Abstract

The grid-forming static var generator (SVG) is a key device that supports the stable operation of power grids with a high penetration of renewable energy. The cooling efficiency of its forced water-cooling system directly determines the reliability of the entire unit. However, existing wired monitoring methods suffer from complex cabling and limited capacity to provide a full perception of the water-cooling condition. To address these limitations, this study develops a wireless monitoring system based on multi-source information fusion for real-time evaluation of cooling efficiency and early fault warning. A heterogeneous wireless sensor network was designed and implemented by deploying liquid-level, vibration, sound, and infrared sensors at critical locations of the SVG water-cooling system. These nodes work collaboratively to collect multi-physical field data—thermal, acoustic, vibrational, and visual information—in an integrated manner. The system adopts a hybrid Wireless Fidelity/Bluetooth (Wi-Fi/Bluetooth) networking scheme with electromagnetic interference-resistant design to ensure reliable data transmission in the complex environment of converter valve halls. To achieve precise and robust diagnosis, a three-layer hierarchical weighted fusion framework was established, consisting of individual sensor feature extraction and preliminary analysis, feature-level weighted fusion, and final fault classification. Experimental validation indicates that the proposed system achieves highly reliable data transmission with a packet loss rate below 1.5%. Compared with single-sensor monitoring, the multi-source fusion approach improves the diagnostic accuracy for pump bearing wear, pipeline micro-leakage, and radiator blockage to 98.2% and effectively distinguishes fault causes and degradation tendencies of cooling efficiency. Overall, the developed wireless monitoring system overcomes the limitations of traditional wired approaches and, by leveraging multi-source fusion technology, enables a comprehensive assessment of cooling efficiency and intelligent fault diagnosis. This advancement significantly enhances the precision and reliability of SVG operation and maintenance, providing an effective solution to ensure the safe and stable operation of both grid-forming SVG units and the broader power grid.

1. Introduction

The construction of a new-type power system dominated by renewable energy sources is a key measure for achieving the national “dual carbon” goal of carbon peaking and carbon neutrality [1]. However, the large-scale integration of renewable energy significantly reduces the inertia and damping of the grid, posing severe challenges to its operational stability [2]. Against this background, grid-forming (GFM) converter technology has emerged as a crucial foundation for ensuring the future stability of renewable dominated power systems [3,4].

As a core component within this technical framework, the grid-forming static var generator (SVG) operates on advanced converter control strategies [5]. Beyond its traditional role in reactive power compensation, the SVG—through a virtual synchronous machine (VSM) control concept—actively establishes voltage and frequency references for the grid [6]. This capability provides synthetic inertia and damping support that are indispensable in renewable energy grids with high penetration levels.

To achieve high-power density and compact system design, large capacity grid-forming SVGs commonly employ forced water-cooling systems to dissipate heat from critical components such as insulated gate bipolar transistors (IGBTs) [7,8]. The cooling efficiency of these systems directly determines the junction temperature of the power devices, thereby influencing output capability, operational lifetime, and overall reliability [9,10].

Any reduction in cooling efficiency—caused by pump degradation, pipeline blockage, or fluid leakage—may result in a rapid increase in the device junction temperature. Such overheating can lead to permanent IGBT damage or even trigger system trips, which would compromise the SVG’s grid supporting function and threaten the stability of the regional power network [11,12]. Therefore, real-time and accurate monitoring and assessment of the water-cooling system’s performance are of great engineering and research significance for ensuring the long-term reliability of grid-forming SVG equipment.

2. Related Research

In recent years, research on the monitoring of cooling systems in power electronic equipment has achieved notable progress. Conventional approaches mainly rely on a limited number of wired sensors combined with periodic manual inspections [13,14]. For example, temperature sensors are typically used to measure the inlet and outlet temperatures of cooling media, or flowmeters are employed to record coolant flow rates. However, wired monitoring systems face inherent drawbacks in complex converter valve environments, including complicated cabling, high installation costs, and poor scalability [15]. Manual inspection methods also suffer from poor real-time performance and an inability to capture gradual or intermittent faults [16].

Moreover, cooling efficiency represents a comprehensive indicator of thermal performance, and single-parameter monitoring (such as temperature alone) cannot fully describe the cooling system’s operational condition. Early faults—such as abnormal vibrations caused by pump bearing wear, acoustic anomalies generated by pipeline bubbles or partial blockages, and minor leaks due to aging joints—are often subtle and cannot be effectively detected through traditional monitoring means [17,18].

In recent years, wireless sensor networks (WSNs) combined with multi-source information fusion techniques have provided new solutions to overcome these limitations [19,20]. Owing to their flexible deployment, cost efficiency, and extensive sensing coverage, WSNs have been widely applied in power systems and industrial equipment monitoring. Their proven reliability in complex environments—particularly in sensor node layout, communication protocol design, and electromagnetic interference suppression—provides valuable insights for the monitoring of SVG water-cooling systems [21,22].

Xiangyang Xu et al. [23] developed a ZigBee-based temperature monitoring system for abnormal heating in distribution networks. Temperature sensors were installed at key points such as switches and cable joints, and the ZigBee network’s low power consumption and flexible topology enabled efficient wireless data transmission and centralized monitoring, effectively addressing the wide distribution of detection points in power networks.

The extensive application of WSNs in substation operation and equipment monitoring further demonstrates their adaptability in highly electromagnetic environments. Pengfei Liu et al. [24] proposed a wireless communication-based fault maintenance system for substation operations, achieving real-time monitoring of transformers and circuit breakers in a 220 kV substation. By integrating Wi-Fi and an IEEE 802.15.4e-based wireless mesh network with multi-antenna MIMO technology [25], the system optimized signal coverage and improved communication stability under strong electromagnetic interference. The design experience regarding communication protocol selection, anti-interference strategies, and adaptation to industrial equipment provides important references for building reliable WSN architectures in SVG valve hall environments.

The practical application of multi-source information fusion in equipment condition monitoring has demonstrated its essential value in enhancing diagnostic accuracy. This approach is particularly effective in addressing the limitations of high false alarm rates and incomplete analysis that often occur in single-sensor systems [26,27]. Such methods provide both algorithmic and structural guidance for implementing multi-physics information fusion in the monitoring of SVG water-cooling systems.

In the field of industrial equipment monitoring, Zhaojianwei [28] proposed a remote monitoring solution for an externally cooled gearbox system, which clearly illustrates the practical advantages of multi-source data fusion in cooling performance assessment. The system integrates four categories of sensors—temperature, oil pressure, flow, and vibration. Data are preprocessed using Kalman filtering combined with a moving average filter to remove noise and outliers. Subsequently, a weighted average fusion method is applied to combine the multi-parameter measurements. By analyzing variations in oil temperature trends and pressure stability, the overall operational state is comprehensively evaluated.

Experimental results show that the monitoring errors for temperature and pressure are kept within ±0.5 °C and ±0.01 MPa, respectively, which is a substantial improvement compared with single-parameter monitoring. This research provides valuable insights for applying multi-source fusion—combining acoustic, hydraulic, flow, and vibration information—in the SVG water-cooling system.

Although previous studies have achieved promising progress, several evident gaps remain. First, most existing research has focused on rotating machinery or transformer monitoring. Wireless monitoring dedicated to grid-forming SVG water-cooling systems has not yet been systematically investigated. The unique strong electromagnetic interference (EMI) environment of SVG valve halls imposes exceptionally stringent requirements on the reliability of wireless communication [29].

Second, many existing approaches concentrate on single fault modes or single physical domains [30,31]. There is still a lack of an integrated framework that takes cooling efficiency as a comprehensive evaluation target while combining multi-dimensional information—including thermal, acoustic, vibration, and visual data—for collaborative perception and fault diagnosis. Accurately characterizing the gradual degradation of cooling efficiency through multi-source data and pinpointing the root cause of faults remain the key challenges [32,33].

To address these issues, this paper designs and implements a multi-source fusion-based wireless monitoring system tailored for the water-cooling system of grid-forming SVGs. The main contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

(1) A heterogeneous wireless sensor network integrating liquid-level, vibration, acoustic, and infrared sensors is developed. An anti-interference communication and deployment strategy is designed for the valve hall’s EMI-intensive environment, ensuring reliable acquisition and stable transmission of multi-physics information within the cooling system.

(2) A multi-source information fusion-based fault diagnosis algorithm is proposed. By combining temperature, liquid-level, vibration, acoustic, and visual signals, the method enables early detection and root-cause identification of faults such as pump anomalies, pipeline blockage or leakage, and radiator performance degradation. This provides an effective solution for the predictive maintenance of grid-forming SVG systems.

3. Design of Wireless Data-Acquisition System for Cooling Efficiency in Grid-Forming SVG

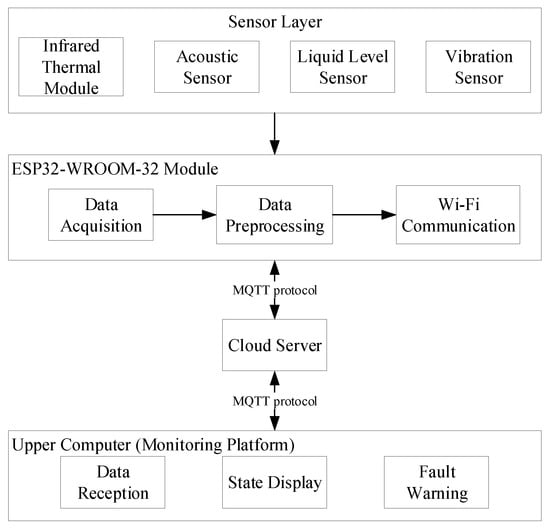

The overall architecture of the wireless monitoring system for the cooling efficiency of the grid-forming static var generator (SVG) is illustrated in Figure 1. The system integrates four primary types of sensors—liquid-level, vibration, infrared thermal, and acoustic sensors—to achieve comprehensive monitoring and early detection of abnormalities within the water-cooling system.

Figure 1.

Architecture of the wireless monitoring system for cooling efficiency in the grid-forming SVG.

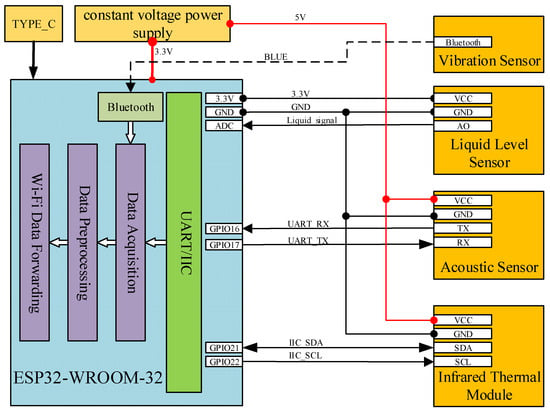

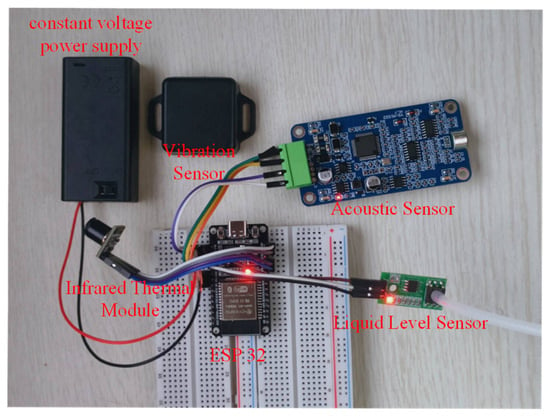

The proposed system is primarily composed of an ESP32 module (Espressif Systems (Shanghai) Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), an acoustic (sound pattern) sensor (Guangzhou Yingsheng Electronic Technology Co., Ltd., Guangzhou, China), a vibration sensor module (Shenzhen Weite Intelligent Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China), a liquid-level sensor (Fu’an Stein Electronic Technology Co., Ltd., Fu’an (Ningde City, Fujian Province), China), and an infrared thermal sensor (Shenzhen Yuekeyuanxing Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China), as shown in Figure 2. The ESP32 module serves as the core controller of the system, featuring high processing capability and multiple communication interfaces. It integrates both Wi-Fi and Bluetooth functions, enabling dual-mode wireless data transmission that provides a reliable and flexible means of communication. Through these wireless links, the collected data are rapidly transmitted to a local edge-computing node, where large-scale data storage and in-depth analysis can be performed.

Figure 2.

Hardware connection diagram of the grid-forming SVG water-cooling efficiency wireless monitoring system.

The acoustic sensor is installed near critical components of the grid-forming SVG water-cooling system, such as the water pump and the radiator. It continuously captures sound signals generated during operation. Different fault conditions—such as pump bearing wear or radiator blockage—introduce characteristic changes in both sound-frequency and sound-pressure levels, offering valuable acoustic features for early fault diagnosis.

The vibration sensor module is employed to monitor the vibration conditions of components in the water-cooling system, measuring parameters such as vibration velocity and displacement in real time. The liquid-level sensor, mounted on the coolant tank, accurately detects the coolant level and provides essential data for evaluating fluid reserve and circulation performance.

The infrared thermal sensor utilizes infrared thermography to continuously observe the temperature distribution of key components within the cooling system. It generates thermal images that visually illustrate surface temperature variations. By analyzing the temperature distribution patterns and differences, in combination with the heat-exchange characteristics of critical components, the system can perform both cooling efficiency assessment and fault localization effectively.

4. Testing of the Wireless Data-Acquisition System for Cooling Efficiency

This section presents detailed testing and analysis procedures for the vibration, liquid-level, infrared, and acoustic sensors.

4.1. Vibration Data

The grid-forming SVG cooling system operates under complex working conditions, where vibration in key internal components has a significant impact on both cooling efficiency and equipment stability. Hence, the accurate acquisition of vibration data is crucial. The water pump, as the driving core of coolant circulation, generates varying vibration intensities during operation due to multiple factors such as high-speed impeller rotation, continuous bearing friction, and the mechanical coupling between the pump body and pipelines. By installing vibration sensors near critical locations—specifically around the bearings and impeller housing—real-time monitoring of vibration changes can be achieved, enabling early identification of faults caused by bearing wear, impeller imbalance, or pump looseness.

To ensure precise vibration measurement, the proposed system employs an industrial-grade vibration sensor module. This module integrates a built in Bluetooth 5.0 chip and a voltage regulation circuit, powered by a 3.7 V lithium battery, providing simple installation and reliable operation even in the complex environment of the cooling system. In addition, the sensor is equipped with digital filtering technology to effectively suppress measurement noise, improve data accuracy, and enhance the reliability of vibration data acquisition.

The raw data collected by the vibration sensor are stored in a hexadecimal encoded format following a packet structure specification with a fixed Flag = 0 × 61. Each data frame has a fixed length of 32 bytes, which completely includes the key vibration parameters required for monitoring the mechanical condition of devices within the grid-forming SVG water-cooling system. This structure fully supports the evaluation of mechanical states in critical components such as the water pump and cooling pipelines.

Each frame begins with a constant header (0 × 55) indicating the start of the data packet, followed by a data type identifier (0 × 61). The subsequent bytes are arranged sequentially to represent three-axis vibration velocity, three-axis vibration angle, temperature, three-axis displacement, three-axis vibration frequency, alarm status, and battery voltage. All multi-byte parameters adopt a little endian format, where the lower byte precedes the higher byte, ensuring compatibility with the wireless transmission module’s data parsing logic. This design enables the efficient upload of structured data to the edge-computing node for further processing.

A portion of the collected vibration data is presented in Table 1 as representative examples.

Table 1.

Sample vibration sensor data.

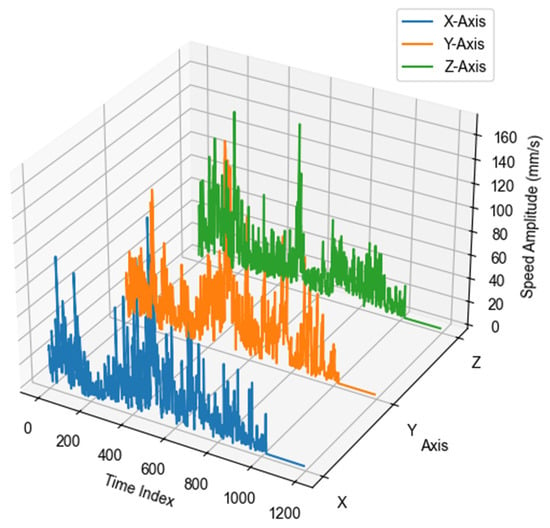

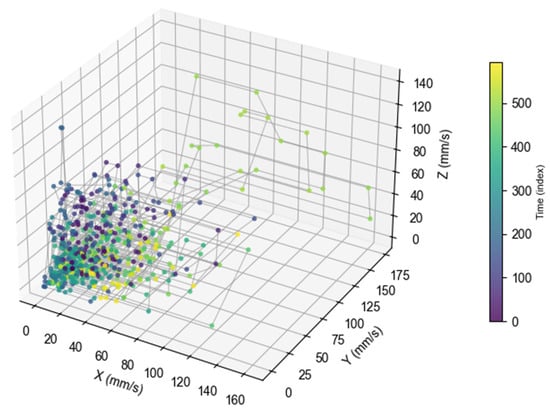

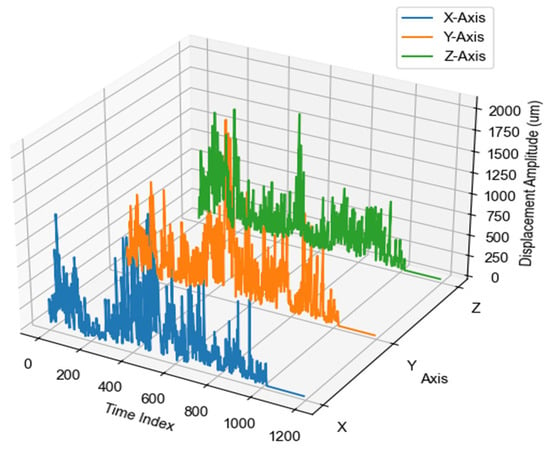

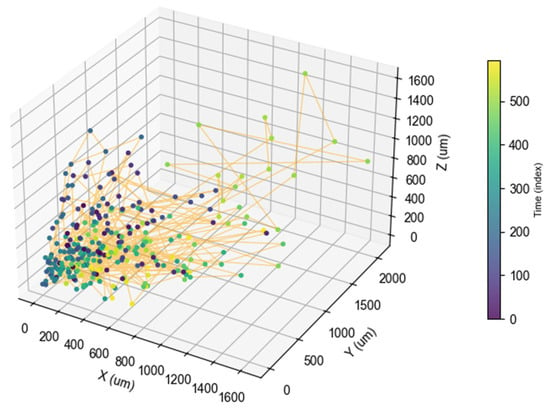

The vibration sensor continuously monitors the operating equipment at a fixed sampling frequency and outputs the results in a standardized data format. The recorded parameters include three-axis vibration velocity and three-axis vibration displacement, which are illustrated in Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6.

Figure 3.

Three-axis vibration velocity data.

Figure 4.

Three-axis vibration velocity scatter plot.

Figure 5.

Three-axis vibration displacement data.

Figure 6.

Three-axis vibration displacement scatter plot.

The vibration velocity (unit: mm/s) quantifies the severity of equipment vibration along three spatial directions. By comparing the measured velocity values with the normal operating thresholds, the vibration condition can be effectively assessed. Large fluctuations or frequent exceedance of the normal limits may indicate unbalance, looseness, or bearing wear. When such abnormalities occur in the pump, they can reduce coolant flow stability and discharge head, diminishing coolant circulation efficiency and overall cooling performance.

The vibration displacement (unit: µm) represents the spatial movement amplitude of a component along three axes during operation. Excessive displacement indicates that parts have moved beyond acceptable mechanical tolerances, potentially leading to loosened joints or seal failures in precision components of the cooling system. In particular, large displacement amplitudes at pipeline junctions may damage sealing elements, cause coolant leakage, and consequently reduce coolant circulation and heat-dissipation efficiency.

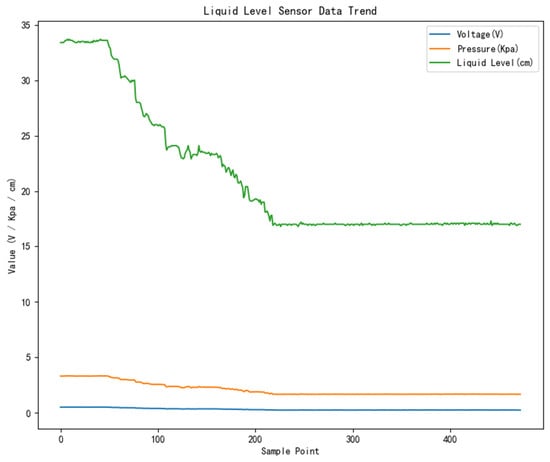

4.2. Liquid-Level Data

In the grid-forming SVG cooling system, monitoring liquid-level data is essential for ensuring stable operation and maintaining high cooling efficiency. As the coolant serves as the primary heat-transfer medium, variations in its level directly affect the cooling capability. Within the coolant reservoir tank, the liquid level determines the available reserve volume, which in turn influences whether the water pump can maintain continuous and stable coolant circulation.

To satisfy the system’s monitoring requirements, an MSP20 liquid-level sensor (Fu’an Stein Electronic Technology Co., Ltd., Fu’an (Ningde City, Fujian Province), China) module was employed. This sensor operates based on the piezoresistive pressure-sensing principle. Internally, it consists of an elastic diaphragm connected to a Wheatstone bridge composed of four piezoresistive elements integrated within the membrane. When the diaphragm deforms under the pressure exerted by the coolant, the bridge outputs a linear millivolt-level voltage signal. As the liquid level increases, the hydrostatic pressure on the diaphragm rises, resulting in a stronger output voltage.

The sensor outputs data in a structured “timestamp–voltage (U)–pressure (P)–liquid-level height (H)” format. All data are stored in CSV files, where each record includes one timestamp field and three core parameter fields. A portion of the recorded data is presented in Table 2 as representative samples.

Table 2.

Sample liquid-level data.

The output voltage U of the liquid-level sensor represents the standard conditioned signal within a range of 0–3 V. The pressure P is derived from the corresponding voltage signal, while the liquid-level height H is calculated using the hydrostatic pressure equation. The measurement accuracy of H is maintained within ±1 cm, and the sensing range covers 10–300 cm, which fully meets the precision requirements for liquid-level monitoring in the cooling system. The liquid-level data collected by the sensor are illustrated in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Liquid-level Acquisition Data.

Based on the processed liquid-level data, the coolant reserve capacity can be accurately evaluated to determine its ability to support the cooling performance of the SVG equipment (Nanjing NARI-Relays Electric Co., Ltd., Nanjing (Jiangsu Province), China). The key interpretations derived from the liquid-level measurements are summarized as follows:

- The normal operating range of the coolant tank level is determined by the system’s design capacity, with the main objective of ensuring that the pump inlet remains fully submerged to avoid dry running. When the liquid level remains stable within the defined range, the coolant reserve is sufficient to sustain proper suction and continuous circulation, and no replenishment is required.

- If the measured level remains consistently below the lower threshold across multiple sampling intervals, it indicates inadequate coolant storage. In such cases, the pump may experience reduced flow due to insufficient suction, triggering a coolant refill warning to prevent overheating of the IGBT modules.

- When the liquid level persistently exceeds the upper limit, it suggests overfilling, which may cause overflow, coolant wastage, or potential electrical safety risks.

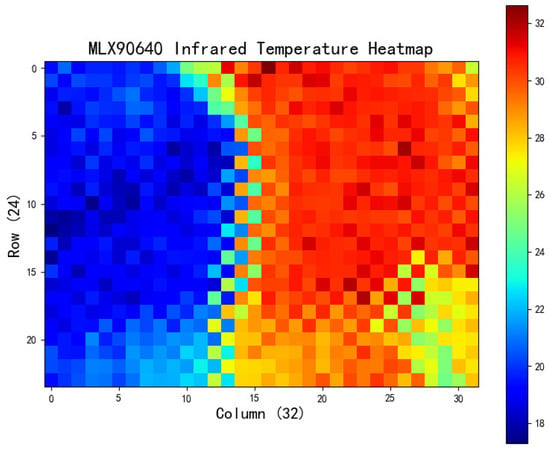

4.3. Infrared Thermal Map Data

In the grid-forming SVG water-cooling system, the radiator and main coolant pipelines serve as the core channels for heat exchange and transfer. The radiator dissipates the coolant’s heat into the surrounding environment, while the pipelines ensure continuous coolant circulation for efficient heat transport. Under the enclosed conditions of the converter valve hall—characterized by strong electromagnetic interference (EMI) and high-power operation—these components are prone to thermal anomalies caused by dust accumulation, partial blockages, micro-leaks, or poor thermal contact. Traditional point-type temperature sensors, due to their *single-point measurement* limitation, fail to provide full spatial coverage and may overlook early-stage faults that develop gradually.

To enable comprehensive thermal monitoring and early detection of abnormal heat distribution, an industrial-grade infrared sensor with EMI-resistant design is employed in the proposed system. Following the principle of “complete coverage of critical heat-dissipation paths,” infrared sensors are strategically deployed at the following key positions:

On the front surface of the radiator(to monitor the radiator’s temperature distribution) and at the inlet and outlet sections of essential pipelines(to capture the temperature variation along the coolant path).

The recorded infrared data are stored in a structured format of “timestamp—temperature matrix—key temperature difference.” Each record includes one timestamp field with millisecond precision, two core region temperature matrices, and two key differential temperature values. The data are saved in CSV format, facilitating efficient parsing by the edge-computing node and seamless integration with vibration and liquid-level data for multi-source data fusion.

Representative samples of infrared monitoring data are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Sample infrared sensor monitoring data (°C).

The infrared sensor data are illustrated in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Single-frame infrared thermal imaging image.

By analyzing the temperature distribution patterns and temperature difference variations extracted from the infrared data—and combining these results with the heat-exchange characteristics of the key components in the water-cooling system—abnormal thermal behaviors can be effectively identified. Through real-time comparison between the observed temperature parameters and the established “normal thermal baseline,” the system can detect subtle thermal anomalies, enabling accurate evaluation of cooling efficiency, fault localization, and overall health assessment of the water-cooling system.

4.4. Acoustic Data

During the operation of the grid-forming SVG water-cooling system, long-term high load conditions and strong electromagnetic interference can lead to latent faults that are difficult to detect in their early stages. For instance, pump bearing wear caused by insufficient lubrication may result in a frequency shift in the mechanical friction sound pattern, while radiator fan blade contamination or deformation can induce mid-frequency airflow noise due to turbulence. These types of faults often show no clear temperature abnormalities or visible physical damage in the early stage; instead, they manifest as subtle fluctuations in sound-pressure levels within specific frequency bands. Conventional point type temperature sensing or manual inspection methods are incapable of capturing these weak acoustic signatures, allowing such issues to worsen over time, subsequently reducing coolant circulation efficiency and threatening the reliable operation of the SVG equipment.

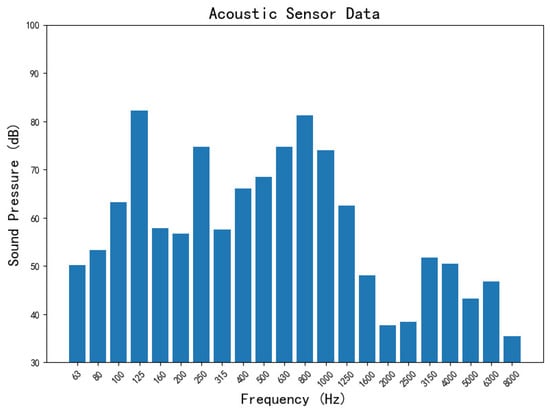

To enable early detection of hidden faults, the proposed system employs an industrial-grade acoustic sensor with strong electromagnetic interference resistance. The sensor operates at a sampling frequency of 1 Hz, capturing sound signals within the 63 Hz–8 kHz frequency range. It outputs structured data containing 22 groups of one third octave band sound-pressure values along with corresponding timestamps. These acoustic measurements provide critical diagnostic information for identifying mechanical faults (e.g., pump and fan anomalies) and fluid faults (e.g., pipeline leakage) at an early stage. By incorporating this acoustic dimension, the system effectively compensates for the limitations of temperature- or vision-based monitoring, thereby establishing a dedicated “acoustic safety monitoring” framework for the SVG water-cooling system.

Representative acoustic data are listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Partial values of acoustic frequency and sound-pressure data (dB).

The data collected by the acoustic sensor is shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Data collected by acoustic sensor.

By analyzing the frequency characteristics and sound-pressure variation patterns of the acoustic signals, and correlating them with the distinct sound signatures of key components in the water-cooling system, abnormal acoustic behaviors can be effectively identified. Through a real-time comparison between the measured sound-pressure values and the established “normal acoustic baseline,” the system is capable of detecting subtle deviations indicative of early stage faults. This enables accurate fault localization and diagnosis for both the water pump and radiator, allowing maintenance actions such as cleaning or repair to be carried out promptly. Consequently, the system helps maintain the radiator’s heat-dissipation efficiency and prevents degradation of the cooling system’s thermal exchange performance.

5. Wireless Monitoring and Fault Diagnosis Framework for the Grid-Forming SVG Water-Cooling System

5.1. Hierarchical Communication Network Design and Hardware Parameters

5.1.1. Hierarchical Communication Process

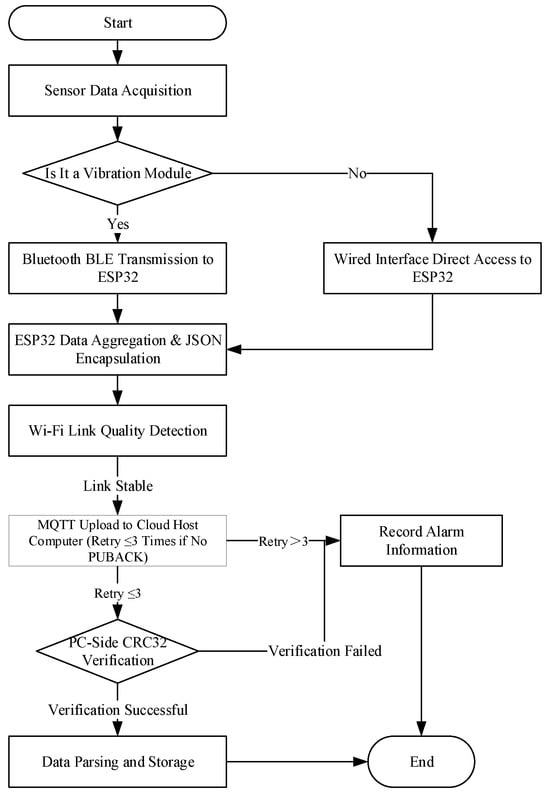

The system adopts a hierarchical communication architecture that integrates short-range Bluetooth data acquisition with long-range Wi-Fi data transmission. The vibration sensing module communicates with the ESP32 via Bluetooth, enabling close-range and low-power data transfer. Meanwhile, other sensors—including the infrared, liquid-level, and acoustic modules—are connected directly to the ESP32 through wired interfaces. Finally, the ESP32 transmits all collected data to the cloud-based host via a combination of Wi-Fi and the Message Queuing Telemetry Transport (MQTT) protocol. The overall communication workflow is illustrated in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Workflow diagram of the hybrid communication network.

This architecture achieves efficient synergy between low-power local acquisition and high-reliability remote transmission, ensuring flexible deployment of the vibration module while maintaining real-time performance and overall communication stability for the system.

5.1.2. Stability Assurance Under Strong Electromagnetic Interference

To ensure communication stability in the high-electromagnetic-interference environment of a 500 kV substation valve hall, the system combines industrial-grade EMI-resistant acoustic sensors with multiple software-level reliability mechanisms.

First, all data are encapsulated using JSON-based standardized formatting, which is implemented on the ESP32 development board via Arduino IDE 2.2.1 (integrating the ArduinoJson library, Version 6.21.3). This JSON encapsulation includes four core fields:

- data_id (project _date _device ID _sequence, e.g., SVG_20250920_001_0001);

- device_info (device ID/type/three-dimensional coordinates);

- data_content (data type/value/millisecond-level timestamp; large volume data encoded in Base64);

- check_info (CRC32 checksum + encryption identifier).

Second, the system implements an MQTT QoS 1 message delivery mechanism, establishing a reliable publishing-acknowledgement communication chain. If the edge node does not receive a PUBACK response after transmission, the message is automatically retransmitted up to three times to ensure delivery integrity.

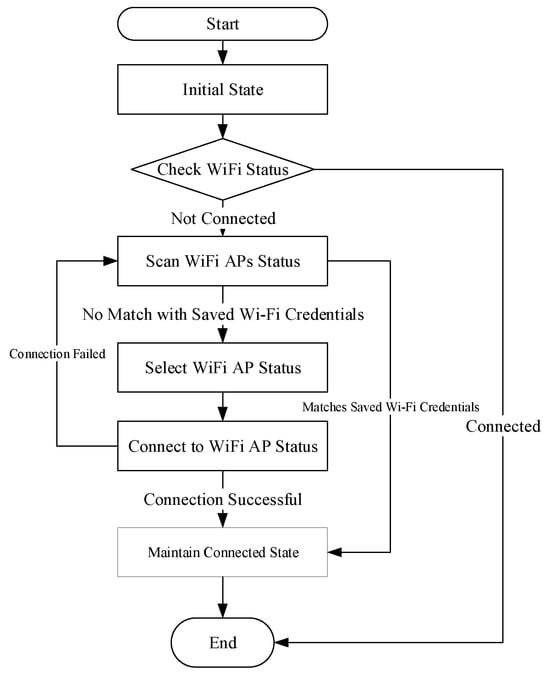

Finally, the system incorporates a Wi-Fi auto reconnection state machine consisting of six stages—initialization, status check, network scanning, access point selection, connection, and maintenance—to maintain continuous and stable communication. When the link is interrupted, the reconnection process is immediately triggered. The Wi-Fi auto reconnection logic is shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

State machine process of the Wi-Fi auto reconnection mechanism.

5.1.3. Comparison with Traditional Wired Monitoring Systems

Compared with conventional wired monitoring systems, the proposed wireless monitoring system for grid-forming SVG cooling efficiency exhibits significant advantages across multiple dimensions.

From a deployment cost perspective, the wireless system requires substantially lower initial investment. Its installation costs are reduced by approximately 40% since no additional cabling or wiring is necessary. In contrast, the wired system involves not only high material expenses but also more than 35% labor cost share, resulting in higher overall upfront expenditure.

In terms of operation and maintenance (O&M) costs, the wireless system maintains a medium-level cost profile while achieving stable operation for more than 72 h of continuous runtime. Fault localization and troubleshooting are straightforward, allowing for minimal downtime. Conversely, the wired system incurs higher O&M costs, with cable faults accounting for nearly 70% of total maintenance incidents. Each maintenance activity requires a temporary shutdown of equipment, posing a risk to uninterrupted SVG operation.

In terms of scalability, the wireless architecture adopts a star-topology network, enabling new sensor nodes to be added simply through parameter configuration rather than additional cabling. This ensures flexible and rapid expansion. The wired solution, however, requires re-wiring during system upgrades, extending the deployment cycle and limiting scalability.

Regarding flexibility, the wireless sensors can be easily repositioned or redeployed according to monitoring requirements, offering high adaptability in measurement-point adjustment. Wired systems, constrained by fixed cabling, suffer from low flexibility and risk of resource waste during layout modification.

Furthermore, the current wireless framework—featuring a standardized data format, compatible communication protocols, and integrated diagnostic logic—lays a solid foundation for future integration with digital-twin platforms. Nevertheless, this integration still faces multiple challenges, including data-scale explosion, model coordination complexity, absence of closed-loop control, and interoperability-plus-cybersecurity issues among heterogeneous systems. These challenges call for further targeted technological breakthroughs to achieve deep, intelligent integration of monitoring and control.

5.1.4. Multi-Source Data Synchronization

To address the data-timing discrepancies between continuous-sampling sensors (e.g., vibration and acoustic sensors) and periodic-sampling sensors (e.g., infrared and liquid-level sensors), the system achieves spatio-temporal synchronization through coordinated alignment of timestamps and spatial information.

The vibration and acoustic sensors perform continuous data acquisition according to their respective sampling frequencies. Each collected data frame is automatically tagged with a millisecond-level timestamp synchronized by the network gateway. In contrast, the infrared and liquid-level sensors operate in a 1 s (1000 ms) acquisition cycle, also generating timestamp annotations at the moment of data creation. All sensor nodes operate independently without cross-interference, ensuring the integrity and continuity of their respective data streams.

During JSON data encapsulation, every data packet includes the device ID and three-dimensional coordinates of the sensor node. After receiving multi-source data, the ESP32 gateway performs format validation and primary integration before transmitting the unified dataset—with complete timestamps, device IDs, and spatial coordinates—to the upper-level host system. On the host side, all data are temporally arranged based on the millisecond-level timestamps and spatially correlated using the device IDs and coordinate information.

This process ensures precise temporal and spatial synchronization of multi-source sensor data, eliminating the potential misalignment caused by transmission delay or sensor dispersion. The resulting synchronized dataset forms a unified spatio-temporal foundation for subsequent fault correlation analysis and location diagnostics within the water-cooling monitoring system.

5.2. Multi-Source Fault Diagnosis Framework Based on Hierarchical Weighted Fusion

Considering the complexity of fault mechanisms in the grid-forming SVG water-cooling system and the limitations of single-sensor diagnosis—such as false alarms or missed detections—this study develops a hierarchical weighted multi-source information fusion diagnostic framework. Using multi-dimensional data collected from acoustic, vibration, liquid-level, and infrared thermal sensors, the proposed framework follows a three-level architecture comprising the following:

(1) Individual sensor feature extraction and preliminary analysis;

(2) Feature-level weighted fusion;

(3) Final fault classification.

This architecture enables accurate identification of typical cooling system faults while balancing diagnostic accuracy and real-time performance, making it suitable for rapid on-site maintenance in industrial environments.

5.2.1. Single-Sensor Feature Extraction and Preliminary Fault Identification

Single-sensor feature extraction and initial fault identification form the foundation of the multi-source fusion process. Multi-physical data collected by the four sensor types are first preprocessed using filtering algorithms to suppress noise induced by the strong electromagnetic interference within the valve hall. Core features are then extracted from each sensor’s data stream and compared against predefined threshold values to generate initial fault judgments, each assigned a confidence coefficient Ci (i = 1, 2, 3, 4) corresponding to the infrared, vibration, acoustic, and liquid-level sensors, respectively, as follows:

- The infrared thermal sensor monitors the spatial temperature distribution of the radiator and coolant pipelines. Based on threshold differences in thermal regions, it performs preliminary detection of radiator blockages and pipeline micro-leakages.

- The vibration module measures vibration data from pump bearings and pipeline joints. By analyzing the root-mean-square values of three-axis vibration velocity and displacement thresholds, it identifies pump bearing wear and pipeline looseness.

- The acoustic sensor captures sound-pressure data across the 63 Hz–8 kHz frequency band. Sudden changes in sound pressure within specific frequency ranges are used to detect bearing wear and radiator clogging.

- The liquid-level sensor tracks the coolant tank level and its rate of change. Using threshold limits for minimum level, rate of descent, and fluctuation magnitude, it identifies coolant leakage or circulation abnormalities.

Before fusion, all sensor data undergo timestamp alignment and spatial coordinate mapping to achieve precise temporal and spatial registration. This ensures that standardized, synchronized datasets are available for subsequent fusion-level diagnosis. The confidence coefficients of each sensor satisfy: 0 ≤ Ci ≤ 1.

5.2.2. Feature-Level Weighted Fusion Calculation

To achieve accurate fault identification in the grid-forming SVG water-cooling system, a multi-source data fusion framework based on a hierarchical weighted strategy is developed. This framework follows the process of “weight assignment → conflict correction → confidence fusion,” combining fault evidence from multiple sensors to enhance diagnostic reliability.

First, the preliminary diagnostic results from the four sensor types are treated as independent evidence sources. The weighted Dempster–Shafer (D-S) combination rule is then applied for confidence integration. The procedure is described as follows:

(1) Weight Assignment:

The assignment of evidence weights is determined according to the fault recognition accuracy of each type of sensor under different fault scenarios. Accordingly, four evidence sources—infrared thermal sensor, vibration module, acoustic sensor, and liquid-level sensor—are assigned weighting coefficients that satisfy the normalization constraint . Specifically, the corresponding weights are defined as = 0.3 for the infrared sensor, = 0.2 for the vibration module, = 0.2 for the acoustic sensor, and = 0.3 for the liquid-level sensor.

The initial confidence level obtained from each individual sensor is then adjusted according to its respective weight to yield the weighted evidence confidence , which is expressed as follows:

where represents the fault type identified by the -th sensor.

(2) Conflict Coefficient Calculation:

To quantify inconsistencies between different evidence sources, a conflict factor is defined as follows:

When is equal to 1, a significant contradiction exists among the diagnostic conclusions, and evidence correction is performed based on the historical fault database and feature thresholds. Conversely, when is equal to 0, the sensor outputs are consistent and can be directly used for fusion.

(3) Fault Confidence Fusion:

The final combined confidence for each fault type is computed using the weighted Dempster combination rule:

where denotes the intersection of consistent fault evidence from all sensors; the numerator aggregates the product of matching evidence confidences; while the denominator compensates for information conflicts to ensure stable synthesis.

The integrated fault confidence is then compared with a preset threshold = 0.5. When ≥ , the corresponding fault type is confirmed, and the system automatically retrieves the related troubleshooting scheme from the fault knowledge base, transmitting it to the host computer via the MQTT protocol.

If multiple fault types exceed the threshold, the fault with the highest confidence value is considered the primary fault, while the second-highest is recognized as the secondary fault, achieving accurate differentiation under multi-fault conditions.

6. System Performance Testing and Analysis

To verify the effectiveness of the proposed wireless monitoring and multi-source data fusion fault diagnosis framework for the grid-forming SVG water-cooling system, a dedicated experimental setup was established using a grid-forming SVG unit located in a 500 kV substation. Two specific categories of experiments were conducted simultaneously: tests of the wireless communication network performance and evaluation of the multi-source data fusion-based diagnostic capability.

In this validation process, the wireless transmission state parameters were combined with data streams collected from the vibration, liquid-level, infrared, and acoustic sensors. This integration formed a combined “communication-status–equipment-condition” diagnostic logic, allowing for a comprehensive verification of the system’s end-to-end performance across the entire monitoring and diagnostic chain.

6.1. Experimental Design

6.1.1. Device Deployment and Network Architecture

Multiple types of sensors and hierarchical wireless communication nodes were deployed at key monitoring locations of the SVG water-cooling system, including the pump bearings, coolant pipeline connectors, coolant reservoir, and radiator surfaces. The overall water-cooling installation within the valve hall is illustrated in Figure 12, while the physical monitoring system prototype is shown in Figure 13.

Figure 12.

Water-cooling installation in the SVG valve hall.

Figure 13.

Physical prototype of the monitoring equipment.

The overall experimental setup consists of three hierarchical layers, the sensing layer, the communication layer, and the environmental configuration, as described below:

(1) Sensing Layer:

Different types of sensors were deployed according to their monitoring functions:

- A three-axis vibration sensor (frequency range: 5–100 Hz; measurement error < 5%) is used to monitor the mechanical condition of the pump bearings and pipeline connections;

- A liquid-level sensor (measuring range: 10–300 cm; accuracy: ±1 cm) is installed on the coolant tank to monitor coolant volume and flow stability;

- An industrial-grade infrared thermal sensor (temperature range: –20 °C to 300 °C; accuracy: ±2 °C) is positioned to cover the radiator and pipe inlet/outlet sections, capturing the system’s temperature distribution;

- An electromagnetic-interference-resistant acoustic sensor (frequency range: 63 Hz–8 kHz; sound-pressure accuracy: ±1.5 dB) is installed on the radiator surface and near the pump bearings to acquire acoustic signatures.

All sensors are integrated through a hybrid Wi-Fi/Bluetooth wireless network, ensuring stable and reliable transmission of multi-source data across the cooling system.

(2) Communication Layer:

A hierarchical “Bluetooth (vibration module to ESP32 gateway) + Wi-Fi (ESP32 to host, MQTT protocol)” architecture was established to support multi-node wireless communication.

The system consists of four ESP32 gateway nodes, two Bluetooth vibration modules, and five wired sensor nodes.

The communication distance between the vibration modules and the corresponding ESP32 gateways ranges from 0.5 to 1 m, while the Wi-Fi connection between the ESP32 gateways and the cloud-based host system covers a range of 20 to 50 m.

(3) Environmental Parameters:

The experiment was conducted in the 500 kV converter valve hall of a substation, where the equipment operates under intense electromagnetic interference (EMI). The 2.4 GHz band experiences signal interference mainly caused by SVG system harmonics.

6.1.2. Fault Simulation and Testing Procedure

The fault simulation and testing cycle are described as follows:

(1) Fault Simulation:

To evaluate the performance and diagnostic capability of the proposed system, three typical fault conditions and one normal operation state were artificially simulated in the SVG water-cooling system. The scenarios are as follows:

- Pump bearing wear, simulated by reducing the lubrication level of the bearings;

- Pipeline micro-leakage, simulated by introducing a small leakage point at a pipe joint;

- Radiator blockage, created by filling fine dust between the radiator fins;

- Normal operation, representing the system without any intentional faults.

Throughout these experiments, the wireless communication link status was simultaneously recorded under each fault condition to evaluate transmission stability in different operational scenarios.

(2) Testing Cycle:

The experiment was conducted over a period of 10 days, with eight test groups designed and executed each day. Each test group included single- or multi-fault conditions (as well as normal state scenarios) and consisted of four rounds of data acquisition per group. In total, 320 data-collection and diagnostic tests were completed. Concurrently, dedicated tests were performed to validate the reliability of wireless communication under varying fault and operational states.

6.2. Wireless Communication Network Performance Testing and Analysis

6.2.1. Core Transmission Performance Indicators

Performance evaluations were carried out for both the Bluetooth data-acquisition link and the Wi-Fi uploading link, focusing on three principal indicators: data throughput, end-to-end latency, and energy efficiency (battery endurance). The detailed test results are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Transmission performance of the hierarchical communication network.

The test results indicate that the Bluetooth link meets the short-distance, low-power transmission requirements of the vibration module, ensuring latency below 15 ms for high-frequency and small-packet data communication. The Wi-Fi link, used for cloud uploading, achieves a data throughput of 7–8 Mbps and an end-to-end delay of less than 70 ms, which fully satisfies the current cooling system’s real-time communication needs. However, this level of latency may become a limiting factor in large-scale multi-device deployments, where increased data volume can potentially degrade transmission responsiveness.

In terms of power consumption, the modules exhibit the following average values: vibration module—18.5 mW, acoustic sensor—240 mW, liquid-level sensor—15 mW, infrared sensor—115 mW, and ESP32 gateway—800 mW. The system is powered by a 5 V 24,000 mAh battery, providing a theoretical endurance exceeding 100 h. With optimized sleep strategies for both sensors and gateways, the actual stable runtime exceeds 72 h, supporting continuous real-time uploading of heterogeneous multi-source data, thereby meeting industrial-grade monitoring requirements.

6.2.2. Communication Reliability Verification

During ten consecutive days of continuous testing, data-transmission records were randomly sampled to evaluate communication reliability. The total number of transmitted and successfully received data packets were counted, and the transmission success rate was calculated, as shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Reliability test results of the hierarchical communication network.

In the high-electromagnetic-interference environment of the converter valve hall, the Bluetooth link demonstrated a high success rate of 98.82%, primarily due to its short transmission distance and strong anti-interference capability. Meanwhile, the Wi-Fi link, supported by the MQTT protocol with QoS 1 retransmission, effectively mitigated packet loss caused by signal fluctuations, achieving an overall success rate of 99.57%. These results confirm that the proposed hybrid communication network provides a stable and reliable data-transmission foundation for multi-source diagnostic processing.

6.2.3. Comparison of Wireless Technology Suitability

To evaluate communication suitability under SVG water-cooling monitoring conditions, the proposed hierarchical hybrid communication architecture was compared with conventional ZigBee and LoRa technologies. The performance comparison is summarized in Table 7.

Table 7.

Comparison of different wireless communication technologies.

Comparative analysis shows that the combination of low-power Bluetooth for short-range data collection and high-throughput Wi-Fi for long-range data uploading effectively balances energy efficiency at the sensing layer and transmission efficiency at the host interface. Overall, this hybrid communication framework aligns well with the data density, reliability, and real-time requirements of SVG water-cooling system monitoring.

6.3. Multi-Source Data Fusion Diagnostic Performance Testing

Table 8 presents the system performance results under various fault conditions, intuitively demonstrating the diagnostic capability of the proposed multi-source data fusion framework based on four heterogeneous sensor types.

Table 8.

System performance results under different fault conditions.

As shown in Table 8, the fusion-based system integrating vibration, liquid-level, infrared, and acoustic signals achieved consistently high performance across all tested fault scenarios. The results reveal the following about fault detection rate and diagnostic accuracy rate:

(1) Fault Detection Rate (FDR):

All three fault categories exhibited detection rates above 98%. Among them, *pipeline micro-leakage* achieved the highest detection rate of 99.2%, primarily because the infrared sensor directly captures temperature distribution anomalies on pipeline surfaces, producing distinct fault features. The detection rate for *pump bearing wear* was slightly lower (98.7%) due to the mild nature of early-stage wear and the potential interference affecting vibration and acoustic signal features in the test environment.

(2) Diagnostic Accuracy Rate (DAR):

The diagnostic accuracy for all fault categories exceeded 98.2%, while the *normal operating condition* achieved an accuracy of 99.4%. These results demonstrate that the proposed system effectively distinguishes between faulty and normal states, minimizing false alarms. Moreover, it can accurately identify the root cause of each fault and provide early detection of cooling-efficiency degradation trends within the SVG water-cooling system.

7. Conclusions

This study focuses on the practical engineering requirements for condition monitoring of grid-forming SVG water-cooling systems and successfully develops a wireless multi-source information fusion monitoring system tailored to this application. By integrating liquid-level, vibration, acoustic, and infrared sensing units, a wireless sensor network was established that operates reliably under the strong electromagnetic interference (EMI) conditions of the converter valve hall. The proposed system enables coordinated acquisition and stable transmission of multi-dimensional thermal, acoustic, vibration, and visual information within the cooling process.

A multi-source information fusion diagnostic framework, centered on cooling efficiency, was proposed to overcome the limitations of conventional single-parameter monitoring. This framework allows for precise identification and early warning of compound faults, including pump performance degradation, pipeline blockage or leakage, and radiator efficiency decline.

Experimental validation demonstrates that the system provides high communication reliability with a packet loss rate below 1.5%, while improving the overall fault diagnosis accuracy to 98.2%, significantly outperforming traditional wired or single-sensor monitoring approaches.

Overall, the proposed system offers a comprehensive technical solution and a practical implementation pathway for intelligent operation and maintenance of grid-forming power electronic equipment. It contributes substantially to enhancing the safety, stability, and reliability of new-generation power systems in the context of renewable-energy-dominant grids.

Although this study has achieved promising progress in monitoring grid-forming SVG water-cooling systems, certain limitations remain. First, the experimental validation was conducted using a single type of grid-forming SVG device located in a 500 kV substation, without cross-scenario testing across systems of different capacities or manufacturers. Therefore, the generalization capability of the proposed diagnostic model requires further verification.

Second, the current multi-source information fusion algorithm relies on predefined fixed weight coefficients, lacking dynamic and adaptive adjustment. As a result, its diagnostic flexibility is limited when facing highly variable valve hall conditions and compound fault scenarios involving multiple concurrent abnormalities.

Finally, although the system’s endurance meets short-term monitoring requirements, issues related to long-term power supply and sensor degradation during continuous field operation have not yet been fully resolved.

Future work will focus on the following aspects:

1. Expanding the experimental scope to include various types and capacities of grid-forming SVG systems, thereby improving model optimization and enhancing the algorithm’s generalization performance;

2. Developing an adaptive weighting strategy for multi-source fusion to improve diagnostic accuracy and robustness under complex operating condition;

3. Exploring the integration of low-power sensor nodes with wireless charging technology to ensure stable long-term operation and reliable system sustainability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.D.; methodology, L.X.; software, H.Z.; validation, J.Z.; formal analysis, Y.Z.; investigation, G.T.; resources, L.L.; data curation, B.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, B.Y. and L.X.; writing—review and editing, P.W. and G.T.; visualization, P.W.; supervision, J.D.; project administration, L.L.; funding acquisition, L.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

State Grid Provincial Company’s Key Science and Technology Project: Research on Key Technologies for the Operation, Maintenance, and Inspection of Grid-Forming SVG.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Liqian Liao, Jiayi Ding, Guangyu Tang, Yuanwei Zhou were employed by the State Grid Chengdu Electric Power Supply Company. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Shu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Guo, J.; Zhang, Z. Study on Key Factors and Solution of Renewable Energy Accommodation. Proc. CSEE 2017, 37, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Z.; Li, H.; Qiao, Y. Flexibility Planning and Challenges in Power Systems with High Penetration of Renewable Energy. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2016, 40, 147–158. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, X.; Ma, S.; Luo, L.; Pang, B.; Deng, C. Mechanistic Analysis of the Impact of GFM-IBR on the Existence of GFL-IBR Stable Equilibrium Points. Power Grid Technol. 2025, 38, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Pei, X. Research on the Application of Grid-Following and Grid-Forming Converters in Power Systems. Electromech. Inf. 2025, 17, 60–63. [Google Scholar]

- Rocabert, J.; Luna, A.; Blaabjerg, F.; Rodriguez, P. Control of power converters in AC microgrids. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2012, 27, 4734–4749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Su, X.; Pei, W.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, L. Transient Synchronization Stability Control for Paralleled Grid-Forming Converter Systems Accounting for Virtual Torque Balance. Power Syst. Autom. 2025, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Huang, X.; Liu, J.; Lv, X.; Yang, H. Comparison and Analysis of Air Cooled and Water Cooled SVG Operation in New Energy Stations. Heilongjiang Sci. 2024, 15, 74–77. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.; Li, H.; Yuan, L. Design of High Voltage Explosion-Proof SVG Water Cooling Device. Coal Mine Electromech. 2019, 40, 25–27+34. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Liu, C.; Yang, Y.; Chen, C. Research on IGBT Loss and Junction Temperature Based on Water-cooled SVG. Power Electron. Technol. 2021, 55, 137–140. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, Y.; Liu, L. Research on loss of high power IGBT module. Inf. Technol. 2019, 43, 53–57+61. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Zhang, T.; Zheng, J.; Tan, X.; Shi, X. Cause Analysis of Weld Cracking on Water-Wall Tube in Subcritical Circulating Fluidized Bed Boiler. Inn. Mong. Power Technol. 2020, 38, 77–79. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H. Discussion on Tube Leakage Causes in the Water-Cooled Walls of Circulating Fluidized Bed Boilers. Shanxi Electr. Power 2021, 1, 70–72. [Google Scholar]

- Abdulhussain, S.H.; Mahmmod, B.M.; Alwhelat, A.; Shehada, D.; Shihab, Z.I.; Mohammed, H.J.; Abdulameer, T.H.; Alsabah, M.; Fadel, M.H.; Ali, S.K.; et al. A Comprehensive Review of Sensor Technologies in IoT: Technical Aspects, Challenges, and Future Directions. Computers 2025, 14, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Ma, J.; Li, X.; Li, W.; Zhang, X.; Song, B.; Sun, J. Substation Alarm Data Analysis and Inspection Strategy Based on Data Mining. Electr. Power Big Data 2019, 22, 20–26. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, J. Research on the Wireless Sensor Network for Monitoring the Thermal Power Plant. Master’s Thesis, North China Electric Power University, Beijing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, X. Application of Intelligent Inspection Robots in Substations. China Sci. Inf. 2025, 18, 47–49. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, S. Analysis of the Causes and Countermeasures of Water Pump Vibration Faults. Sci. Inf. Technol. 2025, 23, 77–79. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, L.; Tang, T.; Guo, Q.; Hui, Z. Research on Fault Diagnosis of Reciprocating Water Injection Pumps Based on Vibration Signals. Equip. Manag. Maint. 2024, 16, 177–179. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Tang, W. Temperature Monitoring and Early Warning Technology for Hydro-turbine Units based on Multi-source Information Fusion. Hydropower New Energy 2024, 38, 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, X. A Review of Research on Wireless Sensor Networks. Microcontrollers Embed. Syst. 2008, 8, 8–12. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y. Wireless sensor network applications in smart grid: Recent trends and challenges. Int. J. Distrib. Sens. Netw. 2012, 8, 492819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Sun, Y.; Yang, T.; Cui, Z. Application of Wireless Sensor Networks in Smart Grids. Electr. Power 2010, 43, 31–36. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, B. Design of Distribution Network Temperature Measurement System Based on ZigBee Technology. Telecom. World 2015, 23, 214. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, P.; Liu, R.; Sheng, H. Design of a Wireless Communication-Based Fault Maintenance System for Substation Operations. Electr. Technol. Econ. 2025, 6, 357–359+368. [Google Scholar]

- IEEE 802.15.4; IEEE Standard for Local and Metropolitan Area Networks—Part 802.15.4e-2012: Low-Rate Wireless Personal Area Networks (LR-WPANs); Amendment 1: MAC Sublayer. IEEE Working Group: New York, NY, USA, 2012.

- Lin, T.; Ren, Z.; Zhu, L.; Zhu, Y.; Feng, K.; Ding, W.; Yan, K.; Beer, M. A Systematic Review of Multi-Sensor Information Fusion for Equipment Fault Diagnosis. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Zhu, H.; Duan, Z. Multi-Source Information Fusion; Tsinghua University Press Co., Ltd.: Beijing, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J. Research on Remote Monitoring of a Gearbox External Oil-Cooling Device Based on Multi-Sensor Data Fusion. Mach. Ind. Stand. Qual. 2025, 2, 33–36. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, K.A. Study on electromagnetic interference (EMI) and electromagnetic compatibility (EMC): Sources and design concept for mitigation of EMI/EMC. J. Lib. Arts Humanit. (JLAH) 2023, 4, 68–96. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, D.; Xu, C.; Wen, J.; Chen, F. Current Status and Prospects of Multi-source Heterogeneous Data Fusion Technologies in Novel Power Systems. Electr. Power 2023, 56, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Q.; Yu, X.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, Y. Basic Methods and Progress in Information Fusion Theory. Acta Autom. Sin. 2003, 29, 599–615. [Google Scholar]

- Khaleghi, B.; Khamis, A.; Karray, F.O.; Razavi, S.N. Multisensor data fusion: A review of the state-of-the-art. Inf. Fusion 2013, 14, 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Luo, W.; Jiang, F.; Li, Y.; Yu, Y. Multi-Dimensional Analysis and Early Warning Model for the Cooling Capacity of Converter Valve. South Power Grid Technol. 2020, 14, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.