Abstract

Establishing digital twin scenes facilitates the understanding of geospatial phenomena, representing a significant research focus for GIS scientists and engineers. However, current research on digital twin scenes modeling relies on manual intervention or the overlay of static models, resulting in low modeling efficiency and poor standardization. To address these challenges, this paper proposes a knowledge graph-guided and multimodal data fusion-driven rapid modeling method for digital twin scenes, using bridge tower construction as an illustrative example. We first constructed a knowledge graph linking the three domains of “event-object-data” in bridge tower construction. Guided by this graph, we designed a knowledge graph-guided multimodal data association and fusion algorithm. Then a rapid modeling method for bridge tower construction scenes based on dynamic data was established. Finally, a prototype system was developed, and a case study area was selected for analysis. Experimental results show that the knowledge graph we built clearly captures all elements and their relationships in bridge tower construction scenes. Our method enables precise fusion of 5 types of multimodal data: BIM, DEM, images, videos, and point clouds. It improves spatial registration accuracy by 21.83%, increases temporal fusion efficiency by 65.6%, and reduces feature fusion error rates by 70.9%. Local updates of the 3D geographic scene take less than 30 ms, supporting millisecond-level digital twin modeling. This provides a practical reference for building geographic digital twin scenes.

1. Introduction

A digital twin scene is a 3D digital mirror constructed in virtual space that is geometrically consistent with the real scene, semantically rich, synchronized in state, and can interactively evolve. It can support users’ intuitive perception and collaborative analysis of reality [1,2,3,4,5]. Geographic digital twin is an extension of digital twin in the field of geographic information [6,7,8,9,10]. Many studies have shown that geographic digital twin scenes are important across multiple engineering domains [11,12,13,14,15,16]. Bridge tower construction includes geographic objects such as 3D terrain and engineering facilities. It has dynamic characteristics like an evolving construction process. Such scenes, where traditional methods like two-dimensional drawings and construction logs are used, struggle to capture spatiotemporal changes [17,18]. Establishing a digital twin scenes for bridge tower construction helps visualize the temporal and spatial evolution of progress and process simulations. It also supports risk warnings and emergency decision-making during extreme weather or sudden disaster scenes [19,20,21,22,23,24]. Therefore, although digital twins cover the entire lifecycle of design, construction, and operation, we mainly focus on conducting research during the bridge tower construction phase.

Extensive research has been conducted on digital twin scenes modeling. By utilizing drone oblique photogrammetry technology to construct digital city models, combined with 3D visualization and interactive information technologies, decision support is provided for urban planning and engineering management [25]. Using 3D laser scanning technology, establish a digital twin model for bridge maintenance to enhance the efficiency and accuracy of bridge structural health monitoring [26]. By integrating virtual geographic environments with traditional BIM, a digital twin scene for bridge construction has been established, breaking down information barriers between bridge design and construction [27]. However, the aforementioned research (1) relies heavily on manual intervention or static model overlay in its modeling process, making it difficult to adapt to the rapid evolution of component states and process logic during bridge tower construction, resulting in low modeling efficiency; (2) Modeling data is constrained to single-modality, making it difficult to fully capture the geometric form, semantic attributes, and dynamic behavior of scenes objects. Therefore, there is an urgent need for a new methodology and paradigm that can integrate multi-modal perception data, embed domain knowledge, and support dynamic, rapid modeling to meet the real-time and consistency requirements of digital twin.

Numerous scholars have conducted in-depth research in the field of multimodal data fusion using algorithms such as Kalman filtering, weighted averaging, hierarchical fusion theory, or neural networks [28]. Multimodal neural networks based on BERT and DenseNet fuse ubiquitous audio-visual and textual data to extract disaster semantic information, enhancing disaster scenes recognition and dynamic perception capabilities [29,30]. Deep neural networks fuse cross-platform information to address occlusion and data gaps in single-modal data, enabling accurate reconstruction of 3D continuous surfaces [31]. Although these approaches have made progress in data registration and geometric reconstruction, they generally rely on low-level feature matching and lack domain knowledge guidance. When applied to complex scenes like bridge tower construction, which involve large semantic spans and rapid spatiotemporal changes, they are prone to semantic discontinuities or logical conflicts. This results in low data fusion efficiency and hinders the rapid construction of digital twin scenes.

Knowledge graphs have garnered significant attention as an emerging technology in recent years. Essentially a semantic network, it structurally describes knowledge by representing entities and attributes as nodes and semantic relationships as edges. Through predefined construction entities and process logic, it provides semantic anchors and association rules for multimodal data, enabling cross-modal spatiotemporal correlation fusion and rapid scenes generation, demonstrating potential for supporting efficient modeling [32,33,34,35,36]. However, scenes like bridge tower construction involve not only the incremental growth of geometric structures but also the tightly coupled evolution of process logic, equipment status, and structural response. Existing knowledge graph construction techniques have not been oriented toward bridge tower construction scenes, making it challenging to characterize the features and associative relationships among construction events, scenes objects, and data models.

This paper proposes a rapid modeling method for digital twin scenes driven by knowledge graph guidance and multimodal data fusion, leveraging the strengths of knowledge graphs and multimodal data. The method first constructs a bridge tower construction knowledge graph linking three domains of “event-object-data.” It then achieves semantic alignment and associative fusion of multimodal data based on the knowledge graph. Finally, it achieves rapid modeling and updating of bridge tower construction data twin scenes based on the knowledge graph and multimodal fusion data. This approach aims to establish a closed-loop collaborative mechanism of “knowledge guidance-data fusion-model generation,” enhancing the modeling efficiency and semantic integrity of bridge tower construction digital twin scenes. It provides reliable theoretical and technical support for bridge digital twins and intelligent construction.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents a methodology for rapid modeling of bridge tower construction scenes driven by knowledge graph guidance and multimodal data fusion. Section 3 selects a representative bridge tower as a case study, develops a prototype system, and analyzes the effectiveness of the methodology. Finally, Section 4 concludes with a discussion and summary.

2. Methods

2.1. Overall Research Approach

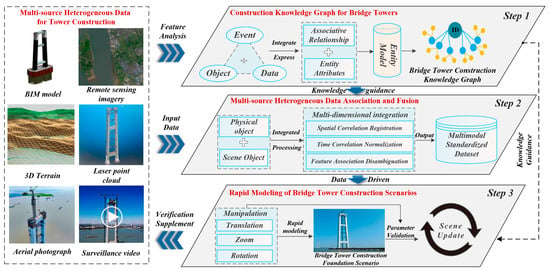

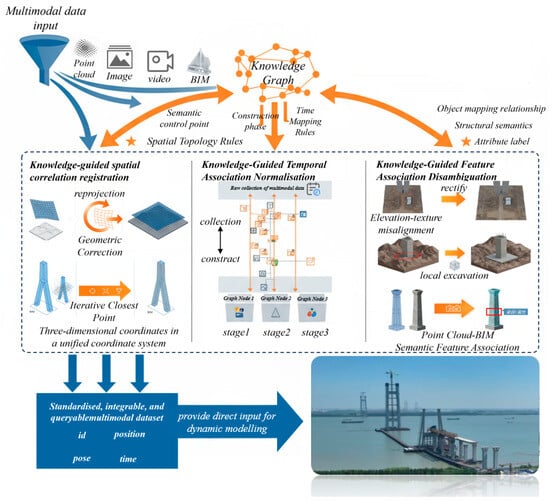

The overall framework for the knowledge graph-guided and multimodal data fusion-driven rapid modeling method for digital twin scenes, is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Overall Research Framework.

First, for the complexity and dynamic nature of Bridge tower construction processes. We analyze the characteristics and interrelationships of construction events, entities, and data, and construct a knowledge graph that links events, objects, and data. Next, the knowledge graph’s semantic guidance mechanism helps associate and fuse multimodal data—such as BIM models, remote sensing imagery, 3D terrain data, and laser point clouds. This process spans spatial, temporal, and feature-based dimensions, creating a spatiotemporally consistent multimodal associative fusion dataset. Building on this dataset, we use spatial semantic constraint rules from knowledge graph retrieval to integrate multimodal data. This enables the rapid establishment of foundational scenes for Bridge tower construction. scenes updates occur through knowledge graph discovery and dynamic data-driven mechanisms. As a result, digital twin scenes for Bridge tower construction can be quickly generated. This provides scenes support for decision-making and construction management in Bridge tower projects.

2.2. Construction of a Knowledge Graph for Bridge Tower Construction Linking the Three Domains of “Events-Objects-Data”

Bridge tower construction involves complex environments with numerous dynamic influencing factors. Knowledge graphs can clearly express the associative relationships between objects and data during bridge tower construction. Therefore, this paper analyzes bridge tower construction events from the perspective of process changes and proposes an integrated expression model linking the three domains of “events-objects-data” in bridge tower construction.

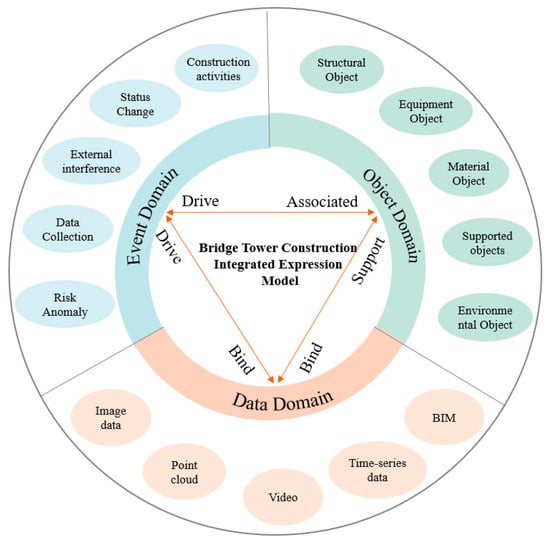

The integrated expression model for bridge tower construction linking the three domains of “event-object-data” is shown in Figure 2. The “event domain” centers on the construction process chain, describing various critical events during bridge tower construction. The “object domain” delineates the primary participants in each bridge tower construction event, clarifying hierarchical relationships among event objects. The “data domain” presents diverse heterogeneous data types associated with different events and objects within the bridge tower construction scenes. The tri-domain linkage mechanism among the event domain, object domain, and data domain provides a dynamic associative network for multimodal data fusion in complex construction scenes. The formal expression of the model is shown as follows:

Figure 2.

Integrated Expression Model for Bridge tower Construction in Three Domains.

In the formula, (M) denotes the overall semantic structure model of the bridge tower construction scene. (E) (Event) represents the set of construction events, including construction activities, state changes, external disturbances, data acquisition, and risk anomalies. (O) (Object) denotes the object set, encompassing the entities associated with various events, such as structural components, construction equipment, materials, auxiliary facilities, and environmental elements. (D) (Data) represents the data set, which includes various types of multi-source heterogeneous data entities within the scene. (R) (Relation) denotes the set of semantic relations that link events, objects, and data. (P) (Property) represents the set of attributes describing the characteristics of nodes in the graph.

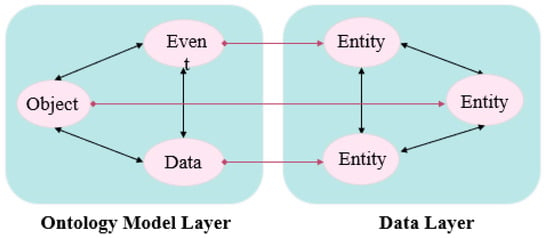

Based on the above three domains associated integrated representation model for bridge tower construction, this study constructs a bridge tower construction knowledge graph by combining a top-down ontology definition with a bottom-up instance mapping strategy. The ontology model serves as the schema layer, where domain experts first define class hierarchies and attributes in accordance with the Technical Specification for Construction of Highway Bridge and Culvert (JTG/T 3650-2020) [37]. Subsequently, the knowledge graph is constructed and dynamically updated through instance mapping, as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Instantiation Mapping.

The instantiation process mainly consists of two components. The first is static instantiation, in which geometric information and component attributes are automatically extracted from BIM files in IFC format and mapped to populate the “object” domain. The second is a dynamic update mechanism. An event triggered approach is adopted, whereby changes in key construction activities recorded in construction logs, such as process transitions, equipment entry and exit, and the completion of concrete pouring, trigger the dynamic evolution of relevant entity nodes and their semantic relationships within the knowledge graph. In this manner, the latest monitoring data and construction log information are synchronously updated in the knowledge graph, thereby enabling continuous updating and representation of the construction stage states of the bridge tower.

Instantiation mapping transforms the abstract ontological structures of events, objects, and entities into concrete instances and their associated relationships. Partial instantiation results for the Zhangjinggao South Tower construction scene are illustrated in Figure 4. Through this mapping, abstract concepts are converted into a concrete semantic network. For example, the “segment construction” event is decomposed into specific activities such as “mid crossbeam segment hoisting” and is linked to potential risks such as “electric shock.” These events are further associated with physical objects and multisource data entities, thereby establishing a closed loop representation of the constructions.

Figure 4.

Example of Instantiation Mapping Results.

2.3. Knowledge Graph-Guided Multimodal Data Association and Fusion

Addressing the issues of low efficiency and poor standardization in the fusion of multimodal data, including images, videos, point clouds, and BIM, within bridge tower construction scenes. This section leverages the “event-object-data” three domains knowledge graph established in Section 2.2. Guided by its predefined entity relationships, phase labels, and object referencing, this graph drives multimodal data through spatial correlation registration, temporal correlation alignment, and feature correlation disambiguation. The process ultimately outputs a standardized, integrable, and queryable multimodal dataset, providing direct input for the dynamic modeling in Section 2.4. The fusion workflow is illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Multimodal Data Association and Fusion.

Firstly, to achieve a unified spatial representation of physical objects, knowledge-guided spatial correlation registration is employed. This unifies heterogeneous data such as remote sensing imagery, DEM, point clouds, and BIM within a target coordinate system, ensuring geometric overlay and measurable positioning. The knowledge graph facilitates efficient registration of multimodal data by providing semantic control points and spatial topological rules. Remote sensing imagery undergoes orthorectification through geometric inversion and resampling, combining Rational Polynomial Curve (RPC) models with Digital Elevation Models (DEM). This is followed by reprojection within the unified coordinate system defined by the knowledge graph. Point clouds and BIM models undergo initial alignment based on semantic keypoints within the knowledge graph, subsequently driving the Iterative Closest Point (ICP) algorithm to achieve high-precision rigid registration. All modality data are ultimately transformed into a unified geographic coordinate system, satisfying the spatial consistency requirements of the three-dimensional geographic information platform and establishing a geometric baseline for subsequent fusion.

Secondly, addressing the temporal evolution characteristics of scenes-oriented multimodal data, knowledge-driven temporal correlation normalization is employed. Building upon spatial registration, data is restructured according to construction logic, overcoming limitations imposed by raw timestamps to ensure semantic consistency, comparability, and traceability within each phase. To accurately map discrete and unordered data into the construction phases defined by the knowledge graph, we present the pseudocode for the “Construction Phase Matching” mechanism. This algorithm traverses the raw data, extracts temporal features, and performs logical judgment based on the phase start and end times predefined in the graph, establishing a “construction phase valid data” bidirectional association.

After processing by Algorithm 1, all filtered data subsets carry explicit phase identifiers, providing structured temporal data support for dynamic updates and historical reconstruction within the bridge tower construction digital twin scenes.

| Algorithm 1. Construction Phase Matching | |

| Input: Raw Data Set DataRaw, Knowledge Graph GraphKG | |

| Output: Temporally Aligned Data Set DataAligned | |

| 1 | DataAligned ← ∅ //Initialize an empty aligned data set |

| 2 | for each DataItem ∈ DataRaw do //Iterate through all raw data items |

| 3 | TimeItem ← ExtractTimestamp(DataItem) //Extract creation time from metadata |

| 4 | PhaseMatch ← NULL //Reset current phase match status |

| # Temporal Matching with Knowledge Graph | |

| 5 | for each PhaseNode ∈ GraphKG.Nodes do //Query every construction phase |

| 6 | if PhaseNode.TimeStart ≤ TimeItem and TimeItem ≤ PhaseNode.TimeEnd then |

| 7 | PhaseMatch ← PhaseNode.ID //Assign phase ID if matched |

| 8 | break //Exit inner loop once a match is found |

| # Semantic Association to Graph Topology | |

| 9 | if PhaseMatch is not NULL then //A valid phase was found |

| 10 | Link(DataItem, PhaseMatch, GraphKG) |

| 11 | DataAligned ← DataAligned ∪ {DataItem} //Add item to the aligned result set |

| 12 | else |

| 13 | Log(DataItem, “Phase Not Found”) //Log unmapped items for review |

| 14 | return DataAligned //Return the temporally structured data set |

Finally, addressing modal ambiguity under spatio-temporal constraints, knowledge-guided feature association disambiguation identifies observation data from different modalities describing the same object entity. Unique object identifiers are assigned to achieve semantic alignment and fusion at the feature level. The “object domain” within the knowledge graph provides mapping relationships, structural semantics, and attribute labels. Combined with the following three strategies, we resolve geometric, textural, and semantic conflicts arising from multisource observations: First, regarding geometric distortion in terrain imagery, we employ “elevation texture correction”, which utilizes semantic constraints from the knowledge graph to rectify texture stretching or misalignment caused by insufficient DEM precision. Second, regarding the penetration between the model and the terrain, we implement “local DEM hollow-out”. Guided by graph nodes, this method performs Boolean subtraction operations on the terrain mesh based on the BIM model footprint surface and placement area to avoid geometric conflicts. Finally, regarding the logical interoperability of heterogeneous data, we utilize “semantic feature association”. Based on the BIM component ID as the unique identifier and combined with geometric semantic knowledge, this strategy logically binds multisource observation features. To standardize this association process, we designed the pseudocode for the “Cross modal Object ID Association” mechanism, as shown in Algorithm 2. This algorithm utilizes the BIM model as the geometric and semantic benchmark, filters candidate sets via spatial Intersection over Union (IoU), and performs semantic consistency verification by incorporating topological rules from the knowledge graph.

| Algorithm 2. Cross modal Object ID Association | |

| Input: Unlabeled Point Cloud CloudRaw, BIM Elements SetBIM, Ontology GraphKG | |

| Output: Assigned Global Object ID GlobalID | |

| # Spatial Registration | |

| 1 | CloudAligned ← MatrixRigid · CloudRaw //Apply rigid transformation to align coordinates |

| 2 | SetCandidate ← ∅ //nitialize the list of candidate elements |

| # Geometric Filtering via IoU | |

| 3 | for each ElementBIM ∈ SetBIM do //Iterate through all BIM components |

| 4 | IoUVal ← CalculateIoU(CloudAligned, ElementBIM) //Compute Intersection over Union |

| 5 | if IoUVal > ThresholdGeo then |

| 6 | SetCandidate ← SetCandidate ∪ {ElementBIM} //Add to candidate set |

| # Semantic & Topological Verification | |

| 7 | MatchOptimal ← NULL //Initialize the optimal match result |

| 8 | ScoreMax ← 0 //Initialize the maximum match score to zero |

| 9 | for each Candidate ∈ SetCandidate do //Evaluate each potential match |

| 10 | ScoreSem ← CalculateSim(CloudRaw.FeatureType, Candidate.Type, GraphKG) //Match point cloud labels with element types |

| 11 | IsTopoValid ← CheckTopology(CloudRaw, Candidate, GraphKG) //Validate if relative positions are logical |

| 12 | if ScoreSem > ScoreMax and IsTopoValid then |

| 13 | ScoreMax ← ScoreSem //Update the highest score |

| 14 | MatchOptimal ← Candidate //Update the best match |

| # ID Binding | |

| 15 | if MatchOptimal is not NULL then //A valid match was found |

| 16 | CloudRaw.GlobalID ← MatchOptimal.GlobalID //Assign the unique BIM ID to the cloud data |

| 17 | return MatchOptimal.GlobalID //Return the assigned ID |

| 18 | else |

| 19 | return NULL //Return NULL if no suitable match is found |

Ultimately, through the aforementioned strategies and algorithms, each physical entity establishes an explicit binding with its multi-modal observational representations, forming object-level data units that directly support 3D scenes integration and semantic querying.

2.4. Rapid Modeling of Bridge Tower Construction Scenes Based on Dynamic Data

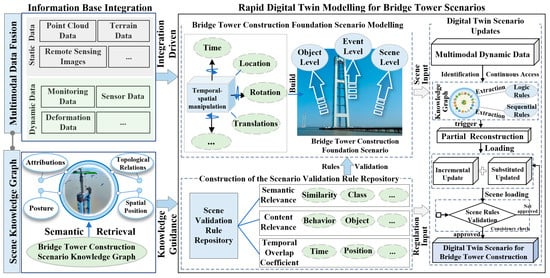

To address the issue of low modeling efficiency in digital twin scenes for Bridge tower construction, the static data from the multimodal scenes data established in Section 2.3 is first employed as the skeletal framework for scenes construction. The dynamic data is then associated and mapped to the quantitative model and the scenes knowledge graph. Secondly, by integrating the scenes validation rule repository constructed through knowledge-guided methods, spatio-temporal operations were performed on the scenes’ multimodal data to establish the foundational scenes for Bridge tower construction. Finally, as dynamic data is continuously fed into the system, the trigger mechanism matches and evaluates this data against the knowledge graph, thereby updating the construction scenes. The specific methodology is illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Rapid modeling of bridge tower construction scenes.

Multimodal fusion data is categorized into static data types such as terrain data, point cloud data, BIM models, and remote sensing data. as well as dynamic data such as monitoring data, sensor data, deformation data, and environmental data, and associate these with the graph nodes retrieved from the scene knowledge graph generated in Section 2.2, which contain the attribute information, spatial poses, topological relationships, and spatial location data required for scene modeling. Static data serves as the framework for scene modeling, Incorporate all elements into the initial scene modeling; Dynamic data, serving as incremental data for scene modeling, is integrated on demand based on construction phases and semantic matching results.

Based on the information required for semantic retrieval scene modeling, a scene rule validation repository is constructed across three levels: semantic relevance, content relevance, and spatiotemporal overlap. Following the integration of static data with the scene knowledge graph, spatiotemporal operations are performed within the virtual environment. These include translating and scaling the model within the scene, as well as defining the display time. Then, in conjunction with the scene rule validation library, perform rule validation on the models within the scene at the object level, event level, and scene level. Among these, the semantic relevance in rule validation serves to determine whether the introduced model or data constitutes a valid component within the bridge tower construction scene. Whether the added model is highly relevant to the bridge tower construction scene and whether it belongs to the category of the bridge tower construction scene; Content relevance refers to whether the attributes or behaviors added to the model can be matched to corresponding entity attributes or relationship descriptions within the knowledge graph. The temporalspatial overlap degree refers to the consistency between the temporal period and spatial location of the model’s existence and the extracted rule set. Ensure that its spatial distribution aligns with the temporal logic of the construction phases, with the spatial verification method as shown in Equation (2).

denotes the cumulative spatial orientation index used to verify the geometric consistency of the model; m represents the total number of line segments obtained from the discretization of the spatial linear model; i is the index of the current line segment; and denote the coordinate difference components of the i-th line segment along the X-axis and Y-axis, respectively; denotes the vertical coordinate difference in the i-th line segment along the Z-axis; and is the two-argument inverse tangent function, which is used here to compute the spatial inclination angle of the line segment.

As multimodal dynamic data is continuously ingested, it shall be validated against the logical and temporal rules defined within the knowledge graph, and trigger the local reconstruction of the scene model, Its reconstruction types encompass two update methods: incremental updates and replacement updates. Incremental updates are a method of updating a model by adding new features to the existing model. Replacement updates involve deleting and substituting models that already exist within the scene. Specifically, the classification of update types for its scene model is based on the semantic states extracted from the knowledge graph. Incremental updates encompass modifications to reinforcement arrangements based on point cloud data, as well as newly added solid models generated during the bridge tower construction process. Replacement updating refers to the process of restoring auxiliary construction components removed during bridge tower construction and backfilling excavated terrain. Following the partial model update of the scene, consistency checks will be performed against the bridge tower construction base scene and the scene validation rules. If the verification fails, the process will revert to the partial update model step to reexcute the update. Upon passing inspection, a digital twin model for the bridge tower construction shall be generated. This enables rapid modeling and dynamic updates driven by live data.

3. Case Study Experiment and Analysis

3.1. Case Description and Prototype System Development

The bridge tower construction scene exhibits typical characteristics of a geographic scene. It includes static geographic elements such as terrain, landforms, structural components, and transportation facilities. It also involves dynamic processes such as construction progress evolution and equipment movement. Therefore, this study selects the Zhangjinggao Yangtze River Bridge in Jiangsu Province, eastern China, as the case study for experimental analysis. The bridge is currently the highway suspension bridge with the largest span in the world. The main span of the south navigation channel reaches 2300 m, and the South Tower has a height of approximately 350 m. The construction environment is complex and highly challenging. The case study area focuses on the construction site of the South Tower of the Zhangjinggao Bridge.

3.1.1. Data Description

Basic geographic data primarily includes digital elevation models and orthorectified imagery, sourced from open-source websites; Bridge BIM models are primarily provided by construction contractors, encompassing geometric and attribute information for key structural components such as bridge towers, main girders, anchorages, cable saddles, and construction access roads. Point cloud data was collected using a 3D laser scanner; additionally, it includes independently acquired aerial imagery, video data, and vector data of the canyon water surface.

3.1.2. Prototype System Development

The configuration of the prototype system development environment is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Hardware and software environment.

Supported by the aforementioned environment, this paper leverages the Cesium 3D geographic visualization engine, integrated with the Vue3 frontend framework and Neo4j knowledge graph database. By merging foundational geographic data, bridge BIM models, and dynamic observation data, we developed a multi-source data fusion modeling and visualization system for bridge construction geographic scenes. The system primarily comprises an overview module, a tower construction module, a meteorological conditions module, and a knowledge graph module. The main interface of the system is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Prototype System Interface.

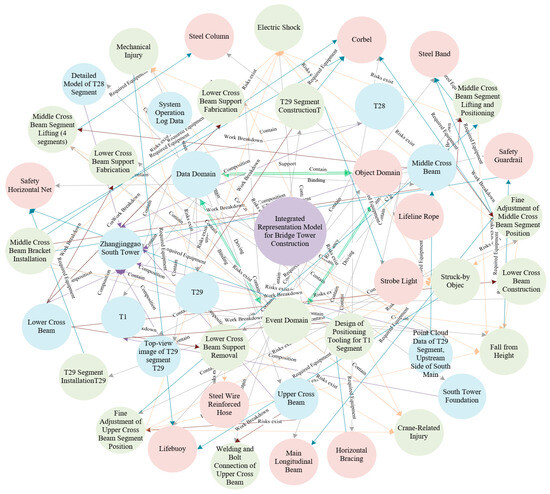

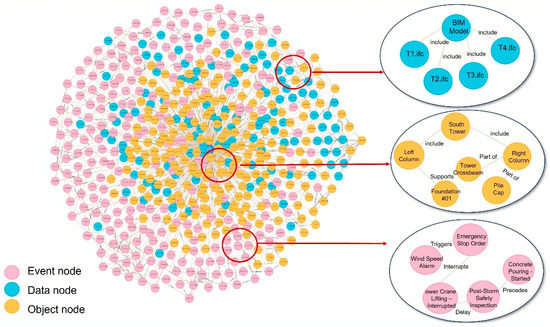

3.2. Knowledge Graph Construction Results and Analysis

We employ the Neo4j graph database to store the knowledge graph, supporting CRUD operations via Cipher queries. The completed knowledge graph comprises 570 nodes and 985 relationships, enabling a clear and systematic depiction of all elements and their interconnections within bridge tower construction scenes, as illustrated in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Knowledge Graph of Bridge Construction scenes.

The digital twin scenes knowledge graph unifies and associates spatial semantics, temporal semantics, and feature semantics within multimodal data, providing semantic constraints for rapid fusion of multi-source data. Taking bridge tower construction events as an example, their spatial semantics encompass the spatial positions of scenes objects, topological relationships, and component hierarchical structures, offering spatial references and registration constraints for point cloud, BIM, and remote sensing imagery data. Temporal semantics centers on the construction process chain, capturing the sequential evolution of construction events. This enables dynamic information, such as sensor monitoring data, image sequences, and construction logs, to achieve corresponding matching and phase normalization along the timeline. Feature semantics establishes correspondences between different modal data through standardized descriptions of entity attributes, state parameters, and behavioral relationships.

Simultaneously, for dynamic scenes modeling updates, the construction event chains, spatial orientation, and topological relationships, and object dependencies stored within the knowledge graph collectively form a semantics-driven mechanism for dynamic updates. When new data is ingested, the system can rapidly identify affected objects and associated components based on the event logic and spatial constraints defined in the knowledge graph, thereby constraining incremental or replacement updates to local models. For instance, when sensor data indicates completion of a tower segment, the knowledge graph automatically invokes corresponding BIM components, point cloud data, and image models to update the structural representation of the local scenes based on the phase logic of the event chain. This semantically driven dynamic mapping mechanism ensures the digital twin scenes maintains structural consistency and temporal coherence throughout iterative updates from multiple data sources, significantly enhancing modeling efficiency.

3.3. Multimodal Data Association and Fusion Results and Analysis

According to the technical methodology proposed in Section 2.3 of this paper, we performed fusion processing on multimodal data collected during Bridge tower construction, including remote sensing imagery, DEM, multi-period ground surveillance video, laser scanning point clouds, and the Bridge tower BIM model. In experimental validation, we established a control group (G1) and an experimental group (G2). The control group (G1) employed traditional methods for multimodal data fusion: subsequently, for 3D data fusion, referencing the geometric matching criteria mentioned in ‘A Registration Method Based on Planar Features Between BIM Model and Point Cloud’ [38], we utilized the Iterative Closest Point (ICP) algorithm without semantic constraints to perform spatial registration between the point cloud and the BIM model. In the temporal dimension, data were simply sorted solely according to the chronological order of their original generation timestamps. The experimental group (G2) introduced semantic constraint rules concerning temporal, spatial, and feature aspects from the knowledge graph. The experiment was quantitatively evaluated across three dimensions: spatial fusion accuracy, temporal fusion, and feature fusion standardization. To ensure the scientific validity of the evaluation results, all ground truth values were obtained through manual item by item verification of the fusion results. The definitions of each evaluation metric are as follows:

The Sequence Fusion Error Rate () is defined as the proportion of data entries incorrectly classified into non corresponding construction phases relative to the total data volume, as shown in Equation (3):

where represents the total number of multimodal data entries involved in temporal fusion; represents the number of data entries found to have incorrect timestamp archiving or association with incorrect construction phase semantic labels after manual verification against construction logs and data content.

The Textural Feature Error Rate () is defined as the proportion of points in a manual random check sample where the texture projection deviation exceeds a threshold, as shown in Equation (4):

where represents the total number of feature checkpoints randomly selected on the surface of the fused 3D scene (set to in this experiment); represents the number of points where the Euclidean distance between the texture projection position and the actual geographic feature position exceeds a set threshold (e.g., 0.5 m).

The Attribute Query Error Rate () is defined as the proportion of cases where the system returns incorrect results or null values when querying object attributes, as shown in Equation (5):

where represents the total number of semantic query samples executed, covering valid BIM components as well as nearby clutter such as scaffolding and construction equipment; represents the number of incorrect matches, including incorrect component ID matching and clutter being incorrectly assigned BIM attributes; represents the number of abnormal false negatives (misses), specifically referring to cases where the system returns null values for valid BIM components.

The specific results are presented in Table 2:

Table 2.

Comparison of Spatial Fusion Accuracy.

Table 2 shows the error metrics for spatial registration across different modality combinations, with and without knowledge constraints. The results indicate that the G2 group achieved significantly improved spatial alignment accuracy across all data types following the introduction of the knowledge graph. Specifically, the orthorectification error for the fusion of remote sensing imagery and DEM decreased from 1.15 m to 1.03 m; the distance error after ICP registration between point clouds and BIM models decreased from 52.88 mm to 35.31 mm. The overall spatial registration accuracy of multimodal data improved by 21.83%, fully validating the positive guiding effect of semantic constraints on geometric optimization.

Table 3 evaluates the comparison of multimodal data fusion results with and without knowledge guidance across the temporal dimension. Results indicate that in the G1 group without knowledge guidance, the system relies on coarse timestamp matching and manual review, resulting in an average single fusion duration of 28.5 s; due to the lack of construction semantic discrimination capability, the error rate reached 11.2%. In contrast, the knowledge-guided G2 group employed construction ontology-driven semantic queries to directly correlate multimodal data. This approach not only elevated fusion efficiency to 9.8 s per session, representing a 65.6% improvement, but also substantially reduced the error rate to 2.5%, corresponding to a 77.7% decrease. This fully validates the dual advantage of the knowledge guidance mechanism in achieving “rapid and accurate” temporal fusion.

Table 3.

Comparison of Time-Series Fusion Results.

Table 4 focuses on the semantic and geometric regularity of fusion results. Findings indicate that feature fusion guided by knowledge graphs significantly enhances the consistency of multimodal representations. At the terrain feature level: Although the plain scene inherently mitigated projection distortion caused by terrain relief, the G2 group leveraged surface semantic knowledge to further eliminate local vegetation occlusion and shadow interference, reducing the textural feature error rate from 5.8% to 3.2%. At the model feature level: The system utilized entity classification and topological rules from the knowledge graph to precisely identify grounding components and drive local DEM hollow-out. This avoided the common “penetration and floating” issues found in traditional methods, reducing the geometric feature error rate from 16.5% to 4.2%. At the attribute feature level: Group G2 utilized the BIM model to delineate valid spatial boundaries, directly eliminating interference point clouds (such as scaffolding) located outside the model. This ensured that only genuine bridge tower component point clouds were associated, causing the attribute query error rate to drop drastically from 13.6% to 0.9%. Overall, the feature fusion error rate for multimodal data was reduced by 70.9%, fully validating the core value of knowledge guidance in feature-level disambiguation, alignment, and standardization.

Table 4.

Comparison of Features Fusion Results.

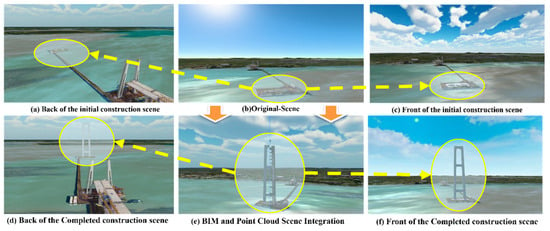

3.4. Twin Scenes Modeling Results and Analysis

The core of digital twin scenes modeling lies in iterative scenes updates [40]. We focused on evaluating the effectiveness and efficiency of updating local scenes models, with the twin modeling results illustrated in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Bridge tower construction scenes modeling effect.

Figure 9b depicts the initial construction scene for the bridge tower, without incorporating the BIM model. Figure 9a and Figure 9b, respectively, depict the initial construction scenes of the bridge tower with the BIM model loaded. Figure 9a shows the rear view, while Figure 9b presents the front view. Figure 9d and Figure 9f correspond to the updated bridge tower construction scenes depicted in Figure 9a and Figure 9f, respectively. Figure 9e illustrates the integration of the BIM model and point cloud within the bridge tower construction scene. In the context of constructing a digital twin for bridge towers, the BIM model of the tower is derived through the integration of surveillance footage, point cloud data, and BIM. Specifically, frame temporal analysis of surveillance video data parses the BIM model of the bridge tower. to determine its state at a specific moment and its dynamic evolution; Multi-period point cloud data is employed to constrain the geometric characteristics of the bridge tower BIM model. The terrain was generated through the integration of DEM with remote sensing imagery. Experimental results demonstrate that this method effectively maintains the spatiotemporal and feature consistency of digital twin scenes. No geometric misalignment or topological anomalies were observed.

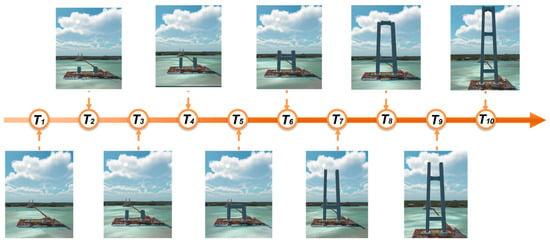

This article outlines two approaches to scene updates: incremental updates and replacement updates. Therefore, we have selected this constructed bridge tower as the subject of our research. Analyze the entire construction process of the bridge tower, from the commencement of pier construction to the completion of the tower structure. During this construction process, updates to the bridge tower columns and the main bridge tower model are incrementally applied over time to the preceding bridge tower model, constituting an incremental update. The internal structures of piers and towers are either cleared or hidden during the update process following the main tower model’s update, constituting a replacement-based update. The specific bridge tower model update time series is shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Construction Process of the Left Tower.

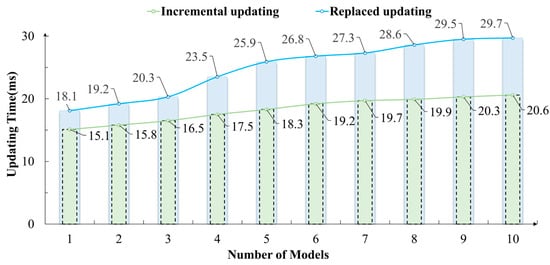

Within the temporal dimension of the bridge tower’s construction process, time point T1 corresponds to the initial state of the bridge tower, at which point only one bridge tower model requires updating; T10 marks the moment when the bridge tower completes its modeling update. This involves incremental updates to ten bridge tower models, alongside replacement updates for ten bridge piers and internal models within the towers. In the temporal dimension of the construction process, both the incremental model and the replacement model incrementally add one model per phase at adjacent time points. During this analysis, we conducted ten randomized experiments simulating updates to the bridge tower construction scene from time zero to time points T1 through T10. Record the total time required for each knowledge graph query and the incremental update and replacement update processes during each experiment, and calculate the average. The results are shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Incremental versus replacement approach for bridge towers.

According to experimental data, the update time for both replacement updates and incremental updates increases linearly with the number of update models. Specifically, the cumulative time for incrementally updating ten models was 29.7 ms. After loading the fifth model, the growth rate gradually slowed. Conversely, the incremental increase in time required for replacement updates is relatively small as the number of models increases. Updating ten models simultaneously via the replacement update method requires 20.6 ms. The time variation at each stage is relatively stable. Both update methods remain below 30 ms, ensuring efficient local scene updates and rapid modeling speeds.

4. Discussion

4.1. Advantages

The advancement of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) necessitates synergistic development with emerging information technologies, alongside actively integrating GIS into mainstream information technologies [41]. In this context, we have innovatively leveraged the advantages of knowledge graph guidance and multimodal data fusion to provide semantic guidance and data support for rapid modeling in digital twin scenes. This approach facilitates the breaking down of barriers between construction logic and spatial modeling, enhancing the efficiency and standardization of digital twin scenes modeling. It provides a reference model for constructing geographical digital twin scenes. Specifically, the method proposed in this paper offers two-tiered advantages over conventional digital twin scenes modeling approaches:

In multimodal data association and fusion, we have pioneered the embedding of structured knowledge within the fusion process. Utilizing a knowledge graph as the semantic hub, we achieve unified guidance and collaborative alignment across five categories of multimodal data: BIM, DEM, imagery, video, and point clouds. Unlike traditional data fusion methods [29,30,31], the approach presented herein provides explicit semantic anchors for multimodal data through predefined event phases, object hierarchies, and spatial topological relationships within knowledge graphs. This effectively circumvents issues arising from modal heterogeneity, such as geometric misalignment, temporal mismatch, and semantic ambiguity, significantly enhancing the standardization and interpretability of fusion outcomes.

In terms of rapid scenes construction and updating, we have moved beyond inefficient traditional approaches such as “full rebuilds” or “manually triggered updates”, establishing a knowledge-driven dynamic modeling mechanism. This mechanism can automatically identify the event status and affected objects corresponding to dynamic data based on the construction logic and temporal rules defined within the knowledge graph, thereby triggering incremental or replacement-based local model updates. Compared to existing digital twin modeling approaches [25,26,27], this method implements a closed-loop process encompassing data ingestion, semantic parsing, model updating, and rule validation, significantly enhancing the real-time responsiveness and modeling consistency of digital twin scenes.

4.2. Limitations and Future Work

By analyzing the Bridge tower Construction scenes Elements and Their Interrelationships, we have constructed a knowledge graph for Bridge tower construction, thereby achieving a structured representation of construction knowledge. This method employs manual processing for knowledge extraction, and there remains scope for improvement in terms of information extraction and knowledge mining efficiency. Future research may incorporate large language models, leveraging their robust natural language processing and knowledge reasoning capabilities to enhance the efficiency of constructing geographical knowledge graphs in complex scenes.

Taking a typical bridge tower construction scene as an example, we explored a rapid modeling approach guided by knowledge graphs and driven by multimodal data fusion, having preliminarily verified the method’s flexibility. Given the multi-source, heterogeneous nature of data required for geographical scenes construction and the challenges in comprehensive data acquisition, we have yet to apply this approach to other geographical scenes. Future work may extend this methodology to other contexts such as tunnel excavation and building construction, thereby further validating its adaptability for digital twin scenes modeling.

In practical applications, modalities such as point clouds and reality capture 3D models often lack explicit IDs. Leveraging the semantic anchor provided by the knowledge graph, we employ a hybrid matching strategy combining “geometric similarity + spatial topological constraints + construction phase consistency” to achieve cross-modal association. Even under noise conditions such as occlusion or point cloud sparsity, the attribute query error rate is significantly reduced, demonstrating the robustness of the method. In extreme cases, such as the complete loss of IDs across all modalities, manual intervention is still required; future work will introduce self-supervised alignment to enhance automation levels.

5. Conclusions

For the typical dynamic geographic scene of bridge tower construction, we propose A knowledge graph-guided and multimodal data fusion-driven rapid modeling method for digital twin scenes. First, we built a knowledge graph for bridge tower construction. This graph contains 570 nodes and 985 relationships, clearly capturing the event logic, object dependencies, and data associations in the construction process. Second, we designed a knowledge-guided multimodal data fusion algorithm. With the help of the knowledge graph, spatial registration accuracy of multimodal data improved by 21.83%, temporal fusion efficiency increased by 65.6%, and feature fusion error rates dropped by 70.9%. Third, we developed a dynamic data-triggered mechanism for rapid scene updates. Local scene updates now take less than 30 ms, enabling millisecond-level dynamic modeling and effectively ensuring spatiotemporal consistency and semantic integrity of the digital twin. Overall, our method efficiently builds high-fidelity, dynamically updated digital twin scenes from multimodal data.

The main contribution of this work is that, for the first time, structured construction knowledge has been integrated into the digital twin modeling process. We established a closed-loop modeling paradigm guided by knowledge graphs and driven by multimodal data fusion. This solves key limitations of traditional methods, such as heavy reliance on manual work, lack of semantic guidance, and poor adaptability to dynamic changes. Our approach shows clear advantages in multimodal data fusion and rapid scene construction and updating, significantly improving both modeling efficiency and standardization. It offers a practical reference for building geographic digital twin scenes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Zhihao Guo; writing—original draft, Yongtao Zhang, Zhihao Guo; data curation, Yongtao Zhang, Yongwei Wang, Jun Zhu, Fanxu Huang, Hao Zhu, Yuan Chen, Yajian Kang; methodology, Yongtao Zhang, Zhihao Guo; software, Yongtao Zhang, Yongwei Wang, Zhihao Guo, Jun Zhu, Fanxu Huang, Hao Zhu, Yuan Chen, Yajian Kang; formal analysis, Yongtao Zhang, Yongwei Wang, Zhihao Guo; investigation, Fanxu Huang, Jun Zhu; validation, Yongtao Zhang. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key R&D Program of China, grant number 2021YFF0500902.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Yongtao Zhang, Yongwei Wang, Hao Zhu and Yuan Chen were employed by the company CCCC Second Harbor Engineering Company Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Zhu, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, Q.; Li, W.; Wu, J.; Guo, Y. A knowledge-guided visualization framework of disaster scenes for helping the public cognize risk information. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2024, 38, 626–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, J.; Wu, J.; Guo, Y.; Huang, F.; Li, J.; Li, W.; Xu, B. Geographic knowledge graph-guided twin modeling method for complex city scenes. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2025, 142, 104757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Zhang, J.; Lian, H.; Ding, Y.; Guo, Y.; You, J.; Chen, P.; Xie, Y. A mobile phone-based multilevel localization framework for field scenes. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2025, 39, 2681–2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, T.; Evangelidis, K.; Kaskalis, T.H.; Evangelidis, G. The Metaverse Is Geospatial: A System Model Architecture Integrating Spatial Computing, Digital Twins, and Virtual Worlds. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2025, 14, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, P.; Zhu, J.; Rao, Y.; Li, W.; Dang, C. A multimodal generative AI-driven 3D geographic scenes reconstruction method. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2025, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalfe, J.; Ellul, C.; Morley, J.; Stoter, J. Characterizing the role of geospatial science in digital twins. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2024, 13, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranatunga, S.; Degrd, R.S.; Onstein, E.; Jetlund, K. Digital twins for geospatial decision-making. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2024, 10, 271–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Wu, J.; Guo, Y.; Dang, P.; Li, W.; Zhang, H. Exploring geospatial digital twins: A novel panorama-based method with enhanced representation of virtual geographic scenes in Virtual Reality (VR). Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2024, 38, 2301–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhu, J.; Fu, L.; Zhu, Q.; Xie, Y.; Hu, Y. An augmented representation method of debris flow scenes to improve public perception. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2021, 35, 1521–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Yue, P.; Shangguan, B.; Gong, J.; Xiang, L.; Lu, B. RTGDC: A real-time ingestion and processing approach in geospatial data cube for digital twin of earth. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2024, 17, 2365386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Zhong, R.Y.; Jiang, Y. Digital twin and its applications in the construction industry: A state-of-art systematic review. Digit. Twin 2025, 2, 2501499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madubuike, O.C.; Anumba, C.J.; Khallaf, R. A review of digital twin applications in construction. J. Inf. Technol. Constr. 2022, 27, 145–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.; Wu, S.; Li, Y.; Guo, Q. Digital twins’ application for geotechnical engineering: A review of current status and future directions in China. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 8229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwer, N.; Schleich, B.; Mathieu, L.; Wartzack, S. Shaping the digital twin for design and production engineering. CIRP Ann. 2017, 66, 141–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinci-Carlavan, G.; Rossit, D.; Toncovich, A. A digital twin for operations management in manufacturing engineering-to-order environments. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2024, 42, 100679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhu, J.; Dang, P.; Wu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Li, W.; Fu, L.; Guo, Y.; You, J. An improved social force model (ISFM)-based crowd evacuation simulation method in virtual reality with a subway fire as a case study. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2023, 16, 1186–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, F.; Gou, H.; Yang, H.; Ni, Y.-Q.; Wang, Y.-W.; Bao, Y. Digital twin-based fatigue life assessment of orthotropic steel bridge decks using inspection robot and deep learning. Autom. Constr. 2025, 172, 106022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Z.; He, W.; Liu, Y. Research on the Digital Twin System for Rotation Construction Monitoring of Cable-Stayed Bridge Based on MBSE. Buildings 2025, 15, 1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yan, J.; Yang, J.; Meng, W.; Chen, S. Two-stage point cloud registration using multi-scale edge convolution for digital twin-based bridge construction progress monitoring. Autom. Constr. 2025, 178, 106415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valinejadshoubi, M.; Sacks, R.; Valdivieso, F.; Corneau-Gauvin, C.; Kaptué, A. Digital twin construction in practice: A case study of closed-loop production control integrating BIM, GIS, and IoT sensors. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2025, 151, 04025102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Sun, C.; Li, Y.; Qi, Z.; Zhang, G. Applications of digital twin technology in construction safety risk management: A literature review. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2025, 32, 3587–3607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaewunruen, S.; Sresakoolchai, J.; Ma, W.; Phil-Ebosie, O. Digital twin aided vulnerability assessment and risk-based maintenance planning of bridge infrastructures exposed to extreme conditions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacks, R.; Brilakis, I.; Pikas, E.; Xie, H.S.; Girolami, M. Construction with digital twin information systems. Data-Centric Eng. 2020, 1, e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, J.; Zhu, J.; Stefanakis, E.; Dang, P.; Wu, J. A fast modeling method for augmented reality dynamic scenes with spatio-temporal semantic constraints. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2025, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.Y.; Fan, X.Q.; Zhang, Q.H.; Wei, B.Y. Construction and Information Interaction Visualization of Digital City Model Based on UAV Oblique Measurement Technology. J. Comput. 2025, 36, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosamo, H.H.; Hosamo, M.H. Digital twin technology for bridge maintenance using 3d laser scanning: A review. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2022, 2022, 2194949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honghong, S.; Gang, Y.; Haijiang, L.; Tian, Z.; Annan, J. Digital twin enhanced BIM to shape full life cycle digital transformation for bridge engineering. Autom. Constr. 2023, 147, 104736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurado, J.M.; López, A.; Pádua, L.; Sousa, J.J. Remote sensing image fusion on 3D scenes: A review of applications for agriculture and forestry. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2022, 112, 102856. [Google Scholar]

- Madichetty, S.; Muthukumarasamy, S.; Jayadev, P. Multi-modal classification of Twitter data during disasters for humanitarian response. J. Ambient. Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2021, 12, 10223–10237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Wang, Z. Multimodal social sensing for the spatio-temporal evolution and assessment of nature disasters. Sensors 2024, 24, 5889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Q.; Zuo, J.; Kang, W.; Ren, M. High-Precision 3D Reconstruction in Complex scenes via Implicit Surface Reconstruction Enhanced by Multi-Sensor Data Fusion. Sensors 2025, 25, 2820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.; Pan, S.; Cambria, E.; Marttinen, P.; Yu, P.S. A survey on knowledge graphs: Representation, acquisition, and applications. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2021, 33, 494–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Xia, F.; Naseriparsa, M.; Osborne, F. Knowledge graphs: Opportunities and challenges. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2023, 56, 13071–13102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, B.; Cheng, J.; Zhao, X.; Duan, Z. Knowledge graph completion: A review. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 192435–192456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Valera-Medina, A. A knowledge graph-supported information fusion approach for multi-faceted conceptual modelling. Inf. Fusion 2024, 101, 101985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Wang, J.; Meng, X.; Liu, H. Analysis of the dynamic response of a long span bridge using GPS/accelerometer/anemometer under typhoon loading. Eng. Struct. 2016, 122, 238–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JTG/T 3650-2020; Technical Specifications for Construction of Highway Bridge and Culverts. Ministry of Transport of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2020.

- Wu, Q.; Zhao, X. A Registration Method Based on Planar Features Between BIM Model and Point Cloud. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2024, 2833, 012016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grodecki, J.; Dial, G. Block adjustment of high-resolution satellite images described by rational polynomials. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 2003, 69, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adu-Amankwa, N.A.N.; Pour Rahimian, F.; Dawood, N.; Park, C. Digital Twins and Blockchain technologies for building lifecycle management. Autom. Constr. 2023, 155, 105064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lü, G.; Chen, M.; Yuan, L.; Zhou, L.; Wen, Y.; Wu, M.; Hu, B.; Yu, Z.; Yue, S.; Sheng, Y. Geographic scenes: A possible foundation for further development of virtual geographic environments. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2018, 11, 356–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the International Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.