Abstract

This paper presents a dual four-port circularly polarized (CP) MIMO antenna based on substrate integrated waveguide (SIW) technology for sub-6 GHz applications. The design consists of two identical four-port SIW-based CP-MIMO antennas arranged in a mirror-symmetric configuration with an air gap of 15 mm. Each antenna employs four symmetrically arranged cross-shaped SIW patches excited by coaxial probes. Bidirectional radiation is achieved by applying a 180° phase difference between corresponding ports of the mirror symmetric configuration, referred to as the Backward-Radiating Unit (BRU) and the Forward-Radiating Unit (FRU). The bidirectional radiation mechanism is supported by array-factor-based theoretical modelling, which explains the constructive and destructive interference under phase-controlled excitation. To ensure high isolation and stable polarization performance, the antenna design incorporates defected ground structures, inter-element decoupling strips, and vertical metallic vias. Simulations indicate an operating band from 5.1 to 5.4 GHz. Measurements show a −10 dB bandwidth from 5.25 to 5.55 GHz, with the frequency shift attributed to fabrication tolerances and measurement uncertainties. The antenna achieves inter-port isolation better than −15 dB. A 3 dB axial-ratio bandwidth is maintained across the operating band. Measured axial-ratio values remain below 3 dB from 5.25 to 5.55 GHz, while simulations predict a corresponding range from 5.1 to 5.4 GHz. The proposed configuration achieves a peak gain exceeding 4 dBi and maintains an envelope correlation coefficient below 0.05. These results confirm its suitability for CP-MIMO systems with controlled spatial coverage. With a physical size of 0.733λ0 × 0.733λ0 per array, the proposed antenna is well-suited for vehicular and space-constrained wireless systems requiring bidirectional CP-MIMO coverage.

1. Introduction

Multiple-Input Multiple-Output (MIMO) antenna technology is a crucial element of modern wireless communication systems, significantly enhancing data transmission across various applications, including Wi-Fi (WLAN) and 5G cellular networks [1,2]. Its widespread use is due to its ability to significantly enhance channel capacity, spectral efficiency and link reliability without requiring an increase in allocated bandwidth or transmit power [3,4]. At its core, MIMO systems leverage the natural multipath propagation present in wireless environments by treating each reflected signal path as an independent spatial channel between the transmitting and receiving antennas. This method allows for the parallel transmission of multiple data streams, greatly improving the overall capacity and reliability of the system [5,6]. By integrating spatial multiplexing and diversity techniques, MIMO systems facilitate robust communication while also supporting multiple users at the same time. This capability is essential for addressing the high throughput and reliability requirements of emerging technologies [7].

To enhance the performance and reliability of communication systems, especially in complex and dynamic environmental conditions, the polarization characteristics of antennas are critically important. Among various polarization schemes, circular polarization (CP) is becoming increasingly essential in modern antenna design due to its distinct advantages over linear polarization (LP) [8]. A circularly polarized wave features an electric field vector that maintains a constant magnitude while rotating in a circular motion as it propagates through space. This rotational property gives circularly polarized antennas better resilience against polarization mismatch, which is a common issue in dynamic and arbitrarily oriented environments [9]. Furthermore, CP effectively mitigates the effects of Faraday rotation in the ionosphere and significantly reduces multipath fading, leading to more stable and reliable communication links [10]. Additionally, CP minimizes polarization mismatch losses in dense urban multipath environments, thereby enhancing link reliability and packet reception performance in IEEE 802.11p and V2X systems [11].

To realize CP in planar antennas, designers typically aim to excite two orthogonal modes of similar amplitude that are 90° out of phase [12]. They employ various design strategies to create these conditions, such as modifying the corners of patches, inserting diagonal slots, using asymmetric feeds with precise phase differences, implementing multiple feed networks with controlled phase shifts, and embedding metallic perturbation slots on either the radiating patch or the ground plane [13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. The integration of MIMO technology further enhances system performance by combining spatial and polarization diversity. This combined effect is particularly beneficial in compact mobile devices where antennas cannot be widely spaced [20]. To support such compact designs, techniques like Defected Ground Structures (DGS) are increasingly utilized. DGS involves etching specific patterns into the ground plane of the antenna to disturb surface currents and electromagnetic fields. This process improves impedance matching and helps create the orthogonal modes required for CP [21,22,23].

However, in compact MIMO antenna arrays, the close proximity of multiple radiating elements is essential to achieve high element density and utilize polarization diversity. This proximity can lead to mutual coupling, which poses a significant design challenge as it degrades overall system performance. Unwanted electromagnetic interactions can substantially reduce the isolation between antenna ports, distort radiation patterns, and affect impedance matching. These issues ultimately diminish MIMO system efficiency and compromise polarization quality [24]. Additionally, increased mutual coupling results in a higher Envelope Correlation Coefficient (ECC) and Channel Capacity Loss (CCL), both of which negatively impact communication performance [25].

To address the challenges posed by mutual coupling in compact MIMO antennas, researchers have extensively explored various decoupling techniques. These methods include the use of DGS, metamaterials, metasurfaces, complementary split-ring resonators (CSRRs), neutralization lines, and the strategic orthogonal placement of antenna elements [26,27,28,29]. While each of these approaches helps reduce inter-element interference, they often introduce design complexities, such as increased fabrication costs, limited bandwidth, and difficulties in integrating with high-density antenna arrays. As wireless applications continue to demand both miniaturization and consistent performance, there is a need for more integrated and scalable solutions.

In complement to these conventional methods, Substrate Integrated Waveguide (SIW) technology has emerged as a powerful framework that inherently supports low mutual coupling while maintaining compactness and low insertion loss. This is particularly significant in the 5 GHz band, which is crucial for high-speed data transmission in Wi-Fi (IEEE 802.11ac/ax) and emerging sub-6 GHz 5G networks [30,31]. SIW structures offer excellent electromagnetic confinement and isolation, making them ideal candidates for MIMO integration [32]. The synergy between SIW technology and MIMO is further enhanced when CP is employed, due to CP’s inherent resilience to multipath fading and orientation mismatch. The convergence of SIW technology with CP and MIMO functionality in the 5 GHz band marks a significant advancement in antenna research. This approach aims to combine the compact and low-loss design benefits of SIW with the polarization robustness of CP and the high data capacity and reliability provided by MIMO systems [33,34].

Recent studies highlight various strategies to realize CP in SIW-based antennas and extend these techniques to MIMO systems [35,36,37]. For such systems, multiple SIW cavity-backed slots can be integrated into a single substrate, often sharing a common ground plane or utilizing specialized decoupling structures between the cavities to minimize mutual coupling while preserving circularly polarized performance [38,39]. Recent developments in sub-6 GHz SIW-based MIMO antennas have explored metamaterial loading to enhance bandwidth, isolation, gain, and polarization characteristics [40]. Similarly, quad-band metamaterial-loaded cavity-backed SIW MIMO antennas have been proposed to achieve high gain and CP across multiple frequency bands, relying on superstrate or cavity-based loading to control radiation characteristics [41]. More recently, studies have also investigated high-permittivity dielectric and ceramic-based quad-port MIMO antennas for vehicular and sub-6 GHz applications, utilizing dielectric resonator loading and material-assisted decoupling [42].

While these innovations have enhanced isolation and polarization stability in compact MIMO designs, another important functionality gaining traction in modern wireless systems is bidirectional radiation. The demand for bidirectional antennas stems from advanced applications such as full-duplex relaying, simultaneous uplink and downlink transmission, vehicular-to-everything (V2X) communications, and UHF RFID tags [43,44,45]. These applications require antennas that can radiate in two opposing directions. In contrast to conventional antennas that are generally designed for either unidirectional or omnidirectional radiation, these emerging use cases necessitate arrays capable of efficiently radiating in opposite spatial directions. The principle of electromagnetic superposition serves as the foundation for creating such radiation patterns. When electromagnetic waves from multiple antenna elements are coherently combined, the resulting far-field pattern can be shaped based on the amplitude and phase relationships among the elements [46]. This capability for pattern shaping can be further enhanced by incorporating parasitic elements, inserting slots or cavities within the radiating structure, or optimizing feed networks to support directional gain and minimize cross-polarization [47,48]. For instance, Bakar Rohani et al. demonstrated a low-profile 4 × 4 MIMO bidirectional antenna that utilized vertically stacked notch and loop antennas, each fed independently. This design allowed for dual-polarized radiation aimed at two opposing hemispheres, providing a compact and effective solution for directional MIMO operation [49].

Despite significant progress, the practical implementation of SIW-based circularly polarized MIMO antennas continues to face inherent challenges. Common feeding mechanisms, such as edge coupling or proximity-fed slots, often struggle to maintain consistent axial ratio (AR) performance across the operating band. These challenges highlight the need for an antenna design that can achieve high isolation, stable CP, and scalability simultaneously. In addition to ensuring high-performance CP-MIMO operation at the element level, this work also addresses the requirement for bidirectional radiation through a system-level spatial configuration. Two identical four-port SIW modules are arranged in a mirror-symmetric manner and are designated as the Backward Radiation Unit (BRU) and the Forward Radiation Unit (FRU). The modules are spatially separated by 15 mm, with no intervening conductive or dielectric structures, which allows for independent field development.

By applying a controlled 180° phase difference between geometrically symmetric ports of the BRU and FRU, the combined structure generates a bidirectional radiation pattern. This is achieved through constructive interference in opposite spatial directions and destructive interference in unwanted directions. Consequently, the inherently asymmetric hemispherical radiation from each module is transformed into a coherent bidirectional beam without the need for physical reorientation, active switching, or reconfigurable antenna elements. The key contributions of this work are as follows:

- A structured six-stage design evolution of a quad-port SIW-based antenna is presented, explicitly demonstrating the progressive roles of ground modification, decoupling structures, and SIW integration in achieving impedance matching, enhanced isolation, and stable circular polarization.

- A mirror-symmetric dual four-port CP-MIMO architecture is introduced, in which two identical antenna modules inherently radiate in opposite spatial directions without modifying the individual antenna topology.

- A passive spatial phase-control strategy is employed, where a controlled 180° phase difference between corresponding ports of the two modules enables bidirectional radiation without the use of active switches, reconfigurable components, or complex feeding networks.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the SIW-based four-port MIMO antenna design and the systematic six-stage design evolution. Section 3 presents the performance analysis of 4-port SIW CP MIMO antenna. Section 4 introduces the realization of bidirectional patterns using dual four-port antenna. Section 5 discusses the experimental validation. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. SIW-Based Four-Port MIMO Antenna Design

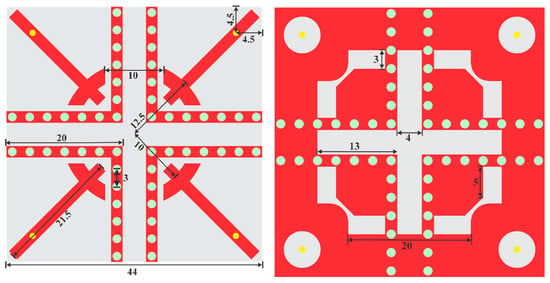

The proposed four-port circularly polarized MIMO antenna, illustrated in Figure 1, is designed to operate within the frequency range of 5 GHz to 5.4 GHz. All dimensions indicated in the figure are in millimeters (mm). At the core of the design is an angular ring patch, with an outer radius of 12.5 mm and an inner radius of 10 mm. This patch is carefully subdivided into four symmetrical arc-shaped segments. Each segment is connected via a diagonally positioned microstrip feed line, which has a specific length of 21.5 mm. By precisely controlling the current path and effective electrical length within the diagonal feed line, a coaxial probe feed is utilized, offset 4.5 mm from the edge of the substrate. This configuration fine-tunes the patch’s overall resonant frequency to align with the desired operating band. The excitation of each section from the corners is crucial for achieving a compact four-port MIMO configuration. The antenna is designed on an FR-4 substrate with a thickness of 1.6 mm. Additionally, each diagonal patch features two dedicated rectangular strips created through closely spaced vertical vias. These strips extend both horizontally and vertically from the edge, measuring 20 mm in length to cover the respective patch. Together with the via arrays, these strips are essential for the antenna’s decoupling and field confinement strategy. The bottom metallic layer contains a solid ground plane with a prominent central cross-shaped cutout and extensive SIW via arrays. The cross-shaped cutout has an overall length of 20 mm along its main arms and a central channel width of 4 mm. The cutout segments extend 13 mm from the center to their inner corners. Furthermore, the outer edges of the central cross-shaped cutout have an inward-bending section measuring 3 mm and a wider section near the corners measuring 5 mm. This ground plane SIW cavity is a critical component for both decoupling and CP generation.

Figure 1.

The proposed four-port SIW slotted antenna.

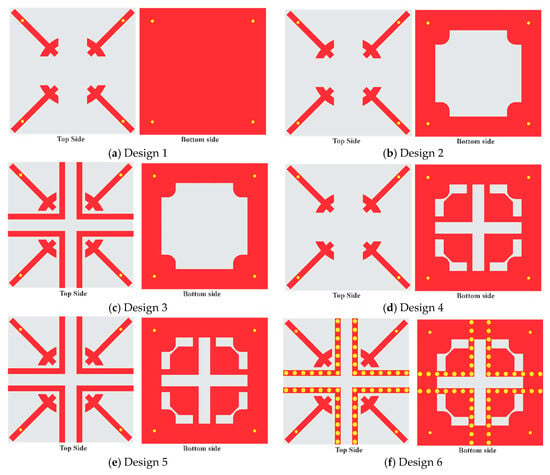

The development of the proposed four-port circularly polarized MIMO antenna followed a systematic optimization approach, starting from an initial reference excitation configuration and progressively evolving into a fully functional SIW cavity-backed antenna. The design elements have been systematically refined to meet specific performance parameters, including impedance matching, high inter-port isolation, and CP. The sequential design stages, labeled Design 1 through Design 6, are illustrated in Figure 2, with the corresponding simulated S-parameter responses for each stage shown in Figure 3. All design stages are designed within overall dimensions of 44 mm × 44 mm.

Figure 2.

Sequential implementation of antenna for optimization.

Figure 3.

Comparison of S parameters for different stages of implementation.

In the initial configuration, Design-1 metallic patches on the top layer serves as a reference excitation than a functional antenna. In this configuration, four diagonal feed locations are defined and excited using coaxial probes. The bottom layer remains a continuous ground plane without any defective ground cavity, resonant slot, or SIW enclosure. This structure does not support any radiating mode. As a result, no impedance resonance is observed, and the reflection coefficient (S11) remains close to 0 dB across the band, as shown in Figure 3a. At the same time, the transmission coefficients (Sij) in Design 1 remain relatively low. Although, this does not imply effective isolation, but rather indicates poor excitation and radiation efficiency due to the lack of impedance matching and structural optimization.

In the next stage, Design 2 maintains the four diagonally positioned radiating patches on the top layer, consistent with the layout from Design 1, while incorporating a modified ground structure. The continuous ground plane is replaced with one featuring symmetrical cutouts at the corners, resulting in a centrally aligned square aperture with smoothly curved inward edges. Each antenna element is still excited using a coaxial probe feed, with its placement optimized through parametric analysis. As illustrated in Figure 3b, the S-parameter results show a significant improvement in the reflection characteristics. There is a clearer resonance dip around 5.2 GHz, reaching approximately −15 dB, which is notably better than what was observed in Design 1. This improvement indicates some initial improvement in achieving impedance matching. However, despite the enhanced reflection coefficient, the structure still experiences high inter-port coupling. The introduction of the central square aperture with curved edges alone does not provide sufficient isolation between the ports. Specifically, S12 and S14 remain around −10 dB at the resonance frequency, indicating strong mutual coupling between the ports at the target resonance.

This lack of inter-port isolation near the operating band suggests that merely adding a slotted ground plane is insufficient to achieve acceptable MIMO performance. While the modified ground plane does begin to influence current distribution for impedance tuning, the absence of dedicated decoupling structures results in significant electromagnetic coupling among the radiating elements at resonance. Such conditions are undesirable for MIMO systems, where inter-element isolation should be below −15 dB to maintain low envelope correlation and avoid signal distortion or degradation in performance. Therefore, while Design 2 provides a solid baseline, it establishes a better impedance match and offers initial evidence of ground plane shaping to enhance performance. Subsequent structural modifications are then developed to improve decoupling and polarization characteristics.

In Design 3, further refinements aim to reduce the high inter-element coupling observed in Design 2. This enhancement is achieved by incorporating orthogonally oriented rectangular metal strips on the top surface between adjacent antenna elements, while maintaining the same diagonal radiating patch configuration and ground plane structure as in the previous design. These strips serve as passive isolation elements, helping to suppress mutual coupling by physically separating the radiating elements and modifying their electromagnetic interactions. The simulated S-parameters in Figure 3c demonstrate a significant improvement in isolation characteristics. The mutual coupling parameters, S12 and S14, are reduced to below −15 dB near the resonance band, indicating effective decoupling performance. However, the reflection coefficient S11 shows a noticeable shift in resonance frequency toward the higher end compared to Design 2. This frequency shift is likely due to changes in surface current paths and mutual capacitance between the elements, which affect the overall resonant behavior of the antenna system.

This observed improvement in inter-element isolation is attributed to the loading behavior introduced by the decoupling strips. These metallic strips alter the near-field surface-current distribution between adjacent antenna elements, effectively introducing a high-impedance path that suppresses mutual coupling. By interrupting the coupling loop formed by surface currents, the strips reduce electromagnetic interaction between ports and improve isolation. In addition to coupling suppression, the presence of these structures also modifies the local electromagnetic environment near the feed regions, which slightly perturbs the effective input impedance of the antenna elements. This interaction explains the observed shift in the resonance frequency in Design 3 compared to Design 2.

In Design 4, further optimization is achieved by focusing on inter-port isolation and the implementation of CP capabilities. To accomplish this, we remove the top-layer decoupling structure used in Design 3 and introduce a new ground plane configuration, building on the design from Design 2. This new refinement transforms the basic corner cutouts of the previous ground plane into a more advanced cross-shaped slot design with carefully engineered tapering and angular contours along its internal boundaries. This cross-shaped aperture significantly changes the distribution of return currents across the metallic ground plane. By guiding these currents along a longer and more complex path, the structure increases electrical length and introduces impedance mismatches, effectively creating a high-impedance barrier that hinders surface current propagation. As a result, we observe a notable reduction in mutual electromagnetic interaction. The S-parameter data for Design 4 indicate that mutual coupling terms, such as S12 and S14, consistently remain below −15 dB around the operating resonance, compared to levels above −10 dB observed in Design 2. In addition to improving isolation, the geometry of the ground plane is crucial for supporting CP. The guided current flow enabled by the cross-slot structure encourages the formation of orthogonal electric field components with the necessary 90° phase shift. This interaction, facilitated between the slanted top-layer radiating patches and the specially shaped ground current paths, creates the required conditions for generating circularly polarized radiation. The tapering and angular recesses are optimized to maintain this quadrature phase relationship across the operating band, thereby ensuring favorable AR.

In the development of the MIMO antenna, Design 5 strategically integrates the top layer of Design 3 with the bottom layer of Design 4. This dual-layer integration aims to simultaneously reduce mutual coupling and enhance polarization purity. The simulated S-parameters, illustrated in Figure 3e, demonstrate the effectiveness of this hybrid design. A significant improvement in inter-port isolation is observed, with S12 and S14 remaining well below −18 dB across the operating band, indicating successful mutual decoupling. Additionally, the reflection coefficient S11 shows a clear resonance around 5.2 GHz, similar to previous designs, while maintaining effective impedance matching. Notably, the resonance frequency is slightly shifted to a higher band compared to Design 2; this shift is attributed to the combined effects of surface current redirection and the altered electromagnetic field distribution introduced by the decoupling and CP structures.

In the next implementation step, Design 6 integrates vertical metallic vias into the MIMO antenna structure, effectively connecting the top and bottom layers. These vias are strategically positioned along both the vertical and horizontal axes, aligning with the intersecting cross-shaped metallic traces on each layer. By introducing periodic vias, we create vertical discontinuities in the surface current path, which serve as high-impedance barriers. This design helps suppress the propagation of surface and coupling currents between adjacent antenna elements, thereby improving inter-port isolation compared to Design 5. This enhancement particularly reduces mutual capacitive and inductive coupling. The simulated S-parameters indicate a significant decrease in mutual coupling, maintaining values consistently below −20 dB across the operational band.

3. Performance Analysis of 4-Port SIW CP MIMO Antenna

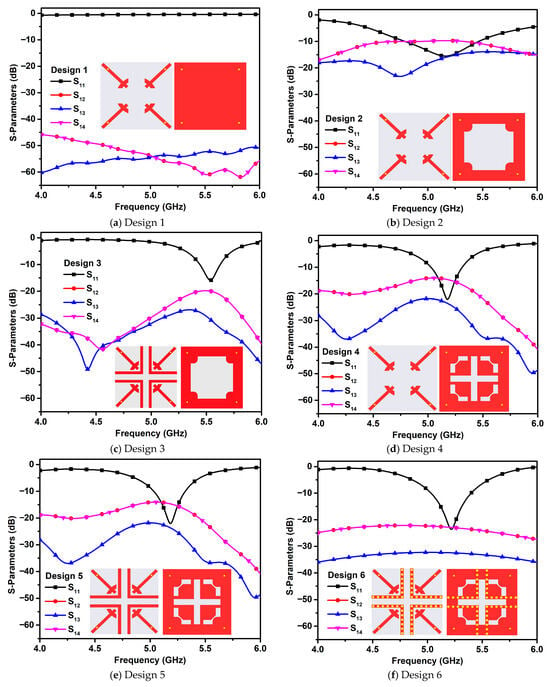

Following the design and optimization process outlined previously, which included simulated performance metrics such as impedance matching and inter-port isolation, the performance of the 4-port antenna configuration was further characterized through full-wave electromagnetic simulations. These simulations assessed various parameters, including AR, radiation patterns, and MIMO performance metrics. The simulated AR performance was extracted for the antenna configurations developed during the sequential optimization process (Designs 1 to 6) to evaluate the CP behavior.

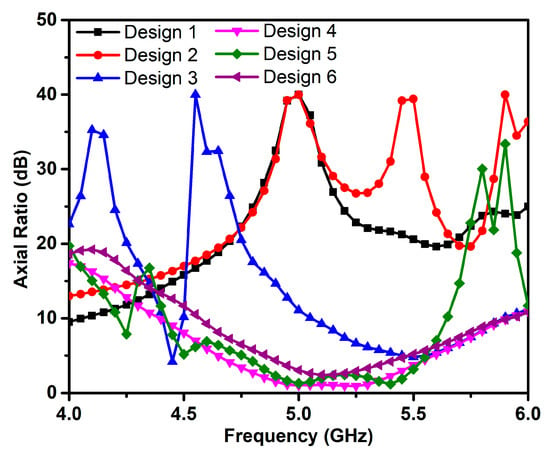

Figure 4 presents a comprehensive comparison of the AR performance across these design iterations, highlighting the progressive improvements that led to the final optimized structure. As shown in Figure 4, Design 1 demonstrates exceptionally poor AR performance across the entire frequency band, with values consistently above 30 dB. This outcome is expected since Design 1 represents a basic configuration without any intentional CP-generating mechanisms, resulting in predominantly linear polarization. Design 2 introduced a corner-cut ground plane and an optimized coaxial feed to improve impedance matching, leading to a slight, yet still inadequate, improvement in AR. Its AR values remain well above 20 dB across most of the band, reaffirming its primarily linear polarization state, as the ground modification at this stage was not specifically tuned for CP.

Figure 4.

Performance comparison of AR for different designs of implementation.

Design 3 introduced a top-side cross-shaped decoupling structure. While its primary role was to reduce coupling. Figure 4 indicates that this modification has an indirect, although noticeable, influence on the AR. We observe a broader range of AR values, with a slight dip towards lower AR around 4.8 GHz, reaching values around 10–15 dB. This suggests that altering the top-layer current distribution, even for decoupling purposes, starts to affect the fields and marginally impacts polarization. However, the AR values remain above 15 dB across the 5 GHz band, indicating that this design does not achieve CP.

Design 4 fundamentally refined the ground plane by incorporating a cross-shaped cutout with tapering and angular modifications, marking a critical turning point in the antenna’s CP performance. As clearly shown in Figure 4, Design 4 achieves a significant reduction in AR, with values dropping below 3 dB across the 5 GHz to 5.4 GHz operating band. The lowest AR is observed around 5.2 GHz, indicating excellent CP. This AR behavior, along with improved S-parameters, establishes Design 4 as the first iteration to successfully realize CP. Design 5 integrated the bottom layer of Design 4 with the top layer of Design 3, maintaining the required AR performance and isolation. Figure 4 and Figure 2e clearly illustrate that Design 4 achieves a significant reduction in AR, dropping below 3 dB, and maintains isolation well below −18 dB across the operating band. The final optimized design, Design 6, incorporates comprehensive SIW features across both metallic layers. Figure 4 clearly demonstrates that the SIW integration does not degrade the optimized CP behavior; instead, it contributes to overall field confinement and efficiency, ensuring the stability of the generated CP across the desired bandwidth.

The enhancement of antenna performance is further validated by a radiation efficiency of the system. While the initial non-SIW configuration (Design 4) exhibited an efficiency of approximately 50%, the comprehensive SIW implementation in Design 6 increases the radiation efficiency to greater than 60%. This improvement is attributed to the suppression of surface-wave losses and superior field confinement provided by the vertical via arrays. Although higher efficiencies reaching 80% can be achieved using low-loss substrates [50], the results obtained here using FR-4 represent a realistic trade-off for multi-port MIMO systems requiring cost-effective vehicular integration.

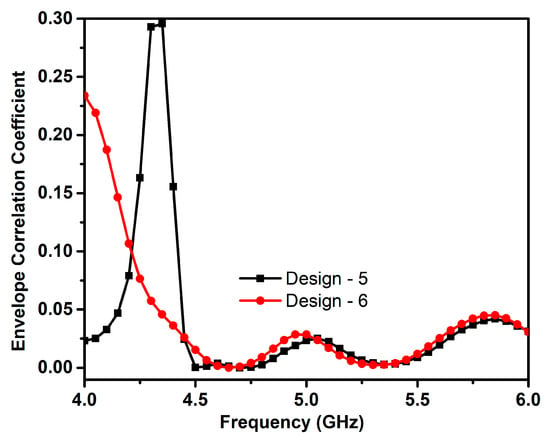

The performance of the MIMO system is further characterized by the ECC between ports i and j, which can be calculated from S-parameters given in Equation (1) [51]. It quantifies the statistical independence between the fading envelopes of signals received by different antenna elements. A lower ECC value indicates reduced signal correlation, which directly translates to enhanced diversity gain and improved channel capacity. For practical MIMO systems, an ECC value below 0.5 is generally considered acceptable, with values below 0.1 indicative of very good decorrelation.

The simulated ECC for both Design 5 and Design 6, as demonstrated in Figure 5, achieved an exceptionally low ECC across its entire operating bandwidth. The maximum ECC values within the target band are significantly lower than the generally accepted threshold of 0.5 and even surpass the ideal threshold of 0.1. Also, it is evident that Design 6 consistently exhibits a lower ECC across the majority of the operating band compared to Design 5. This indicates that the final comprehensive SIW integration in Design 6 effectively suppresses residual correlation, leading to superior decorrelation performance compared to Design 5. Such low ECC values are critical for maximizing the diversity gain and enhancing the channel capacity of the MIMO system, affirming the antenna’s robust performance in multipath-rich wireless communication environments.

Figure 5.

Simulated ECC for both Design 5 and Design 6.

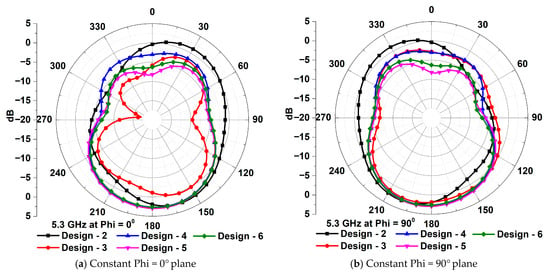

The spatial distribution of radiated power for the evolving antenna configurations was characterized through simulations. Figure 6 presents the simulated radiation patterns in the ϕ = 0° and ϕ = 90° planes at 5.2 GHz for various design stages. In Design 2, both the ϕ = 0° and ϕ = 90° planes show a broad radiation characteristic. The primary radiation is observed in the forward hemisphere, with peak radiation occurring around θ = 30° in the ϕ = 0° plane and θ = 124° in the ϕ = 90° plane. However, subsequent modifications introduced in Design 3 inadvertently distorted the radiation pattern in both planes. This design demonstrates a significant reduction in overall radiated power, with a notably low peak in the forward hemisphere at θ = 29° for the ϕ = 0° plane and θ = 138° for the ϕ = 90° plane. The patterns exhibit pronounced irregularities and nulls, indicating compromised radiation efficiency and uncontrolled energy distribution.

Figure 6.

Simulated radiation performance comparison in different stages of implementation.

In Design 4, significant changes in directional behavior are observed due to a refined ground plane structure. In both the ϕ = 0° and ϕ = 90° planes, this design consistently directs its primary radiation towards the backward hemisphere, achieving a peak radiation around θ ≈ 172° in both planes. This indicates a strong preference for radiation in the opposite direction of the broadside, where it remains significantly lower across both planes. Design 5 continues this trend of backward-directed radiation, with its pattern also peaking in the backward hemisphere, similar to Design 4. While the overall pattern shape demonstrates more control than in Design 3, the predominant radiation remains consistently directed away from the broadside.

The final optimized configuration, Design 6, represents the culmination of the design iterations in pattern control and the suppression of undesired lobes. In both the ϕ = 0° and ϕ = 90° planes, Design 6’s radiation pattern shows a persistent tendency to radiate towards the backward hemisphere, with its main lobe peaking at approximately θ ≈ 169° in both planes. Despite this consistent backward-directed primary beam, the pattern exhibits superior symmetry and a marked reduction in side lobes compared to earlier stages. This indicates a well-controlled radiation pattern with efficient energy transfer, even if the primary direction is not broadside. The resulting pattern, featuring a well-managed main lobe and suppressed spurious radiation, validates the effectiveness of the comprehensive SIW integration and optimization techniques in shaping electromagnetic energy distribution.

The achieved pattern, with its managed main lobe and suppressed spurious radiation, validates the effectiveness of the comprehensive SIW integration and optimization techniques in shaping electromagnetic energy distribution.

The observed backward radiation pattern indicates that, while the antenna exhibits excellent CP purity, its main lobe is directed away from the conventional broadside. If the goal is to achieve forward-facing radiation suitable for infrastructure-based directional applications, this backward-dominant pattern reveals the impact of the current distribution shaped by the optimized geometry. To obtain forward radiation under these constraints, one would either need to physically orient the antenna or implement additional structural enhancements. Alternatively, for bidirectional radiation coverage, the design can be expanded to an 8-port antenna configuration. In this approach, the original 4-port antenna, which shows strong backward radiation, can be complemented by a mirror image placed on the opposite side of the substrate, maintaining a specific separation distance. This mirrored four-port structure is naturally oriented to radiate in the forward direction due to its reversed current flow and structural symmetry. When both antennas are excited simultaneously by driving opposite ports from the mirrored pairs with a 180° phase shift—constructive interference occurs in both forward and backward directions, resulting in a symmetric bidirectional radiation pattern. This configuration not only enhances spatial coverage but also preserves the CP characteristics and isolation properties of the original design. Such a setup is particularly ideal for applications requiring uniform coverage on both sides of the antenna, such as vehicular communication or wall-mounted indoor access points.

4. Realization of Bidirectional Patterns Using Dual Four Port Antenna

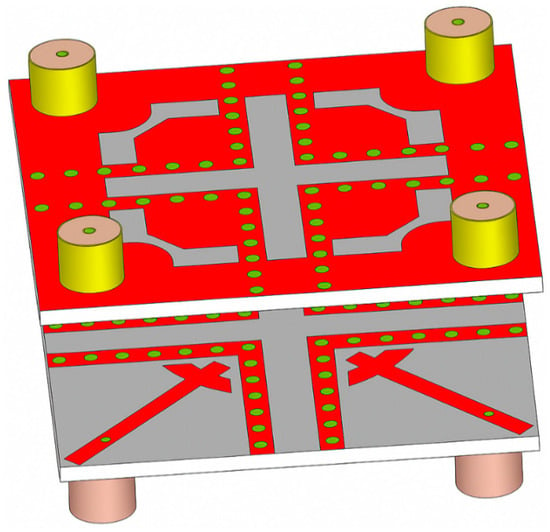

The optimized 4-port MIMO antenna (Design 6) primarily radiates into the backward hemisphere when excited at a single port. To address this limitation and enable a bidirectional radiation pattern, a novel approach was implemented. This involved creating a two-element antenna system using two identical 4-port antennas, one configured as a mirror image of the other. These two 4-port antenna elements are strategically separated by a distance of 15 mm, as illustrated in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Dual layer design setup for bidirectional radiation.

The lower antenna element corresponds to the original optimized Design 6, referred to as BRU, which inherently has its primary radiation lobe directed towards the backward hemisphere when excited individually. The upper antenna element is a precise mirror image of Design 6, designated as FRU. This mirrored configuration reverses the orientation of the current distribution and phase propagation relative to the global coordinate system. Therefore, when FRU is excited individually, its primary backward radiation is oriented in the opposite spatial direction compared to BRU. As a result, the backward radiation from each antenna effectively points in opposite directions within the overall system, allowing for enhanced bidirectional communication.

To synthesize a constructive bidirectional radiation effect with coherent field enhancement, a phase-controlled excitation scheme was applied. By exciting one port on BRU was driven with a 0° phase signal and a corresponding opposite port on FRU with a 180° phase, the electromagnetic fields radiated by each antenna combine coherently. It should be noted that the application of a 180° phase difference is an external excitation strategy and does not alter the intrinsic MIMO characteristics of the antenna. Each port in the BRU and FRU remains electrically independent. Consequently, the proposed antenna fully supports MIMO operation while enabling bidirectional radiation through controlled phase excitation.

The precise 15 mm separation between the antennas, combined with the applied 0° and 180° phase differences at the excited ports, is deliberately chosen to promote constructive interference in two opposing boresight directions. This combination of spacing and phase results in constructive interference that forms two distinct main lobes of equal magnitude, directed approximately 180° apart, while simultaneously suppressing radiation in undesired side lobe directions. This active phasing technique effectively transforms the individual, predominantly backward-radiating characteristics of the constituent antennas into a controlled bidirectional pattern for the combined design. This approach is particularly beneficial for applications that require communication in two opposing directions without the need for mechanical reorientation or additional reflective surfaces.

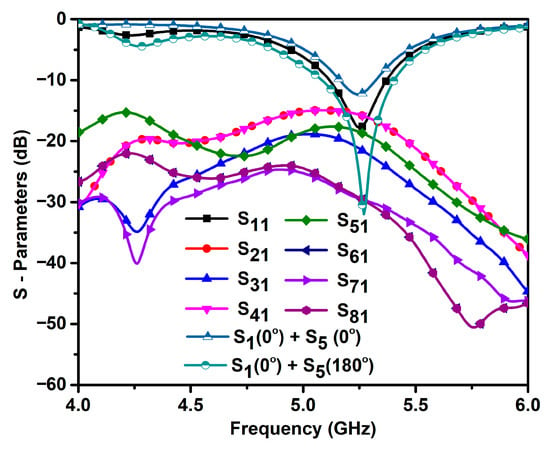

To understand the performance behavior of this design, the simulated S-parameters and radiation characteristics are analyzed. Figure 8 presents the simulated S-parameters for the two-layer antenna design. The reflection coefficient of the BRU (S11) at 5.2 GHz is approximately −20 dB, indicating effective impedance matching. Similarly, the impedance matching for the other primary excited port (S55) for a port on the FRU was tested individually and showed a comparable response due to symmetry, although S55 does not have a distinct resonant curve in this plot. Additionally, the consistently low coupling values observed between different ports demonstrate excellent inter-antenna isolation, attributed to the 15 mm separation between the two modules.

Figure 8.

Simulated S parameter comparison of dual layer antenna.

Furthermore, the performance of impedance matching for combined excitation under specific conditions for bidirectional pattern synthesis has been evaluated. When BRU port 1 and FRU port 5 are excited at a relative phase of 0°, the matching shows a slight decline across the operating frequency. In contrast, when these two ports are excited with a 180° phase difference, a significantly deeper resonance dip of approximately −30 dB is observed at 5.2 GHz. The noticeable and substantial difference between these two scenarios clearly demonstrates that exciting the two antenna modules with a 180° phase difference results in a far superior impedance match and resonant behavior compared to in-phase excitation. This finding effectively validates the chosen excitation strategy for achieving optimal electrical performance during the synthesis of the bidirectional pattern.

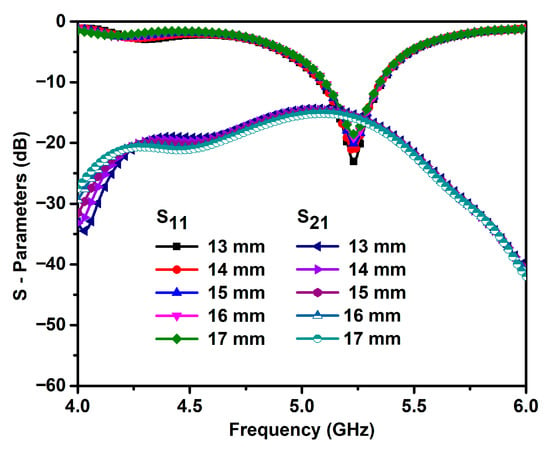

To further assess the robustness of the dual-module configuration, the effect of varying the air gap between the FRU and BRU was investigated. Figure 9 illustrates the simulated reflection coefficient and coupling coefficient for air-gap values ranging from 13 mm to 17 mm. It is observed that the resonance frequency remains centered around 5.2 GHz for all considered gap values. When the air gap is reduced to 13 mm, a deeper reflection minimum is obtained, indicating stronger electromagnetic interaction between the two modules. However, this configuration also results in relatively higher coupling, with isolation approaching −14 dB. As the air gap increases, the coupling level improves, reaching values close to −17 dB, while the reflection depth becomes slightly shallower. Based on this trade-off between impedance matching and inter-module isolation, an intermediate air gap of 15 mm is selected. These results demonstrate that the proposed passive spatial phasing architecture exhibits stable electromagnetic behavior and remains tolerant to practical fabrication and assembly variations. Consequently, the chosen 15 mm air gap represents an optimal and robust design choice for the dual-layer bidirectional CP-MIMO antenna system.

Figure 9.

Simulated S parameter comparison of dual layer antenna with the variation in air gap.

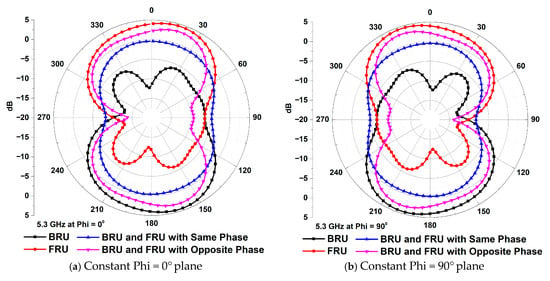

Furthermore, to explore the radiation behavior of the proposed dual-layer design, Figure 10 illustrates the simulated radiation patterns in the ϕ = 0° and ϕ = 90° planes at 5.2 GHz, highlighting the individual radiation characteristics of the BRU and FRU layers, along with their combined performance under different phasing conditions. The BRU shows the radiation pattern of the first optimized antenna module, corresponding to Design 6 when activated individually. As observed in the previous analysis of Design 6, this module naturally exhibits a backward-directed radiation pattern. On the other hand, the FRU represents the radiation pattern of the second antenna module, which is a mirrored version of Design 6. When excited individually, this module’s radiation is directed towards the broadside. This confirms that the mirror-image design effectively reorients the dominant radiation, making it suitable for complementary use in the overall design.

Figure 10.

Simulated radiation patterns of the BRU and FRU along with their combined performance under different phasing conditions.

The plot then compares the combined radiation patterns when both the FRU and the BRU designs are excited simultaneously. When the ports of both layers are fed with a 0° relative phase, their radiation patterns combine. However, this in-phase combination results in a pattern that is somewhat distributed and lacks a distinct, singular main lobe. Although there is a peak around θ = 0°, significant radiation occurs in other directions, including the backward hemisphere. This indicates that in-phase excitation does not produce a clean bidirectional pattern. The radiation becomes less directive and more diffused. This behavior is evident from the similar gain levels in the forward and backward directions, without a clearly defined primary beam.

In contrast, exciting the ports of both layers with a 180° phase difference enables the desired bidirectional radiation. This phase condition is critical for achieving the intended bidirectional effect. The plot clearly illustrates the synthesis of two distinct, well-defined main lobes. One is directed toward broadside (θ = 0°), and the other toward the backward direction (θ = 180°). The magnitudes of these two lobes are comparable, confirming balanced bidirectional radiation. Importantly, radiation in undesired side directions is significantly suppressed compared to both the individual elements and the combined same-phase case. This demonstrates effective constructive interference in the forward and backward directions. At the same time, destructive interference occurs in the orthogonal directions. This confirms the design’s ability to achieve controlled bidirectional radiation.

The bidirectional radiation behavior observed in the proposed dual-layer MIMO antenna system can be theoretically modeled using the classical array factor formalism, accounting for spatial separation and excitation phase control. The two identical radiating units namely the BRU and the FRU are symmetrically positioned along the z-axis at a separation distance d = 15 mm. The BRU and FRU ports that face opposite directions are simultaneously excited with equal amplitude but a 180° phase difference. This excitation strategy induces constructive interference in opposite spatial directions while suppressing off-axis radiation, enabling a well-defined bidirectional pattern. The resulting far-field radiation from the superposition of the BRU and FRU can be mathematically modeled using the array factor , which accounts for both phase and spatial contributions. For two identical sources separated by distance d along the z-axis and excited with a relative phase shift , the array factor is expressed using Equation (2) [8,52].

where θ is the observation angle with respect to the z-axis, is the effective phase constant, and λg is the effective guided wavelength corresponding to the center operating frequency. deff is the effective electrical separation between the phase centers of the BRU and FRU along the z-axis. Substituting Δϕ = π (180° phase shift), the expression simplifies to Equation (3).

The normalized power pattern is obtained by squaring the magnitude of the array factor and is given in Equation (4).

This equation indicates constructive maxima when , leading to constructive interference in directions in θ = 0° and θ = 180°, yielding symmetric main lobes in the forward and backward directions. Conversely, nulls are introduced when , which suppresses off-axis radiation and enhances pattern directivity. These phenomena collectively shape the unique bidirectional characteristics observed in simulation.

Crucially, the phase term depends on the effective propagation constant keff, which accounts for both the dielectric and air regions in the field propagation path between the two layers.

To model this accurately, the effective electrical length deff of the path between the phase centers of the two elements must include contributions from both the dielectric and air sections. Assuming negligible field bending at the dielectric-air interface, the total effective spacing is approximated using Equation (5).

where dair is the separation between the two layers, and tFR4 is the thickness of each substrate in the design. Consequently, the effective guided wavelength λg at the design frequency is used to compute the effective propagation constant using Equation (6).

The effective guided wavelength λg is calculated based on the composite medium. For FR-4 (εr ≈ 4.4) and air, the overall effective permittivity εeff across the path is approximated using Equation (7).

Based on the above analysis, the final phase term is crucial in shaping the far-field interference pattern, which inherently forms a bidirectional beam aligned along the ±z directions. The mirror-image configuration of the units ensures that their individual field patterns E0(θ) are spatially aligned to complement each other in opposite directions. Thus, when one port radiates toward +z, the mirrored counterpart inherently favors −z, and the phase-inverted excitation ensures constructive interference in both directions. The resulting total field pattern is expressed using Equation (8).

This formulation clearly captures how the imposed 180° phase difference and the physical spacing between the units constructively reinforce radiation along both boresight directions, forming a symmetrical bidirectional pattern.

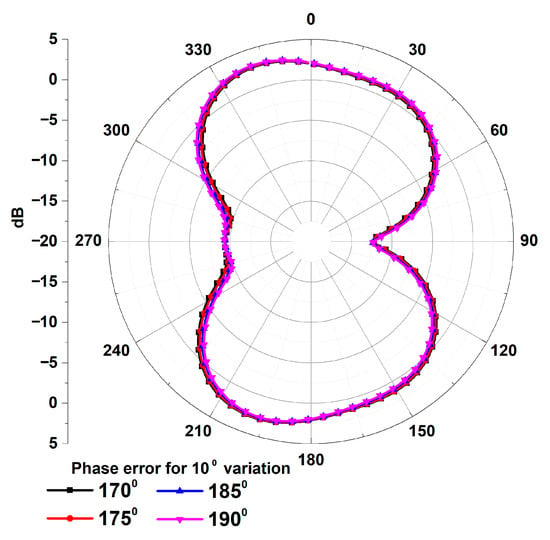

To evaluate the sensitivity of the proposed bidirectional radiation mechanism to phase errors, a phase-tolerance analysis was performed by varying the relative excitation phase difference between the BRU and FRU modules from 170° to 190°, in steps of 5°, around the nominal 180° condition. The resulting radiation patterns are shown in Figure 11. It indicates that the fundamental bidirectional radiation characteristic is preserved across the considered phase range. As the phase deviates from 180°, the main lobes in the forward and backward directions remain stable. This behavior is consistent with array-factor theory, where small phase perturbations primarily affect pattern symmetry rather than beam existence. The results confirm that the proposed passive spatial phasing approach is robust to practical phase errors within ±10°, which are commonly encountered in real RF feeding networks. This robustness further supports the feasibility of the proposed design for practical V2X and bidirectional communication systems.

Figure 11.

Radiation patterns of the BRU and FRU against phase errors of ±10°.

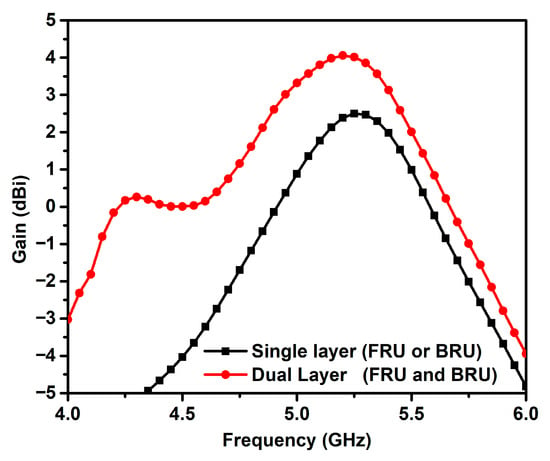

Further, the gain performance of the combined dual layer is a critical indicator of its overall effectiveness in directing radiated power. Figure 12 illustrates a comparative analysis of the simulated total realized gain across the frequency band for the individual single-layer 4-port antenna, corresponding to Design 6, versus the combined dual-layer 8-port antenna. The gain of a single, isolated 4-port antenna shows its gain peaking around 2.5 dBi at approximately 5.2 GHz, confirming its effective power radiation in a specific direction. The combined dual-layer 8-port antenna achieves significantly higher gain compared to a single-layer antenna. The dual-layer antenna exhibits a peak realized gain of approximately 4.2 dBi at around 5.2 GHz. This increase in gain is approximately 1.7 dBi higher at peak compared to a single layer. The increase in gain is achieved because the individual elements’ radiation that is one backward and one effectively forward are precisely phased and spaced to constructively sum their power in these two desired opposing directions, thereby concentrating the total radiated energy more effectively than a single element alone.

Figure 12.

Simulated realized gain comparison of either FRU or BRU and a dual-layer antenna.

5. Experimental Validation

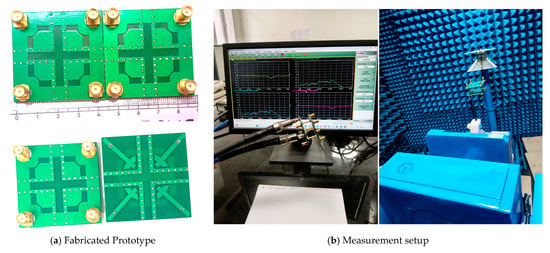

To validate the simulated characteristics of the proposed circularly polarized MIMO antenna system, a physical prototype of the dual four-port configuration was fabricated, as shown in Figure 13a. The top and bottom views of the fabricated antenna structure reveal the key design features, including cross-shaped ground plane apertures, the diagonal annular segment feed arms, and the surrounding via arrays. The printed scale beneath the prototypes confirms dimensional adherence, where each unit is approximately 44 mm × 44 mm, corresponding to the optimized simulated layout. The prototype measurement setup is illustrated in Figure 13b. Mechanical alignment and inter-layer separation were maintained using dielectric spacers to ensure accurate structural stacking. The measured reflection coefficients and transmission coefficients were obtained, including those from individual 4-port FRU and BRU modules, as well as the combined bidirectional array. The FRU and BRU refer to two identical yet mirror-oriented four-port antenna layers. Additionally, these units were excited independently to analyze their AR, realized gain, and radiation patterns across the intended operational band.

Figure 13.

Prototype of the dual four-port configuration and measurement analysis.

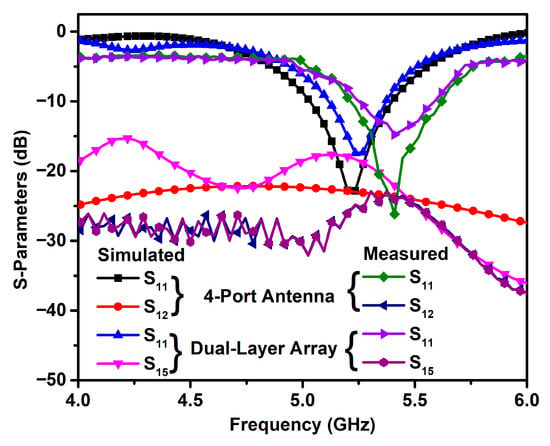

Figure 14 illustrates a comprehensive comparison between the simulated and experimentally measured S-parameters for both the optimized single 4-port antenna (FRU or BRU) and the combined dual-layer array. For the single 4-port antenna, the simulated S11 exhibits a resonance dip at 5.25 GHz. However, the measured S11 for this configuration shows a resonance dip at 5.41 GHz. Similarly, for the dual-layer array, the simulated S11 demonstrates good matching at approximately 5.3 GHz, whereas the measured S11 for the array is approximately 5.4 GHz. Such discrepancies can be attributed to various factors, including inherent fabrication tolerances, slight differences in the actual dielectric constant or loss tangent of the FR-4 substrate from nominal values, and parasitic effects introduced by coaxial connectors and soldering points that are challenging to model perfectly in simulation. Despite the slight measured resonance deviation, the antenna maintains an acceptable impedance match for both configurations.

Figure 14.

S-Parameter of a single 4-port (BRU) and dual-layer antenna comparison.

Beyond reflection, the simulated transmission coefficient (S12) for the 4-port antenna demonstrates excellent isolation, consistently remaining below −22 dB across the band, with a value of approximately −22.96 dB at 5.25 GHz. Notably, the measured S12 for this configuration shows remarkable agreement, also achieving approximately −24.97 dB at 5.25 GHz. This strong correlation between simulated and measured intra-antenna isolation provides robust experimental validation for the effectiveness of the integrated decoupling mechanisms in minimizing mutual coupling between ports within each 4-port module. Furthermore, the plot assesses the inter-antenna isolation (S15) between the two distinct 4-port modules of the dual-layer array. The simulated S15 indicates excellent inter-antenna isolation, consistently remaining below −17 dB across the band, with a value of approximately −19 dB at 5.3 GHz. Interestingly, the measured S15 for the dual-layer array demonstrates even better isolation than the simulated results, achieving approximately −24 dB at 5.4 GHz. This positive deviation in measured isolation is advantageous and could be attributed to subtle variations in the actual 15 mm separation distance between the layers in the fabricated prototype, which might have inadvertently optimized the destructive interference of coupled fields, or minor differences in material properties leading to enhanced decoupling.

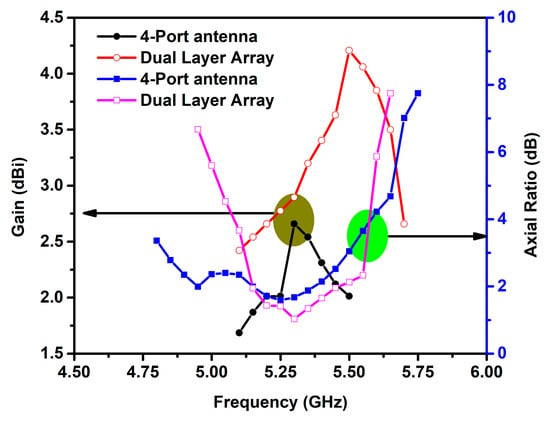

Following the S-parameter characterization, the performance of the fabricated antenna prototypes was further validated through standard measurements of AR, Realized Gain, and radiation patterns in a controlled anechoic chamber environment. The antenna under test (AUT) was mounted on a rotatable positioner and subjected to full 360° rotations to capture the co-polarized and cross-polarized field components, essential for AR calculation. Figure 15 illustrates the measured AR performance for both the single 4-port antenna and the dual-layer array. For the 4-port antenna, the measured AR values consistently remained below 3 dB from 5.1 GHz to 5.45 GHz, yielding a usable AR bandwidth of approximately 350 MHz. On the other hand, the dual-layer array demonstrates a slightly narrower but notably flatter AR profile, maintaining AR below 3 dB within its measured operating band from 5.25 GHz to 5.55 GHz, corresponding to an AR bandwidth of approximately 300 MHz. These measured AR values, consistently below the 3 dB threshold, experimentally validate the capability of both the single module and the dual-layer structure to preserve polarization purity, even with enhanced radiation characteristics, confirming the reliability of the design’s CP-generating features.

Figure 15.

Measured gain and AR of 4-port (BRU) and dual-layer antenna comparison.

Concurrently, the total realized gain of the fabricated antenna modules was measured in the anechoic chamber using the gain comparison method. Figure 15 also presents the realized gain for both configurations. For the individual 4-port antenna, the measured peak realized gain was found to be 2.6 dBi at 5.3 GHz. This measured gain exhibits close agreement with the previously simulated gain values, with only a small frequency deviation. For the dual-layer array, the measured peak realized gain was significantly higher, reaching approximately 4.2 dBi at 5.5 GHz. This improvement is attributable to the interference and increased aperture area resulting from the spatial combination of two mirrored 4-port antennas separated by a 15 mm dielectric spacer. This gain enhancement, combined with stable AR performance, validates the dual-layer design’s superiority in applications requiring higher radiation efficiency under practical implementation.

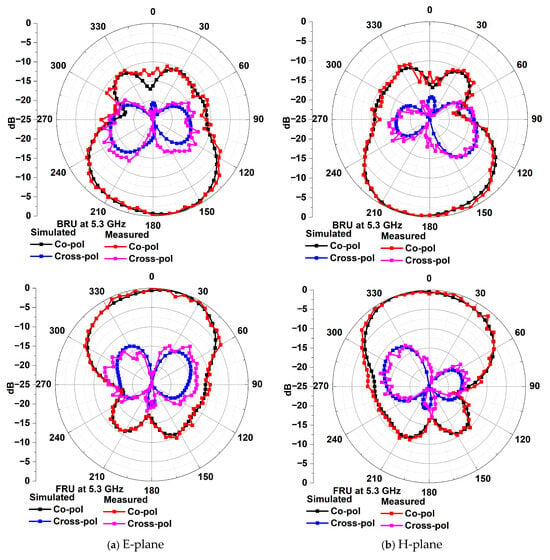

The spatial radiation characteristics of the individual antenna modules were measured and compared with simulations. Figure 16 displays the simulated and measured radiation patterns in both the E-plane and H-plane at 5.3 GHz for both the BRU and the FRU. For both the BRU and the FRU, the measured radiation patterns demonstrate close agreement with their respective simulated patterns. Specifically, the BRU predominantly radiates in the backward direction, while the FRU exhibits forward-directed radiation. Both units consistently showcase a stable pattern shape and good front-to-back discrimination. This strong correspondence between simulated and measured radiation patterns for both individual units provides compelling experimental evidence validating the accuracy of the electromagnetic models and the successful re-orientation of radiation through the mirror-image design. A direct comparison between the reconstructed measured patterns and the simulated results further confirms that the cross-polarization level remains more than 15 dB below the co-polarization peak in the main radiation direction. This behavior is consistent across the operating band and is further validated by the measured axial-ratio performance.

Figure 16.

Radiation Pattern Comparison of BRU and FRU.

However, due to the unavailability of a precise 180-degree phase shift source within the experimental setup at the time of measurement, the combined radiation pattern of the two-element array, which is excited with 0° and 180° phase difference for bidirectional operation, could not be directly measured. Achieving accurate phase control at 5.3 GHz for multiple ports necessitates specialized phase shifters and a multi-channel VNA or dedicated test equipment, which was not accessible. Consequently, the successful individual characterization of the BRU and FRU, along with the confirmed high inter-antenna isolation, provides strong indirect evidence that the simulated bidirectional pattern as shown in Figure 10 for combined same and opposite phase would be accurately realized under ideal phased excitation. This confirms that the dual-layer architecture, composed of mirror-image arrays with controlled spacing and excitation phase shift, effectively enables bidirectional radiation. This capability is especially useful in systems that demand spatial diversity or beam-switching functionality.

Table 1 presents a comparative summary of recently reported MIMO and array antennas alongside the proposed work. From the comparison, it is observed that most existing designs focus on unidirectional or endfire radiation with either linear or circular polarization, whereas the proposed antenna uniquely combines multi-port circular polarization with bidirectional radiation and high isolation within a compact footprint in the sub-6 GHz band. This highlights the distinct contribution of the proposed dual 4-port CP-MIMO antenna in achieving controlled bidirectional coverage without complex feeding or reconfigurable structures.

Table 1.

Performance comparison of MIMO and array antennas with the proposed bidirectional CP-MIMO antenna.

6. Conclusions

This work presents a comprehensive design, optimization, and experimental validation of a dual 4-port circularly polarized MIMO antenna based on SIW technology for bidirectional radiation in the 5 GHz band. A systematic multi-stage optimization strategy incorporating DGS, decoupling strips, and vertical SIW vias across six progressive design stages has resulted in significant improvements in impedance matching, mutual coupling suppression, and polarization stability. Two mirror-symmetric 4-port antenna elements, such as the BRU and FRU, are arranged with a 15 mm air gap and excited under a 180° phase condition. This configuration produces symmetrical radiation along opposing boresight directions, effectively reorienting the beam while preserving CP. This bidirectionality has the potential to support a two-fold increase in V2X system capacity by exploiting two spatially opposed domains without increasing the antenna footprint. Prototype fabrication and experimental validation revealed a strong alignment with simulation data. Experimental measurements closely align with simulated results, and the fabricated prototype exhibits strong inter-layer isolation better than −24 dB, validating the robustness of the proposed design. Although direct measurement of the combined bidirectional radiation patterns under 180° phase excitation was limited by the availability of phase-shifting instrumentation at 5.3 GHz. In addition, the use of an FR-4 substrate introduces dielectric loss constraints that may limit scalability toward higher-frequency bands. The presented passive spatially phased architecture is particularly attractive for applications requiring seamless two-way communication, including vehicular networks, dual-sided indoor access points, and wall-mounted IoT infrastructure. Future work will focus on integrating this SIW framework with compact circularly polarized dual-band modified patch elements to enhance spectral agility, as well as exploring dynamic phase control, beam switching, and hybrid integration with frequency-selective surfaces.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.D. and M.S.; methodology, K.D.; software, K.D.; validation, K.D. and M.S.; formal analysis, K.D., S.P. and J.K.; investigation, K.D., S.P. and J.K.; resources, K.D. and M.S.; data curation, S.P. and J.K.; visualization, K.D. and M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, K.D. and M.S.; writing—review and editing, K.D., M.S., S.P. and J.K.; supervision, M.S.; project administration, K.D.; funding acquisition, K.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Where no new data were created.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Malviya, L.; Panigrahi, R.K.; Kartikeyan, M.V. MIMO Antennas for Wireless Communication: Theory and Design; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, P.; Malhotra, S.; Sharma, M. A review of isolation techniques for 5G MIMO antennas. J. Telecommun. Inf. Technol. 2024, 3, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molisch, A.F.; Win, M.Z. MIMO Systems with Antenna Selection—An Overview; Mitsubishi Electric Research Laboratories: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari, P.; Gahlaut, V.; Kaushik, M.; Shastri, A.; Arya, V.; Elfergani, I.; Zebiri, C.; Rodriguez, J. Enhancing performance of millimeter-wave MIMO antenna with a decoupling and common defected ground approach. Technologies 2023, 11, 142. [Google Scholar]

- Chataut, R.; Akl, R. Massive MIMO systems for 5G and beyond networks—Overview, recent trends, challenges, and future research directions. Sensors 2020, 20, 2753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, X.; Jia, Y.; Guo, Y.J. A low correlation and mutual coupling MIMO antenna. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 127384–127392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, J.G.; Buzzi, S.; Choi, W.; Hanly, S.V.; Lozano, A.; Soong, A.C.K.; Zhang, J.C. What will 5G be? IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2014, 32, 1065–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balanis, C.A. Antenna Theory: Analysis and Design; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Valenzuela-Valdes, J.F.; Garcia-Fernandez, M.A.; Martinez-Gonzalez, A.M.; Sanchez-Hernandez, D. The role of polarization diversity for MIMO systems under Rayleigh-fading environments. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 2006, 5, 534–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, R.F. Time-Harmonic Electromagnetic Fields; Wiley–IEEE Press: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A.; Rana, S.; Srivastava, G.; Mohan, A.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, O.P. A highly decoupled and compact co-circularly polarized MIMO filtering antenna array system for vehicular communications. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 42531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kollipara, V.; Peddakrishna, S. Circularly polarized antennas using characteristic mode analysis: A review. Adv. Technol. Innov. 2022, 7, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, S.; Anitha, R.; Deepak, U.; Aanandan, C.K.; Mohanan, P.; Vasudevan, K. A compact tri-band dual-polarized corner-truncated sectoral patch antenna. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2015, 63, 5842–5845. [Google Scholar]

- İmeci, T.; Saral, A. Corners truncated microstrip patch antenna. In Proceedings of the 26th Annual Review of Progress in Applied Computational Electromagnetics, Tampere, Finland, 26–29 April 2010; pp. 26–29. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, K.-L. Compact and Broadband Microstrip Antennas; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Muntoni, G.; Casula, G.A.; Traversari, M.; Montisci, G. A wideband single-feed circularly polarized stacked patch antenna. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 103380–103387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanaujia, B.K.; Kumar, S.; Khandelwal, M.K.; Gautam, A.K. Single-feed L-slot microstrip antenna for circular polarization. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2015, 85, 2041–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Xu, G.; Ren, A.; Wang, W.; Huang, Z.; Wu, X. A compact dual-band dual-circularly polarized SIW cavity-backed antenna array for millimeter-wave applications. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 2022, 21, 1572–1576. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Y.; Dong, Y. Wideband circularly polarized planar antenna array for 5G millimeter-wave applications. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2020, 69, 2615–2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raoof, K.; Zid, M.B.; Prayongpun, N.; Bouallegue, A. Advanced MIMO techniques: Polarization diversity and antenna selection. In MIMO Systems: Theory and Applications; InTech: Toulon, France, 2011; pp. 1–54. [Google Scholar]

- Nadeem, I.; Choi, D.-Y. Study on mutual coupling reduction technique for MIMO antennas. IEEE Access 2018, 7, 563–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Xu, J.; Xu, Q. Reduction of mutual coupling between closely packed antenna elements using defected ground structure. In Proceedings of the 2009 3rd IEEE International Symposium on Microwave, Antenna, Propagation and EMC Technologies for Wireless Communications, Beijing, China, 27–29 October 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Misran, M.H.; Meor Said, M.A.; Othman, M.A.; Jaafar, A.S.; Abd Manap, R.; Suhaimi, S.; Hassan, N.I. DGS-based circularly polarized antenna for 5G communication with harmonic suppression. Int. J. Integr. Eng. 2024, 16, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajit, K.; Singh, S.; Kumar, M.; Rashmi, S. Compact super-wideband MIMO antenna with improved isolation for wireless communications. Frequenz 2021, 75, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, A.J.; Das, N.; Salehin, S.; Chakraborty, S.; Pranta, S.; Alam, S.U. Design and performance analysis of a compact two-port circularly polarized MIMO antenna for sub-6 GHz 5G applications. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Power, Electrical, Electronics and Industrial Applications (PEEIACON), Rajshahi, Bangladesh, 12–13 September 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Milias, C.; Andersen, R.B.; Lazaridis, P.I.; Zaharis, Z.D.; Muhammad, B.; Kristensen, J.T.B.; Mihovska, A.; Hermansen, D.D.S. Metamaterial-inspired antennas: A review of the state of the art and future design challenges. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 89846–89865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Wang, J.-W. Neutralization-line-based decoupling for miniaturized MIMO antenna array. Microw. Opt. Technol. Lett. 2023, 65, 685–689. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, I.; Wu, Q.; Ullah, I.; Rahman, S.U.; Ullah, H.; Zhang, K. Designed circularly polarized two-port microstrip MIMO antenna for WLAN applications. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, H.; Jamaluddin, M.H.; Seman, F.C.; Rahman, M. MIMO dielectric resonator antennas for 5G applications: A review. Electronics 2023, 12, 3469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, W.; Jiang, Z.H.; Yu, C.; Zhou, J.; Chen, P.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Yang, B.; Pang, X.; Jiang, M.; et al. Multibeam antenna technologies for 5G wireless communications. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2017, 65, 6231–6249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natkaniec, M.; Bieryt, N. An Analysis of the Mixed IEEE 802.11ax Wireless Networks in the 5 GHz Band. Sensors 2023, 23, 4964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saeidi, T.; Saleh, S.; Timmons, N.; McDaid, C.; Al-Gburi, A.J.A.; Razzaz, F.; Karamzadeh, S. High-gain miniaturized multi-band MIMO SSPP LWA for vehicular communications. Technologies 2025, 13, 66. [Google Scholar]

- Saxena, S.; Tewari, N.; Srivastava, S. A spiral cavity-backed 4 × 4 MIMO SIW antenna at Ku-band for radio telescopes. Prog. Electromagn. Res. M 2025, 132, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, P.; Das, S. A wideband circularly polarized SIW MIMO antenna based on coupled QMSIW and EMSIW resonators for sub-6 GHz 5G applications. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 2024, 23, 2979–2983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.-Q.; Qiu, F.; Jiang, C.; Lei, D.; Tang, Z.; Yao, M.; Chu, Q.-X. Compact circularly polarized SIW cavity-backed antenna based on slot SRR. In Proceedings of the 2015 Asia-Pacific Microwave Conference (APMC), Nanjing, China, 6–9 December 2015; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gharaati, A.; Ghaffarian, M.S.; Saghlatoon, H.; Behdani, M.; Mirzavand, R. A low-profile wideband circularly polarized CPW slot antenna. AEU–Int. J. Electron. Commun. 2021, 129, 153534. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, C.; Ma, Z.-H.; Zhang, X. Millimeter-wave circularly polarized array antenna using substrate-integrated gap waveguide sequentially rotating phase feed. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 2019, 18, 1124–1128. [Google Scholar]

- Pramodini, B.; Chaturvedi, D.; Darsi, L.; Rana, G. Optimized compact MIMO antenna design: HMSIW-based and cavity-backed for enhanced bandwidth. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 189820–189828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Dwari, S. Compact four-element MIMO SIW cavity-backed slot antenna with high front-to-back ratio. Int. J. RF Microw. Comput.-Aided Eng. 2019, 29, e21512. [Google Scholar]

- Anandan, R.; Balasubramanian, S.; Sanapala, R.K.; Kamisetti, P. Metamaterial-loaded circularly polarized quad-band SIW MIMO antenna with improved gain for sub-6 GHz and X-band applications. Appl. Comput. Electromagn. Soc. J. 2025, 40, 724–733. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, R.; Khanna, R.; Kapur, G. Design of metamaterial loaded wideband sub-6 GHz 2 × 1 MIMO antenna with enhanced isolation using characteristic mode analysis. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2024, 134, 1713–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, J.K.; Gupta, A.; Sharma, G.S. Al2O3 ceramic-based swastika-shaped quad-port MIMO antenna for 5.9 GHz ITS applications. AEU–Int. J. Electron. Commun. 2025, 202, 156052. [Google Scholar]

- Kumari, E.K.; Szymański, J.R.; Żurek-Mortka, M.; Sathiyanarayanan, M. A novel high-isolation quad-port multiband MIMO antenna for V2X applications at sub-6 GHz band. Frequenz 2025, 79, 385–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.; Kim, D.W.; Na, S.W.; Kim, J.D.; Park, W.K. Design of a bidirectional antenna inside a vehicle and measurement of power link for vehicle-to-vehicle communication at 5.8 GHz. Int. J. Antennas Propag. 2018, 6306273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Niu, Z.; Wang, Y. An electrically small antenna with a bidirectional radiation pattern for UHF RFID tags. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Microwave and Millimeter Wave Technology (ICMMT), Chengdu, China, 7–11 May 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, T.; Xu, M.; Lu, H.; Cai, X. A printed dipole array with bidirectional endfire radiation for tunnel communication. Sensors 2023, 23, 9137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honma, N.; Nishimori, K.; Takatori, Y.; Ohta, A.; Kubota, S. Proposal of compact MIMO terminal antenna employing Yagi–Uda array with common director elements. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE Antennas and Propagation Society International Symposium, Honolulu, HI, USA, 9–15 June 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sarrazin, J.; Mahe, Y.; Avrillon, S.; Toutain, S. Investigation on cavity/slot antennas for diversity and MIMO systems: The example of a three-port antenna. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 2008, 7, 414–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohani, B.; Takahashi, K.; Arai, H.; Kimura, Y.; Ihara, T. Improving channel capacity in indoor 4 × 4 MIMO base station utilizing small bidirectional antenna. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2017, 66, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awan, W.A.; Abbas, A.; Choi, D.; Hussain, N.; Lee, H.; Sim, D.; Kim, N. Compact and directional dual-band antenna with low mutual coupling MIMO configuration for mm-wave communication. Results Eng. 2025, 26, 105457. [Google Scholar]

- Kollipara, V.; Peddakrishna, S. Quad-port circularly polarized MIMO antenna with wide axial ratio. Sensors 2022, 22, 7972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pozar, D.M. Considerations for millimeter-wave printed antennas. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2003, 31, 740–747. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.