Synthesis, Antimicrobial and Antiproliferative Activity of 1-Trifluoromethylphenyl-3-(4-Arylthiazol-2-Yl)Thioureas

Abstract

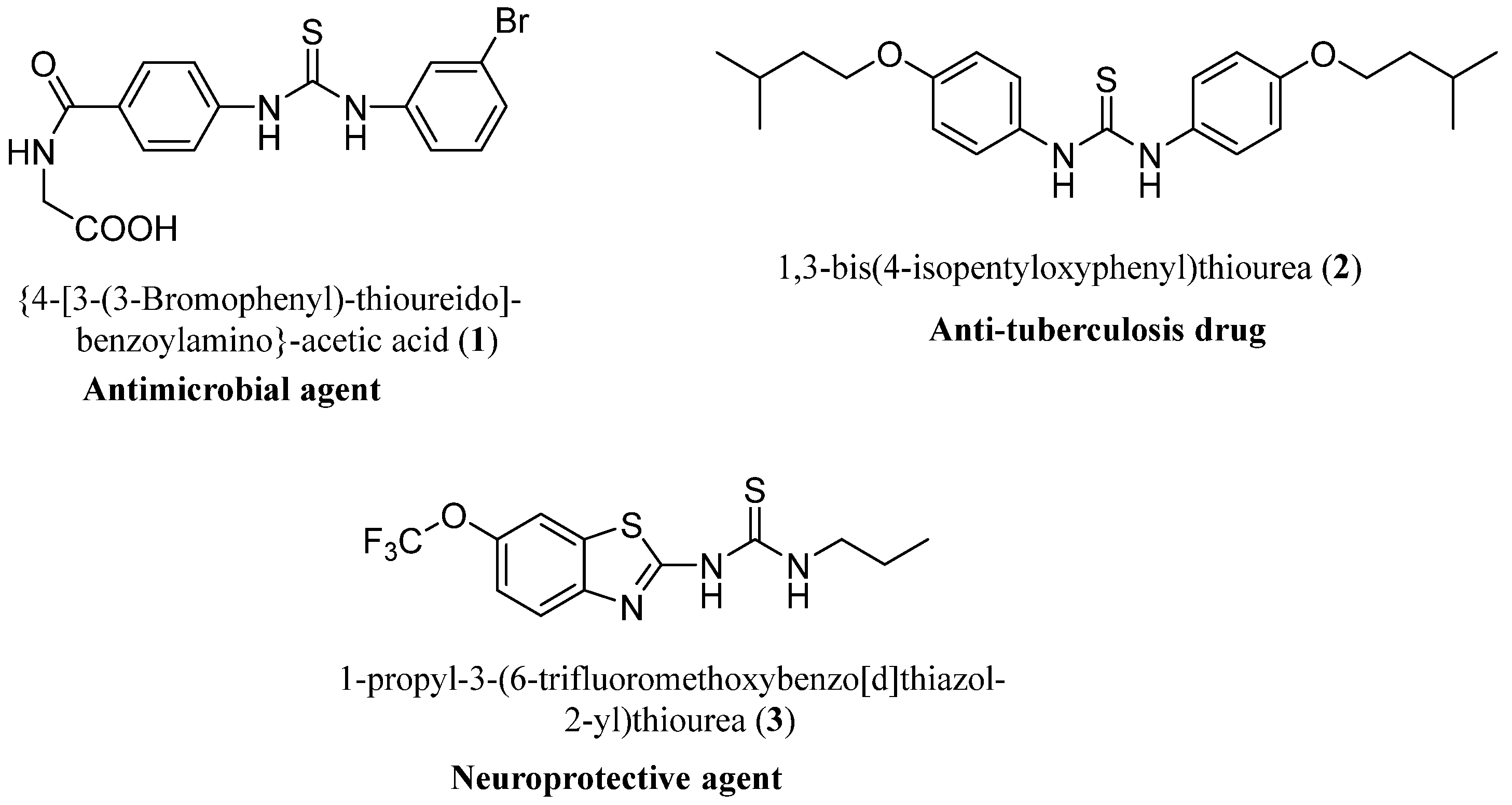

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Instruments

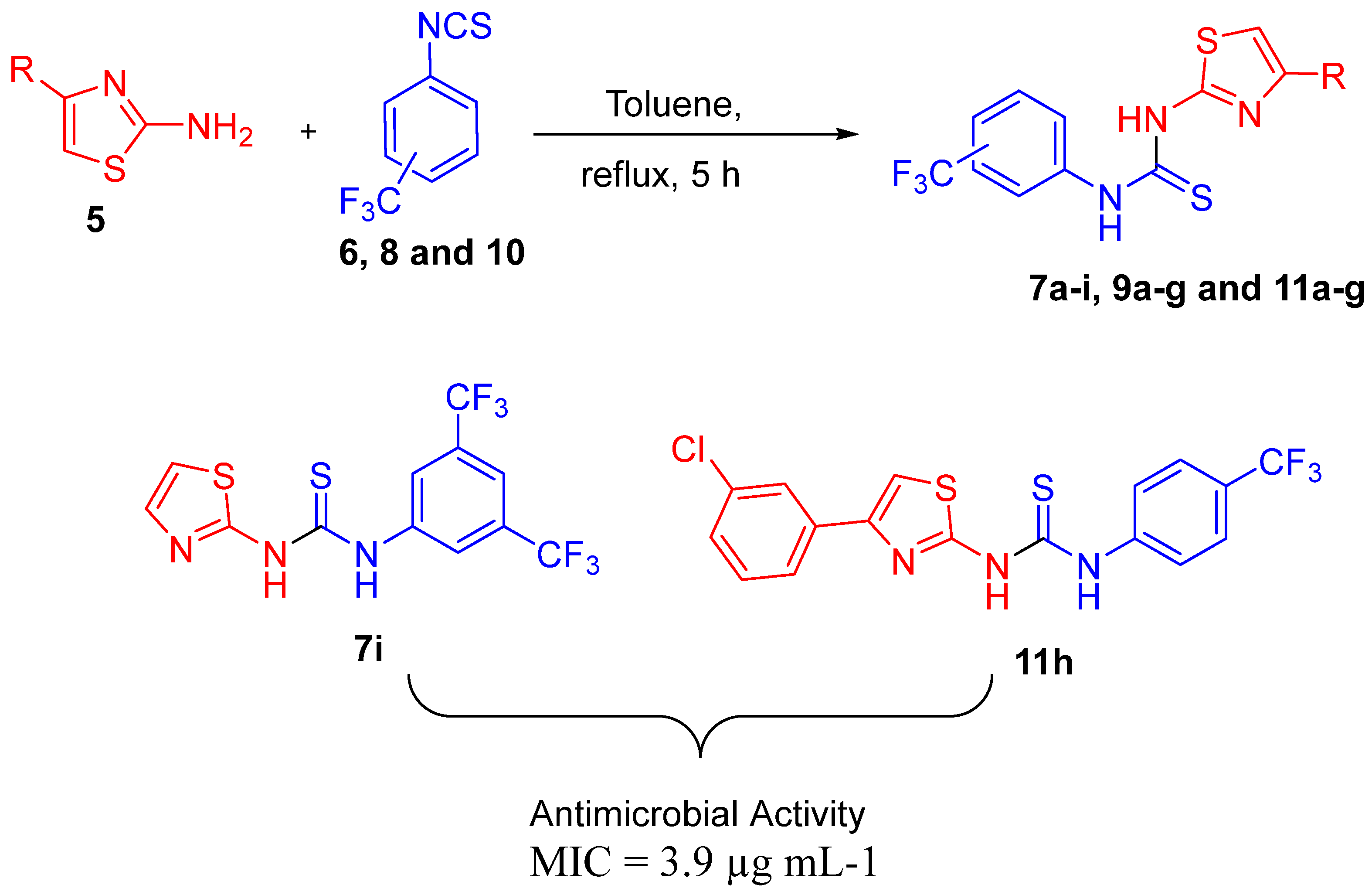

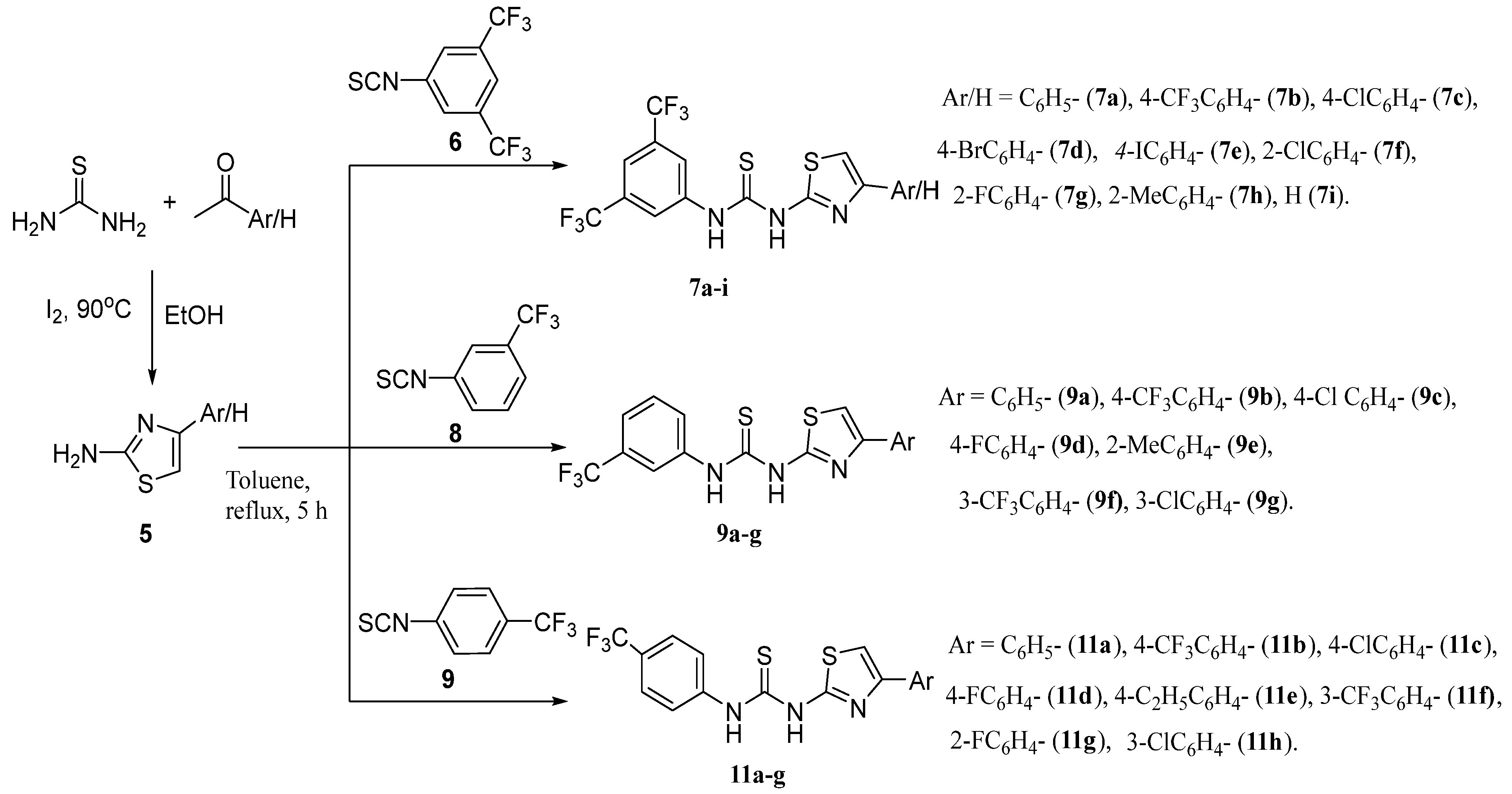

2.2. Synthesis

2.2.1. General Procedure for Synthesis of 1-(3,5-Bistrifluoromethylphenyl)-3-(4-Arylthiazol-2-Yl)Urea Derivatives (7a–i)

2.2.2. Spectral Data of Synthesized Compounds (7a–i)

2.2.3. General Procedure for the Synthesis of 1-(3-Trifluoromethylphenyl)-3-(4-(Substituted-Phenyl)Thiazol-2-Yl)thiourea (9a–g)

2.2.4. Spectral Data of Synthesized Compounds (9a–g)

2.2.5. General Procedure for the Synthesis of 1-(4-Trifluoromethylphenyl)-3-(4-(Substituted-Phenyl)Thiazol-2-Yl)Thiourea (11a–h)

2.2.6. Spectral Data of Synthesized Compounds (11a–h)

2.3. Pharmacology

2.3.1. Experiments In Vitro

2.3.2. Antimicrobial Assay

2.3.3. Antimycobacterial Assay

2.3.4. Cell Cultures, Maintenance and Anti-Proliferative Evaluation

- [(Ti − Tz)/(C − Tz)] × 100 for concentrations for which Ti >/= Tz.

- [(Ti − Tz)/Tz] × 100 for concentrations for which Ti < Tz.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Chemistry

3.2. Biology

3.2.1. Antimicrobial Activity

3.2.2. Antimycobacterial Activity

3.2.3. Anti-Proliferative Activity

3.2.4. Structure–Activity Relationship

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Boucher, H.W.; Talbot, G.H.; Bradley, J.S.; Edwards, J.E.; Gilbert, D.; Rice, L.B.; Scheld, M.; Spellberg, B.; Bartlett, J. Bad Bugs, No Drugs: No ESKAPE! An Update from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009, 48, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, M.A.; Shlaes, D. Fix the antibiotics pipeline. Nature 2011, 472, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komorowski, A.S.; Lo Carson, K.L.; Kapoor, A.K.; Smieja, M.; Loeb, M.; Mertz, D.; Bai, A.D. More Than a Decade Since the Latest CONSORT Non-inferiority Trials Extension: Do Infectious Diseases Trials Do Enough? Clin. Infect. Dis. 2024, 78, 324–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnacho-Montero, J.; Garcia-Garmendia, J.L.; Barrero-Almodovar, A.; Jimenez, F.J.; Perez-Paredes, C.; Ortiz-Leyba, C. Impact of adequate empirical antibiotic therapy on the outcome of patients admitted to the intensive care unit with sepsis. Crit. Care Med. 2003, 31, 2742–2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, D.K.; Hogan, D.A. Candida albicans Interactions with Bacteria in the Context of Human Health and Disease. PLOS Pathog. 2010, 6, e1000886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitman, S.K.; Drew, R.H.; Perfect, J.R. Addressing current medical needs in invasive fungal infection prevention and treatment with new antifungal agents, strategies and formulations. Expert Opin. Emerg. Drugs 2011, 16, 559–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinamon, T.; Gopinath, R.; Waack, U.; Needles, M.; Rubin, D.; Collyar, D.; Doernberg, S.B.; Hamasaki, S.E.T.; Holland, T.L.; Anderson, J.H.; et al. Exploration of a Potential Desirability of Outcome Ranking Endpoint for Complicated Intra-Abdominal Infections Using 9 Registrational Trials for Antibacterial Drugs. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2023, 77, 649–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. World Health Organization Report; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zumla, A.I.; Gillespie, S.H.; Hoelscher, M.; Philips, P.P.; Cole, S.T.; Abubakar, I.; McHugh, T.D.; Schito, M.; Maeurer, M.; Nunn, A.J. New antituberculosis drugs, regimens, and adjunct therapies: Needs, advances, and future prospects. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2014, 14, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Y.; Lanne, A.; Avula, S.; Salih, M.A.H.; Peng, X.; Milne, G.; Jones, G.; Ritchie, J.; Zhao, Y.; Frampton, J.; et al. Discovery of novel fluorescent amino-pyrazolines that detect and kill Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2025, 297, 117889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikiashvili, L.; Kempker, R.R.; Chakhaia, T.S.; Bablishvili, N.; Avaliani, Z.; Lomtadze, N.; Schechter, M.C.; Kipiani, M. Impact of Prior Tuberculosis Treatment with New/Companion Drugs on Clinical Outcomes in Patients Receiving Concomitant Bedaquiline and Delamanid for Multidrug- and Rifampicin-Resistant Tuberculosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2024, 78, 1043–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mac Dougall, C.; Polk, R.E. Antimicrobial Stewardship Programs in Health Care Systems. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2005, 18, 638–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mah, T.F.; O’Toole, G.A. Mechanisms of biofilm resistance to antimicrobial agents. Trends Microbiol. 2001, 9, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Lanne, A.; Peng, X.; Browne, E.; Bhatt, A.; Coltman, N.J.; Craven, P.; Cox, L.R.; Cundy, N.J.; Dale, K.; et al. Azetidines Kill Multidrug-Resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis without Detectable Resistance by Blocking Mycolate Assembly. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 2529–2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abhishek, D.K.; Afiya, A.; Afra, T.A.; Anupama, M.; Shadiya, C.K. Design, Synthesis, Characterization, Evaluation Antimicrobial Evaluation of 2—Amino Thiazole Based Lead Compound: Docking Analysis of Ortho and Meta Substituted Analogues. ChemRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottenceau, G.; Besson, T.; Gautier, V.; Rees, C.W.; Pons, A.-M. Antibacterial evaluation of novel N-Arylimino-1,2,3-dithiazoles and N-arylcyanothioformamides. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 1996, 6, 529–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testard, A.; Picot, L.; Lozach, O.; Blairvacq, M.; Meijer, L.; Piot, J.-M.; Thiéry, V.; Besson, T. Synthesis and evaluation of the antiproliferative activity of novel thiazoloquinazolinone kinases inhibitors. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2005, 20, 557–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.H.; Wan, X.Z.; Jiang, B. Syntheses and biological activities of bis(3-indolyl)thiazoles, analogues of marine bis(indole)alkaloid nortopsentins. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 1999, 9, 569–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Y.; Green, R.; Wise, D.S.; Wotring, L.L.; Townsend, L.B. Synthesis of 2,4-disubstituted thiazoles and selenazoles as potential antifilarial and antitumor agents. 2. 2-Arylamido and 2-alkylamido derivatives of 2-amino-4-(isothiocyanatomethyl)thiazole and 2-amino-4-(isothiocyanatomethyl)selenazole. J. Med. Chem. 1993, 36, 3849–3852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, P.S.; Bansal, K.K.; Sharma, A.; Sharma, D.; Deep, A. Thiazole-containing compounds as therapeutic targets for cancer therapy. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 188, 112016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreani, A.; Granaiola, M.; Leoni, A.; Locatelli, A.; Morigi, R. Synthesis and antitubercular activity of imidazo [2,1-b]thiazoles. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2001, 36, 743–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesicki, E.A.; Bailey, M.A.; Ovechkina, Y.; Early, J.V.; Alling, T.; Bowman, J.; Zuniga, E.S.; Dalai, S.; Kumar, N.; Masquelin, T.; et al. Synthesis and Evaluation of the 2-Aminothiazoles as Anti-Tubercular Agents. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0155209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Di, J.; Luo, D.; Verma, R.; Verma, S.K.; Verma, S.; Ravindar, L.; Koshle, A.; Dewangan, H.K.; Gupta, R.; et al. Thiazole—A promising scaffold for antituberculosis agents and structure-activity relationships studies. Bioorganic Chem. 2025, 154, 108035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carosati, E.; Tochowicz, A.; Marverti, G.; Guaitoli, G.; Benedetti, P.; Ferrari, S.; Stroud, R.M.; Finer-Moore, J.; Luciani, R.; Farina, D.; et al. Inhibitor of Ovarian Cancer Cells Growth by Virtual Screening: A New Thiazole Derivative Targeting Human Thymidylate Synthase. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 10272–10276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madsen, P.; Kodra, J.T.; Behrens, C.; Nishimura, E.; Jeppesen, C.B.; Pridal, L.; Andersen, B.; Knudsen, L.B.; Valcarce-Aspegren, C.; Guldbrandt, M.; et al. Human Glucagon Receptor Antagonists with Thiazole Cores. A Novel Series with Superior Pharmacokinetic Properties. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 2989–3000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iino, T.; Tsukahara, D.; Kamata, K.; Sasaki, K.; Ohyama, S.; Hosaka, H.; Hasegawa, T.; Chiba, M.; Nagata, Y.; Jun-ichi, E.; et al. Discovery of potent and orally active 3-alkoxy-5-phenoxy-N-thiazolyl benzamides as novel allosteric glucokinase activators. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2009, 17, 2733–2743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Sattar, N.E.A.; El-Naggar, A.M.; Abdel-Mottaleb, M.S.A. Novel Thiazole Derivatives of Medicinal Potential: Synthesis and Modeling. J. Chem. 2017, 2017, 4102796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štrukil, V. Mechanochemical synthesis of thioureas, ureas and guanidines. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2017, 13, 1828–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maddani, M.R.; Prabhu, K.R. A Concise Synthesis of Substituted Thiourea Derivatives in Aqueous Medium. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 2327–2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, G.S.; El-Messery, S.M.; Al-Omary, F.A.; Al-Rashood, S.T.; Shabayek, M.I.; Abulfadl, Y.S.; Habib, E.E.; El-Hallouty, S.M.; Fayad, W.; Mohamed, K.M.; et al. Nonclassical antifolates, part 4. 5-(2-Aminothiazol-4-yl)-4-phenyl-4H-1,2,4-triazole-3-thiols as a new class of DHFR inhibitors: Synthesis, biological evaluation and molecular modeling study. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 66, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, M.; Rahim, F.; Khan, I.U.; Uddin, N.; Farooq, R.K.; Wadood, A.; Rehman, A.U.; Khan, K.M. Synthesis of Thiazole-Based-Thiourea Analogs: As Anticancer, Antiglycation and Antioxidant Agents, Structure Activity Relationship Analysis and Docking Study. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2023, 41, 12077–12092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Gaby, M.S.A.; Micky, J.A.; Taha, N.M.; El-Sharief, M.A.M. Antimicrobial Activity of Some Novel Thiourea, Hydrazine, Fused Pyrimidine and 2-(4-Substituted)anilinobenzoazole Derivatives Containing Sulfonamido Moieties. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 2002, 49, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eweis, M.; Elkholy, S.S.; Elsabee, M.Z. Antifungal efficacy of chitosan and its thiourea derivatives upon the growth of some sugar-beet pathogens. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2006, 38, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhayaya, R.S.; Kulkarni, G.M.; Vasireddy, N.R.; Vandavasi, J.K.; Dixit, S.S.; Sharma, V.; Chattopadhyaya, J. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of novel triazole, urea and thiourea derivatives of quinoline against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2009, 17, 4681–4692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahajan, A.; Yeh, S.; Nell, M.; Van Rensburg, C.E.J.; Chibale, K. Synthesis of new 7-chloro quinolinyl thioureas and their biological investigation as potential antimalarial and anticancer agents. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2007, 17, 5683–5685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faidallah, H.M.; Khan, K.; Asir, A. Synthesis and biological evaluation of new 3-trifluoromethylpyrazolesulfonyl-urea and thiourea derivatives as antidiabetic and antimicrobial agents. J. Fluor. Chem. 2011, 132, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, B.; Bender, P.E.; Bowman, H.; Helt, A.; McLean, R.; Jen, T. Amidines. 3. Thioureas possessing antihypertensive activity. J. Med. Chem. 1972, 15, 1024–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallur, G.; Jimeno, A.; Dalrymple, S.; Zhu, T.; Jung, M.K.; Hidalgo, M.; Isaacs, J.T.; Sukumar, S.; Hamel, E.; Khan, S.R. Benzoylphenylurea Sulfur Analogues with Potent Antitumor Activity. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 2357–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manjula, S.N.; Noolvi, N.M.; Parihar, K.V.; Reddy, S.A.M.; Ramani, V.; Gadad, A.K.; Sing, G.; Kutty, N.G.; Rao, C.M. Synthesis and antitumor activity of optically active thiourea and their 2-aminobenzothiazole derivatives: A novel class of anticancer agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 44, 2923–2929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, K.M.; Naz, F.; Taha, M.; Khan, A.; Perveen, S.; Choudhary, M.I.; Voelter, W. Synthesis and in vitro urease inhibitory activity of N,N′-disubstituted thioureas. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 74, 314–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.G.; Kim, H.J.; Yang, C.H. Thioureas differentially induce rat hepatic microsomal epoxide hydrolase and rGSTA2 irrespective of their oxygen radical scavenging effect: Effects on toxicant-induced liver injury. Chem. Biol. Interact. 1999, 117, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefanska, J.; Nowicka, G.; Struga, M.; Szulczyk, D.; Koziol, A.E.; Augustynowicz-Kopec, E.; Napiorkowska, A.; Bielenica, A.; Filipowski, W.; Filipowska, A.; et al. Antimicrobial and Anti-biofilm Activity of Thiourea Derivatives Incorporating a 2-Aminothiazole Scaffold. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2015, 63, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashem, H.E.; Amr, A.E.; Azmy, E.M. Synthesis, Antimicrobial Activity and Molecular Docking of Novel Thiourea Derivatives Tagged with Thiadiazole, Imidazole and Triazine Moieties as Potential DNA Gyrase and Topoisomerase IV Inhibitors. Molecules 2020, 25, 2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanh, N.D.; Lan, P.H.; Hai, D.S.; Anh, H.H.; Kim Giang, N.T.; Kim Van, H.T.; Toan, V.N.; Triad, N.M.; Toan, D.N. Thiourea derivatives containing 4-arylthiazoles and D-glucose moiety: Design, synthesis, antimicrobial activity evaluation, and molecular docking/dynamics simulations. RSC Med. Chem. 2023, 14, 1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppireddi, S.; Reddy Komsani, J.; Avula, S.; Pombala, S.; Vasamsetti, S.; Kotamraju, S.; Yadla, R. Novel 2-(2,4-dioxo-1,3-thiazolidin-5-yl)acetamides as antioxidant and/or antiinflammatory compounds. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 66, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppireddi, S.; Chilaka, D.R.K.; Avula, S.; Komsani, J.R.; Kotamraju, S.; Yadla, R. Synthesis and anticancer evaluation of 3-aryl-6-phenylimidazo [2,1-b]thiazoles. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2014, 24, 5428–5431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amsterdam, D. Antibiotics in Laboratory Medicine, 4th ed.; Williams, Wilkins, Baltimore: Hagerstown, MD, USA, 1996; p. 52. [Google Scholar]

- McGaw, L.J.; Lall, N.; Hlokwe, T.M.; Michel, A.L.; Meyer, J.J.; Eloff, J.N. Purified Compounds and Extracts from Euclea Species with Antimycobacterial Activity against Mycobacterium bovis and Fast-Growing Mycobacteria. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2008, 31, 1429–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaal, A.; Rao, M.P.; Das, P.; Swapna, P.; Polepalli, S.; Nimbarte, V.D.; Mullagiri, K.; Kovvuri, J.; Jain, N. Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Imidazo[2,1-b][1,3,4]thiadiazole-Linked Oxindoles as Potent Tubulin Polymerization Inhibitors. ChemMedChem 2014, 9, 1463–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Compound | M. luteus b | S. aureus b | S. aureus1 b | B. subtilis b | E. coli c | P. aeruginosa c | K. planticola c | C. albicans d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7e | 62.5 | NA | 31.2 | 62.5 | NA | NA | 31.2 | NA |

| 7i | 3.9 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 15.6 | 31.2 | 15.6 | 15.6 | 7.8 |

| 9a | 7.8 | 3.9 | 15.6 | 7.8 | 31.2 | 15.6 | 15.6 | NA |

| 9g | 62.5 | NA | NA | 31.2 | NA | 31.2 | 62.5 | NA |

| 11b | 7.8 | 7.8 | 15.6 | 15.6 | 15.6 | 15.6 | 31.2 | NA |

| 11e | 15.6 | 3.9 | 31.2 | 15.6 | 15.6 | 15.6 | 31.2 | 15.6 |

| 11h | 3.9 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 15.6 | 7.8 | 15.6 | 15.6 | 7.8 |

| Ciprofloxacin e | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | NT |

| Micanazole e | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | 7.8 |

| Compound | Mycobacterium smegmatis (IC50 µg mL−1) a |

|---|---|

| 9e | 118.42 |

| 9f | 241.20 |

| 9g | 71.15 |

| 11f | 110.83 |

| 11g | 75.83 |

| 11h | 191.68 |

| Kanamycin b | 35.0 |

| Compound | IC50 (µM) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A549 | HeLa | IMR32 | MCF-7 | HCT116 | DU145 | |

| 7a | 24.7 ± 1.6 | 39.9 ± 2.7 | 42.5 ± 2.4 | 37.1 ± 2.1 | 32.3 ± 2.1 | 39.8 ± 1.1 |

| 7b | 23.7 ± 8.8 | 45.3 ± 2.4 | 47.4 ± 6.8 | 40.6 ± 4.1 | 34.5 ± 1.6 | 44.0 ± 2.4 |

| 7c | 24.9 ± 1.2 | 30.7 ± 2.6 | 43.1 ± 3.6 | 23.2 ± 3.7 | 27.8 ± 1.9 | 33.2 ± 2.0 |

| 7d | 24.2 ± 1.0 | 25.9 ± 3.2 | 47.1 ± 5.3 | 24.3 ± 4.2 | 25.1 ± 2.1 | 35.7 ± 2.3 |

| 7e | 24.4 ± 1.2 | 25.1 ± 3.0 | 51.0 ± 8.4 | 24.6 ± 4.5 | 24.7 ± 2.1 | 37.8 ± 2.6 |

| 7f | 23.5 ± 7.9 | 25.1 ± 3.2 | 49.0 ± 5.6 | 24.3 ± 4.3 | 24.3 ± 2.0 | 36.7 ± 2.4 |

| 7g | 24.5 ± 8.9 | 26.2 ± 3.0 | 48.2 ± 5.9 | 26.7 ± 4.2 | 25.4 ± 1.9 | 37.7 ± 2.4 |

| 7h | 23.9 ± 8.6 | 26.0 ± 3.0 | 49.6 ± 6.0 | 25.3 ± 4.4 | 24.9 ± 1.9 | 37.5 ± 2.5 |

| 7i | 24.9 ± 1.0 | 29.3 ± 2.7 | 43.0 ± 2.4 | 23.2 ± 3.7 | 27.1 ± 1.9 | 33.1 ± 1.9 |

| 9a | 56.9 ± 2.6 | NA | 41.1 ± 2.3 | 67.7 ± 8.8 | 83.8 ± 1.4 | 54.4 ± 5.6 |

| 9b | 50.2 ± 1.1 | 51.9 ± 1.3 | 39.7 ± 9.0 | 43.8 ± 1.5 | 51.0 ± 7.2 | 41.7 ± 1.2 |

| 9c | 57.4 ± 5.8 | NA | 40.0 ± 2.5 | NA | 81.5 ± 7.9 | 71.3 ± 4.5 |

| 9d | 53.9 ± 2.6 | 55.3 ± 1.4 | 39.2 ± 1.1 | 83.8 ± 1.5 | 54.6 ± 1.4 | 61.5 ± 8.3 |

| 9e | 25.5 ± 2.8 | 31.2 ± 3.4 | 40.9 ± 5.5 | NA | 28.4 ± 3.1 | 72.1 ± 2.5 |

| 9f | 27.2 ± 2.5 | 25.3 ± 3.3 | 40.3 ± 9.5 | 70.0 ± 4.3 | NA | NA |

| 9g | 32.0 ± 2.3 | NA | 44.6 ± 1.1 | 52.7 ± 1.2 | NA | 48.6 ± 6.5 |

| 11a | 29.0 ± 1.9 | 31.2 ± 2.8 | 39.8 ± 2.8 | 35.9 ± 3.2 | 30.1 ± 2.3 | 37.8 ± 1.7 |

| 11b | 41.7 ± 1.1 | 44.2 ± 2.1 | 48.2 ± 2.0 | 38.7 ± 2.4 | 42.9 ± 1.6 | 43.4 ± 2.2 |

| 11c | 29.4 ± 4.7 | 48.9 ± 2.4 | 45.6 ± 1.6 | 25.9 ± 3.2 | 39.2 ± 3.6 | 35.7 ± 2.4 |

| 11d | 69.6 ± 5.5 | 45.5 ± 1.6 | 38.8 ± 5.2 | 59.5 ± 1.2 | 57.6 ± 1.0 | 49.1 ± 8.7 |

| 11e | 26.7 ± 2.2 | 48.5 ± 1.9 | NA | 44.4 ± 2.5 | 37.6 ± 2.0 | NA |

| 11f | 27.2 ± 1.7 | 55.1 ± 3.3 | 44.9 ± 1.8 | 34.0 ± 3.1 | 41.1 ± 2.5 | 39.5 ± 2.4 |

| 11g | 34.6 ± 2.6 | 17.2 ± 1.5 | NA | 84.7 ± 8.8 | NA | NA |

| 11h | 30.1 ± 2.7 | 32.4 ± 3.2 | 24.8 ± 1.5 | 28.0 ± 4.0 | 31.3 ± 2.9 | 26.4 ± 2.7 |

| Doxorubicin | 1.92 ± 0.03 | 2.0 ± 0.02 | 2.39 ± 0.1 | 1.96 ± 0.14 | 3.1 ± 0.04 | 2.1 ± 0.06 |

| Comb | 2.6 ± 0.06 | 1.49 ± 0.01 | 2.1 ± 0.05 | 2.54 ± 0.2 | 2.32 ± 0.1 | 1.24 ± 0.03 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Österreichische Pharmazeutische Gesellschaft. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Avula, S.; Koppireddi, S.; Tortorella, M.D.; Neagoie, C. Synthesis, Antimicrobial and Antiproliferative Activity of 1-Trifluoromethylphenyl-3-(4-Arylthiazol-2-Yl)Thioureas. Sci. Pharm. 2026, 94, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/scipharm94010011

Avula S, Koppireddi S, Tortorella MD, Neagoie C. Synthesis, Antimicrobial and Antiproliferative Activity of 1-Trifluoromethylphenyl-3-(4-Arylthiazol-2-Yl)Thioureas. Scientia Pharmaceutica. 2026; 94(1):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/scipharm94010011

Chicago/Turabian StyleAvula, Sreenivas, Satish Koppireddi, Micky D. Tortorella, and Cleopatra Neagoie. 2026. "Synthesis, Antimicrobial and Antiproliferative Activity of 1-Trifluoromethylphenyl-3-(4-Arylthiazol-2-Yl)Thioureas" Scientia Pharmaceutica 94, no. 1: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/scipharm94010011

APA StyleAvula, S., Koppireddi, S., Tortorella, M. D., & Neagoie, C. (2026). Synthesis, Antimicrobial and Antiproliferative Activity of 1-Trifluoromethylphenyl-3-(4-Arylthiazol-2-Yl)Thioureas. Scientia Pharmaceutica, 94(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/scipharm94010011