Abstract

The Lençóis Maranhenses region, located in the state of Maranhão in northeastern Brazil, constitutes an area that includes a national park and presents extreme physical, geographic and climatic contrasts in addition to economic diversity and emerging tourism. Scattered throughout this portion of the Brazilian territory are local inhabitants whose traditional lifestyles are characterized by agricultural, extractive, fishing and animal husbandry activities. These local residents use guidance systems and mental maps developed through their long history, interaction with nature, and knowledge of the environment in which they live and work. Based on sketches prepared by residents and by Health Agents serving the communities, and with the support of cartographic-based materials produced by the team of the Socioenvironmental Atlas of Lençóis Maranhenses (ASALM, Portuguese abbreviation for Socioenvironmental Atlas of Lençóis Maranhenses), we present a set of digital and interactive cartographic materials that reproduce the movements, uses and practices of the families of these communities as well as the environmental dynamics of this vast region. Such cartography can serve as an instrument of planning, understanding and action, both to safeguard the rights of the local residents and for the handling and management of natural resources. Based on the dialogue between local knowledge and cartography, we present the methods, processes and results of our research project.

1. Introduction

Since ancient times, the map was used to represent inhabited space, to communicate, and to display paths and routes travelled. New developments in cartographic methods and spatial representations, such as geospatial data sets available in web server maps, have made it possible to expand current mapping systems and trends [1]. The capability of superimposing geospatial data from different sources and formats on Geographic Information Systems makes spatial relationships explicit, and helps us understand interdependencies among geographic phenomena. Such cartographic representations, generated in a computational environment combined with human knowledge about these processes, can result in advances in geographic analysis [2].

In this paper we demonstrate the complexity of combining data from different sources and formats, but also the richness of this data for studying the socioenvironmental dynamics of the Lençóis Maranhenses region located in the state of Maranhão in northeastern Brazil [3]. This region, which includes a national park, presents extreme physical, geographic and climatic contrasts, in addition to economic diversity and emerging tourism (see Section 2.1 below). Scattered throughout the territory are several traditional communities whose inhabitants participate in agricultural, extractive, fishing and animal husbandry activities. We are developing a Cybercartographic Atlas, the Socioenvironmental Atlas of Lençóis Maranhenses (ASALM), that aims to present cartography that displays, on the one hand, the environmental dynamics of Lençóis Maranhenses, and, on the other hand, the activities of those living in the region’s traditional communities.

ASALM’s software platform, the Nunaliit Cybercartographic Atlas Framework, is ideal for uniting representations of traditional knowledge, land use and occupation with geospatial data from different sources. Developed to support the explicit demands of cybercartography, Nunaliit is an open-source web-based data management system that uses maps as a unifying framework for connecting information and presenting narratives [4]. Cybercartography was first introduced in 1997 as an approach to cartography that linked theory and practice in an ongoing, iterative feedback loop between cartographic research and production [5,6]. The importance of mapping as a process and the map as a concept and a product was emphasized in the following elements: the multisensory, multimedia and interactive nature of cybercartography; its application to socially relevant topics beyond location finding and the physical environment; its integration into an information/analytical package; and the involvement of teams from different disciplines [6]. The concept of cybercartography has evolved since then with its emphasis on the co-production of knowledge that gives control and voice to local communities and the diversity of their opinions and perspectives [7]. More than simply a web-based technique, cybercartography includes a strong qualitative element that recognizes the importance of societal issues and relationships.

Pyne [8] (pp. 238–239) classifies cybercartographic atlases as a member of the “critical cartography clan,” based on an analysis of the critical cartography literature, e.g., [9,10,11,12], among others. She observes that cybercartography and critical cartography share the following: a concern about adequately reflecting and communicating “experience, sense of place, and diversity in world views in a non-dominatory manner”; the exploration of new ways to both deconstruct and reconstruct maps; the recognition that maps are social constructions that have systematically excluded perspectives which do not align with imperialistic and colonial goals; an awareness of the power of maps to influence people’s world views; and “a preoccupation with contributing to social justice, a broad ontology of mapping, reflexivity and inter-, multi- or transdisciplinary.”

Participatory mapping is an important component of both cybercartography and critical cartography. In ASALM the mental maps of the region sketched by local inhabitants of the Lençóis Maranhenses region are combined with the geoenviormental data collected by members of the research team. Following cybercartographic principles, ASALM brings together researchers in geography, cartography, oceanography and biology with local inhabitants of the Lençóis Maranhenses region to co-produce and share knowledge of this unique and beautiful land.

The Lençóis Maranhenses region presents unique geoenvironmental dynamics, characterized by the presence of extensive dune fields shaped continuously by the action of winds and rainwater [13,14]. There are two distinct seasons, rainy and dry. The trails through the dunes and floodplains are constantly changing, making travel difficult for those who visit Lençóis Maranhenses. However, this difficulty is not experienced by the local inhabitants, who use guidance systems developed from their long history in the region, interaction with nature, and intimate knowledge of the environment in which they live and work. In Section 3 we present in detail the mental maps and native guidance system they have developed through generations of individual and collective memory and experience.

The mental map has been defined as both a concept and a geographical document [15]. Such maps exist only in the memory and spatial knowledge of their creators, yet when transcribed into graphical representations they have been shown to be highly accurate [16]. The centrality of mental maps in representing and preserving traditional knowledge was reported in many diverse cultures. These include knowledge of travel routes by the Inuit in the snow-covered Arctic [17,18], detailed knowledge of the Lough Neagh lake bed by fishermen in Northern Ireland [16], and the spatial knowledge of indigenous tribes in the mountains of Taiwan [19]. The term “memoryscape” has been used to describe the travel routes of the Inuit who follow traditional trails that, like those in Lençóis Maranhenses, physically disappear with changes in weather and seasons but are embedded in the cognitive memory of their users [18]. Such routes incorporate memories of physical territories and people’s relationships with their environment, and are essential for safe and reliable travelling in ever-changing landscapes.

McKenna et al. speculate that an accurate mental map of local ecological knowledge consists of the following characteristics: a relatively homogenous society; local use or exploitation of natural resources (e.g., fisheries, forest products or pasture); inter-generational transmission of knowledge; economic dependence on the resource; and sufficient time for self-correction [16]. The guidance system employed by the local residents of Lençóis Maranhenses (and its surroundings) fulfill all these conditions, as they live in small communities comprised of several close-knit families; their orientation practices are crucial for fishing, subsistence collecting, animal husbandry and tourism (all important sources of income); their routes are transmitted orally through experience; and they have a long history of navigating across their territory.

In ASALM, the information gained from mental maps, sketches and figures will be superimposed on a geospatial database, strengthening the dialogue between local knowledge of orientation and geospatial data collected for cartographic research. Through cartography, the knowledge of native guidance systems will be documented and accessible, in the same way that Aporta’s GPS documented the “ephemeral tracks” left by Inuit hunters [18] (p. 252).

Knowing and mapping the practices developed by the residents of the region of Lençóis Maranhenses—in particular productive activities in the primary sector of the economy, i.e., agriculture, livestock, fishing and plant extraction—is also essential to understanding the impact of socio-spatial transformations that the region has experienced [20,21]. For example, the construction of new state highways connecting municipalities in the Lençóis Maranhenses region has resulted in increasing tourism and urban expansion. In such cases, cartography can serve as an instrument for planning, understanding and action, both to safeguard the rights of local residents and for the handling and management of natural resources.

2. Materials and Methods

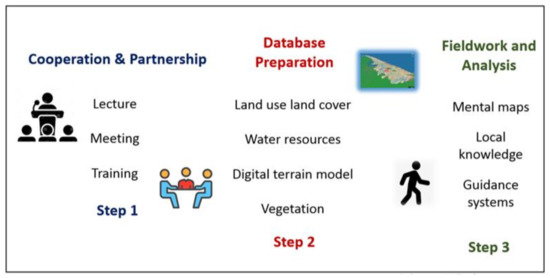

In this section we present the study area (Section 2.1), and the three steps in our research project. Step 1 involved establishing and strengthening relationships and partnerships among project members and institutions. In Step 2 we collected the geospatial data for developing ASALM’s cartographic base. Step 3, as shown in Figure 1, consisted of fieldwork and data analysis. The multidisciplinary perspective and participatory methodology, implemented in cooperative activities between institutions (universities, managing bodies, associations) and local leaders, and through conversations facilitated by ASALM in Step 1, made it possible to collect data and gather knowledge of the traditional ways of life to further the purpose of mapping this extensive and diversified area.

Figure 1.

Steps in the Socioenvironmental Atlas of Lençóis Maranhenses (ASALM) research project.

2.1. Study Area

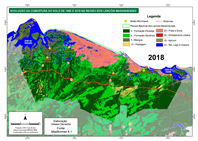

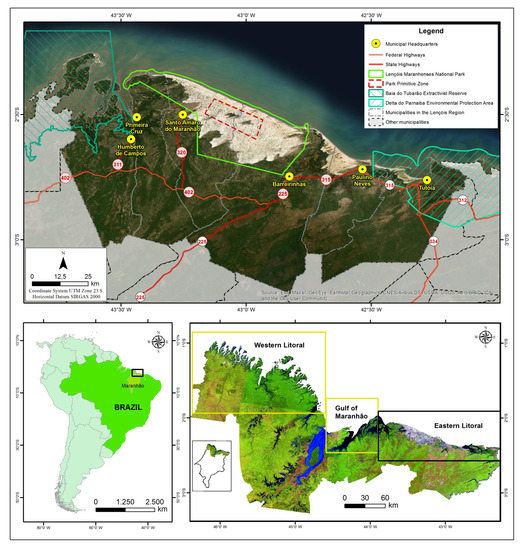

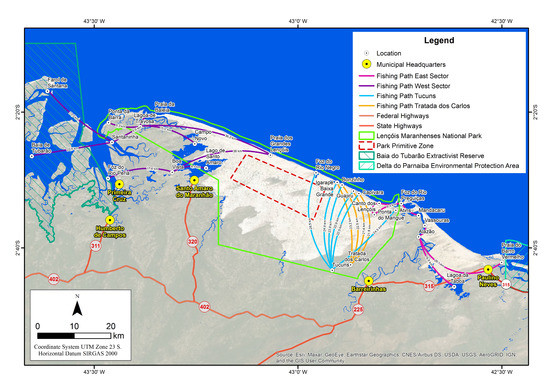

The Lençóis Maranhenses region is located on the east coast of the state of Maranhão in northeastern Brazil. It includes a national park and overlaps with other Conservation Units such as the Extractive Reserve of Tubarão Bay, the Parnaíba Delta Environmental Protection Area and the Pequenos Lençóis Environmental Protection Area (Figure 2). The area presents extreme physical, geographic and climatic contrasts, in addition to economic diversity and emerging tourism. It presents unique geoenvironmental dynamics, with its extensive dune fields shaped continuously by the action of winds and rainwater [13,14,22]. A geologically rare phenomenon, it is the largest recorded area of dunes formed in the active dune field of Quaternary [23,24,25].

Figure 2.

Location of the Lençóis Maranhenses Region.

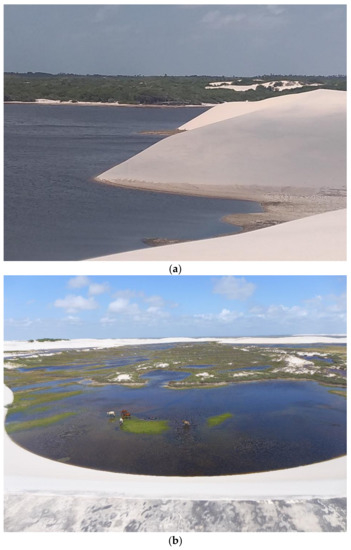

The Lençóis Maranhenses region is characterized by the dynamics of two distinct periods: the rainy season (high rainfall, full lakes) and the dry season (low rainfall, dry or low-water lakes) [22,24,25]. The lakes and watercourses in the fixed dune areas depend almost exclusively on rainfall to sustain their ecosystems. In the interdune areas are vargens, grasslands that are used to feed animals and are important for the physical and economic survival of the local populations (Figure 3). This mosaic of landscapes, in which water fills the interdune depressions at certain times of the year, is exuberant and paradisiacal. The mobile dunes, locally called morrarias, continuously advance inland over the vegetation in a predominantly northeast-southwest direction, and have now reached a distance of approximately 27.5 km from the coast. Morrarias is typically defined as a succession of hills, but in the Lençóis Maranhenses region it applies to sand dunes, including ones covered by vegetation, and even old, consolidated dunes (paleodunes). In addition to perennial and temporary dunes and lagoons, there are strips of straight beach, perennial rivers (Rio Preguiças, Rio Periá), bays, tidal channels, mangroves and islands located in the Extractive Reserve of Tubarão Bay in the western part of the study area.

Figure 3.

(a) Mobile dunes; (b) Animals grazing on the grasslands (vargens).

2.2. The Socioenvironmental Atlas of Lençóis Maranhenses—ASALM

The Socioenvironmental Atlas of Lençóis Maranhenses is a project that originated from a partnership between the Department of Geography at the University of São Paulo, Brazil and the Geomatics and Cartographic Research Centre at Carleton University in Ottawa, Canada. Other partners include the Federal University of Maranhão (UFMA), the Federal Institute of Maranhão (IFMA), and the Department of Geography of Durham University. The project uses traditional cartographic visualization and representation techniques associated with modern data collection and processing systems, but also explores new techniques of cybercartography, specifically the Nunaliit Cybercartographic Atlas Framework [3,26]. The ASALM research team has collected data and generated information that compose the 14 thematic sections of the Atlas. In this article we focus on the following four sections: society and nature; vegetation; land use, coverage and occupation; and cartographic support.

2.2.1. Step 1: Cooperation and Partnership

The objective of the first stage of the project was to establish and strengthen relationships between the institutions, researchers, technicians and students who are involved in or wish to participate in the ASALM project, through meetings, lectures and workshops in Brazil. The following are some highlights from the activities carried out in the first stage: (1) a lecture at the Department of Geography at the Federal University of Maranhão (UFMA), entitled “Conservation Geography: Landscape Approaches,” which marked the opening of ASALM’s activities; (2) a meeting with researchers from the National Center for Research and Conservation of Sociobiodiversity Associated with Traditional Peoples and Communities (CNPT), focusing on data and information from the Extractive Reserve of Tubarão Bay [3,27]; (3) a training seminar on Cybercartography given by research partners from Carleton University, which brought together, in addition to the Maranhão professors collaborating on the project, representatives of Instituto Amares, and graduate students in Geography, Social Sciences, and Oceanography from UFMA, for a total of 40 participants; and (4) a meeting to plan the field stages with the team of researchers and technicians from the University of São Paulo (USP) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

(a)—Lecture at UFMA; (b)—Meeting at CNPT; (c)—Training on the Nunaliit platform; (d)—Meeting at USP.

2.2.2. Step 2: Data Collection and Preparation

In this stage of the project, geospatial data were collected to develop ASALM’s cartographic base. The data collected are being used in the development of both a digital Atlas of Lençóis Maranhenses (ASALM) using the Nunaliit Cybercartographic Atlas Framework and a traditional paperbound atlas with the same name. The data collection process involved travelling by foot or in motorized vehicles during the field trips, and the work of multidisciplinary teams from diverse areas such as geomorphology, biogeography, tourism, anthropology, and cartography. Together, a wealth of images was collected, including maps, videos and hundreds of photos taken from the surface or by using drones.

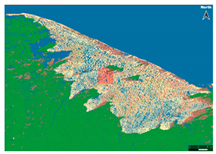

In particular, as shown in Table 1, data were obtained on the following: (1) The geoenvironmental dynamics in periods of high and low rainfall; (2) Classification of Land Use and Coverage; (3) Planialtimetric charts in scale 1:100,000; (4) Mapping of the main sets of geomorphological features in the area; and (5) Overlaying geospatial data on Alos Palsar images (used to extract terrain information).

Table 1.

Surveyed Geospatial Data, source and scale of origin of data.

After preparing the cartographic base, the location of natural resources, equipment and important features for mapping were incorporated into the database, such as restinga (sandbanks) and mangrove areas, the riparian forest, and the locations and uses of the main watercourses. Data were also added on highways [33], municipal boundaries and headquarters [34], villages [35], churches, associations, and the movements of community members for fishing, raising animals, taking care of crops, visiting relatives, and accessing services at municipal offices. Stage 2 was essential so that the surveys and data collected in the field could also be used to validate the data used for the preparation of the cartographic base.

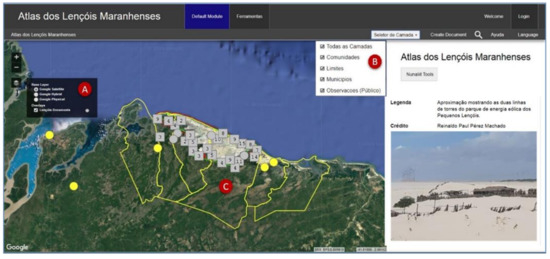

We have developed a prototype of the graphical interface and data layers within the boundaries of the study area, the toponymy of the locations studied, the satellite image background, and the preliminary structure of the Cybercartographic Atlas (The Lençóis Maranhenses Atlas prototype [36] can be found at this link: https://atlas.fflch.usp.br/index.html) (accessed on 31 August 2021). During the first stage of the project it was possible to prepare, in partnership with Carleton University’s Geomatics and Cartographic Research Centre, a layout for the Atlas displaying three types of information (Figure 5). Item A, the Layers Button, allows you to choose the background information base (relief, images, maps); item B allows you to enable layers of information to be overlaid on the background information (Municipal Limits, Location of Communities, points of Observations); and item C shows the Atlas study area where the points visited and monitored by the team are spatialized.

Figure 5.

Layout of the Socioenvironmental Atlas of Lençóis Maranhenses in preparation.

2.2.3. Step 3: Fieldwork and Analysis

In the extensive territory of Lençóis Maranhenses, the national park itself is already 155,000 hectares, according to Decree-Law n. 86.060, of 2 June 1981 [37]. Since certain sections of the research area are difficult to access, joint planning was required of the research teams in order to optimize resources and timing of visits to the traditional communities. The fieldwork took place in the two most distinctive seasonal periods. In March 2019 (winter-rainy season), joint work was undertaken between Brazilian and Canadian researchers, and in November 2019 (summer-dry period) work was carried out by the multidisciplinary team of Brazilian researchers (Figure 6). A subsequent field trip planned for the rainy season in April–May 2020 was postponed due to the coronavirus pandemic.

Figure 6.

(a)—Field activity in the community of Baixa Grande – Primitive Zone of Lençóis Maranhenses National Park. (b)—Production of mandioca flour in the community of Mairizinho, municipality of Primeira Cruz—MA, located in the extreme western part of Lençóis Maranhenses National Park.

During the fieldwork it was possible to visit all the Conservation Units included in ASALM, with a focus on Lençóis Maranhenses National Park and the surrounding area, in particular the Extractive Reserve Tubarão Bay. The fieldwork activities were divided into three routes that made it possible to visit the eastern and western boundaries and the central area mapped in ASALM. The first route started from the municipalities of Humberto de Campos and Primeira Cruz in the west and reached the fishing communities of Mairizinho and Santaninha. The second stage began on the route from the city of Barreirinhas to Atins, navigating the Preguiças river on the east side to Lençóis Maranhenses National Park, and from there following the Grandes Lençóis beach to the primitive area of the park (locality of Baixa Grande) [38], completing the third stage. The objective of this journey was for researchers to gain an understanding of the nuances of the area. As a result of this field activity, several important points for ASALM were located and georeferenced, such as geomorphological features along the Grandes Lençóis beach consisting of sandstones and areas of consolidated outcrops resulting from coastal erosion in recent years.

After a round of conversation with local guides, leaders and community residents, the points that should be photographed and georeferenced using the GPS were defined. Some of these places were only accessible by boat. The locations included sites of common use by the communities, sources of natural resources, and the main trails and routes used by local residents in different seasons. These were all important data for cartography and to understand the native guidance system of the Lençóis Maranhenses region (Figure 7). In the next section we discuss the results of the fieldwork sessions, focusing on the navigation system used by the local residents in defining their routes of travel in their vast region.

Figure 7.

(a) Resident of the community of Betânia, Santo Amaro—MA drawing the mental map of the trails he uses. (b) Roundtable with community members and guides to introduce the ASALM project.

3. Results

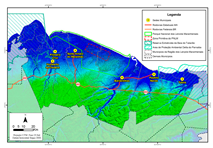

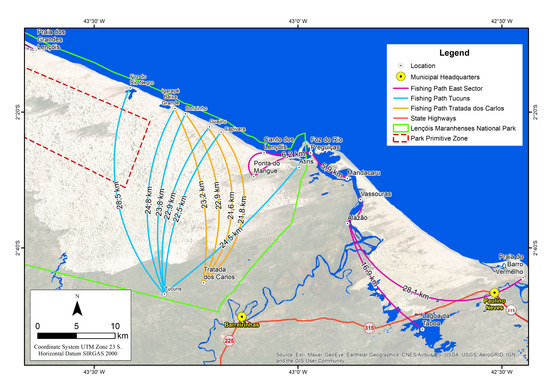

After walking along the trails, visiting workplaces, and mapping areas of common use with the availability of natural resources, the main routes of movement in the Lençóis Maranhenses region were defined. These routes are used by local residents for performing activities such as fishing, raising animals, taking care of crops, visiting relatives, shopping and accessing municipal services. Figure 8 shows the fishing paths in four sectors of Lençóis Maranhenses.

Figure 8.

Travelling paths are used by the local inhabitants for various activities.

Navigating in the mobile dune fields [38] and surrounding vegetation of the Lençóis Maranhenses region is not an easy task, especially for those who are not familiar with the landscape of this fully protected conservation unit. The local residents have their specific routes, travelling on land by foot or in pickup trucks and tractors, and crossing bodies of water by boat and speedboat. Visiting these places outside the season in which they are used is important to establish the movement flows and practices associated with each time of year [20]. Due to their familiarity with the Park’s environment resulting from their economy-based activities such as fishing [39,40,41] and animal husbandry [42,43], the local inhabitants have developed their own sophisticated guidance system. In this section we describe and illustrate the particular forms of guidance, defined here as the “Native Guidance System”, used by the residents of traditional communities that historically live and work in Lençóis Maranhenses National Park (PNLM). The complexity of this native knowledge deserves to be highlighted because it is activated in an environment that is subject to constant ecological and seasonal changes.

The local residents’ historical relationship with the environment in which they reside and work has allowed the families of traditional communities in PNLM to develop and consolidate their knowledge and skills. Such knowledge is associated, for example, with the links between the cycles of nature and the organization of social and economic life, as well as with the ability to navigate in this vast region. The action of winds and rainfall, and the positions of the sun, stars and other celestial bodies are factors in the organization of these forms of knowledge, which allow the local residents to conduct their work-related activities and also travel to communities located far from their homes.

In order to discuss native guidance systems in the PNLM, we must consider the relationship between culture and nature [44], that is, the interaction between humans and the biophysical environment responsible for the families’ ways of life. The relationship between the environmental hyperdynamics of PNLM and the social dynamics of families living in the communities in the park also need to be considered. By “environmental hyperdynamics” we mean the constant transformations in the landscape of the PNLM environments caused by the action of winds, dune movement and rainfall. The combination of these factors, seasonally or over the years, allows for continuous changes in the appearance of the dunes (shape and size), in the diversion of river courses, in the burial of vegetation and houses, in the formation of lakes with periods of high-water concentration and others of drought. PNLM’s traditional communities, in their social dynamics, have always found cultural responses to accompany these constant changes in the landscape.

The native guidance systems are structured around different subsystems, each organized by elements such as the sun, moon, stars, natural accidents, wind direction, and even plant and fruit odors. The senses play a crucial role: vision allows the identification of natural accidents (dunes) and celestial bodies (sun, moon, and stars), and the sense of smell allows one to perceive smells of native plants and fruits such as mirim and murici and water containing decomposing vegetation. Mirim and murici are typical fruit plants of the Cerrado biome that are important for the food security of residents of traditional communities. In the Lençóis region, they are found predominantly in the Restinga vegetation. Appreciated for their citrus flavor, they are used in local cuisine, in jams, juices, and ice cream. The local inhabitants exhibit a hyperawareness of tactile senses. For example, they use parts of their bodies to feel the action of the winds and help identify the direction they should follow. Where they feel the wind—on the front or side of the face, or on the back of the head—indicates the orientation of the destination, whether when travelling to other locations or to places where tourists’ attractions are located.

The sun is also used as a guide in their navigation system. The position of the sun in relation to the body—above the head, right shoulder, left shoulder—indicates the orientation of the destination, depending on the time of day. Like the sun, the stars and the moon—and their respective phases—are used to guide travel at night. There are some celestial bodies that are used by the natives as an orientation reference, such as the Dalva star, and the Seven Sisters and Southern Cross constellations.

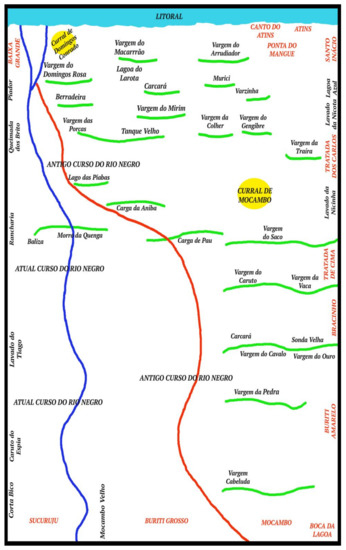

In terms of location knowledge, to the inhabitants who live and work in PNLM, what would be an unknown world to an outside observer is remarkably familiar, as they operate within two dimensions: geographic volume and mental volume. Marcel Mauss borrows these two notions from Ratzel: “We know what Ratzel called the geographic volume and mental volume of societies. The geographic volume is the spatial extent actually occupied by the society in question; the mental volume is the geographical area that it manages to cover with the thought” [44,45]). The entire extent of the Park used in the local residents’ activities, notably animal husbandry and fishing, is entrenched in their minds from their mental maps of the natural elements and environments that make up the landscape. Such mapping is carried out through naming processes used to identify features such as vargens (grasslands/pastures), lagoas (lakes), morros (hills/dunes), lavados (washed), córregos (creeks), and praias (beaches) (lavados are tide plains, with silt and clay surfaces, salty or brackish, without vegetation, where in the past salt was produced. When these areas have vegetation, rainwater, river, or groundwater, they are called “banhados” (wetlands)). Their naming of such features reinforcess their perceptive awareness of both their extensive territory and the location references that do not require sophisticated technological mapping and guidance systems (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Native inhabitant’s mental map of a region of Lençóis Maranhenses National Park. In this mental map, Mr Inácio, 75 years old, indicates the vargens (pasture areas for goats and sheep—in green), the old and current courses of the Rio Negro (red and blue, respectively), the layout of corrals (in yellow) used in animal husbandry activities, and the arrangement of some traditional communities, highlighted in red font. Created by Mr. Inácio, from Mocambo. Reproduced by Benedito Souza Filho.

Despite undergoing modifications, some dunes, because they are higher, act as navigational aids for local residents who work as tour guides. Such dunes are used as reference points for localization by the guides when leading tourists to natural attractions in PNLM.

Familiarity with their environment has allowed the residents of the PNLM communities to develop ways to survive in this vast region when carrying out their activities, such as digging small holes in the sand to obtain water to drink; using dried cattle feces to make a fire to prepare food; and digging holes in the so-called ribs of the hills (the steepest and frontmost part of the dunes) to shelter from the rains.

Native guidance systems are related to the families’ way of life and their economic activities, especially the raising of animals (goats, cattle and sheep) and fishing (fresh and saltwater. Saltwater fishing is carried out on the beaches located on the 70 km-wide coastal strip of PNLM. Freshwater fishing is carried out in seasonal and perennial lakes and also in rivers, wells and weirs. (For more details on fishing activities, see [39,40].) Such activities, carried out in different environments and far from their homes, allowed the local inhabitants to develop forms of guidance that combine knowledge about relief (identification of dunes and vargens), astronomy (orientation using the sun and stars), and wind movement in winter and summer and are still used today.

In an environment subject to constant changes, activities such as animal husbandry and fishing involve a sophisticated guidance system used by people from different parts of the Park. Those who are dedicated to raising animals or fishing, in constant contact with the natural spaces where these activities are carried out, operate with elements of native cartography such as those found in the morrarias (sand dunes) or on the coast.

Fishing is an activity developed in several places in the study area, even populations that reside in areas farthest from the sea. Around the Conservation Units, in particular PNLM and the Preguiças River Environmental Protection Area, the local residents fish in the sea on a seasonal basis, i.e., during the rainy season when there is a greater abundance of fish in the ocean waters. To carry out their fishing activities, they install themselves in small “ranchos” huts built on the Grandes Lençóis beach and along the mouth of the Preguiças River (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

(a) Fishermen in activity at Lençóis Maranhenses beach; (b) Support ranch on Grandes Lençóis beach; the format, type of deck and position of the ranch considers the direction of the winds, solar incidence and thermal comfort, in an environment with temperatures above 40 °C.

Using their native guidance system, residents of communities far from the sea are able to travel through the dune fields and arrive precisely at certain beaches located about a 4- or 5-h walk away (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Enlarged section of Figure 7 showing the travelling paths (distances and times) used by the local inhabitants to fish on the coast.

Seasonality is an important aspect of native guidance systems. The features of the Park’s environment change in the summer (June to December) and winter (January to May) periods. The knowledge of the local inhabitants helps them find cultural solutions that enable them to continue living in a region with constant changes in the landscape.

The social life of the local residents adapts to the changing conditions during periods of rain and drought, and activities are carried out according to the changes observed in the environment. This is because “the movement that animates society is synchronic to that of environmental life” [28]. In Lençóis Maranhenses National Park, a vast region subject to constant transformations, native guidance systems play a decisive role in the social and economic organization of local families.

4. Discussion

Local residents of the Lençóis Maranhenses Region have developed native guidance systems that allow them to manage and thrive in the intense environmental dynamics of their territory. They constantly update their mental maps according to the seasons. The mapping of these paths helps us understand their use and occupation of this region, including how, where and when they develop their activities, in addition to demonstrating the rich local knowledge acquired through interactions with the elements of nature.

It is impossible not to associate the ancestral survival methods and forms of guidance of the Lençóis Maranhenses residents with those living in extreme weather conditions in other parts of the world, such as the Tuaregs in the Sahara Desert [46] and the Inuit who inhabit the vast territories of northern Canada [17,18,47]. In all these cases, the seemingly barren landscape of sand or snow consists of networks of “physically ephemeral” trails that are not permanent features of the landscape but exist in people’s memories and experiences [47]. This shared local knowledge, passed down through the generations, allows the same routes to be traced consistently every year despite seasonal and ecological changes to the environment. For the local residents of Lençóis Maranhenses, their landscape is transformed in the dry and rainy seasons, while for the Inuit in the Arctic, winds, blizzards and seasonal changes in snow and ice conditions are responsible for the transcience of their trails.

To navigate through terrain with no permanent travel routes, local inhabitants use landscape features prevalent in their environment as navigational aids. These include the tall dunes in Lençóis Maranhenses, shore profiles, hills, and river bends in the Arctic, or mountain ranges, pastures and water sources in the Sahara Desert. Another commonality among the native inhabitants of such environments is the use of the sun’s position as a point of reference during the day, and of stars and other celestial bodies at night. The feel and direction of winds are also important for spatial orientation.

Figure 9 above shows the place names that are used by the local inhabitants of Lençóis Maranhenses to identify landscape features. Local place names are a crucial component of Inuit navigation as well, as they are used extensively for describing travel routes. Aporta observes that “Inuit trails are connected to a sequence of place names” [47]. Like the Portuguese place names in Figure 9, Inuit place names are associated with topographic features such as rivers and lakes, valleys and hills, rocks, bays, and ice ridges, as well as identifying places for hunting and fishing, and where plants and berries may be found.

As shown in Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9 above, in the current ASALM project, the activities and movements of the local inhabitants of Lençóis Maranhenses are being documented in digital maps. Through our research we know that groups of local residents leave their fixed homes to engage in fishing activities on the coast during the rainy season, when traditional activities are reduced and fishing productivity is higher. At the end of this period they return to their homes and continue their usual activities, demonstrating patterns of transhumance (i.e., seasonally moving livestock to various grazing grounds) rather than nomadism, as sometimes claimed by the media. The use of geoprocessing techniques in the treatment of data collected in the field, combined with the information collected by ASALM and mental maps, show that the activities of the local residents create a constant and complex flow of people, vehicles and animals. Moreover, depending on the time of year, accessibility conditions, and availability of natural resources, some sectors of the Lençóis Maranhenses region are utilized more than others. Improving studies on the dynamics of the flow and use of natural resources, and the impact of projects such as the installation of wind towers, power lines, solar energy plants, new roads, and resorts will help us understand the implications of these factors for the environment and for the social life of those who live and work in that area.

Knowing and mapping the practices developed by the residents of Lençóis Maranhenses is essential for understanding the impact of socio-spatial transformations [39] that the region has experienced. Currently, some residents also work as tour guides, conducting walking tours with individuals or small groups of tourists, guiding them through areas previously used only by local residents. The ecological impact of vehicles like quadricycles, pickup trucks and motorcycles on these trails needs to be studied [41]. With the construction of new state highways connecting municipalities in the Lençóis Maranhenses region (e.g., the MA-315 and MA-320), the number of tourists is growing, and urban expansion in the municipal areas is clearly on the rise. In addressing such issues, cartography can serve as an instrument for planning, understanding and action, both to safeguard the rights of local residents and for the handling and management of natural resources.

It should be mentioned that this situation changed dramatically during the coronavirus pandemic, especially in the initial period of March–July of 2020. Many of the hotels, posadas, and restaurants were forced to close, with some never reopening. The Brazilian government’s Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade (ICMBio) officially closed the National Park to the public for several months. These circumstances so greatly impacted the towns, citizens, and local inhabitants of the Lençóis Maranhenses region that another section will be added to ASALM to document this dark period. In this way, ASALM is holding true to the principles of cybercartography, defined in part as “the application of location-based technologies to the analysis and understanding of issues of importance to society” [7] (p. 4).

5. Conclusions

Built on the principles of cybercartography, ASALM’s goal is to unite scientific geoenvironmental data and mental representations of local residents’ orientation systems to provide a comprehensive view of the geographical, environmental and social conditions of the Lençóis Maranhenses region. Spatializing information such as areas of natural resources and traditionally used routes will make it possible to estimate the areas of common resource use and the directions and intensity of the flow of people, enabling effective planning and implementation of public policies in the Lençóis region. Future plans include the development of interactive tools to capture geolocation data on cell phones, so that local residents can participate in collecting data that will be of benefit to them. A mobile version of ASALM would also allow communities with no internet service to access maps and information on the regions where they live and work. As traditional cultures and knowledge worldwide become increasingly threatened with extinction by the dominant nation-states in which they live, we hope that the cybercartographic version of ASALM will contribute to the digital inclusion of local communities, providing a platform for the inhabitants of Lençóis Maranhenses to preserve their local knowledge of navigation, ecology and resources. It remains to be seen, though, whether, or how, local communities will embrace new technology as they strive to survive in a world of environmental and social change.

Furthermore, we hope that the methodology of developing both the cybercartographic and traditional printed versions of the Socioenvironmental Atlas of the Lençóis Maranhenses could be applied to other socially and environmentally endangered regions in Brazil, in partnership with other states and universities throughout the country.

Supplementary Materials

The following figures from Table 1 are available in high resolution online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijgi10110755/s1, Land Use and Coverage; Geomorphological Features Map; Alos Palsar Mosaic.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization—Benedito Souza Filho, Reinaldo Paul Pérez Machado, Kumiko Murasugi, Ulisses Denache Vieira Souza; Methodology—Benedito Souza Filho, Reinaldo Paul Pérez Machado, Kumiko Murasugi; Software—Ulisses Denache Vieira Souza; Validation—Kumiko Murasugi, Reinaldo Paul Pérez Machado; Formal analysis—Benedito Souza Filho, Reinaldo Paul Pérez Machado, Kumiko Murasugi; Investigation—Benedito Souza Filho, Pérez Machado, Kumiko Murasugi, Ulisses Denache Vieira Souza; Data curation—Benedito Souza Filho, Ulisses Denache Vieira Souza; Writing—original draft preparation—Benedito Souza Filho, Reinaldo Paul Pérez Machado, Kumiko Murasugi, Ulisses Denache Vieira Souza; Writing—review and editing—Benedito Souza Filho, Reinaldo Paul Pérez Machado, Kumiko Murasugi, Ulisses Denache Vieira Souza; Visualization—Reinaldo Paul Pérez Machado, Ulisses Denache Vieira Souza; Supervision—Reinaldo Paul Pérez Machado, Kumiko Murasugi; Project administration—Reinaldo Paul Pérez Machado; Resources—Benedito Souza Filho, Reinaldo Paul Pérez Machado, Ulisses Denache Vieira Souza; Funding acquisition—Benedito Souza Filho, Reinaldo Paul Pérez Machado. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Grant 17/26794-4, São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP); Grant 02731/18, Maranhão Research Foundation (FAPEMA).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Group of Rural and Urban Studies—GERUR of the Federal University of Maranhão for providing data and records from its database. We are also grateful to Fraser Taylor, Director of the Geomatics and Cartographic Research Centre (GCRC), Department of Geography and Environmental Studies, Carleton University, and Amos Hayes, GCRC’s Technical Manager, for their leadership and expertise in cybercartographic methods and analyses. We are thankful as well to Alexandre de Castro Santos Pinto for his aid and technical support on digital cartography.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kraak, M.J.; Ormeling, F. Cartography: Visualization of Geospatial Data, 4th ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020; p. 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacEachren, A.M. Cartography and GIS: Facilitating Collaboration. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2000, 24, 445–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Machado, R.P.; Souza, U.D.V. Chapter 20—The potential of Cybercartography in Brazil. In Further Developments in the Theory and Practice of Cybercartography: International Dimensions anda Language Mapping; Fraser, T., Erik, A., Kumiko, M., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; Volume 9, pp. 349–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.; Taylor, D.R.F. Developments in the Nunaliit Cybercartographic Atlas Framework. In Further Developments in the Theory and Practice of Cybercartography, 3rd ed.; Taylor, D.R.F., Anonby, E., Murasugi, K., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 205–218. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, D.R.F.; Ottoson, L. (Eds.) Maps and Mapping in the Information Era. In Proceedings of the 18th International Cartographic Conference, Stockholm, Sweden, 23–27 June 1997; Volume 1, pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, D.R.F. Cybercartography: Theory and Practice; Elsevier: Boston, UK, 2005; p. 574. ISBN 044451. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, D.R.F. Cybercartography revisited. In Further Developments in the Theory and Practice of Cybercartography, 3rd ed.; Taylor, D.R.F., Anonby, E., Murasugi, K., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- Pyne, S. Cybercartography and the critical cartography clan. In Further Developments in the Theory and Practice of Cybercartography, 3rd ed.; Taylor, D.R.F., Anonby, E., Murasugi, K., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 219–244. [Google Scholar]

- Crampton, J.; Krygier, J. An introduction to critical cartography. ACME 2006, 4, 11–33. [Google Scholar]

- Harley, B. The New Nature of Maps: Essays in the History of Cartography; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins, C. Cartography: Mapping theory. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2003, 27, 241–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A. Critical cartography 2.0: From ‘participatory mapping’ to authored visualizations of power and people. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 142, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna, M.C.M.; Parteli, E.J.R.; Durán, O.; Hermann, H.J. Model for the genesis of coastal dune fields with vegetation. Geomorphology 2011, 129, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna, M.C.M.; Parteli, E.J.R.; Durán, O.; Hermann, H.J. Model for a dune field with an exposed water table. Geomorphology 2012, 159–160, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Machado, R.P. New approaches in geography supported by geographical information technologies. Geografia 2014, Cartogeo Special Volume, 203–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenna, J.; Quinn, R.D.; Donnelly, D.J.; Cooper, J.; Andrew, G. Accurate mental maps as an aspect of local ecological knowledge (LEK): A case study from Lough Neagh, Northern Ireland. Ecol. Soc. 2008, 13. Available online: https://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol13/iss1/art13/ (accessed on 31 August 2021). [CrossRef]

- Aporta, C. Routes, trails and tracks: Trail breaking among the Inuit of Igloolik. Études Inuit Studies 2004, 28, 9–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aporta, C. From Inuit wayfinding to the Google World: Living within an ecology of technologies. In Nomadic and Indigenous Spaces: Productions and Cognitions; Migglebrink, J., Habeck, J.O., Koch, P., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 247–258. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, B.-W.; Lo, Y.-C. The spatial knowledge of indigenous people in mountainous environments: A case study of three Taiwanese indigenous tribes. Geogr. Rev. 2013, 103, 390–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’antona, Á.d.O. O verão, o Inverno e o Inverso: Lençóis Maranhenses, Imagens; Edições IBAMA: Brasília, Brazil, 2002; p. 180. [Google Scholar]

- Feitosa, A.C. Lençóis Maranhenses: Paisagem exótica—Deserto na Mídia. In Proceedings of the Anais do XI Simpósio Brasileiro de Geografia Física Aplicada, São Paulo, Brazil, 5–9 September 2005; 2005; pp. 5686–5694. [Google Scholar]

- Le Saint, T.; Santos, A.L.S.; Pérez Machado, R.P.; Kawakubo, F.S.; Santos, T.J.A.; Betbeder, J.; Arvor, D.; Souza, U.D.V. Monitoring The Dynamics Of Interdunal Ponds in The Lencois Maranhenses National Park, Brazil. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium IGARSS, Brussels, Belgium, 11–16 July 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves, R.A. Contribuição ao Mapeamento Geológico e Geomorfológico dos Depósitos eólicos da Planície Costeira do Maranhão: Região de Barreirinhas e Rio Novo—Lençóis Maranhenses—MA—Brasil. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil, 1997; p. 235. [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves, R.A.; Lehugeur, L.G.O.; Castro, J.W.A.; Pedroto, A.E.S. Classificação das Feições Eólicas dos Lençóis Maranhenses—Maranhão—Brasil. Mercator 2003, 3, 99–113. [Google Scholar]

- Giannini, P.C.F.; Assine, M.L.; Barbosa, L.M.; Barreto, A.M.F.; Carvalho, A.M.; Sales, V.C.; Maia, L.P.; Peulvast Martinho, C.T.; Tomazelli, L.J. Paleodunas e dunas ativas. In Quaternário do Brasil; Celia, R.d.G., Ed.; Holos Editora: Ribeirão Preto, Brazil, 2005; p. 382. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, D.R.F.; Caquard, S. Cybercartography: Maps and mapping in the information Era. Cartographica 2006, 41, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SOARES, A.K.A. Estudo Socioambiental da Reserva Extrativista da Baia de Tubarão; CNPT/ICMBio: São Luís, Brazil, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- USGS. Landsat 8 Surface Reflectance Tier 1. Available online: https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/ (accessed on 10 June 2020).

- Mapbiomas Project. Collection 5.0 of the Annual Series of Land Use and Coverage Maps of Brazil. Available online: https://mapbiomas.org/o-projeto (accessed on 8 June 2020).

- Brazilian Army Geographic Database (BDGEx). Available online: https://bdgex.eb.mil.br/bdgexapp (accessed on 15 March 2020).

- Geomorphological Map of ASALM. 2020; in preparation.

- EarthData. Available online: https://asf.alaska.edu/ (accessed on 10 April 2020).

- VGEO. Visualizador de Informações Geográficas do Departamento Nacional de Infraestrutura de Transportes (DNIT). 2020. Available online: http://servicos.dnit.gov.br/vgeo/ (accessed on 15 May 2020).

- IBGE. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Available online: https://www.ibge.gov.br/geociencias/downloads-geociencias.html (accessed on 15 March 2020).

- CPRM. Atlas Digital dos Recursos Hídricos Subterrâneos—Maranhão. Available online: http://www.cprm.gov.br/publique/Hidrologia/Estudos-Hidrologicos-e-Hidrogeologicos/Maranhao---Atlas-Digital-dos-Recursos-Hidricos-Subterraneos-3107.html (accessed on 30 April 2021).

- The Lençóis Maranhenses Atlas Prototype. Available online: https://atlas.fflch.usp.br/index.html (accessed on 31 August 2021).

- Brasil. Decreto Federal n. 86.060, de 02 de Junho de 1981. Available online: https://www2.camara.leg.br/legin/fed/decret/1980-1987/decreto-86060-2-junho-1981-435499-publicacaooriginal-1-pe.html (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- Brasil. Instituto Brasileiro do Meio Ambiente e dos Recursos Naturais Renováveis—IBAMA. Plano de Manejo do Parque Nacional dos Lençóis Maranhenses. IBAMA/LABOHIDRO, Brasília. 2003. Available online: https://www.icmbio.gov.br/parnalencoismaranhenses/planos-de-manejo.html (accessed on 20 February 2021).

- Santos, L.C.V.S. A Participação das Mulheres na Pesca Artesanal no Parque Nacional dos Lençóis Maranhenses: O Caso da Mariscagem em Atins; Monografia; Universidade Federal do Maranhão: São Luís, Brazil, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mendes, D.P. Entre o Inverso e o Verão: Comunidades Tradicionais, pesca Artesanal e Uso de Recursos Comuns no Parque Nacional dos Lençóis Maranhenses; Dissertação; Universidade Federal do Maranhão: São Luís, Brazil, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Souza, F.B. Comunidades tradicionais e formas de interação com a natureza: A relação entre humanos e não humanos no Parque Nacional dos Lençóis Maranhenses. In Problema Ambiental: Naturezas e Sujeitos em Conflito; Shiraishi, N.J., Lima, R.M., Soares, A.P.A., Souza, F.B., Eds.; Editora da Universidade Federal do Maranhão: São Luís, Brazil, 2019; pp. 21–41. [Google Scholar]

- Cutrim, R.R. Vargens, Vaqueiros e Morrarias: A Criação de Animais no Parque Nacional dos Lençóis Maranhenses; Monografia; Universidade Federal do Maranhão: São Luís, Brazil, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Descola, P. Outras Naturezas, Outras Culturas; Editora: São Paulo, Brazil, 2013; Volume 34. [Google Scholar]

- Mauss, M. Ensaio sobre as variações sazonais das sociedades esquimós. In Sociologia e Antropologia; Casac & Naify: São Paulo, Brazil, 2003; pp. 367–396. [Google Scholar]

- Campos, D.V.L. A Morraria Anda Demais: Modalidades de Interação entre Humanos e Ambiente no Parque Nacional dos Lençóis Maranhenses; Monografia; Universidade Federal do Maranhão: São Luís, Brazil, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Passon, J.; Braun, K. Navigating and mapping the “white spot”. In Across the Sahara Desert; Braun, K., Passon, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aporta, C. The trail as home: Inuit and their Pan-Arctic network of routes. Hum. Ecol. 2009, 37, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).