Abstract

Radiation-induced transient faults pose a growing challenge for safety-critical embedded systems, yet traditional radiation testing and large-scale statistical fault injection (SFI) remain costly and impractical during early design stages. This paper presents a predictive approach for early reliability assessment that replaces handcrafted feature engineering with automatically learned vector representations of source code and execution traces. We derive multiple embeddings for traces and source code, and use them as inputs to a family of regression models, including ensemble methods and linear baselines, to build predictive models for reliability. Experimental evaluation shows that embedding-based models outperform prior approaches, reducing the mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) from 6.24% to 2.14% for correct executions (unACE), from 20.95% to 10.40% for Hangs, and from 49.09% to 37.69% for silent data corruptions (SDC) after excluding benchmarks with SDC below 1%. These results show that source code and trace embeddings can serve as effective estimators for expensive fault injection campaigns, enabling early-stage reliability assessment in radiation-exposed embedded systems without requiring any manual feature engineering. This capability provides a practical foundation for supporting design-space exploration during early development phases.

1. Introduction

Transient faults induced by ionizing radiation, particularly single-event upsets (SEUs) that flip bits in memory elements, pose a recognized threat to the reliability of safety-critical embedded systems in spacecraft, automotive control units, and medical devices [1,2]. Depending on when and where a fault occurs, program execution may terminate correctly, produce an abnormal termination or an infinite loop (Crash/Hang), or silently produce incorrect data, known as silent data corruption (SDC). Therefore, quantifying the rates of these manifestations is indispensable for design-time decisions about protection mechanisms and cost–reliability trade-offs.

Statistical fault injection (SFI) is one of the most widely adopted techniques for assessing system dependability in the early design stages. In this approach, faults are introduced while the system is running so their effects can be observed. This enables engineers to estimate error rates and other reliability metrics [3]. Fault-injection methods are commonly categorized as either physical or logical [4].

Physical techniques, such as heavy-ion accelerators or pulsed-laser setups [5], create highly realistic radiation-induced faults. However, they are expensive, require specialized facilities, and cannot be applied until a final prototype is available. Postponing reliability analysis until silicon or final firmware is available makes design revisions costly and schedule-critical [3]. Therefore, logical techniques are attracting growing interest because they enable early, low-cost reliability exploration (even before hardware exists) by perturbing an abstraction of the system under test. Obtaining resilience estimates in the early stages of the system design allows for the rapid elimination of configurations with unacceptable fault tolerance, the allocation of protection only where statistically justified, and the focus of expensive physical tests on the most critical designs.

Logical fault injection employs two main strategies. Emulation-based injection maps the target design onto a field-programmable gate array (FPGA) or injects faults directly into a real device. This method provides cycle-accurate results in near-real time [6]. Moreover, simulation-based injection perturbs a software model of the system at the instruction set architecture (ISA), register transfer level (RTL), or mixed abstraction levels during execution [7,8]. Both strategies trade execution speed for modeling accuracy and observability, and allow the identification of the critical resources. However, the increasing complexity of the hardware and software stacks that support modern microprocessor architectures demands ever longer fault injection campaigns that involve thousands of simulations executing millions processor cycles. This fact is making fault injection a very computing demanding task even for lightweight ISA-equivalent simulators and virtual tools.

To overcome those problems model-based predictors try to compensate the lack of information about microarchitectural details in commercial processors by combining fault injection estimation with results obtained in radiation experiments [9,10,11]. They offer accurate and realistic estimations but at the cost of expensive tests. Recent research shows that machine learning (ML) techniques can complement or even replace exhaustive injection campaigns by predicting system vulnerability directly from a set of features. For example, ML models have forecasted application-level vulnerability for high-performance computing workloads using profiling information [12], estimated soft-error rates in multicore platforms by means of application and platform characteristics [13], and predicted functional-failure rates of complex circuits combining static features, like cell properties, circuit structure and synthesis attributes, as well as dynamic features, such as signal activity [14]. In addition, proPVInsiden [15] proposes a machine learning-based partial fault injection method that leverages instruction-level and error propagation features to predict program instruction vulnerability to silent data corruption with reduced fault injection overhead. More recently, the PARIS proposal [16] combined instruction categories, six resilience patterns, and a representation of instruction execution order to predict application resilience faster than fault injection and outperform analytical models.

While these studies confirm the potential of machine learning in this context, they rely on fixed, human-crafted features, such as counts, pattern flags, and loop depths, which may miss richer semantic information that can now be captured via representation learning. Modern vector representations can capture this information. They encode textual or structured data as numeric vectors, which facilitates their use in machine learning and natural language processing. These representations include count-based methods such as Bag-of-Words (BoW), Term Frequency–Inverse Document Frequency (TF-IDF), and n-grams, which capture the frequency-based characteristics of the data numerically. They also include semantic embeddings, such as word2vec and FastText, that map data into dense vector spaces while preserving contextual and structural relationships that go beyond mere occurrence statistics [17].

We propose a predictive workflow that replaces manual features with automatically learned embeddings derived from source code and dynamic execution traces. These vector representations are then combined with established regressors: Random Forest (RF), Histogram-based Gradient Boosting (HistGB), Gradient Boosting (GB), Support Vector Regression (SVR), Linear, Ridge, ElasticNet, Categorical Boosting (CatBoost) and Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost). This approach is independent of any specific ISA and requires only moderate fault injection effort for training. Our approach allows for broader applicability across different hardware architectures and makes it easier to integrate into existing design processes.

This work makes three specific contributions:

- 1.

- We propose an embedding-based approach for the early prediction of reliability-related metrics using source code and execution traces, avoiding manual feature engineering.

- 2.

- We systematically evaluate the impact of different code and trace representations, including lexical, word-based, and pretrained embeddings, combined with multiple machine learning models, on reliability prediction accuracy.

- 3.

- We conduct a detailed experimental comparison with PARIS on a common benchmark, providing analyses that highlight the strengths and limitations of the proposed approach.

By eliminating manual feature engineering and exploiting representation learning, the proposed pipeline clarifies the value of embeddings for the early reliability assessment of radiation-exposed embedded systems.

2. Background and Related Works

2.1. Statistical Fault Injection

We consider the single bit-flip fault model in this work. It describes a scenario in which a bit in a digital system changes its value unexpectedly (from 0 to 1 or vice versa) due to external disturbances, such as radiation-induced single-event upsets. This transient error can alter the system’s logical or operational state, potentially affecting its reliability and the correctness of its execution [1].

To establish the ground truth necessary to train our predictive fault-tolerance models, we conduct extensive fault injection campaigns using the SOFIA framework [18], which integrates ISA-level fault injection capabilities through the OVPsim (Open Virtual Platforms) simulator [19]. SOFIA enables efficient statistical fault injection at the instruction set architecture level, allowing for large-scale campaigns that would be impractical with cycle-accurate simulators or FPGA-based emulation. This approach provides the necessary fault injection data for early reliability assessment while maintaining reasonable simulation performance.

During these experiments, the program’s final execution result is used to classify the injected bit-flip faults according to the definitions in [20]. Specifically, faults that do not alter the correctness of the program output are labeled unnecessary for Architecturally Correct Execution (unACE). Faults that result in program completion with incorrect outputs are classified as SDC. Faults that cause an infinite loop or abnormal termination are classified as Hang. SDC and Hang are both classified as faults that compromise architectural correctness, as they adversely impact system reliability and correct program execution.

2.2. Related Works on Reliability Prediction with ML

Machine learning techniques have been proposed for assessing system vulnerability to radiation-induced faults, providing a promising alternative to fault injection campaigns. Various approaches have been suggested for different levels of the system stack, from application behavior to circuit-level characteristics.

At the application level, Oliveira et al. [12] proposed one of the earliest attempts to predict program vulnerability using ML. Their model, trained on profiling metrics such as instruction mix and memory access patterns, estimated the vulnerability of high-performance computing applications, reducing the need for fault injection. This approach demonstrated the feasibility of using runtime features to estimate fault susceptibility early on. Falco et al. [21] used a combination of features, extracted from the trace execution of set of applications, to train a feed forward neural network. The accuracy of the model is limited and only takes into account the fault tolerance of the microprocessor´s register file. Guo et al. built on this work with PARIS [16], a framework that incorporated a richer set of features, including instruction types, resilience, and execution patterns. By capturing interactions between instructions and common error-masking patterns, their model improved prediction accuracy while maintaining low computational overhead. It is important to note that all studies relied on domain-specific, handcrafted features tailored to application-level behaviors.

Recently, Ma et al. proposed SLOGAN [22], which represents the structural and dependency information of an application’s execution in the form of a graph and subsequently the probability of SDC is estimated by a regression model. However, it is unable to predict all three outcomes of errors. A different approach is presented by Wen et al. [23] which focuses on estimating the probability that an individual instruction may result in silent data corruption in the event of an error. The authors propose a Heterogeneous Program Knowledge Graph to capture the structural interdependencies between basic blocks and instructions, enabling the exploration of potential SDC propagation paths and the accurate prediction of vulnerable instructions within basic blocks.

Simulation-based predictions of the probability of SDC occurrence in high-performance applications have been studied by Gizopoulos et al. [24], who extract statistical metrics from the dynamic behavior of the code while exercising different hardware blocks of the processor. Their approach provides accurate estimations on heterogeneous devices, including not only microprocessors but also domain-specific accelerators. However, the method relies on micro-architectural-level fault injection [25], which entails a high computational cost compared to ML-based approaches

At the architectural level, da Rosa et al. [13] developed a model to estimate soft error rates in multicore platforms. They extracted a set of static and dynamic features, such as architectural counters and system-level properties, using virtual fault injection campaigns to train classical ML models. Their approach significantly reduced simulation effort; however, the quality of the predictions remained closely tied to the relevance and expressiveness of the selected features. Similar methodologies have been extended to other platforms, such as (General-Purpose Graphic Processing Units), where models rely on high-level metrics and manually selected descriptors to predict masking fault rates and classify the vulnerability level of the programs based on their SDC and Crash rates [26,27].

At the circuit level, Lange et al. [14] focused on predicting the functional failure rates of individual hardware components. Their methodology combined structural features (e.g., gate connectivity and logic depth) and dynamic metrics (e.g., signal activity) to characterize flip-flops. They trained regression models to estimate the likelihood of error propagation. While their results showed a high correlation between predicted and observed failure rates, the feature set was manually defined and tailored to a specific design context. A similar approach is followed by Shaoqi et al. [28] who employ Graph Neural Networks to capture both circuit topology and the temporal dynamics of signal propagation in complex circuits.

Instruction-level analysis has also been explored. Yang et al. introduced a hybrid strategy that uses instruction-specific attributes and error propagation indicators to estimate vulnerability to SDC [15]. Their work reduced the number of fault injections required by identifying patterns strongly associated with SDC; however, it still relied on predefined instruction properties and empirical thresholds to guide feature selection.

Despite promising results, most prior studies rely on fixed, manually engineered features such as instruction counts, loop depths, code resilience patterns, and architectural statistics, which may overlook the deeper semantic and contextual information available through modern representation learning techniques. Furthermore, there is a lack of comprehensive comparisons involving multiple representation types and machine learning models. Closing this gap is essential to better understanding the effectiveness of different combinations for early-stage reliability prediction in embedded systems.

2.3. Vector Representations in ML for Text and Code

Vector representations encode structured or textual data as numeric vectors, which facilitates their processing by machine learning algorithms and natural language processing techniques. These representations capture meaningful patterns and relationships within data, enabling effective analysis and prediction.

Count-based representations numerically encode textual data using frequency and co-occurrence statistics. Methods like Bag-of-Words, Term Frequency–Inverse Document Frequency, and n-grams rely on counting word occurrences or combinations, representing textual data based on statistical prominence [29].

Semantic embeddings, such as word2vec [17], FastText [30], and doc2vec [31], project words or documents into dense vector spaces where semantic and contextual relationships are preserved. These methods leverage neural network architectures to learn deeper contextual and semantic relationships that go beyond simple frequency-based features.

For source code representation, transformer-based models such as CodeBERT [32] and GraphCodeBERT [33] generate embeddings by capturing syntactic and semantic features of source code. Pre-trained on extensive code corpora, these models can effectively represent complex code structures for specific tasks, such as fault tolerance prediction.

3. Proposal

We propose a predictive workflow for the early-stage reliability assessment of embedded systems that are subject to radiation-induced transient faults. Our method integrates automatic feature extraction from source code and simulation traces via vector representations and supervised machine learning to estimate silent data corruption rates, hang rates, and functionally correct execution rates.

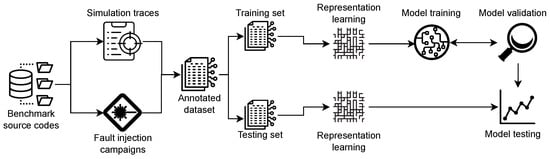

Figure 1 provides a detailed view of the proposed workflow. The process begins with the collection of two complementary inputs: (i) the source code of the benchmark programs and (ii) the simulation traces capturing their dynamic behavior during execution. These inputs are essential for characterizing the programs statically and dynamically.

Figure 1.

Overview of the proposed reliability prediction workflow based on representation learning and supervised regression.

Before any modeling occurs, the raw simulation traces are preprocessed to retain only the relevant information necessary for learning. This involves filtering instruction execution and register update events while discarding noninformative lines or fragments, such as simulator metadata and verbose constant strings. This cleaning step transforms the trace into a concise sequence of instructions and state changes, enabling consistent vectorization across benchmarks. To facilitate reproducibility, an illustrative example comparing a raw execution trace segment and its corresponding preprocessed representation is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Illustrative example of execution trace preprocessing.

Next, extensive fault injection campaign is conducted on the executable programs to simulate radiation-induced bit flips in both memory and microprocessor’s registers. This step generates an annotated dataset in which each entry corresponds to a benchmark program (source code and simulation trace) and is labeled according to the resulting behavior on the fault injection campaign (SDC, Hang, and unACE rates). The dataset is then partitioned into training and testing sets to enable fair model evaluation.

Representation learning is applied to both the source code and the execution traces to extract vector embeddings. For traces, count-based methods (BoW, TF-IDF, and n-grams) and semantic methods (word2vec, FastText, and doc2vec) are used, while transformer-based models (CodeBERT and GraphCodeBERT) are used for code. In the case of word2vec and FastText, which produce word-level embeddings, the final representation of a trace is obtained by averaging the vectors of its individual tokens. This aggregation ensures a fixed-length, document-level embedding suitable for regression tasks. We evaluate both individual representations (either from the code or the trace) and combined representations where features from both are concatenated into a unified vector. These representations serve as features for supervised learning. The pretrained language models (CodeBERT and GraphCodeBERT) are used strictly as frozen feature extractors, without fine-tuning. This decision isolates the effect of the representation itself and ensures comparability across heterogeneous embedding families, avoiding additional variability introduced by task-specific adaptation.

In the next stage, we train machine learning models using cross-validation on the training data. Nine regressors are used to estimate the expected rates of fault injection campaigns: Random Forest, HistGB, Gradient Boosting, SVR, Linear, Ridge, ElasticNet, CatBoost and XGBoost. Cross-validation permits robust hyperparameter tuning and prevents overfitting by evaluating model performance across multiple folds. After identifying the optimal configuration, we test the final model on the held-out test set to evaluate its generalization ability.

Model performance is evaluated using four standard regression metrics: Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE), and the coefficient of determination (R2). MAE provides a scale-dependent measure of average error, while RMSE penalizes larger errors more heavily, offering sensitivity to outliers. MAPE normalizes the error by the target value, making it suitable for comparisons across varying scales; however, it is highly sensitive when the true value is near zero, as highlighted for the case of the SDC prediction in prior works such as [16]. The R2 metric quantifies the proportion of variance in the target variable that is predictable from the input features, serving as an overall indicator of model fit. Reporting all four metrics enables a comprehensive and balanced evaluation of regression performance.

To address the instability of directly predicting SDC, especially when true values are close to zero, we train separate regression models for unACE and Hang rates. The SDC rate is then computed by subtracting these predicted values from 100%. When this leads to negative SDC values, we apply normalization to ensure all three rates are non-negative and sum to 100%.

This pipeline is designed to support systematic, reproducible, and comparative analyses. By combining different representations and models, we aim to identify effective strategies for early reliability prediction.

4. Experimental Evaluation

4.1. Benchmark

The experimental evaluation relies on two distinct application sets: a training set used to fit the regression models, and a held-out test set reserved for final evaluation and comparison with prior work.

The training set comprises 64 C-language programs drawn from algorithmic problem collections, mainly solutions to competitive programming challenges on the HackerRank platform [34]. These programs cover common categories such as greedy optimization, dynamic programming, graph algorithms, combinatorics, and string processing. Representative examples include AngryChildrens, SherlockAndPairs, MatrixChainOrder, and FloydCycleDetection. Each program is a self-contained single-file implementation with deterministic behavior, which makes it suitable for trace-based analysis and exposes the models to varied code structures during training.

The test set consists of 14 applications derived from the PARIS benchmark suite [16], drawn from established collections such as NAS, Rodinia, PARSEC, Parboil, SPEC, and CORAL. This selection directly matches the PARIS evaluation set, enabling a fair comparison of prediction accuracy against prior work. To enable efficient large-scale fault injection simulations, the original PARIS workloads were adapted into lightweight sequential C versions that preserve core algorithmic behavior while significantly reducing input sizes and removing external dependencies.

For both training and test applications, parallel implementations (OpenMP/pthread) were converted to sequential code, input data was embedded directly into the source to eliminate file I/O, and problem sizes were reduced to achieve tractable trace lengths. Even with these reductions—ranging from 90% to over 98% in problem size depending on the application—essential computational patterns are preserved, thereby enabling thousands of fault injections per workload. All applications were compiled with the -O0 optimization flag and used deterministic initialization for golden executions.

4.2. Fault Injection Campaigns

Fault injection campaigns were conducted using the SOFIA framework [18] to simulate radiation-induced single-event upsets through single-bit flips in the processor state. These experiments targeted a bare-metal ARM Cortex-A9 processor model for 32-bit execution, thus providing a realistic representation of embedded system behavior without operating system interference.

The benchmark suite exhibits a wide range of execution characteristics, with execution times ranging from 30 ms to 171 s (average: 3.6 s). This diversity reflects the varied computational patterns present in embedded system workloads and ensures that the predictive models are evaluated across different execution profiles.

For each application, a golden run was first performed to capture an error-free execution trace and record the program’s dynamic behavior. Bit-flips were then injected selectively into architectural state elements, including general-purpose registers and memory regions actively used by the program. This approach focuses on program-relevant state, reducing unnecessary injections and aligning with the selective targeting philosophy used in related works like PARIS. To achieve robust statistical coverage 7700 faults were injected per benchmark, targeting both the register file and the memory sections, for a total of around 0.5 M of faults injected. Given the significant variance in execution times described above, we employed a dynamic timeout threshold defined as 3× the golden run execution time for each specific benchmark. This approach ensures that hang conditions are reliably detected while avoiding the premature termination of longer-running applications. In all cases, the injection volume was sufficient to achieve an error margin of 1% with a confidence level of 99%.

4.3. Experimental Setup

To evaluate the effectiveness of machine learning models we conducted a series of regression experiments aimed at predicting the percentage of Hangs and unACE observed in fault injection campaigns.

Each experiment involved training regression models using different vector representations of execution traces and source code. Table 2 summarizes the configurations considered in our study. For each representation-regressor combination, grid search and 5-fold cross-validation were applied to tune hyperparameters. We then evaluated the selected configuration on a held-out test set.

Table 2.

Input representations and regressors used in the experiments.

We evaluated individual input representations derived from either the execution trace or the source code, as well as composite representations constructed by concatenating the trace and code embeddings. This design enabled us to determine if combining static (code) and dynamic (trace) information enhances predictive performance. Additionally, we systematically compared the performance of different regression models across all representation types to identify the most robust modeling strategies.

As mentioned above, SDC was estimated from the percentages of Hang and unACE predicted by the regression models. From these predictions, the expected percentage of silent data corruptions was computed using Equation (1).

Predictions yielding negative values for were set to zero. In cases where the sum of and exceeded one, a normalization step was applied to preserve probabilistic consistency.

We used a single version per application in the benchmark, following standard practice. Specifically, we selected binaries that were compiled without optimization flags (-O0). These versions offer better traceability and preserve the original structure of the source code, facilitating the interpretability of results.

Additionally, for each test sample, we compute the relative error between the predicted values () produced by the regression model and the actual values (y) of each target variable observed during fault injection (Equation (2)). This per-sample relative error highlights how close each prediction is in proportion to the actual outcome, which is especially useful for identifying outliers and analyzing model robustness.

We identified and reported extreme cases with large relative errors, which often correspond to benchmarks with low ground truth values (e.g., near-zero SDC). Following the reporting practice used in PARIS [16], these cases are highlighted separately because they may distort the aggregate metrics and suggest limitations in the model’s ability to predict fault outcomes.

5. Experimental Results

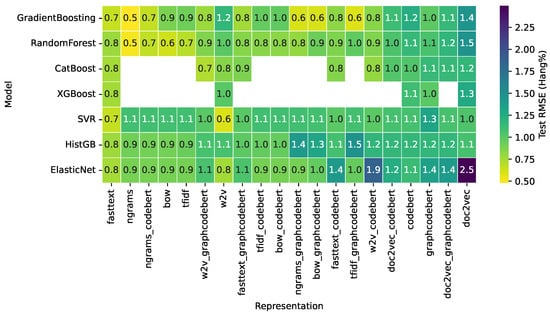

Figure 2 summarizes the test RMSE obtained by the non-linear models across all code representations for the prediction of Hang percentage. Linear models (Ridge and Linear Regression) were excluded from the visualization because, in several high-dimensional representations such as TF-IDF and n-grams, they produced numerically unstable solutions with extremely large errors (RMSE > 60), a behavior consistent with known sensitivity of linear estimators to multicollinearity and feature sparsity. Their inclusion would therefore distort the color scale and hinder meaningful visual comparison.

Figure 2.

Heatmap of test RMSE for Hang prediction.

The remaining models show a consistent pattern. The visible range of RMSE spans from 0.5 to 2.5, with most combinations lying between 0.7 and 1.3. Gradient Boosting and Random Forest achieve some of the lowest errors (around 0.5–0.8) for representations such as FastText and n-grams, while Support Vector Regression attains similarly competitive values, especially with dense embeddings like word2vec (RMSE ≈ 0.6–0.7). CatBoost and XGBoost, available for a subset of representations, also remain in the 0.8–1.0 range; missing entries correspond to configurations that were not executed due to model-specific constraints or training failures under certain sparse or high-dimensional feature sets. ElasticNet shows moderate performance for many embeddings but its error increases substantially for certain Doc2Vec-based variants (up to RMSE = 2.5).

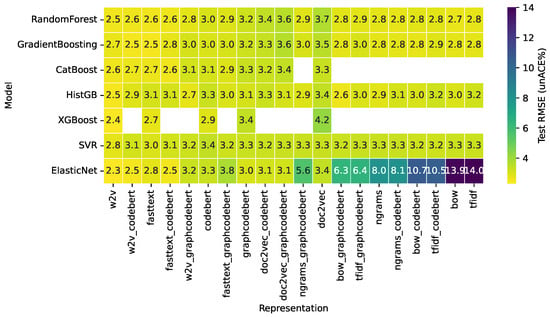

Figure 3 shows the distribution of test RMSE values for the prediction of percentage of unACE across non-linear models and code representations. Unlike the Hang results, where model choice played a more pronounced role, the unACE prediction exhibits a relatively uniform error profile: most models and representations fall within a narrow RMSE band of approximately 2.5–3.4. Tree-based ensembles (Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, HistGB, CatBoost, and XGBoost) behave similarly across embeddings, suggesting that unACE is less sensitive to the particular inductive bias of each model. SVR remains competitive but shows slightly higher variability. The main divergences correspond to ElasticNet, whose errors increase sharply under sparse, high-dimensional representations (notably TF-IDF and BoW).

Figure 3.

Heatmap of test RMSE for unACE prediction.

Taken together, the two heatmaps highlight that the difficulty and model sensitivity of the prediction task vary across targets: while Hang prediction reveals marked differences between models and representations, unACE prediction displays a more homogeneous error landscape, allowing for a more stable performance across non-linear estimators.

Table 3 summarizes the 10 best-performing model–representation combinations for each prediction target, ranked by test RMSE. To improve readability, the table reports only the top configurations per target (Hang and unACE) and includes all key test metrics (RMSE, MAE, R2, and MAPE). The embeddings are shown using compact notation, and representations involving multiple components (e.g., BoW + GraphCodeBERT) are abbreviated consistently. This table provides a consolidated view of the most competitive models for each reliability indicator, highlighting how different embeddings interact with various learning algorithms to yield high predictive accuracy.

Table 3.

Top-10 model–representation combinations per target.

For Hang percentage, the best results cluster around tree-based ensemble methods, particularly Gradient Boosting, which appears repeatedly among the top entries. Representations based on token n-grams yield the lowest RMSE values (≈0.48–0.60), suggesting that local lexical and syntactic patterns in the code capture structural cues associated with hang-prone behavior. Dense distributed embeddings such as word2vec and FastText also perform well when paired with SVR or Gradient Boosting, indicating that both granular token patterns and semantic embeddings can be informative for this target. The corresponding R2 values, ranging from 0.58 to 0.78, show that a substantial proportion of the variance in hang behavior can be explained when appropriate models and representations are used. Hang prediction benefits from models capable of capturing non-linear relationships, with ensembles offering the most stable advantage across representations.

For unACE, the top-performing entries span a more diverse set of models, including ElasticNet, XGBoost, Gradient Boosting, and HistGB, all achieving RMSE values in the 2.3–2.6 range. In contrast with Hang, the unACE target exhibits much smaller differences between algorithms, suggesting a smoother error landscape and lower sensitivity to model choice. Notably, word2vec-based embeddings dominate the top positions, both alone and in combination with codeBERT, highlighting the robustness of semantic embeddings for predicting unACE. Sparse high-dimensional representations appear less beneficial for this target, as none of the best configurations involve TF-IDF or n-grams. This reinforces that, for unACE, broader semantic characteristics rather than detailed lexical patterns drive predictability, and that the underlying model is intrinsically less dependent on fine-grained structural information. However, the corresponding R2 values, in the 0.38–0.50 range, indicate that only a moderate portion of the variance in unACE behavior can be explained by the available trace/code representations.

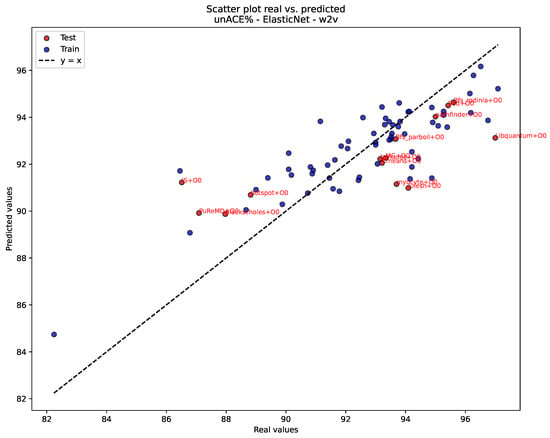

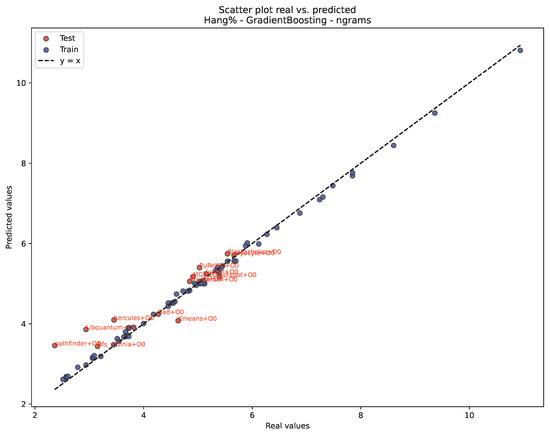

Figure 4 and Figure 5 illustrate the predictive performance of the best-ranked model– representation combinations for each target using scatter plots of real versus predicted values. For unACE, Figure 4 (ElasticNet with word2vec embedding) shows a tight clustering of points around the identity line, with both training and test samples following a nearly linear trend, indicating stable generalization and confirming the low RMSE and moderate R2 observed for this configuration (see Table 3). For Hang, Figure 5 (Gradient Boosting with n-grams) reveals an even closer alignment with the line, particularly for the test set, reflecting the higher explanatory power achieved for this target with non-linear ensemble methods and fine-grained token representations. Together, these figures provide a visual complement to the quantitative metrics reported earlier, showing how the selected models capture the underlying structure of each reliability indicator.

Figure 4.

Real vs. Predicted values for unACE percentage using ElasticNet and w2v.

Figure 5.

Real vs. Predicted values for Hang percentage using Gradient Boosting and n-grams.

Table 4 reports the prediction performance in the test dataset obtained with the best models identified for each target: ElasticNet with word2vec embeddings for unACE, Gradient Boosting with n-grams for Hang, and the combined unACE–Hang formulation for estimating SDC via Equation (1). The table organizes real values (ground truth obtained by fault injection), predicted values, and relative errors for each fault category under both our proposal and PARIS [16], allowing a direct, workload-level comparison across the two approaches. A crucial methodological detail is the exclusion of outlier benchmarks from the MAPE computation. In particular, since SDC rates can fall below 1% for several benchmarks (i.e., Libquantum, Sad, Lulesh, and Myocyte), relative percentage errors become numerically unstable, and small absolute deviations can yield errors of several hundred percent. Because MAPE is not robust under such conditions, these extreme cases were excluded to ensure that aggregate SDC accuracy reflects only statistically meaningful predictions. The table therefore presents complete benchmark-level results, while the reported MAPE values incorporate this treatment of outliers.

Table 4.

Prediction results using the best models in this work for (a) unACE, (b) Hang, and (c) SDC in the test dataset, with comparison to PARIS [16] results.

The results in Table 4 show that our proposal consistently outperforms PARIS across the three fault categories, with the strongest advantage observed for unACE. The average unACE error in our approach is substantially lower than that of PARIS (2.14% for all benchmarks vs. 6.24% without two outliers), reflecting the benefit of semantic embeddings for capturing the dominant behavior in successful executions. For Hang rate prediction, Gradient Boosting with n-grams captures fine-grained structural features more effectively than PARIS, yielding lower relative errors in the majority of benchmarks and a substantially reduced MAPE (10.40% for all benchmarks vs. 20.95% without one outlier).

The SDC comparison is especially informative: once outliers are removed—those benchmarks where the real SDC is less than 1% and percentage-based error metrics become unreliable—our method achieves an MAPE of 37.69%, outperforming the 49.09% reported for PARIS. This represents a relative improvement of 23.2%, indicating that our approach explains a larger fraction of the variability in SDC manifestations despite relying solely on code and trace representations rather than the feature engineering analysis employed by PARIS. Collectively, these results demonstrate that embedding-based regression models constitute a competitive and computationally efficient alternative to state-of-the-art early reliability assessment methods.

6. Discussion

The results obtained across the prediction of the three fault categories reveal several insights into the strengths and limitations of learning-based prediction using code and trace embeddings/representations, as well as the conditions under which specific representations or model classes perform best. Overall, the findings show that embedding-based regression constitutes a competitive alternative to handcrafted feature engineering, with notable advantages in predictive stability, scalability, and applicability during early design stages of embedded systems.

A primary strength of the proposed models is their ability to capture non-linear relationships between automatically learned code and trace embeddings and fault manifestation rates, without manual feature engineering. For unACE and Hang, the best-performing pipelines exhibit low relative errors across most benchmarks and outperform PARIS in aggregate evaluations (Table 4). Ensemble methods such as Gradient Boosting and Random Forests consistently yield robust results, particularly when paired with high-quality token representations.

The main weakness appears in the prediction of extremely low ground-truth SDC rates (typically below 1%), where percentage-based errors amplify small deviations when ground-truth values approach zero. As a result, relative error measures such as MAPE become numerically unstable and may provide a distorted view of model performance in this regime. For this reason, SDC outliers associated with near-zero ground-truth values were excluded from the MAPE computation, as reported in Table 4. While the exclusion of these outliers produces a stable and interpretable MAPE, the difficulty of predicting SDC reliably at extremely small scales highlights an inherent limitation of both our method and prior approaches such as PARIS.

In addition, Table 4 (c) highlights the Bfs_parboil benchmark as a case where PARIS achieves zero relative SDC error, whereas the proposed approach exhibits a higher relative deviation. A closer inspection reveals that this difference corresponds to a small absolute error: the ground-truth SDC rate is 1.48, while the proposed model predicts 1.87. Although the absolute discrepancy is limited, expressing this difference as a relative error yields a value of 26.22%. This example illustrates how relative error metrics can overemphasize modest absolute deviations when the target value is low, even if it is not close to zero. Consequently, while PARIS attains an exact prediction in this specific case, the observed relative error of the proposed approach should be interpreted in light of its small absolute magnitude. This observation complements the broader discussion on the limitations of relative error measures for low-SDC benchmarks and helps delineate the practical significance of such discrepancies.

From a modeling perspective, low-SDC benchmarks represent a particularly challenging scenario, as fault injections result in correct or benign outcomes, leaving very few samples that contribute meaningful SDC information. This strong imbalance amplifies noise and limits the learnable signal for regression models. Potential improvement directions include the use of evaluation metrics more robust to near-zero targets, alternative formulations of SDC prediction based on reliability regimes rather than continuous percentages, or the integration of additional contextual features to better capture rare SDC-prone behaviors. These directions are left for future work.

The divergence observed in Figure 2 and Figure 3 can be explained by the different types of information captured by the evaluated representations. Hang faults are commonly associated with control-flow disruptions, such as repeated instruction patterns, stalled branches, or tight execution loops. For instance, token n-gram representations explicitly encode short instruction sequences, making them particularly effective at capturing the local execution patterns that precede hang conditions. When combined with non-linear models such as Gradient Boosting, these representations can model complex interactions between local patterns that may lead to hang behavior (see Figure 5). In contrast, unACE reflects the overall likelihood of correct execution, which depends on broader semantic and behavioral characteristics of the program. Distributed word embeddings such as word2vec capture global semantic similarity across trace regions and execution contexts, allowing them to represent higher-level execution behavior rather than isolated local patterns. In this context, linear regularized models such as ElasticNet are sufficient to exploit these dense representations, resulting in stable and accurate unACE predictions (see Figure 4). These findings indicate that different fault categories are best addressed by representations that capture information at different levels of granularity, and that the effectiveness of a given representation–model pairing depends on the nature of the reliability metric being predicted. Table 5 summarizes the relationship between embedding families, the type of fault-related semantics they capture, and their observed prediction behavior for unACE and Hang, as discussed below.

Table 5.

Summary of the relationship between embedding type, captured fault semantics, and observed prediction behavior for unACE and Hang.

The experiments show that individual representations can offer strong performance when their inductive biases align with the target fault category. Distributed embeddings such as word2vec and fastText excel for unACE, where broad semantic similarity between trace regions is predictive of correct execution. By contrast, token n-grams outperform all other embeddings for Hang, indicating that short-range lexical patterns, often reflective of control-flow and branching structures, are more informative for predicting interrupt-type faults. Doc2Vec-based variants were less consistently competitive in our experiments, and for Hang they can become model-sensitive.

Composite embeddings, those combining trace representations with code embeddings, tend to provide small but consistent gains when models can exploit their complementary information, particularly for Hang. However, their advantage diminishes for unACE, where excess feature dimensionality offers limited benefit beyond what dense semantic vectors already provide.

The connection between embedding type and metric-level outcomes suggests that different fault categories encode distinct semantic and structural signatures. Dense embeddings yield low MAPE for unACE because they capture global semantic similarity across trace regions. Structural embeddings (ngrams, TF-IDF + BoW) achieve higher R2 and lower RMSE for Hang, reflecting that local syntactic patterns are more predictive of whether control flow will be perturbed.

The comparison with PARIS highlights a key methodological insight: automatically learned code and trace embeddings provide richer, more generalizable abstractions of program behavior than manually engineered features. While PARIS relies on domain-specific features derived from binary instruction profiling and propagation rules, embeddings capture high-dimensional relationships that are not constrained by manually defined heuristics. This allows the learning algorithms to discover latent code properties associated with fault outcomes, including those not explicitly modeled in traditional architectures. The empirical advantage observed in unACE and Hang predictions, and the improved SDC MAPE after removing outliers, demonstrate that embedding-based models can exceed prior state-of-the-art accuracy with substantially lower feature-extraction complexity.

In addition to predictive accuracy, we characterized the computational cost of the proposed approach across two distinct phases: offline training and online inference. Training is performed offline once per model configuration and exhibits moderate execution times ranging from tens to hundreds of seconds, depending on embedding dimensionality, dataset size, and regressor complexity. Since training is amortized across multiple evaluations and design iterations, this one-time cost does not constitute a limiting factor for practical deployment.

Inference, which determines the method’s viability for early-stage design exploration, comprises three sequential stages. Firstly, trace generation from architectural simulation which ranges from milliseconds (for compact benchmarks) to hundreds of seconds (for complex applications), depending on program execution length. Secondly, embedding extraction consistently remains in the order of milliseconds across all representation types (sparse count-based, distributed semantic, and pretrained code models). Finally, the model inference requires only milliseconds for the entire test set, corresponding to sub-millisecond cost per individual sample. Critically, inference overhead remains stable across different embedding families and does not scale with embedding dimensionality, as the trained regressor operates on fixed-size representations. Compared to statistical fault injection campaigns, which require thousands of simulation runs over hours to days, our approach achieves speedups exceeding three orders of magnitude (>1000×) for reliability assessment of a single benchmark. These results confirm that the proposed method can be seamlessly integrated into early-stages design workflows, where rapid evaluation of multiple benchmarks or design alternatives is required without incurring significant computational overhead.

Because the proposed models rely solely on code embeddings and trace representations, together with model regressors, they can be integrated early in the design flow, before hardware characterization or full radiation testing is available. This offers practical advantages: designers can obtain rapid estimates of reliability trends across benchmarks, enabling early-stage prioritization of mitigation strategies, benchmarking of alternative implementations, and preliminary risk assessment for safety-critical scenarios. The ability to evaluate dozens of kernels rapidly also facilitates design-space exploration and architectural prototyping, tasks that would be prohibitively expensive using fault-injection-driven or radiation testing approaches alone.

This work contributes a systematic evaluation of code and trace embeddings for predicting multiple radiation-induced fault categories in embedded systems, demonstrating that machine learning pipelines can outperform specialized feature-engineered models. The study also clarifies the connection between embedding choice and predictive performance across fault categories, offering actionable guidance for selecting representations depending on the target metric. Finally, by showing that such models can yield accurate predictions with minimal computational overhead, this work advances the feasibility of embedding-based reliability assessment as a practical tool in early design stages, complementing traditional simulation and testing workflows.

7. Limitations and Validity Concerns

For baseline comparison and construct validity, we ensured fair evaluation by using the applications and data from the official PARIS GitHub repository and replicating their methodology exactly as described in the original publication. We maintained consistency in fault injection procedures (the same fault model, injection targets, and outcome classification), evaluation metrics, experimental conditions (same test applications where possible), and preprocessing steps. This careful replication enables meaningful comparisons and strengthens the validity of our superiority claims. The choice of evaluation metrics also warrants discussion. We evaluated model performance using MAE, RMSE, MAPE, and R2, which are standard regression metrics that capture different aspects of prediction quality. However, MAPE can be numerically unstable when true values approach zero, particularly for SDC rates in applications with very low vulnerability. We addressed this by explicitly identifying and excluding outliers from aggregate MAPE calculations and reporting this exclusion transparently. This practice aligns with the approach used in prior works and ensures that aggregate statistics reflect meaningful prediction performance rather than artifacts of near-zero denominators.

A primary limitation of our approach concerns the single-fault assumption underlying our fault injection methodology. Following established practice in the reliability research community (e.g., [12,13,15,16,22]) we model soft errors as single-bit flips in processor computational elements. This widely adopted fault model not only reflects the dominant error mechanism in current systems but also enables direct comparison and validation of our results against prior work, facilitating reproducibility and cumulative progress in the field. While this model accurately represents individual particle strikes and single-event upsets, it may not adequately capture reliability behavior where multiple-bit upsets (MBUs) are present, as can occur in advanced technology nodes. Our model has not been validated under such conditions, and the prediction accuracy in multi-fault scenarios remains unknown.

Another significant limitation is the absence of fault-tolerance mechanisms in our evaluation. Our model is trained exclusively on unprotected code without any software-implemented hardware fault tolerance techniques. These mitigation techniques fundamentally alter error propagation patterns, instruction execution flows, and data dependencies, all of which are captured in our approach. The interaction between embedding-based predictions and these protection schemes requires further investigation.

Dataset representativeness poses another validity concern. Our training dataset consists of 64 C-language programs primarily drawn from competitive programming platforms (HackerRank), while our test set comprises 14 scientific applications from established benchmark suites. Although these applications cover diverse computational patterns including greedy optimization, dynamic programming, graph algorithms, numerical methods, and scientific computations, they may not fully represent the complete spectrum of embedded systems applications encountered in practice. The generalizability of embedding-based predictions to specialized domains such as space, automotive, avionics, or medical applications remains to be established.

Compiler optimization levels introduce an additional validity concern. All applications in our evaluation were compiled with the -O0 optimization flag to preserve the original code structure and improve traceability between source code and executable binary. However, production embedded systems typically use higher optimization levels (-O2, -O3, or even profile-guided optimization) to meet performance and code size constraints. Compiler optimizations substantially alter code structure through transformations such as instruction scheduling, register allocation, loop unrolling, function inlining, dead code elimination, and common subexpression elimination. These transformations can fundamentally change instruction sequences, and data dependencies captured by our embeddings. Moreover, optimizations may introduce or remove error propagation paths: for example, constant propagation might eliminate instructions that could be fault injection targets, while loop unrolling might replicate vulnerable code segments. The impact of compiler optimizations on the accuracy of embedding-based predictions remains an open question. A potential mitigation strategy would involve augmenting the training dataset with multiple optimization variants of each benchmark, enabling the model to learn optimization-invariant features.

Finally, our work does not include an explicit sensitivity or interpretability analysis of pretrained embeddings such as CodeBERT or GraphCodeBERT. While interpretable baselines using sparse representations and linear models are provided, understanding which embedding dimensions or code patterns contribute most to unACE, Hang, or SDC predictions is left for future work. Although the use of embeddings simplifies the modeling pipeline, the learned representations remain opaque, and additional work is required to fully interpret which latent code and trace patterns drive fault behavior.

Despite these limitations, our approach advances the state of the art in early-stage reliability prediction by eliminating manual feature engineering, demonstrating superior accuracy compared to existing methods, and providing a practical foundation for design-space exploration during early development phases. The identified limitations primarily affect the scope of applicability rather than invalidating the core contribution within the evaluated domain. Several directions could address these limitations in future work, as discussed in the next section.

8. Conclusions and Future Works

This paper presented a predictive workflow for the early reliability assessment of embedded systems exposed to radiation-induced transient faults. The proposed approach replaces handcrafted feature engineering with automatically learned embeddings derived from source code and execution traces, which are then used as inputs to supervised regression models. By jointly exploiting static (code) and dynamic (trace) information, the workflow estimates the percentages of unACE, Hangs, and SDC with moderate computational cost and without making assumptions about the underlying instruction set architecture.

The experimental evaluation on a benchmark suite derived from the PARIS dataset shows that the combination of word2vec embeddings with ElasticNet provides the best trade-off for unACE prediction, while Gradient Boosting using token n-grams attains the lowest error for Hang prediction. When SDC is inferred from the predicted unACE and Hang rates, the resulting model achieves an MAPE of 37.69% after excluding benchmarks with SDC below 1%, compared with 49.09% for PARIS, i.e., a relative improvement of 23.2%. For unACE and Hang, the proposed models also reduce MAPE from 6.24% to 2.14% and from 20.95% to 10.40%, respectively, while maintaining competitive RMSE and R2 values. These results indicate that code and trace embedding-based models can outperform state-of-the-art feature-engineering approaches for early reliability prediction.

Several directions emerge for future work. The first step is to expand the evaluation to additional processor architectures, optimization levels, and benchmark suites, in order to assess how well the proposed models generalize across different microarchitectural features and software workloads. For instance, we plan a synthetic data augmentation strategy based on the generation of multiple versions of each benchmark by applying different compiler optimization options during compilation. These variants might introduce structural differences at the binary and trace levels while preserving the programs’ functional correctness. This approach augments the dataset without introducing semantic noise and permits to evaluate the models’ robustness to structural diversity. The second line is to integrate explicit software-based fault-tolerance techniques and to predict metrics such as the mean work to failure (MWTF) instead of only unACE, Hang, and SDC rates, enabling the models to learn patterns associated with hardened workloads and to support design-space exploration of mitigation techniques. Another promising avenue is to investigate richer representation learning strategies for execution traces, such as transformer-based or graph-structured embeddings that capture temporal and data-flow dependencies more explicitly. Finally, integrating the proposed models into early-stage design flows and electronic design automation tools, where they can act as fast surrogates for extensive fault-injection campaigns, could turn embedding-based reliability prediction into a practical aid for architects and designers of safety-critical embedded systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.R.-C. and E.A.R.; methodology, F.R.-C.; software, F.R.-C.; validation, E.A.R. and S.C.-A.; formal analysis, F.R.-C.; investigation, E.A.R.; resources, E.A.R. and F.R.-C.; data curation, E.A.R.; writing—original draft preparation, F.R.-C.; writing—review and editing, F.R.-C., E.A.R. and S.C.-A.; visualization, F.R.-C.; supervision, S.C.-A.; project administration, S.C.-A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Grant PID2022-138696OB-C22 funded by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by the European Union. The APC was funded by the same grant.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to the large size of the fault injection simulation datasets and execution traces.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Baumann, R. Radiation-induced soft errors in advanced semiconductor technologies. IEEE Trans. Device Mater. Reliab. 2005, 5, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solouki, M.A.; Angizi, S.; Violante, M. Dependability in Embedded Systems: A Survey of Fault Tolerance Methods and Software-Based Mitigation Techniques. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 180939–180967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natella, R.; Cotroneo, D.; Madeira, H.S. Assessing Dependability with Software Fault Injection: A Survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2016, 48, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooli, M.; Di Natale, G. A survey on simulation-based fault injection tools for complex systems. In Proceedings of the 2014 9th IEEE International Conference on Design & Technology of Integrated Systems in Nanoscale Era (DTIS), Santorini, Greece, 6–8 May 2014; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, H.M.; Black, D.A.; Robinson, W.H.; Buchner, S.P. Fault Simulation and Emulation Tools to Augment Radiation-Hardness Assurance Testing. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2013, 60, 2119–2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entrena, L.; Garcia-Valderas, M.; Fernandez-Cardenal, R.; Lindoso, A.; Portela, M.; Lopez-Ongil, C. Soft Error Sensitivity Evaluation of Microprocessors by Multilevel Emulation-Based Fault Injection. IEEE Trans. Comput. 2012, 61, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Duan, G. On the characterization and optimization of system-level vulnerability for instruction caches in embedded processors. Microprocess. Microsyst. 2015, 39, 686–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohseni, Z.; Reviriego, P. Reliability characterization and activity analysis of lowRISC internal modules against single event upsets using fault injection and RTL simulation. Microprocess. Microsyst. 2019, 71, 102871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velazco, R.; Faure, F. Error Rate Prediction of Digital Architectures: Test Methodology and Tools. In Radiation Effects on Embedded Systems; Velazco, R., Foulliat, P., Reis, R., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 233–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyneri, L.M.; Serrano-Cases, A.; Morilla, Y.; Cuenca-Asensi, S.; Martínez-Álvarez, A. A Compact Model to Evaluate the Effects of High Level C++ Code Hardening in Radiation Environments. Electronics 2019, 8, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noizette, L.; Miller, F.; Helen, Y.; Leveugle, R. Early Assessment of the Fault Tolerance of Complex Digital Components From Virtual Platform Based Profiling. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2025, 72, 2717–2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, D.; Moreira, F.B.; Rech, P.; Navaux, P. Predicting the Reliability Behavior of HPC Applications. In Proceedings of the 2018 30th International Symposium on Computer Architecture and High Performance Computing (SBAC-PAD), Lyon, France, 24–27 September 2018; pp. 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Rosa, F.R.; Garibotti, R.; Ost, L.; Reis, R. Using Machine Learning Techniques to Evaluate Multicore Soft Error Reliability. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2019, 66, 2151–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, T.; Balakrishnan, A.; Glorieux, M.; Alexandrescu, D.; Sterpone, L. Machine Learning to Tackle the Challenges of Transient and Soft Errors in Complex Circuits. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 25th International Symposium on On-Line Testing and Robust System Design (IOLTS), Rhodes Island, Greece, 1–3 July 2019; pp. 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Wang, Y. Predicting the Silent Data Corruption Vulnerability of Instructions in Programs. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 25th International Conference on Parallel and Distributed Systems (ICPADS), Tianjin, China, 4–6 December 2019; pp. 862–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Li, D.; Laguna, I. PARIS: Predicting application resilience using machine learning. J. Parallel Distrib. Comput. 2021, 152, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikolov, T.; Chen, K.; Corrado, G.S.; Dean, J. Efficient Estimation of Word Representations in Vector Space. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), Scottsdale, AZ, USA, 2–4 May 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gava, J.; Bandeira, V.; Rosa, F.; Garibotti, R.; Reis, R.; Ost, L. SOFIA: An automated framework for early soft error assessment, identification, and mitigation. J. Syst. Archit. 2022, 131, 102710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Synopsys, Inc. Open Virtual Platforms. Available online: https://github.com/OVPworld/Information (accessed on 20 December 2025).

- Mukherjee, S.; Weaver, C.; Emer, J.; Reinhardt, S.; Austin, T. Measuring architectural vulnerability factors. IEEE Micro 2003, 23, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcó, D.R.; Serrano-Cases, A.; Martinez-Alvarez, A.; Cuenca-Asensi, S. Soft error reliability predictor based on a Deep Feedforward Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Latin-American Test Symposium (LATS), Maceio, Brazil, 30 March–2 April 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Huang, S.; Duan, Z.; Tang, L.; Wang, L. SLOGAN: SDC Probability Estimation Using Structured Graph Attention Network. In Proceedings of the 28th Asia and South Pacific Design Automation Conference (ASPDAC), Tokyo, Japan, 16–19 January 2023; pp. 296–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, B.; Gu, J.; Shen, D.; Zhou, Q.; Zhuang, F.; Liu, Y.; Song, H.; Huang, X. Efficient Instruction Vulnerability Prediction With Heterogeneous SDC Propagation Knowledge Graph. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 2026, 23, 117–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gizopoulos, D.; Papadimitriou, G.; Chatzopoulos, O.; Karystinos, N.; Dixit, H.D.; Sankar, S. Silent Data Corruptions in Computing Systems: Early Predictions and Large-Scale Measurements. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE European Test Symposium (ETS), The Hague, The Netherlands, 20–24 May 2024; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzopoulos, O.; Papadimitriou, G.; Karakostas, V.; Gizopoulos, D. Gem5-MARVEL: Microarchitecture-Level Resilience Analysis of Heterogeneous SoC Architectures. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Symposium on High-Performance Computer Architecture (HPCA), Edinburgh, UK, 2–6 March 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topçu, B.; Öz, I. Predicting the Soft Error Vulnerability of GPGPU Applications. In Proceedings of the 2022 30th Euromicro International Conference on Parallel, Distributed and Network-based Processing (PDP), Valladolid, Spain, 9–11 March 2022; pp. 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.H.; Di, S.; Guo, S.; Lu, X.; Li, G.; Cappello, F. Druto: Upper-Bounding Silent Data Corruption Vulnerability in GPU Applications. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Parallel and Distributed Processing Symposium (IPDPS), San Francisco, CA, USA, 27–31 May 2024; pp. 582–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Wang, S.; Kai, H.; Higami, Y.; Ma, R.; Ni, T.; Wen, X.; Takahashi, H. A Spatio-Temporal Graph Neural Networks Approach for Predicting Silent Data Corruption inducing Circuit-Level Faults. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2509.06289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salton, G.; Buckley, C. Term-weighting approaches in automatic text retrieval. Inf. Process. Manag. 1988, 24, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojanowski, P.; Grave, E.; Joulin, A.; Mikolov, T. Enriching Word Vectors with Subword Information. Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 2017, 5, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, Q.; Mikolov, T. Distributed Representations of Sentences and Documents. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Machine Learning (PMLR), Beijing, China, 21–26 June 2014; Volume 32, pp. 1188–1196. Available online: https://proceedings.mlr.press/v32/le14.html (accessed on 14 January 2026).

- Feng, Z.; Guo, D.; Tang, D.; Duan, N.; Feng, X.; Gong, M.; Shou, L.; Qin, B.; Liu, T.; Jiang, D.; et al. CodeBERT: A Pre-Trained Model for Programming and Natural Languages. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2020, Online, 16–20 November 2020; pp. 1536–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Ren, S.; Lu, S.; Zhou, L.; Svyatkovskiy, A.; Blanco, A.; Clement, C.; Drain, D.; Jiang, D.; Zhou, M.; et al. GraphCodeBERT: Pre-training Code Representations with Data Flow. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), Vienna, Austria, 4 May 2021; Available online: https://openreview.net/forum?id=jLoC4ez43PZ (accessed on 14 January 2026).

- Moise, W. HackerRank Solutions: C Language Benchmarks; Commit: E7e95b3. 2015. Available online: https://github.com/wesnerm/Contests/tree/e7e95b39142c5cf247bfb65813b3116fb6438701/HackerRank (accessed on 14 January 2026).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.