Abstract

Digital technologies have been widely adopted in the Cultural Heritage sector over the past few decades. Many museums, galleries, historic sites, and other cultural institutions now host multimedia exhibitions or temporary installations in which technology plays a significant role in shaping the visitor experience. Among these, Extended Reality (XR) technologies, including Virtual Reality (VR) and Augmented Reality (AR), have been extensively applied and studied. Spatial Augmented Reality (SAR), a branch of AR, has also become increasingly present in cultural contexts; however, the academic literature still lacks a comprehensive and systematic review of studies addressing its use. Furthermore, various methods of inquiry and evaluation have been employed to assess SAR applications in cultural institutions, both from the perspective of visitors and from that of cultural practitioners and stakeholders. This scoping review, conducted in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines, collected a total of 47 papers that introduce the academic perspectives on SAR in the cultural domain. It reports its definitions, applications, documented benefits, and the different evaluation approaches identified in the literature. Through a snowball sampling methodology, the collection has been expanded to include 33 additional studies. After the screening process, the authors reviewed 34 papers, presenting the gaps identified in the literature and outlining suggested directions for future research.

1. Introduction

Numerous studies highlight the widespread presence of digital technologies in the cultural domain: within museum exhibitions, in temporary installations in galleries, in events hosted in historical public palaces, and other cultural occasions, these technologies now shape the visitor experience across diverse cultural environments [1,2,3]. Digital technologies are applied both as a medium and as a support for heritage communication, as well as an enhancement of the overall visitor experience of heritage [4,5,6,7]. Among them, Extended Reality (XR) technologies, such as Virtual Reality (VR) and Augmented Reality (AR), have gained increasing attention in the domain [8,9]. An ever-growing number of museums and cultural institutions now host installations experienced through mobile AR applications, content delivered via VR headsets, and similar systems, offering visitors more immersive and engaging forms of interaction and facilitating their connection with cultural values [10]. Spatial Augmented Reality (SAR) is among these technologies and is becoming increasingly widespread in the cultural domain, where it is employed to support both the enjoyment and the divulgation of cultural heritage [11,12].

SAR is a projection-based form of AR that integrates digital content directly onto tangible objects, surfaces, and spaces in the real world. The term Spatial Augmented Reality was first introduced in 1998 as the augmentation of a user’s physical space through the use of a video projector [8]. In the literature, SAR is referred to using a variety of terminologies, including “projection-based AR”, “video projections”, “projection mapping”, “video mapping”, “architectural projection” and “spatial AR”, with the choice of terms typically depending on the intended use and contextual scope of the technology [2,11,13,14,15,16,17,18,19].

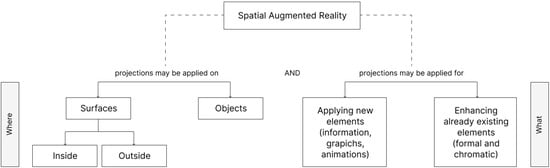

The presence of more terms to refer to the same technology reflects the heterogeneity of uses and contexts of application of SAR. Conceptually, the technology involves enriching human sensory perception by adding or subtracting information, enabling concrete reality to be experienced in a fundamentally different way [11]. This effect is mostly achieved using video projectors [18]. However, the way these projectors are used to achieve different purposes may vary, depending on several factors. Figure 1 presents a schematic representation of the various applications of SAR identified in the analyzed literature.

Figure 1.

Various uses of SAR identified in the analyzed literature.

The authors will use the term Spatial Augmented Reality as a general concept to describe the technology in all its observed heterogeneous applications and to underline its connection to the ontology domain of Extended Realities.

Despite the growing number of studies on SAR, the literature still lacks a comprehensive understanding of its implications and effects within the cultural sector. As already introduced, the coexistence of multiple terminologies used to describe the technology reflects this conceptual ambiguity and suggests the need for a clearer examination of how SAR is employed across different cultural environments.

This review has been conceived as an initial step toward a broader investigation of the perspectives of visitors, cultural stakeholders, and practitioners regarding the use of SAR technology in the museum context. To guide this exploratory stage, the authors conducted the review by formulating the following overarching research questions:

- What is the landscape of SAR in the cultural heritage field?

- What are SAR benefits in the museum context?

- What are the methods and tools used to evaluate SAR in cultural experiences?

The aim of this review is to present the state of the art regarding the definitions, advantages, limitations, and applications of SAR technology in the cultural realm as reported in the existing literature, and to examine the evaluation methods and tools employed by researchers to measure the effects of this technology on museum visitors and cultural stakeholders, as well as their perspectives on it. Through this scoping review, the authors provide a comprehensive understanding of the current state of SAR technology in the cultural domain and of the evaluation methods used to assess various museum users’ perspectives on it. The review also identifies gaps and outlines future directions to be explored for a deeper understanding of this digital technology application in the sector.

2. Materials and Methods

The scoping review was initially conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) reporting guidelines [20], to ensure a traceable process and accurate reporting structure. Peer-reviewed research articles on SAR technology in the cultural sector were collected in October 2025 from international electronic databases, including Scopus and Web of Science (WoS). A range of keywords with a Boolean logic was applied to improve coverage and minimize the omission of relevant articles. To investigate the use of SAR in the cultural sector, with a specific focus on museum applications, the search strategy included terms such as “SAR”, “Spatial Augmented Reality”, “Projection Mapping”, “Video Mapping”, and “Projection”, reflecting the most recurring terminologies used to indicate the technology. These were combined with keywords such as “Museum”, “Cultural Heritage”, “Exhibition”, and “Visitor Experience” to ensure coverage of the relevant cultural context. Open-access English articles from the last two decades were considered, excluding those falling in non-coherent areas of interest such as Physics, Medicine, Mathematics, and others (Table 1). Duplicates between the two databases were canceled.

Table 1.

Extended version of the search queries formulated for the two research databases.

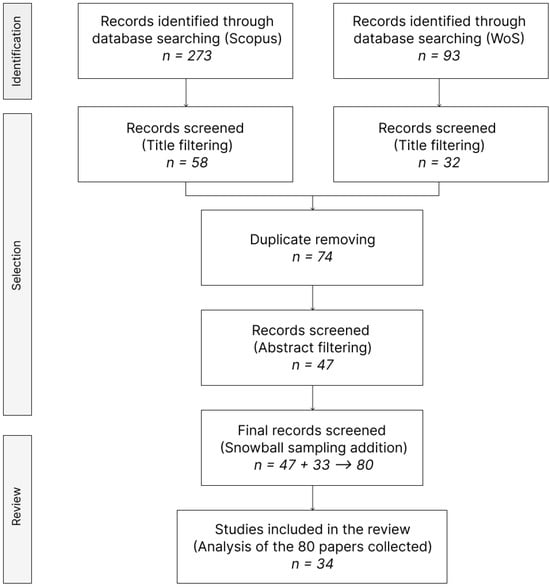

The collected articles were subsequently reduced by excluding those not relevant to the research, through an initial screening of titles followed by an abstract-based filtering process. This screening process was carried out by a single researcher who reviewed the titles and subsequently the abstracts of the retrieved papers to assess their relevance to the scope of the scoping review. Studies were included if they addressed at least one of the following criteria: (i) the cultural heritage field, with specific reference to the use of SAR technology; (ii) the description or application of SAR in exhibitions or installations; and (iii) the analysis of visitors’ experiences in cultural contexts involving SAR or XR technological interventions. Once the systematic selection phase was concluded, the collection was organized in a Zotero library and thematically analyzed [21]. While deepening the articles and identifying emerging themes relevant to the research, additional studies were incorporated through a snowball sampling approach whenever they were deemed pertinent to the scope of the review, following the same approach previously used for inclusion and exclusion criteria. All articles were analyzed to provide a comprehensive overview of the research topic, with the aim of addressing the initial research questions and, where this was not possible, identifying gaps in the existing literature. The overall review activity process is described in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Scoping review flow diagram.

3. Results

The initial search across online databases yielded 366 research articles. Following the screening process already described, 47 papers were selected, with an additional 33 studies incorporated through the snowball sampling method. After the analysis, 46 papers did not provide information relevant to the research context, resulting in a total of 34 papers considered for the review (Figure 2).

From a qualitative thematic analysis, research categories of interest identified are SAR definitions, SAR benefits, SAR in museums, and Visitor Experience evaluation methods. Table 2 shows the identified articles of interest related to the themes identified for each study. These categories have been identified to address initial research questions, focusing on the panorama of SAR in the cultural heritage sector, with a particular emphasis on museums and their stakeholders and visitors.

Table 2.

List of the articles related to the themes identified for the review (chronological order).

3.1. Spatial Augmented Reality

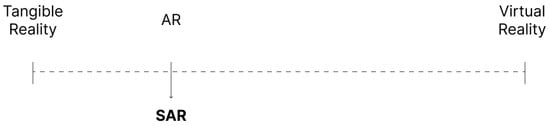

Spatial Augmented Reality can therefore be defined as a technology belonging to the broader category of augmented reality, with reference to the virtuality continuum proposed by Milgram and Kishino [36] (Figure 3). Using projectors, digital elements are superimposed onto tangible objects and surfaces, thereby augmenting physical reality with virtual information.

Figure 3.

Re-adaption of Milgram and Kishino’s Virtual Continuum with SAR technology.

The landscape of Spatial Augmented Reality technology is heterogeneous, encompassing a wide range of applications and contexts. As already outlined in the introduction, SAR has been adopted across multiple domains, from cultural heritage to entertainment and beyond, and is characterized by diverse modes of application as well as by a multiplicity of terminologies used to refer to the technology in both academic literature and practitioner practice.

Terminologies referring to this form of augmented reality vary according to the application object, the context of use, and the preferences of the scholars or practitioners addressing the topic. Within the literature analyzed in this review, the terms “Spatial Augmented Reality”, “Video Mapping”, and “Projection Mapping” are most commonly used, particularly in relation to cultural heritage applications. Older studies adopted technically oriented expressions such as “projection-based AR” or “spatial AR”. When technology itself is not the primary focus of the study, more general terms such as “projection” or “projections” are often employed. In more context-specific cases, the term may change, as for example when involving projections on building façades: in this case, qualifiers such as ‘architectural’ or ‘building’ are used to further specify the application. The different terminologies encountered in the selected review papers are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Different terminologies encountered in the review’s selected papers (chronological order).

SAR is inserted in the conceptual context of AR: this technology utilizes projections to render augmented images over tangible-world spatial items, such as objects and surfaces [28]. For Manzanares et al. [15], the ability of SAR to alter the appearance of an object has made its applications increasingly common. The interest in the low-cost and high-availability characteristics of its devices has been present since the early 2000s, as reported by Bimber and Raskar [35]. Nowadays, SAR is widely recognized worldwide [13] due to several technological qualities. For example, spatial AR does not rely on wearable displays or goggles, unlike see-through AR, and is consequently more suitable for experiences designed to be shared simultaneously by multiple users [17] or for situations where the devices need to be hidden from the audience [16].

Nofal et al. [17] identify several purposes for the applications of this technology, ranging from commercial to artistic, cultural, social, political and educational scopes [19]. Kryvuts et al. [2] highlight, from an artistic perspective, the informative, emotionally entertaining, semiotic, translational, and aesthetic purposes of the technology, contributing to the augmentation of both personal and collective cultural spaces. It is a technology that stunningly engages the audience: the perception of reality may significantly change when living this enhancement of sensory perception [14]. SAR has been applied to various realms, spanning from the entertainment industry to the educational sector. As highlighted in literature, this technology offers several advantages that make it particularly well-suited to the cultural domain.

3.2. Benefits of SAR in Museums

SAR has been extensively used for cultural applications in museum settings [13]. As underlined by Farré Torras et al. [26], museum design must nowadays provide additional layers of meaning and context through visual novelty, while also involving visitors in interpretive and contemplative activities. Aside from the preservation, restoration, and research activities carried out by cultural institutions, when focusing on exhibition and dissemination practices, SAR technology appears to offer significant advantages in enhancing visitors’ experience of the cultural values presented within the museum context [3]. Museums are reported to be considerably favored by the use of SAR, revealing a new style of engaging museum audiences in the deeper sense-making of the exhibited content [5]. Moreover, the introduction of these technologies is recognized as a decisive element for museums to attract audiences [7,27,33].

He et al. [32] identified two main purposes that emerge when introducing AR technology into the cultural heritage exhibition sector: (i) augmenting digital assets about the exhibits and (ii) augmenting immersive scenes. SAR technology may serve both scopes. Most installations involving SAR present digital augmentation and exploration of exhibits that work with tangible objects and surfaces [5]. SAR technology applied to physical assets can be used to highlight specific details, alter their aesthetic appearance, or even display them in their natural context [31]. Other types of museum displays that utilize projection mapping techniques include scale models of historic cities, landscapes, and buildings. Spatial applications, commonly referred to as architectural or building mapping, are widely used and can be implemented on both indoor and outdoor surfaces, highlighting specific details, altering their appearance, and displaying information, among other uses [5]. Through the incorporation of such innovative technologies, museums can offer more immersive and engaging forms of interaction, facilitating visitors’ connection with history and culture [10].

As a communication medium, SAR possesses specific qualities that make it particularly effective for conveying heritage information [17]. These qualities have been highlighted in the literature, from specific applicative cases reported in the studies or from reviews conducted by scholars. In museums, SAR enables the enhancement of knowledge about the exhibited object, promoting an immediate approach to acquiring information and fostering cultural and historical learning. SAR can serve as a medium to link historical facts and locations by valorizing monuments and narrating their stories through images and sounds [11]. Introducing such technologies in the museum context enables storytelling to be adopted as a communication technique that can impact the educational, touristic, and economic spheres [11]. By incorporating these innovative technologies, museums can provide visitors with a more immersive and engaging experience, facilitating the acquisition and transmission of information [22,30] and stimulating a diversification of behaviors in front of the exhibition [25]. These categories of benefits are deepened in the following sub-sections.

3.2.1. Enriching Visitors’ Engagement

In the design phase of a digital set for a theatrical performance, De Luca et al. [14] chose to work with SAR, affirming that through animated projections on surfaces, it becomes possible to foster greater audience engagement with the surrounding space in which they are situated. On the one hand, De Paolis et al. [11] report that projecting content onto the artwork’s surface helps ensure the viewer’s emotional engagement. Additionally, from a cognitive perspective, this technology is reported by Barbiani et al. [30] to be effective in conveying cultural information to visitors during their use of SAR on a small-scale reproduction of a building. SAR is recognized as a technology capable of maintaining high levels of user stimulation, as analyzed by Nikolakopoulou et al. [5] in their user evaluation of an interactive projection mapping installation for the Mastic Museum on the island of Chios, Greece. When designing an interactive cultural experience for the church of Roncesvalles at the beginning of Camino de Santiago, Olaz et al. [10] report that SAR enhances engagement with the exhibition and enriches the overall cultural experience. This is also confirmed by Shi et al. [3] in their evaluation of visitors’ experiences with the 3D mapping architectural projections at The Night of Museums in the Tsinghua University Museum. In their analysis of curatorial roles in the post-digital era, Farrè Torras et al. [26] suggest that SAR is a technology that transforms the possibilities for audience interaction, participation, and learning, stimulating sense-making, engaging conversations, and playful engagement between visitors; thereby, SAR positively influences visitors’ behavioral engagement, as underlined by Tzortzi et al. [25] in the evaluation of a digital architectural experience in the Tower of the Winds in the Agora of Athens, Greece.

3.2.2. Narrative Potential

The introduction of digital and interactive technologies in museums has provoked a shift from the traditional “collection” museum narrative to the “storytelling and connection” one [11]; in this context, Kryvuts et al. [2] define SAR technology as a significant communication medium, potentially enriching storytelling of exhibitions, as reported by Nikolakopoulou et al. [5] in their installation. The potential of this technology’s storytelling is also reported by Nofal et al. [17], who analyzed the participants’ interaction with their interactive installation inside the Graethem chapel in the small town of Borgloon, Belgium; this is confirmed as well by Tzortzi et al. [25] in their users’ experience evaluation. The superimposition of several digital elements, also intangible, presents various content, ranging from historical to cultural and mythical [17]. SAR easily may connect intangible and tangible elements of the exhibitions: according to what Tzortzi et al. [25], Nikolakopoulou et al. [5], Nofal et al. [17], and De Paolis et al. [11] observed in their installations’ visitors, this characteristic of SAR enhances cultural learning and enjoyment of artifacts and buildings, valorizing the cultural content and its narration through images and sounds. This narrative potential is recognized in the various cultural applications of SAR, on objects and surfaces [5,25], as well as in spatial or performative contexts, as reported by Whang and Huang in their magic performance [23].

3.2.3. Attracting Technology

Mine et al. [16], working in the field of entertainment parks, and Kryvuts et al. [2] in their study, present SAR as a technology of interest to both designers, curators, and organizers. Nikolakopoulou et al. [5] also affirm its attractiveness to visitors in museums, based on their research and evaluation of the installation. Yang and Huang [7] emphasize its importance in attracting new visitors to the museum, especially the younger generation, who would likely be uninvolved without stimuli like this technological one. This involves reconfiguring the interaction between exhibitions and visitors, with the exhibition no longer playing a mere auxiliary role in conveying cultural content. Farré Torras et al. [26] report this work of reconfiguration in their study.

3.2.4. Multiple Users

In literature, one major advantage of SAR technology reported is that it facilitates the concurrent participation of multiple users in a shared and sensory-enriched visual space [5,15]. De Luca et al. [14], from their “Includiamoci” social project, and Ridel et al. [18], in their “Revealing Flashlight” experiment, reported the exciting collective experience and stimulating collaborative behavior that the content projected elicited among visitors. This is a significant advantage in contexts that host several visitors a day; in contrast, device-based AR techniques, such as head-mounted displays or handheld mobile devices, do not scale as well, as affirmed by Mine et al. [16], who are strongly aware of this due to the high number of visitors inside theme parks. A similar situation may occur in museums or cultural institutions, where multiple visitors may share the same experience simultaneously.

3.2.5. Hidden Technology

Another advantage of SAR compared to handheld AR devices is that it allows visitors to experience the cultural content without the mediation of a device that could potentially distract their attention from the exhibition’s purpose, as underlined by several studies on field experimentation such as the ones from De Paolis et al., De Luca et al., Tzortzi et al., and the study from Gómez Manzanares [11,14,15,25]. Projection systems are recognized as less obtrusive and more flexible, and can support the creation of various effects without the need to wear any glasses or hold any device; this effect is also appreciated in works such as the one from Ridel et al., where the projected elements on surfaces and objects are guided by a device [18], integrating the virtual information seamlessly. The strong storytelling potential of the technology enables it to connect past and present, audience and exhibition, as well as cultural information and tangible elements.

3.2.6. Heritage Mediator

The communicative characteristics of SAR positively influence its role as a cultural heritage mediator in museum exhibitions. Georgescu Paquin argues for the transcending mediation that projection mapping can enable, adding a message to various content—whether artistic, exploratory, or explanatory [5]. By projecting digital elements on it, SAR creates optimal conditions for visitors to grasp the historical significance, social meaning, and cultural connotations of the artworks [27]. Shi et al. stress in their study the importance of contextualizing the cultural exhibition, establishing meaningful connections between the audience and the content of the exhibition [3].

3.2.7. Versatility

SAR technology presents different layers of versatility in its applications. De Paolis et al. [11] highlight its applicability in various fields, including artistic and cultural events, marketing and advertising, as well as education. Moreover, SAR can be applied to any surface or object, transforming them into dynamic elements that enrich sensory perception [14,35]. The relatively less motion of projections, technically speaking, also permits experiencing less latency with handheld AR devices, as reported by Mine et al. [16], referring to the theme park field. Finally, SAR reports flexibility in displacing immersive content: while most XR technologies focus on a selected stage within the mixed reality continuum [36], through projections, it is possible to transition seamlessly between different amounts of virtual content, as Schmidt et al. [31] experienced in their floor-based user interface that allows users to interact with both monoscopic and stereoscopic projections, thus guarantying always the vantage of hiding the devices and not interfering with users’ cognitive and emotional engagement flow.

3.3. Visitor Experience Evaluation Methods

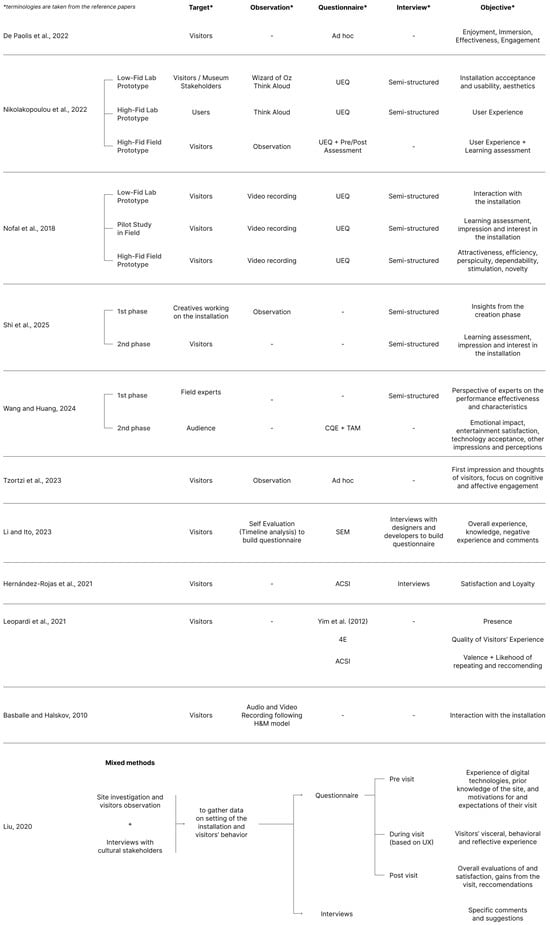

Several evaluation methods have been applied in the literature to estimate visitors’ experiences with cultural content disseminated through SAR (Figure 4).

In the animation of the pictorial cycle by Nicolò Maria Signorile, located inside the Cathedral of Maria Santissima della Madia in Monopoli, Italy, De Paolis et al. [11] distributed a questionnaire to a sample of users, asking them to assess the quality of the experience and suggest improvements. The questionnaire consisted of eighteen questions, using a seven-point Likert scale and an open-ended question, to investigate enjoyment, immersion, narrative effectiveness, and user engagement.

Nikolakopoulou et al. [5] designed, developed, and tested a SAR installation for the Mastic Museum on Chios Island in Greece, with projections on a scale reproduction of the historic settlement. To evaluate their installation, they first tested a low-fidelity prototype with museum stakeholders and visitors. Before the experience, users were provided with a brief introduction, and they were encouraged to share their thoughts aloud while interacting with the system (using the think-aloud protocol). During the evaluation, the system interaction was observed using the ‘Wizard of Oz’ method, generating the system’s responses to the user’s actions without the user knowing that there was someone behind the scenes. Moreover, researchers took notes during the users’ experience and then conducted semi-structured interviews, providing them with a final User Evaluation Questionnaire (UEQ) [37]. This evaluation has also been repeated for a high-fidelity prototype with users in a lab setting and, finally, in the museum with visitors who were also provided with a questionnaire to assess the learning effect of the installation.

Nofal et al. [17] investigated the effects of an installation with projections inside the medieval Graethem chapel in Borgloon, Belgium. To evaluate visitors’ responses, they video-recorded all the interactions with the system, considering the level of user engagement as derived by the duration of their interaction, their focus of attention while interacting, and their social interactions with other persons nearby. Then, researchers performed semi-structured interviews to assess visitors’ information gained and impressions of the installation. Finally, a standardized UEQ was spread to visitors.

Shi et al. [3] analyzed the visitors’ experience of “The Night of Museum”, an architectural projection featured in the inaugural exhibition of Tsinghua University Art Museum, by conducting observation activities and in-depth interviews with visitors, as well as recording meetings and semi-structured interviews with the creatives involved.

For the audience evaluation of a magic show performance, Wang and Huang [23] conducted technical interviews with field experts regarding the show and its technological implementation. Successively, drawing from the perspectives of Complete Quality Experiencing (CQE) [38] and the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) concept [39], two scales were developed for the questionnaire survey to gather the audience’s opinions. One scale focused on measuring the magic experience, while the other aimed to assess understanding of multimedia technology.

Tzortzi et al. [25] assessed the audience evaluation of a projection’s installation in the Tower of Winds, under the Acropolis of Athens, Greece, by combining in-field observation of the visitors and the distribution of a questionnaire among them.

To design the evaluation system for a SAR experience in Tangcheng, China, Li and Ito [12] conducted interviews with design and technology experts to identify key items to be included in a questionnaire distributed to visitors. Moreover, they experienced an in situ investigation, performing a self-evaluation of the installation through the Timeline Analysis Method, to design a comprehensive questionnaire for visitors. They report that the American Customer Satisfaction Index (ACSI) model [40] has been used in numerous studies to evaluate satisfaction and loyalty in heritage tourism, as well as Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) to evaluate satisfaction [41]. Hernández-Rojas et al. [29], in their evaluation study of tourism in the Citadel of the Catholic King of Córdoba, Spain, based their investigation on the ACSI model. Focusing on loyalty and satisfaction measuring, they report that in the literature, loyalty is typically examined in two ways: by analyzing repeat purchases—namely, tourists returning to a destination—and, more interestingly, by considering loyalty as the likelihood of recommending the destination to future tourists. A five-section questionnaire was developed following this approach.

Leopardi et al. [9] investigated users’ experiences in an XR application for a museum context. They extrapolate three scales from the literature to measure the experience: the Presence scale from Yim et al. [42], the quality of Visitors’ Experience based on Pine and Gilmore’s four experience realms (4E) [43], and an Attitude towards the Experience (ATE) measurement to evaluate the valence of hedonic experiences.

Basballe and Halskov [34] adopted the model developed by Mailund and Halskov (M&H) to measure user engagement in an interactive SAR installation [44], comparing the physical design, interaction, and content of the experience with its behavioral, cognitive, and affective effects on users.

Finally, Liu [4] employed a mixed-methodology approach, combining questionnaires based on a digital experience evaluation framework with semi-structured interviews, in Old Zuoying City, Taiwan, to assess visitors’ experiences. In-field observations and interviews with stakeholders and practitioners of the cultural site led to the design and development of a questionnaire and a follow-up interview for visitors. The questionnaire has been divided into three sections: pre-visit exploration of prior knowledge, motivations, and expectations; on-site visitation; and post-visit, focusing on final satisfaction and gains from the visit. The second part of the questionnaire is based on User Experience (UX) evaluation frameworks.

Figure 4.

Graphic summary of the evaluation methods reported in the identified studies. Terminology was reported as used in the original reference papers [3,4,5,9,11,12,17,23,25,29,34,42].

4. Discussion

From the literature, studies concerning SAR in the cultural domain are present, describing applications of this technology in several cases, or inserting it in a broader discussion on cultural communication through digital technologies; however, the literature field lacks a comprehensive overview of this technology within the cultural sector, grouping the studies on the various applications, definitions, and uses of SAR in museums and cultural institutions. This review aims to address this gap by providing an integrative overview of the existing research landscape on SAR.

Starting from 366 articles identified in the Scopus and Web of Science engines, the scoping review process ultimately identified a total of 34 papers. From this collection, several pieces of information were qualitatively extracted, revealing key themes within the broad landscape of SAR applications in the cultural heritage sector.

Primarily, the authors reported on the various terminologies encountered in the literature related to SAR technology.

Next, the literature provides definitions of SAR and outlines its benefits across different cultural contexts and uses. These benefits include the versatility of the technology in several fields and applications, its attractiveness to different users—operators, designers, and visitors—and the possibility of experiencing the installation between multiple users without a potentially distracting layer of a device. Moreover, SAR has a strong narrative potential, thus acting as an ideal mediator between tangible and intangible cultural heritage and the audience. The use of this technology is reported to enrich visitors’ experiences in the exhibition from different perspectives, ranging from engagement to learning assessment.

Depending on the specific case, various assessment methods and evaluation strategies have been employed to analyze visitors’ experiences in relation to the technological and cultural configurations presented.

4.1. Benefits of SAR

The literature review highlights several advantages associated with the application of SAR in museum settings. First, the attractiveness of the technology positively influences pre-visit engagement by stimulating visitors’ curiosity and expectations, and it is also reported to be appealing to museum professionals and creative practitioners. SAR enriches cultural exhibitions and installations by increasing engagement across multiple dimensions—cognitive, emotional, and behavioral—while supporting learning processes, facilitating more effective communication of information, and encouraging social interaction among visitors. From a technical standpoint, SAR is described as a highly versatile technology that can adapt to diverse application contexts. In comparison to other AR systems, a further advantage lies in the possibility of hiding the technological device, thereby enabling more seamless and fluid visitor experiences. Finally, SAR is reported to function as an effective mediator of cultural heritage, bridging past and present as well as tangible and intangible dimensions through engaging and persuasive storytelling.

As a direction for future research, it would be valuable to perform a comparative analysis between SAR and other types of AR technologies, as well as other typologies of digital technologies. Additionally, comparative studies examining users’ cultural experiences in the presence and absence of such installations could help assess the specific benefits of SAR relative to alternative interpretive or experiential conditions.

4.2. Evaluation Methods

Several evaluation methods have arisen from the analysis of the review. Generally, the most commonly used method of inquiry is distributing a questionnaire to visitors or museum stakeholders, potentially designed based on interviews or observations conducted with previously identified specific groups (e.g., field or technological experts, visitors, or other cultural stakeholders). Different studies have investigated various users’ experience dimensions related to their theoretical approaches or the purpose of their evaluation activity (e.g., learning, engagement). The UEQ has been reported as an effective tool for evaluating the overall experience. Other cases also conducted semi-structured interviews to assess the perspectives of visitors and stakeholders. One study analyzing a performative experience employs the perspectives of the CQE and the TAM to develop its method of inquiry with the audience. The ACSI has also been reported as a tool frequently used in evaluating visitors’ satisfaction and loyalty to the cultural heritage experience. One study also employed the SEM approach in its inquiry. Pine and Gilmore’s Experience Theory and the ATE measurement have been chosen as the theoretical basis for evaluating visitors’ experiences. User engagement has also been evaluated through the theoretical square developed by Mailund and Halskov, which relates engagement dimensions to the exhibition’s characteristics. A final study assesses visitors’ experiences into three main phases: the moment before the cultural visit, during, and after the experience. For each phase, different dimensions were evaluated, while the second part of the questionnaire is based on UX design evaluation frameworks.

Different methods, tools, and theoretical approaches have been adopted in the literature to assess users’ experiences. Observation techniques, questionnaire-based instruments, and interviews emerge as the most commonly employed evaluation methods. These assessments primarily focus on visitors’ experiences of the installations.

Assessing the efficacy of the methods and approaches found in the literature may be the object of a future study: a comparative analysis of the evaluation frameworks and methods adopted across studies may represent a valuable direction for future research, particularly in identifying which tools, methods, or theoretical approaches are most appropriate for addressing specific research objectives and user or stakeholder groups within museum contexts. Cultural systems are inherently complex, involving multiple stakeholders and user groups with diverse perspectives and objectives related to exhibitions and experiences. Consequently, the evaluation of cultural experiences requires consideration of multiple dimensions and should be informed by existing research on visitor experience and museum environments, taking into account the integration of theoretical approaches from this field of study.

Moreover, the inquiry should also address the suitability of the methods and approaches of evaluation with the specific technological domain, thus considering also the coherence of the investigation tools with SAR characteristics, as an XR and digital technology used for cultural installations and experiences.

Identifying appropriate evaluation procedures for this specific domain and technology could support researchers in collecting the outcomes, benefits, limitations, and methodological implications of using SAR in cultural experiences.

4.3. Identified Gaps

The review identifies several gaps in the existing literature. First, although previous studies in visitor research and museum practice have extensively examined the museum experience and proposed a variety of theoretical perspectives and models, there is currently a lack of clear and shared guidelines for evaluating digital technology installations within museum contexts. In particular, SAR technologies, as well as other XR installations, lack a consolidated framework for investigating their impact on visitor experience, as well as on the perspectives of museum stakeholders and practitioners [4,7,12]. Researchers are starting to address this gap, with several studies proposing new methods of inquiry grounded in UX design principles [45].

Kim et al. [24] highlight the limited use of sensory stimuli in many SAR installations, which primarily rely on visual and auditory modalities. Future research could address this gap by exploring the integration of additional sensory dimensions, thereby examining how multisensory interaction may enhance visitor engagement and the overall interactive systems underpinning SAR experiences.

The following consideration does not constitute a research gap per se, but rather a reflection on the modes through which SAR—and, more broadly, digital technologies—are applied within the cultural domain. Boletsis [13] and De Paolis et al. [11] observe that SAR applications in cultural contexts often prioritize artistic expression and public engagement through the activation of a “wow” effect, with a strong emphasis on special effects rather than on the development of a coherent visual or cultural narrative. A rapid overview of existing SAR applications in museums and other cultural experiences appears to support this observation. In this regard, it is valuable to reconnect with the questions raised by Farré Torras et al. [26] concerning the mediation and experience of cultural exhibitions through digital media. The authors emphasize that a work of art cannot be reduced to its digital image alone, as it embodies materiality, manual craftsmanship, and historical and social contexts that have accumulated over time. Digital mediation, therefore, poses the challenge of translating these layered dimensions into a meaningful digital discourse while maintaining a coherent relationship with the physical object.

Yang and Greenop [46] argue for a critical approach to digital cultural heritage that extends beyond the technical aspects of digitizing artefacts or sites to question, more fundamentally, the motivations and implications of such digitization. They emphasize the role of researchers in interrogating these processes and in reflecting on how digital interventions may reshape and redefine existing concepts of heritage. We therefore advocate for a fully co-designed approach to digital cultural exhibitions and installations, bringing together designers, developers, researchers, museum practitioners, stakeholders, theoretical experts, and visitors, and considering all these perspectives as essential for the construction of culturally coherent experiences.

5. Conclusions

This review provides an overview of the definitions, applications, and uses of SAR technology within the cultural domain. The need for this review arose from the identification of a gap in the existing literature, specifically the lack of a comprehensive overview of the technological landscape in SAR for the cultural heritage sector. Following the PRISMA-ScR guidelines and employing a snowball sampling approach in the construction of this scoping review, a total of 34 papers were ultimately analyzed to address the initial research questions.

The review highlights several advantages of applying SAR technology in cultural contexts, particularly in museum settings, as reported in the literature from the perspectives of different user groups, including visitors, museum stakeholders, and practitioners. Overall, SAR is described as having a positive impact across multiple dimensions within the sector. However, the literature still lacks a systematic evaluation of the benefits of SAR in relation to other digital technologies used in cultural environments. Comparative analyses between SAR and other AR or VR systems could yield valuable insights into the respective roles and suitability of these technologies within museum contexts. Similarly, comparative analyses examining cultural experiences with and without the use of this technology may contribute to a deeper understanding of its cultural effectiveness for both visitors and stakeholders within the field.

Future research should also address not only the advantages, but potential limitations and challenges associated with the use of SAR. Engaging in dialogue with both technological experts and field practitioners may help surface these aspects and contribute to a more comprehensive assessment of the adoption of SAR in the cultural heritage domain.

The study also documents the range of evaluation methods employed in the literature to assess the perspectives of museum visitors and cultural stakeholders regarding SAR technology. The reviewed studies adopt a variety of methodological approaches, underscoring the breadth of possibilities available to researchers for evaluating such experiences. Visitor experience constitutes a broad and evolving field of inquiry, supported by multiple theoretical models and analytical frameworks that have developed over time in parallel with changes in museum practices and cultural experiences. Integrating theoretical perspectives from museum and visitor studies with technology-driven and experience-oriented evaluation methodologies appears to offer a comprehensive approach to addressing the complexity of visitor experience. Moreover, both pre-visit and post-visit phases are recognized as integral components of the museum experience and should be considered when evaluating technological installations. Accordingly, it is essential to clarify the primary objectives of an evaluation at the outset: whether the focus lies on cognitive outcomes such as information sharing and learning, on emotional or behavioral engagement, or on patterns of direct interaction between visitors and the technological installation. This, in turn, requires an explicit consideration of the institution’s goals, visitors’ expectations, and the intended role of the installation—whether to convey cultural knowledge, to create emotional impact, or to generate a persuasive and engaging “wow” effect. A comparative case study analysis may be beneficial in deepening our understanding of these evaluation assessment approaches, thereby understanding their efficacy in the context of this specific technology and cultural domain.

This scoping review offers an overview of current research on Spatial Augmented Reality in the cultural heritage domain; however, several limitations must be acknowledged. The review is based on a limited set of research databases and remains largely descriptive, indicating the need for broader literature coverage and for comparative analyses to more robustly assess the benefits of SAR in relation to other digital technologies. Furthermore, additional work is needed to consolidate and compare evaluation methods, particularly in relation to established frameworks for visitor experience. The limitations in the reported benefits and characteristics of SAR technology identified in this review are also influenced by the diversity of assessment methods employed across the analyzed studies to derive and interpret these results. Finally, given the applied nature of the field, future research should integrate non-academic perspectives, including those of museum professionals and practitioners, to complement academic viewpoints. At the same time, the review reveals a fragmentation in terminology and evaluation approaches, indicating the need for greater conceptual clarity and methodological alignment across studies.

To conclude, future research should pursue more systematic and comparative assessments of SAR in relation to other immersive technologies, address potential limitations alongside benefits, and develop robust evaluation frameworks of technological installations that account for the complex, multi-dimensional nature of cultural experiences.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.D., D.S. and M.A.C.; methodology, D.S. and M.A.C.; software, M.D.; validation, M.D., D.S. and M.A.C.; formal analysis and investigation, M.D.; resources and data curation, M.D.; writing—original draft preparation, M.D.; writing—review and editing, D.S. and M.A.C.; visualization, M.D.; supervision and project administration, D.S. and M.A.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data cited in the review were derived from the following resources available in the public domain: Scopus Elsevier [https://www.scopus.com/ (accessed on 15 November 2025)], Web of Science Clarivate [https://clarivate.com/ (accessed on 15 November 2025)].

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this review, the authors used ChatGPT-5.2 and Deepl for the purposes of checking academic English language. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SAR | Spatial Augmented Reality |

| XR | Extended Reality |

| AR | Augmented Reality |

| VR | Virtual Reality |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| WoS | Web of Science |

| UEQ | User Evaluation Questionnaire |

| CQE | Complete Quality Experience |

| TAM | Technology Acceptance Model |

| ACSI | American Customer Satisfaction Index |

| SEM | Structural Equation Modeling |

| 4E | Four Experiences (Pine & Gilmor) |

| ATE | Attitude Towards the Experience |

| M&H | Mailund and Halskov |

| UX | User Experience |

References

- Jo, Y.H.; Kim, J.; Cho, N.C.; Lee, C.H.; Yun, Y.H.; Kwon, D.K. A study on planning and platform for interactive exhibition of scientific cultural heritage. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2019, 42, 605–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kryvuts, S.; Gonchar, O.; Skorokhodova, A.; Radomskyi, M. The phenomenon of digital art as a means of preservation of cultural heritage works. Muzeol. Kult. Dedicstvo 2021, 9, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Z. Designing 3D mapping projections for art museums based on “re-contextualization”: A case study of The Night of Museum. Cogent Arts Humanit. 2025, 12, 2492426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Evaluating visitor experience of digital interpretation and presentation technologies at cultural heritage sites: A case study of the old town, Zuoying. Built Herit. 2020, 4, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolakopoulou, V.; Printezis, P.; Maniatis, V.; Kontizas, D.; Vosinakis, S.; Chatzigrigoriou, P.; Koutsabasis, P. Conveying intangible cultural heritage in museums with interactive storytelling and projection mapping: The case of the Mastic villages. Heritage 2022, 5, 1024–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaper, M.-M.; Santos, M.; Malinverni, L.; Zerbini Berro, J.; Pares, N. Learning about the past through situatedness, embodied exploration and digital augmentation of cultural heritage sites. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2018, 114, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Huang, D. Influence mechanisms of museums’ technological embodiment and tourist satisfaction. SAGE Open 2025, 15, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, T.; Tom Dieck, M.C.; Lee, H.; Chung, N. Effects of virtual reality and augmented reality on visitor experiences in museum. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2016; Inversini, A., Schegg, R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 621–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leopardi, A.; Ceccacci, S.; Mengoni, M.; Naspetti, S.; Gambelli, D.; Ozturk, E.; Zanoli, R. X-reality technologies for museums: A comparative evaluation based on presence and visitors’ experience through user studies. J. Cult. Herit. 2021, 47, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaz, X.; Garcia, R.; Ortiz, A.; Marichal, S.; Villadangos, J.; Ardaiz, O.; Marzo, A. An interdisciplinary design of an interactive cultural heritage visit for in-situ, mixed reality and affective experiences. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2022, 6, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Paolis, L.T.; Liaci, S.; Sumerano, G.; De Luca, V. A video mapping performance as an innovative tool to bring to life and narrate a pictorial cycle. Information 2022, 13, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Ito, H. Visitor’s experience evaluation of applied projection mapping technology at cultural heritage and tourism sites: The case of China Tangcheng. Herit. Sci. 2023, 11, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boletsis, C. The Gaia system: A tabletop projection mapping system for raising environmental awareness in islands and coastal areas. In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on PErvasive Technologies Related to Assistive Environments, Corfu, Greece, 29 June–1 July 2022; pp. 50–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, V.; Gatto, C.; Liaci, S.; Corchia, L.; Chiarello, S.; Faggiano, F.; Sumerano, G.; De Paolis, L.T. Virtual reality and spatial augmented reality for social inclusion: The “Includiamoci” project. Information 2023, 14, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez Manzanares, Á.; Benítez, A.J.; Martínez Antón, J.C. Virtual restoration and visualization changes through light: A review. Heritage 2020, 3, 1373–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mine, M.R.; Van Baar, J.; Grundhofer, A.; Rose, D.; Yang, B. Projection-based augmented reality in Disney theme parks. Computer 2012, 45, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nofal, E.; Stevens, R.; Coomans, T.; Vande Moere, A. Communicating the spatiotemporal transformation of architectural heritage via an in-situ projection mapping installation. Digit. Appl. Archaeol. Cult. Herit. 2018, 11, e00083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridel, B.; Reuter, P.; Laviole, J.; Mellado, N.; Couture, N.; Granier, X. The revealing flashlight: Interactive spatial augmented reality for detail exploration of cultural heritage artifacts. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 2014, 7, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, H.; Kim, H. A study on the media arts using interactive projection mapping. Contemp. Eng. Sci. 2014, 7, 1181–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-SCR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera, L.; Coma, I.; Pérez, M.; Riera, J.V.; Martínez, B.; Gimeno, J. The Mediterranean forest in a science museum: Engaging children through drawings that come to life in a virtual world. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2024, 83, 76851–76872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-M.; Huang, Q.-J. Design of a technology-based magic show system with virtual user interfacing to enhance the entertainment effects. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 5535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Choi, D.; Lee, J. EMPop: Pin-based electromagnetic actuation for projection mapping. In Proceedings of the Extended Abstracts of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, 11–16 May 2024; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzortzi, K.; Schieck, A.F.G.; Printezis, P.; Kontogeorgopoulou, E.-M.; Efthymiou, E.; Vourloumi, M.; Maniatis, V. Longue durée: Perceiving heritage through media architecture. In Proceedings of the 6th Media Architecture Biennale Conference, Toronto, ON, Canada, 14–23 June 2023; pp. 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farré Torras, B.; Crespillo Marí, L.; Soares, M. Post wow, is less more? A critical approach to animated mapped projection for art historical knowledge sharing: The twentieth-century mural as a case study. Magazén 2024, 5, 149–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guefrech, F.B.; Berthaut, F.; Plenacoste, P.; Peter, Y.; Grisoni, L. Revealable volume displays: 3D exploration of mixed-reality public exhibitions. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Virtual Reality and 3D User Interfaces (VR), Lisboa, Portugal, 27 March–1 April 2021; pp. 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsharkawy, A.; Naheem, K.; Koo, D.; Kim, M.S. A UWB-driven self-actuated projector platform for interactive augmented reality applications. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 2871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Rojas, R.D.; Del Río, J.A.J.; Fernández, A.I.; Vergara-Romero, A. The cultural and heritage tourist, SEM analysis: The case of the Citadel of the Catholic King. Herit. Sci. 2021, 9, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbiani, C.; Guerra, F.; Pasini, T.; Visonà, M. Representing with light: Video projection mapping for cultural heritage. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2018, 42, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, S.; Steinicke, F.; Irlitti, A.; Thomas, B.H. Floor-projected guidance cues for collaborative exploration of spatial augmented reality setups. In Proceedings of the 2018 ACM International Conference on Interactive Surfaces and Spaces, Tokyo, Japan, 25–28 November 2018; pp. 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Wu, L.; Li, X. When art meets tech: The role of augmented reality in enhancing museum experiences and purchase intentions. Tour. Manag. 2018, 68, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabellone, F. Digital technologies and communication: Prospects and expectations. Open Archaeol. 2015, 1, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basballe, D.A.; Halskov, K. Projections on museum exhibits: Engaging visitors in the museum setting. In Proceedings of the 22nd Conference of the Computer-Human Interaction Special Interest Group of Australia on Computer-Human Interaction, Brisbane, Australia, 22–26 November 2010; pp. 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bimber, O.; Raskar, R. Spatial Augmented Reality: Merging Real and Virtual Worlds; Peters: Wellesley, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Milgram, P.; Kishino, F. A taxonomy of mixed reality visual displays. IEICE Trans. Inf. Syst. 1994, E77-D, 1321–1329. [Google Scholar]

- Laugwitz, B.; Held, T.; Schrepp, M. Construction and evaluation of a user experience questionnaire. In HCI and Usability for Education and Work; Holzinger, A., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.-Y.; Horng, S.-C. Conceptualizing and measuring experience quality: The customer’s perspective. Serv. Ind. J. 2010, 30, 2401–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Warshaw, P.R. User acceptance of computer technology: A comparison of two theoretical models. Manag. Sci. 1989, 35, 982–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgeson, F.V.; Hult, G.T.M.; Sharma, U.; Fornell, C. The American Customer Satisfaction Index (ACSI): A sample dataset and description. Data Brief 2023, 48, 109123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Danks, N.P.; Ray, S. (Eds.) An introduction to structural equation modeling. In Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R: A Workbook; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, M.Y.; Cicchirillo, V.J.; Drumwright, M.E. The impact of stereoscopic Three-Dimensional (3-D) advertising. J. Advert. 2012, 41, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, B.J.; Gilmore, J.H. The Experience Economy; Harvard Business Press: Brighton, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mailund, L.; Halskov, K. Designing marketing experiences. In Proceedings of the 7th ACM Conference on Designing Interactive Systems, Cape Town, South Africa, 25–27 February 2008; pp. 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, E.; Smith, M.P.; Wilson, P.F.; Stott, J.; Williams, M.A. Creating meaningful museums: A model for museum exhibition user experience. Visit. Stud. 2023, 26, 59–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Greenop, K. Introduction: Applying a landscape perspective to digital cultural heritage. Built Herit. 2020, 4, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.