In Vitro Digestibility, Structural and Functional Properties of Millettia speciosa Champ. Seed Protein

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Protein Preparation

2.3. Chemical and Proximate Composition Analysis

2.4. Hydrodynamic Radius (Rh) and ζ-Potential

2.5. Circular Dichroism (CD)

2.6. SDS-PAGE Analysis

2.7. Determination of Protein Solubility

2.8. Measurement of Surface Hydrophobicity

2.9. Thermal Properties Analysis

2.10. Amino Acid Analysis

2.11. Water- and Oil-Holding Capacities

2.12. Emulsifying and Foaming Properties

2.12.1. Emulsifying Capacity and Stability

2.12.2. Foaming Capacity and Stability

2.13. In Vitro Simulated Gastrointestinal Digestion

2.14. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Proximate Composition

3.2. Physicochemical Properties of MP

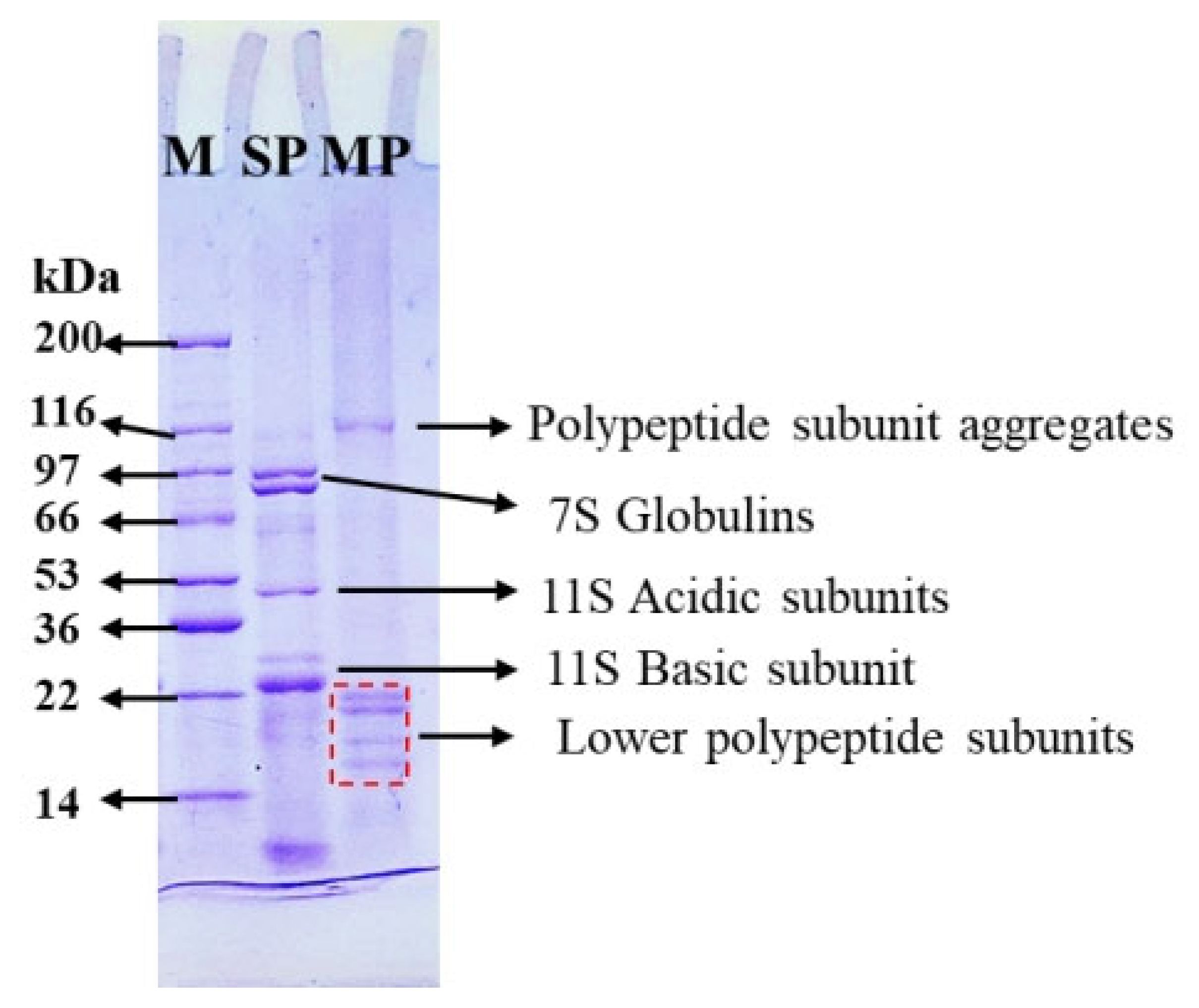

3.2.1. SDS-PAGE Analyses

3.2.2. Thermal Properties

3.2.3. Circular Dichroism

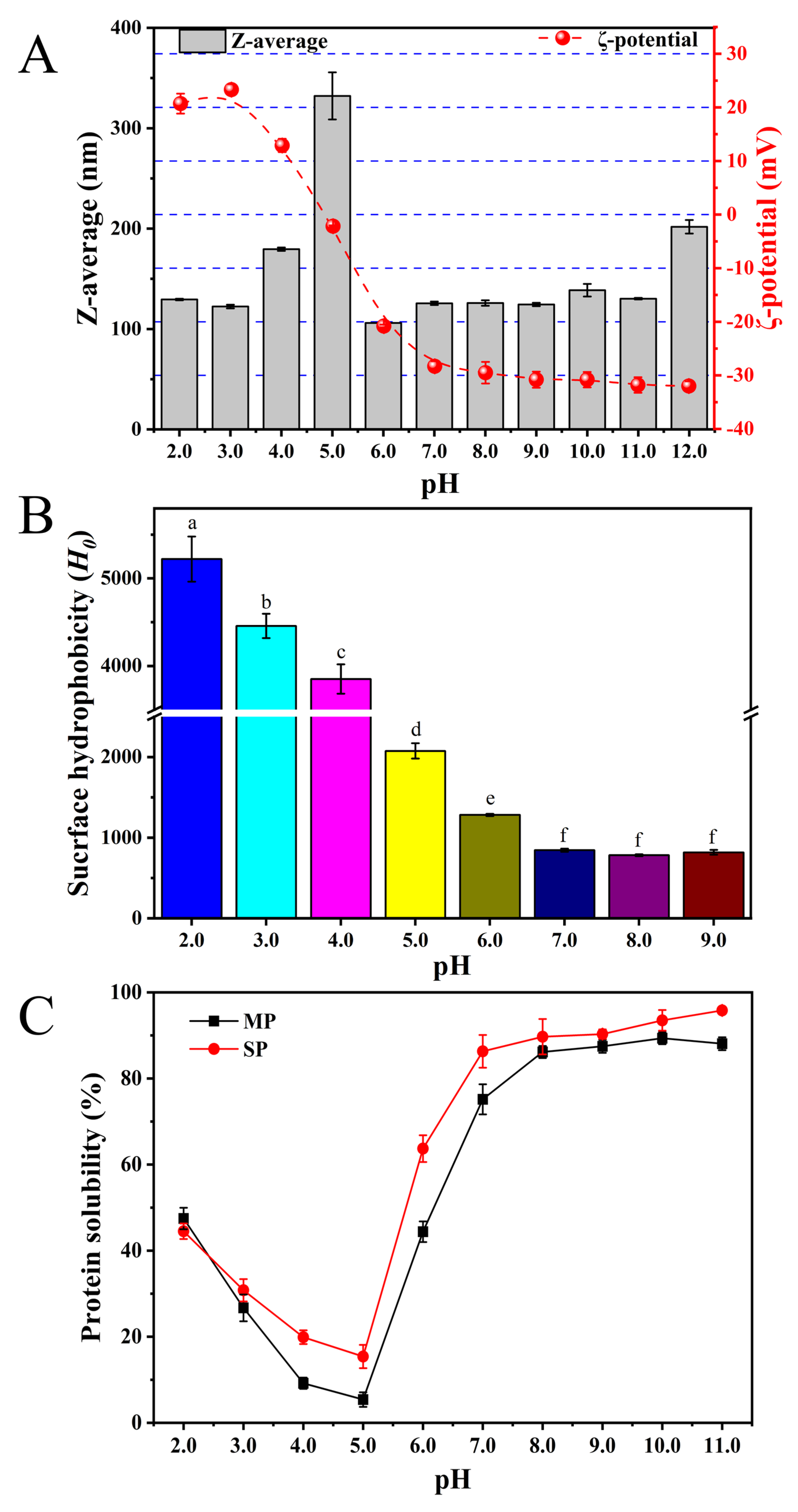

3.2.4. Hydrodynamic Radius and Surface Charge (ζ-Potential)

3.2.5. Surface Hydrophobicity (H0)

3.3. Functional Properties of MP

3.3.1. Protein Solubility

3.3.2. Amino Acid Analysis and Chemical Score

3.3.3. Water-Holding and Fat Absorption Capacities

3.3.4. In Vitro Digestibility

3.4. Emulsion and Foam Properties

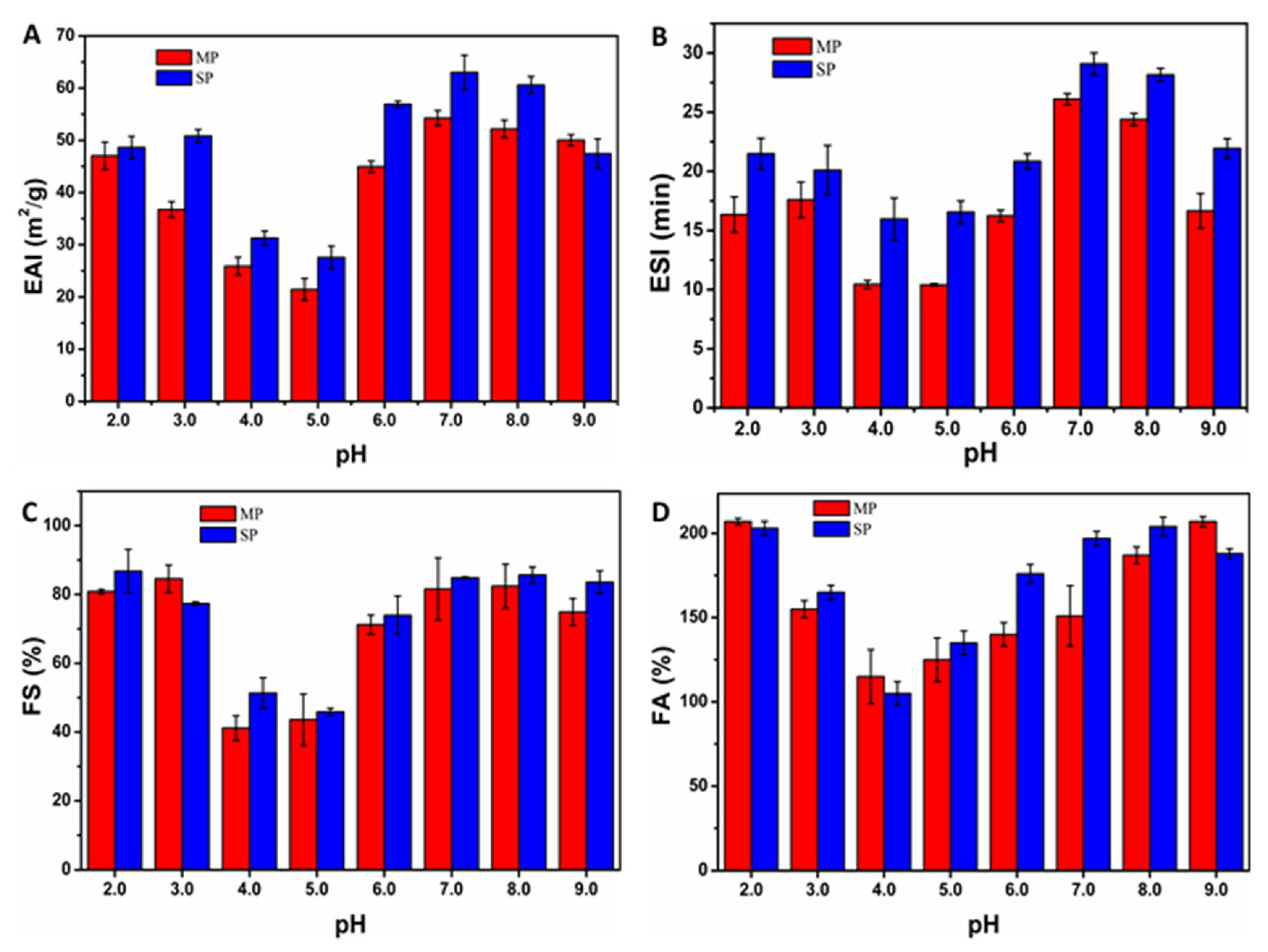

3.4.1. Influence of pH on Emulsification Performance of MP

3.4.2. Influence of pH on Foaming Performance of MP

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hewage, A.; Olatunde, O.O.; Nimalaratne, C.; Malalgoda, M.; Aluko, R.E.; Bandara, N. Novel Extraction technologies for developing plant protein ingredients with improved functionality. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 129, 492–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastrana-Pastrana, Á.J.; Rodríguez-Herrera, R.; Solanilla-Duque, J.F.; Flores-Gallegos, A.C. Plant proteins, insects, edible mushrooms and algae: More sustainable alternatives to conventional animal protein. J. Future Foods 2025, 5, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathollahy, I.; Farmani, J.; Kasaai, M.R.; Hamishehkar, H. Characteristics and functional properties of Persian lime (Citrus latifolia) seed protein isolate and enzymatic hydrolysates. LWT 2021, 140, 110765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Zhong, Z.; Yu, L.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Wang, W.; Chen, P.; Li, J.; Zheng, G. Millettia speciosa Champ. root extracts relieve exhaustive fatigue by regulating gut microbiota in mice. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2025, 203, 115557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Wu, R.; Liu, J.; Huang, J.; Liu, Q.; Yao, M.; Wu, J.; Ye, J.; Li, D.; Gan, L.; et al. Protective role of polysaccharide from the roots of Millettia speciosa Champ in mice with ulcerative colitis induced by dextran sulphate sodium. Nat. Prod. Res. 2024, 2435535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Cui, C.; Lin, Y.; Cai, J. Ameliorating effect on glycolipid metabolism and chemical profile of Millettia speciosa champ. extract. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 279, 114360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Huang, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Xie, F.; Yang, T.; Zeng, L.; Jiang, Z.; Du, J.; Chen, Y.; Niu, D. Natural starches suitable for 3D printing: Rhizome and seed starch from Millettia speciosa champ, a non-conventional source. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 351, 123104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Zeng, Y.J.; Chen, X.; Luo, S.Y.; Pu, L.; Li, F.Z.; Zong, M.H.; Lou, W.Y. A novel polysaccharide from the roots of Millettia Speciosa Champ: Preparation, structural characterization and immunomodulatory activity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 145, 547–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.Y.; Huang, Z.; Chen, X.; Zong, M.H.; Lou, W.Y. Extraction and characterization of a functional protein from Millettia speciosa Champ. leaf. Nat. Prod. Res. 2023, 37, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Lyu, X.; Zhai, D.; Cai, J. Advances in chemical constituents and pharmacological effects of Millettia speciosa Champ. J. Holistic Integr. Pharm. 2021, 2, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Liang, X. Characterization and identification of isoflavonoids in the roots of Millettia speciosa Champ. by UPLC-Q-TOF-MS/MS. Curr. Pharm. Anal. 2019, 15, 580–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.W.; Wang, J.M.; Yang, X.Q.; Qi, J.R.; Hou, J.J. Subcritical water induced complexation of soy protein and rutin: Improved interfacial properties and emulsion stability. J. Food Sci. 2016, 81, C2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.S.; Wang, A.B.; Zang, X.P.; Tan, L.; Xu, B.Y.; Chen, H.H.; Jin, Z.Q.; Ma, W.H. Physicochemical, functional and emulsion properties of edible protein from avocado (Persea americana Mill.) oil processing by-products. Food Chem. 2019, 288, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AOAC. Offfcial Methods of Analysis, 18th ed.; Horwitz, W., Latimer, G., Eds.; AOAC International: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Meng, F.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J.; Liu, X. Enzyme-assisted extraction of proteins from radish leaf and their structure-function relationship in stabilizing high internal phase emulsions compared to soy protein and whey protein. Food Hydrocoll. 2025, 168, 111550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Jiang, H.; Du, G.; Chen, J.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, X. Interfacial engineering through chitin retention unlocks the emulsification potential of Fusarium venenatum mycoprotein. Food Hydrocoll. 2026, 170, 111773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perović, M.; Bojanić, N.; Tomičić, Z.; Milošević, M.; Kostić, M.; Jugović, Z.K.; Antov, M. Nutritional quality, functional properties and in vitro digestibility of protein concentrates from hull-less pumpkin (Cucurbita pepo L.) leaves. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2025, 142, 107408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, H.; Zhao, N.; Li, S.; Sun, S.; Dong, X.; Yu, C. Physicochemical and emulsifying properties of mussel water-soluble proteins as affected by lecithin concentration. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 163, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, P.; Dowling, K.; McKnight, S.; Barrow, C.J.; Wang, B.; Adhikari, B. Preparation, characterization and functional properties of flax seed protein isolate. Food Chem. 2016, 197, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Zeng, M.; Qin, F.; He, Z.; Chen, J. Physicochemical and functional properties of protein extracts from Torreya grandis seeds. Food Chem. 2017, 227, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boye, J.I.; Aksay, S.; Roufik, S.; Ribéreau, S.; Mondor, M.; Farnworth, E.; Rajamohamed, S.H. Comparison of the functional properties of pea, chickpea and lentil protein concentrates processed using ultrafiltration and isoelectric precipitation techniques. Food Res. Int. 2010, 43, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattan, Y.a.; Patil, D.; Vaknin, Y.; Rytwo, G.; Lakemond, C.; Benjamin, O. Characterization of Moringa oleifera leaf and seed protein extract functionality in emulsion model system. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2022, 75, 102903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, H.; Joshi, R.; Gupta, M. Isolation, purification and characterization of antioxidative peptide of pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum) protein hydrolysate. Food Chem. 2016, 204, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halim, N.R.A.; Yusof, H.M.; Sarbon, N.M. Functional and bioactive properties of fish protein hydolysates and peptides: A comprehensive review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 51, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furia, K.A.; Torley, P.J.; Majzoobi, M.; Balfany, C.; Farahnaky, A. Leaf protein concentrate from cauliflower leaves: Effect of filtration and stabilizing solution on extraction and physio-chemical properties. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2025, 103, 104037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevkani, K.; Singh, N.; Kaur, A.; Rana, J.C. Structural and functional characterization of kidney bean and field pea protein isolates: A comparative study. Food Hydrocoll. 2015, 43, 679–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhao, G.; Ren, J.; Zhao, M.; Yang, B. Effect of denaturation during extraction on the conformational and functional properties of peanut protein isolate. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2011, 12, 375–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, M.; Xie, J.; Gong, B.; Xu, X.; Tang, W.; Li, X.; Li, C.; Xie, M. Extraction, physicochemical characteristics and functional properties of Mung bean protein. Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 76, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, R.S.H.; Nickerson, M.T. The effect of pH and temperature pre-treatments on the physicochemical and emulsifying properties of whey protein isolate. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 60, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aderinola, T.A.; Alashi, A.M.; Nwachukwu, I.D.; Fagbemi, T.N.; Enujiugha, V.N.; Aluko, R.E. In vitro digestibility, structural and functional properties of Moringa oleifera seed proteins. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 101, 105574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laligant, A.; Dumay, E.; Casas Valencia, C.; Cuq, J.L.; Cheftel, J.C. Surface hydrophobicity and aggregation of $\beta$-lactoglobulin heated near neutral pH. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1991, 39, 2147–2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.Y.; Tong, P.S.; Gualco, S.; Vink, S. Effect of NaCl addition during diafiltration on the solubility, hydrophobicity, and disulfide bonds of 80% milk protein concentrate powder. J. Dairy Sci. 2012, 95, 3481–3488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolai, T. Formation and functionality of self-assembled whey protein microgels. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2016, 137, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, D.N.; Ingrassia, R.; Busti, P.; Bonino, J.; Delgado, J.F.; Wagner, J.; Boeris, V.; Spelzini, D. Structural characterization of protein isolates obtained from chia (Salvia hispanica L.) seeds. LWT 2018, 90, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Ren, Y.; Xie, W.; Zhou, D.; Tang, S.; Kuang, M.; Wang, Y.; Du, S.-k. Physicochemical and functional properties of protein isolate obtained from cottonseed meal. Food Chem. 2018, 240, 856–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.R.; Tang, Y.; Li, Y.; Shang, W.H.; Yan, J.N.; Du, Y.N.; Wu, H.T.; Zhu, B.W.; Xiong, Y.L. Physiochemical properties and functional characteristics of protein isolates from the Scallop (Patinopecten yessoensis) Gonad. J. Food Sci. 2019, 84, 1023–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, L.A.; Seiquer, I. Transport of amino acids from in vitro digested legume proteins or casein in Caco-2 cell cultures. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 5202–5206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ragab, D.M.; Babiker, E.E.; Eltinay, A.H. Fractionation, solubility and functional properties of cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) proteins as affected by pH and/or salt concentration. Food Chem. 2004, 84, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Wang, Q.; Ma, T.; Ren, J. Comparative studies on the functional properties of various protein concentrate preparations of peanut protein. Food Res. Int. 2009, 42, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, A.U.; Liu, C.; Sathe, S.K. Functional properties of select seed flours. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 60, 325–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufour, C.; Loonis, M.; Delosière, M.; Buffière, C.; Hafnaoui, N.; Santé-Lhoutellier, V.; Rémond, D. The matrix of fruit & vegetables modulates the gastrointestinal bioaccessibility of polyphenols and their impact on dietary protein digestibility. Food Chem. 2018, 240, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piornos, J.A.; Burgos-Díaz, C.; Ogura, T.; Morales, E.; Rubilar, M.; Maureira-Butler, I.; Salvo-Garrido, H. Functional and physicochemical properties of a protein isolate from AluProt-CGNA: A novel protein-rich lupin variety (Lupinus luteus). Food Res. Int. 2015, 76, 719–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.W.; Luo, D.Y.; Chen, Y.J.; Wang, J.M.; Guo, J.; Yang, X.Q. Dry fractionation of surface abrasion for polyphenol-enriched buckwheat protein combined with hydrothermal treatment. Food Chem. 2019, 285, 414–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lajnaf, R.; Picart-Palmade, L.; Cases, E.; Attia, H.; Marchesseau, S.; Ayadi, M.A. The foaming properties of camel and bovine whey: The impact of pH and heat treatment. Food Chem. 2018, 240, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sample | Moisture (%) | Protein (%) | Ash (%) | Lipids (%) | Total Carbohydrates (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Millettia speciosa seeds | 5.98 ± 0.28 a | 29.32 ± 2.18 b | 5.63 ± 0.22 a | 16.90 ± 1.98 a | 42.17 ± 3.54 b |

| Defatted flour | 6.35 ± 0.12 a | 34.50 ± 0.66 b | 4.58 ± 0.17 b | 6.55 ± 0.41 b | 49.02 ± 2.51 a |

| MP B | 4.11 ± 0.30 b | 80.28 ± 2.16 a | 2.37 ± 0.23 c | 0.58 ± 0.04 c | 12.66 ± 1.26 c |

| Peak | To (°C) | Tp (°C) | Te (°C) | ΔH (J/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak 1 | 74.87 ± 0.62 b | 79.65 ± 0.22 b | 83.38 ± 0.33 b | 0.63 ± 0.03 b |

| Peak 2 | 84.04 ± 0.41 a | 91.77 ± 0.05 a | 100.48 ± 2.09 a | 2.58 ± 0.11 a |

| Secondary Structure | Content (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH = 3.0 | pH = 5.0 | pH = 7.0 | pH = 9.0 | |

| α-helix | 37.15 ± 0.21 | 17.52 ± 0.54 | 33.05 ± 0.49 | 35.20 ± 0.56 |

| β-sheet | 15.15 ± 0.10 | 30.99 ± 0.57 | 19.60 ± 0.71 | 17.60 ± 0.55 |

| β-turn | 16.90 ± 0.14 | 16.05 ± 0.05 | 17.75 ± 0.35 | 17.55 ± 0.35 |

| Random coil | 24.55 ± 0.78 | 35.77 ± 0.04 | 26.20 ± 0.14 | 23.60 ± 0.12 |

| Amino Acid | Amino Acid Pattern (mg/g) | WHO/FAO Suggested Requirements C (mg/g) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Samples | Age (Years) | |||||

| MP | SP D | Casein E | 1–2 | 3–10 | >18 | |

| Asp | 58.35 | 130.2 | 33 | |||

| Thr | 33.51 | 35.7 | 34 | 27 | 25 | 23 |

| Ser | 33.82 | 64.6 | 42 | |||

| Glu | 169.25 | 208.2 | 157 | |||

| Gly | 23.57 | 37.6 | 15 | |||

| Ala A | 30.64 | 32.3 | 22 | |||

| Cys | 2.84 | 13.1 | ND | |||

| Val | 44.03 | 39.3 | 51 | 42 | 40 | 39 |

| Met + Cys A | 25.31 | 26.2 | 27 | 26 | 24 | 22 |

| Ile A | 43.07 | 42.0 | 38 | 31 | 31 | 30 |

| Leu A | 52.72 | 71.1 | 61 | 63 | 61 | 59 |

| Tyr | 48.50 | 35.4 | 51 | |||

| Phe + Tyr A | 80.62 | 85.6 | 81 | 46 | 41 | 38 |

| Lys A | 32.80 | 56.8 | 49 | 52 | 48 | 45 |

| His A | 15.04 | 29.5 | 15 | 18 | 16 | 15 |

| Arg | 28.64 | 78.1 | 22 | |||

| Pro | 25.56 | 49.8 | 60 | |||

| EAA/NEAA B (%) | 59.86 | 67.30 | 63.01 | |||

| Sample | WHC (g/g) | OAC (g/g) | In Vitro Digestibility (% N Release) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pepsin A | Pepsin + Trypsin B | |||

| MP | 5.61 ± 0.33 a | 6.24 ± 0.21 b | 57.18 ± 0.82 a | 73.61 ± 2.51 a |

| SP | 5.95 ± 0.21 b | 5.09 ± 0.26 a | 62.64 ± 1.05 b | 77.86 ± 3.01 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, Q.; Ding, S.; Wang, Q.; Xu, L.; Yan, X.; Tang, H.; Yuan, L.; Chen, X.; Wang, Z.; Wang, M. In Vitro Digestibility, Structural and Functional Properties of Millettia speciosa Champ. Seed Protein. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1722. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121722

Yang Q, Ding S, Wang Q, Xu L, Yan X, Tang H, Yuan L, Chen X, Wang Z, Wang M. In Vitro Digestibility, Structural and Functional Properties of Millettia speciosa Champ. Seed Protein. Biomolecules. 2025; 15(12):1722. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121722

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Qing, Shuxian Ding, Qinglong Wang, Li Xu, Xiaoxia Yan, Huan Tang, Langxing Yuan, Xiaoyan Chen, Zhunian Wang, and Maoyuan Wang. 2025. "In Vitro Digestibility, Structural and Functional Properties of Millettia speciosa Champ. Seed Protein" Biomolecules 15, no. 12: 1722. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121722

APA StyleYang, Q., Ding, S., Wang, Q., Xu, L., Yan, X., Tang, H., Yuan, L., Chen, X., Wang, Z., & Wang, M. (2025). In Vitro Digestibility, Structural and Functional Properties of Millettia speciosa Champ. Seed Protein. Biomolecules, 15(12), 1722. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121722