Abstract

Jasmonate ZIM-domain (JAZ) family genes, which belong to TIFY family, are plant-specific transcriptional repressors. As key regulators of the jasmonic acid signaling pathway, JAZ proteins play crucial roles in various aspects of plant biology. However, the identification and functional characterization of JAZ genes in sweet cherry (Prunus avium L.) fruit remain unknown. In the present study, we identified nine JAZ members in the sweet cherry genome. We systematically analyzed the gene structures, protein domains, evolutionary relationships, and physicochemical properties of these members and also evaluated their expression levels across different fruit developmental stages, as well as under methyl jasmonate (MeJA) treatment. Among these members, our results revealed a previously uncharacterized JAZ member, PavJAZ8, as a crucial regulator of fruit aroma traits. Specifically, RT-qPCR analysis showed that PavJAZ8 overexpression modulates the expression of genes involved in the biosynthesis of aroma volatiles, such as PavLOX2, PavLOX3, PavHPL1, PavADH1.1, PavADH1.2, and PavADH7, which are involved in the synthesis of aldehydes and alcohols. Consistent with the gene expression data, analysis of volatile metabolites revealed that PavJAZ8 overexpression significantly inhibited the accumulation of several related aldehydes and alcohols, including hexanal, geraniol, and benzyl alcohol. Furthermore, PavJAZ8 expression was highly responsive to phytohormone treatments, such as abscisic acid (ABA) and MeJA. Further analysis showed that PavJAZ8 interacts with PavMYC2, thereby mediating JA signal transduction. Our results highlight PavJAZ8 as a novel regulator of fruit aroma quality, offering a valuable genetic target for sweet cherry improvement.

1. Introduction

Sweet cherry (Prunus avium L.) is an important fruit worldwide due to its favorable flavor, rich nutrition and high commercial interest [1,2]. As non-climacteric fruits, sweet cherries exhibit complex regulatory mechanisms governing ripening and quality formation [3,4], which are jointly regulated by various phytohormones, including abscisic acid (ABA), auxin (IAA), and gibberellins (GAs) [5,6,7,8,9]. In recent years, increasing evidence suggests that jasmonates (JAs) also play important roles in the ripening and quality formation of non-climacteric fruits [10,11,12,13,14]. This is supported by observations that jasmonic acid (JA) content increases during fruit ripening [15] and that exogenous treatment with JAs can significantly accelerate fruit ripening and flavor formation [10,13]. Consistently, a number of studies have demonstrated that the application of JAs promotes the accumulation of a variety of aroma compounds [16] and quality-associated compounds, such as anthocyanins [17,18]. Furthermore, JA-mediated crosstalk with other hormones, including salicylic acid (SA) and ethylene, modulates defense responses that are intrinsically linked to fruit quality [19].

The role of JA in fruit ripening and flavor formation is further exemplified in sweet cherry, with JA content in the exocarp increasing during early fruit development and remaining stable until harvest, suggesting a role for JA in promoting ripening [20]. Kondo et al. (2002) demonstrated that JA concentration may influence ABA levels, and endogenous JA could also regulate cell division during fruit development [21]. Additionally, a recent study showed that exogenous methyl jasmonate (MeJA) application at the fruit set stage alters the wax composition of ripe sweet cherry cuticles, particularly by enhancing alkane biosynthesis [22]. As alkanes are major components of the cuticular wax, this enhancement likely fortifies the cuticle—a key barrier crucial for limiting water loss, defending against pathogens, and maintaining fruit firmness and appearance, thereby directly contributing to improved fruit quality.

The JA signaling cascade comprises several critical components: the F-box subunit of the SCF-COI1 ubiquitin ligase, known as CORONATINE-INSENSITIVE1 (COI1) [23]; the JASMONATE-ZIM DOMAIN (JAZ) protein repressors [24,25,26]; and the basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors (MYC) [27]. The bioactive jasmonate ligand, (3R,7S)-jasmonoyl-L-isoleucine (JA-Ile) [28], binds to COI1, triggering JAZ protein degradation via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. This releases MYC2 and other transcription factors from repression, leading to the activation of JA-responsive genes [25,26,27,29].

JAZ family proteins are plant-specific transcriptional repressors belonging to the TIFY family. Studies have identified 13 JAZ genes in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) [24], 16 in maize (Zea mays) [30], and 26 in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) [31]. As core components of the JA signaling cascade, JAZ proteins have been increasingly studied for their roles in fruit ripening and quality formation. A study in strawberry (Fragaria vesca) reported that expression levels exhibited a significant decrease from fruit development to ripening stages, suggesting that FveJAZs may be important factors regulating fruit ripening [32]. Similarly, in strawberry fruits, Wang et al. [33] found that FveJAZ12 can mediate the transduction of JA signaling through a COI1-independent pathway, regulating fruit quality traits, particularly aroma compound metabolism. In kiwifruit (Actinidia chinensis), AchJAZ9 expression increased gradually during fruit ripening, while AchJAZ3 and AchJAZ11 were highly expressed in the ripening stage. The diversity of expression patterns during fruit ripening suggests that these AchJAZs may play different roles [34]. In apple (Malus domestica), Hu Y et al. [35] showed that MdoJAZ is a core JA signaling hub protein that affects ethylene signaling pathways, and suppressing MdoJAZ expression promotes apple ripening and fruit trait development.

Although the JAZ gene family has been identified in various horticultural crops [31,32,36,37,38,39], a systematic characterization in sweet cherry is lacking. To address this gap, we identified nine PavJAZ family members in sweet cherry, and subsequently analyzed their protein structure, conserved domains, chromosome locations, and other features. We also investigated their stage-specific expression patterns and responses to MeJA. Among them, we uncovered a previously uncharacterized JAZ gene, PavJAZ8, which is highly expressed throughout all fruit stages. Its transcription can be significantly modulated by both MeJA and ABA treatments. PavJAZ8 physically interacts with PavMYC2. Furthermore, functional evidence indicates that PavJAZ8 regulates fruit aroma quality. Transient overexpression of PavJAZ8 altered the levels of key green and fruity volatiles, such as (E)-2-hexenal and geraniol. Consistent with this phenotypic change, it modulated the expression of critical biosynthetic genes, including PavHPL1, PavLOXs, and PavADHs. These results provide a basis for further research on the role of JAZ proteins in sweet cherry fruit ripening and trait development.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Phytohormone Treatments

Sweet cherry (Prunus avium L.) cv ‘Tieton’ was grown in the Beijing Academy of Agriculture and Forestry Sciences, Beijing, China. For PavJAZs gene expression analysis, fruit samples were classified into six developmental stages, including the Small Green (SG, 1–2 weeks after flowering), Middle Green (MG, 3–4 weeks after flowering), Large Green (LG, 5 weeks after flowering), Turning (T, 6 weeks after flowering), Initial Red (IR, 7–8 weeks after flowering), and Full Red (FR, 9 weeks after flowering) stages.

Phytohormone treatments were applied to fruits at the LG stage. Fruits with uniform sizes and normal shape were harvested and treated by vacuum infiltration with 100 μM MeJA, 100 μM ABA, 100 μM GA3, 100 μM SA, with distilled water as the control. At predetermined time points, fruits were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C for subsequent molecular analyses. The experiment included three biological replicates, with 10 fruits per treatment in each replicate.

2.2. Identification and Classification of JAZ Gene Family in Sweet Cherry

The JAZ gene family of Arabidopsis was retrieved from the TAIR database (https://www.arabidopsis.org/). These accession numbers are provided in Table S1. Using the Arabidopsis JAZ protein sequences as queries, homologous JAZ family genes were identified in sweet cherry. The Prunus avium Tieton Genome v2.0 [40] sequences were downloaded from the Genome Database for Rosaceae (https://www.rosaceae.org/). Accession numbers for each of the identified PavJAZs are listed in Table S1. Physicochemical properties of PavJAZs, including theoretical isoelectric point and molecular weight, were predicted using the ExPASy Proteomics Server (https://web.expasy.org).

2.3. Chromosomal Location and Phylogenetic Analysis of PavJAZs

Chromosomal localization of PavJAZs was obtained based on Prunus avium cv. Tieton v2.0 genome annotation information. Subsequently, TBtools v0.66836 [41] was used to map and visualize chromosome distributions. Intra- and inter-species PavJAZs collinearity analyses were performed using TBTools. Non-synonymous substitution rate (Ka) and synonymous substitution rate (Ks) were calculated using KaKs_Calculator 2.0 [42].

Using the Arabidopsis JAZ protein sequences as queries, homologous JAZ family genes were identified in sweet cherry (Prunus avium Tieton Genome v2.0), apricot (Prunus armeniaca Yinxiangbai v1.0) [43], peach (Prunus persica Zhongyoutao 14 Genome v1.0) [44], strawberry (Fragaria vesca Genome v4.0.a2) [45], and tomato (SL4.0 build with ITAG4.0 annotation) [46] using BLAST v2.2.28+. The presence of the conserved domain in candidate proteins was verified with the NCBI Batch Web CD-Search Tool (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/bwrpsb/bwrpsb.cgi, accessed on 20 May 2025) with default parameters. Subsequently, a phylogenetic analysis was conducted using the JAZ protein sequences from these six species. A multiple sequence alignment was generated using MUSCLE v3.8.425 with default settings, and low-quality regions were filtered using trimAl v1.4.rev15. The trimmed alignments were used to construct a maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree with IQ-TREE v1.6.7. The best-fitting model determined by ModelFinder was Q.plant + I+G4. Branch support was assessed with 1000 bootstrap replicates.

2.4. Structural and Domain Analysis of PavJAZs

Protein sequence alignments of PavJAZs were performed using Clustal X 2.1 [47] and visualized with Jalview [48]. Gene structure diagrams were generated using Gene Structure Display Server (GSDS) 2.0 (http://gsds.gao-lab.org/). Protein domains were identified using the Pfam database (http://pfam.xfam.org/), and sequence logos of the TIFY and JAS domains were generated using WebLogo (http://weblogo.berkeley.edu/logo.cgi, accessed on 20 May 2025).

2.5. RNA Extraction and Quantitative Real-Time PCR (RT-qPCR) Analysis

RNA extraction and RT-qPCR were performed as previously described [49]. Briefly, total RNA was extracted from fruit samples using the Plant RNA Kit (Omega, Norcross, GA, USA, R6827-01). First-strand cDNA was synthesized using the HiScript II 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (+gDNA wiper) (Vazyme, Nanjing, China, R212-01) following the manufacturer’s protocol. RT-qPCR was performed on a QuantStudio 6 Flex Real-time PCR system using ChamQ SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Vazyme, Nanjing, China, Q311-02). The RT-qPCR data were analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCt method for calculating relative gene expression, with PavACTIN serving as the internal reference gene. Gene-specific primers are listed in Table S2.

2.6. Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry Analysis of Volatile Metabolites

Sweet cherry fruit samples were immediately frozen using liquid nitrogen and subsequently subjected to gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS). VOC desorption from the SPME Arrow fiber was performed in an GC injector at 250 °C for 5 min. Separation and detection of volatile compounds were conducted using an Agilent 8890 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) GC system coupled with a 7000E mass spectrometer. A DB-5MS capillary column was employed for chromatographic separation, with helium as the carrier gas maintained at a constant flow rate of 1.2 mL/min. The oven temperature program started at 40 °C, followed by a ramp of 10 °C/min to 100 °C, then 7 °C/min to 180 °C, and finally 25 °C/min to 280 °C, with a final hold time of 5 min. MS detection was performed in electron ionization mode at 70 eV. The temperatures of the quadrupole, ion source, and transfer line were set to 150 °C, 230 °C, and 280 °C, respectively. Analytes were identified and quantified using selected ion monitoring mode.

2.7. Transient Fruit Transformation

Transient transformation assays in sweet cherry fruits were performed using Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated infiltration, following an established protocol [50] with modifications. Fruits at the LG developmental stage were selected for transformation. The coding sequences of PavJAZ8 were cloned and inserted into the pSuper1300-GFP vector. The GV3101 Agrobacterium strains carrying pSuper1300-PavJAZ8-GFP or pSuper1300-GFP vectors were cultivated to an optical density (OD) of 0.8 at 600 nm (OD600), followed by infiltration into the fruits.

2.8. Subcellular Localization Analysis

The subcellular localization of the PavJAZs was predicted by the online web-servers tool Cell-PLoc 2.0 [51] and WoLF PSORT (https://wolfpsort.hgc.jp/). For experimental validation, the coding sequence of PavJAZ8 was cloned into the pSuper1300-GFP vector to generate a C-terminal green fluorescent protein (GFP) fusion. The recombinant Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 was cultivated to an OD600 of 0.6–0.8, and then infiltrated into leaves of transgenic N. benthamiana plants expressing a nuclear-localized mCherry marker to achieve transient transformation [52]. After 2–3 days, subcellular localization was analyzed with a Zeiss LSM 710 confocal microscope. Samples were excited with a 488 nm argon laser. The emitted fluorescence was collected within a spectral window of 500–550 nm.

2.9. Bimolecular Fluorescence Complementation

To investigate protein–protein interaction between PavJAZ8 and PavMYC2, the bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) assays were performed using the pSPYNE-35S and pSPYCE-35S vectors [53]. The vectors were transiently expressed in N. benthamiana leaves via agroinfiltration using Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 [52]. After 2–3 days, fluorescent signal was visualized with a Zeiss LSM 710 confocal microscope. Samples were excited with a 488 nm argon laser line. The emitted fluorescence was collected within a spectral window of 500–550 nm.

2.10. GST Pull-Down Assay

A GST pull-down assay was performed to test for a direct physical interaction between PavJAZ8 and PavMYC2.

Protein Expression and purification: The coding sequences of PavJAZ8 and PavMYC2 were cloned into the pGEX-4T-2 and pET-30a vectors, respectively. The recombinant plasmids were transformed into E. coli strain BL21 (DE3). For protein expression, cultures were grown at 37 °C to an OD600 of 0.6–0.8. Expression was induced by adding 1 mM isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside, followed by incubation at 16 °C for 12 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and lysed by sonication on ice. The HIS-tagged PavMYC2 protein was purified from the soluble fraction using Ni-NTA agarose beads. The beads were incubated with the lysate for 1 h at 4 °C, then washed extensively with a wash buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole). Bound proteins were eluted with an elution buffer containing 250 mM imidazole. The GST-tagged PavJAZ8 was purified under similar conditions using Glutathione Sepharose 4B beads.

Pull-down Assay: For the pull-down assay, purified PavJAZ8-GST (experimental group) or GST alone (negative control) was immobilized on Glutathione Sepharose 4B beads. The beads were then incubated with an equal amount of purified PavMYC2-HIS protein for 2 h at 4 °C with gentle rotation. After incubation, the beads were washed three times with ice-cold PBS buffer to remove non-specifically bound proteins. Protein interactions were analyzed by immunoblotting using Anti-GST (Abclonal, Wuhan, China, AE001, 1:5000) and Anti-HIS (Abclonal, Wuhan, China, AE003, 1:5000) antibodies to detect the bait (PavJAZ8-GST) and prey (PavMYC2-HIS) proteins, respectively.

3. Results

3.1. Identification and Classification of the PavJAZ Genes

Nine putative PavJAZs were identified by blast (BLAST v2.2.28+) with JAZ gene sequences in Arabidopsis and further validated for the presence of structural domains using the NCBI Batch Web CD-search tool with default parameters. These members were classified and named according to the chromosomal locations of the genes.

Physicochemical analysis showed that the encoded PavJAZ family members ranged from 124 to 377 amino acids (aa), with coding sequence (CDS) lengths of 375–1134 base pairs (bp). The theoretical molecular weights (MW) of these proteins were calculated to be in the range of 14.66–40.40 kDa, and the predicted isoelectric points (pI) ranged from 6.18 to 9.80. Notably, most PavJAZ proteins exhibited an isoelectric point above 8.5, except PavJAZ8, which had an isoelectric point of 6.18. The grand average of hydropathicity (GRAVY) index for all PavJAZs was negative, indicating their hydrophilic nature. Additionally, all proteins were predicted as unstable, with instability index values exceeding 40 (Table 1). This inherent instability is consistent with their canonical role as repressors in the jasmonate signaling pathway, which are rapidly degraded by the proteasome following hormone perception. This finding is also in agreement with the unstable nature of JAZ proteins reported in other plant species [25,26,29], further supporting that rapid turnover is a conserved characteristic of this protein family.

Table 1.

Basic physicochemical characteristics of PavJAZs.

3.2. Chromosomal Locations and Collinearity Analysis of PavJAZs

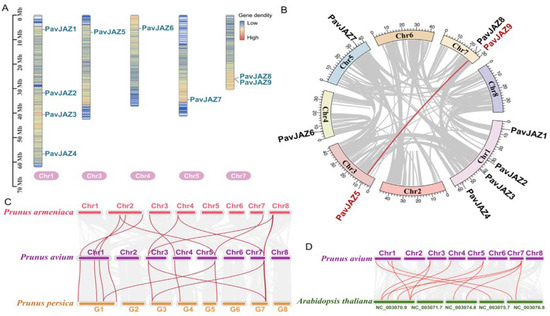

The PavJAZ genes were unevenly distributed across 5 out of the 8 sweet cherry chromosomes. As shown in Figure 1A, Chromosomes 1 and 7 harbor 4 and 2 PavJAZ genes, respectively. Chromosomes 3, 4, and 5 each contain 1 PavJAZ gene. No PavJAZ genes were mapped to chromosomes 2, 6, or 8.

Figure 1.

Chromosomal distribution and collinearity analysis of PavJAZs. (A) Chromosomal distribution of PavJAZ genes in sweet cherry. (B) Intra-genomic synteny of PavJAZ genes in sweet cherry. The only duplicated pair (PavJAZ5/PavJAZ9, connected by red line) suggests a segmental duplication event. (C,D) Collinearity analysis of JAZ genes in Prunus species (sweet cherry, peach, and apricot) and syntenic relationships between sweet cherry and Arabidopsis JAZ genes. Red lines indicate gene pairs that are collinear with JAZ genes.

To investigate PavJAZ genes duplication events within the sweet cherry genome, we performed whole-genome collinearity analysis and identified only one duplicated PavJAZ pair (PavJAZ5 and PavJAZ9) (Figure 1B), suggesting that these two JAZ genes are derived from a common ancestral gene via segmental duplication. Evolutionary selection pressure analysis revealed that the Ka/Ks ratio values < 1 for this gene pair (Table 2), indicating strong purifying selection acting on this gene pair. To further investigate conserved syntenic relationships across Prunus species, we conducted whole-genome synteny analysis between sweet cherry, peach, and apricot. Genomic synteny analysis showed a high degree of conservation between sweet cherry and its close relatives, peach and apricot (Figure 1C), indicating strong chromosomal stability within the Prunus genus (Rosaceae). Notably, compared to peach, sweet cherry and apricot exhibited more chromosomal rearrangements, and some JAZ genes were located within these rearranged genomic regions. In addition, synteny analysis between sweet cherry and Arabidopsis revealed extensive genomic divergence, while the JAZ gene structure remained relatively conserved (Figure 1D).

Table 2.

Calculation of Ka/Ks of PavJAZs.

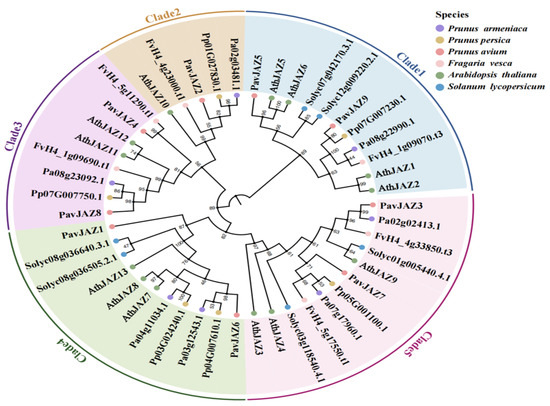

3.3. Phylogenetic Analysis of JAZs

To elucidate the evolutionary relationship of JAZ genes among plant species, we analyzed 47 JAZ protein sequences from six species, including nine from sweet cherry, 13 from Arabidopsis, six from tomato, six from strawberry, six from peach, and seven from apricot (Figure 2). The number of JAZ genes in sweet cherry did not differ significantly from those in peach and apricot, but there was a significant contraction compared with Arabidopsis. Maximum likelihood phylogenetic trees showed that PavJAZs were closely clustered with the immediate homologues of related species (Figure 2), suggesting that JAZ genes are highly evolutionarily conserved.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of JAZ proteins in six species. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using 47 JAZ protein sequences from Arabidopsis, strawberry, tomato, apricot, peach, and sweet cherry.

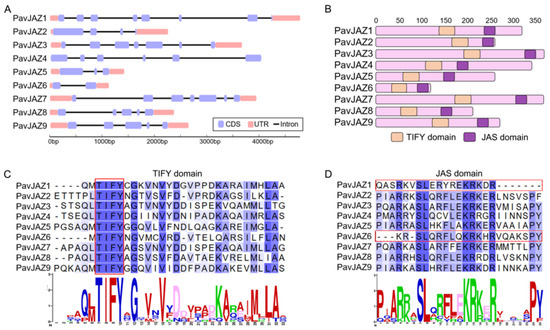

3.4. Protein Structure, Conserved Domains Analysis of PavJAZs

Gene structure analysis showed that PavJAZs exhibit differences in exon-intron architecture, with the number of exons ranging from 3 to 8 (Figure 3A). Our results revealed strong conservation across PavJAZs domains (Figure 3B): the TIFY motif within the TIFY domain, which mediates interactions with the NINJA adapter and facilitates JAZ homo- and hetero-dimerization, was completely identical among all members (Figure 3C), while most of the PavJAZs contained a conserved JAS domain exhibiting the SLX2FX2KRX2RX5PY motif, which is critical for JA signal transduction (Figure 3D).

Figure 3.

Gene and protein structures including conserved domain analysis of PavJAZs. (A) Exon-intron structure of PavJAZ genes. (B) PavJAZ proteins contain the conserved TIFY and JAS domains. (C) Sequence alignment of the TIFY domains in PavJAZ proteins. (D) Sequence alignment of the JAS domains in PavJAZ proteins.

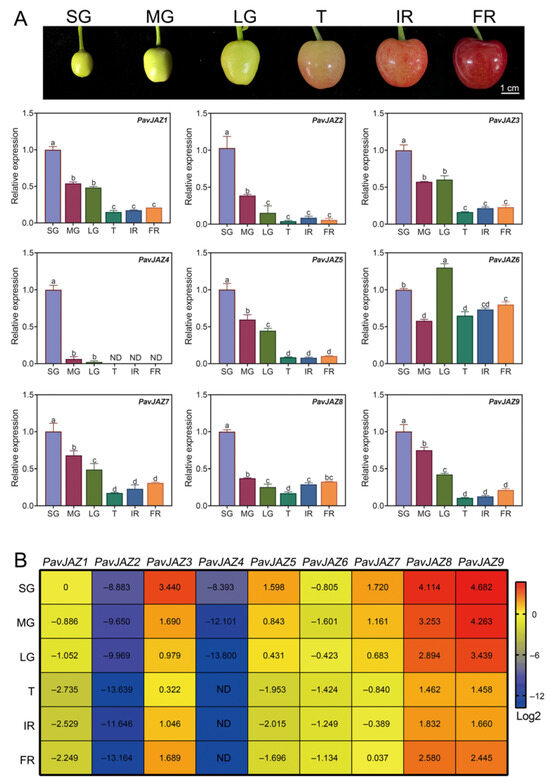

3.5. Expression Analysis of the PavJAZs in Different Fruit Stages

To investigate the expression patterns of PavJAZ genes, we analyzed their expression patterns in different fruit stages. As shown in Figure 4A, PavJAZ1, PavJAZ2, PavJAZ3, PavJAZ7, PavJAZ8, and PavJAZ9 exhibited similar expression trends, with downregulation expression prior to the T stage, followed by a gradual increase in their level of expression during ripening. The expression pattern of PavJAZ6 differed across all stages. Notably, PavJAZ8, and PavJAZ9 displayed higher expression levels compared to other PavJAZ members in every developmental stage, and their expression profiles showed more dynamic changes during fruit ripening (Figure 4B). In contrast, PavJAZ2 and PavJAZ4 showed low expression levels in all stages, indicating their limited functional relevance to ripening. These differential expression patterns suggest distinct roles of PavJAZ members in fruit ripening processes.

Figure 4.

Relative expression analysis of PavJAZs in different fruit stages. (A) RT-qPCR analysis of PavJAZ genes expression levels in different fruit stages. Values represent the mean ± SD from three independent biological replicates. The comparative fruit phenotypes at distinct developmental stages are displayed in the images above. Fruit were classified into six developmental stages: Small Green (SG), Middle Green (MG), Large Green (LG), Turning (T), Initial Red (IR), and Full Red (FR) stages. Different letters indicate significant differences at p < 0.05. (B) The heatmap shows relative expression levels of PavJAZ genes, all expression data were first normalized to the housekeeping gene PavACTIN (provided in Table S1) to correct for experimental variations and then calculated as fold changes relative to the expression level of PavJAZ1 at the SG stage. “ND” denotes undetectable expression levels.

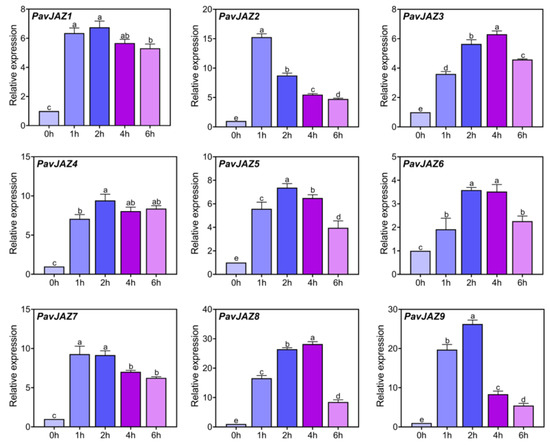

3.6. Relative Expression Levels of PavJAZs in Fruits Under MeJA Treatment

As core components of JA signaling, JAZ proteins mediate JA responses through transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation. To examine the responsiveness of PavJAZ genes to JA, developing fruits at the LG stage were treated with 100 μM MeJA. As shown in Figure 5, all PavJAZ genes displayed significant upregulation within one hour after MeJA treatment, reaching peak expression levels at 2 to 4 h post treatment. Notably, PavJAZ8 and PavJAZ9 exhibited the most pronounced and sustained induction, with the highest fold-change across multiple time points. Although their expression declined at 6 h, PavJAZ8 levels remained more than 8.46-fold higher than the baseline (0-h), while PavJAZ9 levels were 5.44-fold higher.

Figure 5.

RT-qPCR analysis of PavJAZ genes expression levels in MeJA-treated fruits. Values represent the mean ± SD from three independent biological replicates. Gene expression levels are shown relative to the 0 h time point. Different letters indicate significant differences at p < 0.05.

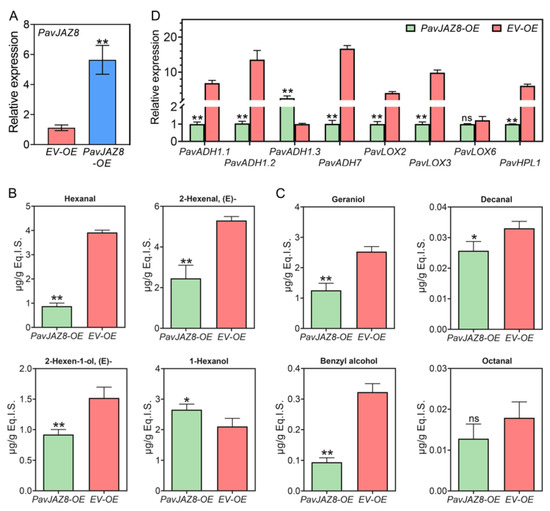

3.7. PavJAZ8 Regulates Sweet Cherry Fruit Aroma Traits

Aroma quality is a core component of the commercial value of sweet cherries. This aroma profile is derived from approximately 50 volatile compounds. These compounds range from the green, grassy aldehydes characteristic of unripe fruit to the fruity, floral esters and alcohols of ripe fruit [54,55]. This shift in volatile balance is therefore critical for aroma development during ripening, a process in which jasmonates have been shown to play a significant role [55].

During early fruit development, PavJAZ8 was the second most highly expressed PavJAZ gene, behind only PavJAZ9. However, its expression became the highest during the later ripening stages (T, IR, and FR). This high-level expression, together with its strong induction by MeJA, suggests a key role in the MeJA-mediated regulation of trait development. To further elucidate the function of PavJAZ8 during fruit aroma biosynthesis, we transiently overexpressed PavJAZ8 in LG stage fruits via Agrobacterium-mediated infiltration. Seven days after inoculation, the expression level of PavJAZ8 in OE (PavJAZ8-OE) fruits was more than fivefold higher than that in the empty vector (EV-OE) fruits, a difference that was statistically significant (Figure 6A).

Figure 6.

PavJAZ8 overexpression regulates aroma compound biosynthesis in early stage sweet cherry fruits. (A) Transient overexpression of PavJAZ8 was achieved in the fruit. (B) The contents of key green compounds differed between PavJAZ8-OE and EV-OE. (C) The contents of key fruity compounds differed between PavJAZ8-OE and EV-OE. (D) Expression levels of aroma biosynthesis-related genes in PavJAZ8-OE and EV-OE. Values represent the mean ± SD from three independent biological replicates. Asterisks denote statistically significant differences (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, ns, not significant). The corresponding gene IDs are provided in Table S1.

We analyzed the contents of eight main green and fruity compounds in sweet cherry from PavJAZ8-OE and EV-OE using GC-MS. As shown in Figure 6B, among the four key green compounds detected, the level of (E)-2-hexenal, was reduced to less than half in PavJAZ8-OE compared to EV-OE, while the levels of hexanal and (E)-2-hexen-1-ol were also significantly decreased in PavJAZ8-OE, to approximately 22.4% and 60.6% of the EV-OE levels, respectively. In contrast, the content of 1-hexanol showed an upward trend in PavJAZ8-OE. These results suggest that PavJAZ8 may suppress the emission of green fruit odors, thereby influencing flavor. Figure 6C illustrates the effect of PavJAZ8 overexpression on the relative contents of the main fruity compounds detected in sweet cherry. The relative contents of geraniol, decanal, and benzyl alcohol were also reduced in PavJAZ8-OE samples compared to EV-OE, while no significant differences were found for octanal. This dual effect suggests that PavJAZ8 directs a complex and multifaceted role in regulating fruit aroma profiles. To understand the molecular basis of these changes, RT-qPCR analysis of key aroma-related gene expression showed that the transient overexpression of PavJAZ8 altered the expression of several critical biosynthetic genes, including PavHPL1, PavLOX2, PavLOX3, PavADH1.1/1.2/1.3, and PavADH7, which are involved in the synthesis of aldehydes and alcohols (Figure 6D). Collectively, our results demonstrate that PavJAZ8 acts as a master regulator of aroma profiles in sweet cherry, modulating the production of both green and fruity volatile compounds.

3.8. Expression Patterns of PavJAZ8 After Phytohormone Treatment

Given the critical roles of phytohormones in fruit ripening and trait development, we investigated the effects of ABA, SA, and GA3 on PavJAZ8 expression in sweet cherry fruits using RT-qPCR. As shown in Figure S1. PavJAZ8 transcript levels began to increase 1 h after ABA treatment, peaked at 2 h with approximately a 10-fold upregulation, and then gradually declined. SA treatment induced a similar pattern, peaking at 2 h with a ~3-fold upregulation before returning to the baseline. In contrast, GA3 treatment resulted in a slightly different response, with PavJAZ8 expression reaching its maximum level at 4 h after GA3 treatment and then decreasing sharply. Notably, among the three hormones tested, ABA exhibited the most pronounced effect in inducing PavJAZ8 expression in fruits.

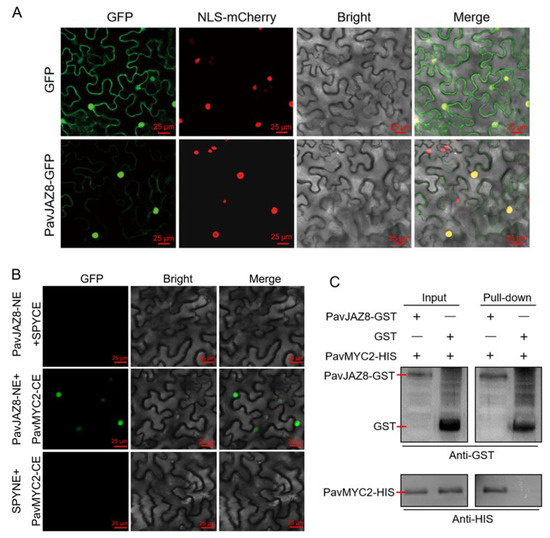

3.9. Subcellular Localization Analysis of PavJAZ8

As a transcription repressor, the JAZ protein generally functions by associating with transcription factors in the nucleus. Studies in Arabidopsis and other plant species have indicated that JAZ proteins are predominantly expressed in the nuclei, with occasional cytoplasmic localization. To determine the subcellular localization of PavJAZ proteins, we first analyzed nine PavJAZ proteins using the online prediction tools. The results revealed that all nine proteins were predicted to localize in the nucleus (Table S3).

To experimentally validate the subcellular localization of PavJAZ8, the pSuper1300-PavJAZ8-GFP construct and the empty vector were introduced into the leaves of N. benthamiana. As demonstrated in Figure 7A, the empty vector control displayed GFP expression in both the nucleus and cytoplasm, whereas the PavJAZ8-GFP fusion protein exhibited predominantly nucleus-localized expression, with cytoplasmic signals detected in only a minor subset of cells. These results support that PavJAZ8 is primarily localized in the nucleus, consistent with its predicted role in transcriptional regulation.

Figure 7.

PavJAZ8 Interacts with PavMYC2 in the nucleus. (A) Subcellular localization of PavJAZ8 was observed using confocal laser scanning microscopy, with the GFP empty vector serving as a control. Scale bar = 25 μm. (B) BiFC assay demonstrated that PavJAZ8 and PavMYC2 physically interact in the nucleus. Scale bar = 25 μm. (C) GST pull-down assay confirmed a direct physical interaction between PavJAZ8 and PavMYC2.

3.10. PavJAZ8 Interacts with the PavMYC2

Previous studies established MYC2 as a core transcription factor directly regulated by JAZ proteins in JA signaling [27,29]. Moreover, MYC2 plays a crucial role in regulating fruit ripening and quality formation in various species, including strawberry and orange (citrus sinensis) [15,33]. In sweet cherry, PavMYC2 has been identified and functionally characterized in previous studies [56]. To further elucidate the role of PavJAZ8 in fruit JA signaling, we examined the interaction of PavJAZ8 with PavMYC2. Both bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) and GST pull-down assays confirmed direct binding between PavJAZ8 and PavMYC2 (Figure 7B,C). These results demonstrate that PavJAZ8 physically interacts with PavMYC2, an interaction that strongly suggests their likely functional involvement in the JA signaling pathway in sweet cherry.

4. Discussion

As key repressors of the JA signaling pathway, the JAZ proteins play crucial roles in various aspects of plant biology, including growth, development, and stress responses [33,57,58,59,60]. However, the identity and function of each JAZ gene in sweet cherry fruit remains unknown. In this study, we identified nine JAZ family members in the sweet cherry genome, which is fewer than the number reported in the model dicot species Arabidopsis (10 members), and also fewer than those in another Rosaceae species, strawberry (12 members). Similar to that in sweet cherry, the number of JAZ family members is also relatively low in other species of the genus Prunus, such as peach (6 members) and apricot (7 members). The relatively compact size of the JAZ family in sweet cherry and other Prunus species, such as peach and apricot, contrasts with the expanded family in Arabidopsis. This discrepancy may be linked to the distinct biological traits and life histories of these species. The smaller, conserved set of JAZ proteins in Prunus might represent a core repertoire that effectively governs the JA signaling pathways essential for their perennial tree growth habit and fruit development.

The JAZ repressors share two conserved functional domains: the TIFY (ZIM) domains in the central part of the protein and the JAS domain at the C-terminus. Studies report that the TIFY domain, which contains a conserved TIFY sequence (TI (F/Y) XG), mediates the interactions with the adapter NINJA [61] and the homo-and hetero-meric interactions among JAZ proteins [62]. The JAS domain contains two conserved sequence motifs, including the LPIAR (R/K) motif and the SLX2FX2KRX2RX5PY motif. The N-terminal LPIAR (R/K) motif functions as the COI1 binding site. This peptide sequence is termed the degron and is responsible for the stability of the COI-JA-Ile-JAZ complex [25]. The SLX2FX2KRX2RX5PY motif is essential for the subcellular localization of each JAZ protein as well as the interactions with MYC2 or other target proteins [63,64]. By analyzing the domains and motifs of the identified PavJAZ members, we found that sweet cherry JAZ proteins exhibit a relatively high degree of homology with those in other species (Figure 3). The motifs within the TIFY and JAS domains are highly conserved, with minimal variations. This high level of conservation demonstrates the central importance of these domains and underscores the evolutionary and functional consistency of the JA signaling machinery across species.

The spatiotemporal expression pattern of a gene often reflects its functional relevance. In our study, PavJAZ8 exhibited consistently high expression levels in cherry fruits across all developmental stages (Figure 4B), suggesting its likely involvement throughout fruit development. Overexpression of PavJAZ8 modulated the abundance of major contributors of sweet cherry aroma metabolites, such as Hexanal, 2-Hexenal, (E)-, Geraniol, and Benzyl alcohol. Furthermore, the overexpression of PavJAZ8 significantly suppressed the expression of key aroma biosynthesis genes, including PavLOXs (aldehydes, alcohols, and esters), PavHPL (aldehydes), and PavADHs (alcohols). This directly establishes PavJAZ8 as a component of the regulatory network for aroma quality and validates its role as a regulator in aroma biosynthesis. Therefore, we identified PavJAZ8 as a key regulator of cherry fruit aroma traits. Notably, the identified functional role for PavJAZ8 mirrors that of its strawberry ortholog, FveJAZ12 (FvH4_1g09690), a known regulator of strawberry fruit trait development [33], revealing a conserved JAZ-mediated regulatory module for fruit quality traits within the Rosaceae family.

Moreover, the PavJAZ8-mediated regulation of specific volatiles, including aldehydes and terpenoids, implicates this regulatory module in the control of postharvest physiology, well beyond their contribution to aroma. These compounds can function as natural fumigants against pathogens and as signaling molecules that prime defense responses. Simultaneously, alterations in terpenoids like geraniol may influence the ethylene signaling network, directly impacting the rate of fruit senescence. Consequently, targeted manipulation of the JA pathway through PavJAZ8 emerges as a sophisticated strategy to not only refine flavor profiles but also to bolster innate defense and delay senescence, ultimately improving the postharvest quality and longevity of sweet cherry.

Notably, in addition to its distinct expression pattern and specific responsiveness to JA, PavJAZ8 is the only PavJAZ with an isoelectric point below 7.0. Since the isoelectric point of a protein influences its interactions with DNA or proteins, subcellular localization, and other biological functions, the unique pI of PavJAZ8 likely contributes to functional divergence from other PavJAZ proteins. We speculate that the acidic nature of PavJAZ8 could modulate its affinity for specific protein partners, such as the MYC transcription factors, or influence its degradation kinetics and other post-translational modifications. These distinctive features position PavJAZ8 as a high-priority candidate for future investigations into the specialized regulation of JA signaling in sweet cherry.

The MYC2 transcription factor, a direct downstream target of JAZ repressors in the JA signaling pathway, has been demonstrated to regulate fruit ripening and trait development in strawberry and orange through transcriptional activation of ripening-related genes [15,33]. To investigate whether PavMYC2 acts as a downstream component of PavJAZ8 in sweet cherry, we employed BiFC and pull-down assays, which confirmed their physical interaction. These findings not only substantiate PavJAZ8 as a functional repressor within the JA pathway but also offer deeper mechanistic insight into its role in modulating key fruit traits. By physically interacting with PavMYC2, PavJAZ8 likely tunes the expression of ripening-related genes downstream of PavMYC2, thereby integrating jasmonate signaling with fruit developmental cues.

Recent studies have demonstrated that JA engages in extensive crosstalk with hormones including SA, ethylene, GAs, and ABA via JAZ proteins, thereby regulating diverse processes from development to environmental stress and defense responses [19,35,57,60,65,66,67]. This raises a question: can the process of PavJAZ8 regulating fruit quality traits also be co-regulated by multiple hormones? Our results provide key evidence to support this hypothesis: beyond JAs, PavJAZ8 expression is significantly regulated by ABA and GA3 (Figure S1). This finding carries clear functional implications, as ABA and GA3 play well-documented, often antagonistic roles in sweet cherry fruit ripening and quality traits: ABA accelerates pericarp coloration, sugar accumulation, and softening [68,69], while GAs delay these processes by suppressing ripening-related gene expression [70,71]. The regulation of PavJAZ8 by both hormones suggests that it may act as a hormonal integrator, thereby integrating ABA and GA signals into the JA pathway to avoid premature or delayed ripening. This regulatory mechanism is consistent with the broader role of JAZ proteins in hormone crosstalk, positioning PavJAZ8 as a key mediator of the multi-hormone network governing cherry fruit ripening and aroma traits. However, it is important to acknowledge the limitations of our study. Given that the transient fruit transformation system is associated with physical damage and inherent instability, future studies will be based on a stable genetic transformation system to systematically analyze the biological functions of PavJAZ8 and its regulatory roles in fruit ripening and trait development.

5. Conclusions

In this study, nine PavJAZ genes were identified and analyzed in the sweet cherry genome. We systematically studied the gene structures and expression patterns of PavJAZ members. Furthermore, PavJAZ8 was found to be responsive to MeJA. Transient overexpression of PavJAZ8 in sweet cherry fruits broadly regulated the expression of genes involved in aroma volatile biosynthesis, suggesting its potential role in aroma trait development. Functional analysis revealed that PavJAZ8 exerts dual effects on fruit aroma traits, demonstrating the complex and multifaceted role of PavJAZ8 in regulating fruit aroma profiles. Protein interaction assays further confirmed that PavJAZ8 physically interacts with PavMYC2. Our findings establish PavJAZ8 as a key regulator of fruit quality and enhance our understanding of JA signaling in fruit ripening and trait development.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/biom15121721/s1, Table S1: Name and accession number of the genes involved in this study; Table S2. Primers used for real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction; Table S3. Subcellular localization prediction of PavJAZ proteins. Figure S1: Analysis of PavJAZ8 expression in response to ABA, SA, and GA3.

Author Contributions

W.W.: Writing—original draft, Conceptualization, Investigation. T.S.: Software, Writing—review and editing, Visualization. Z.D.: Writing—review and editing, Methodology, Formal analysis. X.Z.: Investigation. J.W.: Data curation. C.W.: Resources. C.F.: Validation. G.Y.: Validation. K.Z.: Supervision. Y.Y.: Supervision. X.D.: Supervision, Conceptualization. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Director’s Fund of the Institute of Forestry and Pomology, Beijing Academy of Agriculture and Forestry Sciences (LGSSZJJ20250102), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32402484).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Kelley, D.S.; Adkins, Y.; Laugero, K.D. A Review of the Health Benefits of Cherries. Nutrients 2018, 10, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Guo, Q.; Wu, C.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Song, G.; Yan, G.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhang, K.; et al. Effect of bagging treatment on fruit anthocyanin biosynthesis in sweet cherry. Agric. Commun. 2025, 3, 100103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, D.; Wang, W.; Hao, Q.; Jia, W. Do Non-climacteric Fruits Share a Common Ripening Mechanism of Hormonal Regulation? Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 923484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Chen, K.; Grierson, D. Molecular and Hormonal Mechanisms Regulating Fleshy Fruit Ripening. Cells 2021, 10, 1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clayton-Cuch, D.; Yu, L.; Shirley, N.; Bradley, D.; Bulone, V.; Böttcher, C. Auxin Treatment Enhances Anthocyanin Production in the Non-Climacteric Sweet Cherry (Prunus avium L.). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teribia, N.; Tijero, V.; Munné-Bosch, S. Linking hormonal profiles with variations in sugar and anthocyanin contents during the natural development and ripening of sweet cherries. New Biotechnol. 2016, 33, 824–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tijero, V.; Teribia, N.; Muñoz, P.; Munné-Bosch, S. Implication of Abscisic Acid on Ripening and Quality in Sweet Cherries: Differential Effects during Pre- and Post-harvest. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignati, E.; Lipska, M.; Dunwell, J.M.; Caccamo, M.; Simkin, A.J. Fruit Development in Sweet Cherry. Plants 2022, 11, 1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Fan, D.; Hao, Q.; Jia, W. Signal transduction in non-climacteric fruit ripening. Hortic. Res. 2022, 9, uhac190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Concha, C.M.; Figueroa, N.E.; Poblete, L.A.; Oñate, F.A.; Schwab, W.; Figueroa, C.R. Methyl jasmonate treatment induces changes in fruit ripening by modifying the expression of several ripening genes in Fragaria chiloensis fruit. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2013, 70, 433–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenn, M.A.; Giovannoni, J.J. Phytohormones in fruit development and maturation. Plant J. 2021, 105, 446–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Bigotes, A.; Figueroa, P.M.; Figueroa, C.R. Jasmonate metabolism and its relationship with abscisic acid during strawberry fruit development and ripening. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2018, 37, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Chen, C.; Yan, Z.; Li, J.; Wang, Y. The methyl jasmonate accelerates the strawberry fruits ripening process. Sci. Hortic. 2019, 249, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Zhang, C.; Pervaiz, T.; Zhao, P.; Liu, Z.; Wang, B.; Wang, C.; Zhang, L.; Fang, J.; Qian, J. Jasmonic acid involves in grape fruit ripening and resistant against Botrytis cinerea. Funct. Integr. Genom. 2016, 16, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, P.; Jiang, Z.; Sun, Q.; Wei, R.; Yin, Y.; Xie, Z.; Larkin, R.M.; Ye, J.; Chai, L.; Deng, X. Jasmonate activates a CsMPK6-CsMYC2 module that regulates the expression of β-citraurin biosynthetic genes and fruit coloration in orange (Citrus sinensis). Plant Cell 2023, 35, 1167–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Pena Moreno, F.; Blanch, G.P.; Flores, G.; Ruiz del Castillo, M.L. Impact of postharvest methyl jasmonate treatment on the volatile composition and flavonol content of strawberries. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2010, 90, 989–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, L.D.; Zúñiga, P.E.; Figueroa, N.E.; Pastene, E.; Escobar-Sepúlveda, H.F.; Figueroa, P.M.; Garrido-Bigotes, A.; Figueroa, C.R. Application of a JA-Ile Biosynthesis Inhibitor to Methyl Jasmonate-Treated Strawberry Fruit Induces Upregulation of Specific MBW Complex-Related Genes and Accumulation of Proanthocyanidins. Molecules 2018, 23, 1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paladines-Quezada, D.F.; Fernández-Fernández, J.I.; Moreno-Olivares, J.D.; Bleda-Sánchez, J.A.; Gómez-Martínez, J.C.; Martínez-Jiménez, J.A.; Gil-Muñoz, R. Application of elicitors in two ripening periods of Vitis vinifera L. cv Monastrell: Influence on anthocyanin concentration of grapes and wines. Molecules 2021, 26, 1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Han, X.; Feng, D.; Yuan, D.; Huang, L.J. Signaling Crosstalk between Salicylic Acid and Ethylene/Jasmonate in Plant Defense: Do We Understand What They Are Whispering? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fresno, D.H.; Munné-Bosch, S. Differential Tissue-Specific Jasmonic Acid, Salicylic Acid, and Abscisic Acid Dynamics in Sweet Cherry Development and Their Implications in Fruit-Microbe Interactions. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 640601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, S.; Motoyama, M.; Michiyama, H.; Kim, M. Roles of jasmonic acid in the development of sweet cherries as measured from fruit or disc samples. Plant Growth Regul. 2002, 37, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balbontín, C.; Gutiérrez, C.; Schreiber, L.; Zeisler-Diehl, V.V.; Marín, J.C.; Urrutia, V.; Hirzel, J.; Figueroa, C.R. Alkane biosynthesis is promoted in methyl jasmonate-treated sweet cherry (Prunus avium) fruit cuticles. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2024, 104, 530–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, D.X.; Feys, B.F.; James, S.; Nieto-Rostro, M.; Turner, J.G. COI1: An Arabidopsis gene required for jasmonate-regulated defense and fertility. Science 1998, 280, 1091–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chini, A.; Fonseca, S.; Fernández, G.; Adie, B.; Chico, J.M.; Lorenzo, O.; García-Casado, G.; López-Vidriero, I.; Lozano, F.M.; Ponce, M.R.; et al. The JAZ family of repressors is the missing link in jasmonate signalling. Nature 2007, 448, 666–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheard, L.B.; Tan, X.; Mao, H.; Withers, J.; Ben-Nissan, G.; Hinds, T.R.; Kobayashi, Y.; Hsu, F.F.; Sharon, M.; Browse, J.; et al. Jasmonate perception by inositol-phosphate-potentiated COI1-JAZ co-receptor. Nature 2010, 468, 400–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thines, B.; Katsir, L.; Melotto, M.; Niu, Y.; Mandaokar, A.; Liu, G.; Nomura, K.; He, S.Y.; Howe, G.A.; Browse, J. JAZ repressor proteins are targets of the SCF(COI1) complex during jasmonate signalling. Nature 2007, 448, 661–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Yao, J.; Ke, J.; Zhang, L.; Lam, V.Q.; Xin, X.F.; Zhou, X.E.; Chen, J.; Brunzelle, J.; Griffin, P.R.; et al. Structural basis of JAZ repression of MYC transcription factors in jasmonate signalling. Nature 2015, 525, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, S.; Chini, A.; Hamberg, M.; Adie, B.; Porzel, A.; Kramell, R.; Miersch, O.; Wasternack, C.; Solano, R. (+)-7-iso-Jasmonoyl-L-isoleucine is the endogenous bioactive jasmonate. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2009, 5, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsir, L.; Chung, H.S.; Koo, A.J.; Howe, G.A. Jasmonate signaling: A conserved mechanism of hormone sensing. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2008, 11, 428–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Luthe, D. Identification and evolution analysis of the JAZ gene family in maize. BMC Genom. 2021, 22, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, C.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, T.; Jiang, J.; Li, J.; Xu, X.; Yang, H. Genome-Wide Identification, Characterization and Expression Analysis of the JAZ Gene Family in Resistance to Gray Leaf Spots in Tomato. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrido-Bigotes, A.; Figueroa, N.E.; Figueroa, P.M.; Figueroa, C.R. Jasmonate signalling pathway in strawberry: Genome-wide identification, molecular characterization and expression of JAZs and MYCs during fruit development and ripening. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0197118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Ouyang, J.; Li, Y.; Zhai, C.; He, B.; Si, H.; Chen, K.; Rose, J.K.C.; Jia, W. A signaling cascade mediating fruit trait development via phosphorylation-modulated nuclear accumulation of JAZ repressor. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2024, 66, 1106–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, J.; Jia, H.; Wu, M.; Zhong, W.; Jia, D.; Wang, Z.; Huang, C. Genome-wide identification and characterization of the TIFY gene family in kiwifruit. BMC Genom. 2022, 23, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Sun, H.; Han, Z.; Wang, S.; Wang, T.; Li, Q.; Tian, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Xu, X. ERF4 affects fruit ripening by acting as a JAZ interactor between ethylene and jasmonic acid hormone signaling pathways. Hortic. Plant J. 2022, 8, 689–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Ji, G.; Guan, W.; Qian, F.; Li, H.; Cai, G.; Wu, X. Genome-Wide Identification and Variation Analysis of JAZ Family Reveals BnaJAZ8.C03 Involved in the Resistance to Plasmodiophora brassicae in Brassica napus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.G.; Zhang, J.; Cai, X.X.; Fan, L.P.; Zhu, Z.H.; Zhu, X.J.; Guo, D.L. Genome-wide survey and expression analysis of JAZ genes in watermelon (Citrullus lanatus). Mol. Biol. Rep. 2024, 52, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Wang, H.; Ma, H.; Zheng, C. Genome-wide analysis of JAZ family genes expression patterns during fig (Ficus carica L.) fruit development and in response to hormone treatment. BMC Genom. 2022, 23, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; Cao, L.; Zhao, X.; Guo, X.; Ye, K.; Jiao, S.; Wang, Y.; He, X.; Dong, C.; Hu, B. Investigation of the JASMONATE ZIM-DOMAIN gene family reveals the canonical JA-signaling pathway in Pineapple. Biology 2022, 11, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, W.; Zhu, D.; Hong, P.; Zhang, S.; Xiao, S.; Tan, Y.; Chen, X.; Xu, L.; Zong, X.; et al. Chromosome-scale genome assembly of sweet cherry (Prunus avium L.) cv. Tieton obtained using long-read and Hi-C sequencing. Hortic. Res. 2020, 7, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Thomas, H.R.; Frank, M.H.; He, Y.; Xia, R. TBtools: An Integrative Toolkit Developed for Interactive Analyses of Big Biological Data. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, J.; Yu, J. KaKs_Calculator 2.0: A toolkit incorporating gamma-series methods and sliding window strategies. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2010, 8, 77–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhang, D.; Yu, K.; Ji, J.; Liu, N.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, M.; Zhang, Y.J.; Ma, X.; Liu, S.; et al. Frequent germplasm exchanges drive the high genetic diversity of Chinese-cultivated common apricot germplasm. Hortic. Res. 2021, 8, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lian, X.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, C.; Gao, F.; Yan, L.; Zheng, X.; Cheng, J.; Wang, W.; Wang, X.; Ye, X.; et al. De novo chromosome-level genome of a semi-dwarf cultivar of Prunus persica identifies the aquaporin PpTIP2 as responsible for temperature-sensitive semi-dwarf trait and PpB3-1 for flower type and size. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2022, 20, 886–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Pi, M.; Gao, Q.; Liu, Z.; Kang, C. Updated annotation of the wild strawberry Fragaria vesca V4 genome. Hortic. Res. 2019, 6, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosmani, P.S.; Flores-Gonzalez, M.; van de Geest, H.; Maumus, F.; Bakker, L.V.; Schijlen, E.; van Haarst, J.; Cordewener, J.; Sanchez-Perez, G.; Peters, S. An improved de novo assembly and annotation of the tomato reference genome using single-molecule sequencing, Hi-C proximity ligation and optical maps. Biorxiv 2019. Biorxiv:767764. [Google Scholar]

- Larkin, M.A.; Blackshields, G.; Brown, N.P.; Chenna, R.; McGettigan, P.A.; McWilliam, H.; Valentin, F.; Wallace, I.M.; Wilm, A.; Lopez, R.; et al. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 2007, 23, 2947–2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterhouse, A.M.; Procter, J.B.; Martin, D.M.; Clamp, M.; Barton, G.J. Jalview Version 2—A multiple sequence alignment editor and analysis workbench. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1189–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Dai, Z.; Li, J.; Ouyang, J.; Li, T.; Zeng, B.; Kang, L.; Jia, K.; Xi, Z.; Jia, W. A Method for Assaying of Protein Kinase Activity In Vivo and Its Use in Studies of Signal Transduction in Strawberry Fruit Ripening. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Liu, C.; Song, L.; Dong, Y.; Chen, L.; Li, M. A Sweet Cherry Glutathione S-Transferase Gene, PavGST1, Plays a Central Role in Fruit Skin Coloration. Cells 2022, 11, 1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, K.C.; Shen, H.B. Cell-PLoc: A package of Web servers for predicting subcellular localization of proteins in various organisms. Nat. Protoc. 2008, 3, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparkes, I.A.; Runions, J.; Kearns, A.; Hawes, C. Rapid, transient expression of fluorescent fusion proteins in tobacco plants and generation of stably transformed plants. Nat. Protoc. 2006, 1, 2019–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schütze, K.; Harter, K.; Chaban, C. Bimolecular Fluorescence Complementation (BiFC) to Study Protein-Protein Interactions in Living Plant Cells. In Plant Signal Transduction; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Wu, C.; Wang, W.; Yan, G.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, K.; Duan, X. Characterization of volatile profiles in cherry fruits: Integration of E-nose and HS-SPME-GC-MS. Food Chem. X 2025, 28, 102632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villavicencio, J.D.; Zoffoli, J.P.; O’Brien, J.A.; Contreras, C. Methyl jasmonate mediated modulation of lipoxygenase pathway modifies aroma biosynthesis during ripening of ’Regina’ sweet cherry (Prunus avium L.). Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2025, 225, 113511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chen, H.; Yang, W.; Li, J.; Tang, W.; Gong, R. Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Analysis of Quality Changes during Sweet Cherry Fruit Development and Mining of Related Genes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ju, L.; Jing, Y.; Shi, P.; Liu, J.; Chen, J.; Yan, J.; Chu, J.; Chen, K.M.; Sun, J. JAZ proteins modulate seed germination through interaction with ABI5 in bread wheat and Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 2019, 223, 246–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oblessuc, P.R.; Obulareddy, N.; DeMott, L.; Matiolli, C.C.; Thompson, B.K.; Melotto, M. JAZ4 is involved in plant defense, growth, and development in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2020, 101, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherif, S.; El-Sharkawy, I.; Mathur, J.; Ravindran, P.; Kumar, P.; Paliyath, G.; Jayasankar, S. A stable JAZ protein from peach mediates the transition from outcrossing to self-pollination. BMC Biol. 2015, 13, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Dai, Z.; Wang, P.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Wu, C.; Feng, C.; Yan, G.; Zhang, K.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Jasmonate ZIM-domain (JAZ) proteins regulate fruit ripening and quality traits: Mechanisms and advances. Food Qual. Saf. 2025, 9, fyaf022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauwels, L.; Barbero, G.F.; Geerinck, J.; Tilleman, S.; Grunewald, W.; Pérez, A.C.; Chico, J.M.; Bossche, R.V.; Sewell, J.; Gil, E.; et al. NINJA connects the co-repressor TOPLESS to jasmonate signalling. Nature 2010, 464, 788–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chini, A.; Fonseca, S.; Chico, J.M.; Fernández-Calvo, P.; Solano, R. The ZIM domain mediates homo- and heteromeric interactions between Arabidopsis JAZ proteins. Plant J. 2009, 59, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrido-Bigotes, A.; Torrejón, M.; Solano, R.; Figueroa, C.R. Interactions of JAZ repressors with anthocyanin biosynthesis-related transcription factors of Fragaria × ananassa. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunewald, W.; Vanholme, B.; Pauwels, L.; Plovie, E.; Inzé, D.; Gheysen, G.; Goossens, A. Expression of the Arabidopsis jasmonate signalling repressor JAZ1/TIFY10A is stimulated by auxin. EMBO Rep. 2009, 10, 923–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, X.; Lee, L.Y.; Xia, K.; Yan, Y.; Yu, H. DELLAs modulate jasmonate signaling via competitive binding to JAZs. Dev. Cell 2010, 19, 884–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.L.; Yao, J.; Mei, C.S.; Tong, X.H.; Zeng, L.J.; Li, Q.; Xiao, L.T.; Sun, T.P.; Li, J.; Deng, X.W.; et al. Plant hormone jasmonate prioritizes defense over growth by interfering with gibberellin signaling cascade. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, E1192–E1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; An, F.; Feng, Y.; Li, P.; Xue, L.; A, M.; Jiang, Z.; Kim, J.M.; To, T.K.; Li, W.; et al. Derepression of ethylene-stabilized transcription factors (EIN3/EIL1) mediates jasmonate and ethylene signaling synergy in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 12539–12544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Dai, S.; Ren, J.; Zhang, C.; Ding, Y.; Li, Z.; Sun, Y.; Ji, K.; Wang, Y.; Li, Q. The role of ABA in the maturation and postharvest life of a nonclimacteric sweet cherry fruit. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2014, 33, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Peng, X.; Feng, C.; Zhang, X.; Du, B.; Zhou, X.; Wang, C.; et al. Abscisic acid-responsive transcription factors PavDof2/6/15 mediate fruit softening in sweet cherry. Plant Physiol. 2022, 190, 2501–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, Y.; Ucar, M.; Yildiz, K.; Ozturk, B. Pre-harvest gibberellic acid (GA3) treatments play an important role on bioactive compounds and fruit quality of sweet cherry cultivars. Sci. Hortic. 2016, 211, 358–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Whiting, M.D. Improving ‘Bing’ sweet cherry fruit quality with plant growth regulators. Sci. Hortic. 2011, 127, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).