Abstract

We present a time-dependent nonperturbative theory of the reconstruction of attosecond beating by interference of multiphoton transitions (RABBIT) for photoelectron emission from hydrogen atoms in the transverse direction relative to the laser polarization axis. Extending our recent semiclassical strong-field approximation (SFA) model developed for parallel emission, we deduce analytical expressions for the transition amplitudes and demonstrate that the photoelectron probability distribution can be factorized into interhalf- and intrahalfcycle interference contributions, the latter modulating the intercycle pattern responsible for sideband formation. We identify the intrahalfcycle interference arising from trajectories released within the same half cycle as the mechanism governing attosecond phase delays in the perpendicular geometry. Our results reveal the suppression of even-order sidebands due to destructive interhalfcycle interference, leading to a characteristic spacing between adjacent peaks that doubles the standard spacing observed along the polarization axis. Comparisons with numerical calculations of the SFA and the ab initio solution of the time-dependent Schrödinger equation confirm the accuracy of the semiclassical description. This work provides a unified framework for understanding quantum interferences in attosecond chronoscopy, bridging the cases of parallel and perpendicular electron emission in RABBIT-like protocols.

1. Introduction

Attosecond science has opened the way to probe and control electronic dynamics in matter on their natural timescales. Pump–probe techniques combining attosecond extreme-ultraviolet (XUV) pulses with near-infrared (NIR) or visible laser fields provide access to phase and timing information encoded in photoelectron wave packets. Among them, attosecond streaking [1,2,3] and the reconstruction of attosecond beating by interference of two-photon transitions (RABBIT) [4,5] have become the keystone of attosecond chronoscopy of photoionization processes in atoms [4,6,7,8,9,10], molecules [11,12,13,14,15,16,17], and solids [3,18,19,20,21]. While streaking can be interpreted classically as an energy shift induced by the probe field [22,23,24,25,26,27], RABBIT is understood as a quantum interferometer arising from multiple indistinguishable paths towards one final continuum state [8,22].

Most theoretical descriptions of RABBIT fall back on perturbative treatments of the probe field, which assume that only two-photon processes dominate and that the probe field intensity is weak enough not to alter the ionization dynamics [28,29,30]. Nevertheless, the continuum–continuum transitions triggered by the probe are fundamental to the measurement process and cannot be ignored. Approaches relying on the strong-field approximation (SFA) [24,31,32,33,34,35,36,37] offer a robust nonperturbative framework that enables the study of RABBIT outside the perturbative regime, allowing the inclusion of multiple probe photons and allowing the identification of different interfering electron trajectories responsible for the observed phase delays. In our recent work [29], we developed a semiclassical time-dependent nonperturbative model within the SFA to describe electron emission in a RABBIT-like scheme along the polarization direction. We demonstrated that the photoelectron probability can be factored into intracycle and intercycle contributions, and we identified intracycle interference as the main mechanism governing the phase delays.

Anisotropy of photoemission delays was first discovered by Keller’s group [38], and subsequent angle-resolved studies of laser-assisted photoionization emission (LAPE) have revealed rich interference structures beyond the polarization axis [39]. Fano’s propensity rule was identified to explain the phase change of RABBIT in perpendicular emission as occurring due to different angular shapes following absorption or emission of IR photons [40,41]. In particular, photoelectron emission in the perpendicular direction exhibits a distinct interference pattern [42]. This leads to a natural factorization of the spectrum into intrahalfcycle and interhalfcycle contributions, which modulate the well-known intercycle interference responsible for sideband formation. Unlike the case of parallel emission [30], perpendicular emission shows destructive interference between half cycles for the absorption and emission of even numbers of NIR photons, resulting in the suppression of certain sidebands and the double of the characteristic energy spacing between neighboring peaks [42,43,44,45]. These features highlight the crucial role of symmetry and emission geometry to determine the structure of the photoelectron spectrum (PES).

In this work, we generalize the nonperturbative, time-dependent SFA-based RABBIT framework introduced in [29] to describe photoelectron emission in the direction orthogonal to the laser polarization axis. We demonstrate that our approach provides a unified semiclassical framework for understanding perpendicular emission in RABBIT-like protocols. We obtain an analytical factorization of the photoelectron momentum distribution into intrahalfcycle and interhalfcycle interference contributions. We also demonstrate that the intrahalfcycle interference is directly responsible for the attosecond phase delays. This work thus bridges previous studies on parallel [29] and perpendicular [42] emission, offering new insights into the role of quantum interferences in attosecond chronoscopy.

The structure of the paper is as follows. Section 2 outlines the semiclassical model (SCM) employed to compute photoelectron spectra for emission perpendicular to the laser polarization within the RABBIT scheme. Section 3 presents and analyzes the results, comparing the SCM predictions with those obtained from the SFA and from ab initio calculations based on the time-dependent Schrödinger equation (TDSE) [46,47,48]. Section 4 contains the concluding remarks. Unless noted otherwise, all quantities in this work are expressed in atomic units.

2. Theory and Methods

We study the ionization of an atom interacting with an external laser field in the single-active-electron (SAE) approximation. The TDSE reads

where denotes the field-free atomic Hamiltonian, with the first term representing the electron’s kinetic energy and the second describing its Coulomb interaction with the ionic core. The laser–atom coupling, referred as the interaction Hamiltonian , on the right-hand side of Equation (1) produces the promotion of the initially bound electron in the atomic state to the continuum final state with energy and final momentum . The photoelectron momentum spectrum can then be evaluated as

where denotes the transition amplitude .

In time-dependent distorted-wave theory, the prior-form transition amplitude is given by [33,49]

Here, corresponds to the initial atomic state characterized by the ionization potential , while is the final-state wave function. Within the SFA framework, the Coulomb influence of the residual ion on the emitted electron is ignored, so the final state reduces to the Volkov solution [50], , describing a free electron interacting solely with the electromagnetic field. For simplicity, in this work, we consider photoionization of a hydrogen atom due to a short XUV pulse train produced by a pair of consecutive odd high-order harmonics and supported by a near-infrared (NIR) driving field at the fundamental frequency . The approach developed here can be straightforwardly extended to other atomic systems within the SAE framework. In our setup, both the HH fields and the NIR laser are linearly polarized along the same axis, , where

where , , and are functions between 0 and 1 that mimic the corresponding pulse envelopes, and and are the field strengths of the NIR and HH lasers, respectively. Each harmonic takes on a phase and , while the NIR takes a phase . In the case of a long pulse that is smoothly switched on and off, the vector potential takes the following form in its central portion:

where we have supposed that the harmonic intensity of this component is much smaller than that of the fundamental field, satisfying for large harmonic orders, i.e., . Therefore, the vector potential of the two HHs can be neglected.

Our study is limited to photoelectron momenta in the direction orthogonal to the field’s polarization axis ( in cylindrical coordinates). We analyze similarities and differences with those obtained for emission along the polarization axis (), a configuration recently investigated in [29]. As we use the length gauge in the present work, i.e., , then from Equation (4), the expression for in Equation (3) is decomposable into parts corresponding to the different driving fields, i.e., , with

where

and

where the dipole matrix element is given by , and denotes the generalized classical action associated with the harmonic frequency , i.e., HH. The vector potential [Equation (5)] is only used in the action in the exponent, while the full field [Equation (4)] including all terms is used in the electric field in the exponential prefactor. With a suitable selection of NIR and XUV parameters, the energy region associated with the LAPE processes driven by HH and HH remains well separated from the energy range corresponding to ionization by the NIR field alone. Therefore, we can neglect the contribution of NIR ionization with respect to the contribution of the XUV pulse train. We justify this assumption in the next section. Equation (6) employs the rotating-wave approximation [29,30,39,42], treating the high-frequency ionization amplitude associated with HH as a single-photon absorption event with energy . In the flat-top interval of the vector potential in Equation (5)—that is, when —the temporal integral in Equation (8) can be solved analytically, i.e.,

where and define the electron ponderomotive energy under the fundamental-frequency NIR electric field.

The RABBIT methodology can be interpreted as a specific realization of LAPE in which a sequence of high-harmonic components initiates ionization. To streamline the discussion, we focus on the situation where only two contiguous odd harmonics—HH and HH—with frequencies and interact with the atom. After ionization, the electron may undergo continuum–continuum transitions driven by the fundamental field of frequency . In this framework, the transition probability from the initial bound state to the continuum is described as the coherent sum of the contributions associated with each harmonic, i.e.,

where is defined as in Equation (6). The case of a single contributing HH has already been studied, showing that the phase is not important, affecting the photoelectron spectrum only through boundary conditions of the short XUV pulse [30,39,42]. Instead, in the RABBIT protocol, the phases associated with the two transition amplitudes, and , in Equation (10) become relevant. In the RABBIT scheme, the introduction of multiple high-frequency components in the pump field—two in the present case—removes the time-translation invariance that exists when ionization is driven by a single harmonic. As a result, one can define a reference time for the phase of the probe field [29]. Consequently, the ionization probability [Equation (10)] is sensitive to the relative phases , , and in Equation (4).

Assuming that the constant portion of the NIR envelope field begins at , the square of the vector potential in Equation (5) is periodic every half cycle, i.e., , or equivalently, with j being any positive integer number, as well as the square of the dipole moment, i.e., or equivalently, (see Appendix A). We also find that the second term on the right-hand side of Equation (9) exhibits temporal oscillations with a period , which is half the period of the driving field, namely,

The integration domain of Equation (6) extends to the non-zero values of the envelope for simplicity , with N any real positive number. However, we specify our analysis for half-integer values of Thus, we can rewrite the matrix element due to the contribution of HH() in Equation (6) as the addition of N optical laser cycles of the probe field, namely

By applying the change of variables , the time integral in the second line of Equation (12) is shifted by j cycles of the probe field. Taking into account the periodic behavior of , which follows from the periodicity of the dipole term when , the transition amplitude can then be factorized as [51,52]

where the factor

in Equation (13) accounts for the contribution of HH ionization produced during a single cycle of the fundamental field.

When the XUV pulse comprises an integer number of optical cycles N of the fundamental field, the factors and do not depend on the harmonic index m. Therefore, they can be factorized in Equation (10), leading to

We manage to split the total transition probability in the RABBIT protocol into the intercycle interference factor [first factor in Equation (15)] and the intracyle interference factor [second factor in Equation (15)] [29,33,52,53]. The condition for the denominator of the intercycle factor to vanish, , yields the energy values

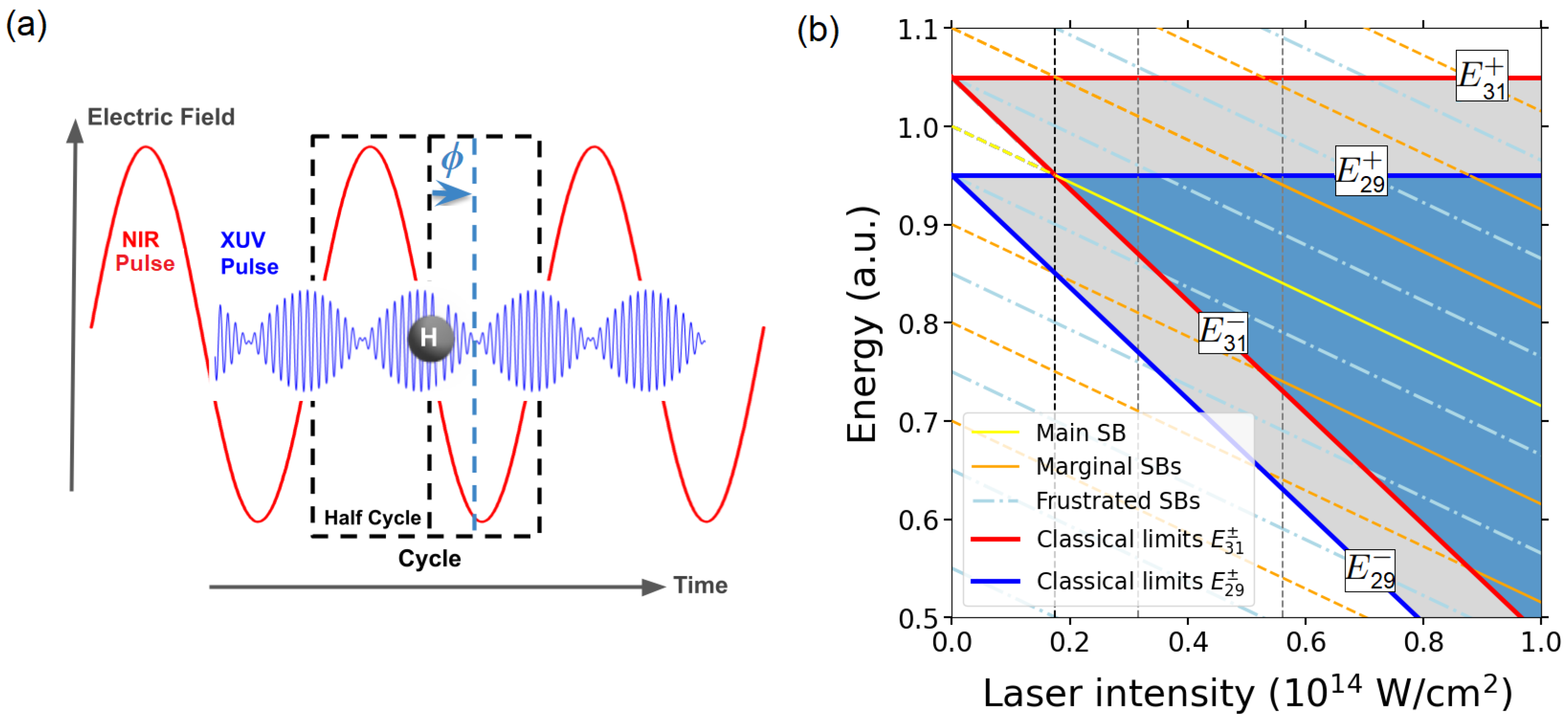

associated with absorption of a single photon from HH, with a frequency of , together with the additional absorption or emission of (|n|) fundamental photons at frequency for or , respectively. The resulting maxima at the energies given by Equation (16) correspond to the SBs in the PES of the HH in the presence of the fundamental laser [29,30,39,42], and they are also the SBs formed by the laser-dressed train of pulses composed by HH and HH. In fact, when the number of cycles of the NIR , the intercycle factor satisfies the energy conservation. When the pump pulse has a finite duration (approximately ), the sidebands are no longer infinitely sharp but instead exhibit a width ∼. This satisfies the uncertainty condition , with representing the pulse duration. In Figure 1, we have depicted the corresponding SBs as a function of the intensity of the NIR laser, which results in straight lines of negative slope . One can observe that their energies are straight lines, since the ponderomotive energy increases proportionally with the NIR laser intensity. In Figure 1 we can observe the SBs’ values given by Equation (16) for a combination of values of m and n.

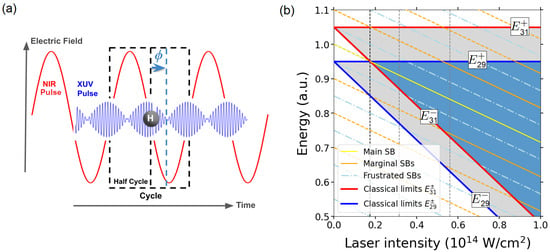

Figure 1.

(a) Schematic diagram of the RABBIT protocol considered, in which an ultrashort laser pulse is incident on a hydrogen atom. The incident laser pulse consists of a component in the NIR range ( a.u. ) and two odd harmonics in the XUV range (HH29 and HH31 with frequency a.u. and a.u. , respectively). (b) Schematic spectra in the energy domain for ionization of HH29 and HH31 as functions of the NIR laser intensity. The classically allowed region for each harmonic, ( and 15), is shaded in light gray, whereas the overlap of the two classically allowed regions, (), is shaded in blue. The upper classical limits are independent of the NIR laser intensity and the lower classical limits exhibit a slope of . The white area represents classically forbidden regions. HH29, HH31, and all SBs are drawn as straight lines of slope given by . Full lines correspond to observed (odd) SBs, whereas dotted–dashed lines show forbidden (even) SBs. The left vertical dashed line indicates the minimum NIR intensity in the classical allowed region for the two harmonics HH29 and HH31: W/cm2 ( a.u.). The other two vertical dashed lines indicate the two NIR intensity values analyzed in the text: W/cm2 ( a.u.) and W/cm2 ( a.u.). The frequency of the NIR laser is a.u., whereas the HH29 and HH31 frequencies are a.u. and a.u., respectively. a.u. (atomic hydrogen).

Alternatively, we can regard the intracycle factor in Equation (14) as the separate contribution of the two half cycles

where in the second term of Equation (17) the substitution has been performed, and the periodicity properties of and have been used to arrive at Equation (18). The factor in Equation (18) corresponds to the interference between the ionization during the first and second half cycles of only one optical cycle of the NIR laser and its square, known as the interhalfcycle interference pattern, which cancels at with As a consequence, LAPE channels corresponding to the absorption or emission of an even number of NIR photons are suppressed or, equivalently, must be odd in Equation (16). Therefore, SBs with even numbers of exchanged photons in Figure 1, shown in dotted–dashed light blue (gray), become frustrated due to the interhalfcycle interference. This result is not surprising because the model assumes an initial 1 s state. In a partial wave development of the transition amplitude, the corresponding odd spherical harmonics (reached by an even number of NIR photons and one XUV photon) have zero values for perpendicular direction, i.e., , while the even spherical harmonics (reached by an odd number of NIR photon and one XUV photon) are non-zero in the perpendicular direction [42,43,44,45]. Conversely, our SCM shows no need for any partial wave development. The last factor in Equation (18) corresponds to the ionization amplitude due to HH occurring during only one half-cycle pulse of the NIR, defined as

Taking into account Equations (17) and (19), the transition probability of LAPE corresponding to HH becomes

It is easy to show that when the duration of both laser fields of HH and HH are an integer number of half cycles of the NIR laser, i.e., with , the factor is independent of the HH index which means that it can be factorized in Equation (10) as

Equation (22) indicates that the photoelectron yield factorizes into an interhalfcycle factor—capturing interference between emissions from different half cycles—and an intrahalfcycle factor that describes interference processes occurring within a single half cycle. So far, it is worth mentioning that factorizations into interhalf- and intrahalfcycle [Equation (22)] or inter- and intracycle interferences [Equation (15)] are direct consequences of the time symmetries of the problem and rely only on the SFA.

We can compute either numerically, whose result we call SFA, or analytically, by using the saddle-point approximation, which is the cornerstone of SCM; namely

whose saddle times and weighting factor are found in Appendix B. In Figure 1 we plot the classical allowed regions for the LAPE ionization from HH29 and HH31, observing an overlap between them, which conforms to the classical allowed region in our non-perturbative SCM for RABBIT (see Appendix B). The minimum value of the classical allowed region for RABBIT corresponds to , which, for a.u., corresponds to W/cm2, which is shown in Figure 1 with the vertical left dotted line.

Using the accumulated action and the average action , the expression for becomes

where the factor is given by

Summing up, within the SCM, the RABBIT transition probability to the continuum can be written as

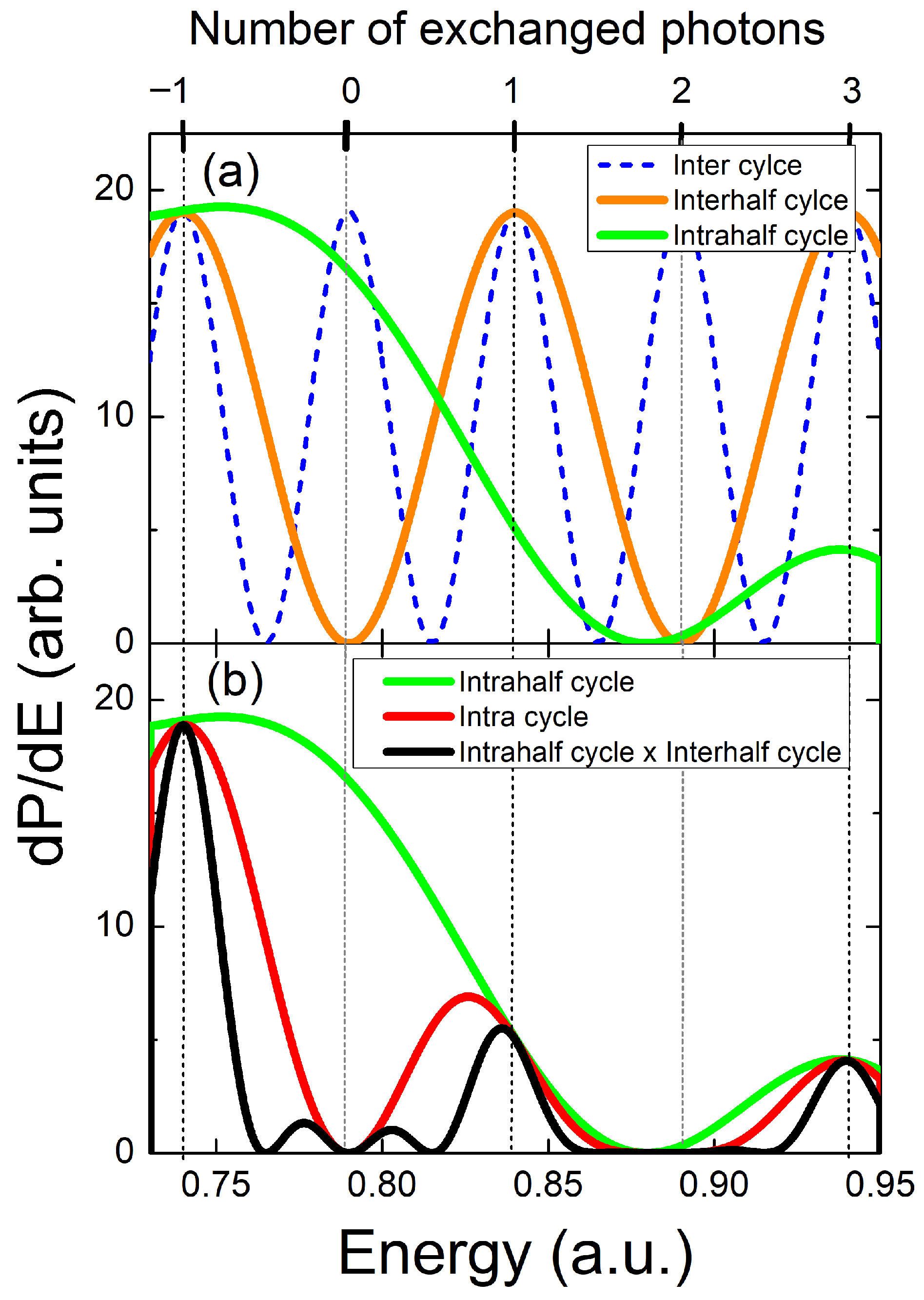

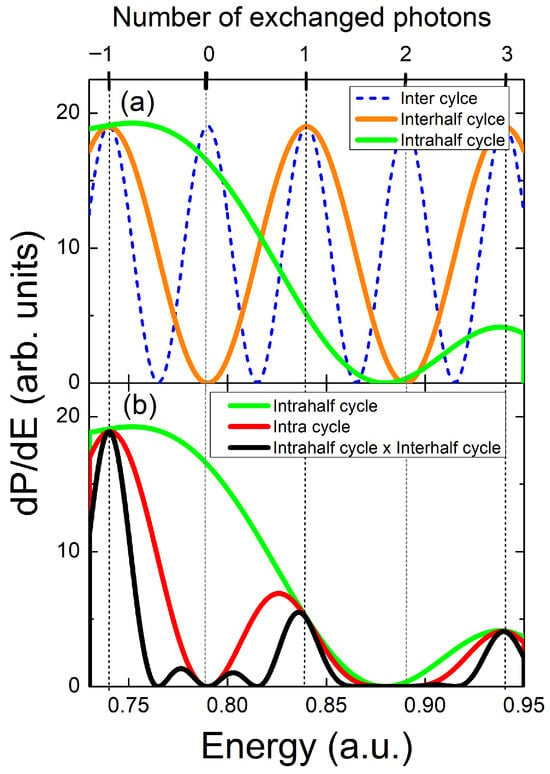

where the average action fulfills , with being a constant multiple of . When electrons are emitted perpendicularly, is not affected by changes in laser intensity, whereas in the parallel case it varies with field strength [29]. In Figure 2a we plot the interhalfcycle interference factor with the solid orange line. We observe that even values of exchanged NIR photons n are precluded, meaning that we can name even SBs as frustrated SBs. This characteristic applies not only to the RABBIT protocol, but also to LAPE and photoionization in the perpendicular direction [42,43,44,45]. In Figure 2b, through its modulation of the intracycle pattern, the intrahalfcycle interference factor ultimately governs the modulation of the total ionization probability. The small peaks at and correspond to the incipient SB with , which is suppressed by interhalfcycle interference. In Figure 2a we plot the intercycle factor as a function of the photoelectron energy for , showing the SB energy peaks of width and positions given by Equation (16). In Figure 2b, the intracycle interference pattern for and the total pattern for are shown using red and black lines. One can observe that the intracycle pattern for modulates the corresponding PES to This result was already observed for forward emission in the RABBIT protocol [29]. In the following, we point out the differences between forward and perpendicular emission.

Figure 2.

Interference patterns in the perpendicular direction within the SCM for . (a) Intrahalfcycle interference pattern, thick green line; intercycle pattern, thin dotted blue line; and interhalfcycle pattern, given as thin orange line [see Equations (15) and (26)]. (b) The thick green curve denotes the intrahalfcycle structure, whereas the black curve displays the full interference pattern [see Equations (15) and (26)]. The intracycle pattern is shown using a red line. Vertical lines depict the energy positions of the SBs with odd in Equation (16). The NIR laser intensity is W/cm2 ( a.u.), and the rest of the laser parameters match those previously introduced in Figure 1. The relative phase and , with .

We now examine the phase of the probability amplitude corresponding to each SB for energies sufficiently close to a sideband [Equation (16)]. In this limit, where , the total amplitude in Equation (26) can be expressed as

where we have defined , and corresponds to energies in Equation (16).

Here, A and B quantify the strengths of each interfering pathway, and is the total phase delay (see Appendix B of [29]):

The first contribution to stems from the relative group delays of the two neighboring harmonics driving ionization, whereas the second arises from atomic phase shifts encoded in the SFA dipole transition elements. Within our semiclassical RABBIT model, each sideband is produced by interference between two multi-path contributions, rather than by a single pair of two-photon channels as predicted by lowest-order perturbation theory [4,6,8,54,55].

3. Results and Discussion

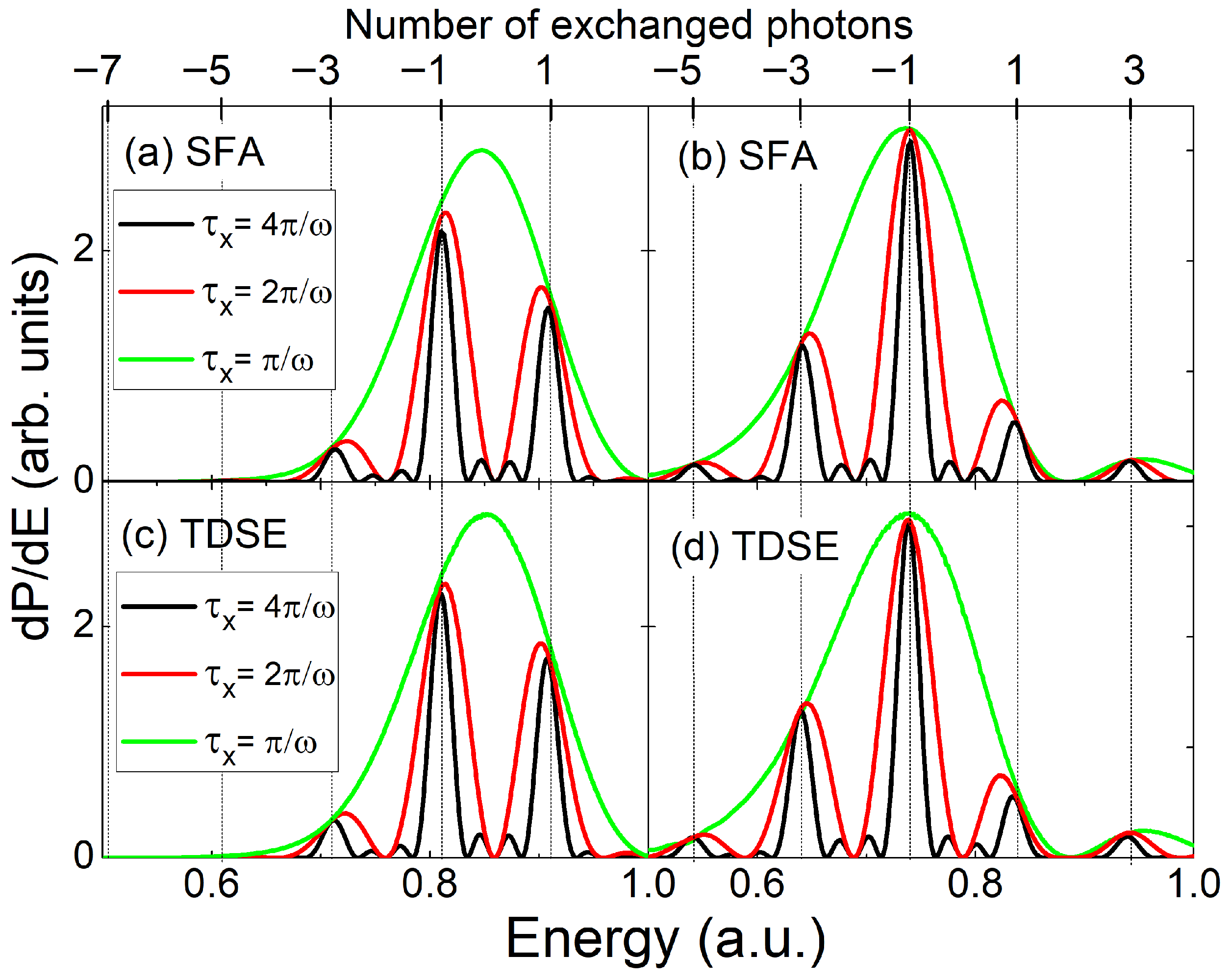

To test the general result that the ionization probability for photoelectrons emitted perpendicular to the polarization axis of the XUV pulse train and the NIR laser can be factorized in two distinct ways—either into intracycle and intercycle interferences [Equation (15)] or into intrahalf- and interhalfcycle interferences [Equation (26)]—we compare the photoelectron spectrum as obtained from the SCM, the SFA, and ab initio TDSE simulations. The NIR and XUV frequencies are taken as a.u. and , respectively, with and 15. We consider the NIR laser duration to be , corresponding to four optical cycles, and three different durations of the XUV pulse train, , , and , corresponding to , and 2 optical cycles of the NIR laser, all of them starting right after the second cycle of the NIR laser, saving the first cycle for a linear ramp on and the fourth cycle for a linear ramp off. The envelopes are defined in the same way: a unit-amplitude flat-top with one-cycle linear ramps on and off.

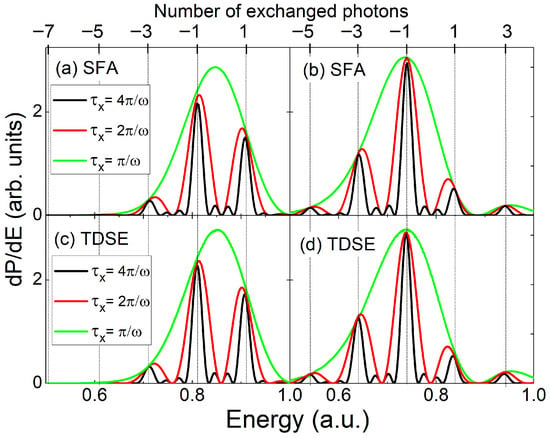

Figure 3 presents the SFA and TDSE results obtained using the same XUV and NIR pulse parameters as in Figure 2. We consider a.u. and two values of the NIR field amplitude: a.u. for panels (a) and (c), and a.u. () for panels (b) and (d). In all cases, the relative phases satisfy and . The agreement between the PES along the perpendicular direction calculated with SFA and TDSE is remarkable in RABBIT. This fact was already emphasized in Ref. [43] for the case of photoionization by a quasi-monochromatic NIR laser, where the two cases of perpendicular and parallel emission were compared and the reasons why the SFA works as well as it does for the parallel case were pointed out, and in Refs. [30,42] for the case of LAPE with only one XUV frequency. This complements their comparison with the SCM results in Figure 2b. Several conclusions can be drawn. First, The insignificant role played by the Coulomb potential of the remaining ion in shaping the electron yield is confirmed by the almost indistinguishable SFA and TDSE spectra. A more detailed analysis of Coulomb effects in RABBIT spectra will be presented in a forthcoming work. Second, the factorization of perpendicular photoelectron emission into either intra- and intercycle interference patterns [Equation (15)] or intra- and interhalfcycle interference patterns [Equation (26)] is validated not only in the SCM and SFA spectra but also in the full TDSE results. Figure 3 shows that the intrahalfcycle interference pattern—obtained from the energy distribution generated by an XUV pulse of duration (half a laser cycle)—modulates the intracycle interference pattern, which is obtained from the energy distribution corresponding to an XUV pulse with a duration of one full laser cycle, i.e., , as predicted in Equation (26). In the same way, the intracycle interference factor modulates the SBs in the energy distribution for a longer XUV pulse, i.e., . When the XUV pulse duration involves several periods of the laser, i.e., , the positions of the SBs in the SFA and TDSE calculations in Figure 4 agree with the SCM expressed in Equation (16) for an odd number of exchanged NIR photons, as described in the previous section. Conversely, SBs with an even number of exchanged NIR photons are suppressed by the destructive interference between XUV emission during the first and second half cycles of all the cycles of the NIR laser involved. The photoelectron spectra obtained from the SFA and TDSE calculations extend beyond the classical upper-limit energies predicted by the model, a.u. and a.u., and beyond the lower limits a.u. ( a.u.) and a.u. ( a.u.) for W/cm2 ( W/cm2) and a.u. ( a.u.).

Figure 3.

Photoelectron spectra for perpendicular emission: SFA results are shown in panels (a,b) and TDSE results in panels (c,d) for various XUV pulse durations, (green), (red), and (black), at two different NIR intensities: W/cm2 ( a.u. in (a,c)) and W/cm2 ( a.u. in (b,d)). The XUV peak fields are and the NIR parameters are the same as in Figure 2. Vertical lines depict the positions of the relevant SBs (odd according to Equation (16). The relative phase is and . Photoelectron energy distributions have been vertically rescaled for better visualization.

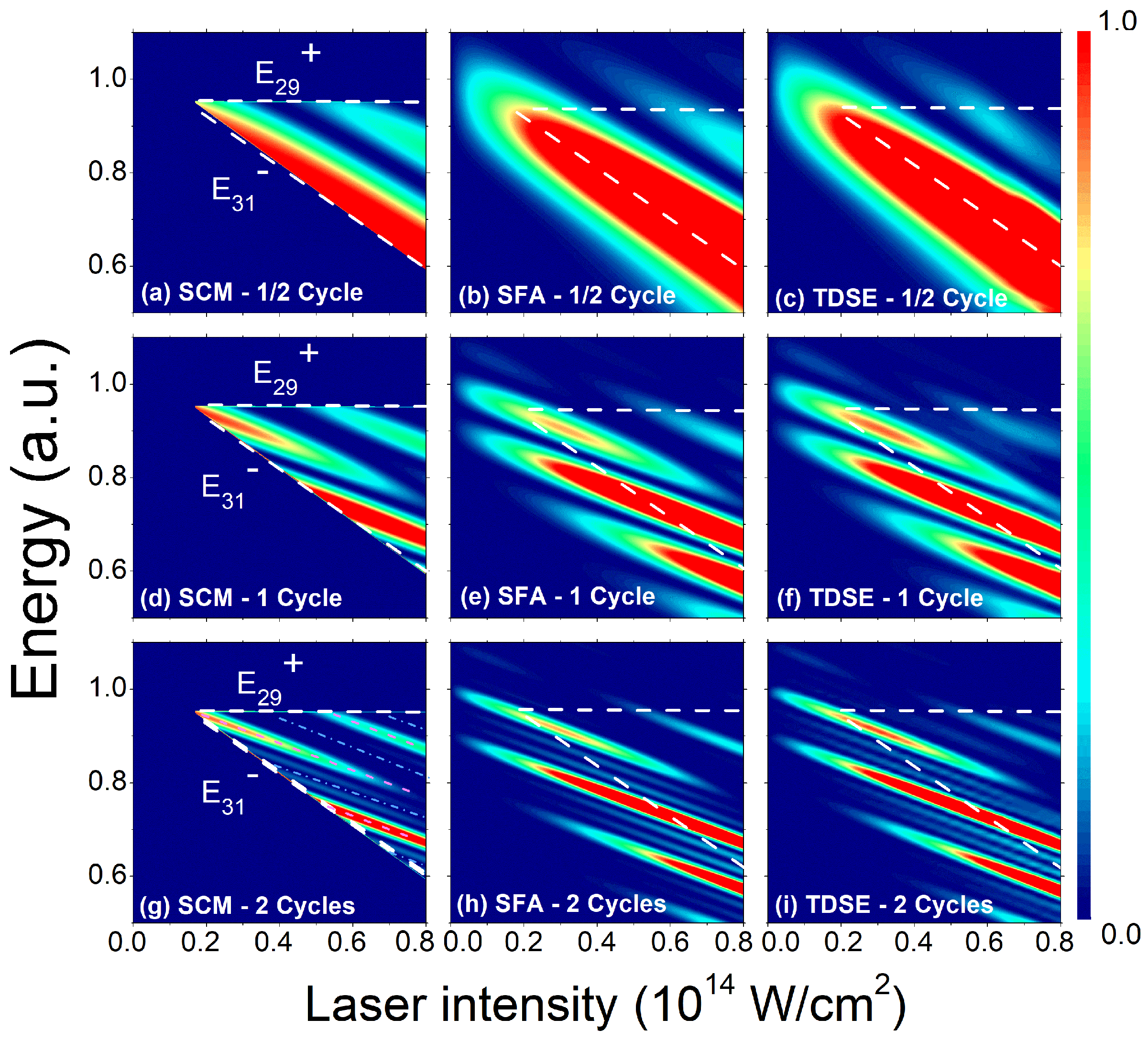

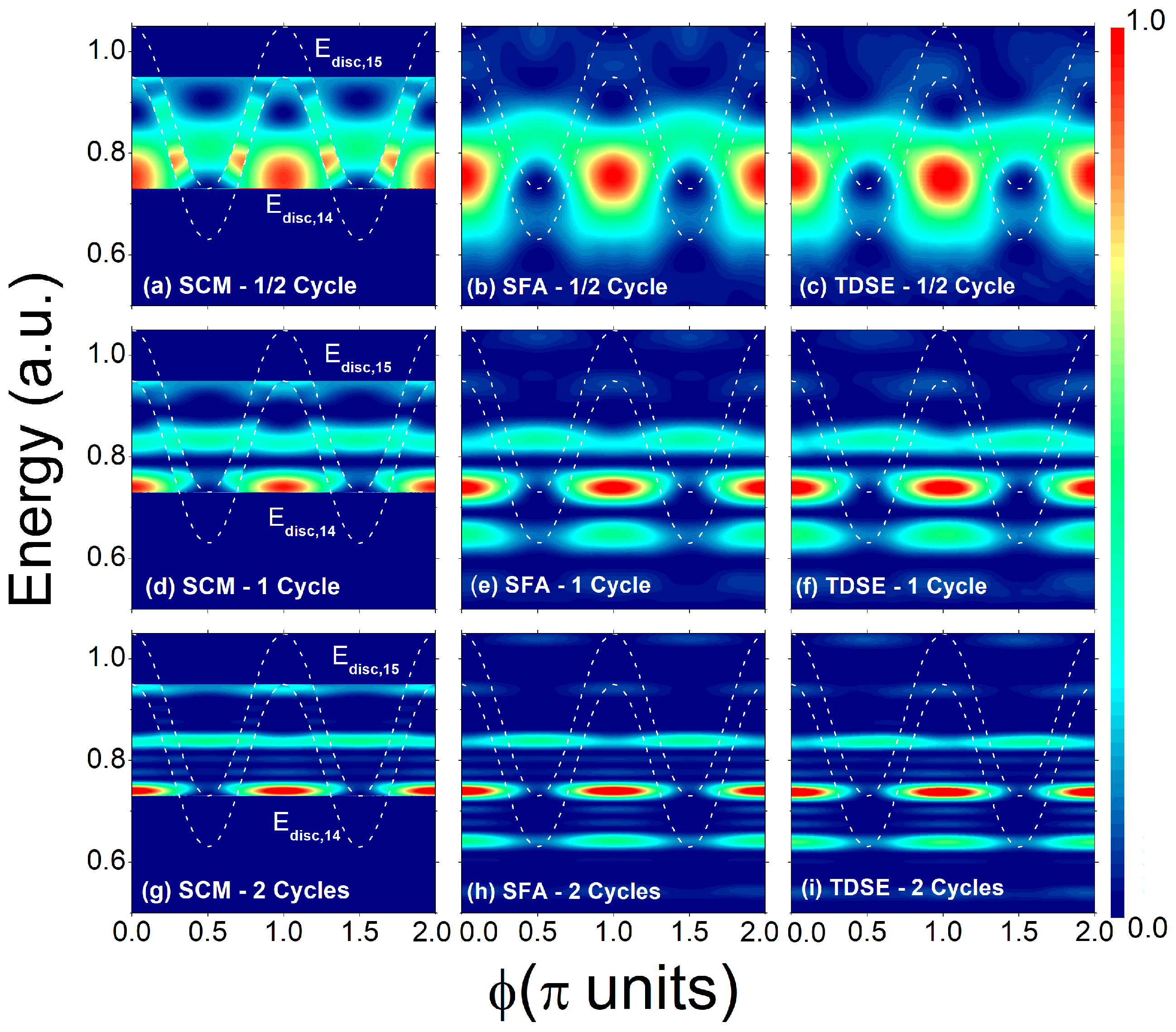

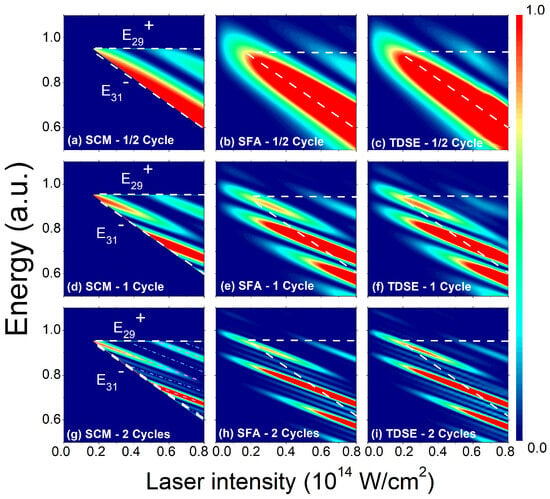

Figure 4.

Panels (a–i) present the perpendicular photoelectron spectra (arbitrary units) as functions of the NIR laser intensity, computed using the SCM [(a,d,g)], the SFA [(b,e,h)], and the TDSE [(c,f,i)]. The XUV pulse durations are , , and for the upper, middle, and lower rows, respectively. All remaining XUV and IR parameters are identical to those in the earlier figures. Classical boundaries are drawn as white dashed curves, and the frustrated sidebands are highlighted with light-blue dotted–dashed lines, i.e., with even , and the magenta dashed lines show the relevant SBs with odd n [Equation (16)].

We further examine how the perpendicular PES varies with NIR laser intensity, following the schematic diagram in Figure 1. Figure 4 presents the energy distributions obtained using the SCM (a, d, g), the SFA (b, e, h), and the TDSE (c, f, i) for NIR laser intensities up to W/cm2 ( a.u.). The analysis includes different XUV pulse durations, , , and . Figure 2 and Figure 3 correspond to cuts of Figure 4 at W/cm2 and W/cm2. By definition, the classical boundaries and , shown as dotted lines, delimit the SCM spectra in Figure 4a,d,g. For (first row), the intrahalfcycle interference stripes exhibit a negative slope. For (second row), the intrahalfcycle interference patterns are flanked by nodes which arise at the zeros of the interhalfcycle factor appearing in Equation (26). i.e., for , which vanishes for , i.e., for all even number of exchanged NIR photons. The slope of maxima (visible SBs) and minima (frustrated SBs) is where the intensity units are in W/cm2 and the difference in energy between consecutive maxima (as well as minima) is . This result is inherent to all emissions in the perpendicular direction to the polarization of the laser fields, not only for RABBIT and LAPE but also for one-color ionization [43,44,45]. For (third column), the sidebands become thinner due to the time–energy uncertainty relation , which reflects destructive intercycle interference for energies far from conservation values. The SCM successfully recovers the negative-slope intrahalf- and intracycle interference stripes observed in the SFA and TDSE spectra, but only within the classical energy bounds and (see Appendix B). The quantum SFA and TDSE spectra naturally spread beyond these limits because of quantum diffusion. We have checked the convergence of our TDSE code and found that it deteriorates abruptly for intensities greater than W/cm2. For W/cm2 (not shown), the loss of the continuum wave function relative to the ionization probability is as high as 14% due to absorption in the numerical box, whereas for W/cm2, it was 7%. For W/cm2, it was 2%, whereas for or W/cm2, it is as low as 0.24%.

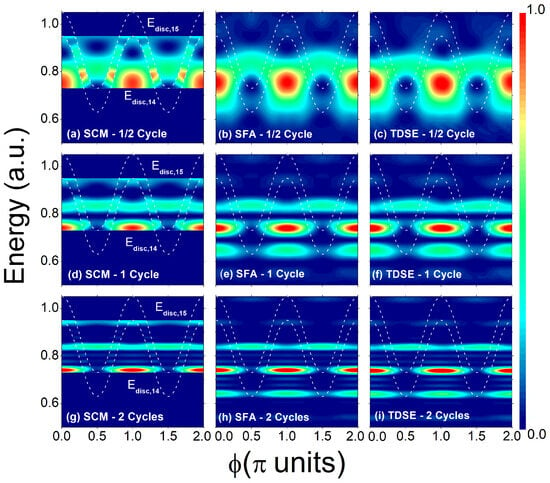

So far, we have considered transverse electron emission for a fixed phase . To examine how the intracycle interference structure evolves with the relative phase, we analyze the photoelectron spectra as is varied from 0 to . Figure 5a shows the intrahalfcycle interference pattern () calculated within the SCM (for ). We mark the two discontinuities for HH29 and HH31 at energy values (see Appendix B and [42]. For , the discontinuity lies at , which coincides with the upper classical boundary. As changes, the discontinuity tracks the squared vector potential with -periodicity, in contrast with the -periodicity characteristic of parallel emission [29,30,42]. For , the discontinuity occurs at , while for , it shifts to . The intracycle interference () and total spectra () shown in Figure 5d,e display jumps in the probability distribution at the discontinuities. For , the SCM spectrum (Figure 5d) shows horizontal lines corresponding to intracycle interference, i.e., interference between the first and second half cycles, consistent with the factor in Equation (18). For (Figure 5g), the SCM spectrum shows intercycle interference modulated by the intracycle pattern, but the discontinuities at the SBs [Equation (16)] are absent. As the SBs narrow, the discontinuities blur. The SFA and TDSE results further extend the classical limits, exhibiting more SBs, as seen in second and third columns of Figure 5, and agree closely with the SCM within the classical boundaries, validating the time-dependent semiclassical picture. All SCM spectrograms in Figure 5 show a good qualitative agreement with the quantum SFA and TDSE counterparts. However, SCM discrepancies arise, like classical boundaries, their concomitant caustics inherent to all semiclassical theories, and discontinuities (see Appendix B). These three types of discrepancies are evident in the first row of Figure 5 for a half cycle duration of the XUV pulse and exist irrespective of the weight used in the theory. However, as the XUV pulse duration increases, sidebands become thinner, which conveniently masks the mentioned SCM discrepancies, improving the similarities between the SCM and quantum results.

Figure 5.

Photoelectron spectra for electrons emitted perpendicular to the polarization axis (arbitrary units) displayed as functions of the NIR laser phase . Results obtained with the SCM are shown in panels (a,d,g); the corresponding SFA calculations appear in panels (b,e,h); and the TDSE results are presented in panels (c,f,i). The XUV pulse durations are (a–c), (d–f), and (g–i). The NIR laser intensity is W/cm2 ( a.u.). The rest of the XUV and IR parameters are the same as in preceding figures. The dashed lines show the corresponding energy discontinuities for and (see Appendix B).

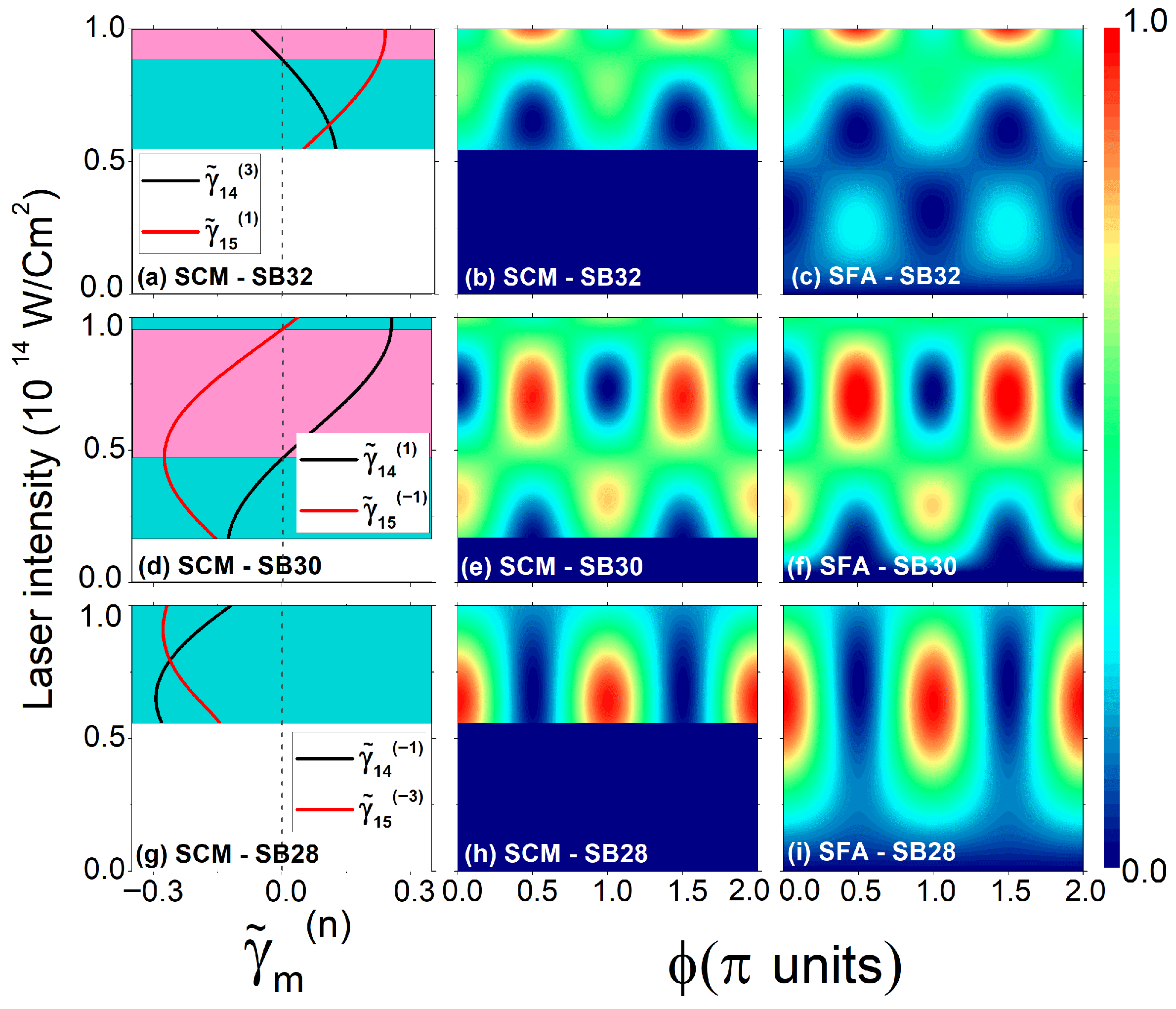

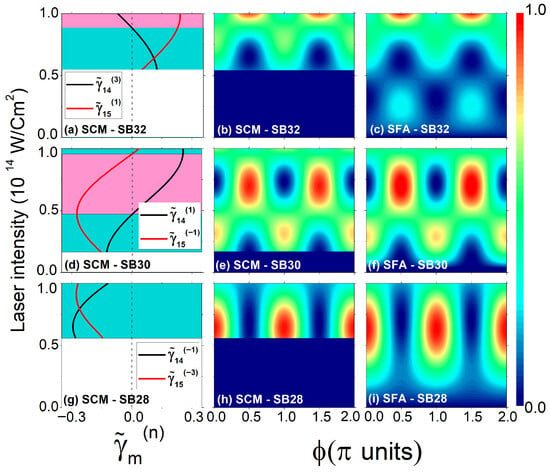

Finally, to scrutinize the phase delays of the sidebands as functions of the NIR intensity, Figure 6 shows the perpendicular photoelectron spectra of hydrogen for SB32, SB30, and SB28 within the SCM and SFA. The SCM reproduces all the main features of the SFA, except for SB32, which is out of the applicability region. At low NIR intensities, the distributions for SB30 and SB28 maximize at and , indicating that both sidebands are in phase, i.e., [see Equation (28)]. Conversely, SB32 peaks at and for low intensity, with an ensuing phase delay

Figure 6.

Photoelectron spectra for perpendicular emission as functions of the NIR laser intensity I and phase calculated within the SCM, in the middle column (b,e,h), and SFA, in the right column (c,f,i). Emission energies correspond to SB32 in (b,c), SB30 in (e,f), and SB28 in (h,i). The left column shows the normalized intrahalfcycle factor as a function of the probe laser intensity for energies corresponding to (a) SB32, (d) SB30, and (g) SB28. For each panel we show the intrahalfcycle factors for paths (a) and , (d) and , and (g) and . Cyan (magenta) regions correspond to intensity values for which the different intracycle factors have the same (opposite) sign. Here we use the same set of pulse parameters and the same SFA envelope as presented in the previous figures.

The maxima of SB28 remain invariant with probe intensity (at least up to the studied intensity of W/cm2), while SB32 and SB30 exhibit behavior transitions. SB32 peaks at for low intensities ( W/cm2), giving ; at for W/cm2 W/cm2, with ; and again at for higher intensities ( W/cm2), leading to . We observe that the phase delays are always or depending on the relative sign of the two contributing terms and , as expected from Equations (28) and (29) under the strong-field approximation. From Equations (28) and (29) we have demonstrated that sidebands have a 0 or phase within the SFA, which has also been shown by L. B. Madsen [56], and in above-threshold ionization [57], where the properties of the generalized Bessel functions can change sign as the intensity of the NIR laser field is increased. In addition, this reflects the common “rule of thumb” for phase delays predicted within the perturbative RABBIT framework [40,55,58]. The redistribution of population in the continuum to multiple sidebands has been addressed, for example, in the three-SB setup by Bharti et al. in Refs. [59,60]. The SCM could be extended to the non-classical region by using theories that are more sophisticated, for example, the uniform saddle-point approximation [61]; however, this is out of the scope of the present work.

4. Conclusions

We have developed a time-dependent nonperturbative theory of the RABBIT protocol for photoelectron emission perpendicular to the laser polarization axis. Building on our previous work for parallel emission, we generalized the semiclassical strong-field approximation by deriving analytical expressions that allow for a transparent interpretation of the phase-delay information. Our analysis shows that the perpendicular emission spectra can be factored into intrahalf- and interhalfcycle contributions or, alternatively, as intra- and intercycle contributions. In particular, we identified intrahalfcycle interference between trajectories released within the same half cycle as the main mechanism responsible for attosecond phase delays in this geometry. A distinctive feature of the perpendicular direction is the suppression of even-order sidebands, leading to a sideband spacing of , in sharp contrast to the spacing observed along the polarization axis. Comparisons with full SFA and the ab initio TDSE simulations confirm the validity of our nonperturbative semiclassical approach. The present theory thus provides a unified framework for describing attosecond chronoscopy in both parallel and perpendicular emission geometries within the strong-field approximation, where the influence of the Coulomb interaction can be neglected. Future work may extend this analysis to angle-resolved photoemission, to polarization-resolved pump–probe schemes, and to the inclusion of Coulomb effects, paving the way toward a more complete understanding of attosecond electron dynamics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.G.A. and S.D.L.; methodology, M.L.O., S.D.L. and D.G.A.; software, M.L.O., M.B., S.D.L. and D.G.A.; validation, M.L.O., S.D.L. and D.G.A.; formal analysis, M.L.O. and D.G.A.; investigation, M.L.O., S.D.L. and D.G.A.; resources, S.D.L. and D.G.A.; data curation, M.L.O., M.B. and S.D.L.; writing—original draft preparation, D.G.A.; writing—review and editing, M.L.O., S.D.L. and D.G.A.; visualization, M.L.O.; supervision, S.D.L. and D.G.A.; project administration, S.D.L. and D.G.A.; funding acquisition, S.D.L. and D.G.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Agencia I+D+i (Argentina), grant numbers PICT 2020-01755 and 2020-01434; Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET) (Argentina), grant number PIP 2022–2024 11220210100468CO; Programa Nacional RAICES Federal: Edición 2022 of Ministerio de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación (MinCyT); PICT 2023 RAÍCES FEDERAL 01-PICT-2023-02-10 from Agencia I+D+i (Argentina); and PIP Raices 2023–2025 (grant number: 29320230100003CO) of CONICET (Argentina).

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained in this article and can be solicited from the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support from 2020-01434 and PICT 2020-01755 of Agencia I+D+i (Argentina), PIP 2022-2024 11220210100468CO of CONICET (Argentina), and PIP Raices 2023-2025 29320230100003CO of CONICET (Argentina).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| RABBIT | Reconstruction of attosecond beating by interference of two-photon transitions |

| SCM | Semiclassical model |

| SFA | Strong-field approximation |

| TDSE | Time-dependent Schrödinger equation |

| PES | Photoelectron spectrum |

| HHn | High n-th order harmonic |

| LAPE | Laser-assisted photoionization emission |

| NIR | Near-infrared |

| XUV | Extreme ultraviolet |

| SB | Sideband |

Appendix A. Dipole Moment

For the 1 s state of a hydrogen atom, the dipole element can be expressed as

In the study of emission along the polarization axis in Ref. [29], the symmetry of the dipole matrix element was not considered. Contrarily, for perpendicular emission, it needs to be considered since, according to Equation (A1), the dipole elements along the polarization direction of consecutive half cycles fulfill

Thus, the odd and even half cycles contribute with opposite signs.

Appendix B. Saddle-Point Approximation

We can approximately solve the time integrals of Equation (19) using the saddle-point approximation, yielding the addition of two (semi)classical trajectories that have been born within the same half optical cycle shown in Equation (23). The saddle times fulfill the saddle equation , or equivalently,

with , resulting in

and the weighting factor is

where . From Equation (A3), the domain of the allowed classical trajectories perpendicular to the polarization axis is since, as , then the upper and the lower classical boundaries naturally arise, where and , whether . The classical allowed region for RABBIT is simply the intersection of the allowed regions for the HH and HH. The modulo function in the definition of ionization times introduces a discontinuity, which is an artifact of the SCM [42].

References

- Kienberger, R.; Goulielmakis, E.; Uiberacker, M.; Baltuska, A.; Yakovlev, V.; Bammer, F.; Scrinzi, A.; Westerwalbesloh, T.; Kleineberg, U.; Heinzmann, U.; et al. Atomic transient recorder. Nature 2004, 427, 817–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Becker, A.; Thumm, U. Strong-Field Modulated Diffraction Effects in the Correlated Electron-Nuclear Motion in Dissociating H2+. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 101, 213002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalieri, A.L.; Fritz, D.M.; Lee, S.H.; Bucksbaum, P.H.; Reis, D.A.; Rudati, J.; Mills, D.M.; Fuoss, P.H.; Stephenson, G.B.; Kao, C.C.; et al. Clocking Femtosecond X Rays. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005, 94, 114801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, P.M.; Toma, E.S.; Breger, P.; Mullot, G.; Augé, F.; Balcou, P.; Muller, H.G.; Agostini, P. Observation of a Train of Attosecond Pulses from High Harmonic Generation. Science 2001, 292, 1689–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauritsson, J.; Johnsson, P.; Mansten, E.; Swoboda, M.; Ruchon, T.; L’Huillier, A.; Schafer, K.J. Coherent Electron Scattering Captured by an Attosecond Quantum Stroboscope. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 100, 073003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Véniard, V.; Taïeb, R.; Maquet, A. Phase dependence of (N+1)-color (N > 1) ir-uv photoionization of atoms with higher harmonics. Phys. Rev. A 1996, 54, 721–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultze, M.; Fieß, M.; Karpowicz, N.; Gagnon, J.; Korbman, M.; Hofstetter, M.; Neppl, S.; Cavalieri, A.L.; Komninos, Y.; Mercouris, T.; et al. Delay in Photoemission. Science 2010, 328, 1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klünder, K.; Dahlström, J.M.; Gisselbrecht, M.; Fordell, T.; Swoboda, M.; Guénot, D.; Johnsson, P.; Caillat, J.; Mauritsson, J.; Maquet, A.; et al. Probing Single-Photon Ionization on the Attosecond Time Scale. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 106, 169904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isinger, M.; Squibb, R.J.; Busto, D.; Zhong, S.; Harth, A.; Kroon, D.; Nandi, S.; Arnold, C.L.; Miranda, M.; Dahlström, J.M.; et al. Photoionization in the time and frequency domain. Science 2017, 358, 893–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, J.; Cattaneo, L.; Patchkovskii, S.; Zimmermann, T.; Cirelli, C.; Lucchini, M.; Kheifets, A.; Landsman, A.S.; Keller, U. Orientation-dependent stereo Wigner time delay and electron localization in a small molecule. Science 2018, 360, 1326–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haessler, S.; Fabre, B.; Higuet, J.; Caillat, J.; Ruchon, T.; Breger, P.; Carré, B.; Constant, E.; Maquet, A.; Mével, E.; et al. Phase-resolved attosecond near-threshold photoionization of molecular nitrogen. Phys. Rev. A At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 2009, 80, 011404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudawski, P.; Harth, A.; Guo, C.; Lorek, E.; Miranda, M.; Heyl, C.M.; Larsen, E.W.; Ahrens, J.; Prochnow, O.; Binhammer, T.; et al. Carrier-envelope phase dependent high-order harmonic generation with a high-repetition rate OPCPA-system. Eur. Phys. J. D 2015, 69, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotur, M.; Guenot, D.; Jiménez-Galán, A.; Kroon, D.; Larsen, E.W.; Louisy, M.; Bengtsson, S.; Miranda, M.; Mauritsson, J.; Arnold, C.; et al. Spectral phase measurement of a Fano resonance using tunable attosecond pulses. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruson, V.; Barreau, L.; Jiménez-Galan, Á.; Risoud, F.; Caillat, J.; Maquet, A.; Carré, B.; Lepetit, F.; Hergott, J.F.; Ruchon, T.; et al. Attosecond dynamics through a Fano resonance: Monitoring the birth of a photoelectron. Science 2016, 354, 734–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huppert, M.; Jordan, I.; Baykusheva, D.; Von Conta, A.; Wörner, H.J. Attosecond Delays in Molecular Photoionization. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016, 117, 093001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaulieu, S.; Comby, A.; Clergerie, A.; Caillat, J.; Descamps, D.; Dudovich, N.; Fabre, B.; Géneaux, R.; Légaré, F.; Petit, S.; et al. Attosecond-resolved photoionization of chiral molecules. Science 2017, 358, 1288–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattaneo, L.; Vos, J.; Bello, R.Y.; Palacios, A.; Heuser, S.; Pedrelli, L.; Lucchini, M.; Cirelli, C.; Martín, F.; Keller, U. Attosecond coupled electron and nuclear dynamics in dissociative ionization of H2. Nat. Phys. 2018, 14, 733–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalieri, A.L.; Müller, N.; Uphues, T.; Yakovlev, V.S.; Baltuška, A.; Horvath, B.; Schmidt, B.; Blümel, L.; Holzwarth, R.; Hendel, S.; et al. Attosecond spectroscopy in condensed matter. Nature 2007, 449, 1029–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neppl, S.; Ernstorfer, R.; Cavalieri, A.L.; Lemell, C.; Wachter, G.; Magerl, E.; Bothschafter, E.M.; Jobst, M.; Hofstetter, M.; Kleineberg, U.; et al. Direct observation of electron propagation and dielectric screening on the atomic length scale. Nature 2015, 517, 342–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locher, R.; Castiglioni, L.; Lucchini, M.; Greif, M.; Gallmann, L.; Osterwalder, J.; Hengsberger, M.; Keller, U. Energy-dependent photoemission delays from noble metal surfaces by attosecond interferometry. Optica 2015, 2, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasmi, L.; Lucchini, M.; Castiglioni, L.; Kliuiev, P.; Osterwalder, J.; Hengsberger, M.; Gallmann, L.; Krüger, P.; Keller, U. Effective mass effect in attosecond electron transport. Optica 2017, 4, 1492–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Månsson, E.P.; Sorensen, S.L.; Arnold, C.L.; Kroon, D.; Guénot, D.; Fordell, T.; Lépine, F.; Johnsson, P.; L’Huillier, A.; Gisselbrecht, M. Multi-purpose two- and three-dimensional momentum imaging of charged particles for attosecond experiments at 1 kHz repetition rate. Rev. Sci. Instruments 2014, 85, 123304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kienberger, R.; Krausz, F. Attosecond Metrology Comes of Age. Phys. Scr. Vol. T 2004, 110, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazansky, A.K.; Kabachnik, N.M. On the gross structure of sidebands in the spectra of laser-assisted Auger decay. J. Phys. B At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 2010, 43, 035601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maquet, A.; Taïeb, R. Two-colour IR+XUV spectroscopies: The “soft-photon approximation”. J. Mod. Opt. 2007, 54, 1847–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlström, J.M.; Guénot, D.; Klünder, K.; Gisselbrecht, M.; Mauritsson, J.; L’Huillier, A.; Maquet, A.; Taïeb, R. Theory of attosecond delays in laser-assisted photoionization. Chem. Phys. 2013, 414, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maquet, A.; Caillat, J.; Taïeb, R. Attosecond delays in photoionization: Time and quantum mechanics. J. Phys. B At. Mol. Phys. 2014, 47, 204004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bivona, S.; Bonanno, G.; Burlon, R.; Gurrera, D.; Leone, C. Signature of quantum interferences in above-threshold detachment of negative ions by a short infrared pulse. Phys. Rev. A 2008, 77, 051404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, S.D.; Ocello, M.L.; Arbó, D.G. Time-dependent theory of reconstruction of attosecond harmonic beating by interference of multiphoton transitions. Phys. Rev. A 2024, 110, 013104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramajo, A.A.; Della Picca, R.; Garibotti, C.R.; Arbó, D.G. Intra- and intercycle interference of electron emissions in laser-assisted XUV atomic ionization. Phys. Rev. A 2016, 94, 053404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewenstein, M.; You, L.; Cooper, J.; Burnett, K. Quantum field theory of atoms interacting with photons: Foundations. Phys. Rev. A 1994, 50, 2207–2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corkum, P.; Perry, M.D. Physics with intense laser pulses. Opt. Photonics News 1993, 4, 52–53. [Google Scholar]

- Arbó, D.G.; Miraglia, J.E.; Gravielle, M.S.; Schiessl, K.; Persson, E.; Burgdörfer, J. Coulomb-Volkov approximation for near-threshold ionization by short laser pulses. Phys. Rev. A 2008, 77, 013401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazansky, A.K.; Sazhina, I.P.; Kabachnik, N.M. Angle-resolved electron spectra in short-pulse two-color XUV+IR photoionization of atoms. Phys. Rev. A 2010, 82, 033420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bivona, S.; Bonanno, G.; Burlon, R.; Leone, C. Two-color ionization of hydrogen by short intense pulses. Laser Phys. 2010, 20, 2036–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbó, D.G.; Ishikawa, K.L.; Schiessl, K.; Persson, E.; Burgdörfer, J. Intracycle and intercycle interferences in above-threshold ionization: The time grating. Phys. Rev. A 2010, 81, 021403(R). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbó, D.G.; Ishikawa, K.L.; Schiessl, K.; Persson, E.; Burgdörfer, J. Diffraction at a time grating in above-threshold ionization: The influence of the Coulomb potential. Phys. Rev. A 2010, 82, 043426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuser, S.; Jiménez Galán, Á.; Cirelli, C.; Marante, C.; Sabbar, M.; Boge, R.; Lucchini, M.; Gallmann, L.; Ivanov, I.; Kheifets, A.S.; et al. Angular dependence of photoemission time delay in helium. Phys. Rev. A 2016, 94, 063409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramajo, A.A.; Della Picca, R.; López, S.D.; Arbó, D.G. Intra- and intercycle interference of angle-resolved electron emission in laser-assisted XUV atomic ionization. J. Phys. B At. Mol. Phys. 2018, 51, 055603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busto, D.; Vinbladh, J.; Zhong, S.; Isinger, M.; Nandi, S.; Maclot, S.; Johnsson, P.; Gisselbrecht, M.; L’Huillier, A.; Lindroth, E.; et al. Fano’s propensity rule in angle-resolved attosecond pump-probe photoionization. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2019, 123, 133201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolino, M.; Busto, D.; Zapata, F.; Dahlström, J.M. Propensity rules and interference effects in laser-assisted photoionization of helium and neon. J. Phys. B At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 2020, 53, 144002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramajo, A.A.; Della Picca, R.; Arbó, D.G. Electron emission perpendicular to the polarization direction in laser-assisted XUV atomic ionization. Phys. Rev. A 2017, 96, 023414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korneev, P.A.; Popruzhenko, S.V.; Goreslavski, S.P.; Yan, T.M.; Bauer, D.; Becker, W.; Kübel, M.; Kling, M.F.; Rödel, C.; Wünsche, M.; et al. Interference Carpets in Above-Threshold Ionization: From the Coulomb-Free to the Coulomb-Dominated Regime. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 108, 223601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korneev, P.A.; Popruzhenko, S.V.; Goreslavski, S.P.; Becker, W.; Paulus, G.G.; Fetić, B.; Milošević, D.B. Interference structure of above-threshold ionization versus above-threshold detachment. New J. Phys. 2012, 14, 055019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, A.S.; Figueira de Morisson Faria, C.; Lai, X.; Sun, R.; Liu, X. Spiral-like holographic structures: Unwinding interference carpets of Coulomb-distorted orbits in strong-field ionization. Phys. Rev. A 2020, 102, 033111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, X.M.; Chu, S.I. Theoretical study of multiple high-order harmonic generation by intense ultrashort pulsed laser fields: A new generalized pseudospectral time-dependent method. Chem. Phys. 1997, 217, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, X.M.; Chu, S.I. Time-dependent approach to high-resolution spectroscopy and quantum dynamics of Rydberg atoms in crossed magnetic and electric fields. Phys. Rev. A 2000, 61, 031401(R). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, X.M.; Lin, C.D. Empirical formula for static field ionization rates of atoms and molecules by lasers in the barrier-suppression regime. J. Phys. B At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 2005, 38, 2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macri, P.A.; Miraglia, J.E.; Grabielle, M.S.; Colavecchia, F.D.; Garibotti, C.R.; Gasaneo, G. Theory with correlations for ionization in ion-atom collisions. Phys. Rev. A 1998, 57, 2223–2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolkow, D. Uber eine Klasse von Lösungen der Diracschen Gleichung. Z. Für Phys. 1935, 94, 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picca, R.D.; Fiol, J.; Fainstein, P.D. Factorization of laser-pulse ionization probabilities in the multiphotonic regime. J. Phys. B At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 2013, 46, 175603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Picca, R.; Ciappina, M.F.; Lewenstein, M.; Arbó, D.G. Laser-assisted photoionization: Streaking, sideband, and pulse-train cases. Phys. Rev. A 2020, 102, 043106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbó, D.G.; Dimitriou, K.I.; Persson, E.; Burgdörfer, J. Sub-Poissonian angular momentum distribution near threshold in atomic ionization by short laser pulses. Phys. Rev. A 2008, 78, 013406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Véniard, V.; Taïeb, R.; Maquet, A. Two-Color Multiphoton Ionization of Atoms Using High-Order Harmonic Radiation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1995, 74, 4161–4164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guénot, D.; Klünder, K.; Arnold, C.L.; Kroon, D.; Dahlström, J.M.; Miranda, M.; Fordell, T.; Gisselbrecht, M.; Johnsson, P.; Mauritsson, J.; et al. Photoemission-time-delay measurements and calculations close to the 3s-ionization-cross-section minimum in Ar. Phys. Rev. A 2012, 85, 053424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, L.B. Strong-field approximation in laser-assisted dynamics. Am. J. Phys. 2005, 73, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbó, D.G.; López, S.D.; Burgdörfer, J. Semiclassical strong-field theory of phase delays in ω–2ω above-threshold ionization. Phys. Rev. A 2022, 106, 053101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolino, M.; Dahlström, J.M. Multiphoton interaction phase shifts in attosecond science. Phys. Rev. Res. 2021, 3, 013270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharti, D.; Atri-Schuller, D.; Menning, G.; Hamilton, K.R.; Moshammer, R.; Pfeifer, T.; Douguet, N.; Bartschat, K.; Harth, A. Decomposition of the transition phase in multi-sideband schemes for reconstruction of attosecond beating by interference of two-photon transitions. Phys. Rev. A 2021, 103, 022834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharti, D.; Srinivas, H.; Shobeiry, F.; Bondy, A.; Saha, S.; Hamilton, K.; Moshammer, R.; Pfeifer, T.; Bartschat, K.; Harth, A. Multi-sideband interference structures by high-order photon-induced continuum-continuum transitions in helium. Phys. Rev. A 2024, 109, 023110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueira de Morisson Faria, C.; Schomerus, H.; Becker, W. High-order above-threshold ionization: The uniform approximation and the effect of the binding potential. Phys. Rev. A 2002, 66, 043413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).