Abstract

This work proposes a generic model for clarifying the mechanism hidden in the phenomena of fluctuation propagation in grid-forming (GF-VSG) systems, considering the impact of different disturbances. Additionally, a new judgment criterion is established to give physical insights into the power oscillation stability of the GFMC system. And this judgment criterion, as well as the model, can identify the power stability combined with fluctuation propagation phenomenon no matter what the disturbance is, which can also give guidance to the controller design to guarantee that the GFMC can operate in normal operation conditions while leisurely confronting various disturbances. In addition, it is found that the established conventional single closed-loop system may lose effectiveness in judging stability, especially when the oscillation propagation of disturbance occurs. Finally, the proposed model and judgment criteria are demonstrated by experiments.

1. Introduction

The GRID-FORMING virtual synchronous generator (GFVSG) has been emerging in ever-increasing popularity as the interface technology between renewable energy and the power grid [1,2]. This popularity has significantly alleviated the burden of environmental pollution and the energy crisis [3]. Although the integration of a grid-forming converter (GFMC) can improve the environment of a power grid and thus provide active inertia and damping support, the dynamic interaction between the GFMC and the power network is inevitable, which aggravates the secure operation of the system under certain scenarios [4]. Therefore, this aggravation deserves to be emphasized and focused on, where the stability mechanism hidden in the instability phenomenon is in urgent need of exploration.

The stability studies of GFMCs attached to power networks can be mainly categorized into three types, i.e., frequency stability [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12], voltage stability [6,8,10,11,12], and power oscillations [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. Indeed, those types of stability issues are the essential key to guarantee the stable operation of the systems, especially for the grid-friendly integration and active support of GFMCs.

As an example, a magnitude phase motion equation (MPME) model was established to explore the damping and synchronizing torque and evaluate the frequency oscillation stability of the GFMC system [4]. Moreover, the low-frequency oscillation (LFO) of the GFMC system was analyzed from the perspective of a power angle curve [5], equivalent inertia model [6], and energy trajectory model [7]. Especially in [6], the grid inertia support was implemented by developing the virtual inductance control method for the GFVSG. In addition, a P/Q−ω/V admittance model criterion was proposed for oscillation analysis in a multi-GFMC system [8]. The proposition of this criterion can effectively identify the LFO of the frequency and active power of the system. As we know, the angle is the integral of the frequency. Thus, a quantitative framework was built up for the analysis of the coupling between frequency dynamics and power angle oscillation [9].

At present, frequency–voltage coupling issues have been one of the mainstream focuses of researchers. Aroused by this requirement, a modeling method, which can judge the frequency–voltage coupling effect, was proposed to evaluate the oscillation propagation between frequency and voltage [10]. It was found that frequency oscillations are not always coupled with voltage oscillations, especially when the oscillation propagation is suppressed. Furthermore, a self-stability and induced-stability generic framework was proposed to judge the frequency and voltage oscillation, as well as their coupling effect [12].

Power oscillation also deserves to be focused on, as the stable power is key to the provision of good inertia support. Thus, it is of great significance to study the mechanism of power oscillations in a GFMC system. The power oscillation mechanism was clarified by a state space model with modal analysis [13,19,21], and from the perspective of power coupling between active and reactive power [14,15,16,17,18,22,23]. In [13], the active power oscillation was illustrated by the derived state space model with eigenvalue analysis, where an acceleration control was proposed for paralleled GFMCs. Furthermore, the interactive power oscillation mechanism method and the suppression strategy were proposed for the paralleled VSG in islanded microgrids [19,21].

Moreover, the power coupling characteristics analysis was developed in GFMC systems by taking the state-of-charge characteristics of energy storage into consideration [14]. In addition, the coupling effect mechanism of the GFMC system was clarified at the synchronous frequency by means of a small-signal model [15]. In [16], the cross-coupling effect between voltage control and active power control was proposed to identify the power coupling mechanism with a varying short circuit ratio.

Additionally, an enhanced power decoupling strategy was proposed to implement decoupling between active and reactive power to improve the stability of the system [18]. Also, the power coupling effect mechanism was elaborated from the perspective of the power flow model [22]. In [23,24], the authors propose effective approaches to enhancing the stability of grid-forming VSGs under weak-grid and low-inertia conditions—one through a frequency stability analysis framework, and the other via a damping correction-based control strategy.

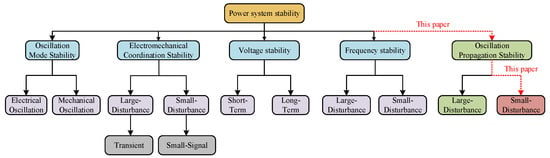

In [25,26], the authors provide relevant discussions on low-inertia systems, multi-converter interactions, and weak-grid conditions, offering important insights that support the present study. In Figure 1, this paper focuses only on small disturbances.

Figure 1.

Classification of power system stability [17].

Therefore, a classification of the pieces of literature is developed to highlight their contributions, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Contribution classification.

Although the prior studies have considered the power coupling effect to evaluate the power oscillation and frequency stability using different models, the impact of different disturbances on the power oscillation stability was rarely discussed. The oscillation propagation phenomenon between frequency and voltage in the VSG system has been clarified by the proposed model, but the fluctuation propagation effect considering the impact of disturbances was not clarified in GFMC system. Moreover, as the GFMC penetrates into the power network, its complexity is becoming more and more complicated. Indeed, the traditional single-input–single-output system cannot accurately capture the power stability of the system anymore. To fill in this blank, this work proposes a generic model to identify the stability mechanism of active and reactive power in a GFMC system with the impact of different disturbances. Different from the traditional model, the proposed model can quantitatively identify the impact of disturbances on power oscillation while clarifying the phenomena of fluctuation propagation intuitively. The criterion has generality and unified characteristics, which are finally validated by experiments. The main contributions are organized as follows:

- (1)

- The generic model for fluctuation propagation is first proposed, taking the different disturbances into consideration in a GFMC system, where the physical significance of fluctuation propagation is thoroughly clarified.

- (2)

- The different fluctuation propagation paths have been established to give physical insight into the fluctuation propagation in GFMC systems, where the criterion is proposed to judge the power oscillation stability of the system under various conditions.

- (3)

- The impact of disturbances on fluctuation propagation can be quantitatively identified by the proposed model, which can give guidance to controller design to avoid fluctuation propagation and guarantee the good stability margins of the power when GFMCs provide inertia support.

It is found that the single-input–single-output (SISO) model loses accuracy in judging power stability, particularly in cases where fluctuation propagation occurs. This generic model can illustrate that the power oscillation stability mechanism is not restricted to type of disturbances.

2. Fundamentals

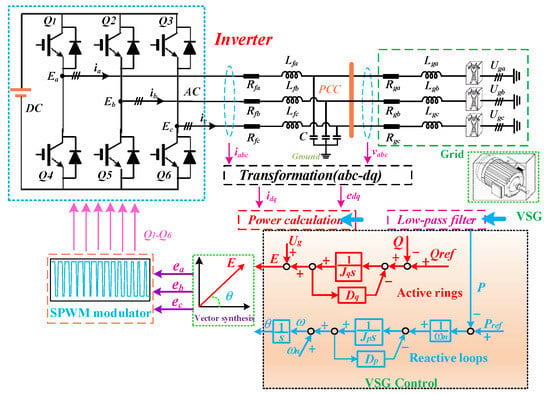

Figure 2 illustrates the topology and control methodologies of the GFMC system. Based on Kirchhoff’s Law, the voltage circuit equation can be formulated in the rotating inertial reference frame as follows:

where L = Lf + Lg, R = Rf + Rg, Ed, Eq, Id, and Iq are the d- and q-axis components of the output voltage and the grid-connected current. Ud and Uq denote the d- and q-axis components of the grid voltage. Furthermore, indicates the phase angle between the inverter output voltage and the grid voltage. represents the total output impedance between point of E and point of U.

Figure 2.

Topology and control strategy of GFMC system.

The inverter current under small-signal conditions can be further calculated as follows:

represents the small-signal inductance matrix used for modeling the current behavior. Notably, the subscript 0 is used throughout this paper to identify the steady-state values of system variables, which serve as the reference for perturbation analysis.

The active power and reactive power of the VSG under small-signal conditions can be further calculated as follows:

The rotor motion equation and voltage equation of the VSG are given by the following:

where Pref is the reference active power and Qref is the reference reactive power. Dp, Dq, Jp, and Jq are the control parameters of the VSG, ‘s’ is the Laplace operator, Ug is the grid voltage, and is the grid angular velocity.

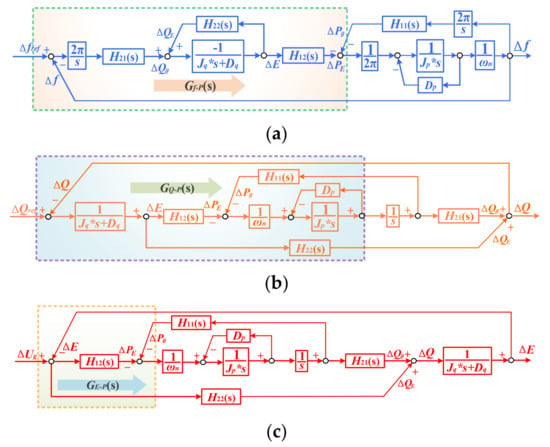

From Figure 3, the open-loop transfer functions of the active and reactive loops are given as follows:

Figure 3.

Model of active and reactive power: (a) active power; (b) reactive power.

Considering the coupling effect between active power and reactive power, the relationship can be expressed as follows:

where H11(s) is the coupling relationship (CR) from θ to P, H12(s) represents the CR from θ to Q, H21(s) denotes the CR from E to P, and H22(s) is the CR from E to Q. Furthermore, I represents the identity matrix.

3. Model and Physical Significance of Fluctuation Propagation Impacted by Disturbance

3.1. Modeling of Fluctuation Propagation Impacted by Disturbances

Motivation of the proposed model: Although the active power loop can analyze the self-stability characteristics and stability margins of active power with input active power disturbance (ΔPref), it cannot address the stability issues with other types of disturbances. To overcome this bottleneck, a fluctuation propagation model (FPM) is proposed, considering the impact of different disturbances, e.g., frequency disturbance, reactive disturbance, and voltage disturbance.

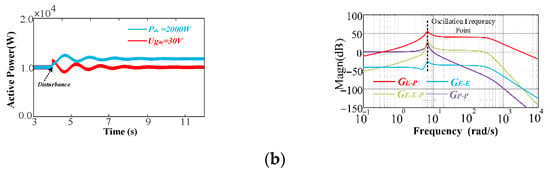

Figure 4 illustrates the fluctuation propagation model (FPM) and its various interaction pathways, where fluctuation dynamics propagate to active power. Specifically, Figure 3a presents the Frequency Self-Stabilizing Loop (FSSL). The dashed box in Figure 4a highlights the oscillation propagation effect, wherein frequency disturbances originating from the virtual synchronous generator (VSG) influence the active power stability.

Figure 4.

The fluctuation propagation model for active power stability: (a) grid frequency disturbance, (b) reactive disturbance, (c) grid voltage disturbance.

Figure 4b depicts the Reactive Self-Stabilizing Loop (RSSL), where the dashed box represents the oscillation propagation effect caused by reactive power disturbances transferring to active power.

Figure 4c illustrates the Voltage Self-Stabilizing Loop (VSSL), with the dashed box emphasizing the oscillation propagation effect of grid voltage disturbances on the active power.

A quantitative model framework is established for systematically characterizing the dynamic coupling between different disturbance sources and active power oscillations, which provides the fundamentals for the design of flowchart guidelines and judgment criteria.

Furthermore, the fluctuation propagation model is derived as follows:

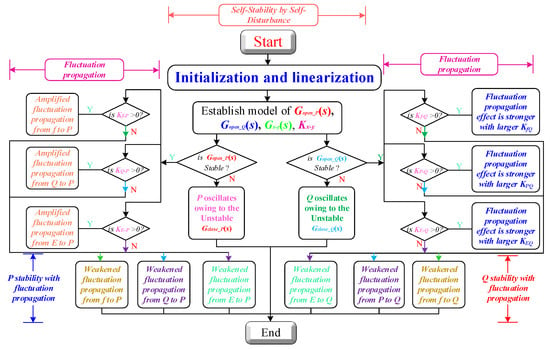

A flowchart for the judgment of fluctuation propagation with the power oscillation stability of the system is presented in Figure 5, where Kxy is defined as the fluctuation propagation factor from variable x to variable y. Gclose_m (s) is defined as the closed-loop transfer function of m with the self-stabilizing loop.

Figure 5.

Flowchart for judging self-stabilizing stability and fluctuation propagation stability in GFMC system.

The procedures for judgments and criteria are summarized as follows:

Step 1: Initialization and linearization: Establish a model of Gclose_P(s), Gclose_Q(s), Gx−y(s), and Kx−y.

Step 2: Judge whether Gclose_P(s) and Gclose_Q(s) are stable or not. If Gclose_P(s) is stable, then jump to Step 3.1. Otherwise, P oscillation occurs, owing to the unstable Gclose_P(s). If Gclose_Q(s) is stable, then jump to Step 3.2. Otherwise, Q oscillation occurs, owing to an unstable Gclose_P(s).

Step 3.1: Based on the judgment results of the stability of Gclose_P(s) in Step 2, determine whether Kf−P is above 0 dB or below 0 dB. If it is greater than 0, the frequency oscillation will be propagated to P with an amplified effect, which will increase the risk of active power oscillation, although P is open-loop stable.

Step 3.2: Following the judgment results in Step 2, determine moreover if KP−Q is above 0. The P fluctuation will be propagated to Q, resulting in Q oscillation, although Q is open-loop stable. Conversely, if KP-Q is less than 0, the fluctuation propagation effect will be suppressed, causing a lower risk of Q fluctuation. In general, this criterion and judgment have a generality with different disturbances. And, from this criterion, it is inferred that the conventional SISO system cannot thoroughly capture the stability characteristics, especially when the fluctuation propagation occurs from different disturbances.

3.2. Analysis

Table 2 presents the stability margins of the self-stabilizing loops from Case 1 to Case 6 under different types of disturbances. Across all six cases, the system consistently exhibits attenuated oscillations under various disturbances. However, an intriguing observation is that the stability margins of the self-stabilizing loops cannot always align with the expected attenuated oscillation behavior. This discrepancy indicates that the traditional VSG-based self-stabilizing loop criterion may fail to accurately assess the system stability when fluctuation propagation occurs with external disturbances. A deeper analysis reveals that the underlying cause of this phenomenon lies in the coupling effect between output variables, which in turn induces fluctuation propagation.

Table 2.

Stability characteristics of various open loops with different disturbances.

In real practical engineering, the diversity of disturbance types leads to various stability characteristics of the systems. Therefore, it is important to explore the impacts of different disturbance types on fluctuation propagation phenomena in the GFMC system to guarantee better inertia support by VSG.

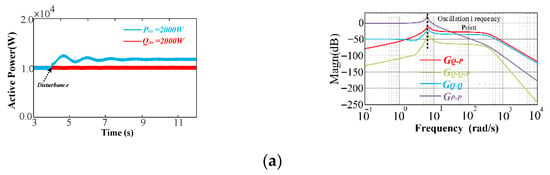

Figure 6 illustrates the oscillatory transferring effects on active power under various disturbance conditions. The left panel presents the time-domain waveforms of active power responses to different disturbances, providing a clear depiction of how disturbances influence the system dynamic behavior. The right panel shows the bode diagrams of different transfer functions under various disturbance types, offering insights into the system stability and the transferring characteristics of oscillation between output variables.

Figure 6.

Waveform and bode diagram of P under different disturbances. (a) reactive disturbance, (b) grid voltage disturbance.

Gxn−y(s) represents the transfer function from x to y. Furthermore, Gxn−xn−y(s) denotes the closed-loop transfer function from x to y, which can be used to assess the impact of disturbances in the input variable xn on the output variable y. Here, xn and y can represent any possible input or output variables. n denotes the category of disturbance.

Furthermore, GQ−Q−P(s) and GE−E−P(s) are derived as follows:

At first, the defined fluctuation propagation factor Kxy, which intuitively reflects the propagation effect from variable x to variable y, is expressed as follows:

where Gx−y is defined as the transfer function from x to y, where x and y can represent random variables.

Therefore, the effects of different disturbances on stability and propagation can be intuitively analyzed through Equations (8) and (9). Moreover, this framework provides a foundation for understanding the underlying dynamic interactions. Based on this, a further quantitative analysis of the oscillation transmission effect among various variables can be conducted.

This observation highlights that the fluctuation propagation effect plays a more dominant role in stability characteristics than the self-stabilizing loop, further reinforcing the validity of the proposed model.

From Figure 6a, it is observed that KQ−Q−P < KP−P, from which it can be concluded that the impact of a reactive power disturbance on the stability of P is smaller than that of an active power disturbance on its own stability. Additionally, KQ−P < 0 indicates a suppressed propagation effect from Q to P, which weakens the effect of Q disturbance propagated to P. This is further confirmed by the results on the left side, where the fluctuation magnitude of active power with an active disturbance is more significant than that of a reactive disturbance. It is noted that the active disturbance is not the active power transmitted to the power grid, but the reference input power.

From Figure 6b, KE−E−P > KP−P, which implies that a grid voltage disturbance imposes a more significant impact on the active power stability than an active disturbance on its own stability. Moreover, the fluctuation propagation factor KE−P > 0 suggests a positive fluctuation propagation effect from E to P, slightly amplifying the propagation effect from E to P. This conclusion is further supported by the results on the left side, where the active power fluctuation magnitude with voltage disturbance is more significantly than that of the active power disturbance, although the voltage disturbance is less than the active power disturbance.

Figure 6a,b, respectively, illustrate the comparison between reactive power disturbances and active power disturbances, as well as the comparison between grid voltage disturbances and active power disturbances. The focus of the study is the system’s active power. It is evident that the impact of reactive power disturbances on active power is smaller than those of grid voltage disturbances and active power disturbances. This observation can be further verified by the magnitude of the bode plot in Figure 6a,b.

In addition, it can be seen in Table 2 that the PM and GM of a voltage loop with a grid voltage disturbance are much better than those of an active power loop with an active disturbance. Nevertheless, the P fluctuation of the simulation results with a grid voltage disturbance is more significant than that with an active disturbance. It illustrates that the fluctuation propagation effect plays a more important role in the stability characteristics of active power, although the self-loop is stable. It further consolidates that the self-loop stability margin is not the sole condition to judge the stability of the system, which should consider the fluctuation propagation by the proposed FPM.

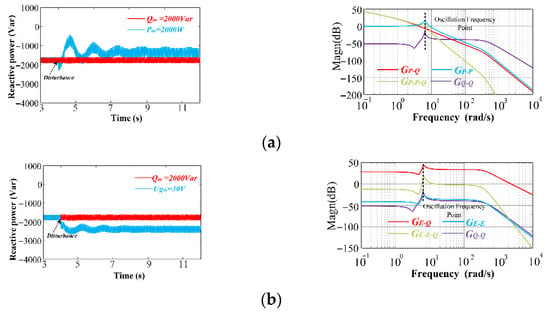

By comparing the resonance peaks (RPs) of different transfer functions with disturbances in Figure 6a,b, it can be seen that the RPs obey the inequality, i.e., |GE−E−P(s)| > |GP−P(s)| > |GQ−Q−P(s)|. It is inferred that the impacts of different disturbances on active power fluctuation obey the ranking, i.e., ΔUg > ΔPref > ΔQref. Similarly, is there an interesting approach that can be used to analyze the impact of different disturbances on the stability of Q? The answer is clearly affirmative. Through the same method, the impacts of different disturbances on the fluctuation propagation, as well as the reactive power dynamics’ stability, can be identified by the derived transfer functions, as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

The closed-loop transfer of active power (a) active disturbance, (b) frequency disturbance, (c) grid voltage disturbance. By the above closed-loop transfer functions, the impact of different disturbances on the fluctuation of Q can be analyzed.

Referring to Figure 7, GP−Q(s), Gf−Q(s), and GE−Q(s) are defined as the fluctuation propagation factors from P to Q, f to Q, and E to Q, respectively.

Similarly, GP−Q(s), Gf−Q(s), and GE−Q(s) are given by the following:

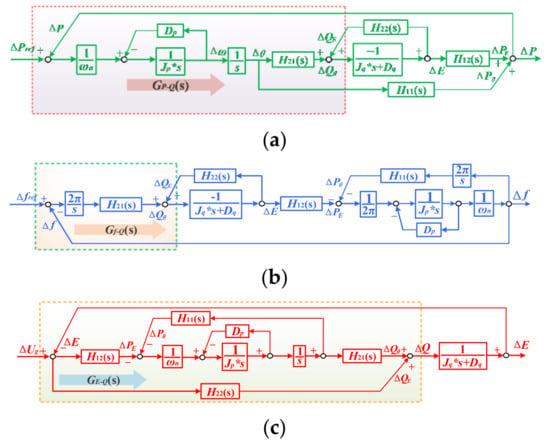

As illustrated by Figure 8, on the other hand, active power disturbances (with 2000 W) show a minimal impact on reactive power, resulting in unchanged oscillation dynamics at post-disturbance and pre-disturbance. In addition, the grid voltage disturbance (30 V) imposes slightly more significant impacts on the reactive power fluctuation than that of the reactive power disturbance.

Figure 8.

Waveform and bode diagram of Q under different disturbances. (a) active disturbance, (b) grid voltage disturbance. Table 3 presents a comparative analysis of the simulated and theoretical oscillation frequency points under various disturbance conditions at Lg = 13 mH. The data in the table indicate that the simulated oscillation frequency points closely align with the theoretical values, thereby verifying the accuracy of the model. Table 4 systematically summarizes the control parameters and circuit parameters of the system.

Table 3.

Oscillation frequency point table.

Table 3.

Oscillation frequency point table.

| Condition | Simulation | Theory |

|---|---|---|

| Active power disturbance | 0.92 Hz | 1.01 Hz |

| Reactive power disturbance | 1.00 Hz | 1.03 Hz |

| Grid voltage disturbance | 1.03 Hz | 1.08 Hz |

Table 4.

Control and circuit parameter.

Table 4.

Control and circuit parameter.

| Grid Voltage (Line to Line) | 380 V (RMS Value) |

|---|---|

| System nominal frequency | 50 Hz |

| L-filter inductance | 4.4 mH |

| L-filter resistance | 0.1 Ω |

| Grid inductance | 13 mH |

| Grid resistance | 4 Ω |

| Virtual inertia constant (Jp) | 1.5 |

| Virtual damping factor (Dp) | 10/2 |

| Virtual inertia constant (Jq) | 10 |

In the same way, to evaluate the impact of disturbances on Q, it is necessary to derive the closed-loop model which includes the fluctuation propagation model as well as the information of disturbance.

Furthermore, GP−P−Q(s) and GE−E−Q(s) are derived as follows:

where GP−P−Q(s) is the active power dynamics propagated to reactive power impacted by active disturbance, and GE−E−Q(s) depicts the voltage dynamics propagated to the reactive power impacted by grid voltage disturbance.

In Figure 8a, the Q fluctuation appears with active power disturbance, although Q is open-loop stable. This is because the fluctuation propagation from f to Q is significant, which can amplify the fluctuation magnitude of Q. It further illustrates that the open-loop system is not a sufficient condition for judging the stability, since the stability is also impacted by the fluctuation propagation of the model.

In Figure 8b, the grid voltage disturbance more significantly impacts the reactive power stability, since KE−E−Q > 0 > KQ−Q and also KE−Q > 0, which means that the propagation effect is positive and can amplify the fluctuation. The analysis results are well matched with the simulations in Figure 8.

To further judge the impact of different disturbances on reactive power fluctuation, the RPs obey the ranking, i.e., |GE−E−P(s)| > |GP−P(s)| > |GQ−Q−P(s)|. It is inferred that the impacts of different disturbances on reactive power fluctuation obey the ranking, i.e., ΔUg > ΔPref > ΔQref. It is inferred that, whether for active power or reactive power, the impact law of different disturbances is the same, which further consolidates the generality of the proposed modeling method.

3.3. Accuracy Verification of the Proposed Model

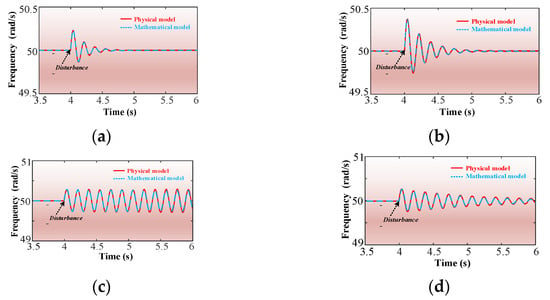

To further consolidate the accuracy of the model, both the physical model and the mathematical model of the studied system are developed. The mathematical model is derived based on an average small-signal model, but the physical model is built up based on a switching simulation model. It is seen that the two responses are well matched, as shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

The frequency curves of the mathematical model and the physical model (a–d) under different operating conditions.

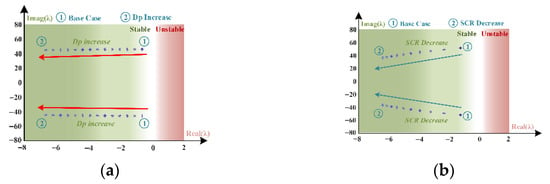

As illustrated in Figure 10a, condition ① represents the original operating state, while condition ② corresponds to a reduction in Dp. The green region denotes the stable operating domain of the system, whereas the red region signifies instability. As Dp increases, the system’s characteristic roots progressively shift toward the stable region, indicating an enhancement in the system stability. In the simulation, Dp functions as the system’s damping coefficient, where higher values correspond to an improved stability. Similarly, Figure 10b demonstrates that, as the (SCR), representing grid strength, decreases, the system’s stability improves. This finding suggests that the proposed system exhibits a superior stability performance under weak-grid conditions.

Figure 10.

Root locus: (a) varying Dp; (b) varying SCR.

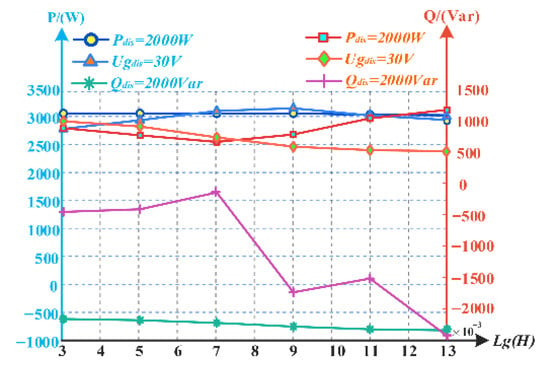

Figure 11 illustrates the oscillation amplitude in the first cycle under Pref, Qref, and Ug disturbances. The active power (left Y-axis) and reactive power (right Y-axis) under Pref, Qref, and Ug disturbances are presented, depicting the variations in oscillation amplitude with decreasing Lg.

Figure 11.

Power oscillation amplitude under different disturbances as Lg decreases, representing Pref, Qref, and Ug disturbances.

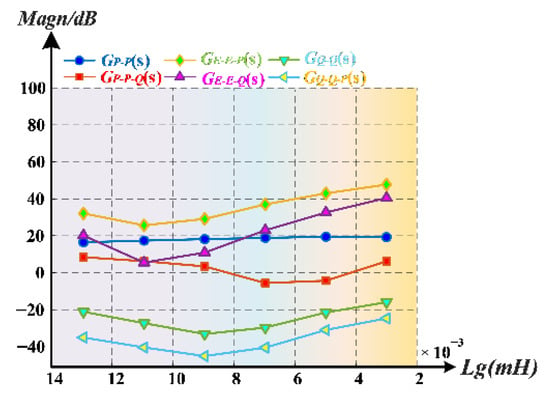

Figure 12 illustrates how the magnitude of the transfer function at oscillation frequency points varies with different disturbances as the grid-side inductance Lg decreases. A larger magnitude implies a stronger disturbance propagation and higher instability, while a smaller magnitude indicates a weaker propagation and enhanced system stability.

Figure 12.

Magnitude variation in different transfer functions at oscillation frequency points as Lg decreases.

Specifically, under the Qref disturbance in Figure 11, the oscillation amplitudes of both active power and reactive power in the first cycle increase progressively as Lg decreases. This phenomenon is theoretically validated in Figure 12, where the magnitudes of GQ−Q(s) and GQ−Q−P(s) at the oscillation frequency points exhibit an increasing trend with decreasing Lg, indicating that the enhanced disturbance propagation effect leads to more severe fluctuations in the output state variables.

Similarly, in Figure 11, as Lg decreases, P and Q exhibit divergent trends: the amplitude of P increases, whereas that of Q decreases. The analytical approach for the Pref and Ug disturbances follows the same methodology and is therefore omitted here for brevity.

4. Oscillation Propagation Analysis for Evsg Strategy

To demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed theory and model, the experiments are developed based on the topology and control strategy in Figure 2.

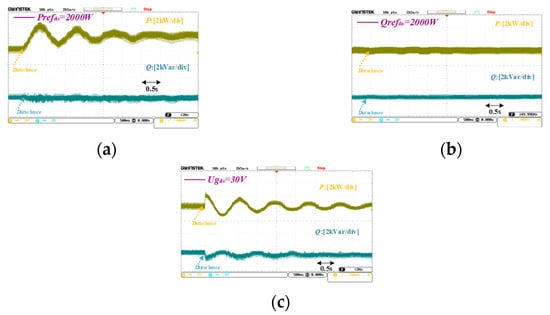

Figure 13 shows the experimental results, where the active power dynamics are displayed with the different types of disturbances, including grid frequency, grid voltage, reference input active power, and reference input reactive power. It is seen that the fluctuation magnitude of the three cases obeys the inequality, i.e., ΔUg > ΔPref > ΔQref, which aligns well with the theoretical analysis and confirms the effectiveness of the proposed modeling. Moreover, the results indicate that grid disturbances exert a greater influence on active power dynamics than power reference disturbances. This further supports the validity of the FPM.

Figure 13.

Experimental results: (a) active power reference disturbance; (b) reactive power reference disturbance; (c) grid voltage disturbance.

Also, the stability margin of the voltage loop is much better than that of the active power loop; the P fluctuation with grid voltage disturbance is larger than that of active disturbance. It shows that the fluctuation propagation effect plays the more important role in the stability characteristics of P instead of the self-loop.

Figure 13 presents the experimental results of the reactive power transient dynamics under disturbances from the active power reference, reactive power reference, and grid voltage. Specifically, Figure 13a shows the response under an active power reference disturbance, Figure 13b shows the response under a reactive power reference disturbance, and Figure 13c shows the response under a grid voltage disturbance. It can be observed that grid voltage disturbances cause larger fluctuations than power reference changes. These observations align well with the theoretical analysis and the fluctuation propagation model.

Figure 14 presents the semi-physical (hardware-in-the-loop) experimental platform has been built, mainly consisting of a host PC, a supervisory (upper-level) computer, an RCP (Rapid Control Prototyping) controller, an HIL (Hardware-in-the-Loop) circuit, I/O boards, and an oscilloscope. The experimental system was constructed according to the topology and control algorithm shown in Figure 1.

Figure 14.

Experimental platform.

5. Conclusions and Discussions

This work has proposed a new model which takes the impact of different disturbances into consideration to identify the power oscillation stability, where the fluctuation propagation model was established to judge the stability issues in cases where the disturbance is not the reference input of a single-input–single-output (SISO) system. The main conclusions are as follows:

The proposed model framework can be applied generally and can judge the power oscillation stability where the disturbance is not the reference input power but the grid voltage and grid frequency. It effectively counteracts the shortcoming of traditional closed-loop systems that cannot capture the stability characteristics, especially when other types of disturbances impose fluctuation propagation effects on the system.

In addition, a systematic investigation has been conducted to analyze the influence of different types of disturbances (Pref, Qref, and Ug) on the power oscillation propagation characteristics under varying (SCR) conditions.

The fluctuation model was established in the generic model to help judge the fluctuation propagation phenomenon in the grid-forming converter system. The proposed generic model can guide controller design and thus avoid undesirable instability phenomena as well as fluctuation propagation.

Author Contributions

Methodology Z.W.; Resources X.M. and W.D.; Writing–original draft K.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the ‘Research on Typical Power Supply Modes and Network Matching Technology for Rural Microgrids’ of the State Grid Anhui Electric Power Science and Technology Project (B3120524004F).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Kai Lv, Xun Mao, WangChao Dong and Zhen Wang were employed by the company State Grid Anhui Electric Power Research Institute. All authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Yang, Y.; Li, C.; Cheng, L.; Gao, X.; Xu, J.; Blaabjerg, F. A Generic Power Compensation Control for Grid Forming Virtual Synchronous Generator with Damping Correction Loop. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2023, 71, 10908–10918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Wang, Z.; Ma, Y.; Hu, J.; Zou, X.; Kang, Y. Hybrid LVRT Control of Doubly-Fed Variable Speed Pumped Storage to Shorten Crowbar Operational Duration. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2024, 39, 14192–14203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Chu, Y.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, D. Operation Strategy and Optimization Configuration of Hybrid Energy Storage System for Enhancing Cycle Life. J. Energy Storage 2024, 95, 112560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Yang, Y.; Blaabjerg, F. Mechanism Analysis for Oscillation Transferring in Grid-Forming Virtual Synchronous Generator Connected to Power Network. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2025, 72, 8715–8720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, G. Improved Adaptive Inertia Control of VSG for Low Frequency Oscillation Suppression. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Power Electronics and Application Conference and Exposition (PEAC), Shenzhen, China, 4–7 November 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Yang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Aleshina, A.; Xu, J.; Blaabjerg, F. Grid Inertia and Damping Support Enabled by Proposed Virtual Inductance Control for Grid-Forming Virtual Synchronous Generator. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2023, 38, 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alipoor, J.; Miura, Y.; Ise, T. Power System Stabilization Using Virtual Synchronous Generator with Alternating Moment of Inertia. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2015, 3, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Sun, Y.; Lin, J.; Chen, S.; Su, M. P/Q-ω/V Admittance Modeling and Oscillation Analysis for Multi-VSG Grid-Connected System. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2023, 38, 5849–5859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Wang, C.; Ma, R.; Li, W.; Cao, Y.; Chang, H.; Zhang, H.; Gao, Z. Quantitative analysis for coupling between frequency dynamic and power angle oscillation. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 4th International Conference on Power, Intelligent Computing and Systems (ICPICS), Shenyang, China, 29–31 July 2022; pp. 250–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Yang, Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Blaabjerg, F. Modeling for Oscillation Propagation with Frequency-Voltage Coupling Effect in Grid-Connected Virtual Synchronous Generator. EEE Trans. Power Electron. 2025, 40, 82–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, W.; Cao, Y. VSG-Based Extended State Observer and Feedback Damping Control for Low Frequency Oscillations. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 6th Conference on Energy Internet and Energy System Integration (EI2), Chengdu, China, 11–13 November 2022; pp. 520–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, Y.; Du, Y.; Gao, X.; Yang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Blaabjerg, F. Self-Stability and Induced-Stability Analysis for Frequency and Voltage in Grid-Forming VSG System with Generic Magnitude–Phase Model. IEEE Trans. Ind. Informatics 2024, 20, 12328–12338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Zhou, D.; Blaabjerg, F. Active Power Oscillation Damping Based on Acceleration Control in Paralleled Virtual Synchronous Generators System. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2021, 36, 9501–9510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Yan, Y.; Shen, Y.; Hu, Z. Active and Reactive Power Coupling Characteristics Based Inertial and Primary Frequency Control Strategy of Battery Energy Storage Station. In Proceedings of the 2020 12th IEEE PES Asia-Pacific Power and Energy Engineering Conference (APPEEC), Nanjing, China, 20–23 September 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Fang, J.; Tang, Y.; Debusschere, V. Coupling Effect of Active and Reactive Power Controls on Synchronous Stability of VSGs. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 4th International Future Energy Electronics Conference (IFEEC), Singapore, 25–28 November 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhou, W.; Bahrani, B. Cross-Coupling Effects of Voltage Control and Active Power Control on Small-Signal Stability of Virtual Synchronous Generator. In Proceedings of the 2023 11th International Conference on Power Electronics and ECCE Asia (ICPE 2023—ECCE Asia), Jeju Island, Republic of Korea, 22–25 May 2023; pp. 2486–2491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatziargyriou, N.; Milanovic, J.; Rahmann, C.; Ajjarapu, V.; Canizares, C.; Erlich, I.; Hill, D.; Hiskens, I.; Kamwa, I.; Pal, B.; et al. Definition and Classification of Power System Stability—Revisited & Extended. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2021, 36, 3271–3281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xu, N.; Shu, S.; Lei, W. Enhanced Power Decoupling Strategy for Virtual Synchronous Generator. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 73601–73613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Shen, X.; Tan, Y.; Tan, Z.; Lei, J. Interactive Power Oscillation and Its Suppression Strategy for VSG-DSG Paralleled System in Islanded Microgrid. Chin. J. Electr. Eng. 2022, 8, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Z.; Gong, X.; Liu, L.; Liu, L. Parameters Analysis and Operational Area Calculations of VSG Applied to Distribution Networks. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 2023, 9, 2214–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Sun, Y.; Li, L.; Liu, Z.; Han, H.; Su, M. Power Oscillation Suppression in Multi-VSG Grid by Adaptive Virtual Impedance Control. IEEE Syst. J. 2022, 16, 4744–4755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, T.F.D.; Salazar, A.O. Power Coupling Influence on Virtual Synchronous Generator Control in Grid-Forming DG Systems. In Proceedings of the 2023 15th Seminar on Power Electronics and Control (SEPOC), Santa Maria, Brazil, 22–25 October 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Yang, Y.; Mijatovic, N.; Dragicevic, T. Frequency Stability Assessment of Grid-Forming VSG in Framework of MPME with Feedforward Decoupling Control Strategy. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2022, 69, 6903–6913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Ma, Y.; Li, X.; Fan, L.; Tang, B.; Kang, Y. Transient Stability Analysis and Damping Enhanced Control of Grid-Forming Wind Turbines Considering Current Saturation Procedure. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2024, 40, 2496–2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, T.; Zhu, D.; Zou, X.; Jiang, B.; Peng, L.; Kang, Y. Power Coupling Mechanism Analysis and Improved Decoupling Control for Virtual Synchronous Generator. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2021, 36, 3028–3041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebinyu, E.; Abdel-Rahim, O.; Mansour, D.-E.A.; Shoyama, M.; Abdelkader, S.M. Grid-Forming Control: Advancements towards 100% Inverter-Based Grids—A Review. Energies 2023, 16, 7579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.