Abstract

Modern passport systems face significant challenges in secure data sharing, real-time verification, and user-controlled authorization, particularly in cross-border scenarios. Existing digital passport solutions, often built on permissioned blockchains, suffer from limited transparency, scalability, and high operational costs. This paper proposes a decentralized passport management system based on an Ethereum Layer 2 architecture that combines global governance with high-throughput and cost-efficient passport operations. The system adopts a hybrid design in which a Global Passport Registry smart contract is deployed on the Ethereum mainnet for cross-country coordination, while passport issuance, access control, and identity management are handled on Layer 2 networks through country-operated Passport Managers and user-specific Personal Passport smart contracts. Extensive performance evaluations show that Ethereum Layer 1 throughput saturates at approximately 40–50 transactions per second (TPS), whereas the proposed Layer 2 deployment consistently exceeds 150 TPS and reaches up to 300 TPS under higher-performance environments, significantly surpassing the estimated system requirement of 70 TPS. These improvements result in faster response times, reduced congestion, and substantially lower transaction costs, demonstrating that public Ethereum Layer 2 infrastructures can effectively support a scalable, self-sovereign, privacy-preserving, and globally verifiable digital passport system suitable for real-world deployment.

1. Introduction

In the age of global mobility, identity verification plays a critical role in international travel, immigration control, and border security. However, current passport systems still rely heavily on centralized, country-specific infrastructures, which often lack interoperability and transparency across borders. The inability to dynamically authorize and verify passport data on demand leads to operational inefficiencies, prolonged inspection procedures, and increased risks to both user privacy and national security [1].

Existing digital passport solutions [2], particularly those built on permissioned blockchains such as Hyperledger [3], have made progress in digitizing identity records and enabling limited cross-border authentication. Nevertheless, these systems inherently lack openness and global verifiability due to closed governance structures and restricted access models. Furthermore, centralized certificate issuance mechanisms commonly adopted in such architectures constrain user autonomy, preventing individuals from fully controlling access to their personal data. These limitations are especially problematic in high-volume, real-time scenarios, such as international passport issuance and visa application processes.

To address these challenges, this research proposes a decentralized passport management system based on a hybrid Ethereum [4] blockchain architecture. Ethereum mainnet is used to host a Global Passport Registry smart contract, which governs the participation of sovereign entities through decentralized autonomous organization (DAO)-based voting. Each participating country can deploy its own Passport Manager contract on an Ethereum Layer 2 network [5], enabling scalable passport issuance, validation, and revocation. Upon approval, each traveler is assigned a Personal Passport smart contract that serves as an on-chain identity credential under their full control. Access permissions are managed through role-based access control (RBAC), allowing users to grant or revoke access to specific data fields such as name, nationality, and passport ID.

Several technical challenges are addressed in the system design. First, Ethereum Layer 2 technology is adopted to meet the scalability and cost-efficiency requirements of real-world passport systems, particularly for countries with large populations. Second, Ethereum Request for Comments 165 (ERC-165) [6] interface detection is employed to ensure interoperability among Passport Manager contracts worldwide. Third, a challenge–response mechanism based on digital signatures is implemented to prevent unauthorized data access.

The primary objective of this research is to develop a decentralized passport management system that empowers users to control access to their personal data and ensures that no information is shared without their consent. The system leverages Ethereum smart contracts to provide verifiable and tamper-resistant on-chain access control, while off-chain datasets are managed securely by trusted local services. Although potential attackers may target off-chain data, the immutable nature of on-chain contracts prevents unauthorized modification or forgery of critical records. Insider threats remain a challenge for off-chain storage, but mitigating such risks is outside the scope of this study. By focusing on user-controlled data sharing, privacy protection, and verifiable access, this work establishes a foundation for secure and scalable decentralized identity applications.

The main contributions of this thesis are summarized as follows:

- A decentralized passport architecture is proposed that integrates Ethereum Layer 1 for governance and Layer 2 for high-throughput passport operations.

- A working prototype is developed to demonstrate efficient handling of high-volume passport issuance and access control using Ethereum Layer 2, validating its feasibility in large-scale, real-world scenarios.

- Through throughput analysis and benchmarking on local Layer 2 environments, this study verifies that the proposed architecture can meet estimated performance requirements, establishing a practical foundation for decentralized identity applications.

The remainder of this thesis is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews background and related work. Section 3 presents the system architecture. Section 4 describes the implementation details. Section 5 reports the performance evaluation results. Finally, Section 6 concludes the thesis and discusses future research directions.

2. Background and RelatedWork

2.1. Background

In this paragraph, we discuss three topics: blockchain infrastructure and smart contracts; digital identity and access control; and existing passport systems and standards.

2.1.1. Blockchain Infrastructure and Smart Contract

Blockchain technology provides a decentralized, tamper-resistant, and transparent ledger that has significantly influenced the development of digital identity and authentication mechanisms. Based on access control and consensus models, blockchain platforms are generally classified into three categories: public, consortium, and private blockchains.

- Public blockchains, such as Ethereum [4] and Bitcoin [7], allow anyone to participate in the network, validate transactions, and deploy smart contracts. These platforms offer a high degree of decentralization and verifiability, making them suitable for scenarios that require trust among globally distributed and independent parties. All transactions and smart contract states are publicly accessible, ensuring transparency and strengthening data integrity.

- Consortium blockchains, such as Hyperledger Fabric [3], are operated by a group of pre-approved participants. This architecture provides greater control over governance and performance, which can be advantageous in inter-institutional settings. However, because participation is restricted to selected members, data transparency and global verifiability are inherently limited, making this model less suitable for cross-border identity verification scenarios.

- Private blockchains are fully controlled by a single authority, which determines network participation and data access. Although this model provides high performance and low latency, it lacks transparency, decentralization, and global verifiability. Consequently, private blockchains are unsuitable for cross-border identity verification and user-centric passport systems.

Considering the requirements for global accessibility, decentralized trust, and compatibility with open standards, the proposed system is built on Ethereum, a public blockchain with a mature smart contract ecosystem. Ethereum supports transparent execution, strong decentralization, and extensive developer tooling, making it a robust foundation for decentralized passport management.

Smart contracts are self-executing programs deployed on the blockchain that automatically enforce predefined logic when specific conditions are met. Once deployed, they are immutable and produce consistent results across all network nodes. In this system, smart contracts manage critical operations such as passport application, issuance, and access control, eliminating reliance on centralized authorities and ensuring transparent and reliable identity management.

To address Ethereum Layer 1 limitations in transaction throughput and cost, the system adopts Layer 2 scaling solutions, which execute most transactions off-chain while inheriting Layer 1 security guarantees. Two widely adopted approaches are Optimistic Rollups [8] and Zero-Knowledge Rollups (zk-Rollups) [9]. Optimistic Rollups assume transaction validity unless challenged, whereas zk-Rollups rely on cryptographic proofs to verify the correctness of transaction batches.

By deploying high-frequency operations, such as passport issuance and access permission updates, on Layer 2 networks, the system significantly increases scalability while substantially reducing transaction costs, often to only a few cents per interaction. This design enables the system to support high-demand use cases, including passport management for large populations in countries such as India or the United States, without compromising on-chain verifiability or security.

2.1.2. Digital Identity and Access Control

In digital identity systems, access control and user autonomy are fundamental design considerations. Traditional identity frameworks typically rely on centralized issuers, such as governments or large corporations, to issue, manage, and validate credentials. While effective in closed environments, this centralized model limits user control and introduces single points of failure. In response, the concept of Self-Sovereign Identity (SSI) [10] has emerged to empower individuals with full ownership of their digital identities.

The core principle of SSI is that users should be able to create, manage, and control their identity data without reliance on centralized authorities. Rather than acting as passive holders of credentials, individuals actively manage access permissions and data disclosures. In this model, identity verification is achieved through cryptographic proofs, and access to personal information is governed by user-defined policies.

To support interoperable and verifiable digital identities in decentralized environments, standards such as Decentralized Identifiers (DIDs) and Verifiable Credentials (VCs) have been proposed by the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C). DIDs are globally unique identifiers that are registered on-chain or anchored off-chain and controlled by the identity owner. VCs are cryptographically signed documents containing claims about an individual’s attributes, such as name, nationality, or date of birth. Together, DIDs and VCs form the foundation for cross-platform and cross-domain identity verification.

To enforce fine-grained access control over sensitive identity data, the proposed system adopts Role-Based Access Control (RBAC) within each Personal Passport smart contract. In RBAC, permissions are associated with roles rather than individual users. Specific roles, such as NAME_VIEWER or NATIONALITY_VIEWER, are defined as hashed constants and assigned to trusted entities, including border control authorities. Access rights are granted or revoked by the passport holder through on-chain transactions.

RBAC provides several advantages in this context. First, it simplifies permission management by grouping related privileges under predefined roles. Second, it reduces the risk of overexposure [11], as users can selectively authorize only the minimum set of permissions required for a given use case. Third, it aligns with the principle of least privilege, a widely recognized security best practice that is particularly important when managing identity data on a public blockchain. This approach enables dynamic, transparent, and user-centric access policies, which are essential for building a secure and scalable global identity system.

2.1.3. Existing Passport Systems and Standards

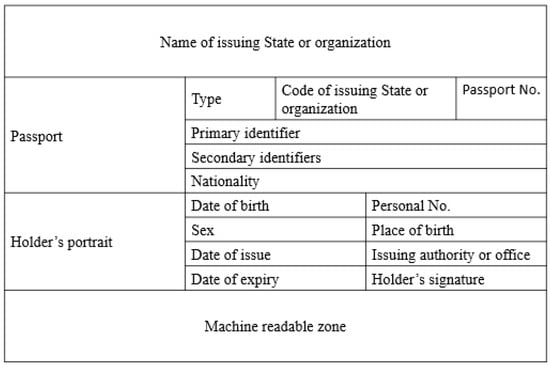

Modern international travel relies heavily on standardized machine-readable passports (MRPs), governed by guidelines set forth by the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) [12]. These standards ensure that passport documents can be read and verified consistently and interoperably across borders.

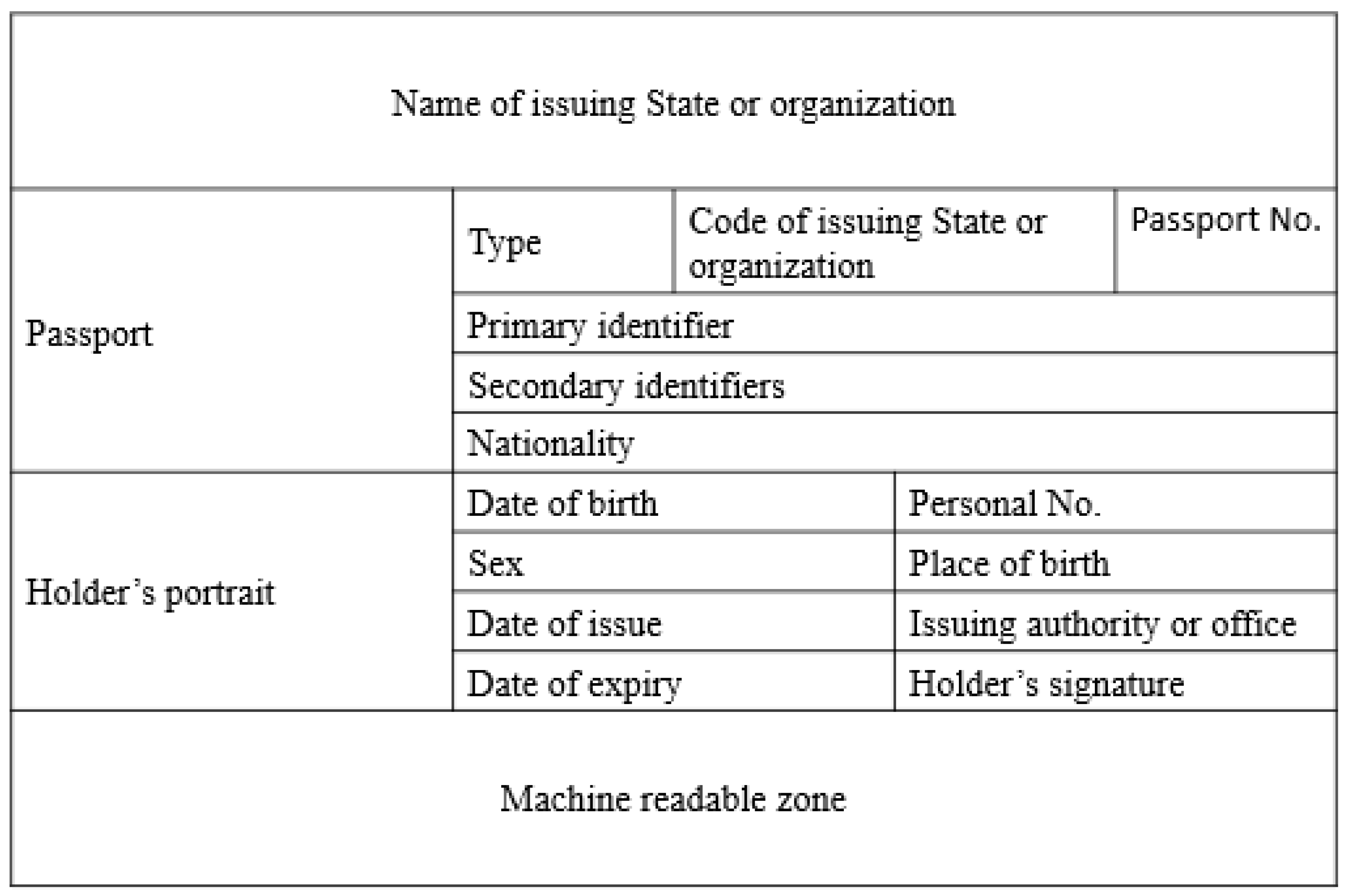

Figure 1 illustrates the structure of a typical MRP data page, which includes fields such as name, nationality, date of birth, passport number, and issuance/expiry dates [13]. In modern passports, these data elements are digitally encoded and embedded in a chip, with signature verification performed based on ICAO-defined root authorities.

Figure 1.

Structure of Machine Readable Passport (MRP) data page.

Despite these advances, the current passport verification process remains largely centralized and lacks real-time flexibility. Most countries depend on internal databases and bilateral or consular agreements to validate passport information, often requiring pre-approved cooperation between authorities. This centralized approach results in several limitations:

- Delayed verification: Foreign authorities cannot universally verify passport data in real time unless prior bilateral data sharing is established.

- Limited granular access control: Travelers cannot selectively disclose only specific portions of their passport information (e.g., name and nationality) to verifiers.

References [14,15] illustrate differences in passport application requirements between Taiwan and the United States. In [14], the Taiwan passport application requires applicants to submit two biometric photos compliant with ICAO standards, a National Identification Card, and either a Household Certificate or a Household Registration Transcript. Applicants must also present original identification documents of the applicant, legal guardian, and accompanying adult for in-person verification.

In contrast, reference [15] shows that the U.S. passport application process requires applicants to complete Form DS-11, provide proof of U.S. citizenship, present an acceptable photo ID, submit photocopies of both citizenship documents and photo identification, and pay the passport fee. The application must be completed in person at an authorized passport acceptance facility. While both systems require citizenship evidence and identity verification, the procedures in both countries remain highly reliant on paper forms and face-to-face validation.

Furthermore, verification of travel eligibility is closely tied to visa systems. Different countries implement varying fee structures and maximum durations depending on visa types, as exemplified in Table 1 [16], which summarizes standard UK visitor visa options. These systems also lack cross-border integration, forcing each authority to independently verify identity and eligibility.

Table 1.

Visa fee comparison for different UK visitor visa types.

These limitations highlight the need for decentralized passport solutions that give users ownership of their identity data and allow flexible access control without reliance on centralized databases.

2.2. Related Work

Prior research has explored the application of blockchain technology to passport and visa management as a means to address the limitations of traditional, centralized systems. A representative work, Passport, VISA and Immigration Management Using Blockchain [6], proposes a framework based on Hyperledger Fabric for identity verification and visa issuance. The system introduces on-chain data structures for passports and visas and utilizes chaincodes to enforce cross-domain authorization and access control. However, as a consortium blockchain, Hyperledger inherently limits public verifiability and global composability, and its reliance on permissioned participation restricts the openness and extensibility required for truly global systems.

Separately, The Study of Recent Technologies Used in E-passport System [17] surveys modern e-passport architectures, highlighting their dependence on centralized infrastructures, particularly the ICAO Public Key Directory (PKD) and Public Key Infrastructure (PKI) model [12], for authentication and verification. While these systems provide digital security, they lack flexibility in dynamic authorization and do not support real-time, user-controlled access delegation across borders.

In contrast, this thesis introduces a decentralized passport management system built on Ethereum Layer 2. By preserving global verifiability through Layer 1 registration while enabling high-throughput, low-cost operations on Layer 2, the system addresses both the rigidity of traditional frameworks and the limited interoperability of existing blockchain proposals. Each user is assigned a personal smart contract under a self-sovereign identity model, which allows them to manage access permissions dynamically. This design offers modularity, transparency, and scalability in a globally decentralized setting.

While many blockchain-based identity systems, such as those built on Hyperledger Fabric, emphasize permissioned trust and private data control, they often compromise global accessibility and decentralization. In contrast, the proposed Ethereum Layer 2 solution combines the openness of public chains with the performance advantages of rollup technologies. Table 2 summarizes the core differences between these two approaches in the context of digital passport systems. Ethereum Layer 2 networks support user-owned smart contracts, composability with open-source identity frameworks (e.g., zero-knowledge Know Your Customer protocols, ERC standards), and reduced operational costs through batching and compression. These features make Layer 2 networks more suitable for high-volume, cross-border identity applications where sovereignty, verifiability, and interoperability are critical.

Table 2.

Ethereum Layer 2 Public Chain vs. Consortium Blockchain.

Research Motivation

Since its inception in 2008 with Bitcoin, blockchain has evolved from a concept for digital cash into a platform for distributed applications. Bitcoin’s public, permissionless design demonstrated the potential of a trustless ledger but also revealed inherent limitations: low transaction throughput (~7 TPS), high fees during network congestion, and settlement times on the order of minutes. Ethereum, introduced in 2015, extended this model by enabling smart contracts, catalyzing a wave of decentralized applications (DApps) in finance, supply chain, and identity management. Despite the innovation enabled by Layer 1 public networks, enterprises deploying blockchain in production consistently face three core challenges: insufficient throughput for business-scale demand, variable and often high transaction costs, and latency that negatively impacts user experience.

To address these shortcomings, alternative architectures have emerged. Consortium (permissioned) blockchains such as Hyperledger Fabric trade some decentralization for improved performance, achieving higher transaction rates and zero fees by restricting participation to known nodes. Private blockchains operate under similar principles, typically within a single organization to maintain control over governance and data privacy. Meanwhile, Layer 2 solutions on public chains—including state channels, sidechains, and rollups—preserve Layer 1 security while dramatically improving throughput and reducing costs.

Several practical factors make public blockchains, particularly Ethereum, suitable for the proposed system. First, the Ethereum ecosystem has established standards for DApps, including widely adopted token and contract specifications (e.g., ERC standards), mature open-source frameworks such as OpenZeppelin, and developer- and user-friendly wallets and node infrastructures. This foundation enables passport management contracts across countries to interoperate without building new cross-border infrastructure. Second, all smart contracts and transactions on a public blockchain are fully transparent and verifiable by any third-party node. In contrast, consortium chains require new participants to obtain permission before accessing verification data, increasing trust requirements between sovereign entities. Third, public blockchains offer higher security because the cost of attacking the network is substantially greater than compromising a consortium chain. Finally, the Ethereum ecosystem provides widely familiar tools and services, reducing the learning curve and operational overhead for global deployment.

In the context of cross-border passport management, this research evaluates three options: high-security but low-throughput public Layer 1, high-performance but less decentralized consortium chains, and hybrid Layer 2 solutions that combine the advantages of both. The motivation of this research is to deploy a cross-border passport application on a public blockchain and demonstrate, through performance analysis, that an appropriate Layer 2 design can achieve the throughput necessary for real-world deployment.

3. System Design

In designing a blockchain-based system for global passport management, two architectural approaches were considered: a consortium blockchain (e.g., Hyperledger Fabric) or a public blockchain with Layer 2 scalability solutions. Consortium blockchains provide better control, predictable performance, and privacy by restricting participation to trusted members. This model is suitable for closed environments with predetermined governance but sacrifices openness and global verifiability, making it less ideal for international scenarios involving multiple sovereign entities.

In contrast, public blockchains with Layer 2 integration offer open verification and greater decentralization. Layer 2 networks, such as Optimistic [12] and zk-rollups [13], inherit the security of Ethereum Layer 1 while significantly reducing transaction costs and increasing throughput. Although this approach introduces additional complexity in data synchronization and latency, it supports interoperability, transparency, and scalability across multiple countries. Based on these considerations, the proposed system adopts a hybrid architecture: Ethereum Layer 1 manages the global registry and governance, while Layer 2 handles high-volume passport operations.

3.1. Architecture Overview

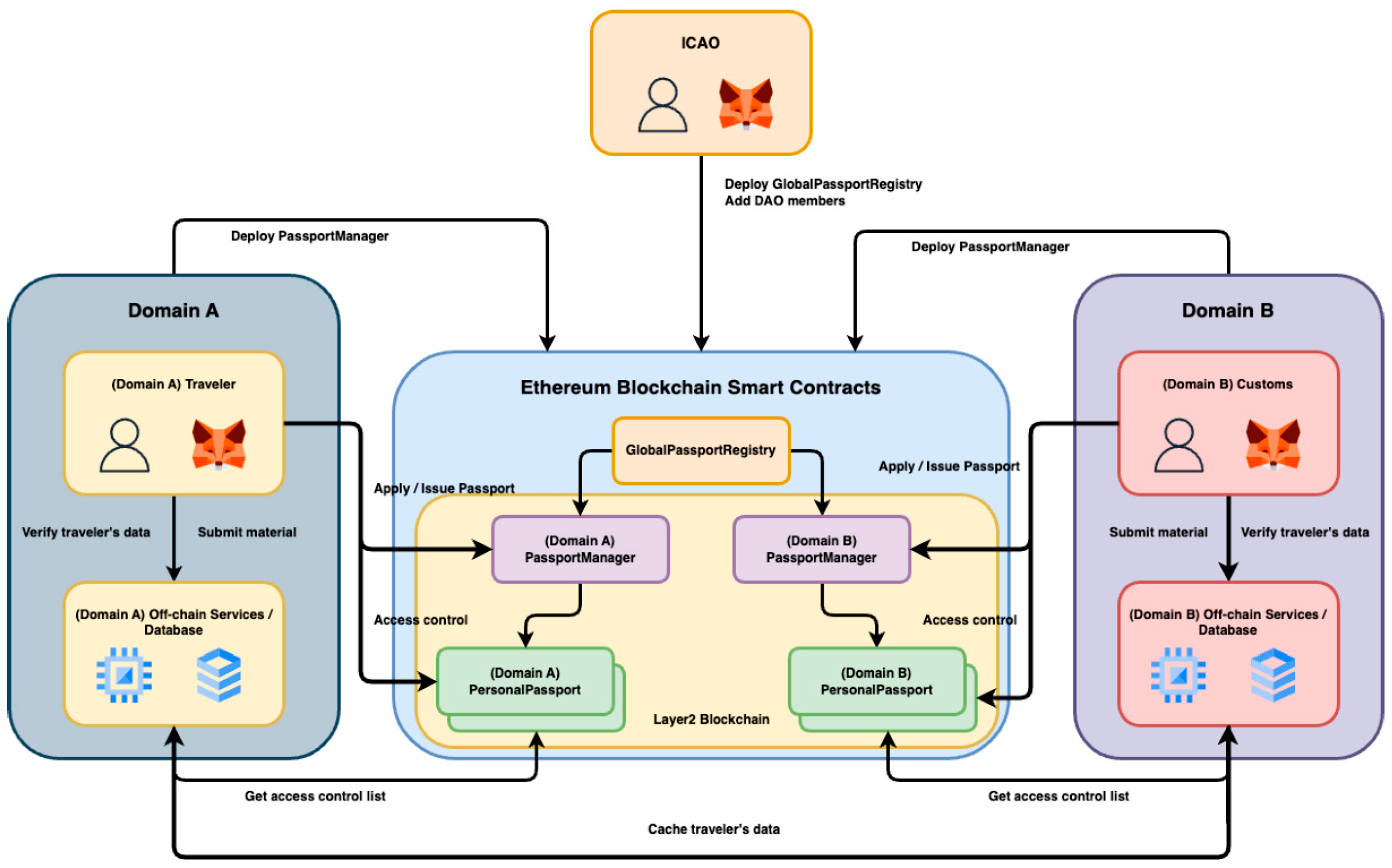

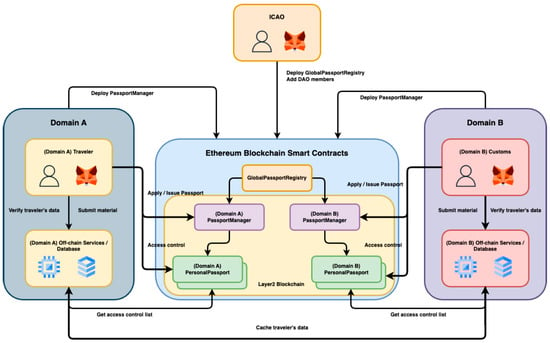

The proposed system adopts a hybrid blockchain architecture, leveraging both the Ethereum mainnet and a Layer 2 solution to balance decentralization with scalability. The Ethereum mainnet hosts the Global Passport Registry smart contract, which functions as a global directory for participating countries. Each entry links a country to its respective Passport Manager contract deployed on a Layer 2 network, enabling individual countries to manage passport issuance and access control independently while maintaining global interoperability.

The choice of a Layer 2 network is driven by the need for high transaction throughput. Regions such as the United States [18] and India [19] have over 100 million passport holders, with millions of new issuances annually, requiring support for a substantial number of operations per second. Preliminary testing on a locally deployed Ethereum mainnet achieved approximately 40 transactions per second, which is insufficient for global demand. Layer 2 integration addresses this limitation, providing the performance necessary to support large-scale, cross-border passport operations.

The architecture is illustrated in Figure 2. The Ethereum mainnet maintains the Global Passport Registry contract, which serves as a registry of verified Passport Manager contracts. Each participating country operates its own set of smart contracts and off-chain services. Upon passport approval, each individual user is assigned a Personal Passport contract, allowing them to directly manage the access control list for their own passport.

Figure 2.

System Architecture.

System Entities

To maintain a clear division of responsibilities and ensure interoperability, the system defines several key entities, each with specific roles within the global architecture.

- International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO): As the initiator of the system, ICAO deploys the Global Passport Registry smart contract and bootstraps the governance process by designating the initial DAO members. ICAO serves as a neutral root of trust, promoting global participation.

- AO Members: DAO members are countries that collectively govern the contents of the Global Passport Registry. They vote on proposals to onboard new countries and manage contract upgrades. Proposals are approved if they receive a majority of votes, although this threshold is configurable to accommodate future policy changes.

- Participating Domains (Countries): Each country operates autonomously by deploying its own Passport Manager contract on the Layer 2 network and implementing a dedicated off-chain backend service. These components can be customized to meet the country’s legal requirements and internal processes, provided they adhere to the shared interface (IPassportManager). Countries are also responsible for verifying and issuing passports to their citizens.

- Users (Travelers): Users submit passport applications and, upon approval, receive a Personal Passport smart contract. This contract is fully owned and controlled by the user, enabling them to manage access permissions through role-based grants. Users can selectively share passport data with other domains, maintaining complete autonomy over their digital identity.

- Off-Chain Services: Each domain also operates an off-chain backend system, implemented with frameworks such as Express.js and MongoDB. These services handle data storage, user authentication, passport metadata processing, and identity verification via signature validation. Off-chain components are essential for system usability and privacy, complementing the on-chain access control logic.

3.2. Cross-Domain Interaction

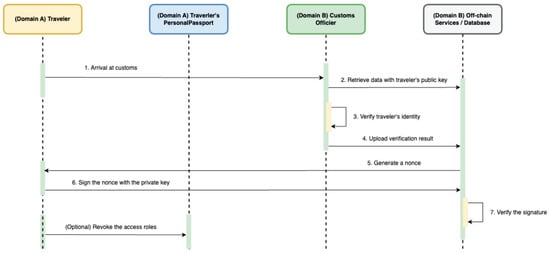

When a traveler from Domain A seeks to enter Domain B, the verification process begins with the traveler granting access permissions through their Personal Passport contract. The customs agency in Domain B queries the Global Passport Registry to locate Domain A’s Passport Manager contract and retrieve the traveler’s Personal Passport contract address. Using cryptographic signatures, the traveler proves ownership of the contract and consents to data access.

Domain B’s system then sends a request to Domain A’s off-chain service to obtain the traveler’s data. Before responding, Domain A’s service verifies on-chain whether the traveler has granted Domain B access. If permission is confirmed, the requested data is returned. This process ensures that traveler data remains protected under user-defined authorization while enabling dynamic, real-time verification during cross-border interactions.

This decentralized and interoperable design provides strong privacy guarantees and traveler autonomy while supporting scalable and verifiable cross-border authentication.

3.3. Access Control and Identity Verification

The access control mechanism is implemented within the Personal Passport contract using role-based access control (RBAC). When a traveler wishes to share data with another domain, they explicitly grant permissions by assigning roles to specific addresses. Customs agencies can access traveler data only if they possess the corresponding roles.

All access control data is stored on-chain, enabling decentralized enforcement, transparency, and verifiability. Permissions are granular and fully revocable by the traveler, ensuring complete data sovereignty.

Identity verification is performed via a nonce-based challenge–response mechanism: the traveler signs a message containing a fresh nonce with their private key, and the customs agency verifies the signature to confirm ownership of the passport contract.

3.4. Interface and Interoperability Guarantees

To ensure interoperability among all Passport Manager contracts, each implementation must conform to the IPassportManager interface. This interface standardizes the functions required for traveler verification, passport issuance, and access control. The Global Passport Registry contract enforces compliance at registration by verifying that each contract supports the required interface functions.

This design ensures that, even if countries deploy customized Passport Manager contracts or utilize diverse backend infrastructures, their smart contracts remain compatible within the global registry framework.

3.5. Governance and Trust Model

The Global Passport Registry contract is initialized by the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), which also designates the initial Decentralized Autonomous Organization (DAO) members. Thereafter, the registry is governed entirely through DAO-based decision-making. Any country seeking to join the system must obtain approval by a majority vote from the existing DAO members.

3.6. Smart Contract Design

3.6.1. Global Passport Registry

The Global Passport Registry contract, shown in Table 3, is deployed on the Ethereum mainnet and maintains a mapping of country codes to their respective Passport Manager contract addresses on Layer 2. It supports proposals and DAO-based voting to register new countries or update existing entries. Serving as a verifiable root of trust across jurisdictions, the contract ensures that all participating domains comply with standardized protocols and remain accountable within the global system.

Table 3.

Global Passport Registry.

3.6.2. Passport Manager

The Passport Manager contract, shown in Table 4, is deployed for each domain and manages the issuance, review, and revocation of individual passports. It interacts with the Global Passport Registry for registration and with Personal Passport contracts for user-specific operations. Its key functionalities include creating Personal Passport contracts, verifying applicant eligibility, and linking relevant off-chain records.

Table 4.

Passport Manager

3.6.3. IPassportManager

The IPassportManager interface specifies the function signatures that every country’s Passport Manager contract must implement. These include functions for passport creation, address resolution, and contract metadata retrieval, ensuring standardization and interoperability within the global ecosystem.

3.6.4. Personal Passport

The Personal Passport contract, shown in Table 5, is a user-specific smart contract that manages access control policies and authorization records. It allows users to assign roles to external addresses, such as other countries, and grants them full control over their contract, including the ability to revoke permissions at any time.

Table 5.

Personal Passport

3.6.5. Roles

The Roles contract is a helper contract that provides role-based access control logic for both the Passport Manager and Personal Passport contracts. It defines standardized role constants and utility functions for role assignment and permission verification. Together, these five contracts form the core of the system’s smart contract infrastructure, enabling modular, extensible, and secure operations across sovereign domains.

3.6.6. Customizability of Passport Manager and Personal Passport

To accommodate diverse legal and procedural requirements, each participating domain has full flexibility to customize its implementation of Passport Manager and Personal Passport contracts. While Passport Manager must conform to the IPassportManager interface to ensure cross-domain compatibility, countries can extend the contract with domain-specific logic, such as additional application workflow steps, multi-level approvals, or custom event logging.

Similarly, Personal Passport contracts can be augmented with new role types, access conditions, or integration points with national infrastructure. For instance, a Personal Passport could be extended to integrate with a national health certification system, enabling travelers to selectively share verified vaccination or health credentials during cross-border travel, thereby enhancing public safety while preserving user privacy and control.

This modular and decentralized design allows countries to maintain policy independence while adhering to a shared protocol layer that ensures global interoperability.

4. Implementation

4.1. Development Environment and Tools

The system was developed using the Solidity programming language, with Hardhat [20] providing a flexible local environment for compiling, testing, and deploying smart contracts. OpenZeppelin libraries were employed for standardized implementations of common patterns, including AccessControl [21] and ERC-165 [6] interface detection.

The system begins by initializing the DAO with a list of addresses upon deployment of the Global Passport Registry contract. Each participating country then deploys its own Passport Manager contract on a Layer 2 network and registers it through the DAO proposal process.

Upon approval of a citizen’s passport application, a Personal Passport contract is deployed to the blockchain. This deployment is triggered via the issuePassport function of the Passport Manager contract and executed by the applicant. The new contract address is mapped to the user’s public key for easy retrieval and verification.

The Personal Passport contract also stores a hash of off-chain metadata, computed using keccak256 (SHA-3). While the metadata itself is maintained off-chain, the on-chain hash serves as the canonical reference to ensure data integrity.

4.2. Function Implementation Details

The system’s smart contracts leverage OpenZeppelin libraries and adhere to Solidity standards to ensure modularity, interoperability, and robust security.

4.2.1. Interface Verification

Interface compliance is ensured through ERC-165, a standard that allows smart contracts to declare which interfaces they support via the supportsInterface (bytes4 interfaceId) function. The interface ID is a 4-byte value derived from the XOR of all function selectors in the interface. In this system, the Passport Manager explicitly declares support for the IPassportManager interface using this mechanism, guaranteeing that any contract registered in the Global Passport Registry implements the required functions. The Global Passport Registry leverages Solidity’s mapping and struct features to manage DAO proposals and Passport Manager registrations. Interface compatibility is verified through ERC-165 by calling the supportsInterface function on proposed contracts. Unauthorized registrations are prevented by the DAO voting system, and successful proposals trigger the addPassportManager function.

4.2.2. Passport Application Status

The Passport Manager contract maintains application records and manages the lifecycle of passport requests. Each request is stored in a mapping keyed by the applicant’s address. The contract enables the issuing authority to approve or reject applications and deploys a Personal Passport upon approval. It also provides a verifyPassport function to validate the authenticity of a passport.

4.2.3. Access Control

Access Control is an OpenZeppelin role-based access control (RBAC) module that enables fine-grained permissions within smart contracts. Each role is defined as a bytes32 constant, typically computed using keccak256 (“ROLE_NAME”). Roles can be assigned or revoked for specific addresses. The onlyRole modifrier restricts function calls to designated roles, while hasRole allows programmatic verification of access. This design simplifies permission management and ensures clear ownership and authorization logic throughout the passport system.

The Personal Passport contract implements RBAC using OpenZeppelin’s AccessControl. Roles such as NAME_VIEWER and PHOTO_VIEWER are represented by hashed constants. Functions are provided to grant or revoke roles individually or in batches, and access permissions are checked via hasRole. These roles control which domains can access specific fields of the passport.

4.2.4. Batch and Atomic Functions

The contract includes a batch role assignment function, grantAccessBatch, which improves usability when multiple roles must be granted to a single domain. This is particularly useful for domains such as foreign government agencies that require access to several fields—like name, nationality, and date of birth—simultaneously. Granting roles in batch reduces the number of transactions, optimizing gas usage.

To ensure correctness, an atomic design pattern is applied. Before any role is granted, the contract verifies that all roles in the input array are valid by cross-checking them against a predefined internal registry. If even a single role is invalid, the function reverts without modifying the contract state. This prevents partial execution and preserves data integrity, ensuring that users do not inadvertently assign an incomplete or inconsistent permission set. The same atomic design applies to revokeAccessBatch to maintain reliability in access control operations.

4.3. SystemWorkflows

When a traveler from country A seeks entry to country B, country B performs an on-chain lookup via the Global Passport Registry to locate country A’s registered Passport Manager. The getPassportAddress function retrieves the traveler’s Personal Passport address.

Once the Personal Passport address is obtained, country B verifies on-chain whether it has access to specific fields using the hasRole function. If access is confirmed, country B sends a request to country A’s Express.js backend, providing the public key and passport contract address.

Country A’s backend interacts with the traveler’s Personal Passport smart contract, validating access for each requested field by checking assigned roles. If access is permitted, the corresponding data is retrieved from the database and selectively returned to country B, ensuring privacy and user consent at every step.

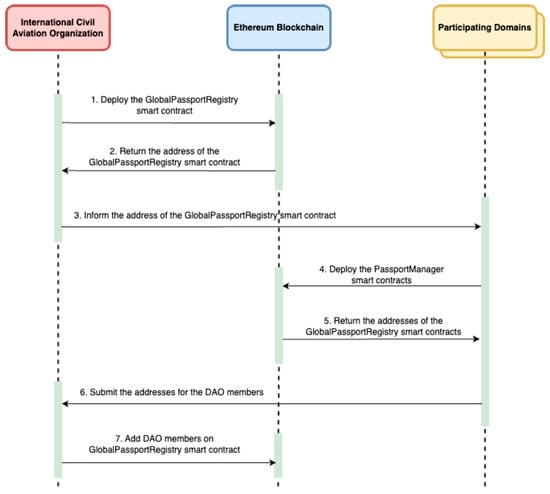

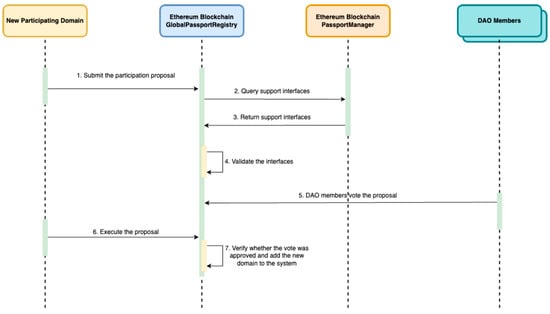

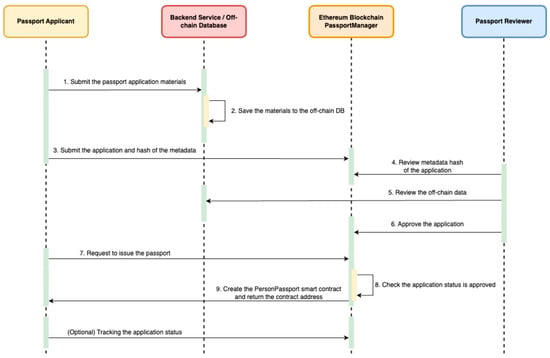

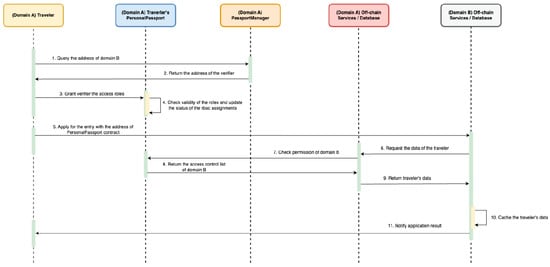

To illustrate system operation across its components, five workflow diagrams are provided. These visualizations depict how smart contracts and off-chain services interact during key processes.

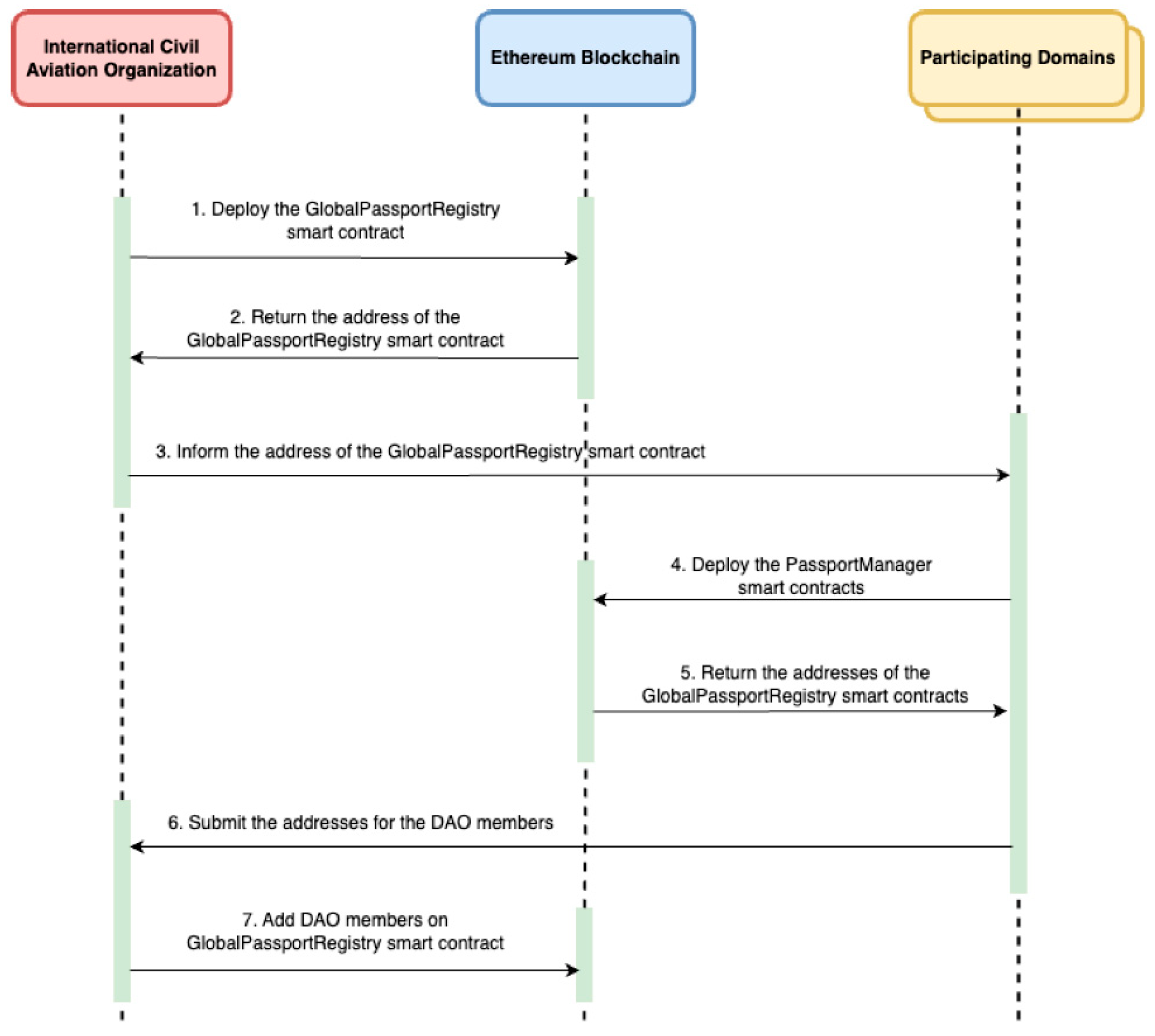

4.3.1. System Initializations

The initialization process begins with the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) deploying the Global Passport Registry smart contract on the Ethereum mainnet, as shown in Figure 3. Once deployed, ICAO shares the contract address with all participating countries, which then independently deploy their Passport Manager contracts on Layer 2 networks to ensure scalability.

Figure 3.

System Initialization Workflow.

After deployment, each country submits its Passport Manager address to ICAO. ICAO aggregates these addresses and registers DAO members in the Global Passport Registry via the addDaoMember function. These DAO members collectively form the decentralized governance body responsible for managing participation proposals and registry updates.

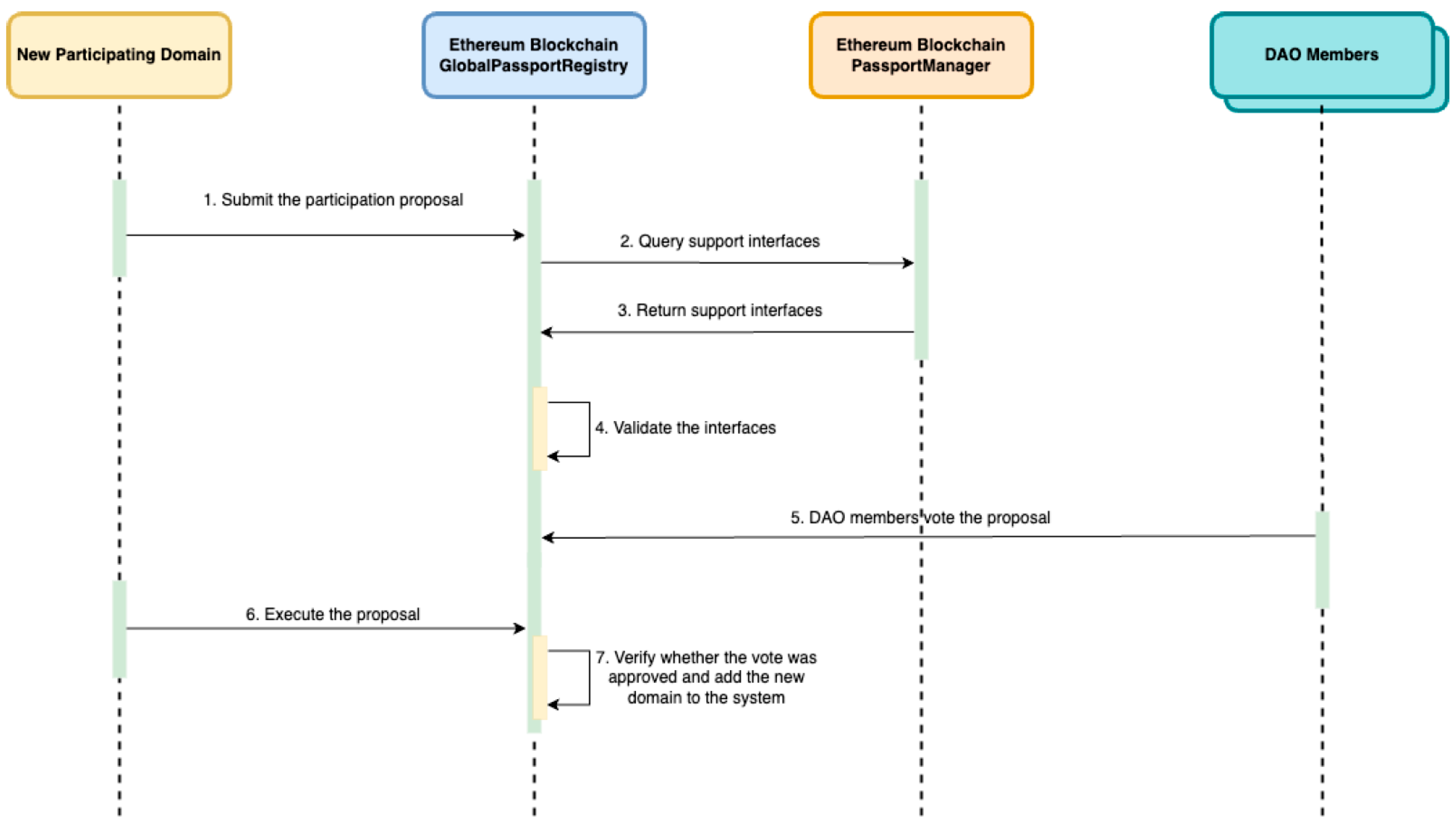

When a new country wishes to join the system, it submits a participation proposal to the Global Passport Registry. The proposal includes the address of the newly deployed Passport Manager and a textual domain identifier. The registry validates the proposal through a two-step process. First, it calls the supportsInterface function on the submitted contract to verify compliance with the IPassportManager interface, as specified by ERC-165. Proposals that fail this validation are automatically rejected to prevent incompatible contracts from being registered. The workflow for a new country joining the system is illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Add New Domain Workflow.

If the contract passes validation, the proposal is opened for DAO voting. Votes are recorded on-chain to ensure transparency. Currently, a simple majority (>50%) is required for approval. This threshold can be adjusted in future upgrades to adopt stricter governance models, such as a two-thirds majority or role-weighted voting, based on geopolitical or security considerations.

Once consensus is reached, the new country can trigger the executeProposal function, which finalizes registration by adding the new domain and its Passport Manager contract to the registry. This fully on-chain process ensures that all participants meet system requirements and are approved through transparent, verifiable governance.

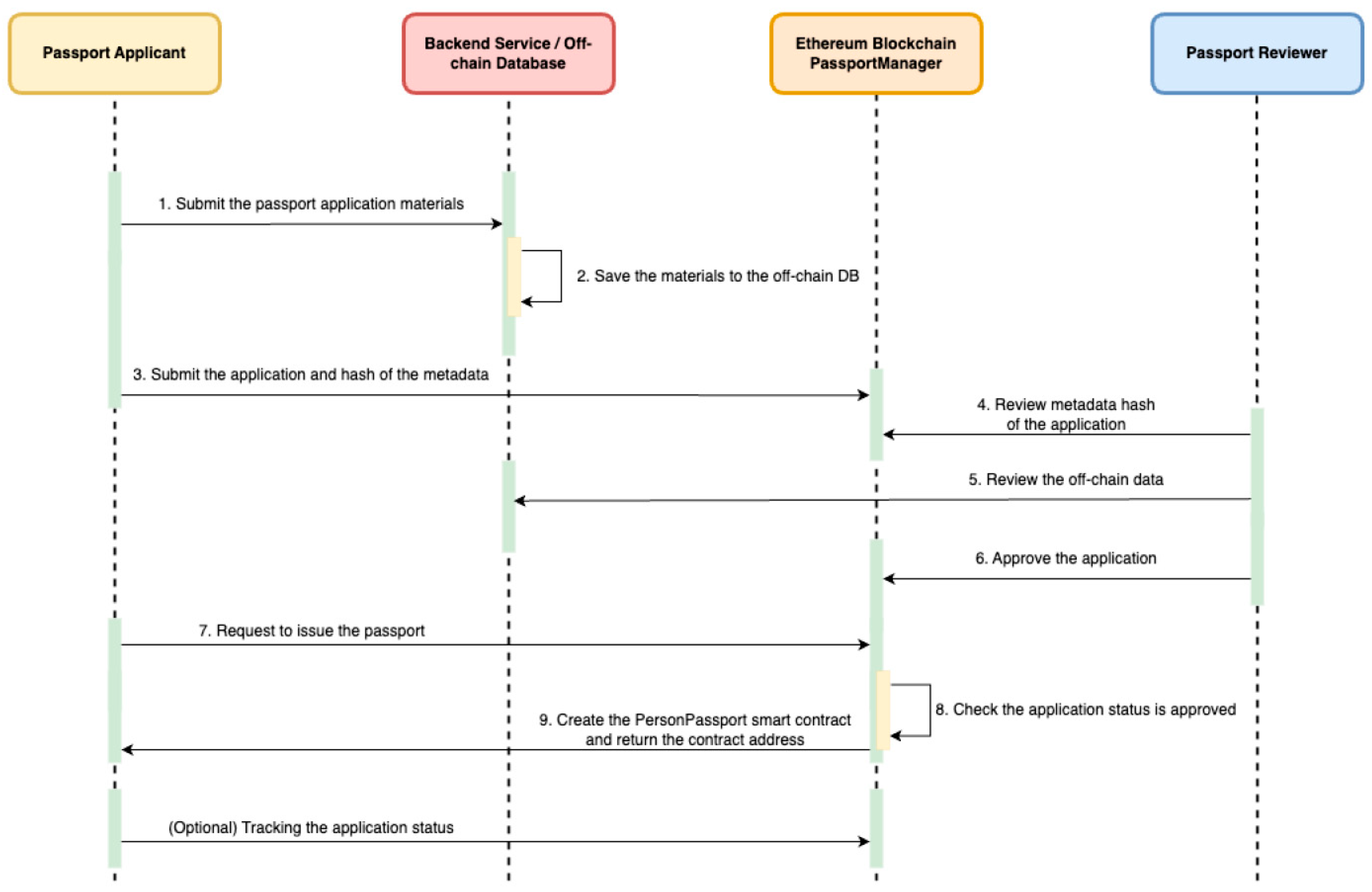

4.3.2. Apply Passport

When a user applies for a passport, the process begins with submitting application materials to the backend services, including personal information and a photo, as illustrated in Figure 5. The backend stores these details in an off-chain database and computes a keccak256 hash of the metadata. This hash serves as a link between the off-chain data and the on-chain record.

Figure 5.

Apply Passport Workflow.

The applicant then submits the hash to the on-chain Passport Manager contract to register their application. A designated reviewer verifies the consistency and validity of the on-chain hash against the off-chain data. Upon approval, the applicant can call the issuePassport function, which deploys a Personal Passport contract on-chain. The contract address is returned to the applicant, establishing a formal cryptographic identity.

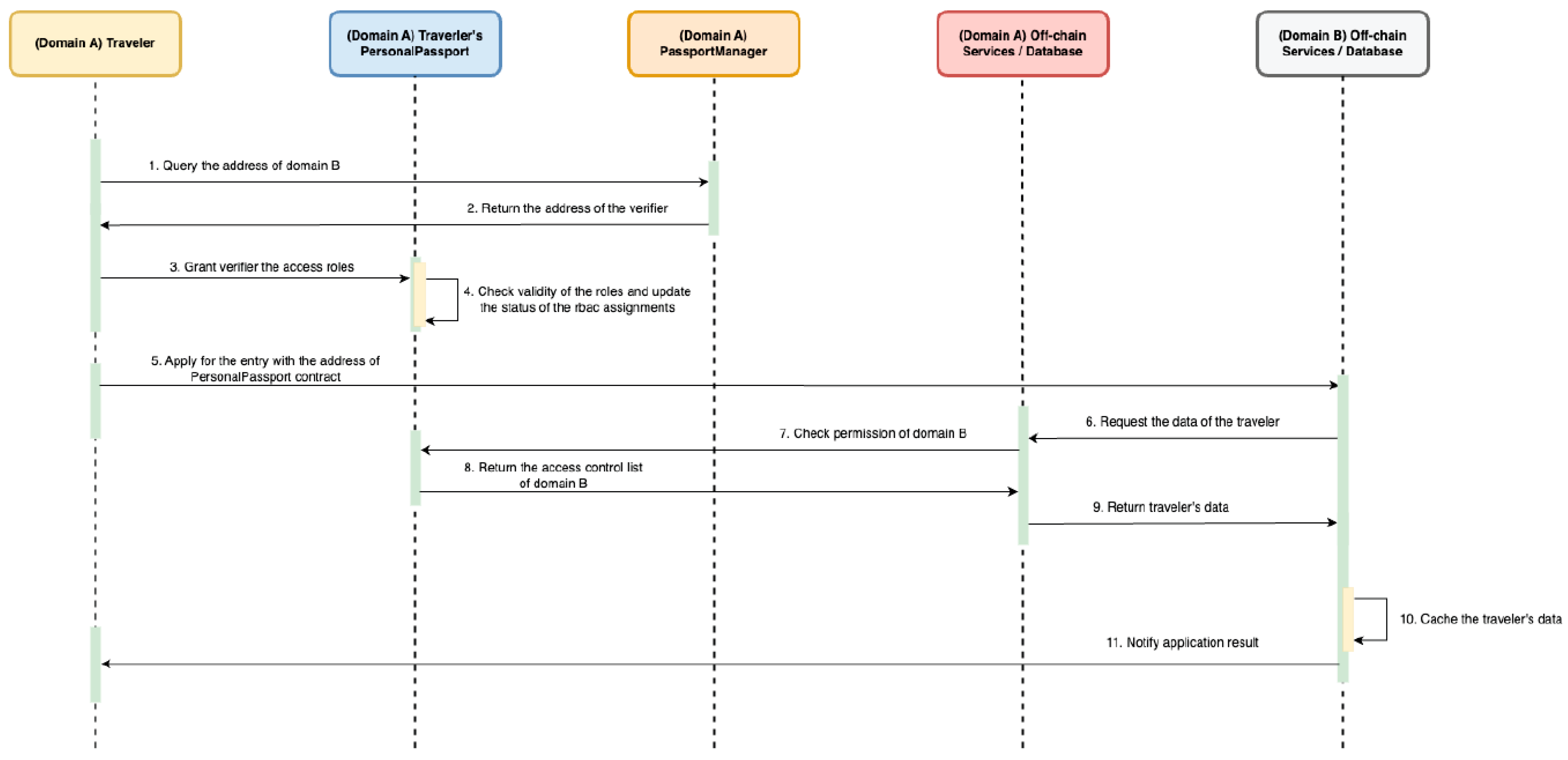

4.3.3. Apply Visa

To request a visa, a traveler from country A must first grant country B permission to access their passport information, as shown in Figure 6. The traveler assigns roles—such as NAME_VIEWER or NATIONALITY_VIEWER—to country B’s address via their Personal Passport contract.

Figure 6.

Apply Visa Workflow.

Once permission is granted, country B submits the traveler’s passport address to country A’s backend and requests access to specific data fields. The backend verifies on-chain whether country B has the required roles by calling hasRole for each requested field. If access is valid, country A retrieves the corresponding data from its database and returns it to country B. This process ensures that unauthorized domains cannot access the information and that the traveler retains full control over access permissions.

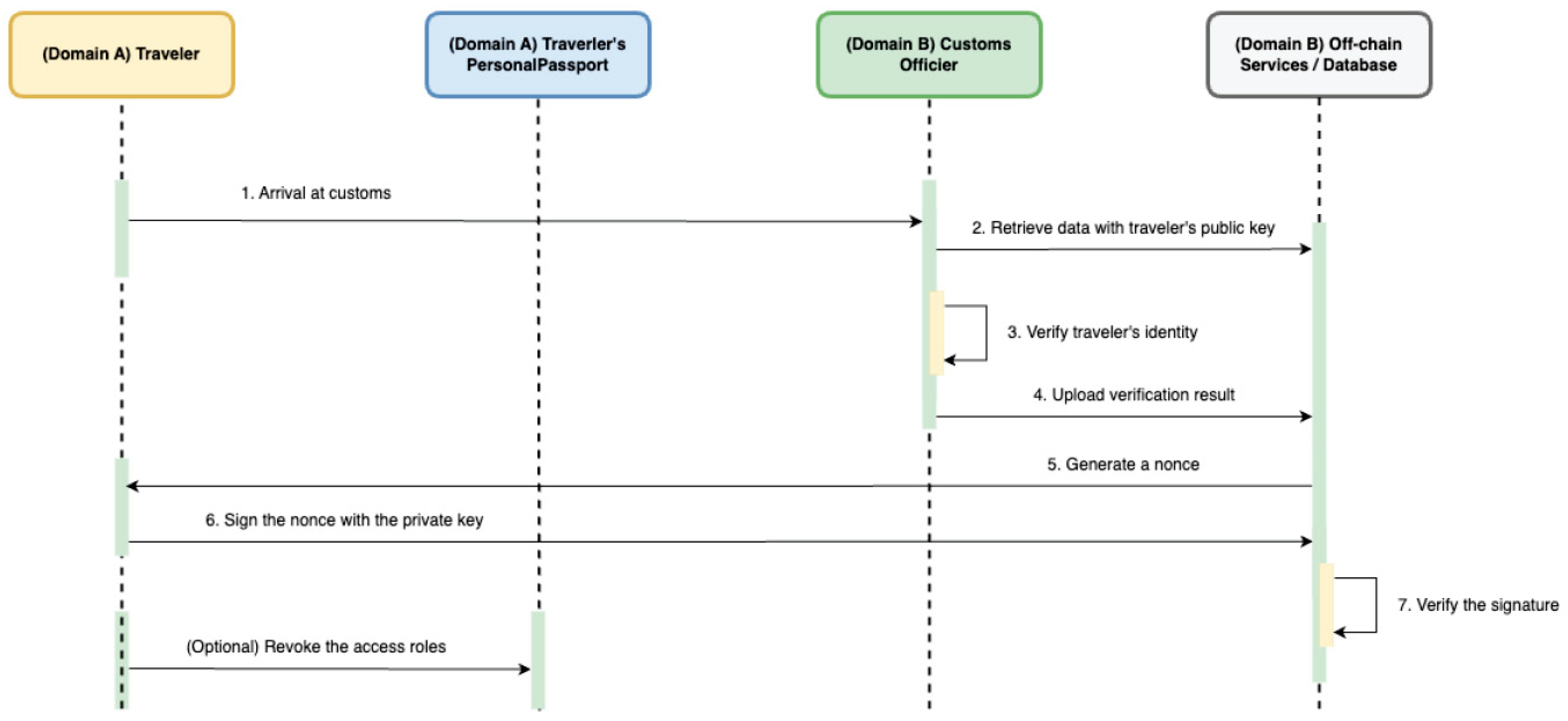

4.3.4. Identity Verification

When a traveler arrives at customs, country B initiates a nonce-based challenge–response protocol to verify the traveler’s identity, as shown in Figure 7. Country B first retrieves the traveler’s public key and queries country A’s backend for the relevant passport data. After confirming that access has been granted, the system generates a unique nonce and sends it to the traveler. The traveler signs the nonce using their private key—typically via MetaMask—and returns the signature. Country B’s backend verifies the signature off-chain using the traveler’s public key to confirm that the signer is the legitimate passport holder. Upon successful verification, the traveler is authenticated and may optionally revoke previously granted roles to limit future access.

Figure 7.

Identity Verification Workflow.

4.3.5. TravelerWorkflow Overview

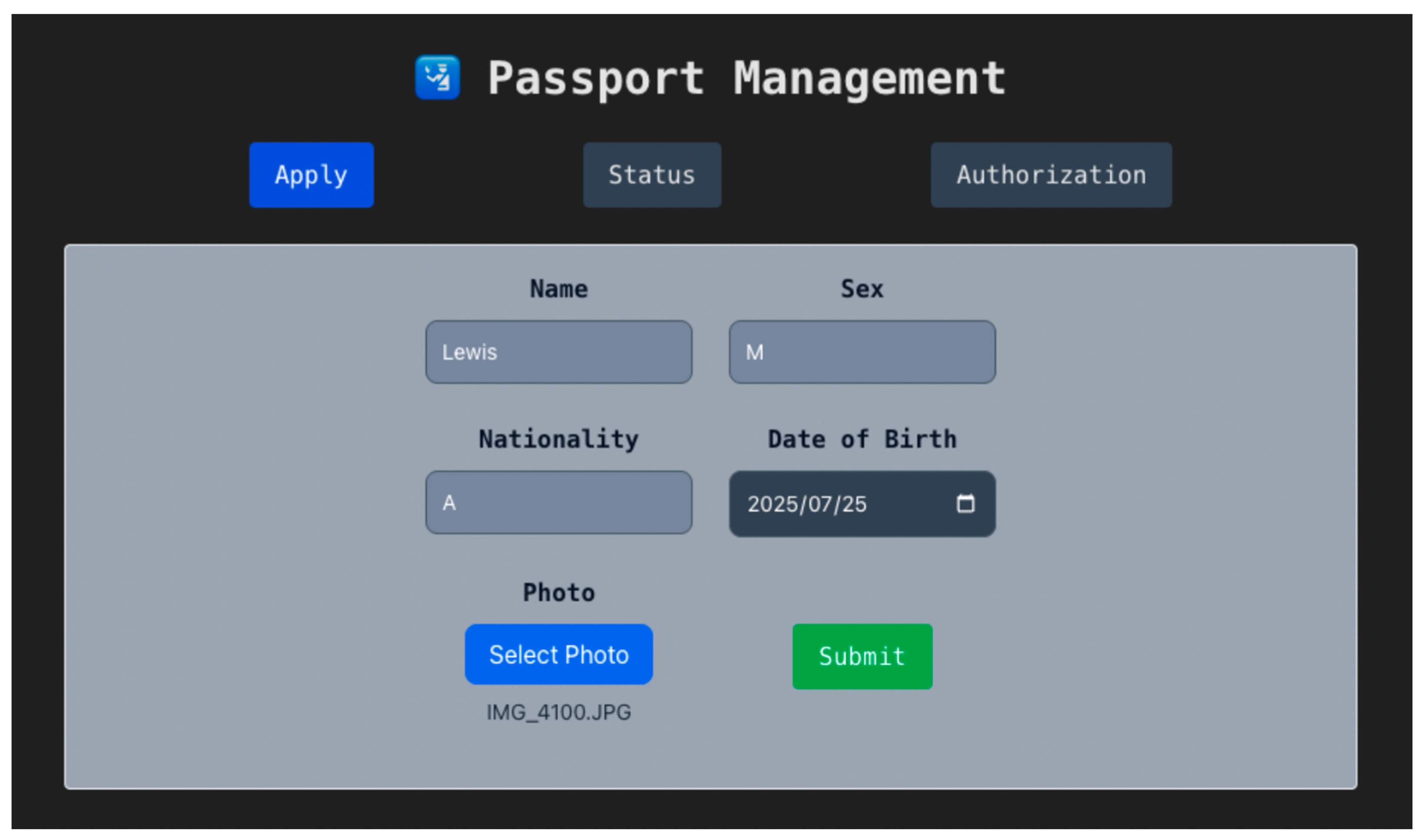

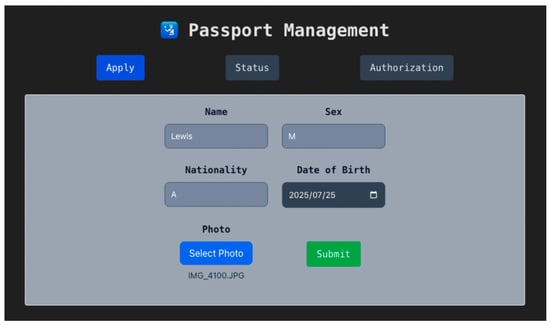

To illustrate the system from the end-user’s perspective, this section presents a typical workflow for a traveler interacting with the decentralized passport system.

- Passport Application:

The traveler first visits the official web portal of their home country and navigates to the passport application page, as shown in Figure 8. They fill in personal details such as name, nationality, sex, date of birth, and upload a passport photo. Upon submission, the backend stores the metadata off-chain and computes its keccak256 hash. The traveler is then prompted to confirm a transaction via their wallet (e.g., MetaMask) to call applyPassport on their country’s Passport Manager contract.

Figure 8.

Passport Application Page.

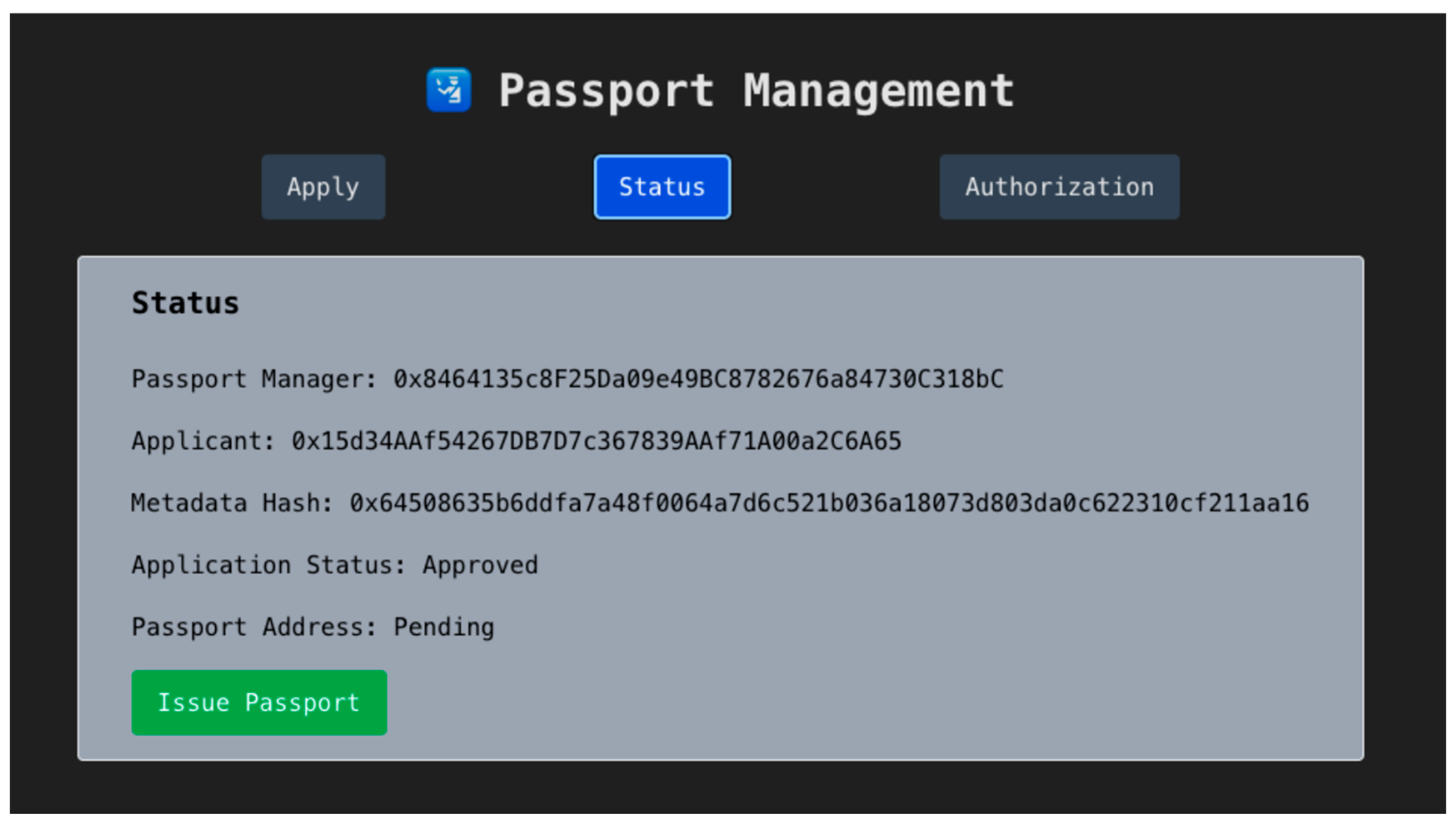

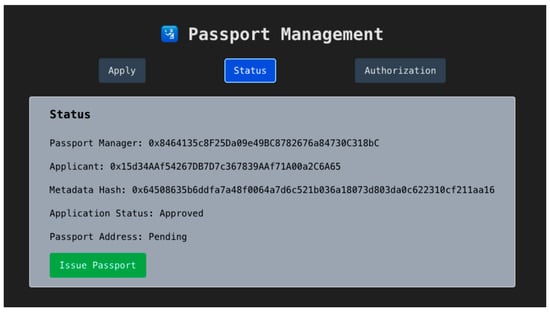

After administrative review, the application is either approved or rejected, as illustrated in Figure 9. The traveler can track the application status on the portal, which reflects the current metadata hash, review result, and the contract address status.

Figure 9.

Passport Status Page—Approved

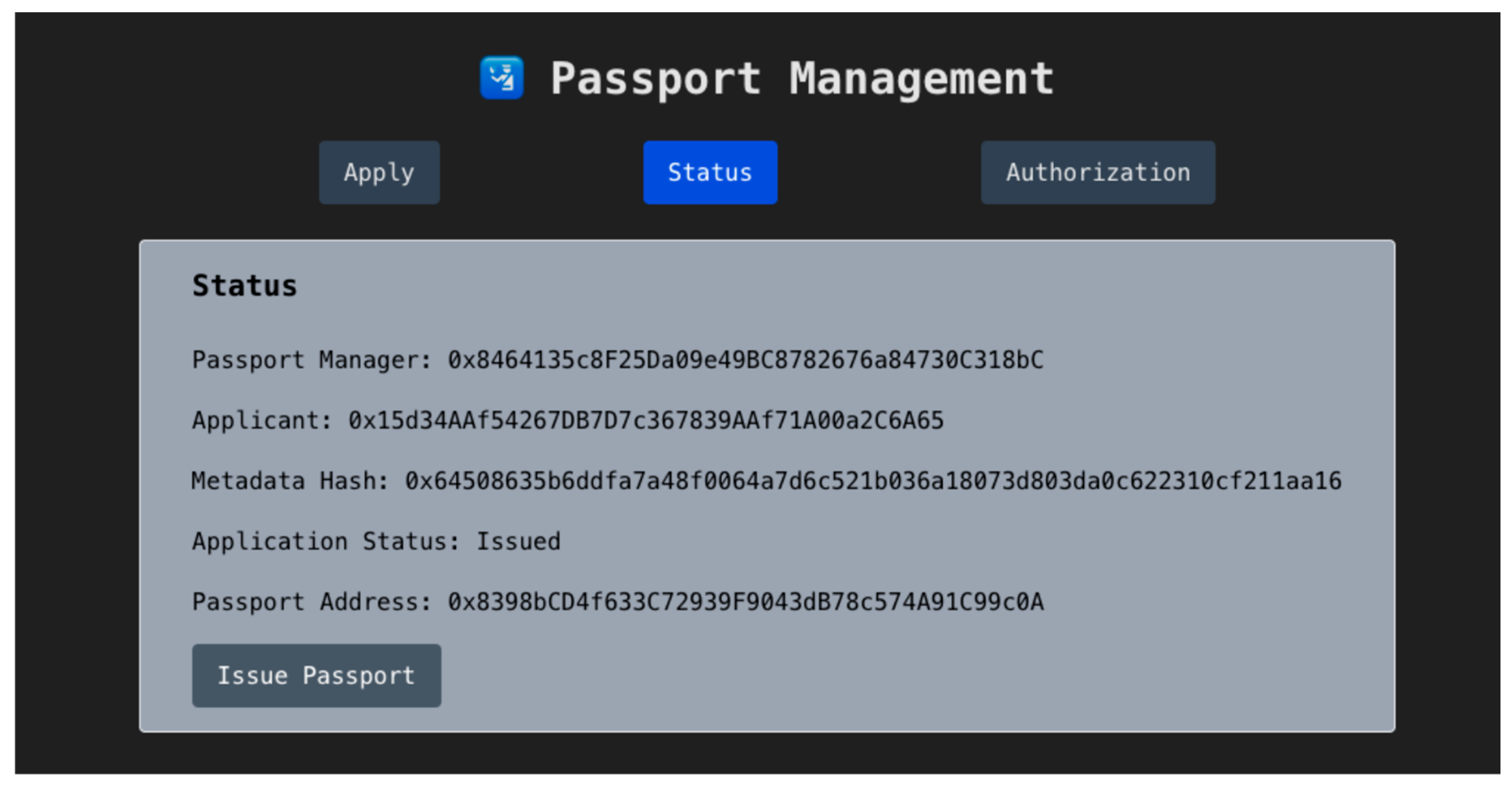

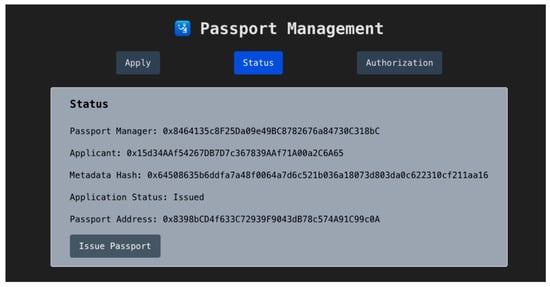

Once approved, the traveler can initiate issuance by signing a second transaction to call issuePassport, as shown in Figure 10. This deploys a new Personal Passport contract tied to their address.

Figure 10.

Passport Status Page.

- 2.

- Travel Authorization:

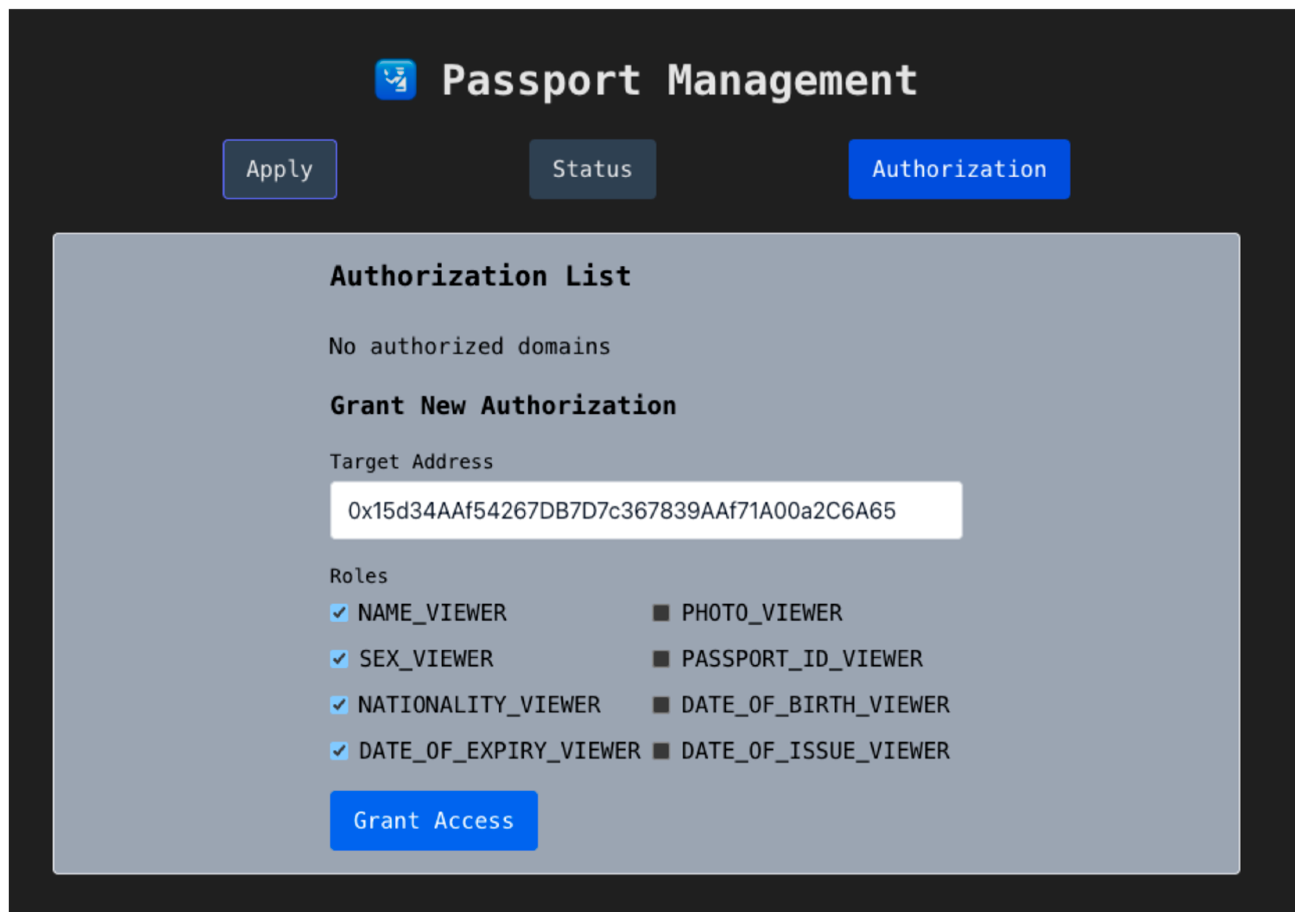

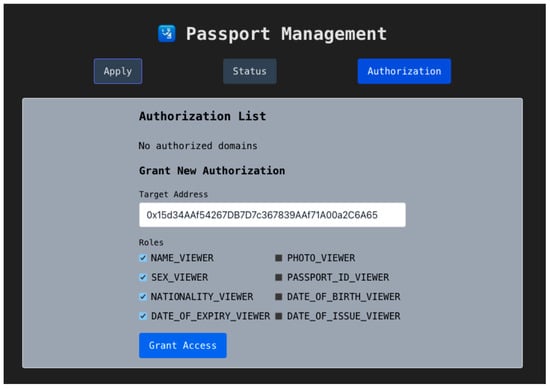

Before departing for country B, the traveler logs into the portal and navigates to the authorization interface, as shown in Figure 11. They enter country B’s address and select the specific fields they wish to share—for example, name, sex, nationality, and passport expiry date.

Figure 11.

Access Control Page—Grant Access.

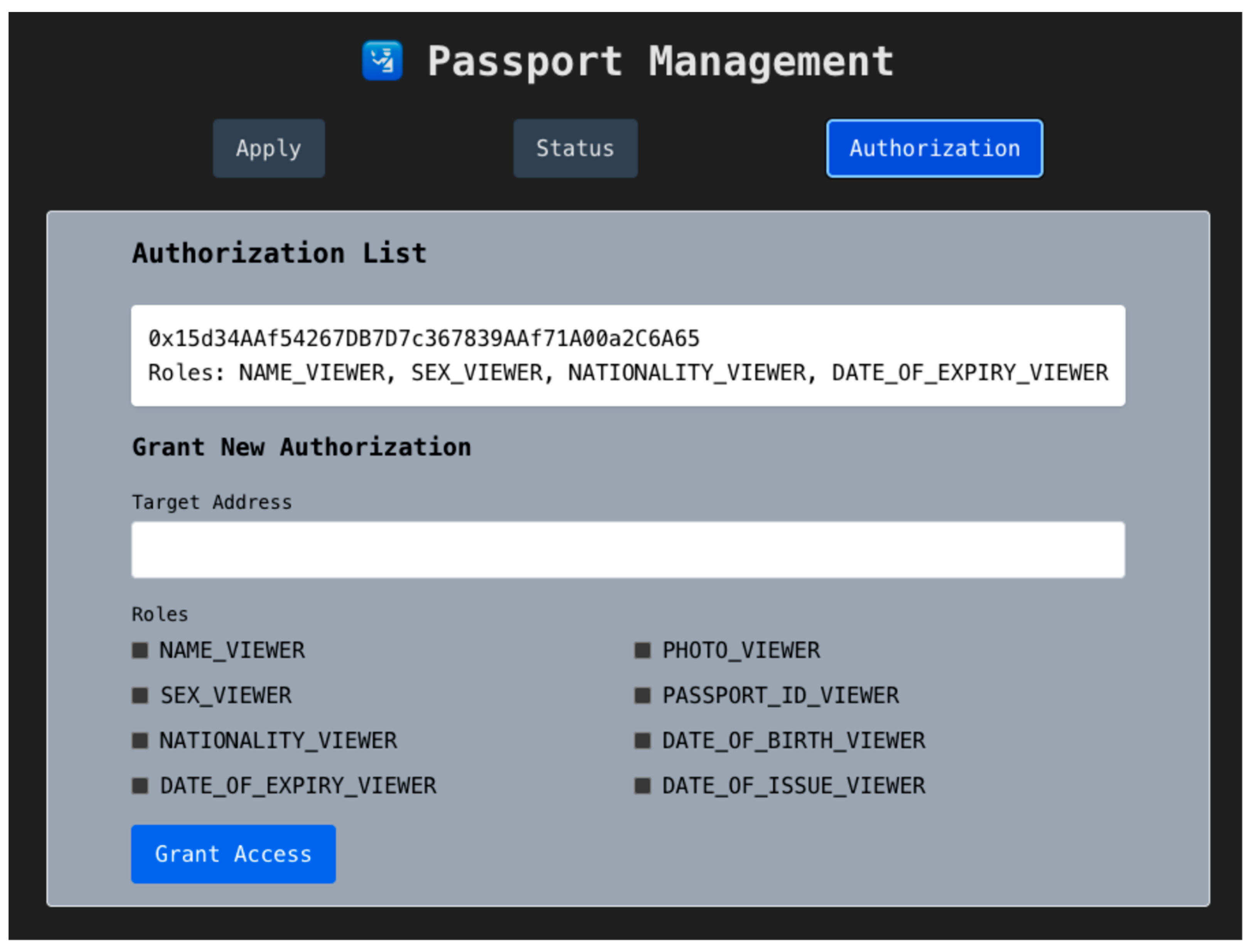

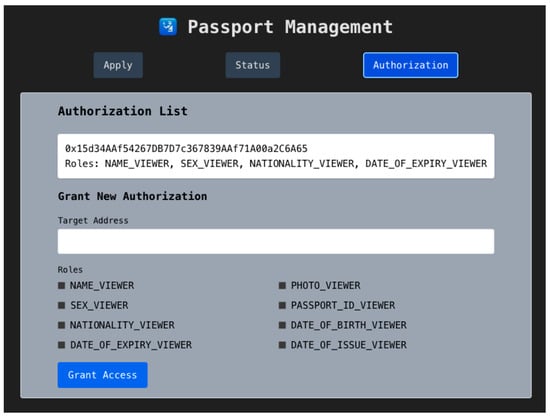

Upon confirmation, a grantAccessBatch transaction is sent to the traveler’s Personal Passport contract. The current access list is updated and displayed on the portal, as illustrated in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

Access Control Page—Authorization List.

4.4. Gas Optimization

To minimize gas consumption, several optimizations were implemented. Role constants are hashed once and reused throughout the contract, and events are emitted instead of performing extensive storage writes for logging. In the Personal Passport contract, role management leverages OpenZeppelin’s AccessControl [21,22], which uses efficient internal storage mappings.

Additionally, Personal Passport contracts are deployed dynamically only when necessary. Metadata is stored off-chain, with only the keccak256 hash and access control list maintained on-chain, preventing the blockchain from being burdened with large data payloads. The supportsInterface pattern further ensures interaction only with compliant contracts, catching failed calls early and avoiding unnecessary gas expenditure.

5. Evaluation

5.1. Test Environment Setup

To evaluate the gas efficiency and transaction throughput of our system on Ethereum Layer 1, we conducted a series of performance benchmarks using Hardhat, a widely adopted development framework for Ethereum. All experiments were executed on a local Hardhat network running on a single machine, simulating 300 distinct accounts.

We focused exclusively on state-changing functions, including applyPassport, approveApplication, issuePassport, rejectApplication, grantAccess, revokeAccess, grantAccessBatch, and revokeAccessBatch.

To simulate varying transaction loads, we designed a benchmarking harness that sends transactions at predefined rates (e.g., 10, 20, …, up to 300 tx/s) for a fixed duration of 5 s per rate. These experiments measure both the gas consumption of individual functions and the overall system throughput.

5.2. Test Result and Evaluation

5.2.1. Gas Consumption

We first evaluated the gas consumption of each key state-changing function in the system. All functions were executed under controlled conditions on a local Hardhat network. The values reported represent the average gas used, calculated over multiple runs with different user accounts.

Table 6 summarizes the gas usage of the main contract functions. Functions such as applyPassport and grantAccess incur moderate gas costs, whereas issuePassport is the most expensive operation due to on-chain contract deployment. In contrast, rejectApplication and revokeAccess are relatively lightweight operations.

Table 6.

Average Gas Consumption per Function.

To contextualize the gas usage of our system, we compare it with prior work. In a similar blockchain-based identity and data-sharing platform [23], functions such as bindAccount, setEncryptCSR, and setEncryptPrivateKey consume 737,645, 749,239, and 411,582 gas, respectively.

By comparison, our applyPassport and grantAccessBatch operations consume 140,688 and 192,971 gas, significantly lower than comparable operations in the related work. Our most expensive operation, issuePassport, which dynamically deploys a Personal Passport contract, consumes approximately 1.98 million gas. This is comparable to the createIdentityManagerContract operation in [23], which requires around 1.42 million gas, and is considered reasonable given the on-chain deployment overhead.

These results demonstrate that the gas costs of our system are within a justifiable range for Ethereum Layer 1 smart contract operations, particularly considering the associated functionalities and on-chain data storage requirements.

5.2.2. Requirement Analysis

To estimate the system’s throughput requirements, we analyze passport issuance and usage in five populous regions: India, China, the EU, Japan, and the United States. These regions collectively represent a significant portion of the global population and international travel, providing a reasonable lower-bound reference for system demand.

We consider two primary use cases: (1) issuance of new passports and (2) write operations related to active passport usage, such as metadata updates or authorization events.

For the first scenario, China reportedly issues around 25 million new passports annually [24]. Assuming similar issuance volumes in the other regions, we estimate a total of 125 million new passports issued per year across these five regions, or approximately 340,000 issuances per day. With three on-chain transactions per issuance, this corresponds to roughly 12 transactions per second (TPS).

The second scenario concerns ongoing usage of active passports, such as cross-border travel events that trigger on-chain operations like metadata updates or access control changes. According to travel statistics, U.S. citizens made over 90 million outbound trips in 2023 [25], while around 170 million U.S. citizens hold valid passports [18], suggesting that roughly 50% of passports are actively used each year. Conservatively assuming that 50% of all issued passports are used annually and that each active passport triggers five write operations on-chain per year, we calculate system demand.

Across the United States (170 M), Japan (20 M) [26], China (200 M) [16], the EU (200 M, assuming half hold passports), and India (90 M) [19], there are approximately 680 million passport holders, of which 340 million are active annually. With five write operations per active passport, the system would need to support roughly 1.7 billion on-chain operations per year, equating to approximately 54 TPS.

This analysis indicates that a target throughput of around 70 TPS would be sufficient to support real-world passport issuance and usage at a global scale.

5.2.3. Function Throughput

We first conducted extensive throughput benchmarking across the state-changing functions of our system. The experiments were executed on a local Hardhat Ethereum Layer 1 network with 300 distinct accounts, simulating increasing transaction rates from 10 to 300 transactions per second (tx/s).

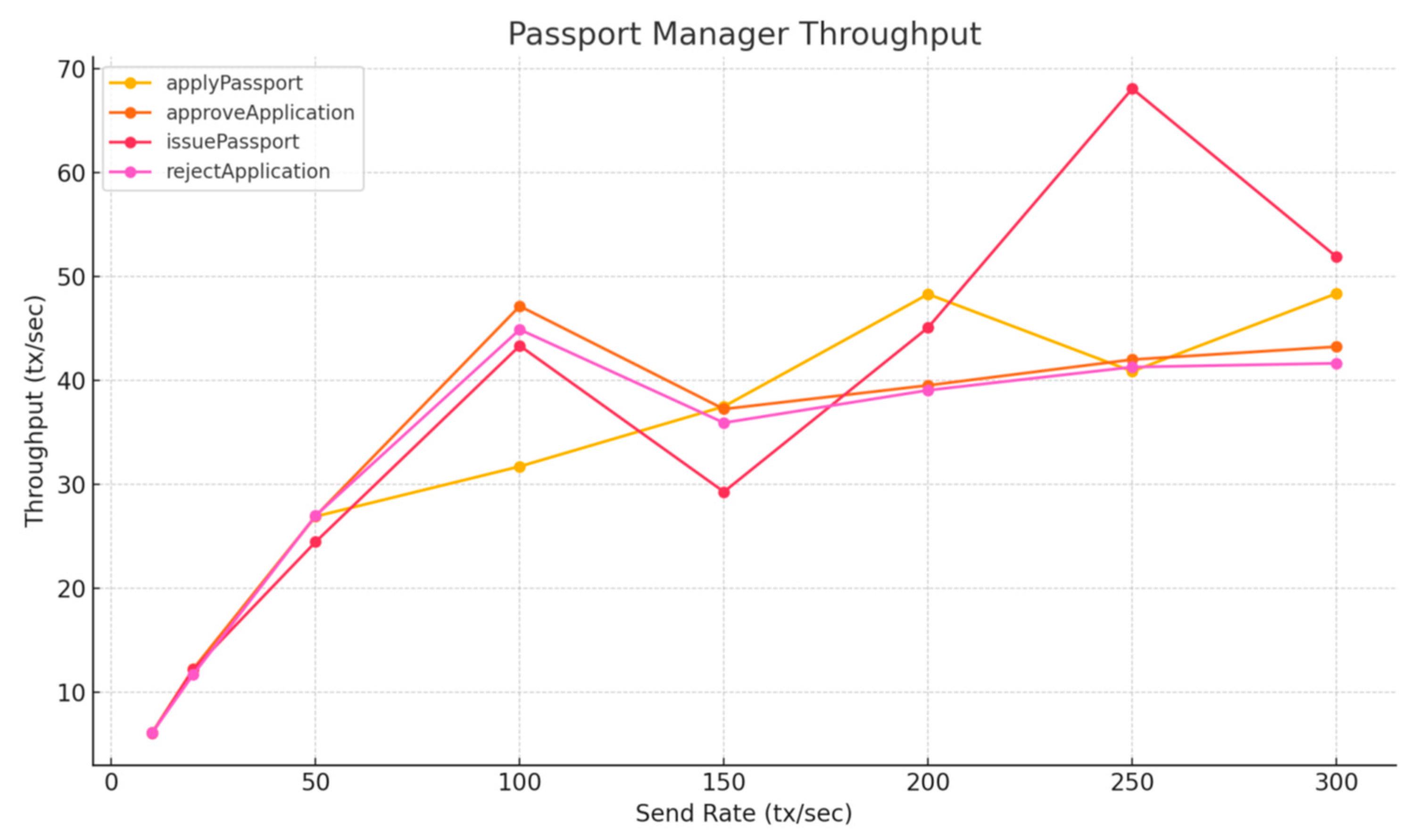

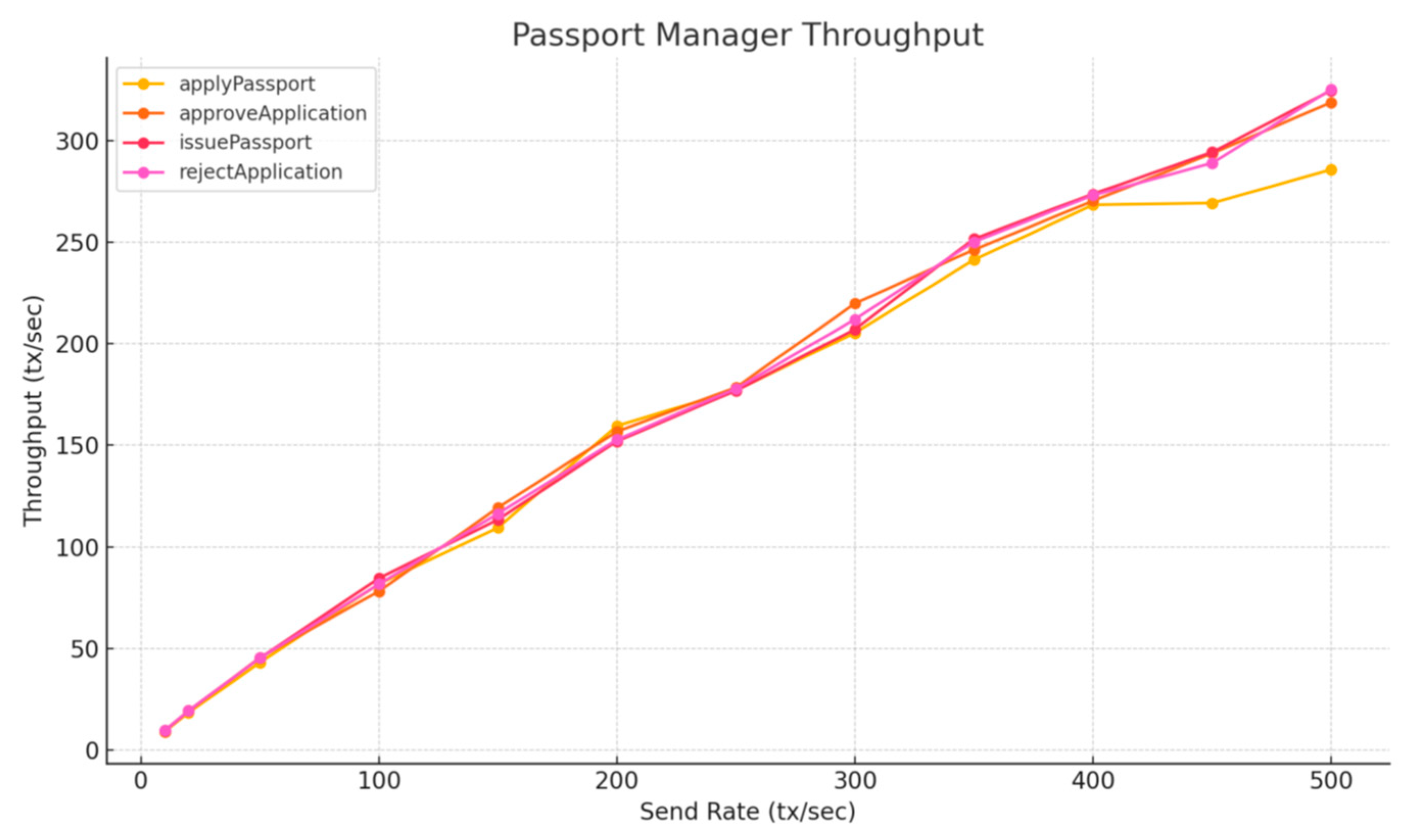

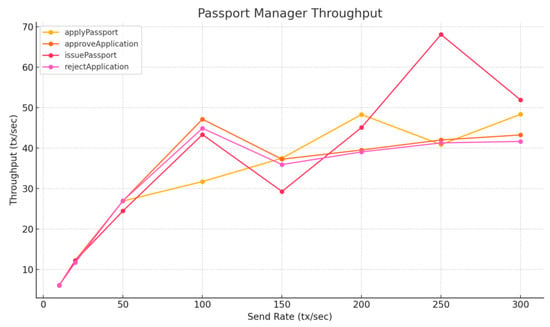

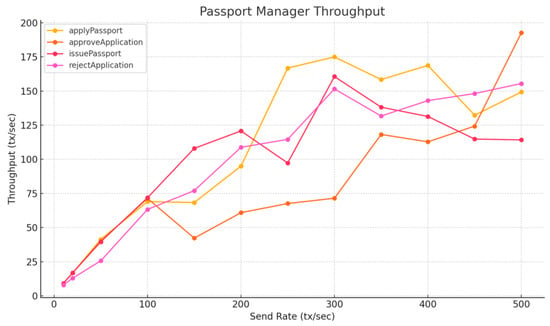

Among the Passport Manager contract functions, all tested operations—including applyPassport, approveApplication, issuePassport, and rejectApplication—exhibited similar throughput patterns (Table 7, Figure 13). As the send rate increased, throughput rose steadily to around 40–50 tx/s. This trend was consistent regardless of a function’s complexity or gas usage, suggesting that beyond a certain load, throughput is limited by external factors rather than contract logic alone.

Table 7.

Throughput of each function under varying send rates—Layer 1.

Figure 13.

Passport Manager Throughput—Layer 1.

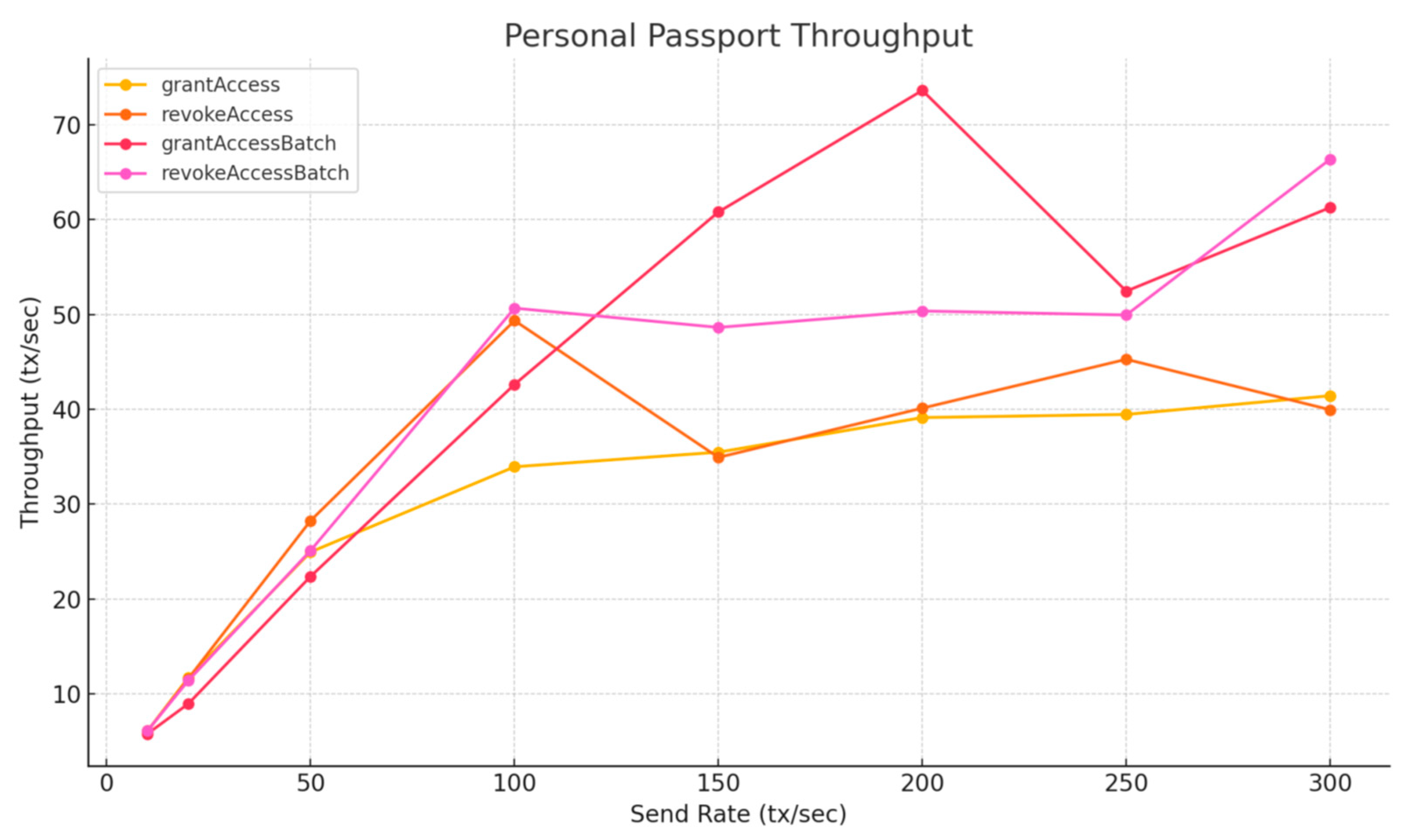

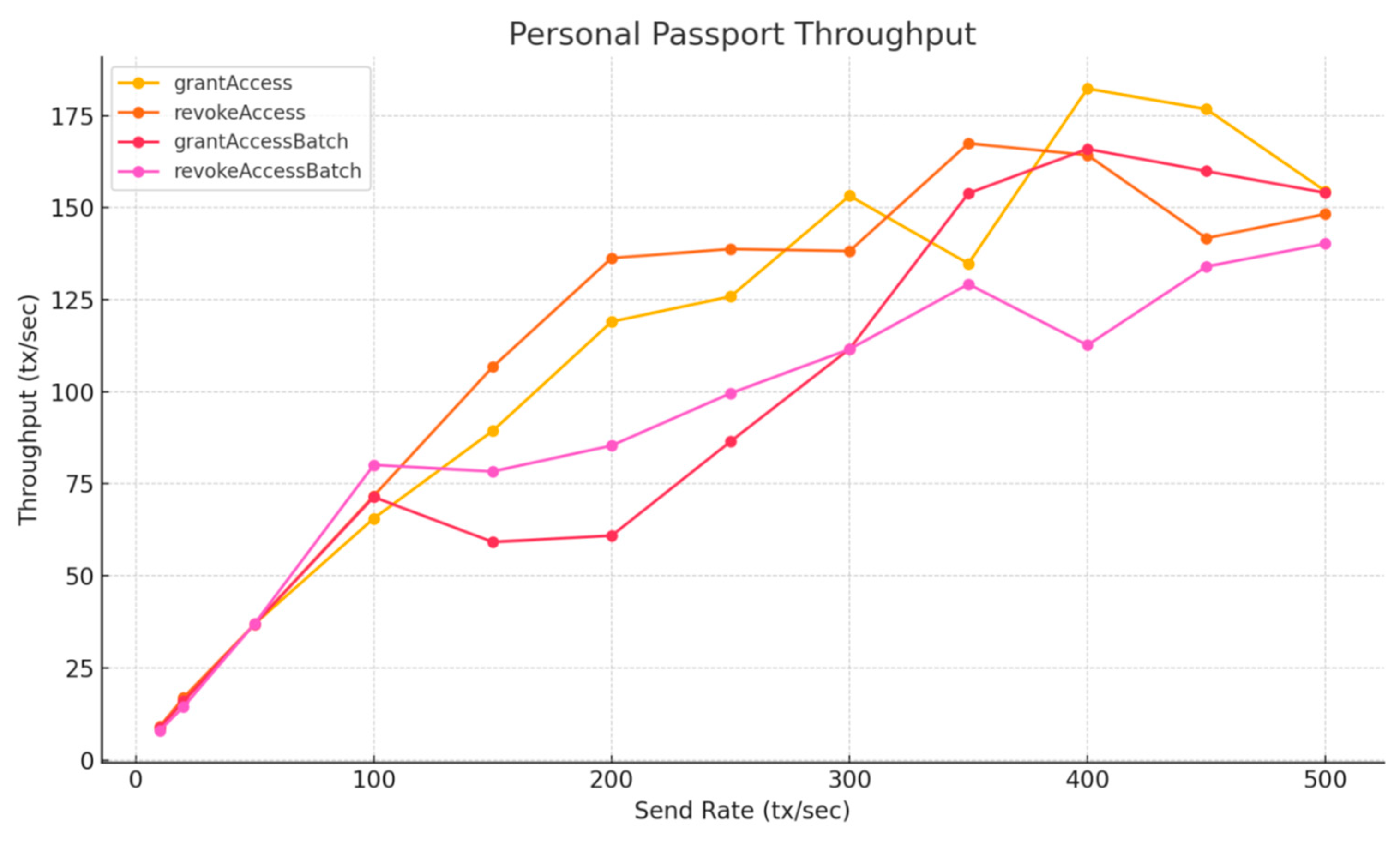

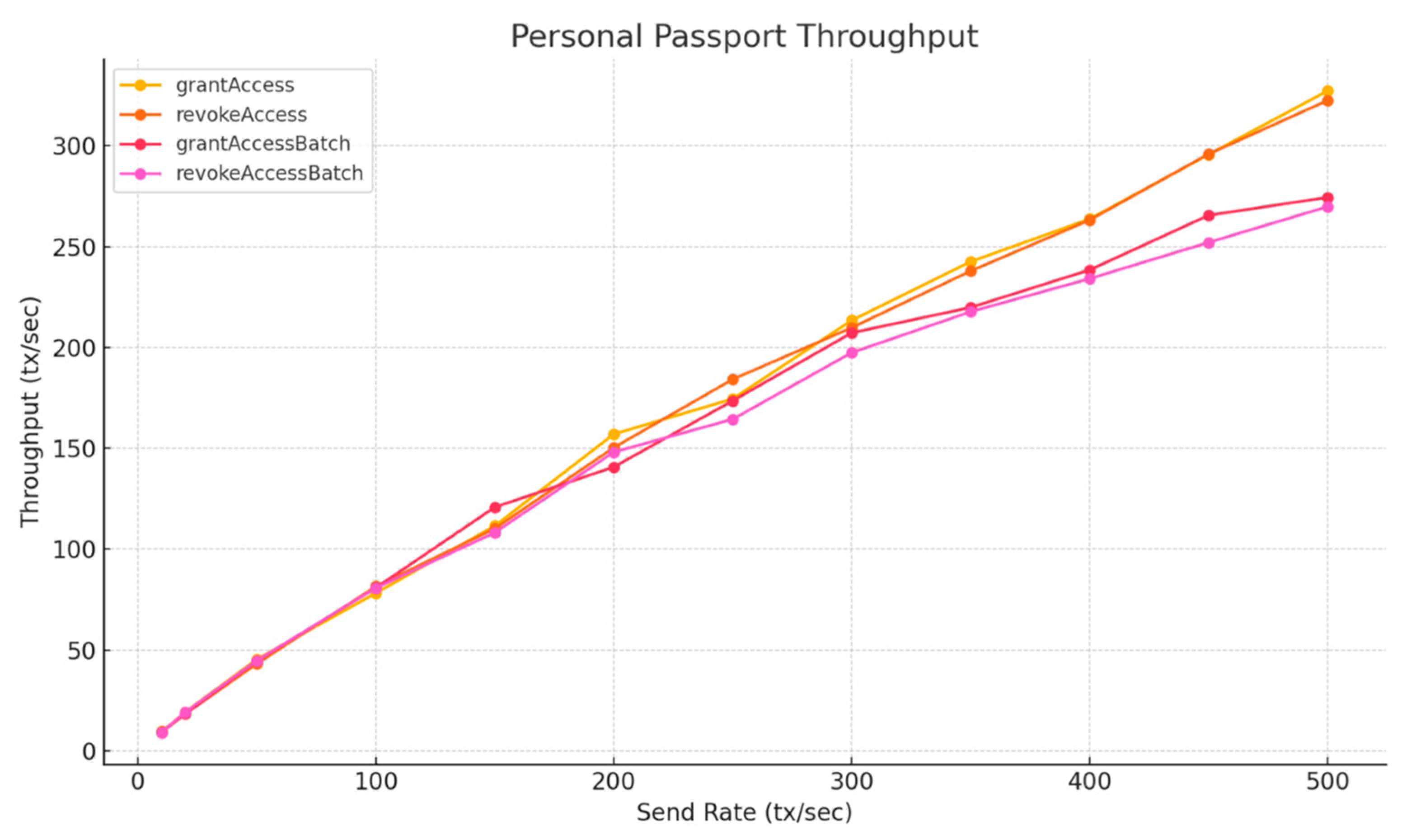

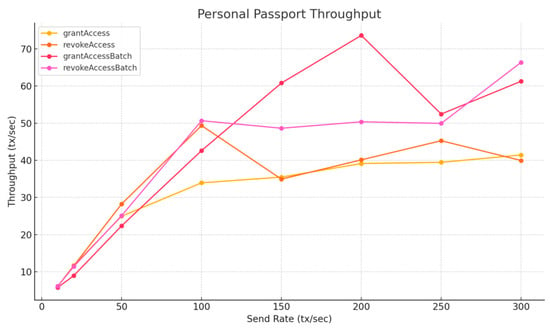

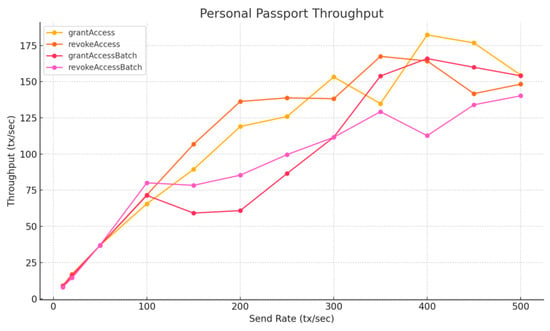

In the Personal Passport contract, we evaluated both single-role and batch-role access control functions. Notably, grantAccessBatch and revokeAccessBatch assigned or revoked five roles in a single transaction (Figure 14). Despite this, their measured throughput remained comparable to the non-batch versions, indicating that batching reduces gas per role but does not significantly improve raw transaction throughput. Future optimizations could explore batching in other parts of the system, such as passport issuance or metadata updates, where aggregated execution might yield greater performance benefits.

Figure 14.

Personal Passport Throughput—Layer 1.

To address scalability limitations, Layer 2 solutions have been increasingly adopted. ZK-Rollup-based platforms such as zkSync Era and Polygon zkEVM have demonstrated the ability to handle thousands of transactions per second [27,28]. Recent measurements from blockchain explorers like Chainspect [29] provide practical reference points for Layer 2 performance. For example, on Arbitrum [30], an Ethereum Layer 2 solution using optimistic rollups, maximum recorded TPS per block reached 6006, with a 100-block average of 1105 TPS. These results confirm that Layer 2 solutions can sustain high throughput, supporting the feasibility of deploying high-volume applications such as cross-border passport systems on public blockchain infrastructure.

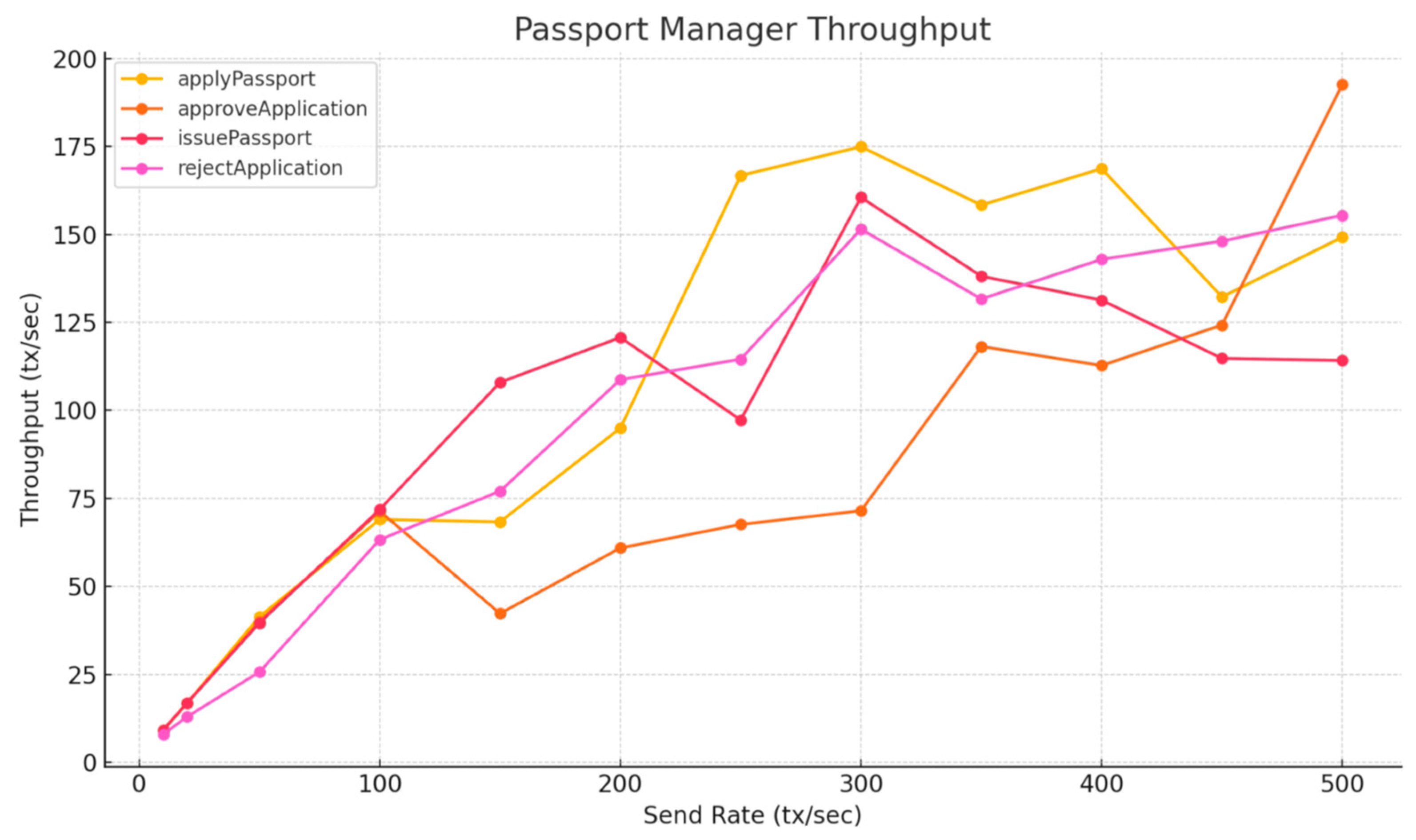

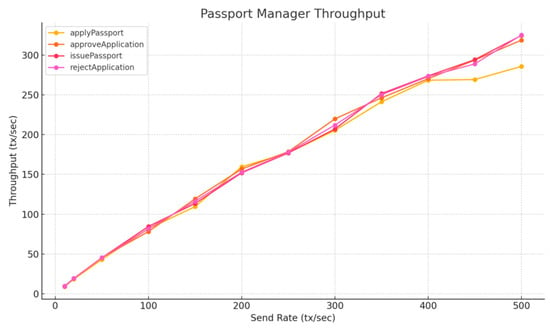

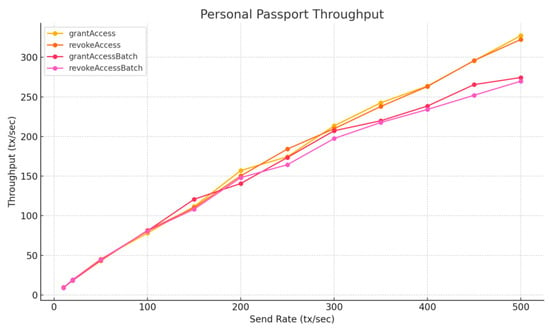

To evaluate scalability on Layer 2, we conducted throughput testing using a local Arbitrum full-chain test node. Compared to the Layer 1 results, Table 8, Figure 15 and Figure 16 show a significant performance improvement across all contract functions. Many functions now exceed 150 TPS under higher load conditions, meeting the system requirements estimated in Section 5.2.2. While these results demonstrate that Arbitrum Layer 2 can support real-world identity workloads, they remain below peak throughput levels observed on public Arbitrum chains, likely due to differences in infrastructure and performance optimizations. Public sequencers benefit from more powerful hardware and tuned configurations, allowing more efficient batching and transaction sequencing [31].

Table 8.

Throughput of each function under varying send rates—Layer 2, Apple M2.

Figure 15.

Passport Manager Throughput—Layer 2, Apple M2.

Figure 16.

Personal Passport Throughput—Layer 2, Apple M2.

To further investigate this performance gap, we benchmarked the applyPassport function on a higher-performance desktop with an Intel i7-12700K processor, compared to the original tests on a MacBook Air M2. Table 9, Figure 17 and Figure 18 show a substantial throughput improvement, reaching up to approximately 300 TPS at 500 tx/s. This confirms that the earlier limitations were primarily hardware-bound and reinforces the conclusion that Layer 2 platforms can reliably meet the throughput requirements of our system in production environments.

Table 9.

Throughput of each function under varying send rates—Layer 2, Intel i7-12700K.

Figure 17.

Passport Manager Throughput—Layer 2, Intel i7-12700K.

Figure 18.

Personal Passport Throughput—Layer 2, Intel i7-12700K.

Integrating our system with Layer 2 infrastructures allows it to overcome the throughput and cost limitations inherent in Ethereum Layer 1. Based on the estimated global demand for passport issuance and usage, a sustained throughput of approximately 70 transactions per second (TPS) is required. Experimental results show that while Layer 1 achieves 40–50 TPS, Layer 2 deployments exceed 150 TPS under standard testing, and can reach up to 300 TPS on high-performance hardware. These findings confirm that the system can reliably support global-scale operations and highlight the feasibility of deploying the proposed architecture in real-world scenarios.

In addition to throughput, response time is a critical performance metric for real-time passport issuance and verification. Response time is defined as the elapsed time between transaction submission and confirmation. Although this study does not directly measure confirmation latency, response time behavior can be inferred from the relationship between transaction send rate and sustained throughput. When the send rate approaches or exceeds system capacity, transactions accumulate in the mempool or sequencer queue, resulting in increased confirmation delays.

The experimental results indicate that Ethereum Layer 1 saturates at approximately 40–50 TPS, implying that higher transaction arrival rates would lead to queue buildup and prolonged response times. In contrast, the proposed Layer 2 deployment sustains significantly higher throughput, consistently exceeding 150 TPS and reaching up to 300 TPS under higher-performance environments. This increased processing capacity effectively mitigates transaction queuing under comparable workloads, thereby reducing end-to-end response times and improving system responsiveness. These results support the claim that the proposed architecture improves not only throughput and cost efficiency, but also response time, making it suitable for latency-sensitive cross-border passport operations.

5.3. Security Analysis

This section analyzes the security properties of the proposed decentralized passport management system, focusing on data integrity, access control, privacy protection, and governance trust assumptions.

First, data integrity and tamper resistance are ensured through the use of Ethereum smart contracts. Passport issuance records, access permissions, and authorization events are stored on-chain, benefiting from Ethereum’s immutability and consensus guarantees. Once recorded, these state transitions cannot be altered without detection, providing strong protection against unauthorized modification or forgery of passport data.

Second, fine-grained access control is enforced through Personal Passport smart contracts, implemented using OpenZeppelin’s role-based access control (RBAC) module. Each traveler is assigned a dedicated contract that implements RBAC, with roles defined as bytes32 constants (typically computed using keccak256 (“ROLE_NAME”)). Roles such as NAME_VIEWER and PHOTO_VIEWER can be granted or revoked individually or in batches via dedicated functions, and access permissions are checked through hasRole. This design ensures transparent, verifiable, and user-controllable authorization over which domains can access specific fields of a passport.

We acknowledge that storing RBAC metadata on-chain, even as hashed constants, may still expose certain information due to public-chain observability. For example, authorization relationships, contract or address mappings, interaction patterns, and transaction timing can potentially be inferred, especially under high-frequency cross-border usage. To mitigate these privacy risks, the system adopts several practical measures: minimizing sensitive information stored on-chain, applying batch operations and timing obfuscation to reduce correlatability, protecting off-chain data access with fine-grained RBAC, encryption, and cryptographic signatures, and randomizing certain transaction patterns where feasible. These measures reduce the risk of metadata-based profiling while preserving auditability, verifiability, and user control over data sharing.

Third, privacy protection is further achieved by minimizing the on-chain exposure of sensitive personal information. Smart contracts maintain verifiable references and access permissions, while sensitive passport data is securely managed off-chain. This approach reduces the risk of large-scale data leakage while preserving auditability and verifiability.

Finally, the proposed governance model mitigates single-authority trust assumptions through a Global Passport Registry deployed on Ethereum Layer 1 and managed via a DAO bootstrapped by ICAO. To operationalize governance in real-world scenarios, the system incorporates explicit mechanisms addressing key risks. Critical actions, such as country onboarding, contract upgrades, and emergency revocation, require multi-signature approval and threshold-based voting among DAO members. Upgrade control is enforced by requiring proposals for smart contract modifications to be reviewed and approved through the DAO before deployment, ensuring that no single entity can unilaterally modify system logic. Emergency revocation procedures enable rapid suspension of compromised roles or contracts, triggered either automatically upon anomaly detection or manually by a quorum of DAO members. Collusion risks are mitigated by distributing decision-making across multiple independent countries and enforcing voting thresholds for sensitive operations. Dispute resolution is handled via a designated arbitration contract or trusted arbitration process, providing a structured pathway for resolving conflicts or disagreements. By specifying event-triggered processes, responsibilities, and access restrictions, the governance framework ensures transparency, accountability, and operational feasibility for cross-border passport management while maintaining compatibility with Layer 2 scalability.

The proposed architecture thus provides a comprehensive set of security guarantees, including data integrity, confidentiality, fine-grained access control, decentralized governance, and privacy-aware metadata handling. Leveraging Ethereum smart contracts and Layer 2 infrastructures, the system avoids single points of control while ensuring that authorization and identity operations remain transparent, verifiable, and privacy-conscious. These security properties collectively support the deployment of the proposed system in real-world cross-border identity and passport management scenarios.

5.4. Comparison with Existing Blockchain Method

This section compares the proposed system with existing blockchain-based passport and identity management solutions, focusing on throughput, response time, and transaction cost. Prior studies commonly adopt permissioned blockchains such as Hyperledger to support digital passports or identity applications [32,33,34]. While such systems can achieve low response times through localized execution, they rely on centralized or consortium-based governance and incur high operational costs due to infrastructure maintenance and limited interoperability. The comparison as shown in Table 10.

Table 10.

The comparison of existing framework and ours.

Public blockchain–based solutions deployed directly on Ethereum Layer 1 provide stronger transparency and decentralization, but their scalability is constrained by limited throughput and high transaction fees [35,36]. As demonstrated in our evaluation, Layer 1 throughput saturates at approximately 40–50 TPS, making it difficult to sustain real-world, high-volume passport operations without congestion and increased confirmation delays.

In contrast, the proposed architecture combines Ethereum Layer 1 governance with Layer 2 execution for passport issuance and access control. Experimental results show that the system consistently sustains over 150 TPS and reaches up to 300 TPS under higher-performance environments, significantly exceeding both Layer 1–based approaches and the estimated system requirement. This higher processing capacity reduces transaction queuing under equivalent workloads, leading to improved response times and substantially lower transaction costs. Compared to existing solutions, the proposed system achieves a balanced trade-off between decentralization, scalability, and operational efficiency, making it better suited for large-scale, cross-border passport deployment.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

This work presents a decentralized passport management system that leverages Ethereum Layer 2 to enable scalable, cost-effective, and user-centric digital identity operations. The proposed system adopts a hybrid architecture in which the Ethereum mainnet serves as a global registry and governance layer, while Layer 2 networks are responsible for handling high-volume operations such as passport issuance and fine-grained access control.

Performance benchmarking conducted on Ethereum Layer 1 shows that key state-changing functions can achieve throughput levels of approximately 40–50 transactions per second. This performance is close to the estimated global system requirement of around 70 TPS, which was derived from an analysis of passport issuance and usage patterns in major regions, including China, the United States, and India. Although these results demonstrate the technical feasibility of the system on Layer 1, large-scale deployment remains impractical due to high gas costs and operational overhead.

To address the inherent scalability limitations of Ethereum Layer 1, this thesis proposes migrating core operational workloads to Ethereum Layer 2. In addition to referencing prior studies showing that platforms such as zkSync Era and Polygon zkEVM can support throughput in the order of thousands of transactions per second, this work provides an in-depth evaluation of the proposed system on Arbitrum. Public blockchain explorer data indicates that Arbitrum can process up to 6006 transactions within a single block, while the peak average throughput over 100 consecutive blocks reaches approximately 1105 transactions per second.

To further validate these observations under controlled conditions, the system was deployed on a local Arbitrum full-chain test environment. Experimental results demonstrate that the system’s core functions can sustain more than 150 transactions per second on a MacBook Air equipped with an Apple M2 processor, and up to approximately 300 transactions per second on a high-performance desktop using an Intel i7-12700K processor. These results confirm that the estimated system requirement of 70 transactions per second—derived from global passport issuance and usage statistics—can be reliably satisfied in realistic Layer 2 execution environments.

Taken together, evidence from both public blockchain measurements and local experimental evaluations demonstrates that Ethereum Layer 2 solutions provide sufficient throughput to support a decentralized passport management system at a global scale. Compared to consortium blockchains, which often achieve higher performance through centralized control, Layer 2 public blockchains preserve decentralization, maintain interoperability with the broader Ethereum ecosystem, and offer greater flexibility for future system extensions. These characteristics make Layer 2 networks a practical and robust foundation for global digital identity infrastructure.

Future work may extend this system in several directions. First, a more comprehensive comparison of Layer 2 solutions—including Optimistic Rollups and Zero-Knowledge Rollups—can be conducted with respect to throughput, transaction cost, latency, and developer ecosystem maturity. Second, cross-Layer 2 interoperability mechanisms may be explored to enable Passport Managers deployed on different Layer 2 networks to share data under a unified global registry. Finally, investigating non-EVM blockchain platforms such as Solana may reveal alternative design trade-offs and opportunities for achieving even higher scalability.

Through this research, we demonstrate that decentralized, user-controlled identity systems are not only conceptually viable but also practically deployable on modern blockchain infrastructure, particularly with the continued maturation of Ethereum Layer 2 ecosystems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.-H.H., B.-Y.L. and S.-M.Y.; methodology, Y.-H.H. and B.-Y.L.; software, Y.-H.H. and B.-Y.L.; validation, Y.-H.H., B.-Y.L. and C.-H.T.; formal analysis, Y.-H.H. and B.-Y.L.; investigation, Y.-H.H. and B.-Y.L.; resources, S.-M.Y.; data curation, Y.-H.H. and B.-Y.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.-H.H. and C.-H.T.; writing—review and editing, Y.-H.H., B.-Y.L., C.-H.T. and S.-M.Y.; visualization, Y.-H.H. and B.-Y.L.; supervision, S.-M.Y.; project administration, S.-M.Y.; funding acquisition, S.-M.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Goel, A.; Rahulamathavan, Y. A comparative survey of centralised and decentralised identity management systems: Analysing scalability, security, and feasibility. Future Internet 2024, 17, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchamia, S.; Byrappa, D.K. Passport, VISA and immigration management using blockchain. In Proceedings of the 2017 23rd annual International Conference in Advanced Computing and Communications (ADCOM), Bangalore, India, 8–10 September 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hyperledger. Hyperledger Fabric. Available online: https://hyperledger-fabric.readthedocs.io/ (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Ethereum. Ethereum. Available online: https://ethereum.org/en/whitepaper/ (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Sguanci, C.; Spatafora, R.; Vergani, A.M. Layer 2 blockchain scaling: A survey. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2107.10881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitwießner, C.; Johnson, N.; Vogelsteller, F.; Baylina, J.; Feldmeier, K.; Entriken, W. ERC-165: Standard Interface Detection. Ethereum Improvement Proposals. 2018. Available online: https://eips.ethereum.org/EIPS/eip-165 (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Nakamoto, S. Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System. 2008. Available online: https://bitcoin.org/bitcoin.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Thibault, L.T.; Sarry, T.; Hafid, A.S. Blockchain scaling using rollups: A comprehensive survey. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 93039–93054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaliasos, S.; Reif, I.; Torralba-Agell, A.; Ernstberger, J.; Kattis, A.; Livshits, B. Analyzing and benchmarking ZK-rollups. In Proceedings of the 6th Conference on Advances in Financial Technologies (AFT 2024), Vienna, Austria, 23–25 September 2024; Schloss Dagstuhl–Leibniz-Zentrum für Informatik: Wadern, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, C. The Path to Self-Sovereign Identity. 2017. Available online: https://www.lifewithalacrity.com/article/the-path-to-self-soverereign-identity (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Schneider, F.B. Least privilege and more [computer security]. IEEE Secur. Priv. 2003, 1, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- STRUCTURE-LDS, L.D. Machine Readable Travel Documents; International Civil Aviation Organization: Montreal, QC, Canada, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- ICAO. Structure of Machine Readable Passport (mrp) Data Page. Available online: https://www2023.icao.int/publications/Pages/ICAO-Journal.aspx?year=2026&lang=en (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Bureau of Consular Affairs. MOFA ROC. Required Documents for Passport Application in Taiwan. Available online: https://www.boca.gov.tw/ (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- USA. Required Documents for Passport Application in United States. Available online: https://travel.state.gov/content/travel.html (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Kingdom, U. Visa Fee Comparison for Different UK Visitor Visa Type. Available online: https://visa-fees.homeoffice.gov.uk/y/usa/usd/visit/all (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Kundra, S.; Dureja, A.; Bhatnagar, R. The study of recent technologies used in E-passport system. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE global humanitarian technology conference-South Asia Satellite (GHTC-SAS), Trivandrum, India, 26–27 September 2014; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pathway, R. How Many Americans Have a Passport. 2023. Available online: https://rusticpathways.com/inside-rustic/online-magazine/how-many-americans-have-a-passport (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Kumar, C. 7.2% of Indians Own Passports, Number Set to Cross 10 Crore Soon. 2022. Available online: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/7-2-of-indians-own-passports-number-set-to-cross-10-crore-soon/articleshow/96326226.cms (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Foundation, N. Hardhat Documentation. Available online: https://hardhat.org/docs (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- OpenZeppelin. Access Control—OpenZeppelin Contracts v2.x. Available online: https://docs.openzeppelin.com/contracts/5.x/access-control (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Chatterjee, A.; Pitroda, Y.; Parmar, M. Dynamic role-based access control for decentralized applications. In International Conference on Blockchain; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, Y.-H.; Guan, X.-Q.; Liao, C.-H.; Yuan, S.-M. Physiological-chain: A privacy preserving physiological data sharing ecosystem. Inf. Process. Manag. 2024, 61, 103761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office, S.C.I. Visa-Free Trips to China Double in 2024. January 2025. Available online: http://english.scio.gov.cn/pressroom/2025-01/15/content_117665551.html (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Analytics, T. U.S. Resident Trips Outbound. 2025. Available online: https://tourismanalytics.com/usoutbound.html (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- The Japan Times. Only 17% of Japanese People Own Passports, Foreign Ministry Says. 2025. Available online: https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2025/02/25/japan/society/japan-passport-holders/ (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Habib, M.A. Analyzing Performance Bottlenecks in Zero-Knowledge Proof Based Rollups on Ethereum. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.22709. [Google Scholar]

- Quattrocchi, G.; Scaramuzza, F.; Tamburri, D.A. The blockchain trilemma: An evaluation framework. IEEE Softw. 2024, 41, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chainspect. Chainspect—Real-Time Blockchain Metrics Dashboard. 2025. Available online: https://chainspect.app/ (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Labs, O. A Gentle Introduction to Arbitrum. 2025. Available online: https://docs.arbitrum.io/welcome/arbitrum-gentle-introduction (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Labs, O. How Arbitrum Works: Transaction Lifecycle. 2025. Available online: https://docs.arbitrum.io/how-arbitrum-works/transaction-lifecycle (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Su, Y.-J.; Hsu, W.-C. Hyperledger Indy-based Roaming Identity Management System. J. Netw. Intell. 2023, 8, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Prajapati, V. Blockchain-Based Decentralized Identity Systems: A Survey of Security, Privacy, and Interoperability. Int. J. Innov. Sci. Res. Technol. 2025, 10, 1011–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, B.C.; Ramakrishna, V.; Govindarajan, C.; Behl, D.; Karunamoorthy, D.; Abebe, E.; Chakraborty, S. Decentralized cross-network identity management for blockchain interoperation, Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Blockchain and Cryptocurrency (ICBC), Sydney, Australia. 3–6 May 2021, IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, A.D.; Mello, T.; Bezerra, W.D.R. Digital identity management system with blockchain: An implementation with Ethereum and Ganache. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.21398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamwal, S.; Cano, J.; Lee, G.M.; Tran, N.H. A survey on Ethereum pseudonymity: Techniques, challenges, and future directions. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2024, 232, 104019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.