Abstract

Advancements in energy storage systems (ESS) are important to attaining a sustainable and resilient energy future. Despite significant advancements in battery technologies, including lithium-ion, sodium-ion, and redox flow batteries, numerous problems remain. These include low energy density, thermal instability, resource scarcity, high lifecycle costs, and ineffective recycling methods. Furthermore, the complexity of connecting battery systems to the grid while maintaining operational safety creates further impediments to implementation. Recent advancements, such as hybrid energy storage systems (HESS), better battery chemistries, and intelligent modeling tools based on MATLAB/Simulink R2025b, have shown promise in terms of performance, cost reduction, and more effective energy management. However, the scalability, recyclability, and real-world applicability of these systems require further exploration. The goal here is to provide a comprehensive overview of current and emerging battery technologies, focusing on technical performance, environmental sustainability, lifecycle cost modeling, and grid compatibility. This comprises a techno-economic study that employs process-based cost modeling (PBCM) and leveled cost of storage (LCOS), a thorough examination of green battery chemistries, and system-level modeling of battery and hybrid configurations. The study seeks to provide academics and stakeholders with a comprehensive framework that considers both the innovations and limitations of current ESS technologies in the context of global decarbonization targets.

1. Introduction

Global electricity demand is projected to rise by one-third by 2040, driven by urbanization and economic growth [1]. Meeting this demand sustainably is a major challenge, as reliance on fossil fuels has already led to resource depletion, pollution, and climate risks [2]. In response, renewable energy sources—particularly photovoltaics (PV)—are increasingly adopted as clean alternatives [3]. However, their intermittent nature makes efficient energy storage systems (ESSs) essential to ensure stable power supply [4].

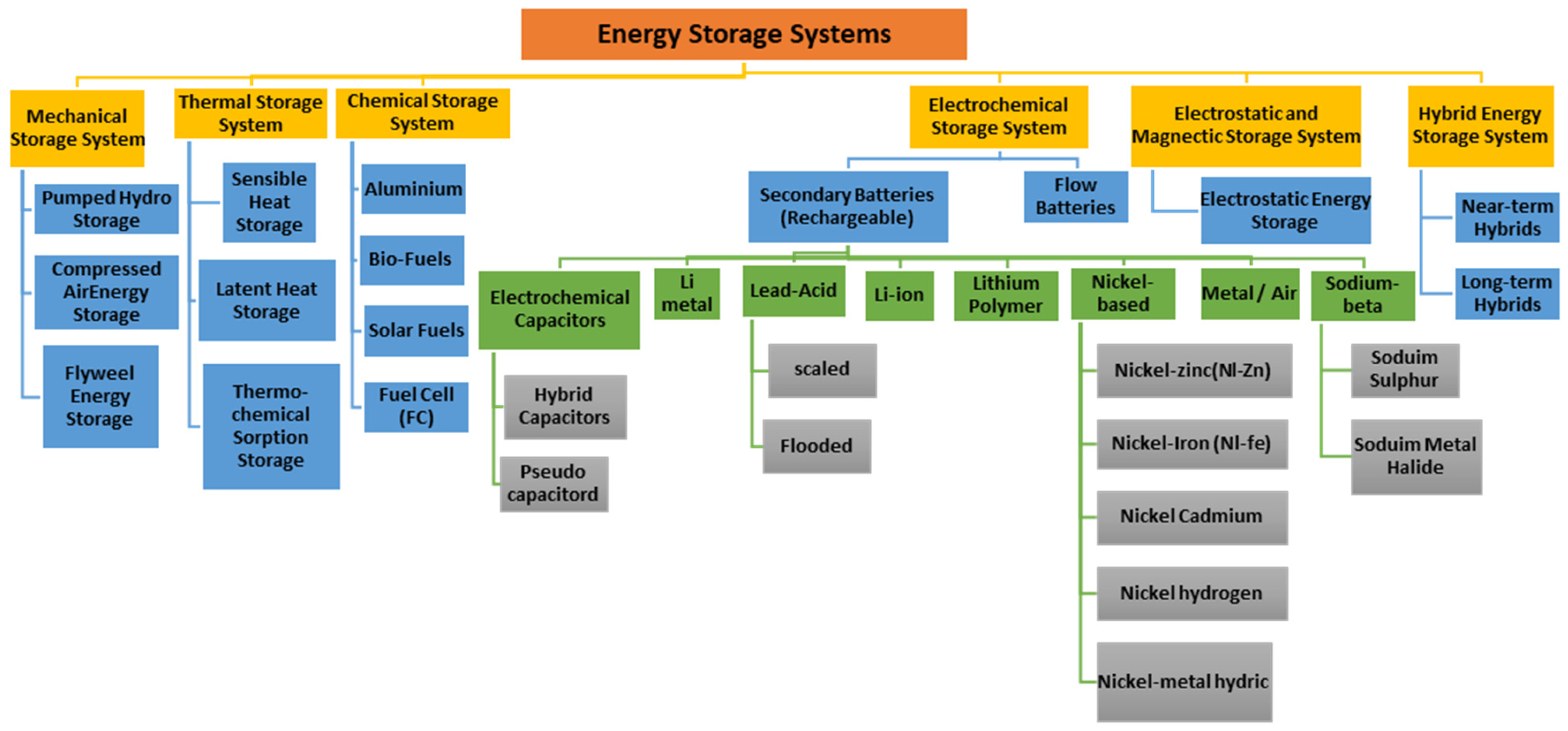

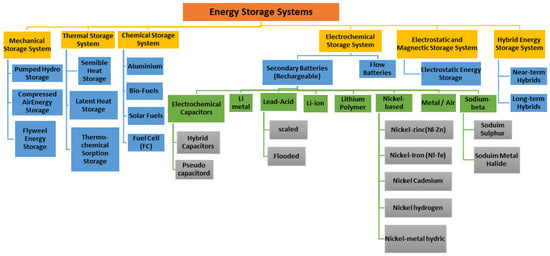

As seen in Figure 1, ESS technologies vary in form, function, and application, ranging from flywheels and pumped hydro storage (PHS) to batteries and supercapacitors. Each has advantages and drawbacks: flywheels offer fast response but high self-discharge [5], while PHS provides large-scale, low-cost storage but is limited by geography. Among electrochemical solutions, batteries remain the most widely used. Lead–acid batteries were the earliest breakthrough, enabling electric vehicles more than a century ago, and lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) now dominate due to their high energy and power density. Traditional ESS, such as batteries, have limitations such as slow charging and short life duration [6]. Battery technology offers efficiency, convenience, reliability, low maintenance, and low cost, but it faces environmental concerns, high costs, and limited shelf life due to demand for essential raw like Lithium (Li) and Cobalt (Co) [7]. High energy density technologies are beneficial for mobile applications, while flow batteries, compressed air energy storage (CAES), and pumped hydro storage (PHS) are vast and high-volume systems. LIBs are extensively utilized because of their capacity, and analyzing their essential features is crucial for selecting the best ESS technology.

Figure 1.

Categories of energy storage systems [8].

Electricity generation and consumption are interconnected, requiring variable demand. ESSs balance supply and demand by storing energy for short to long periods, helping regulate frequency and voltage across local and large-scale power grids. Electrical energy must be transferred into batteries, which are essential storage solutions for intermittent renewable sources like wind and solar. They smooth output and enhance the integration of renewable sources in micro-generation systems.

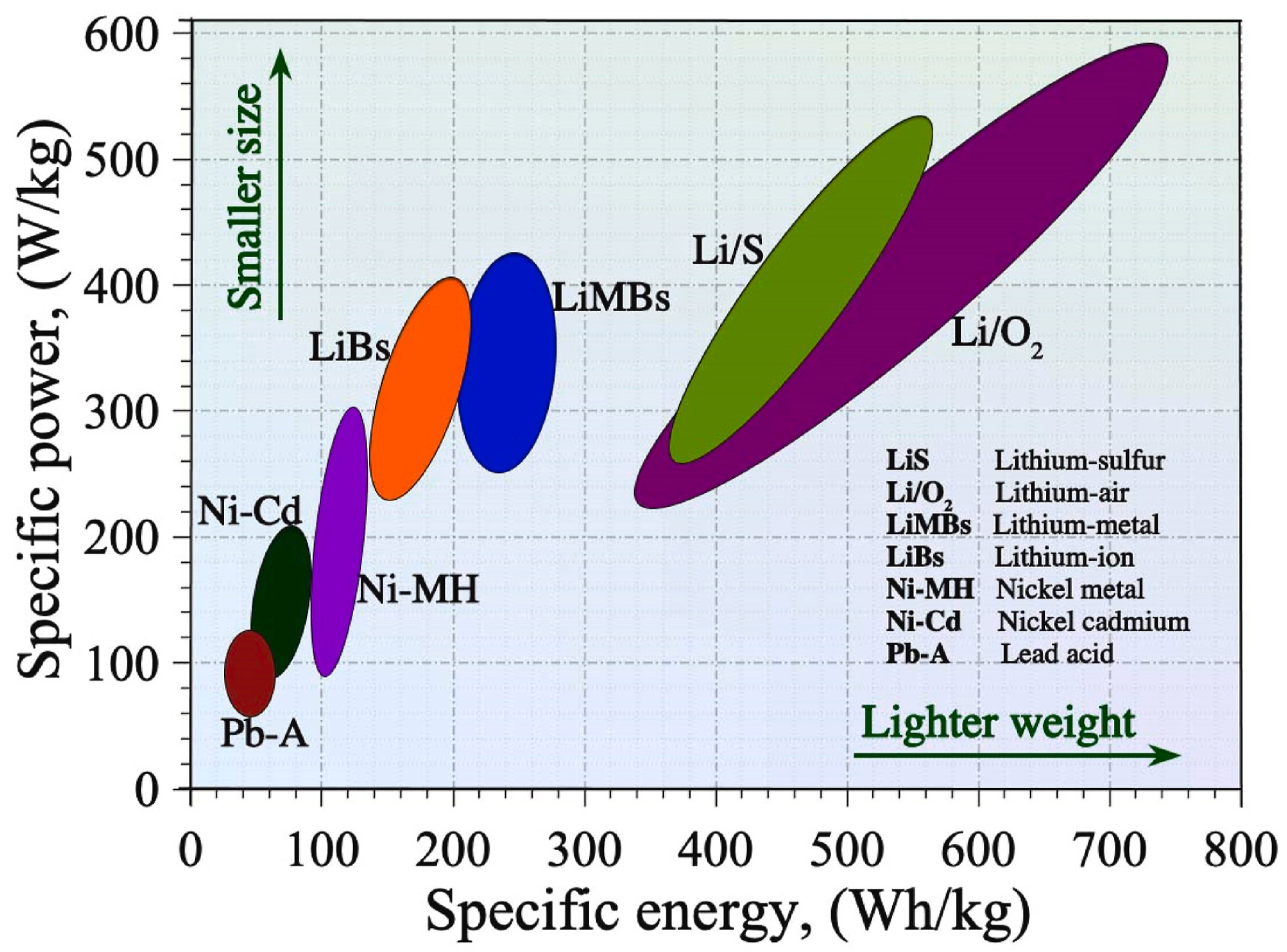

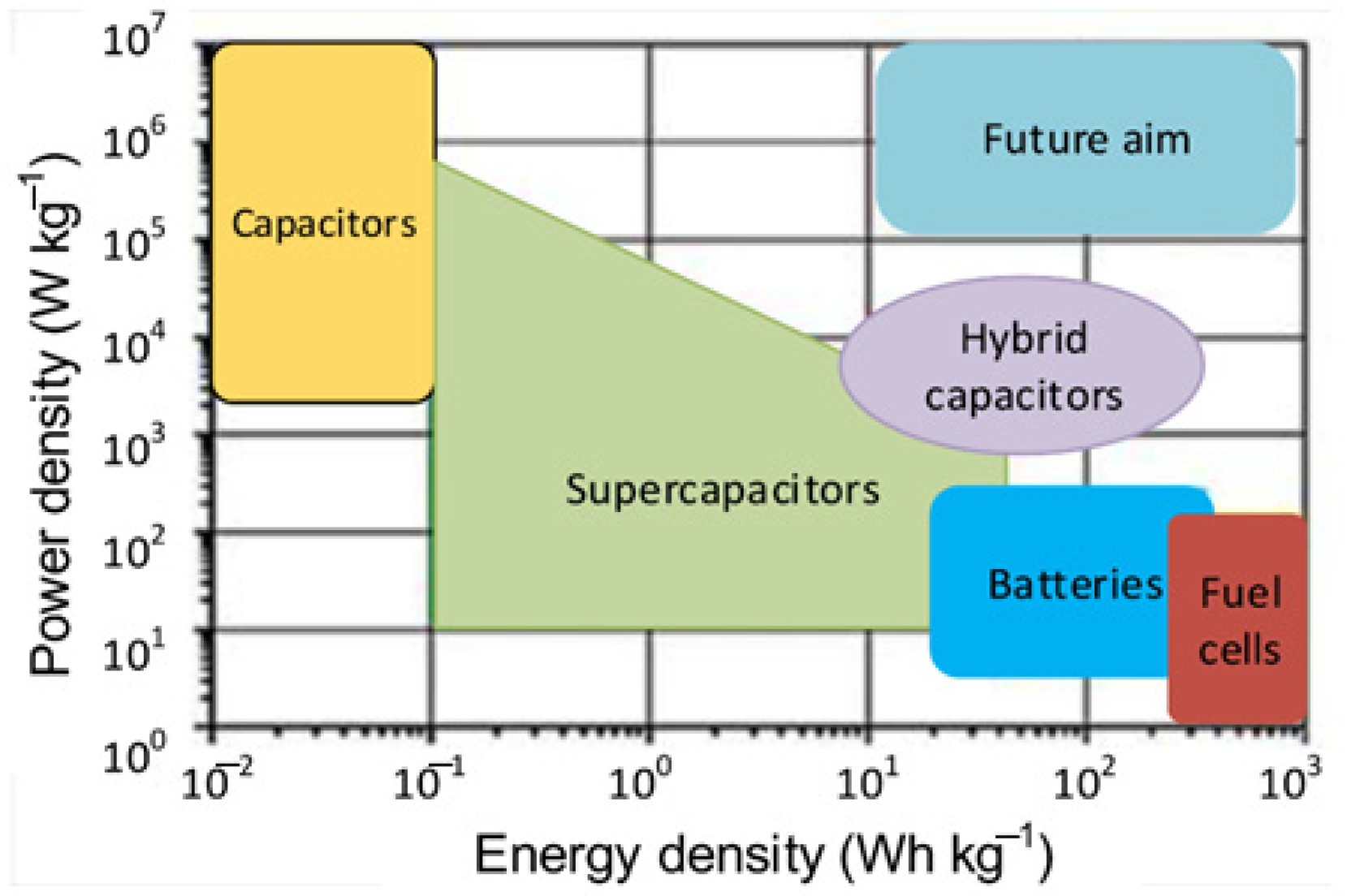

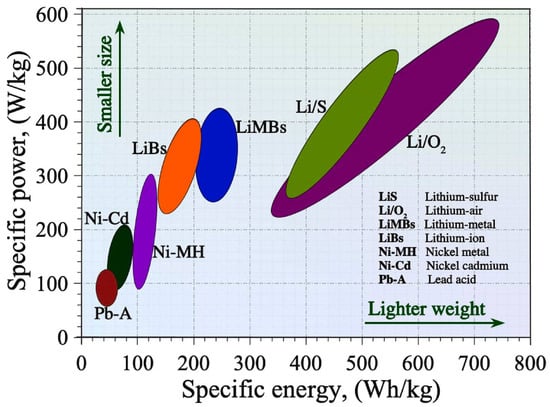

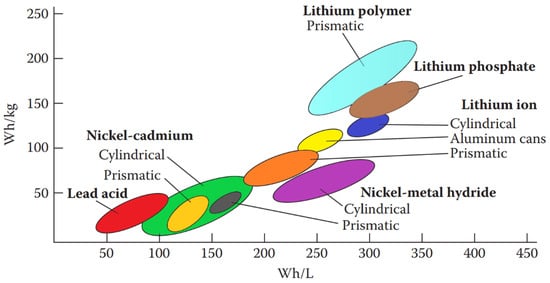

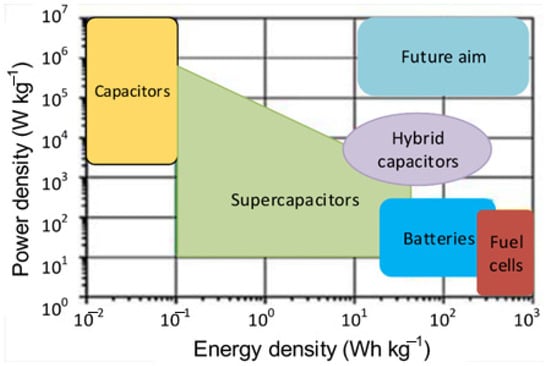

Human society can benefit from sustainable and renewable energy sources, contributing to socio-economic benefits and environmentally friendly development [9]. Rechargeable batteries (RBs), particularly metal-ion batteries like LIBs and futuristic metal-ion batteries like zinc-ion, Mg-ion, Al-ion, and Na-ion, are crucial for deploying green energy sources [10]. They can be used to power electric vehicles (EVs) [11], hybrid electric vehicles (HEVs) [12], consumer electronics, metal–air batteries, and metal sulfur batteries due to their larger energy densities, higher power densities, and longer cycle times [13]. LIBs have superior performance qualities, making them popular for various applications. LIBs provide unrivaled performance qualities, including superior energy and power density, surpassing many frequently used RBs as presented in Figure 2. Lithium–sulfur and lithium–air batteries are considered potential candidates for future applications. The growing demand for LIBs in the mid-1980s drew significant research attention from both governmental and private funding organizations, leading to rapid technological progress and broader commercial adoption. Key applications include consumer electronics and EVs/HEVs, with potential grid-scale stationary energy storage [14]. LIBs confront issues in meeting future electrical energy storage needs in transportation and grid-scale storage due to cost and safety concerns. LIBs currently have higher costs compared to other battery technologies due to the scarcity and increased cost of lithium and other transition metal oxide-based components [15]. This could cause component shortages, higher production costs, and financial challenges [16]. Operational safety is another limitation, as LIBs in EVs and smartphones have been linked to frequent fires and explosions, potentially restricting their wider use [17]. Additionally, batteries can produce significant heat, which can cause parasitic reactions and thermal runaways or short-circuiting [18]. Next-generation battery technology is being developed using readily available raw materials and novel cell architectures to improve cost-effectiveness and safety in a variety of operating scenarios.

Figure 2.

Energy–power density map of rechargeable batteries [19].

The feasibility of physical energy storage is inherently constrained by geographical conditions and the availability of water resources, while electromagnetic energy storage is costly. Chemical energy storage, such as LIBs, sodium–sulfur batteries (NaS), nickel–metal hydride batteries, and vanadium redox flow batteries, is safe, economical, and ecologically beneficial. However, selecting the best battery energy storage approach is challenging, necessitating a detailed assessment methodology for renewable energy generation projects.

ESSs like super capacitors (SCs), Nickel–Cadmium (Ni-Cd), lead–acid, and LIBs are currently available for power quality applications, with flywheels also appearing as promising systems [20]. Flywheels and EC Capacitors are high-power ESS technologies, achieving efficiencies of about 90–95% and 84–97%, respectively. The current efficiency of Diabatic CAES systems is low, but a new plant is expected to achieve 70% efficiency [20]. LIBs have the highest efficiency in electrochemical storage systems, with over 90% or 97% efficiency. PHS systems are known for their high efficiency, ranging from 70–87%, with adjustable speed machines increasing efficiency. Lead–acid batteries have the longest cycle life, but Li-on and NaS can reach more cycles. CAES, PHS, and flywheels offer long lifespans, ranging from 10,000–30,000 cycles, while EC capacitors can achieve approximately 100,000 cycles [21].

ESS converts electrical energy into a storable form and return it to electricity when needed. Pumped Hydro Energy Storage (PHES) is the oldest and most common ESS. Examples include CAES, flywheel energy storage (FES), thermal energy storage (TES), SCs, and batteries. ESSs have been available for a long time.

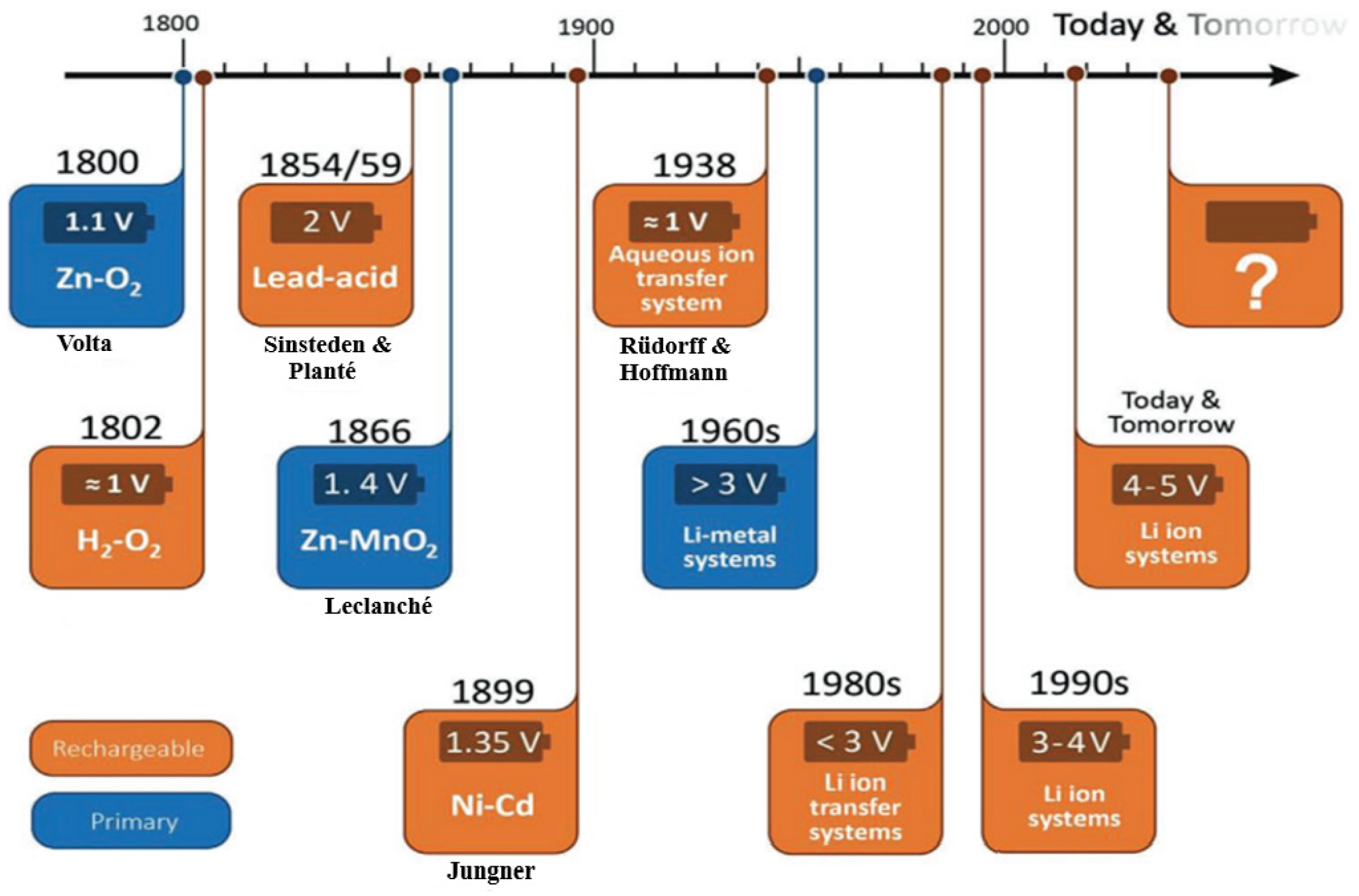

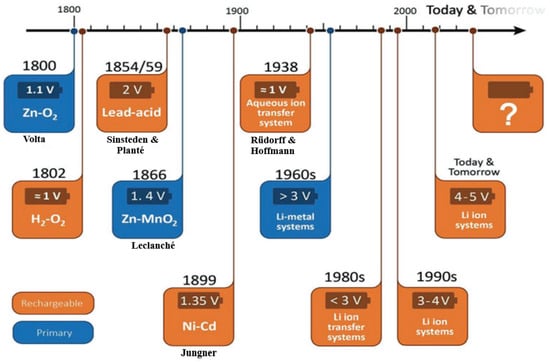

The lead–acid battery, which is a significant breakthrough, facilitated the first electric vehicles 150 years ago and remains dominant in the battery market. Its advancements in the early 1900s led to a technological transition, and the evolution of rechargeable and non-rechargeable batteries in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The development of various battery technologies [22].

Experts anticipate ongoing expansion in battery installations for grid-scale applications, including stand-alone arrays and distributed systems with multiple E-vehicles. Specifications include max power rating, discharge time, energy density, and efficiency, with Table 1 focusing on critical storage capacities of 20 MW.

Table 1.

Chronological order of ESS adopted [8].

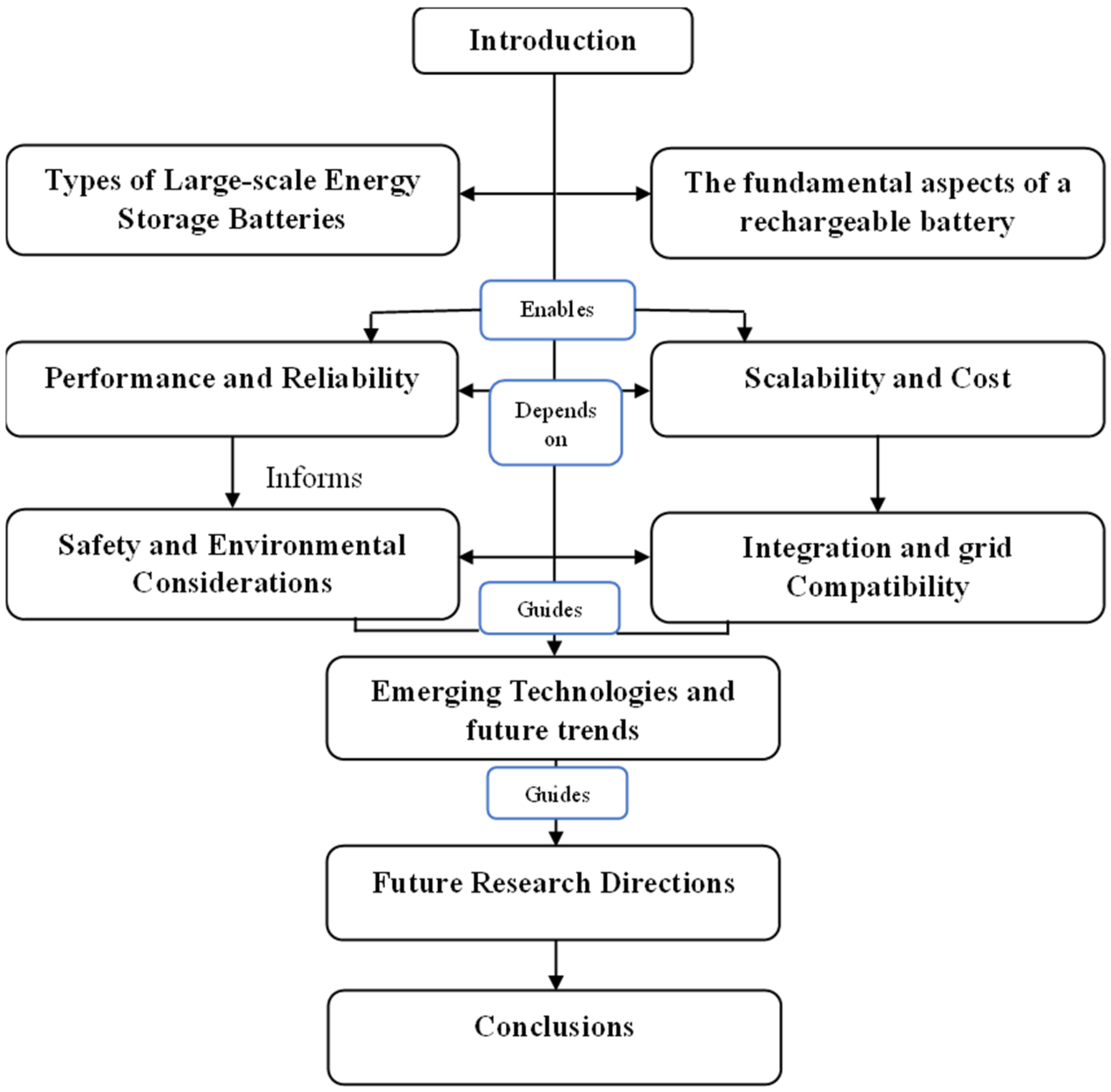

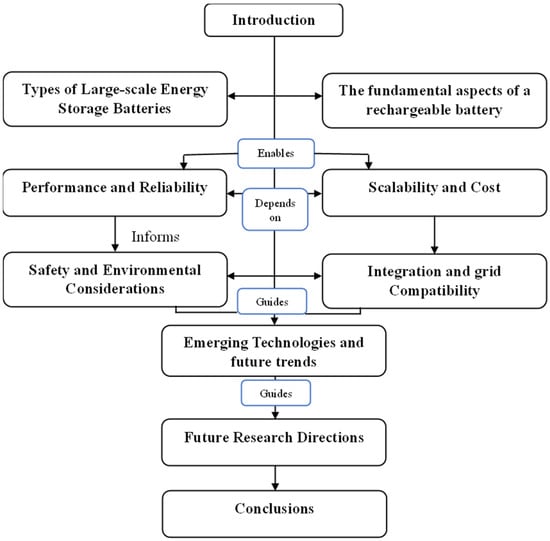

During the second half of the 20th century, technological advancements and electronic and mechanical applications led to a growing demand for batteries with longer operation durations, smaller sizes, lighter weight, rechargeability, high safety, and low cost. This study provides a comparative analysis of various battery types used for large-scale electricity storage, focusing on current operational systems worldwide and their applications. The information flows in the current paper as depicted in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Information flow of the paper.

This review offers a thorough and multidisciplinary examination of battery technologies for energy storage, incorporating both traditional and developing green batteries. Unlike previous research, this study provides a comparative assessment of sustainability, safety, and lifecycle performance while using techno-economic frameworks such as process-based cost modeling (PBCM) and levelized cost of storage (LCOS). An important innovation is the use of MATLAB/Simulink-based battery modeling to simulate nonlinear behaviors and assess grid integration potential. Furthermore, the study discusses hybrid energy storage systems (HESS), including cost-performance comparisons and circuit-level design insights. By addressing technological, economic, environmental, and practical integration issues, this review lays the groundwork for future research and policy in sustainable energy storage systems.

2. Types of Large-Scale Energy Storage Batteries

Batteries can be classified into several types: (1) primary batteries, (2) rechargeable secondary batteries, (3) large-scale energy storage systems such as flow batteries and sodium–sulfur batteries, (4) electrochemical capacitors, and (5) fuel cells. Battery systems store electricity in chemical energy, classified as primary or secondary. Primary batteries are not rechargeable, while secondary batteries can be recharged. They consist of electrochemical cells with positive and negative electrodes. Battery technologies range from lead–acid systems to emerging sodium–sulfur, sodium–nickel chloride, and lithium-ion systems. The lithium-ion system is attracting interest for power systems in consumer electronics like cameras, cellphones, and computers. Lead–acid batteries are known for their affordability, inherent safety features, and high recyclability rates They are utilized in hybrid vehicles for security, power, and emergency flasher systems. Despite their high weight, they remain a potential choice for future advancements.

This section explores various battery technologies like lithium-ion, lead–acid, sodium–sulfur, nickel–cadmium, and flow batteries, highlighting that no single cell type can meet all energy storage needs.

2.1. Primary Batteries

Primary batteries are single-use energy sources that cannot be efficiently recharged due to irreversible electrochemical reactions. Typically designed as dry cells with paste electrolytes, they provide high initial voltage, long shelf life, and low maintenance, making them ideal for portable applications [23]. These batteries are generally classified by their electrolyte type-aqueous or nonaqueous [24].

Common examples include zinc–carbon, alkaline, and lithium cells, which generate electricity through spontaneous redox reactions between two electrodes immersed in an electrolyte. While convenient and inexpensive, primary batteries contribute to raw material depletion and environmental concerns since they are discarded after use. Unlike secondary (rechargeable) batteries, attempting to recharge primary cells can be hazardous, sometimes leading to leakage or explosion.

2.1.1. Zinc–Carbon (Zn-C) Battery

Developed by Georges Leclanché in 1866, the zinc–carbon battery was the first practical dry cell, using a low-corrosive electrolyte and a solid cathode that offered low self-discharge. These inexpensive and widely used batteries were valued for their simplicity, moderate energy density, and reliability. A typical Zn-C cell includes a zinc container (anode), a graphite rod (cathode), and an electrolyte of ammonium chloride or zinc chloride [25].

Despite their affordability, Zn-C batteries have limited energy density, poor leakage resistance, and voltage drop during discharge [23]. Their extensive use has also raised environmental concerns, and made proper collection and recycling essential to reduce pollution [26]. Although once dominant in the market, their use has steadily declined with the rise of alkaline batteries.

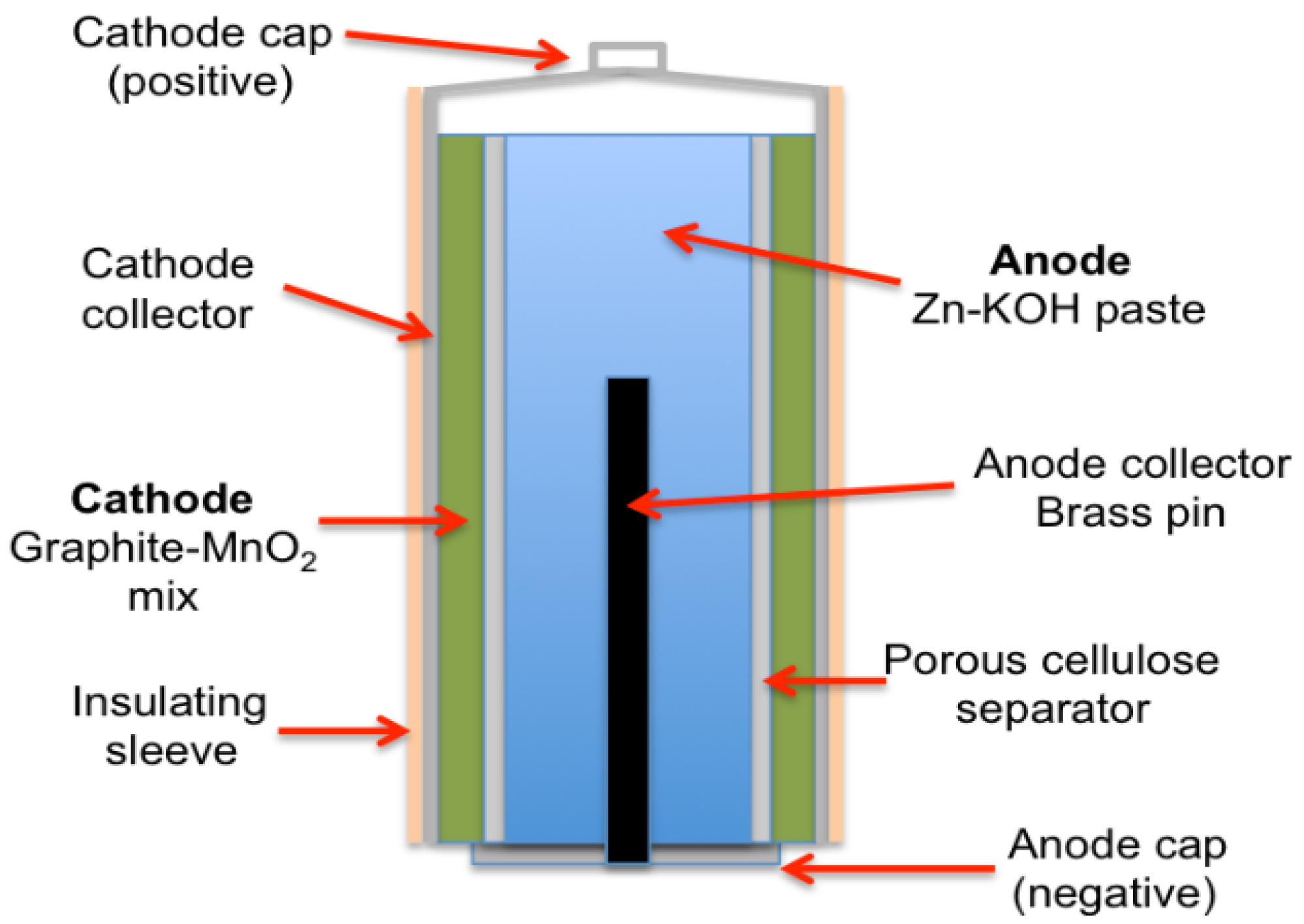

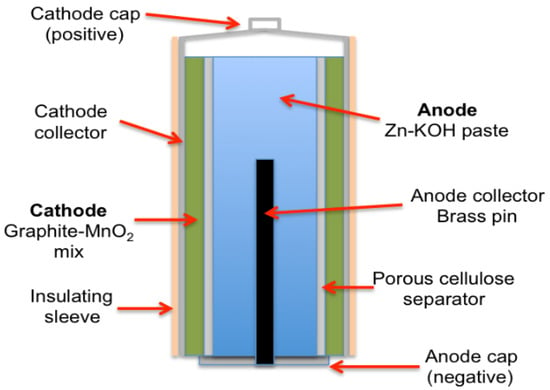

2.1.2. Alkaline Battery

After years of development, Eveready Battery Branch introduced the ‘Energizer’ brand in 1980 [27]. Founded by Urry, who passed away in 2004, the brand continues to enhance performance and reliability globally, focusing on the development of alkaline batteries that offer long discharge times, extended storage life, and leakage-proof performance [27]. Alkaline batteries are one of the basic batteries that are still frequently used today. Figure 5 illustrates the schematic diagram of an alkaline battery. The market for primary batteries has largely moved toward Zn/Alkaline/MnO2 technologies, which outperform Zn-C batteries by two to ten times, due to their prevalent chemistries [23], and has inexpensive cost, abundant materials, low toxicity, and excellent working potential [28]. This alkaline cell features zinc as the anode and manganese dioxide as the cathode, utilizing potassium hydroxide as the electrolyte [29]. Alkaline zinc-manganese oxide batteries are versatile and suitable for various applications such as audiovisual equipment, digital cameras, portable TVs, shavers, office appliances, and game equipment.

Figure 5.

Alkaline battery structure.

2.1.3. Lithium Primary Batteries

Research on lithium primary batteries (LPBs) is less intensive than rechargeable batteries, despite their widespread use in various sectors like military, aerospace, medical, and civilian [30]. LPBs, developed in the late 1960s, are chemical power sources with long lifetimes, high volumetric energy, and reliable anti-leakage performance [31], offering higher energy density, higher operating voltage, and wider temperature range. They consume less feedstock and are widely sourced, making them environmentally friendly [32]. Their active materials are also non-toxic, making them a significant development for high energy density.

LPBs have been widely used, including lithium–sulfur dioxide, lithium–thionyl chloride, lithium–manganese dioxide, and lithium–carbon fluoride. However, hurdles remain in enhancing energy density, rate capability, and electrochemical performance in severe environments. The lithium–air battery, a new lithium primary cell, has five to ten times the energy density of typical Li-ion batteries [33].

2.2. Secondary Batteries

Secondary batteries are rechargeable batteries used for automotive ignition, portable electronics, and powering electric and hybrid vehicles [23]. As homes generate their electricity, they are becoming popular for residential power storage [34]. The commercialization of secondary cells was enabled by electrodes capable of multiple deep charge/discharge cycles [35], often using lead–acid, lithium-ion, nickel–metal hydride, or nickel–cadmium electrodes [36]. This section organizes secondary battery technologies into three main groups: established technologies, high-temperature and large-scale grid options, and emerging or alternative chemistries. Each group is analyzed with respect to performance, scalability, cost, safety, and sustainability.

2.2.1. Established Technologies

- a.

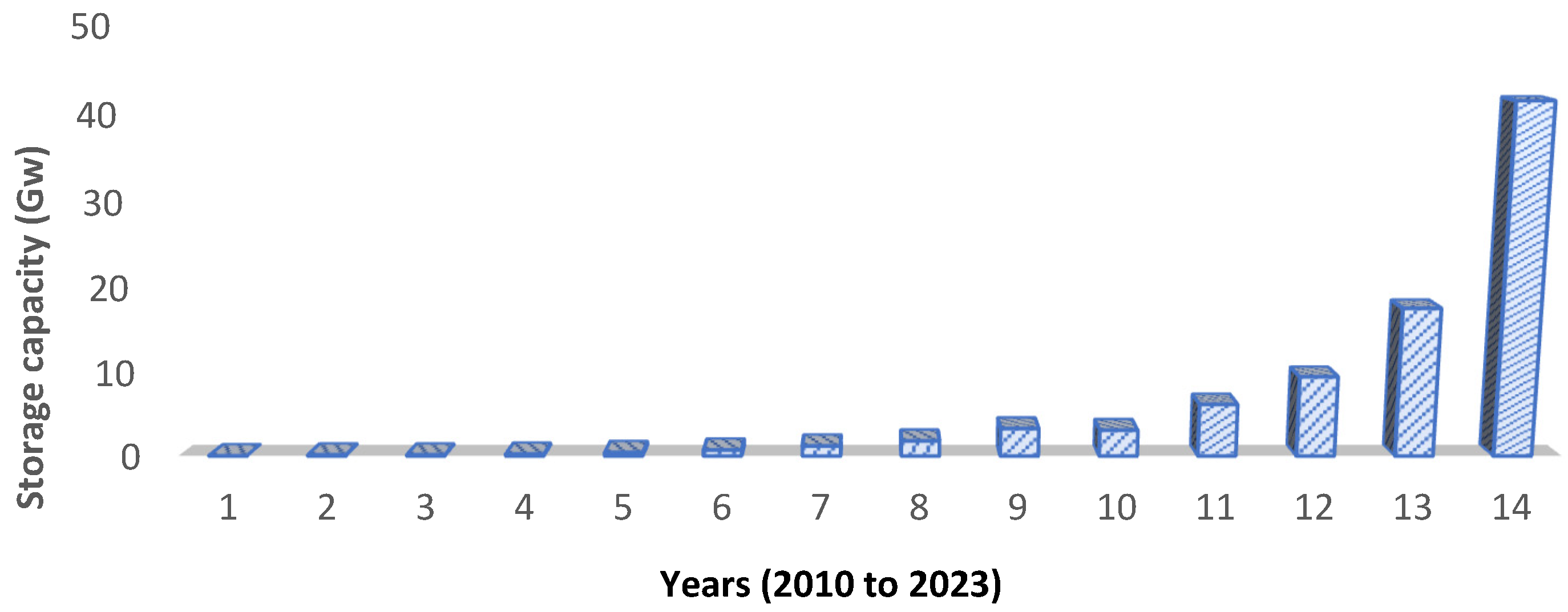

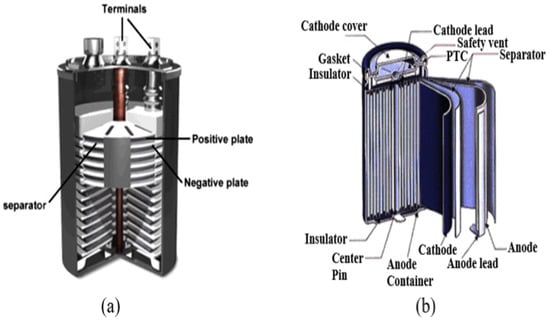

- Lead–acid battery

Lead–acid (Pb-A) batteries are the earliest form of rechargeable batteries, relying on a liquid electrolyte for operation in Figure 6a and are commonly used in ESS [37]. The battery consists of multiple stacks of negative and positive plates, a plate-shaped base with a plug and nut, and positive and negative terminals at the top. They consist of a lead dioxide (PbO2) cathode and a lead (Pb) anode, and an electrolyte containing sulfuric acid. It offers quick response time, low self-discharge rates, high cycle efficiency, and low costs [38]. It is a backup power source in telecommunication, energy management, microgrids, and isolated electricity systems. Technology has limitations including limited cycle life, low specific energy, reduced energy density, and diminished efficiency in cold environments [39]. The chemistry of Pb-A batteries can be adapted for use in grid energy storage applications by altering electrode structures, with research focusing on extending cycle life durability and specific power in lead–carbon electrodes [40], which can be beneficial beyond stabilization applications. Carbon is added to negative electrodes in typical lead–acid batteries to increase specific power and reduce sulfation during charging cycles [41]. This significantly increases cycle life by up to ten at high rates, ensuring deep discharges with long cycle life [42]. This technique is especially effective in applications that require deep discharges and long cycle life. Pb-A batteries remain the preferred choice for automobile starting, lighting, and ignition due to their affordability and exceptional performance [43].

Figure 6.

(a) Structure of a Pb-A battery and (b) structure of a LIB [5].

- b.

- Nickel–metal hydride (Ni-MH) batteries

Ni-MH batteries, which were initially invented in 1986 and made commercially available in 1989, are critically rechargeable batteries used in power tools, hybrid automobiles, electric vehicles, and by major automotive manufacturers. They include a nickel hydroxyl oxide cathode, a metal hydride anode, a KOH electrolyte, and a separator [22,37]. Ni-MH batteries provide high energy density, temperature, and rate capabilities, long cycle and shelf life, and fast charging. They are more expensive than Pb-A, have lower specific energy and power density, and operate poorly at low temperatures [23]. They have a high self-discharge rate, up to three times faster than Ni-Cd and Li-ion batteries, causing them to lose about one-third of their stored charge in a month. They are suitable for portable items, electric vehicles, and industrial spare devices, but have a high self-discharge rate of 5% to 20%.

- c.

- Nickel–cadmium (Ni-Cd) batteries

Ni-Cd battery systems, previously popular in power tools and portable gadgets, have been phased out due to concerns related to cadmium toxicity and challenges in recycling. These concerns impede the development and certification of future large-scale storage systems based on Ni-Cd technology, which was once the dominant technology in these industries [39]. Ni-Cd batteries are utilized in phones, toys, and hand tools [37], while cadmium electrodes have a larger capacity [37]. They have a long cycle life, are durable, have good charge retention, perform well in long-term storage, require little maintenance, and discharge flatly. However, they have a low energy density, a high cost, and significant memory effects [23]. Cadmium is a hazardous metal, and most Cd in municipal solid waste comes from abandoned Ni-Cd batteries [40].

2.2.2. High-Temperature and Grid-Scale Batteries

- a.

- Sodium–sulfur (NaS) Battery

NaS batteries are rechargeable, high-temperature devices used for large-scale energy storage, with advantages such as load balancing, power quality, peak shaving, and sustainable energy management. Molten sodium and sulfur electrodes are used, with beta alumina serving as the solid electrolyte, operating at a temperature of 574–624 K to maintain electrode liquidity. NaS batteries have high energy densities, capacity, and zero self-discharge [4]. They have high recyclability due to their use of cheap materials. However, they have high operation costs and additional temperature control systems. However, due to high operating temperatures and corrosive sodium polysulfide discharge products, it is best suited for large-scale, non-mobile grid energy storage [5]. ZEBRA (ZEolite Battery Research Africa) cells, a type of sodium/metal chloride cell, operate at high temperatures, use a negative sodium-composed electrode, and separate it from the positive electrode using a ceramic electrolyte [44], similar to sodium/sulfur cells in terms of their characteristics.

- b.

- Sodium–nickel chloride battery

The sodium–nickel chloride battery (NaNiCl2) is a low-cost, high-performance battery made of liquid sodium and solid ceramic electrolyte. It has a long cycle life, good charge retention, and requires little maintenance [23]. However, it has low energy density, high cost, and significant memory effects. Cadmium, a hazardous metal, is often found in municipal solid waste from abandoned Ni-Cd batteries [40]. ZEBRA batteries are ideal for city fleets and delivery services, but their usage in personal automobiles is challenging due to low daily mileage and thermal losses [45].

2.2.3. Emerging and Alternative Chemistries

- a.

- Lithium-ion batteries

LIBs dominate the market for both portable electronics and emerging grid-scale applications, owing to their superior energy density and design flexibility. Their performance strongly depends on material combinations and electrode design, which must balance between high energy output, safety, and thermal stability [36]. Figure 6b illustrates the structure of the LIBs which is made of lithium metal oxide and graphitic anode material. Despite their advantages, LIBs face critical challenges: high production costs, sensitivity to deep discharge, and reliance on advanced battery management systems [46]. Their economic feasibility in large-scale applications hinges on manufacturing advancements and cost reductions [47,48]. Commercial chemistries vary; LCO offers high density but poor lifespan, LFP delivers thermal stability with moderate capacity, while NCA and NMC balance energy and power density for automotive uses [42,49,50].

Table 2 summarizes these characteristics.

Table 2.

A comparison of lithium battery voltages and applications.

However, LIBs suffer from capacity fading due to parasitic reactions, increasing internal resistance and reducing lifespan [51,52,53]. This degradation links closely to the behavior of the solid electrolyte interphase [54], impacting state of health (SOH) and performance predictability [55]. Material sourcing also raises sustainability concerns, with cobalt, nickel, and lithium recycling posing environmental and economic challenges [56]. Moreover, LIBs require strict operational controls to prevent imbalance and safety issues.

- b.

- Lithium–sulfur (Li-S) batteries

Li-S batteries, despite their high theoretical capacity and low cost due to sulfur abundance [57], face limitations such as capacity loss, low coulombic efficiency, low volumetric density, high internal resistance, self-discharge, and rapid capacity fading [58]. Innovative design of these cells can mitigate these drawbacks, making them a subject of interest.

- c.

- Nickel–zinc (Ni-Zn) batteries

Ni-Zn batteries are compact, portable power sources that discharge quickly and cost less than Li-ion batteries. They can replace Ni-Cd and NiMH batteries in the majority of applications [7] due to their high specific power, efficiency, and minimal environmental effect [59]. However, they have disadvantages, such as self-corrosive zinc, a tendency to dry out, and poor discharge after numerous cycles [59].

- d.

- Sodium-ion (Ni-B) batteries

A sodium-ion battery (NIB, SIB, or Na-ion battery) is a rechargeable battery that uses sodium ions (Na+) as charge carriers. In some cases, its working principle and cell construction are similar to those of lithium-ion battery (LIB) types, simply replacing lithium with sodium as the intercalating ion. Sodium belongs to the same group in the periodic table as lithium and thus has similar chemical properties. However, designs such as aqueous batteries are quite different from LIBs. SIBs received academic and commercial interest in the 2010s and early 2020s, largely due to lithium’s high cost, uneven geographic distribution, and environmentally damaging extraction process. Unlike lithium, sodium is abundant, particularly in saltwater [60]. Further, cobalt, copper, and nickel are not required for many types of sodium-ion batteries, and abundant iron-based materials work well in batteries [61].

In summary, each secondary battery technology presents a distinct balance of performance, cost, and application specificity. Lead–acid and NiMH batteries remain viable for legacy or budget-conscious applications, while LIBs dominate high-performance sectors such as EVs and grid-scale storage. High-temperature options like NaS and NaNiCl2 are promising for stationary applications but face operational and safety hurdles. Emerging chemistries such as Li-S and Ni-Zn offer potential long-term advantages but require further development. Moving forward, innovation in materials, cost reduction strategies, and safety management will be key to optimizing these technologies for a broad spectrum of energy storage needs.

3. The Fundamental Aspects of a Rechargeable Battery

A rechargeable battery consists of voltaic cells with two half-cells, where negatively charged anions migrate to the anode electrode and positively charged cations to the cathode, separated by an ionized electrolyte medium for ion production and transport.

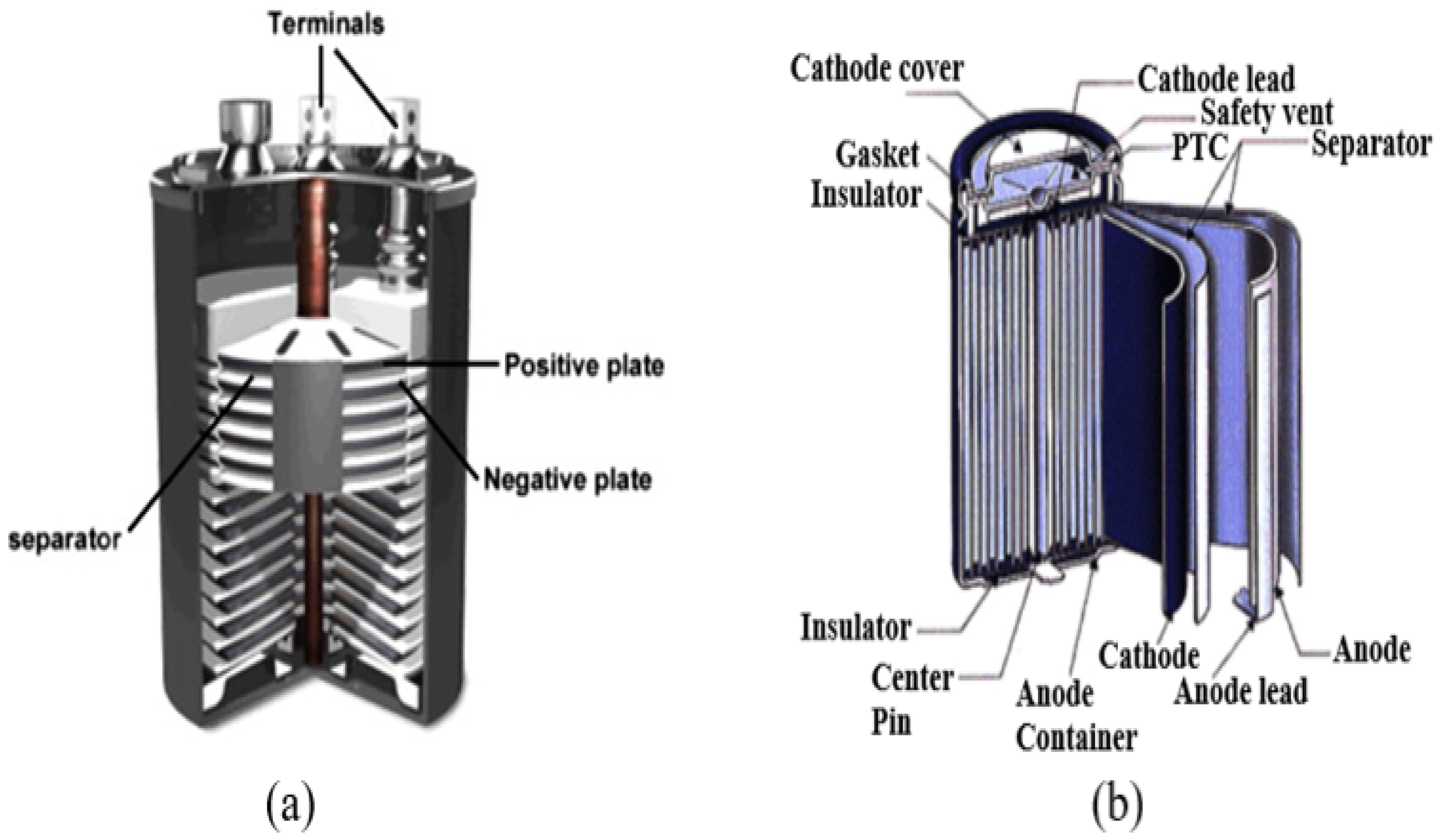

Battery designs might include half-cells with distinct electrolytes and separators to prevent mixing. Many cells allow ions from carbon–zinc (C-Zn), Ni-Cd, and Li to pass through them. Key factors determining the performance of rechargeable batteries include their energy density and power density. The electrolyte acts as a conduit for ion movement between the electrodes. However, in Pb-A batteries commonly used in vehicles, it is also involved in the electrochemical reaction. Figure 7 depicts the y and x axes of these parameters.

Figure 7.

Rechargeable batteries specific power (Wh/kg) and energy density (Wh/L) graphic.

The research aims to improve the design of nickel–zinc rechargeable batteries with low transportation costs. Critical electrical factors such as state of charge (SOC), thermal runaway, charge and discharge rates, discharge cutoff detection, and the relationship between SOC and open circuit voltage (OCV) are important to consider.

High-capacity batteries serve diverse applications, while low-power ones suit portable devices. Advances in miniaturization and nanotechnology are key to developing reliable, compact, and durable next-generation rechargeable batteries. These batteries operate by reversing chemical reactions during discharge [62]. with key traits like energy density and power per unit mass or volume. Various types are available, meeting specific user needs [45].

3.1. Capabilities of Rechargeable Batteries in Commercial Applications

Commercial applications often choose rechargeable power batteries based on their specific energy, longevity, self-discharge, and specific power. Cycle life depends on battery treatment or usage. Li cells exhibit a linear decrease in anode voltage, while Ni-MH batteries may suffer memory loss, and zinc–air cells were initially used as EV and HEV prototypes.

Rechargeable batteries are more expensive than disposable batteries, however, they are substantially less expensive when split by the number of recharge cycles, which includes a battery charger, than the total cost of several primary cells for Ni-MH, Ni-Cd, and LIBs. However, some battery applications necessitate long dormancy periods and few replacements, rendering certain rechargeable battery technologies unsuitable due to their high self-discharge rate in comparison to non-rechargeable batteries. In this scenario, primary cells are more cost-effective than rechargeable batteries, which only consume a small portion of the possible recharge cycles.

3.2. Current Challenges of Battery Energy Storage System

Despite its many advantages, battery energy storage systems (BESS) face several challenges. Such as; cost, battery lifespan, safety concerns, recycling, end-of-life management. The high upfront cost of BESS remains a significant barrier to widespread adoption, although prices are gradually decreasing. The lifespan of batteries is limited by the number of charge-discharge cycles they can endure. Degradation over time can reduce system efficiency and increase maintenance costs. The use of large-scale battery systems raises safety concerns, including the risk of thermal runaway and fires. Robust safety measures and advancements in battery technology are essential to mitigate these risks. As the roll-out of BESS grows, so does the need for effective recycling and end-of-life management solutions to address environmental and resource concerns. BESS offer significant advantages in promoting renewable energy and ensuring grid stability, but they also face challenges such as high costs and technical limitations. By overcoming these hurdles, these systems can play a vital role in the global transition to sustainable energy.

4. Performance and Reliability

The rapid expansion of portable electronics, electric vehicles, and renewable energy integration relies heavily on dependable energy storage systems (ESS). However, battery aging and degradation significantly affect efficiency, safety, cost, and sustainability [63]. Improving reliability requires a clear understanding of failure mechanisms and aging processes.

Key strategies include electrical, thermal, chemical, and postmortem analyses [64], simulating aging based on temperature, SOC, depth of discharge (DoD), and C-rate factors [65], as well as advanced data analytics and AI for failure prediction [66].

Accurate diagnosis enables better system design, maintenance planning, and prediction of remaining useful life.

Battery management systems (BMS) play a central role in monitoring state of health, balancing cells, and managing heat. Since rapid charging accelerates degradation, optimizing fast-charging strategies is also essential. Safety remains a priority, with abuse testing and advanced BMS integration helping to prevent hazards and ensure safer cell designs.

5. Scalability and Cost

Scalability and cost remain decisive factors in evaluating the feasibility of battery technologies for energy storage. They determine both the competitiveness of a given system and its potential for large-scale deployment.

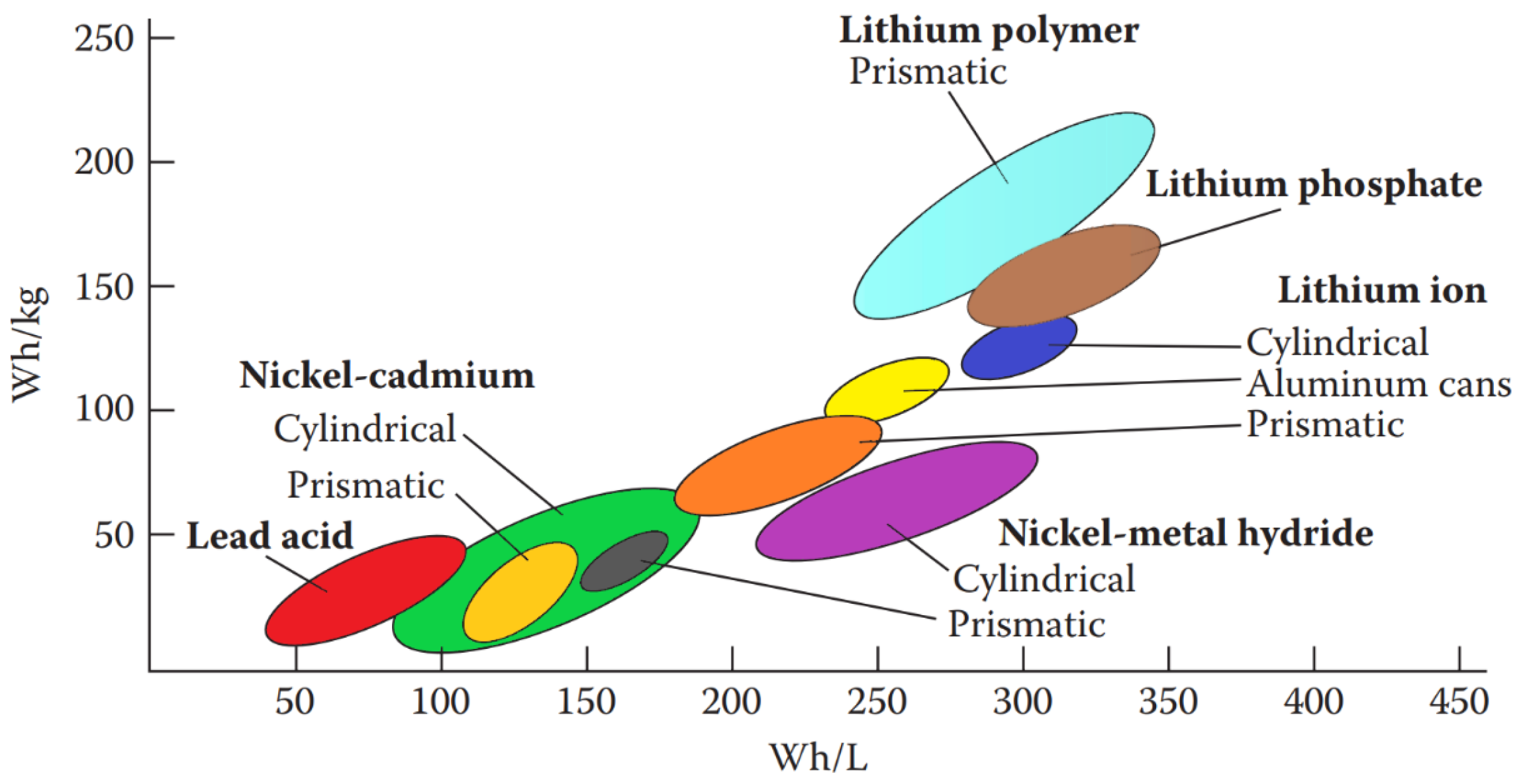

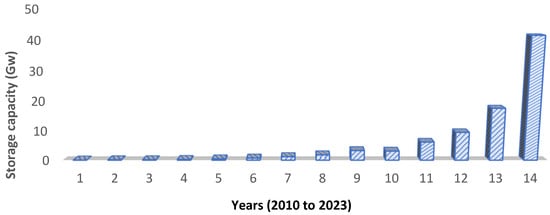

5.1. Scalability

Scalability refers to how easily a technology can be deployed across different levels—ranging from small household systems to large-scale grid applications. This depends on production capacity, industrial flexibility [67], and achievable volumes [68]. While some chemistries are well-suited for small-scale use [69], others are better adapted for large-scale deployment due to their higher energy density and durability [70]. BESS are particularly versatile, as they can be customized and expanded over time to meet rising energy demand. Figure 8 shows the steady growth in global battery storage capacity between 2010 and 2023.

Figure 8.

Global battery storage capacity additions between 2010 and 2023 [71].

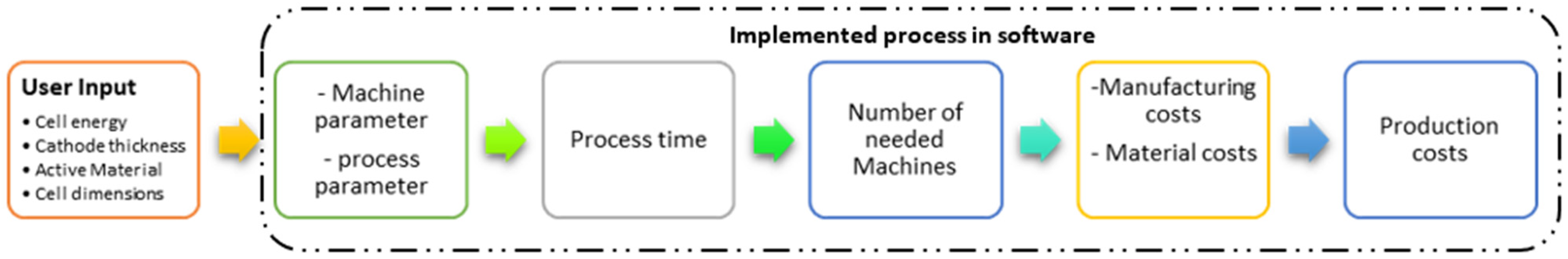

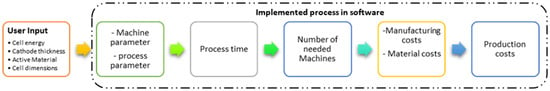

5.2. Manufacturing Cost

The cost of manufacturing batteries is shaped by raw material prices, production techniques [72], and economies of scale. Optimized processes, advanced technologies, and streamlined supply chains can significantly lower costs. Process-based cost modeling (PBCM) offers a bottom-up approach to estimating costs based on technical and operational parameters. As illustrated in Figure 9, PBCM provides insight into cost drivers, helps evaluate new technologies, and quantifies potential improvements [73]. By linking product attributes to technical, operational, and financial models, it enables transparent cost analysis and supports decisions in cost-sensitive industries.

Figure 9.

Battery-cell-specific PBCM framework.

5.3. Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) and Levelized Storage Cost (LCOS)

A complete economic evaluation requires analyzing both TCO and LCOS. TCO accounts for investment, installation, operation, maintenance, and end-of-life costs, offset by salvage value [74]. The formula is given by (1):

where represents the investment cost, is the lifetime of the battery (in years), and are respectively, the costs of operating and maintenance for the period , is the end-of-life cost, and is salvage cost.

LCOS, by contrast, expresses the cost per unit of energy stored and delivered over a battery’s lifetime [75]. This metric facilitates comparison across technologies by incorporating efficiency, cycle life, and discharge characteristics. Together, TCO and LCOS provide essential tools for guiding strategic decisions in the transition toward renewable-based energy systems.

6. Safety and Environmental Considerations

The safe and sustainable deployment of batteries requires close attention to both safety mechanisms and environmental impacts across their lifecycle.

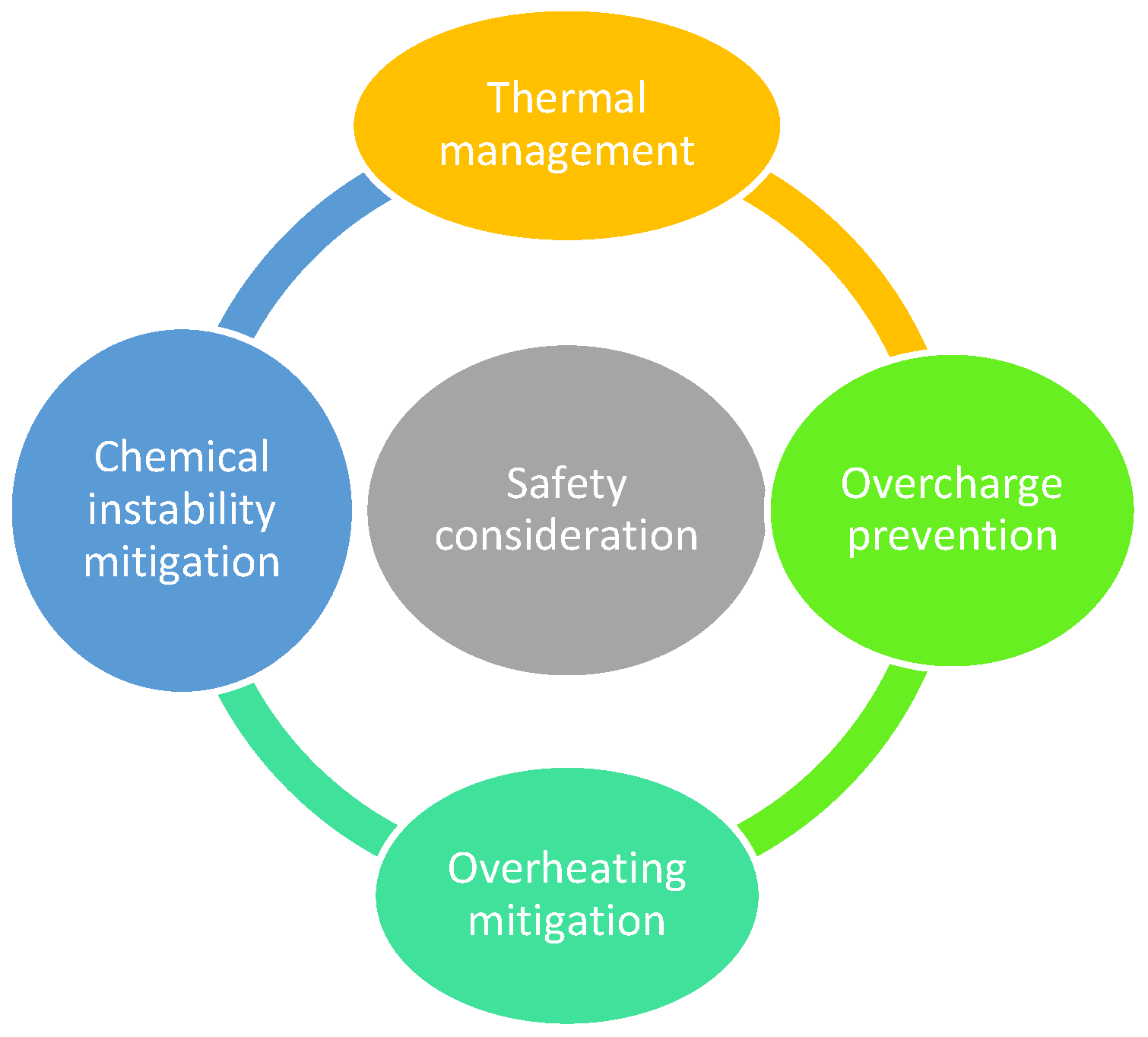

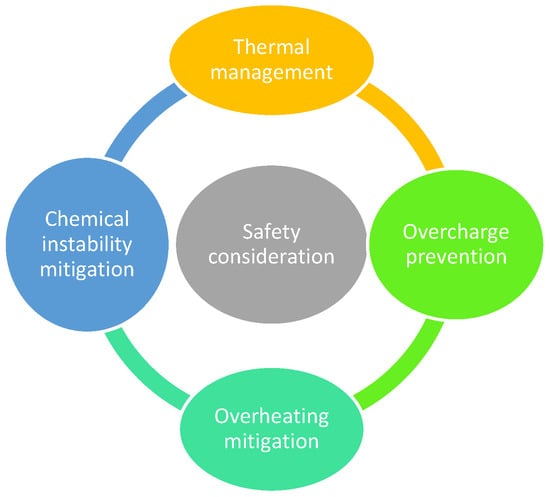

6.1. Safety Considerations

As depicted in Figure 10, battery safety depends on effective thermal management, overcharge prevention, and stability control [76]. Lithium-ion batteries, in particular, carry risks of fire or explosion if thermal runaway occurs, making robust cooling systems and protection circuits essential.

Figure 10.

Battery safety consideration.

Research has quantified the conditions that trigger thermal runaway in lithium-ion batteries, showing that the risk increases with SOC and specific temperature thresholds. Experimental work on 18,650 cells demonstrates that as SOC rises, the critical and peak temperatures associated with thermal runaway also increase, with fully charged cells reaching surface temperatures above 1000 °C and releasing larger amounts of flammable gases like CO and CH4, raising both fire and explosion hazards at high SOC levels [77]. Studies of thermal abuse mechanisms indicate that key components such as the solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) and electrolyte begin decomposing near ~80–100 °C, with cathode decomposition occurring at higher temperatures and contributing to exothermic reactions that fuel runaway [78]. Abuse tests further reveal that high charging or external heating rates accelerate the onset of thermal runaway, underscoring the importance of integrated thermal management and robust safety systems to prevent rapid temperature escalation and catastrophic failure in large-scale battery installations [79].

BMS play a central role in monitoring cell health, balancing charge, and preventing overloads. Recent advances in materials and the integration of self-protection features are further enhancing battery safety and reliability.

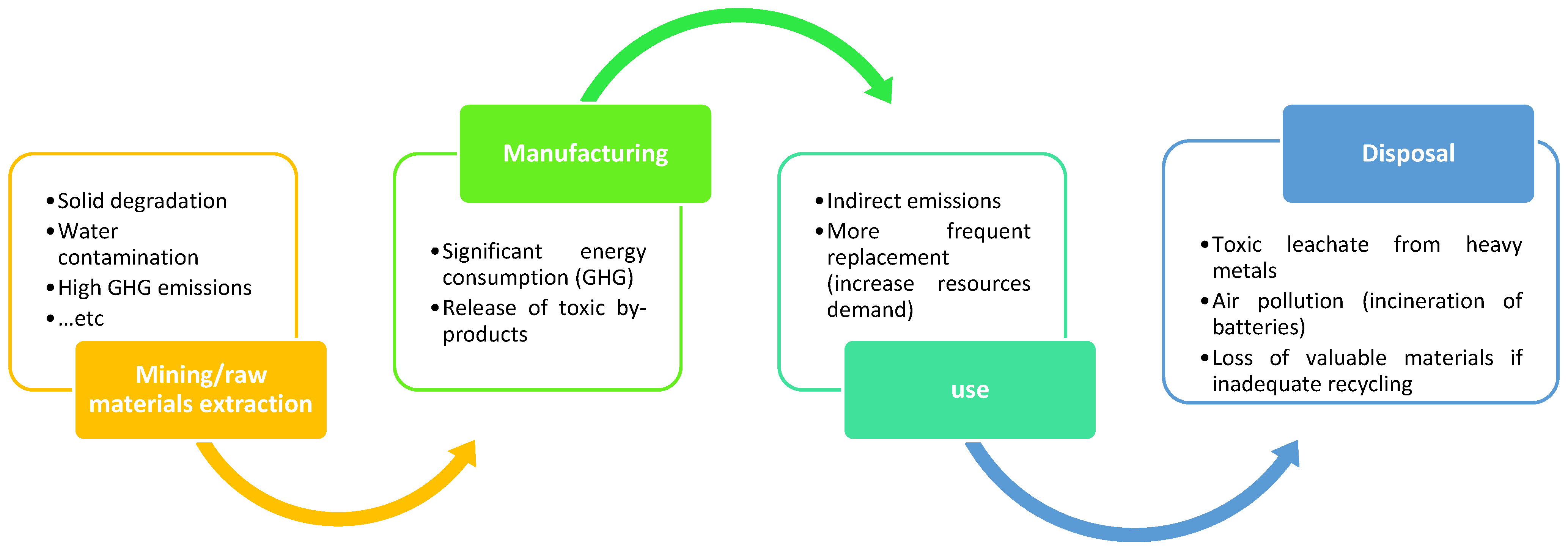

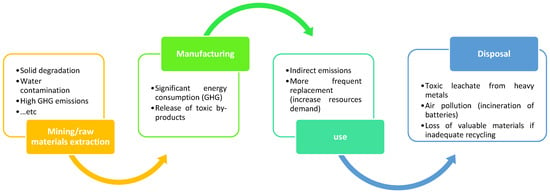

6.2. Environmental Impact

The environmental footprint of batteries spans extraction, production, use, and disposal, as illustrated in Figure 11. Mining of lithium, cobalt, and nickel can cause soil degradation, water pollution, and biodiversity loss [80], while refining and manufacturing are energy-intensive and generate emissions [81]. Battery operation indirectly contributes to emissions depending on the charging grid mix, with fossil-based grids increasing the carbon footprint. Over time, degradation leads to performance loss and higher replacement rates, raising resource demand. At end-of-life, poor disposal may release toxic leachates and harmful gases [82], while low recycling rates exacerbate raw material scarcity [83].

Figure 11.

Environmental impact of batteries.

6.3. Improving Safety and Reducing Environmental Impact

To address these issues, research focuses on safer chemistries, recycling technologies, and cleaner manufacturing processes. The use of abundant, non-toxic materials and efficient recovery methods reduces ecological impacts while extending material supply. Policy frameworks combined with technological innovation are key to ensuring batteries remain safe, reliable, and environmentally responsible as energy storage demand grows.

7. Integration and Grid Compatibility

The integration of large-scale battery systems into the electric grid entails not only scientific and engineering hurdles, but also legislative and societal obstacles. Recent developments in lithium-ion and hybrid systems have greatly improved grid services, particularly peak shaving and load balancing. However, successful integration necessitates extensive modeling and clever control systems. Beyond scientific and technical issues, numerous challenges related to the integration of large-scale battery storage systems of renewable energy for the electric grid range to policy issues, and even social challenges [84]. Increasing interest in helping grid support, particularly based on lithium-ion battery systems, is rapidly advancing with a wide range of cell technologies [85]. The implementation of the electricity peak shaving method using energy storage technologies minimizes consumption during peak demand periods and conducts both environmental and economic benefits. Integration of PV and battery storage recent advancements have made the peak-shaving method more attractive [86]. On the other hand, certain studies focus on smart load control methods and aim to reschedule the operation of flexible loads to periods of peak PV energy production.

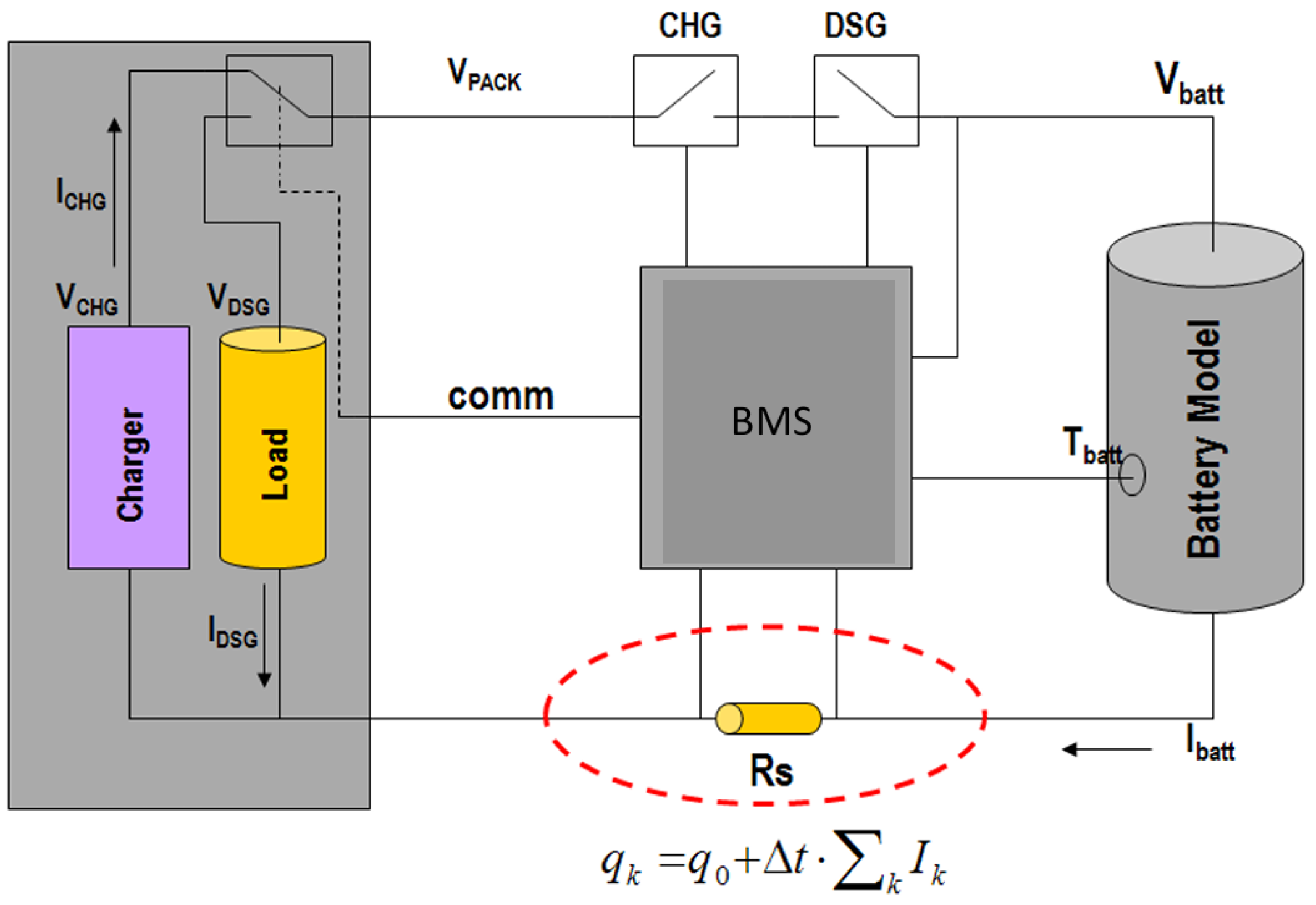

To analyze the battery integration and grid compatibility the battery models must be simulated correctly. The battery model in MATLAB/Simulink is investigated here to give readers more information’s how to analyze a nonlinear battery model. The other important topic for this aim is BMS. The BMS working principle and advantages are given with applications in the next section.

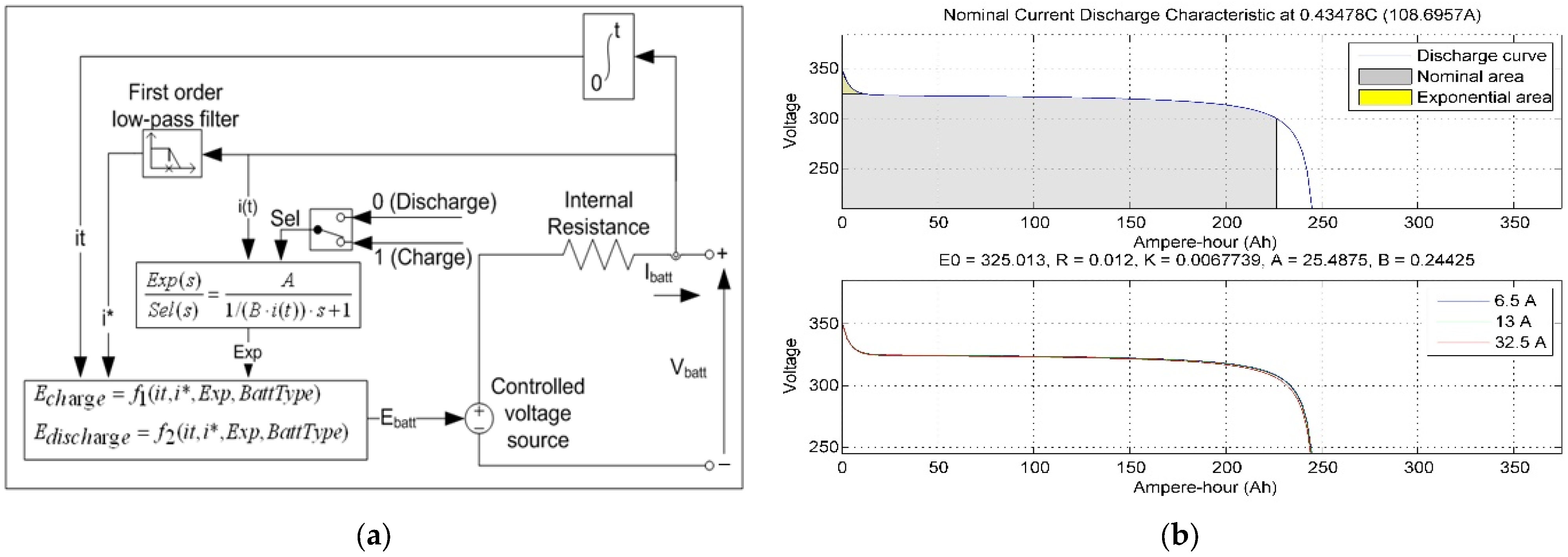

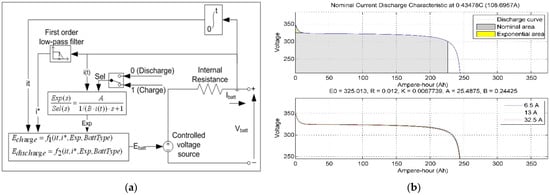

7.1. A Generic Battery Model Designed in MATLAB/Simulink

The battery model using a generic model for most popular battery types is designed in MATLAB/Simulink, as shown in Figure 12a. The battery model uses the lead–acid battery equations, lithium-ion, nickel–cadmium, and nickel–metal hydride type and adjusts the nominal voltage, rated capacity, and the initial SoC response time. Nominal voltage–current discharge characteristics for the specific battery model parameters are given in ampere–hour for nominal voltage in Figure 12b [87].

Figure 12.

(a) The generic battery model, (b) current discharge characteristics for the battery model parameters [88].

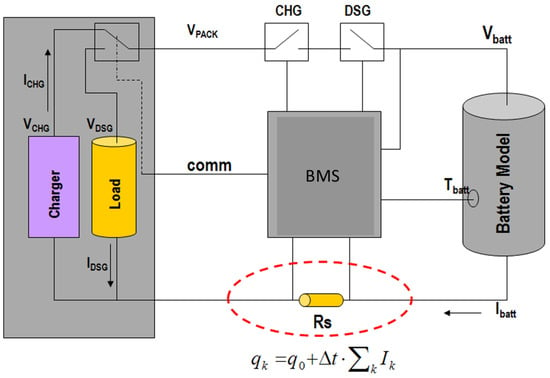

7.2. Battery Management Systems (BMS)

A rechargeable battery managed by a BMS is an electronic circuit system. BMS monitors and estimates its various states such as SoC and state of health. It consists of a cell or battery pack for easier safer usage and long-life of battery [89]. Calculation, reporting, controlling the environment, and verifying or balancing secondary data are the main purposes of BMS [88]. An alternative to BMS is a protection circuit module (PCM) [90]. A battery package built with a BMS with an external communication data bus which is known as a smart one [91]. A general battery management system working principle is shown in Figure 13 [92]. A BMS can monitor various items of the state of the battery as in Table 3.

Figure 13.

A general battery management system working principle [92].

Table 3.

Various items of a BMS to monitor the state of the battery.

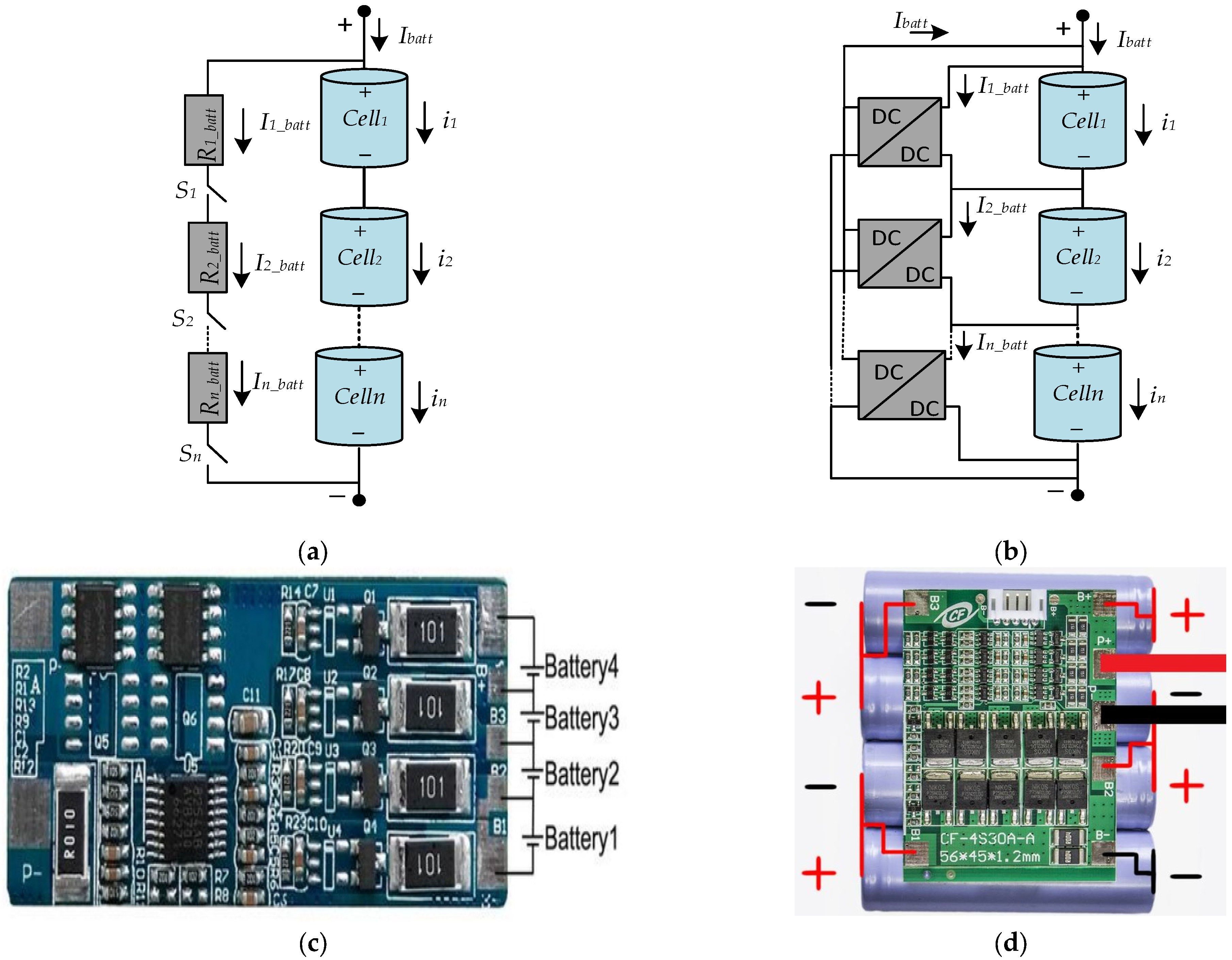

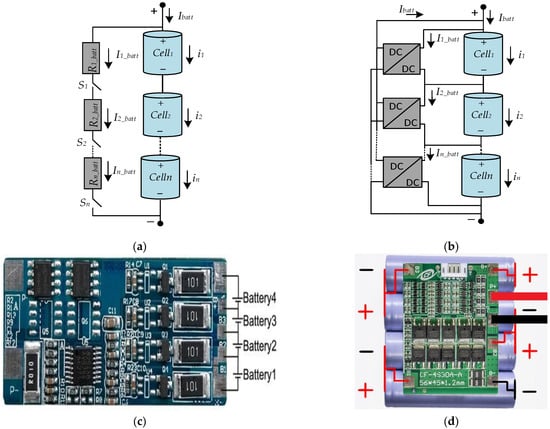

The principles of the BMS system for different types of circuits are given in Figure 14a,b. Figure 14a shows the BMS system consisting of a resistance and switch component to balance series connected battery voltages. Figure 14b shows the BMS system consisting of a DC-to-DC converter to balance series connected battery voltages. Figure 14c shows an electronic circuit of BMS which is designed connected to four batteries directly. Figure 14d shows an electronic circuit of BMS and a series battery connected to BMS.

Figure 14.

BMS circuits and examples: (a) switching BMS, (b) converter-based BMS, (c) BMS circuit, (d) BMS circuit with battery.

8. Emerging Technologies and Future Trends

Recent advancements in design and manufacturing battery technology, with power electronic circuits commonly integrated to meet the unique demands of different applications [93]. Research worldwide is actively focused on developing new materials for LIBs, as they power most modern portable devices and hold the potential to enable broader adoption of high-energy-density storage solutions on a larger scale [94]. Emerging energy storage technologies are anticipated to deliver enhanced energy and power densities, but in practice may not be more significant [39]. The power and energy density comparison of some energy storage devices is shown in Figure 15 [95].

Figure 15.

The energy and power density comparison of storage devices.

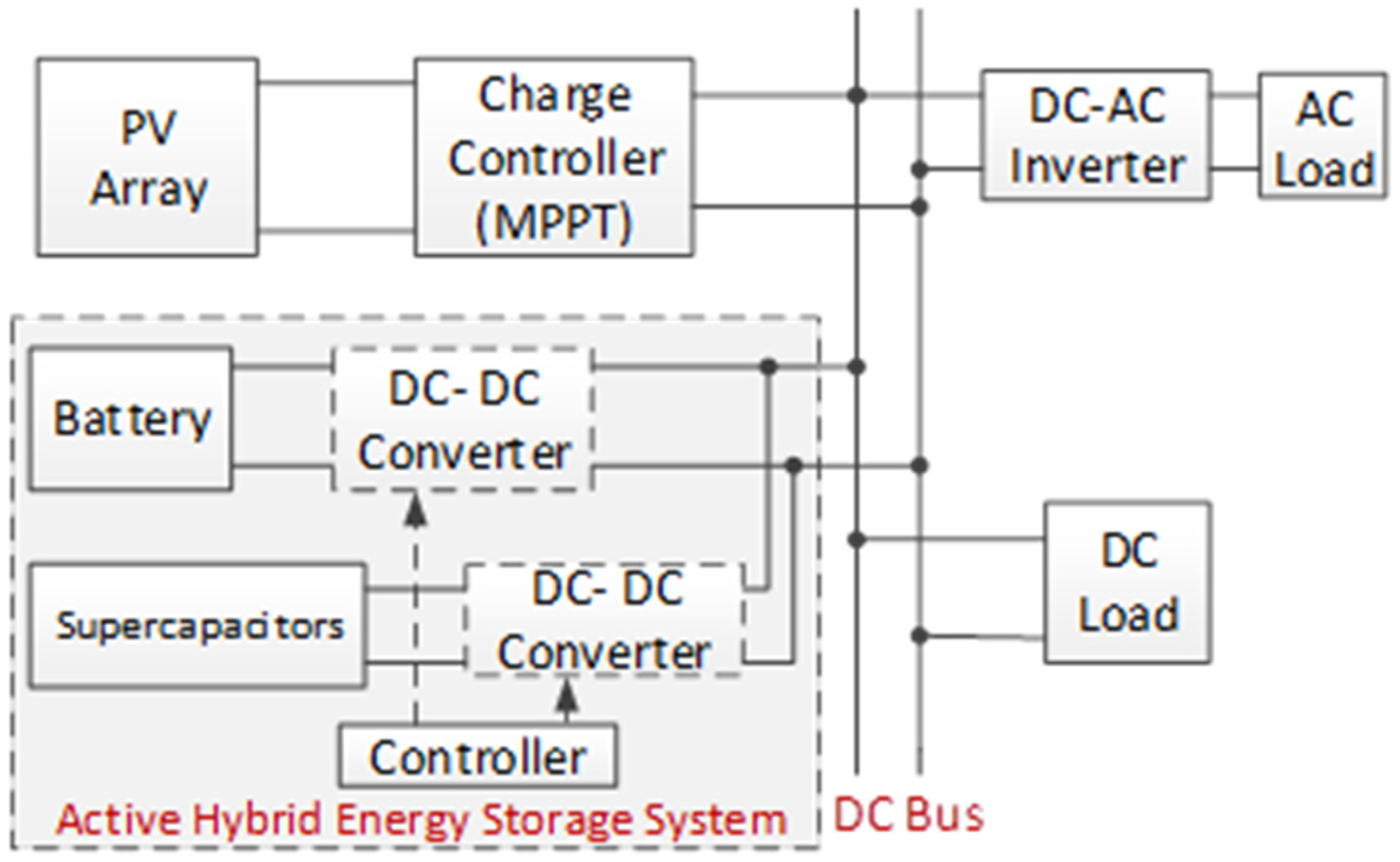

To deliver electricity to customers safely, reliably, and efficiently hybrid electricity systems describe the integration of multiple emerging and renewable energy technologies [96]. However, due to the unreliable nature of renewable energy sources (RES), various ESS are available to balance the demand and supply gap. Nevertheless, hybrid energy storage systems (HESS) are mostly recommended to accommodate the different characteristics, such as power density and reaction time, that accompany each specific storage [97]. The HESS for novel supercapacitor (SC) storage devices and required bidirectional converters are investigated in the next stages.

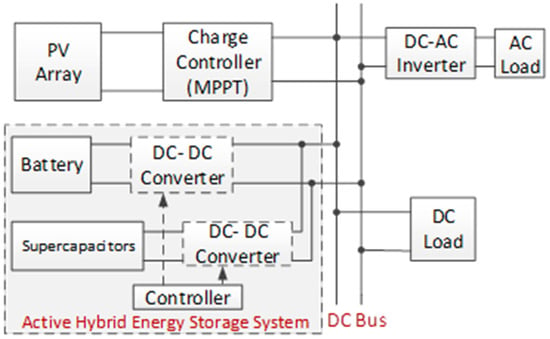

8.1. Hybrid Energy Storage Systems (HESS)

HESS are categorized into three main types: passive, semi-active, and active. A passive HESS occurs when storage devices are directly linked to the DC bus. In a semi-active HESS, only the battery is connected to the DC bus through a DC-DC converter. An active HESS, on the other hand, integrates both the battery and the supercapacitor with a DC-DC converter before linking them to the DC bus [98]. As a case study, a standalone active HESS is given in Figure 16 [99].

Figure 16.

Active HESS with battery-SC.

In a case study simulation, semi-active SC-HESS configurations showed performance that was over 33% lower compared to battery-only systems, while passive HESS setups exhibited less than a 9% reduction in the cost function relative to battery-only cases. Another simulation employed solar irradiance and temperature data to estimate the annual storage cost.

The Hybrid Optimization Model for Electric Renewable (HOMER) software (HOMER Pro (v3.13+)) can be used to simulate the optimal sizing of a HESS that aligns with the load profiles at the designated site [100,101]. This simulation is based on available renewable energy resources and component specifications. Although the capital cost of SC is a higher ratio; the total cost ratio of SC is seen as less because SCs do not require replacement and operation and manufacturing (O&M) costs.

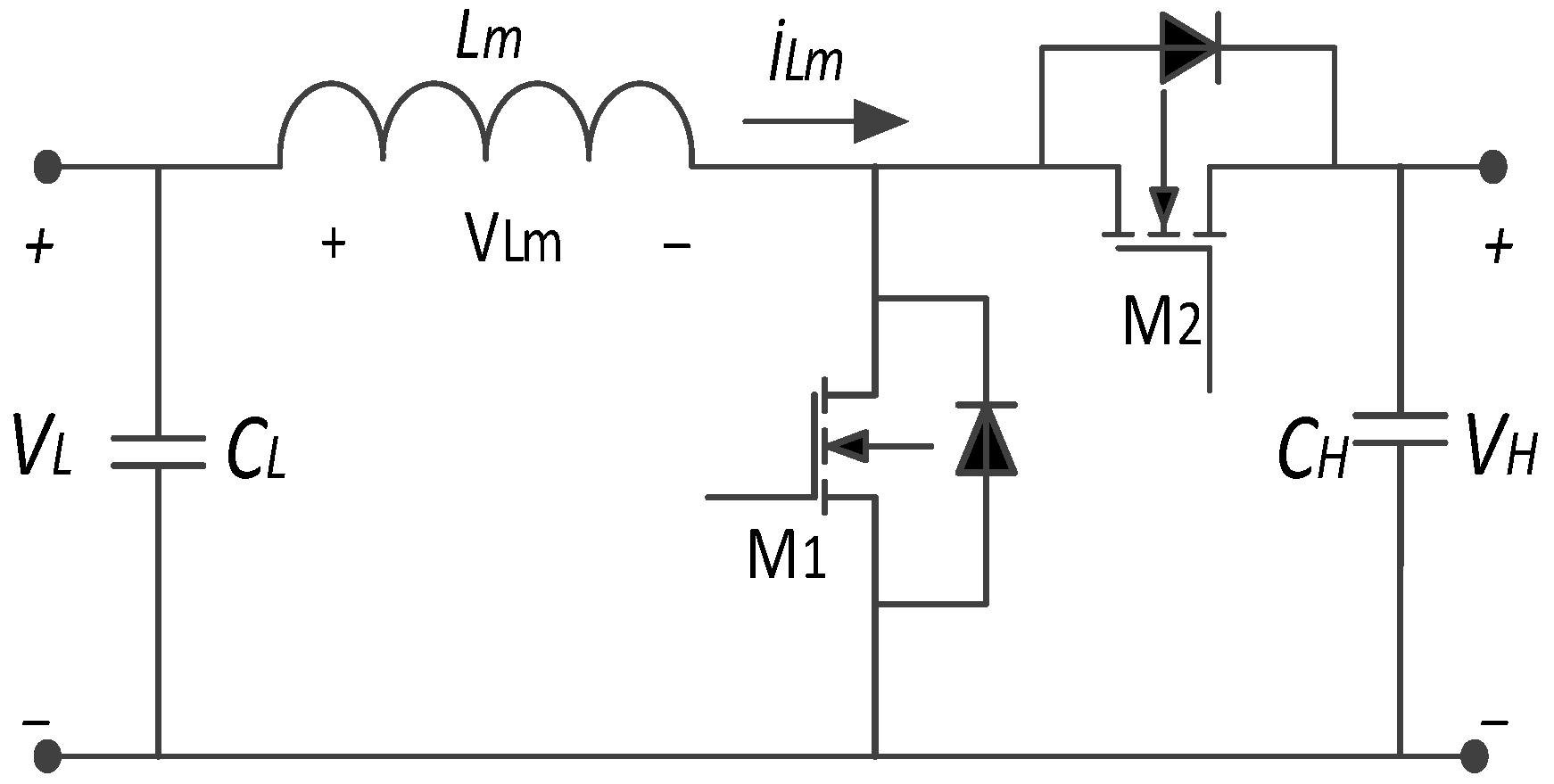

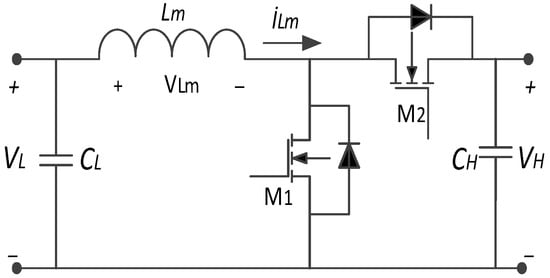

8.2. Bidirectional Converters for HESS

Bidirectional power converters are installed between the bus and battery or SC parts to control current flow in two ways for active or semi-active power control. When the PV generates the energy, it is routinely stored in the battery, and SCs are regularly dependent on the load. On the other side, the bidirectional converter is used to energize the loads from the battery and SCs [102]. Figure 17 illustrates a bidirectional buck–boost converter. As shown in Figure 17, this converter allows the battery to be charged using energy from the PV panel. However, during nighttime, when PV generation is unavailable, the energy stored in the battery supplies power to the load. The converter operates in buck mode based on the duty ratio, directing current from the PV source to charge the battery. Conversely, in boost mode, also dependent on the duty ratio, current flows from the battery to the load [103].

Figure 17.

A bidirectional buck–boost converter circuit.

9. Green Batteries for Renewable Technologies

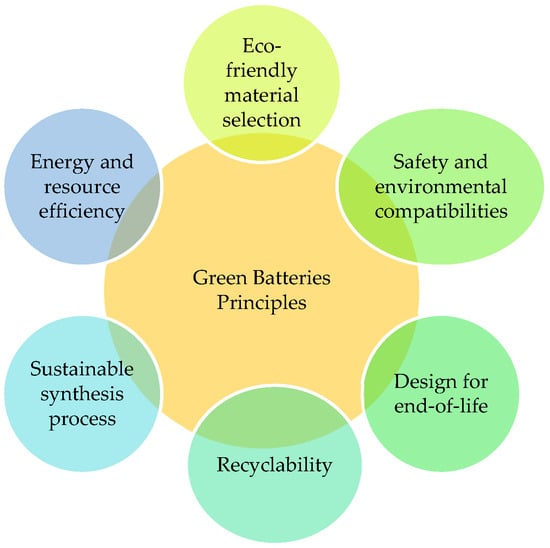

As the deployment of solar and wind energy continues to grow, reliable and sustainable energy storage solutions are essential to address their inherent intermittency and ensure grid stability. Green batteries respond to this challenge by combining effective energy storage capabilities with a reduced environmental footprint across their entire lifecycle. Unlike conventional lithium- and cobalt-based batteries, which rely on scarce and often environmentally damaging materials, green batteries prioritize the use of abundant, non-toxic alternatives such as sodium, zinc, iron, or organic compounds. In addition, many of these technologies are designed with recyclability and end-of-life recovery in mind, supporting circular economy principles and reducing long-term resource depletion.

From a climate perspective, green batteries can significantly contribute to greenhouse gas emission reductions by enabling higher penetration of renewable energy sources and decreasing reliance on fossil-fuel-based peaking power plants. When charged using low-carbon electricity, battery energy storage systems help smooth power fluctuations, improve grid flexibility, and lower system-level emissions over their operational lifetime. However, lifecycle assessments indicate that battery manufacturing remains energy-intensive, with notable emissions arising from material extraction, processing, and cell production. Therefore, the true environmental benefits of green batteries depend not only on their chemistry but also on cleaner manufacturing pathways and low-carbon energy inputs.

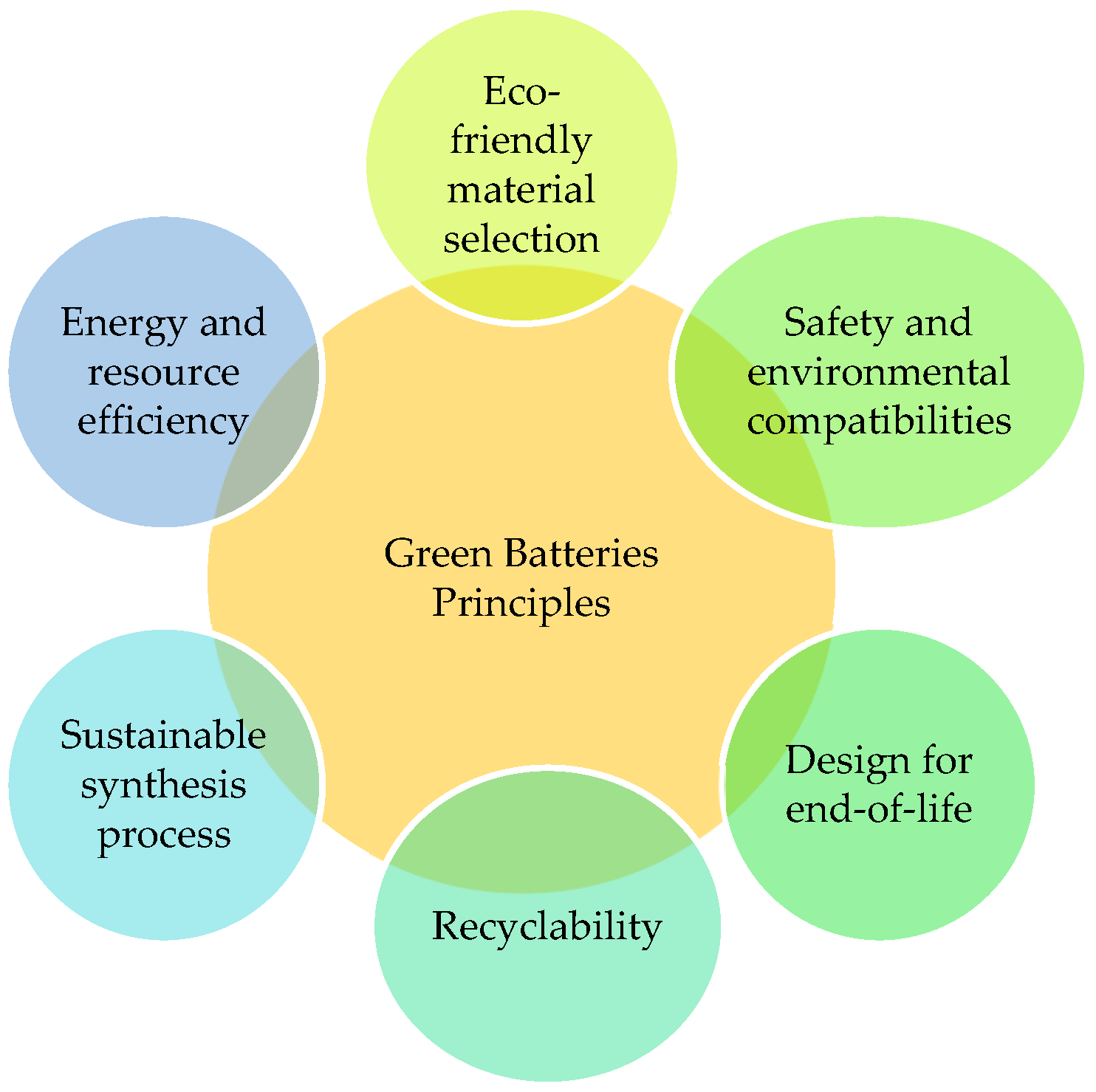

In terms of resource consumption, large-scale battery deployment increases demand for raw materials, raising concerns about supply security and environmental impacts associated with mining activities. Green battery technologies aim to mitigate these challenges by reducing dependence on critical materials such as lithium, cobalt, and nickel. Promising alternatives include sodium-ion batteries, redox flow batteries, and supercapacitors, which offer lower material constraints, longer service life, and improved safety, particularly for stationary energy storage applications. These technologies are well suited for storing excess renewable energy during periods of high generation and releasing it when production is low or demand peaks. The basic principles of green batteries are illustrated in Figure 18.

Figure 18.

Green batteries principles.

Ongoing research efforts focus on improving the energy density, durability, safety, and cost-effectiveness of green batteries, as well as extending their operational lifetime through advanced battery management and thermal control systems. At the same time, policy support, recycling infrastructure development, and technological innovation are expected to accelerate their market adoption. Ultimately, green batteries represent a key pillar of sustainable energy systems, provided that their design, manufacturing, and end-of-life management are aligned with long-term goals for emission reduction, resource efficiency, and environmental protection.

10. Recycling and Reuse of Battery Systems

As the deployment of energy storage systems (ESS) accelerates across power grids, transportation, and renewable energy applications, recycling and reuse have become critical factors in assessing their long-term sustainability. Recent lifecycle assessment (LCA) studies indicate that battery manufacturing accounts for a substantial share of total environmental impacts, primarily due to energy-intensive mining and processing of critical materials such as lithium, cobalt, and nickel. In some cases, production-related emissions represent up to 40–60% of total lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions, emphasizing the importance of effective end-of-life management strategies to reduce carbon intensity and resource depletion [104].

Recycling technologies have advanced significantly in recent years, moving beyond traditional pyrometallurgical routes toward hydrometallurgical and direct recycling processes. Hydrometallurgical recycling enables high recovery rates of valuable metals with lower energy consumption and reduced emissions, while direct recycling preserves cathode materials and crystal structures, offering further environmental and economic benefits. Recent studies report that direct recycling can lower energy demand and greenhouse gas emissions by up to 30% compared to conventional methods, making it a promising pathway for circular battery value chains [105].

In parallel, battery reuse, particularly second-life applications, offers an effective strategy to extend service life and improve overall system sustainability. Lithium-ion batteries retired from electric vehicles often retain 70–80% of their original capacity, making them suitable for stationary energy storage applications such as renewable energy buffering, peak shaving, and grid support. Recent analyses show that second-life deployment can extend battery utilization by 5–10 years and reduce lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions by up to 30%, depending on the application and electricity mix [106]. However, challenges related to safety, state-of-health assessment, standardization, and repurposing costs remain and require advanced battery management systems and harmonized regulations.

11. Future Research Directions

Future advances in energy storage must focus on new materials, efficiency, safety, and sustainability. Developing solid-state electrolytes, organic chemistries, and recyclable electrodes will improve performance while reducing reliance on scarce resources. At the same time, innovative designs are needed to enhance energy density and round-trip efficiency in real-world conditions.

While batteries grab headlines, other storage technologies offer unique advantages that make them indispensable for certain applications. Pumped hydro storage remains the quiet giant of energy storage, accounting for over 94% of installed global capacity. It is surprisingly efficient as well, converting 70–85% of input energy back to electricity. Gravity-based storage takes pumped hydro’s basic principle but replaces water with solid weights. Compressed air energy storage (CAES) works by essentially storing energy as pressurized air in underground caverns or containers. When electricity is needed, this air is released through turbines. Flow batteries strike a fascinating middle ground between conventional batteries and mechanical storage. This scalability makes them especially interesting for longer-duration needs [107].

Large-scale use demands better thermal management and safety systems to prevent failures, alongside cost-effective and modular manufacturing for wider adoption. Equally important is reducing environmental impact through advanced recycling technologies, end-of-life design, and standardized lifecycle assessments. Finally, emerging systems like sodium-ion, metal–air, and redox flow batteries hold promise, but further research is required to prove their scalability and commercial readiness.

12. Conclusions

This review highlights the critical technical aspects of energy storage systems, focusing on efficiency, reliability, scalability, safety, and environmental considerations. Various storage technologies, including lithium-ion, lead–acid, flow batteries, and emerging green battery solutions, exhibit unique strengths and challenges in areas such as energy density, cycle life, manufacturing costs, and environmental impact. Technical challenges, including thermal management, material availability, recycling efficiency, and integration with renewable energy systems, remain key barriers to maximizing the potential of energy storage technologies.

Addressing these technical challenges is essential to achieving a sustainable and resilient energy future. Innovations in material science, advancements in battery design, enhanced recycling technologies, and improved manufacturing processes are necessary to overcome these barriers. Moreover, collaborative efforts across policymakers, industry practitioners, and researchers are crucial to driving investments, establishing regulatory frameworks, and fostering research initiatives focused on energy storage advancements.

Policymakers should prioritize incentives for sustainable energy storage projects, while industry stakeholders must adopt best practices for safety, lifecycle management, and scalability. Researchers should continue to explore novel materials, optimize existing technologies, and address the technical gaps identified in this review. Together, these efforts will ensure that energy storage systems play a pivotal role in supporting the global transition toward a cleaner, more reliable, and sustainable energy infrastructure.

Author Contributions

T.S.: Conceptualization, methodology, data curation, writing—original draft, formal analysis, investigation, visualization, supervision, writing—review and editing. T.A.M.: Conceptualization, methodology, data curation, writing—original draft, formal analysis, investigation, visualization, supervision, writing—review and editing. M.E.Ş.: Conceptualization, methodology, data curation, writing—original draft, formal analysis, investigation, visualization, supervision, writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known conflicts of interest.

References

- BP Energy. BP Energy Outlook 2018. Available online: https://www.bp.com/content/dam/bp/business-sites/en/global/corporate/pdfs/energy-economics/energy-outlook/bp-energy-outlook-2018.pdf (accessed on 21 January 2026).

- Sebbagh, T.; Şahin, M.E.; Beldjaatit, C. Green hydrogen revolution for a sustainable energy future. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2024, 26, 4017–4040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badi, N.; Theodore, A.M.; Alghamdi, S.A.; Alatawi, A.S.; Almasoudi, A.; Lakhouit, A.; Roy, A.S.; Ignatiev, A. Thermal effect on curved photovoltaic panels: Model validation and application in the Tabuk region. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0275467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfo, T.A.; Konwar, S.; Singh, P.K.; Mehra, R.M.; Kumar, Y.; Gupta, M. PEO + NaSCN and ionic liquid based polymer electrolyte for supercapacitor. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 34, 802–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, G.J.; Davidson, A.; Monahov, B. Lead batteries for utility energy storage: A review. J. Energy Storage 2018, 15, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodore Azemtsop, M. A Comprehensive Analysis of Material Revolution to Evolution in Lithium-ion Battery Technology. Turk. J. Mater. 2023, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, T.B. Linden’s Handbook of Batteries, 4th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Asri, L.I.M.; Ariffin, W.N.S.F.W.; Zain, A.S.M.; Nordin, J.; Saad, N.S. Comparative study of energy storage systems (ESSs). J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1962, 012035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omri, A.; Belaïd, F. Does renewable energy modulate the negative effect of environmental issues on socio-economic welfare? J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 278, 111483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, P.; Zheng, C.; He, J.; Tu, X.; Sun, W.; Pan, H.; Zhou, Y.; Rui, X.; Zhang, B.; Huang, K. Structural engineering in graphite-based metal-ion batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 46, 2107277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alami, A.H.; Maghrabie, H.M.; Abdelkareem, M.A.; Sayed, E.T.; Yasser, Z.; Salameh, T.; Rahman, S.M.A.; Rezk, H.; Olabi, A.G. Potential applications of phase change materials for batteries’ thermal management systems in electric vehicles. J. Energy Storage 2022, 54, 105204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelkareem, M.A.; Maghrabie, H.M.; Abo-Khalil, A.G.; Adhari, O.H.K.; Sayed, E.T.; Radwan, A.; Rezk, H.; Jouhara, H.; Olabi, A.G. Thermal management systems based on heat pipes for batteries in EVs/HEVs. J. Energy Storage 2022, 51, 104384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Li, T.; Zhong, L.; Lu, J. Flexible metal–air batteries: An overview. SmartMat 2021, 35, 628–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masias, A.; Marcicki, J.; Paxton, W.A. Opportunities and challenges of lithium-ion batteries in automotive applications. ACS Energy Lett. 2021, 6, 621–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Q.; Kelly, J.C.; Gaines, L.; Wang, M. Life cycle analysis of lithium-ion batteries for automotive applications. Batteries 2019, 5, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, M.S.; Trancik, J.E. Re-examining rates of lithium-ion battery technology improvement and cost decline. Energy Environ. Sci. 2021, 14, 1635–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; See, K.W.; Wang, G.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zang, C.; Xie, B. Explosion-proof lithium-ion battery pack: In-depth investigation and experimental study on the design criteria. Energy 2022, 249, 123715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, Z.; Luo, L.; Fan, Y.; Du, Z. A review on thermal management of lithium-ion batteries for electric vehicles. Energy 2022, 238, 121652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olabi, A.G.; Abbas, Q.; Shinde, P.A.; Abdelkareem, M.A. Rechargeable batteries: Technological advancement, challenges, current and emerging applications. Energy 2023, 266, 126408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzivasileiadi, A.; Ampatzi, E.; Knight, I. Characteristics of electrical energy storage technologies and their applications in buildings. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 25, 814–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, E.; Faruque, H.M.R.; Sunny, M.S.H.; Mohammad, N.; Nawar, N. A comprehensive review on energy storage systems: Types, comparison, current scenario, applications, barriers, and potential solutions. Energies 2020, 13, 3651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Placke, T.; Kloepsch, R.; Dühnen, S.; Winter, M. Lithium ion, lithium metal, and alternative rechargeable battery technologies: The odyssey for high energy density. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2017, 21, 1939–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linden, D.; Reddy, T.B. Handbook of Batteries, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Guney, M.S.; Tepe, Y. Classification and assessment of energy storage systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 75, 1187–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabal, M.A.; Al-Luhaibi, R.S.; Alangari, Y.M. Recycling spent zinc–carbon batteries through synthesizing nanocrystalline Mn–Zn ferrites. Powder Technol. 2014, 258, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avraamides, J.; Senanayake, G.; Clegg, R. Sulfur dioxide leaching of spent zinc–carbon battery scrap. J. Power Sources 2006, 159, 1488–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takamura, T. Primary batteries—Aqueous systems: Alkaline manganese–zinc. In Encyclopedia of Electrochemical Power Sources; Garche, J., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, N.; Wang, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, P.F.; Liu, Y.G.; Xie, Y.; Yi, T.F. Towards high-performance aqueous Zn–MnO2; batteries: Formation mechanism and alleviation strategies of irreversible inert phases. Compos. Part B Eng. 2023, 260, 110770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, C.C.B.M.; De Oliveira, D.C.; Tenório, J.A.S. Characterization of used alkaline batteries powder and analysis of zinc recovery by acid leaching. J. Power Sources 2001, 103, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Bai, P.; Chen, Z.; Su, H.; Yang, J.; Xu, K.; Xu, Y. A lithium–organic primary battery. Small 2020, 16, 1906462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, D.C.; Marschilok, A.C.; Takeuchi, K.J.; Takeuchi, E.S. Batteries used to power implantable biomedical devices. Electrochim. Acta 2012, 84, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Su, M.Y.; Gu, Z.Y.; Zhang, K.Y.; Wang, X.T.; Du, M.; Guo, J.Z.; Wu, X.L. Advanced lithium primary batteries: Key materials, research progress, and challenges. Chem. Rec. 2022, 22, e202200081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.A.; Wang, X.; Wen, C. High energy density metal–air batteries: A review. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2013, 160, A1759–A1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppmann, J.; Volland, J.; Schmidt, T.S.; Hoffmann, V.H. The economic viability of battery storage for residential solar photovoltaic systems: A review and a simulation model. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 39, 1101–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, C.A. Lithium batteries: A 50-year perspective, 1959–2009. Solid State Ion. 2000, 134, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Li, F.; Ma, L.P.; Cheng, H.M. Advanced materials for energy storage. Adv. Mater. 2010, 22, E28–E62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, H.; Ilinca, A.; Perron, J. Energy storage systems—Characteristics and comparisons. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2008, 12, 1221–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondoh, J.; Ishii, I.; Yamaguchi, H.; Murata, A.; Otani, K.; Sakuta, K.; Higuchi, N.; Sekine, S.; Kamimoto, M. Electrical energy storage systems for energy networks. Energy Convers. Manag. 2000, 41, 1863–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J. New technology and possible advances in energy storage. Energy Policy 2008, 36, 4368–4373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, J.F. Battery energy-storage systems—An emerging market for lead–acid batteries. J. Power Sources 1995, 53, 239–244. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, C.D. Lead–acid battery energy-storage systems for electricity supply networks. J. Power Sources 2001, 100, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doughty, D.H.; Butler, P.C.; Akhil, A.A.; Clark, N.H.; Boyes, J.D. Batteries for large-scale stationary electrical energy storage. Electrochem. Soc. Interface 2010, 19, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacín, M.R.; De Guibert, A. Why do batteries fail? Science 2016, 351, 1253292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poullikkas, A. A comparative overview of large-scale battery systems for electricity storage. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 27, 778–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.; Hunt, G.L. The great battery search: Energy storage for electric vehicles. IEEE Spectr. 2002, 35, 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H.; Guo, S.; Zhao, H. Comprehensive performance assessment on various battery energy storage systems. Energies 2018, 11, 2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, S.J.; Sun, K. Microstructural design considerations for Li-ion battery systems. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2012, 16, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, N.H.; Doughty, D.H. Development and testing of 100 kW/1 min Li-ion battery systems for energy storage applications. J. Power Sources 2005, 146, 798–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, K.; Tajima, H.; Hashimoto, T.; Kobayashi, K. Development of a 16 kWh power storage system applying Li-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2003, 119–121, 897–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waag, W.; Käbitz, S.; Sauer, D.U. Experimental investigation of the lithium-ion battery impedance characteristic at various conditions and aging states and its influence on the application. Appl. Energy 2013, 102, 885–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.C.; Lin, T.; Brown, G.; Biensan, P.; Bonhomme, F. Decay processes and life predictions for lithium-ion satellite cells. In Proceedings of the 4th International Energy Conversion Engineering Conference, San Diego, CA, USA, 26–29 June 2006. [Google Scholar]

- El Mejdoubi, A.; Chaoui, H.; Gualous, H.; Van Den Bossche, P.; Omar, N.; Van Mierlo, J. Lithium-ion batteries health prognosis considering aging conditions. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2019, 34, 6834–6846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetter, J.; Novák, P.; Wagner, M.R.; Veit, C.; Möller, K.C.; Besenhard, J.O.; Winter, M.; Wohlfahrt-Mehrens, M.; Vogler, C.; Hammouche, A. Ageing mechanisms in lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2005, 147, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redondo-Iglesias, E.; Venet, P.; Pelissier, S. Efficiency degradation model of lithium-ion batteries for electric vehicles. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2018, 55, 1932–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi-Eichi, H.; Ojha, U.; Baronti, F.; Chow, M.Y. Battery management system: An overview of its application in the smart grid and electric vehicles. IEEE Ind. Electron. Mag. 2013, 7, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyden, A.; Soo, V.K.; Doolan, M. The environmental impacts of recycling portable lithium-ion batteries. Procedia CIRP 2016, 48, 188–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seh, Z.W.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Cui, Y. Designing high-energy lithium–sulfur batteries. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 5605–5634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, R.; Zhao, S.; Sun, Z.; Wang, D.W.; Cheng, H.M.; Li, F. More reliable lithium–sulfur batteries: Status, solutions, and prospects. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1606823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, Z.; Yan, J. Zinc hydroxystannate as high cycle performance negative electrode material for Zn/Ni secondary battery. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2016, 163, A1602–A1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, K.M. How comparable are sodium-ion batteries to lithium-ion counterparts? ACS Energy Lett. 2020, 5, 3544–3547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.; Wu, F.; Huang, Y. Sodium-Ion Batteries: Advanced Technology and Applications; Springer: Singapore, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Jha, A.R. Next-Generation Batteries and Fuel Cells for Commercial, Military, and Space Applications; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Möller, S.; Satoh, T.; Ishii, Y.; Teßmer, B.; Guerdelli, R.; Kamiya, T.; Fujita, K.; Suzuki, K.; Kato, Y.; Wiemhöfer, H.D.; et al. Absolute local quantification of Li as function of state-of-charge in all-solid-state Li batteries via 2D MeV ion-beam analysis. Batteries 2021, 7, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Guo, J.; Pedersen, K.; Gurevich, L.; Stroe, D.I. Recent health diagnosis methods for lithium-ion batteries. Batteries 2022, 8, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Gabalawy, M.; Hosny, N.S.; Hussien, S.A. Lithium-ion battery modeling including degradation based on single-particle approximations. Batteries 2020, 6, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Burke, A.F. Electric vehicle batteries: Status and perspectives of data-driven diagnosis and prognosis. Batteries 2022, 8, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, K.; Barton, J.L.; Milshtein, J.D.; Brushett, F.R. Small-scale, low-cost flow cell platform for rapid characterization of redox flow battery materials. In Electrochemical Society Meeting Abstracts Prime 2020; The Electrochemical Society, Inc.: Pennington, NJ, USA, 2020; p. 2674. [Google Scholar]

- Nykvist, B.; Nilsson, M. Rapidly falling costs of battery packs for electric vehicles. Nat. Clim. Change 2015, 5, 329–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Schmidt, O.G. Batteries for small-scale robotics. MRS Bull. 2024, 49, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). Utility-Scale Batteries: Innovation Landscape Brief; IRENA: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Global Battery Storage Capacity Additions, 2010–2023. Available online: https://www.iea.org (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Lechner, M.; Kollenda, A.; Bendzuck, K.; Burmeister, J.K.; Mahin, K.; Keilhofer, J.; Kemmer, L.; Blaschke, M.J.; Friedl, G.; Daub, R.; et al. Cost modeling for the GWh-scale production of modern lithium-ion battery cells. Commun. Eng. 2024, 3, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farooq, M.A.; Roth, R.; Kirchain, R. Lightweighting technologies: Analyzing strategic and economic implications of advanced manufacturing processes. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2018, 206, 266–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielis, R.; Scorrano, M.; Masutti, M.; Awan, A.M.; Niazi, A.M.K. The economic competitiveness of hydrogen fuel cell-powered trucks: A review of total cost of ownership estimates. Energies 2024, 17, 2509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremoncini, D.; Di Lorenzo, G.; Frate, G.F.; Bischi, A.; Baccioli, A.; Ferrari, L. Techno-economic analysis of aqueous organic redox flow batteries: Stochastic investigation of capital cost and levelized cost of storage. Appl. Energy 2024, 360, 122738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Feng, X.; Tran, M.K.; Fowler, M.; Ouyang, M.; Burke, A.F. Battery safety: Fault diagnosis from laboratory to real world. J. Power Sources 2024, 598, 234111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Xing, K.; Jiang, X.; Shu, C.M.; Sun, X. Thermal runaway critical threshold and gas release safety boundary of 18650 lithium-ion battery in state of charge. Processes 2025, 13, 2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.; Wang, J.; Peng, Y.; Li, B.; Feng, C.; Shen, L.; Ma, S. Research advances on thermal runaway mechanism of lithium-ion batteries and safety improvement. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2024, 41, e01017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Wang, Z.; Kong, L.; Xu, F.; Dong, X.; Shen, J. Investigating the thermal runaway characteristics of the prismatic lithium iron phosphate battery under a coupled charge rate and ambient temperature. Batteries 2025, 11, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, J.F.; Baumann, M.; Zimmermann, B.; Braun, J.; Weil, M. The environmental impact of Li-ion batteries and the role of key parameters—A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 67, 491–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrose, H.; Kendall, A. Effects of battery chemistry and performance on the life cycle greenhouse gas intensity of electric mobility. Transp. Res. D Transp. Environ. 2016, 47, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaines, L. Lithium-ion battery recycling processes: Research towards a sustainable course. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2018, 17, e00068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, G.; Sommerville, R.; Kendrick, E.; Driscoll, L.; Slater, P.; Stolkin, R.; Walton, A.; Christensen, P.; Heidrich, O.; Lambert, S.; et al. Recycling lithium-ion batteries from electric vehicles. Nature 2019, 575, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faunce, T.A.; Prest, J.; Su, D.; Hearne, S.J.; Iacopi, F. On-grid batteries for large-scale energy storage: Challenges and opportunities for policy and technology. MRS Energy Sustain. 2018, 5, E11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesse, H.C.; Schimpe, M.; Kucevic, D.; Jossen, A. Lithium-ion battery storage for the grid—A review of stationary battery storage system design tailored for applications in modern power grids. Energies 2017, 10, 102107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahari, N.E.M.; Mokhlis, H.; Mubarak, H.; Mansor, N.N.; Sulaima, M.F.; Ramasamy, A.K.; Zulkapli, M.F.; Ja’Apar, M.A.B.; Jaafar, M.; Marsadek, M.B. Integrating solar PV, battery storage, and demand response for industrial peak shaving: A systematic review on strategy, challenges and case study in Malaysian food manufacturing. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 106832–106856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, M.E.; Sharaf, A.M. A robust decoupled microgrid charging scheme using a DC green plug-switched filter compensator. In Fast Charging and Resilient Transportation Infrastructures in Smart Cities; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 241–266. [Google Scholar]

- Barsukov, Y.; Qian, J. Battery Power Management for Portable Devices; Artech House: Norwood, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan, S.K.; Chakraborty, B. Battery management strategies: An essential review for battery state-of-health monitoring techniques. J. Energy Storage 2022, 51, 104427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, O.; Dessaint, L.A. Experimental validation of a battery dynamic model for EV applications. World Electr. Veh. J. 2009, 3, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; So, J. VLSI design and FPGA implementation of state-of-charge and state-of-health estimation for electric vehicle battery management systems. J. Energy Storage 2023, 73, 108876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özbek, S. Batarya Teknolojileri, Batarya Yönetim Sistemleri; Presentation, 2018. Available online: https://www.emo.org.tr/ekler/2b80eb2d8d6fe7f_ek.pdf?tipi=2&turu=X&sube=14 (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Itani, K.; De Bernardinis, A. Review on new-generation batteries technologies: Trends and future directions. Energies 2023, 16, 7530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W. Battery technologies in electrochemical energy storage. Highlights Sci. Eng. Technol. 2023, 80, 400–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, M.E.; Blaabjerg, F.; Sangwongwanich, A. A comprehensive review on supercapacitor applications and developments. Energies 2022, 15, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asian Development Bank. Hybrid and Battery Energy Storage Systems; Asian Development Bank: Manila, Philippines, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Shirinda, K.; Kanzumba, K. A review of hybrid energy storage systems in renewable energy applications. Int. J. Smart Grid Clean Energy 2022, 11, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, M.E.; Blaabjerg, F. PV powered hybrid energy storage system control using bidirectional and boost converters. Electr. Power Compon. Syst. 2022, 49, 1385–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, W.; Lai, C.H.; Wong, S.H.W.; Wong, M.L.D. Battery–supercapacitor hybrid energy storage system in standalone DC microgrids: A review. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2017, 11, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zegueur, A.; Sebbagh, T.; Metatla, A. A techno-economic study of a hybrid PV–wind–diesel standalone power system for a rural telecommunication station in Northeast Algeria. In ASEC 2023; MDPI: Basel, Switzerland, 2023; p. 25. [Google Scholar]

- Sebbagh, T. Modeling, analysis, and techno-economic assessment of a clean power conversion system with green hydrogen production. Bull. Pol. Acad. Sci. Tech. Sci. 2024, 72, 150115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, L.W.; Wong, Y.W.; Rajkumar, R.K.; Isa, D. Modelling and simulation of standalone PV systems with battery–supercapacitor hybrid energy storage system for a rural household. Energy Procedia 2017, 107, 232–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Li, C.; Li, B.; Guan, Z. Working principle analysis and control algorithm for bidirectional DC/DC converter. J. Power Technol. 2017, 97, 123–131. [Google Scholar]

- Machala, M.L.; Chen, X.; Bunke, S.P.; Forbes, G.; Yegizbay, A.; de Chalendar, J.A.; Azevedo, I.L.; Benson, S.; Tarpeh, W.A. Life cycle comparison of industrial-scale lithium-ion battery recycling and mining supply chains. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 6063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Z.; Wang, M.; Bai, Z.; Li, H.; Wang, N. Advances in lithium-ion battery recycling: Strategies, pathways, and technologies. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2025, 4, 30–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Tao, S.; Sun, X.; Ren, Y.; Sun, C.; Ji, G.; Xu, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Wu, Q.; et al. Pathway decisions for reuse and recycling of retired lithium-ion batteries considering economic and environmental functions. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Energy Storage: A Glimpse into the Future. Available online: https://compassenergystorage.com/future-of-energy-storage/ (accessed on 23 January 2026).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.