Molecular Differences in Invasive Encapsulated Follicular Variant of Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma (IEFVPTC) and Infiltrative Follicular Variant of Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma (IFVPTC): The Role of Extracellular Matrix

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Minimally invasive—showing capsular invasion only;

- Encapsulated angioinvasive—exhibiting venous invasion, with or without capsular penetration;

- Widely invasive—where the tumor grossly invades the surrounding thyroid parenchyma.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Selection

2.2. Nucleic Acid Extraction and Purification

2.3. Differential Gene Expression Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Features

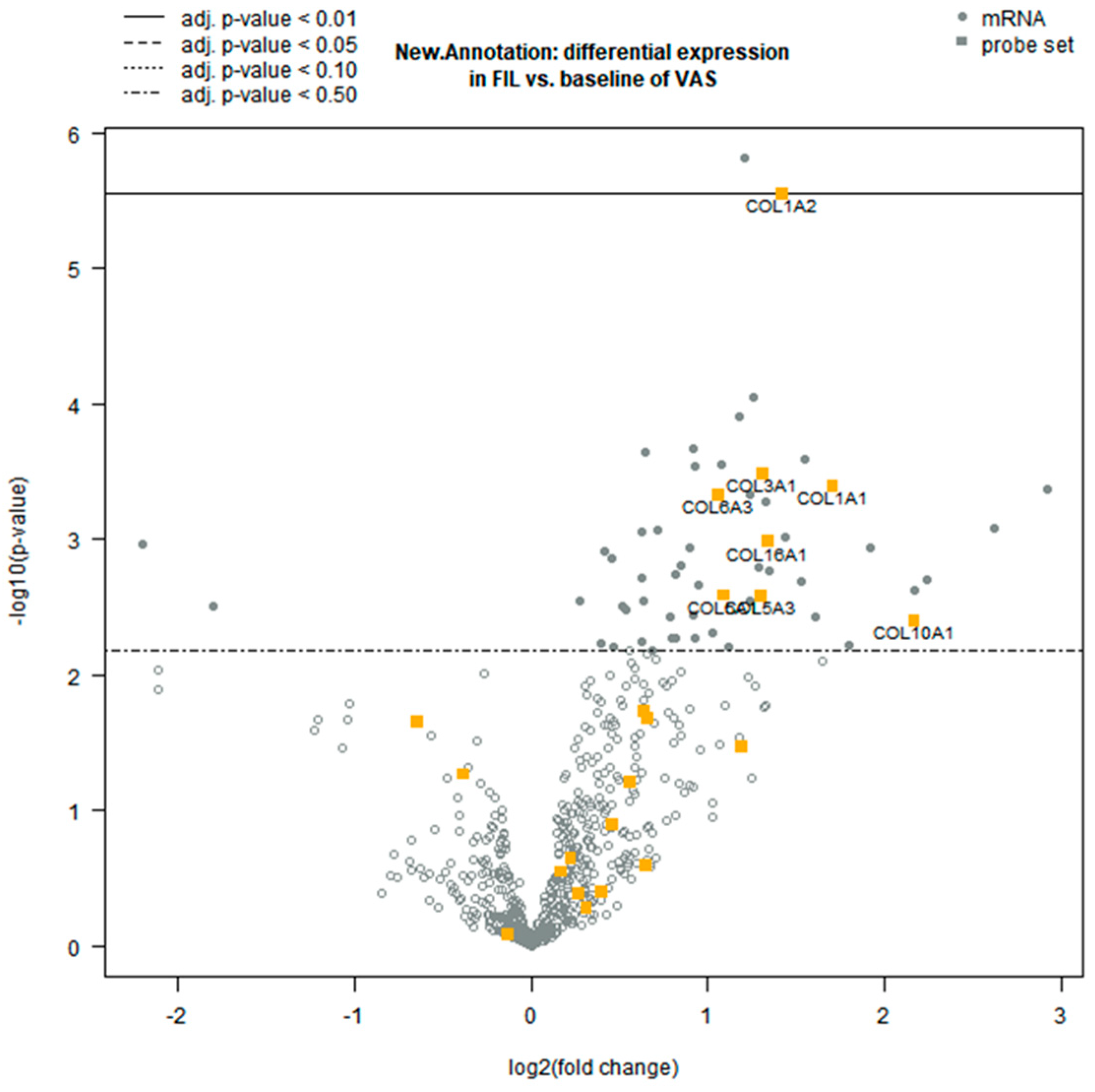

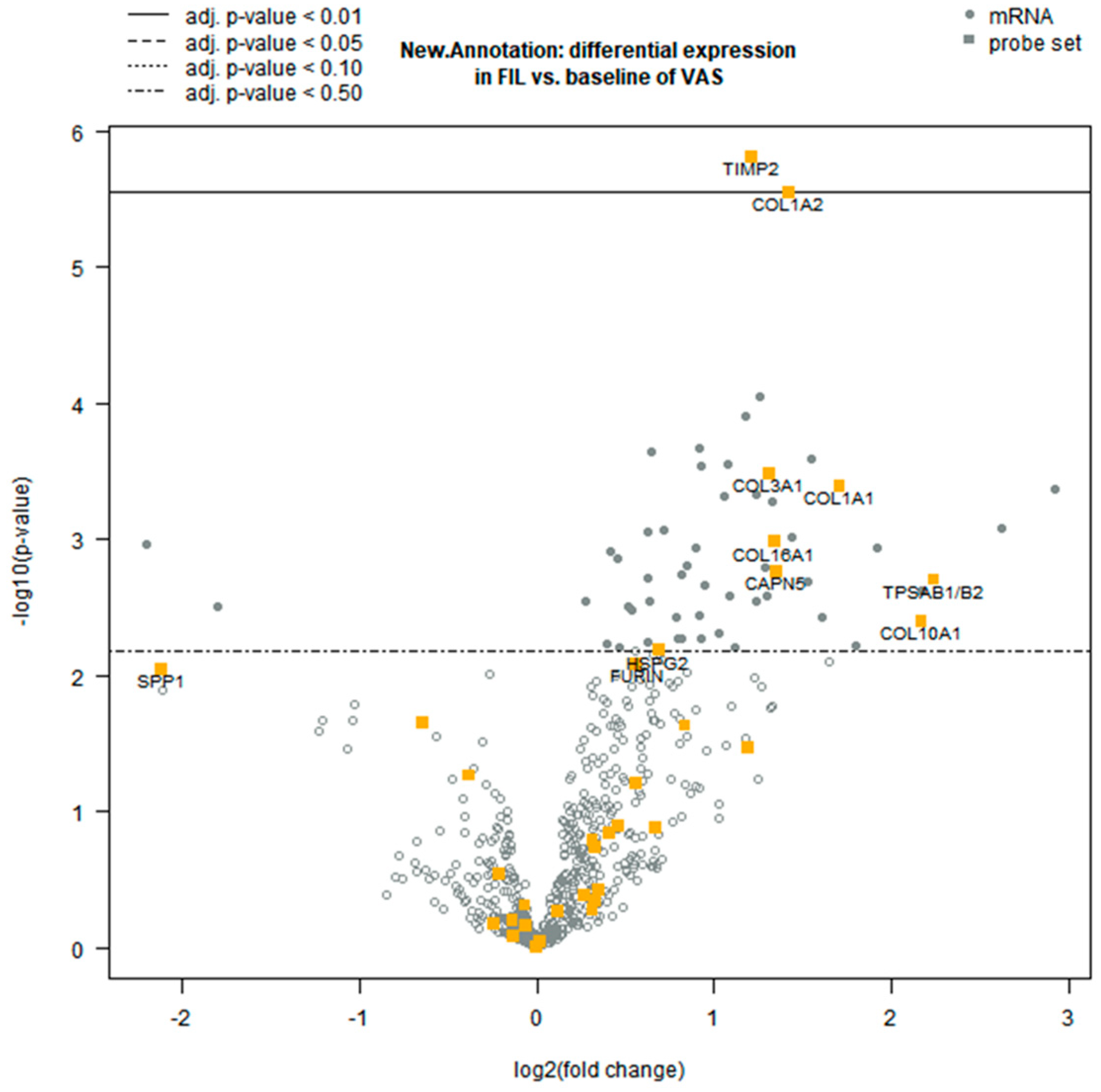

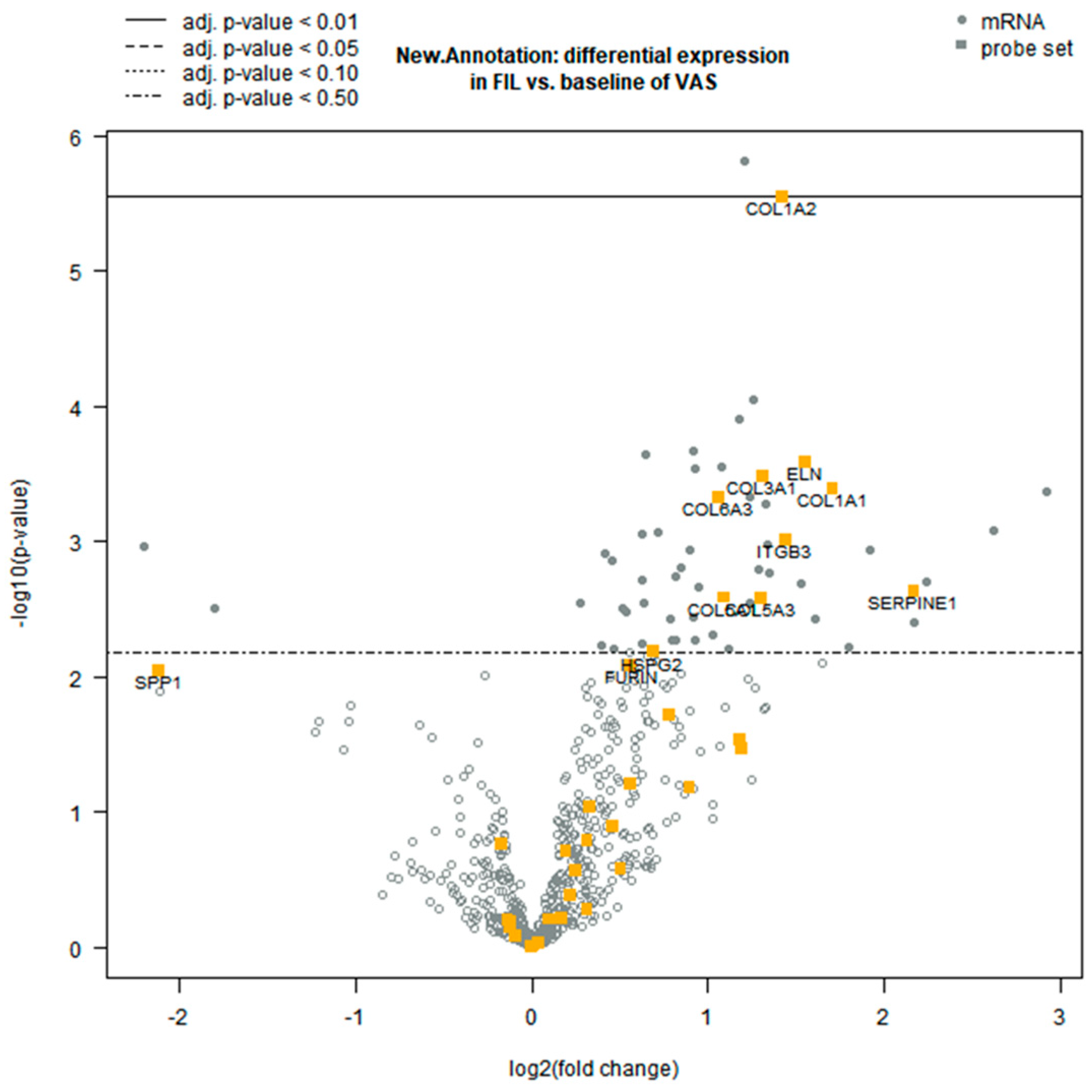

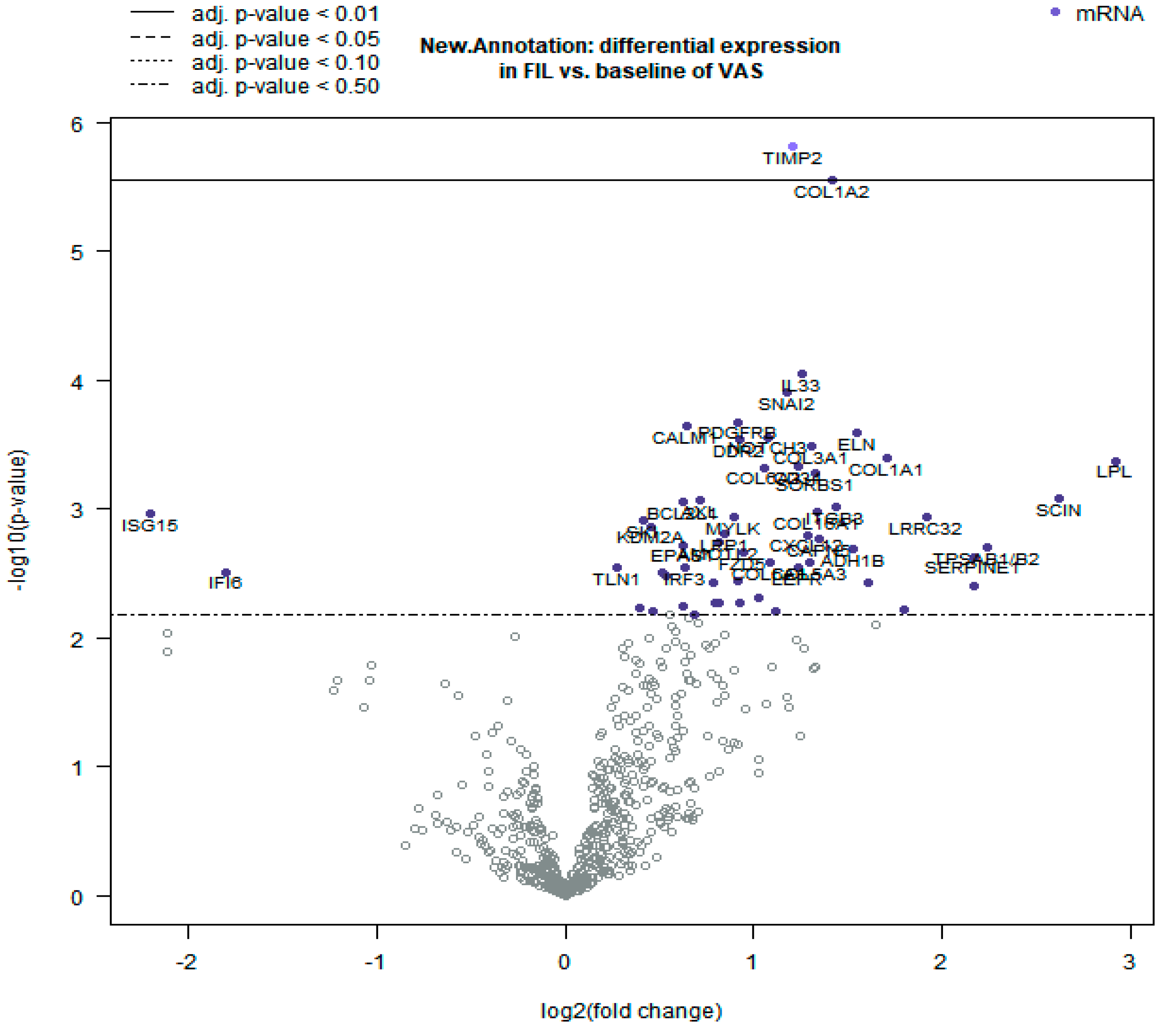

3.2. Differential Gene Expression Analysis

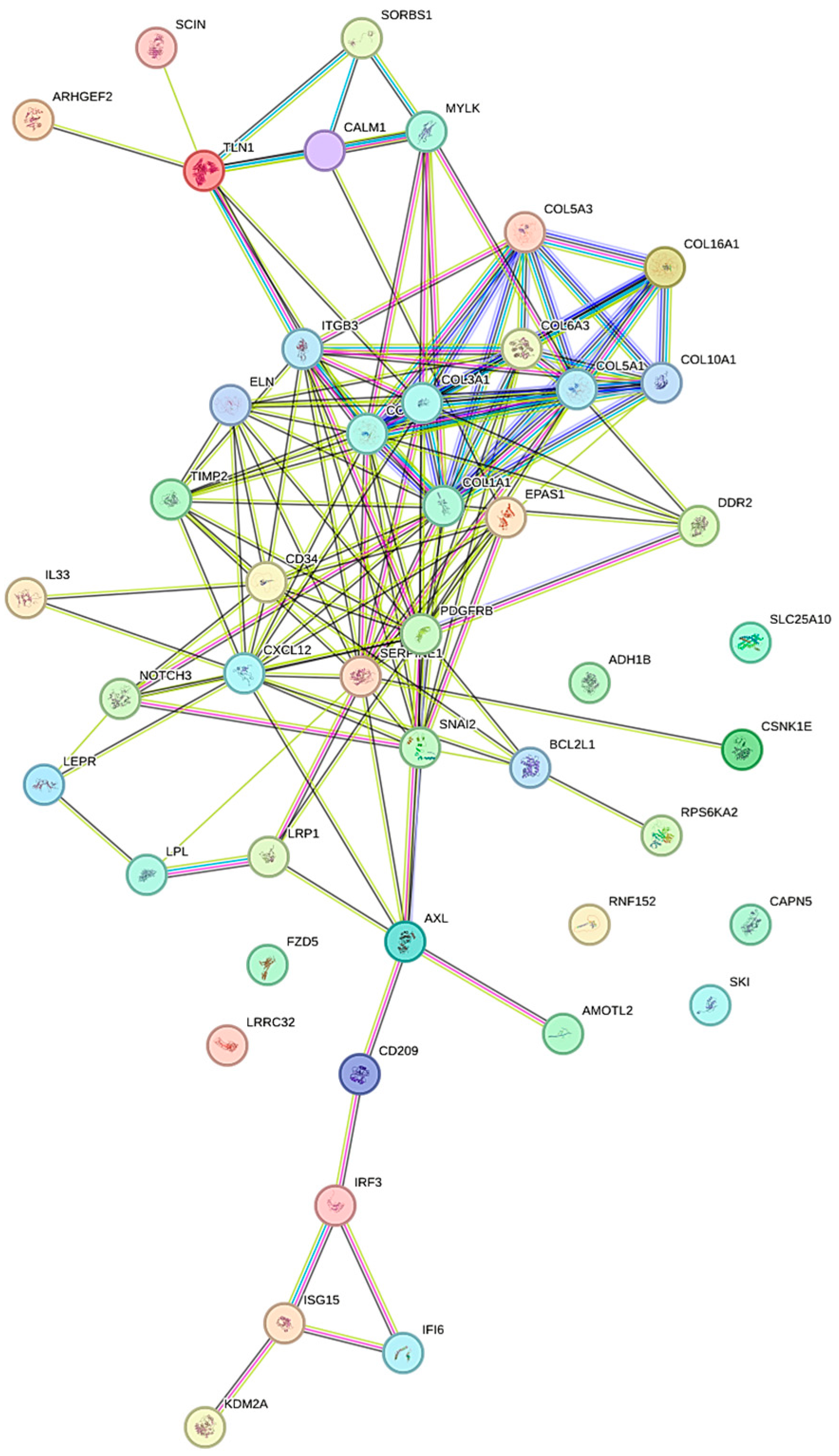

3.3. Functional Clustering Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BY | Benjamini–Yekutieli |

| COL1A1 | Collagen type I alpha 1 |

| COL1A2 | Collagen type I alpha 2 |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| EMT | Epithelial–mesenchymal transition |

| ETE | Extra-thyroid extension |

| FFPE | Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded |

| FTC | Follicular thyroid cancer |

| IEFVPTC | Invasive encapsulated follicular variant of papillary thyroid cancer |

| IFVPTC | Infiltrative follicular variant of papillary thyroid cancer |

| MMPs | Metalloproteinases |

| PTC | Papillary thyroid cancer |

| TME | Tumor microenvironment |

| TIMPs | Tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

Appendix A

References

- Basolo, F.; Macerola, E.; Poma, A.M.; Torregrossa, L. The 5th edition of WHO classification of tumors of endocrine organs: Changes in the diagnosis of follicular-derived thyroid carcinoma. Endocrine 2023, 80, 470–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, C.K.; Bychkov, A.; Kakudo, K. Update from the 2022 World Health Organization Classification of Thyroid Tumors: A Standardized Diagnostic Approach. Endocrinol. Metab. 2022, 37, 703–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baloch, Z.W.; Asa, S.L.; Barletta, J.A.; Ghossein, R.A.; Juhlin, C.C.; Jung, C.K.; LiVolsi, V.A.; Papotti, M.G.; Sobrinho-Simões, M.; Tallini, G.; et al. Overview of the 2022 WHO Classification of Thyroid Neoplasms. Endocr. Pathol. 2022, 33, 27–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Classification of Tumours Editorial Board: Endocrine and Neuroendocrine Tumours, 5th ed.; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2022; Volume 8. [Google Scholar]

- Christofer Juhlin, C.; Mete, O.; Baloch, Z.W. The 2022 WHO classification of thyroid tumors: Novel concepts in nomenclature and grading. Endocr.-Relat. Cancer 2022, 30, e220293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wang, X.; Dou, H.; Yu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, S.; Xiao, M. Extracellular matrix remodeling in tumor progression and immune escape: From mechanisms to treatments. Mol. Cancer 2023, 22, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Walker, C.; Mojares, E.; Del Río Hernández, A. Role of Extracellular Matrix in Development and Cancer Progression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sangaletti, S.; Chiodoni, C.; Tripodo, C.; Colombo, M.P. The good and bad of targeting cancer-associated extracellular matrix. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2017, 35, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niland, S.; Riscanevo, A.X.; Eble, J.A. Matrix Metalloproteinases Shape the Tumor Microenvironment in Cancer Progression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 23, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Huang, C.; Yang, X.; Han, L.; Fan, Z.; Liu, B.; Zhang, C.; Lu, T. The prognostic potential of alpha-1 type I collagen expression in papillary thyroid cancer. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019, 515, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugen, B.R.; Alexander, E.K.; Bible, K.C.; Doherty, G.M.; Mandel, S.J.; Nikiforov, Y.E.; Pacini, F.; Randolph, G.W.; Sawka, A.M.; Schlumberger, M.; et al. 2015 American Thyroid Association Management Guidelines for Adult Patients with Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer: The American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Thyroid 2016, 26, 1–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Sheng, C.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, K. Global burden of thyroid cancer in 2022: Incidence and mortality estimates from GLOBOCAN. Chin. Med. J. 2024, 137, 2567–2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintero-Fabián, S.; Arreola, R.; Becerril-Villanueva, E.; Torres-Romero, J.C.; Arana-Argáez, V.; Lara-Riegos, J.; Ramírez-Camacho, M.A.; Alvarez-Sánchez, M.E. Role of Matrix Metalloproteinases in Angiogenesis and Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivković, I.; Limani, Z.; Jakovčević, A.; Huić, D.; Prgomet, D. Role of Matrix Metalloproteinases and Their Inhibitors in Locally Invasive Papillary Thyroid Cancer. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 3178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocco, D.; Marotta, V.; Palumbo, D.; Vitale, M. Inhibition of Metalloproteinases-2, -9, and -14 Suppresses Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma Cell Migration and Invasion. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Brew, K.; Nagase, H. The tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs): An ancient family with structural and functional diversity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2010, 1803, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Sun, W.; Qin, Y.; Wu, C.; He, L.; Zhang, T.; Shao, L.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, P. Knockdown of KDM1A suppresses tumour migration and invasion by epigenetically regulating the TIMP1/MMP9 pathway in papillary thyroid cancer. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2019, 23, 4933–4944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Brew, K.; Dinakarpandian, D.; Nagase, H. Tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases: Evolution, structure and function. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2000, 1477, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H. Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) as a Cancer Biomarker and MMP-9 Biosensors: Recent Advances. Sensors 2018, 18, 3249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang, F.; Li, J.; Xu, J.; Jiang, X.; Chen, S.; Nasser, Q.A. Circular RNA circLIFR suppresses papillary thyroid cancer progression by modulating the miR-429/TIMP2 axis. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 150, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Costanzo, L.; Soto, B.; Meier, R.; Geraghty, P. The Biology and Function of Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinase 2 in the Lungs. Pulm. Med. 2022, 2022, 3632764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yabluchanskiy, A.; Ma, Y.; Iyer, R.P.; Hall, M.E.; Lindsey, M.L. Matrix metalloproteinase-9: Many shades of function in cardiovascular disease. Physiology 2013, 28, 391–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, D.; Kassiri, Z. Biology of Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinase 3 (TIMP3), and Its Therapeutic Implications in Cardiovascular Pathology. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, P.K.; Metreveli, N.; Tyagi, S.C. MMP-9 gene ablation and TIMP-4 mitigate PAR-1-mediated cardiomyocyte dysfunction: A plausible role of dicer and miRNA. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2010, 57, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez-Barrantes, S.; Shimura, Y.; Soloway, P.D.; Sang, Q.A.; Fridman, R. Differential roles of TIMP-4 and TIMP-2 in pro-MMP-2 activation by MT1-MMP. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2001, 281, 126–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valacca, C.; Tassone, E.; Mignatti, P. TIMP-2 Interaction with MT1-MMP Activates the AKT Pathway and Protects Tumor Cells from Apoptosis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0136797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ding, Y.; Li, A. Identification of COL1A1 and COL1A2 as candidate prognostic factors in gastric cancer. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2016, 14, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; He, Y.; Wang, W. ceRNAnetwork-regulated COL1A2 high expression correlates with poor prognosis and immune infiltration in colon adenocarcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 16932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.; Horn, G.; Moulton, K.; Oza, A.; Byler, S.; Kokolus, S.; Longacre, M. Cancer development, progression, and therapy: An epigenetic overview. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 21087–21113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shakib, H.; Rajabi, S.; Dehghan, M.H.; Mashayekhi, F.J.; Safari-Alighiarloo, N.; Hedayati, M. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in thyroid cancer: A comprehensive review. Endocrine 2019, 66, 435–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Liu, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Ruan, X.; Tao, M.; Lin, W.; Liu, C.; Chen, H.; Liu, H.; Wu, Y. Prognostic value of EMT-related genes and immune cell infiltration in thyroid carcinoma. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1463258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Roy, R.; Morad, G.; Jedinak, A.; Moses, M.A. Metalloproteinases and their roles in human cancer. Anat. Rec. 2020, 303, 1557–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Xu, L.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Ren, T.; Liu, H. Pan-cancer analysis of the prognostic and immunological role of matrix metalloproteinase 9. Medicine 2023, 102, e34499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Li, Z.; Wei, J.; Chen, B.; Wang, Y.; Yang, S.; Wu, K.; Meng, X. The Role of MMP-9 and MMP-9 Inhibition in Different Types of Thyroid Carcinoma. Molecules 2023, 28, 3705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Li, G.; Jiang, W.; Kang, Y.; Yu, X.; Zhang, C.; Feng, Y. High expression of collagen 1A2 promotes the proliferation and metastasis of esophageal cancer cells. Ann. Transl. Med. 2020, 8, 1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giani, C.; Torregrossa, L.; Ramone, T.; Romei, C.; Matrone, A.; Molinaro, E.; Agate, L.; Materazzi, G.; Piaggi, P.; Ugolini, C.; et al. Whole Tumor Capsule Is Prognostic of Very Good Outcome in the Classical Variant of Papillary Thyroid Cancer. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 106, e4072–e4083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample ID | IEFVPTC/IFVPTC | Tumor Location | Size | Type of inv/inf | Embolism | nr Embolisms | TNM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VAS1 | IEFVPTC | lobe sx | 3.8 cm | CN | N | 0 | pT2(m)N0Mx |

| VAS6 | IEFVPTC | lobe sx | 0.7 cm | CN, foc IP | Y | 1 | pT1a(m)NxMx |

| VAS8 | IEFVPTC | lobe dx | 5 cm | CN | Y | 1 | pT3aNxMx |

| VAS2 | IEFVPTC | lobe sx | 1.5 cm | CN | N | 0 | pT1bNxMx |

| VAS3 | IEFVPTC | lobe dx | 0.5 cm | CN | N | 0 | pT2(m)N0Mx |

| VAS4 | IEFVPTC | isthmus | 3.5 cm | CN, IP, CT | N | 0 | pT2NxMx |

| VAS5 | IEFVPTC | lobe dx | 4.5 cm | CN | Y | 4 | pT3aNxMx |

| VAS7 | IEFVPTC | lobe sx | 3 cm | CN | N | 0 | pT2NxMx |

| VAS9 | IEFVPTC | lobe dx | 1.8 cm | CN, foc IP | Y | <4 | pT1b(m)NxMx |

| VAS10 | IEFVPTC | lobe sx | 2.2 cm | CN | N | 0 | pT2NxMx |

| VAS11 | IEFVPTC | lobe sx | 2.7 cm | CN | Y | >4 | pT2(m)N1aMx |

| VAS12 | IEFVPTC | lobe dx | 1.7 cm | CN | N | 0 | pT1bNxMx |

| VAS13 | IEFVPTC | lobe sx | 2.7 cm | CN | N | 0 | pT2NxMx |

| FIL2 | IFVPTC | lobe dx | 1.4 cm | IP, TL | Y | >4 | pT1b(m)N1aMx |

| FIL1 | IFVPTC | lobe sx | 0.7 cm | IP | N | 0 | pT1aNxMx |

| FIL3 | IFVPTC | lobe dx | 2.5 cm | IP | N | 0 | pT2(m)NxMx |

| FIL5 | IFVPTC | lobe dx | 0.8 cm | TL | Y | >4 | pT1b(m)N1bMx |

| FIL6 | IFVPTC | lobe sx | 3.6 cm | IP, TL | Y | >4 | pT2(m)N1bMx |

| FIL7 | IFVPTC | lobe dx | 1.5 cm | IP | N | 0 | pT1bN0Mx |

| FIL8 | IFVPTC | lobe dx | 1 cm | IP, CT | N | 0 | pT1a(m)N1aMx |

| FIL4 | IFVPTC | lobe dx | 1 cm | TL | Y | 4 | pT1a(m)N1bMx |

| FIL9 | IFVPTC | lobe sx | 0.3 cm | IP | N | 0 | pT1aNxMx |

| FIL10 | IFVPTC | lobe sx | 1.5 cm | IP, CT | N | 0 | pT1bNxMx |

| FIL11 | IFVPTC | lobe dx | 0.6 cm | IP, TL | Y | <4 | pT1a(m)N1bMx |

| FIL12 | IFVPTC | lobe dx | 0.6 cm | IP | N | 0 | pT1aNxMx |

| FIL13 | IFVPTC | lobe dx | 0.4 cm | IP | N | 0 | pT1aNxMx |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sparavelli, R.; Giannini, R.; Boldrini, L.; Fuochi, B.; Proietti, A.; Signorini, F.; Torregrossa, L.; Materazzi, G.; Ugolini, C. Molecular Differences in Invasive Encapsulated Follicular Variant of Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma (IEFVPTC) and Infiltrative Follicular Variant of Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma (IFVPTC): The Role of Extracellular Matrix. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1666. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121666

Sparavelli R, Giannini R, Boldrini L, Fuochi B, Proietti A, Signorini F, Torregrossa L, Materazzi G, Ugolini C. Molecular Differences in Invasive Encapsulated Follicular Variant of Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma (IEFVPTC) and Infiltrative Follicular Variant of Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma (IFVPTC): The Role of Extracellular Matrix. Biomolecules. 2025; 15(12):1666. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121666

Chicago/Turabian StyleSparavelli, Rebecca, Riccardo Giannini, Laura Boldrini, Beatrice Fuochi, Agnese Proietti, Francesca Signorini, Liborio Torregrossa, Gabriele Materazzi, and Clara Ugolini. 2025. "Molecular Differences in Invasive Encapsulated Follicular Variant of Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma (IEFVPTC) and Infiltrative Follicular Variant of Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma (IFVPTC): The Role of Extracellular Matrix" Biomolecules 15, no. 12: 1666. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121666

APA StyleSparavelli, R., Giannini, R., Boldrini, L., Fuochi, B., Proietti, A., Signorini, F., Torregrossa, L., Materazzi, G., & Ugolini, C. (2025). Molecular Differences in Invasive Encapsulated Follicular Variant of Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma (IEFVPTC) and Infiltrative Follicular Variant of Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma (IFVPTC): The Role of Extracellular Matrix. Biomolecules, 15(12), 1666. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121666