Abstract

The escalating development of Maritime Autonomous Surface Ships (MASS) has imposed rigorous demands on the precision, continuity, and resilience of onboard integrated navigation systems. However, in complicated marine settings, data from the Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) and Doppler Velocity Log (DVL) are frequently corrupted by multipath effects and non-line-of-sight (NLOS) interference. These disturbances introduce anomalous observations that violate Gaussian noise assumptions, thereby severely deteriorating the robustness and estimation quality of traditional sliding-window factor graph optimization (SW-FGO). To mitigate this problem, this study introduces a novel integrated navigation strategy termed gradient-adaptive factor graph optimization (GA-FGO). By designing a gradient-adaptive robust objective function within the factor graph structure, the proposed method dynamically re-weights constraints from the inertial navigation system (INS), GNSS, and DVL. This mechanism adequately suppresses the influence of measurement outliers at the optimization level. Furthermore, a unified solution framework utilizing iterative reweighted least squares (IRLS) and the Gauss–Newton method is established to simultaneously perform adaptive weight updates and state estimation. Validation was based on offline field data benchmarked against the Extended Kalman Filter (EKF), Unscented Kalman Filter (UKF), and standard SW-FGO. The simulation results demonstrated that the GA-FGO algorithm achieves superior positioning accuracy and estimation stability under realistic measurement conditions.

1. Introduction

With the advancement of intelligent shipping and the formal introduction of Maritime Autonomous Surface Ships (MASSs) by the International Maritime Organization (IMO), autonomous vessels are evolving toward highly autonomous operations [1]. In this context, onboard navigation systems are critical, as their outputs directly support autonomous decision-making, path planning, and motion control [2]. Consequently, MASS demands higher standards of navigation accuracy, continuity, and robustness than conventional manned ships. In practical maritime environments, navigation sensors are inevitably challenged by complex conditions. Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) signals are susceptible to blockage, multipath effects, and non-line-of-sight (NLOS) propagation; inertial navigation errors accumulate over time; and Doppler Velocity Log (DVL) performance may degrade in shallow or complex seabed environments [3]. If not properly handled, such anomalous measurements can propagate to the decision and control layers, resulting in unsafe or suboptimal maneuvers. Therefore, robustness against abnormal measurements has become a key requirement for MASS navigation systems. Traditional shipborne navigation systems, typically relying on a gyrocompass, GNSS, and DVL, lack sufficient redundancy and fault tolerance in complex environments. Hence, multi-sensor fusion-based integrated navigation systems have become essential for MASS, with robust navigation algorithms at their core [4].

For an extended period, integrated navigation systems on ships have predominantly relied on EKF for multi-sensor information fusion and state estimation [5]. EKF recursively updates the system state and its covariance using state and observation equations. However, when gross errors or anomalous measurements are present, the estimation noise covariance matrix can become biased, which markedly degrades the accuracy of state estimation. To overcome the limitations of EKF in nonlinear systems, nonlinear filtering approaches such as the Unscented Kalman Filter (UKF) [6] and the Cubature Kalman Filter (CKF) [7] have been widely studied and applied. However, nonlinear models often struggle to fully represent real-world systems due to inherent challenges such as model linearization and simplification, difficulties in accurately characterizing noise statistics, large initial state uncertainties, and variations in system parameters under different operating conditions. To address these limitations, adaptive filtering methods have gained increasing research interest. For instance, the Sage–Husa Adaptive Kalman Filter (SHAKF) [8] enhances adaptability to model uncertainties and environmental variations by estimating noise statistics online. Extending this approach, further improvements in filtering accuracy and system stability have been achieved through variable sliding-window estimation techniques [9] and refined adaptive factors [10,11,12]. In a relevant application, Liu et al. [13] proposed an improved adaptive robust EKF for Arctic shipborne tightly coupled navigation systems. Xiao et al. [14] developed an inertial navigation system and global positioning system (INS/GPS) integrated navigation method for unmanned surface vehicles based on ensemble empirical mode decomposition (EEMD) denoising and sparrow search algorithm and extreme learning machine (SSA-ELM). Additionally, Tang et al. [15] introduced a shipborne strapdown inertial navigation system and celestial navigation system (SINS/CNS) integrated navigation algorithm aided by long short-term memory (LSTM)-based attitude prediction.

The aforementioned Kalman filtering methods necessitate iterative updates of the entire system when addressing large-scale problems, leading to relatively high computational complexity [16]. Furthermore, the recursive update process in Kalman filtering relies on prior states and measurements, which restricts the flexibility to add or remove variables during operation. In contrast, factor graphs decompose complex problems into multiple factors and variables for large-scale systems and employ distributed inference, allowing different parts of the graph to be processed in parallel and thereby significantly enhancing computational efficiency [17,18,19,20]. Additionally, factor graphs enable flexible addition or removal of variables through modifications to the graph structure, supporting seamless integration and removal. Owing to their “plug-and-play” capability and high computational efficiency, factor graph-based methods have garnered considerable attention in the research community [21,22,23]. To better understand the advantages and limitations of these different approaches, Table 1 summarizes the key characteristics of various integrated navigation methods.

Table 1.

Comparison of different integrated navigation methods.

Integrated navigation systems based on factor graphs model the global state estimation problem as a sparse graph of local factors and state variables, thereby avoiding recursive updates of the entire state vector [24]. As a result, the Jacobian and information matrices exhibit inherent sparsity, which allows efficient solving via numerical methods such as sparse Cholesky or QR decomposition, significantly lowering computational complexity and improving numerical stability [25,26]. From an estimation framework perspective, factor graph optimization is formulated as a batch or incremental nonlinear least-squares framework, in which multiple factors are jointly optimized through iterative relinearization [27]. Compared with conventional recursive filtering methods, this approach can more effectively utilize multi-epoch information under strong nonlinearities and in the presence of anomalous measurements, yielding globally consistent state estimates with enhanced robustness. The factor graph structure supports asynchronous integration and flexible extension of different factor types and can be combined with parallel graph construction and optimization to further improve computational efficiency. To meet long-term online operation and real-time performance requirements, existing factor graph optimization methods often adopt fixed-length sliding-window factor graph (SW-FGO) or fixed-lag strategies. In these approaches, historical state information is compressed into prior factors via marginalization operations such as the Schur complement. This maintains continuity in the estimation process while effectively limiting the size of the optimization problem, thereby stabilizing computational complexity over time and making the method suitable for continuous operation in practical integrated navigation systems [28,29,30,31]. In terms of applications, Zhang et al. [32] proposed a factor graph optimization (FGO)-based AUV navigation method that integrates side-scan sonar. In the same year, Zhang et al. [33] further improved AUV navigation by optimizing side-scan sonar localization and developing an improved FGO-based post-processing model. Simulation and ocean experiments confirmed a significant improvement in overall mission trajectory accuracy. Tian et al. [34] proposed an adaptive fast incremental smoothing method for inertial navigation systems, global positioning systems, and visual odometer (INS/GPS/VO) factor graph inference. Zhang et al. [35] proposed a distributed navigation and fusion localization method for unmanned underwater vehicle (UUV) clusters. The method transforms individual UUV navigation data into an information-coupled probabilistic model to mitigate localization errors caused by temporal asynchrony. Li et al. [36] proposed a robust graph optimization-based INS, ultra-short baseline system, and DVL(INS/USBL/DVL) integrated navigation algorithm. Ben et al. [37] proposed a factor graph-based cooperative navigation algorithm for multiple autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) incorporating a node stretching strategy.

However, the onboard navigational environment of MASS is complex, and GNSS and DVL measurements are prone to adverse effects such as multipath propagation and NLOS conditions, which give rise to anomalous measurements (outliers) that significantly deviate from the Gaussian noise assumption. Under such circumstances, the assumption of strictly Gaussian-distributed observation noise adopted by standard SW-FGO methods no longer holds, thereby leading to a noticeable degradation in state estimation accuracy and robustness. To address the aforementioned issues, this study makes the following contributions:

- (1)

- Within the factor graph optimization framework, a gradient-adaptive robust objective function is proposed. Unlike conventional robust methods such as Huber loss or Tukey’s biweight function, which apply fixed thresholds regardless of measurement conditions, the proposed gradient-adaptive mechanism dynamically adjusts the weighting based on real-time residual statistics using MAD-based scale estimation. This enables automatic adaptation to varying noise conditions in maritime environments without manual parameter tuning. Furthermore, compared to switchable constraints that require binary outlier decisions, our continuous weighting scheme preserves partial information from degraded measurements while suppressing their adverse effects. The adaptive weighting mechanism based on normalized residuals is employed to dynamically reweight INS, GNSS, and DVL factors.

- (2)

- To solve this objective function, an iterative reweighted least squares (IRLS)-based Gauss–Newton solution framework is proposed. Within the framework, the factor weights and state estimates are iteratively updated based on the estimated motion state residuals.

- (3)

- To validate the effectiveness of the algorithm, simulations based on historical measured data were conducted to evaluate the state estimation accuracy and robustness of the EKF, UKF, SW-FGO, and gradient-adaptive factor graph optimization-based integrated navigation algorithm (GA-FGO) methods.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides an overview of the proposed method. In Section 3, we systematically present the theoretical innovations and methodological formulation of this study. In Section 4, the effectiveness and performance of the proposed approach are evaluated and analyzed based on offline data. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper and outlines directions for future research.

2. Preliminary Analysis

2.1. INS/DVL/GNSS Integrated Navigation Model for MASS

The motion state vector of the MASS INS/DVL/GNSS integrated navigation system is defined as

where , , and ; , , and represent the position coordinates in the North–East–Down (NED) coordinate system, respectively. , , and are the velocity values in the NED navigation coordinate system. , , and represent the Euler angles following the Z-Y-X rotation sequence: denotes the roll angle (rotation about the body’s longitudinal x-axis), denotes the pitch angle (rotation about the body’s lateral y-axis), and denotes the yaw or heading angle (rotation about the body’s vertical z-axis). These angles describe the vessel’s orientation relative to the local North–East–Down (NED) navigation frame.

In the integrated navigation processing process, the attitude transformation matrix can be expressed as

The direction cosine matrix from the body frame (b) to the navigation frame (n) is defined by the Z-Y-X Euler angle. , , .

On the basis of the inertial navigation mechanization equations, the motion constraint governing adjacent MASS states is constructed [38]. This constraint, which in turn yields the definitions for the position, velocity, and attitude state errors, is expressed as

where is the accelerometer measurement (body frame), is the gyroscope measurement (body frame), is the gravity acceleration vector, and is the sampling interval.

The residual matrix of the INS motion factor is set as

Regarding the observation model for the MASS INS/DVL/GNSS integrated navigation system, the observation functions for GNSS and DVL are, respectively, as follows. The observation noise for both sensors is assumed to follow a Gaussian distribution .

where and represent the GNSS position measurement and DVL velocity measurement at time step , respectively; and denote the corresponding measurement noise vectors; is the GNSS position noise covariance matrix with typical values of and ; is the DVL velocity noise covariance matrix in the body frame with ; and represents the direction cosine matrix transforming vectors from the body frame to the navigation frame.

The innovation can be written as

2.2. Factor Graph-Based Integrated Navigation Theory for MASS

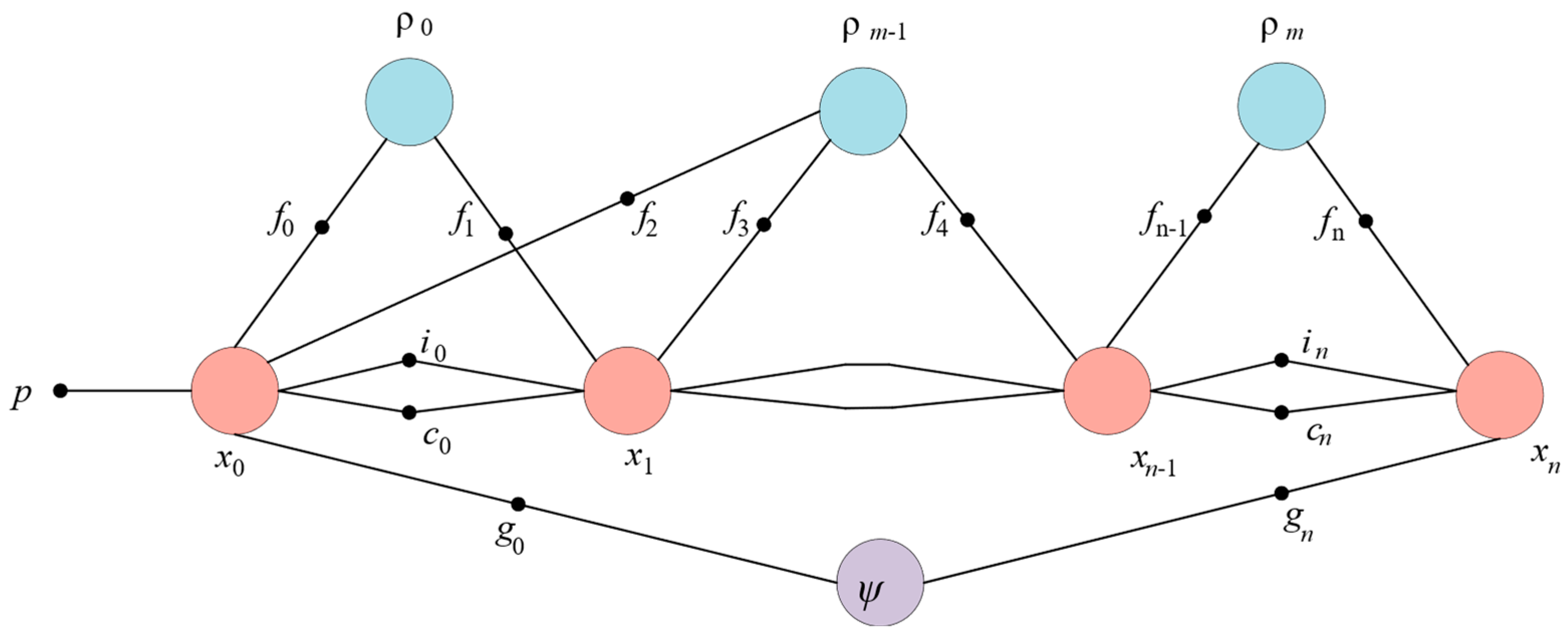

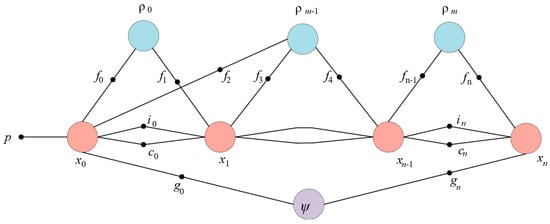

In the context of MASS integrated navigation, the factor graph provides a unified framework for fusing heterogeneous sensor measurements while accommodating their distinct noise characteristics and update rates. The factor graph is a bidirectional graph model where variable nodes represent the vessel’s motion states (position, velocity, and attitude) to be estimated at discrete time steps, factor nodes F encode the probabilistic constraints arising from INS mechanization, GNSS positioning, and DVL velocity measurements, and edges define the dependencies between states and observations. In the MASS integrated navigation system, variable nodes (denoted as , , , ) represent the 9-dimensional motion state vectors to be estimated at each epoch. The factor nodes encode specific measurement constraints: represent INS motion factors derived from IMU mechanization equations; denote GNSS position observation factors; indicate DVL velocity observation factors; represent IMU preintegration factors; and denote prior factors obtained through marginalization. The proposed method adopts a loosely coupled architecture at the state variable level, where GNSS provides position observations and DVL provides velocity observations, both fused with INS-propagated states through the factor graph optimization framework. This loosely coupled structure ensures computational efficiency while maintaining estimation accuracy. Figure 1 illustrates this factor graph formulation [39].

Figure 1.

Factor graph representation.

Given the observation set , the state estimation problem can be formulated as a maximum a posteriori (MAP) estimation:

According to Bayes’ theorem and the Markov assumption, the posterior probability can be factorized into a product of individual factors:

where denotes the factor function, and represents the subset of state variables associated with this factor. When the observation noise follows a Gaussian distribution, the factor function can be expressed as

Expanding the Mahalanobis norm yields

The residual is linearized via a first-order Taylor expansion around the estimate , and can be expressed by

The Jacobian matrix is , defining the stacked residual vector and the stacked Jacobian matrix ; the optimal increment is obtained by solving the normal equation, which can be written as

where is the block-diagonal information matrix. The Levenberg–Marquardt damping factor is introduced to enhance numerical stability as follows:

The state update is performed using the manifold addition operation:

The above motion state updates are typically realized by defining increments in the tangent space and mapping these increments back to the manifold via exponential or retraction mappings.

To enable real-time estimation, a sliding window of fixed length is adopted. As the window advances, the oldest state is marginalized into a prior factor via the Schur complement. Let the innovation matrix be block-partitioned with respect to the retained states and the marginalized states as

The prior innovation matrix and information vector after marginalization are given by

The residual of the prior factor is expressed as

where represents the prior mean obtained after marginalization and corresponds to the oldest state in the sliding window.

2.3. Standard Factor Graph Optimization Objective Function

By combining the above factors, the objective function of the standard SW-FGO is given as [40]

For a sliding window of length , the objective function represents a standard factor graph-based least-squares optimization model for the system states within a sliding window, where the states are jointly constrained by a prior factor, motion factors, and multiple observation factors. The prior factor is obtained through sliding-window marginalization and serves to preserve historical information and ensure estimation continuity; the motion factors characterize the dynamic evolution between consecutive states; the GNSS and DVL factors, respectively, incorporate external positioning and velocity observation constraints. Each residual term is weighted by the inverse of its corresponding noise covariance, thereby achieving maximum a posteriori estimation of the states within the sliding window in a statistical sense.

3. GA-FGO Algorithm

The standard SW-FGO operates under the assumption that observation noise strictly follows a Gaussian distribution. In practice, however, GNSS and DVL measurements in challenging environments such as underwater or urban canyons are frequently corrupted by multipath effects and NLOS propagation, resulting in significant outliers that violate the Gaussian assumption. Traditional least-squares estimation is highly sensitive to such outliers; even a single gross error can cause severe deviation of the state estimates from their true value.

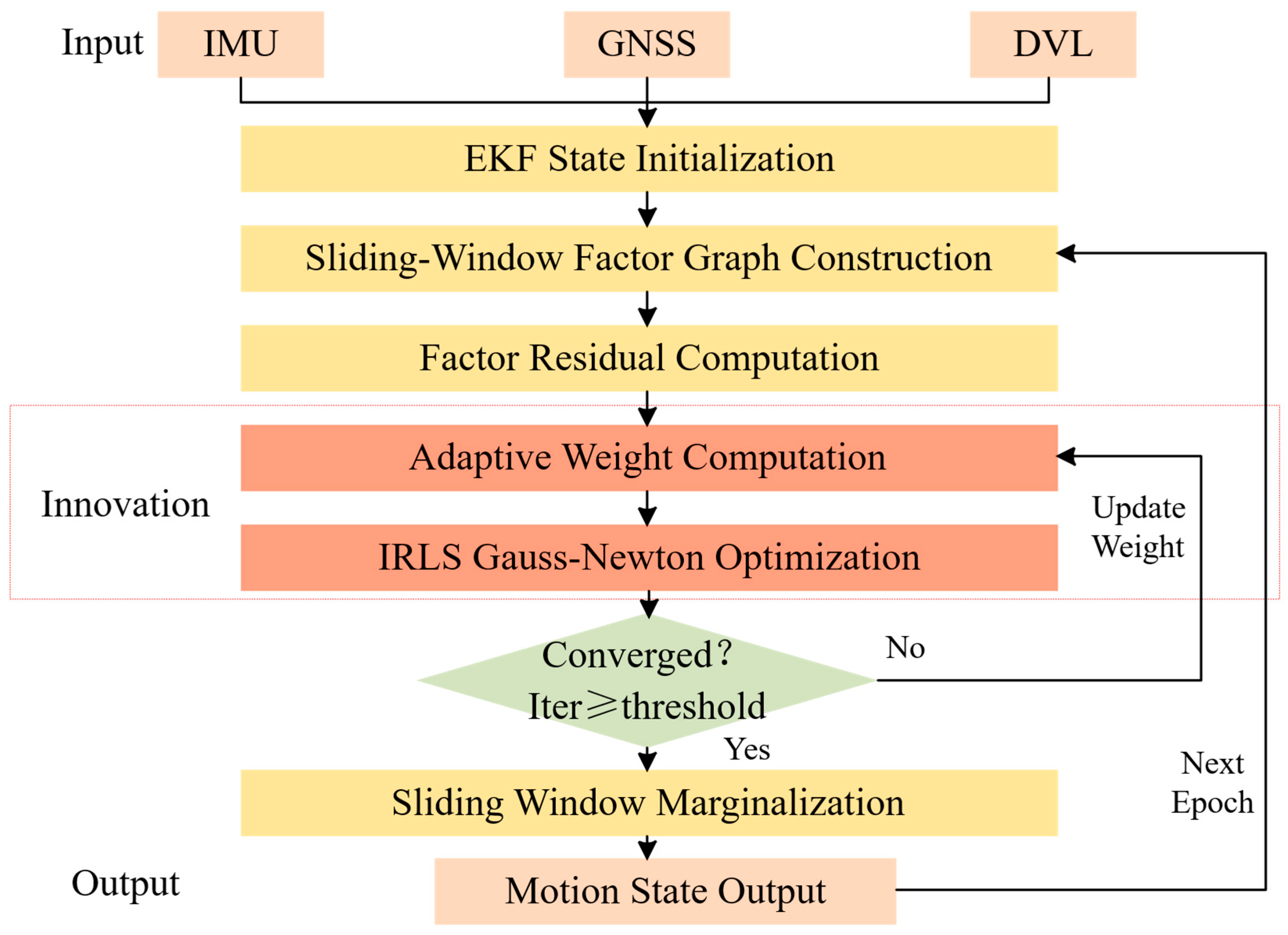

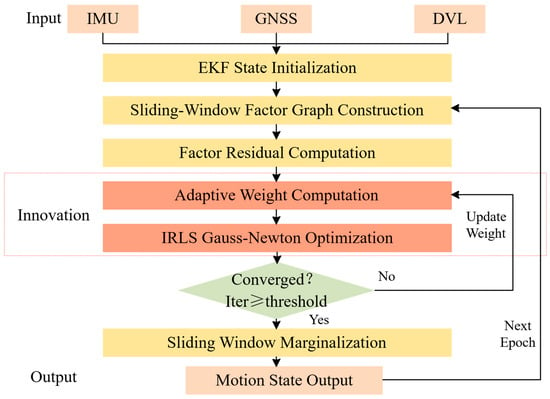

To mitigate these issues, we propose a GA-FGO algorithm, the core idea of which is to dynamically evaluate the quality of each factor’s residuals and adaptively adjust their weights, thereby suppressing the influence of anomalous measurements. The overall workflow of the algorithm is illustrated in Figure 2. First, the INS/GNSS/DVL integrated navigation system receives input data from sensors and performs state initialization using EKF. Next, a sliding-window factor graph is constructed, and the factor residuals are computed. Through adaptive weight calculation, combined with IRLS and Gauss–Newton optimization methods, the algorithm gradually optimizes the estimates. This process continues until the number of iterations reaches the convergence threshold (or the maximum iteration count , which are determined based on empirical convergence analysis and prior research on iterative optimization [27]. The convergence threshold ensures sufficient optimization accuracy while the iteration limit prevents excessive computation in real-time applications. The input observations include (1) IMU data comprising 3-axis accelerometer measurements and 3-axis gyroscope measurements sampled at 100 Hz; (2) GNSS position measurements in geodetic coordinates at 1 Hz; and (3) DVL velocity measurements in the body frame at 1 Hz. Finally, sliding-window marginalization is applied, and the optimized motion state is output, leading to enhanced navigation accuracy.

Figure 2.

The proposed algorithm and schematic of the innovation.

The main contribution of this study lies in the construction and optimization of the factor graph. Specifically, we focus on improving navigation performance by building a sliding-window factor graph and integrating it with an adaptive weighting strategy, solved via IRLS-based Gauss–Newton optimization.

3.1. Gradient-Adaptive Weight Factor Graph Optimization Objective Function

To enable unified anomaly detection across factors of varying dimensions, a normalized residual is first introduced. For the factor type at time step , the normalized residual is

Furthermore, the robust scale estimation adopts the Median Absolute Deviation (MAD):

where = 1.4826 is the consistency coefficient under a Gaussian distribution, = 0.1 is a numerical stability constant, and represents the median of the residuals within the window .

Subsequently, based on the robust kernel functions from M-estimation theory, an adaptive weighting mechanism based on a variant of the Geman–McClure function is designed.

Corresponding weight functions are then defined for the INS, GNSS, and DVL factors, each tailored to the distinct characteristics of these factor types.

In the formulation below, is the truncation function; and are scaling factors; , and are shape parameters of the kernel function; and is the lower bound of the weight. The parameters are set as follows: ; ; ; ; ; ; = 0.5. The scaling factors are determined based on the expected signal-to-noise ratio of each sensor type: GNSS measurements typically exhibit higher variability in maritime environments due to multipath effects; hence, a larger is assigned to provide greater tolerance. The shape parameters c control the transition rate of the weight function from full weight to minimum weight; smaller values result in more aggressive outlier rejection. Following the guidelines established in robust M-estimation theory [19], c values between 1.0 and 2.0 provide a balanced trade-off between statistical efficiency under nominal conditions and robustness against outliers. The larger for GNSS reflects its higher expected outlier rate in maritime environments. The lower bounds prevent complete rejection of measurements that may still contain useful information; the higher value of for GNSS reflects its critical importance as the primary absolute positioning reference.

For the adaptive weight functions introduced above, their behavior can be summarized as follows: when the residual is small , the corresponding weight approaches (clipped to 1); when the residual is large , the weight approaches , effectively suppressing the impact of anomalous observations. The inclusion of this lower bound prevents the complete discarding of measurements that may still retain useful information.

Building on these adaptive weights, the weighted information matrix and the overall objective function for GA-FGO are formulated. The weighted information matrix dynamically scales the contribution of each factor’s information matrix according to its assigned weight. The equivalent covariance matrix after weighting is defined as

The corresponding weighted residual is written as

Weight adjustment effectively introduces a non-Euclidean metric in the residual space:

Integrating the adaptive weighting algorithm described above, the complete objective function of GA-FGO is defined as

3.2. IRLS Gauss–Newton Resolving Framework

To solve for the state variables in the aforementioned objective function, an IRLS framework is adopted. The GA-FGO algorithm utilizes this IRLS framework for optimization, with its computational procedure outlined as Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1: GA-FGO |

| Input: Initial State Estimation , Observation set , Maximum number of iterations , Convergence threshold . |

| Output: Optimized state estimation |

| for to do |

| Calculate the residuals of all factors |

| Calculate robust scale estimation |

| Calculate the normalized residuals |

| Update the adaptive weights |

| Construct the weighted Jacobian matrix and the weighted residual vector |

| Solve the equation: |

| State Update: |

| Attitude Normalization: |

| if then break |

| End for |

| Return |

During the solution process, the special structure of the factor graph causes the Hessian matrix to exhibit a banded sparse pattern. Leveraging sparse Cholesky decomposition allows for the efficient and accurate solution of large-scale linear systems, significantly reducing both computational complexity and memory overhead. Here, denotes the lower triangular matrix obtained from the Cholesky decomposition, which can be expressed as follows

By solving for the increment via forward–backward substitution, we first perform forward substitution to obtain an intermediate vector , which satisfies

3.3. Convergence and Robustness Analysis

- (1)

- Convergence Analysis

In the IRLS framework, each iteration yields a monotonically decreasing value of the weighted objective function. Denote . The following relation can then be established:

Since the objective function is bounded below by zero and monotonically decreasing, the convergence of the algorithm to a local minimum is guaranteed.

The convergence rate of the IRLS algorithm depends on the Lipschitz continuity of the weight function. For the proposed Geman–McClure variant defined in Equation (21), the weight function is continuously differentiable with bounded derivatives for all , ensuring local Lipschitz continuity. Under mild regularity conditions, including positive definiteness of the Hessian approximation, the algorithm achieves a linear convergence rate with a contraction factor proportional to . Specifically, for , the theoretical contraction factor is approximately 0.77, indicating geometric convergence. In practice, convergence is typically achieved within 3–5 iterations for well-conditioned problems, as demonstrated in Section 4.3. The monotonic decrease property ensures that the algorithm will not diverge even in the presence of severe outliers, as the adaptive weights effectively bound the influence of anomalous measurements on the state update.

- (2)

- Robustness Analysis

Based on M-estimation theory, the influence function of GA-FGO is

The function describes the degree to which the observation affects the estimation result. Since , the function is bounded, ensuring that the estimator has a finite sensitivity to outliers. The breakdown point of the algorithm is

When , the GNSS factor can tolerate approximately 33% of gross error rate without causing estimation breakdown.

4. Simulation Results and Discussion

4.1. Simulation Environments

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed algorithm, offline experimental data collected during a sea trial in a typical coastal environment were utilized. Throughout the trial, the vessel performed a series of maneuvers—including steady-state cruising and high-dynamic turns—to comprehensively assess algorithm performance across varied motion conditions.

As shown in Table 2, the data-collection platform was equipped with an Inertial Labs Motion Reference Unit (MRU), a high-performance strapdown inertial system with a sampling rate of 100 Hz. Under stable operating conditions, its accelerometer bias is 0.005 mg and its gyroscope bias is 1°/μt. A GNSS RTK receiver provided centimeter-level ground-truth positioning for algorithm evaluation [41]. Additionally, a separate single-point positioning (SPP) GNSS receiver was installed to provide the navigation input measurements used by all evaluated algorithms. The SPP receiver operates at 1 Hz with a nominal horizontal accuracy of 2.5 m CEP (Circular Error Probable), which represents typical maritime GNSS conditions subject to multipath propagation and atmospheric effects. This dual-receiver configuration ensures that all algorithms are evaluated under identical, realistic measurement conditions while maintaining accurate ground-truth reference. To ensure precise temporal consistency among these heterogeneous sensors, a high-accuracy synchronization mechanism was implemented, using the Pulse Per Second (PPS) signal and National Marine Electronics Association (NMEA) messages from the GNSS receiver to synchronize the time-stamps of the MRU and DVL data to the microsecond level. Additionally, the Teledyne RD Instruments (RDI) Work Horse DVL was also installed, capable of seabed tracking at depths ranging from 0.5 m to 200 m. This DVL measures velocity in three degrees of freedom, with a speed measurement range of ±10 m/s, a resolution of 0.001 m/s, and an accuracy of 0.008 m/s. The DVL operates at a sampling rate of 1 Hz.

Table 2.

Sensor specifications.

Furthermore, the spatial lever-arm offsets between the GNSS antenna phase center, the MRU measurement center, and the DVL acoustic center were meticulously calibrated and compensated for, ensuring that all multi-source observations were accurately transformed into a unified vessel-fixed coordinate system. However, Table 3 presents a comprehensive comparison of computational metrics including processing time and memory consumption across all of the evaluated algorithms. EKF demonstrates an optimal computational speed, while SW-FGO and GA-FGO achieve slightly higher computational rates than UKF, though at the cost of greater memory consumption.

Table 3.

Computational complexity comparison table.

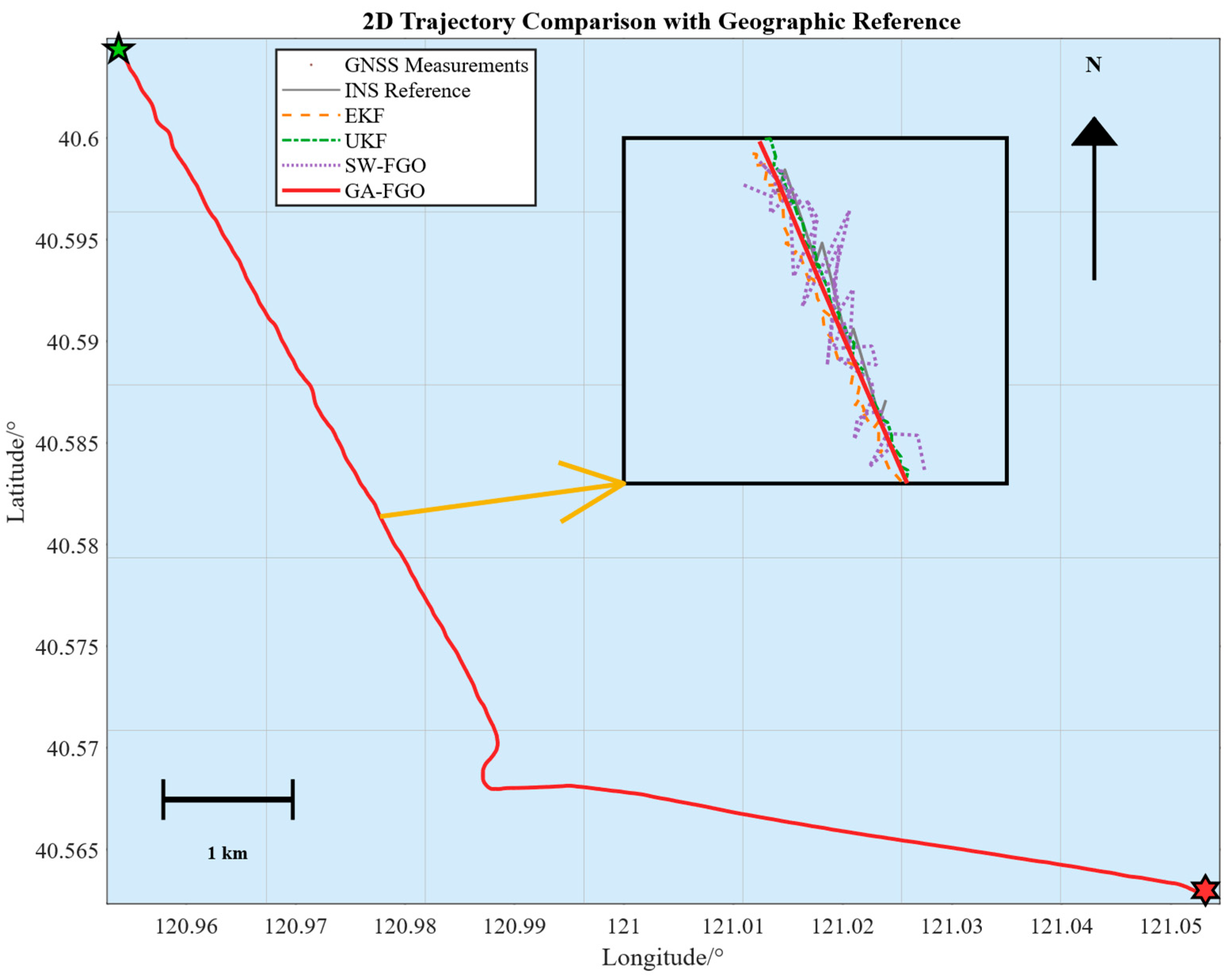

4.2. Comparative Analysis of Navigation Performance

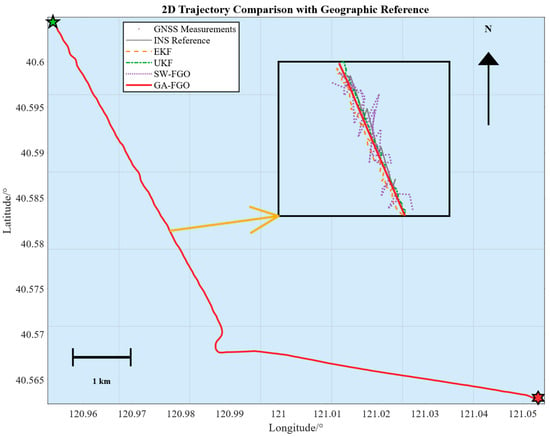

Figure 3 compares the test trajectories obtained from four algorithms for the shipborne INS/GNSS/DVL integrated navigation system: EKF and UKF, the standard SW-FGO, and the proposed GA-FGO. The green and red star-shaped markers indicate the starting point and endpoint of the simulation, respectively. The selected trajectory represents a typical maritime transit scenario, which includes both long-range steady cruising and tactical maneuvering segments, thereby providing a rigorous benchmark for evaluating the convergence and tracking agility of the integrated system. Relative to the black curve representing the ground truth trajectory, SW-FGO shows relatively large positioning errors, while the proposed GA-FGO achieves higher accuracy than both EKF and UKF. A closer inspection of the magnified sub-window in Figure 2 reveals that when GNSS measurements (scattered dots) contain noticeable noise or outliers, the filtering-based methods tend to fluctuate with these erroneous observations. In contrast, the proposed GA-FGO yields a much smoother trajectory that closely follows the reference, confirming its improved capability to suppress non-Gaussian measurement noise. Moreover, GA-FGO delivers the most stable trajectory estimate among all four algorithms. This visual consistency underscores that the gradient-adaptive optimization effectively balances high-frequency INS data against intermittent GNSS updates, preventing the state estimate from being biased by transient sensor degradation.

Figure 3.

Trajectories of the four evaluated methods. The green and red star-shaped markers indicate the starting point and endpoint of the simulation, respectively.

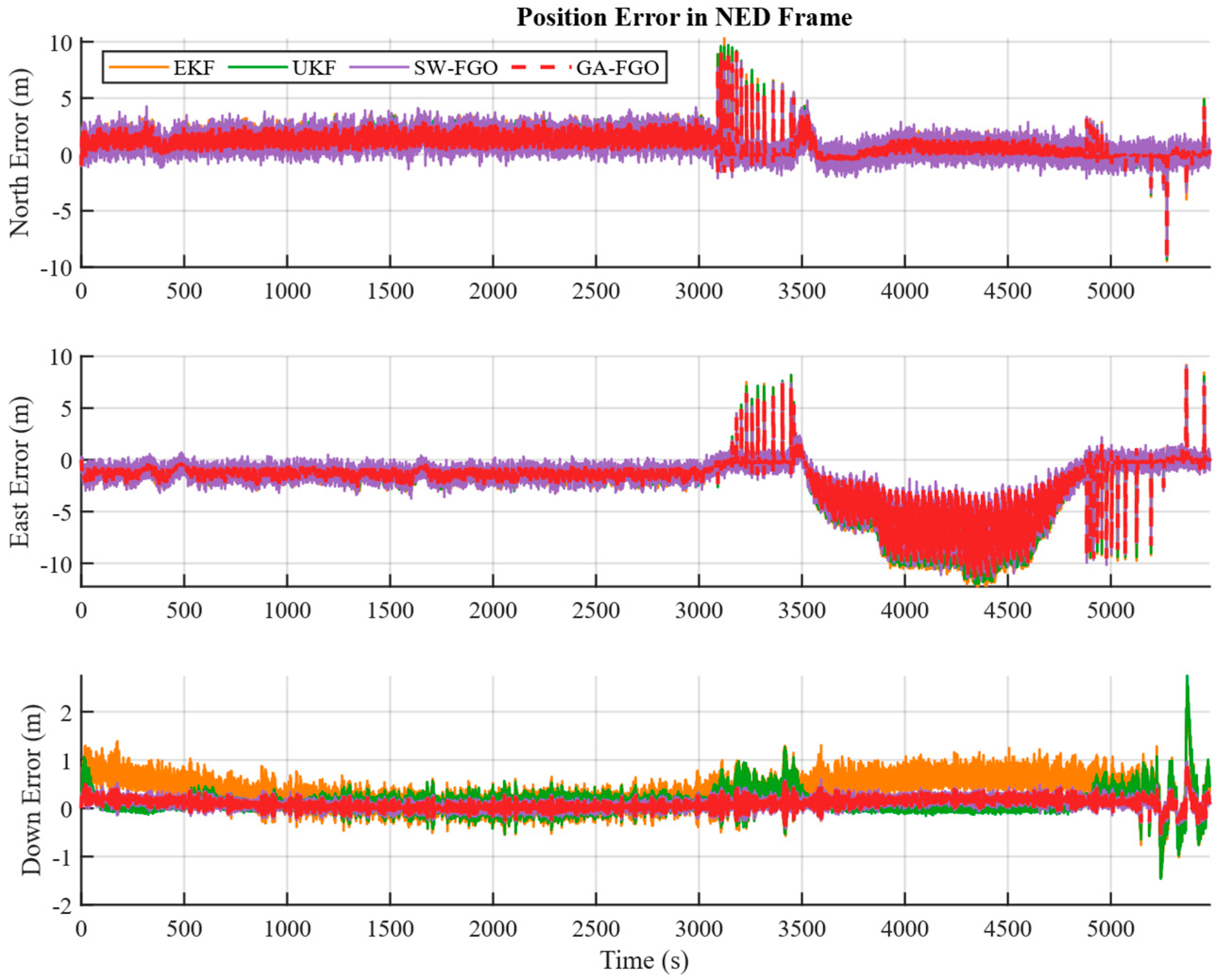

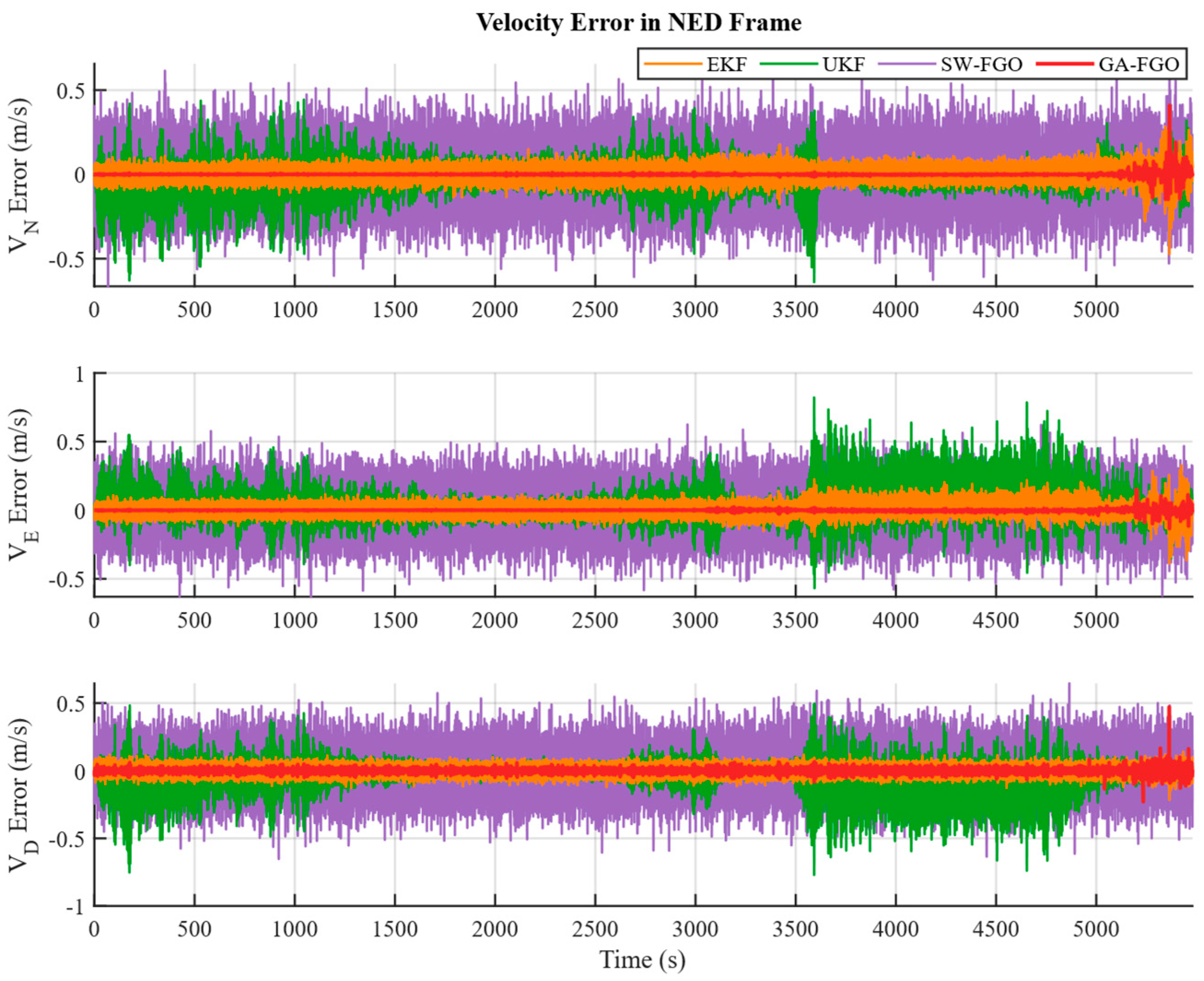

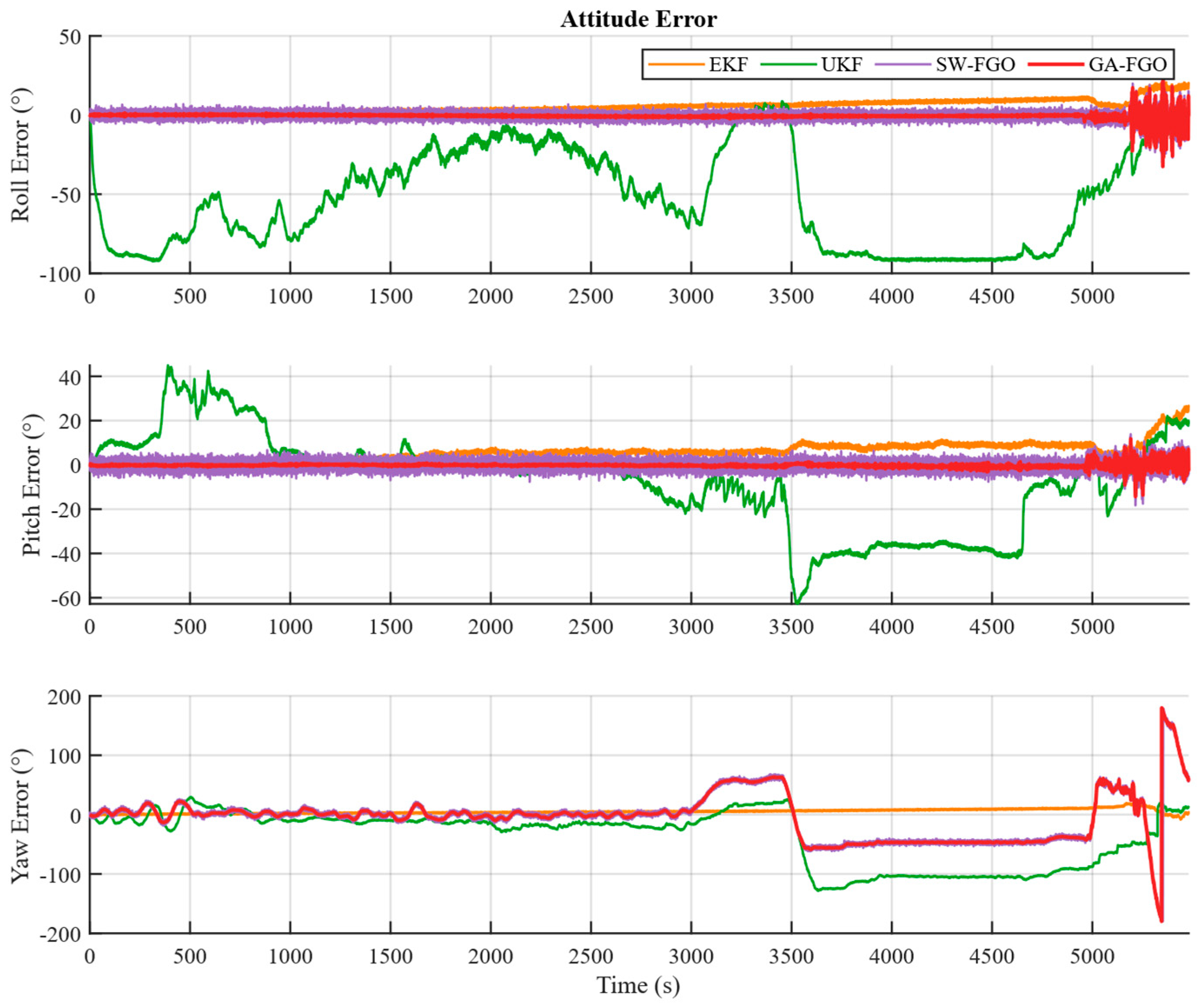

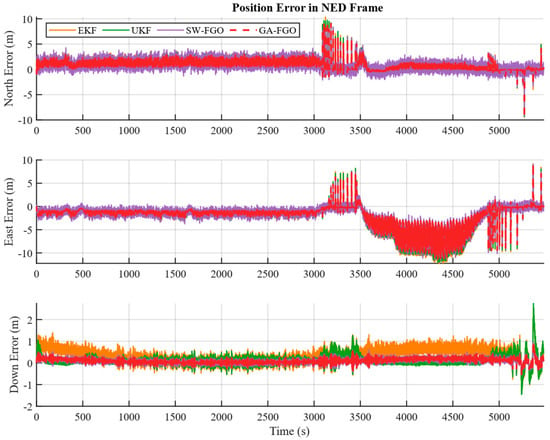

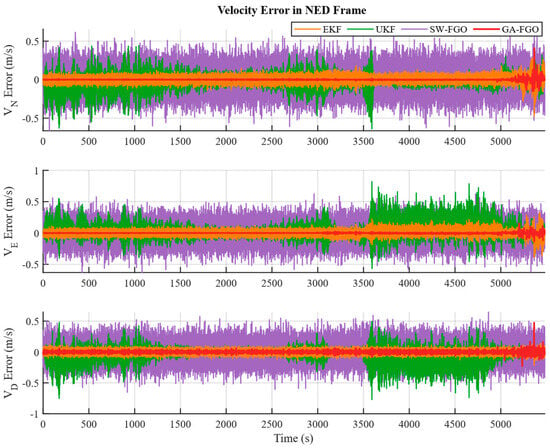

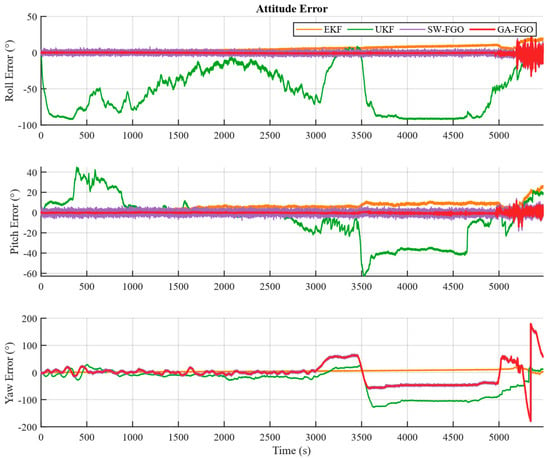

Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6 present the position, velocity, and attitude errors of the shipborne INS/GNSS/DVL integrated navigation system obtained with the EKF, UKF, SW-FGO, and the proposed GA-FGO algorithms. The time-history curves offer a detailed view of the system’s convergence behavior and its sensitivity to transient sensor faults over the 6000 s voyage. The eastward and northward position errors show noticeable fluctuations in the interval from 3000 s to 5000 s. During this interval, the north and east position errors of the conventional filters exceed 8 m, while GA-FGO confines the deviations within a much tighter bound. Although GA-FGO exhibits larger fluctuations than SW-FGO from 3000 s to 3500 s, its overall position error remains the lowest. This result suggests that GA-FGO’s adaptive weighting strategy prioritizes long-term trajectory consistency over instantaneous smoothness, thereby preventing error accumulation during transitions in sensor reliability. The observed fluctuations in the 3000–3500 s interval merit further discussion. These transient variations are attributed to the adaptive weight adjustment mechanism responding to rapid changes in GNSS measurement quality during this period. During transitions between reliable and degraded GNSS conditions, the gradient-adaptive weights undergo frequent updates to track the changing measurement statistics. This responsive behavior is not an inherent limitation of the proposed method but rather a characteristic of its adaptive nature. The fluctuations diminish as the robust scale estimate stabilizes after approximately 500 s of consistent measurement conditions. Importantly, the long-term trajectory consistency and the lowest overall RMSE demonstrate that this short-term variability does not compromise navigation accuracy. In contrast, SW-FGO’s smoother appearance during this interval comes at the cost of accumulated bias, as it cannot adequately suppress the influence of outliers. For the velocity errors, the advantage of the proposed method is particularly clear. GA-FGO achieves the best performance among all four algorithms in both error magnitude and fluctuation behavior, with three-axis velocity errors consistently near zero at a precision of about 0.05 m/s. In contrast, the filter-based methods show noticeable jitter induced by measurement noise. Regarding attitude estimation, although the yaw error of GA-FGO fluctuates more toward the end of the trial—performing poorer than EKF in this segment—the overall attitude accuracy is improved compared to SW-FGO. Moreover, while UKF suffers from severe divergence in roll and pitch after 3500 s, GA-FGO maintains stable attitude tracking throughout the entire mission.

Figure 4.

Comparison of position error estimation for shipborne INS/GNSS/DVL integrated navigation system based on four algorithms.

Figure 5.

Comparison of velocity error estimation for shipborne INS/GNSS/DVL integrated navigation system based on four algorithms.

Figure 6.

Comparison of attitude error estimation for shipborne INS/GNSS/DVL integrated navigation system based on four algorithms.

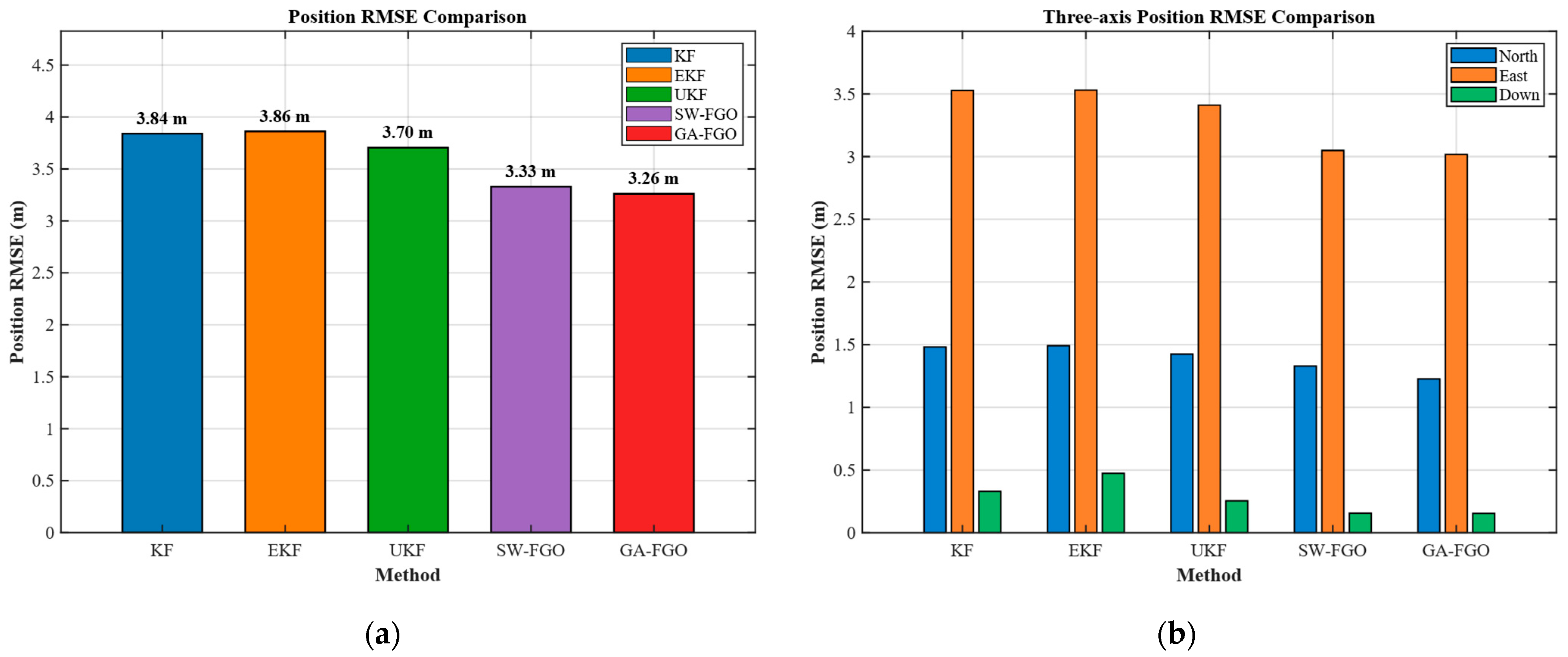

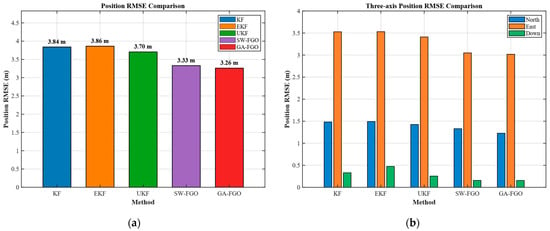

Figure 7 presents a comparative analysis of the position Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) performance of KF, EKF, UKF, SW-FGO, and the proposed GA-FGO. RMSE quantifies the cumulative positioning deviation over the entire test duration, offering a robust measure of long-term navigation reliability. Specifically, the left panel of Figure 6 shows the overall position RMSE, providing a global comparison of the positioning accuracy achieved by different methods. The RMSE values for KF and EKF are 3.84 m and 3.86 m, respectively, whereas GA-FGO achieves a superior precision of 3.26 m. The right panel of Figure 6 further decomposes the position errors into the North, East, and Down components, revealing the directional distribution characteristics of the estimation errors. In Figure 7b, it is evident that the East error dominates the total position RMSE across all algorithms, whereas the Down component remains the most stable, likely due to the altitude constraints provided by the multi-sensor fusion. The results indicate that factor graph-based methods consistently outperform traditional filtering approaches. Both SW-FGO and GA-FGO achieve significantly lower position RMSE than KF, EKF, and UKF. This improvement stems from the ability of factor graphs to perform nonlinear optimization over multiple states simultaneously, which allows the system to correct prior estimation biases through a broader information horizon. Unlike filters that discard past measurements after one update, the sliding-window strategy retains a history of constraints, enabling the re-evaluation of sensor data when the ship transitions between different maneuvering phases. Notably, the proposed GA-FGO attains the smallest overall position RMSE among all methods, demonstrating further accuracy gains over the standard SW-FGO.

Figure 7.

Position RMSE comparison for INS/GNSS/DVL integrated navigation system: (a) position RMSE comparison; (b) three-axis position RMSE comparison.

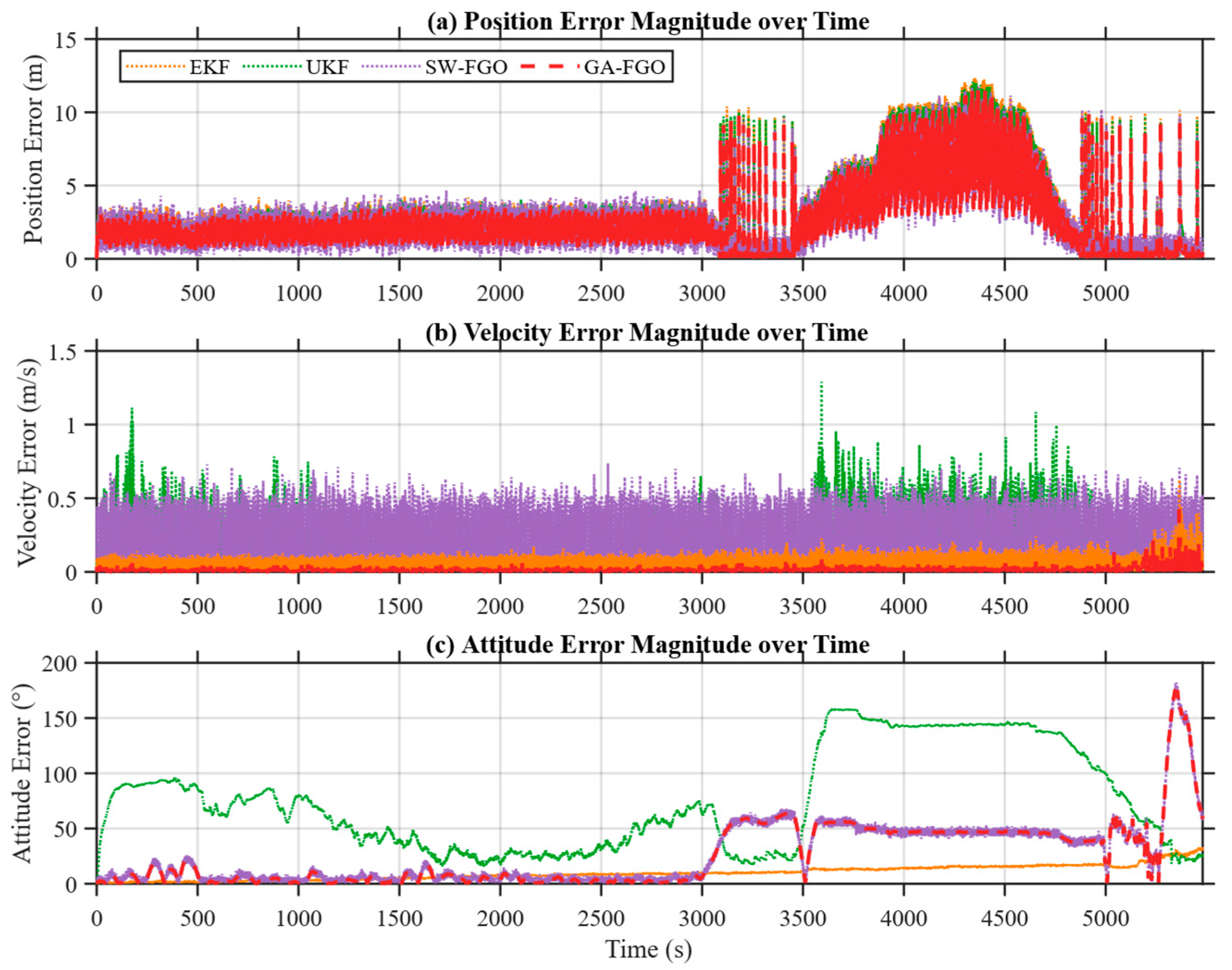

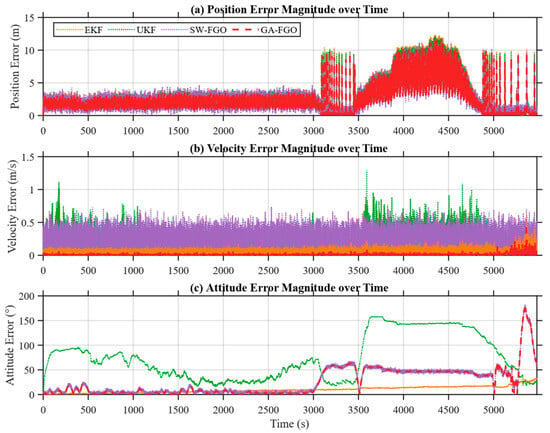

Figure 8 compares the time histories of velocity, position, and attitude (roll, pitch, and yaw) error magnitudes for EKF, UKF, SW-FGO, and the proposed GA-FGO. This time-series view offers a detailed look at the convergence behavior and sensitivity to transient sensor faults during the 6000 s voyage. The results show that GA-FGO maintains the smallest velocity and position error magnitudes throughout the test. Specifically, during simulated GNSS degradation intervals between 3200 s and 4800 s, the position error of GA-FGO remains tightly bounded, whereas EKF and UKF exhibit dramatic spikes exceeding 10 m. GA-FGO also effectively suppresses error fluctuations caused by anomalous measurements, demonstrating stronger robustness than EKF, UKF, and SW-FGO. The velocity error profile of the proposed method is notably smoother, consistently staying near zero with minimal variance, which is critical for the precise dead-reckoning required during GNSS-denied periods. In terms of attitude estimation, GA-FGO delivers stable and accurate roll and pitch estimates, avoiding the pronounced divergence observed in UKF. The UKF attitude error grows to nearly 150° after 3500 s, highlighting the vulnerability of traditional filters to prolonged non-Gaussian noise—a scenario in which our factor-graph approach maintains stability through iterative re-linearization. Although some fluctuations appear in the yaw error toward the end of the test, the overall attitude estimation performance of GA-FGO remains superior to that of SW-FGO and is significantly better than that of traditional filtering methods.

Figure 8.

Position, velocity, and attitude error magnitudes for INS/GNSS/DVL integrated navigation system.

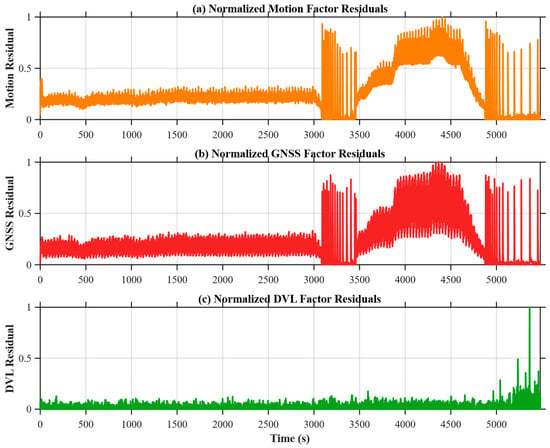

4.3. Analysis of Gradient-Adaptive Mechanism

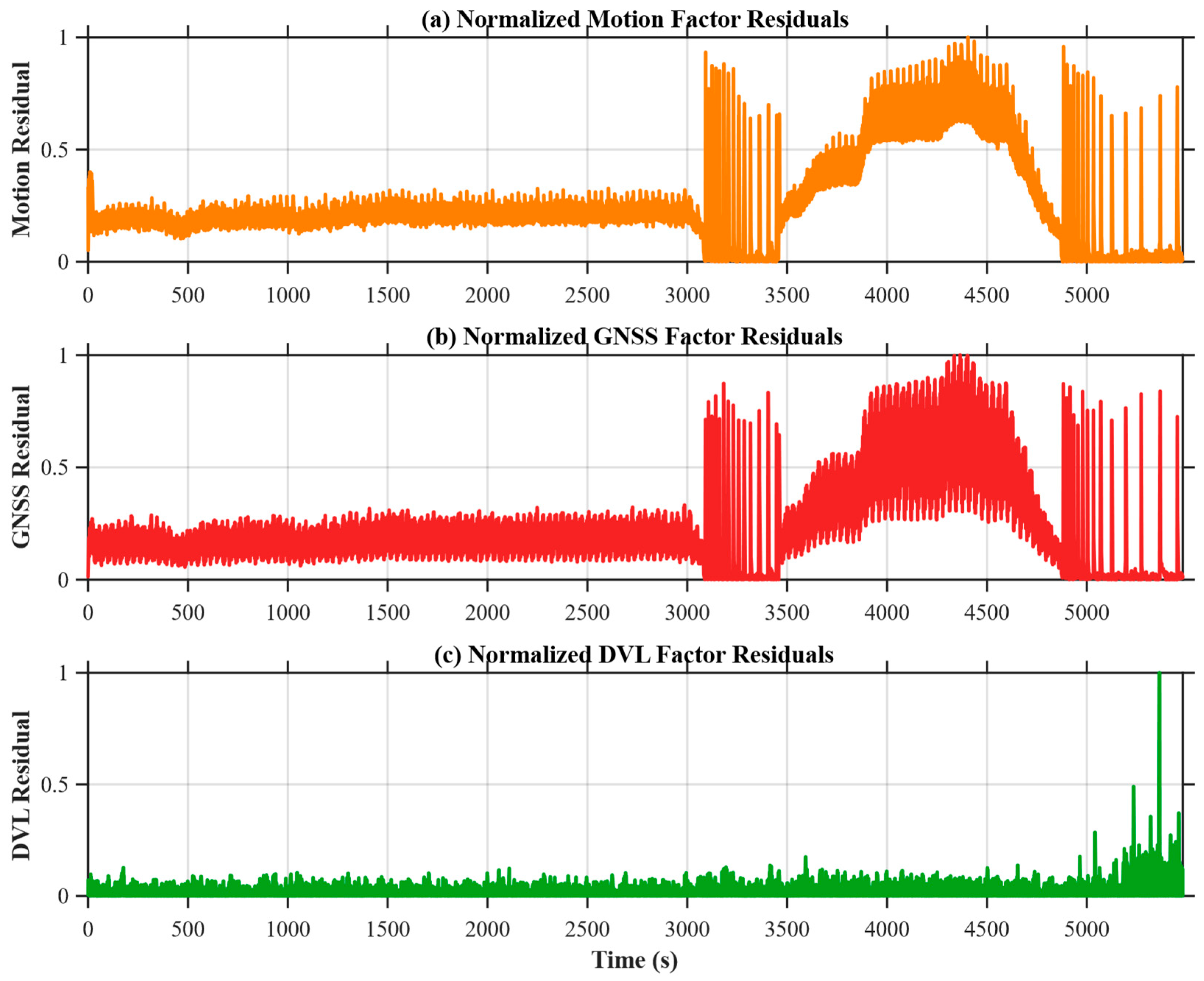

Figure 9 illustrates the normalized factor residuals within the GA-FGO framework, including those of the motion, GNSS, and DVL factors. Monitoring these normalized residuals is fundamental to GA-FGO, as it provides a real-time diagnostic tool for assessing the reliability of individual sensor observations. During nominal operation, all residuals remain at relatively low and stable levels, indicating good consistency across multi-sensor measurements. When anomalous conditions arise, pronounced increases and fluctuations are observed in the GNSS and motion residuals, reflecting the presence of outliers and a decline in measurement quality. This discrepancy among sensor modalities is effectively captured by the optimizer, enabling the system to distinguish between high-fidelity and degraded information sources. In contrast, the DVL residual remains comparatively stable throughout; its consistently low magnitude reinforces its role as a reliable velocity anchor, providing a critical reference that allows the gradient-adaptive mechanism to down-weight erroneous GNSS factors without compromising global state observability.

Figure 9.

Normalized factor residuals in GA-FGO in INS/GNSS/DVL integrated navigation system.

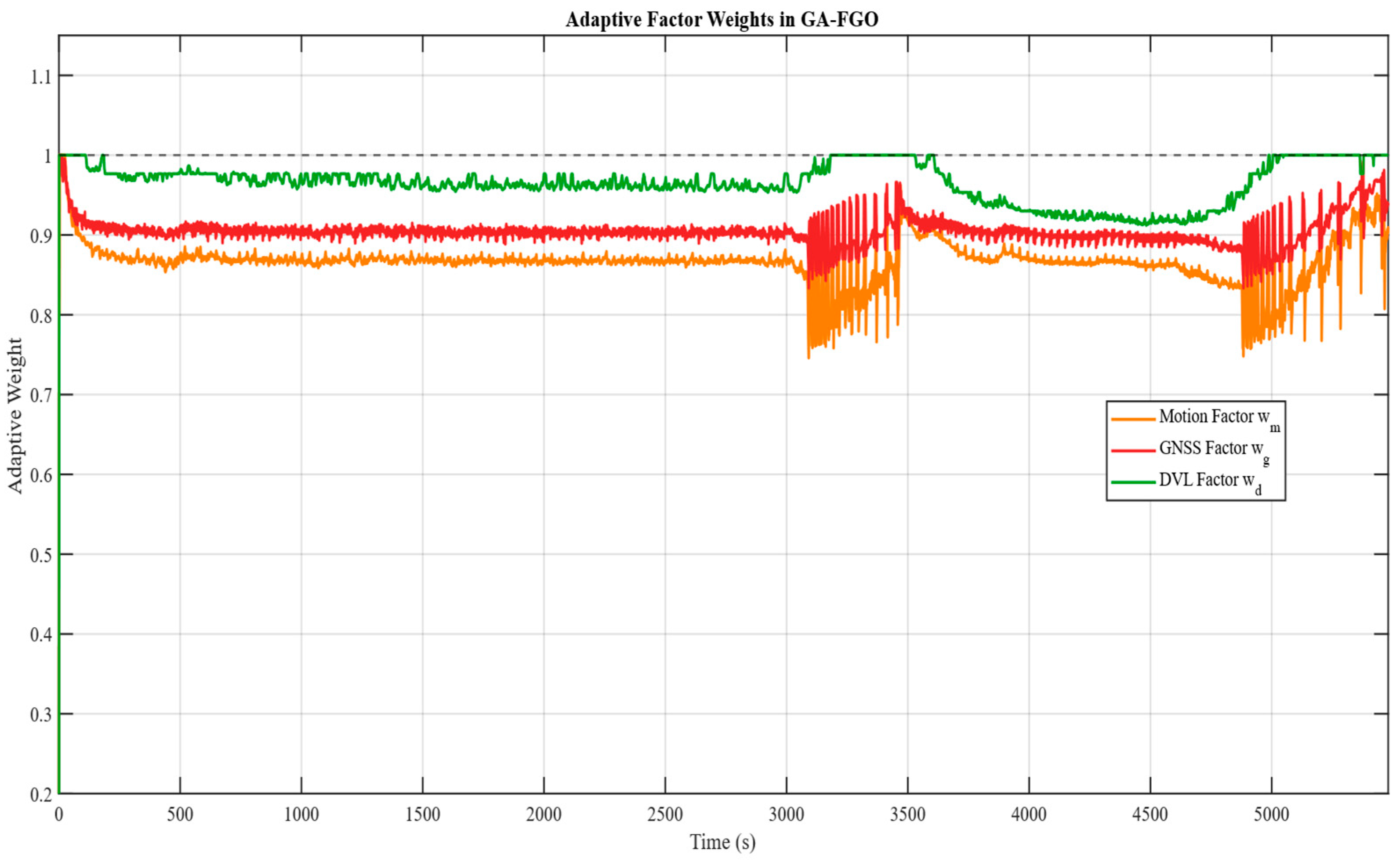

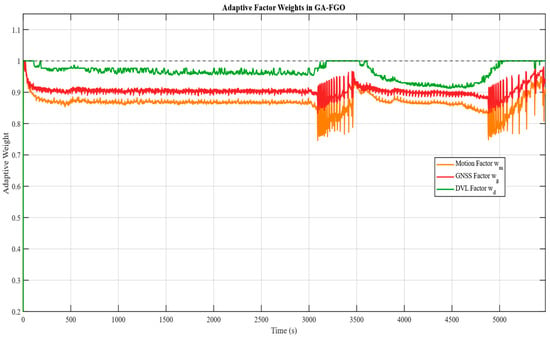

Benefiting from the gradient-adaptive residual evaluation mechanism, these large residuals are effectively identified and down-weighted during the optimization process, thereby preventing them from dominating the state estimation; the corresponding weight allocation results are shown in Figure 10. Specifically, the adaptive weights are inversely coupled with the normalized residual magnitudes, ensuring that any sensor factor exhibiting anomalous innovations is automatically assigned a lower confidence level in the global optimization.

Figure 10.

Weight allocation for measurements from different sensors during the test period.

Furthermore, Figure 9 illustrates the weight allocation for measurements from different sensors based on Equation (21). It is clearly observed that the DVL factor (green curve) maintains a consistently high weight near 1.0 throughout the majority of the test, validating its role as a stable reference when other sensors degrade. This mechanism evaluates each factor’s residual quality, adaptively increasing the weight of reliable INS information to suppress anomalous observations and enhance system robustness.

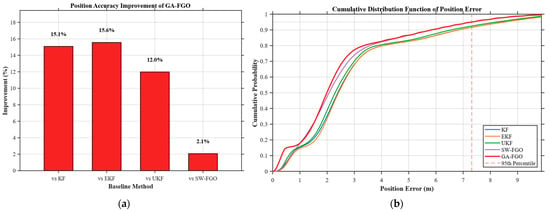

4.4. Comprehensive Statistical Evaluation

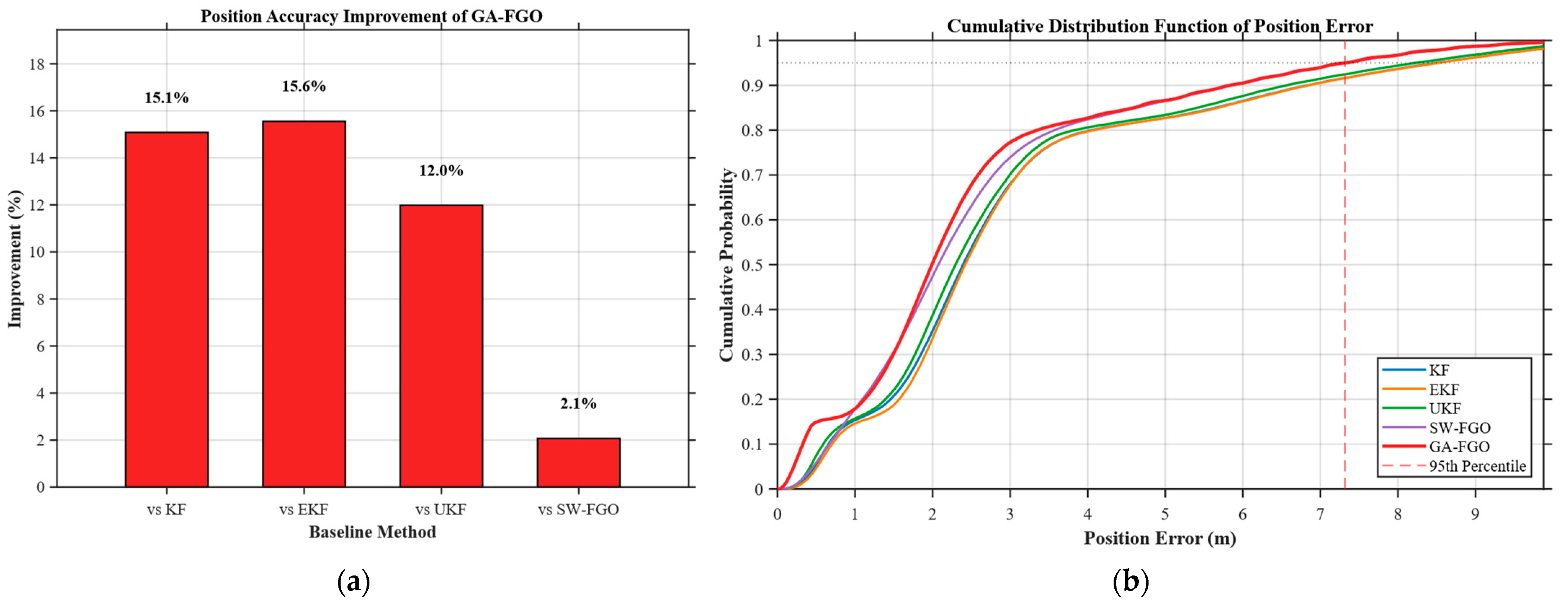

Figure 11 presents a comprehensive evaluation of the positioning performance of the proposed GA-FGO, focusing on relative improvement and statistical error distribution. While the relative improvement quantifies the average gain in accuracy, the cumulative distribution function (CDF) offers deeper insight into error bounds and the system’s resilience against extreme outliers. As shown in the left subfigure, GA-FGO improves position accuracy by 15.1%, 15.6%, and 12.0% compared to KF, EKF, and UKF, respectively, and achieves a further 2.1% improvement over SW-FGO. This demonstrates the effectiveness of the gradient-adaptive weighting mechanism within the factor graph framework. The notable performance gap between GA-FGO and the filtering-based methods underscores the inherent limitations of the Markov assumption in traditional filters, which often struggle with the non-Gaussian noise common in maritime environments. Furthermore, the 2.1% improvement over the standard SW-FGO suggests that the gradient-adaptive mechanism effectively optimizes the factor weights, extracting additional precision even from already high-performing factor graph baselines. Meanwhile, the CDF of the position error, as shown in the right subfigure, reveals that GA-FGO attains higher cumulative probabilities across the entire error range and substantially reduces the occurrence of large errors, especially in medium-to-high-confidence regions. Notably, at the 95% confidence level, GA-FGO constrains position error within a much tighter bound than EKF and UKF, reflecting a significant reduction in the worst-case error magnitude. These results confirm that GA-FGO not only improves average positioning accuracy but also enhances system stability and robustness from a statistical perspective.

Figure 11.

Positioning performance evaluation of INS/GNSS/DVL integrated navigation system based on GA-FGO: (a) relative position accuracy improvement; (b) position error CD.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we present a GA-FGO algorithm to improve the robustness of shipborne INS/GNSS/DVL integrated navigation for MASS in complex maritime environments, particularly against anomalous measurements. By integrating a gradient-adaptive weighting mechanism into a sliding-window factor graph framework, a robust optimization objective is formulated. This is solved through an IRLS-based Gauss–Newton framework that unifies weight updating, state estimation, and marginalization into an iterative process. The theoretical analysis confirms the convergence and robustness of the proposed method, which is characterized by a bounded influence function. The simulation results based on measured offline data demonstrate that GA-FGO outperforms EKF, UKF, and standard SW-FGO in terms of position, velocity, and attitude estimation accuracy. The proposed approach enhances robustness against non-Gaussian noise while preserving the global consistency and computational efficiency of factor graph optimization, offering a practical solution for MASS integrated navigation in challenging operational environments.

Future research will focus on extending the proposed factor graph framework to incorporate additional perception sensors, such as LiDAR and visual cameras, to further enhance navigational redundancy in GNSS-denied environments. Additionally, we plan to optimize the algorithm for embedded computing platforms to validate its real-time performance and long-term reliability during autonomous sea trials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.G. and L.W.; methodology, M.G. and L.W.; software, M.G. and L.W.; validation, M.G. and L.W.; formal analysis, M.G., L.W., B.W. and M.Z.; investigation, M.G., L.W., B.W. and M.Z.; resources, M.G., L.W., B.W. and M.Z.; data curation, M.G., L.W., B.W. and M.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, M.G. and L.W.; writing—review and editing, B.W., H.L., C.Z. and M.Z.; visualization, B.W., H.L., C.Z. and M.Z.; supervision, M.G.; project administration, M.G.; funding acquisition, M.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the Fundamental Research Funds of the Education Department of Liaoning Province in 2023 (JYTMS20230172 and JYTMS20230175), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (3132025133), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2024M750296), the Young Scientists Fund of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (83125040), and the Liaoning Provincial Doctoral Scientific Research Start-up Fund (84250059).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the editors and anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions to improve the presentation of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sezer, S.I.; Ahn, S.I.; Akyuz, E.; Kurt, R.E.; Gardoni, P. A hybrid human reliability analysis approach for a remotely-controlled maritime autonomous surface ship (MASS-degree 3) operation. Appl. Ocean Res. 2024, 147, 103966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; He, Y.; Zhao, X.; Xu, K. Testing method of autonomous navigation systems for ships based on virtual-reality integration scenarios. Ocean Eng. 2024, 309, 118597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Zhou, X.; Guo, C.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Bai, W. Adaptive federated filter–combined navigation algorithm based on observability sharing factor for maritime autonomous surface ships. J. Mar. Eng. Technol. 2024, 23, 98–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, Z.; Jiang, G.; Guo, H.; Zhu, W. A hybrid data-driven and learning-based method for de-noising low-cost IMU to enhance ship navigation reliability. Ocean Eng. 2024, 299, 117280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khater, H.A.; Elsayed, A.; El-Shoafy, N. Improved navigation and guidance system of AUV using sensors fusion. J. Commun. 2020, 6, 455–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, E.A.; Van Der Merwe, R. The unscented Kalman filter for nonlinear estimation. In Proceedings of the Adaptive Systems for Signal Processing, Communications, and Control Symposium, Lake Louise, AB, Canada, 1–4 October 2000; pp. 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arasaratnam, I.; Haykin, S. Cubature kalman filters. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2009, 54, 1254–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.H.; Schwarz, K.P. Adaptive Kalman filtering for INS/GPS. J. Geod. 1999, 4, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; He, H.; Xu, G. Adaptively robust filtering for kinematic geodetic positioning. J. Geod. 2001, 75, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Gao, W. An optimal adaptive Kalman filter. J. Geod. 2006, 4, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xu, T. An adaptive Kalman filter based on Sage windowing weights and variance components. J. Navig. 2003, 2, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Yang, Y. Adaptively robust filtering with classified adaptive factors. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 2006, 8, 846–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Qi, T.; Hu, Y.; Fu, S.; Han, B.; Hsieh, T.-H.; Wang, S. An Improved Adaptive Robust Extended Kalman Filter for Arctic Shipborne Tightly Coupled GNSS/INS Navigation. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Z. INS/GPS Integrated Navigation for Unmanned Ships Based on EEMD Noise Reduction and SSA-ELM. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Bian, H. Ship SINS/CNS Integrated Navigation Aided by LSTM Attitude Forecast. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Dai, H.; Li, J.; Li, X.; Liu, X. Dynamic Feature Elimination-Based Visual–Inertial Navigation Algorithm. Sensors 2026, 26, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X. Loosely coupled GNSS/INS integration based on factor graph and aided by ARIMA model. IEEE Sens. J. 2021, 21, 24379–24387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Lai, J.; Lyu, P.; Ji, B.; Wang, B.; Sun, X. A novel plug-and-play factor graph method for asynchronous absolute/relative measurements fusion in multi sensor positioning. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2022, 70, 940–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, W.; Zhang, G.; Hsu, L.-T. GNSS outlier mitigation via graduated non-convexity factor graph optimization. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2021, 71, 297–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; He, K.; Wang, Z.; Yang, H.; Zheng, J. Research on INS/GNSS Integrated Navigation Algorithm for Autonomous Vehicles Based on Pseudo-Range Single Point Positioning. Electronics 2025, 14, 3048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grenier, A.; Lohan, E.S.; Ometov, A.; Nurmi, J. Towards Smarter Positioning through Analyzing Raw GNSS and Multi-Sensor Data from Android Devices: A Dataset and an Open-Source Application. Electronics 2023, 12, 4781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Hsu, L.-T.; Zhang, T. A novel INS/USBL integrated navigation scheme via factor graph optimization. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2022, 71, 9239–9249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, M.; Yan, P.; Wang, Q.; Xie, D.; Bai, Y.B. Cross-Path Planning of UAV Cluster Low-Altitude Flight Based on Inertial Navigation Combined with GPS Localization. Electronics 2025, 14, 2877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Li, H.; Liu, W. Robust factor graph optimisation method for shipborne GNSS/INS integrated navigation system. IET Radar Sonar Navig. 2024, 18, 782–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, Z.; Jin, L.; Wang, H.; Sun, X.; He, Y. A robust factor graph optimization method of GNSS/INS/ODO integrated navigation system for autonomous vehicle. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2024, 36, 016301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Huang, C.; Cheng, J.; Wang, F.; Hu, Y. Refined on-manifold IMU preintegration theory for factor graph optimization based on equivalent rotation vector. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 5200–5219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indelman, V.; Williams, S.; Kaess, M.; Dellaert, F. Information fusion in navigation systems via factor graph based incremental smoothing. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2013, 61, 721–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Dong, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, B.; Li, M. TSF-GINS: Based on time-fixed sliding window with factor graph a global navigation satellite system and inertial measurement unit tightly coupled localization system. Measurement 2025, 239, 115421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Miao, L.; Shao, H. Adaptive two-stage Kalman filter for SINS/odometer integrated navigation systems. J. Navig. 2017, 70, 242–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boguspayev, N.; Akhmedov, D.; Raskaliyev, A.; Kim, A.; Sukhenko, A. A Comprehensive Review of GNSS/INS Integration Techniques for Land and Air Vehicle Applications. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 4819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocal, M.F.; Durmaz, M.; Tunali, E.; Yildiz, H. Assessment of Smartphone GNSS Measurement sin Tightly Coupled Visual Inertial Navigation. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Gao, Y.; Guan, L. Optimizing AUV Navigation Using Factor Graphs with Side-Scan Sonar Integration. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Guan, L.; Zeng, J.; Gao, Y. Autonomous Underwater Vehicle Navigation Enhancement by Optimized Side-Scan Sonar Registration and Improved Post-Processing Model Based on Factor Graph Optimization. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Yao, S. An Adaptive Fast Incremental Smoothing Approach to INS/GPS/VO Factor Graph Inference. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 5691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wu, S.; Tang, C.; Lin, H. UUV Cluster Distributed Navigation Fusion Positioning Method with Information Geometry. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Liu, Y.; Yan, T.; Yang, S.; Li, R. A Robust INS/USBL/DVL Integrated Navigation Algorithm Using Graph Optimization. Sensors 2023, 23, 916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben, Y.; Sun, Y.; Li, Q.; Huang, H.; Gong, S. Multi-AUV Cooperative Navigation Algorithm Based on Factor Graph With Stretching Nodes’ Strategy. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 1008715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Wang, X.; Wang, G.; Hu, M.; Bian, Y.; Qin, X.; Ding, R. A novel INS/USBL/DVL integrated navigation scheme against complex underwater environment. Ocean Eng. 2023, 286, 115485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wen, S.; Jiang, Z.; Tian, W.; Qiu, T.Z.; Othman, K.M. A multi sensor fusion with automatic vision–LiDAR calibration based on factor graph joint optimization for SLAM. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 72, 9513809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, C.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhan, X. Gici-lib: A gnss/ins/camera integrated navigation library. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2023, 8, 7970–7977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shurin, A.; Saraev, A.; Yona, M.; Gutnik, Y.; Faber, S.; Etzion, A. The Autonomous Platforms Inertial Dataset. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 10191–10201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.