Abstract

Pathogens causing candidiasis encompass a diverse group of ascomycetous yeasts that have become essential models for studying fungal adaptability, pathogenicity, and host–pathogen interactions. Although many candidiasis-promoting species exist as commensals within host microbiota, several have acquired virulence traits that enable opportunistic infections, positioning them as a leading cause of invasive fungal disease in humans. Deciphering the molecular and genetic determinants that underpin the biology of organisms responsible for candidiasis has long been a central objective in medical and molecular mycology. However, research progress has been constrained by intrinsic biological challenges, including noncanonical codon usage and the absence of a complete sexual cycle in diploid species, which have complicated traditional genetic manipulation. CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing has overcome many of these limitations, providing a precise, efficient, and versatile framework for targeted genomic modification. This system has facilitated functional genomic studies ranging from single-gene deletions to high-throughput mutagenesis, yielding new insights into the mechanisms governing virulence, antifungal resistance, and stress adaptation. Since its initial application in Candida albicans, CRISPR-Cas9 technology has been refined and adapted for other clinically and industrially relevant species, including Nakaseomyces glabratus (formerly referred to as Candida glabrata), Candida parapsilosis, and Candida auris. The present work provides an overview of the evolution of genetic approaches employed in research directed against candidiasis-associated species, with a particular focus on the development and optimization of CRISPR-based systems. It highlights how recent advancements have improved the genetic tractability of these pathogens and outlines emerging opportunities for both fundamental and applied studies in fungal biology.

1. Introduction

Candidiasis-associated species comprise a group of ascomycetous yeasts widely distributed in both environmental and human-associated microbiota, many of which reproduce asexually by budding and may undergo morphological transitions that contribute to virulence [1,2]. While over 400 species have been described, only a subset are prominent human opportunistic pathogens. For instance, candidiasis infections caused by Candida albicans and increasingly also by pathogens commonly known as non-albicans Candida (NAC) species, pose major global medical challenges [3,4]. Of note, although Nakaseomyces glabratus (formerly classified as Candida glabrata) is no longer classified within the genus Candida due to significant genetic divergence [5,6], it remains a causative agent of candidiasis. These organisms can lead to bloodstream infections (called candidemia) or other forms of invasive candidiasis. On a worldwide scale, invasive candidiasis is estimated to affect around 1.56 million people each year, with nearly one million deaths reported, yielding a crude mortality rate of approximately 64% [7]. For candidemia specifically, large cohort studies have found 90-day all-cause mortality rates around 42% in many settings, with attributable mortality of approx. 28% [8]. Although C. albicans remains the most frequently isolated species in many regions, a steady shift toward NACs is evident worldwide [9].

The medical implications of this epidemiological picture are substantial. High mortality is compounded by frequent delays in diagnosis, limited antifungal penetration in certain sites, the presence of biofilms on medical devices, and the rise in antifungal resistance, especially among NACs. Additionally, healthcare-associated burden, substantial cost, and the increasing prevalence of at-risk populations, including the elderly, amplify the global health threat. The convergence of high incidence, high mortality, limited therapeutic options and evolving species distribution stresses the urgent need for improved surveillance, rapid diagnostics, and novel antifungals [10].

Despite substantial progress in sequencing and comparative genomics, our understanding of the genetic architecture underlying pathogenicity, stress tolerance, and antifungal resistance in species responsible for candidiasis remains remarkably limited. The majority of available data derive from C. albicans, leaving many NACs only partially characterized at the functional genomic level [11]. Moreover, key biological features of candidiasis-associated yeasts, such as their diploid or aneuploid genomes and parasexual reproduction, pose major obstacles to classical genetic manipulation and mutagenesis approaches [12]. This also includes the noncanonical translation of the CUG codon (translated as serine instead of leucine) in so-called CTG-clade species like C. albicans, C. auris, Candida dubliniensis, C. lusitaniae, Candida parapsilosis or Candida tropicalis. As a result, only a fraction of genes predicted to influence antifungal resistance or host interaction have been experimentally validated, and even basic genotype–phenotype relationships remain elusive for most species [11]. This lack of functional genetic knowledge directly limits our capacity to design new therapeutic strategies or diagnostic tools. To bridge this gap, there is an urgent need to expand the toolkit for precise genetic modification across candidiasis-associated yeast species.

In recent years, the advent of genome editing based on the clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) technology has opened new possibilities for functional genetics in candidiasis-associated yeast species, offering unprecedented precision and efficiency compared to earlier approaches such as the URA Blaster, URA Flipper, Cre-loxP, and UAU1 cassette systems. Early advances in C. albicans genetics led to the development of the URA Blaster, which employed the URA3 gene flanked by hisG sequences from Salmonella enterica Typhimurium to facilitate sequential allele deletions through spontaneous recombination [13,14]. Although powerful for generating homozygous deletions in diploid C. albicans, its low recombination frequency and the residual hisG sequences left at target loci could interfere with adjacent gene expression or promote unwanted recombination events [15]. To address these limitations, the URA Flipper system was developed, integrating the site-directed FLP/FRT recombination system under an inducible SAP2 promoter. This system is based on the recombination of sequences between short flippase recognition target (FRT) sites by the recombinase flippase (FLP), thus enabling efficient marker excision and leaving behind only a minimal FRT scar [16]. Similarly, the Cre-loxP system allowed for simultaneous targeting of both alleles using loxP-flanked markers and an inducible Cre recombinase, although it remained limited by multiple transformation steps and the requirement for triple auxotrophic strains [17]. The UAU1 cassette, a modified URA Blaster construct containing an ARG4 marker within URA3 repeats, further streamlined homozygous deletions by allowing simultaneous selection of both alleles [18]. In later developments, drug resistance markers such as SAT1 and CaNAT1 replaced auxotrophic markers, enabling genetic manipulation of clinical isolates [19,20,21].

These traditional methods have been instrumental in advancing our understanding of candidiasis-promoting pathogens. They laid essential foundations for dissecting gene function and understanding fundamental aspects of fungal biology and virulence. Importantly, these approaches remain highly relevant today. For instance, large-scale mutant collections, generated with classic genome-engineering strategies, provide powerful tools for functional genomics screens aimed at identifying genes required for key biological processes such as morphogenesis and filamentation and determinants of fungal viability [22,23]. A major functional genomics platform developed for C. albicans is the Gene Replacement and Conditional Expression (GRACE) library, which is composed of heterozygous gene disruption strains in which transcription of the remaining intact allele is placed under the control of a doxycycline-inducible repressible promoter system [22]. Initially, the library encompassed engineered strains corresponding to 2326 distinct loci in C. albicans and is constantly being expanded [22]. However, the traditional methods used to create those libraries are often labor-intensive, time-consuming, and limited in scope. For instance, they require multiple transformations, rely on auxotrophic backgrounds, and are inefficient for large-scale or multi-gene deletions, which constrains their use, e.g., in NACs and clinical isolates [24]. CRISPR technology has the potential to overcome many of these challenges by enabling rapid and targeted genetic manipulation, thereby accelerating the dissection of cellular processes and the identification of novel therapeutic targets. While CRISPR applications in the Candida genus and related species have been reviewed previously [12], the field is evolving rapidly, with novel and complementary methodologies continually emerging. This minireview focuses on the development of current applications of CRISPR in causative agents of candidiasis, emphasizing how this toolkit is reshaping genetic engineering in these complex fungal pathogens.

2. CRISPR-Cas Technology

The CRISPR-Cas (CRISPR-associated) system is a naturally occurring adaptive immune mechanism in bacteria and archaea, where CRISPR-derived RNAs (crRNAs) convey the silencing of invading nucleic acids from viruses and plasmids [25,26]. In brief, the CRISPR locus functions as a molecular memory bank, where short fragments of foreign DNA, known as spacers, are integrated into the host genome between repetitive sequences following infection [27]. Upon subsequent exposure, these spacers are transcribed and processed into crRNAs that guide Cas endonucleases to complementary sequences in invading genetic material, facilitating targeted degradation [27]. This adaptive process allows bacteria to mount sequence-specific immunity against recurrent infections and provides heritable resistance to phage attack [27]. In 2012, the Charpentier and Doudna labs presented a repurposed version of this system to enable targeted genome editing by directing it to specific genetic loci for modification [25] (Figure 1). The engineered system depends on two primary components reminiscent of the natural mechanism: the Cas endonuclease protein and a synthetic guide RNA (sgRNA). The sgRNA binds and steers the Cas enzyme to the desired genetic location, where the enzyme induces a double-stranded break (DSB) in the genome [28]. To fulfill its dual function of guiding the Cas enzyme to the target genomic locus and facilitating enzyme binding, the sgRNA is composed of two key components: the crRNA, which directs specificity through complementary base pairing with the target DNA sequence, and the trans-activating CRISPR RNA (tracrRNA), which is essential for Cas enzyme binding and the formation of an active complex [29]. A successful targeting event also depends on the presence of a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM), a short, conserved DNA sequence adjacent to the target site. The PAM ensures that the CRISPR machinery differentiates between the target and the sgRNA sequence [30].

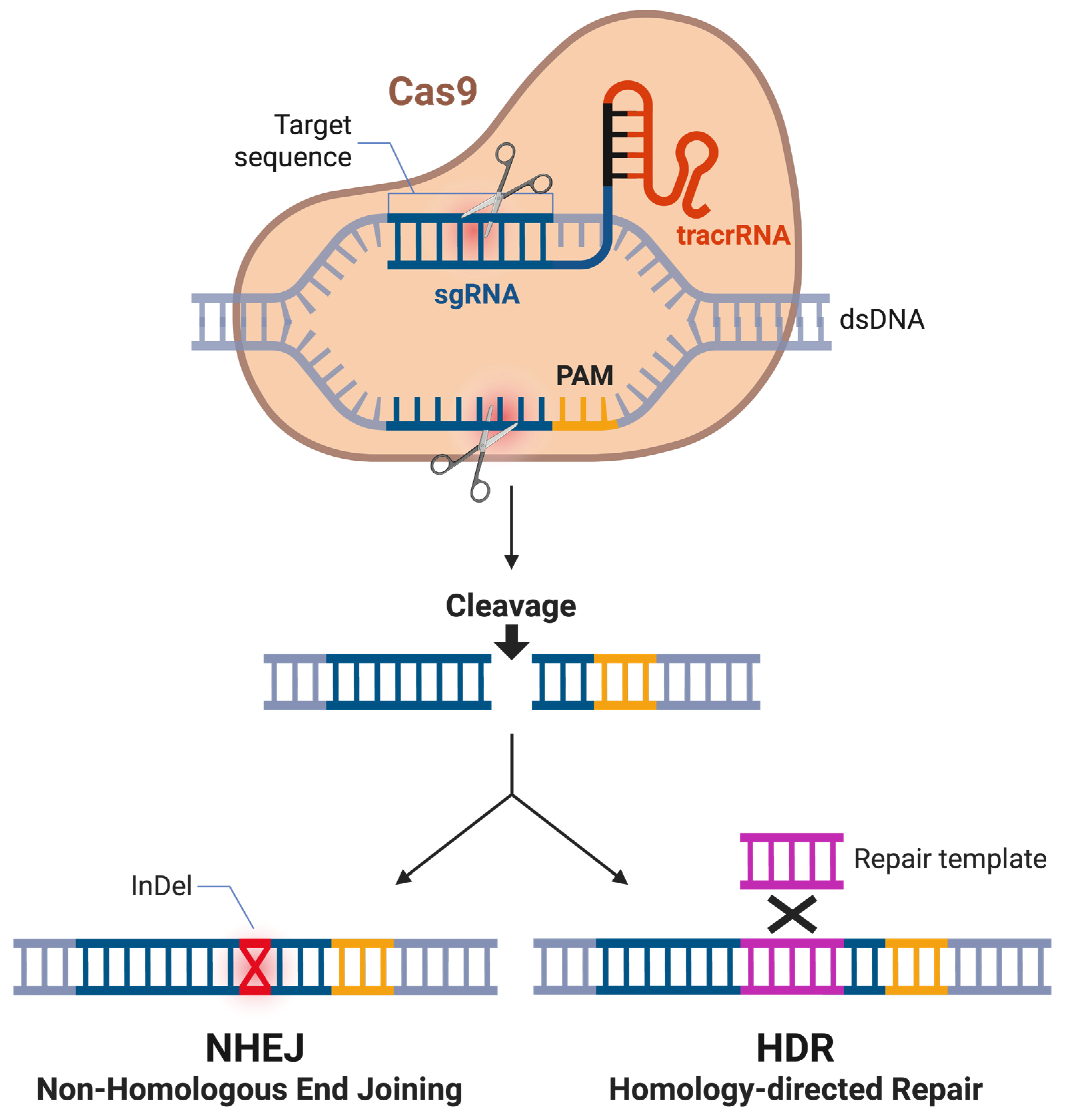

Figure 1.

Schematic overview of CRISPR-Cas9-mediated genome editing. Cas9 introduces a site-specific double-strand break in the target DNA. In the absence of an exogenous repair template, the break is predominantly repaired by non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), frequently resulting in insertions or deletions (InDels) that can disrupt gene function. In the presence of a homologous repair template, the break can be repaired through homology-directed repair (HDR), enabling the precise introduction of defined genetic modifications. Figure created in BioRender BETA. Odabas, M. (2026) https://BioRender.com/k6d4x83 (accessed on 26 January 2026).

After the targeted introduction of a DSB, CRISPR-mediated genome editing leverages the cell’s natural genomic repair pathways to introduce changes at the DSB site. The two predominant repair mechanisms are homology-directed repair (HDR) and non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) [31]. HDR uses a homologous DNA template to accurately repair the break and incorporate new sequences [31]. This DNA template can be specifically engineered and introduced externally. In contrast, NHEJ reconnects the broken ends without a template, often resulting in insertions or deletions (indels) at the repair site [32]. In recent years, CRISPR-Cas9 has dramatically advanced genetic engineering, revolutionizing editing of prokaryotic and especially eukaryotic genomes—including those of various Candida and related species—where prior tools had substantial limitations [33,34,35].

3. CRISPR in Candida albicans

3.1. Approaches to DNA Editing and Control

The initial deployment of CRISPR-based genome editing within the Candida genus was pioneered in Candida albicans, the most thoroughly characterized species. In 2015 [36], the reconfiguration of a CRISPR-Cas was reported for functional use in C. albicans (Figure 2, Table 1). Implementing this technology in C. albicans necessitated addressing several organism-specific barriers. Notably, some Candida spp. or related species translate the CUG codon as serine instead of leucine. As a result, the Cas9 coding sequence required extensive recoding to ensure correct protein synthesis. Moreover, due to the organism’s inability to support autonomously replicating plasmids, the system was built for stable chromosomal integration. For sgRNA transcription, the native RNA polymerase III promoter pSNR52 was employed. Two distinct strategies were established for CRISPR component delivery: a single plasmid co-expressing Cas9 and sgRNA, and a dual-plasmid configuration in which each component was encoded separately. In both approaches, precise gene modifications were achieved by co-delivering an HDR template, typically introducing a frameshift mutation that resulted in premature translational termination. Subsequent genomic analysis revealed that this CRISPR platform enables targeting of more than 98% of C. albicans genes, greatly enhancing the capacity for rapid functional genetic studies [36].

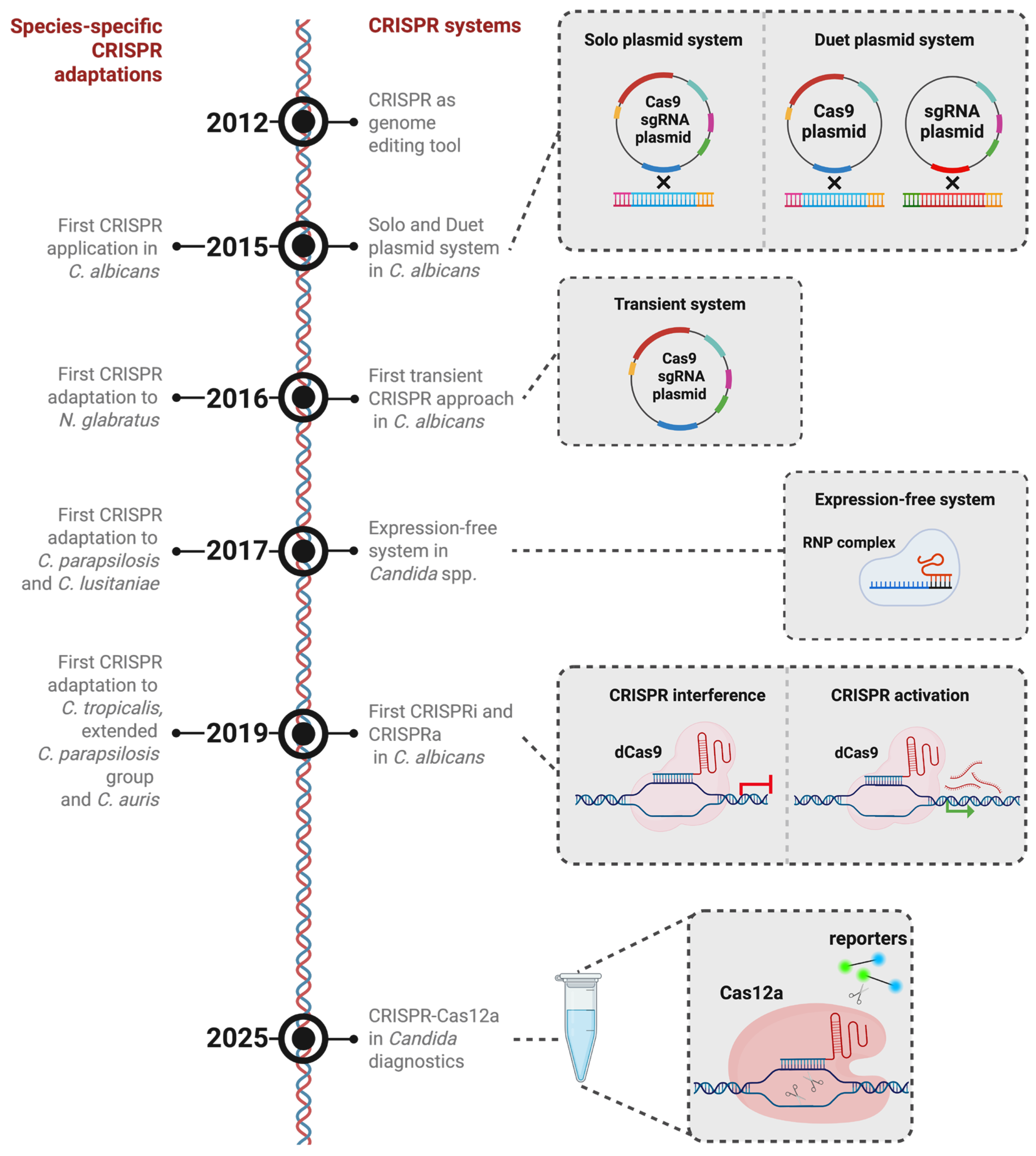

Figure 2.

Timeline of CRISPR-based gene-editing innovations in candidiasis-associated species. CRISPR-based gene editing was first reported in 2012. (2015) Initial CRISPR-based strategies in C. albicans employed a dual-plasmid configuration, in which the CAS9 expression cassette and the sgRNA cassette were maintained on separate plasmids and integrated into the genome. This was followed by a single-plasmid system that unified both components into one construct. (2016) Subsequently, transient episomal plasmids were introduced as a non-integrative alternative. (2017) To minimize species-dependent differences in expression systems, an expression-independent approach using preassembled Cas9-sgRNA ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes was later adopted. (2019) The implementation of CRISPRi and CRISPRa expanded the toolkit to enable targeted transcriptional repression and activation, facilitating epigenetic modulation. (2025) Most recently, CRISPR-Cas12a has been adapted for diagnostic purposes in C. albicans. Parallel to these developments, species-specific CRISPR platforms have been engineered to support efficient, cost-effective genome editing across diverse candidiasis-associated yeast species. The components of the CRISPR plasmids are indicated as follows: dark red—Cas9; yellow—Cas9 promoter; cyan—NAT resistance marker; green—sgRNA; magenta—SNR53 promoter; blue—ENO1; bright red (sgRNA plasmid)—RP10. Figure created in BioRender BETA. Odabas, M. (2026) https://BioRender.com/k6d4x83 (accessed on 26 January 2026).

However, due to concerns about off-target effects that could result from continuous CRISPR activity, which was designed to remain in the genome, a transient approach was developed to express the system without genome integration (Figure 2) [37,38]. This approach leverages the fact that Cas9/sgRNA-mediated genome editing does not necessitate genomic integration of the expression elements [37]. By restricting Cas9/sgRNA expression to a limited timeframe, this method simplifies the editing process and reduces off-target risks [37]. Moreover, it facilitates simultaneous editing by enabling the delivery of multiple distinct sgRNA constructs into a single cell, allowing for multi-locus targeting [37]. However, despite their considerable efficacy, transient CRISPR-Cas9 approaches are subject to certain constraints. In various model systems, CRISPR-Cas9-based functional genomics screens frequently depend on the formation of small indels through NHEJ to inactivate target genes [39]. Furthermore, transient expression of Cas9 and its associated sgRNAs is currently incompatible with NHEJ-dependent methods, as the expression cassettes are rapidly degraded or become diluted during cell proliferation [37]. Notwithstanding these limitations, the transient CRISPR approach is particularly advantageous for engineering C. albicans mutants without leaving selectable markers behind. The scarcity of dominant selectable markers for this species, coupled with the observation that certain markers can influence pathogenicity, makes marker recycling a necessity to study C. albicans. For instance, the URA3 gene, which has been frequently employed as a selection marker in C. albicans, critically influences virulence. Consequently, the attenuated virulence observed in strains generated using the ura-blaster cassette cannot be conclusively attributed to the intended gene disruption [14]. Integrating marker excision strategies with CRISPR tools allows for multiple rounds of genome editing in the same background without compromising virulence traits. One such strategy, CRISPR-mediated marker excision (CRIME), induces a DSB within the selectable marker to trigger recombination between flanking direct repeats, leading to the marker’s excision from the genome [38,40]. Further developments, including methods like LEUpOUT and HIS-FLP, have enabled efficient marker-recyclable, homozygous editing in C. albicans, while simultaneously allowing for both marker and CRISPR element removal [41]. Using these approaches, entire gene families can be systematically deleted, enabling the characterization of functional differences among individual family members and their collective roles in cellular processes. For instance, deletion of the TLO gene family by CRISPR-Cas9 revealed substantial functional diversity, with distinct contributions to carbohydrate metabolism, cell morphology, stress tolerance, and virulence [42].

In 2018, a CRISPR-Cas9-driven gene drive system was introduced, enabling the efficient construction of a comprehensive C. albicans double-gene knockout library for systematic genetic interaction studies [43]. Exploiting the organism’s capacity for haploid mating [44], the platform utilizes a so-called gene drive that knocks out a target gene in haploid cells. When these engineered haploids are crossed with wildtype haploids, the gene drive element induces loss of the corresponding wildtype allele in the resulting diploid, thereby producing homozygous deletions. By pairing haploids with each harboring distinct gene deletions, the method facilitates the rapid generation of diploid strains lacking two genes. These double mutants can then be systematically analyzed alongside their respective parental single-gene deletion strains to elucidate genetic interactions and begin mapping the regulatory and functional relationships of the target genes [43,45,46].

Although the aforementioned genome editing strategies are powerful advancements, their applicability is often constrained by the requirement for a CRISPR-Cas9 target site to directly overlap the locus of interest. To overcome this limitation, a novel two-step genome editing approach has been developed [47]. In the first step, Cas9 is guided to introduce a DSB at a defined site close to the genomic feature of interest. This facilitates the replacement of the target site and any intervening sequence by a unique synthetic target sequence termed “AddTag.” In the second step, Cas9 is directed to the AddTag site, enabling the precise insertion of any desired DNA sequence in place of the initially deleted genomic region [47]. This platform, when combined with existing CRISPR engineering methods, enables highly versatile and scarless genome editing without the permanent incorporation of selectable markers [41,47].

3.2. Modalities for RNA Targeting and Modulation

Conventional CRISPR platforms typically induce targeted DSBs, followed by repair through a multitude of methods. However, alternative CRISPR systems have emerged that bypass genome cleavage. Among these, CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) and CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) serve as molecular tools to modulate transcriptional activity without altering the target DNA sequence. Earlier advancements in Cas9 engineering revealed that specific amino acid residues can remove its nuclease function while preserving its DNA-binding ability [48,49]. These catalytically inactive variants, referred to as endonuclease-dead Cas9 (dCas9), function as customizable DNA-binding platforms that can recruit effectors to designated genomic sites. When tethered to transcriptional regulators and directed to promoter regions, dCas9 can mediate locus-specific gene regulation [28]. In C. albicans, CRISPRi was first demonstrated through two distinct dCas9 fusion strategies [34,50]. One approach utilized dCas9 linked to the mammalian Mxi1 repression domain, resulting in approximately 20-fold gene repression—substantially higher than the ~7-fold repression seen with dCas9 alone [50]. This system proved especially useful in functional studies of essential genes [51]. Notably, downregulation of the essential chaperone gene HSP90 using this system increased susceptibility to antifungal drugs, in accordance with findings from previous research [50,52]. A second CRISPRi design employed a fusion of dCas9 with the native C. albicans transcriptional repressor Nrg1, known for its role in suppressing hyphal development [34]. This construct was guided to the CAT1 gene encoding catalase, leading to elevated oxidative stress sensitivity and demonstrating effective transcriptional repression in the range of 40–60% [34]. Thus, CRISPRi represents a precise and efficient method for targeted gene repression or functional depletion in C. albicans (Figure 2) [34,50].

CRISPRa operates analogously to CRISPRi by utilizing the same catalytically inactive dCas9 carrier. However, instead of recruiting a repressor, CRISPRa directs a transcriptional activator to the promoter region of the target gene. Román et al. [34] achieved this by fusing dCas9 with the transcriptional activation domains Gal4 and/or VP64, targeting the CAT1 promoter in a manner similar to repressor-based CRISPRi constructs. The resulting CRISPRa strains exhibited increased resistance to hydrogen peroxide and elevated CAT1 transcript levels, confirming effective transcriptional activation. These findings demonstrate that the dual-activation CRISPRa system is capable of inducing gene expression in C. albicans. In 2022, Gervais et al. [53] took advantage of a CRISPRa system in C. albicans by exploiting a tripartite activator complex, previously optimized for S. cerevisiae [54], fused to dCas9. This system is distinct from other CRISPR-based gene activation platforms developed for C. albicans because it utilizes an efficient, single-plasmid design that takes advantage of rapid Golden Gate cloning and thus can streamline C. albicans strain engineering. Its broad applicability across various C. albicans genetic backgrounds, including clinical isolates, makes it convenient for high-throughput applications. Consequently, this CRISPRa platform could facilitate the generation of large-scale CRISPRa libraries, which already contributed significantly to the understanding of molecular mechanisms in other organisms [55,56,57,58].

3.3. Diagnostic Methods

Beyond, a diagnostic method combining CRISPR-Cas12a with thermally driven recombinase amplification has been recently introduced for the detection of C. albicans (Figure 2) [59,60]. This approach uses the unique mechanism of Cas12a, which undergoes a structural transformation upon crRNA-directed recognition and binding to a specific DNA sequence. This change initiates its trans-cleavage function, enabling degradation of surrounding labeled single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) and thus generating a signal that can be visualized via fluorescence or lateral flow assay platforms. The technique is structured in two independent steps. Initially, target DNA undergoes amplification via enzymatic recombinase amplification (ERA), found to have superior sensitivity [59]. Subsequently, detection is achieved through a CRISPR-Cas12a-mediated trans-cleavage reaction. These two processes are integrated into a unified, temperature-regulated, single-tube ERA-CRISPR-Cas12a detection platform [59]. In this configuration, amplification and detection are initially segregated by a wax barrier. The ERA reaction is conducted at 37 °C. Upon completion, the system is heated to 45 °C, causing the wax to melt and enabling the CRISPR-Cas12a detection reagents to merge with the amplification products [59]. This technique proves the versatile applicability of the CRISPR system in C. albicans beyond foundational research.

Table 1.

Overview of published CRISPR-based gene manipulation methods in Candida albicans.

Table 1.

Overview of published CRISPR-based gene manipulation methods in Candida albicans.

| Species | Delivery | Activity | Other Features | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Candida albicans | Single-plasmid system (Cas9 + sgRNA combined) Dual-plasmid system (Cas9 + sgRNA on separate plasmids) | Genomic integration of CRISPR components at ENO1 locus | Marker Recycling | Vyas et al., 2015 [36] |

| Candida albicans | PCR-derived cassette transformation | Transient expression | Built on Vyas et al., 2015 [36] | Min et al., 2016 [37] |

| Candida albicans | Dual-plasmid system (Cas9 + sgRNA on separate plasmids) | Genomic integration of CRISPR components at ENO1 locus | Marker Recycling, adapted from Vyas et al., 2015 [36] | Ng and Dean 2017 [61] |

| Candida albicans | PCR-derived cassette transformation | Transient expression | Marker Recycling, built on Min et al., 2016 [37] | Huang and Mitchell, 2017 [40] |

| Candida albicans | PCR-derived cassette transformation | Transient genomic integration of CRISPR components at HIS1 locus or LEU2 locus | Marker Recycling | Nguyen et al., 2017 [41] |

| Candida albicans | PCR-derived cassette transformation | Genomic integration of CRISPR components at NEUT5L locus | Gene drive array (GDA)—platform | Shapiro et al., 2018 [33] |

| Candida albicans | Single-plasmid system (Cas9 + sgRNA combined) | Transient genomic integration of CRISPR components at NEUT5L locus | Marker Recycling | Vyas et al., 2018 [62] |

| Candida albicans | PCR-derived cassette transformation | Genomic integration of CRISPR components at ADH1 locus (CAS9) and RP10 locus (sgRNA) | CRISPR interference (CRISPRi, dCas9 repression) CRISPR type: CRISPR activation (CRISPRa, dCas9 activator) | Román et al., 2019 [34] |

| Candida albicans | Single-plasmid system (Cas9 + sgRNA combined) | Genomic integration of CRISPR components at NEUT5L locus | CRISPR interference (CRISPRi, dCas9 repression) | Wensing et al., 2019 [50] |

| Candida albicans | PCR-derived cassette transformation | Transient genomic integration of CRISPR components at HIS1 locus or LEU2 locus | AddTag two-step approach, based on Nguyen et al., 2017 [41] | Seher et al., 2021 [47] |

| Candida albicans | Single-plasmid system (Cas9 + sgRNA combined) | Genomic integration of CRISPR components at NEUT5L locus | CRISPR activation (CRISPRa, dCas9 activator) | Gervais et al., 2023 [53] |

| Candida albicans | Cas12a-based | Diagnostic purposes | Zeng et al., 2025 [59] | |

| Candida albicans | Cas12a-based | Diagnostic purposes | Liu et al., 2025 [60] |

4. CRISPR in NAC Species

Following their initial development in C. albicans, CRISPR-based genome editing approaches were gradually adapted to other candidiasis-promoting pathogens, commonly referred to as NAC species. In some cases, CRISPR-Cas9 systems originally optimized for S. cerevisiae or C. albicans could be directly applied to NAC species without major modification. However, substantial interspecies differences necessitated species-specific adaptations [12].

To overcome the requirement for species-specific expression of Cas9 and sgRNAs via plasmid-based systems, an alternative ribonucleoprotein (RNP)-mediated strategy was developed (Figure 2) [63]. In this approach, recombinant Cas9 protein is assembled in vitro with CRISPR RNAs (crRNA and tracrRNA), and the resulting RNP complexes are delivered into the cells together with donor DNA templates to facilitate homology-directed repair [35,63]. This method demonstrated broad applicability across NAC species and improved transformation efficiencies in several clinical isolates [63]. Importantly, the RNP approach circumvents the need for selectable markers, plasmids, or species-specific promoters, making it particularly advantageous for species with limited molecular genetic tools. Although this system was specifically developed for NAC species, its benefits also render it a good choice for C. albicans [64]. Nevertheless, its reliance on purified Cas9 protein causes the approach to be more costly than plasmid-based systems.

As a result, CRISPR-based research in Candida spp. and related species has progressed along two parallel trajectories: The development of expression-free, RNP-based platforms and the establishment of species-optimized, plasmid-driven CRISPR-Cas9 approaches [35,63]. In the following, we will discuss the emergence and implementation of these species-specific CRISPR systems (Table 2).

Table 2.

Overview of published CRISPR-based gene manipulation methods in NAC species.

4.1. Nakaseomyces Glabratus (Formerly Classified as Candida glabrata)

Unlike C. albicans, which actively invades the host, N. glabratus appears to rely on a “stealth” strategy within the host, i.e., its ability to persist by evading immunity without provoking strong inflammation [79,80]. Hallmark virulence traits of C. albicans, like hyphal differentiation or the secretion of proteolytic enzymes, are absent in N. glabratus. Comparative genomics has revealed that N. glabratus is evolutionarily more closely aligned with S. cerevisiae than with members of the Candida CTG clade [81], supporting the hypothesis that human pathogenicity in N. glabratus arose via a phylogenetic path distinct from that of other Candida spp. [82,83]. Thus, it was possible to rapidly establish CRISPR-based genome editing systems for N. glabratus by adapting CRISPR methods originally introduced for S. cerevisiae [65]. For instance, unlike in many Candida spp, in N. glabratus, episomal plasmids remain stable, enabling independent expression of both Cas9 and sgRNAs. To accommodate species-specific transcriptional environments, two alternative sgRNA expression systems have been evaluated. One utilizes the RNA polymerase III-driven SNR52 promoter from S. cerevisiae, and the other employs N. glabratus’s RNAH1 promoter paired with a tRNA-Tyr-derived terminator. For the Cas9 nuclease, the conventional S. cerevisiae TEF1 promoter was replaced with the endogenous pCYC1 promoter from N. glabratus. These adaptations to N. glabratus significantly improved its viability and increased the efficiency of homologous recombination [65]. The latter is particularly noteworthy, as N. glabratus differs from C. albicans or S. cerevisiae, which predominantly rely on HDR for DNA double-strand break repair; instead, N. glabratus employs both HDR and NHEJ [62]. To guide the cell’s repair toward HDR, two different disruption cassettes were successfully transformed as donor templates in parallel with Cas9 and sgRNA plasmids, disrupting the ADE2 locus and thus paving the way for precise gene modification in N. glabratus via HDR [65].

In an effort to streamline the CRISPR-Cas9 technology in N. glabratus, Vyas et al. [62] engineered a “unified” plasmid system in which the Cas9 nuclease, sgRNA, and donor DNA are all encoded within a single construct. The so-called “Unified Solo CRISPR system” eliminates the need for separate expression vectors and enables high-throughput mutagenesis and efficient plasmid recycling for repeated rounds of genome editing. Notably, using the “Unified Solo CRISPR” as a framework, an inducible Cas9 construct driven by the MET3 promoter was introduced, combined with URA3 as a selectable marker [66,84]. This is interesting, since up to that point, all available CRISPR-Cas9 platforms in N. glabratus had relied on constitutive promoters, resulting in continuous expression of Cas9 and sgRNAs immediately after transformation [65]. In contrast, an inducible system separates the transformation from the DNA cleavage, thereby enabling controlled assessment of mutant formation [66]. Accordingly, the mentioned approach of inducible Cas9 expression was able to successfully decouple transformation from Cas9 activation. However, the original plasmid showed instability in E. coli due to f1 ori DNA sequence repeats, leading to frequent rearrangements [67]. To overcome this limitation, a redesigned plasmid with improved structural stability was generated. When tested on the ADE2 locus, the optimized construct yielded nearly complete disruption efficiency via NHEJ, thus inactivating the ADE2 gene [67].

Besides the strategies based on gene disruption, transcriptional upregulation by employing a catalytically inactive dCas9 fused to transcriptional activators (CRISPRa, see above) has also been investigated in N. glabratus. A recent study used a centromeric plasmid carrying dCas9 coupled to the VP64-p65-Rta (VPR) tripartite activation complex [68]. With this system, target genes exhibited enhanced expression ranging from approximately 1.5- to 8-fold above baseline. Moreover, the magnitude of gene induction was shown to depend on the position of the sgRNA within the promoter, providing a titratable transcriptional control [68]. This CRISPR-based tool not only enables in-depth functional genetic analysis in N. glabratus but also lays a foundation for efficient generation of large-scale, high-throughput genetic libraries.

4.2. Candida parapsilosis

As one of the most relevant species of life-threatening candidaemia due to the rise in azole-resistant variants, Candida parapsilosis has been the target of continuous efforts to explore its biology and understand its virulence [85]. In 2017, a transient plasmid-based CRISPR-Cas9 system for gene editing in C. parapsilosis was developed, which is applicable even in clinical isolates [70]. The approach uses a codon-optimized CAS9 under control of the TEF1 promoter, carried on an autonomously replicating plasmid. The sgRNAs are expressed on the same plasmid via one of two distinct promoters: either from a putative SNR52 RNA polymerase III promoter (pSNR) plus a SUP4 terminator, or from a strong RNA polymerase II promoter (pGAPDH) flanked by a 5′ hammerhead (HH) and a 3′ hepatitis delta virus (HDV) ribozyme (pRIBO) to generate mature sgRNA. Editing was tested initially at the ADE2 locus by observing whether transformants displayed the ∆ade2 phenotype (using the PCR repair template), efficiencies of 10–50% were observed with the pSNR strategy yielded efficiencies of 10–50%, the pRIBO design achieved 80–100% efficiency [70]. The system was applied to 20 diverse C. parapsilosis isolates, and in nearly all strains, ADE2 editing succeeded with repair template. In many cases, the ADE2 disruption was also obtained even without repair template (via NHEJ-induced indels). However, additional genes in different strain backgrounds were edited with variable success, ranging from unsuccessful to 100% success rate [70].

The implementation of a transient, plasmid-based CRISPR-Cas9 system with a dominant drug resistance marker circumvents the requirement for auxotrophic strains, thereby enabling genetic manipulation without altering virulence. The downside of the pRIBO system is, however, that it is not suitable for large-scale generation of mutant strains. Thus, in 2019, an update of the protocol was published, merging the insertion of the sgRNA sequence in between the two ribozyme sequences into one step [71]. Additionally, the HH ribozyme sequence was replaced by the species-specific tRNA sequence, streamlining the cloning process thanks to its generic usability with a similar efficiency [71]. Notably, this transient CRISPR-Cas9 system has subsequently been adapted for use in species phylogenetically related to C. parapsilosis, including Candida orthopsilosis [73] and Candida metapsilosis [71].

Notably, in diploid species, careful validation of the underlying cause of any observed phenotypic changes is essential. In C. parapsilosis, Cas9-induced double-strand breaks have been shown to promote loss of heterozygosity [86]. This process can promote homozygosity in deleterious heterozygous variants, thereby generating unintended gene modifications and thus phenotypic outcomes. Consequently, mutation complementation and the analysis of multiple independent clones remain a critical step even when employing CRISPR-Cas9-based genome editing.

Recently, a PCR-based CRISPR-Cas9 approach was developed to enable rapid fluorescent labeling of C. parapsilosis isolates [72]. Using a strategy originally designed for C. albicans as a framework [41], the workflow was adapted to integrate eight distinct fluorescent protein-coding genes into donor DNA constructs. The system efficiently generated homozygous knock-in mutants in clinically relevant prototrophic isolates in a single round of transformation. Importantly, targeted modification of the neutral intergenic CpNEUT5L locus did not affect growth in rich media, confirming its suitability as a safe harbor site for fluorescent markers. The editing efficiency exceeded 80%, with 20 out of 24 analyzed clones carrying the desired modification. The system allows for selectable markers to be maintained on plasmids or integrating constructs rather than being incorporated into donor DNA. Such marker-recyclable editing represents a major advantage of current CRISPR-Cas9 systems compared with earlier genome modification strategies, including initial CRISPR-Cas9 applications, where residual exogenous sequences remained at the targeted locus [12]. These leftovers often raised concerns about whether observed phenotypes resulted from the intended mutation or from the presence of exogenous elements [87].

In aggregate, two basic CRISPR-Cas9-based genome editing strategies have been established for C. parapsilosis, including a plasmid-based system [70] and an integrating approach [72]. Each of these methods offers benefits and limitations, as discussed above. Consequently, the choice of system should be guided by the specific experimental objectives.

4.3. Candida tropicalis

Beyond its medical relevance, especially also related to increased antifungal drug resistance rates, Candida tropicalis has received considerable attention for its biotechnological potential, particularly in the production of valuable biomolecules such as ethanol, xylitol, and biosurfactants [88,89]. Consequently, the development of efficient and rapid genetic engineering tools for this species is of multifaceted interest. The groundwork for a functioning transient CRISPR-Cas9 system in C. tropicals was already laid by previously identified suitable promoters and terminators [90]. Building upon these resources, Lombardi et al. [71] designed CRISPR-Cas9-based systems not only for C. parapsilosis, C. orthopsilosis, and C. metapsilosis, but also adapted prior constructs for application in C. tropicalis. They engineered a plasmid in which CAS9 was expressed under the Meyerozyma guilliermondii pTEF1 promoter, SAT1 under the Candida dubliniensis pTEF1 promoter, and a tRNA-sgRNA-ribozyme cassette positioned between the Ashbya gossypii pTEF1 promoter and the S. cerevisiae CYC1 terminator. A key advantage of this construct is its modularity, as most components can be readily exchanged thanks to strategically placed restriction sites. Using this system, highly efficient genome editing was achieved. Introduction of premature stop codons into the ADE2 locus via HDR templates yielded efficiencies of 88–100% [71]. Of note, in the absence of a donor DNA, NHEJ proved to be highly effective in C. tropicalis [71].

Although RNA polymerase III promoters are commonly applied for sgRNA expression, no experimentally validated RNA polymerase III promoters with defined transcription start sites have been identified in C. tropicalis. To overcome this limitation and systematically evaluate regulatory elements for CAS9 and sgRNA expression, eight RNA polymerase II promoters were screened for activity and compatibility. Among these, PGAP1 and PFBA1 demonstrated the highest expression strengths and were selected for driving CAS9 and sgRNA expression, respectively. This was the basis for the establishment of two alternative CRISPR-Cas9 platforms [74], one that employed a transient, plasmid-based delivery strategy and another that utilized a genomic integration approach. Using the transient system, single-gene disruptions were achieved with efficiencies ranging from 57% to 100%, while multiplex gene deletions reached approximately 32%. Similarly to the initial plasmid-based CRISPR-Cas9 system reported for C. tropicalis, this transient approach induced negligible NHEJ events when a homologous repair template was supplied. Additionally, the present system does, likewise, not require genomic integration of selection markers [74]. In contrast, application of the integrative system, targeted to the POX4 locus and combined with a repair template, resulted in an HDR efficiency of 100% [74].

As mentioned, the limited availability of RNA polymerase III promoters in C. tropicalis has challenged the development of efficient sgRNA expression platforms. To address this limitation, a tRNA:gRNA-based system was established [75]. An endogenous tRNAGly gene was identified in C. tropicalis and utilized as a functional RNA polymerase III promoter to enable the expression of multiple gRNAs for single-gene disruption. Integration of a transient CRISPR-Cas9 cassette fused to the tRNA:gRNA array targeting URA3, together with a donor DNA, resulted in successful genome editing in all tested colonies. Following the robust single-gene editing, the system was expanded to express multiple sgRNAs for Cas9-mediated multiplexed targeting. When simultaneously targeting GFP3 and URA3, approximately 71% of colonies displayed the expected dual modifications [75].

Subsequently, the first CRISPRi system in C. tropicalis was developed, employing the constitutive GAP1 promoter and the ENO1 terminator [74] to drive the expression of a catalytically inactive Streptococcus pyogenes dCas9 [75]. To evaluate transcriptional repression, GFP3 and ADE2 were selected as reporter genes. Targeting GFP3 within the coding sequence consistently reduced fluorescence intensity to 34.3–39.1% of control levels. In contrast, repression of ADE2 varied substantially, ranging from no detectable silencing to 38% expression levels compared to the control, depending on the gRNA target site within the promoter region [75]. Although the CRISPRi system in C. tropicalis requires further refinement to achieve consistent repression efficiencies, it demonstrates strong potential for both biomedical and industrial applications.

4.4. Candida lusitaniae

Although infections caused by Candida lusitaniae generally demonstrate relatively low mortality rates of approx. 5%, this species is being increasingly recognized as a critical clinical challenge due to its emerging resistance to multiple antifungal classes, including amphotericin B, 5-fluorocytosine, and fluconazole [91]. In 2017, the first and, to date, only C. lusitaniae-specific CRISPR-Cas9 system was introduced [69]. This transient system is based on two plasmids: one encoding CAS9 under the constitutive TDH3 promoter, and another expressing the sgRNA under the RNA polymerase III promoter pSNR52. The use of these species-specific promoters proved necessary for efficient gene targeting and was successfully applied to multiple loci in both haploid and diploid cells [69]. To enable HDR, a repair template containing a codon-optimized SAT1 flipper selection marker [20] was provided. Nonetheless, the overall targeting efficiency remained relatively low in both haploid and diploid cells [69]. As in most Candida and related species, DSB repair in C. lusitaniae can occur through the two competing pathways, HDR or NHEJ. The limited HDR efficiency was therefore attributed to the preferential use of NHEJ. To test this hypothesis, the genes KU70 and LIG4, both essential components of NHEJ, were deleted in a haploid C. lusitaniae background. Deletion of KU70 increased ADE2 gene disruption efficiency from 25% to 49%, while combined deletion of KU70 and LIG4 further enhanced efficiency to 81% [69]. Despite these improvements, NHEJ-deficient mutants have substantial limitations, as disruption of this pathway can impair virulence traits, as previously demonstrated in C. albicans [35,92].

4.5. Candida auris

The fungal pathogen Candida auris often displays multidrug resistance and a significant mortality rate, becoming an urgent health threat, especially in the frame of nosocomial infections [93]. C. auris has proven exceptionally difficult to manipulate genetically, driving the adaptation or development of several CRISPR-Cas9-based systems. Each system follows distinct strategies for delivering and expressing Cas9 and sgRNA and for managing selection markers and genomic scars. Of note, these systems vary considerably in efficiency and suitability across different C. auris clades.

The first CRISPR approach specifically adapted for C. auris was the ENO1 stable integration system, originally described by Vyas et al. [36] and later applied in C. auris by Kim et al. [76]. This system integrates Cas9 and sgRNA expression cassettes at the ENO1 locus, theoretically allowing continuous Cas9 expression. In practice, it yielded the highest number of transformants in screening experiments but showed very low PCR-verified editing efficiency, averaging only 5.6% [94].

Besides this stable integration system, two temporary strategies were also designed. The LEU2-targeting system, known as LEUpOUT, was developed by Nguyen et al. [41] and optimized for C. auris by Ennis et al. [77]. In this approach, the CRISPR-Cas9 cassette integrates at the LEU2 locus, disrupting it during editing. Later, the CRISPR-Cas9 cassette is, however, removed by homologous recombination, restoring LEU2. This enables repeated use of the same marker in consecutive transformation rounds. Ennis et al. reported an across-clade average efficiency of 40% for CAS5 deletion and 99% for CAS5 restoration at the native locus. Nevertheless, overall PCR-verified correct transformants remained low, at only 5.8% on average, with performance strongly dependent on clade and locus [94].

In parallel to these strategies, which build upon integration, plasmid-based approaches were also developed. The Episomal Plasmid-Induced Cas9 system (EPIC) uses the autonomously replicating sequence CpARS7 from C. parapsilosis and has been readily applied to C. auris [78]. This system delivers Cas9 and sgRNA from an episomal plasmid maintained under nourseothricin selection, which can be lost upon removal of selection pressure, providing a scarless editing strategy. Genomic epidemiology has identified four independent emergences of C. auris, represented by four genetically distinct clades that exhibit varying levels of antifungal resistance and are expected to continue diverging phenotypically [95]. These underlying genetic and phenotypic differences among clades may contribute to the variable editing outcomes observed with the EPIC system. Among all tested systems, EPIC displayed the highest editing accuracy, with an average of 41.9% correct transformants, and efficiencies exceeding 50% in Clade I and III strains. However, the system did not yield any correct transformants in Clade IV backgrounds [94].

The current approaches demonstrate that CRISPR-mediated genome editing in C. auris is feasible but remains technically challenging, with system- and clade-dependent differences in efficiency.

5. CRISPR-Cas9 as an Accelerator of Candidiasis Research

5.1. Pathogenicity of Candidiasis-Associated Species

Since its introduction into the fungal genetic toolbox, CRISPR-Cas9 technology has markedly enhanced the study of candidiasis-associated yeast species by enabling precise and efficient genome editing across multiple isolates. In fact, the CRISPR system has been adapted for diverse purposes beyond gene deletion, including promoter replacement, point mutation introduction, and gene family targeting by using a single sgRNA [36,62]. The flexibility and efficiency of CRISPR-Cas9 have allowed for the systematic dissection of both conserved and species-specific biological processes in candidiasis-related pathogens. This has been (and is) determinant in advancing the understanding of cellular mechanisms that underpin virulence, host interaction, and antifungal resistance.

One of the earliest milestones facilitated using CRISPR in C. albicans was the elucidation of genetic networks controlling morphogenesis and biofilm formation. Through large-scale CRISPR-based mutant screens, numerous genes and pathways involved in filamentation were identified, revealing the intricate regulation of this morphological switch [36,96,97,98,99,100,101,102]. Other early CRISPR-related efforts contributed, for example, to conceptualizing that cell cycle arrest may promote hyphal growth and biofilm development independently of major biofilm regulators [103]. These findings represented an important advance, linking fundamental cell biology with virulence-associated morphogenesis.

CRISPR applications rapidly expanded beyond C. albicans to other pathogenic species, including N. glabratus, C. parapsilosis, C. orthopsilosis, and C. auris, where targeted gene deletions clarified the roles of adhesins in host colonization and virulence [65,73,104,105]. A particularly innovative use of the technology was the simultaneous knockout of entire adhesin gene families by using a single sgRNA that targets conserved regions. This strategy enabled functional dissection of previously redundant adhesin systems [106]. CRISPR-based gene drive systems further accelerated the generation of combinatorial mutants, allowing for the systematic mapping of genetic interactions among adhesins. Shapiro et al. [43], for example, employed such a platform to create a comprehensive library of single and double adhesin mutants in C. albicans, identifying epistatic relationships that determined biofilm formation under diverse environmental conditions. These studies demonstrated that virulence traits are often regulated by complex genetic interactions, rather than single genes, highlighting the power of CRISPR-driven genomics to unravel multifactorial phenotypes.

Building on these developments, CRISPR was harnessed to generate combinatorial mutants for metabolic and virulence studies. This is illustrated by studies like the one by Wijnants et al. [107], who used a marker-recycling system to construct double, triple, and quadruple mutants of C. albicans sugar kinase genes (HXK1, HXK2, GLK1, GLK4), revealing how glycolytic regulation influences adhesion, filamentation, and pathogenicity. This work linked metabolic plasticity to virulence, showing that defects in glycolysis can alter biofilm formation and infection outcomes in murine models. Such comprehensive mutant libraries, made feasible through CRISPR, have fundamentally reshaped the capacity to interrogate pathway interconnectivity in candidiasis-associated yeast biology.

5.2. Host–Pathogen Interactions

Beyond pathogenicity, CRISPR systems have also advanced understanding of host–pathogen interactions by enabling precise genetic manipulation of both fungal and host cells. For example, mutants deficient in key regulators of β-glucan masking revealed how C. albicans modulates its cell wall composition to evade immune recognition [108,109]. Parallel CRISPR studies in mammalian cells elucidated host defense mechanisms, identifying roles for sphingolipid biosynthesis, C-type lectin receptor signaling, and neutrophil/IL-17F activation in antifungal immunity [110,111,112,113]. Together, these investigations have established CRISPR as a tool to break down the complex interplay between fungal virulence and host immune pathways.

The impact of CRISPR also extends to the field of antifungal drug resistance. By enabling precise genetic validation of resistance-conferring mutations, CRISPR has helped clarify the molecular basis of susceptibility to azoles, polyenes, echinocandins, and emerging antifungal compounds. For instance, targeted editing in C. lusitaniae confirmed that a single amino acid substitution in the transcription factor MRR1 conferred resistance to both fluconazole and 5-fluorocytosine through activation of the efflux transporter MFS7 [114]. CRISPR-based editing in N. glabratus also verified that valine-to-alanine substitutions in Gwt1, an important enzyme for glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor biosynthesis and thus structural integrity of the cell wall, decreased susceptibility to the investigational antifungal Manogepix [115]. Furthermore, CRISPR-Cas9 editing was employed to introduce a single point mutation at a conserved phosphorylation site within the cell wall integrity regulator CAS5, demonstrating that this alteration disrupts nuclear localization upon caspofungin exposure in C. auris [77]. More recently, CRISPR-based functional analyses allowed for the investigation of mechanisms underlying C. auris Amphotericin B resistance and its associated fitness costs. Using targeted mutagenesis, researchers confirmed that modulation of the sterol biosynthesis genes ERG3, ERG6, ERG10, ERG11, HMG1, or NCP1 confers Amphotericin B resistance, thereby providing direct genetic validation of the mutations driving this clinically significant phenotype [78].

Beyond validating known mechanisms, CRISPR has been instrumental in identifying novel antifungal targets. As an example, CRISPR-mediated deletion of CDC8 and CDC43 homologs, corresponding to S. cerevisiae genes essential for DNA replication and morphogenesis, respectively, produced severe fitness defects in C. albicans and N. glabratus, highlighting their potential as antifungal targets [116,117]. The ability to construct conditional alleles and employ CRISPRi systems has further expanded the scope of genetic manipulation to essential genes that cannot be deleted outright. For instance, repression of the chaperone HSP90 via CRISPRi recapitulated loss-of-function phenotypes, illustrating a strategy to study essential gene function while avoiding lethality [50]. Additionally, the exploitation of CRISPRa systems has expanded experimental possibilities by enabling precise gene overexpression. This approach facilitated detailed characterization of the mitogen-activated protein kinases STE11 and SLT2 in N. glabratus, revealing that their upregulation enhances tolerance to caspofungin [68]. These methodological strategies have positioned CRISPR not only as a discovery tool but also as a platform for preclinical drug target validation.

Altogether, these examples showcase that CRISPR has significantly advanced the field of genetics in candidiasis-associated species, from the rapid generation of single and combinatorial gene deletions to the functional analysis of essential genes and elucidation of drug resistance mechanisms.

6. Conclusions and Future Directions

CRISPR-Cas, which naturally occurs as a prokaryotic adaptive immune system that protects bacteria from bacteriophage infection, has been repurposed as a powerful genome-engineering platform across species. Since its first adaptation to C. albicans in 2015, subsequent refinements and species-specific adaptations have rapidly expanded its utility in different candidiasis-associated yeast species, i.e., enabling marker-recyclable genome editing and transient expression systems. Emerging CRISPR-based technologies have further extended the platform’s applications to epigenetic regulation, such as targeted gene interference or activation, and to diagnostic approaches.

Despite the rapid advancements thanks to various CRISPR systems, they are still subject to a range of limitations. CRISPR-Cas genome editing in candidiasis-associated yeast species, in particular, is constrained by both biological and technical limitations that vary across species and strains. The system depends on the induction of DSBs and their repair via host pathways, yet the balance between HDR and NHEJ differs markedly among candidiasis-associated pathogens. For instance, elevated NHEJ activity, as observed in C. lusitaniae, or strain- and locus-dependent variability, as in C. parapsilosis, leads to inconsistent editing efficiencies [69,70]. Consequently, species-specific optimization, including tailored promoters for Cas9 and sgRNA expression, is required, although suitable regulatory elements remain unidentified for many species [35,61]. Editing efficiency is also locus-dependent and influenced by sgRNA design, repair template configuration, and chromatin accessibility. Secondary structure compatibility of sgRNAs and local nucleosome occupancy can hinder Cas9 targeting, necessitating empirical testing of multiple sgRNAs per gene [118,119,120]. While computational tools such as EuPaGDT or Benchling facilitate sgRNA design and off-target prediction, their advanced applications are largely restricted to well-studied species like C. albicans [41,121,122]. Targeting is further limited by PAM sequence requirements [62]. Furthermore, constitutive Cas9 expression and DSB formation can induce DNA damage and cytotoxicity, with stable genomic integration posing greater risks than transient expression systems [35,37]. Despite these limitations, the capacity of CRISPR-Cas to link genotype to phenotype with precision has already markedly accelerated discovery across diverse research domains in the field, including pathogenesis, host–pathogen interaction, and antifungal pharmacology. In fact, the full range of possibilities is expected to unfold as the existing limitations are progressively overcome.

Future developments in CRISPR technologies may even further expand its applicability against candidiasis. This may include, for instance, the tractability of a broader range of candidiasis-associated species, but also the establishment of genome-wide CRISPRi and CRISPRa libraries to enable systematic functional analysis of epigenetic traits. Moreover, in vivo CRISPR approaches may allow for genetic perturbation during infection and real-time dissection of host–pathogen interactions. Further developments may include engineering of candidiasis-associated yeast strains for therapeutic purposes, such as the development of attenuated live vaccines or exploring guide-directed lethal editing of pathogenic fungi.

In any case, CRISPR-Cas-associated innovations have already assumed a transformative role in Candida research, enabling rapid and precise genetic studies across a wide range of applications, including basic biology, pharmacological targeting, and diagnostics.

Author Contributions

A.S., K.K. and D.C.-G. conceptualized the article; A.S., K.K. and M.A.B. performed the literature searches, organized sources, and extracted information; A.S. prepared the figure and table; A.S. and D.C.-G. wrote the initial draft; all authors contributed to revising, refining, and critically reviewing the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded in whole, or in part, by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) [10.55776/P37278].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We thank the University of Graz (Institute of Molecular Biosciences) for financial support. DCG and KK are grateful to the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) for grant 10.55776/P37278 (project no. P37278). For the purpose of open access, the author has applied a CC BY public copyright license to any author-accepted manuscript version arising from this submission. We thank Martin Odabas for support in generating Figure 1 and Figure 2 in BioRender: Odabas, M. (2026) https://BioRender.com/k6d4x83 (accessed on 26 January 2026).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NAC | non-albicans Candida |

| CRISPR | clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats |

| FRT | flippase recognition target |

| FLP | recombinase flippase |

| Cas | CRISPR-associated |

| crRNAs | CRISPR-derived RNAs |

| sgRNA | synthetic guide RNA |

| DSB | double-stranded break |

| tracrRNA | trans-activating CRISPR RNA |

| PAM | protospacer adjacent motif |

| HDR | homology-directed repair |

| NHEJ | non-homologous end joining |

| indels | insertions or deletions |

| CRIME | CRISPR-mediated marker excision |

| CRISPRa | CRISPR activation |

| CRISPRi | CRISPR interference |

| dCas9 | endonuclease-dead Cas9 |

| ssDNA | single-stranded DNA |

| ERA | enzymatic recombinase amplification |

| EPIC | Episomal Plasmid-Induced Cas9 system |

| GRACE | Gene Replacement and Conditional Expression |

References

- Kreulen, I.A.M.; de Jonge, W.J.; van den Wijngaard, R.M.; van Thiel, I.A.M. Candida spp. in Human Intestinal Health and Disease: More than a Gut Feeling. Mycopathologia 2023, 188, 845–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Hu, Z.-D.; Zhao, X.-M.; Zhao, W.-N.; Feng, Z.-X.; Yurkov, A.; Alwasel, S.; Boekhout, T.; Bensch, K.; Hui, F.-L.; et al. Phylogenomic Analysis of the Candida auris-Candida haemuli Clade and Related Taxa in the Metschnikowiaceae, and Proposal of Thirteen New Genera, Fifty-Five New Combinations and Nine New Species. Persoonia 2024, 52, 22–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallotta, F.; Viale, P.; Barchiesi, F. Candida auris: The New Fungal Threat. Infez. Med. 2023, 31, 323–328. [Google Scholar]

- Katsipoulaki, M.; Stappers, M.H.T.; Malavia-Jones, D.; Brunke, S.; Hube, B.; Gow, N.A.R. Candida albicans and Candida glabrata: Global Priority Pathogens. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2024, 88, e00021-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takashima, M.; Sugita, T. Taxonomy of Pathogenic Yeasts Candida, Cryptococcus, Malassezia, and Trichosporon: Current Status, Future Perspectives, and Proposal for Transfer of Six Candida Species to the Genus Nakaseomyces. Med. Mycol. J. 2022, 63, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borman, A.M.; Johnson, E.M. Name Changes for Fungi of Medical Importance, 2018 to 2019. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2021, 59, e01811-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denning, D.W. Global Incidence and Mortality of Severe Fungal Disease. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, e428–e438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazi, P.B.; Olsen, M.A.; Stwalley, D.; Rauseo, A.M.; Ayres, C.; Powderly, W.G.; Spec, A. Attributable Mortality of Candida Bloodstream Infections in the Modern Era: A Propensity Score Analysis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 75, 1031–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parambath, S.; Dao, A.; Kim, H.Y.; Zawahir, S.; Alastruey Izquierdo, A.; Tacconelli, E.; Govender, N.; Oladele, R.; Colombo, A.; Sorrell, T.; et al. Candida albicans—A Systematic Review to Inform the World Health Organization Fungal Priority Pathogens List. Med. Mycol. 2024, 62, myae045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano, A.; Honore, P.M.; Puerta-Alcalde, P.; Garcia-Vidal, C.; Pagotto, A.; Gonçalves-Bradley, D.C.; Verweij, P.E. Invasive Candidiasis: Current Clinical Challenges and Unmet Needs in Adult Populations. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2023, 78, 1569–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schikora-Tamarit, M.À.; Gabaldón, T. Recent Gene Selection and Drug Resistance Underscore Clinical Adaptation across Candida Species. Nat. Microbiol. 2024, 9, 284–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uthayakumar, D.; Sharma, J.; Wensing, L.; Shapiro, R.S. CRISPR-Based Genetic Manipulation of Candida Species: Historical Perspectives and Current Approaches. Front. Genome Ed. 2021, 2, 606281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alani, E.; Cao, L.; Kleckner, N. A Method for Gene Disruption That Allows Repeated Use of URA3 Selection in the Construction of Multiply Disrupted Yeast Strains. Genetics 1987, 116, 541–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lay, J.; Henry, L.K.; Clifford, J.; Koltin, Y.; Bulawa, C.E.; Becker, J.M. Altered Expression of Selectable Marker URA3 in Gene-Disrupted Candida albicans Strains Complicates Interpretation of Virulence Studies. Infect. Immun. 1998, 66, 5301–5306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, M.G.; O’Connor, J.-E.; García, L.L.; Martínez, S.I.; Herrero, E.; Agudo, L.D.C. Isolation of a Candida albicans Gene, Tightly Linked toURA3, Coding for a Putative Transcription Factor That Suppresses a Saccharomyces Cerevisiaeaft1 Mutation. Yeast 2001, 18, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morschhäuser, J.; Michel, S.; Staib, P. Sequential Gene Disruption in Candida albicans by FLP-mediated Site-specific Recombination. Mol. Microbiol. 1999, 32, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennison, P.M.J.; Ramsdale, M.; Manson, C.L.; Brown, A.J.P. Gene Disruption in Candida albicans Using a Synthetic, Codon-Optimised Cre-loxP System. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2005, 42, 737–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enloe, B.; Diamond, A.; Mitchell, A.P. A Single-Transformation Gene Function Test in Diploid Candida albicans. J. Bacteriol. 2000, 182, 5730–5736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirsching, S.; Michel, S.; Köhler, G.; Morschhäuser, J. Activation of the Multiple Drug Resistance Gene MDR1 in Fluconazole-Resistant, Clinical Candida albicans Strains Is Caused by Mutations in a Trans-Regulatory Factor. J. Bacteriol. 2000, 182, 400–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuß, O.; Vik, Å.; Kolter, R.; Morschhäuser, J. The SAT1 Flipper, an Optimized Tool for Gene Disruption in Candida albicans. Gene 2004, 341, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Guo, W.; Köhler, J.R. CaNAT1, a Heterologous Dominant Selectable Marker for Transformation of Candida albicans and Other Pathogenic Candida Species. Infect. Immun. 2005, 73, 1239–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roemer, T.; Jiang, B.; Davison, J.; Ketela, T.; Veillette, K.; Breton, A.; Tandia, F.; Linteau, A.; Sillaots, S.; Marta, C.; et al. Large-scale Essential Gene Identification in Candida albicans and Applications to Antifungal Drug Discovery. Mol. Microbiol. 2003, 50, 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Meara, T.R.; Veri, A.O.; Ketela, T.; Jiang, B.; Roemer, T.; Cowen, L.E. Global Analysis of Fungal Morphology Exposes Mechanisms of Host Cell Escape. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, S.M.; French, S.; Kohn, L.A.; Chen, V.; Johnson, A.D. Systematic Screens of a Candida albicans Homozygous Deletion Library Decouple Morphogenetic Switching and Pathogenicity. Nat. Genet. 2010, 42, 590–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinek, M.; Chylinski, K.; Fonfara, I.; Hauer, M.; Doudna, J.A.; Charpentier, E. A Programmable Dual-RNA–Guided DNA Endonuclease in Adaptive Bacterial Immunity. Science 2012, 337, 816–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Martínez, J.; Maldonado, R.D.; Guzmán, N.M.; Mojica, F.J.M. The CRISPR Conundrum: Evolve and Maybe Die, or Survive and Risk Stagnation. Microb. Cell 2018, 5, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marraffini, L.A.; Sontheimer, E.J. Self versus Non-Self Discrimination during CRISPR RNA-Directed Immunity. Nature 2010, 463, 568–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, A.A.; Lim, W.A.; Qi, L.S. Beyond Editing: Repurposing CRISPR–Cas9 for Precision Genome Regulation and Interrogation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2016, 17, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanraju, P.; Makarova, K.S.; Zetsche, B.; Zhang, F.; Koonin, E.V.; Van Der Oost, J. Diverse Evolutionary Roots and Mechanistic Variations of the CRISPR-Cas Systems. Science 2016, 353, aad5147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Russa, M.F.; Qi, L.S. The New State of the Art: Cas9 for Gene Activation and Repression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2015, 35, 3800–3809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sander, J.D.; Joung, J.K. CRISPR-Cas Systems for Editing, Regulating and Targeting Genomes. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014, 32, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruyama, T.; Dougan, S.K.; Truttmann, M.C.; Bilate, A.M.; Ingram, J.R.; Ploegh, H.L. Erratum: Corrigendum: Increasing the Efficiency of Precise Genome Editing with CRISPR-Cas9 by Inhibition of Nonhomologous End Joining. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016, 34, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapiro, R.S.; Chavez, A.; Collins, J.J. CRISPR-Based Genomic Tools for the Manipulation of Genetically Intractable Microorganisms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Román, E.; Coman, I.; Prieto, D.; Alonso-Monge, R.; Pla, J. Implementation of a CRISPR-Based System for Gene Regulation in Candida albicans. mSphere 2019, 4, e00001-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morio, F.; Lombardi, L.; Butler, G. The CRISPR Toolbox in Medical Mycology: State of the Art and Perspectives. PLoS Pathog 2020, 16, e1008201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vyas, V.K.; Barrasa, M.I.; Fink, G.R. A Candida albicans CRISPR System Permits Genetic Engineering of Essential Genes and Gene Families. Sci. Adv. 2015, 1, e1500248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, K.; Ichikawa, Y.; Woolford, C.A.; Mitchell, A.P. Candida albicans Gene Deletion with a Transient CRISPR-Cas9 System. mSphere 2016, 1, e00130-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.Y.; Cravener, M.V.; Mitchell, A.P. Targeted Genetic Changes in Candida albicans Using Transient CRISPR-Cas9 Expression. Curr. Protoc. 2021, 1, e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Wei, J.J.; Sabatini, D.M.; Lander, E.S. Genetic Screens in Human Cells Using the CRISPR-Cas9 System. Science 2014, 343, 80–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.Y.; Mitchell, A.P. Marker Recycling in Candida albicans through CRISPR-Cas9-Induced Marker Excision. mSphere 2017, 2, e00050-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.; Quail, M.M.F.; Hernday, A.D. An Efficient, Rapid, and Recyclable System for CRISPR-Mediated Genome Editing in Candida albicans. mSphere 2017, 2, e00149-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, J.; O’Connor-Moneley, J.; Frawley, D.; Flanagan, P.R.; Alaalm, L.; Menendez-Manjon, P.; Estevez, S.V.; Hendricks, S.; Woodruff, A.L.; Buscaino, A.; et al. Deletion of the Candida albicans TLO Gene Family Using CRISPR-Cas9 Mutagenesis Allows Characterisation of Functional Differences in α-, β- and γ- TLO Gene Function. PLoS Genet. 2023, 19, e1011082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, R.S.; Chavez, A.; Porter, C.B.M.; Hamblin, M.; Kaas, C.S.; DiCarlo, J.E.; Zeng, G.; Xu, X.; Revtovich, A.V.; Kirienko, N.V.; et al. A CRISPR–Cas9-Based Gene Drive Platform for Genetic Interaction Analysis in Candida albicans. Nat. Microbiol. 2017, 3, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickman, M.A.; Zeng, G.; Forche, A.; Hirakawa, M.P.; Abbey, D.; Harrison, B.D.; Wang, Y.-M.; Su, C.; Bennett, R.J.; Wang, Y.; et al. The ‘Obligate Diploid’ Candida albicans Forms Mating-Competent Haploids. Nature 2013, 494, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halder, V.; Porter, C.B.M.; Chavez, A.; Shapiro, R.S. Design, Execution, and Analysis of CRISPR–Cas9-Based Deletions and Genetic Interaction Networks in the Fungal Pathogen Candida albicans. Nat. Protoc. 2019, 14, 955–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halder, V.; McDonnell, B.; Uthayakumar, D.; Usher, J.; Shapiro, R.S. Genetic Interaction Analysis in Microbial Pathogens: Unravelling Networks of Pathogenesis, Antimicrobial Susceptibility and Host Interactions. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2021, 45, fuaa055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seher, T.D.; Nguyen, N.; Ramos, D.; Bapat, P.; Nobile, C.J.; Sindi, S.S.; Hernday, A.D. AddTag, a Two-Step Approach with Supporting Software Package That Facilitates CRISPR/Cas-Mediated Precision Genome Editing. G3 Genes|Genomes|Genet. 2021, 11, jkab216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.S.; Larson, M.H.; Gilbert, L.A.; Doudna, J.A.; Weissman, J.S.; Arkin, A.P.; Lim, W.A. Repurposing CRISPR as an RNA-Guided Platform for Sequence-Specific Control of Gene Expression. Cell 2013, 152, 1173–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maeder, M.L.; Linder, S.J.; Cascio, V.M.; Fu, Y.; Ho, Q.H.; Joung, J.K. CRISPR RNA–Guided Activation of Endogenous Human Genes. Nat. Methods 2013, 10, 977–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wensing, L.; Sharma, J.; Uthayakumar, D.; Proteau, Y.; Chavez, A.; Shapiro, R.S. A CRISPR Interference Platform for Efficient Genetic Repression in Candida albicans. mSphere 2019, 4, e00002-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wensing, L.; Shapiro, R.S. Design and Generation of a CRISPR Interference System for Genetic Repression and Essential Gene Analysis in the Fungal Pathogen Candida albicans. In Essential Genes and Genomes; Zhang, R., Ed.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2022; Volume 2377, pp. 69–88. [Google Scholar]

- Cowen, L.E.; Lindquist, S. Hsp90 Potentiates the Rapid Evolution of New Traits: Drug Resistance in Diverse Fungi. Science 2005, 309, 2185–2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gervais, N.C.; La Bella, A.A.; Wensing, L.F.; Sharma, J.; Acquaviva, V.; Best, M.; Cadena López, R.O.; Fogal, M.; Uthayakumar, D.; Chavez, A.; et al. Development and Applications of a CRISPR Activation System for Facile Genetic Overexpression in Candida albicans. G3 Genes|Genomes|Genet. 2023, 13, jkac301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chavez, A.; Scheiman, J.; Vora, S.; Pruitt, B.W.; Tuttle, M.; P R Iyer, E.; Lin, S.; Kiani, S.; Guzman, C.D.; Wiegand, D.J.; et al. Highly Efficient Cas9-Mediated Transcriptional Programming. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 326–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, L.A.; Horlbeck, M.A.; Adamson, B.; Villalta, J.E.; Chen, Y.; Whitehead, E.H.; Guimaraes, C.; Panning, B.; Ploegh, H.L.; Bassik, M.C.; et al. Genome-Scale CRISPR-Mediated Control of Gene Repression and Activation. Cell 2014, 159, 647–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konermann, S.; Brigham, M.D.; Trevino, A.E.; Joung, J.; Abudayyeh, O.O.; Barcena, C.; Hsu, P.D.; Habib, N.; Gootenberg, J.S.; Nishimasu, H.; et al. Genome-Scale Transcriptional Activation by an Engineered CRISPR-Cas9 Complex. Nature 2015, 517, 583–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horlbeck, M.A.; Gilbert, L.A.; Villalta, J.E.; Adamson, B.; Pak, R.A.; Chen, Y.; Fields, A.P.; Park, C.Y.; Corn, J.E.; Kampmann, M.; et al. Compact and Highly Active Next-Generation Libraries for CRISPR-Mediated Gene Repression and Activation. eLife 2016, 5, e19760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joung, J.; Engreitz, J.M.; Konermann, S.; Abudayyeh, O.O.; Verdine, V.K.; Aguet, F.; Gootenberg, J.S.; Sanjana, N.E.; Wright, J.B.; Fulco, C.P.; et al. Genome-Scale Activation Screen Identifies a lncRNA Locus Regulating a Gene Neighbourhood. Nature 2017, 548, 343–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Jiang, Q.; Yang, F.; Wu, Q.; Lyu, T.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, J.; Li, F.; Xu, D. Establishment and Optimization of a System for the Detection of Candida albicans Based on Enzymatic Recombinase Amplification and CRISPR/Cas12a System. Microbiol. Spectr. 2025, 13, e00268-25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Ji, W.; Jiang, M.; Shen, J. CRISPR Technology Combined with Isothermal Amplification Methods for the Diagnosis of Candida albicans Infection. Clin. Chim. Acta 2025, 567, 120106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, H.; Dean, N. Dramatic Improvement of CRISPR/Cas9 Editing in Candida albicans by Increased Single Guide RNA Expression. mSphere 2017, 2, e00385-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyas, V.K.; Bushkin, G.G.; Bernstein, D.A.; Getz, M.A.; Sewastianik, M.; Barrasa, M.I.; Bartel, D.P.; Fink, G.R. New CRISPR Mutagenesis Strategies Reveal Variation in Repair Mechanisms among Fungi. mSphere 2018, 3, e00154-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grahl, N.; Demers, E.G.; Crocker, A.W.; Hogan, D.A. Use of RNA-Protein Complexes for Genome Editing in Non-albicans Candida Species. mSphere 2017, 2, e00218-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blázquez-Muñoz, M.T.; Costa-Barbosa, A.; Alvarado, M.; Mendonça, A.; Benkhellat, S.; Vilanova, M.; Fernández-Sánchez, S.; Correia, A.; De Groot, P.W.J.; Sampaio, P. Loss of CHT3 in Candida albicans Wild-Type Strains Increases Surface-Exposed Chitin and Affects Host-Pathogen Interaction. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1654710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enkler, L.; Richer, D.; Marchand, A.L.; Ferrandon, D.; Jossinet, F. Genome Engineering in the Yeast Pathogen Candida glabrata Using the CRISPR-Cas9 System. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 35766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroc, L.; Fairhead, C. A New Inducible CRISPR-Cas9 System Useful for Genome Editing and Study of Double-strand Break Repair in Candida glabrata. Yeast 2019, 36, 723–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Métivier, K.; Zhou-Li, Y.; Fairhead, C. In Vivo CRISPR-Cas9 Expression in Candida glabrata, Candida bracarensis, and Candida nivariensis: A Versatile Tool to Study Chromosomal Break Repair. Yeast 2024, 41, 560–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroc, L.; Shaker, H.; Shapiro, R.S. Functional Genetic Characterization of Stress Tolerance and Biofilm Formation in Nakaseomyces (Candida) glabrata via a Novel CRISPR Activation System. mSphere 2024, 9, e00761-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norton, E.L.; Sherwood, R.K.; Bennett, R.J. Development of a CRISPR-Cas9 System for Efficient Genome Editing of Candida lusitaniae. mSphere 2017, 2, e00217-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, L.; Turner, S.A.; Zhao, F.; Butler, G. Gene Editing in Clinical Isolates of Candida parapsilosis Using CRISPR/Cas9. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 8051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]