Abstract

Auger decay of all levels of the double core-hole states of Xe2+, including collective Auger decay (CAD) pathways, is investigated using the relativistic distorted-wave approximation. Large-scale configuration interaction calculations were performed to obtain level-to-level Auger decay rates. In addition to the typical Auger decay final levels associated with the configurations of , , and , evident contributions are identified from excited channels, leading to configurations such as , , , and . These contributions arise from strong electron correlation between the valence electronic orbitals and the inner-shell orbital. The CAD rates and branching ratios (BRs) are determined for each double core-hole level with a minimum CAD BR of 1.28% and a maximum of 4.08% among all CAD channels. The configuration-averaged CAD BR is predicted to be 1.93%, which helps explain recent unexplained experimental findings. The inclusion of CAD processes enriches Auger electron spectroscopy, thereby extending potential applications of this important experimental tool in both fundamental and applied research.

1. Introduction

The collision of X-ray or extreme ultraviolet photons or charged particles with an atom or a molecule can lead to the formation of inner-shell vacancy states. These excited states subsequently relax via Auger or radiative decay processes. Normal Auger decay, also referred to as single Auger decay, involves two electron transitions: an inner-shell vacancy is filled by an electron, while another electron is ejected into the continuum state [1]. Higher-order weak Auger processes, including direct double Auger decay [2,3,4,5,6,7] and direct triple Auger decay [8], are also known. In direct double or triple Auger decay, a single inner-shell vacancy is filled, leading to the simultaneous emission of two or three electrons into the continuum, respectively. Theoretical formalisms have been developed to address these complicated many-body Coulomb interactions involved in direct double and triple Auger decay (e.g., see [9,10,11]).

Double core hole (DCH) states, or so-called hollow states, represent unique systems in which two inner-shell electrons have been removed. They can be routinely generated by interaction of ultra-intense X-ray pulses or particle beams with atoms, molecules, clusters, and solids [12,13,14,15,16]. In such DCH states, a less common Auger decay may occur wherein two outer-shell electrons simultaneously fill the double vacancies while releasing only a single Auger electron [17]. This mechanism is known as collective Auger decay (CAD), which has also been termed as three-electron Auger decay or two-electron–one-electron Auger decay. Further details on different CAD transitions can be found in reference [17]. Spectroscopy related to DCH or hollow states is sensitive to the local chemical environment, making it a powerful tool for chemical analysis [18,19], diagnosing laser pulse intensity and duration [20,21], and other practical applications [22,23]. For instance, Auger electron spectroscopy (AES) is widely employed in various research fields for both fundamental and applied sciences.

Experimental evidence of CAD was first reported in the Auger decay of double core-hole Ar4+ , produced via ion–atom collisions [24]. Subsequent studies observed CAD signals using different experimental techniques, including slow ion–surface collision, beam–foil excitation, and more advanced approaches based on synchrotron radiation [25,26,27,28,29,30,31]. In these experiments, the branching ratios (BRs) of CAD pathways were found to fall within the range of 10−3–10−4. Theoretically, Ivanov et al. [32] calculated CAD rates of double K-shell vacancy state in Li-like ions using first-order perturbation theory with respect to the interelectron interaction. They derived a simple scaling of the CAD rate on the atomic number Z, predicting a CAD BR of 7.0 × 10−4, 2.1 × 10−4, and 2.3 × 10−4 for the state in Li, C, and N ions, respectively. Simons et al. [33] employed many-body perturbation theory with LS-coupled intermediate states to calculate CAD rates for state in atomic Li, obtaining a CAD BR of 8.0 × 10−4 for this K-shell vacancy state. The discrepancy between their results and that of Ivanov et al. [32] was attributed to more complete inclusion of electronic correlation in the initial state. Amusia and Lee [34] investigated correlated Auger decay involving two vacancies in atoms, including of Ne, of Ar, and of Kr. Marques et al. [35] theoretically predicted a CAD BR on the order of 1 × 10−7 for the L-shell of Li-like Kr, Nb and Gd ions, which is significantly smaller than those for atomic Li and lower charged Li-like ions [32,33]. Feifel et al. [36] reported that the CAD ratio of a double inner-valence vacancy is orders of magnitude larger than that of a double inner-shell vacancy.

Very recently, Hikosaka and Fritzsche [37] experimentally investigated the CAD of Xe2+ DCH states using the multi-electron-ion coincidence spectroscopy technique. In this process, two outer-shell electrons fill the double vacancies, releasing a third energetic Auger electron. They measured the CAD BR relative to the total Auger emission from Xe2+ states to be 2% ± 1%, which is an order of magnitude larger than the BRs reported previously. The authors suggested that CAD plays a more pivotal role in the relaxation of core-excited states than previously recognized. To explain CAD in Xe2+ DCH states, the authors analyzed the Auger rate connecting the initial and final states. The CAD process involves the coordinated transition of three electrons—a mechanism that yields a vanishing amplitude in the standard first-order treatment if the electronic correlation effect was not considered. To substantiate their experimental findings, the authors analyzed the level structures and energies of intermediate states. However, for many-electron atoms like Xe, quantitative theoretical studies of the CAD rates and BRs are still lacking, and the detailed CAD pathways have still not been identified.

In this work, we present a theoretical investigation into the Auger decay of Xe2+ DCH states, including CAD pathways within the distorted wave approximation. Large-scale configuration interaction (CI) calculations were performed to yield accurate level-to-level Auger decay rates and AES. The calculated CAD BR demonstrates good agreement with the experimental measurement [37].

2. Results

The Auger decay process, in particular the CAD pathways, is entirely due to electron-electron interactions. Therefore, an accurate determination of the Auger decay rates necessitates the inclusion of CI [9,10,11,38,39,40,41]. For investigation of the Auger decay of the double inner-shell vacancy states with the configuration of Xe2+, we incorporated electronic correlation among fine-structure levels from a comprehensive set of configurations, including: , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , ( = , , , , , , , , , and , and = , , and ).

Table 1 lists the nine levels of configuration in Xe2+ with the calculated level energies relative to the Xe2+ ground level , along with the Auger decay rates and full widths at half maximum obtained by inclusion of the full CI described in the above. As shown, the relative energies of these double inner-shell vacancy states range from 118 eV to 130 eV. Among them, the Auger decay rate is smallest for the lowest-energy level with an Auger decay rate of 1.218 × 1014 s−1 and the largest for the highest-level with a rate of 2.827 × 1014 s−1. Notably, the Auger decay rate does not increase monotonically with level energy.

Table 1.

Level energies (eV) relative to the Xe2+ ground level , total Auger decay rate (s−1) and full width at half maximum (meV) for all fine-structure levels of the Xe2+ double inner-shell vacancy configuration. Numbers in square brackets denote powers of ten. Four calculations with different CI in Auger initial states were carried out to show the convergence of energy levels and Auger decay rates: full CI described in the text, only the ground and double vacancy configurations (A), correlation from double electron excitation of configuration to orbitals of , , , , , , , , , and (B), and further CI from double electron excitation of configuration (C).

The electron correlations included in both initial and final levels in Auger decay described in the above should obtain, in principle, converged results such as level energies and Auger decay rates as CI from exceeding one hundred thousand levels has been considered in the calculation. To check the convergence, we carried out three more separate investigations with different degree of CI in addition to the full CI calculation. Because the Auger finals of all pathways (full CI) have to be included to obtain correct Auger decay rates, we consider different degree of CI in Auger initial states to simplify our discussion. In case A we include only the ground and double vacancy configurations in the electron correlations of the initial levels. In case B, more correlations are considered from double electron excitation of configuration to orbitals of , , , , , , , , , and . The last case C includes further CI from double electron excitation of configuration. Converged level energies and Auger decay rates can be obtained by continuously inclusion of more configurations from case A to B and from B to C.

The Auger decay rates listed in Table 1 are derived by summing over all possible decay channels. Representative dominant decay channels with decay rates larger than s−1 are given in Table 2 for the lowest-energy level of No. 1 and highest-energy level No. 9 in Table 1. For initial level No. 1, , the dominant Auger transitions correspond to final states in the and configurations, with Auger electron energies in the ranges of 24–30.4 eV and 12.5–16.5 eV, respectively. The strongest decay channel originates from +eAuger; It has an Auger decay rate of s−1. For the higher-lying level (level No. 9), Auger electron energies for final states in and shift to higher energy ranges of 33–38 eV and 21.4–25.3 eV, respectively. Moreover, for this initial level, decay to becomes significantly stronger than the level (level No. 1). More importantly, a CAD channel, +eAuger, emerges with a rate of s−1, comparable in AES intensity to normal decay channels. The Auger electron energy of this CAD channel is 83.08 eV, substantially higher than those of the normal Auger decay to , , and configurations.

Table 2.

Auger final levels, Auger electron energies (eV), and decay rates (s−1) for the lowest- and highest-energy initial levels (No. 1 and No. 9 in Table 1) of the Xe2+ double inner-shell vacancy states. Only channels with decay rates exceeding s−1 are listed here. Numbers in square brackets denote powers of ten.

A clear distinction in Auger decay behavior is evident from Table 2 for the initial levels (No. 1) and (No. 9). For the lowest-energy level (No. 1), all stronger decays correspond to normal Auger decay channels, with final levels belonging to , , and configurations. In contrast, for the highest-energy level (No. 9), numerous correlation-assisted channels where one electron is promoted to a valence orbitals such as , , or , exhibiting decay rates comparable to those of the dominant normal Auger decay channels. For examples, the Auger decay rates from level No. 9 to final levels such as , , , , , and are predicted to be , , , , , and s−1, respectively. They are of similar intensity to the normal Auger decay channels of , , and states.

To further clarify the Auger decay pathways, the level-to-level Auger decay rates and BRs were summed to obtain level-to-configuration rates in Table 3. The results indicate that decay into configuration constitutes a significant pathway for all double inner-shell vacancy states . Similarly, decay into configuration is dominant for most levels, with the exception of level No. 2 , which exhibits a lower BR of 1.88%. However, decay into configuration contributes a significant BR for most levels, with the notable exceptions of level No. 1 and No. 2 . Beyond these normal Auger decay channels to , , and , several excited configurations, such as , , , and , also contribute evidently to the total Auger decay rates.

Table 3.

Level-to-configuration Auger decay rates (s−1) and branching ratios (BRs, %) for dominant decay channels from the nine fine-structure levels of Xe2+ double inner-shell vacancy configuration. Level numbers (1–9) correspond to those listed in Table 1. Numbers in square brackets represent powers of ten.

In what follows, we focus on the CAD rates and BRs for Xe2+ double inner-shell vacancy states. Following the format of Table 3, Table 4 presents the level-to-configuration rates and BRs especially for CAD channels, where two outer electrons from the or orbitals simultaneously fill the two vacancies. As can be seen from Table 4, level No. 1 has a minimal CAD BR of 1.28% while the level No. 9 has a maximal CAD BR of 4.08% among all the DCH states. To illustrate the composition of the CAD BRs, we consider level No. 9 as a representative example. The total CAD rate for this level primarily arises from transitions to final configurations , , and , which contribute approximately 33%, 36%, and 8.9%, respectively. Statistical averaging over all nine levels of configuration yields a mean CAD BR of 1.93%, which is in good agreement with the experimental measurement of 2% ± 1% reported by Hikosaka and Fritzsche [37].

Table 4.

Level-to-configuration Auger decay rates (s−1) and BRs (in percent %) for dominant CAD channels from the nine fine-structure levels of the Xe2+ double inner-shell vacancy configuration. Level numbers (1–9) correspond to those listed in Table 1. Numbers in square brackets represent powers of ten.

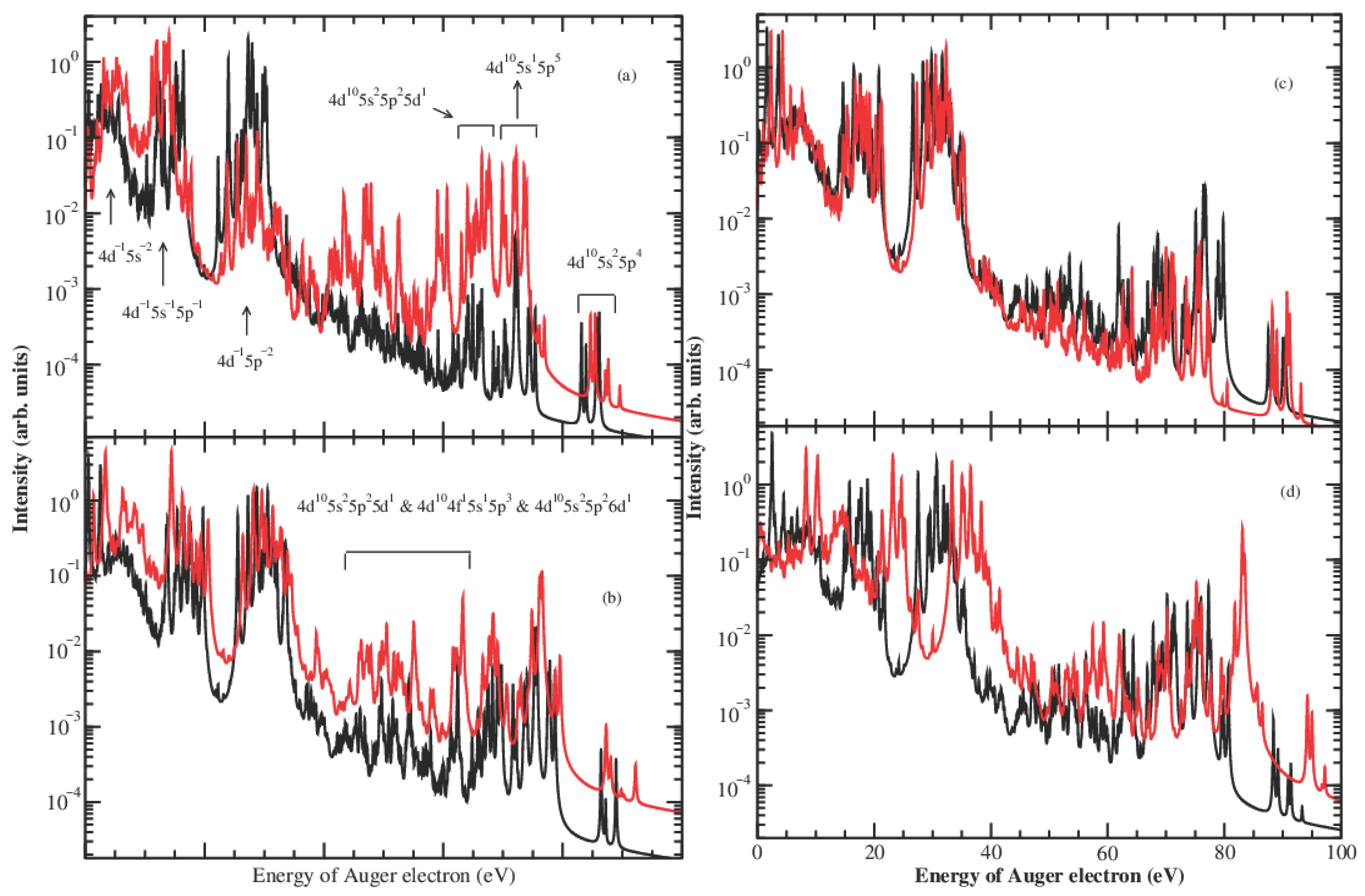

The complete picture of Auger decay including CAD processes is summarized in Figure 1, which shows the AES of the DCH states of Xe2+. The AES shows a consistent spectral pattern across all DCH levels: the normal decay channels to , , and configurations appear at Auger electron energies below 40 eV, whereas the CAD channels emerge above 40 eV. The three dominant structures in AES associated with these normal decay channels to states of configurations of , , and are labeled in Figure 1a with descending Auger electron energy, respectively. The CAD spectral structures, corresponding to transitions into , , , , and configurations, are indicated in panels (a) and (b), with ascending energy of Auger electron, respectively. These designations of Auger decay channels apply to AES of all levels shown in Figure 1. As shown, for Auger decay of each level of of Xe2+, the production of Xe3+ ground-state levels is much weaker than that of transitions to the excited levels of , , , and . These spectral features in AES are markedly different from the CAD behavior observed in DCH states of Ar , where the dominant Auger final states are the Ar ground-state levels [31].

Figure 1.

Auger electron spectroscopy of Xe2+ double inner-shell vacancy states. Panel (a) shows levels No. 1 and No. 2 ; Panel (b) shows levels No. 4 and No. 5 ; Panel (c) shows levels No. 6 and No. 7 ; And panel (d) shows levels No. 8 and No. 9 . In each plot of (a–d), the black solid line refers to the first level, and the red line to the second. Dominant Auger decay channels, including CAD processes, are labeled in panels (a,b). For clarity, the AES for level No. 3 is not shown here.

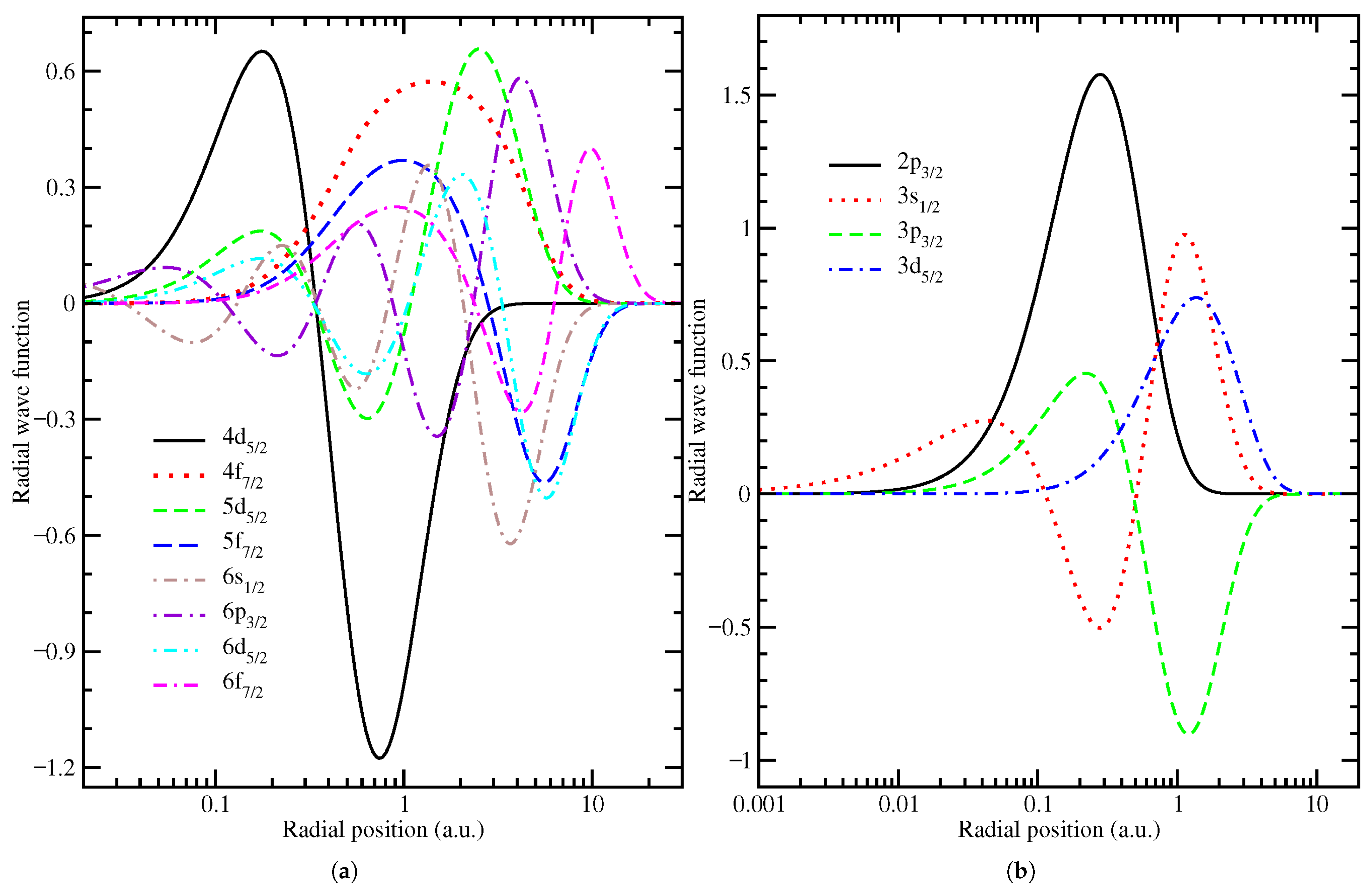

The larger BR of CAD channels observed here, compared to previous experimental [24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31] and theoretical [32,33,34,35] reports, originates from the strong electron correlation in Xe2+ ion. In addition to the angular correlation effects, the radial electron correlation can be seen from Figure 2a which shows the large components of the radial wave functions for the 4d5/2, 4f7/2, 5d5/2, 5f7/2, 6s1/2, 6p3/2, 6d5/2, and 6f7/2 electron orbitals of Xe2+ ion. A substantial spatial overlap is observed between the radial wave functions of 4d5/2 orbital and those of 4f7/2, 5d5/2, 5f7/2, 6s1/2, 6p3/2, 6d5/2, and 6f7/2 electron orbitals. Similar electron correlation is found between the valence electron orbitals and 4d3/2 inner-shell orbital, which explains the CAD BR of ∼2% in Xe2+, approximately an order of magnitude larger than values previously reported.

Figure 2.

(Color online) (a) Large-components radial wave functions of the , , , , , , , and electron orbitals of Xe2+ ion, illustrating the significant spatial overlap between the inner-shell orbital and various valence electron orbitals that enhances the collective Auger decay probability. (b) Large-components radial wave functions of the , , , and electron orbitals of Ar2+ ion, illustrating the spatial overlap between the inner-shell and various valence electron orbitals, which governs the comparatively weaker collective Auger decay probability in argon.

The BR of CAD pathways of DCH states of Ar has been measured experimentally as 1.9 × 10−3 ± 1.0 [31] and calculated theoretically to be 1.0 × 10−3 [30], which is much smaller than that of of Xe2+ with a value of ∼2%. Such a large difference in CAD BR between Ar2+ and Xe can be seen by comparing their respective radial wave functions of the relevant electronic orbitals of Ar2+ shown in Figure 2b and Xe2+ shown in Figure 2a. Obviously, the radial correlations between the valence electron orbitals (, , , , , , and ) and the inner-shell orbital in Xe2+ are much stronger than those between the , , and orbitals and inner-shell orbital in Ar2+ ion.

DCH or even multiple core-hole states are routinely generated in the interaction of extreme ultraviolet and X-ray free-electron lasers with Xe [42,43]. As an example, the pathway has been found to contribute substantially to the formation of Xe+4 via two-photon ionization under intense extreme ultraviolet free electron laser radiation [42]. Hikosaka et al. have investigated double photoionization leading to DCH states in Xe, which were identified by the observed Auger spectra [44]. In view of the evident BR of CAD pathways of DCH states of in Xe2+ reported in this work, it is necessary to include CAD in any comprehensive analysis of Auger decay process in such systems.

It is well-known that the AES is a well-established experimental tool in a variety of research fields for both fundamental and applied sciences [45,46,47,48,49,50,51]. As pointed out by Hikosaka and Fritzsche [37], the increasing relevance of CAD in the relaxation of DCH states in heavy elements suggests that the CAD processes should be considered in AES. However, quantitative studies remain limited, largely due to the theoretical challenges associated with modeling multi-electron CAD transitions. Explicitly including CAD pathways in AES analysis can provide deeper insight into the electronic structure of the target system and enhance the utility of AES as a probe of collective electron behavior in atoms and molecules. Considering that DCH states can be efficiently produced in materials irradiated by intense extreme ultraviolet and X-ray free-electron laser pulses, it is crucial to account for CAD in the relaxation dynamic of these excited states, especially in heavy element materials.

3. Theoretical Methods

The electronic structure of an ion is obtained by diagonalizing the Dirac Coulomb Hamiltonian to solve the wave function (atomic units are used here unless otherwise specified) [52]:

where N denotes the number of bound electrons in the ion and and are the Pauli matrices. The rest energy is subtracted in Equation (1). By using the Dirac Coulomb Hamiltonian, relativistic effects are fully taken into account in the theory [52]. Higher-order quantum electrodynamics effects, including the Breit interaction in the zero-energy limit for the exchanged photon, are incorporated in the calculations.

The atomic wave function is constructed from a basis of configuration state functions (CSFs). These CSFs are antisymmetric products of N one-electron Dirac spinors

where and are the large and small components of the radial wave functions, and is a two-component spherical spinor. The quantum numbers n, and m are the principal, relativistic angular, and magnetic numbers of the electron orbital, respectively. The relativistic angular quantum number is related to the non-relativistic angular quantum number (l) and total angular quantum number (j) by . The radial wave functions and satisfy the coupled Dirac equation for a local central field within the standard Dirac–Fock–Slater method,

where denotes the fine-structure constant and is the energy eigenvalue of the one-electron orbital. Both bound and continuum electron orbitals are determined using the same local central potential of the ion, which includes contributions from the nuclear charge and the electron-electron interaction. Various electronic orbitals are assumed to be orthonormal,

The continuum orbitals are obtained by solving the Dirac equations with the same central potential as that for bound orbitals. The continuum wave function is normalized as

where is the energy of the orbital, and are the large and small components of the continuum wave function.

An atomic state is constructed from a linear combination of CSFs with the same symmetry

where is the number of CSFs and denotes the expansion coefficient. Each CSF is constructed from the common normalized eigenfunctions of the square of total angular momentum operator and the parity operator , characterized by a total angular momentum eigenvalue J and a parity eigenvalue .

In the framework of perturbation theory, the Auger decay rate from an initial state to a final state plus a continuum electron is given by [53]

where , and are the momentum, energy and relativistic angular quantum number of the Auger electron, respectively, and Z is the effective nuclear charge of the involved ion. The operator for the Auger decay rate contains Coulomb potentials of both one-electron and two-electron interaction terms.

Auger electron spectroscopy is obtained by considering all possible Auger decay pathways from the initial state i

where is line profile. Here the line width originates from the natural lifetime broadening which is usually taken as a Lorentzian profile

where is the half width at half maximum (HWHM) of the total Auger decay width for the initial state i. However, under some conditions such as an existence of giant resonances in Auger decay process, it may be difficult to properly capture the AES by using a Lorentzian profile. For a definite initial autoionizing state i, this width is obtained by summing over all possible Auger decay channels,

where ℏ denotes the reduced Planck constant.

The accuracy of the Auger decay rates presented in this work rests on the self-consistent interplay between the CI approach and the perturbation theoretical framework for transition probability. The CI procedure, as expressed in Equation (5), is responsible for constructing a quantitatively accurate representation of the many-electron wavefunctions for the initial and final states by capturing static electron correlation. These CI wavefunctions serve as the essential input for the perturbation theory calculation of the Auger matrix element in Equation (6). Perturbation theory, in turn, provides the formal framework for evaluating the transition rate between these correlated states.

This synergy is particularly crucial for capturing the CAD pathways. As a three-electron transition process, the CAD amplitude vanishes in the standard first-order perturbation theory if CI was not included. The CI expansion is fundamental here, as it not only provides an accurate description of the initial and final states but also inherently incorporates the complex electronic correlations that make these higher-order pathways possible. Thus, the large-scale CI calculations undertaken in this work are not merely for refining energies; They are indispensable for activating and quantitatively evaluating the CAD channels, which would otherwise remain inaccessible in a less sophisticated theoretical model.

4. Conclusions

In summary, the Auger decay process in Xe2+ is theoretically investigated for the DCH states , with special attention paid to the contribution of CAD. For all levels, the normal Auger decay into is consistently a dominant pathway, while transitions to and are strong for most levels of states, with the exception of one or two lower-energy DCH states. Moreover, several excited configurations, such as , , , and , contribute significantly to the Auger decay rates. For all levels of DCH states of Xe2+, we determined that the CAD BRs relative to the total Auger emission ranged from 1.28% to 4.08%, which means that the CAD pathways need to be considered in Auger decay models. The dominant CAD channels originate from excited configurations such as , , and , rather than Xe3+ ground state. The configuration averaged CAD BR is predicted to be 1.93%, showing excellent agreement with a recent experimental measurement. By incorporating CAD pathways, AES can serve as a more powerful tool for understanding collective behaviors in atomic and molecular systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Y. and J.Z.; methodology, J.Y.; software, J.Z.; validation, J.Y., A.D. and C.G.; formal analysis, J.Y.; investigation, J.Z., A.D. and G.W.; resources, J.Y.; data curation, J.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, J.Z. and A.D.; writing—review and editing, J.Y. and A.D.; visualization, A.D.; supervision, J.Y.; project administration, J.Z.; funding acquisition, J.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. 12174343, No. 12274384, and No. 11974424.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Carlson, T.A. Photoelectron and Auger Spectroscopy; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, T.A.; Krause, M.O. Experimental evidence for double electron emission in an Auger process. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1965, 14, 390–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, M.O.; Vestal, M.L.; Johnston, W.H.; Carlson, T.A. Readjustment of the neon atom ionized in the K shell by X rays. Phys. Rev. 1964, 133, A385–A390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viefhaus, J.; Cvejanovic, S.; Langer, B.; Lischke, T.; Prümper, G.; Rolles, D.; Golovin, A.V.; Grum-Grzhimailo, A.N.; Kabachnik, N.M.; Becker, U. Energy and angular distributions of electrons emitted by direct double Auger decay. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2004, 92, 083001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namba, S.; Hasegawa, N.; Nishikino, M.; Kawachi, T.; Kishimoto, M.; Sukegawa, K.; Tanaka, M.; Ochi, Y.; Takiyama, K.; Nagashima, K. Enhancement of double Auger decay probability in xenon clusters irradiated with a soft-X-ray laser pulse. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2007, 99, 043004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillemin, R.; Sheinerman, S.; Bomme, C.; Journel, L.; Marin, T.; Marchenko, T.; Kushawaha, R.K.; Trcera, N.; Piancastelli, M.N.; Simon, M. Ultrafast dynamics in postcollision interaction after multiple Auger decays in argon 1s photoionization. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 109, 013001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.; Trester, J.; Ueda, K.; Han, M.; Balčiūnas, T.; Wörner, H.J. Time-Resolved Multielectron Coincidence Spectroscopy of Double Auger-Meitner Decay Following Xe 4d Ionization. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2024, 132, 083201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, A.; Borovik, A., Jr.; Buhr, T.; Hellhund, J.; Holste, K.; Kilcoyne, A.L.D.; Klumpp, S.; Martins, M.; Ricz, S.; Viefhaus, J.; et al. Observation of a four-electron Auger process in near-K-edge photoionization of singly charged carbon ions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2015, 114, 013002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.L.; Liu, P.F.; Xiang, W.J.; Yuan, J.M. Level-to-level and total probability for Auger decay including direct double processes of Ar 2p−1 hole states. Phys. Rev. A 2013, 87, 033419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.P.; Li, Y.J.; Gao, C.; Zeng, J.L. Dominance of Double Processes in Complete Auger Decay of Rb+(3d−1). Phys. Rev. A 2020, 101, 012507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.F.; Zeng, J.L.; Yuan, J.M. A practical theoretical formalism for atomic multielectron processes: Direct multiple ionization by a single auger decay or by impact of a single electron or photon. J. Phys. B At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 2018, 51, 075202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Hoener, M.; Gessner, O.; Tarantelli, F.; Pratt, S.T.; Kornilov, O.; Buth, C.; Gühr, M.; Kanter, E.P.; Bostedt, C.; et al. Double core-hole production in N2: Beating the Auger clock. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 105, 083005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lablanquie, P.; Penent, F.; Palaudoux, J.; Andric, L.; Selles, P.; Carniato, S.; Bučar, K.; Žitnik, M.; Huttula, M.; Eland, J.H.D.; et al. Properties of hollow molecules probed by single-photon double ionization. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 106, 063003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamasaku, K.; Nagasono, M.; Iwayama, H.; Shigemasa, E.; Inubushi, Y.; Tanaka, T.; Tono, K.; Togashi, T.; Sato, T.; Katayama, T.; et al. Double core-hole creation by sequential attosecond photoionization. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2013, 111, 043001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frasinski, L.J.; Zhaunerchyk, V.; Mucke, M.; Squibb, R.J.; Siano, M.; Eland, J.H.D.; Linusson, P.; van der Meulen, P.; Salén, P.; Thomas, R.D.; et al. Dynamics of hollow atom formation in intense X-Ray pulses probed by partial covariance mapping. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2013, 111, 073002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, M.; Penent, F.; Tashiro, M.; Grozdanov, T.P.; Žitnik, M.; Carniato, S.; Selles, P.; Andric, L.; Lablanquie, P.; Palaudoux, J.; et al. Single photon K−2 and K−1K−1 double core ionization in C2H2n (n=1–3), CO, and N2 as a potential new tool for chemical analysis. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2013, 110, 163001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolorenč, P.; Averbukh, V.; Feifel, R.; Eland, J. Collective relaxation processes in atoms, molecules and clusters. J. Phys. B 2016, 49, 082001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrah, N.; Fang, L.; Murphy, B.; Osipov, T.; Ueda, K.; Kukk, E.; Feifel, R.; van der Meulen, P.; Salén, P.; Schmidt, H.T.; et al. Double-core-hole spectroscopy for chemical analysis with an intense X-ray femtosecond laser. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 16912–16915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salén, P.; van der Meulen, P.; Schmidt, H.T.; Thomas, R.D.; Larsson, M.; Feifel, R.; Piancastelli, M.N.; Fang, L.; Murphy, B.; Osipov, T.; et al. Experimental verification of the chemical sensitivity of two-site double core-hole states formed by an X-Ray free-electron laser. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 108, 153003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bostedt, C.; Bozek, J.D.; Bucksbaum, P.H.; Coffee, R.N.; Hastings, J.B.; Huang, Z.; Lee, R.W.; Schorb, S.; Corlett, J.N.; Denes, P.; et al. Ultra-fast and ultra-intense X-ray sciences: First results from the Linac Coherent Light Source free-electron laser. J. Phys. B At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 2013, 46, 164003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosmej, F.B.; Lee, R.W. Hollow ion emission driven by pulsed intense X-ray fields. Europhys. Lett. 2007, 77, 24001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cryan, J.P.; Glownia, J.M.; Andreasson, J.; Belkacem, A.; Berrah, N.; Blaga, C.I.; Bostedt, C.; Bozek, J.; Buth, C.; DiMauro, L.F.; et al. Auger electron angular distribution of double core-hole states in the molecular reference frame. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 105, 083004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Zeng, J.L.; Yuan, J.M. Single- and double-core-hole ion emission spectroscopy of transient neon plasmas produced by ultraintense X-ray laser pulses. J. Phys. B At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 2016, 49, 044001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afrosimov, V.V.; Gordeev, Y.S.; Zinov’ev, A.N.; Rasulov, D.K.; Shergin, A.P. Observation of new types of Auger transitions in atoms with two internal vacancies. JETP Lett. 1975, 21, 249–251. [Google Scholar]

- Moretto-Capelle, P.; Bordenave-Montesquieu, A.; BenoitCattin, P.; Andriamonje, S.; Andr, H. Two and three electron Auger transitions in collisions of highly-charged ions with surfaces. Z. Phys. D 1991, 21, S347–S348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkerts, L.; Das, J.; Bergsma, S.; Morgenstern, R. Three-electron Auger processes observed in collisions of bare ions on a metal surface. Phys. Lett. A 1992, 163, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.; Wehlitz, R.; Becker, U.; Amusia, M.Y. Evidence for a new class of many-electron Auger transitions in atoms. J. Phys. B 1993, 26, L41–L46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Filippo, E.; Lanzano, G.; Rothard, H.; Volant, C. Three-electron Auger process from beam-foil excited multiply charged ions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 100, 233202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eland, J.H.D.; Squibb, R.J.; Mucke, M.; Zagorodskikh, S.; Linusson, P.; Feifel, R. Direct observation of three-electron collective decay in a resonant Auger process. New J. Phys. 2015, 17, 122001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žitnik, M.; Püuttner, R.; Goldsztejn, G.; Bucar, K.; Kavčič, M.; Mihelič, A.; Marchenko, T.; Guillemin, R.; Journel, L.; Travnikova, O.; et al. Two-to-one Auger decay of a double L vacancy in argon. Phys. Rev. A 2016, 93, 021401(R). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mailhiot, M.; Jänkälä, K.; Huttula, M.; Patanen, M.; Bucar, K.; Žitnik, M.; Cubaynes, D.; Holzmeier, F.; Feifel, R.; Ceolin, D.; et al. Multielectron coincidence spectroscopy of the Ar2+ (2p−2) double-core-hole decay. Phys. Rev. A 2023, 107, 063108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, L.N.; Safronova, U.I.; Senashenko, V.S.; Viktorov, D.S. The radiationless decay of excited states of atomic systems with two K-shell vacancies. J. Phys. B 1978, 11, L175–L179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, R.L.; Kelly, H.P.; Bruch, R. Decay rates of Li I 2s22p and 2s22s. Phys. Rev. A 1979, 19, 682–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amusia, M.Y.; Lee, I.S. Correlated decay of two vacancies in atoms. J. Phys. B 1991, 24, 2617–2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, J.P.; Parente, F.; Indelicato, P.; Desclaux, J.P. Estimation of the ratio of double and single Auger transition rates for the L shell of Kr, Nb and Gd. J. Phys. B 1998, 31, 2897–2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feifel, R.; Eland, J.H.D.; Squibb, R.J.; Mucke, M.; Zagorodskikh, S.; Linusson, P.; Tarantelli, F.; Kolorenč, P.; Averbukh, V. Ultrafast molecular three-electron Auger decay. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016, 116, 073001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hikosaka, Y.; Fritzsche, S. Amplified collective Auger decay of double inner-shell vacancy in Xe. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2025, 134, 103001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.J.; Liu, L.P.; Gao, C.; Zeng, J.L.; Yuan, J.M. Auger decay including direct double processes of K-shell hollow states of Ne+ and the related hypersatellite radiative transitions. J. Electron Spectrosc. Relat. Phenom. 2018, 226, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.H.; Li, Y.J.; Liu, P.F.; Gao, C.; Wang, X.W.; Zeng, J.L. Auger decay and natural lifetime widths of single and double K-shell vacancy states of Al4+-Al11+ ions. J. Phys. B At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 2018, 51, 175001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.L.; Li, Y.J.; Liu, P.F.; Gao, C.; Yuan, J.M. Single and double K-shell resonant photoionization and Auger decay of 1s → 2p excited states of O+-O4+. Astron. Astrophys. 2017, 605, A32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zeng, J.L.; Huang, Y.H.; Deng, A.H.; Gao, C.; Hou, Y.; Yuan, J.M. Plasma environmental effect on Auger electron spectroscopy of an ion embedded in a dense plasma. Phys. Rev. A 2025, 112, 023115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fushitani, M.; Sasaki, Y.; Matsuda, A.; Fujise, H.; Kawabe, Y.; Hashigaya, K.; Owada, S.; Togashi, T.; Nakajima, K.; Yabashi, M.; et al. Multielectron-Ion Coincidence Spectroscopy of Xe in Extreme Ultraviolet Laser Fields: Nonlinear Multiple Ionization via Double Core-Hole States. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2020, 124, 193201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukuzawa, H.; Son, S.-K.; Motomura, K.; Mondal, S.; Nagaya, K.; Wada, S.; Liu, X.-J.; Feifel, R.; Tachibana, T.; Ito, Y.; et al. Deep Inner-Shell Multiphoton Ionization by Intense X-Ray Free-Electron Laser Pulses. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2013, 110, 173005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hikosaka, Y.; Lablanquie, P.; Penent, F.; Kaneyasu, T.; Shigemasa, E.; Eland, J.H.D.; Aoto, T.; Ito, K. Double Photoionization into Double Core-Hole States in Xe. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2007, 98, 183002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjorneholm, O.; Sundin, S.; Svensson, S.; Marinho, R.R.T.; de Brito, A.N.; Gelmukhanov, F.; Agren, H. Femtosecond dissociation of the core-excited HCl monitored by frequency detuning. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1997, 79, 3150–3153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, N.H.; Schreifels, J.A. Surface Analysis: X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy and Auger Electron Spectroscopy. Anal. Chem. 2000, 72, 99R–110R. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gessner, O.; Guhr, M. Monitoring ultrafast chemical dynamics by time-domain X-ray photo- and Auger-electron spectroscopy. Acc. Chem. Res. 2016, 49, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piancastelli, M.N.; Goldsztejn, G.; Marchenko, T.; Guillemin, R.; Kushawaha, R.K.; Journel, L.; Carniato, S.; Rueff, J.-P.; Ceolin, D.; Simon, M. Core-hole-clock spectroscopies in the tender X-ray domain. J. Phys. B 2014, 47, 124031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miteva, T.; Kryzhevoi, N.V.; Sisourat, N.; Nicolas, C.; Pokapanich, W.; Saisopa, T.; Songsiriritthigul, P.; Rattanachai, Y.; Dreuw, A.; Wenzel, J.; et al. The all-seeing eyes of resonant Auger electron spectroscopy: A study on Aqueous solution using tender X-rays. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2018, 9, 4457–4462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinko, S.M.; Ciricosta, O.; Preston, T.R.; Rackstraw, D.S.; Brown, C.R.D.; Burian, T.; Chalupsky, J.; Cho, B.I.; Chung, H.-K.; Engelhorn, K.; et al. Investigation of femtosecond collisional ionization rates in a solid-density aluminium plasma. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Berg, Q.Y.; Fernandez-Tello, E.V.; Burian, T.; Chalupsky, J.; Chung, H.-K.; Ciricosta, O.; Dakovski, G.L.; Hajkova, V.; Hollebon, P.; Juha, L.; et al. Clocking femtosecond collisional dynamics via resonant X-ray spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018, 120, 055002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, M.F. The Flexible Atomic Code. Can. J. Phys. 2008, 86, 675–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pindzola, M.S.; Griffin, D.C. Double Auger processes in the electron-impact ionization of lithiumlike ions. Phys. Rev. A 1987, 36, 2628–2635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).