Abstract

Measuring supermassive black hole (SMBH) masses is fundamental to understanding active galactic nuclei (AGN) and their coevolution with host galaxies. Among existing techniques, H2O megamaser observations with Very Long Baseline Interferometry (VLBI) provide the most direct and geometric determinations of SMBH masses by tracing molecular gas in sub-parsec Keplerian disks. Over the past two decades, the Megamaser Cosmology Project (MCP) has surveyed thousands of nearby AGNs and obtained high-sensitivity VLBI maps of dozens of maser disks that lead to accurate SMBH masses with uncertainties typically below 10%. In this paper, we present a comprehensive review that summarizes the essential elements required to obtain accurate black hole masses with the H2O megamaser technique—including the physical conditions for maser excitation, observational requirements, disk modeling, and sources of SMBH mass uncertainty—and we discuss the implications of maser-based measurements for exploring SMBH demographics. In particular, we will show that maser-derived black hole masses, largely free from the systematic biases of stellar or gas-dynamical methods, provide critical anchors at the low-mass end of the SMBH population (MBH∼107M⊙), and reveal possible deviations from the canonical MBH–σ∗ relation. With forthcoming spectroscopic surveys and advances in millimeter/submillimeter VLBI, the maser technique promises to extend precise dynamical mass measurements to both larger local samples and high-redshift galaxies.

1. Introduction

The accurate determination of supermassive black hole (SMBH) masses has been one of the central goals of extragalactic astronomy over the past three decades. Black hole (BH) mass is a fundamental parameter that underpins the physics of active galactic nuclei (AGNs), regulates accretion processes, and serves as a cornerstone for scaling relations that link SMBHs with the growth and evolution of their host galaxies. From the early stellar- and gas-dynamical measurements in nearby galaxies [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12] to reverberation mapping (RM) and virial estimation [13,14,15,16] in Type 1 AGNs and luminous quasars1, a wide range of methods have been developed to probe the demographics of SMBHs across cosmic time. Yet, despite remarkable progress, each of these techniques faces systematic limitations, either due to spatial resolution, modeling degeneracies, or reliance on indirect proxies.

In BH mass measurements with stellar dynamical modeling, analysis techniques have evolved significantly, from early isotropic and two-integral approximations [1,2,3] to sophisticated orbit-superposition models that are now both axisymmetric and triaxial [4,6,17]. Despite these advances, systematic uncertainties could remain at the level of tens of percent, arising mainly from assumptions about orbital anisotropy, the influence of dark matter, spatial gradients in the stellar mass-to-light ratio or initial mass function IMF, and intrinsic galaxy shape (axisymmetry versus triaxiality). For instance, some more recent work demonstrates that allowing for spatially varying IMFs can shift mass estimates by ∼15–50% [18]. Encouragingly, tests using mock galaxies indicate that triaxial orbit models can recover MBH, mass profiles, and anisotropy to within ∼5–10% under favorable conditions when smoothing and regularization are properly tuned [19]. Consequently, modern analyses must explicitly explore model degeneracies and systematic effects to approach percent-level precision in MBH.

In gas-dynamical modeling using ionized gas, e.g., Ref. [20], the most accurate BH mass measurements have achieved uncertainties of ∼30% in favorable cases, e.g., Ref. [7]. Nevertheless, it is known that mitigating systematic uncertainty arising from the intrinsic velocity dispersion near the galaxy nucleus, e.g., Refs. [7,20] remains difficult. If the dispersion reflects pressure support, the observed rotation speed will underestimate the true circular velocity—the so-called asymmetric drift—resulting in a biased, lower estimate of MBH. Fortunately, recent high-angular-resolution observations with ALMA using cold molecular gas in early type galaxies (ETGs) have substantially improved this, allowing MBH determinations with statistical uncertainties as low as ≲10–15%. The improvement in accuracy results from the fact that a cold molecular gas tends to have a smaller turbulent velocity dispersion than the ionized gas in a galaxy, making it a better tracer of the orbital velocity and enabling accurate dynamical modeling more easily. [21,22,23]. In extreme cases, CO-based modeling can achieve formal uncertainties of ≲1% if the uncertainty in galaxy distance is ignored [24]. However, this level of accuracy is attainable only when the disk inclination is moderate or low. For highly inclined systems such as NGC 1332 [23], insufficient spatial resolution along the projected minor axis of the galaxy leads to severe beam-smearing, which can introduce uncertainties approaching a factor of ∼2 in MBH, e.g., Ref. [23].

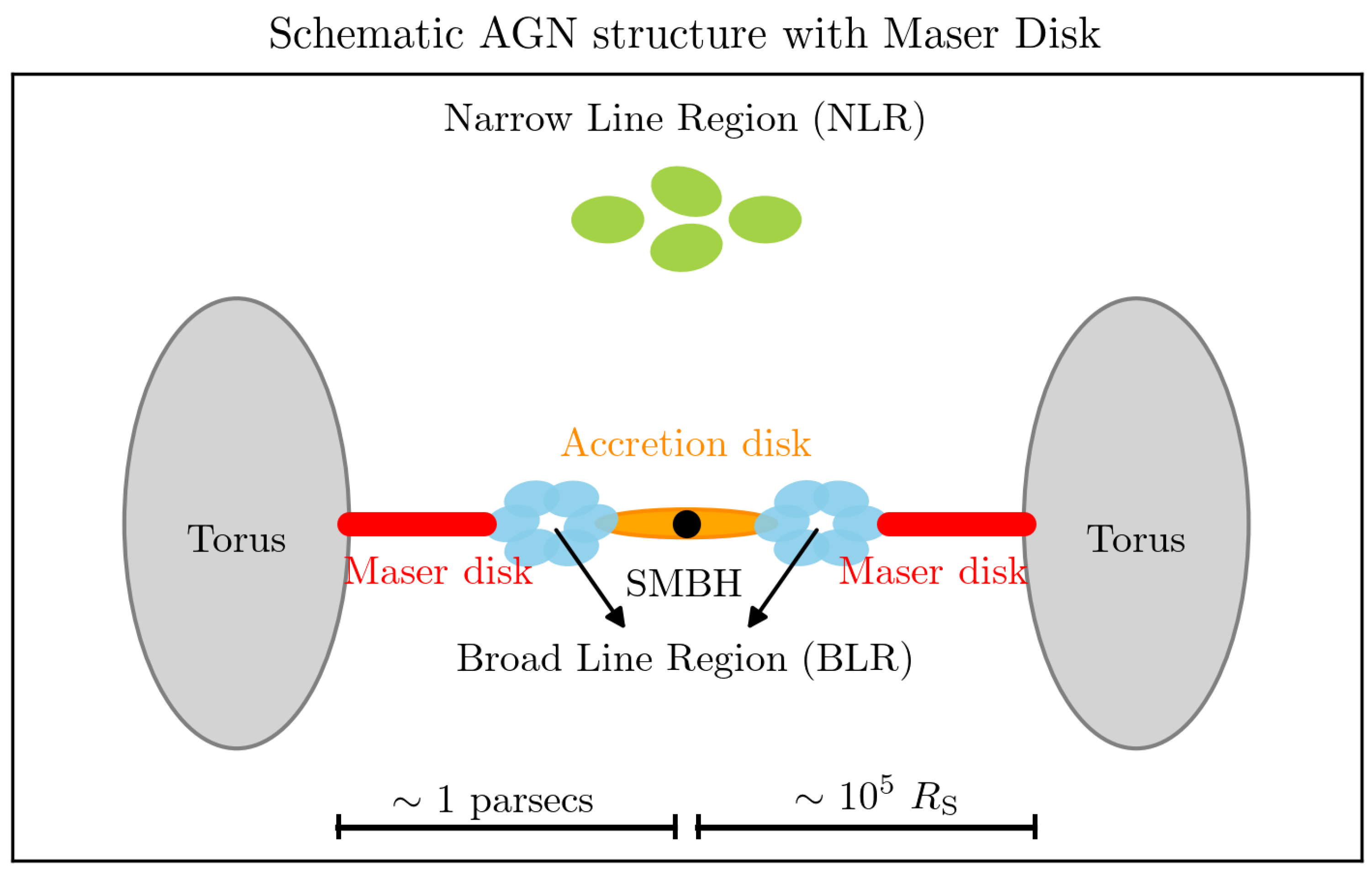

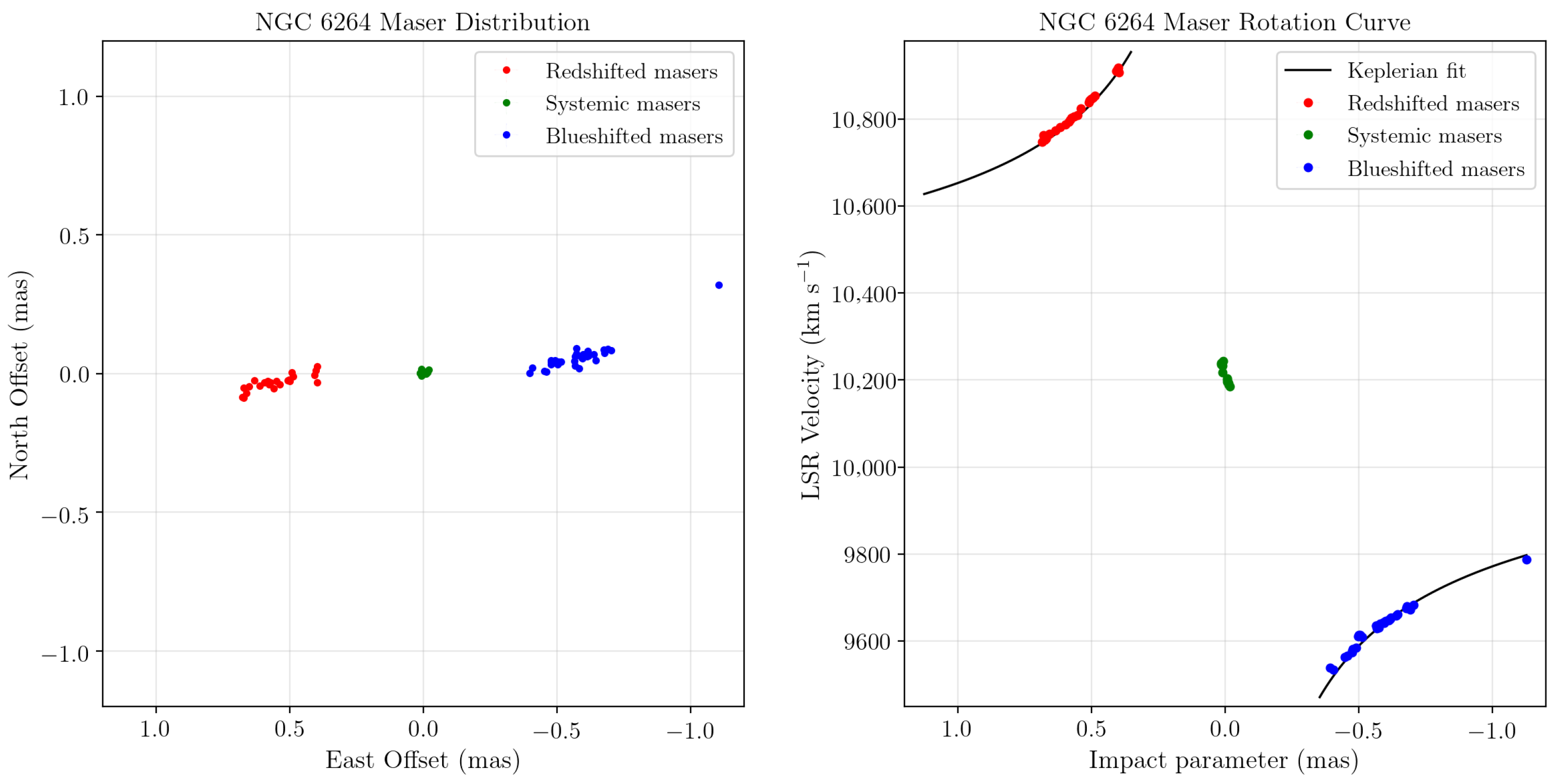

Among the available techniques, the use of H2O megamasers provides a uniquely robust and complementary approach to measure SMBH masses. First established through VLBI observations of NGC 4258 [25,26], the method is most effectively applied to maser-host galaxies that predominantly harbor Type II AGNs. In this prototypical maser galaxy, extragalactic water megamasers at 22 GHz trace molecular gas orbiting within a few tenths of a parsec of the central SMBH, where the gravitational potential is overwhelmingly dominated by the black hole (see Figure 1 for a schematic illustration of a maser disk within the standard AGN paradigm). When the masing disk is oriented close to edge-on, the resultant long amplification path length gives rise to highly beamed, luminous maser emission (i.e., megamaser), allowing individual maser spots to be precisely imaged by VLBI, yielding spatial information at ∼10 microarcsecond precision, e.g., Refs. [27,28]. The resulting Keplerian rotation curves (see Figure 2 for an example) provide what are arguably the most compelling and least ambiguous measurements of SMBH masses beyond the Milky Way.

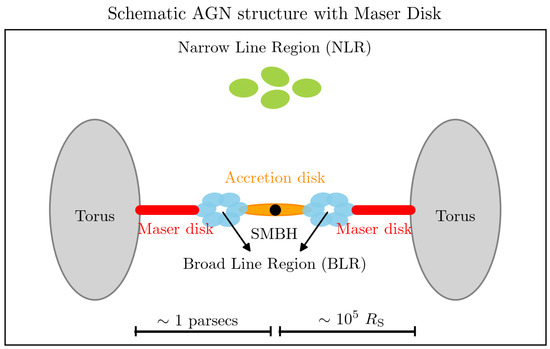

Figure 1.

A schematic illustration of a maser disk within the standard AGN paradigm, highlighting its location relative to the torus, broad-line region (BLR), narrow-line region (NLR), and the central black hole. Past X-ray observations suggest that a maser disk may be the inner extension of an AGN torus [29]. The inner boundary of a maser disk is typically consistent with the dust sublimation radius and has a radius of ∼1 × 105 RS [30], where RS indicates the Schwarzschild radius of the center black hole.

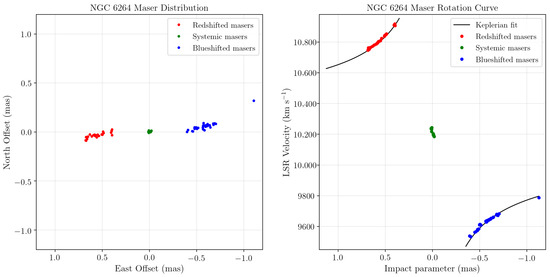

Figure 2.

Left Panel: VLBI map of the H2O maser emission in NGC 6264 [31], showing the high-velocity (red and blue) and systemic (green) maser components of the nearly edge-on maser disk. This source represents the type of “gold-standard” maser disk suitable for both black hole mass and Hubble constant measurement. Right Panel: the position–velocity diagram of the maser disk, with the black curve showing the best-fit Keplerian rotation curve.

The robustness of these measurements arises from the fact that masers probe gas well within the gravitational sphere of influence, with negligible contamination from the stellar mass distribution or non-gravitational forces. As a result, they avoid many of the modeling degeneracies, e.g., Refs. [7,32] that complicate stellar or gas dynamical methods. Maser-based black hole mass (MBH) determinations are therefore among the most accurate absolute measurements currently achievable. Notably, the SMBH masses obtained via this technique typically fall in the range of MBH ≈ (0.2 − 6.0) × 107M⊙, providing critical constraints at the low-mass end of the black hole demographic distribution (see Section 6), a regime that is less readily probed by stellar- and gas-dynamical methods [10].

Over the past twenty years, the Megamaser Cosmology Project (MCP), e.g., Refs. [33,34,35,36,37,38] has extended this technique to numerous active galaxies hosting nuclear H2O megamaser emission. These discoveries have been enabled by long-term surveys with the Green Bank Telescope (GBT), which has targeted more than ≳4800 galaxies within z∼0.05 e.g., Ref. [39], focusing on narrow-emission line AGNs. This extensive campaign has uncovered several dozen “maser galaxies” with the characteristic triple-peaked spectra, e.g., Ref. [27] indicative of nearly edge-on masing disks, suitable for dynamical black hole mass measurements. Follow-up VLBI imaging of the best candidates has since tripled the number of secure maser-based SMBH mass determinations, e.g., Ref. [28] over the last two decades, offering new insights into the coevolution of galaxies and their central black holes and constraining the low-mass end of the SMBH population in late-type galaxies, e.g., Ref. [40].

The goal of this paper is to provide a concise but comprehensive review of maser-based black hole mass measurements. The review is organized as follows: Section 2 discusses the basic physical principles underlying water masers and explores how the necessary conditions for maser action leads to the characteristic spectral features of extragalactic H2O disk megamasers. Section 3 summarizes past maser surveys and discusses strategies for future searches. Section 4 describes the VLBI techniques required for maser observations and Section 5 presents the modeling frameworks and error budgets, including warp modeling, non-ideal effects, and other uncertainties. In addition, it highlights key results of maser-based MBH measurements conducted in the past two decades. Section 6 compares maser masses with other techniques and explores the role of maser-based black hole masses in understanding SMBH demographics. Section 7 discusses future prospects, including applications at high redshift, new instrumentation, and expansion of the maser sample. Finally, Section 8 summarizes the main conclusions of this review.

2. The Physical Conditions for Maser Pumping in a Circumnuclear Gas Disk

The word maser stands for , the microwave analogue of a laser that arises naturally under astrophysical conditions. In the interstellar medium, the transition of water at 22 GHz can be collisionally excited in warm molecular clouds. When the medium is optically thick to far-infrared radiation, the level populations of H2O in a saturated maser are controlled mainly by the local gas properties: the molecular hydrogen temperature (), dust temperature (Td), molecular hydrogen density (), and the relative abundance of water, [30,41]. Among these, and are the most decisive for establishing population inversion, with optimal conditions in the ranges K and cm−3, e.g., Refs. [41,42,43,44,45].

A lower limit of roughly Tmin∼400 K is needed to populate the 616 level, which lies 643 K above the ground state. At these temperatures, gas-phase chemistry also enhances the water abundance to through the reactions O + H2→ OH + H and OH + H2 → H2O + H, e.g., Refs. [42,46]. Densities above 107 cm−3 are required to make collisional pumping efficient, but if the density exceeds the critical value (ncrit∼1011 cm−3), collisional de-excitation suppresses the inversion.

Population inversion alone is not sufficient for sustained maser emission. Maser action is accompanied by infrared line emission. If these IR photons are trapped within the masing medium, they effectively lengthen the radiative lifetimes of the masing levels, pushing the system toward thermalization [44] and quenching the maser action. Thus, it is preferential for masing regions to possess geometries that allow IR photons to escape efficiently (favoring flattened or elongated structures). Alternatively, including internal absorbers such as cold dust grains [44,47,48] can also help sustain maser action and boost maser output: if the grains are cooler than the gas by ΔT∼50–100 K, they absorb far-infrared water lines trapped within the cloud and prevent quenching, enabling a larger fraction of H2O molecules to remain inverted [30,44,47,48]. This mechanism explains the high luminosities [49] observed in extragalactic water megamasers.

Maintaining the required gas temperatures demands an external heating source. X-ray illumination from the active nucleus is widely considered the dominant mechanism in circumnuclear disks, placing the masing gas in an X-ray-dominated region (XDR) [42,43,44,50,51]. Other processes have also been proposed, such as spiral shocks propagating through the disk [52], though predicted velocity drifts in high-velocity maser components are not observed [53]. Alternatively, viscous dissipation from magnetorotational instability (MRI) turbulence could also be the heating source, and it is thought that this mechanism may play a role in some sources such as NGC 4258 [54,55].

It is worth stressing that sustained population inversion by itself does not guarantee observable extragalactic maser emission. Detectability requires velocity coherence along the line of sight through the inverted medium, maintained over path lengths long enough to achieve substantial amplification. In disk masers such as NGC 4258, the longest coherent paths arise along the midline of the disk on the redshifted and blueshifted sides, and also toward the central black hole where the projected velocity approaches zero. Because maser emission is highly beamed and amplification depends critically on path length, maser disks are visible only when the disk is oriented close to edge-on. This geometry not only maximizes the gain but also naturally produces the characteristic triple-peaked spectra—systemic masers, plus redshifted and blueshifted complexes. The requirement of near edge-on alignment explains why megamaser disks are most often found in Type II AGNs or Seyfert 2 galaxies, where obscuration of the nucleus is consistent with an edge-on disk orientation in the standard paradigm of AGNs.

3. H2O Megamaser Surveys and Strategies for Enhancing Detection Rates

3.1. Survey Scope and Target Selection

To identify disk maser hosts analogous to NGC 4258—systems that enable precise dynamical measurements of SMBH masses and geometric distances—extensive, systematic surveys for extragalactic H2O megamasers are essential. The most comprehensive effort in this direction has been undertaken by the MCP, which has produced the largest and most complete catalog of galaxies systematically surveyed for 22 GHz water maser emission.

The MCP sample includes more than 4800 galaxies observed with the Green Bank Telescope (GBT) prior to September 2016 [39]. These targets are primarily narrow-emission-line AGNs, selected from major spectroscopic surveys such as the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS) [56,57], the Two Micron All Sky Survey (2MASS) Redshift Survey [58], the 2dF Galaxy Redshift Survey [59], and the 6dF Galaxy Survey [60]. Candidate AGNs were identified based on their optical emission-line ratios using the Baldwin–Phillips–Terlevich (BPT) diagnostic diagram [61], without imposing additional criteria such as color or magnitude. The redshifts of the MCP galaxies span 0 < z < 0.07, encompassing the local Universe where sensitive maser searches are feasible.

As a result of these extensive GBT surveys, the number of known H2O maser galaxies has increased by roughly a factor of nine over the past two decades, bringing the total to about 180 detections. These sources are cataloged in the public MCP database (https://safe.nrao.edu/wiki/bin/view/Main/PublicWaterMaserList, accessed on 25 October 2025). Despite the thousands of galaxies surveyed, the overall maser detection rate remains relatively low, typically around 3%, reflecting the rarity of the physical conditions and geometric orientations required for maser amplification in extragalactic sources.

As a complementary effort to the MCP, van den Bosch et al. [62] carried out a targeted maser survey of nearby galaxies drawn from the HETMGS catalog [63]. Whereas the MCP primarily targets narrow-emission-line AGNs in late-type galaxies, the HETMGS sample is dominated by early-type galaxies (ETGs) specifically selected for having large gravitational spheres of influence, making them suitable for stellar- or gas-dynamical black hole mass measurements. The aim was to identify potential disk maser systems whose MBH could be directly compared with masses obtained using traditional dynamical methods. Although no maser detections were made among 87 ETGs hosting low-luminosity AGNs (LLAGNs), the survey provides valuable constraints on megamaser incidence in galaxies with different morphologies.

The absence of maser detections in the HETMGS sample likely reflects key physical differences between ETGs and late-type maser hosts. In particular, at low accretion rates and high black hole masses (), maser disks in ETGs may become too extended to remain stable or sufficiently heated. Additionally, the X-ray luminosities for LLAGNs in ETGs may often fall below the minimum threshold (LX∼1040 erg s−1) typically required to drive maser excitation, e.g., Refs. [39,62]. These results reinforce the view that efficient maser searches should focus primarily on Type II AGNs hosted by late-type galaxies.

3.2. Discovery of Disk Masers and Spectral Signatures

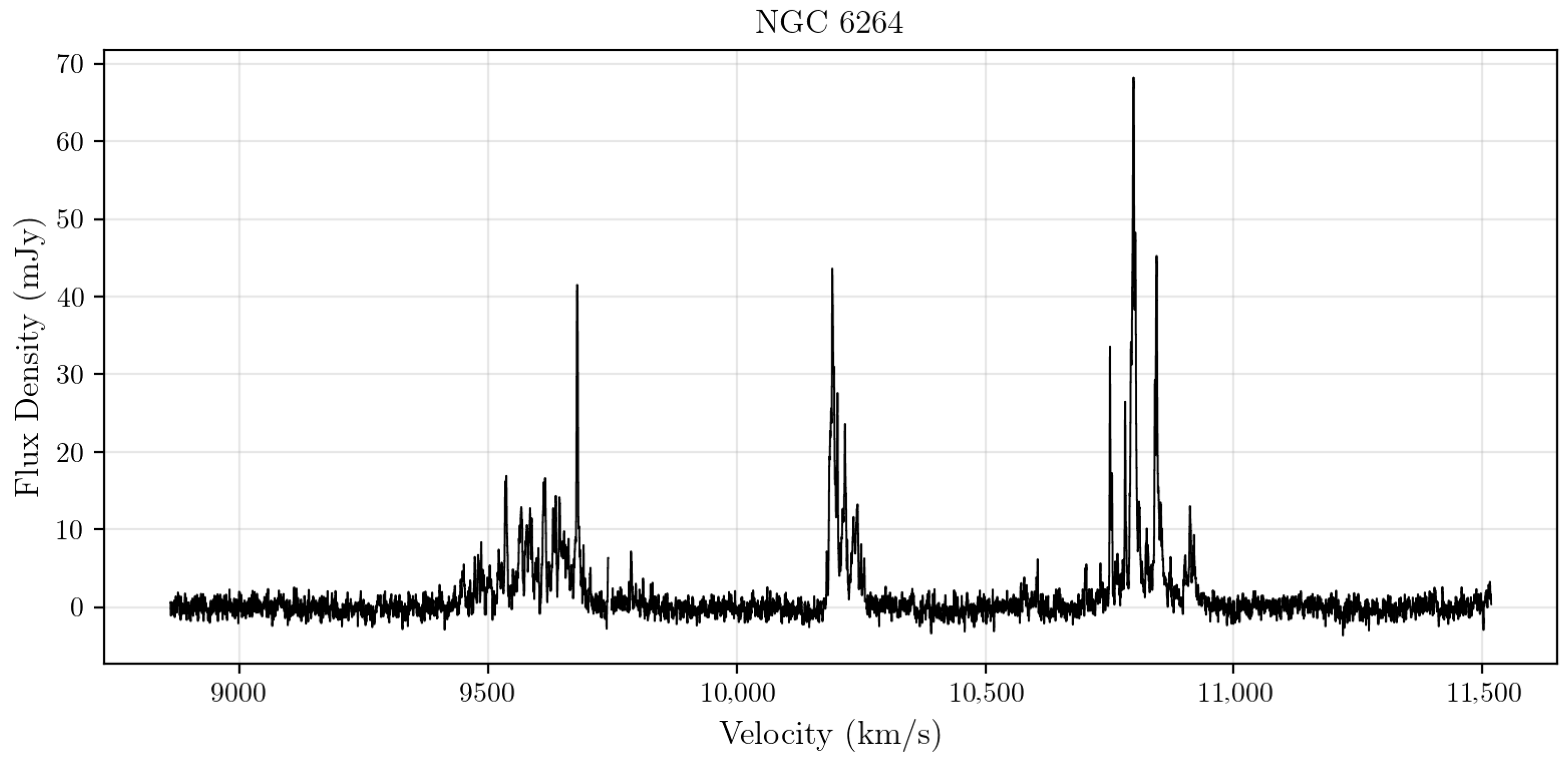

The H2O megamasers detected in MCP surveys exhibit a wide variety of spectral morphologies that reflect different physical origins. Among all detections, only about 1%, e.g., Ref. [39] display the characteristic “triple-peaked” spectral profile (see Figure 3), strongly indicative of an NGC 4258-like circumnuclear disk. In these systems, the maser spectrum shows three distinct complexes corresponding to the redshifted, systemic, and blueshifted components of a rotating Keplerian disk, e.g., Ref. [27]. These disk masers are the most valuable systems for precise dynamical measurements of SMBH masses and, in favorable cases, geometric distance determinations.

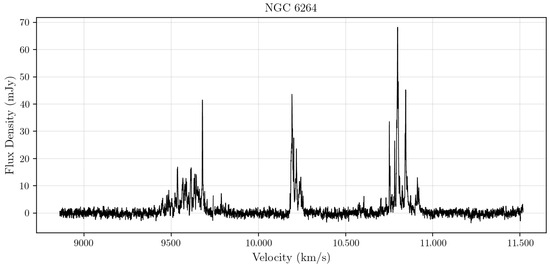

Figure 3.

A representative H2O maser spectrum of the disk maser system NGC 6264 obtained by the Green Bank Telescope. This spectrum displays the characteristic “triple-peaked” spectral profile indicative of an NGC 4258-like circumnuclear disk. The horizontal axis shows the velocity in the optical convention with respect to the LSR frame.

In addition to these canonical triple-peaked spectra, a subset of maser galaxies exhibit only two distinct line complexes. Examples include Mrk 1210 [64] and the Circinus galaxy [65], where the single-dish spectra show two dominant maser groups—one blueshifted and one redshifted with respect to the systemic velocity (Vsys)—but no strong emission near Vsys. Occasionally, weak maser features are detected between these velocity groups, typically within 100 km s−1 of Vsys, though their nature is often ambiguous. It is difficult to determine whether these weak lines represent genuine systemic masers associated with gas along the line of sight to the central black hole, or simply low-level emission near the edges of the high-velocity components.

Because they lack a well-defined systemic maser group, such double-peaked systems are not ideal for determining a precise Hubble constant at the 10% level (e.g., Refs. [31,35,37]). Nevertheless, if part of the emission arises from a rotating disk, these sources can still yield reliable SMBH masses—with accuracy sufficient to constrain the MBH–σ∗ relation, e.g., Refs. [6,10,40]. A notable example is the Circinus Galaxy, whose masers clearly trace rotation in a warped, edge-on molecular disk [65].

A third class consists of systems whose 22 GHz spectra display a single broad maser line, such as NGC 1052 [66] and Mrk 348 [67], with full widths at half maximum (FWHM) of ≳100–200 km s−1. These maser systems are often interpreted as the result of interactions between radio jets and molecular clouds. The line centroids (vc) of such masers are often displaced from the systemic velocity of the host galaxy by more than 100 km s−1 (i.e., |vc – vsys| ≳ 100 km s−1), implying that the masing gas is associated with an off-nuclear cloud shocked by a receding or approaching jet (e.g., Ref. [68]). Because these masers do not trace orderly rotation around the central black hole, they cannot be used for precise SMBH mass measurements.

To facilitate comparison among different systems, masers are commonly classified into three categories based on both their spectral characteristics and isotropic luminosities: kilomasers, megamasers, and disk masers. Kilomasers have isotropic luminosities < 10 L⊙ and are generally associated with star-forming regions, unrelated to AGN activity. Megamasers, defined by > 10 L⊙, encompass both disk masers and non-disk (e.g., jet or outflow) systems, where disk masers represent the subset of megamasers whose spectra exhibit the distinctive structures characteristic of sub-parsec-scale circumnuclear disks. A comprehensive list of isotropic H2O luminosities for all known maser galaxies is provided in Table 1 of Kuo et al. [49].

3.3. Strategies for Enhancing Detection Rates

Although thousands of galaxies have been surveyed for 22 GHz water maser emission, the overall detection rate of extragalactic H2O masers remains low—typically only ∼3% for megamasers in general and ≲1% for disk masers suitable for precise dynamical modeling, e.g., Refs. [39,49]. This scarcity poses a serious challenge: without a sufficient number of high-quality disk maser systems, it is difficult to construct robust maser-based black hole mass samples to refine the MBH–σ∗ relation or to achieve a high-precision determination of the Hubble constant. Consequently, the development of effective strategies to improve maser detection rates has become a central focus of recent work.

To improve efficiency, researchers have sought empirical correlations between the presence of megamasers and host galaxy properties observable in other wavelength regimes. Various selection strategies have been explored based on optical, mid-infrared (MIR), X-ray observations, each investigating different aspects of the AGN environment believed to favor maser production.

3.3.1. Optical Selection

Optical spectroscopy remains the traditional starting point for identifying potential maser hosts. The MCP’s initial surveys relied on narrow-emission-line AGNs selected using the Baldwin–Phillips–Terlevich (BPT) diagnostic diagram [61], which distinguishes Seyfert 2 and LINER nuclei from star-forming galaxies based on emission-line ratios. Within this framework, several optical indicators have been proposed to correlate with maser activity.

In particular, a higher [O III] λ5007 luminosity (L[OIII]) has been shown to correspond to an increased likelihood of detecting maser emission. Empirically, the maser detection rate Rmaser increases from ∼1% at erg s−1 to ∼9% at erg s−1, ultimately reaching ∼15% at erg s−1 (see Figure 3 in [69]). This steep rise in detection probability with increasing is consistent with the expectation that more luminous AGNs generate stronger nuclear radiation fields, which may promote the heating of dense molecular gas in the parsec-scale disk or torus and thus favor maser excitation.

However, using [O III] luminosity as a selection criterion has practical limitations. One challenge is that not all galaxies in spectroscopic AGN catalogs have reliable [O III] measurements or extinction-corrected [O III] luminosities published, limiting the applicability of [O III]-based selection. For those galaxies, alternative indicators (e.g., infrared, X-ray, or radio properties) become more important in prioritizing maser search candidates.

3.3.2. Mid-Infrared (MIR) Indicators

Mid-infrared selection has proven to be among the most promising routes for improving maser detection efficiency, e.g., Ref. [70]. Because MIR emission traces reprocessed radiation from warm dust in the obscuring torus, it is less affected by extinction and more representative of the intrinsic AGN power.

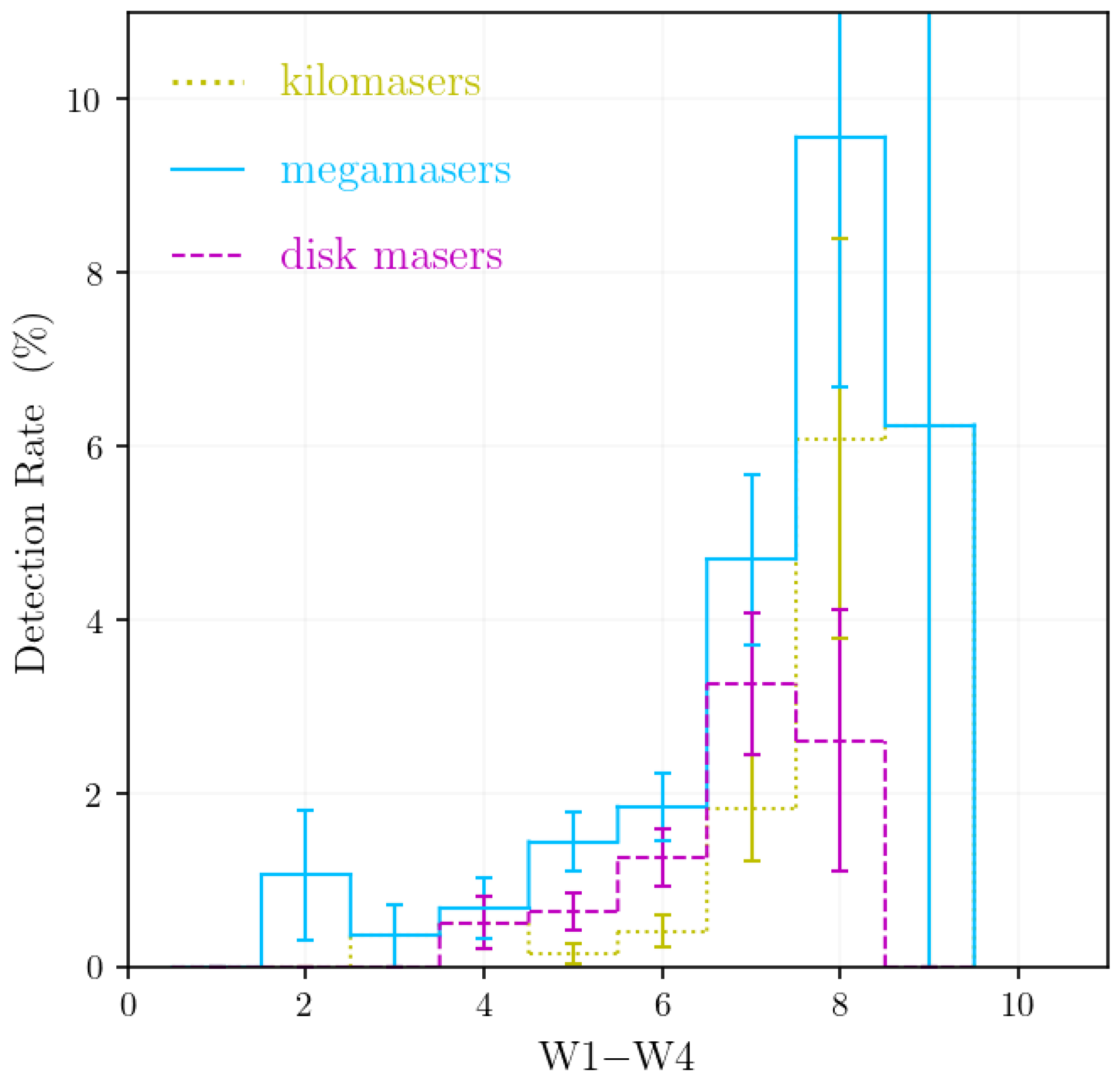

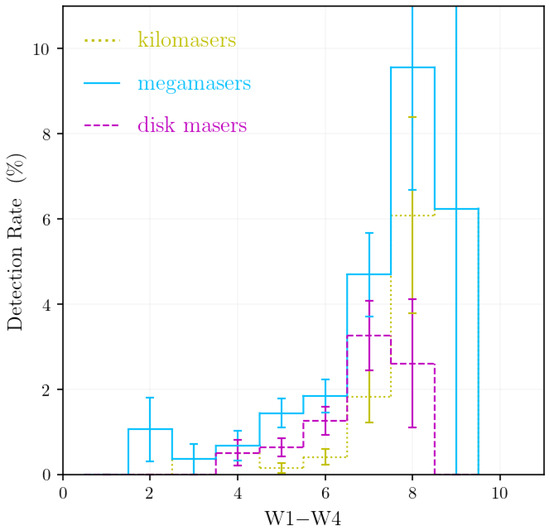

In Kuo et al. [49], cross-matching the MCP sample with photometry from Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE)—available for the vast majority of MCP galaxies—revealed that maser-host galaxies exhibit systematically redder MIR colors (e.g., larger W1–W2 and W1–W4) than non-maser AGNs. These redder colors are indicative of stronger hot-dust emission and higher levels of nuclear obscuration, both favorable conditions for maser excitation. By applying simple color-based thresholds such as W1–W2 > 0.5 or W1–W4 > 7, the expected maser detection rate can increase by nearly an order of magnitude compared with unfiltered, optically selected samples (see Figure 4 for an example). Furthermore, combining MIR colors with MIR luminosity and optical color information can further enhance predictive power, efficiently prioritizing high-probability candidates.

Figure 4.

The maser detection rates Rmaser as a function of mid-IR WISE color W1–W4. For all types of maser systems, e.g., Ref. [49], their detection rates increase rapidly with the W1–W4 color.

Despite its success, MIR selection has several important caveats. First, not all IR-luminous or red sources host masers. Starburst galaxies and dust-rich mergers can exhibit MIR colors similar to obscured AGNs, introducing significant contamination into MIR-selected samples. In addition, Type 1 AGNs—which are also bright in the mid-infrared—rarely host maser emission, as their relatively face-on orientation prevents the long, velocity-coherent amplification paths required for strong maser gain. As emphasized in Kuo et al. [70], pre-selecting Type II AGNs before applying MIR color criteria is essential for the method to be effective. Without such filtering, MIR-selected samples can include a substantial fraction of star-forming galaxies and unobscured AGNs, leading to a suppressed overall maser detection rate even when nominal color cuts are applied.

3.3.3. X-Ray Properties

Because water maser emission is thought to arise in X-ray-dominated regions (XDRs) within the circumnuclear molecular disk, X-ray observations provide crucial diagnostics of the physical conditions associated with maser excitation. In particular, the nuclear X-ray luminosity and the line-of-sight absorbing column density (NH) offer direct probes of the ionization state, heating rate, and geometry of the obscuring material.

Kuo et al. [39] systematically examined the X-ray properties of known maser galaxies and found that they generally exhibit high column densities (NH ≳ 1023–1024 cm−2), frequently entering the Compton-thick regime. Such large NH values are consistent with an edge-on molecular torus or disk geometry, in which the line of sight passes through the dense midplane of the circumnuclear gas. These findings, which are also found by Castangia et al. [71] and Panessa et al. [72], strongly support the physical connection between heavy obscuration and maser amplification: the same geometry that produces strong X-ray absorption also provides long velocity-coherent path lengths for maser gain.

Selecting galaxies with hard X-ray detections and large column densities is therefore an effective way to significantly increase the likelihood of identifying maser hosts. However, this approach faces significant practical challenges. High-quality X-ray spectra are observationally expensive to obtain, and only a small fraction of optically selected AGNs have well-constrained NH measurements in the literature. Consequently, while X-ray diagnostics are physically powerful for boosting maser detection rates, their limited availability currently restricts their use as a large-scale pre-selection tool for maser surveys. Future wide-area, high-sensitivity X-ray missions will be instrumental in expanding this avenue for target identification.

3.3.4. Combined Multi-Wavelength Approaches

Although optical, mid-infrared, and X-ray selections have each been shown to improve maser detection efficiency, and no single method alone can serve as a universally optimal strategy for all AGN populations. Each wavelength regime provides complementary information: optical emission lines trace ionized gas in the narrow-line region; mid-infrared emission probes reprocessed radiation from warm dust in the obscuring torus; and X-rays reveal the degree of nuclear obscuration and gas column density. When considered together, these diagnostics offer a more complete picture of the physical and geometrical conditions that favor maser activity.

In practice, the effectiveness of a given selection criterion depends strongly on data availability and survey design. For example, [O III] luminosities are readily available for optically characterized AGNs but such information may not be well available for X-ray-selected AGNs. Conversely, mid-IR photometry from WISE covers nearly all nearby galaxies, but color-based selection alone can be contaminated by star-forming systems or unobscured Type 1 AGNs. X-ray measurements provide the most direct probe of obscuration, yet high-quality spectra exist for only a fraction of known AGNs. Hence, the most efficient approach is to apply these diagnostics in combination, tailoring the selection strategy to the subset of galaxies for which reliable measurements at each wavelength are available.

Despite current limitations in data completeness, the rapid growth of multi-wavelength survey archives and the increasing use of machine-learning techniques may transform future maser searches. By combining heterogeneous datasets and learning from known maser hosts, these approaches may efficiently prioritize high-probability targets, thereby significantly improving detection yields in upcoming large-scale surveys.

4. The VLBI Observations for H2O Megamasers

Very Long Baseline Interferometry (VLBI) observations are essential for converting spectral detections of H2O megamasers into precise dynamical measurements of SMBH masses. Maser-based mass determinations rely on accurately mapping the positions and line-of-sight velocities of maser spots distributed in a sub-parsec-scale disk, thereby constructing a rotation curve that directly reflects the gravitational potential of the central SMBH. Achieving such accuracy requires not only high angular resolution but also astrometric precision on the order of tens of microarcseconds.

4.1. Observational Requirements and Calibration Strategy

In practice, the positional accuracy of a maser feature measured with VLBI is approximately given by the synthesized beam size divided by twice the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). For a typical beam size of 0.3–0.5 mas at 22 GHz, reaching positional accuracies of a few tens of microarcseconds for a single maser feature requires SNRs of at least ∼10. These stringent requirements necessitate observations that combine high sensitivity, stable phase referencing, and precise absolute astrometry.

Standard phase-referenced VLBI observations alternate between the maser target and a nearby calibrator—usually within ≲1∘, e.g., Ref. [27]—whose absolute position is known to sub-milliarcsecond accuracy. This method provides a direct tie to the celestial reference frame and enables absolute astrometry across multiple epochs. However, such frequent source switching introduces substantial observational inefficiency: each telescope in the array spends a large fraction of time slewing and reacquiring fringes instead of integrating on the target. For weak sources, this loss of on-source time can significantly reduce overall sensitivity.

To mitigate this limitation, the MCP developed an observational strategy that leverages self-calibration whenever possible, e.g., Refs. [31,35,37]. In this mode, one or several strong maser lines—typically with flux densities ≳ 100 mJy—serve as internal phase references. The derived phase solutions are then applied to all other spectral channels, effectively removing the need for rapid switching to an external calibrator and maximizing on-source integration time. This approach provides relative astrometry of maser features with sub-beam precision, sufficient for deriving accurate disk kinematics and black hole masses.

Before self-calibration can be applied, two prerequisites must be met as follows:

- Strong maser components: At least one or a few maser lines must be bright enough (e.g., flux density ≳ 80–100 mJy for a single line feature) to yield robust self-calibration solutions within typical coherence times (a few minutes at 22 GHz).

- Accurate absolute position: The absolute position of the maser reference feature must be known to within a few milliarcseconds to minimize the multiband delay due to source position uncertainty, e.g., Ref. [26] that would introduce frequency-dependent position offsets between maser spots in a disk. Such positional information is usually obtained from prior interferometric observations, for example, using the Very Large Array (VLA) in its most extended configuration.

When both conditions are satisfied, self-calibration allows the majority of observing time to be spent on the maser target, improving observing efficiency by a factor of ∼4 relative to standard phase-referencing observations. This methodology has been adopted in many successful MCP experiments, e.g., Refs. [27,28,31] and has proven critical for mapping faint, distant disk masers.

4.2. Array Sensitivity and Telescope Participation

High-quality maser imaging also depends critically on the sensitivity of the VLBI array. While the Very Long Baseline Array (VLBA) provides excellent baseline coverage and angular resolution, its sensitivity alone is generally insufficient to detect extragalactic masers at the required SNR. For most systems, inclusion of one or more large, highly sensitive antennas—such as the 100 m Green Bank Telescope (GBT), the phased Very Large Array (VLA), or the Effelsberg 100 m telescope—is essential. These instruments contribute the majority of the correlated flux on the longest baselines, enabling detections of maser features as weak as a few millijanskys, dramatically increasing the array’s fringe sensitivity and thus the precision of the measured maser positions.

4.3. Considerations and Observational Workflow

A typical MCP VLBI observation proceeds as follows:

- Pre-observation preparation: The maser position is first refined with connected-element interferometers (e.g., the VLA) to within a few milliarcseconds.

- Observation configuration: If strong maser features are available, the observation is performed in self-calibration mode to maximize sensitivity. Otherwise, the schedule alternates between the maser target and a nearby calibrator for phase referencing. The observing band was divided into four 16 MHz spectral windows to cover all maser velocity components. Delay calibrators were observed approximately once or twice per two hours to determine and correct instrumental delays.

- Data correlation and calibration: Correlation is carried out at high spectral resolution (∼25 kHz, corresponding to ≈0.3 km s−1) using the DiFX correlator. Subsequent calibration includes a priori amplitude correction, bandpass calibration, and fringe fitting (either on calibrators or strong maser lines).

- Imaging and modeling: The final data cubes are CLEANed to produce spatial–velocity maps of maser spots. The measured positions and Doppler velocities are then fitted with warped, thin-disk models to yield SMBH masses and, when accelerations are available, geometric distances.

This observing framework—combining precise absolute astrometry, strong sensitivity, and careful calibration—has enabled the MCP to measure SMBH masses with uncertainties as small as a few percent in several nearby galaxies. The same principles underpin all successful extragalactic maser VLBI programs and will continue to guide future campaigns with next-generation instruments.

5. Maser Disk Modeling and Key Results of Maser-Based MBH Measurements

5.1. Maser Disk Modeling

VLBI imaging of H2O megamasers provides spatially resolved positions and line-of-sight velocities of individual maser spots, which together trace the kinematics of the molecular gas orbiting the central black hole. Modeling these data allows a direct measurement of the black hole mass (MBH) and, in some cases, the geometric distance to the host galaxy. Two general approaches are commonly employed for BH mass measurement: (1) fitting a Keplerian rotation curve to the high-velocity masers, and (2) performing a full three-dimensional thin-disk model fit to all detected maser features.

5.1.1. Rotation-Curve Fitting

The most straightforward approach is to fit a theoretical Keplerian rotation curve to the observed distribution of high-velocity masers, e.g., Refs. [27,28,73]. In this method, one assumes that all high-velocity maser spots lie at the mid-line of the maser disk, and VLBI map of the maser disk is first rotated so that the disk plane aligns with the x-axis. Furthermore, the position of the black hole is assumed to be at the point along the slightly warped disk plane whose x-position matches the average x-position of the systemic masers, see details in [27]. The impact parameter r of each maser spot—its projected distance from the black hole to the maser splot—is then computed. The observed line-of-sight velocity Vobs (corrected for disk inclination) of each maser feature can be expressed as a combination of the systemic velocity of the galaxy (Vsys) and the rotational velocity Vrot of the disk at the corresponding impact parameter r:

where G is the gravitational constant and sin(i) is the correction term for disk inclination. Because the reported systemic velocity of a galaxy often carries substantial uncertainty, Vsys is typically treated as a free parameter see Equations (7) and (8) in [27] when fitting a Keplerian rotation curve to the redshifted and blueshifted maser spots in a maser disk, which have positive and negative velocity offset from Vsys, respectively (see Figure 2).

When constructing the rotation curve, both special and general relativistic corrections [27,28] must be applied to the measured velocities, as the maser spots orbit at speeds of several hundred to nearly 1000 km s−1. For such velocities, relativistic effects can introduce shifts on the order of a few km s−1—non-negligible when deriving MBH to percent-level accuracy. After applying these corrections, a least-squares or Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) fit to the Keplerian rotation curve yields a robust estimate of the black hole mass with accuracy of around a few percents. This approach provides a quick, model-independent assessment of MBH and serves as an important preliminary check before proceeding to more sophisticated modeling.

5.1.2. Three-Dimensional Disk Modeling

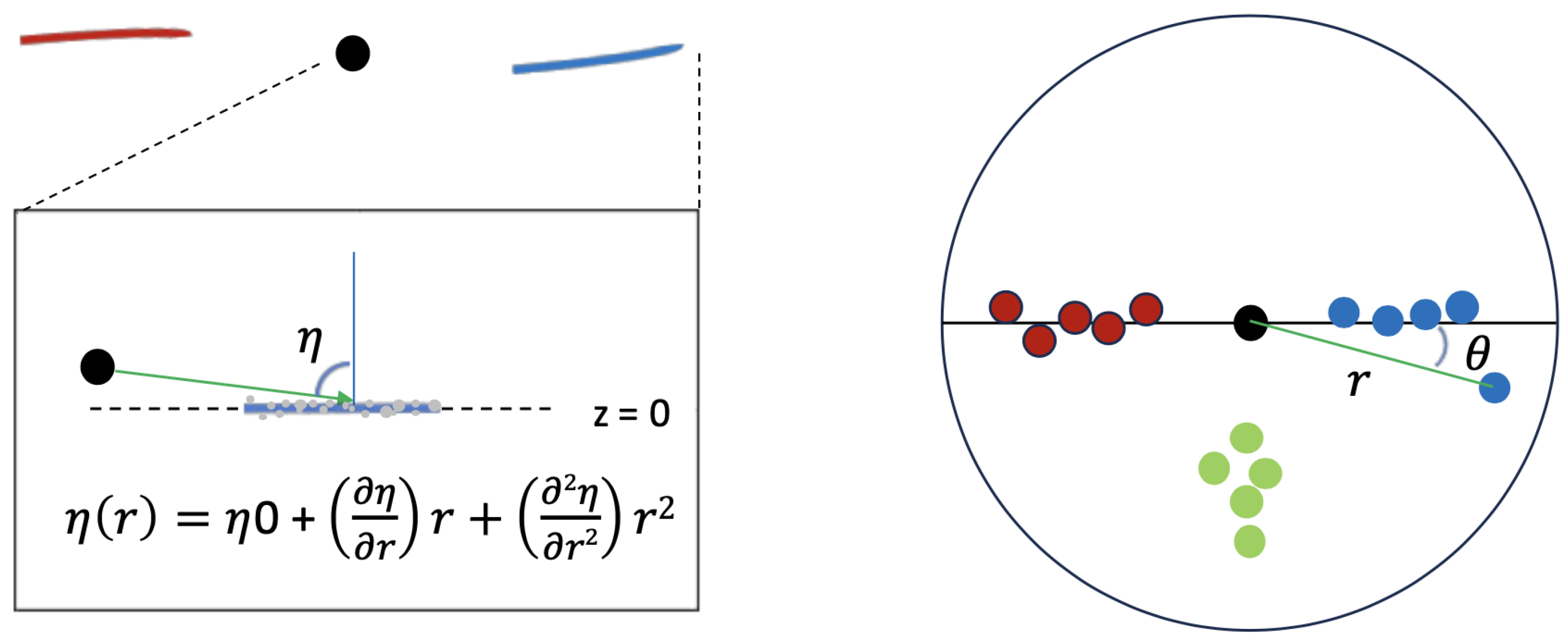

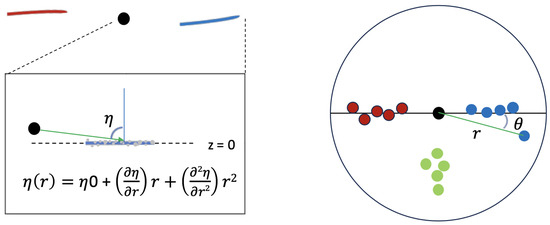

A more comprehensive approach for BH mass measurement with H2O megamasers involves global three-dimensional modeling of the maser disk structure and kinematics, e.g., Refs. [31,35,36]. Generally speaking, this type of modeling can be performed reliably only for a disk maser system in which all three groups of maser features (i.e., blueshifted, systemic, and redshifted masers) are present. In particular, the systemic masers with their acceleration measurements available are usually required for constraining the disk inclination and the inclination warp precisely. In this method, all maser features—both high-velocity and systemic—with position uncertainties under a certain threshold will be used in the modeling. In addition, all these features are fitted simultaneously using a thin, warped disk model that accounts for the geometry, inclination, and orientation of the disk in space. The model typically contains 15 global parameters, including the eastward (x0) and northward (y0) position of a black hole, the black hole mass (MBH), Hubble constant (H0), recession velocity (V0), peculiar velocity with respect to Hubble flow in cosmic microwave background frame (Vp), and parameters describing the radial warp and inclination variations of the disk plane as well as orbital eccentricity. In the three-dimensional disk model, each maser spot can reside at any location within the thin disk plane, with its coordinates described by its radius r and azimuthal angle θ with respect to the mid-line of the disk (see an illustration of the model in Figure 5). The warp of the disk is prescribed by both the position angle η(r) and the inclination angle i(r) of each orbit of radius r, with η(r) and i(r) evaluated using the following equations:

Figure 5.

The left panel shows the representative morphology of a nearly edge-on, warped maser disk conceived in the three-dimensional disk modeling, which usually prescribes the inclination warp i(r) and the position angle warp η(r) as low-order polynomials (see the representative equation in the inset of the figure). The right panel shows the overhead view of a model maser disk, in which a maser spot can reside at any location of the disk, with its position described by polar coordinates (r, θ). The red, green, and blue dots/curves in the plots represent the redshifted, systemic, and blueshifted masers, respectively.

When constraining the model with the data, all global parameters and each internal parameter (r, θ) for each maser spot are adjusted using the MCMC procedure. During the modeling, each maser spot contributes constraints on position, velocity, and (when monitored over time) acceleration, enabling a self-consistent reconstruction of the three-dimensional structure of the disk. The typical output from the MCMC modeling provides the posterior probability distribution for each global parameter, allowing one to estimate the median value and uncertainty of the parameter (see Table 1 for an example).

Table 1.

Best-fitting disk model parameters for NGC 6264 (adapted from Table 6 of Kuo et al. [31]).

This method represents the most robust and least assumption-dependent means of determining MBH with a H2O maser disk. Unlike the rotation-curve fit, which relies on the assumption that the redshifted and blueshifted masers lie exactly at the midline of the disk, the full disk model relaxes this assumption by allowing the maser spots to be located at any place in the disk when fitting the global geometric configuration of the system. By incorporating the accelerations of systemic masers, the model can also yield an independent geometric distance to the galaxy—a cornerstone of the Megamaser Cosmology Project’s measurement of the Hubble constant [31,35,36,38].

The three-dimensional modeling is typically implemented through Bayesian parameter estimation using MCMC techniques, allowing rigorous propagation of measurement uncertainties and parameter covariances. The final best-fit parameters provide not only the black hole mass but also detailed information about the disk’s warp structure, inclination gradient, and systemic velocity. In well-sampled systems such as NGC 4258 [74], UGC 3789 [35], and NGC 5765b [37], this approach achieves black hole mass uncertainties below ≈2–10% (considering the uncertainty in distance) and distance measurements with similar precision, firmly establishing the reliability of maser-based techniques for precision black hole and cosmological studies.

5.2. The Maser-Based MBH Measurements

As described in the previous subsection, there are two principal approaches for deriving black hole masses from VLBI maser observations: (1) fitting a Keplerian rotation curve to the high-velocity maser components, and (2) performing a comprehensive three-dimensional disk modeling of the entire maser distribution. However, in practice, not all maser systems are suitable for both methods. The choice of modeling approach depends critically on the quality of the VLBI imaging data.

In the MCP, the most accurate black hole mass measurements have been obtained from the highest-quality disk maser systems—those with high-sensitivity VLBI maps that yield precise position measurements for both systemic and high-velocity maser components. These “gold-standard” systems allow for both detailed 3D disk modeling and geometric distance determination, e.g., NGC 5765b; see [37]. In such cases, both the rotation-curve fitting and full disk modeling approaches yield consistent black hole masses within their respective uncertainties, providing a robust validation of the modeling framework. Table 2 illustrates this agreement by comparing MBH values for the five disk systems for which both methods are available from the literature, demonstrating the internal consistency of the maser-based techniques.

Table 2.

Comparison of BH masses derived from rotation curve fitting and disk modeling.

However, not all detected maser systems exhibit such ideal observational conditions. In a number of galaxies observed by the MCP and other groups, the VLBI imaging sensitivity is insufficient for robust 3D disk modeling. Low signal-to-noise ratios in individual maser components lead to large position uncertainties, which limit the precision with which the disk geometry can be reconstructed. In other cases—such as systems where only the high-velocity maser components are detected (e.g., Circinus)—the absence of systemic masers precludes reliable modeling of the full 3D structure. For these systems, only the rotation-curve fitting method can be applied to estimate the black hole mass, e.g., ESO558-G009; see [28].

Even though the position uncertainties in these lower-quality systems are larger, the black hole masses derived from rotation-curve fitting remain remarkably reliable. The uncertainties of these black mass measurements remain at ∼10%. Consequently, these measurements remain valuable for populating the low-mass end of the MBH–σ∗ relation and for exploring black hole–galaxy coevolution in late-type systems.

A comprehensive summary of all known maser-based black hole mass measurements is presented in Table 3, adapted from Table 5 of Kuo et al. [73]. As one can see, nearly all of the accurately measured maser-based black hole masses cluster around . This concentration likely reflects the underlying black hole mass function of Type II AGNs and Seyfert 2 galaxies, which dominates the parent population of maser hosts [73]. The narrow distribution in MBH may therefore result from both intrinsic demographics and the selection biases favoring obscured active galaxies with nearly edge-on circumnuclear gas disks.

Table 3.

Summary of known maser-based black hole masses (adapted from Table 5 in [73]).

In addition, one can also see from Table 3 that the Eddington ratios of these accreting black holes are typically found to be λEdd∼0.01 for well-ordered, triple-peaked maser disks. As discussed in Section 4 of Kuo et al. [73], such relatively low, but moderate accretion rates are likely a natural consequence of the conditions required for masing: warm, dense molecular gas exposed to moderate AGN radiation fields. Systems accreting at much lower or higher Eddington ratios may lack the stable, molecular disk environments at subparsec scales necessary for sustaining maser emission.

The growing sample of maser-based black hole masses, though modest in number, now provides a unique and homogeneous dataset for investigating the scaling relations of active galaxies. Their accuracy, achieved through purely dynamical and geometric means, establishes maser disks as one of the most reliable tools for precision SMBH mass measurements in the nearby Universe.

5.3. Error Budget

Uncertainties in maser-based black hole mass (MBH) measurements can be broadly categorized into two classes: measurement errors and systematic errors. The former are primarily observational in nature, while the latter arise from deviations from the underlying assumptions of the disk model.

The dominant contribution of measurement errors arises from the adopted galaxy distance. Because MBH scales linearly with distance (MBH ∝ D), even a modest fractional uncertainty in D translates directly into the same fractional uncertainty in MBH. The secondary source of measurement uncertainty originates from the positional errors of individual maser spots in VLBI observations. Since the inferred rotation curve depends directly on the relative positions of the maser components, any uncertainty in the position measurements of the maser spots propagates into the derived orbital radii and hence the estimated MBH. The positional accuracy of each maser spot is approximately given by the synthesized beam size divided by twice the signal-to-noise ratio, emphasizing the need for high sensitivity and robust calibration.

Systematic errors are more subtle and arise from departures from the simplifying assumptions of the maser disk model. As discussed in Section 4 of Kuo et al. [75], the fundamental assumptions are

- The masing gas follows circular orbits around the central black hole.

- The disk dynamics are dominated by the gravitational potential of the black hole, such that the contribution of the disk’s self-gravity is negligible and the rotation curve is purely Keplerian.

- The motion of the maser gas is not significantly affected by non-gravitational forces such as radiation pressure, e.g., Ref. [76] or shocks associated with spiral density waves in the gas disk, e.g., Refs. [52,53].

Deviations from any of these assumptions can introduce biases in the inferred MBH. For instance, if the maser orbits exhibit ellipticity or significant eccentric motion, the assumption of circular rotation would lead to overestimation or underestimation of the central mass depending on the orbital phase coverage. Similarly, in systems where the disk mass or self-gravity is non-negligible—such as in extremely gas-rich circumnuclear environments—the measured rotation curve may deviate slightly from the v ∝ r−1/2 law expected for a purely Keplerian disk, e.g., Refs. [43,75,77,78]. As a result, the best-fit MBH assuming purely Keplerian motion would be biased higher than when accounting for the disk mass interior to the maser region.

Non-gravitational effects can also perturb the maser kinematics. Radiation pressure from the AGN continuum may alter the velocity field if the incident flux approaches or exceeds the Eddington limit for molecular gas, while shocks from spiral density waves could locally disturb the orbital motions, resulting in deviations from pure Keplerian rotation. Although such effects are expected to be minor for the majority of well-ordered, triple-peaked maser disks, e.g., Ref. [53], they represent the primary sources of systematic uncertainty beyond observational errors.

In summary, for the high-quality megamaser disks with well-resolved VLBI maps and accurately known distances, the total uncertainty in MBH is typically at the level of ∼5–10%, dominated by measurement errors. For lower-quality systems, or for those where disk self-gravity or non-circular motions cannot be ruled out, the systematic uncertainties may be larger, reaching up to ∼20%. Continued refinement of disk modeling, coupled with improved sensitivity and astrometric precision, will further minimize these uncertainties in future analyses.

6. Implications of Maser-Based MBH Measurements for SMBH Demographics

Over the past three decades, there has been remarkable progress in detecting supermassive black holes (SMBHs) and constraining their masses in galactic nuclei (see reviews by [10]). This rapid advancement has been largely driven by the advent of high angular resolution imaging with the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) and by the development of sophisticated dynamical modeling techniques. As a result, the number of SMBH detections has grown to the point that the field has shifted from establishing the existence of black holes to studying their demographics, particularly the correlations between black hole mass and the large-scale properties of their host galaxies.

One of the most fundamental empirical relations uncovered is the tight correlation between black hole mass (MBH) and the effective stellar velocity dispersion (σ∗) of galactic bulges, known as the MBH–σ∗ relation e.g., Refs. [5,6,10,79,80]. This relation implies that SMBHs are ubiquitous components of bulge-dominated galaxies and that their growth is intimately linked with the formation and evolution of their host galaxies. Although the correlation appears tight in the current sample, it remains essential to examine its validity critically using black hole masses obtained with the most accurate and least model-dependent methods available.

For the purpose of examining the MBH–σ∗ relation, the H2O megamaser technique offers an unique, geometric method of measuring accurate black hole masses. Although applicable only to galaxies that host detectable water maser emission, it yields exceptionally accurate results at the low-mass end of the MBH–σ∗ relation (MBH∼106– with percentage-level accuracy). Part of the extraordinary accuracy of maser-based MBH stems from the fact that VLBI observations achieve angular resolutions two orders of magnitude higher than the best optical facilities, corresponding to tens of microarcseconds at 22 GHz. For galaxies with approximately constant central stellar densities, the black hole’s sphere of influence scales as [27], where Rinf is the radius of the gravitational sphere of influence of BH. Thus, a factor of 100 improvement in angular resolution allows the measurement of black hole masses up to 106 times smaller, or equivalently, permits ruling out extremely dense stellar clusters as alternative explanations for the central mass concentration, e.g., Ref. [27]. Beyond the gain in angular resolution, maser disks also offer significant dynamical simplicity. Systems such as NGC 4258 display Keplerian rotation curves accurate to within 1%, ensuring that MBH can be measured with minimal modeling assumptions. The maser disks are typically compact (e.g., r ≈ 0.2 pc in NGC 4258), well within the gravitational sphere of influence of their SMBHs (rinf ≈ 1 pc), guaranteeing that the rotation is dominated by the central mass. These features make maser-based measurements among the most precise and direct determinations of SMBH mass in the nearby Universe.

The key demographic insight emerging from megamaser samples is that their black hole masses do not always lie exactly on the MBH–σ∗ relation defined by massive, early-type galaxies. In Greene et al. [40], the authors analyze a sample of megamaser disk galaxies with very precise MBH measurements and compare them to the scaling relations. They find that while the maser-based black hole masses span a range of 106 to 108M⊙, their host galaxy properties (total stellar mass, central mass density, velocity dispersion σ∗, etc.) occupy a relatively narrow range. At a fixed σ∗, the mean maser MBH is offset downward by about −0.6 dex relative to the relation defined by early-type galaxies. In other words, maser-host SMBHs tend to be undermassive for their bulge velocity dispersion compared to the canonical relation. This result suggests that the MBH–σ∗ correlation may not be entirely universal across galaxy types. In particular, late-type spirals and disk galaxies (the typical hosts of megamasers) may harbor SMBHs that grow less efficiently or follow different evolutionary trajectories than those in classical bulges.

Because megamaser-based MBH measurements are both precise and largely free from the systematics that affect stellar- or gas-based methods, they are well suited to probe possible secondary dependencies, scatter, or bifurcations in the MBH–σ∗ relation. For example, the offset observed by Greene et al. [40] may reflect differences in feedback, accretion histories, or morphological evolution in disk galaxies versus ellipticals. Furthermore, the maser sample is clustered around ∼107M⊙ and triple-peaked maser systems exhibit characteristically moderate Eddington ratios, with a median λEdd ≈ 0.04, e.g., Ref. [73]. These characteristics might not be purely selection effects but could reflect the physical regimes where maser emission is viable: moderate accretion rates, stable molecular disks, and moderate AGN radiation fields. Thus, the maser technique may preferentially sample a specific subpopulation of SMBHs, whose demographic properties are especially relevant for understanding black hole feeding and growth in late-type systems.

In summary, maser-based black hole masses anchor the low-mass end of the SMBH mass function with unmatched precision, and their systematic offsets from canonical scaling relations challenge the assumption that those relations apply universally. As the sample of megamaser disks grows, these measurements will be critical for refining models of SMBH–galaxy coevolution across mass, morphology, and accretion regimes.

7. Future Prospects

Although the number of galaxies with detected H2O megamaser emission remains modest, the outlook for expanding the maser sample—and thus increasing the number of galaxies with dynamical black hole mass measurements—is highly promising. Over the past two decades, systematic surveys such as the MCP have demonstrated that ∼3% of narrow-emission-line active galactic nuclei (AGNs) host detectable megamasers. Extrapolating this detection rate to the growing catalogs of Type II AGNs suggests substantial room for future discoveries.

7.1. Prospects at Low Redshift

As discussed in Kuo et al. [70], new spectroscopic compilations have greatly expanded the pool of potential maser-host candidates. The recent identification of over ∼6000 previously unobserved Type II AGNs from the 2MASS Redshift Survey (2MRS) [81], at redshifts z < 0.09, represents a particularly rich reservoir for future maser searches. None of these sources have yet been surveyed for 22 GHz water maser emission. Assuming a conservative detection rate of ∼3%—consistent with previous large-scale maser surveys—one can expect the discovery of ≳180 new H2O megamaser systems from this population alone.

Moreover, the ongoing Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI) survey, e.g., Ref. [82] is expected to uncover thousands of additional Type II AGNs across a broad redshift range. Many of these AGNs will fall within the sensitivity limits of current 22 GHz facilities such as the Green Bank Telescope (GBT) and the Effelsberg 100 m Telescope, ensuring continued opportunities for targeted maser searches. The combined yield from these upcoming samples could increase the number of known maser galaxies by a factor of two or more over the next decade.

Expanding the nearby maser sample has direct implications for black hole demographics: a larger number of dynamical MBH measurements will significantly strengthen the statistical foundation for testing the universality of the MBH–σ∗ relation, calibrating secondary mass estimators, and refining the low-mass end of the SMBH mass function.

To efficiently identify new maser targets and enable VLBI imaging for maser disks at greater distances (e.g., z ≳ 0.05), a substantial enhancement in sensitivity is essential. This requirement is expected to be met by the next-generation Very Large Array (ngVLA), which will deliver an order-of-magnitude improvement in sensitivity. The ngVLA will not only facilitate efficient maser detections over a volume ∼30 times larger than current searches, but will also enable accurate geometric distance measurements for fainter disk masers. As a result, a ∼1% determination of H0 via the maser technique may become feasible in the future [83].

7.2. Prospects at High Redshift

Beyond the local Universe, the possibility of detecting water maser emission from high-redshift galaxies opens an exciting frontier for black hole mass measurements. As discussed in Kuo et al. [30], submillimeter water transitions—such as the 380 GHz (423–330) line—provide a promising probe of dense, warm molecular gas in luminous infrared galaxies and quasars at z∼1–4. In several gravitationally lensed ultraluminous infrared galaxies (ULIRGs), these transitions have already been detected with ALMA (Kuo et al. in prep.), demonstrating that high-z water masers can indeed be observable under favorable conditions.

Future advances in submillimeter VLBI may open the possibility of spatially resolving megamaser disks at cosmological distances. In particular, if sufficiently bright and compact maser spots are detected in strongly lensed or intrinsically luminous sources (e.g., quasars) at z > 1, the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) or its future extensions could, in principle, reach angular resolutions comparable to those currently achieved for nearby systems such as NGC 4258.

For example, it has been shown that the BH mass function of luminous quasars at 1.5 ≲ z ≲ 3 peaks at [84]. If an H2O maser disk were present around a ∼109M⊙ SMBH at z∼2, modeling of maser disk physics indicates that its angular diameter could be on the order of ∼1–3 milliarcseconds [30], comparable to the typical size of nearby maser disks, e.g., Ref. [27]. At submillimeter wavelengths, the EHT can deliver angular resolutions of ∼20 μas; thus, for high-redshift maser detections with signal-to-noise ratios of ∼10, the astrometric precision for individual maser spots would be a few microarcseconds. This level of accuracy would be comparable to that achieved for NGC 4258 using 22 GHz VLBI [26], raising the exciting possibility that direct mapping of maser disks and precise dynamical MBH measurements could be achieved even at high redshift in the future.

Such capabilities would mark a major leap forward in observational cosmology. Dynamical black hole masses at z ≳ 1 are extremely rare and typically inferred from indirect or model-dependent methods such as virial estimators. The detection and imaging of submillimeter masers at high redshift would provide a uniquely direct and geometric approach to measuring MBH in the early Universe, opening a new window on black hole–galaxy coevolution across cosmic time.

7.3. Summary of Outlook

In summary, future progress in H2O megamaser surveys and high-frequency VLBI will transform maser-based black hole mass measurements from a niche technique into a statistically powerful probe of SMBH demographics. Large-scale, multi-wavelength AGN catalogs from 2MRS, DESI, and forthcoming surveys (e.g., LSST and SPHEREx) will dramatically increase the number of viable maser targets at low redshift, while new observing capabilities at millimeter and submillimeter wavelengths will extend the reach of the technique to the distant Universe. Combined, these developments will enable maser observations to address some of the most fundamental questions in black hole astrophysics: How do SMBHs grow across cosmic time? Do the scaling relations that govern nearby galaxies hold at high redshift? Also, to what extent are black holes and their host galaxies coevolving?

The coming decade thus holds enormous promise for expanding both the scope and impact of maser-based black hole studies—from precise, geometric MBH determinations in nearby Seyferts to pioneering dynamical measurements of the earliest supermassive black holes.

8. Conclusions

Water megamasers have emerged as one of the most powerful and direct probes of supermassive black hole (SMBH) masses in galactic nuclei. By tracing molecular gas in sub-parsec, nearly edge-on disks, VLBI observations of H2O masers deliver purely geometric and dynamical mass measurements that are essentially free from the modeling degeneracies affecting stellar- or gas-dynamical methods. Over the past two decades, systematic surveys and follow-up imaging by the Megamaser Cosmology Project have transformed this technique from a single-object proof of concept to a statistically meaningful tool for exploring SMBH demographics.

The accuracy and reliability of maser-based MBH determinations arise from high-quality VLBI data and careful modeling of disk geometry and kinematics. For the best-studied systems, such as NGC 4258, UGC 3789, and NGC 5765b, both rotation-curve fitting and full three-dimensional disk modeling yield consistent black hole masses with total uncertainties at the 5–10% level. Even in systems where only partial velocity coverage or lower-quality imaging is available, the derived black hole masses remain robust enough to inform studies of the MBH–σ∗ relation and the low-mass end of the black hole mass function.

Current results reveal that maser-host SMBHs—predominantly in late-type galaxies with Type II AGNs—cluster around MBH∼107M⊙ and exhibit moderate, characteristic Eddington ratios of λEdd∼0.01. Their systematic offset below the canonical MBH–σ∗ relation defined by early-type galaxies suggests that the scaling relations governing SMBH–galaxy coevolution are not strictly universal but depend on host morphology and accretion state. Because maser-based masses are free from the major systematics of indirect techniques, they provide an essential anchor for refining these demographic relations.

Looking forward, the prospects for expanding the maser sample are excellent. With the identification of thousands of new Type II AGNs in the 2MRS and DESI catalogs, and the demonstrated ∼3% detection rate of 22 GHz masers, hundreds of additional disk masers may yet be found in the nearby Universe. At the same time, the emerging detection of submillimeter water masers in high-redshift galaxies, combined with next-generation millimeter and submillimeter VLBI arrays such as the Event Horizon Telescope, opens the possibility of direct dynamical black hole mass measurements at cosmological distances. Together, these advances will elevate maser-based techniques from a specialized niche to a cornerstone method in the study of SMBH growth and galaxy evolution across cosmic time.

Funding

This research is supported by National Science and Technology Council, R.O.C under the project 113-2112-M-110 -013-.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This research has made use of NASA’s Astrophysics Data System (ADS) Bibliographic Services, and the NASA/IPAC Extragalactic Database (NED) which is operated by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, under contract with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. In addition, this work also makes use of the cosmological calculator described in Wright [85]. During the preparation of this manuscript, the author used ChatGPT-5.1 for the purposes of correcting for English errors and polishing the texts. In addition, the author also used this generative AI system to summarize the key points of the most relevant reference papers for this review in order to present the most essential discussions in this work and save time for the preparation of the manuscript. The authors have reviewed and edited the output significantly and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Note

| 1 | RM-based virial black hole mass estimates have traditionally and most reliably applied to type 1 AGNs, because only in those cases are the canonical broad emission lines accessible. |

References

- Young, P.J.; Westphal, J.A.; Kristian, J.; Wilson, C.P.; Landauer, F.P. Evidence for a supermassive object in the nucleus of the galaxy M87 from SIT and CCD area photometry. Astrophys. J. 1978, 221, 721–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargent, W.L.W.; Young, P.J.; Boksenberg, A.; Shortridge, K.; Lynds, C.R.; Hartwick, F.D.A. Dynamical evidence for a central mass concentration in the galaxy M87. Astrophys. J. 1978, 221, 731–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonry, J.L. Evidence for a central mass concentration in M 32. Astrophys. J. Lett. 1984, 283, L27–L30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Marel, R.P.; Cretton, N.; de Zeeuw, P.T.; Rix, H.W. Improved Evidence for a Black Hole in M32 from HST/FOS Spectra. II. Axisymmetric Dynamical Models. Astrophys. J. 1998, 493, 613–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magorrian, J.; Tremaine, S.; Richstone, D.; Bender, R.; Bower, G.; Dressler, A.; Faber, S.M.; Gebhardt, K.; Green, R.; Grillmair, C.; et al. The Demography of Massive Dark Objects in Galaxy Centers. Astron. J. 1998, 115, 2285–2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebhardt, K.; Bender, R.; Bower, G.; Dressler, A.; Faber, S.M.; Filippenko, A.V.; Green, R.; Grillmair, C.; Ho, L.C.; Kormendy, J.; et al. A Relationship between Nuclear Black Hole Mass and Galaxy Velocity Dispersion. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2000, 539, L13–L16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, A.J.; Sarzi, M.; Rix, H.W.; Ho, L.C.; Filippenko, A.V.; Sargent, W.L.W. Evidence for a Supermassive Black Hole in the S0 Galaxy NGC 3245. Astrophys. J. 2001, 555, 685–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarzi, M.; Rix, H.W.; Shields, J.C.; Rudnick, G.; Ho, L.C.; McIntosh, D.H.; Filippenko, A.V.; Sargent, W.L.W. Supermassive Black Holes in Bulges. Astrophys. J. 2001, 550, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siopis, C.; Gebhardt, K.; Lauer, T.R.; Kormendy, J.; Pinkney, J.; Richstone, D.; Faber, S.M.; Tremaine, S.; Aller, M.C.; Bender, R.; et al. A Stellar Dynamical Measurement of the Black Hole Mass in the Maser Galaxy NGC 4258. Astrophys. J. 2009, 693, 946–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kormendy, J.; Ho, L.C. Coevolution (Or Not) of Supermassive Black Holes and Host Galaxies. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 2013, 51, 511–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, C.A.; Bentz, M.C.; Vasiliev, E.; Valluri, M.; Onken, C.A. The Black Hole Mass of NGC 4151 from Stellar Dynamical Modeling. Astrophys. J. 2021, 916, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Bureau, M.; Ruffa, I.; Davis, T.A.; Dominiak, P.; Elford, J.S.; Lelli, F.; Williams, T.G. WISDOM Project–XXV. Improving the CO-dynamical supermassive black hole mass measurement in the galaxy NGC 1574 using high spatial resolution ALMA observations. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2025, 541, 2540–2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blandford, R.D.; McKee, C.F. Reverberation mapping of the emission line regions of Seyfert galaxies and quasars. Astrophys. J. 1982, 255, 419–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, B.M.; Ferrarese, L.; Gilbert, K.M.; Kaspi, S.; Malkan, M.A.; Maoz, D.; Merritt, D.; Netzer, H.; Onken, C.A.; Pogge, R.W.; et al. Central Masses and Broad-Line Region Sizes of Active Galactic Nuclei. II. A Homogeneous Analysis of a Large Reverberation-Mapping Database. Astrophys. J. 2004, 613, 682–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentz, M.C.; Denney, K.D.; Grier, C.J.; Barth, A.J.; Peterson, B.M.; Vestergaard, M.; Bennert, V.N.; Canalizo, G.; De Rosa, G.; Filippenko, A.V.; et al. The Low-luminosity End of the Radius-Luminosity Relationship for Active Galactic Nuclei. Astrophys. J. 2013, 767, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentz, M.C.; Katz, S. The AGN Black Hole Mass Database. Publ. Astron. Soc. Pac. 2015, 127, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cretton, N.; van den Bosch, F.C. Evidence for a Massive Black Hole in the S0 Galaxy NGC 4342. Astrophys. J. 1999, 514, 704–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thater, S.; Lyubenova, M.; Fahrion, K.; Martín-Navarro, I.; Jethwa, P.; Nguyen, D.D.; van de Ven, G. Effect of the initial mass function on the dynamical SMBH mass estimate in the nucleated early-type galaxy FCC 47. Astron. Astrophys. 2023, 675, A18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neureiter, B.; de Nicola, S.; Thomas, J.; Saglia, R.; Bender, R.; Rantala, A. Accuracy and precision of triaxial orbit models I: SMBH mass, stellar mass, and dark-matter halo. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2023, 519, 2004–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, J.L.; Barth, A.J.; Ho, L.C.; Sarzi, M. The M87 Black Hole Mass from Gas-dynamical Models of Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph Observations. Astrophys. J. 2013, 770, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, T.A.; Bureau, M.; Cappellari, M.; Sarzi, M.; Blitz, L. A black-hole mass measurement from molecular gas kinematics in NGC4526. Nature 2013, 494, 328–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, T.A.; Bureau, M.; Onishi, K.; Cappellari, M.; Iguchi, S.; Sarzi, M. WISDOM Project - II. Molecular gas measurement of the supermassive black hole mass in NGC 4697. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2017, 468, 4675–4690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, A.J.; Darling, J.; Baker, A.J.; Boizelle, B.D.; Buote, D.A.; Ho, L.C.; Walsh, J.L. Toward Precision Black Hole Masses with ALMA: NGC 1332 as a Case Study in Molecular Disk Dynamics. Astrophys. J. 2016, 823, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boizelle, B.D.; Barth, A.J.; Walsh, J.L.; Buote, D.A.; Baker, A.J.; Darling, J.; Ho, L.C. A Precision Measurement of the Mass of the Black Hole in NGC 3258 from High-resolution ALMA Observations of Its Circumnuclear Disk. Astrophys. J. 2019, 881, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrnstein, J.R.; Moran, J.M.; Greenhill, L.J.; Diamond, P.J.; Inoue, M.; Nakai, N.; Miyoshi, M.; Henkel, C.; Riess, A. A geometric distance to the galaxy NGC4258 from orbital motions in a nuclear gas disk. Nature 1999, 400, 539–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argon, A.L.; Greenhill, L.J.; Reid, M.J.; Moran, J.M.; Humphreys, E.M.L. Toward a New Geometric Distance to the Active Galaxy NGC 4258. I. VLBI Monitoring of Water Maser Emission. Astrophys. J. 2007, 659, 1040–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, C.Y.; Braatz, J.A.; Condon, J.J.; Impellizzeri, C.M.V.; Lo, K.Y.; Zaw, I.; Schenker, M.; Henkel, C.; Reid, M.J.; Greene, J.E. The Megamaser Cosmology Project. III. Accurate Masses of Seven Supermassive Black Holes in Active Galaxies with Circumnuclear Megamaser Disks. Astrophys. J. 2011, 727, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Braatz, J.A.; Reid, M.J.; Condon, J.J.; Greene, J.E.; Henkel, C.; Impellizzeri, C.M.V.; Lo, K.Y.; Kuo, C.Y.; Pesce, D.W.; et al. The Megamaser Cosmology Project. IX. Black Hole Masses for Three Maser Galaxies. Astrophys. J. 2017, 834, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masini, A.; Comastri, A.; Baloković, M.; Zaw, I.; Puccetti, S.; Ballantyne, D.R.; Bauer, F.E.; Boggs, S.E.; Brandt, W.N.; Brightman, M.; et al. NuSTAR observations of water megamaser AGN. Astron. Astrophys. 2016, 589, A59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, C.Y.; Gao, F.; Braatz, J.A.; Pesce, D.W.; Humphreys, E.M.L.; Reid, M.J.; Impellizzeri, C.M.V.; Henkel, C.; Wagner, J.; Wu, C.E. What determines the boundaries of H2O maser emission in an X-ray illuminated gas disc? Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2024, 532, 3020–3035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, C.Y.; Braatz, J.A.; Reid, M.J.; Lo, K.Y.; Condon, J.J.; Impellizzeri, C.M.V.; Henkel, C. The Megamaser Cosmology Project. V. An Angular-diameter Distance to NGC 6264 at 140 Mpc. Astrophys. J. 2013, 767, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebhardt, K.; Thomas, J. The Black Hole Mass, Stellar Mass-to-Light Ratio, and Dark Halo in M87. Astrophys. J. 2009, 700, 1690–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, M.J.; Braatz, J.A.; Condon, J.J.; Greenhill, L.J.; Henkel, C.; Lo, K.Y. The Megamaser Cosmology Project. I. Very Long Baseline Interferometric Observations of UGC 3789. Astrophys. J. 2009, 695, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braatz, J.A.; Reid, M.J.; Humphreys, E.M.L.; Henkel, C.; Condon, J.J.; Lo, K.Y. The Megamaser Cosmology Project. II. The Angular-diameter Distance to UGC 3789. Astrophys. J. 2010, 718, 657–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, M.J.; Braatz, J.A.; Condon, J.J.; Lo, K.Y.; Kuo, C.Y.; Impellizzeri, C.M.V.; Henkel, C. The Megamaser Cosmology Project. IV. A Direct Measurement of the Hubble Constant from UGC 3789. Astrophys. J. 2013, 767, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, C.Y.; Braatz, J.A.; Lo, K.Y.; Reid, M.J.; Suyu, S.H.; Pesce, D.W.; Condon, J.J.; Henkel, C.; Impellizzeri, C.M.V. The Megamaser Cosmology Project. VI. Observations of NGC 6323. Astrophys. J. 2015, 800, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Braatz, J.A.; Reid, M.J.; Lo, K.Y.; Condon, J.J.; Henkel, C.; Kuo, C.Y.; Impellizzeri, C.M.V.; Pesce, D.W.; Zhao, W. The Megamaser Cosmology Project. VIII. A Geometric Distance to NGC 5765b. Astrophys. J. 2016, 817, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesce, D.W.; Braatz, J.A.; Reid, M.J.; Riess, A.G.; Scolnic, D.; Condon, J.J.; Gao, F.; Henkel, C.; Impellizzeri, C.M.V.; Kuo, C.Y.; et al. The Megamaser Cosmology Project. XIII. Combined Hubble Constant Constraints. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2020, 891, L1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, C.Y.; Hsiang, J.Y.; Chung, H.H.; Constantin, A.; Chang, Y.Y.; Cunha, E.d.; Pesce, D.; Chien, W.T.; Chen, B.Y.; Braatz, J.A.; et al. A More Efficient Search for H2O Megamaser Galaxies: The Power of X-Ray and Mid-infrared Photometry. Astrophys. J. 2020, 892, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, J.E.; Seth, A.; Kim, M.; Läsker, R.; Goulding, A.; Gao, F.; Braatz, J.A.; Henkel, C.; Condon, J.; Lo, K.Y.; et al. Megamaser Disks Reveal a Broad Distribution of Black Hole Mass in Spiral Galaxies. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2016, 826, L32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neufeld, D.A. Response of Circumnuclear Water Masers to Luminosity Changes in an Active Galactic Nucleus. Astrophys. J. 2000, 542, L99–L103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neufeld, D.A.; Maloney, P.R.; Conger, S. Water maser emission from X-ray-heated circumnuclear gas in active galaxies. Astrophys. J. 1994, 628, L127–L130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrnstein, J.R.; Moran, J.M.; Greenhill, L.J.; Trotter, A.S. The Geometry of and Mass Accretion Rate through the Maser Accretion Disk in NGC 4258. Astrophys. J. 2005, 629, 719–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, K.Y. Mega-Masers and Galaxies. ARA&A 2005, 43, 625–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, M.D.; Baudry, A.; Richards, A.M.S.; Humphreys, E.M.L.; Sobolev, A.M.; Yates, J.A. The physics of water masers observable with ALMA and SOFIA: Model predictions for evolved stars. MNRAS 2016, 456, 374–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elitzur, M.; de Jong, T. A model for the maser sources associated with H II regions. Astron. Astrophys. 1978, 67, 323–332. [Google Scholar]

- Goldreich, P.; Kwan, J. Astrophysical Masers. V. Pump Mechanism for H2O Masers. Astrophys. J. 1974, 191, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collison, A.J.; Watson, W.D. Dust Grains and the Luminosity of Circumnuclear Water Masers in Active Galaxies. Astrophys. J. 1995, 452, L103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kuo, C.Y.; Constantin, A.; Braatz, J.A.; Chung, H.H.; Witherspoon, C.A.; Pesce, D.; Impellizzeri, C.M.V.; Gao, F.; Hao, L.; Woo, J.H.; et al. Enhancing the H2O Megamaser Detection Rate Using Optical and Mid-infrared Photometry. Astrophys. J. 2018, 860, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neufeld, D.A.; Maloney, P.R. The Mass Accretion Rate through the Masing Molecular Disk in the Active Galaxy NGC 4258. Astrophys. J. 1995, 447, L17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]