Distance. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 1998, 20, 522–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Lu, B. A Normalized Levenshtein Distance Metric. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2007, 29, 1091–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lan, Y.; Jiang, J. Query Graph Generation for Answering Multi-Hop Complex Questions from Knowledge Bases. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL 2020), Seattle, WA, USA, 5–10 July 2020; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 3456–3466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savona, M. The Value of Data: Towards a Framework to Redistribute It; Working Paper No. 2019-05; SPRU—Science and Technology Policy Research; University of Sussex: Brighton, UK, 2019; Available online: https://iris.luiss.it/handle/11385/198247 (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Attard, J.; Brennan, R. A Semantic Data Value Vocabulary Supporting Data Value Assessment and Measurement Integration. Data Policy 2018, 1, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Lu, G.; Liu, Y.; Deng, X. A Modified PSO Algorithm with Exponential Decay Weight. In Proceedings of the 2017 13th International Conference on Natural Computation, Fuzzy Systems and Knowledge Discovery (ICNC-FSKD), Guilin, China, 29–31 July 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 239–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Zhang, Q.; Dragut, E.; Caragea, C.; Jan Latecki, L. DMDD: A Large-Scale Dataset for Dataset Mentions Detection. Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 2023, 11, 1132–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Qiu, M.; Shi, C.; Zhang, T.; Liu, T.; Li, L.; Wang, J.; Wang, M.; Huang, J.; Lin, W. EasyNLP: A Comprehensive and Easy-to-Use Toolkit for Natural Language Processing. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2205.00258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sejuti, Z.A.; Islam, M.S. A Hybrid CNN–KNN Approach for Identification of COVID-19 with 5-Fold Cross Validation. Sens. Int. 2023, 4, 100229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicco, D.; Jurman, G. The Advantages of the Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) Over F1 Score and Accuracy in Binary Classification Evaluation. BMC Genom. 2020, 21, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the International Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.