IMAGO: An Improved Model Based on Attention Mechanism for Enhanced Protein Function Prediction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dataset

2.2. Integration of PPI and Protein Attributes

2.3. Self-Supervised Pre-Training

2.4. Fine-Tuning for Protein Function Prediction

2.5. Experimental Setup

2.6. Evaluation Metrics

3. Results

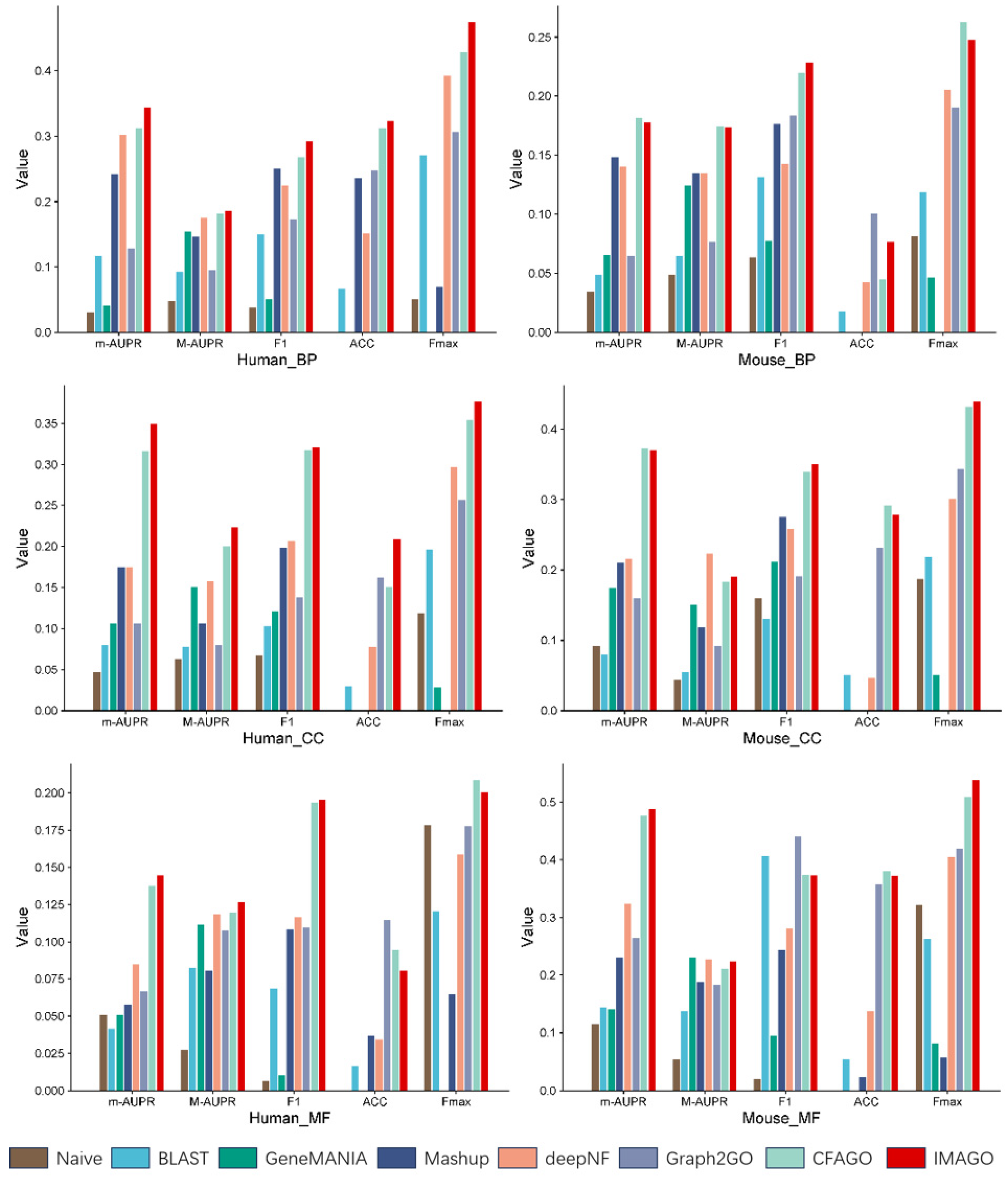

3.1. Experimental Results

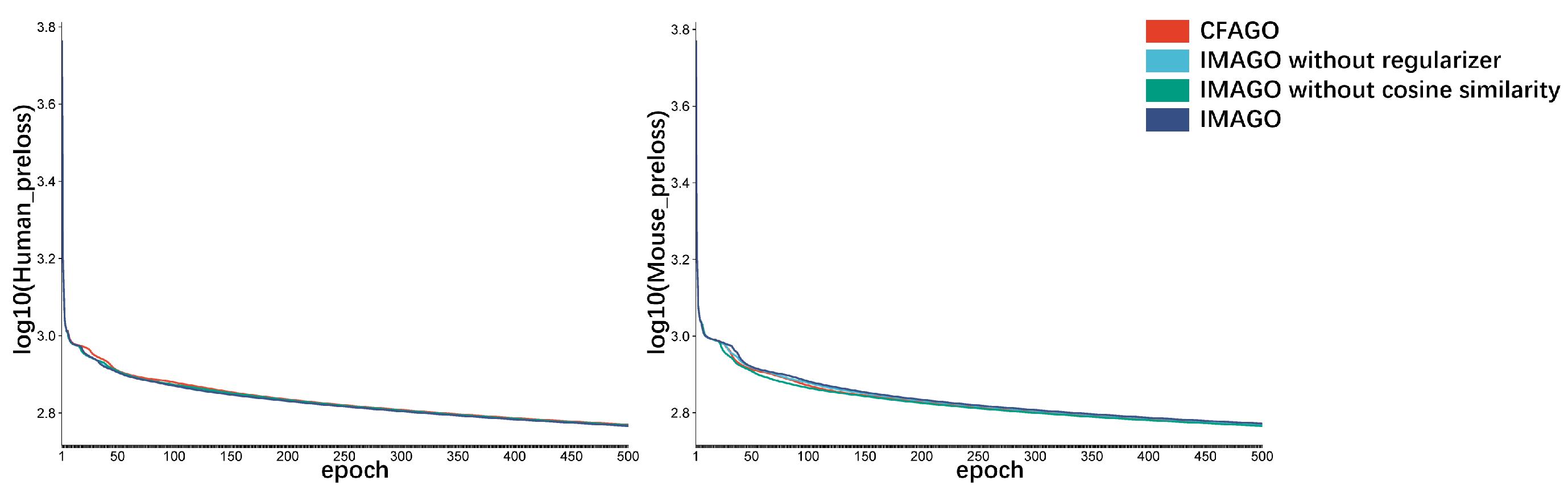

3.2. Ablation Experiment

3.3. Visualization of Protein Embeddings

3.4. Comparative Evaluation of IMAGO on Diverse Species

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Szklarczyk, D.; Kirsch, R.; Koutrouli, M.; Nastou, K.; Mehryary, F.; Hachilif, R.; Gable, A.L.; Fang, T.; Doncheva, N.T.; Pyysalo, S.; et al. The STRING database in 2023: Protein-protein association networks and functional enrichment analyses for a wide range of organisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D638–D646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aleksander, S.; Balhoff, J.; Carbon, S.; Cherry, J.; Drabkin, H.; Ebert, D.; Feuermann, M.; Gaudet, P.; Harris, N. The Gene Ontology Knowledgebase in 2023. Genetics 2023, 224, iyad031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UniProt Consortium. UniProt: The Universal Protein Knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D523–D530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.T.; Thornton, J.M. The Impact of Bioinformatics on Biological Research. In Current Opinion in Structural Biology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; Volume 67, pp. 101–108. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, B.; Xu, J. Accurate Protein Function Prediction via Graph Attention Networks with Predicted Structure Information. Briefings Bioinf. 2022, 23, bbab502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Luo, Q. DualNetGO: A Dual Network Model for Protein Function Prediction via Effective Feature Selection. Bioinformatics 2023, 39, btad123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.; Berger, B.; Peng, J. Compact Integration of Multi-Network Topology for Functional Analysis of Genes. Cell Syst. 2016, 3, 540–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gligorijević, V.; Barot, M.; Bonneau, R. deepNF: Deep Network Fusion for Protein Function Prediction. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 3873–3881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez, J.; Bonet, J.; Borràs, C.; Ferrer, A. Structure-Based Function Prediction Using Structural Alignments and Clustering. Struct. Biol. 2017, 27, 89–95. [Google Scholar]

- Gligorijević, V.; Renfrew, P.D.; Kosciolek, T.; Leman, J.K.; Berenberg, D.; Vatanen, T.; Chandler, C.; Taylor, B.C.; Fisk, I.M.; Vlamakis, H.; et al. Structure-Based Function Prediction Using Graph Convolutional Networks. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; You, R.; Liu, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Zhu, S. Graph Neural Networks for Protein Function Prediction. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1656. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, B.; Cheng, X.; Li, P.; Geng, Y.; Gong, J.; Li, S.; Bei, Z.; Tan, X.; Wang, B.; Zeng, X.; et al. xTrimoPGLM: Unified 100-Billion-Parameter Pretrained Transformer for Deciphering the Language of Protein. Nat. Methods 2024, 22, 1028–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakeley, K.J.; Harbison, C.T.; Parker, C.T.; Cline, M.S.; Smith, J.R. Homology-Based Methods for Protein Function Prediction. Bioinform. J. 2015, 31, 2345–2352. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, J.; Guo, J.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J.; Hu, X. Sequence Encoding via LSTM Networks for Protein Function Prediction. J. Comput. Biol. 2018, 25, 215–222. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, L.; Wang, X. TAWFN: A Deep Learning Framework for Protein Function Prediction. Bioinformatics 2024, 40, btae571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramson, J.; Adler, J.; Dunger, J.; Evans, R.; Green, T.; Pritzel, A.; Ronneberger, O.; Willmore, L.; Ballard, A.J.; Bambrick, J.; et al. Accurate Structure Prediction of Biomolecular Interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 2024, 630, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A.; et al. Highly Accurate Protein Structure Prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Wang, S.; Luo, Z. Multistage Attention-Based Extraction and Fusion of Protein Sequence and Structural Features for Protein Function Prediction. Bioinformatics 2025, 41, btaf374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Chen, L. Applying CNN for Protein Structure Function Prediction. Deep Learn. Bioinf. 2019, 12, 67–75. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, Z.; Luo, X.; Chen, J. Hierarchical Graph Transformer with Contrastive Learning for Protein Function Prediction. Bioinformatics 2023, 39, btad410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafavi, S.; Ray, D.; Warde-Farley, D.; Grouios, C.; Morris, Q. GeneMANIA: A Real-Time Multiple Association Network Integration Algorithm for Predicting Gene Function. Genome Biol. 2008, 9 (Suppl. S1), S4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30; NIPS: Long Beach, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ba, J.L.; Kiros, J.R.; Hinton, G.E. Layer Normalization. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1607.06450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Zhang, S.; Huang, X.; Li, Y. Integrative Approaches for Protein Function Prediction. In Multimodal Data Fusion in Bioinformatics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 254–263. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, K.; Guan, Y.; Zhang, Y. Graph2GO: A Multi-Modal Attributed Network Embedding Method for Inferring Protein Functions. GigaScience 2020, 9, giaa081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; Guo, M.; Jin, X.; Chen, J.; Liu, B. CFAGO: Cross-Fusion of Network and Attributes Based on Attention Mechanism for Protein Function Prediction. Bioinformatics 2023, 39, btad123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridnik, T.; Ben-Baruch, E.; Zamir, N.; Noy, A.; Friedman, I.; Protter, M.; Zelnik-Manor, L. Asymmetric Loss for Multi-Label Classification. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 82–91. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Geng, Y.; Cheng, X. ProtGO: Universal Protein Function Prediction Utilizing Multi-Modal Gene Ontology Knowledge. Bioinformatics 2025, 41, btaf390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Shuai, Y.; Zeng, M. DPFunc: Accurately Predicting Protein Function via Deep Learning with Domain-Guided Structure Information. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species | Statistics | BP | MF | CC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human | #GO terms | 45 | 38 | 35 |

| #training proteins | 3197 | 2747 | 5263 | |

| #validation proteins | 304 | 503 | 577 | |

| #testing proteins | 182 | 719 | 119 | |

| Mouse | #GO terms | 42 | 17 | 37 |

| #training proteins | 2714 | 1185 | 4014 | |

| #validation proteins | 336 | 232 | 694 | |

| #testing proteins | 155 | 126 | 147 |

| Model | Regularizer | Loss | Epoch | BP | MF | CC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFAGO | No | No | 500 | 0.313 | 0.138 | 0.317 |

| IMAGO | Yes | Yes | 5000 | 0.312 | 0.147 | 0.306 |

| IMAGO | No | Yes | 500 | 0.326 | 0.144 | 0.303 |

| IMAGO | Yes | No | 500 | 0.310 | 0.145 | 0.329 |

| IMAGO | Yes | Yes | 500 | 0.346 | 0.145 | 0.350 |

| Biological Process (BP) Aspect | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | m-AUPR | M-AUPR | F1 | ACC | Fmax |

| Human | 0.345 | 0.187 | 0.293 | 0.324 | 0.475 |

| Mouse | 0.178 | 0.174 | 0.229 | 0.077 | 0.248 |

| Drosophila | 0.309 | 0.171 | 0.273 | 0.217 | 0.442 |

| Zebrafish | 0.054 | 0.068 | 0.068 | 0.010 | 0.121 |

| Molecular Function (MF) Aspect | |||||

| Species | m-AUPR | M-AUPR | F1 | ACC | Fmax |

| Human | 0.145 | 0.127 | 0.196 | 0.081 | 0.201 |

| Mouse | 0.489 | 0.224 | 0.374 | 0.373 | 0.539 |

| Drosophila | 0.350 | 0.340 | 0.339 | 0.226 | 0.441 |

| Zebrafish | 0.934 | 0.389 | 0.526 | 0.878 | 0.911 |

| Cellular Component (CC) Aspect | |||||

| Species | m-AUPR | M-AUPR | F1 | ACC | Fmax |

| Human | 0.350 | 0.224 | 0.321 | 0.210 | 0.377 |

| Mouse | 0.371 | 0.191 | 0.351 | 0.279 | 0.440 |

| Drosophila | 0.162 | 0.269 | 0.272 | 0.079 | 0.289 |

| Zebrafish | 0.385 | 0.440 | 0.507 | 0.118 | 0.604 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, M.; Liang, L.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, L.; Zhang, T.; Wang, Z. IMAGO: An Improved Model Based on Attention Mechanism for Enhanced Protein Function Prediction. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1667. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121667

Liu M, Liang L, Wang Q, Zhang Y, Shi L, Zhang T, Wang Z. IMAGO: An Improved Model Based on Attention Mechanism for Enhanced Protein Function Prediction. Biomolecules. 2025; 15(12):1667. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121667

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Meiling, Longchang Liang, Qiutong Wang, Yunmeng Zhang, Lin Shi, Tianjiao Zhang, and Zhenxing Wang. 2025. "IMAGO: An Improved Model Based on Attention Mechanism for Enhanced Protein Function Prediction" Biomolecules 15, no. 12: 1667. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121667

APA StyleLiu, M., Liang, L., Wang, Q., Zhang, Y., Shi, L., Zhang, T., & Wang, Z. (2025). IMAGO: An Improved Model Based on Attention Mechanism for Enhanced Protein Function Prediction. Biomolecules, 15(12), 1667. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121667