Abstract

This paper studies a novel movable antenna (MA)-aided Cell-Free Massive MIMO system to leverage the corresponding spatial degrees of freedom (DoFs) for improving the performance of distributed wireless networks. We aim to maximize the ergodic sum capacity by jointly optimizing the MA positions and the transmit covariance matrix based on statistical channel state information (CSI). To address the non-convex stochastic optimization problem, we propose a novel Constrained Stochastic Successive Convex Approximation (CSSCA) framework, enhanced with a robust slack-variable mechanism to handle non-convex antenna spacing constraints and ensure iterative feasibility. Numerical results show that the considered MA-enhanced system can significantly improve the ergodic capacity compared to fixed-antenna cell-free systems and that the proposed algorithm exhibits robust convergence behavior.

1. Introduction

Wireless communication networks are rapidly evolving toward the sixth generation (6G). Future networks are anticipated to demand not only high peak data rates but also consistent and reliable quality of service (QoS) across wide geographic areas [1,2]. To achieve this global coverage, emerging paradigms such as Satellite–Terrestrial Integrated Networks are being investigated to optimize computing offloading and resource allocation for the Internet of Remote Things (IoRT) [3]. While Massive Multiple-Input Multiple-Output (MIMO) has served as a cornerstone of 5G by providing significant spectral efficiency gains, its conventional co-located deployment faces inherent physical limitations, leading to cell-edge performance degradation [4,5,6].

To address these structural bottlenecks, Cell-Free Massive MIMO has emerged as a transformative architectural paradigm [7,8]. By distributing a large number of access points (APs) over a wide geographic area and connecting them to a central processing unit (CPU), cell-free systems are designed to mitigate traditional cell boundaries. This “user-centric” transmission strategy allows coherent cooperation among distributed APs to serve users, utilizing macro-diversity to combat shadow fading. Consequently, such an architecture holds the potential to provide uniform signal coverage regardless of user location [9,10]. However, despite the theoretical advantages of Cell-Free Massive MIMO, its practical performance remains constrained by the hardware architecture of the APs.

In conventional implementations, APs are typically equipped with fixed-position antennas (FPAs). Once deployed, the spatial location of each antenna remains static. If an AP is deployed in a deep fading region or suffers from severe local blockage, its channel condition becomes intrinsically poor. In such scenarios, even advanced digital beamforming techniques may struggle to fully compensate for the physical lack of signal energy, potentially leading to inefficient resource utilization and bottlenecks in cooperative network capacity.

Related Work and Motivation

To overcome the physical limitations of fixed-position antennas and fully leverage spatial channel variations, flexible antenna technologies have attracted significant attention, evolving from passive surfaces to active reconfigurable elements. Initially, Reconfigurable Intelligent Surfaces (RISs) were proposed to proactively modify propagation environments [11,12,13]. Recent works have further explored RIS-enabled architectures for enhancing physical layer security and energy efficiency in wireless-powered systems [14]. However, as passive devices, they typically suffer from the “multiplicative path loss” effect and lack active signal processing capabilities, which may constrain performance compared to active transceivers. Subsequently, Fluid Antenna Systems (FASs) introduced the concept of position switching using liquid-based or reconfigurable structures [15,16,17], yet their implementations are often confined to one-dimensional (1D) linear spaces, limiting their ability to fully capture multipath components in complex planar environments. As a more versatile evolution, movable antenna (MA) technology has recently emerged [18,19,20,21], which—unlike passive RIS—connects to active RF chains to avoid double path loss, and distinct from the 1D restrictions of FAS, utilizes electromechanical drivers to enable continuous antenna movement within a flexible two-dimensional (2D) or even three-dimensional (3D) region. This introduces a new degree of freedom, micro-scale position optimization, allowing the system to actively reshape channel realizations to mitigate fading and minimize spatial correlation [22,23,24].

Although flexible antenna technologies have attracted significant attention, their integration into cell-free architectures remains largely unexplored. Existing research in this domain has primarily focused on RIS-aided cell-free systems to enhance coverage [11,25,26]; however, RISs are passive devices constrained by the multiplicative path loss effect. Regarding active flexible antennas, while FASs and MAs have been extensively studied, these works predominantly target centralized MIMO (co-located arrays) or point-to-point scenarios. Specifically, Refs. [16,20] demonstrated the significant spatial diversity gains achievable by FASs and MAs through exploiting channel spatial variations. Furthermore, Ref. [19] extended this to point-to-point MIMO systems, verifying the capacity improvement via joint position and covariance optimization. These studies collectively confirm the potential of MAs in enhancing link-level performance.

However, applying these concepts to cell-free networks introduces distinct challenges compared to the single-link scenarios in [16,19,20]. While previous works primarily focus on maximizing the quality of individual links, cell-free architectures are inherently interference-limited and rely on the cooperation of distributed access points (APs). In this context, the movement of an antenna affects not only the intended signal strength but also the global interference environment experienced by other users. Consequently, the optimization objective must shift from local link enhancement to balancing network-wide performance, requiring an approach to address the coupling between MA positioning and cooperative interference management.

Applying MA to Cell-Free Massive MIMO architectures introduces unique challenges that distinguish our work from the existing literature. As summarized in Table 1, the primary distinction lies in the CSI assumption and its implications for practical feasibility:

Table 1.

Comparison of this work with the recent MA literature [27,28,29], highlighting the novelty in CSI assumption and architecture.

- Timescale Mismatch: The majority of prior MA works (e.g., [27,28,29]) rely on the assumption of perfect instantaneous CSI for position optimization. This implies that antennas must move and transmit within the channel coherence time (milliseconds). This creates a fundamental conflict with practical electromechanical capabilities, as motors typically operate on the order of seconds.

- Distributed Scalability: Most existing works focus on co-located MIMO. Extending instantaneous CSI-based designs to distributed cell-free networks would incur prohibitive synchronization overhead to acquire global CSI and update positions in real time.

To bridge the gap between theoretical potential and engineering feasibility, this paper investigates a robust design strategy based on statistical CSI. Unlike instantaneous CSI, statistical CSI (e.g., angle of departure/arrival and angular spreads) varies much more slowly and remains stable over relatively long periods. Rather than tracking fast-varying instantaneous channels, we aim to determine antenna positions that are statistically optimal for long-term system performance. Under this framework, we focus on jointly optimizing the MA positions and the transmit covariance matrix to maximize the ergodic sum capacity. This strategy effectively determines the optimal “spatial formation” of the distributed APs, ensuring that the network geometry is statistically aligned with the channel’s spatial power distribution.

The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

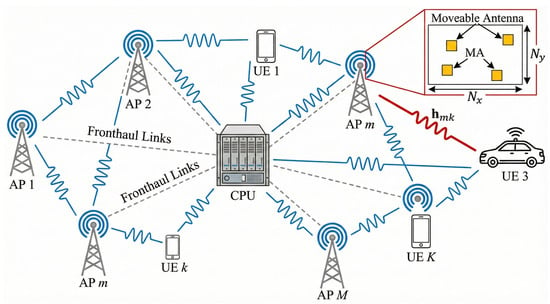

- System Modeling: We propose a novel MA-aided Cell-Free Massive MIMO framework that leverages statistical CSI. A diagram of the model is presented in Figure 1. Unlike previous works that focus on single-cell or instantaneous optimization, we formulate a joint optimization problem for MA positions and the transmit covariance matrix to maximize the ergodic sum capacity, providing a theoretical performance upper bound for distributed antenna systems.

Figure 1. MA-enhanced cell-free system model.

Figure 1. MA-enhanced cell-free system model. - Algorithm Design: The formulated problem is highly non-convex due to the coupling of variables and the expectation operation over random channel states. To tackle this, we use a Constrained Stochastic Successive Convex Approximation (CSSCA) algorithm [30]. A key novelty of our algorithm is the incorporation of a slack-variable mechanism to robustly handle the strict non-convex antenna spacing constraints, preventing infeasibility during the iterative process.

- Performance Analysis: Simulation results demonstrate that the proposed scheme significantly outperforms the conventional fixed-position cell-free system. An in-depth analysis of key system parameters reveals that the proposed algorithm exhibits robust convergence when solving the optimization problem. Furthermore, the results confirm that the proposed model provides substantial performance gains under varying conditions, particularly regarding the impact of (1) the Rician K-factor, (2) the number of antennas per AP, and (3) the size of the AP movement region.

2. System Model and Problem Formulation

We consider an MA-aided Cell-Free Massive MIMO system comprising K conventional single-antenna user equipment (UE) and L access points (APs), each equipped with N MA elements capable of moving within a defined area. APs are arbitrarily distributed across the coverage area and connected to edge cloud processors (CPUs) via any means. This architecture enables coherent joint transceiver operation for end users throughout the coverage area. When both L and K are large numbers, it is termed a Cell-Free Massive MIMO system, typically with L≫K. The system model is shown in Figure 1.

We assume that the APs and UEs operate under a Time Division Duplexing (TDD) protocol, which includes a pilot phase for channel estimation and a data transmission phase. We consider a standard Massive MIMO TDD protocol where each coherent block is divided into channel time slots for uplink pilot transmission, slots for uplink data transmission, and slots for downlink data transmission, resulting in a total duration . We assume that the AP is equipped with N MA elements in a given region . The position of N MA elements can be denoted by , respectively, where represents the position of the n-th MA element in region . Additionally, to avoid mutual coupling between MAs, the minimum spacing between MAs is typically required to be no less than , i.e., , where is the wavelength of the carrier. Furthermore, the channel spanning from the k-th UE to the l-th AP can be represented by , in which we can formulate the n-th MA element of the l-th AP by and denote the spatial spreading by G. In a cell-free system, multiple access points typically serve a single UE; due to the distributed deployment of APs, the channel matrices between different APs and any given UE are statistically independent, and the signal received by the k-th UE can be expressed as

where s denotes the transmitted signal, and represents the beamforming vector, while denotes the additive white Gaussian noise vector at the receiver.

2.1. Channel Model

In the context of a cell-free scenario, the far-field model is employed, where the angles of arrival (AoAs) and angles of departure (DoAs) of antennas belonging to the same UE/AP are considered to be identical. It is worth noting that this assumption holds valid for typical communication distances. Specifically, considering the operating frequency of 30 GHz ( mm) and a typical MA region size of (i.e., 4 cm × 4 cm), the Rayleigh distance determining the far-field boundary is calculated as m, where is the diagonal dimension of the region. In practical cell-free networks, the transmission distance between a user and an AP is typically much larger than this threshold. Consequently, the plane wave approximation is sufficiently accurate locally for each AP, implying that the AoAs/AoDs vary negligibly across the different positions within the small movement region. and denote the elevation and azimuth AoD, respectively, while and represent the elevation and azimuth AoAs. In the downlink, the difference in propagation path between the MA element at position and the origin of the AP region in the direction of the AoD can be expressed as

In our model, all MA elements are located on the same plane, and there is no phase difference in the Z direction. The array steering vector of the MA-enhanced AP can be expressed as

In practice, each UE typically has only one antenna, so phase differences can be ignored. The spatial propagation function G is typically used to represent the gain of propagation paths in different directions, consisting of two components—the LOS component and the NLOS component—expressed as

where and represent the LOS path gain and its corresponding AoD and AoA. In this study, an uncorrelated Rayleigh scattering environment is employed to describe the NLOS components, which consist of a series of independent, zero-mean complex Gaussian random variables, denoted by Hence, the channel matrix can be given as

where and are the LOS component and the NLOS component, respectively. Their specific expressions are as follows:

where represents the NLoS component characterized by the continuous angular spreading function. While the integral form in (8) provides a rigorous theoretical description of the continuous multipath environment, evaluating this integral is computationally intractable for practical system design. Moreover, in physical propagation scenarios, the NLoS component is typically dominated by a finite number of significant scattering clusters (e.g., buildings or terrain features). Therefore, consistent with the classic virtual channel representation and standard multipath modeling approaches [31], we adopt the finite-scatterer model to approximate the NLoS component. By discretizing the continuous integral into M distinct propagation paths, the NLoS channel vector can be expressed as a superposition of steering vectors:

where M denotes the number of scattering paths (or clusters), represents the complex path gain of the m-th path, and are the corresponding elevation and azimuth angles. This discrete model aligns with the simulation setup employed in Section 4 and facilitates the derivation of the statistical covariance matrix. By performing normalization on and , we obtain

where K is the Rician factor.

According to Shannon’s formula, for the k-th UE, the instantaneous achievable rate can be expressed as follows:

where aggregates all beamforming vectors between APs and UEs. For this MA-aided CF system, the long-term ergodic achievable rate can be explicitly formulated as

2.2. CSI-Based Analysis

The long-term ergodic achievable rate derived in (12) serves as a performance metric for a specific realization of small-scale fading and a given beamforming design . To maximize system performance, ideally, MA positions and instantaneous beamforming vectors should be jointly optimized based on instantaneous channel state information (CSI). However, in practical MA-aided systems, there exists a fundamental timescale mismatch between the mechanical movement of MA elements and the variation of wireless channels. Specifically, the mechanical adjustment of MA positions typically operates on a timescale of seconds, whereas the small-scale fading of the wireless channel varies on a timescale of milliseconds (i.e., the coherence time). Consequently, acquiring instantaneous CSI for all continuous candidate positions to perform real-time position updates is prohibitively expensive and practically infeasible. Therefore, the positions of MAs must be determined based on the long-term statistical CSI (e.g., AoDs/AoAs and angular spreads), which remains constant over a relatively long period. Under the statistical CSI framework, the specific instantaneous beamforming vectors cannot be explicitly determined during the position optimization phase. Instead, we focus on optimizing the transmit covariance matrix, denoted as . Mathematically, assuming independent data streams for different users, is defined as the aggregation of the outer products of the beamforming vectors:

where . The matrix serves as a comprehensive statistical descriptor of the transmission strategy. Its diagonal elements, , represent the average transmit power allocated to the i-th antenna, while the off-diagonal elements, , characterize the spatial correlation between the signals transmitted from the i-th and j-th antennas. By optimizing , we essentially optimize the spatial power spectrum and the directionality of the transmitted signals to match the statistical eigenstructure of the channel, without needing to track the rapid phase variations of the instantaneous channel.

Accordingly, we adopt the ergodic sum capacity as the optimization objective, which represents the theoretical performance upper bound of the system. Let denote the global channel matrix aggregating channel vectors from all L APs to all K users. Based on information theory, the ergodic sum capacity is given by the following:

where the expectation is taken over the random spatial spreading function G. By maximizing (14), we can determine the statistically optimal antenna positions and the covariance matrix that offers the highest potential for data transmission.

2.3. Problem Formulation

Our objective is to maximize the ergodic achievable data rate by jointly optimizing the locations of MA elements and beamforming vectors across all APs under power constraints and antenna spacing constraints. Therefore, the problem can be formulated as a long-term statistical optimization problem:

where . Constraints (15d) and (15e) pertain to the transmit covariance matrix . Specifically, constraint (15d) imposes a total transmit power budget on the system, while constraint (15e) ensures that is a valid covariance matrix; i.e., it must be Hermitian positive semidefinite, where is the given maximum transmit power. At the same time, (15c) keeps the distance among MA elements, preventing the coupling effect, and (15b) ensures the element does not move outside the AP’s region. Although the objective is stochastic, the spacing constraints are deterministic and must hold for all realizations.

The problem is challenging due to, firstly, the optimization objective being a non-convex function that incorporates expectations of random states. Secondly, the antenna spacing position constraints also constitute a typical non-convex function.

3. Our Solutions and Proposed Algorithm

To address the non-convexity and stochasticity of the formulated optimization problem (15), we adopt the Constrained Stochastic Successive Convex Approximation (CSSCA) algorithm [30], which is specifically designed for stochastic optimization problems with non-convex objectives and constraints. The core idea of CSSCA is to iteratively construct convex surrogate functions for the non-convex objective and constraint functions, transforming the original intractable problem into a sequence of solvable convex subproblems. This algorithm ensures that the iterations converge to a stationary point of the original problem.

It is worth noting that while convex programming has been successfully applied to antenna configuration problems in other fields—such as the static beam synthesis for Square Kilometer Array (SKA) stations [32]—our CSSCA-based approach represents a significant methodological shift. Specifically, while the framework in [32] employs convex optimization for the static design of array layouts to minimize sidelobes, our proposed framework is a stochastic optimization solution designed for the dynamic reconfiguration of MAs. By iteratively constructing convex surrogates, the CSSCA algorithm effectively handles the non-convexity and stochasticity inherent in time-varying wireless channels, allowing the antenna positions to be adaptively optimized based on channel statistics rather than remaining in a one-time fixed geometry.

3.1. Assumptions

Before designing the algorithm, to guarantee the convergence of the proposed CSSCA algorithm to a stationary point, the following assumptions are made regarding the system model and the formulated problem.

Assumption 1

(Smoothness and Boundedness). The objective function and the constraint functions (e.g., antenna spacing constraints) are continuously differentiable with respect to the optimization variables and . Furthermore, their gradients and Hessians are uniformly bounded over the feasible sets and the power constraint set. This holds true for our model as the channel response comprises smooth exponential functions of positions, and the feasible regions are compact.

Assumption 2

(i.i.d. Random Process). The sequence of random spatial spreading functions (representing the stochastic NLoS fading components) generated during iterations is a stationary and ergodic stochastic process. Specifically, the random scatterers in each iteration are assumed to be independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.), which aligns with the Rician fading channel model.

Assumption 3

(Strong Convexity). The recursive surrogate functions constructed in the algorithm are uniformly strongly concave with respect to and . This is explicitly enforced in our algorithm design by introducing negative quadratic regularization terms (scaled by and ) in the surrogate function construction.

3.2. Algorithm Design

Each iteration of CSSCA consists of three key steps: surrogate function update, convex subproblem solving (objective update or feasibility update), and variable update. We will now introduce these three parts in separate sections.

Since the objective function involves the expectation over random channel states with high-dimensional distributions, deriving a closed-form expression or computing the exact gradient is computationally intractable. Furthermore, the non-convex antenna spacing constraints pose additional challenges. To address these issues, we adopt the CSSCA framework by constructing and recursively updating a sequence of convex surrogate functions to approximate the original stochastic problem. In our problem, since there is no coupling between the optimization variables and the constraints are mutually independent, the recursive surrogate objective function .

In the q-th iteration, a new random channel realization is obtained. We construct surrogate functions for and , respectively, to decouple the variables and handle the stochasticity.

We construct strongly concave surrogate functions for the objective function to facilitate the parallel optimization of and . The surrogate functions are updated recursively to filter out the stochastic noise from the instantaneous channel samples . Specifically, for the covariance matrix , the surrogate function in the q-th iteration is constructed as follows:

where is a regularization parameter ensuring strong concavity. The coefficient matrix accumulates the gradient information and is updated as follows:

where is the instantaneous gradient derived from the current channel sample.

Similarly, the surrogate function for the antenna position is defined as with the coefficient vector updated recursively using the position gradient .

For the non-convex constraint (15c), use a first-order Taylor expansion to obtain an affine function.

Meanwhile, in the cell-free system, the channels between APs and UEs are statistically independent, but APs collaborate via CPU to optimize their positions and transmit beamforming vectors. In a single iteration, the optimization problem becomes as follows:

Due to the stochastic nature of the updates and the linearization approximation, the subproblem with strict constraints in Equation (19f) may occasionally become infeasible, especially in the early stages of optimization. To ensure the robustness of the algorithm, we propose a two-stage solving mechanism: we first attempt to solve the capacity maximization problem subject to the linearized constraints; if the standard problem is infeasible, we switch to a feasibility restoration phase. We introduce a slack variable and solve the following relaxed problem:

physically, represents the relaxation margin for the antenna spacing constraint. When , it implies that the original strict spacing constraint (15c) is fully satisfied. It is important to emphasize that while linearization of non-convex constraints is standard in deterministic optimization, it faces a critical challenge in the considered stochastic framework. Due to the randomness of the channel realizations and the recursive update of surrogate functions, the linearized constraints in (19f) may occasionally contradict each other, rendering the standard subproblem (19) infeasible (i.e., the feasible set becomes empty). Without the proposed slack mechanism, the iterative process would terminate prematurely. The feasibility restoration phase in (20) effectively resolves this by minimizing the violation metric , thereby guaranteeing that the algorithm effectively “survives” these infeasible instances and continues to converge towards a stationary point. This mechanism guarantees that the algorithm can always return a valid update direction, preventing premature termination.

To ensure the algorithm converges and maintains efficiency, initialization is essential. We set , and are constant, ensuring the strong convexity of proxy functions. Step length satisfies .

By resolving the above issues, we obtained the optimal solutions and for the iteration. Using the recursive method, the variables are updated as follows:

where is the step size for variable updates, satisfying , , and .

3.3. Problem Solving

In a single iteration, the variables and are optimized independently, so the optimization problem can be viewed as two subproblems. By analyzing problems (19), a parallel solution for the algorithm can be derived. When (19) is feasible, the iterative parallel solution is as follows:

When (19) becomes infeasible and switches to solve (20), since the infeasibility stems from antenna separation constraints, does not require re-computation. The algorithm’s solution is as follows:

The overall algorithm is summarized in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1 Constrained Stochastic Successive Convex Approximation (CSSCA) |

|

4. Simulations

In this section, we numerically evaluate the performance of the proposed MA-enhanced Cell-Free Massive MIMO system using the developed CSSCA algorithm. We consider a typical deployment scenario where the system consists of distributed APs serving a group of single-antenna UEs. Both APs and UEs are assumed to be located at fixed coordinates within the service area. Unless otherwise specified, the operating frequency is set to 30 GHz, which corresponds to a carrier wavelength of mm. Regarding movement constraints, the MA elements in each AP are confined within a square region of size . To capture the characteristics of practical wireless propagation, the wireless channel is modeled using Rician fading, which accounts for both the LoS and NLoS components. The large-scale fading follows the free-space path loss model. Small-scale fading comprises a deterministic LoS component and stochastic NLoS components, where the NLoS part is simulated as a sum of five random propagation paths. The elevation angles of AoDs/AoAs are assumed to be i.i.d. variables uniformly distributed over , while the azimuth angles follow a uniform distribution over . For the proposed CSSCA algorithm, to ensure convergence, the step sizes of algorithm are set to decay as and .

4.1. Convergence

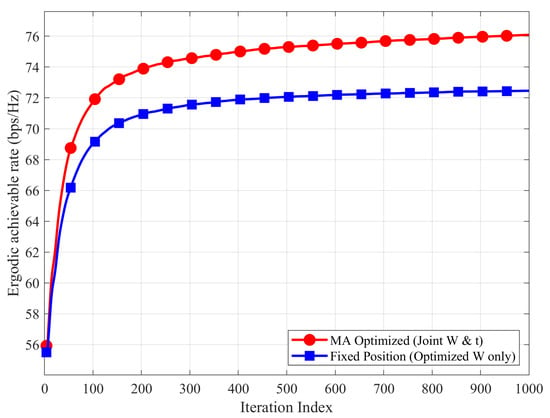

Figure 2 illustrates the convergence behavior of the proposed CSSCA algorithm in terms of the ergodic capacity versus the iteration index. The red curve represents the proposed MA-enhanced scheme, while the blue curve represents the conventional fixed-position scheme (optimized W only). Both schemes exhibit good convergence properties. The ergodic achievable rates fluctuate initially due to the stochastic nature of the channel samples and the step-size adaptation in the early stage of the CSSCA algorithm. However, as the iterations proceed, both curves tend to stabilize, verifying the convergence guarantee of the proposed algorithm for solving the non-convex stochastic optimization problem. The proposed MA optimized scheme consistently achieves a higher ergodic capacity compared to the fixed-position scheme after convergence. Specifically, the MA system stabilizes at approximately 76.1 bps/Hz, while the fixed system stabilizes around 72.4 bps/Hz. This performance gap demonstrates that by locally adjusting the antenna positions within a confined region , the MA system can effectively reshape the channel spatial correlation and exploit additional spatial degrees of freedom (DoFs) to enhance the signal-to-interference-plus-noise ratio (SINR).

Figure 2.

Convergence behavior of the proposed CSSCA algorithm: ergodic capacity versus iteration index.

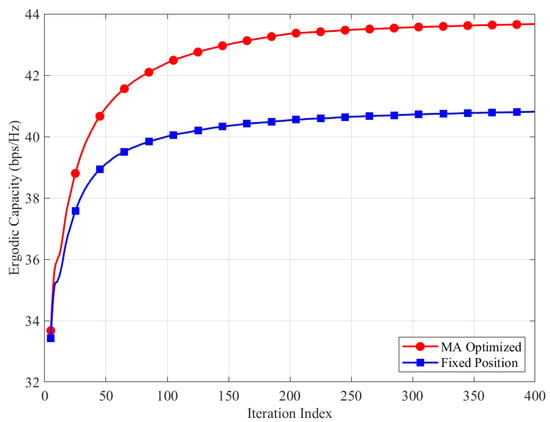

While Figure 2 illustrates the detailed evolution of the objective function for a single channel realization, we further evaluate the algorithmic robustness via Monte Carlo simulations. Figure 3 displays the average convergence behavior over 50 independent realizations, where the positions of APs and UEs are randomly and independently redistributed in each trial.

Figure 3.

Average convergence behavior of the proposed CSSCA algorithm over 50 independent Monte Carlo realizations with random AP/UE placements.

As shown in Figure 3, the algorithm maintains a consistent and rapid convergence rate across different network topologies, typically reaching a stationary point within approximately 400 iterations. This statistical consistency confirms that the proposed optimization framework is highly reliable and insensitive to specific user distributions or large-scale fading patterns, ensuring stable performance gains in practical cell-free deployments.

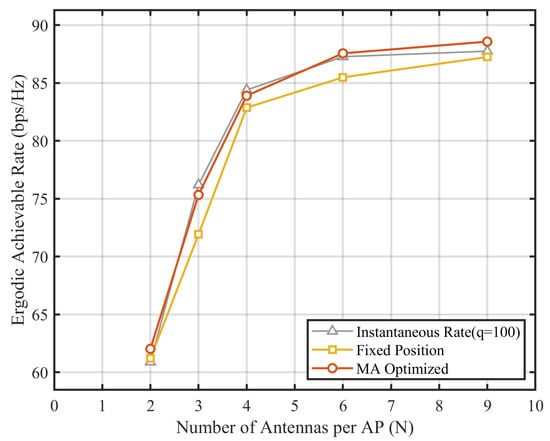

4.2. Impact of Number of Antennas

Figure 4 investigates the impact of the number of MA elements per AP, denoted by N, on the system performance. The simulation is conducted with APs and UEs, varying N from 2 to 9. Meanwhile, the system operates at dBm. As illustrated in Figure 4, the ergodic achievable rate for both the MA-enhanced scheme (red curve) and the fixed-position scheme orange curve) increases significantly with N. This trend is expected, as a larger number of antennas provides higher array gains and spatial resolution, allowing for more effective interference mitigation among the 20 UEs. Crucially, the proposed MA-enhanced scheme consistently outperforms the fixed-position benchmark across all considered values of N. This performance gap highlights the advantage of antenna position optimization: even with a small number of elements (e.g., ), the MA system can flexibly adjust the antenna coordinates within the region to capture stronger signal components and minimize spatial correlation, thereby unlocking additional spatial DoFs that are inaccessible to fixed uniform arrays. It is also worth noting that the rate improvement exhibits a diminishing return trend and tends to saturate when N becomes large (e.g., ). This saturation phenomenon can be attributed to two factors: (1) the limited spatial DoFs provided by the finite number of scattering clusters () in the channel model; and (2) the physical constraints of the movement region (), which becomes crowded as antenna density increases, limiting the freedom for further position optimization under the minimum spacing constraint .

Figure 4.

Average achievable rate versus the number of antennas per AP (N). The red and orange curves represent the ergodic capacities of the proposed MA-enhanced scheme and the fixed-position benchmark, respectively.

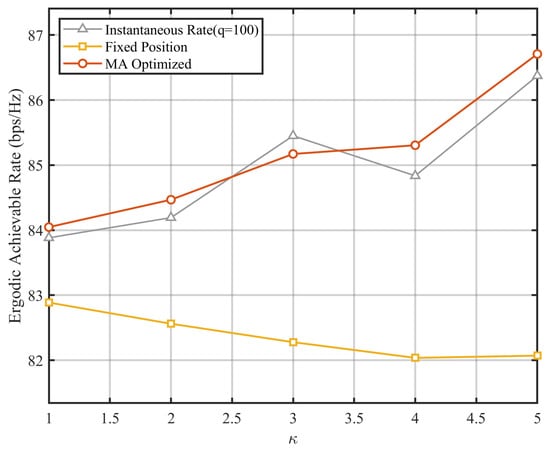

4.3. Impact of Rician Factor

Figure 5 illustrates the impact of the Rician -factor on system performance. As the -factor increases (indicating a stronger deterministic LoS component), the proposed MA scheme (red curve) exhibits a steady performance improvement. This is because the flexible MA positions can be optimized to perfectly align with the dominant LoS path, thereby maximizing array gain.

Figure 5.

Ergodic achievable rate versus Rician factor (). The red and orange curves represent the performance of the proposed MA-enhanced scheme and the fixed-position benchmark, respectively. The gray curve indicates the instantaneous rate of the MA scheme at a specific iteration () for reference.

In contrast, the fixed-position benchmark (orange curve) exhibits slight performance degradation as the Rician -factor increases. This phenomenon is primarily driven by the increased spatial correlation among users. Although a strong LoS component typically implies a stable channel, our model employs power normalization to isolate the impact of spatial structure. Consequently, a higher K-factor suppresses the rich-scattering components (NLoS) that usually provide angular diversity. Without this multipath diversity, the channel vectors of users with similar angles of arrival become highly correlated for fixed-antenna arrays, leading to severe rank deficiency. This results in elevated interuser interference that cannot be effectively mitigated by fixed arrays, thereby limiting the system capacity despite the high signal strength.

Crucially, the MA-enhanced scheme consistently outperforms the fixed benchmark regardless of the -factor value. This demonstrates the robustness of MA systems: they effectively exploit multipath diversity in rich-scattering environments (low ) and maximize array gain in LoS-dominant scenarios (high ), maintaining a significant advantage over fixed arrays in diverse channel conditions.

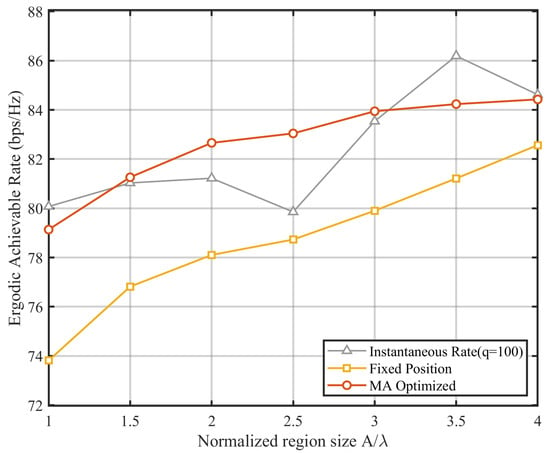

4.4. Impact of Movable Area

Figure 6 investigates the impact of the normalized movement region size, defined as , on system performance. The simulation varies the region size from to while keeping other parameters constant. As shown in Figure 6, the ergodic achievable rate for the proposed MA-enhanced scheme (red curve) exhibits a steady upward trend as the region size increases. This is because a larger movement area provides more spatial degrees of freedom for the antennas to explore, increasing the probability of finding positions with better channel conditions (e.g., higher channel gain or lower spatial correlation). In contrast, the fixed-position benchmark (orange curve) shows a relatively slower rate of increase. The performance gap between the MA-enhanced scheme and the fixed-position scheme widens as the region size expands, particularly from to , indicating that even a small increase in the available movement area can be effectively exploited by the MA system to achieve significant performance gains. Interestingly, the rate improvement for the MA scheme tends to saturate when the region size exceeds . This suggests that beyond a certain point, further expanding the movement region yields diminishing returns, likely due to the limited number of scattering clusters in the environment, which bounds the maximum achievable spatial diversity gain. The instantaneous rate (gray curve) fluctuates around the ergodic average but generally follows the same increasing trend, confirming the robustness of the optimization process.

Figure 6.

Ergodic achievable rate versus the normalized region .

It is worth noting that as the normalized region size increases, the performance gap between the MA-enhanced scheme and the fixed-position benchmark tends to narrow. This phenomenon can be fundamentally explained by the concepts of effective aperture and spatial sampling.

For the fixed-position scheme, expanding the region size naturally increases the inter-element spacing, thereby enlarging the effective aperture of the antenna array. A larger aperture provides higher spatial resolution, enabling the fixed array to better distinguish between different angular paths and reducing the spatial correlation among antennas. From the perspective of spatial sampling, the wireless channel contains a finite number of dominant scattering clusters (i.e., finite spatial degrees of freedom). When the region size is small, the fixed array is spatially undersampled, and MAs provide a critical advantage by moving antennas to capture signal energy that fixed antennas miss. However, as the region expands, the fixed array becomes capable of sufficiently sampling the spatial field to resolve these multipath components. Consequently, the marginal gain offered by the micro-scale position optimization of MAs diminishes, as the static array configuration with a large aperture is already capable of harvesting the majority of the available spatial diversity gain.

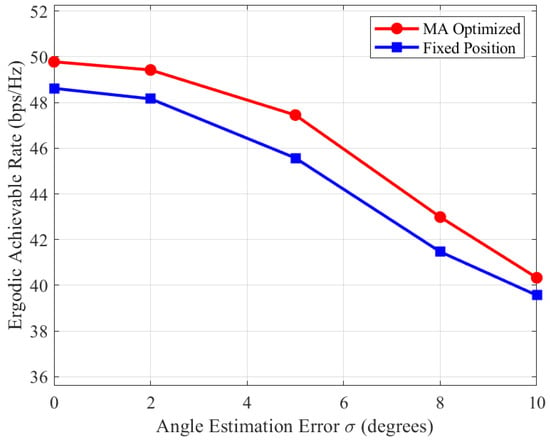

4.5. Robustness Analysis Against CSI Errors

In the simulations above, perfect statistical CSI (i.e., exact AoDs/AoAs and angular spreads) was assumed. However, in practical deployments, the acquisition of statistical CSI is inevitably subject to estimation errors. To evaluate the robustness of the proposed framework, we investigate the impact of imperfect statistical CSI on system performance. Specifically, the estimated angles are modeled as , where represents the true angle (AoD or AoA) and represents the estimation error, which follows a Gaussian distribution with zero mean and standard deviation .

Figure 7 illustrates the ergodic achievable rate versus the angle estimation error standard deviation , varying from to . As expected, the performance of both the MA-enhanced scheme and the fixed-position benchmark degrades as the estimation error increases. This degradation arises because the transmit covariance matrix and antenna positions are optimized based on inaccurate channel statistics, leading to a mismatch with the actual propagation environment. However, it is observed that the performance degradation is gradual (graceful degradation). Crucially, the proposed MA-enhanced scheme consistently outperforms the fixed-position benchmark across the entire considered range of . Even at a high error level of , the MA system maintains a substantial performance gain (approximately 0.5 bps/Hz higher than the fixed scheme). This demonstrates that the proposed algorithm is robust to reasonable CSI imperfections and can effectively exploit the additional spatial degrees of freedom even with coarse statistical information.

Figure 7.

Ergodic achievable rate versus the angle estimation error standard deviation .

5. Discussion

5.1. Computational Complexity

The complexity of the proposed algorithm is dominated by convex subproblems, scaling as per iteration. In our simulations, the average execution time is approximately 30 s per iteration, which is largely attributed to the overhead of the generic CVX solver. However, it is crucial to note that our system relies on statistical CSI rather than instantaneous CSI. Since statistical channel parameters (e.g., AoAs) vary slowly over seconds or minutes, the optimization can be performed offline or at a low frequency. Thus, the computational latency is well-tolerated in practice, as the solution remains valid for a long coherence block.

5.2. Hardware Feasibility

Regarding the practical implementation, the MA mechanism driven by electromechanical drivers (e.g., stepper motors) is feasible in terms of speed, precision, and power consumption. First, although the mechanical response time (hundreds of milliseconds) is slower than electronic switching, it is negligible compared to the long coherence time of statistical CSI, ensuring stable transmission. Second, modern drivers achieve micrometer-level precision, which is sufficient for effective spatial diversity at centimeter-level wavelengths. Finally, since the antennas only move sporadically to adapt to large-scale user movements, the mechanical power consumption is minimal compared to the RF transmission power.

5.3. Statistical CSI Acquisition

In practical deployments, the acquisition of statistical CSI is a prerequisite for the proposed scheme. In Time Division Duplexing (TDD) systems, which are typical for cell-free architectures, statistical CSI can be efficiently acquired at the CPU by leveraging channel reciprocity. Specifically, the APs can estimate the channel covariance matrices by averaging the outer products of uplink pilot observations over multiple coherence blocks. Alternatively, super-resolution algorithms (e.g., MUSIC or ESPRIT) can be employed to extract the dominant angles of arrival (AoAs) and path gains from the uplink pilots to reconstruct the covariance matrices.

5.4. Scalability and Practical Complexity Trade-Offs

While the numerical results presented above demonstrate the superiority of MAs in idealized settings, it is meaningful to discuss the implications for realistic large-scale deployments and the justification for the added hardware complexity.

In larger cell-free networks, the dominant performance bottleneck shifts from noise to interuser interference. In such interference-limited regimes, the ability of MAs to reshape channel vectors offers a distinct advantage over fixed-position antennas (FPAs). By fine-tuning antenna positions, MAs can actively avoid deep fading spots and mitigate strong co-channel interference, a capability that becomes increasingly valuable as network density grows. Regarding movement constraints, while a smaller movable region naturally limits the achievable spatial diversity, the short wavelengths in high-frequency bands (e.g., mmWave) imply that even compact regions can encompass significant channel variations, preserving the utility of MAs.

Furthermore, regarding the comparison with conventional alternatives, the MA architecture offers unique benefits that justify its complexity:

- Space Efficiency: Unlike the approach of simply increasing antenna spacing, which significantly enlarges the physical form factor of APs, MAs enable the exploitation of spatial diversity within a compact, constraint-compliant volume. This is critical for space-limited deployments such as indoor hotspots or IoT sensors where expanding the device size is infeasible.

- Channel Reconfiguration: Traditional methods such as transmit covariance optimization (precoding) are passive techniques limited by the fixed channel state. If the channel matrix is rank-deficient or ill-conditioned (e.g., due to user alignment), digital processing faces a fundamental ceiling. In contrast, MAs are active components that physically reconfigure the propagation environment to improve the condition number of the channel matrix, thereby unlocking performance gains that are unattainable through signal processing alone.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we have investigated the potential of movable antenna (MA) technology in enhancing the performance of Cell-Free Massive MIMO systems. We proposed a robust transmission design framework based on long-term statistical CSI, formulating a joint optimization problem for MA positions and the transmit covariance matrix to maximize the system’s ergodic sum capacity. To tackle the inherent non-convexity and stochastic nature of the problem, we developed a Constrained Stochastic Successive Convex Approximation (CSSCA) algorithm, incorporating a slack-variable mechanism to guarantee feasibility under strict antenna spacing constraints.

Numerical results demonstrate that the proposed MA-aided scheme significantly outperforms conventional fixed-position benchmarks. Our analysis reveals that even with a limited number of antennas or confined movement regions, the MA system can effectively exploit additional spatial degrees of freedom to reshape channel conditions and mitigate fading. Furthermore, the proposed scheme exhibits robust performance gains across various propagation environments, from rich-scattering to LoS-dominant scenarios.

While the proposed framework demonstrates significant performance gains, several practical limitations warrant further investigation.

- Hardware and Control Overhead:The implementation of MAs requires precise mechanical actuators, which introduce hardware complexity and additional power consumption. The control overhead associated with antenna movement may also limit the system’s ability to respond to extremely fast environment changes.

- Centralized Nature: Our current solution adopts a centralized optimization approach. In large-scale cell-free deployments, the signaling overhead required to collect statistical CSI and the computational burden at the central processing unit (CPU) could become significant bottlenecks. Future work may explore distributed or sub-optimal low-complexity algorithms to enhance scalability.

- Deployability Gap:There exists a gap between theoretical potential and practical deployment. Factors such as the mechanical wear of moving parts, the limited precision of positioning, and the potential impact of mutual coupling in highly compact regions need to be meticulously addressed in real-world hardware testbeds.

By acknowledging these constraints, we aim to provide a realistic roadmap for the transition of MA technology from theoretical study to practical cellular infrastructure.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.L.; Methodology, Y.Z. and Y.S.; Software, Y.Z. and Y.S.; Validation, Y.Z.; Formal analysis, Y.Z.; Investigation, Y.Z.; Resources, Y.S. and P.W.; Data curation, Y.Z., Y.S. and P.W.; Writing—original draft, Y.Z. and P.W.; Writing—review and editing, Y.Z. and P.W.; Supervision, F.L.; Project administration, F.L.; Funding acquisition, F.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) under Grant No. 62201239 and Jiangxi Provincial Natural Science Foundation under Grant No. 20224BAB212003, in part by the Open Project Fund of the Key Laboratory of Numerical Simulation for Large-Scale Complex Systems, Ministry of Education.

Data Availability Statement

All data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Saad, W.; Bennis, M.; Chen, M. A Vision of 6G Wireless Systems: Applications, Trends, Technologies, and Open Research Problems. IEEE Netw. 2020, 34, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Guo, X.; Zhou, G.; Jin, S.; Ng, D.W.K.; Wang, Z. Unified Far-Field and Near-Field in Holographic MIMO: A Wavenumber-Domain Perspective. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2025, 63, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, T.; Xu, Y.; Liu, F.; Xu, H.; Han, Z. Task Offloading and Resource Allocation for Satellite-Terrestrial Integrated Networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 262–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzetta, T.L. Noncooperative Cellular Wireless with Unlimited Numbers of Base Station Antennas. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2010, 9, 3590–3600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Marzetta, T.L. A Macro Cellular Wireless Network with Uniformly High User Throughputs. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE 80th Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC2014-Fall), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 14–17 September 2014; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Han, Z. Angular-Distance Based Channel Estimation for Holographic MIMO. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2024, 42, 1684–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, H.Q.; Ashikhmin, A.; Yang, H.; Larsson, E.G.; Marzetta, T.L. Cell-Free Massive MIMO Versus Small Cells. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2017, 16, 1834–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammar, H.A.; Adve, R.; Shahbazpanahi, S.; Boudreau, G.; Srinivas, K.V. User-Centric Cell-Free Massive MIMO Networks: A Survey of Opportunities, Challenges and Solutions. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2022, 24, 611–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björnson, E.; Sanguinetti, L. Scalable Cell-Free Massive MIMO Systems. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2020, 68, 4247–4261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Marzetta, T.L. Energy Efficiency of Massive MIMO: Cell-Free vs. Cellular. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 87th Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC Spring), Porto, Portugal, 3–6 June 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, E.; Zhang, J.; Du, H.; Ai, B.; Yuen, C.; Niyato, D.; Letaief, K.B.; Shen, X. RIS-Aided Cell-Free Massive MIMO Systems for 6G: Fundamentals, System Design, and Applications. Proc. IEEE 2024, 112, 331–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, T.J.; Qi, M.Q.; Wan, X.; Zhao, J.; Cheng, Q. Coding metamaterials, digital metamaterials and programmable metamaterials. Light Sci. Appl. 2014, 3, e218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, P. Robust Beamforming for Active Reconfigurable Intelligent Omni-Surface in Vehicular Communications. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2022, 40, 3086–3103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Cao, K.; Ding, H.; Lv, L.; Ye, Y.; Chi, H.; Wang, T.; Yang, L. Double-RIS Enabled Physical Layer Security for Wireless-Powered Communication Systems Over Rayleigh Fading Channels. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2025, 73, 9517–9535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shojaeifard, A.; Wong, K.K.; Tong, K.F.; Chu, Z.; Mourad, A.; Haghighat, A.; Hemadeh, I.; Nguyen, N.T.; Tapio, V.; Juntti, M. MIMO Evolution Beyond 5G Through Reconfigurable Intelligent Surfaces and Fluid Antenna Systems. Proc. IEEE 2022, 110, 1244–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.K.; Shojaeifard, A.; Tong, K.F.; Zhang, Y. Fluid Antenna Systems. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2021, 20, 1950–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New, W.K.; Wong, K.K.; Xu, H.; Wang, C.; Ghadi, F.R.; Zhang, J.; Rao, J.; Murch, R.; Ramirez-Espinosa, P.; Morales-Jimenez, D.; et al. A Tutorial on Fluid Antenna System for 6G Networks: Encompassing Communication Theory, Optimization Methods and Hardware Designs. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2025, 27, 2325–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Ma, W.; Zhang, R. Movable Antennas for Wireless Communication: Opportunities and Challenges. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2024, 62, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Ma, W.; Zhang, R. Modeling and Performance Analysis for Movable Antenna Enabled Wireless Communications. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2024, 23, 6234–6250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, R. MIMO Capacity Characterization for Movable Antenna Systems. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2024, 23, 3392–3407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, C.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, L.; Wang, Y. Learning-Based Joint Beamforming and Antenna Movement Design for Movable Antenna Systems. IEEE Wirel. Commun. Lett. 2024, 13, 2120–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Wu, P.; Ning, B.; Zhu, L. Sum Rate Maximization for Movable Antenna Enabled Uplink NOMA. IEEE Wirel. Commun. Lett. 2024, 13, 2140–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Zhou, Z.; Li, W.; Wang, C.; Lin, L.; Jiao, B. Movable Antenna-Enabled Co-Frequency Co-Time Full-Duplex Wireless Communication. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2024, 28, 2412–2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, J.; Du, Q.; Niyato, D.; Han, Z. Deep Learning-Assisted Jamming Mitigation With Movable Antenna Array. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2025, 74, 14865–14870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; An, J.; Li, H.; Gan, L.; Yuen, C. Algorithm-Unrolling-Based Distributed Optimization for RIS-Assisted Cell-Free Networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 944–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Ge, J.; Zhi, K.; Pan, C.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, J.; You, X. Two-Timescale Transmission Design for RIS-Aided Cell-Free Massive MIMO Systems. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2024, 23, 6498–6517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Yang, Y.; Lyu, B.; Yang, Z.; Jamalipour, A. Movable-Antenna-Enhanced Wireless-Powered Mobile-Edge Computing Systems. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 35505–35518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Ma, W.; Ning, B.; Zhang, R. Movable-Antenna Enhanced Multiuser Communication via Antenna Position Optimization. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2024, 23, 7214–7229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Lyu, W.; Ning, B.; Zhang, Z.; Yuen, C. Flexible Precoding for Multi-User Movable Antenna Communications. IEEE Wirel. Commun. Lett. 2024, 13, 1404–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Lau, V.K.N.; Kananian, B. Stochastic Successive Convex Approximation for Non-Convex Constrained Stochastic Optimization. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2019, 67, 4189–4203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayeed, A. Deconstructing multiantenna fading channels. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2002, 50, 2563–2579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, G.M.; Caruso, G.; Bolli, P.; Palmeri, R.; Morabito, A.F. Square Kilometre Array Enhancement: A Convex Programming Approach to Optimize SKA-Low Stations in the Case of Perturbed Vogel Layout. Sensors 2025, 25, 5039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.