Pharmacological and Pharmacokinetic Profile of Cannabidiol in Human Epilepsy: A Review of Metabolism, Therapeutic Drug Monitoring, and Interactions with Antiseizure Medications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Pharmacological Properties of Cannabidiol

2.1. Molecular Targets and Mechanisms

2.2. Preclinical and Clinical Evidence

3. Pharmacokinetics of Cannabidiol

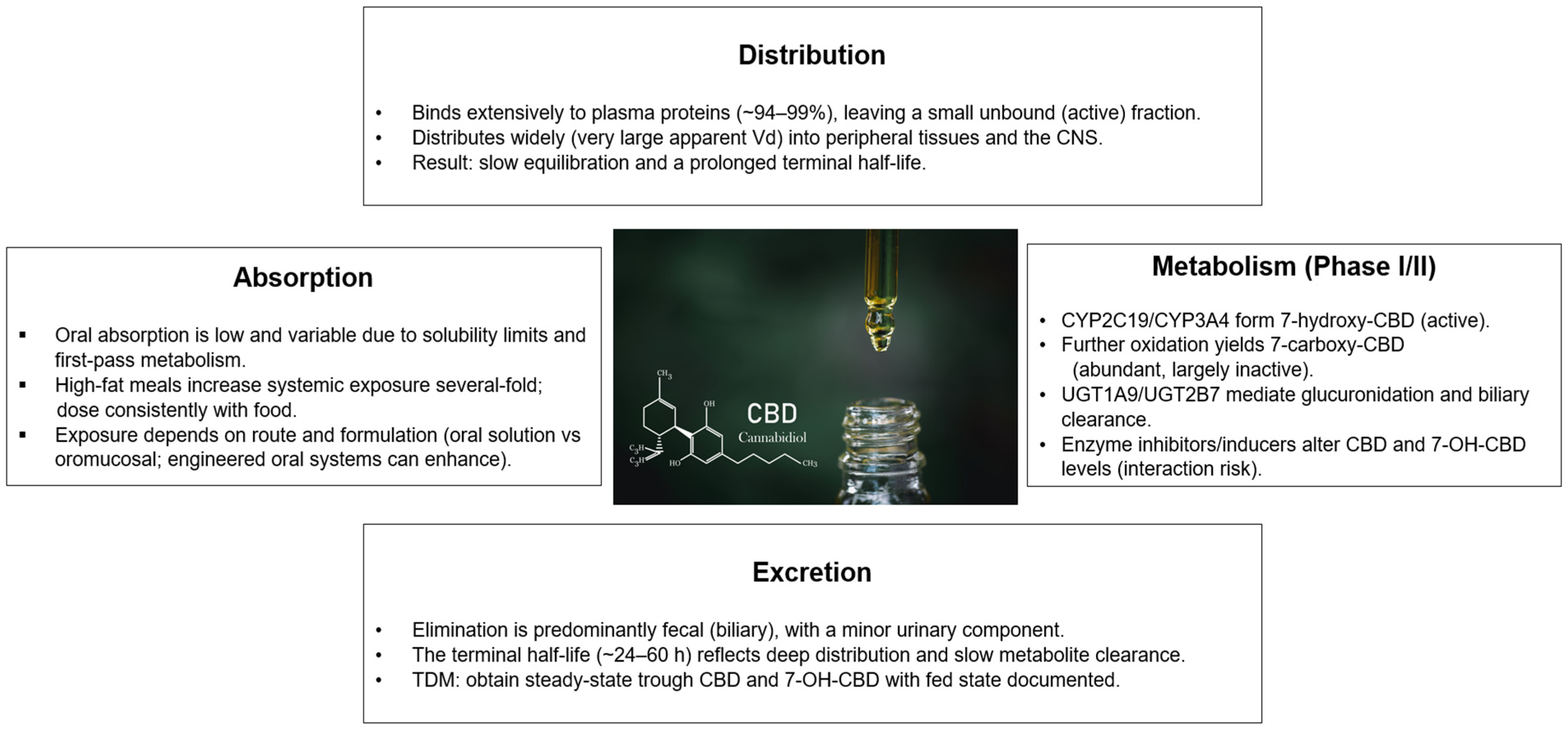

3.1. Absorption and Bioavailability

3.2. Distribution

3.3. Metabolism

3.4. Excretion

3.5. Inter-Individual Variability

4. Therapeutic Drug Monitoring of Cannabidiol: Integration of Metabolic Pathways with Clinical Practice

4.1. Understanding CBD Metabolism for TDM

4.2. Measuring CBD and Its Metabolites: Bioanalytical Methodology

4.3. Candidate Reference Ranges and Clinical Interpretation

4.4. Variability, Sampling Strategy, and Pre-Analytical Considerations

4.5. Drug–Drug Interactions, Active Metabolite, and Clinical Decision Making

5. Drug–Drug Interactions with Antiseizure Medications

5.1. How CBD Interacts with Common Pathways

5.2. Key Drug Interactions

5.2.1. Clobazam

5.2.2. Valproate

5.2.3. Stiripentol

5.3. Other Potential Interactions

6. Clinical Applications in Epilepsy Syndromes

6.1. Lennox–Gastaut Syndrome (LGS)

6.2. Dravet Syndrome

6.3. Tuberous Sclerosis Complex (TSC)

6.4. Other Neurological and Systemic Indications

6.4.1. Neurodevelopmental and Psychiatric Conditions

6.4.2. Movement and Sleep Disorders

6.4.3. Pain and Spasticity

6.4.4. Inflammatory, Dermatologic, and Gastrointestinal Indications

7. Future Directions

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CBD | cannabidiol |

| THC | tetrahydrocannabinol |

| LGS | Lennox–Gastaut syndrome |

| DS | Dravet syndrome |

| TSC | tuberous sclerosis complex |

| PK | pharmacokinetics |

| TDM | therapeutic drug monitoring |

| GPR55 | G protein-coupled receptor 55 |

| TRP | transient receptor potential |

| CYP2C19 | cytochrome P450 2C19 |

| CYP3A4 | cytochrome P450 3A4 |

| UGT | uridine 5′-diphospho-glucuronosyltransferase |

| 7-OH-CBD | 7-hydroxy-cannabidiol |

| 7-COOH-CBD | 7-carboxy-cannabidiol |

| ASM | antiseizure medication |

| CLB | clobazam |

| N-CLB | N-desmethylclobazam |

| VPA | valproate |

| STP | stiripentol |

| PK/PD | pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic |

| ALT | alanine aminotransferase |

| SFD | seizure-free days |

| CGI-C | Clinical Global Impression–change |

| ENT1 | equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 |

| VDAC | voltage-dependent anion channel |

References

- Devinsky, O.; Patel, A.D.; Cross, J.H.; Villanueva, V.; Wirrell, E.C.; Privitera, M.; Greenwood, S.M.; Roberts, C.; Checketts, D.; VanLandingham, K.E.; et al. Effect of Cannabidiol on Drop Seizures in the Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 1888–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johannessen Landmark, C.; Saetre, J.; Gottas, A.; Wolden, M.; McQuade, T.A.; Kjeldsen, S.F.; Vatevik, A.; Saetre, E.; Svendsen, T.; Burns, M.L.; et al. Pharmacokinetic variability and use of therapeutic drug monitoring of cannabidiol in patients with refractory epilepsy. Epilepsia 2025, 66, 1477–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Yang, B.; Li, H.; Chen, L. An overview on synthetic and biological activities of cannabidiol (CBD) and its derivatives. Bioorg. Chem. 2023, 140, 106810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbasi, H.; Abbasi, M.M.; Pasand, M.; Mohtadi, M.; Bakhshimoghaddam, F.; Eslamian, G. Exploring the efficacy and safety of cannabidiol in individuals with epilepsy: An umbrella review of meta-analyses and systematic reviews. Inflammopharmacology 2024, 32, 2987–3005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devinsky, O.; Patel, A.D.; Thiele, E.A.; Wong, M.H.; Appleton, R.; Harden, C.L.; Greenwood, S.; Morrison, G.; Sommerville, K.; Group, G.P.A.S. Randomized, dose-ranging safety trial of cannabidiol in Dravet syndrome. Neurology 2018, 90, e1204–e1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiele, E.A.; Marsh, E.D.; French, J.A.; Mazurkiewicz-Beldzinska, M.; Benbadis, S.R.; Joshi, C.; Lyons, P.D.; Taylor, A.; Roberts, C.; Sommerville, K.; et al. Cannabidiol in patients with seizures associated with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (GWPCARE4): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2018, 391, 1085–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wechsler, R.T.; Burdette, D.E.; Gidal, B.E.; Hyslop, A.; McGoldrick, P.E.; Thiele, E.A.; Valeriano, J. Consensus panel recommendations for the optimization of EPIDIOLEX(R) treatment for seizures associated with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, Dravet syndrome, and tuberous sclerosis complex. Epilepsia Open 2024, 9, 1632–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strzelczyk, A.; Schubert-Bast, S. Expanding the Treatment Landscape for Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome: Current and Future Strategies. CNS Drugs 2021, 35, 61–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devinsky, O.; Jones, N.A.; Cunningham, M.O.; Jayasekera, B.A.P.; Devore, S.; Whalley, B.J. Cannabinoid treatments in epilepsy and seizure disorders. Physiol. Rev. 2024, 104, 591–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez Naya, N.; Kelly, J.; Corna, G.; Golino, M.; Polizio, A.H.; Abbate, A.; Toldo, S.; Mezzaroma, E. An Overview of Cannabidiol as a Multifunctional Drug: Pharmacokinetics and Cellular Effects. Molecules 2024, 29, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millar, S.A.; Stone, N.L.; Yates, A.S.; O’Sullivan, S.E. A Systematic Review on the Pharmacokinetics of Cannabidiol in Humans. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borowicz-Reutt, K.; Czernia, J.; Krawczyk, M. CBD in the Treatment of Epilepsy. Molecules 2024, 29, 1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Isola, G.B.; Verrotti, A.; Sciaccaluga, M.; Dini, G.; Ferrara, P.; Parnetti, L.; Costa, C. Cannabidiol: Metabolism and clinical efficacy in epileptic patients. Expert. Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2024, 20, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britch, S.C.; Babalonis, S.; Walsh, S.L. Cannabidiol: Pharmacology and therapeutic targets. Psychopharmacology 2021, 238, 9–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Arellano, J.; Canseco-Alba, A.; Cutler, S.J.; Leon, F. The Polypharmacological Effects of Cannabidiol. Molecules 2023, 28, 3271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, C.J.; Galettis, P.; Schneider, J. The pharmacokinetics and the pharmacodynamics of cannabinoids. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2018, 84, 2477–2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miziak, B.; Walczak, A.; Szponar, J.; Pluta, R.; Czuczwar, S.J. Drug-drug interactions between antiepileptics and cannabinoids. Expert. Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2019, 15, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ujvary, I.; Hanus, L. Human Metabolites of Cannabidiol: A Review on Their Formation, Biological Activity, and Relevance in Therapy. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2016, 1, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stollberger, C.; Finsterer, J. Cannabidiol’s impact on drug-metabolization. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2023, 118, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nachnani, R.; Knehans, A.; Neighbors, J.D.; Kocis, P.T.; Lee, T.; Tegeler, K.; Trite, T.; Raup-Konsavage, W.M.; Vrana, K.E. Systematic review of drug-drug interactions of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol, cannabidiol, and Cannabis. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1282831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancock, E.C.; Cross, J.H. Treatment of Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 2013, CD003277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raucci, U.; Pietrafusa, N.; Paolino, M.C.; Di Nardo, G.; Villa, M.P.; Pavone, P.; Terrin, G.; Specchio, N.; Striano, P.; Parisi, P. Cannabidiol Treatment for Refractory Epilepsies in Pediatrics. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 586110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staben, J.; Koch, M.; Reid, K.; Muckerheide, J.; Gilman, L.; McGuinness, F.; Kiesser, S.; Oswald, I.W.H.; Koby, K.A.; Martin, T.J.; et al. Cannabidiol and cannabis-inspired terpene blends have acute prosocial effects in the BTBR mouse model of autism spectrum disorder. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1185737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechoulam, R.; Parker, L.A.; Gallily, R. Cannabidiol: An overview of some pharmacological aspects. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2002, 42, 11S–19S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, J.; Sun, L.; Qin, Y.; Peng, L.; Gong, Y.; Gao, C.; Shen, W.; Li, M. Cannabinoids improve mitochondrial function in skeletal muscle of exhaustive exercise training rats by inhibiting mitophagy through the PINK1/PARKIN and BNIP3 pathways. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2024, 389, 110855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGilveray, I.J. Pharmacokinetics of cannabinoids. Pain. Res. Manag. 2005, 10 (Suppl. A), 15A–22A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millar, S.A.; Stone, N.L.; Bellman, Z.D.; Yates, A.S.; England, T.J.; O’Sullivan, S.E. A systematic review of cannabidiol dosing in clinical populations. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2019, 85, 1888–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devinsky, O.; Cross, J.H.; Laux, L.; Marsh, E.; Miller, I.; Nabbout, R.; Scheffer, I.E.; Thiele, E.A.; Wright, S.; Cannabidiol in Dravet Syndrome Study, G. Trial of Cannabidiol for Drug-Resistant Seizures in the Dravet Syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 2011–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espinosa-Jovel, C.; Riveros, S.; Bolanos-Almeida, C.; Salazar, M.R.; Inga, L.C.; Guio, L. Real-world evidence on the use of cannabidiol for the treatment of drug resistant epilepsy not related to Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, Dravet syndrome or Tuberous Sclerosis Complex. Seizure 2023, 112, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannone, L.F.; Arena, G.; Battaglia, D.; Bisulli, F.; Bonanni, P.; Boni, A.; Canevini, M.P.; Cantalupo, G.; Cesaroni, E.; Contin, M.; et al. Results From an Italian Expanded Access Program on Cannabidiol Treatment in Highly Refractory Dravet Syndrome and Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 673135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, R.; Giridharan, N.; Anand, V.; Garg, S.K. Clobazam monotherapy for focal or generalized seizures. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 7, CD009258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, L.L.; Absalom, N.L.; Abelev, S.V.; Low, I.K.; Doohan, P.T.; Martin, L.J.; Chebib, M.; McGregor, I.S.; Arnold, J.C. Coadministered cannabidiol and clobazam: Preclinical evidence for both pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic interactions. Epilepsia 2019, 60, 2224–2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landmark, C.J.; Brandl, U. Pharmacology and drug interactions of cannabinoids. Epileptic Disord. 2020, 22, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbotts, K.S.; Nguyen, J.D.; O’Connor, P.; McDonald, M.; Morrison, S.A. Pharmacokinetics, Interaction with Food, and Influence on CYP3A4 Activity of Oral Cannabidiol Preparations in Humans. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caceres Guido, P.; Riva, N.; Caraballo, R.; Reyes, G.; Huaman, M.; Gutierrez, R.; Agostini, S.; Fabiana Delaven, S.; Perez Montilla, C.A.; Garcia Bournissen, F.; et al. Pharmacokinetics of cannabidiol in children with refractory epileptic encephalopathy. Epilepsia 2021, 62, e7–e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mechoulam, R.; Peters, M.; Murillo-Rodriguez, E.; Hanus, L.O. Cannabidiol—Recent advances. Chem. Biodivers. 2007, 4, 1678–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patsalos, P.N.; Szaflarski, J.P.; Gidal, B.; VanLandingham, K.; Critchley, D.; Morrison, G. Clinical implications of trials investigating drug-drug interactions between cannabidiol and enzyme inducers or inhibitors or common antiseizure drugs. Epilepsia 2020, 61, 1854–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, G.; Crockett, J.; Blakey, G.; Sommerville, K. A Phase 1, Open-Label, Pharmacokinetic Trial to Investigate Possible Drug-Drug Interactions Between Clobazam, Stiripentol, or Valproate and Cannabidiol in Healthy Subjects. Clin. Pharmacol. Drug Dev. 2019, 8, 1009–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, K.; Yamaori, S.; Funahashi, T.; Kimura, T.; Yamamoto, I. Cytochrome P450 enzymes involved in the metabolism of tetrahydrocannabinols and cannabinol by human hepatic microsomes. Life Sci. 2007, 80, 1415–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Saharan, V.A.; Banerjee, D.; Ram, V.; Kulhari, H.; Pooja, D.; Singh, A. A comprehensive update on cannabidiol, its formulations and drug delivery systems. Phytochem. Rev. 2024, 24, 2723–2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patsalos, P.N.; Berry, D.J.; Bourgeois, B.F.; Cloyd, J.C.; Glauser, T.A.; Johannessen, S.I.; Leppik, I.E.; Tomson, T.; Perucca, E. Antiepileptic drugs—Best practice guidelines for therapeutic drug monitoring: A position paper by the subcommission on therapeutic drug monitoring, ILAE Commission on Therapeutic Strategies. Epilepsia 2008, 49, 1239–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosseini, A.; McLachlan, A.J.; Lickliter, J.D. A Phase I Trial of the Safety, Tolerability and Pharmacokinetics of Cannabidiol Administered as Single-Dose Oil Solution and Single and Multiple Doses of a Sublingual Wafer in Healthy Volunteers. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2021, 87, 2070–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilmartin, C.G.S.; Dowd, Z.; Parker, A.P.J.; Harijan, P. Interaction of cannabidiol with other antiseizure medications: A narrative review. Seizure 2021, 86, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bialer, M.; Perucca, E. Does cannabidiol have antiseizure activity independent of its interactions with clobazam? An appraisal of the evidence from randomized controlled trials. Epilepsia 2020, 61, 1082–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochen, S.; Villanueva, M.; Bayarres, L.; Daza-Restrepo, A.; Gonzalez Martinez, S.; Oddo, S. Cannabidiol as an adjuvant treatment in adults with drug-resistant focal epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2023, 144, 109210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabbout, R.; Arzimanoglou, A.; Auvin, S.; Berquin, P.; Desurkar, A.; Fuller, D.; Nortvedt, C.; Pulitano, P.; Rosati, A.; Soto, V.; et al. Retrospective chart review study of use of cannabidiol (CBD) independent of concomitant clobazam use in patients with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome or Dravet syndrome. Seizure 2023, 110, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, J.A.; Knupp, K.G. Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome: Current Treatments, Novel Therapeutics, and Future Directions. Neurotherapeutics 2023, 20, 1255–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, J.D.R.; Pacheco, J.C.; Rossi, G.N.; de-Paulo, B.O.; Zuardi, A.W.; Guimaraes, F.S.; Hallak, J.E.C.; Crippa, J.A.; Dos Santos, R.G. Adverse Effects of Oral Cannabidiol: An Updated Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials (2020-2022). Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Camargo, R.W.; de Novais Junior, L.R.; da Silva, L.M.; Meneguzzo, V.; Daros, G.C.; da Silva, M.G.; de Bitencourt, R.M. Implications of the endocannabinoid system and the therapeutic action of cannabinoids in autism spectrum disorder: A literature review. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2022, 221, 173492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auvin, S.; Nortvedt, C.; Fuller, D.S.; Sahebkar, F. Seizure-free days as a novel outcome in patients with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome: Post hoc analysis of patients receiving cannabidiol in two randomized controlled trials. Epilepsia 2023, 64, 1812–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, J.; Skrobanski, H.; Moore-Ramdin, L.; Kornalska, K.; Swinburn, P.; Bowditch, S. Caregivers’ Perspectives on the Impact of Cannabidiol (CBD) Treatment for Dravet and Lennox-Gastaut Syndromes: A Multinational Qualitative Study. J. Child. Neurol. 2023, 38, 394–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Specchio, N.; Auvin, S.; Greco, T.; Lagae, L.; Nortvedt, C.; Zuberi, S.M. Clinically Meaningful Reduction in Drop Seizures in Patients with Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome Treated with Cannabidiol: Post Hoc Analysis of Phase 3 Clinical Trials. CNS Drugs 2025, 39, 1025–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lattanzi, S.; Trinka, E.; Striano, P.; Rocchi, C.; Salvemini, S.; Silvestrini, M.; Brigo, F. Highly Purified Cannabidiol for Epilepsy Treatment: A Systematic Review of Epileptic Conditions Beyond Dravet Syndrome and Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome. CNS Drugs 2021, 35, 265–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, C.M.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, J.S.; Park, B.J.; Lee, H.K.; Kim, H.D.; Kang, H.C. Cannabidiol for Treating Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome and Dravet Syndrome in Korea. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2020, 35, e427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auvin, S.; Arzimanoglou, A.; Falip, M.; Striano, P.; Cross, J.H. Refining management strategies for Lennox-Gastaut syndrome: Updated algorithms and practical approaches. Epilepsia Open 2025, 10, 85–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aderinto, N.; Olatunji, G.; Kokori, E.; Ajayi, Y.I.; Akinmoju, O.; Ayedun, A.S.; Ayoola, O.I.; Aderinto, N.O. The efficacy and safety of cannabidiol (CBD) in pediatric patients with Dravet Syndrome: A narrative review of clinical trials. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2024, 29, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samanta, D. A comprehensive review of evolving treatment strategies for Dravet syndrome: Insights from randomized trials, meta-analyses, real-world evidence, and emerging therapeutic approaches. Epilepsy Behav. 2025, 162, 110171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eltze, C.; Alshehhi, S.; Ghfeli, A.A.; Vyas, K.; Saravanai-Prabu, S.; Gusto, G.; Khachatryan, A.; Martinez, M.; Desurkar, A. The use of cannabidiol in patients with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome and Dravet syndrome in the UK Early Access Program: A retrospective chart review study. Epilepsy Behav. Rep. 2025, 29, 100731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunning, B.; Mazurkiewicz-Beldzinska, M.; Chin, R.F.M.; Bhathal, H.; Nortvedt, C.; Dunayevich, E.; Checketts, D. Cannabidiol in conjunction with clobazam: Analysis of four randomized controlled trials. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2021, 143, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wirrell, E.C.; Hood, V.; Knupp, K.G.; Meskis, M.A.; Nabbout, R.; Scheffer, I.E.; Wilmshurst, J.; Sullivan, J. International consensus on diagnosis and management of Dravet syndrome. Epilepsia 2022, 63, 1761–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrini, R.; Chiron, C.; Vandame, D.; Linley, W.; Toward, T. Comparative efficacy and safety of stiripentol, cannabidiol and fenfluramine as first-line add-on therapies for seizures in Dravet syndrome: A network meta-analysis. Epilepsia Open 2024, 9, 689–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiele, E.A.; Bebin, E.M.; Bhathal, H.; Jansen, F.E.; Kotulska, K.; Lawson, J.A.; O’Callaghan, F.J.; Wong, M.; Sahebkar, F.; Checketts, D.; et al. Add-on Cannabidiol Treatment for Drug-Resistant Seizures in Tuberous Sclerosis Complex: A Placebo-Controlled Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Neurol. 2021, 78, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Hadjinicolaou, A.; Peters, J.M.; Salussolia, C.L. Treatment-resistant epilepsy and tuberous sclerosis complex: Treatment, maintenance, and future directions. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2023, 19, 733–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronica, E.; Specchio, N.; Luinenburg, M.J.; Curatolo, P. Epileptogenesis in tuberous sclerosis complex-related developmental and epileptic encephalopathy. Brain 2023, 146, 2694–2710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melas, P.A.; Scherma, M.; Fratta, W.; Cifani, C.; Fadda, P. Cannabidiol as a Potential Treatment for Anxiety and Mood Disorders: Molecular Targets and Epigenetic Insights from Preclinical Research. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schouten, M.; Dalle, S.; Mantini, D.; Koppo, K. Cannabidiol and brain function: Current knowledge and future perspectives. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1328885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Legare, C.A.; Raup-Konsavage, W.M.; Vrana, K.E. Therapeutic Potential of Cannabis, Cannabidiol, and Cannabinoid-Based Pharmaceuticals. Pharmacology 2022, 107, 131–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlost, J.; Bryk, M.; Starowicz, K. Cannabidiol for Pain Treatment: Focus on Pharmacology and Mechanism of Action. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calonge, Q.; Besnard, A.; Bailly, L.; Damiano, M.; Pichit, P.; Dupont, S.; Gourfinkel-An, I.; Navarro, V. Cannabidiol Treatment for Adult Patients with Drug-Resistant Epilepsies: A Real-World Study in a Tertiary Center. Brain Behav. 2024, 14, e70122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhne, F.; Becker, L.L.; Bast, T.; Bertsche, A.; Borggraefe, I.; Bosselmann, C.M.; Fahrbach, J.; Hertzberg, C.; Herz, N.A.; Hirsch, M.; et al. Real-world data on cannabidiol treatment of various epilepsy subtypes: A retrospective, multicenter study. Epilepsia Open 2023, 8, 360–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhu, H.; Liu, T.; Guo, Z.; Zhao, C.; He, Z.; Zheng, W. Comparison of various doses of oral cannabidiol for treating refractory epilepsy indications: A network meta-analysis. Front. Neurol. 2024, 15, 1243597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Sun, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, S.; Ding, H.; Wang, G.; Li, X. Assessing Cannabidiol as a Therapeutic Agent for Preventing and Alleviating Alzheimer’s Disease Neurodegeneration. Cells 2023, 12, 2672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, S.; Quigley, A.; Rochfort, S.; Christodoulou, J.; Van Bergen, N.J. Cannabinoids and Genetic Epilepsy Models: A Review with Focus on CDKL5 Deficiency Disorder. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glatt, S.; Shohat, S.; Yam, M.; Goldstein, L.; Maidan, I.; Fahoum, F. Cannabidiol-enriched oil for adult patients with drug-resistant epilepsy: Prospective clinical and electrophysiological study. Epilepsia 2024, 65, 2270–2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, E.R.; Cummins, T.R. Differential inhibition of human Nav1.2 resurgent and persistent sodium currents by cannabidiol and GS967. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Fan, X.; Jin, X.; Jo, S.; Zhang, H.B.; Fujita, A.; Bean, B.P.; Yan, N. Cannabidiol inhibits Nav channels through two distinct binding sites. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Domain | CBD (Parent) | 7-OH-CBD (Active Metabolite) |

|---|---|---|

| Analyte priority | Core target for level-guided dosing | Core; interpret alongside CBD |

| Matrix/method | Serum or plasma; validated LC-MS/MS with reported LLOQ and precision | Same specimen/method as CBD |

| Sampling time | Pre-dose (trough) at steady state | Same timing (paired with CBD) |

| When to recheck | After any change in dose, formulation, or interacting drug, re-assess once a new steady state is expected (~5–12 days) | Same |

| Pre-analytical documentation | Feeding state (high-fat or standard), formulation (oral solution vs. others), clock time of last dose, total daily dose, co-medications, ALT/AST, adherence notes | Same |

| Proposed reference interval | 0.15–0.50 μmol/L | 0.04–0.25 μmol/L |

| Factors that increase levels | High-fat meals; CYP inhibitors; hepatic impairment; reduced CYP2C19 activity | Often rises in parallel with CBD; may be accentuated with greater metabolic conversion |

| Factors that decrease levels | CYP inducers; fasted sampling; switch to lower-bioavailability formulation; missed doses | Typically tracks with CBD decreases |

| Interpretive patterns | CBD low & 7-OH-CBD low: underexposure or nonadherence/fasted state. CBD in range & 7-OH-CBD high: enhanced metabolism or timing error. CBD high ± adverse effects: review feeding/formulation and interactions. | Use the ratio to contextualize patterns above |

| Actionable decision rules | Below range with seizures: up-titrate in small weekly steps (~5 mg/kg/day) within labeled ranges (10–20 mg/kg/day for LGS/DS; up to 25 mg/kg/day for TSC), then re-check at the next steady state. Above range with adverse effects: reduce dose or optimize sensitive co-therapies (e.g., clobazam dose reduction); within range: maintain and continue LFT surveillance. | Interpret changes together with CBD; disproportionate 7-OH-CBD suggests metabolism/interaction effects that may guide co-therapy adjustments |

| ASM (Co-Therapy) | Predominant Mechanism | Direction/Magnitude | Clinical Consequence | Recommended Management |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clobazam (CLB) | CYP2C19 inhibition by CBD, with NCLB ↑ | Increase, several-fold | Somnolence/sedation, ataxia; efficacy amplified | Pre-empt/early CLB reduction (25–50%); consider N-CLB check; caregiver education |

| Valproate (VPA) | PD/hepatic signal (no consistent PK shift) | Transaminases ↑ (dose-related) | ALT/AST elevations more frequent | Baseline & periodic LFTs; slower CBD up-titration; re-check after changes |

| Stiripentol (STP) | CYP2C19 inhibitor; interacts with CLB pathway | Augments N-CLB rise; small CBD/STP shifts | Additive sedation in CBD+CLB+STP | Split CBD dose; early review; adjust CLB first if sedation |

| Brivaracetam (BRV) | Not fully defined; possible metabolic interplay | Modest ↑ | Occasional overshoot of reference range | Targeted level check if AEs/efficacy change; symptom-driven titration |

| Topiramate (TPM) | Unknown/indirect | Variable, modest ↑ | Headache/appetite/behavioral AEs | Check if off-trajectory; clinical monitoring |

| Zonisamide (ZNS) | Unknown/indirect | Variable, modest ↑ | Cognitive/behavioral AEs possible | Monitor and adjust if needed |

| Rufinamide (RUF) | Unknown/indirect | Variable, modest ↑ | Somnolence/dizziness may increase | Consider dose refinement if AEs emerge |

| Levetiracetam (LEV) | No consistent PK interaction | Neutral (PK); possible PD interplay | Irritability/behavior may fluctuate | Symptom-driven adjustments; no routine PK change |

| Everolimus/Sirolimus (TSC context) | CYP3A4/P-gp substrates; CBD inhibitory profile | Exposure ↑ (clinically relevant) | Mucositis, hyperlipidemia risk ↑ | Trough-guided dose adjustment; document start/stop timing |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Na, J.-H.; Lee, Y.-M. Pharmacological and Pharmacokinetic Profile of Cannabidiol in Human Epilepsy: A Review of Metabolism, Therapeutic Drug Monitoring, and Interactions with Antiseizure Medications. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1668. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121668

Na J-H, Lee Y-M. Pharmacological and Pharmacokinetic Profile of Cannabidiol in Human Epilepsy: A Review of Metabolism, Therapeutic Drug Monitoring, and Interactions with Antiseizure Medications. Biomolecules. 2025; 15(12):1668. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121668

Chicago/Turabian StyleNa, Ji-Hoon, and Young-Mock Lee. 2025. "Pharmacological and Pharmacokinetic Profile of Cannabidiol in Human Epilepsy: A Review of Metabolism, Therapeutic Drug Monitoring, and Interactions with Antiseizure Medications" Biomolecules 15, no. 12: 1668. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121668

APA StyleNa, J.-H., & Lee, Y.-M. (2025). Pharmacological and Pharmacokinetic Profile of Cannabidiol in Human Epilepsy: A Review of Metabolism, Therapeutic Drug Monitoring, and Interactions with Antiseizure Medications. Biomolecules, 15(12), 1668. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121668