Abstract

New technologies have allowed traditional map production criteria to be modified or even subverted. Starting from the communication sciences—journalism in particular—and digital humanities via the history of communication, we show how to use interactive digital maps for the production and publication of knowledge through and/or for participation. Firstly, we establish the theoretical-conceptual framework necessary to base the practices, dividing the elements into three areas: interactive maps and knowledge production (decentralization, pluralization, reticularization, and humanization), maps as instruments to promote political and social participation (egalitarianism, horizontality, and criticism), and maps as instruments for the visualization of data that favors the user experience (interactivity, multimediality, reticularity of reading, and participation). Next, we present two cases that we developed to put into practice the theoretical concepts that we established: the Mapa Infoparticipa (Infoparticipa Map), which shows the results of the evaluation of the transparency of public administrations, and the Ciutadania Plural (Plural Citizenship) web platform for the production of social knowledge about the past and the present. This theoretical and practical model shows the possibilities of interactive maps as tools to promote political participation and as instruments for the construction of social knowledge in a collaborative, participatory, networked way.

1. Introduction

The mapping of states began in the 16th century. However, as José María Perceval explains, “The map is not a description of reality. Rather, it imposes itself on reality, it aims to dominate it at the service of those who order it” [1]. Bringing together works by authors, such as Buisseret [2], Monmonier [3], Koyré [4], and Todorov [5], Perceval recalls that cartography was developed for military, fiscal, and navigation uses, giving way to a new concept of the world promoted by monarchical states. At that time, the medieval idea of Christianity, as a territorial reference, was transformed into a geographical reality: Europe. Maps replaced fantastical stories, being used for administration, mapping roads, resources, properties, etc. The printing press brought these new representations to the public, changing their vision of the world, offering an image that appeared to be an immovable technical-scientific production. Nevertheless, as Brian Harley [6] showed, the rules of map production respond to cultural models and criteria, to a discourse of knowledge representation that requires selecting information and therefore omitting other information, simplifying, classifying, and creating hierarchies and symbols for subjective purposes.

Maps have thus traditionally been the result of power relations, being used to differentiate and separate territories that comprise an exclusive “we”. Mezzadra and Neilson [7] consider that the first modern maps already territorialized identity, establishing cognitive boundaries. Clearly, these borders are also physical and, as we see today, sometimes established through walls or fences that identify abstract groups located beyond those limits as dangerous [8]. The border thus becomes a space of struggle, of exclusion, that coordinates economic and population flows [9]. At the same time, deportations, forced exiles, “relocated lives” (such as the provision of telematic services from the East to professionals who work in the West), and also tourist flows coexist, although these produce an equally colonial map [10].

In contrast, here we outline the theoretical and practical foundation for the design and development of interactive maps for the collaborative production of knowledge and for socio-political participation from a perspective we refer to as plural humanism. Both aspects (theory and practice) are the result of a long research process in which linked projects provided reciprocal feedback until reaching the formulation presented here.

Firstly, we take a theoretical approach by considering the two fields from which we start: (I) communication sciences and journalism as a professional practice and social institution within the framework of these disciplines; and (II) the digital humanities, which we specifically address from the history of communication. From these perspectives, we establish common and complementary elements that lead to a transdisciplinary formulation.

Secondly, we developed the Mapa Infoparticipa (Infoparticipa Map) [11] and the Ciutadania Plural (Plural Citizenship) [12] web platforms. The main tool of the former is a map that represents the results of the evaluation of the transparency of public administrations and other private organizations. It is an instrument conceptualized for political intervention and promoting citizen participation in the monitoring and control of the activity of the governments of public administrations. The latter is a platform that was developed for the construction of knowledge regarding the past and present from a decentralized, networked, collaborative paradigm, relating the local with the global and the personal with the collective. This involved relating three coordinates: space, for which an interactive map is used; time, which is determined by a timeline; and theme, for which an appropriate theming is presented for the proposed purposes.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Maps as Instruments of Multimedia Digital Social Communication

Maps are interconnected in multimedia online digital social communication systems with other interactive textual, graphic, audiovisual, and hybrid resources for the publication of news and other informative genres in such a way that the contents are made comprehensible for a heterogeneous audience and that, as Link, Henke, and Möhring [13] point out, improve the user experience. In this context, new online interactive multidirectional media have already largely replaced the hierarchical unidirectional mass media and are changing the principles for the production of effective social communication [14].

The first infographics to appear in the press were maps [15], and since then, they have been used to complement, explain, or report the news, contributing at the same time to the geographical knowledge of users [16]. Their importance in the media has grown over time, especially in terms of the paradigms of online digital communication and the construction of information in a decentralized cooperative way, which reveal new functions and possibilities. Thus, maps are used to georeference data, contextualizing them, and giving them meaning in the narrative dimension, such that the Earth Journalism Network (https://earthjournalism.net/, accessed on 1 July 2021 ) is using the term GeoJournalism in projects related to the environment.

However, this is not the only theme to centralize such practices. Platforms that distribute local or hyperlocal content based on georeferencing are also multiplying, such as News Break in the USA (https://www.newsbreak.com, accessed on 1 July 2021) or Locationews in Finland (https://locationews.com, accessed on 1 July 2021) [17], as well as information on political or social analysis. The coronavirus crisis has clearly demonstrated this trend, flooding the home pages of digital newspapers and their special sections with graphics and maps to show the evolution of the pandemic.

It is especially interesting to note that the use of maps in journalistic or communicational activity in a broad sense alters the linear reading and the hierarchical ordering of contents traditionally established by the producers of the information. The reading order of a map is established by the interests or preferences of the users. However, interactive digital maps can incorporate audiovisual resources that in traditional printed journalistic documents can only be published in a disaggregated form. In other words, this information forms part of the interactive map itself, being integrated into the locations to offer more information, complement meanings, and enrich the user experience.

New tools that allow the representation of data in the form of graphs and maps without the need for programming (such as Flourish, Tableau, DataWrapper, Qgis, Mapbox, Carto, or the tools of Google, My Maps, and Google Earth Studio, among others) are already commonly used in journalism, not only in data journalism in particular but also in the so-called legacy media, in native digital media [18], or in hybrid journalistic formats [19].

Nowadays, maps are essential tools that journalists and communicators must be knowledgeable of. They arouse the interest of readers and are easily shared on social networks [17]. Indeed, the work of Larrondo and Ferreras [20] invites us to consider these uses as a renewal and enrichment of journalism, although, as Tong and Zuo [21] point out, this practice is not exempt from subjectivity either. However, Stalph [22], in his work on the classification of data journalism, observes that although maps are the most interactive tool for the visualization of data, the most used are the traditional graphic representations and although a good number of stories are illustrated with maps, these are often static.

In the broader field of social communication, multimedia communication and interactive platforms can provide instruments that allow users to participate in the creation of databases that support the map or contribute other information or documentary sources of all kinds for the construction of knowledge. These users can act at times as traditional receivers and at other times as active users, the so-called prosumers or emirecs. Aparici and García Marín study this important difference, since:

“The prosumer is an individual who works (for free) for the market and reproduces the existing model, while the emirec is an empowered subject who has the potential capacity to introduce critical discourses that question the functioning of the system” [23].

Thus, social organizations use digital technologies, called civic technologies, to strengthen democracy by promoting knowledge and participation [24], showing that maps in digital communication are not only informative instruments but also critical, interactive, and participatory. Roth starts from concepts, such as “spatial narratives” or “story maps”, to consider the role of map generators as critical producers of visual narratives:

“Visual storytelling combines the primarily quantitative and analytical approaches developed from journalism, information visualization, and visual analytics with the primarily qualitative and reflexive approaches developed from critical cartography, Indigenous mapping, and participatory GIS. Visual storytelling gives cartography multiple ways to unite technology with praxis, product with process, and design with critique” [25].

Overall, the social Web can be a communication space for the development of collective intelligence [26], leading to the appearance of terms, such as open government, e-government, or e-democracy [27,28], along with others, such as geoinformation, geoknowledge, geosocial networks, or collective geoknowledge [29]. All these highlight the importance of situated knowledge [30] and maps as communication tools in the digital online environment, with the birth of cybergeography [31].

2.2. The Digital Humanities and the New Paradigms of Knowledge Production from the History of Communication

Changes in communication technologies and systems have also changed scientific activity [32], not only because of the use of new technologies but also fundamentally because there has been a change in the production of knowledge and culture [33] from a philosophy that we can refer to as computational [34].

Consequently, the digital humanities have been taking shape within academia [35], proposing the use of new tools and methodologies [36] and having evolved greatly with the expansion of the Internet, Web 2.0 and the implementation of work devices in the scientific field that allow the development of projects that enable new ways of organizing knowledge [32,37,38,39] and interaction [40].

Through critical discourse, perspectives have been incorporated that have given rise to subjects, such as the postcolonial digital humanities, global digital humanities, or social science and digital humanities of the south that for Nuria Rodríguez Ortega [41] entail a new concept of humanity and humanism. A number of these projects use maps as fundamental concepts and tools [42], shaping their collaborative use or “neogeography”.

In this sense, the now classic texts by Brian Harley [6] on maps as a social and power relations product together with other texts examining new uses of maps for political and social intervention [43] or participatory and open-source maps for issues of social interest, such as disaster prevention [44] or urban planning [45], are essential. However, we should not forget that some studies show that the use of technologies for intercultural collaboration requires certain user skills, since the designs of the instruments hide invisible biases for people of different cultures [46]. Similar problems have been warned about by authors who study the Public Participation Geographic Information System (PPGIS or PGIS). Radil and Anderson [47], in their review of PPGIS studies, point out the problems generated in participatory processes by the differences in knowledge of the participants [48], and different political cultures, which seldom accept new forms of co-decision [49,50,51,52]. Zhang [53] starts from the idea of geo-participation and alludes to digital divides [54] along with other factors that affect participation, such as socio-demographic characteristics [55,56] or the local scale of the process, with which users feel more confident compared to other territorial levels [57,58,59].

This paradigm shift is taking place slowly, weighed down by traditional uses that lead to using new resources only to transpose products that were made following analogue criteria to the Internet. A more profound change must consider a new plural humanism based on the understanding of the transformations of current social relations and the importance of communication in today’s society, for which communication systems must be understood as media for the symbolic reproduction of reality [60,61,62]. This perspective leads us to consider the Internet as an instrument to create a social explanation using maps for the representation of networks and communication media. An example of open knowledge that uses maps is Social Explorer (https://www.socialexplorer.com, accessed on 1 July 2021) (in Spain, Explorador Social (https://exploradorsocial.es, accessed on 1 July 2021), where one purpose is to provide a friendly environment to bring data closer to users, thus promoting access to information [63]. Other initiatives invite users invite to edit collaborative cartographies that anyone can use and share for their own purposes, such as OpenStreetMap (https://www.openstreetmap.org, accessed on 1 July 2021) or Geonames (http://www.geonames.org, accessed on 1 July 2021). In this way, they support new projects for the creation of decentralized knowledge.

These notions have been examined from the perspective of the history of communication by Moreno, Molina, and Simelio [64], who experiment with tools that use space, time, and information coordinates to associate personal experiences with explanations about the collective past and the present, using mapping tools associated with other tools so that everyone can access the information by browsing according to their interests through a multimedia user experience. This perspective develops the concepts plural humanism and plural citizenship to show that current societies are made up of people with different characteristics in terms of gender, age, geographic and cultural origin, economic capacity, social stratum, etc. who coexist in fundamentally urban environments and constituting complex webs of social relations. Thus, this plural citizenship requires a new humanism, also qualified as plural, to emphasize that it must be built through the recognition of diversity and dialogue. Therefore, the digital humanities need to provide instruments that are not simply a replica of the analogical procedures. On the contrary, they must consider the possibilities of the Internet and Web2.0 tools to design and build procedures and tools that allow dialogue under conditions of equality for and/or through knowledge of the personal and the collective, as well as through mutual recognition, promoting democratic participation and thus designing policies and solutions in accordance with this plurality of interests. The Internet society requires new forms of communication and information management, and all the more so as the media and communication systems (together with the means of transport) are at the heart of today’s global society [65].

3. Objectives and Methods

With regards to the plural humanism approach, web platforms have been built to develop innovative products in the field of journalism and communication aimed at facilitating the participation of plural citizens in the democratic functioning of society. As a result of these works, the Mapa Infoparticipa (www.mapainfoparticipa.com, accessed on 1 July 2021) and the Ciutadania Plural platform (www.ciutadaniaplural.com, accessed on 1 July 2021) have been developed.

The Mapa Infoparticipa platform is being used by researchers from universities in different autonomous communities of Spain to promote improvements in communication by local public administrations, especially in the transparency and quality of information of public administrations. This project is being internationalized.

The Ciutadania Plural platform is an instrument to learn how current societies have been built historically, making visible both collective information and personal experiences, and was developed with the aim of promoting participation and having a socio-political impact. It is thus a tool for the construction of online knowledge for the renewal of the social sciences and the humanities that uses digital maps to make complex explanations understandable from the perspective of the plurality of people’s social positions and accounting for social pluralities.

In this study, we provide, firstly, the theoretical-conceptual framework that we have built from a previously presented theoretical framework and the experimentation in the conceptualization, design, and development of the interactive maps integrated into the Mapa Infoparticipa Map and the Ciutadania Plural web platforms. Secondly, we show the characteristics of these tools and detail the application of the theoretical-conceptual framework, thereby offering both tools for the analysis of cases and discussion models.

4. Theoretical Model for the Conceptualization and Design of Interactive Digital Maps for the Production of Knowledge and Participation

After an explanation of the theoretical arguments, from the perspective of communication and information sciences, the digital humanities, and the history of communication, we systematize the elements that these fields of study contribute with regard to the uses of maps for knowledge production, political-social impact, and participation. The aim is to define the framework from which to establish practices regarding: (I) knowledge production, (II) political and social participation, and (III) user experience (Table 1).

Table 1.

Structure of the theoretical-conceptual framework.

4.1. Interactive Maps and Knowledge Production

Interactive maps are a central tool for building and publishing social knowledge to which each citizen can contribute their knowledge, experiences, and proposals from their social position and expectations in order to collaboratively build online a global vision. For this reason, it is necessary to consider starting from the principles of decentralization, pluralization, reticularization, and humanization.

- Knowledge decentralization. Decentralizing knowledge means showing the social reality, moving away from the traditional order in which the places where the centers of power are located determine the explanation of what happens within the whole territory to the plurality of men and women that make up the social body. This avoids androcentric, ethnocentric, Eurocentric, urbancentric orders, etc. At each node of the global society (understood as a place—city, village, or neighborhood—in which communication and transport networks converge), social processes occur differently. At each one, people in different situations coexist for reasons of gender, origin, social position, age, etc., whose experiences differ from others. This must lead to a rethinking of the traditional hierarchical ordering of knowledge, which is possible through maps complemented with other interactive and participatory resources. The reading of an interactive map does not have an established order, since each person can choose the starting point according to their interests, as well as the order in which they consult other elements.

- Pluralization of social knowledge. In a plural networked society, users have equally plural and situated knowledge. Only by considering the plurality of social experiences is it possible to understand the complexity of today’s societies. Thus, it is necessary to see that in addition to the decentralization of knowledge, it is necessary to give voice to the different social experiences, which are complex and in continuous interaction, and that are found in the physical spaces that make up the fabric of the networked society. In 2008, the historian Mercedes Vilanova formulated the Galileo conjecture in these terms: “History will be explained as a network of relationships, and the fragmented narratives that began in prehistory will defeat the state and universal histories that were possible as a result of writing” [66]. In the same article, the author states that the digital revolution will make this process inevitable and uncontrollable, and under a state of constant renewal, making the official memories, that is, the social discourses dominant until now, cease to be the absolute referents. Maps contribute to this change by allowing different voices to be presented in a geolocated complementary way such that a dialogue is established that makes similarities and differences visible in order to establish dialogic and deliberative processes in order to base social participation through knowledge and respect.

- The reticularization of knowledge. Reticularization breaks with the traditional schema of historical and social explanations based on the idea of nation, region, or locality as socio-political units built independently. Instead, it shows how the past and the present are the result of the interactions that occur between people and groups who exchange products and knowledge using the transport and communication systems present in each location and in each era. As a consequence of the decentralization and pluralization of knowledge, it is also possible to geolocate expert and non-expert knowledge, experiential or personal, offering situated explanations that gather together the whole of the social experience in dialogue and showing how networks structure social activity.

- Humanization of information and knowledge. Human quality information is that which is produced considering that citizens, as members of society, need useful information for every aspect of their life, and to be able to contribute their knowledge, experiences, and expectations. Moreno et al. [67] established five criteria to build information with human quality to promote participation, which we share as essential elements for the paradigm shift we propose. These criteria are: (I) the humanization of information, presenting citizens as protagonists of information and social events and avoiding depersonalization; (II) complete and transparent information; (III) contextualized information with memory; (IV) verified and verifiable information; and (V) understandable information.

4.2. Maps as Instruments to Promote Political and Social Participation

Interactive digital maps are useful tools to promote political and social participation. To achieve this objective, they must be considered taking into account the following criteria:

- Egalitarianism. Everyone must be able to participate by contributing knowledge, social experience, and expectations and, therefore, considering that each is the carrier of relevant knowledge and experiences for others. This entails upsetting the traditional knowledge hierarchies that rank people according to their knowledge in certain fields, excluding groups due to gender, origin, academic training, etc.

- Horizontality. Interactive maps allow contributions to be published by geolocating and structuring them, using chronological and thematic parameters that order them based on variable selection criteria, that is, chosen by each user and avoiding univocal hierarchies. The thematic criteria should be organized in such a way that they avoid the traditional logics that prioritize public events led by people, generally men, who occupy the centers of power and the places and spaces where they carry out these activities [62]. This thematization must show the relationship between personal stories and collective history, considering the pluralities present in contemporary societies to ensure that personal contributions are coordinated with each other and with expert contributions in order to avoid being anecdotal. This requires an effort to reorganize thought and traditional academic categories.

- Criticism. Interactive digital maps form part of the so-called civic technologies, which are used by social organizations as digital strategies to promote political participation in public institutions in order to strengthen democracy [24]. These tools allow a wide range of policies along with the management of public resources to be controlled and monitored, highlighting transparency as one of the key issues [68]. Producing a critical map involves conceiving it through collaborative parameters to create representations appropriate to the interests of the participants.

4.3. Maps as Instruments for the Visualization of Data That Favors the User Experience

Finally, we should point out the characteristics that interactive maps should have to favor the user’s experience. The end use of these systems by citizens depends on whether they respond to their interests and cultural habits, in general, and communicative habits in particular. Therefore, they must be produced in a context in which users are active subjects of an interactive multimedia experience.

- Interactivity. Online digital maps can be static when they are simple cartographic images, or interactive when they allow users to use selection, configuration, presentation, or other options to offer layers of information or improve the user experience with other accessories. The natural space for interactive maps is the Internet and online publications, which allow these options to be used in real time and with updated information.

- Multimediality. Interactive digital maps are multimedia products in their own right. However, they can also be complemented with other multimedia resources that can be accessed through the map to offer information in textual or audiovisual format.

- Reticularity of reading. As previously discussed, mapped spatial information offers a non-linear, reticular reading. This point, already discussed, is included here because it is also an element related to the experience of the user, who can choose the reading paths according to personal criteria.

- Participation. The interactive digital multimedia maps that we propose must offer the chance to participate in the construction of information in a collaborative and participatory way, both among experts and through receiving the contributions of any citizen. The development of the possibilities of Web2.0 enables the inclusion of different types of tools to incorporate these contributions, publishing these contents not as isolated units but as elements that complement each other and provide feedback.

5. Cases: The Mapa Infoparticipa and the Ciutadania Plural Platform

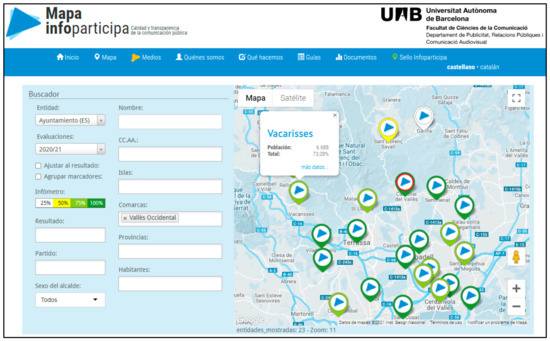

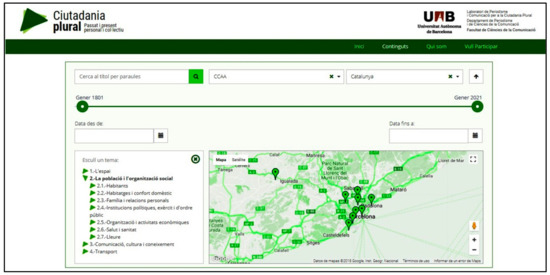

From the principles set out in the previous section, we developed two web platforms that share the use of an interactive digital map as a central communication tool: the Mapa Infoparticipa (Figure 1) and the Ciutadania Plural (Figure 2) platform. In both cases, the map was created with Google Maps and configured as a mashup. The objective of these projects was to put the developed theory into practice, to verify its usefulness and its limitations. Moreover, each platform has specific objectives in relation to its general purpose, such that the theoretical basis is tested with different functionalities.

Figure 1.

Screenshot of the Mapa Infoparticipa (13 May 2021), selection of the Town Councils of Spain, evaluation 2020/2021, Vallès Occidental region. Window with information on the Town Council of Vacarisses.

Figure 2.

Screenshot of the Ciutadania Plural website (13 May 2021). Selection of the autonomous community of Catalonia (Spain), theme 2: Population and social organization.

5.1. The Mapa Infoparticipa

The Mapa Infoparticipa (www.mapainfoparticipa.com, accessed on 1 July 2021)) is an interactive platform for political intervention. The research group publishes on this map the results of an academic investigation that uses a methodology described as a civic audit of the transparency of the websites of local public administrations and other public and private entities. Publication is open and free of charge so that citizens can monitor and evaluate the transparency of these entities, as well as promote improvements in institutional and organizational communication practices.

The use of a research transfer methodology conceived from the perspective of communication has led to the publication of the results of the evaluations on an interactive map. Thanks to this strategy, combined with incentives, such as the awarding of prizes for the administrations that best comply, the transparency of these administrations has improved [69].

This map allows citizens to access information using personal search criteria. In addition, the results are presented intelligibly for members of the government or opposition of a locality, heads of communication or other areas, as well as for members of social entities, citizens in general, and for journalists from the media.

The platform uses a content manager that allows the research team to work cooperatively online. In addition to the evaluation results, context information is collected for each evaluated unit: number of inhabitants of the municipality; population band according to defined categories; if possible, the political capital in a determined territory; political party of the mayor; and gender of the mayor.

Each evaluated municipality is marked with a different color depending on the results of the evaluation, such that the interpretation is visual and very simple: grey represents the municipalities that do not have a website; white, municipalities that do not reach 25%; yellow, a result between 25 and 50%; and green, when it exceeds 50%, increasing in intensity according to the score. In addition, a red trim distinguishes those municipalities that have been awarded the Infoparticipa seal.

Users can make searches according to municipality or other territorial demarcations. It is also possible to make selections according to contextual categories: the number of inhabitants, or the gender and political party of the mayor. Once the selection is made, an icon appears on the map, geolocated and in a color corresponding to the result of the evaluation; by clicking it, a bubble appears with the name of the town hall, the result of the evaluation, and the option “See details”. If the latter is displayed, a new window appears with the name of the city, the annual evaluations available, the context data, and the results of the indicator-by-indicator evaluation.

Furthermore, information is published on the different pages of the website to monitor the project and the results, detailing the methodology applied, the indicators used for the analysis, and the criteria for applying these indicators.

The procedure was first applied in Spain to evaluate the transparency of the websites of local administrations and was subsequently adapted to analyze the provincial councils and county councils of Catalonia. It has also been applied in Ecuador in three cases: local administrations [70], television broadcasters [71], and mining [72]. Each case required the study of the characteristics of the entities and the corresponding legislation to adapt the methodology.

Table 2 shows the characteristics of the project in relation to the theoretical framework developed.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the Mapa Infoparticipa.

Overall, the greatest strength of this project is that it was designed with the aim of influencing politics, providing open information on the communication practices of institutions or organizations to facilitate the knowledge of citizens. It was collaboratively built by experts from the perspective of the digital humanities. This allows for the coordination and publication of knowledge, breaking with traditional, analogical, hierarchical strategies. The main shortcoming is that the possibilities of participation of other groups or non-experts are low.

5.2. The Ciutadania Plural Platform

Ciutadania Plural (http://www.ciutadaniaplural.com, accessed on 1 July 2021) is a web platform for the construction of collective knowledge about the past and present of society, that is, to offer an explanation of the historical construction of societies. Cities, states, and other territories are not presented as isolated units but as nodes in which people interact and from which they interact with other people in other places through the use of communication media and transportation. This facilitates the understanding of social dynamics as a result of the interrelationships between people and groups and not simply as a result of the actions decided and carried out from centers of power. This offers a perspective on the construction of the networked society, forged over time thanks to these links between people and territories.

The database is structured based on space, time, and subject coordinates. Users can use a timeline to select the period of interest, the map to select the territory, and the thematic list to select the subject they wish to obtain information about. So that this thematic field does not reproduce the traditional hierarchies of historical knowledge, it has been organized into four categories: the territory or social space in which people’s lives take place; the population, incorporating the women and men who live together, considering the pluralities in terms of age, social condition, origin, or other social characteristics; the media, culture, and knowledge transmission systems; and finally, the means of transport. We thus show that the mobilities and imaginaries of men and women of all ages and social conditions are articulated through means of transport and the media, both the traditional ones that distribute flows of institutionally constructed information, as well as other information related to the experiences and knowledge of people through social networks and other possibilities offered by communication-information technologies and the Internet.

The three selections (time-space and theme) lead to a content field created by experts, constructed as journalistic documents, incorporating text, audiovisual, and other resources. Moreover, users can make textual and audiovisual contributions by associating them with expert content through time, location, and theme tags. The contents therefore complement and relate to each other, offering a plural complex perspective, relating explanations about collective experiences with other personal ones, about the past and present, and about the local and the supra-local. This design connects with the perspective of plural humanism, which uses personal memories to build a digital memory: “A democratic, globalized, multicultural, multilingual memory” [73].

The platform is backed up by more than 400 documents and 7 stories or sets of documents with common parameters, mainly about the past and present of Catalonia (Spain) and Popayán (Colombia) thanks to a collaboration with the Colegio Mayor University Institution of Cauca. It is, therefore, a model to construct an explanation about the past and present of networked societies.

Table 3 shows the characteristics of the project in relation to the framework developed.

Table 3.

Characteristics of the Ciutadania Plural project.

The aim of the platform leads to a different conceptualization to that of the Mapa Infoparticipa. The greatest strengths of this project are therefore the possibilities for participation and interrelation between personal and expert contributions for the construction of plural explanations.

6. Conclusions and Discussion

Today’s complex plural society requires new forms of knowledge production and publication. Here, we described the importance of maps as instruments that can lead to a transformation of the systems of production and publication of knowledge in the current social communicative context. We highlighted the importance of creating procedures that allow the criteria with which interactive maps are constructed to be subverted so that they do not reproduce traditional hierarchical systems and thus show how social knowledge is the result of the physical and symbolic interactions of the set of people who constitute the social body. The digital humanities can be a fruitful field to obtain these results. However, we have shown that for this, a concept going beyond the mere reproduction of analogical procedures in the virtual setting is necessary. This perspective, which we refer to as plural humanism and which we approach from the perspective of the history of communication as a discipline that allows us to understand culture as forms of communication organization, shows how expert knowledge can be articulated with the personal knowledge of each human being.

We have put this concept into practice with the development of the Mapa Infoparticipa and the Ciutadania Plural web platform. These two cases share this work perspective but also have substantial differences, since they address different problems. At the same time, they allow us to observe how the common theoretical-conceptual framework that we have established serves as the foundation for each case, provided that the particular needs of each specific project are taken into account and, therefore, appropriate priorities are established. Thus, in the case of the Mapa Infoparticipa, the priority is to provide information that can be used by anyone to monitor the transparency of public administrations. However, in the case of the Ciutadania Plural project, the main aim is to build a knowledge construction platform that relates personal stories with collective history so that each person can recognize themselves in a general explanation, contributing their particular experience. The participation tools are therefore more important, and the map must be linked with other chronological and thematic instruments suitable for the purpose.

Regarding the use that citizens have made of the platforms, in the case of Ciutadania Plural, the citizen contributions collected so far are testimonial, since after the development and launch, a dissemination campaign has not yet been carried out. On the contrary, the Mapa Infoparticipa platform is intensely active. It receives thousands of visits, and the work team continuously receives requests for information and proposals from citizens, neighborhood, or professional organizations, and especially from municipal technicians who use it to improve their transparency. Although some usage data can be consulted on the same website, the detailed information on its use by the different groups has yet to be studied.

Although the theoretical model has been validated with practical developments that confirm that interactive maps can be used as tools for participation and political intervention and as instruments for the collaborative construction of knowledge, in the future, we intend to follow other cases of the use of maps for other purposes, both those in media contexts and others resulting from the activity of organizations that produce civic technologies or social maps. The analysis of these products will allow us to establish the success and limitations of the concept proposed here.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Pedro Molina Rodríguez-Navas; methodology, Pedro Molina Rodríguez-Navas; validation, Pedro Molina Rodríguez-Navas; formal analysis, Pedro Molina Rodríguez-Navas; investigation, Pedro Molina Rodríguez-Navas, Johamna Muñoz Lalinde and Narcisa Medranda Morales; resources, Pedro Molina Rodríguez-Navas; writing—original draft preparation, Pedro Molina Rodríguez-Navas, Johamna Muñoz Lalinde and Narcisa Medranda Morales; writing—review and editing, Pedro Molina Rodríguez-Navas; supervision, Pedro Molina Rodríguez-Navas. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Perceval, J.M. Historia Mundial de la Comunicación; Cátedra: Madrid, Spain, 2015; p. 124. [Google Scholar]

- Buisseret, D. La Revolución Cartográfica en Europa. La Representación de Nuevos Mundos en la Europa del Renacimiento; Paidos: Barcelona, Spain, 2004; pp. 1400–1800. [Google Scholar]

- Monmonier, M.S. Drawing the Line: Tales of Maps and Cartocontroversy; Henry Holt: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Koyre, A. Del Mundo Cerrado al Universo Infinito; Siglo XXI: Madrid, Spain, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Todorov, T. Nous et les Autres; Seuil: Paris, France, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Harley, J.B. Hacia una deconstrucción del Mapa. In La Nueva Naturaleza de los Mapas; Fondo de Cultura Económica: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2005; pp. 185–207. Available online: http://148.202.18.157/sitios/catedrasnacionales/material/2010a/luis_cabrales/2.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Mezzadra, S.; Neilson, B. La Frontera Como Método; Traficantes de sueños: Madrid, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tamayo, J.J. Neofascismo y Religión. Los Predficadores del Odio. In Neofascismo. La Liberal; Siglo XXI: Madrid, Spain, 2019; pp. 189–204. [Google Scholar]

- López Borrego, R. Estética del Viaje. Reflexiones en Torno al arte y el Nomadismo Global; Amarante: Salamanca, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Castro Flórez, F. Mierda y Catástrofe. Síndromes Culturales del Arte Contemporáneo; Fórcola: Madrid, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- LabComPublica. Laboratorio de Periodismo y Comunicación para la Ciudadanía Plural (n.d.). Mapa Infoparticipa. Available online: https://www.mapainfoparticipa.com/index/mapa (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- LabComPublica. Laboratorio de Periodismo y Comunicación para la Ciudadanía Plural (n.d.). Ciutadanía Plural. Available online: http://www.ciutadaniaplural.com/#/home (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Link, E.; Henke, J.; Möhring, W. Credibility and Enjoyment through Data? Effects of Statistical Information and Data Visualizations on Message Credibility and Reading Experience. J. Stud. 2021, 22, 575–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyna, J.; Hanham, J.; Meier, P. The Internet explosion, digital media principles and implications to communicate effectively in the digital space. E-Learn. Digit. Media 2018, 15, 36–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero, J.L. La Infografía. Técnicas, Análisis y Usos Periodísticos; Universitat de València: Valencia, Spain, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Sarın, P.; Uluğtekin, N. Analyzing Newspaper Maps for Earthquake News through Cartographic Approach. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2019, 8, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- López Linares, C. ¿Cómo pueden los mapas ayudar a los periodistas a narrar mejor sus historias? Fundación Gabo. 2021. Available online: https://fundaciongabo.org/es/blog/laboratorios-periodismo-innovador/como-pueden-los-mapas-ayudar-los-periodistas-narrar-mejor-sus (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Canter, L. It’s not all cat videos. Digit. J. 2018, 6, 1101–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, M.; Rodríguez, M.P.; Díaz de Guereñu, J.M. Journalism in the age of hybridization: Los vagabundos de la chatarra—comics journalism, data, maps and advocacy. Catalan J. Commun. Cult. Stud. 2018, 10, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrondo Ureta, A.; Ferreras Rodríguez, E.M. The potential of investigative data journalism to reshape professional culture and values. Study Bellwether Transnatl. Projects. Commun. Soc. 2021, 34, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, J.; Zuo, L. The Inapplicability of Objectivity: Understanding the Work of Data Journalism. Journal. Pract. 2021, 15, 153–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stalph, F. Classifying Data Journalism. Journal. Pract. 2018, 12, 1332–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparici, R.; García-Marín, D. Prosumers and emirecs: Analysis of two confronted theories. Comunicar 2018, 55, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sánchez Duarte, J.M.; Bolaños Huertas, M.V.; Magallón Rosa, R.; Caffarena, V.A. El papel de las tecnologías cívicas en la redefinición de la esfera pública. Hist. Y Comun. Soc. 2015, 20, 483–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roth, R.E. Cartographic Design as Visual Storytelling: Synthesi and Review of Map-Based Narratives, Genres, and Tropes. Cartogr. J. 2021, 58, 83–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobo, C. Intercreatividad y Web 2.0. La construcción de un cerebro digital planetario. In Planeta Web 2.0. Inteligencia Colectiva o Medios Fast Food. Barcelona/México DF: Grup de Recerca d’Interaccions Digitals; Cobo, C., Hugo, P., Eds.; Universitat de Vic: Barcelona, Spain; pp. 43–60.

- Moon, M.J. The Evolution of E-Government among Municipalities: Rhetoric or Reality? Public Adm. Rev. 2002, 62, 424–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, E.W.; Hinnant, C.C.; Moon, M.J. Linking Citizen Satisfaction with E-Government and Trust in Government. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2005, 15, 371–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rodríguez Mellado, J.A.; Torres Manjón, J. Redes geosociales: Una Web cercana, cartográfica y de sensaciones, realizada por todos y basada en el geoconocimiento colectivo. In Tecnologías de la Información geográfica: La Información Geográfica al Servicio de los Ciudadanos; Ojeda, J., Pita, M.F., Vallejo, I., Eds.; Secretariado de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Sevilla: Sevilla, Spain, 2010; pp. 1369–1378. [Google Scholar]

- Haraway, D. Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Buzai, G.D. Geografía y tecnologías digitales del siglo XXI: Una aproximación a las nuevas visiones del mundo y sus impactos científicos-tecnológicos. Scr. Nova 2004, 8, 170. Available online: http://www.ub.edu/geocrit/sn/sn-170-58.htm (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Capel, H. Geografía en red a comienzos del Tercer Milenio. Por una ciencia solidaria y en colaboración. Scr. Nova. Rev. Electrónica De Geogr. Y Cienc. Soc. 2010, XIV, 313. Available online: http.://www.ub.es/geocrit/sn/sn-313.htm (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Bates, D. The political theology of entropy: A Katechon for the cybernetic age. Hist. Hum. Sci. 2020, 33, 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afanador, M.J. Tecnología al servicio de las humanidades. Telos 2019, 112, 66–71. Available online: https://telos.fundaciontelefonica.com/telos-112-cuaderno-central-humanidades-en-un-mundo-stem-maria-jose-afanadortecnologia-al-servicio-de-las-humanidades (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Vinck, D. Humanidades Digitales: La Cultura Frente a Las Nuevas Tecnologías; Gedisa: Barcelona, Spain, 2018; Available online: https://elibro.net/es/ereader/uab/118568?page=86 (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Oropesa Serrano, M.C.; Rodríguez Roche, S. Digital Humanities: Analysis of Research carried out in the Faculty of Communication in the Period 1993–2016. Cienc. De La Inf. 2017, 48, 9–14. Available online: http://content.ebscohost.com/ContentServer.asp?EbscoContent=dGJyMNXb4kSep7U4y9fwOLCmsEmep7RSsKi4S7OWxWXS&ContentCustomer=dGJyMPPX4FPr1%2BeGudvii9%2Fm5wAA&T=P&P=AN&S=R&D=asn&K=128141659 (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Thomas, W.G. Computing and the Historical Imagination. In A Companion to Digital Humanities; Schreibman, S., Siemens, R., Unsworth, J., Eds.; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2004; pp. 56–68. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenzweig, R. Scarcity or Abundance? Preserving the Past in a Digital Era. Am. Hist. Rev. 2003, 108, 735–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnton, R. The New Age of the Book. New York Rev. Books 1999, 46, 5–7. Available online: https://www.nybooks.com/articles/1999/03/18/the-new-age-of-the-book/ (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Del Río, G. La mirada humana, la mirada crítica. Telos 2019, 112, 50–55. Available online: https://telos.fundaciontelefonica.com/telos-112-cuaderno-central-humanidades-en-un-mundo-stem-gimena-del-rio-la-mirada-humana-la-mirada-critica/ (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Rodríguez Ortega, N. Humanidades digitales, poshumanidad y neohumnismo. Telos 2019, 112, 58–65. Available online: https://telos.fundaciontelefonica.com/telos-112-cuaderno-central-humanidades-en-un-mundo-stem-nuria-rodriguez-humanidades-digitales-poshumanidad-y-neohumanismo/ (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Ethington., P.J. Los Angeles and the Problem of Urban Historical Knowledge. Am. Hist. Rev. 2000, 105, 1667. Available online: https://chnm.gmu.edu/digitalhistory/links/cached/introduction/link0.23.LAurbanhistoricalknowledge.html (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Habegger, S.; Mancila, I. El Poder de la Cartografía Social en las Prácticas Contrahegemónicas o la Cartografía Social Como estrategia Para Diagnosticar Nuestro Territorio. Available online: http://www.beu.extension.unicen.edu.ar/xmlui/bitstream/handle/123456789/365/Habegger%20y%20Mancila_El%20poder%20de%20la%20cartografia%20social.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Klonner, C.; Hartmann, M.; Dischl, R.; Djami, L.; Anderson, L.; Raifer, M.; Lima-Silva, F.; Castro Degrossi, L.; Zipf, A.; Porto de Albuquerque, J. The Sketch Map Tool Facilitates the Assessment of OpenStreetMap Data for Participatory Mapping. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, J. Evaluation Methods for Citizen Design Science Studies: How Do Planners and Citizens Obtain Relevant Information from Map-Based E-Participation Tools? ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampermann, A.; Opdenakker, R.; Heijden, B.; Bücker, J. Intercultural Competencies for Fostering Technology-Mediated Collaboration in Developing Countries. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radil, S.M.; Anderson, M.B. Rethinking PGIS: Participatory or (post)political GIS? Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2019, 43, 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, B. Constructing community through maps? Power and praxis in community mapping. Prof. Geogr. 2006, 58, 470–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghose, R. Public-participation GIS. In The International Encyclopedia of Geography; Richardson, D., Ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Radil, S.; Jiao, J. Public participatory GIS and the geography of inclusion. Prof. Geogr. 2016, 68, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, K.; Baud, I.; Denis, E.; Scott, D.; Sydenstricker-Neto, J. Participatory spatial knowledge management tools: Empowerment and upscaling or exclusion? Inf. Commun. Soc. 2013, 16, 258–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G. Public participation GIS (PPGIS) for regional and environmental planning: Reflections of a decade of empirical research. URISA J. 2012, 25, 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S. Public participation in the Geoweb era: Defining a typology for geo-participation in local governments. Cities 2019, 85, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieber, R.E.; Robinson, P.J.; Johnson, P.A.; Corbett, J.M. Doing public participation on the geospatial web. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2016, 106, 1030–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, B.Y.; Brudney, J.L.; Jakobsen, M.; Andersen, S.C. Coproduction of government services and the new information technology: Investigating the distributional biases. Public Ad-Minist. Rev. 2013, 73, 704–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, A.; Dunham, J.M. Volunteered geographic information, urban forests, & envi-ronmental justice. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2014, 53, 65–75. [Google Scholar]

- Brabham, D.C. Crowdsourcing the public participation process for planning projects. Plan. Theory 2009, 8, 242–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.; Kyttä, M. Key issues and research priorities for public participation GIS (PPGIS): A synthesis based on empirical research. Appl. Geogr. 2014, 46, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellman, B. Little boxes, glocalization, and networked individualism. In Digital Cities II: Computational and Sociological Approaches; Tanabe, M., van den Besselaar, P., Ishida, T., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001; Volume 2362, pp. 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno Sardà, A. El Arquetipo Viril Protagonista de la Historia. Ejercicios de Lectura No-androcéntrica; LaSal: Barcelona, Spain, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno Sardà, A. La Otra ‘Política’ de Aristóteles. Cultura de Masas y Divulgación del Arquetipo Viril; Icaria: Barcelona, Spain, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno Sardà, A. De qué Hablamos cuando Hablamos del Hombre. Treinta Años de Crítica y Alternativas al Pensamiento Androcéntrico; Icaria: Barcelona, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Esteve, A.; Zueras, P. El equipo del Explorador Social. Explorador Social: El dato hecho realidad. Perspect. Demogr. 2021, 23, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardà, A.M.; De Barcelona, U.A.; Rodríguez-Navas, P.M.; Solà, N.S. CiudadaniaPlural.com: From Digital Humanities to Plural Humanism. Rev. Lat. De Comun. Soc. 2017, 72, 87–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berners, T.; Fischetti, M. Weaving the Web: The Original Design and Ultimate Destiny of the World Wide Web by Its Inventor; Texere: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Vilanova, M. Trabajos por hacer: Cuatro conjeturas. Hist. Antropol. Y Fuentes Orales 2008, 39, 73–80. [Google Scholar]

- Sardá, A.M.; Rodríguez-Navas, P.M.; Rius, M.C.; Pérez, A.A.; Farran, M.B. Infoparticip@: Periodismo para la participación ciudadana en el control democrático. Criterios, metodologías y herramientas. Estud. Sobre El Mensaje Periodis. 2013, 19, 783–803. Available online: http://revistas.ucm.es/index.php/ESMP/article/view/43471 (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Skaržauskienė, A.; Mačiulienė, M. Mapping International Civic Technologies Platforms. Informatics 2020, 7, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amparo, M.S.; Pedro, M.R.-N.; Núria, S.S. The impact of legislation on the transparency in information published by local administrations [El impacto de la legislación sobre transparencia en la información publicada por las administraciones locales]. El Prof. De La Inf. 2017, 26, 370–380. Available online: https://www.elprofesionaldelainformacion.com/contenidos/2017/may/03.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Rodríguez-Navas, P.M.; Morales, N.J.M. The Transparency of Ecuadorians municipal websites: Methodology and results [La transparencia de los municipios de Ecuador en sus sitios web: Metodología y resultados]. Am. Lat. Hoy 2018, 80, 143–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- López López, P.C.; Márquez Domínguez, C.; Molina Rodríguez-Navas, P.; Ramos Gil, Y.T. Transparency and public information in the Ecuadorian television: Ecuavisa and TC Televisión cases. Rev. Lat. De Comun. Soc. 2018, 73, 1307–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steudt, W.R.; Medranda Morales, N.; Sánchez Montoya, R. Evaluation of transparency of public information on Canadian mining projects in Ecuador. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2020, 7, 1587–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo Flórez, J.A. Historia digital: La memoria en el archivo infinito. Hist. Crit. 2011, 43, 82–103. Available online: https://revistas.uniandes.e (accessed on 1 July 2021). [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).