MultiPhysio-HRC: A Multimodal Physiological Signals Dataset for Industrial Human–Robot Collaboration

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Works

3. MultiPhysio-HRC

3.1. Experimental Protocol

3.1.1. Day 1—Baseline and Stress Induction

- 1.

- Rest: The participant sits comfortably for two minutes and is invited to relax without specific instructions.

- 2.

- Cognitive tasks. The participant sits in front of a computer screen, using a keyboard and mouse to interact with different games aimed at increasing their cognitive load and eliciting psychological stress. The selected tasks are:

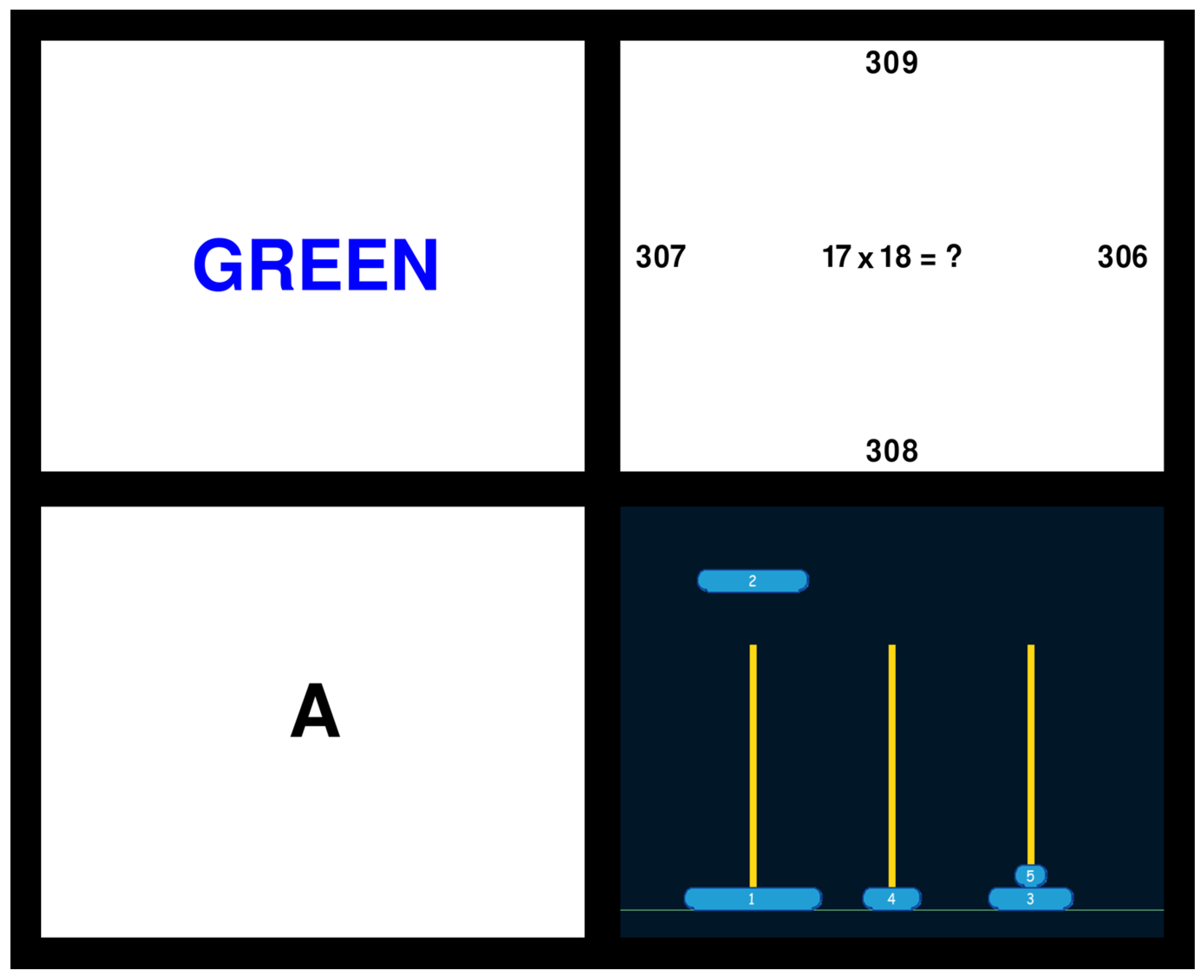

- (a)

- Stroop Color Word Test (SCWT) [16] (three minutes). Color names (e.g., “RED”) appear in different colors. The participants must push the keyboard button corresponding to the color of the displayed letters (e.g., “B” if the word “RED” is written in Blue characters). The task was performed with two difficulty levels: one second and half a second to answer.

- (b)

- N-Back task [17] (two minutes). A single letter is shown on the screen every two seconds. The participant must press a key whenever the letter is equal to the N-th previous letter.

- (c)

- Mental Arithmetic Task (two minutes). The participant must perform a mental calculation in three seconds and press an arrow key, selecting the correct answer among four possibilities.

- (d)

- Hanoi Tower [18]. The participant must rebuild the tower in another bin, without placing a larger block over a smaller one. There was no time constraint on this task.

- (e)

- Breathing exercise (two minutes). A voice-guided controlled breathing exercise.

The order of these tasks was randomly chosen for each participant. A representation of the displayed screen is shown in Figure 2. During the execution of these tasks (except the Hanoi tower and the breathing exercise), a ticking clock sound was reproduced to arouse a sense of hurry, and a buzzer sound was played in case of mistakes, to increase the psychological stress. - 3.

- VR games. Finally, participants performed immersive tasks in virtual reality environments such as Richie’s Plank Experience (https://store.steampowered.com/app/517160/Richies_Plank_Experience/, accessed on 2 December 2025) to elicit a high-intensity psycho-physical state. In this game, participants had to walk on a bench suspended on top of a building.

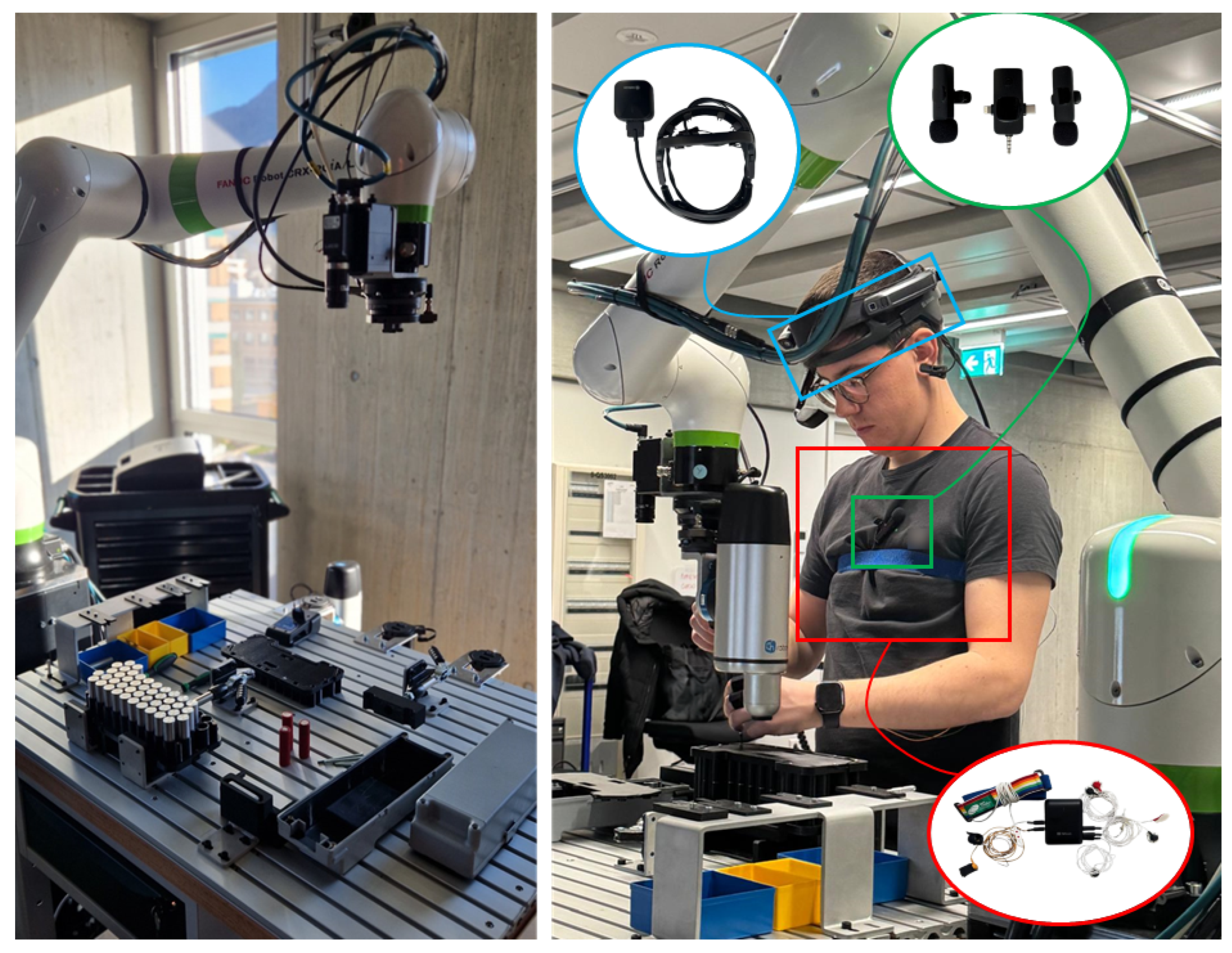

3.1.2. Day 2—Manual and Robot-Assisted Tasks

- Rest. The participant sits comfortably for five minutes and is invited to relax without specific instructions.

- Manual disassembly. The participant uses bare hands or simple tools to partially disassemble an e-bike battery pack.

- Collaborative disassembly. The participant is given instructions about how to interact with the robot by voice commands. Then, they perform the same disassembly by asking the cobot to perform support or parallel operations. The voice commands are not only used to give instructions to the robot naturally, but are also opportunities to collect voice data and observe human–robot dynamics under operational conditions.

3.2. Task and Robotic Cell Description

3.3. Participants

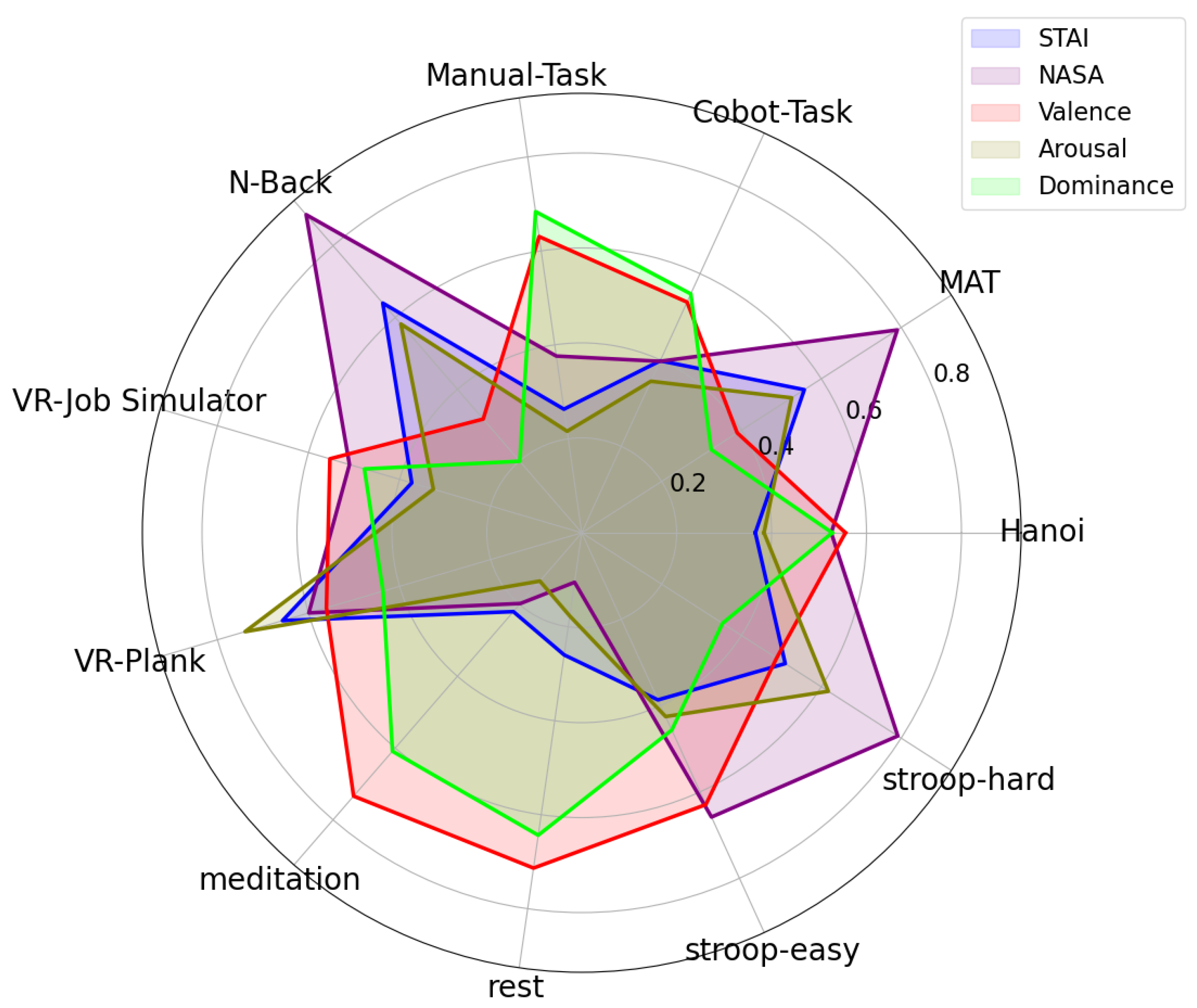

3.4. Ground Truth

- The Stress Trait Anxiety Inventory-Y1 (STAI-Y1) [22] consists of 20 questions that measure the subjective feeling of apprehension and worry, and it is often used as a stress measurement.

- The NASA Task Load Index (NASA-TLX) [23] measures self-reported workload and comprises six metrics (mental demand, physical demand, temporal demand, performance, effort, and frustration level).

- The Self-Assessment Manikin (SAM) [24] assesses participant valence, arousal, and dominance levels. The scale used in this dataset is from one to five.

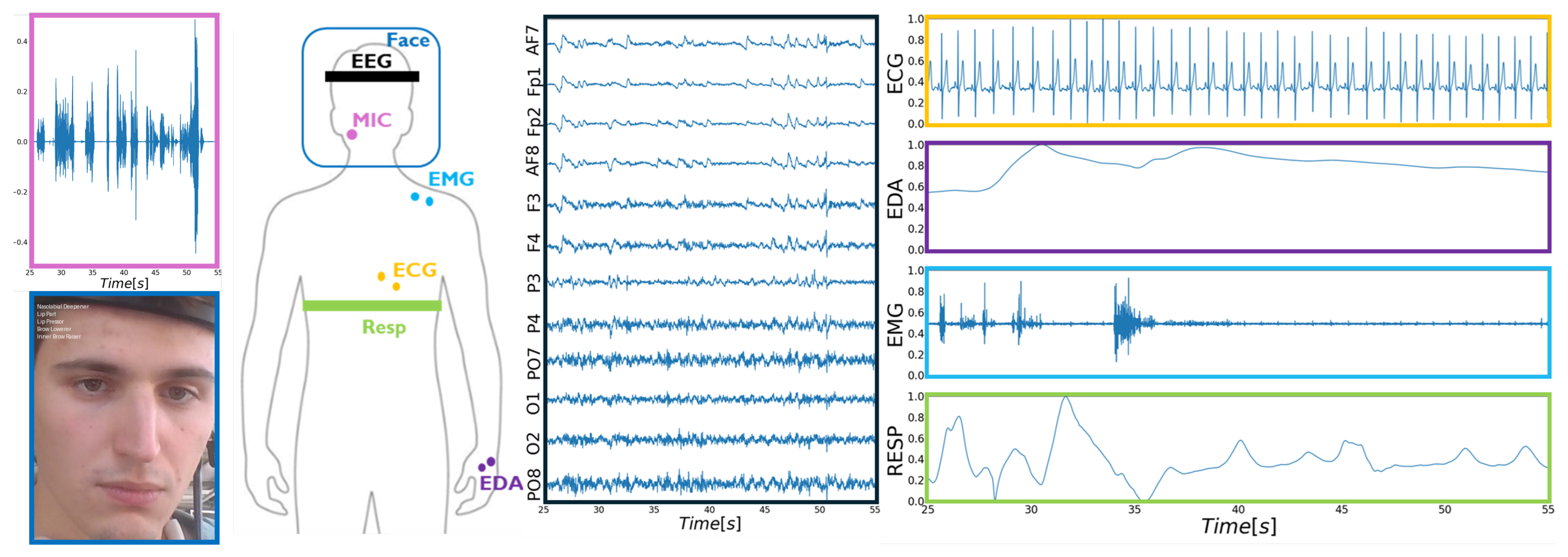

3.5. Acquired Data

4. Methods

4.1. Data Processing

4.2. Features Extraction

4.2.1. Physiological Data

4.2.2. Face Action Units

4.2.3. Voice Features

4.2.4. Text Embeddings

5. Results

6. Discussion

- Real-World HRC Context: To the best of our knowledge, MultiPhysio-HRC is the first publicly available dataset to include realistic industrial-like HRC scenarios comprehensively.

- Complete Multimodal Data: While existing datasets often include subsets of modalities, MultiPhysio-HRC integrates facial features, audio, and a comprehensive set of physiological signals: EEG, ECG, EDA, RESP, and EMG. This combination allows for a holistic assessment of mental states, addressing cognitive load, stress, and emotional dimensions.

- Task Diversification: The dataset comprises tasks specifically designed to elicit various mental states. These include cognitive tests, immersive VR activities, and industrial tasks.

- Rich Ground Truth Annotations: Ground truth labels were collected through validated psychological questionnaires at multiple stages during the experiment. Combined with multimodal measurements, these labels offer unparalleled granularity for studying human states in HRC contexts.

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AB | AdaBoost |

| ASR | Automatic Speech Recognition |

| AU | Action Unit |

| DFT | Discrete Fourier Transform |

| ECG | Electrocardiography |

| EDA | Electrodermal Activity |

| EEG | Electroencephalography |

| EMG | Electromyography |

| GSR | Galvanic Skin Response |

| HRC | Human–Robot Collaboration |

| MFCC | Mel-Frequency Cepstral Coefficients |

| NASA-TLX | NASA Task Load Index |

| NARS | Negative Attitudes Toward Robots Scale |

| PANAS | Positive and Negative Affect Schedule |

| PSD | Power Spectral Density |

| RESP | Respiration |

| RF | Random Forest |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| SAM | Self-Assessment Manikin |

| SENIAM | Surface EMG for Non-Invasive Assessment of Muscles |

| SSSQ | Short Stress State Questionnaire |

| STAI-Y1 | State–Trait Anxiety Inventory, Form Y-1 |

| SUPSI | University of Applied Sciences and Arts of Southern Switzerland |

| USI | Università della Svizzera italiana |

| VAD | Voice Activity Detection |

| VR | Virtual Reality |

| XGB | XGBoost (Extreme Gradient Boosting) |

Appendix A

| Signal | Domain | Features |

|---|---|---|

| ECG (HRV) | Time | MeanNN, SDNN, RMSSD, SDSD, CVNN, CVSD, MedianNN, MadNN, MCVNN, IQRNN, Prc20NN, Prc80NN, pNN50, pNN20, MinNN, MaxNN, HTI, TINN |

| Frequency | ULF, VLF, LF, HF, VHF, LFHF, LFn, HFn, LnHF | |

| Nonlinearity | SD1, SD2, SD1SD2, S, CSI, CVI, CSI_Modified, PIP, IALS, PSS, PAS, GI, SI, AI, PI, C1d, C1a, SD1d, SD1a, C2d, C2a, SD2d, SD2a, Cd, Ca, SDNNd, SDNNa, DFA_alpha1, MFDFA_alpha1_Width, MFDFA_alpha1_Peak, MFDFA_alpha1_Mean, MFDFA_alpha1_Max, MFDFA_alpha1_Delta, MFDFA_alpha1_Asymmetry, MFDFA_alpha1_Fluctuation, MFDFA_alpha1_Increment, ApEn, SampEn, ShanEn, FuzzyEn, MSEn, CMSEn, RCMSEn, CD, HFD, KFD, LZC | |

| EDA | Time | Mean, SD, Kurtosis, Skewness, Mean Derivative, Mean Negative Derivative, Activity, Mobility, Complexity, Peaks Count, Mean Peaks Amplitude, Mean Rise Time, Sum Peaks Amplitude, Sum of Rise Time, SMA |

| Frequency | Energy, Spectral Power, Energy Wavelet lv1–lv4, total Energy Wavelet, Energy Distribution lv1–lv4, Mean MFCCs 1–20, SD MFCCs 1–20, Median MFCCs 1–20, Kurtosis MFCCs 1–20, Skewness MFCCs 1–20 | |

| Nonlinearity | ApEn, SampEn, ShanEn, FuzzEn, MSE, CMSE, RCMSE, Entropy Wavelet lv1–lv4 | |

| EMG | Time | RMSE, MAV, VAR |

| Frequency | Energy, MNF, MDF, ZC, FR, DWT_MAV_1–4, DWT_STD_1–4 | |

| Nonlinearity | – | |

| RESP | Time | Mean, Max, Min, RAV_Mean, RAV_SD, RAV_RMSSD, RAV_CVSD, Symmetry_PeakTrough_Mean, Median, Max, Min, Std, Symmetry_RiseDecay_Mean, Median, Max, Min, Std, RRV_RMSSD, RRV_MeanBB, RRV_SDBB, RRV_SDSD, RRV_CVBB, RRV_CVSD, RRV_MedianBB, RRV_MadBB, RRV_MCVBB |

| Frequency | RRV_VLF, RRV_LF, RRV_HF, RRV_LFHF, RRV_LFn, RRV_HFn | |

| Nonlinearity | RRV_SD1, RRV_SD2, RRV_SD2SD1, RRV_ApEn, RRV_SampEn |

References

- Lorenzini, M.; Lagomarsino, M.; Fortini, L.; Gholami, S.; Ajoudani, A. Ergonomic human-robot collaboration in industry: A review. Front. Robot. AI 2023, 9, 813907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Zheng, H.; Chand, S.; Xia, W.; Liu, Z.; Xu, X.; Wang, L.; Qin, Z.; Bao, J. Outlook on human-centric manufacturing towards Industry 5.0. J. Manuf. Syst. 2022, 62, 612–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, A.; Pavesi, G.; Zamboni, M.; Carpanzano, E. Deliberative robotics – a novel interactive control framework enhancing human-robot collaboration. CIRP Ann. 2022, 71, 21–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spezialetti, M.; Placidi, G.; Rossi, S. Emotion Recognition for Human-Robot Interaction: Recent Advances and Future Perspectives. Front. Robot. AI 2020, 7, 532279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinisch, J.S.; Kirchhoff, J.; Busch, P.; Wendt, J.; von Stryk, O.; David, K. Physiological data for affective computing in HRI with anthropomorphic service robots: The AFFECT-HRI data set. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamantini, C.; Laura Cristofanelli, M.; Fracasso, F.; Umbrico, A.; Cortellessa, G.; Orlandini, A.; Cordella, F. Physiological Sensor Technologies in Workload Estimation: A Review. IEEE Sens. J. 2025, 25, 34298–34310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, J.; Picard, R. Detecting Stress During Real-World Driving Tasks Using Physiological Sensors. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2005, 6, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, P.; Reiss, A.; Duerichen, R.; Marberger, C.; Van Laerhoven, K. Introducing WESAD, a Multimodal Dataset for Wearable Stress and Affect Detection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 20th ACM International Conference on Multimodal Interaction, Boulder, CO, USA, 2 October 2018; pp. 400–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsigiannis, S.; Ramzan, N. DREAMER: A Database for Emotion Recognition Through EEG and ECG Signals From Wireless Low-cost Off-the-Shelf Devices. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2018, 22, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, P.; Posen, A.; Etemad, A. AVCAffe: A Large Scale Audio-Visual Dataset of Cognitive Load and Affect for Remote Work. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2023, 37, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaptoukaev, H.; Strizhkova, V.; Panariello, M.; Dalpaos, B.; Reka, A.; Manera, V.; Thümmler, S.; Ismailova, E.; Nicholas, W.; Bremond, F.; et al. StressID: A Multimodal Dataset for Stress Identification. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Oh, A., Naumann, T., Globerson, A., Saenko, K., Hardt, M., Levine, S., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2023; Volume 36, pp. 29798–29811. [Google Scholar]

- SenseCobot. SenseCobot. 2023. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/8363762 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Borghi, S.; Ruo, A.; Sabattini, L.; Peruzzini, M.; Villani, V. Assessing operator stress in collaborative robotics: A multimodal approach. Appl. Ergon. 2025, 123, 104418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussolan, A.; Baraldo, S.; Gambardella, L.M.; Valente, A. Assessing the Impact of Human-Robot Collaboration on Stress Levels and Cognitive Load in Industrial Assembly Tasks. In Proceedings of the ISR Europe 2023, 56th International Symposium on Robotics, Stuttgart, Germany, 26–27 September 2023; pp. 78–85. [Google Scholar]

- Nenna, F.; Zanardi, D.; Orlando, E.M.; Nannetti, M.; Buodo, G.; Gamberini, L. Getting Closer to Real-world: Monitoring Humans Working with Collaborative Industrial Robots. In Proceedings of the Companion of the 2024 ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction, New York, NY, USA, 11 March 2024; HRI ’24. pp. 789–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarpina, F.; Tagini, S. The Stroop Color and Word Test. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meule, A. Reporting and Interpreting Working Memory Performance in n-back Tasks. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidtke, K. Tower of Hanoi Problem. In The Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avram, O.; Fasana, C.; Baraldo, S.; Valente, A. Advancing Human-Robot Collaboration by Robust Speech Recognition in Smart Manufacturing. In Proceedings of the European Robotics Forum 2024; Secchi, C., Marconi, L., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 168–173. [Google Scholar]

- Bansod, Y.; Patra, S.; Nau, D.; Roberts, M. HTN Replanning from the Middle. Int. FLAIRS Conf. Proc. 2022, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, D.; Sucan, I.; Chitta, S.; Correll, N. Reducing the barrier to entry of complex robotic software: A moveit! case study. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1404.3785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spielberger, C.; Gorsuch, R. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (form Y) (“Self-Evaluation Questionnaire”); Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, S.G.; Staveland, L.E. Development of NASA-TLX (Task Load Index): Results of Empirical and Theoretical Research. In Advances in Psychology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1988; Volume 52, pp. 139–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, M.M.; Lang, P.J. Measuring emotion: The self-assessment manikin and the semantic differential. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 1994, 25, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, T.; Kanda, T.; Suzuki, T.; Kato, K. Psychology in Human-Robot Communication: An Attempt through Investigation of Negative Attitudes and Anxiety toward Robots. In Proceedings of the RO-MAN 2004, 13th IEEE International Workshop on Robot and Human Interactive Communication (IEEE Catalog No.04TH8759), Kurashiki, Okayama, Japan, 22–22 September 2004; pp. 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loizaga, E.; Bastida, L.; Sillaurren, S.; Moya, A.; Toledo, N. Modelling and Measuring Trust in Human–Robot Collaboration. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stegeman, D.F.; Hermens, H.J. Standards for Surface Electromyography: The European Project “Surface EMG for Non-Invasive Assessment of Muscles (SENIAM)”. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/398119434_Preparatory_use_of_neurodynamics_to_enhance_upper_limb_function_in_patients_with_acquired_brain_injury_a_randomized_controlled_trial (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Greco, A.; Valenza, G.; Lanata, A.; Scilingo, E.; Citi, L. cvxEDA: A Convex Optimization Approach to Electrodermal Activity Processing. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2016, 63, 797–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makowski, D.; Pham, T.; Lau, Z.J.; Brammer, J.C.; Lespinasse, F.; Pham, H.; Schölzel, C.; Chen, S.H.A. NeuroKit2: A Python toolbox for neurophysiological signal processing. Behav. Res. Methods 2021, 53, 1689–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.; Lau, Z.J.; Chen, S.H.A.; Makowski, D. Heart Rate Variability in Psychology: A Review of HRV Indices and an Analysis Tutorial. Sensors 2021, 21, 3998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orguc, S.; Khurana, H.S.; Stankovic, K.M.; Leel, H.; Chandrakasan, A. EMG-based Real Time Facial Gesture Recognition for Stress Monitoring. In Proceedings of the 2018 40th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), Honolulu, HI, USA, 18–21 July 2018; pp. 2651–2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, J.; Barreda-Angeles, M.; Oliver, J.; Nandi, G.C.; Puig, D. Feature Extraction and Selection for Emotion Recognition from Electrodermal Activity. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2021, 12, 857–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raufi, B.; Longo, L. An Evaluation of the EEG Alpha-to-Theta and Theta-to-Alpha Band Ratios as Indexes of Mental Workload. Front. Neuroinformatics 2022, 16, 861967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, P. The use of fast Fourier transform for the estimation of power spectra: A method based on time averaging over short, modified periodograms. IEEE Trans. Audio Electroacoust. 1967, 15, 70–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, J.H.; Jolly, E.; Xie, T.; Byrne, S.; Kenney, M.; Chang, L.J. Py-Feat: Python Facial Expression Analysis Toolbox. Affect. Sci. 2023, 4, 781–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Team, S. Silero VAD: Pre-trained enterprise-grade Voice Activity Detector (VAD), Number Detector and Language Classifier. 2021. Available online: https://github.com/snakers4/silero-vad (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Tomba, K.; Dumoulin, J.; Mugellini, E.; Abou Khaled, O.; Hawila, S. Stress Detection Through Speech Analysis. In Proceedings of the 15th International Joint Conference on e-Business and Telecommunications, Porto, Portugal, 26–28 July 2018; pp. 394–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Xu, T.; Brockman, G.; McLeavey, C.; Sutskever, I. Robust speech recognition via large-scale weak supervision. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Honolulu, HI, USA, 23–29 July 2023; pp. 28492–28518. [Google Scholar]

- Reimers, N.; Gurevych, I. Sentence-BERT: Sentence Embeddings using Siamese BERT-Networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Association for Computational Linguistics, Hong Kong, China, 3–7 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Procopio, N. sentence-bert-base-italian-xxl-cased. Available online: https://huggingface.co/nickprock/sentence-bert-base-italian-xxl-uncased (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freund, Y.; Schapire, R.E. A Decision-Theoretic Generalization of On-Line Learning and an Application to Boosting. J. Comput. Syst. Sci. 1997, 55, 119–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; KDD ‘16’. pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussolan, A.; Baraldo, S.; Gambardella, L.M.; Valente, A. Multimodal fusion stress detector for enhanced human-robot collaboration in industrial assembly tasks. In Proceedings of the 2024 33rd IEEE International Conference on Robot and Human Interactive Communication (ROMAN), Pasadena, CA, USA, 26–30 August 2024; pp. 978–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dataset | Scenario/Context | Modalities | Target Constructs | Ground Truth | # Part. | Limitations w.r.t. HRC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healey (2005) [7] | Real-world driving | ECG, EDA, EMG, RESP | Driver stress | Road segment stress labels | 24 | Driving only; no collaborative or industrial tasks |

| WESAD [8] | Three different affective states (TSST, amusement, neutral) | ECG, EDA, EMG, RESP, temperature, acceleration | Stress and affect | PANAS, SAM, STAI, SSSQ | 15 | Wearable setting; no physical collaboration or robot interaction |

| DREAMER [9] | Audiovisual emotion elicitation in lab | EEG, ECG | Valence, arousal, dominance | SAM | 23 | No workload or HRC tasks; short passive stimuli only |

| AVCAffe [10] | Remote collaborative work via video conferencing | Facial video, audio, physiological signals | Cognitive load, affect | Cognitive load and V/A annotations | 106 | Remote setting; no physical tasks or shared workspace with robots |

| StressID [11] | Breathing, emotional video clips, cognitive and speech tasks | ECG, EDA, RESP, facial video, audio | Stress and affect | NASA–TLX, SAM | 65 | Broad lab tasks, but no human–robot collaboration |

| SenseCobot [12,13] | Collaborative robot programming in a simulated industrial cell | EEG, ECG, GSR, facial expressions | Stress | NASA–TLX | 21 | Focus on programming; no physical collaboration |

| MultiPhysio-HRC (ours) | Manual and robot-assisted battery disassembly, cognitive tests, immersive VR tasks | EEG, ECG, EDA, EMG, RESP, facial AUs, audio features | Stress, cognitive load, affect, attitudes toward robots | STAI-Y1, NASA–TLX, SAM, NARS | 36 | First dataset combining rich multimodal physiology with realistic industrial HRC and disassembly workflows |

| Response | Signal | Model | RMSE |

|---|---|---|---|

| STAI-Y1 , | Physio | RF | |

| AB | |||

| XGB | |||

| EEG

| RF | ||

| AB | |||

| XGB | |||

| Voice | RF | ||

| AB | |||

| XGB | |||

| NASA-TLX , | Physio | RF | |

| AB | |||

| XGB | |||

| EEG | RF | ||

| AB | |||

| XGB | |||

| Voice | RF | ||

| AB | |||

| XGB |

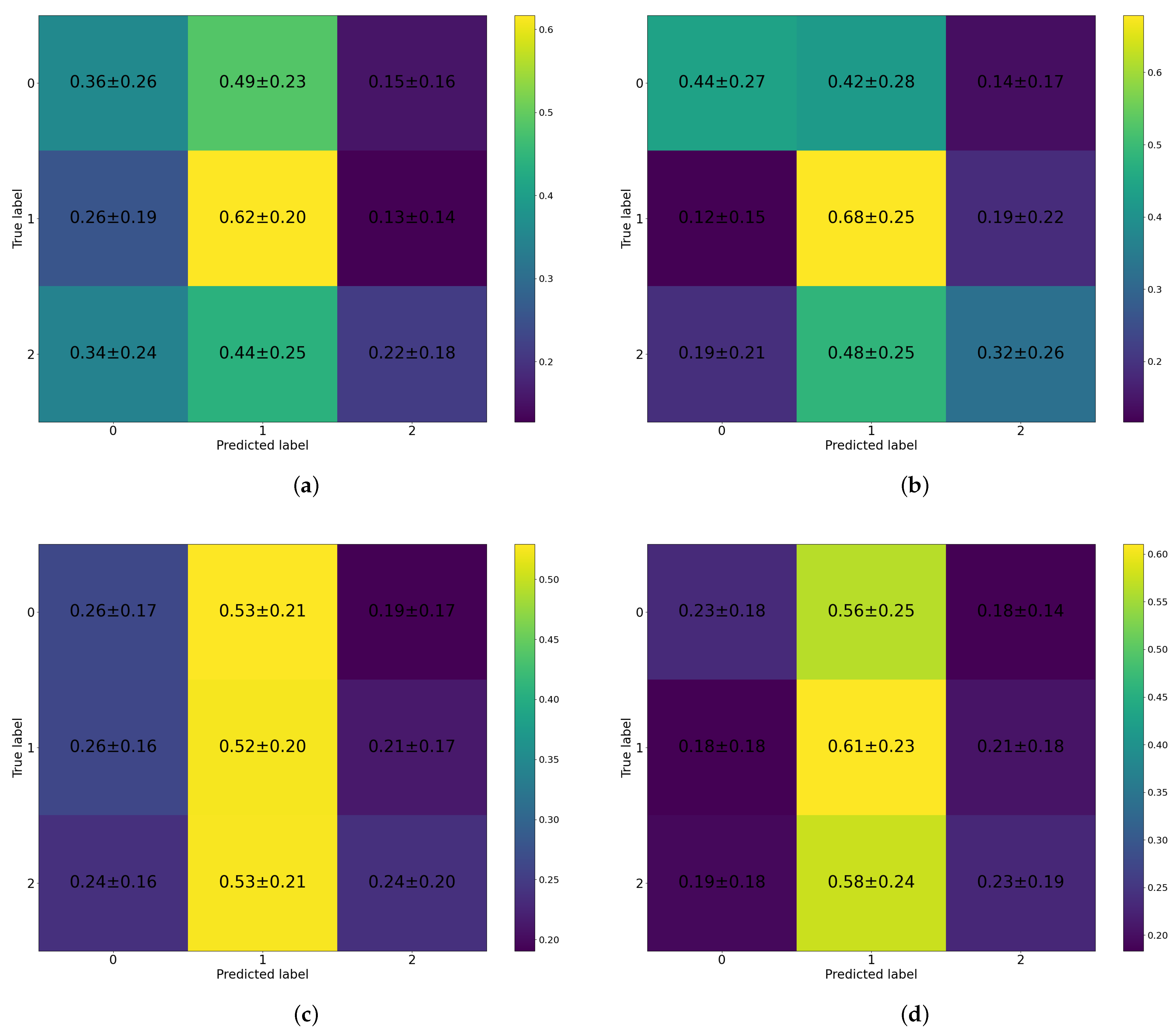

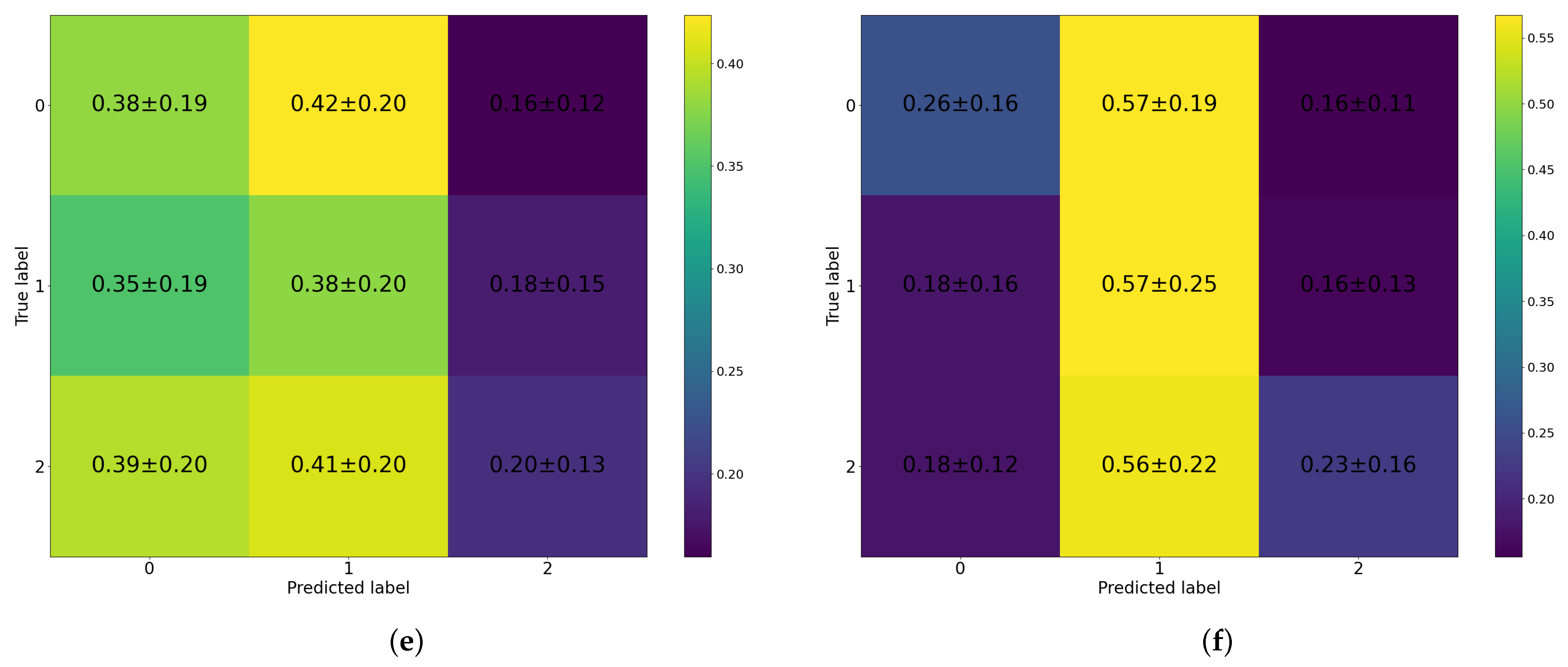

| Response | Signal | Model | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stress Class | Physio | RF | |

| AB | |||

| XGB | |||

| EEG | RF | ||

| AB | |||

| XGB | |||

| Voice | RF | ||

| AB | |||

| XGB | |||

| Cognitive Load Class | Physio | RF | |

| AB | |||

| XGB | |||

| EEG | RF | ||

| AB | |||

| XGB | |||

| Voice | RF | ||

| AB | |||

| XGB |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bussolan, A.; Baraldo, S.; Avram, O.; Urcola, P.; Montesano, L.; Gambardella, L.M.; Valente, A. MultiPhysio-HRC: A Multimodal Physiological Signals Dataset for Industrial Human–Robot Collaboration. Robotics 2025, 14, 184. https://doi.org/10.3390/robotics14120184

Bussolan A, Baraldo S, Avram O, Urcola P, Montesano L, Gambardella LM, Valente A. MultiPhysio-HRC: A Multimodal Physiological Signals Dataset for Industrial Human–Robot Collaboration. Robotics. 2025; 14(12):184. https://doi.org/10.3390/robotics14120184

Chicago/Turabian StyleBussolan, Andrea, Stefano Baraldo, Oliver Avram, Pablo Urcola, Luis Montesano, Luca Maria Gambardella, and Anna Valente. 2025. "MultiPhysio-HRC: A Multimodal Physiological Signals Dataset for Industrial Human–Robot Collaboration" Robotics 14, no. 12: 184. https://doi.org/10.3390/robotics14120184

APA StyleBussolan, A., Baraldo, S., Avram, O., Urcola, P., Montesano, L., Gambardella, L. M., & Valente, A. (2025). MultiPhysio-HRC: A Multimodal Physiological Signals Dataset for Industrial Human–Robot Collaboration. Robotics, 14(12), 184. https://doi.org/10.3390/robotics14120184