Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease and related neurodegenerative disorders are associated with progressive cognitive decline, primarily driven by cholinergic dysfunction and impaired synaptic signaling. Hericium erinaceus, also known as lion’s mane mushroom, has been reported to promote neuronal differentiation and synaptic plasticity. In this study, a standardized H. erinaceus extract powder (HEP) was prepared from fruiting bodies and quantified using hericene A as a marker compound. The neuroprotective effects of HEP were then evaluated in both cellular and animal models of scopolamine-induced cognitive dysfunction. Pretreatment of SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells with HEP (5–25 μg/mL) significantly improved cell viability and reduced scopolamine-induced apoptosis, while enhancing the activation of neuroplasticity-related signaling proteins, including brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB), and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK). In vivo, oral administration of HEP (300 mg/kg) to scopolamine-treated ICR mice markedly improved cognitive performance, increasing the recognition index to 63.8% compared with 41.6% in the scopolamine group, and enhancing spontaneous alternation in the Y-maze test to 59.6%. These cognitive improvements were accompanied by preserved hippocampal neuronal structure and increased BDNF immunoreactivity. Additionally, HEP improved cholinergic function by restoring serum acetylcholine levels and reducing acetylcholinesterase activity. Collectively, these findings suggest that standardized HEP exerts neuroprotective and cognition-enhancing effects via modulation of cholinergic markers and activation of BDNF-mediated neuroplasticity, highlighting its potential as a functional food ingredient or nutraceutical for preventing cognitive decline related to cholinergic dysfunction.

1. Introduction

Neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) are progressive disorders characterized by the deterioration of neuronal structure and function, leading to memory loss and cognitive impairment [1]. The global prevalence of AD continues to rise with the aging population, imposing an enormous socioeconomic burden on healthcare systems worldwide [2]. The cholinergic hypothesis remains a central framework for understanding AD pathophysiology, emphasizing the degeneration of cholinergic neurons and a consequent reduction in acetylcholine (ACh) levels in the brain [3,4,5]. Enhanced activity of acetylcholinesterase (AChE), the enzyme responsible for ACh degradation, further aggravates this deficit, resulting in synaptic failure and cognitive decline [3].

Current pharmacological therapies, such as AChE inhibitors including donepezil and rivastigmine, provide only transient symptomatic improvement without halting disease progression [6]. Moreover, their long-term use is limited by adverse effects such as hepatotoxicity and gastrointestinal disturbances. Consequently, growing attention has been directed toward natural products and functional foods with neuroprotective and cognition-enhancing properties as safer and more sustainable alternatives [7].

Among these, the edible and medicinal mushroom Hericium erinaceus (Bull.) Pers., commonly known as Lion’s mane mushroom, has been traditionally used in East Asia for promoting vitality and brain health [8,9,10]. Recent pharmacological studies have shown that extracts and isolated metabolites from H. erinaceus, including hericene A and hericenones of fruiting body and erinacines of mycelium, stimulate nerve growth factor (NGF) synthesis, promote neurite outgrowth, and improve learning and memory in preclinical models [11,12,13]. These findings suggest that H. erinaceus exerts neuroprotective effects primarily through the modulation of neurotrophic signaling pathways [14,15]. However, many earlier studies used non-standardized extracts, which limits the reproducibility of their findings, and the contributions of individual bioactive constituents within these extracts remain incompletely characterized [16].

To ensure reproducibility and biological efficacy, standardization of mushroom extracts based on chemical markers and validated manufacturing processes is essential. Hericene A, a major aromatic compound of H. erinaceus fruiting body, has been identified as a key bioactive constituent associated with neuronal differentiation and antioxidative activity [15,17,18]. Therefore, quantification of hericene A serves as a reliable index for the quality control of H. erinaceus fruiting body extracts and ensures consistency in pharmacological studies.

Neuroplasticity and neuronal survival are governed by several signaling cascades, among which brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and its downstream effectors—cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)—play pivotal roles [14,15]. Dysregulation of the BDNF/CREB/ERK pathway has been implicated in synaptic dysfunction and cognitive decline in AD [19]. Activation of this pathway promotes neuronal differentiation, synaptogenesis, and memory consolidation, suggesting that restoration of these mechanisms may counteract cholinergic impairment and neuronal loss.

The scopolamine-induced amnesia model, which reproduces cholinergic dysfunction and memory impairment, serves as a valuable experimental platform for evaluating neuroprotective interventions. However, the specific mechanisms by which H. erinaceus exerts protective effects against cholinergic deficits remain to be fully elucidated. Therefore, the present study investigated whether a standardized H. erinaceus extract powder (HEP) manufactured under controlled conditions and quantified using hericene A as a marker compound could ameliorate scopolamine-induced cognitive dysfunction. Both in vitro (SH-SY5Y cells) and in vivo (scopolamine-treated ICR mice) models were employed to assess neuronal viability, apoptosis, and activation of neuroplasticity-related proteins, including BDNF, CREB, and ERK. This integrated approach was designed to clarify the neuroprotective mechanisms of standardized H. erinaceus and to provide evidence supporting its potential use as a functional food ingredient for promoting brain health and preventing cognitive decline associated with neurodegenerative diseases.

Given that H. erinaceus is widely consumed as an edible mushroom, establishing a food-grade standardized extract with consistent hericene A levels is essential for its development as a functional food ingredient for brain health [20,21,22].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

H. erinaceus fruiting body (CNG farm, Cheongju, Republic of Korea), RPMI 1640, fetal bovine serum (FBS), scopolamine, donepezil, penicillin/streptomycin, BAX (2772s; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), Bcl-2 (3498s; Cell Signaling Technology), caspase 3 (9662s; Cell Signaling Technology), CREB (4820s; Cell Signaling Technology), p-CREB (9196s; Cell Signaling Technology), anti-protein kinase B, (Akt 9272s; Cell Signaling Technology), p-Akt (9271s; Cell Signaling Technology), ERK (9102s; Cell Signaling Technology), p-ERK (9101s; Cell Signaling Technology), anti-glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta (GSK-3β 9315s; Cell Signaling Technology), p- GSK-3β (9336s; Cell Signaling Technology), BDNF (A4873; Abclonal, Woburn, MA, USA), NGF (ab-6199; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH SC-32233; Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA, USA)

2.2. Preparation of the Standardized H. erinaceus Extract Powder (HEP)

The extract powder of H. erinaceus prepared using a two-step ethanol extraction process under GMP-compliant, food-grade, large-scale manufacturing conditions was provided by Doobon Inc. (Cheongju, Republic of Korea) and produced under predefined quality control criteria. Briefly, dried fruiting bodies were extracted with 70% ethanol and filtered to remove insoluble residues. The resulting solution was concentrated under reduced pressure using a rotary vacuum evaporator (–600 to –750 mmHg). The final concentrate was blended with an excipient and spray-dried to produce HEP.

2.3. Quantitation of Hericene A

The content of hericene A, a chemical marker used for extract standardization and quality control, was quantitatively determined using liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC/MS) [20]. Hericene A powder (10 mg) was dissolved in 10 mL of methanol, and a standard stock solution was prepared at a concentration of 1000 mg/L. Standard solutions of 0.5, 2.0, 5.0, 10, 20, and 50 mg/L were prepared with methanol for analysis. For the quantitation of hericene A, 1 g of the HEP was extracted with 10 mL of methanol. LC/MS analysis was performed on an Agilent 6475 LC/TQ, using a Waters XBridge BEH C18 column (2.1 mm X 100 mm, 3.5 μm particle size). The mobile phase consisted of (A) water and (B) methanol, and the following linear gradient program was used: b; 0–5 min, 97% B; 5–10 min, 97–100% B; 10.0–10.1 min, 100–97% B; 10.1–15 min, 97% B. The flow rate was 3.0 mL/min, injection volume; The pore size was set to 0.2 μm. MS conditions were set to positive mode of electrospray ionization (ESI), precursor ion (557 m/z), product ion (301,177, m/z), and ion collision energy (CE; 30 eV). HA quantification was performed by an external calibration method using a standard curve prepared with previously isolated purified hericene A (purity > 98%). The HA concentration of each sample was expressed as mg per 1 g of extract powder. Batch-to-batch consistency of the extract was assessed by quantifying hericene A across three independent GMP production batches (Table S1). Efficacy evaluations were conducted using a single GMP production batch to minimize experimental variability.

2.4. Cell Culture and Sample Treatment

SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells (Korea Cell Line Bank, Seoul, Republic of Korea) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin–streptomycin. Cells were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2. SH-SY5Y cells were pretreated with various concentrations of HEP. After incubation for 1 h at 37 °C, 5 mM scopolamine was treated for 24 h at 37 °C. To determine the appropriate scopolamine concentration, a preliminary concentration–response viability experiment was conducted in SH-SY5Y cells exposed to 1, 3 and 5 mM scopolamine for 24h. Cell viability was assessed using an MTT assay (n = 3 independent experiments). A dose-dependent reduction in cell viability was observed, with 5 mM scopolamine resulting in approximately 60% viability. This concentration provided a reproducible injury window with sufficient dynamic range for subsequent mechanistic analyses. Therefore, 5 mM scopolamine was selected for subsequent mechanistic assays (Figure S2).

HEP was freshly prepared in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for in vitro experiments and diluted in culture medium to achieve the indicated final concentrations. Vehicle control cells received the equivalent volume of PBS.

2.5. Western Blot Analysis

Total proteins from SH-SY5Y cells and mouse brain tissues were extracted using PRO-PREP™ protein extraction buffer (iNtRON, Seoul, Republic of Korea). The lysates were incubated at −20 °C for 24 h to ensure complete solubilization, followed by centrifugation to remove cellular debris. Protein concentrations were quantified by the Bradford colorimetric method. Equal amounts of protein (30–50 µg) were resolved on SDS–polyacrylamide gels and electrotransferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes using a Trans-Blot® Turbo™ system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween-20 (TBST) for 1 h and then incubated overnight at 4 °C with the appropriate primary antibodies. After washing, membranes were exposed to HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature (approximately 25 °C). Immunoreactive bands were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence using a ChemiDoc™ XRS+ imaging platform (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA), and band intensities were analyzed densitometrically.

2.6. Animals and Study Design

ICR male mice (6 weeks old; Orient Bio, Seongnam, Republic of Korea) were housed under standard laboratory conditions (22 ± 2 °C, 65% humidity, 12 h light/dark cycle). All experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Gachon University (Approval No. GU1-2022-IA0046). For in vivo oral administration, HEP was prepared in saline and administered by gavage at a constant dosing volume. Vehicle control groups received an equivalent volume of saline.

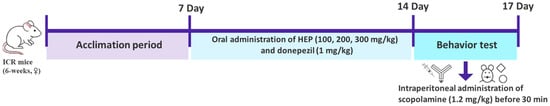

After a 1-week acclimation period, mice were randomly divided into six groups (n = 8 per group): vehicle control (CON), scopolamine only (Sco), Sco + HEP 100 mg/kg, Sco + HEP 200 mg/kg, Sco + HEP 300 mg/kg, and Sco + donepezil 1.0 mg/kg (positive control). HEP and donepezil were administered orally once daily for 7 days. Scopolamine (1.2 mg/kg, i.p.) was injected 30 min before the behavioral experiments to induce cholinergic dysfunction [23,24] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the experimental plan.

2.7. Novel Object Recognition Test (NORT)

The NORT was conducted to assess recognition memory in mice. During the acquisition phase, each mouse was placed in the testing arena containing two identical objects and allowed to explore freely for 3 min. After a 24 h retention period, a probe trial was performed by replacing one of the familiar objects with a novel one to evaluate recognition performance. Distinct plastic objects with different shapes and colors were used across trials to prevent location or object bias. Exploration behavior was defined as direct interaction with an object, such as sniffing or touching it within approximately 1 cm.

Both the training and probe sessions lasted for 3 min each. The duration of exploration directed toward the familiar and novel objects was recorded, and recognition memory was quantified by comparing the time spent exploring the novel object relative to the familiar one. A higher preference for the novel object was interpreted as improved recognition memory [25]. All videos were analyzed using SMART3.0 SUPER PACK (PanLab; Harvard Apparatus, Barcelona, Spain).

Endpoint-specific validity and quality criteria were applied for the Novel Object Recognition Test (NORT; 3 min test phase), including predefined exclusion rules for missing or unreliable video/tracking data and insufficient total object exploration time (<10 s).

2.8. Y-Maze Test

The Y-maze test was conducted to assess spatial working memory based on the innate exploratory behavior of rodents. Each mouse was gently placed at the end of one arm of a symmetrical Y-shaped maze (40 × 8 × 20 cm; length × width × height) and allowed to freely explore all three arms for 8 min. The sequence of arm entries was recorded using an overhead camera system to analyze movement patterns and exploration order. A spontaneous alternation was defined as consecutive entries into three different arms forming overlapping triplet sequences (e.g., in the sequence ACBCABCBCA, five alternations were identified). The percentage of spontaneous alternation was calculated as the number of actual alternations divided by the maximum possible alternations, which was determined by subtracting two from the total number of arm entries. A higher alternation percentage was considered to reflect improved spatial working memory performance. All videos were analyzed using SMART3.0 SUPER PACK (PanLab; Harvard Apparatus, Barcelona, Spain). Endpoint-specific validity and quality criteria were applied for the Y-maze test (8 min), including predefined exclusion rules for missing or unreliable video/tracking data and insufficient arm entries (<8 total entries)

2.9. Preparation of Mouse Plasma and Brain Tissue Sections

Plasma and brain samples were prepared following procedures adapted from previously reported protocols [25]. After euthanasia, blood was collected by cardiac puncture into EDTA-coated tubes to prevent coagulation. The samples were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 30 min, and the resulting supernatant was collected as plasma. For tissue preparation, mice were transcardially perfused with 0.05 M PBS, followed by fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer. Brains were then extracted, post-fixed overnight at 4 °C, and subsequently stored in 30% sucrose in PBS for cryoprotection. A microtome (hm355s, Leica Microsystems, Nussloch, Germany) was employed to section the fixed brain tissues at a thickness of 25 μm for histological examination.

2.10. Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) Staining

Brain tissues were immersed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for fixation, followed by sequential dehydration through graded ethanol solutions and clearing in xylene. The samples were then embedded in paraffin to prepare tissue blocks. Paraffin-embedded sections were cut to a thickness of 5 µm using a rotary microtome and subsequently stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The stained sections were examined and digitally scanned using a 3D Histech scanner (3DHISTECH Ltd., Budapest, Hungary) for histopathological analysis and image acquisition at 4× and 10× magnifications.

2.11. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) Analysis

Immunohistochemical staining for BDNF was performed on paraffin-embedded hippocampal sections to assess neurotrophic factor expression. Brain tissues were deparaffinized in xylene, rehydrated through a graded ethanol series, and subjected to antigen retrieval using 0.01 M citrate buffer (pH 6.0) at 95 °C for 15 min. After cooling to room temperature, endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 10 min, followed by incubation with 5% normal goat serum in PBS for 1 h to minimize nonspecific binding. The sections were then incubated overnight at 4 °C with a primary anti-BDNF antibody (1:200; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), washed in PBS, and subsequently incubated with a biotinylated secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. Immunoreactivity was visualized using a DAB substrate kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA), after which the sections were counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated, and mounted. Stained tissues were examined and digitally scanned using a 3D Histech scanner (3DHISTECH Ltd., Budapest, Hungary), and the intensity and distribution of BDNF expression were analyzed in the hippocampal CA1, CA3, and DG regions.

For quantitative analysis, digital images were analyzed using ImageJ/FIJI software (2.9.0 version/1.54 version, NIH, USA). Images were converted to 8-bit format (Image → Type → 8-bit), and regions of interest (ROIs) corresponding to the CA1, CA3, and dentate gyrus (DG) were delineated based on anatomical landmarks. DAB-positive staining was segmented using a fixed intensity threshold (lower = 0, upper = 147; 8-bit grayscale units) that was applied uniformly across all images. The primary quantitative metric was the percentage of positive area (area fraction) of threshold-positive pixels within each ROI (Analyze → Set Measurements → Area fraction). For each animal, measurements were obtained from a single hippocampal section, and group data represent n = 3 animals per group (Tables S2–S7).

2.12. Statistical Analysis

All data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism version 8.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) and SPSS version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Differences among groups were assessed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison post hoc test. Comparisons between two groups were evaluated using independent t-tests, and Bonferroni correction was applied when appropriate to control for multiple testing. Statistical significance was accepted at p < 0.05.

Formal a priori power calculations were not performed. The number of animals analyzed (n) may vary across endpoints due to the application of predefined, objective validity and quality-control criteria. Accordingly, n is reported as a range in the figure legends.

3. Results

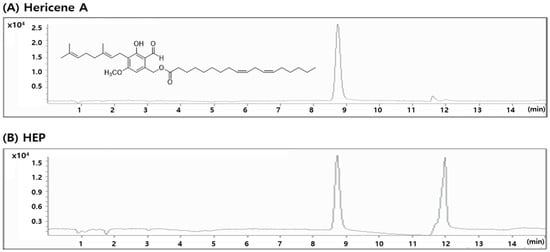

3.1. Quantification of Hericene A in HEP

Quality control of HEP was performed by quantifying the hericene A content (Figure 2). Quantitative LC-MS analysis revealed that the extract contained 1.24 ± 0.02 mg hericene A per gram of HEP, confirming the high enrichment of this bioactive marker compound. This standardized extract, characterized by reproducible hericene A levels, was used in all in vitro and in vivo experiments to assess its neuroprotective and cognition-enhancing activities.

Figure 2.

LC/MS chromatogram of hericene A (A) and HEP (B).

Furthermore, quantitative analysis of hericene A across different production batches showed consistent concentrations (Table S1). The observed low inter-batch variability confirms the robustness and reproducibility of the GMP-compliant manufacturing process applied to HEP.

Although hericene A was used as the quantitative marker compound in this study, other neuroactive constituents such as hericenones and erinacines may also contribute to the observed effects. Future studies integrating targeted phytochemical profiling and structure–activity relationship (SAR) analyses will help clarify the synergistic or complementary roles of these compounds in neuroprotection and cognitive enhancement.

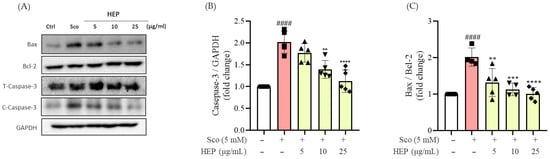

3.2. Effects of HEP on Scopolamine-Induced Expression of Related Apoptosis Pathways in SH-SY5Y Cells

To investigate the potential protective effects of standardized HEP against scopolamine-induced neuronal apoptosis, SH-SY5Y cells were pretreated with HEP for 1 h prior to exposure to 5 mM scopolamine for 24 h. In this study, untreated cells served as the normal control, and the scopolamine-only group was used as the negative control to establish apoptosis induction.

As shown in Figure 3, exposure to scopolamine alone markedly increased the Bax/Bcl-2 ratio and cleaved caspase-3 expression compared with the untreated control group (#### p < 0.0001), indicating activation of the intrinsic apoptotic cascade. In contrast, pretreatment with HEP effectively reversed these changes in a concentration-dependent manner. HEP at 10 and 25 μg/mL significantly reduced the Bax/Bcl-2 ratio (** p < 0.01) and the level of cleaved caspase-3 (* p < 0.05), suggesting a restoration of anti-apoptotic balance.

Figure 3.

(A) Western blotting analysis (A) and the expression fold changes of (B) cleaved-caspase-3/total-caspase-3 and (C) BAX/Bcl-2 in scopolamine-induced SH-SY5Y cells. All protein levels were normalized to those of GAPDH. All data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 4–5). #### p < 0.0001 vs. Ctrl, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 and **** p < 0.0001 vs. scopolamine-induced group (Sco).

Notably, the highest concentration of HEP (25 μg/mL) almost completely normalized the Bax/Bcl-2 ratio and caspase-3 cleavage to levels comparable with those of the control group. These findings indicate that HEP mitigates scopolamine-induced neuronal apoptosis by modulating intrinsic apoptotic signaling pathways and maintaining cell survival homeostasis.

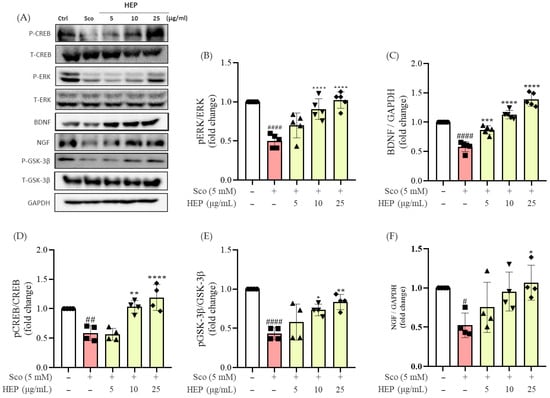

3.3. Effects of HEP on Scopolamine-Induced Expression of Neuroplasticity-Related Signaling Pathways in SH-SY5Y Cells

Exposure of SH-SY5Y cells to 5 mM scopolamine for 24 h markedly reduced the expression of neuroplasticity-related proteins, including BDNF, phosphorylated CREB (p-CREB), phosphorylated ERK (p-ERK), and phosphorylated GSK3β (p-GSK3β), compared with untreated control cells. In contrast, pretreatment with HEP for 1 h significantly reversed these effects in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Western blotting was performed to measure the expression levels of BDNF, NGF, p-CREB/T-CREB, p-ERK/T-ERK, and pGSK-3β/GSK-3β in scopolamine-induced SH-SY5Y cells. (A) Western blots, and expression fold changes of (B) p-ERK/T-ERK, (C) BDNF, (D) p-CREB/T-CREB, (E) pGSK-3β/GSK-3β and (F) NGF. All protein levels were normalized to those of GAPDH. Data represent the mean ± SD (n = 4–5). # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01 and #### p < 0.0001 vs. Ctrl; * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 and **** p < 0.0001 vs. scopolamine-induced group (Sco).

Specifically, HEP at 10 and 25 μg/mL markedly restored the phosphorylation levels of CREB and ERK (### p < 0.001) and increased BDNF expression (### p < 0.001) toward those observed in control cells. Notably, high-dose HEP (25 μg/mL) almost completely normalized BDNF and p-CREB levels, suggesting strong activation of neurotrophic signaling.

Collectively, these findings indicate that HEP counteracts scopolamine-induced suppression of neuroplasticity and is associated with activation of the BDNF/CREB/ERK and AKT/GSK3β signaling pathways. Together, these molecular changes may contribute to enhanced neuronal survival and functional recovery under conditions of cholinergic stress.

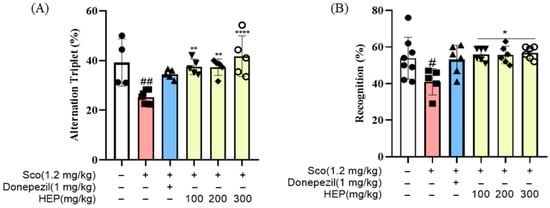

3.4. The Treatment of HEP Ameliorates Scopolamine-Induced Cognitive Deficits in Mice Models

To determine whether scopolamine-induced memory impairments could be alleviated by treatment with HEP, we administered HEP (100, 200 and 300 mg/kg, p.o.) for seven consecutive days to ICR mice prior to scopolamine injection (1.2 mg/kg, i.p.) (Figure 1). In the Y-maze test, scopolamine treatment markedly reduced the percentage of spontaneous alternation (38.25 ± 3.14%, ## p < 0.01) compared with the control group, indicating impairment of spatial working memory. Notably, this decline was significantly reversed in the HEP-treated groups, with 200 mg/kg and 300 mg/kg of HEP increasing alternation performance to 54.72 ± 2.83% (** p < 0.01) and 59.63 ± 2.24% (*** p < 0.001), respectively, values comparable to those in the donepezil-treated positive control (1 mg/kg) group (Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

(A) Percentage of spontaneous alternation and total distance traveled in the Y-maze test. (B) Recognition index and total distance traveled in the NORT. Each behavioral parameter was analyzed using SMART 3.0 SUPER PACK (Panlab; Harvard Apparatus, Barcelona, Spain). All data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 4–8). # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01 vs. Ctrl; * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and **** p < 0.0001 vs. scopolamine-induced group (Sco).

Similarly, in the NORT, the scopolamine group exhibited a significant decrease in the recognition index (41.62 ± 2.45%, ## p < 0.01) relative to control animals, reflecting impairment in recognition memory. However, pretreatment with HEP dose-dependently restored this parameter, with 300 mg/kg HEP increasing the recognition index to 63.84 ± 2.76% (*** p < 0.001), nearly identical to that of the control group (Figure 5B). Collectively, these results demonstrate that oral administration of HEP effectively mitigates scopolamine-induced cognitive deficits by enhancing hippocampal-dependent learning and memory functions, suggesting that HEP exerts potent neuroprotective and cognition-enhancing effects in vivo.

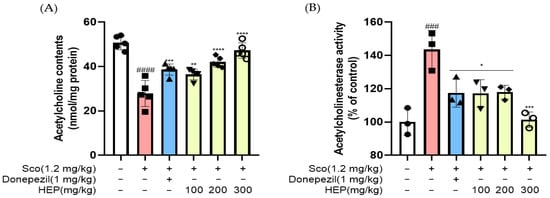

3.5. The Treatment of HEP Restores Cholinergic Dysfunction in Scopolamine-Induced Mice Models

Having observed that HEP improved behavioral performance in scopolamine-treated mice, we next examined whether these effects were associated with restoration of the central cholinergic system. As shown in Figure 6 scopolamine administration (1.2 mg/kg, i.p.) significantly decreased acetylcholine (ACh) levels while increasing acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity compared with the control group, confirming cholinergic dysfunction. Conversely, oral administration of HEP (100, 200 and 300 mg/kg) effectively reversed these alterations in a dose-dependent manner.

Figure 6.

(A) Acetylcholine (ACh) levels and (B) acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity in serum following oral administration of HEP (100, 200, and 300 mg/kg) or donepezil (1.0 mg/kg) in scopolamine-induced mice. All data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3–5). ### p < 0.001, #### p < 0.0001 vs. Ctrl; * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 and **** p < 0.0001 vs. scopolamine-induced group (Sco).

Specifically, HEP markedly restored ACh content (#### p < 0.0001) and simultaneously suppressed AChE activity (### p < 0.001) toward control levels. The higher dose of HEP (300 mg/kg) nearly normalized both parameters, producing effects comparable to those of the donepezil-treated positive control group (1 mg/kg). This normalization of cholinergic markers indicates that HEP counteracted the scopolamine-induced disruption of acetylcholine turnover by modulating ACh synthesis and degradation. Collectively, these findings suggest that HEP restores central cholinergic homeostasis, which may contribute to its observed cognition-enhancing and neuroprotective effects in vivo.

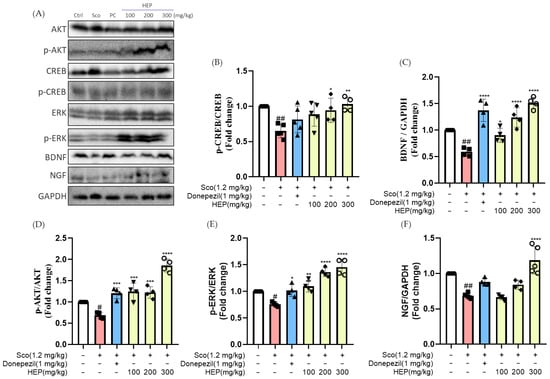

3.6. HEP Activates Neurotrophic and Survival-Related Signaling Pathways in the Brains of Scopolamine-Induced Mice

In line with the behavioral and cholinergic improvements observed above, we next investigated whether HEP could activate neurotrophic and neuronal survival-related signaling pathways in the brain. As shown in Figure 7, scopolamine administration (1.2 mg/kg, i.p.) markedly reduced the expression of neurotrophic factors BDNF and NGF, as well as the phosphorylation of CREB, ERK, and AKT, compared with the control group (### p < 0.001). These alterations indicate that scopolamine induces significant suppression of neuroplasticity and survival signaling.

Figure 7.

Western blotting was performed to measure the expression levels of BDNF, NGF, p-CREB/T-CREB, p-ERK/T-ERK, and p-AKT/T-AKT in the hippocampal tissues of scopolamine-induced mice. (A) Western blots, and expression fold changes of (B) p-CREB/T-CREB, (C) BDNF, (D) p-AKT/T-AKT, (E) p-ERK/T-ERK and (F) NGF. All protein levels were normalized to those of GAPDH. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 4–5). # p < 0.05 and ## p < 0.01 vs. Ctrl; * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 and **** p < 0.0001 vs. scopolamine-induced group (Sco).

Oral treatment with HEP (100, 200 and 300 mg/kg) for seven consecutive days effectively reversed these deficits in a concentration-dependent manner. HEP significantly increased the expression of BDNF (### p < 0.001) and NGF (### p < 0.001) while enhancing the phosphorylation of CREB, ERK, and AKT toward control levels (### p < 0.001 for all). The high-dose HEP group (300 mg/kg) exhibited BDNF and p-CREB levels comparable to those in the donepezil-treated group, suggesting strong activation of neurotrophic signaling cascades. Collectively, these results indicate that the cognition-enhancing and neuroprotective effects of HEP were accompanied by reactivation of BDNF/NGF-mediated CREB, ERK, and AKT signaling pathways, which may support neuronal survival and synaptic resilience under conditions of cholinergic stress.

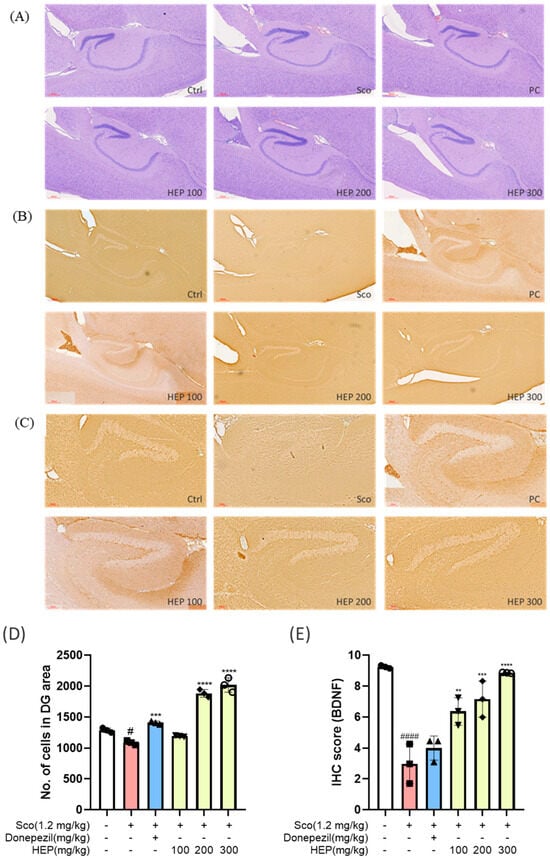

3.7. HEP Mitigates Hippocampal Neuronal Damage and Restores BDNF Expression in Scopolamine-Induced Mice

Histopathological analysis was performed to determine whether HEP protects the dentate gyrus (DG) from scopolamine-induced injury and restores neurotrophic signaling. As shown in Figure 8A, hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining revealed pronounced neuronal loss and laminar disorganization in scopolamine-treated mice compared with controls, whereas oral HEP (100–300 mg/kg) attenuated these alterations in a dose-dependent manner; cytoarchitecture at 200–300 mg/kg resembled the donepezil group. To link morphology with neurotrophic activity, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) was assessed by immunohistochemistry (IHC) focused on the DG (Figure 8B,C).

Figure 8.

(A) H&E, hippocampus overview including CA fields and DG, 4×. (B) BDNF IHC, hippocampus overview including DG, 4×. (C) BDNF IHC, dentate gyrus (DG) high magnification, 10×. (D) DG neuronal density from H&E (cell counting by ImageJ version 1.54p). (E) DG BDNF immunoreactivity (ImageJ; area fraction/integrated density). Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3). # p < 0.05 and #### p < 0.0001 vs. Ctrl; ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 and **** p < 0.0001 vs. scopolamine-induced group (Sco).

ImageJ-based quantification restricted to the DG confirmed significant improvements with HEP. Neuronal density (H&E cell counting; Figure 8D) increased in a concentration-dependent fashion relative to the scopolamine group (one-way ANOVA with Tukey): HEP 100 showed a modest rise (# p < 0.05 vs. Sco), HEP 200 a larger increase (** p < 0.01), and HEP 300 the greatest recovery (*** p < 0.001). A similar dose-responsive restoration of BDNF immunoreactivity (Figure 8E) was observed: HEP 100, 200, and 300 mg/kg progressively elevated BDNF-positive staining versus scopolamine alone (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, respectively). Together, these DG-focused data indicate that HEP preserves hippocampal structure and enhances BDNF-linked neuroplasticity under cholinergic stress.

4. Discussion

In the present study, a standardized HEP was developed through a reproducible two-step ethanol-extraction process designed for food-grade and large-scale production. Previous studies have reported that the hericene A content in H. erinaceus extract was 0.74 mg/g [26]. The concentration of hericene A is known to vary depending on multiple factors, including the raw material, such as fruiting bodies, mycelium, extraction and drying processes, and analytical conditions [27]. In the present study, hericene A was selected as the marker compound for quantitative analysis. As a result, the final extract was standardized to contain 1.24 mg/g of hericene A, demonstrating a higher and consistent content of this bioactive marker compared with previously reported values. This standardization process is critical for establishing both the quality and biological reliability of natural product-based interventions, as variability in extraction or composition can lead to inconsistent pharmacological outcomes [19,28].

Standardized HEP exerted significant neuroprotective and cognition-enhancing effects against scopolamine-induced neurotoxicity in both cellular and animal models. Scopolamine, a muscarinic receptor antagonist, is widely used to induce memory impairment by disrupting cholinergic neurotransmission and synaptic plasticity [16,29]. The impairment of the cholinergic system is a major pathological hallmark of AD and other forms of dementia, characterized by reduced ACh levels, increased AChE activity, and altered neuronal survival signaling [30,31]. Consistent with this, our results revealed that scopolamine exposure markedly decreased ACh levels, increased AChE activity, and suppressed the expression of neuroplasticity-related proteins such as BDNF, NGF, p-CREB, p-ERK, and p-AKT, leading to cognitive deficits and hippocampal neuronal damage.

Oral administration of HEP effectively mitigated these deleterious effects in a dose-dependent manner. In vitro, HEP suppressed apoptosis-related markers, including Bax/Bcl-2 imbalance and caspase-3 activation, indicating protection against scopolamine-induced neuronal apoptosis. In vivo, behavioral tests such as the Y-maze and NORT demonstrated that HEP significantly improved spatial working and recognition memory, comparable to the effects observed with donepezil, a standard AChE inhibitor [32]. These behavioral improvements were accompanied by restoration of cholinergic neurotransmission, as evidenced by normalized ACh content and reduced AChE activity. Taken together, these findings suggest that the cognitive benefits of HEP are closely associated with its ability to restore cholinergic balance and prevent neuronal loss.

Histological analyses further supported these biochemical and behavioral outcomes. H&E staining revealed that scopolamine induced neuronal loss and disorganization in the hippocampal CA1–CA3 and DG regions, whereas HEP preserved neuronal morphology in a concentration-dependent manner. IHC analysis demonstrated that HEP significantly enhanced BDNF expression in the hippocampus, particularly in the CA1 and DG subregions, which are critical for learning and memory. The upregulation of BDNF, along with the activation of its downstream targets CREB, ERK, and AKT, indicates that HEP promotes neuroplasticity and neuronal survival under cholinergic stress.

BDNF and NGF are key neurotrophins that play pivotal roles in synaptic maintenance, axonal growth, and neuronal differentiation [33]. Their downregulation under cholinergic dysfunction contributes to synaptic failure and cognitive decline. In this context, the observed recovery of both BDNF and NGF expressions following HEP treatment provides strong evidence that HEP exerts neurotrophic modulation comparable to classical nootropic compounds. Furthermore, the concurrent activation of CREB and ERK pathways suggests that HEP facilitates LTP-related molecular processes, thereby supporting sustained cognitive improvement. In addition to these parallel readouts, potential crosstalk between the BDNF/CREB/ERK and AKT/GSK-3β cascades warrants consideration. BDNF/TrkB signaling can engage both the MAPK/ERK and PI3K/AKT pathways, which may converge on shared downstream effectors, including CREB-dependent transcriptional programs that support neuronal survival and synaptic plasticity. Furthermore, GSK-3β may act as an integration node, as its inhibitory regulation is directly influenced by AKT and may intersect with MAPK/ERK-associated downstream signaling involved in plasticity-related processes. Importantly, these interactions are discussed as mechanistic plausibility rather than experimentally established causality, consistent with our moderated interpretation. Mechanistically, these effects may be attributed to bioactive compounds in H. erinaceus, including hericenones and erinacines, which have been reported to cross the blood–brain barrier and stimulate neurotrophic factor synthesis [19]. These compounds can activate the BDNF/TrkB and NGF/TrkA pathways, potentially promoting neuronal survival and synaptic repair. Our data align with these observations, suggesting that HEP acts through multiple convergent pathways—enhancing neurotrophic signaling, restoring cholinergic homeostasis, and suppressing apoptosis—to achieve synergistic neuroprotection.

Beyond its neurochemical and histological benefits, HEP also demonstrated translational potential as a functional food or nutraceutical ingredient for cognitive health. Compared with synthetic AChE inhibitors, HEP offers multi-target modulation with fewer adverse effects. From a translational perspective, available human supplement-use data and limited clinical studies on H. erinaceus preparations generally suggest acceptable tolerability when used within commonly studied oral dose ranges. However, safety profiles may vary depending on formulation, extract standardization, and duration of intake. For context, the highest mouse dose used in this study (300 mg/kg/day) corresponds to an approximate human-equivalent dose of ~24 mg/kg/day (≈1.5–1.7 g/day for a 60–70 kg adult) based on standard body-surface-area scaling. Because long-term supplementation may be required to achieve durable cognitive benefits, future studies should evaluate sustained efficacy and safety with extended dosing, including monitoring for potential drug–supplement interactions and routine safety parameters. Importantly, these translational considerations are provided for context only and are not intended as clinical dosing recommendations; rigorous clinical trials using well-standardized products are needed to establish safety and efficacy in humans.

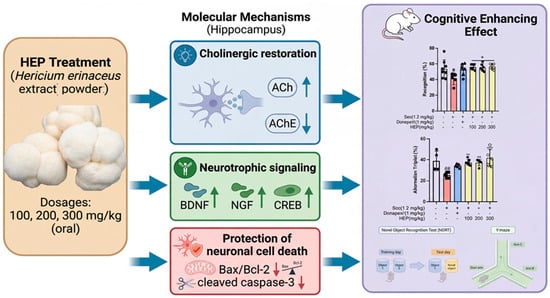

The present study focused on short-term administration in preclinical models; thus, further long-term and mechanistic studies are required to confirm efficacy and safety in humans. Moreover, while our findings provide strong evidence for neurotrophic and cholinergic regulation, the precise molecular constituents responsible for these effects remain to be elucidated through targeted phytochemical and pharmacokinetic analyses. Collectively, HEP demonstrated a robust ability to ameliorate scopolamine-induced cognitive dysfunction, accompanied by restoration of cholinergic transmission, enhancement of neurotrophic/survival signaling (BDNF/NGF–CREB/ERK/AKT axis), and protection against hippocampal neuronal loss. Taken together, these findings suggest that HEP may represent a promising neuroprotective candidate, potentially acting through coordinated modulation of cholinergic and neurotrophic/survival-related pathways. Importantly, although improvements in cholinergic markers and neurotrophic/survival signaling were observed concurrently, the present study demonstrates an association rather than a direct causal relationship between these processes. Accordingly, the proposed sequence of events is presented as a working hypothesis in a schematic model (Figure 9), with putative links indicated by dashed arrows. Future studies employing pathway-specific modulators or inhibitors (e.g., targeting the TrkB/MEK/PI3K axis) will be necessary to establish directionality and causality.

Figure 9.

Proposed working model of HEP action in scopolamine-induced cholinergic dysfunction. Solid arrows indicate experimentally supported findings from the present study, whereas dashed arrows denote putative links or hypothesized directionality. The model illustrates the concurrent modulation of cholinergic markers and neurotrophic/survival signaling pathways (BDNF/NGF–CREB/ERK/AKT/GSK3β) by HEP. # p < 0.05 and ## p < 0.01 vs. Ctrl; * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

Although direct comparative studies were not performed, the observed behavioral and molecular effects of HEP are consistent with those reported for well-known neuroprotective agents such as Ginkgo biloba extract (EGb761) in similar scopolamine-induced models. Previous work by our group has also demonstrated synergistic cognitive benefits when combining G. biloba and H. erinaceus extracts [16], supporting the relevance of HEP as a stand-alone or adjunct functional ingredient for memory enhancement.

Several limitations of the present study should be acknowledged. First, our in vivo experiments employed an acute scopolamine paradigm, which models transient cholinergic dysfunction but does not fully recapitulate progressive neurodegeneration; future studies using chronic paradigms and extended dosing schedules are warranted. Second, HEP was not tested in AD transgenic or disease-relevant models incorporating amyloid- or tau-related pathology, which will be important for assessing pathology-linked endpoints. Third, we did not perform pharmacokinetic, brain exposure, blood–brain barrier penetration, or target-engagement studies; future work should quantify marker compounds in plasma and brain and establish exposure–response relationships.

Despite these limitations, our findings support HEP as a promising H. erinaceus preparation that improves scopolamine-associated behavioral and molecular outcomes and provides a working framework for subsequent mechanistic and translational studies.

5. Conclusions

This study provides compelling evidence that HEP exerts potent neuroprotective and cognition-enhancing effects against scopolamine-induced neurotoxicity. Using both in vitro and in vivo models, HEP was shown to restore neuronal viability, suppress apoptosis, and normalize cholinergic transmission, as reflected by increased ACh levels and reduced AChE activity. Moreover, HEP activated neurotrophic signaling pathways involving BDNF, NGF, CREB, ERK, and AKT, which may contribute to neuronal survival, synaptic plasticity, and hippocampal integrity. Histological and IHC analyses further revealed that HEP preserved neuronal morphology and enhanced BDNF expression in the hippocampal CA1 and DG regions. These multifaceted effects suggest that HEP mitigates cognitive decline through coordinated modulation of cholinergic and neurotrophic systems.

Taken together, these findings highlight HEP as a promising functional dietary candidate for the prevention or adjunctive management of neurodegenerative disorders, particularly those associated with cholinergic dysfunction and impaired neuroplasticity. Further clinical and mechanistic studies are warranted to confirm its efficacy and determine optimal dosing for human application.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/scipharm94010012/s1. Table S1: Hericene A content across three independent GMP production batches of H. erinaceus extract powder (HEP); Table S2: Western blot analysis of apoptosis-related proteins in scopolamine-treated SH-SY5Y cells; Table S3: Western blot analysis of neurotrophic/survival signaling in scopolamine-treated SH-SY5Y cells; Table S4: Behavioral performance in scopolamine-treated mice; Table S5: Serum cholinergic parameters in scopolamine-treated mice; Table S6. Western blot analysis of neurotrophic/survival signaling in scopolamine-treated mice; Table S7: Hippocampal histological and immunohistochemical quantification in scopolamine-treated mice; Figure S1: Establishment of in vitro injury and assessment of HEP cytotoxicity in SH-SY5Y cells; Figure S2: Original images of Western blot for Figure 3. Figure S3. Original images of Western blot for Figure 4. Figure S4. Original images of Western blot for Figure 7.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.-H.K., S.J.K., S.M.H., Y.G.K., M.K.L. and S.Y.K.; Methodology, S.-H.K., S.J.K., E.J.K., S.H.R., Y.G.K., J.Y.Y., H.R.L. and S.M.H.; Software, S.-H.K., S.M.H.; Formal analysis, S.-H.K., S.J.K., S.M.H. and E.J.K.; Investigation, S.-H.K., S.J.K., S.M.H., S.H.R., D.H.L., Y.G.K., J.Y.Y., J.K.L., E.J.K., M.K.L. and S.Y.K.; Resources, Y.G.K., J.K.L. and S.Y.K.; Writing—original draft preparation, S.-H.K., S.J.K., M.K.L. and S.Y.K.; writing—review and editing, S.-H.K., S.J.K., M.K.L. and S.Y.K.; supervision, M.K.L. and S.Y.K.; Project administration, M.K.L. and S.Y.K.; funding acquisition, Y.G.K., M.K.L. and S.Y.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Regional Specialized Industry Development Plus Program (R&D, S3401722) through the Korea Technology and Information Promotion Agency for SMEs (TIPA) funded by the Ministry of Small- and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs) and Startups (MSS) Korea, and by Basic Research Program (2022R1A2C1008081) of the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government, and Gachon University Research Fund 2023 (GCU-202401150001).

Institutional Review Board Statement

All experimental procedures involving animals were reviewed and approved by the Animal Care Committee of the Center for Animal Care and Use (Approval no. GU1-2022-IA0046, dated 9 January 2022) at the College of Pharmacy, Gachon University, Korea.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed in this study are included in this article and its Supplementary Data Files.

Conflicts of Interest

Dae Hee Lee, Young Guk Kim, Jeong Yun Yu were employed by the company Doobon Inc. and Jae Kang Lee was employed by the company CNGbio Corp. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Kumar, A.; Singh, A.; Ekavali. A review on Alzheimer’s disease pathophysiology and its management: An update. Pharmacol. Rep. 2015, 67, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.P.; Xie, Y.; Meng, X.Y.; Kang, J.S. History and progress of hypotheses and clinical trials for Alzheimer’s disease. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2019, 4, 37, Correction in Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2019, 4, 29. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-019-0063-8.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francis, P.T.; Palmer, A.M.; Snape, M.; Wilcock, G.K. The cholinergic hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: A review of progress. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1999, 66, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampel, H.; Mesulam, M.M.; Cuello, A.C.; Khachaturian, A.S.; Vergallo, A.; Farlow, M.R.; Snyder, P.J.; Giacobini, E.; Khachaturian, Z.S.; Grp, C.S.W.; et al. Revisiting the cholinergic hypothesis in Alzheimer’s disease: Emerging evidence from translational and clinical research. J. Prev. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2019, 6, 2–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.R.; Huang, J.B.; Yang, S.L.; Hong, F.F. Role of Cholinergic Signaling in Alzheimer’s Disease. Molecules 2022, 27, 1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marucci, G.; Buccioni, M.; Dal Ben, D.; Lambertucci, C.; Volpini, R.; Amenta, F. Efficacy of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropharmacology 2021, 190, 108352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howes, M.J.R.; Perry, E. The Role of Phytochemicals in the Treatment and Prevention of Dementia. Drug Aging 2011, 28, 439–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M. Chemistry, nutrition, and health-promoting properties of (Lion’s Mane) mushroom fruiting bodies and mycelia and their bioactive vompounds. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 7108–7123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, K.; Inatomi, S.; Ouchi, K.; Azumi, Y.; Tuchida, T. Improving effects of the mushroom Yamabushitake on mild cognitive impairment: A double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. Phytother. Res. 2009, 23, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contato, A.G.; Conte, C., Jr. Lion’s Mane Mushroom (Hericium erinaceus): A Neuroprotective Fungus with antioxidant, anti-Inflammatory, and antimicrobial potential-A narrative review. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryu, S.H.; Hong, S.M.; Khan, Z.; Lee, S.K.; Vishwanath, M.; Turk, A.; Yeon, S.W.; Jo, Y.H.; Lee, D.H.; Lee, J.K.; et al. Neurotrophic isoindolinones from the fruiting bodies of. Bioorg Med. Chem. Lett. 2021, 31, 127714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, P.C.; Lan, Y.J.; Chen, C.C.; Lee, L.Y.; Chen, W.P.; Wang, Y.C.; Lee, Y.H. Erinacine A attenuates glutamate transporter 1 downregulation and protects against ischemic brain injury. Life Sci. 2022, 306, 120833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.L.; Sun, H.L.; Chang, J.C.; Lin, W.Y.; Chen, P.Y.; Chen, C.C.; Lee, L.Y.; Li, C.C.; Hsieh, M.; Chen, H.W.; et al. Erinacine A-enriched Hericium erinaceus mycelium ethanol extract lessens cellular damage in cell and drosophila models of spinocerebellar ataxia Type 3 by improvement of Nrf2 activation. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, P.S.; Khairuddin, S.; Tse, A.C.K.; Hiew, L.F.; Lau, C.L.; Tipoe, G.L.; Fung, M.L.; Wong, K.H.; Lim, L.W. Hericium erinaceus potentially rescues behavioural motor deficits through ERK-CREB-PSD95 neuroprotective mechanisms in rat model of 3-acetylpyridine-induced cerebellar ataxia. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 14945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Mármol, R.; Chai, Y.J.; Conroy, J.N.; Khan, Z.; Hong, S.M.; Kim, S.B.; Gormal, R.S.; Lee, D.H.; Lee, J.K.; Coulson, E.J.; et al. Hericerin derivatives activates a pan-neurotrophic pathway in central hippocampal neurons converging to ERK1/2 signaling enhancing spatial memory. J. Neurochem. 2023, 165, 791–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.M.; Yoon, D.; Lee, M.K.; Lee, J.K.; Kim, S.Y. A Mixture of Gingko biloba leaf and Hericium erinaceus fruit extract attenuates scopolamine-induced memory impairments in Mice. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 9973678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Wang, Q.; Li, L.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, B.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, F.; Hua, C.; Huo, G.; Li, S.; et al. Neuroprotective terpenoids derived from Hericium erinaceus fruiting bodies: Isolation, structural elucidation and mechanistic insights. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.K.; Ryu, S.H.; Turk, A.; Yeon, S.W.; Jo, Y.H.; Han, Y.K.; Hwang, B.Y.; Lee, K.Y.; Lee, M.K. Characterization of alpha-glucosidase inhibitory constituents of the fruiting body of lion’s mane mushroom (Hericium erinaceus). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 262, 113197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szucko-Kociuba, I.; Trzeciak-Ryczek, A.; Kupnicka, P.; Chlubek, D. Neurotrophic and neuroprotective effects of. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 15960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Gao, Y.; Xu, D.; Konishi, T.; Gao, Q. Hericium erinaceus (Yamabushitake): A unique resource for developing functional foods and medicines. Food Funct. 2014, 5, 3055–3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, G.; Tang, L.; Xie, Y.; Xie, L. Secondary Metabolites from Hericium erinaceus and their anti-inflammatory activities. Molecules 2022, 27, 2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lysakowska, P.; Sobota, A.; Wirkijowska, A. Medicinal mushrooms: Their bioactive components, nutritional value and application in functional food production-A Review. Molecules 2023, 28, 5393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurley, L.L.; Akinfiresoye, L.; Kalejaiye, O.; Tizabi, Y. Antidepressant effects of resveratrol in an animal model of depression. Behav. Brain Res. 2014, 268, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.L.; Liu, L.; Tong, Y.; Li, Y.J.; Zhang, X.; Gao, X.J.; Yong, J.J.; Zhao, J.J.; Xiao, D.; Wen, K.S.; et al. The antidepressant effects of hesperidin on chronic unpredictable mild stress-induced mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 853, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samsuzzaman, M.; Hong, S.M.; Lee, J.H.; Park, H.; Chang, K.A.; Kim, H.B.; Park, M.G.; Eo, H.; Oh, M.S.; Kim, S.Y. Depression like-behavior and memory loss induced by methylglyoxal is associated with tryptophan depletion and oxidative stress: A new in vivo model of neurodegeneration. Biol. Res. 2024, 57, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joradon, P.; Rungsardthong, V.; Ruktanonchai, U.; Suttisintong, K.; Iempridee, T.; Thumthanaruk, B.; Vatanyoopaisarn, S.; Sumonsiri, N.; Uttapap, D. Ergosterol content and antioxidant activity of lion’s mane mushroom (Hericium erinaceus) and its induction to vitamin D2 by UVC-irradiation. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Agricultural and Biological Sciences, Shenzhen, China, 8–11 August 2022; pp. 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, S.H.; Kim, B.S.; Turk, A.; Yeon, S.W.; Lee, S.; Lee, H.H.; Ko, S.M.; Hwang, B.Y.; Lee, M.K. Effect of cultivation stages of Hericium erinaceus on the contents of major components and α-glucosidase inhibitory activity. Nat. Prod. Sci. 2023, 29, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, L.; Seixas, L.; Dias, S.; Peres, A.M.; Veloso, A.C.A.; Henriques, M. Effect of extraction method on the bioactive composition, antimicrobial activity and phytotoxicity of pomegranate by-products. Foods 2022, 11, 992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirvani, M.; Nouri, F.; Sarihi, A.; Habibi, P.; Mohammadi, M. Neuroprotective effects of dehydroepiandrosterone and in scopolamine-induced Alzheimer’s diseases-like symptoms in male rats. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2024, 82, 2853–2864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hampel, H.; Mesulam, M.M.; Cuello, A.C.; Farlow, M.R.; Giacobini, E.; Grossberg, G.T.; Khachaturian, A.S.; Vergallo, A.; Cavedo, E.; Snyder, P.J.; et al. The cholinergic system in the pathophysiology and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 2018, 141, 1917–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira-Vieira, T.H.; Guimaraes, I.M.; Silva, F.R.; Ribeiro, F.M. Alzheimer’s disease: Targeting the cholinergic system. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2016, 14, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birks, J. Cholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2006, 2006, CD005593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binder, D.K.; Scharfman, H.E. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Growth Factors 2004, 22, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Österreichische Pharmazeutische Gesellschaft. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.