1. Introduction

With the rapid development of marine exploration and ocean observation technologies, the demand for reliable underwater information exchange has increased significantly. As a result, underwater acoustic communication has become a key enabling technology for a wide range of marine applications, including environmental monitoring, offshore exploration, and maritime security [

1]. However, underwater acoustic channels present severe challenges to reliable communication due to high signal attenuation, limited available bandwidth, and pronounced multipath propagation effects [

2,

3]. These challenges are further exacerbated in high-mobility shallow-water environments, where rapid channel variations and strong environmental dynamics lead to highly complex and time-varying channel characteristics.

The combined influence of multipath propagation and rapid platform motion gives rise to path-dependent Doppler stretch factors, commonly referred to as non-uniform Doppler effects across different propagation paths [

4,

5]. These effects have emerged as a critical bottleneck in shallow-water acoustic communications. Signals propagating along distinct paths experience different nonlinear time-scaling distortions, which result in severe waveform deformation and loss of signal coherence. From a signal processing perspective, such Doppler-induced distortions correspond to nonlinear time warping rather than simple frequency shifts, which fundamentally challenges conventional compensation and synchronization mechanisms [

6]. Such distortions significantly degrade the performance of traditional single-carrier equalization schemes [

7,

8]. Moreover, advanced multicarrier techniques, such as orthogonal frequency-division multiplexing (OFDM), are also severely affected, as non-uniform Doppler destroys subcarrier orthogonality and introduces strong inter-carrier interference, leading to drastic performance degradation [

9,

10]. As a consequence, non-uniform Doppler has become a widely recognized technical challenge that destabilizes communication links. It fundamentally limits the achievable performance of underwater acoustic communication and sensing networks.

Extensive research efforts have been devoted to mitigating intersymbol interference (ISI) and Doppler-induced impairments in high-speed shallow-water acoustic channels [

11]. Linear equalizers (LE) and decision-feedback equalizers (DFE) remain widely applied due to their relatively low computational complexity; however, their reliance on linear time-invariant (LTI) channel assumptions renders them suboptimal in rapidly time-varying environments. Zero-forcing (ZF) and minimum mean-square error (MMSE) equalizers further suffer from severe performance degradation in channels characterized by long delay spreads and strong dispersion, where residual ISI cannot be sufficiently suppressed [

12]. Although decision feedback can partially alleviate ISI, error propagation remains a persistent challenge. More fundamentally, these approaches exhibit an inherent structural mismatch with the nonlinear time-scaling behavior induced by Doppler effects, limiting their effectiveness under non-uniform Doppler conditions. Specifically, conventional equalizers are designed under a linear convolutional channel model, whereas Doppler-induced time scaling introduces non-convolutional and nonlinear distortions that cannot be accurately represented within the traditional LTI or quasi-LTI framework [

13,

14].

Global resampling using a single Doppler scaling factor represents another commonly adopted countermeasure [

15,

16]. However, in high-speed shallow-water channels, path-dependent Doppler variations invalidate the assumption of a uniform scaling factor, resulting in residual frequency offsets that grow with increasing platform velocity and severely degrade system performance [

17]. To overcome these limitations, alternative approaches based on compressed sensing (CS) [

18] and machine learning (ML) [

19,

20] have been explored. While these methods can capture certain nonlinear channel characteristics, they often suffer from excessive computational complexity, limited robustness to environmental variability, and a strong dependence on large and representative training datasets [

21]. Consequently, despite their potential advantages, existing methods generally exhibit poor adaptability and substantial model mismatch in the presence of severe non-uniform Doppler effects [

22].

To address the aforementioned challenges, this paper proposes a novel equalization paradigm for underwater acoustic communications, termed forward reference-sample equalization (FRSE). Unlike conventional inverse-compensation-based approaches, FRSE adopts a forward-modeling strategy that explicitly emulates the physical propagation behavior of acoustic waves. Instead of attempting to invert the estimated channel response, FRSE constructs structured reference samples by explicitly incorporating multipath delays and Doppler-induced time-scaling effects. These reference samples are then employed as detection templates under a least-squares (LS) criterion, enabling reliable symbol recovery while avoiding the numerical instability and structural model mismatch inherent in conventional equalizers. Owing to its physically consistent modeling framework, FRSE is particularly well suited for high-speed shallow-water environments and dynamic underwater sensing networks, where robust and stable communication links are essential.

The main contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

We propose FRSE, a forward-modeling-based equalization paradigm that directly addresses the nonlinear distortions induced by non-uniform Doppler effects. By constructing reference samples that jointly capture multipath propagation and Doppler time-scaling characteristics, FRSE establishes a physically consistent detection framework that significantly enhances system robustness in high-mobility shallow-water channels.

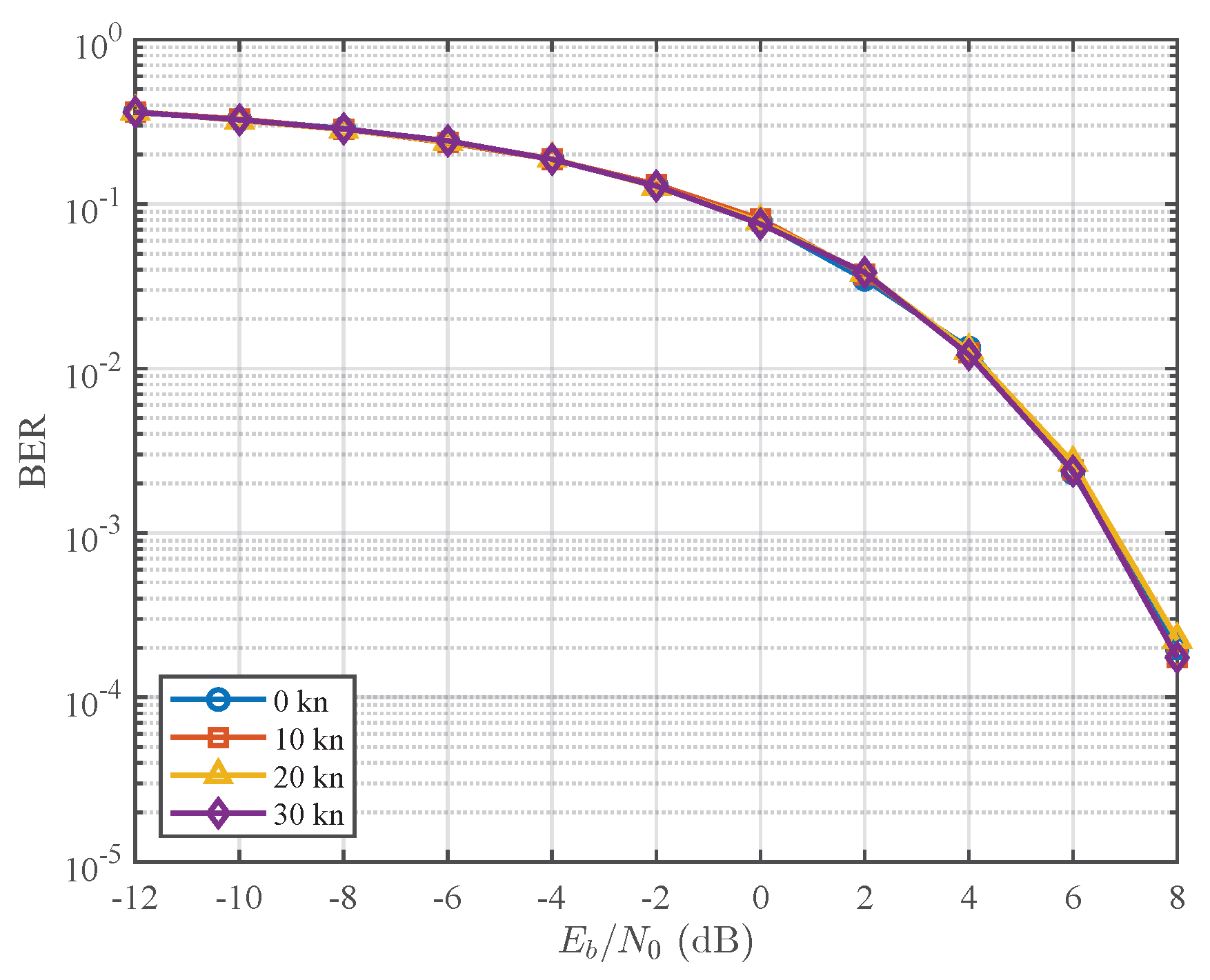

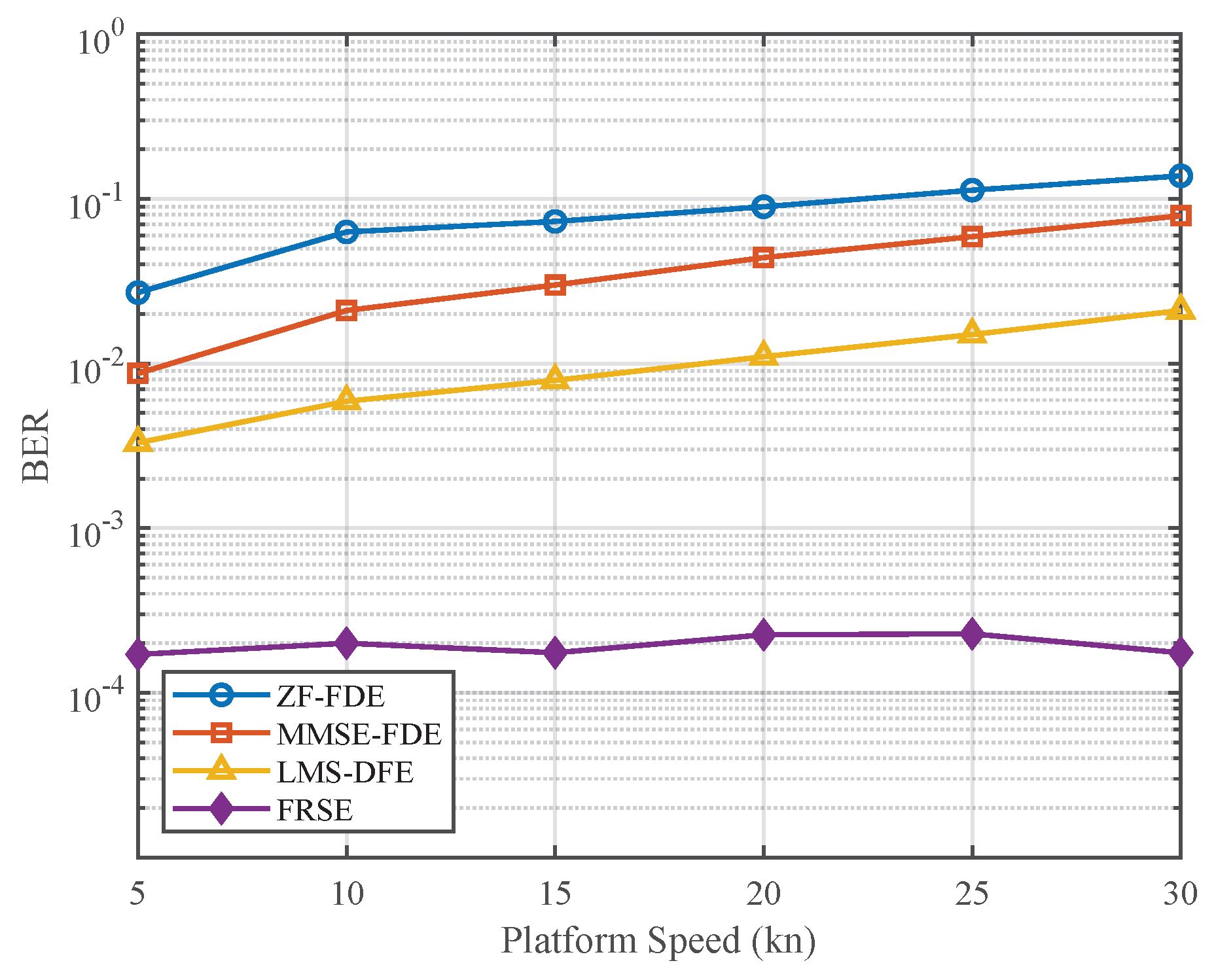

Extensive simulation results demonstrate that FRSE substantially outperforms conventional equalization techniques. In particular, at platform speeds of up to 30 kn and signal-to-noise ratios (SNR) as low as 8 dB, FRSE maintains stable symbol detection and reliable data throughput, whereas conventional methods experience severe performance degradation. These results indicate the suitability of FRSE for real-time data acquisition from mobile platforms, such as autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) and drifting sensor nodes.

The effectiveness of FRSE is further validated using experimental data collected from a shallow-water sea trial. The results confirm its strong capability to mitigate both Doppler-induced distortions and multipath interference, thereby ensuring reliable communication performance in realistic and dynamically varying ocean environments. This experimental validation highlights the practical applicability of FRSE for large-scale underwater observation and intelligent sensing systems.

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this work represents the first experimental validation of an equalization approach based on forward reference-sample matching in high-speed underwater acoustic channels. By bridging the gap between physically grounded modeling and real-world experimental verification, the proposed FRSE framework provides a promising pathway toward reliable and scalable underwater acoustic communication systems.

2. Channel Model

High-speed mobile shallow-water acoustic channels are dominated by multipath propagation and path-dependent non-uniform Doppler effects. When the transmitter and receiver move at a relatively high speed, the signal arriving along each propagation path experiences a distinct delay and Doppler-induced time scaling. These combined effects introduce severe distortions in both the time and frequency domains at the receiver, posing a major challenge to reliable underwater acoustic communication.

The time-varying impulse response (TVIR) of the channel can be expressed as

where

K denotes the number of resolvable propagation paths,

is the complex gain of the

kth path, and

is the corresponding time-varying propagation delay. Here,

denotes the Dirac delta function, which represents an idealized impulse used to model discrete multipath components in the delay domain.

The received signal is modeled as the convolution of the transmitted signal

with the TVIR, plus additive noise:

where

represents ambient noise, which is commonly approximated as additive white Gaussian noise (AWGN). Substituting (

1) into (

2) yields

For high-speed mobile channels, a short-time quasi-static approximation is typically adopted. Specifically, within a sufficiently short observation window (e.g., on the order of one or several symbol durations), the channel parameters can be regarded as approximately constant, while evolving smoothly across consecutive windows. Under this approximation, the path gain satisfies

, and the delay can be approximated by a first-order Taylor expansion (with

):

where

is the nominal delay of the

kth path,

is its Doppler scaling factor,

is the corresponding radial relative velocity, and

denotes the sound speed in water. Since the velocities

generally differ across propagation paths, the scaling factors

are path dependent, which gives rise to the non-uniform Doppler effect.

Substituting (

4) into (

3) yields the received-signal model under non-uniform Doppler:

Equation (

6) explicitly characterizes the distortion mechanism: each path scales the signal time axis by a factor of

and shifts it by

. This model departs fundamentally from the conventional linear time-invariant (LTI) assumption, thereby motivating equalization strategies that account for path-dependent time scaling. It also provides the theoretical basis for the proposed forward reference-sample equalization framework developed in the subsequent sections.

3. Proposed FRSE Method

Conventional equalization techniques typically rely on inverting a linear time-invariant (LTI) channel model, which becomes highly problematic in high-mobility shallow-water environments. In such scenarios, the received waveform is subject not only to delay dispersion but also to path-dependent nonlinear time scaling caused by non-uniform Doppler effects. To address these challenges, we propose a forward reference-sample equalization (FRSE) paradigm that explicitly models the forward physical propagation process and avoids channel inversion.

3.1. Channel Parameter Assumption

To isolate and rigorously evaluate the performance of the proposed equalization paradigm, we assume that the channel parameters

are known a priori or have been accurately estimated by a preceding channel acquisition stage. This assumption is commonly adopted to decouple the performance of the equalizer from that of the channel estimator, thereby enabling a focused analysis of the equalization algorithm itself. High-resolution estimation of these parameters in underwater acoustic channels remains an active research topic. In this work, we focus on the equalization/detection stage; in simulations, perfect channel state information (CSI) is assumed, while in the sea-trial study, the required channel parameters are obtained using an iterative cancellation-based estimation method [

23].

In addition, for a frame of duration , the path parameters are assumed quasi-static (i.e., constant within one frame), which is a standard block-processing approximation in high-mobility underwater acoustic communications.

3.2. Mathematical Formulation

Let

denote the transmitted symbol sequence drawn from a modulation alphabet

. Let

represent a unit-energy pulse waveform (e.g., a spread-spectrum chip-shaped symbol), and let

T denote the symbol duration. The baseband transmitted signal is expressed as

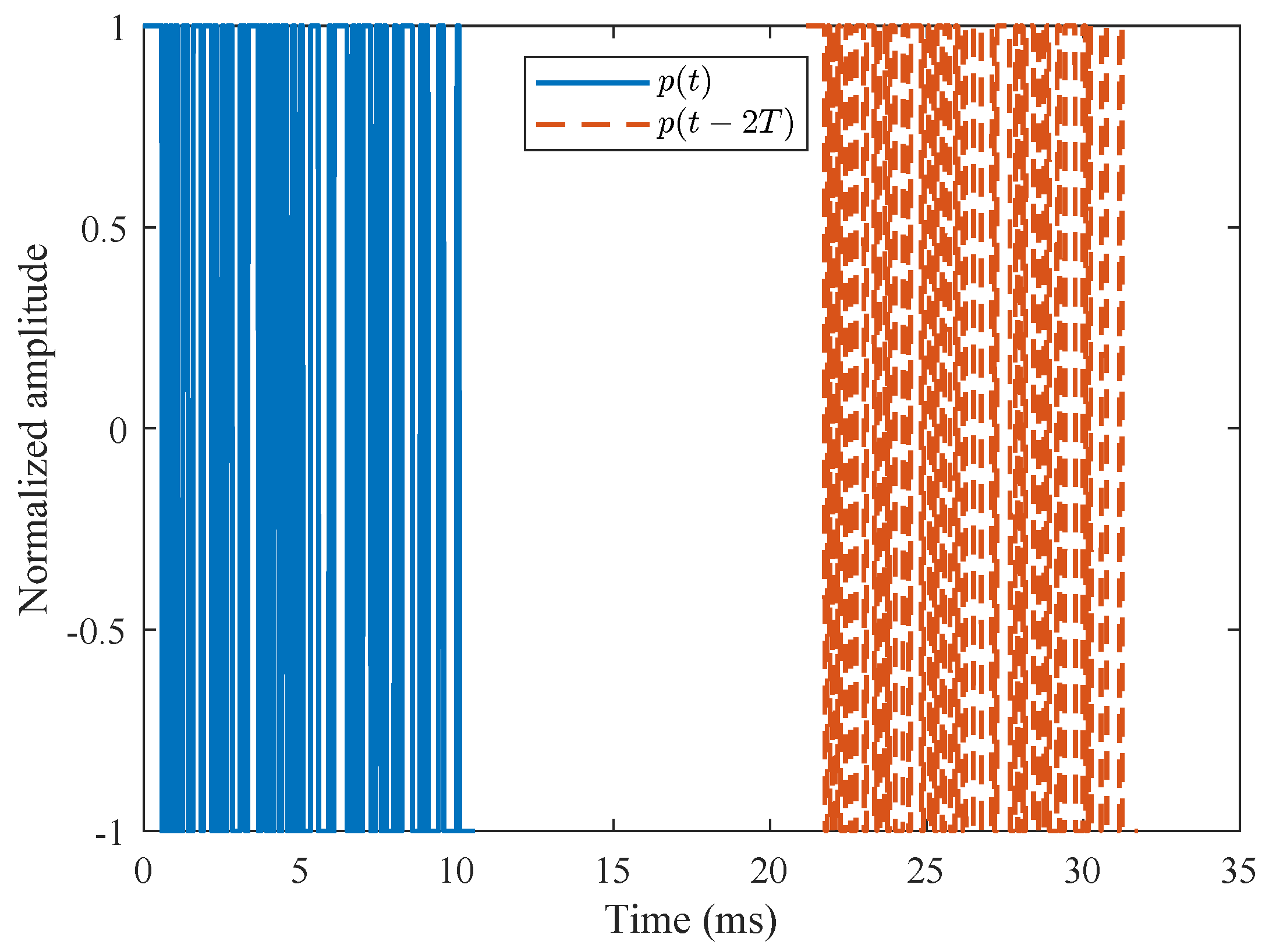

To clarify the time-shifted pulse structure in (

7),

Figure 1 illustrates an example transmit pulse

, where the time displacement associated with the symbol index

i is explicitly shown.

Figure 1 illustrates the time-shifted pulse components

that constitute the basic building blocks of the transmitted signal in (7), while

Figure 2 further shows how these components are transformed by multipath propagation and non-uniform Doppler effects to construct the forward reference samples

.

We define a forward propagation operator

to characterize the path-dependent non-uniform Doppler distortion described in

Section 2. For an arbitrary input waveform

, the corresponding noiseless channel output is modeled as

where

and

denote the complex gain and propagation delay of the

kth path, respectively. Here,

denotes the Doppler time-scaling factor (close to unity), and

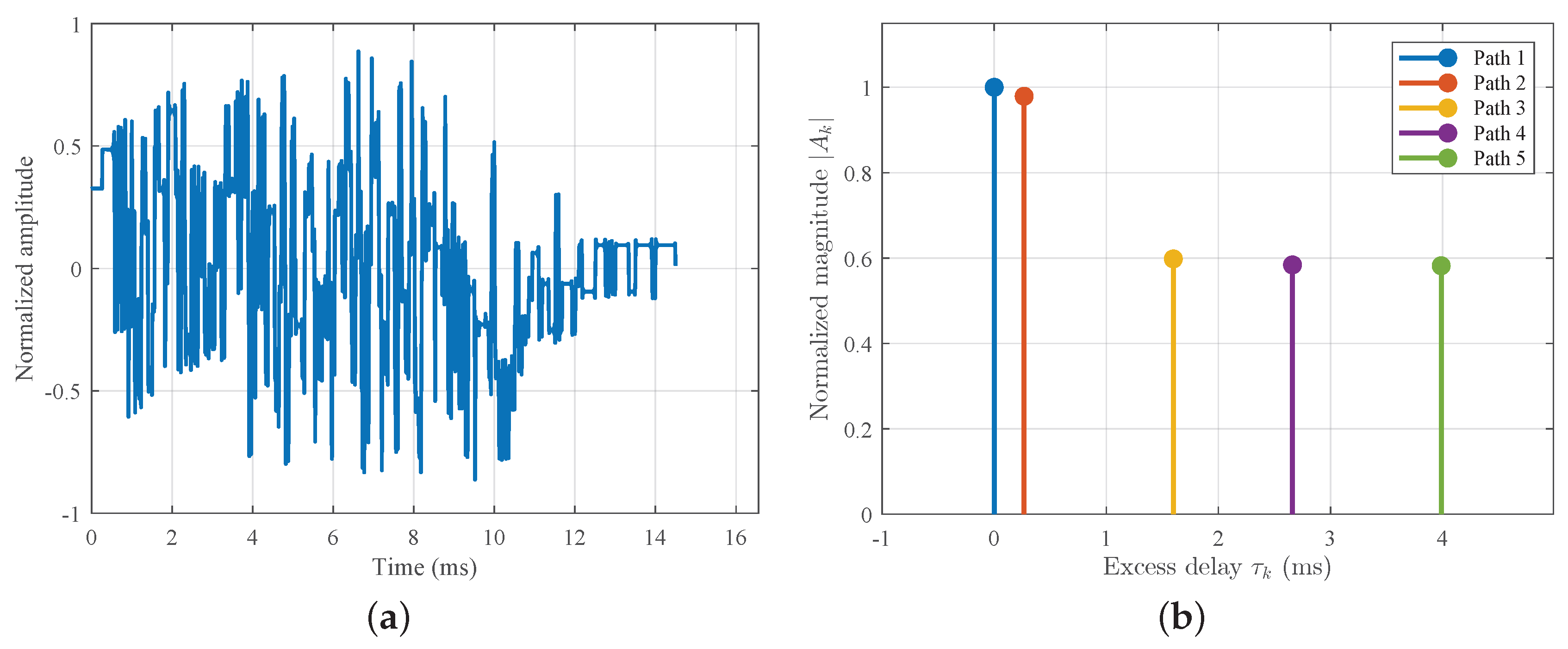

represents its deviation from unity. To provide an intuitive illustration,

Figure 2 depicts the forward reference sample

obtained by coherently superimposing the Doppler-scaled multipath components, together with the underlying delay–magnitude structure

.

Any amplitude scaling induced by time dilation is absorbed into for notational simplicity.

For a candidate symbol

, the corresponding reference waveform generated by transmitting a single symbol is defined as

For frame-based processing, it is convenient to introduce a position-dependent distorted basis function that is independent of the actual symbol value. Specifically, the distorted basis associated with the

ith symbol position is defined as

which depends solely on the symbol position

i and the channel parameters, but not on the transmitted symbol value

. In this sense,

can be interpreted as the forward reference waveform corresponding to a unit-amplitude symbol.

Equation (

10) defines the distorted basis function that serves as the fundamental building block of the FRSE framework. To provide an intuitive illustration,

Figure 2 depicts the construction of forward reference samples under a 20 kn non-uniform Doppler channel, including the original transmitted symbol, the distorted basis

, the coherent superposition of individual multipath components, and the corresponding delay–magnitude structure.

Collecting all distorted basis functions

, the received signal in the presence of additive noise

can be expressed as

The transmitted symbol vector

is estimated by minimizing the least-squares (LS) error in the

sense:

where

. Introducing the inner product

, the corresponding normal equations are given by

Let

denote the Gram matrix with elements

, and let

be defined as

. The LS system can then be written compactly as

Provided that

is nonsingular, the LS estimate satisfies

Finally, each entry of

is projected onto the modulation alphabet via

where

denotes the nearest-neighbor slicing operator.

3.3. Discrete-Time Implementation

For practical digital implementation, the continuous-time signals

and

are uniformly sampled with sampling period

to obtain the received data vector

and the corresponding reference vectors

. Stacking the reference vectors yields the reference matrix

leading to the discrete linear model

In implementation, the path delays can be realized via integer-sample shifts; if higher accuracy is required, fractional-delay interpolation/filtering can be used without changing the FRSE formulation.

Assuming that

has full column rank, the LS estimate is obtained by solving

This can be computed using numerically stable solvers (e.g., QR-based least squares) or iterative methods (e.g., LSQR) when

N is large. Equivalently, the closed-form solution can be written as

3.4. Impact of Multipath Number Mismatch

The proposed FRSE framework relies on the availability of a set of estimated channel parameters, including the number of multipath components. In practice, this number may be imperfectly estimated due to noise or weak-path truncation in the channel estimation stage. We briefly analyze the impact of such mismatch on the FRSE performance.

If the actual channel contains paths while only dominant paths are retained, the unmodeled weak paths act as additional structured interference. Within the FRSE formulation, this residual contribution is absorbed into the noise term , leading to a gradual performance degradation rather than algorithmic failure.

Conversely, if the estimated number of paths exceeds the true number, the additional distorted basis functions typically exhibit very low energy and weak correlation with the received signal. In this case, the resulting Gram matrix remains well-conditioned in practice, and the least-squares solution is only marginally affected. Such behavior is consistent with classical over-parameterized linear inverse problems.

These observations indicate that FRSE is inherently robust to moderate mismatches in the estimated number of multipath components, provided that the dominant propagation paths are correctly captured by the preceding channel estimation stage.

In the present study, the required channel parameters, including the effective number of multipath components, are obtained using a high-resolution iterative cancellation-based estimation method [

23]. This work focuses on the equalization and detection stage, and the channel estimation procedure itself is not further discussed here.

A quantitative evaluation of severe multipath number mismatch would require a joint redesign of the channel estimation stage and is beyond the scope of the present study. Nevertheless, the above analysis provides a physically intuitive explanation of the FRSE behavior under moderate path-number mismatch, which is most relevant in practical systems.

3.5. Computational Complexity Discussion

The computational complexity of the proposed frame-wise FRSE method mainly arises from three primary processing stages:

- 1.

Construction of the reference matrix H. Each column of H is generated by forward-propagating a shifted reference pulse through K resolvable propagation paths and uniformly sampling the resulting waveform. The overall complexity of this stage therefore scales as .

- 2.

Formation of the Gram matrix . Computing the Gram matrix requires operations and dominates the preprocessing cost when direct solvers are employed.

- 3.

Solution of the LS problem. The LS estimate can be obtained either using a direct solver or an iterative solver. When a direct solver such as QR or Cholesky factorization is used, the computational complexity is dominated by the matrix factorization step and scales as , corresponding to the FRSE (Direct) configuration. Alternatively, iterative solvers such as LSQR can be employed to directly solve without explicitly forming the Gram matrix. In this case, the computational complexity scales approximately as , where I denotes the number of iterations, corresponding to the FRSE (Iterative) configuration.

For clarity, the computational complexity characteristics of FRSE under different solver configurations, together with those of a conventional DFE, are summarized in

Table 1.

In comparison, conventional decision-feedback equalizers (DFE) operate on a symbol-by-symbol basis with linear complexity , where L denotes the number of feedforward and feedback taps. While FRSE entails a higher computational burden due to frame-level joint processing, it achieves significantly improved performance by effectively mitigating severe path-dependent non-uniform Doppler distortions that challenge traditional equalization methods.

It is worth noting that the complexity corresponds to a direct solution of the LS problem using matrix factorization rather than explicit matrix inversion. In practical implementations, numerically stable solvers such as QR decomposition are preferred. For tall matrices with , the dominant cost is associated with the QR factorization of , which scales as , thereby reducing both computational burden and numerical sensitivity.

From a trade-off perspective, the computational characteristics of FRSE differ fundamentally from those of compressed sensing (CS)- and machine learning (ML)-based approaches. CS-based methods typically rely on iterative sparse recovery algorithms whose runtime and convergence behavior depend strongly on signal dimension, sparsity level, and iteration count, leading to high and often unpredictable computational cost. In contrast, FRSE involves a fixed and deterministic sequence of operations per frame, resulting in predictable runtime and memory requirements.

ML-based approaches, while offering fast inference once trained, generally incur substantial offline training cost and require large representative datasets to ensure robustness across varying channel conditions. Moreover, their inference complexity depends on network architecture and parameter size, which may pose challenges for resource-constrained underwater platforms. Compared with CS- and ML-based solutions, FRSE achieves a favorable balance between computational predictability, implementation complexity, and robustness without relying on data-driven training procedures.

3.6. Summary

In summary, FRSE constructs a forward reference sample for each symbol position that faithfully captures the combined effects of path-dependent non-uniform Doppler time scaling and multipath propagation under the current channel conditions. These reference samples are aggregated into a frame-level set of distorted basis functions, and demodulation is performed via least-squares matching. By adopting this forward-modeling philosophy, FRSE alleviates the model mismatch and numerical instability commonly encountered in conventional inversion-based equalizers. The overall FRSE procedure is summarized in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1 Forward Reference-Sample Equalization |

Require: Received signal vector ;

Channel parameters ;

Baseband pulse ; Number of symbols N; Symbol period T; Sampling rate . |

| Ensure: Estimated symbol vector . |

| 1: Initialize with zeros. |

| 2: for to do |

| 3: Define shifted pulse: . |

| 4: Generate distorted basis by forward propagation: using (10). |

| 5: Uniformly sample to obtain . |

| 6: Populate the th column of : . |

| 7: end for |

| 8: Solve the LS problem (e.g., QR-based LS or LSQR). |

| 9: return .

|

5. Experimental Validation in a Real Shallow-Water Channel

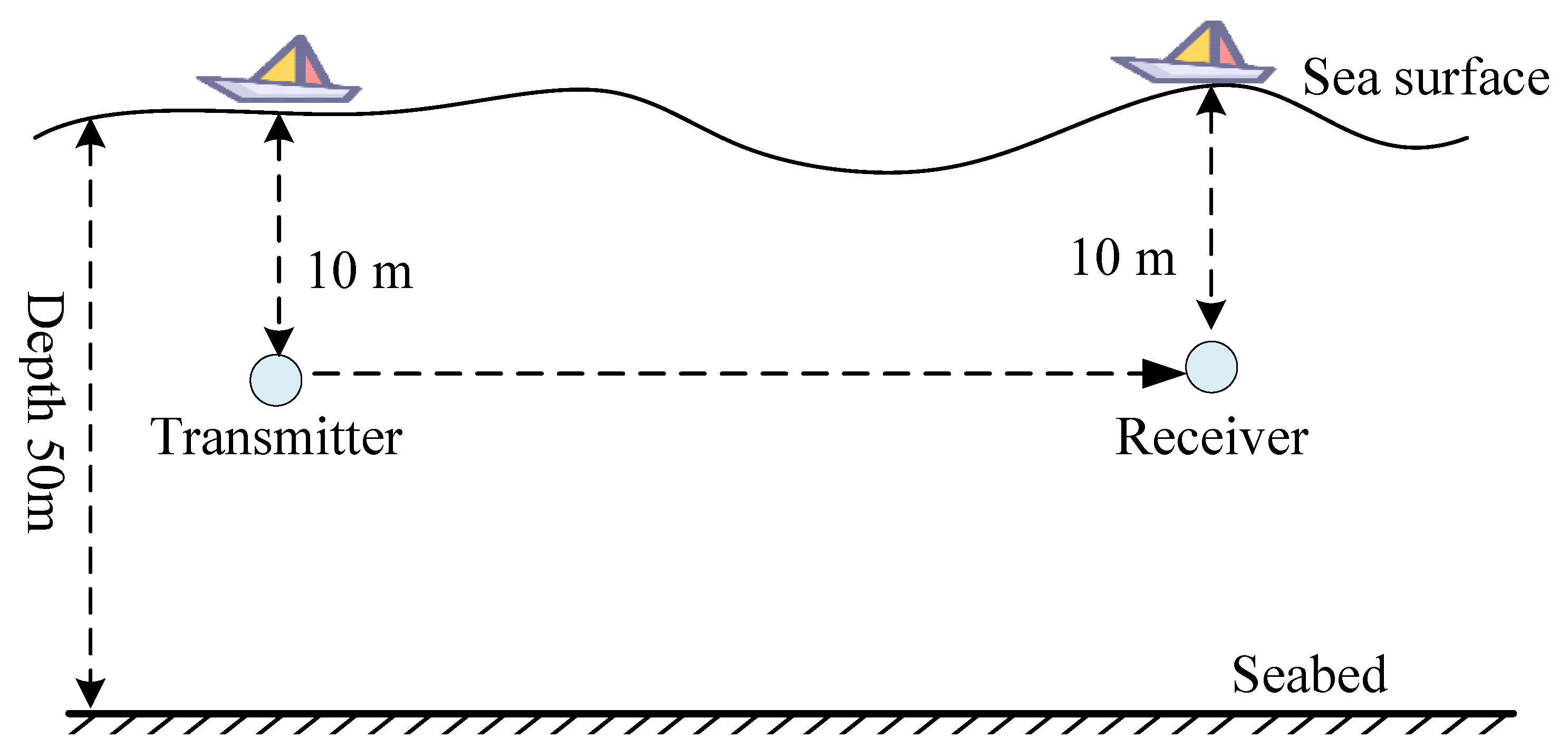

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed FRSE method in a real ocean environment, an underwater acoustic communication experiment was conducted in the Bohai Sea. The sea trial was carried out in a shallow-water area of the Bohai Sea during the autumn season. The average water depth in the experimental region was approximately 50 m, and the representative horizontal separation between the transmitter and receiver was approximately 4.5 km. During the experiment, the water temperature was around 14.5 °C, and the ambient ocean noise level in the signal band was on the order of 98 dB re 1 μPa. Overall, the experimental site exhibited relatively stable shallow-water conditions with weak temporal variability during the measurement period, which are representative of typical coastal acoustic communication environments.

Figure 9 illustrates the experimental geometry of the shallow-water sea trial, including the relative deployment configuration of the underwater acoustic transmitter and receiver.

The transmitted signal employed a direct-sequence spread-spectrum (DSSS) architecture with differential binary phase-shift keying (DBPSK) modulation. The spreading sequence was a band-limited pseudo-random signal occupying the 8–16 kHz frequency band. The total signal duration was 0.338 s, and the sampling rate was set to 96 kHz. The selection of these key parameters was guided by practical considerations of shallow-water acoustic propagation and system constraints. The 8–16 kHz frequency band was chosen to avoid strong low-frequency ambient ocean noise, which is typically dominant below a few kilohertz, while also mitigating excessive high-frequency absorption losses. In addition, this frequency range matches the efficient operating band of the employed underwater acoustic transducer.

The sampling rate of 96 kHz was selected to provide sufficient oversampling relative to the signal bandwidth, enabling improved time and frequency resolution. This is particularly important for accurately capturing Doppler-induced time scaling and frequency shifts in shallow-water scenarios with relative motion.

The total signal duration of 0.338 s is not an arbitrarily chosen parameter, but is determined by the fixed information payload and signal structure of the acoustic beacon. Specifically, the beacon carries a predefined amount of information bits, which are processed through channel coding, differential encoding, and direct-sequence spread-spectrum expansion. Given the fixed spreading factor and chip rate, the total number of transmitted samples is uniquely determined. With a sampling rate of 96 kHz, the resulting signal duration is therefore s. This duration ensures that the complete information packet is transmitted within a single frame while maintaining compatibility with the beacon hardware and signal processing chain.

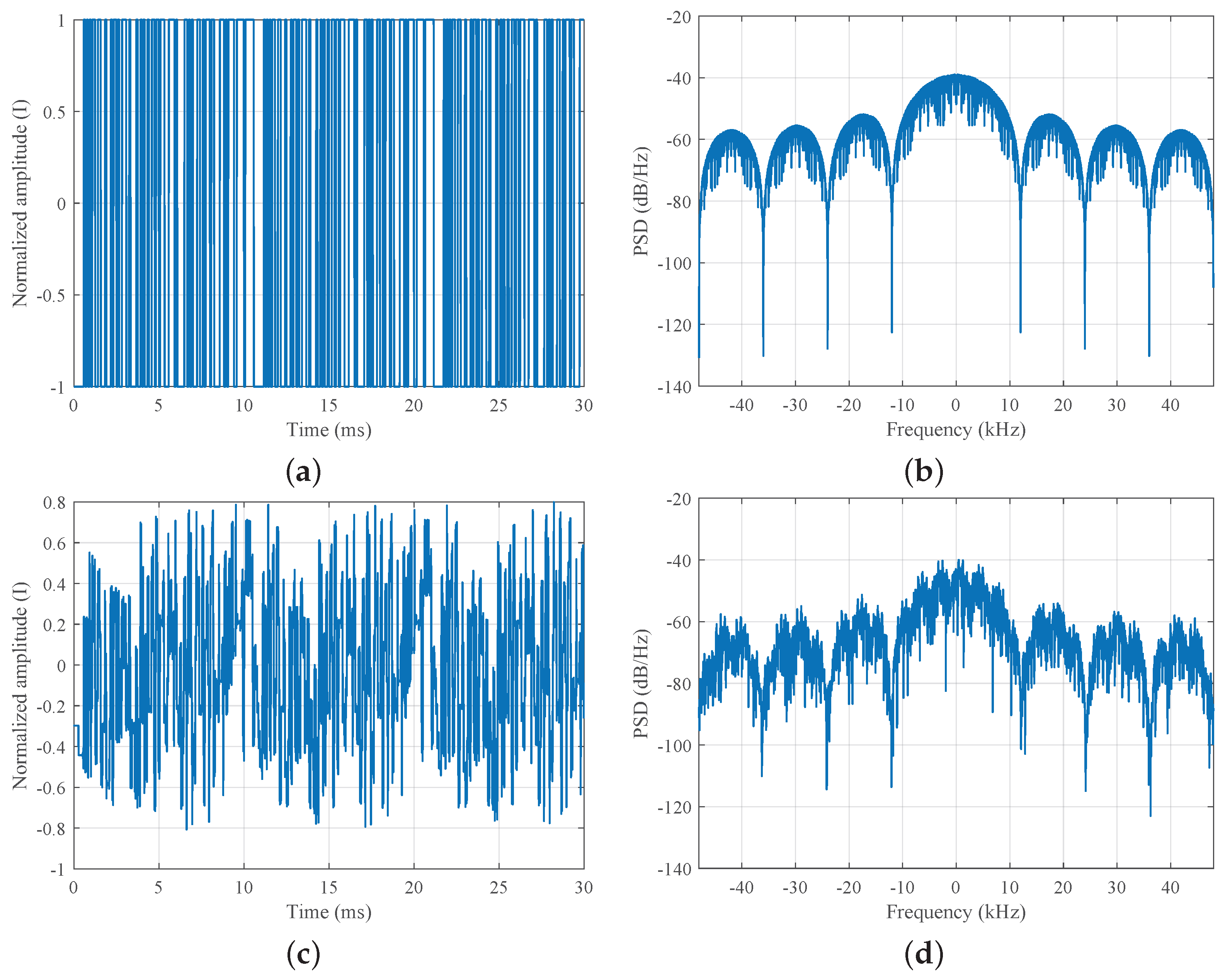

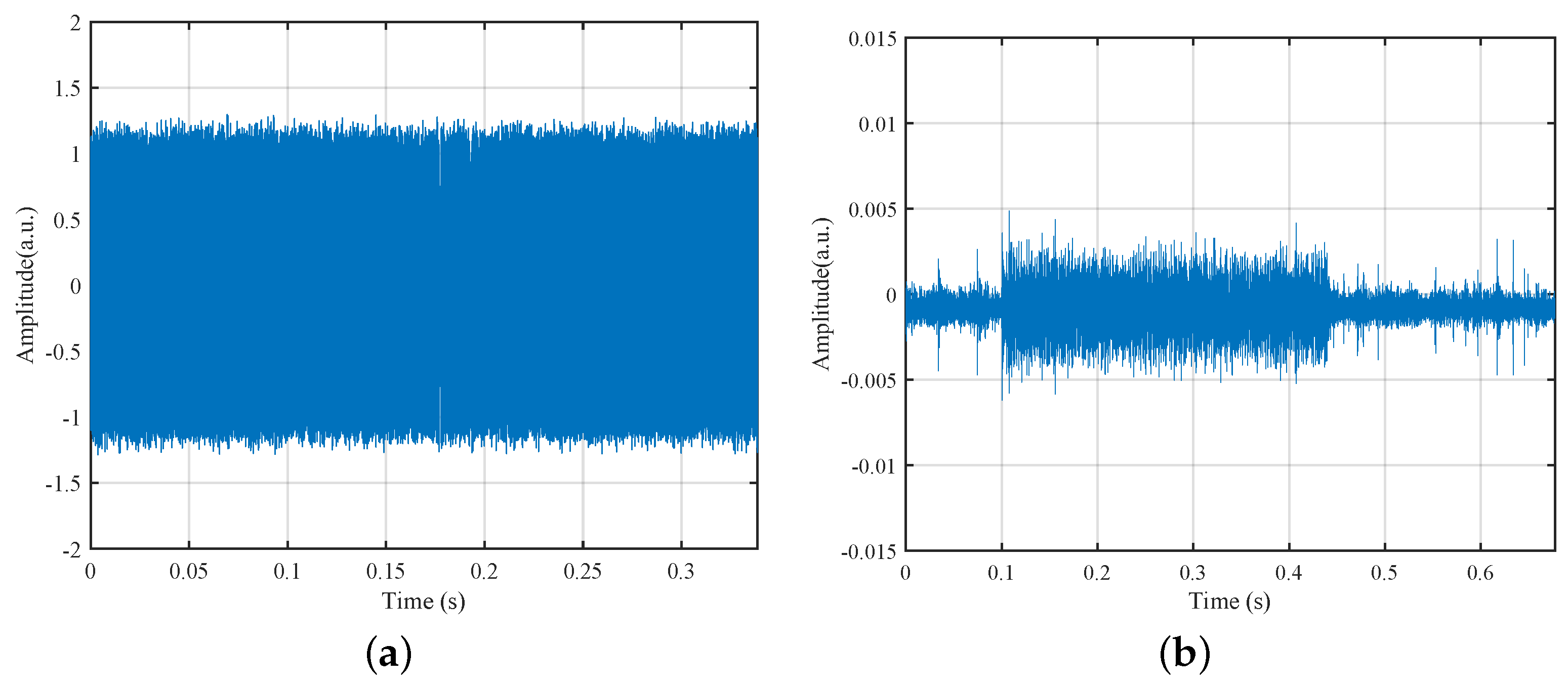

Figure 10a shows the transmitted time-domain waveform, which has a pulse duration of approximately 0.34 s and exhibits a nearly constant envelope, indicating a well-designed transmission signal. After propagation through the shallow-water channel, the received signal shown in

Figure 10b is severely distorted. The signal amplitude is attenuated and fluctuates rapidly, and due to rich multipath propagation, the signal energy is spread over time, resulting in a pronounced multipath tail over the observation interval (about 0.5 s). This behavior is a typical characteristic of shallow-water acoustic channels and provides a challenging yet representative real-world scenario for validating the performance of the proposed FRSE algorithm.

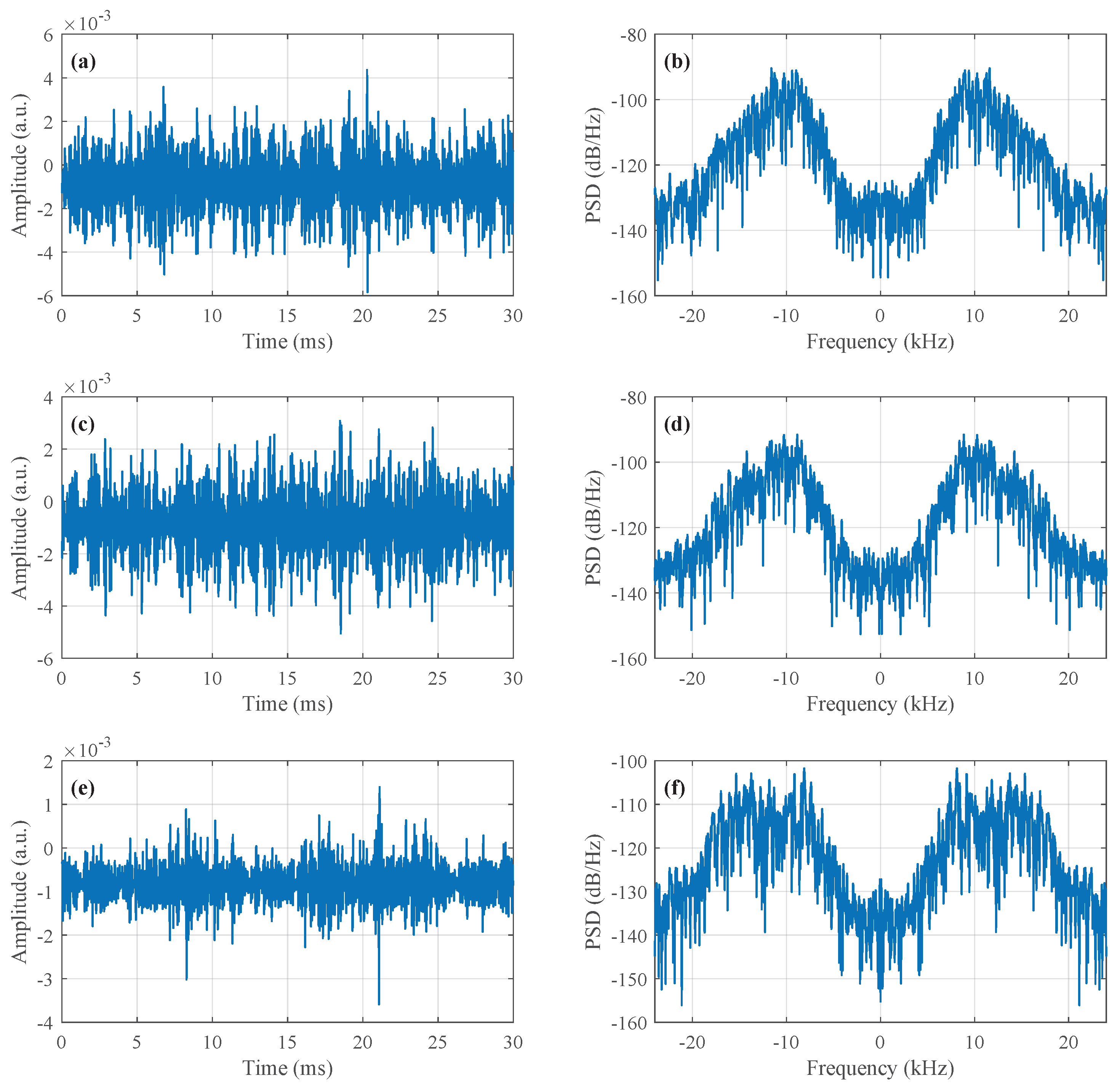

Although

Figure 10 provides an overview of the transmitted and received waveforms over the entire observation interval, such long-duration time-domain signals appear noise-like due to the spread-spectrum modulation and rich multipath propagation. To provide a more intuitive understanding of the signal characteristics, we further examine multiple short-time segments of the received signal and analyze their corresponding frequency-domain representations.

The results in

Figure 11 demonstrate that, despite strong temporal fluctuations caused by multipath propagation, the received signal consistently preserves a stable band-limited spectral structure across different time segments, with the dominant signal energy remaining concentrated in the designed 8–16 kHz band.

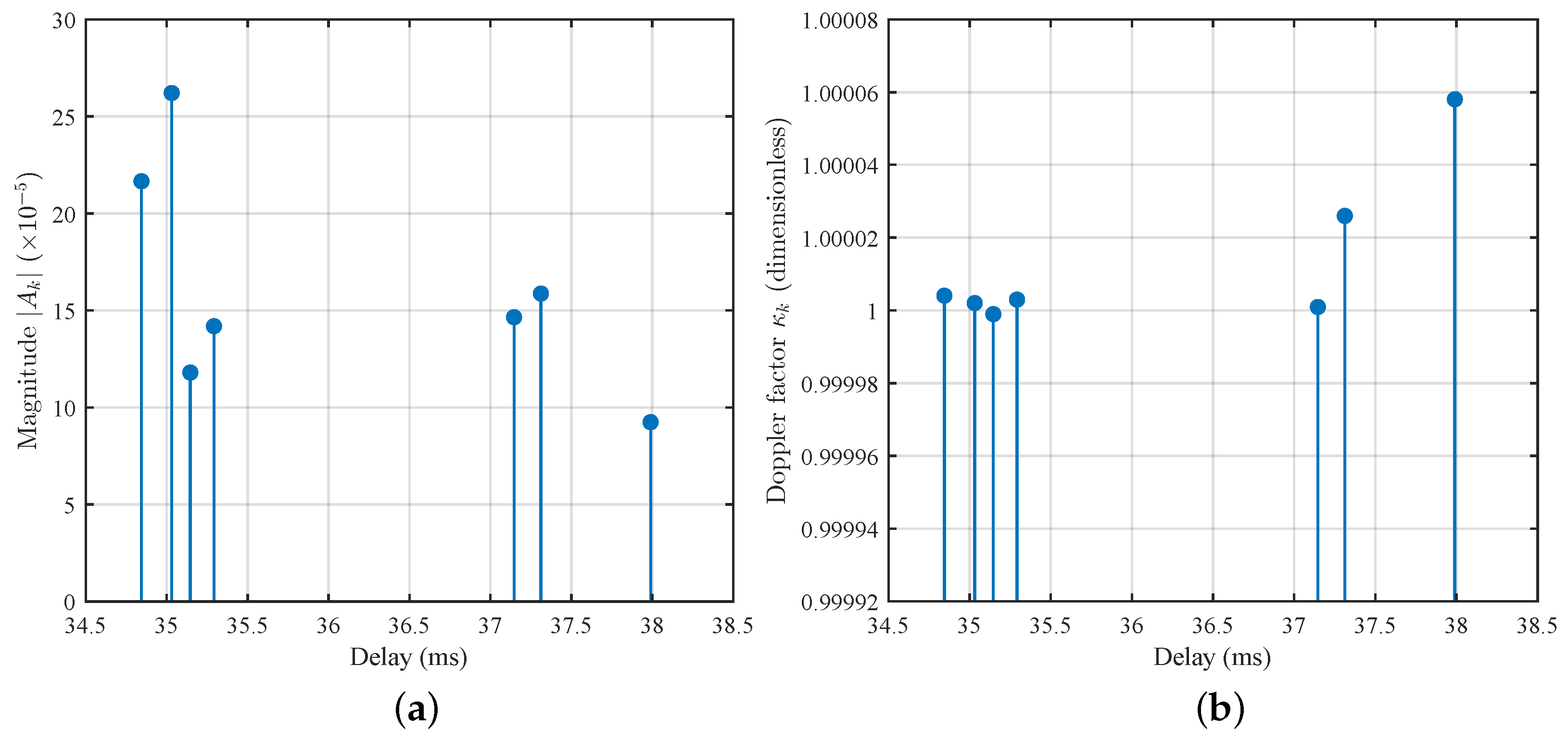

To further evaluate the applicability of the proposed method under realistic shallow-water acoustic communication conditions, channel parameters were extracted from the measured sea-trial data. The estimated parameters are summarized in

Table 5. The channel contains seven resolvable multipath components with an excess delay spread of approximately 38 ms, indicating significant multipath propagation. Although all Doppler scaling factors are close to unity, slight variations ranging from 0.99999 to 1.00006 are observed across different paths, reflecting a typical non-uniform Doppler structure. Moreover, the path amplitudes differ substantially, with the dominant path exhibiting the highest energy and subsequent paths decaying progressively. Applying the FRSE method to this measured channel verifies its equalization and decoding performance under realistic non-uniform Doppler conditions.

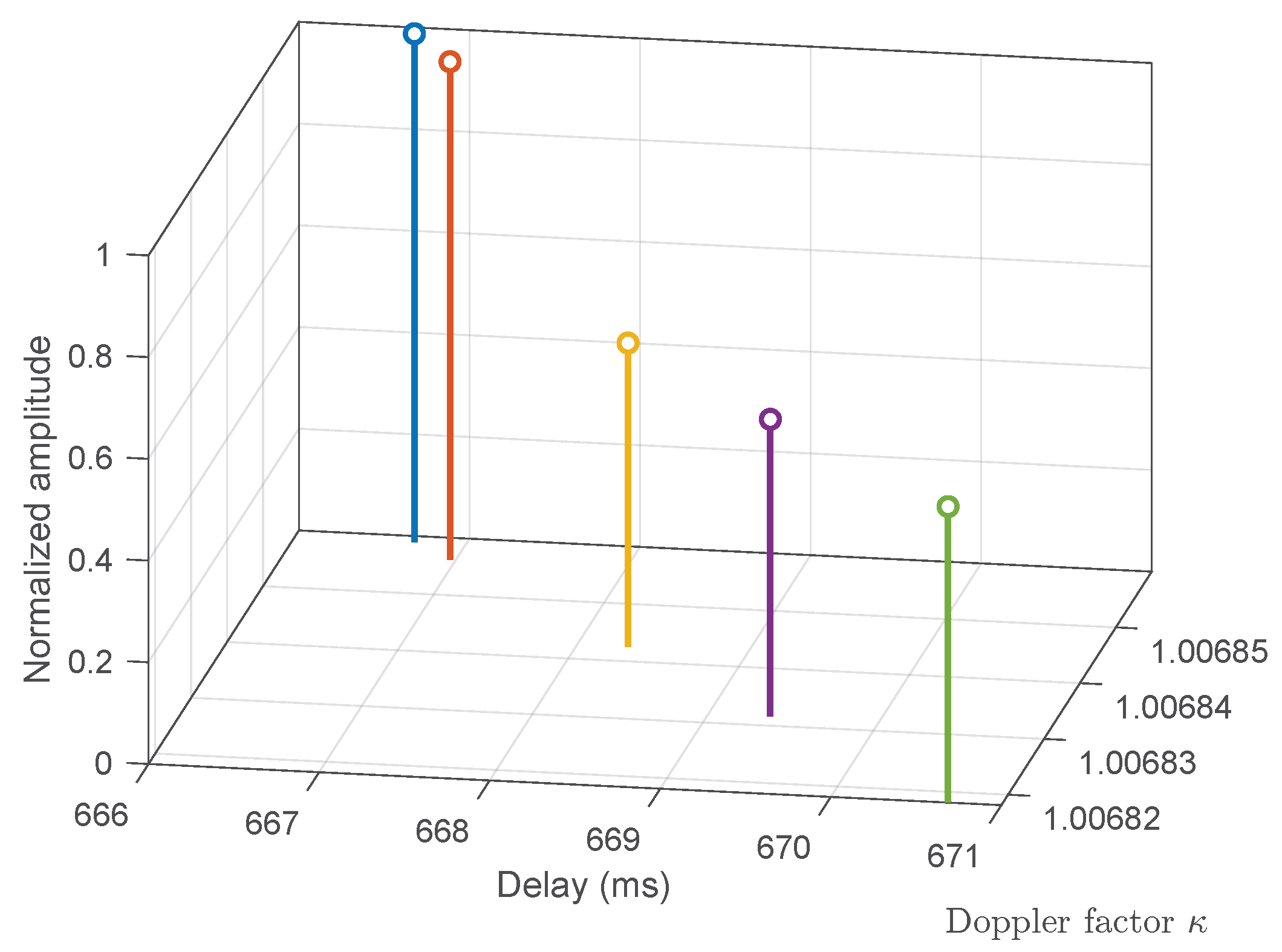

For a clearer visualization,

Figure 12 illustrates the reconstructed delay–amplitude and delay–Doppler distributions of the measured sea-trial channel corresponding to the parameters listed in

Table 5. The joint distributions further highlight the coexistence of dense multipath propagation and slight but path-dependent Doppler variations, which are characteristic of shallow-water mobile acoustic channels.

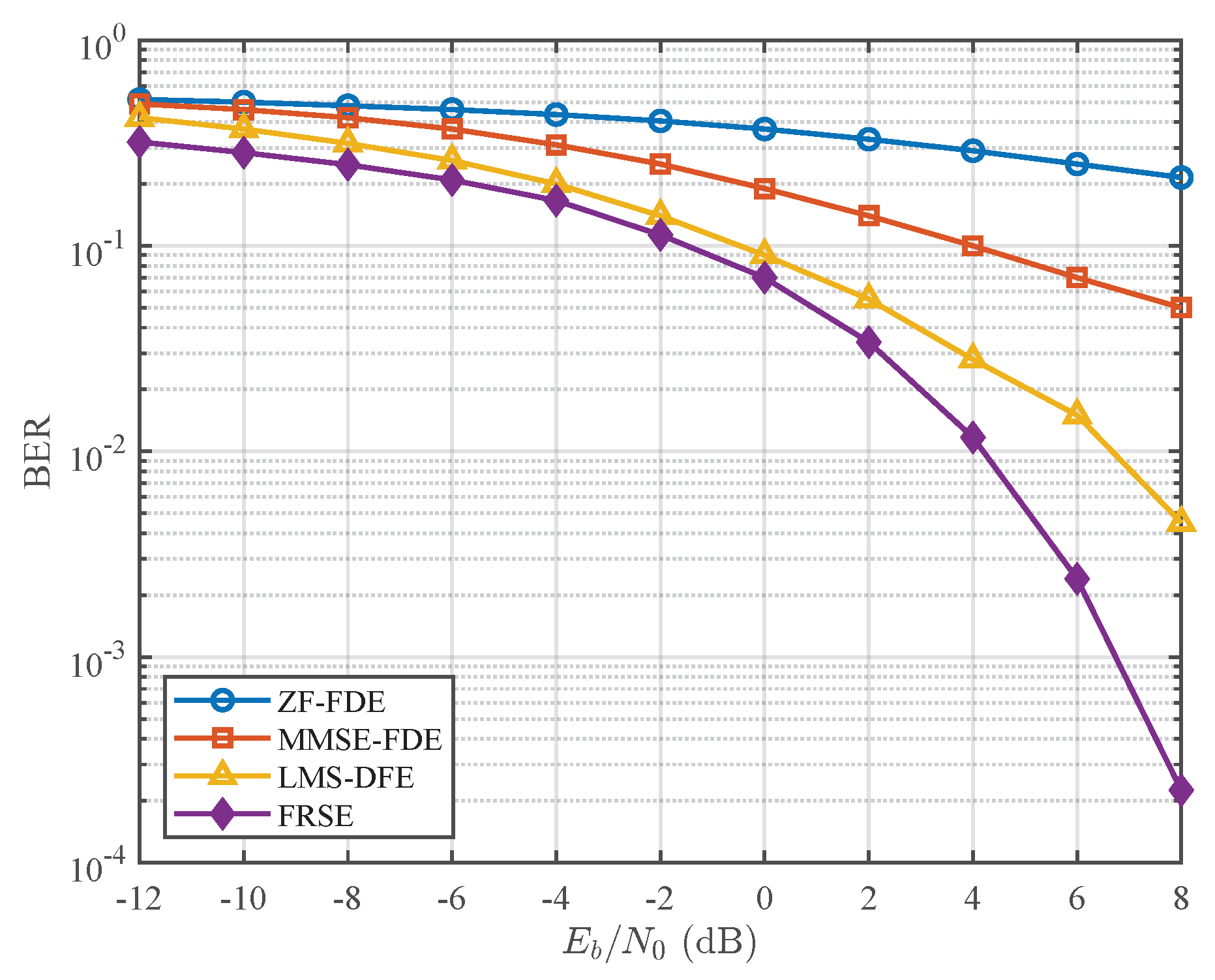

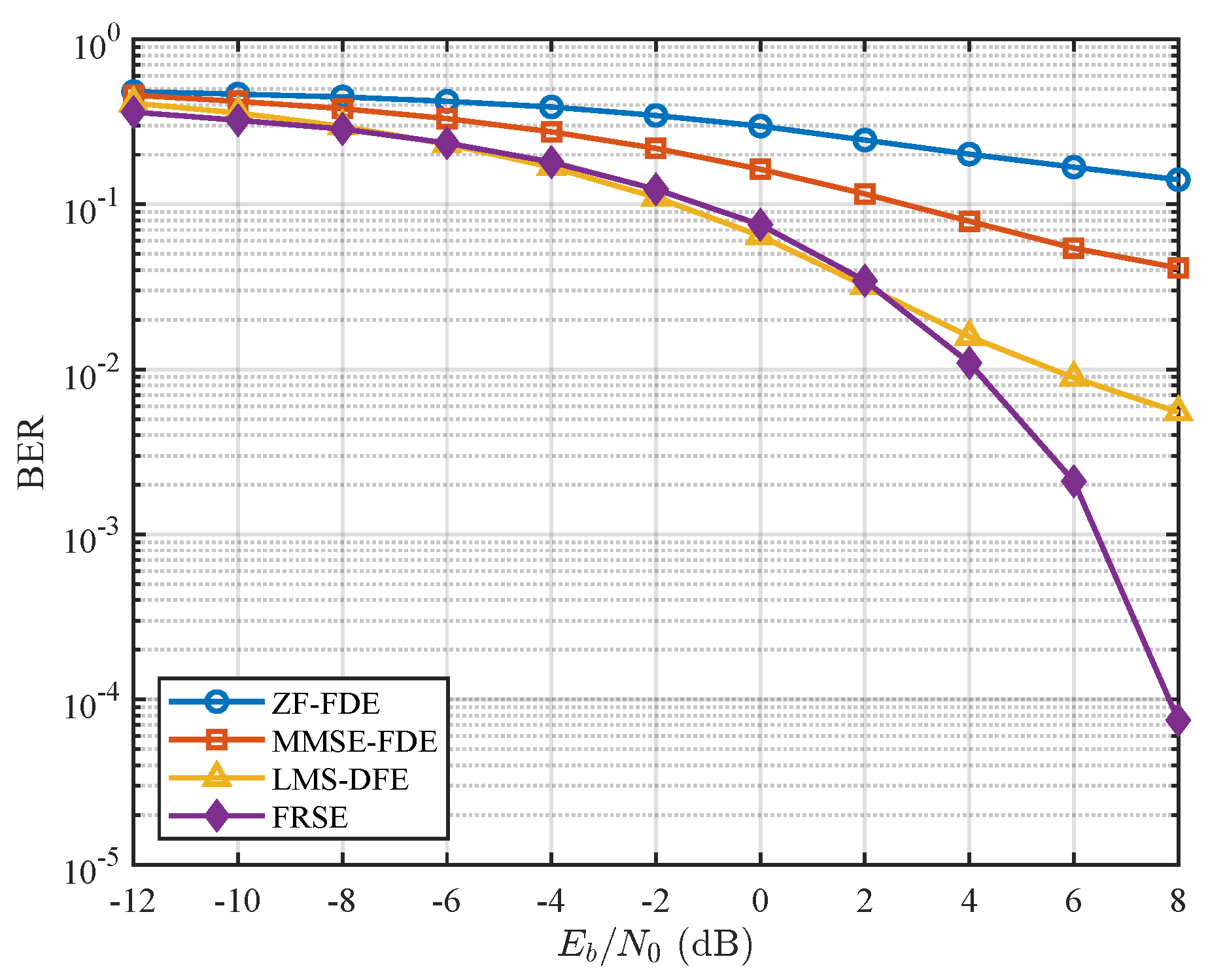

Figure 13 compares the BER performance of different equalization methods under the measured channel conditions. Conventional LTI-based equalizers struggle to compensate for the combined effects of dense multipath propagation and even mild non-uniform Doppler, resulting in a pronounced BER floor at medium-to-high

. In contrast, the proposed FRSE method leverages forward physical modeling to accurately capture channel time variation, and its BER continues to decrease without exhibiting an error floor. At

dB, FRSE achieves a BER nearly two orders of magnitude lower than the best-performing conventional method, highlighting its robustness and practical deployment potential.

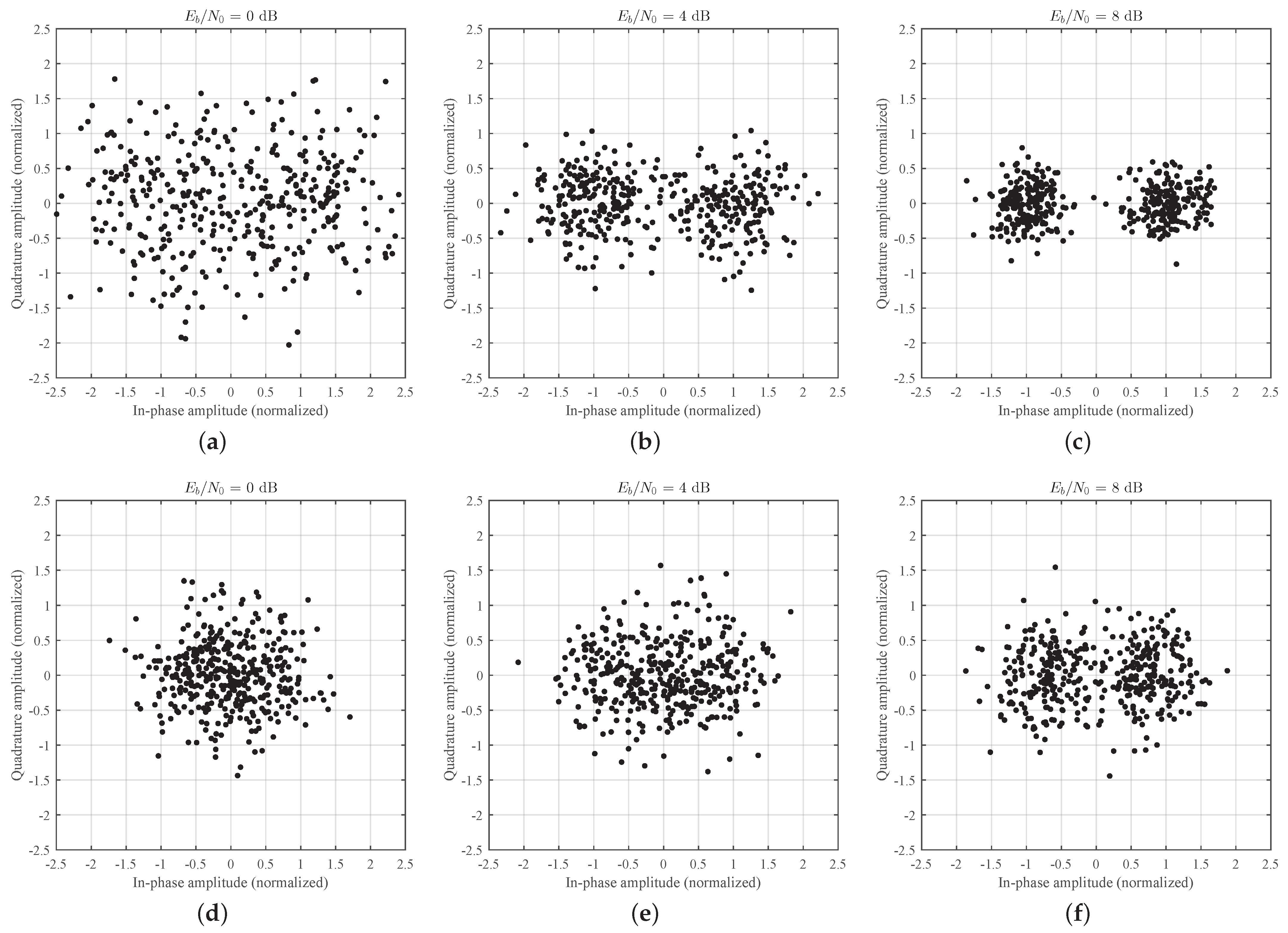

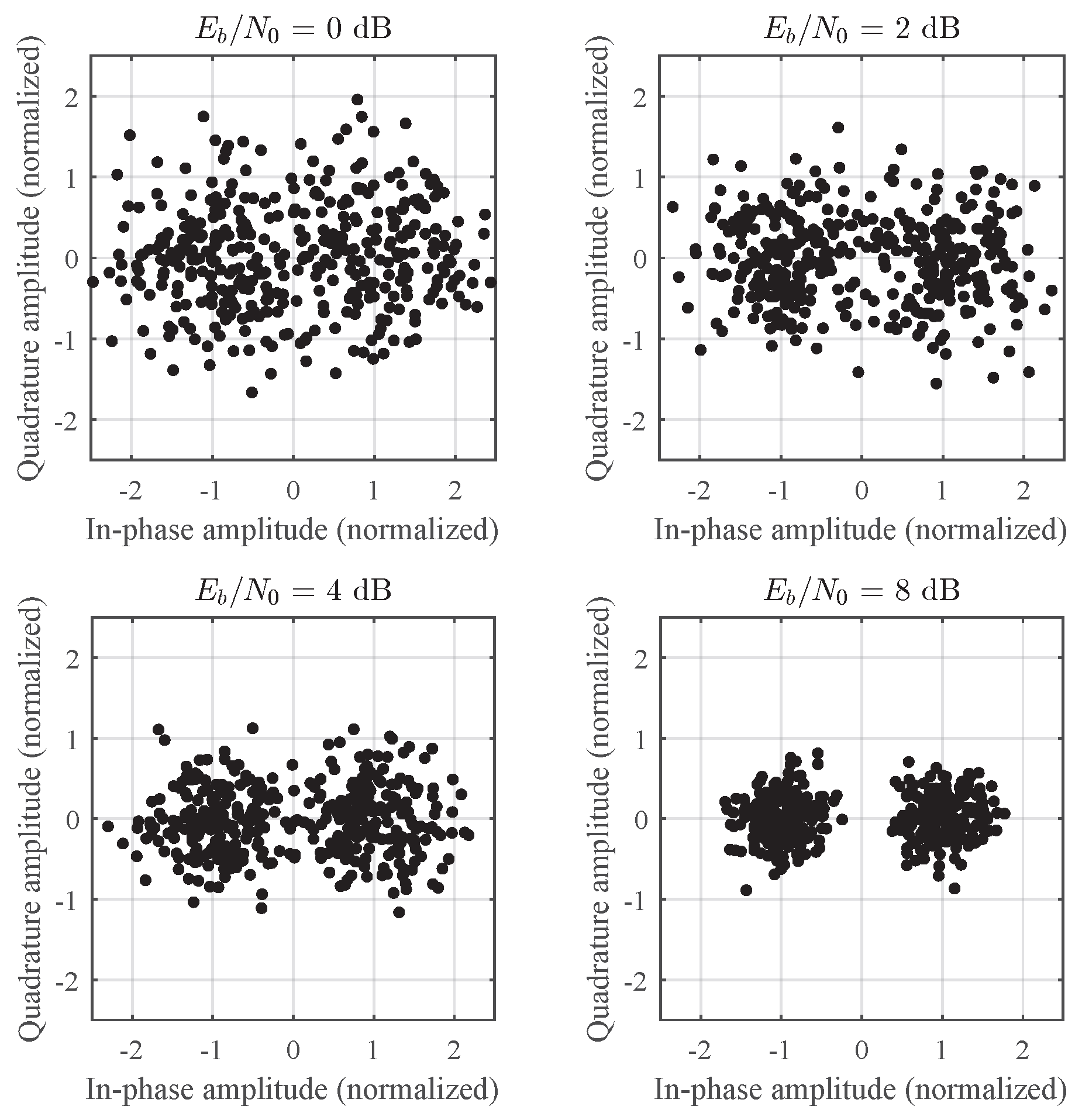

To further visualize the equalization performance,

Figure 14 presents the post-equalization constellation diagrams of FRSE at different

levels. At

dB, the constellation points are widely scattered and symbol clusters are indistinct. As the SNR increases to 2 and 4 dB, two clusters gradually emerge and become increasingly distinguishable. At

dB, the points are tightly concentrated around the

positions on the real axis, forming well-defined clusters and demonstrating strong demodulation capability under the measured sea-trial channel.

6. Conclusions

This paper addressed the fundamental challenges of high-speed shallow-water acoustic communication arising from the combined effects of severe multipath propagation and non-uniform Doppler distortion. To overcome these limitations, a forward reference-sample equalization (FRSE) method was proposed and systematically validated. Departing from conventional channel-inversion-based equalizers, FRSE adopts a forward physical modeling strategy that explicitly captures the propagation-induced distortions of each multipath component. By constructing a reference matrix consistent with the underlying channel physics, the inherently nonlinear equalization problem is transformed into a physically grounded linear least-squares detection framework.

Comprehensive simulation results and real sea-trial experiments demonstrate the effectiveness and robustness of the proposed method. In high-speed mobile scenarios, referring to shallow-water acoustic communication conditions involving relative transmitter–receiver motion with platform velocities of up to 30 kn (approximately 15.4 m/s), FRSE exhibits strong resilience to speed variations and consistently outperforms traditional linear equalization techniques, achieving significantly lower bit error rates without exhibiting an error floor.

In conclusion, the proposed FRSE method provides an effective solution to a key technical bottleneck in high-speed mobile underwater acoustic communications. Its strong adaptability to non-uniform Doppler effects, combined with reliable performance under realistic shallow-water conditions, highlights its substantial theoretical significance and promising potential for practical deployment in future underwater sensing and communication systems.