Abstract

Energy efficiency represents a fundamental aspect of sustainable industrial automation, where minimizing energy expenditure supports both environmental and economic goals. This work presents the modeling and comparative analysis of the energy consumption of three planar robotic manipulators performing pick-and-place operations: a serial RRR configuration (RRR-D2) and two alternative PRR architectures (PRR90 and PRR45) featuring linear prismatic guides. For each manipulator, kinematic and dynamic models are derived, and actuator electro-mechanical effects are incorporated to obtain realistic energy evaluations. The analysis is carried out over four representative trajectories and two design variables, enabling a consistent comparison in terms of both total and recoverable energy through regenerative braking. Results show that geometric and actuation parameters significantly influence energy performance and that specific PRR configurations can achieve comparable motion capabilities to the RRR structure with reduced energy demand. The proposed framework supports energy-aware robot selection and design, contributing to the development of efficient and sustainable planar manipulators for repetitive industrial operations.

1. Introduction

In recent years, environmental concerns together with the continuous rise in energy costs have pushed policy makers and industries to pursue more sustainable production systems [1]. The United Nations’ commitment to climate neutrality by 2030 and the related 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) underline the need to improve the energy efficiency of manufacturing systems. In particular, SDG-9 (“Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure”) [2] highlights the evaluation, reduction, and minimization of energy use in production processes as a central target of contemporary engineering design [3,4,5,6].

Within robotics and automation, energy-reduction methods are commonly grouped into three complementary families: (i) hardware-based interventions, (ii) software/trajectory-based strategies, and (iii) mixed approaches that combine mechanical and control design [7,8,9]. Hardware-oriented contributions include the use of lightweight structures, efficient transmissions, and compliant components that passively store and release energy, thus reducing actuation effort [10,11,12]. Software- or trajectory-based strategies, on the other hand, rely on motion optimization, time-scaling, and path retiming techniques that minimize electrical power and mechanical work during operation [13,14,15,16,17,18]. Mixed approaches integrate physical modeling, control tuning, and automatic code generation for cycle optimization in real robot cells [19,20,21,22,23]. Comprehensive reviews and systematic assessments emphasize accurate energy modeling, parameter identification, and the quantification of the impact of motion-profile shaping on energy performance in industrial robots [4,8,9,13,14,20,21]. These efforts collectively form the foundation of energy-aware robotic design, enabling sustainability-oriented decision making for both industrial and research applications [9,11,14].

The present contribution extends the approach proposed in [24] and addresses energy efficiency in repetitive planar pick-and-place tasks by comparing three two-degree-of-freedom (2-DoF) planar manipulators: an existing serial RRR architecture (denoted RRR-D2) and two PRR variants (PRR90 and PRR45) that employ two linear prismatic guides. The overarching objective is to assess the potential substitution of the RRR-D2 by PRR mechanisms while preserving workspace coverage and task feasibility, in line with energy-aware design principles and recent classifications of reduction strategies [11,13,25,26,27].

The analysis proceeds in two stages. First, the three architectures are compared from a workspace and geometric standpoint, with the principal parameters of the PRR variants determined so that their reachable area matches that of the RRR-D2. Second, complete kinematic and dynamic models are developed and used to evaluate the energy expenditure along four representative trajectories, while exploring two design variables (e.g., total movement time and a shift in the robot’s base origin). For each scenario, both the total consumed energy and the theoretically recoverable energy during deceleration phases are computed, in accordance with prior works on regenerative braking and energy reuse in cyclic robotic tasks [7,20,28,29,30].

The contribution of this study is twofold: (i) a structural comparison between RRR and PRR planar architectures tailored to pick-and-place operations, and (ii) a quantitative evaluation of their energy performance under multiple trajectories and design-variable scenarios. The findings demonstrate that suitably parameterized PRR mechanisms can achieve task-space performance comparable to the RRR-D2 while significantly reducing energy consumption, thus supporting their adoption in energy-sensitive industrial contexts [9,11,13,14,19,31].

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the studied planar manipulators and their kinematic architectures. Section 3 describes the modeling approach, including kinematics, dynamics, and the energy-recovery formulation. Section 4 presents the comparative energy expenditure analysis across four trajectories and two design variables. Section 5 discusses the results and implications for manipulator selection and design. Section 6 concludes the paper and outlines future research directions.

2. Studied Planar Robotic Manipulators

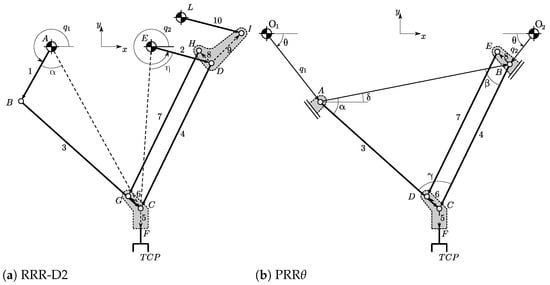

Three planar closed-chain manipulators with two degrees of freedom, each designed so that the end-effector preserves a fixed orientation, are considered. The first architecture is a RRR-Delta2 (RRR-D2) mechanism featuring two actuated revolute joints, while the other two correspond to PRR configurations, equipped with two actuated prismatic joints inclined by a varying angle with respect to to the horizontal axis. Their kinematic layouts and corresponding models are illustrated in Figure 1. In all three designs, the use of a parallelogram linkage ensures that the end-effector orientation remains constant throughout the motion. In Table 1, the links length (L) and mass (M) parameters are reported. In order for the PRR robotic manipulators to be compared with the RRR-D2, which represents an existing physical prototype, the same links are exploited for the kinematic structure of the PRR configurations (i.e., the RRR dyad is the same for all the considered robots) to isolate the influence of kinematic structure and inertial parameters while ensuring a comparable workspace. Based on the angle inclination of the two linear guides, a vertical PRR90 () configuration and an inclined PRR45 () are taken into consideration for this study. The resulting manipulator geometries follow from the defined angles and link lengths, chosen to maximize reach within motion constraints.

Figure 1.

Kinematic models of the investigated robotic manipulators. Capital letters represent kinematic pair centers, whereas numbers represent rigid links.

Table 1.

Parameters for the RRR and PRR kinematic structures.

3. Modeling Approach

The three manipulators are modeled as planar multibody systems, and the kinematic models are shown in Figure 1. The kinematic, dynamic, and electro-mechanical models are introduced in the following subsections.

3.1. Kinematic Model

With reference to Figure 1a, the inverse position analysis of the RRR-D2 parallel robot can be solved as follows. Given the tool pose and referring to each rigid link with a vector for each link with index i,

Thus, four configurations are possible, depending on the signs of and .

The inverse velocity analysis, considering that the point F has the same velocity of the and since , is given by

The matrix is derived from the differential kinematic relations established in the direct velocity analysis, and its inverse defines the mapping from the Cartesian velocity space to the joint velocity space. This formulation is particularly useful in trajectory planning and dynamic simulations, where the desired end-effector motion is given, and the corresponding actuator velocities must be determined to ensure kinematic consistency.

Regarding the PRR architecture, the independent coordinates of the system are defined as linear coordinates and . The reference positions are given by

where the linear distance between the guides can be written as a function of the angle

to maximize reach with defined geometries and avoid singular configurations.

Given the position of point and the two independent coordinates and , the kinematic relations of the mechanism can be expressed by

where the points A and B represent the locations of the two prismatic joint sliders, given by

with and denoting the unit vectors along the directions of the prismatic actuators

The prismatic joints are inclined by an angle with respect to the vertical axis. By substituting the above expressions, the geometric relations become

Solving these equations provides the actuator displacements and as functions of the end-effector position

These relationships define the inverse kinematics of the planar PRR manipulator, allowing the computation of the prismatic joint positions corresponding to a given Cartesian location of the end-effector. The ± sign accounts for the two possible assembly configurations (elbow-up and elbow-down) of the mechanism.

The linear velocity of point can be expressed in relation to the prismatic joint velocities by

where represents the Jacobian matrix (also known as the velocity mapping matrix) that relates the joint space to the Cartesian space of the end-effector. By inverting this relationship, the joint velocities are obtained by

As for the RRR-D2, the matrix is derived from the differential kinematic relations established in the direct velocity analysis, and its inverse defines the mapping from the Cartesian velocity space to the joint velocity space.

3.2. Dynamic Model

The equations of motion for multibody systems are formulated using the Lagrangian method, resulting in the following expression for the system dynamics [7,26,27]

Here, the vectors , , and represent the generalized coordinates for position, velocity and acceleration, respectively. For the present 2-DoF manipulators, the generalized position, velocity and acceleration coordinates are given by

being the rotational parameters (angles) for the RRR-D2 manipulator and linear parameters (distances) for the PRR45 and PRR90 manipulators.

Equation (20) incorporates several force terms including the inertia forces given by and the Coriolis and centrifugal effects given by . Following the Lagrangian approach, the inertia matrix is obtained as the sum of the contributions of each rigid body i,

where and are the mass and the mass moment of inertia about the center of mass of the body i respectively, maps the joint velocities to the linear velocity of the center of mass of the body i

and maps joint velocities to the angular velocity out of plane of the body i

In the implementation used in this work, the matrices and are symbolically computed from the kinematic model and evaluated along the trajectory. The sum in Equation (22) includes the tool, the rigid links, and the two motors. Based on defined by Equation (22), the Coriolis and centrifugal terms are obtained from the Christoffel symbols

These expressions are generated symbolically and implemented as explicit functions of and in the simulation code used for the energy analysis.

The viscous damping forces and the static friction forces are given by

where and are the viscous and static friction coefficients of joint j, respectively. The gravitational effects are collected in

with denoting the gravity term associated with joint j. The actuator generalized forces differ for the two architectures. For the RRR-D2 robot, the actuated generalized forces are the joint torques

while for the PRR manipulators, the actuated generalized forces are the linear joint forces

The relation between the motor torque and the actuation toques and forces applied to the manipulator is described by

These equations apply to the RRR-D2 manipulator and to the PRR90 and PRR45 configurations, respectively. The introduced dynamic relationships thus enable to determine the motor torques at each time step from a given trajectory of the tool center point.

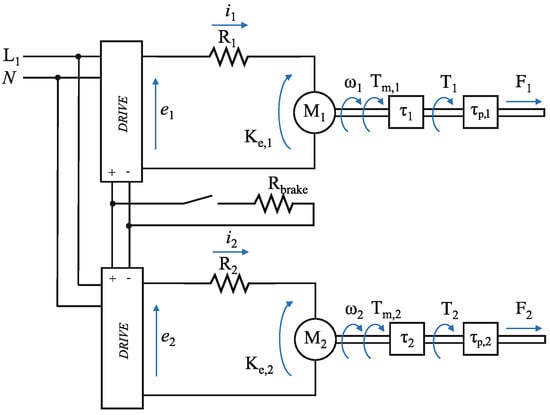

3.3. Electro-Mechanical Model

The actuation system is represented by a brushless DC motor. Its combined electrical and mechanical system is illustrated in Figure 2. As in [7], the motors electrical characteristics are described by the following equations:

In these expressions, denotes the input voltage, the electrical current, the resistance of the motor windings, the torque constant, the back-emf constant, and the motor angular velocity.

Figure 2.

Electro-mechanical model, according to [7].

The electrical energy consumed by the motors over time is calculated as

This energy metric is employed to evaluate and compare the energy consumption of the different manipulator configurations under study [25].

4. Comparative Energy Expenditure Analysis

The three robots are evaluated with respect to their reachable workspace and their energy consumption. The outcomes of the simulations are presented and discussed in the following sections.

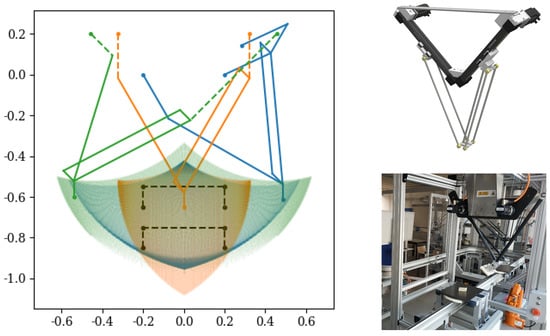

4.1. Workspace Analysis

The three manipulators share identical link dimensions and masses, as the same mechanical components are reused across all configurations. The RRR-D2 manipulator, whose dimensions are taken from [7], serves as the reference system. This robotic manipulator is available at the Smart Mini Factory (SMF) laboratory of the Free University of Bozen-Bolzano [32], and its structure has been adopted to ensure a fair comparison among the three architectures. In this context, the PRR manipulators (PRR45 and PRR90) are assembled using the same link lengths with the guides defined by the definition angle and the geometric limits mentioned above. Their resulting workspaces are then analyzed and compared with that of the reference manipulator. Figure 3 illustrates the reachable areas of all three robots, together with a picture of the RRR-D2 prototype available at the SMF laboratory and a commercial example of a PRR45. For the PRR45 configuration, the spacing between the linear guides is determined as described in Section 3 to maximize the reach with given geometric dimensions. For the PRR90 manipulator, since , the spacing between the linear guides is determined by the configuration when one actuator is fully retracted and the other is fully extended, resulting in the corresponding link connected to the fully extended actuator being aligned horizontally. In this configuration, the end effector is positioned slightly below the fully extended actuator, due to the geometry of the linkage. Both PRR configurations are mounted above the origin of the RRR-D2 to facilitate a clear geometric comparison of their reachable areas.

Figure 3.

Left: Workspace analysis and manipulators in random position: ■ RRR-D2, ■ PRR90, ■ PRR45; Right-up: commercial example of PRR45 adapted from [33]; Right-down: RRR-D2 robot at SMF lab.

As shown in Figure 3, the three manipulators present distinct workspace shapes due to their actuation layouts, despite sharing the same link dimensions. The RRR-D2 exhibits a compact, symmetric reachable area owing to its rotary joints located above the workspace. The PRR90 configuration, with vertically oriented prismatic actuators, achieves a similar vertical range but a slightly reduced horizontal span. Conversely, the PRR45 configuration, featuring actuators inclined at , provides a broader horizontal and vertical coverage that slightly exceeds that of the RRR-D2. Despite these geometric variations, all three manipulators cover comparable regions of the task space and are suitable for equivalent planar pick-and-place operations. Therefore, subsequent analyses focus on their energy performance, assuming comparable operational conditions rather than identical workspace boundaries.

4.2. Sizing of Actuators and Transmission Systems

For the RRR-D2 manipulator, the same actuators as those installed on the physical prototype are considered. Their main electro-mechanical specifications are listed in Table 2. Both joints employ identical motors and transmission assemblies.

Table 2.

Electro-mechanical parameters for RRR-D2 and PRR.

In the case of the PRR manipulators, each linear guide is actuated by an electric motor coupled to a belt–pulley transmission. The selected actuators correspond to those adopted in similar configurations reported in [34], ensuring a consistent reference for dynamic and energy analyses. The same motors are used for both PRR90 and PRR45 architectures, while the transmission ratios have been adjusted to satisfy the respective kinematic requirements.

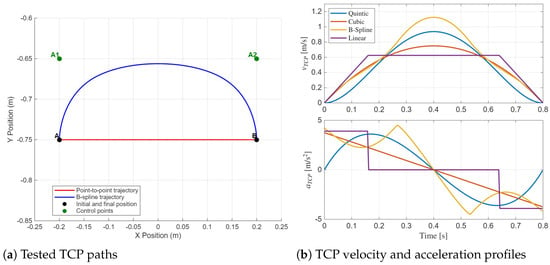

4.3. Dynamic Analysis and Energy Evaluation

This section outlines the methodology adopted to compare the three manipulators in terms of energy consumption during a representative pick-and-place task. The selected operation serves as a reference because of its relevance and ease of replication in both industrial and laboratory contexts. The simulated scenario mirrors the typical workflow of the physical prototype RRR-D2, which is commonly employed to retrieve objects and deposit them onto a nearby platform (see Figure 3). In this study, four different trajectories are tested as described below. Figure 4 displays the tested TCP paths, along with the velocity and acceleration profiles.

Figure 4.

Overview of the tested trajectories: (a) geometric TCP paths, and (b) corresponding TCP velocity and acceleration profiles on the four trajectories.

The tested paths span between the initial position A and the final position B. On these paths, the tested trajectories are as follows:

- Point-to-point motion using a trapezoidal velocity profile;

- Two point-to-point motions with continuous velocity profiles, where the position is interpolated using (i) a cubic polynomial and (ii) a quintic polynomial primitive;

- B-spline trajectory with continuous velocity profile, defined through two control points A1 and A2. The curve passes only through the initial and final points (A and B) while remaining enclosed within the polygon formed by control points.

To assess the energy consumption of the three manipulators along the trajectories described above, two design variables are introduced:

- Total duration of motion (T): The analyzed movement times vary between (representing a rapid motion) and (representing a slower motion).

- Vertical displacement of the robot base (): Several installation configurations were examined to determine whether adjusting the vertical position of the fixed joints relative to the working platform could reduce energy usage. Specifically, this parameter ranges from to for point-to-point trajectories, and from to for the B-spline trajectory.

The energy performance was numerically assessed by varying the selected parameters to identify the most efficient configuration for the assigned task. Both the consumed and recoverable energy were evaluated. In conventional systems, the negative motor power required for braking is dissipated as heat and remains unused; however, it can theoretically be recovered to reduce the overall energy demand. In this study, this quantity is referred to as recoverable energy. Each manipulator was tested by moving a payload of 2 during the forward motion and performing the return motion without load.

5. Results and Discussion

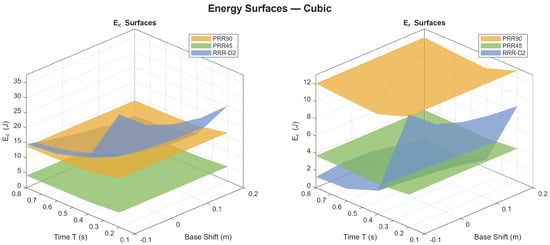

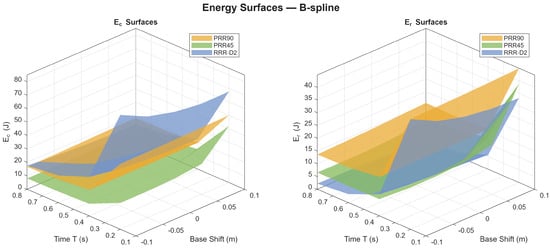

As previously said, several simulation runs were performed in order to evaluate the consumed energy and the potentially recoverable energy of the three robotic manipulators considered, by varying the two design variables described in Section 4. The simulations were performed in Matlab 2025b on a mobile workstation with 11th Gen Intel(R) Core(TM) i5-1135G7 (2.40 GHz) CPU. First of all, the results are here presented. Energy results are proposed for two sample trajectories, specifically the point-to-point trajectory with continuous velocity profile (cubic polynomial interpolation) and the B-spline trajectory. For the purpose of a comprehensive energy analysis, the results for all the trajectories are then reported in Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6. The 3D energy surface plots, which highlight the consumed and recoverable energies as a function of the design variables, are reported in Figure 5 and Figure 6.

Table 3.

Comparison of energy data for T = .

Table 4.

Comparison of energy data for T = .

Table 5.

Comparison of energy data for T = .

Table 6.

Comparison of energy data for T = .

Figure 5.

Consumed (left) and recoverable (right) energy of the studied manipulators for point-to-point motion with cubic polynomial interpolation.

Figure 6.

Consumed (left) and recoverable (right) energy of the studied manipulators for the B-spline trajectory.

The energy distribution obtained for the cubic trajectory highlights clear differences among the three manipulator architectures. The RRR-D2 system exhibits the highest energy demand, with consumed energy values exceeding 35 , mainly due to the need to counteract gravitational loads acting on its vertically oriented links. The coupled rotary joints require continuous torque delivery to sustain and accelerate the interconnected links, leading to greater inertial and gravitational effects. The recoverable energy follows a nearly proportional trend to , confirming that the actuation effort is closely related to the amount of energy that could theoretically be regenerated.

In contrast, the PRR90 configuration, equipped with vertical prismatic actuators, shows moderate energy requirements (up to approximately 16 ). In this case, the linear transmission reduces losses associated with rotary motion, yet the vertical alignment means that each actuator must still directly oppose the gravitational load throughout the motion. The PRR45 manipulator demonstrates the lowest energy consumption, remaining below 5 across all motion times. This improved efficiency arises from its 45° actuator orientation, since gravitational forces are projected along the rails. The load is effectively shared between the two prismatic actuators, reducing the equivalent effort to roughly half of the PRR90 and reflecting the inherently favorable mechanical leverage of the PRR45.

For the B-spline trajectory, the overall energy demand increases for all configurations compared to the cubic polynomial. In particular, the lifting of the payload but also the smoother yet more dynamic profile introduces higher instantaneous accelerations, leading to greater actuation torques as is visible in Figure 4b. The energy trends for the RRR-D2 ( ≈ 80 ), the PRR90 configuration (up to 50 ) and the PRR45 ( < 40 ) confirm the previously observed considerations about the benefiting from its 45° inclined rails, which project the gravitational force along the actuation axes and effectively share the load between actuators. For a more accurate comparison, the consumed and recoverable energy trends are further presented for all the three manipulators at four different sample times (T = 0.2 s, T = 0.4 s, T = 0.6 s, and T = 0.8 s) for the two sample trajectories in Figure 7 and Figure 8.

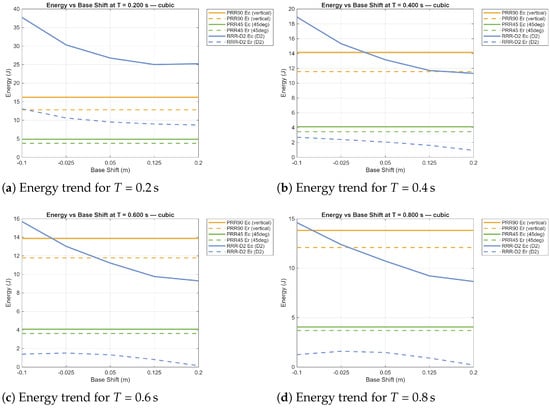

Figure 7.

Energy expenditure analysis results for the three manipulators on the first sample trajectory (point-to-point with cubic interpolation). = consumed energy; = recoverable energy.

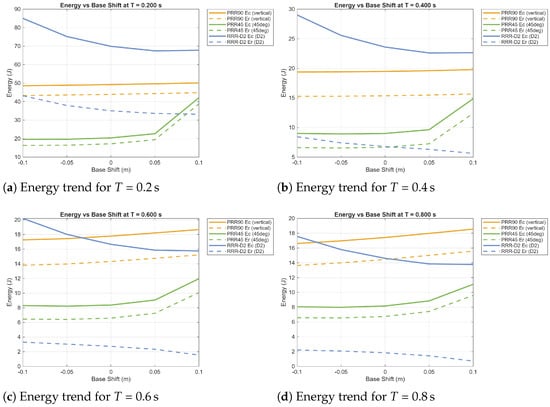

Figure 8.

Energy expenditure analysis results for the three manipulators on the second sample trajectory (B-spline). = consumed energy; = recoverable energy.

The energy trends for the cubic trajectory highlight clear differences among the three manipulators by varying the vertical displacement of the robot base. The RRR-D2 shows the highest energy consumption, with up to 35 for s and decreasing as the motion time increases. This behavior reflects the influence of gravitational and inertial loads on the rotary joints as also highlighted by the 3D energy plots. The downward trend with increasing suggests that certain configurations require lower joint torques due to more favorable postures. The recoverable energy remains much lower than the consumed one, indicating that most of the work compensates for gravity rather than being recoverable. Hence, compliant elements, e.g., optimal springs, could enhance the performance further.

In the PRR90 configuration, both and remain almost constant as the base is shifted, due to the vertical and parallel prismatic actuators, which operate primarily against gravity regardless of the position of the end-effector. The ratio between recoverable and consumed energy is higher than for the RRR-D2, as one actuator moves upward against gravity, while the other moves downward, partially balancing gravitational work.

The PRR45 shows the lowest and most stable energy values ( J, J). The 45° inclination of the prismatic axes reduces the vertical load component, allowing the actuators to share the gravitational effort, thus reducing total energy consumption.

Overall, the RRR-D2 remains the most energy-demanding configuration, while the PRR90 exhibits intermediate behavior and the PRR45 the most efficient energy performance due to its inclined geometry and balanced load distribution.

For the B-spline trajectory, the energy profiles show smoother variations with respect to but similar overall trends among the three manipulators. The RRR-D2 again displays the highest energy consumption, particularly at shorter motion times, where the influence of inertial loads dominates. Its decreases slightly as the base moves outward, while the recoverable energy remains minimal, confirming limited regenerative potential. The PRR90 exhibits moderate energy levels, with nearly linear and gently increasing and curves, mainly influenced by the continuous action of gravity on the vertical actuators. The PRR45 maintains the lowest energy demand, though both and increase more noticeably for positive , where the actuators operate at less favorable leverage angles. Overall, the B-spline trajectory confirms the energetic hierarchy already observed for the cubic trajectory RRR-D2 > PRR90 > PRR45, while emphasizing the smoother and more evenly distributed energy requirements by spline-based motion profiles.

As an additional assessment, the three planar manipulators are analyzed over a total operating period of one hour, with an idle interval of 1 inserted between consecutive cycles. The corresponding consumed and recoverable energies are then calculated for the entire time span, considering all four trajectories examined. The results for the four sample times, the same considered for the previous comparison plots, are shown in Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6. The reported results refer to a equal to 0 for all the three manipulators.

As a general observation, the energy consumption for the trajectories with point-to-point motion is very similar, while the B-spline trajectory-calculated consumption is higher, especially for fast motions, which produce higher TCP accelerations and velocities. The PRR45 manipulator consistently exhibits the lowest overall energy consumption across all motion profiles and time durations, followed by the PRR90 and finally the RRR-D2, which remains the most energy-demanding configuration. This hierarchy confirms the effect of geometry and joint type on the system’s energetic performance. For the B-spline trajectory, which most closely resembles an actual pick-and-place operation, the RRR-D2 shows the highest consumed energy values, particularly for shorter motion times (e.g., T = 0.2 s, with 210 kJ), while the PRR45 requires substantially less energy ( 64 kJ). The PRR90 presents intermediate results.

However, when considering recoverable energy, both PRR configurations, and especially the PRR90, demonstrate significantly higher potential for energy regeneration than the RRR-D2. For example, at T = 0.2 s, the recoverable energy of the PRR90 exceeds that of the RRR-D2 by nearly a factor of two. This indicates that, although the absolute consumption may be higher for certain trajectories, the symmetrical structure of the PRR manipulators enables a more efficient exchange of gravitational work between the two prismatic joints. Consequently, the integration of energy-recovery systems, such as regenerative braking drives, bidirectional power converters, or supercapacitor-based storage modules, could significantly enhance the overall energetic performance of the PRR manipulators. As said, this approach is particularly effective for the PRR architectures, where alternating actuator motion and symmetric load sharing produce frequent energy exchange.

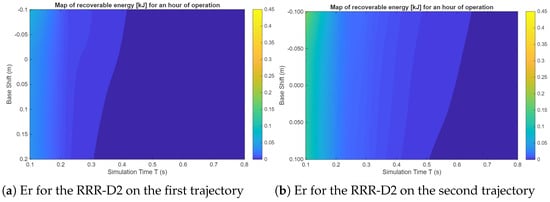

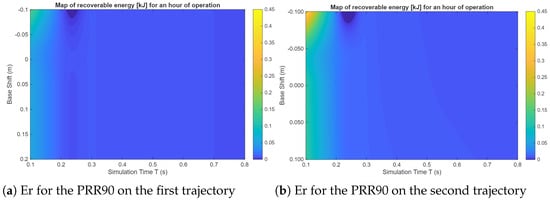

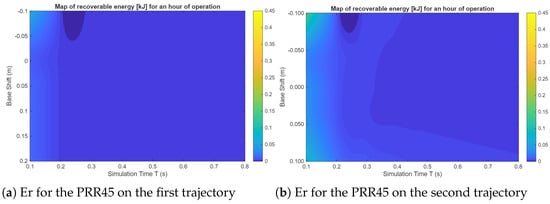

To conclude the results’ section, the potentially recoverable energy maps, calculated on the two sample trajectories for the three manipulators and as a function of T and , are displayed in Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11.

Figure 9.

Recoverable energy [kJ] maps for an hour of operation of the RRR-D2 manipulator.

Figure 10.

Recoverable energy [kJ] maps for an hour of operation of the PRR90 manipulator.

Figure 11.

Recoverable energy [kJ] maps for an hour of operation of the PRR45 manipulator.

As expected, shorter motion times correspond to higher recoverable energies due to increased accelerations and braking torques, which raise the magnitude of negative mechanical work in the actuators. In contrast, for longer cycle times, smoother velocity and torque profiles lead to limited opportunities for energy regeneration. The also influences the gravitational contribution to the joint torques: when the manipulator works above or below the neutral origin base configuration, the direction and magnitude of gravity change and affect the balance between positive and negative mechanical work.

For PRR architectures, small local minima appear close to the neutral (around zero), mainly at intermediate simulation times ( 0.3–0.4 s). These correspond to configurations where the prismatic actuators share the effort more evenly, which reduces the global potential energy variation of the links and therefore the recoverable energy. For higher vertical offsets, one actuator usually works against gravity while the other works with it, increasing the amount of energy that can be exchanged between them. On the other hand, the RRR-D2 manipulator shows a more monotonic reduction in recoverable energy when T increases, mostly dominated by inertia and joint torque symmetry rather than gravity effects. To conclude, these maps highlight that both motion timing and structural configuration have a strong influence on defining the robot capability to regenerate energy, offering important insight for the optimization of the workspace and trajectory planning in energy-efficient manipulator design.

6. Conclusions and Future Outlook

This work compared the energy performance of three planar parallel manipulators (RRR-D2, PRR90, and PRR45) performing pick-and-place tasks under different trajectory profiles. Through detailed kinematic, dynamic, and electro-mechanical modeling, both consumed and recoverable energy were assessed for varying motion duration and vertical displacement of the robot base. Results show that actuator orientation and geometry strongly affect energy efficiency: the PRR45 achieved the lowest overall consumption, the PRR90 offered the highest potential for energy recovery, while the RRR-D2 exhibited the greatest energy demand due to its rotary actuation and gravitational torque requirements.

As expected, the B-spline trajectories resulted in higher energy levels for all manipulators, as the lifting of the payload and the smoother but more dynamically demanding motion increases TCP accelerations and velocity gradients, amplifying joint torques through the manipulator Jacobian. The proportional relation between consumed and recoverable energy suggests that energy management strategies, particularly regenerative drives or storage-based recovery systems, could substantially improve efficiency. This is especially relevant for symmetric PRR architectures, where alternating actuator motions enable frequent regenerative phases.

The study is limited to numerical models and idealized actuator behavior; experimental validation is therefore required to capture non-linearities such as friction variability and mechanical backlash. Future work will focus on (i) substituting the rotary actuators and belt-driven transmissions in the PRR manipulators with linear actuators to reduce losses, (ii) validating the models and results experimentally, and (iii) developing control strategies and hardware for effective energy recovery.

Overall, the findings emphasize the role of manipulator geometry, actuator design, and trajectory planning in shaping the energy efficiency of robotic systems, providing a foundation for more sustainable automation solutions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology development: all literature review, writing of the manuscript, experimental setup, numerical modeling, simulation and data analysis: C.N. and V.G.; Supervision: R.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Renna, P.; Materi, S. A Literature Review of Energy Efficiency and Sustainability in Manufacturing Systems. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 7366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Ru, J. Goals of sustainable infrastructure, industry, and innovation: A review and future agenda for research. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 28446–28458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations. 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development-Sustainable Development Goals. 2025. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Muru, J.; Rassõlkin, A. A scoping review of energy consumption in industrial robotics. Machines 2025, 13, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Yan, J. A data-driven method for optimizing the energy consumption of industrial robots. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 285, 124862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naumann, M.; Ostermann, M.; Buchenau, N.; Oetzel, J.; Schlosser, F.; Meschede, H.; Tröster, T. Energy efficiency improvement for decarbonization in manufacturing industry: A review. Energy Convers. Manag. 2025, 338, 119763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carabin, G.; Palomba, I.; Wehrle, E.; Vidoni, R. Energy expenditure minimization for a delta-2 robot through a mixed approach. In Multibody Dynamics 2019; Computational Methods in Applied Sciences; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 53, pp. 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schüle, M.; Nehler, H.; Ottosson, M.; Thollander, P. Energy management in industry: A systematic review of previous findings and an integrative conceptual framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 3692–3708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soori, M.; Arezoo, B.; Dastres, R. Optimization of energy consumption in industrial robots, a review. Cogn. Robot. 2023, 3, 142–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balderas Hill, R.; Briot, S.; Chriette, A.; Martinet, P. Minimizing the Energy Consumption of a Delta Robot by Exploiting the Natural Dynamics. In ROMANSY 23–Robot Design, Dynamics and Control (CISM IFToMM Symposium); Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellicciari, M.; Berselli, G.; Leali, F.; Vergnano, A. A method for reducing the energy consumption of pick-and-place industrial robots. Mechatronics 2013, 23, 326–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Cheng, S.; Ding, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, S.; Xu, D.; Zhao, Y. A survey of optimization-based task and motion planning: From classical to learning approaches. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatronics 2024, 30, 2799–2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paes, K.; Dewulf, W.; Vander Elst, K.; Kellens, K.; Slaets, P. Energy efficient trajectories for an industrial ABB robot. Procedia CIRP 2014, 15, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paryanto; Brossog, M.; Bornschlegl, M.; Franke, J. Reducing the energy consumption of industrial robots in manufacturing systems. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2015, 78, 1315–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrinelli, S.; Borgia, S.; Pedrocchi, N.; Villagrossi, E.; Bianchi, G.; Tosatti, L.M. Minimization of the energy consumption in motion planning for single-robot tasks. Procedia CIRP 2015, 29, 354–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björkenstam, S.; Gleeson, D.; Bohlin, R.; Carlson, J.S.; Lennartson, B. Energy Efficient and Collision Free Motion of Industrial Robots using Optimal Control. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Automation Science and Engineering (CASE), Madison, WI, USA, 17–20 August 2013; pp. 510–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Xu, W.; Shang, J. Distributed-torque-based independent joint tracking control of a redundantly actuated parallel robot with two higher kinematic pairs. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2015, 63, 1062–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.V.; Wang, L. Energy-efficient trajectory planning for an industrial robot using a multi-objective optimisation approach. Procedia Manuf. 2018, 25, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadaleta, M.; Pellicciari, M.; Berselli, G. Optimization of the energy consumption of industrial robots for automatic code generation. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2019, 57, 452–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadaleta, M.; Berselli, G.; Pellicciari, M.; Grassia, F. Extensive experimental investigation for the optimization of the energy consumption of a high payload industrial robot with open research dataset. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2021, 68, 102046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra-Zubiaga, D.A.; Luong, K.Y. Energy consumption parameter analysis of industrial robots using design of experiment methodology. Int. J. Sustain. Eng. 2021, 14, 996–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baggetta, M.; Berselli, G.; Razzoli, R.; Zucchinetti, M. Energy efficient trajectory planning in robotic cells via virtual prototyping tools. In International Joint Conference on Mechanics, Design Engineering & Advanced Manufacturing; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 614–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Liu, H.; Yao, B.; Xu, W.; Yang, M. Energy consumption modeling of industrial robot based on simulated power data and parameter identification. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2018, 10, 1687814018773852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezzi, C.; Gufler, V.; Berger, A.; Vidoni, R. Energy expenditure comparison of planar robotic manipulators for pick-and-place operations. In Proceedings of I4SDG Workshop 2025-IFToMM for Sustainable Development Goals; Mechanisms and Machine Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; Volume 180, pp. 634–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carabin, G.; Wehrle, E.; Vidoni, R. A review on energy-saving optimization methods for robotic and automatic systems. Robotics 2017, 6, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boscariol, P.; Richiedei, D. Energy saving in redundant robotic cells: Optimal trajectory planning. In Mechanism Design for Robotics; Mechanisms and Machine Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 66, pp. 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabris, G.; Scalera, L.; Gasparetto, A. Dynamic modelling and energy-efficiency optimization in a 3-DOF parallel robot. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 132, 2677–2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balderas Hill, R.; Briot, S.; Chriette, A.; Martinet, P. Performing energy-efficient pick-and-place motions for high-speed robots by using variable stiffness springs. J. Mech. Robot. 2022, 14, 051004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco Vivas, A.; Cherubini, A.; Garabini, M.; Salaris, P.; Bicchi, A. Minimizing Energy Consumption of Elastic Robots in Repetitive Tasks. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2023, 53, 4235–4248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchal, M.; Furnémont, R.; Vanderborght, B.; Mostafaoui, G.; Verstraten, T. Optimization of Mono- and Bi-Articular Parallel Elastic Elements for a Robotic Arm Performing a Pick-and-Place Task. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2023, 8, 1234–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siciliano, B.; Sciavicco, L.; Villani, L.; Oriolo, G. Robotics: Modelling, Planning and Control; Springer: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezzi, C.; De Marchi, M.; Vidoni, R.; Rauch, E. A Multi-Purpose Simulation Layer for Digital Twin Applications in Mechatronic Systems. Machines 2025, 13, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- igus (Automation Division). 2-Axis Delta Robot. 2025. Available online: https://rbtx.com/en-US/components/robots/2-axis-delta-robot-pre-assembled-with-control-unit-working-space-diameter-700-mm?srsltid=AfmBOorVLWXIS3VIgvxpDuMry8rk7hx_BbrYUmBwH3rYLHCf5ewqiqdH (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- Carabin, G.; Scalera, L.; Wongratanaphisan, T.; Vidoni, R. An energy-efficient approach for 3D printing with a Linear Delta Robot equipped with optimal springs. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2021, 67, 102045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).