1. Introduction and Background Review

Robust and reliable perception is fundamental to autonomous driving, particularly in complex urban environments, where occlusions and limited sensor range often degrade situational awareness. Collaborative perception (CP) among multiple connected vehicles has emerged as an effective paradigm to overcome these challenges. By allowing vehicles to share complementary information, CP enables a more comprehensive understanding of the surrounding environment, extending visibility beyond line-of-sight and improving the detection of partially occluded objects.

Early CP studies primarily explored sharing raw sensor data, such as LiDAR point clouds, to enhance perception coverage [

1]. However, the enormous bandwidth demand and the latency of raw data transmission quickly rendered this approach impractical for real-time deployment. Later research revealed that the effectiveness of collaboration depends critically on balancing information richness and communication efficiency, motivating the development of hierarchical fusion strategies that progressively optimize this trade-off. Despite steady progress, two fundamental challenges continue to hinder the scalability and practicality of CP systems: communication overhead and agent heterogeneity. The bandwidth required to transmit high-dimensional feature maps remains substantial, especially under real-time constraints and bandwidth-limited V2X networks. To alleviate this issue while preserving perceptual richness, intermediate feature-level fusion has become the mainstream strategy in recent research [

2,

3,

4,

5]. Methods such as Where2comm [

6] further refine this paradigm by transmitting only the most informative spatial regions, thereby minimizing redundancy. Nevertheless, these methods primarily target communication reduction and assume identical perception backbones across agents. In parallel, heterogeneity across sensor modalities, network architectures, and feature distributions presents an additional challenge for collaborative fusion. In real-world fleets, vehicles differ widely in sensing modalities (e.g., LiDAR, radar, or cameras) and perception backbones of varying depth and capacity, yet most existing frameworks still assume homogeneity or require costly retraining to integrate new agent types. The coexistence of these two constraints makes it difficult to design a CP system that is both communication-efficient and robust to heterogeneity.

Existing approaches often tackle these challenges independently. For instance, codebook-based methods such as CodeFilling [

7] reduce the communication load by transmitting compact integer codes, whereas transformer-based frameworks like V2X-ViT [

8] implicitly learn to fuse heterogeneous features through attention mechanisms. Other works, including MPDA [

9] and PolyInter [

10], attempt to bridge domain gaps using interpreters or prompt-driven modules but still incur additional communication or training overhead. Consequently, a unified framework that simultaneously achieves bandwidth efficiency and architectural adaptability remains an open research problem.

This research contributes a collaborative perception framework that supports heterogeneous agents—vehicles with diverse perception backbones and sensor modalities—while maintaining communication efficiency. We pursue this goal through a modular design that combines prompt-based feature adaptation with compact message encoding, inspired by recent advances in transformer-based fusion [

10]. By embedding a compression mechanism [

7] within a heterogeneous collaboration pipeline, we establish a practical testbed for investigating prompt-driven bandwidth-aware perception across diverse agents. In particular, this work extends compressed communication to heterogeneous setups not only in sensor modality but also in perception architecture, providing a unified foundation for scalable and efficient collaborative perception. Overall, this framework advances the pursuit of scalable, bandwidth-efficient, and adaptable multi-agent perception for next-generation connected and autonomous vehicles.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews the related work in collaborative perception and communication-efficient feature sharing.

Section 3 presents the proposed extensible heterogeneous framework, including feature extraction, codebook compression, prompt-guided decoding, and fusion.

Section 4 describes the experimental setup, datasets, and implementation details.

Section 5 reports the quantitative and qualitative results, followed by ablation studies. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the paper and discusses future research directions. The code is available at:

https://github.com/Babak-Ebrahimi/PolyCode (accessed on 4 December 2025).

2. Related Work

2.1. Collaborative Perception Paradigms

Collaborative perception (CP) enables multiple connected agents, such as vehicles or infrastructure units, to exchange sensory information and extend their field of view, thereby improving perception accuracy and decision-making. Depending on how information is shared, CP can be categorized into three paradigms: early, intermediate, and late fusion [

11].

Early fusion transmits raw sensor data (e.g., LiDAR point clouds or camera images), providing high-fidelity details at the cost of excessive bandwidth and latency. Late fusion, in contrast, exchanges only final detection results, significantly reducing the communication cost but often sacrificing perceptual completeness. Intermediate fusion has emerged as a balanced solution between these two extremes, where agents exchange mid-level feature representations, typically in bird’s-eye view (BEV) format, to achieve efficient, yet informative, cooperation [

3,

5,

12].

Despite its success, traditional intermediate fusion methods generally assume a homogeneous environment in which all agents employ the same backbone network and sensor modality. This assumption simplifies the feature alignment but limits the scalability and adaptability in real-world heterogeneous scenarios.

2.2. Communication-Efficient Feature Sharing

Due to the high dimensionality of BEV features, reducing communication overhead has been a central research objective in collaborative perception. Where2comm introduces spatial confidence maps to identify and transmit only the most informative regions, effectively reducing redundant communication [

6]. Luo et al. [

13] proposed CRCNet to minimize redundancy among shared features by modeling feature complementarity between agents. Unlike sparsification-based methods that discard low-confidence regions, CodeFilling [

7] preserves the complete feature space in a compressed form, enabling efficient reconstruction at the receiver side. To further improve compression, CodeFilling [

7] proposes a codebook-based quantization mechanism that transforms high-dimensional features into compact integer codes. This approach dramatically decreases the transmission bandwidth while maintaining the detection accuracy. However, its current design assumes homogeneous collaboration, where all agents share identical encoder’s output dimensions and operate in the same feature domain. This constraint limits its scalability in heterogeneous setups with diverse backbones and modalities.

2.3. Heterogeneous Collaborative Perception

Heterogeneous collaborative perception (HCP) extends CP to scenarios where agents differ in sensor modality, network architecture, or downstream task. Such heterogeneity introduces nontrivial domain gaps in the feature space, making direct fusion challenging. Several frameworks have been developed to address these gaps. Multi-agent Perception Domain Adaptation (MPDA) [

9] employs learnable feature resizers and cross-domain transformers to align intermediate feature representations among agents. Although effective, MPDA requires supervised adaptation for each new agent pair, which limits scalability. The Polymorphic Feature Interpreter (PolyInter) [

10] mitigates this issue by introducing a shared transformer backbone equipped with lightweight learnable prompts that encode agent-specific information. These prompts guide feature interpretation without retraining the core model, enabling scalable one-stage integration of heterogeneous features. While PolyInter demonstrates strong performance across varying sensor types and backbone networks, it requires the transmission of full-resolution feature maps, leaving communication efficiency an open challenge.

2.4. Toward Unified Efficiency and Generalization

Recent studies have underscored the need for frameworks that jointly address communication constraints and architectural heterogeneity [

11]. While CodeFilling [

7] achieves impressive compression through discrete feature quantization, and PolyInter [

10] enables scalable interpretation across diverse agents, these two capabilities have yet to be unified. This gap motivates our work, which aims to extend codebook-based compression to heterogeneous CP settings through prompt-guided feature interpretation. Our proposed framework integrates the compression efficiency of CodeFilling with the generalization capability of PolyInter, enabling lightweight, one-stage, and heterogeneity-aware collaborative perception. By combining compact message encoding with prompt-based adaptation, the framework offers a unified solution that is both communication-efficient and robust to variations in sensor modality and perception architecture.

3. Methodology

To enable scalable and bandwidth-efficient collaborative perception among heterogeneous agents, we propose a unified framework that couples codebook-based compression for transmission with prompt-guided interpretation for domain adaptation. Each agent may use a distinct encoder backbone and sensor modality, yet still contribute informative intermediate features for fusion under tight communication budgets. The central difficulty is aligning heterogeneous semantically diverse features emitted by fixed encoders. Direct fusion is unreliable because the channel dimensionality, spatial resolution, and representational semantics generally differ across agents. To address this, our framework builds on the pipeline of [

10], equipping the ego agent with a modular interpreter conditioned on learnable prompts that adapt to the characteristics of each collaborator.

Our main contribution is integrating prompt-based interpretation with feature-level compression. Whereas prior prompt-guided approaches (e.g., PolyInter) assume access to full-resolution intermediate features, we depart from this assumption by applying codebook-based vector quantization at the sender, inspired by CodeFilling [

7]. Instead of transmitting high-dimensional floating-point feature maps, each agent emits compact discrete token maps produced by a learned codebook. This design drastically reduces the bandwidth while preserving the agent-specific cues required for downstream fusion. The ego agent then reconstructs and interprets these compressed features via a prompt-conditioned interpreter, enabling heterogeneous bandwidth-aware collaboration in a single framework.

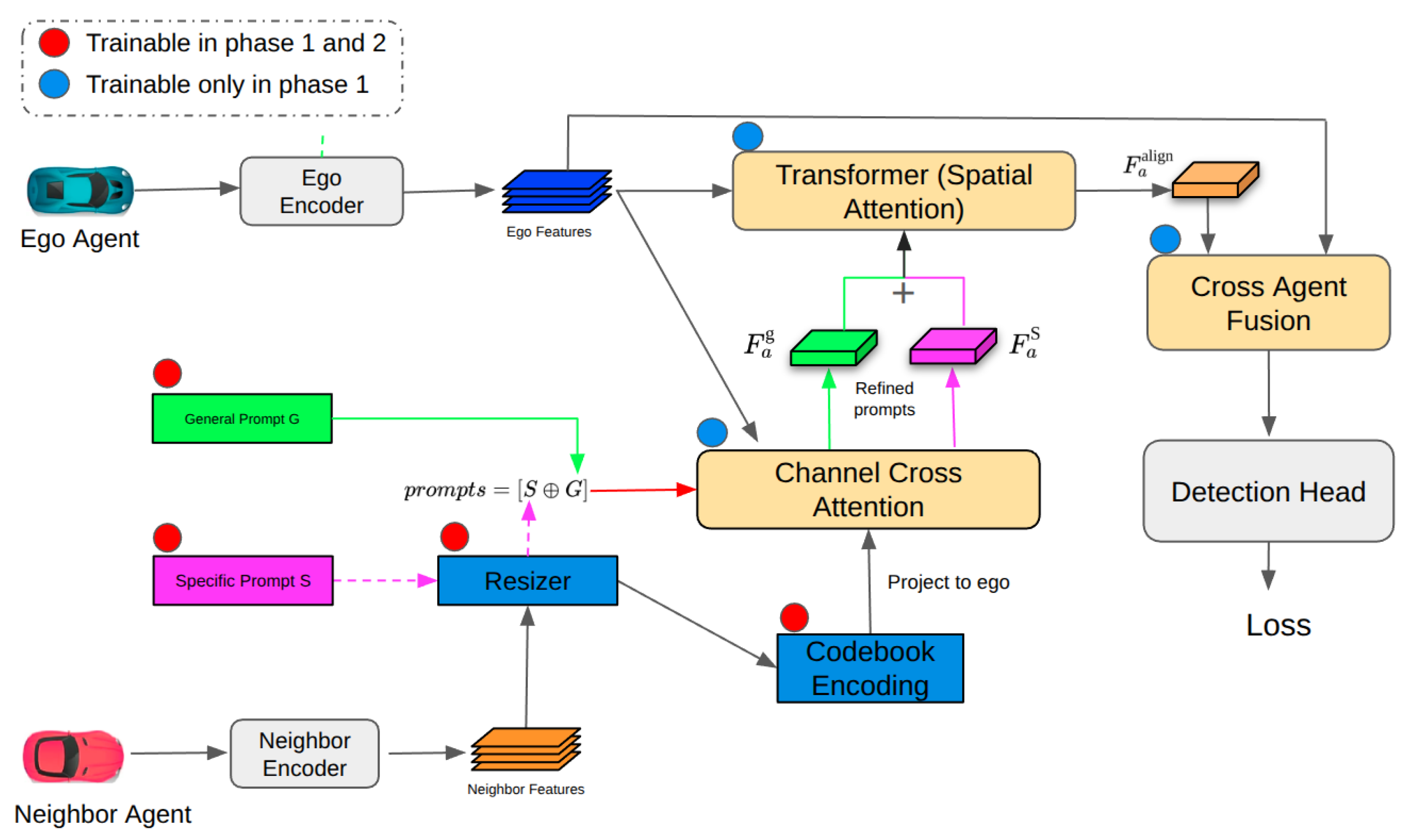

The proposed pipeline comprises four main stages: (1) local feature extraction with spatial resizers, (2) prompt-guided decoding and semantic alignment, (3) cross-agent feature fusion through ego-aligned representations, and (4) joint object detection. A two-phase training strategy is adopted, where Phase 1 jointly optimizes the interpreters, resizers, prompts, and fusion modules using a fixed agent set, while Phase 2 enables generalization to unseen agents by only fine-tuning agent-specific parameters. As illustrated in

Figure 1, each agent extracts local BEV features via its backbone encoder, after which neighbor features are spatially aligned and compressed using a learned codebook to reduce the communication bandwidth. Upon transmission to the ego vehicle, the features are decompressed and processed by a prompt-guided decoder, where both shared and agent-specific prompts facilitate the reinterpretation of heterogeneous feature distributions. Channel-wise correspondence is refined using cross attention, followed by spatial refinement via a lightweight transformer decoder, after which all processed features are fused and passed to a shared detection head for collaborative perception.

3.1. Feature Extraction, Resizer, and Codebook Compression

Each agent

employs a fixed perception backbone

tailored to its onboard sensors (e.g., LiDAR, monocular or multi-view cameras, or sensor fusion). Given observations

, the encoder produces an intermediate feature map:

where

,

, and

denote spatial dimensions and channels. Because encoders are not shared, the resulting feature spaces differ in semantic granularity and geometric encoding.

Before compression, a lightweight resizer, which interpolates spatial dimensions to

and projects channels to

C using a

convolution, is applied to unify feature shapes across agents:

To curb bandwidth consumption, we adopt a codebook-based compression module inspired by CodeFilling [

7]. Each agent learns a discrete codebook

, with

. For each spatial location

, the resized feature

is approximated by its nearest codeword:

This yields a compressed token map

, where each spatial entry corresponds to a codebook index, requiring only

bits per location.

To ensure semantic fidelity, the encoder

and the codebook

are trained with a vector-quantization objective:

where

is the stop-gradient operator, and

weights the commitment term, encouraging encoder outputs to remain close to the selected codewords.

Each agent transmits and an identifier for prompt retrieval (and, if needed, codebook metadata). These compact messages serve as inputs for downstream decoding, interpretation, and fusion at the ego side.

3.2. Prompt-Guided Decoding and Semantic Alignment

The ego reconstructs the quantized map

using the sender’s codebook:

To align heterogeneous features with the ego domain, we adopt a polymorphic interpreter network inspired by PolyInter [

10]. The interpreter performs spatial and channel alignment via (i) a resizer, (ii) channel selection, and (iii) spatial attention. Learnable prompts condition these modules to capture agent-specific variations.

3.2.1. Prompt Composition

Each agent a is associated with a learnable specific prompt , while a learnable general prompt encodes global priors common to all agents. Both prompts are trainable parameters that are optimized jointly during the training phase and subsequently shared across the fleet. These prompts are utilized throughout the pipeline, during both training and inference, to enable modularity and maintain cross-agent semantic consistency. In our implementation, all prompts are initialized using Xavier normal initialization and learned end-to-end together with the interpreter. The final prompt tensor is concatenated along the channel dimension and injected into the spatial attention module, enabling the ego vehicle to semantically align heterogeneous features received from its collaborators.

3.2.2. Channel Cross Attention

To align channels across encoders, we compute a similarity matrix

via scaled dot-product attention:

The neighbor features and prompts are reorganized as

where

denotes the layer normalization.

3.2.3. Prompt Injection

We form two branches:

captures shared semantics via

G, while

retains agent-specific semantics via

. Both are used downstream with designated objectives to encourage disentanglement.

3.2.4. Spatial Attention

Spatial relations between ego and neighbor features are aligned using a 3D fused axial attention mechanism [

14], yielding the final interpreted feature:

is semantically and geometrically consistent with the ego feature map and is passed to fusion for collaborative detection.

3.3. Cross-Agent Feature Fusion and Detection Head

The ego agent encodes its own input

via

to obtain

. After decoding and aligning neighbor features

, the ego fuses them with spatially varying attention:

where the attention weights are

and

is a lightweight scoring function (e.g., MLP or

conv). This allows fusion to weight agent contributions based on content-aware relevance. In experiments, we employ F-COOPER [

1] and CoBEVT [

14] as instantiations of the fusion mechanism.

The fused feature map

is passed to a detection head

:

which decodes bounding-box parameters (center, size, heading) and class probabilities. To preserve modularity, the detection head remains fixed during both training phases.

3.4. Training Procedure

To generalize across heterogeneous agents while maintaining communication efficiency, we adopt a two-phase training schedule that decouples core learning from agent-specific adaptation.

3.4.1. Phase 1: Base Model Training

Phase 1 trains a polymorphic interpreter to semantically align compressed features from multiple heterogeneous agents while disentangling shared versus agent-specific information. We train specific and general prompts, interpreter modules (resizer, Codebook, channel cross attention, spatial attention, and cross-agent fusion) on a fixed set of agent types. All encoders and the detection head remain frozen for modularity and generalization.

During training, each neighbor a provides a token map that is decoded, resized, and interpreted into two branches:

Specific branch, , for agent-specific semantics,

General branch, , for semantics shared across agents.

Losses are applied to encourage disentanglement:

Agent-Specific Loss (

): Single-agent detection

plus a style term aligning first and second moments with

:

Combined, we have

with weight

.

General Loss (

): To keep

domain-invariant, we adopt an adversarial objective following [

10]:

where

D predicts the domain origin (ego vs. neighbor), and

includes the channel cross attention and shared general prompt

G. A companion style term aligns distribution statistics with

:

yielding

Collaborative Detection Loss (

): The fused feature is scored by the frozen detector:

Compression (

): Encoder–codebook pairs are trained with the vector-quantization objective in Equation (

4) to preserve semantic fidelity.

The total Phase I loss is

with tunable weights

,

, and

.

3.4.2. Phase 2: Generalization and Deployment

After Phase I, the interpreter modules (the general prompt G, channel cross attention, spatial attention, cross-agent fusion) and detection head are frozen. This allows plug-and-play onboarding of new collaborators.

For a new agent a with an unseen encoder, we fine-tune only the agent-specific components:

The specific prompt (semantic adaptation),

The resizer (shape/channel alignment),

The codebook (discrete compression).

During operation, the new agent transmits its token map , identifier, and any required codebook metadata. The ego reconstructs features with the provided codebook and interprets them using the frozen interpreter plus . This supports rapid integration with minimal retraining and no changes to the main pipeline.

To preserve the semantic structure of the new agent, we reuse the Phase 1 agent-specific constraints (single-agent detection and style losses on

) and retain the collaborative detection objective for fused performance. The codebook

continues to be optimized with

. The Phase 2 loss is

where

and

balance the semantic adaptation and codebook fidelity.

At inference, the ego runs a single polymorphic interpreter with shared G and a bank of specific prompts for N agent types. In solo mode, the ego bypasses the interpreter. With collaboration enabled, each neighbor sends and an identifier, which selects the appropriate resizer and specific prompt for alignment before fusion.

3.5. Advantages and Flexibility

Our methodology delivers communication efficiency, modularity, and scalability. By decoupling compression from interpretation, the encoder, codebook, and resizer can be improved independently. Prompt-guided interpretation enables the ego to fuse features from heterogeneous agents without detailed knowledge of their models or retraining the core pipeline.

4. Experiment Settings

4.1. Datasets

We conduct our primary experiments on the OPV2V dataset [

15], a large-scale benchmark for evaluating collaborative perception in autonomous driving. OPV2V is built on the CARLA simulator [

16] and spans diverse driving scenarios (urban intersections, highways, curved roads). Each scenario involves multiple connected vehicles equipped with 64-beam LiDAR and synchronized GPS/IMU, capturing realistic challenges such as occlusion, viewpoint variation, and sensor noise. The dataset includes 319 scenes and more than 20,000 frames with precise 3D annotations for vehicles and other traffic participants, making it a strong testbed for both homogeneous and heterogeneous CP models.

We use OPV2VH+ [

17] to benchmark communication efficiency under heterogeneous sensing. OPV2VH+ extends OPV2V by introducing realistic variations in sensor configurations across agents. In contrast to the original OPV2V (which assumes identical LiDAR/camera setups), OPV2VH+ varies LiDAR types (e.g., 16-line, 32-line) and the number/placement of RGB/depth cameras across vehicles. This diversity stresses cross-agent sensor fusion, domain alignment, and generalization, providing a valuable benchmark for robust and adaptive collaborative detection.

4.2. Experiment Design

We adopt three commonly used LiDAR-based 3D object detection backbones, PointPillars [

18], VoxelNet [

19], and SECOND [

20], each instantiated with multiple configurations to emulate encoder heterogeneity. Following the training protocol in Polyinter [

10], the base model is trained in Phase 1 with two heterogeneous encoder groupings, denoted “ego-neb1-neb2”:

pp8-vn4-sd2 and

pp8-pp4-vn4. During Phase 1 training, the ego randomly samples one neighbor encoder per batch.

Table 1 summarizes the backbone configurations.

In Phase 2, we reuse the pretrained interpreter and fine-tune only the agent-specific components (specific prompt, resizer, and codebook) for each new collaborator: pp, sd, and vn. Collaborative detection is then evaluated in pairwise settings: pp8–pp4, pp8-sd1, and pp8-vn6. In each pair, the first entry denotes the ego agent, and the second denotes the newly added agent joining the fleet. Across all experiments, the neighbor encoders and the ego detection head remain frozen during training and evaluation. This setup reflects the immutable heterogeneity assumption and highlights the extensibility of our framework.

Following prior work [

9,

10,

21], we evaluate the 3D collaborative object detection within the BEV region

meters and

meters. Similar to PolyInter [

10], our experiments leverage the OPV2V benchmarks, where all collaborating agents share synchronized frames and globally registered BEV coordinates obtained from ground-truth ego poses. Consequently, the framework operates on geometrically aligned and temporally consistent feature maps, enabling the attention module to focus on semantic correspondence rather than geometric correction. In practical deployments, however, localization noise or latency may introduce residual misalignment among agents. Extending the spatial attention block with lightweight pose-refinement layers or temporal buffering mechanisms represents a promising direction for future work to enhance robustness under imperfect synchronization. Feature transmission is performed once per perception frame at the dataset’s native frequency (10 Hz for OPV2V and 8 Hz for OPV2VH+). The update rate remains fixed, with bandwidth reduction achieved solely through feature-level compression.

When pp8 serves as the ego, the general prompt is initialized to , , to match the ego’s feature shape. For each neighbor, the specific prompt’s channel dimension matches its native encoder, while the height and width are resized to align with the ego. Unless otherwise stated, the hyperparameters are , , and .

We report the bandwidth for both resized raw feature transmission and token-based communication. The bandwidth for sending floating-point features is estimated as

where

is the number of selected spatial regions,

C is the channel count, and 32 denotes

float32 precision. For vector-quantized communication with a codebook

of

codewords, assuming each token uses

codes, the required bandwidth is

where

is the number of bits per codeword index.

5. Results and Performance Comparison

We compared our method against three other methods, which are state of the art in extensible heterogeneous collaborative object detection: PolyInter [

10], PnPDA [

21], and MPDA [

9], using AP@0.5 and AP@0.7 as the evaluation metrics for reporting average precision. As shown in

Table 2, the experiments are conducted across three heterogeneous collaboration scenarios:

pp8-pp4,

pp8-sd1, and

pp8-vn6. We evaluate the performance under two widely adopted fusion modules: F-Cooper [

1] and CoBEVT [

14]. Our model was pretrained with two heterogeneous configurations (

pp8-vn4-sd2 and

pp8-pp4-vn4) and fine-tuned for each new neighbor in Phase 2 by updating only the specific prompt, resizer, and codebook compression. Across all three scenarios, our method achieves competitive or superior accuracy to the existing PnPDA and MPDA methods. In particular, under the CoBEVT fusion setting, our method consistently surpasses MPDA and PnPDA and achieves near-identical performance to PolyInter—despite using compressed token maps rather than full-resolution features. This validates our claim that prompt-guided interpretation combined with codebook-based compression can retain semantic fidelity even under tight bandwidth constraints.

From

Table 2, we observe that our model exhibits particularly strong generalization in high-heterogeneity settings such as

pp8-sd1 and

pp8-vn6. For example, under CoBEVT fusion, our method achieves an AP@0.5 score of 81.1%, closely matching PolyInter, while significantly outperforming MPDA and PnPDA. Due to data compression and information loss, the lower performance of our method compared to the Polyinter method was expected with the price of a lower communication volume between agents. Furthermore,

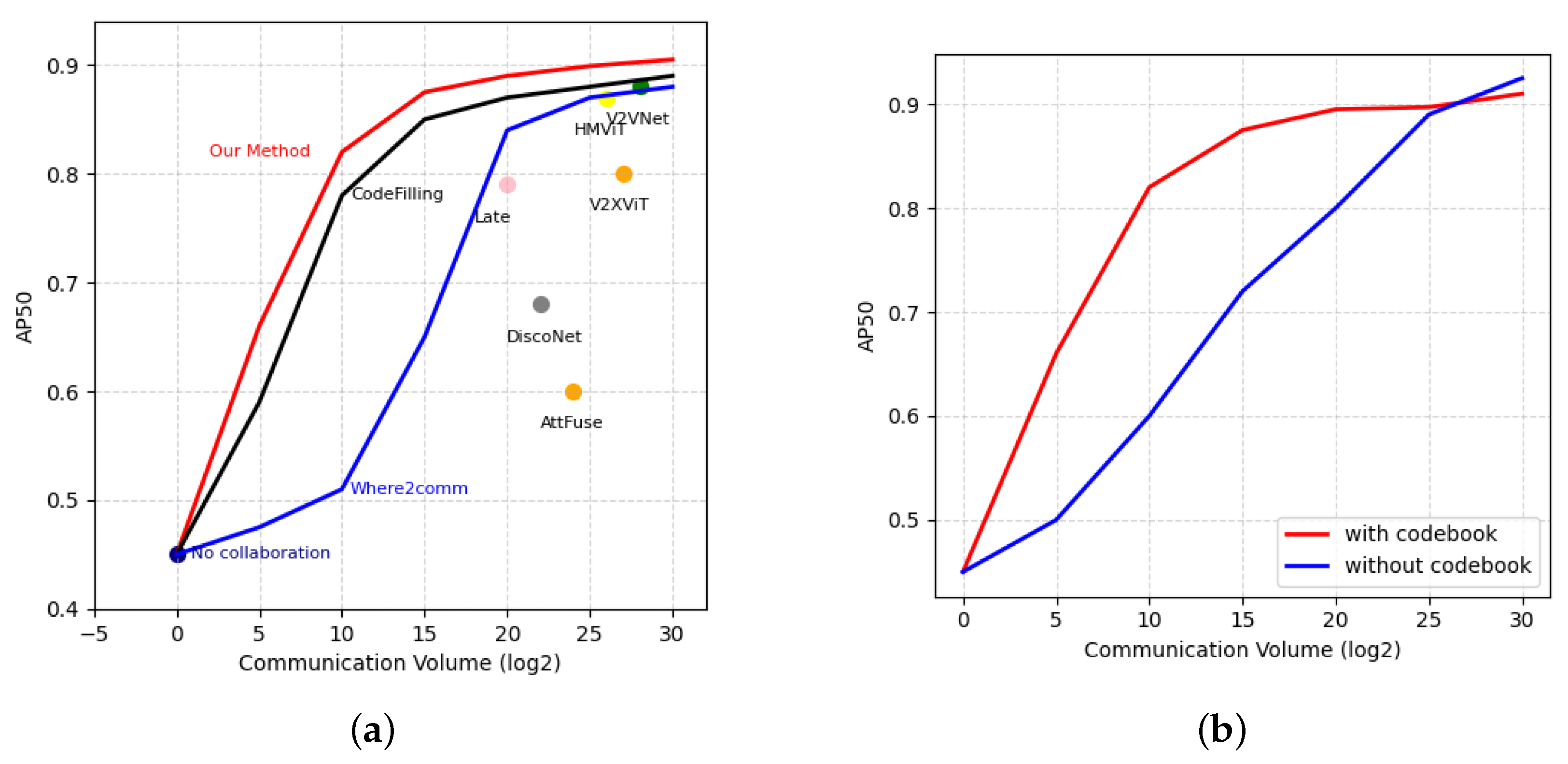

Figure 2a shows that our method tracks the performance of full-feature interpreters even at drastically lower bandwidths, outperforming Where2comm and Late Fusion by a large margin. These results highlighted our method’s unique ability to combine modular prompt-guided interpretation with communication-aware design, offering a practical and scalable solution for real world collaborative perception.

Figure 2b illustrates the perception–communication trade-off across heterogeneous agents on the OPV2V dataset. To further isolate the impact of compression, we compare variants of our framework with and without the codebook-based encoder in

Figure 2b. The non-compressed version effectively degenerates into a full-resolution PolyInter [

10] baseline, using simple alignment compression, whereas the codebook-based variant achieves nearly identical AP@50 performance while reducing the bandwidth consumption by up to 168×. These results demonstrate that our feature quantization introduces only negligible accuracy loss while dramatically improving the communication efficiency. Our framework consistently achieves higher detection accuracy across most bandwidth levels, except in the full-bandwidth regime, where all extracted features are transmitted. Compared with PolyInter [

10], using simple alignment compression, even under extremely limited communication (low log-bandwidth), our model maintains strong accuracy and robustness, outperforming all baselines while using significantly fewer transmitted bits.

The PolyInter framework [

10] has already analyzed the independent effects of general and specific prompts, confirming their roles in disentangling shared and agent-specific semantics. Based on that foundation, our study focuses on how to integrate the proposed codebook-based compression with PolyInter’s prompt-guided interpreter.

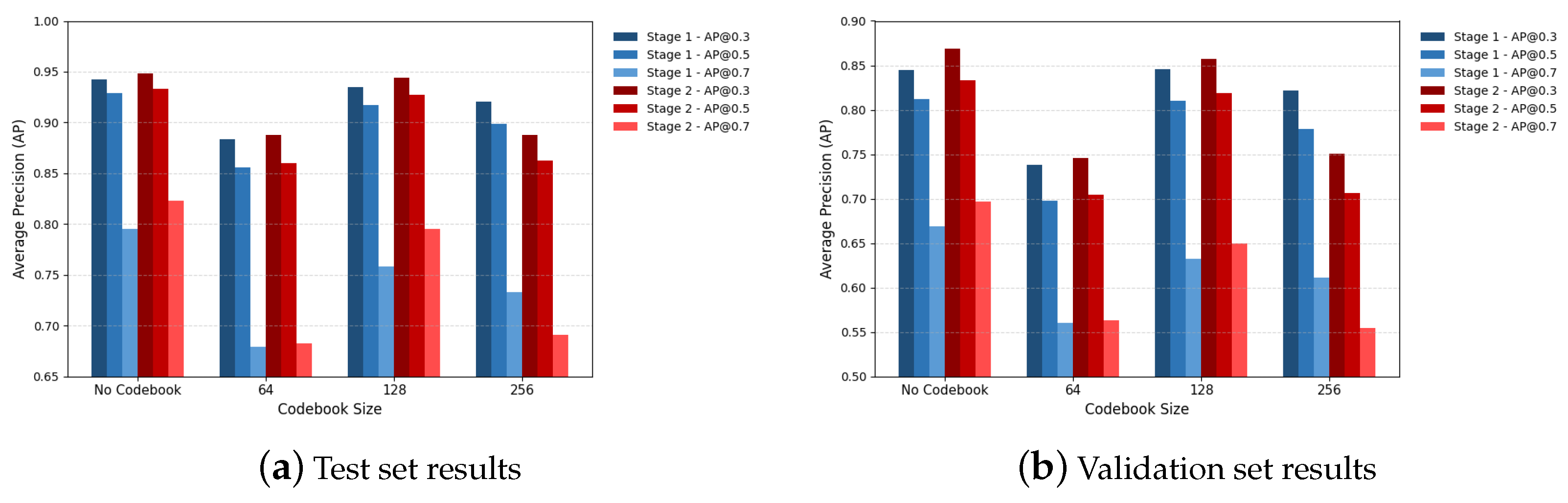

Figure 3 illustrates the performance of our pipeline without compression and with codebooks of sizes 64, 128, and 256 on the test and validation sets of the OPV2V dataset. The results show that the codebook behaves analogously to a clustering problem, where an intermediate size provides the best trade-off between compactness and fidelity. In our setup, a 128-entry codebook achieved the highest accuracy, while larger codebooks did not yield further improvement and sometimes slightly degraded the performance due to over-quantization noise and reduced utilization efficiency. These findings indicate that prompt-guided decoding effectively preserves semantic alignment even under discrete compression, and the two modules, prompts, and codebook encoding operate in a complementary manner to balance communication efficiency and perceptual accuracy.

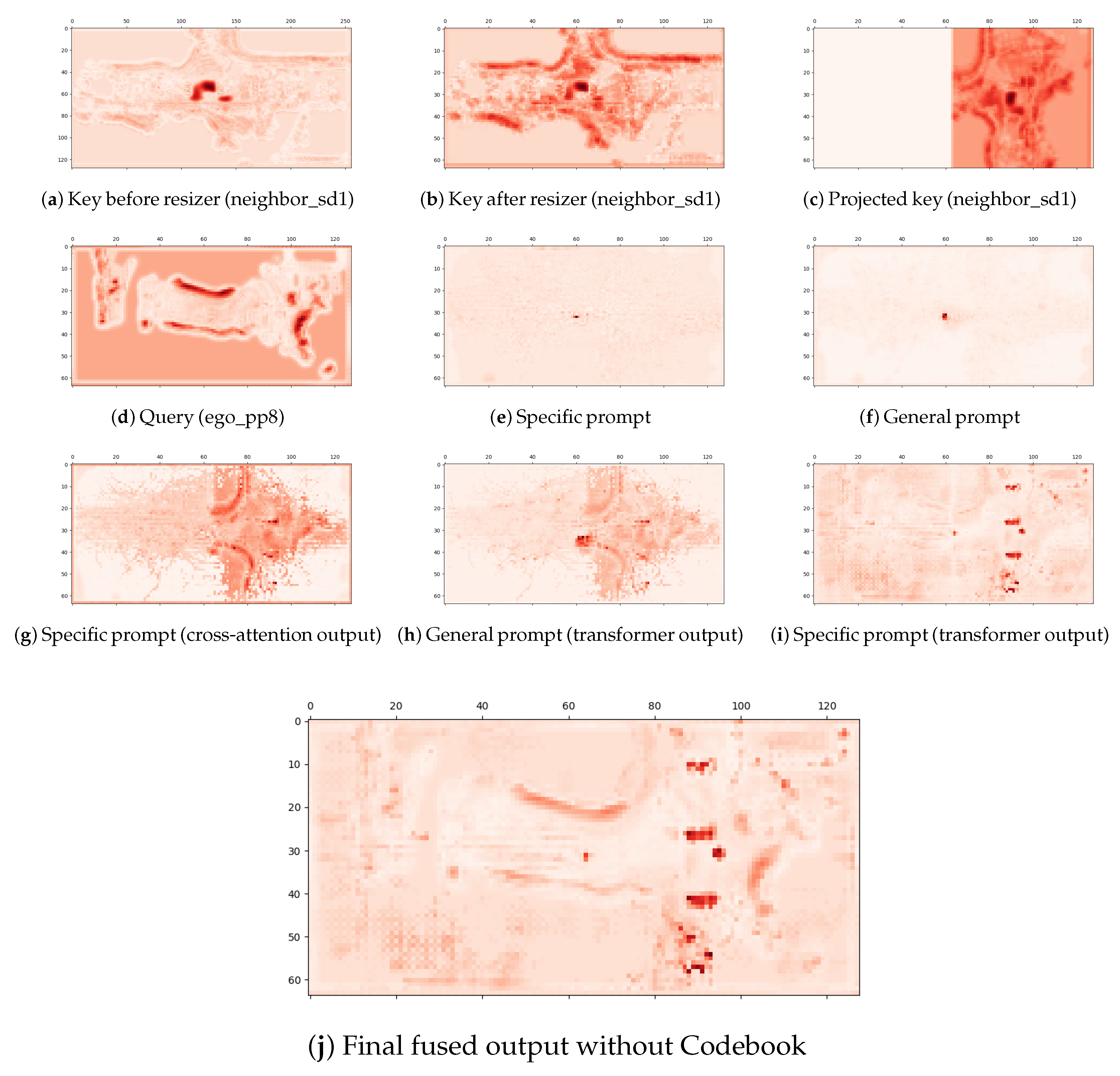

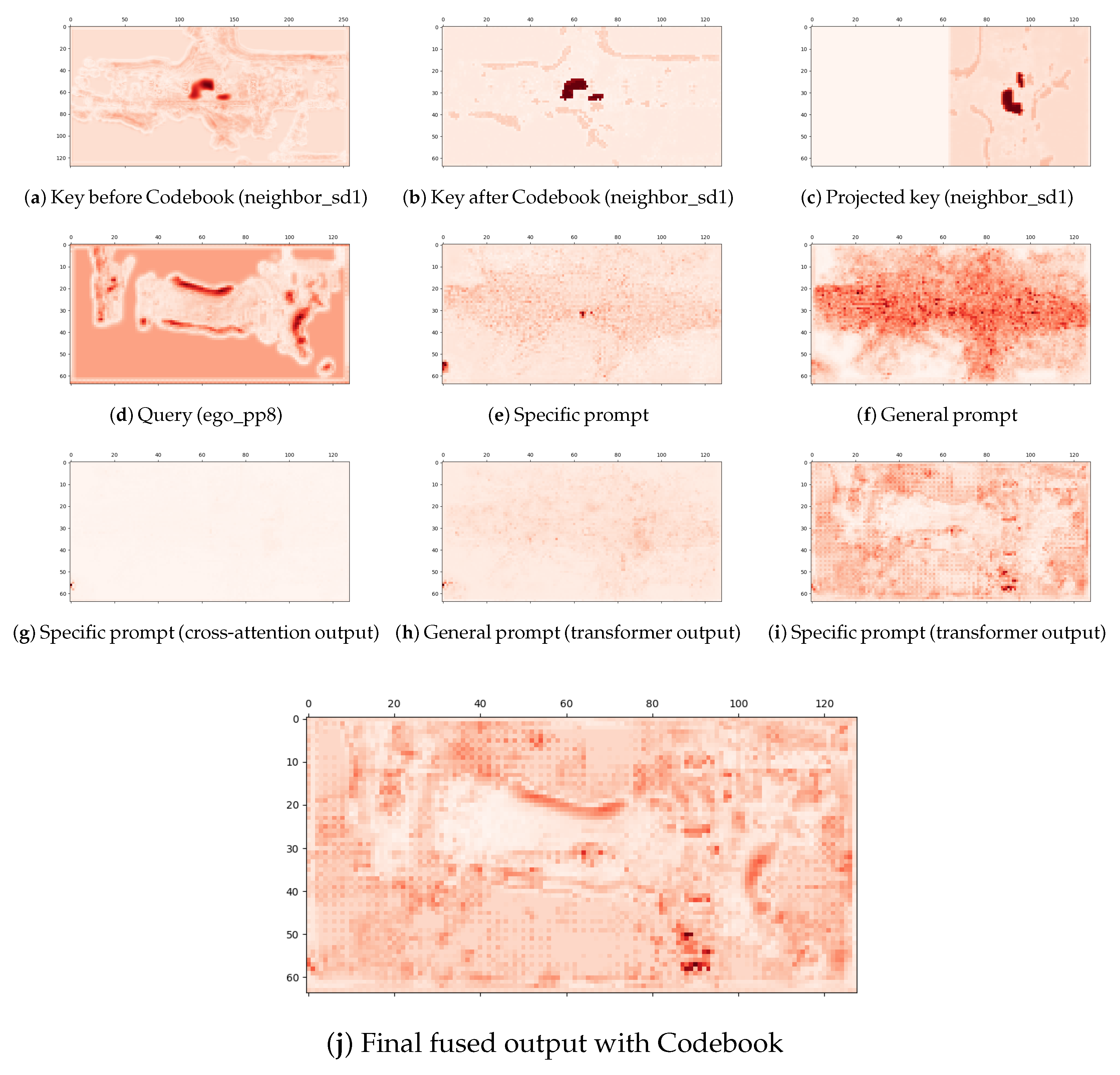

As visualized in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5, intermediate feature maps clarify the source of the detection loss after codebook compression. A portion of communication reduction is achieved by collapsing neighbor features along the channel dimension and reconstructing them at the ego side. This channel-space quantization inevitably leads to minor degradation of fine-grained or low-contrast details. After applying the cross-attention module (

Figure 4g and

Figure 5g), the specific prompt becomes suppressed because the compressed neighbor representation provides fewer distinct channel cues, reducing the ability of cross attention to establish one-to-one channel correspondence between the ego and neighbor features.

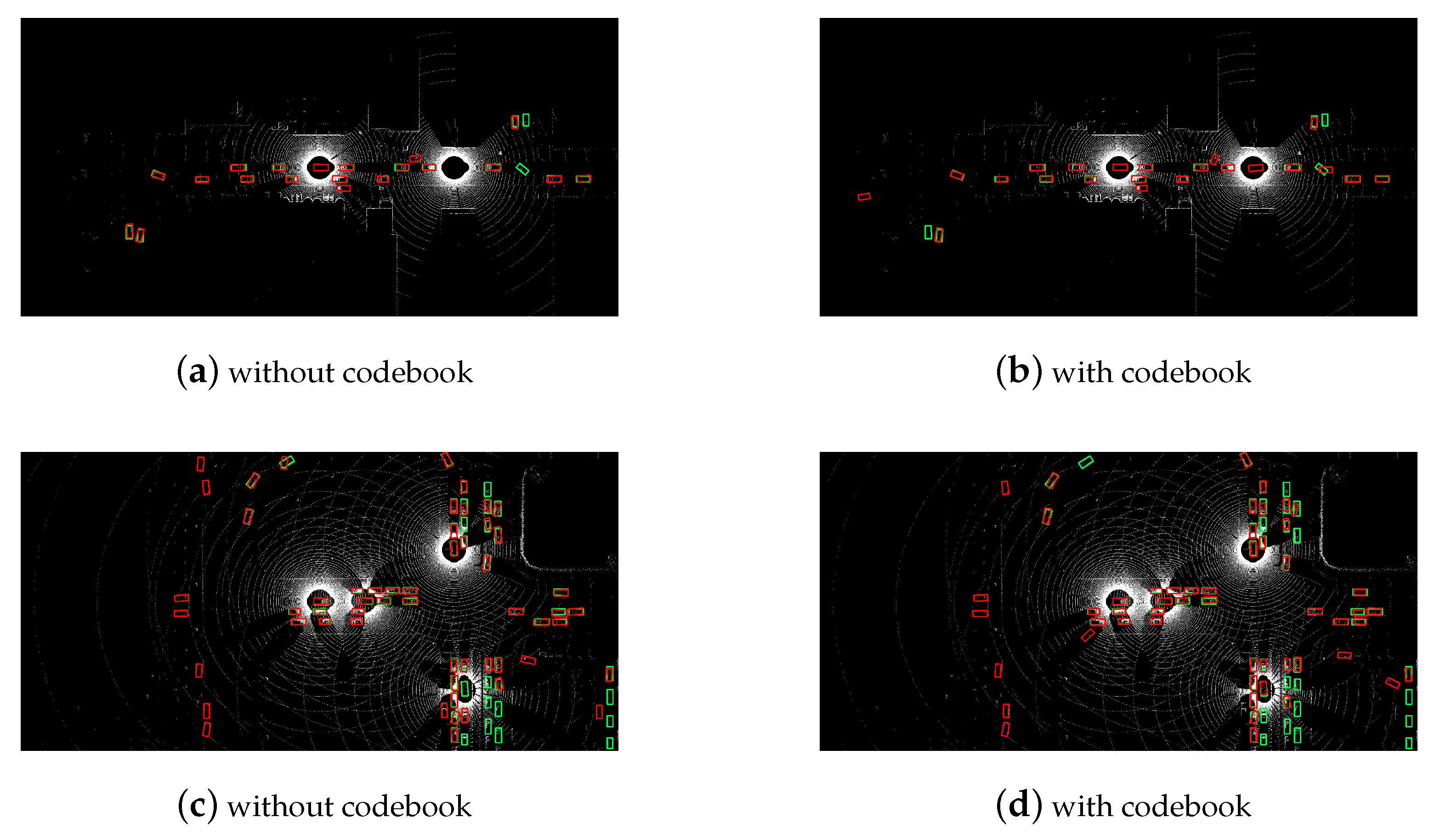

Figure 6 shows the final results of our proposed communication efficient immutable heterogeneous collaborative perception method on two input samples from OPV2V dataset. The red boxes are the detection results, and the green boxes are the ground truth.

6. Limitations and Conclusions

The current implementation employs a fixed learned codebook to ensure compact and consistent communication; however, the framework naturally supports adaptation to varying perceptual conditions. Although codebook-based compression is effective in reducing bandwidth, its static update mechanism does not fully account for environmental variability such as illumination changes, adverse weather, or fluctuating traffic density. In future work, lightweight extensions will be explored to enable context-aware codebook selection or interpolation among a small set of domain-specific codebooks, thereby improving the robustness under dynamic conditions. Additionally, the optimal codebook size, determined empirically as 128 in our experiments, remains a trade-off between representational fidelity and word-level compression limits. This selection currently requires multiple rounds of training, which introduces computational overhead. To further enhance the communication efficiency, spatial reduction mechanisms (e.g., selective feature masking or threshold-based pruning) may also be incorporated as complementary strategies to codebook compression. To better exploit modality-specific reliability, the attention weights can be conditioned on real-time sensor confidence metrics (e.g., illumination quality for cameras or point density for LiDAR). In our implementation, the scoring function may incorporate such reliability factors to adaptively emphasize more trustworthy sources. This modular formulation enables easy integration of a reliability estimation head in future deployments.

In this research, we introduced a unified framework for communication-efficient and extensible collaborative perception in heterogeneous autonomous driving environments. By integrating prompt-guided interpretation with codebook-based compression, our method addresses the dual challenges of bandwidth constraints and architectural diversity, which remain central bottlenecks in real-world multi-agent systems.

Unlike previous approaches that handle either heterogeneity or communication in isolation, our framework bridges both challenges through a modular and scalable design. Each agent compresses its feature maps into compact token representations using learned vector-quantized codebooks, significantly reducing the transmission overhead. On the ego side, a polymorphic interpreter decodes and semantically aligns these compressed features using a combination of shared and agent-specific prompts, resizers, and attention-based fusion modules.

Our two-phase training strategy further enhances system flexibility: Phase 1 learns a generalizable interpreter across fixed agent types, while Phase 2 adapts lightweight components, i.e., specific prompts, resizer, and codebooks for new agents, preserving the frozen core model. This design ensures plug-and-play extensibility without retraining or compromising detection accuracy. Extensive experiments on the OPV2V and OPV2VH+ benchmarks demonstrate that our method achieves competitive detection accuracy while reducing the communication volume by over two orders of magnitude. Despite quantization, our model maintains strong performance in various fusion strategies and heterogeneous scenarios, validating the effectiveness of prompt-guided decoding and codebook compression.

Together, these contributions lay the foundation for scalable, bandwidth-aware, and generalizable collaborative perception in diverse and dynamic autonomous driving ecosystems.

Author Contributions

Methodology and writing original draft preparation, B.E.S.; review and editing, A.R. and Y.P.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Science Foundation under grant number CNS-1932037, and the article processing charges were provided in part by the UCF College of Graduate Studies Open Access Publishing Fund.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study did not require ethical approval as it did not involve any humans or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

The study did not require ethical approval, as it did not involve any humans or animals.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chen, Q.; Ma, X.; Tang, S.; Guo, J.; Yang, Q.; Fu, S. F-Cooper: Feature based cooperative perception for autonomous vehicle edge computing system using 3D point clouds. In Proceedings of the 4th ACM/IEEE Symposium on Edge Computing, Washington, DC, USA, 7–9 November 2019; pp. 88–100. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, R.; Xia, X.; Li, J.; Li, H.; Zhang, S.; Tu, Z.; Meng, Z.; Xiang, H.; Dong, X.; Song, R.; et al. V2v4real: A real-world large-scale dataset for vehicle-to-vehicle cooperative perception. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BA, Canada, 18–22 June 2023; pp. 13712–13722. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.C.; Tian, J.; Glaser, N.; Kira, Z. When2com: Multi-agent perception via communication graph grouping. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020; pp. 4105–4114. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Zhou, T. CoRE: Cooperative reconstruction for multi-agent perception. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 1–6 October 2023; pp. 8710–8720. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.; Hu, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Wang, D.; Wang, Y.; Chen, S. An extensible framework for open heterogeneous collaborative perception. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.13964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Fang, S.; Lei, Z.; Zhong, Y.; Chen, S. Where2comm: Communication-efficient collaborative perception via spatial confidence maps. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2209.12836. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.; Peng, J.; Liu, S.; Ge, J.; Liu, S.; Chen, S. Communication-efficient collaborative perception via information filling with codebook. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 15481–15490. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, R.; Xiang, H.; Tu, Z.; Xia, X.; Yang, M.H.; Ma, J. V2X-ViT: Vehicle-to-everything cooperative perception with vision transformer. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 107–124. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, R.; Li, J.; Dong, X.; Yu, H.; Ma, J. Bridging the domain gap for multi-agent perception. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, London, UK, 29 May–2 June 2023; pp. 6035–6042. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, Y.; Yuan, Q.; Luo, G.; Fu, X.; Li, Y.; Zhu, X.; Luo, T.; Chen, S.; Li, J. One is Plenty: A Polymorphic Feature Interpreter for Immutable Heterogeneous Collaborative Perception. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Conference, Nashville, TN, USA, 11–15 June 2025; pp. 1592–1601. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, L.; Zhao, J.; Wiedholz, A.; Bied, M.; de Lucena, M.M.; Jagtap, A.D.; Festag, A.; Fröhlich, A.A.; Keen, H.E.; Vinel, A. Systematic literature review on vehicular collaborative perception–a computer vision perspective. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.04631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.H.; Manivasagam, S.; Liang, M.; Yang, B.; Zeng, W.; Urtasun, R. V2vnet: Vehicle-to-vehicle communication for joint perception and prediction. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; Proceedings, Part II 16. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 605–621. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, G.; Zhang, H.; Yuan, Q.; Li, J. Complementarity-enhanced and redundancy-minimized collaboration network for multi-agent perception. In Proceedings of the 30th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Lisboa, Portugal, 10–14 October 2022; pp. 3578–3586. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, R.; Tu, Z.; Xiang, H.; Shao, W.; Zhou, B.; Ma, J. CoBEVT: Cooperative bird’s eye view semantic segmentation with sparse transformers. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2207.02202. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, R.; Xiang, H.; Xia, X.; Han, X.; Li, J.; Ma, J. Opv2v: An open benchmark dataset and fusion pipeline for perception with vehicle-to-vehicle communication. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Philadelphia, PA, USA, 23–27 May 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 2583–2589. [Google Scholar]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Ros, G.; Codevilla, F.; Lopez, A.; Koltun, V. CARLA: An open urban driving simulator. In Proceedings of the Conference on Robot Learning, Mountain View, CA, USA, 13–15 November 2017; PMLR. pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.; Lu, Y.; Xu, R.; Xie, W.; Chen, S.; Wang, Y. Collaboration helps camera overtake lidar in 3d detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 9243–9252. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, A.H.; Vora, S.; Caesar, H.; Zhou, L.; Yang, J.; Beijbom, O. PointPillars: Fast encoders for object detection from point clouds. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 12697–12705. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Tuzel, O. VoxelNet: End-to-end learning for point cloud based 3D object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 4490–4499. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Y.; Mao, Y.; Li, B. SECOND: Sparsely embedded convolutional detection. Sensors 2018, 18, 3337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, T.; Yuan, Q.; Luo, G.; Xia, Y.; Yang, Y.; Li, J. Plug and Play: A representation enhanced domain adapter for collaborative perception. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Porto, Portugal, 14–17 July 2025; pp. 287–303. [Google Scholar]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).