1. Introduction

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has consistently demonstrated effective results across various industries. In particular, Reinforcement Learning (RL), which enables an agent to learn optimal actions through continuous interaction with the environment based on reward signals, has proven efficient in solving problems requiring complex decision-making. As a result, RL is being widely adopted in sectors such as autonomous vehicles, robotics, healthcare, finance, and gaming [

1,

2]. Of these sectors, the gaming industry involves complex rules and highly dynamic environments, making it a suitable domain for applying RL to decision-making problems. Within this domain, First-Person Shooter (FPS) games operate in 3D spaces where agents must make immediate decisions based on their field of view and surrounding environment, providing a simulation closely resembling the real world; thus, the necessity for RL is further emphasized.

Recent works on reinforcement learning in FPS games have predominantly focused on Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) agents trained with a Monolithic Policy. In this paper, we refer to these as ‘Traditional Agents’. This method involves training the entire system at once to enable the agent to select optimal actions. FPS agents trained via this approach have been demonstrated to achieve human-level performance and exhibit competitive gameplay against human players [

3,

4,

5]. Despite these achievements, however, this method faces limitations, particularly in environments with sparse rewards during the early stages of training. As the agent struggles to achieve objectives, this often leads to slow convergence and excessive training time. For instance, if an agent does not receive an explicit reward until it finds and eliminates a target, learning becomes stagnant or progresses very slowly. To address these challenges, many researchers have introduced various learning techniques, such as Curriculum Learning and Behaviour Cloning [

6,

7].

Nevertheless, the Monolithic Policy approach still possesses limitations regarding interpretability, performance optimization, and structural flexibility when applied to game development First, since this approach relies on deep neural networks, the model operates as a “black box” that does not explicitly reveal its internal computational processes, making it difficult to interpret the rationale behind an agent’s specific action for a given input or to directly modify its policy. This lack of transparency limits the ability to analyze or debug the decision-making process of the trained policy. Second, since the Monolithic Policy approach integrates all behavioral patterns into a single network, it must process functionally distinct behaviors within a shared representation space. In FPS games, behavioral requirements differ significantly (ranging from precise aiming to tactical evasive maneuvers). Attempting to optimize these distinct objectives simultaneously within a single network increases model complexity and learning difficulty. Finally, the fact that the output layer of the network is directly coupled with the dimensions of the action space acts as a structural constraint.

Even a minor change in game design, such as adding or removing a single action like “Jump,” or adjusting existing gameplay parameters such as weapon fire rate or attack damage, can alter the final output dimension, rendering previously learned parameters incompatible. This implies that even trivial modifications to the action space or its associated control parameters require initializing the entire network and retraining from scratch. In a commercial game service environment that demands continuous updates and balance adjustments under tight schedules, this results in significant computational overhead and resource inefficiency [

8].

To overcome the lack of interpretability, difficulties in performance optimization, and constraints on structural flexibility inherent in monolithic policies, this study proposes a Modular Reinforcement Learning (MRL) framework applied to FPS agents, with the explicit goal of improving development efficiency under iterative game design and updates. We focus on a structural decomposition that leverages standard Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) to separate distinct behavioral roles. Unlike existing approaches that attempt to solve large-scale complex problems using a single monolithic policy, our method decomposes the task into semantically distinct sub-policies, such as Movement and Attack, which are trained in parallel as decoupled modules. This design improves interpretability by enabling clear understanding and modification of each module’s internal operations, and facilitates performance optimization by allowing specialized network architectures to be designed for each behavioral pattern. Importantly, this modular structure directly supports practical game development workflows, where mechanics, balance, and behaviors are frequently revised. When a specific behavior needs to be changed, only the relevant module requires retraining, effectively resolving the structural inefficiency of monolithic policy approaches that necessitate initializing and retraining the entire policy.

Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed Modular Agent reduces the retraining time required for modifying specific behaviors by approximately 35% compared to the monolithic policy method. This validates that our proposed method accommodates the iterative behavior modification process and flexibility required in game development much more efficiently. Additionally, in 1-vs-1 combat experiments, the proposed agent achieves a maximum win rate of 83.4% against the traditional agent, confirming its superior performance.

2. Background and Motivation

2.1. Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO)

In First-Person Shooter (FPS) games, Non-Player Characters (NPCs) interact with players through decision-making processes driven by game AI. Therefore, a well-designed game AI significantly enhances player immersion and the overall gaming experience. However, conventional game AI approaches, such as rule-based systems or simple algorithms, operate according to predefined rules within the game environment, resulting in predictable behavior patterns that are susceptible to exploitation by players. To address this, sophisticated decision-making mechanisms capable of handling the diversity and uncertainty of the game are required, and recent research has focused on Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) [

9].

Reinforcement Learning (RL) is a method where an agent learns to select optimal actions to maximize cumulative rewards over the long term. By combining RL with deep learning, DRL has demonstrated exceptional performance in complex problems and is being utilized across various fields [

10].

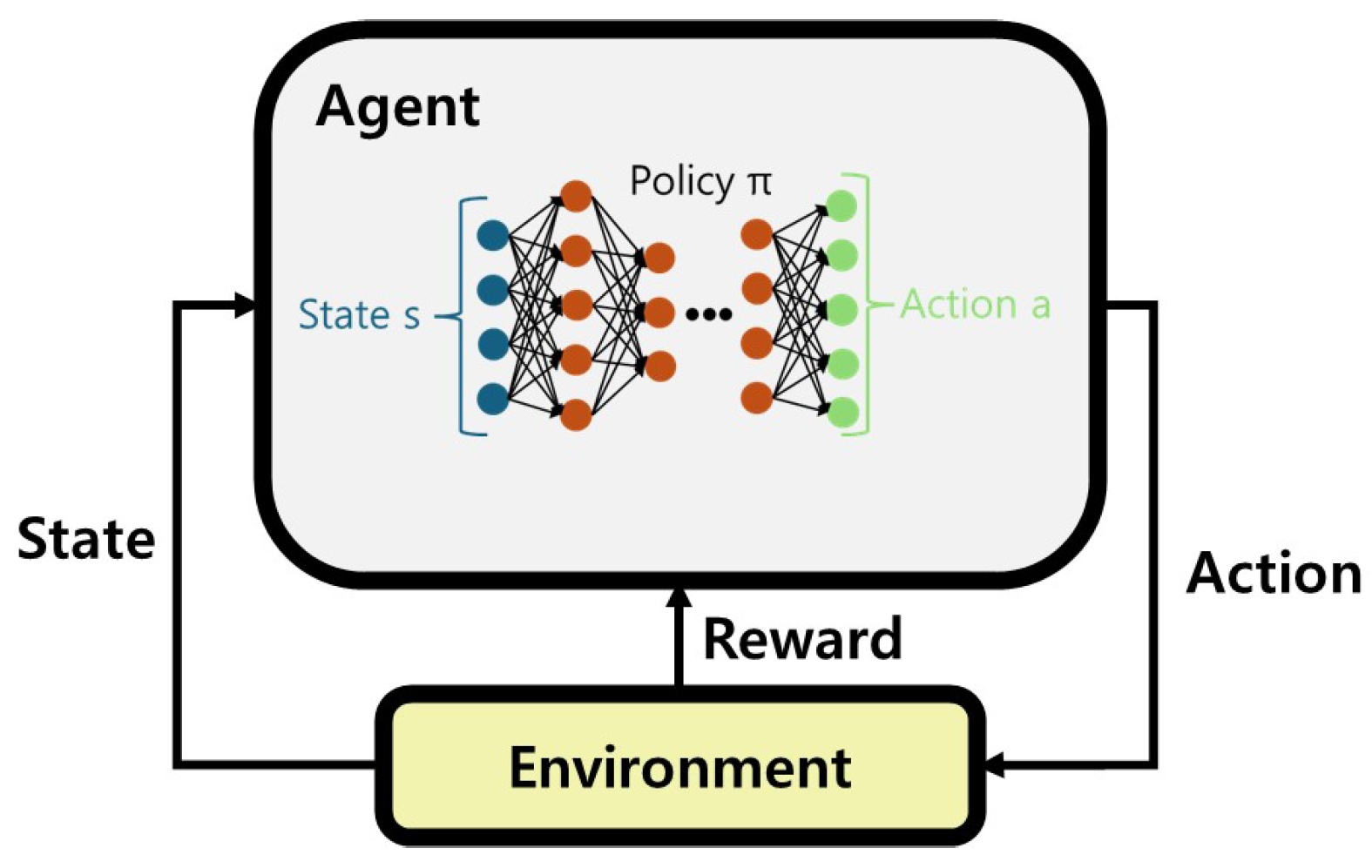

Figure 1 shows the DRL process, where an agent executes an action generated by a neural network based on a given state and learns from the calculated reward. Leveraging these advantages of DRL, FPS agents are being developed and studied on various platforms such as ViZDoom, DeepMind Lab, and Unity. In particular, Unity includes its own physics engine and tools for 2D and 3D game creation, providing the ML-Agents Toolkit for developing RL agents. The Unity ML-Agents Toolkit is open-source and supports RL algorithms such as Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) and Soft Actor-Critic (SAC) to facilitate the implementation of AI for developers [

11].

Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) is an algorithm designed to address policy optimization challenges in RL by balancing training stability and sample efficiency [

12]. When updating a policy, PPO calculates the probability ratio between the new and old policies and clips this ratio within a predefined range. This mechanism constrains the policy update step, effectively preventing performance collapse caused by drastic updates. The objective function of PPO is defined as follows:

Here, represents the probability ratio between the new and old policies, and denotes the estimated value of the Advantage Function. This advantage value serves as a key metric for quantifying how much better (positive value) or worse (negative value) an action performed by the agent in a specific state was compared to the average expected value. is a hyperparameter determining the clipping range (typically 0.1 or 0.2). The clipped probability ratio bounds the policy update, ensuring that excessive changes do not destabilize the learning process. By employing this clipping mechanism, PPO maintains training stability and demonstrates superior performance in continuous control problems or complex interactive environments. PPO is particularly sample-efficient, allowing data reuse through mini-batches over multiple epochs. For these reasons, the PPO algorithm is widely used in research utilizing the Unity ML-Agents Toolkit.

2.2. Challenges of Monolithic Policy DRL in FPS Game Agents

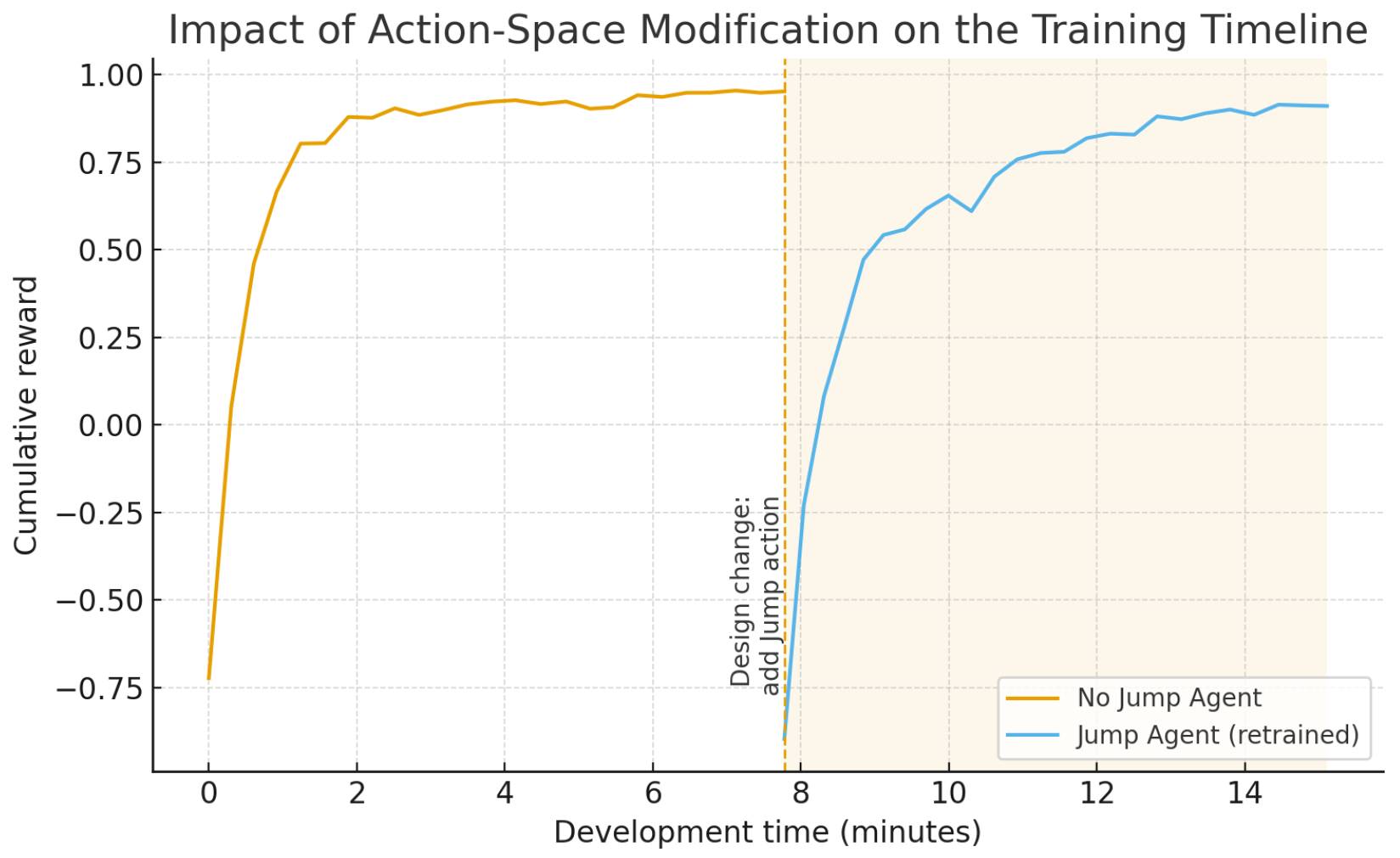

Applying such DRL to develop agents for FPS games presents several challenges. As shown in

Figure 2, existing Monolithic Policy DRL models are constituted as a “black box” where internal states and decision-making processes are difficult to understand. This makes it difficult for developers to interpret the agent’s rationale, adjust specific behaviors, or effectively incorporate designer-intended strategies into the policy.

Game development involves iterative design changes and tuning; thus, reusing previously learned policies is essential to maximize efficiency under limited time and resource constraints [

8]. However, Monolithic Policy DRL structures suffer from a structural limitation: the size of the network’s output layer is directly coupled to the dimensionality of the action space. In frameworks such as Unity ML-Agents, when an agent’s action specification is modified, it is treated as a new session, breaking compatibility with previously trained models.

Figure 3 visually shows the temporal cost and workflow of training a Traditional Agent when such a design change occurs. Even adding a single action, such as “Jump”, changes the final output dimensionality. As a result, the previously learned parameters cannot be reused; the entire network must be reinitialized and retrained from scratch. As shown in

Figure 3, the agent cannot continue from the performance level of the pre-trained policy (orange curve) but is instead forced to restart learning from the beginning (blue curve). This means that training costs are incurred redundantly whenever the action space changes, leading to substantial resource waste and a significant development bottleneck in game development pipelines where design modifications are frequent.

To address these issues, this study proposes a Modular Reinforcement Learning (MRL) framework that decomposes control of the agent’s behavior into action modules and optimizes them in parallel with specialized objectives. In this structure, even when the action design changes, only the module associated with the modified behavior needs to be retrained or replaced, while the remaining modules can be reused without modification. This design aims to minimize the cost of action-space changes and to better support the flexible, iterative workflows required in game development.

3. Design

This section describes the proposed Modular Reinforcement Learning (MRL) framework for controlling agent behaviors in FPS games.

To make the modular architecture effective in practice, we follow two key design principles. First, in our setting, cross-module dependence is reduced by separating each module’s observation and action interfaces as much as possible. While Movement and Attack are not strictly independent in general FPS settings, we keep module coupling low by restricting each module’s inputs and outputs to its own observation/action subset, rather than conditioning on the other module’s internal representations. Second, although each module performs a specialized role, the modules are trained to coordinate toward a shared global objective (e.g., maximizing survival time or winning the match) under a shared global reward signal.

In this study, the agent’s behavior is decomposed into two modules, Movement and Attack, each represented by an independent policy network with separate parameters. This modular learning approach reduces system complexity while allowing each behavior to be optimized individually and updated selectively when only a subset of mechanics changes. Furthermore, the reusability and modifiability of behavior modules enable developers to fine-tune granular agent behaviors without retraining the entire agent from scratch.

In particular, we construct the global action by composing module outputs over disjoint action components, which enables parallel execution in our environment.

3.1. System Overview

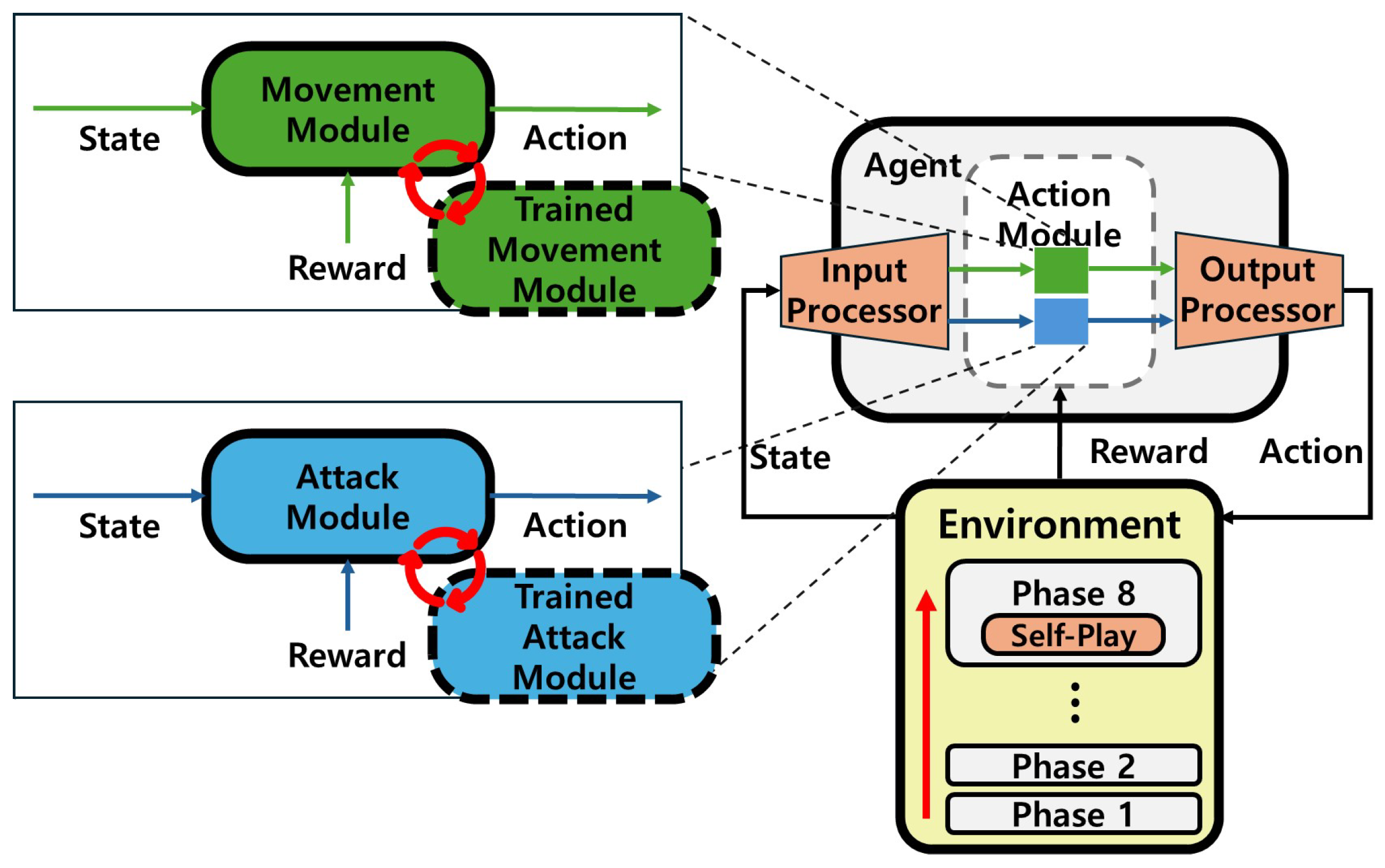

The proposed MRL framework is designed to efficiently learn and flexibly manage complex agent behaviors.

Figure 4 shows the architecture of the Modular Agent, which consists of four key components: the

Agent,

Input Processor,

Output Processor, and decoupled

Action Modules.

The Input Processor analyzes the environmental state to determine which information is required for each module and then routes the appropriate data subset to the corresponding modules. Developers define in advance the types of information required according to the function of each module. For instance, the Movement Module requires only information regarding obstacles and target positions, whereas the Attack Module primarily utilizes information about the target’s presence and distance. Through this process, each module receives only the minimum necessary information as input, thereby improving sample efficiency during learning. Each Action Module is an independent policy network (with separate parameters) specialized for a specific behavioral unit such as movement or attack. The modules are trained using Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) under the same environment interaction loop, while maintaining separate observation and action interfaces. Trained modules can be saved and reused across iterations. Because the module interfaces are standardized, modifying an existing behavior or introducing a new one only requires retraining the affected module, without retraining the entire agent. In our FPS environment, the agent’s action space A is represented as a product of independent action components. Specifically, we define (i) Movement, which controls locomotion and orientation, and (ii) Attack, which determines whether to trigger firing as a binary signal. These components are treated as orthogonal action dimensions in our control interface: changing locomotion parameters does not alter the semantics or dimensionality of the firing command. This factorization enables parallel composition of module outputs via concatenation in the Output Processor.

The

Output Processor receives the outputs from each Action Module and integrates them into the agent’s final action. In our experimental environment, the Movement and Attack modules operate on disjoint action components and can be executed concurrently. Therefore, the Output Processor composes the global action by directly concatenating the module outputs:

where

denotes the final action executed in the environment at time

t,

and

are the outputs of the Movement and Attack modules, respectively, and ⊕ denotes concatenation. This composition enables parallel execution without additional arbitration logic or control conflicts.

In practical game deployments, designers may impose state-dependent constraints (e.g., disabling locomotion during a heavy-attack animation or enforcing cooldown rules). Although not used in our experiments, the Output Processor can optionally incorporate a lightweight runtime constraint-enforcement layer that filters or corrects module outputs based on game-state rules before execution. This design is conceptually aligned with shielding in safe reinforcement learning, where an external component monitors the agent’s proposed actions and intervenes only when an action would violate a given specification [

13]. Concretely, the constraint-enforcement layer can perform runtime invalid-action filtering for discrete controls (e.g., disabling the firing trigger during cooldown) and gating/projection for continuous controls (e.g., suppressing locomotion during animation-locked states), without modifying the internal policies of each module.

Finally, the Agent acts as the integrated manager of the entire structure, coordinating the modules and handling the interface with the environment. At every time step, the agent collects the state from the environment and passes it to the Input Processor, executes the actions determined by the modules in the environment, distributes the resulting rewards to each module, and manages episode terminations, thereby performing the entire reinforcement learning cycle.

3.2. Workflow

To describe the workflow of an agent using the proposed modular framework, we adopt standard reinforcement learning notation defined as follows.

t represents a discrete time step.

denotes the state vector observed from the environment at time

t,

denotes the action determined by the policy

, and

represents the reward received after executing the action.

signifies the state at the next time step. To specify the modular structure, components assigned to specific modules (e.g., Movement, Attack) are distinguished using superscripts, such as

,

, and

. At time

t, the environment generates a state vector

observable by the agent. This state includes information such as the positions of surrounding objects detected via Unity ML-Agents, the relative direction of the target, and the distribution of obstacles. The state

is passed to the Input Processor inside the agent, where it is partitioned into multiple state sub-vectors according to the information required by each Action Module. For instance, the Movement Module receives inputs necessary for pathfinding, such as obstacle positions and destination coordinates, whereas the Attack Module receives information such as the target’s location and whether it is within range. Each module then predicts an action through its dedicated policy network based solely on the specific state subset provided to it. The Movement Module outputs forward speed and rotation direction as

, and the Attack Module determines whether to attack (0 or 1) as

. In our experimental setting, these outputs correspond to separate control components, and the final global action

is composed by the Output Processor as described in

Section 3.1. The resulting action vector is executed in the Unity environment. After action execution, the environment returns the corresponding reward

and the next state

, which are then used by the agent to update the policy of each module. By repeating this process at every time step, each module progressively optimizes its behavioral objective.

3.3. Selective Retraining and Module Reuse

A key advantage of the proposed MRL framework is its capability for efficient, selective retraining when game mechanics or balance parameters are modified. Unlike monolithic policies that necessitate complete retraining from scratch even for minor adjustments, our modular design allows developers to update only the specific modules affected by the change while reusing pre-trained components. This efficiency is demonstrated in our experiments, where the reward structure is modified to include a penalty for missed shots. For the Traditional Agent (T), this shift in the reward signal requires a full re-initialization and retraining of the entire network to produce a new agent, . In contrast, for the Modular Agent (M), the change primarily affects the firing logic. Consequently, we can freeze the parameters of the previously trained Movement module () and reuse it without further updates. Only the Attack module is re-initialized and retrained under the new reward structure to create an updated module, . The final, updated modular agent, , is then formed by integrating the reused Movement module with the newly retrained Attack module ().

4. Implementation

This section describes the implementation details of both the Traditional Agent used as a baseline and the proposed Modular Agent used in our experiments.

4.1. Platform and Environment

For our experiments, we developed a custom FPS game environment using the Unity engine. Both the Traditional Agent (with a Monolithic Policy) and the Modular Agent were trained using the Unity ML-Agents Toolkit.

Table 1 summarizes the hardware and software specifications used for implementation and training.

4.2. Modular Agent

In the proposed framework, the agent is decomposed into two semantic modules, Movement and Attack. Each module is implemented as an independent policy network with separate parameters and its own observation/action interface. The two module outputs are then composed by the Input/Output Processors to operate cohesively as a single agent during execution.

4.2.1. Movement Module

The

Movement Module is responsible for controlling the agent’s locomotion and rotation. Its primary functions include pathfinding, target search, and target tracking. To perceive targets and obstacles within the frontal field of view, the module utilizes the 3D Ray Perception Sensor provided by the Unity ML-Agents Toolkit. Unlike image-based vision sensors, this sensor efficiently detects objects by casting a set of rays and encoding information about hit objects and distances.

Table 2 summarizes the configuration parameters of the ray perception sensor used to obtain these environmental observations. Based on the settings in

Table 2, the agent utilizes 13 rays (calculated as

). Each ray is encoded as a vector of size 4 (comprising a one-hot encoding of 2 detectable tags, normalized distance, and a hit flag), resulting in a base dimensionality of 52 from the ray sensor alone [

11].

The observation space for the Movement Module is configured as shown in

Table 3 to facilitate effective target tracking and navigation. Consequently, combined with the 11 scalar inputs listed in

Table 3, the total observation dimensionality for the Movement Module is 63.

4.2.2. Attack Module

The

Attack Module is responsible for executing attack actions when the target enters the agent’s effective range. Unlike the Movement Module, velocity information is not directly relevant to the firing decision and is therefore omitted. Consequently, the observation space is streamlined to include only the agent’s pose and relative target information. As a result, combined with the scalar inputs listed in

Table 4, the total observation dimensionality for the Attack Module is 8.

4.3. Traditional Agent

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed MRL framework, a

Traditional Agent employing a

Monolithic Policy was implemented as a baseline. This agent manages both movement and attack with a single monolithic policy implemented as one unified neural network, without any structural separation between behaviors. Thus, it receives the full state vector—encompassing all observations required for both behaviors—simultaneously as input, and its action space is designed to produce both movement and attack actions. To rigorously control for experimental fairness and eliminate observation confounds, the Traditional Agent was provided with the exact union of the manually filtered feature sets used by the Modular Agent. The resulting observation space is summarized in

Table 5. Combining the 52-dimensional ray-sensor inputs with the 11 scalar features, the total observation dimensionality for the Traditional Agent is 63. This ensures that the Traditional Agent operates on an identical set of high-quality engineered features, preventing any disadvantage regarding input information. Consequently, the observed performance gap is attributable solely to the architectural capability to process these features efficiently, rather than discrepancies in data quality.

5. Experimental Environment

This section describes the training environment and experimental procedures for both the Traditional Agent and the proposed Modular Agent.

5.1. Agents

All agents in the training environment are initialized with 100 health points (HP). A successful attack reduces the target’s HP by 25, and victory is achieved when the target’s HP reaches 0.

5.2. Reward Structure

The rewards are designed according to the distinct roles and action spaces of the Traditional Agent and the Modular Agent. First, the

Traditional Agent must simultaneously perform movement, attack, and survival; therefore, it utilizes an integrated reward structure that jointly incentivizes target elimination, survival, and exploration, as detailed in

Table 6. Here, MaxStep denotes the maximum number of simulation steps in an episode, and the time-step penalty and spotting reward are normalized by this value.

In the modular framework, the

Movement Module plays a comprehensive role that includes locomotion, view control for attack positioning, and survival. Accordingly, the Movement Module adopts the same reward configuration as the Traditional Agent (

Table 7). By contrast, the

Attack Module functions as the executor of attacks within the opportunities created by the Movement Module; its reward structure (

Table 8) retains key objectives such as “Kill the target”, “Death”, and the time-step penalty to align with the agent’s global goal. However, since the Attack Module cannot control the agent’s position, rewards for “Spot the target” and penalties for being “Damaged”—which depend primarily on movement—are excluded to reduce training noise and enhance attack efficiency. While the Attack Module does not control positioning, the decision of when to engage is intrinsically linked to the agent’s survival and victory. For instance, neutralizing a threat quickly is the most effective way to prevent death. Therefore, providing these global rewards ensures that the module learns tactical firing policies aligned with the match outcome, rather than optimizing solely for local metrics like accuracy.

5.3. Training Environment Setup

Training is conducted in a single-agent environment using curriculum learning to mitigate reward sparsity in the early stages and to stabilize exploration. Each phase presents progressively more difficult objectives, enabling the agent to learn detection, aiming, and pathfinding in stages. Across all phases, the primary objective is to eliminate the target. Phases 1–4 take place in an obstacle-free environment (as shown in

Figure 5), whereas Phases 5–8 are conducted in a more complex environment with obstacles. Phase transitions are automated using the Unity ML-Agents curriculum mechanism. Specifically, a rolling-window average of cumulative rewards is used to trigger progression from Phase

i to Phase

, ensuring that transitions occur only after the agent achieves statistical proficiency in the current task. Detailed curriculum parameters, including the transition thresholds and lesson lengths, are provided in

Table A3 in

Appendix A. Furthermore, the comprehensive list of PPO hyperparameters and specific neural network architectures for each module (Movement, Attack, and Total) are summarized in

Table A1 and

Table A2. In the final phase, the agent competes against itself using self-play. This design reflects the inherently adversarial nature of FPS combat and prevents the agent from overfitting to a fixed scripted opponent. Self-play provides the agent with experience analogous to human learning in competitive environments, where training against an opponent of similar skill level is often most effective [

14]. This approach helps the agent discover its weaknesses and continuously optimize its combat strategy.

Phase 1—Eliminate target in front: The agent is spawned at the center of the combat zone, with a stationary target directly in front. The goal is to learn basic shooting mechanics.

Phase 2—Find and eliminate off-center target: The target is placed in front but offset from the agent’s central line of sight. The agent learns to adjust its aim and attack.

Phase 3—Eliminate randomly spawned target: The target is spawned at a random location within a specified range. The agent must scan the arena to locate and eliminate the target.

Phase 4—Eliminate moving target: This phase adds movement to the target introduced in Phase 3. The agent learns to track and attack a wandering target.

Phase 5—Eliminate moving target with obstacles: Obstacles are introduced into the environment (

Figure 5). The agent learns to navigate around obstacles while locating the target.

Phase 6—Eliminate target on the opposite side: The agent spawns at one of eight designated points, and the target spawns at the opposite location. The agent learns long-distance navigation and tracking.

Phase 7—Eliminate fast-moving target (advanced): The target’s movement speed and action frequency are increased. The agent learns to engage highly dynamic targets.

Phase 8—Agent vs. agent (self-play): The agent spawns at a random point and competes against another instance of itself spawned at the opposite point. This phase uses the Unity ML-Agents self-play feature (see

Table A4 for settings) to refine combat tactics.

Figure 5.

FPS game environment.

Figure 5.

FPS game environment.

Table 9 summarizes the experimental setup. Agents are trained for a total of 30 million steps. The self-play matches in Phase 8 are conducted as 1-vs-1 combat simulations and terminate when one agent achieves four successful attacks within the 100-s time limit. To verify the efficiency of the modular method, we train agents under two reward settings. The

Without-Miss-Penalty setting applies the standard reward (

Table 6). Conversely, the

With-Miss-Penalty setting introduces an additional penalty for missed shots. For the Traditional Agent, applying this new penalty requires reinitializing and retraining the entire network, as the previously learned policy cannot be directly adapted. In contrast, for the Modular Agent, since the change is limited to the attack logic, the Movement Module (trained without the miss penalty) is reused, and only the Attack Module is retrained. For clarity, we use the following notation. The Traditional Agent is denoted by

T, and the Modular Agent by

M (composed of

for Attack and

for Movement). Subscripts indicate the reward setting: the subscript 1 denotes the

Without-Miss-Penalty setting, and the subscript 2 denotes the

With-Miss-Penalty setting. Consequently, the four agents used in the experiments are

,

,

(

), and

(

).

6. Evaluation

In this section, we evaluated whether the proposed modular agent provides greater flexibility and performance than the traditional agent.

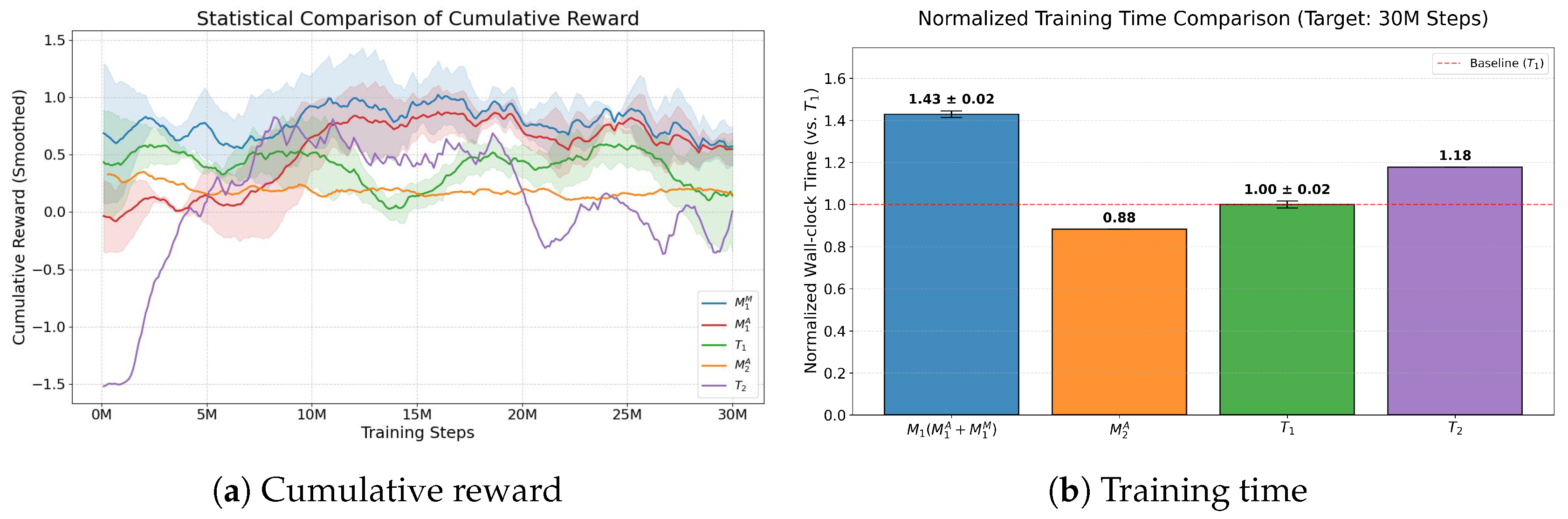

6.1. Training Cost Comparison

Given that game development pipelines frequently undergo design changes, we compare both the initial training time and the retraining time required after modifying the agent’s behavior. In this experiment, the training time for each agent is measured as the elapsed wall-clock time under the setup described in

Table 9. To ensure the reliability of our results, all initial training experiments (

and

) are conducted over three independent runs using different random seeds.

Figure 6a shows the mean cumulative reward for these models, with shaded regions representing the standard deviation to illustrate training stability. For the retrained models (

and

), we present a single illustrative run to demonstrate the effectiveness of the retraining process, given the stability confirmed in the initial phase.

Figure 6b reports the normalized mean active wall-clock time required for each agent to reach 30 million steps, using the monolithic agent (

) as the baseline.

Figure 6a shows that all agents and modules successfully learn policies consistent with the designed reward structures and converge to stable reward levels. Compared with the Traditional Agent and the Movement Module, the Attack Modules exhibit lower absolute cumulative rewards. This difference is primarily attributed to the inherent nature of the Attack Module’s action space, which offers fewer opportunities to obtain rewards. Furthermore, in the case of the retrained module

, the additional penalty for missed shots further reduces the achievable cumulative reward. Despite these lower absolute values,

Figure 6a confirms that the Attack Modules successfully converge to a stable policy, indicating effective learning within their specific functional constraints.

As shown in

Figure 6b, the Modular Agent requires approximately 1.43 times more wall-clock time than the Traditional Agent (

) to initially train both modules (

and

). This initial overhead in wall-clock time arises primarily from the increased computational complexity and redundant feature processing. In contrast to the single integrated network of the Traditional Agent, the Modular Agent must execute independent forward and backward passes for multiple neural networks (

and

) at each training step. Furthermore, since there is no shared backbone for feature extraction, both modules redundantly process overlapping environmental observations, such as enemy coordinates and spatial features.

However, the Modular Agent offers long-term efficiency by enabling the reuse of trained modules. When only a single module (the Attack Module in this experiment) needs to be retrained, the dimensionality of the relevant observation and action spaces is substantially reduced. Consequently, the training time for the new Attack Module () is shortened to 0.88 relative to the baseline. In contrast, retraining the Traditional Agent () requires 1.18 times the baseline time, as its network structure and dimensionality remain unchanged. This difference represents a 0.30 gap in a single retraining cycle, which accumulates as model updates are repeated. This demonstrates that the Modular Agent adapts more flexibly and efficiently than the Traditional Agent when responding to changes in reward structures.

6.2. Inference Latency Analysis

While the modular architecture provides significant advantages in retraining efficiency, it is important to ensure that the execution of multiple independent modules does not introduce prohibitive computational overhead during real-time gameplay. To verify this, we evaluated the inference latency of both the Modular and Monolithic agents. As detailed in

Table A5 in

Appendix A, the modular agent (composed of Movement and Attack modules) maintains a total inference latency of 0.876 ms. This represents a marginal increase of only 0.064 ms compared to the 0.812 ms of the monolithic Traditional Agent. Considering that a standard 60 FPS game loop allows for a frame budget of approximately 16.6 ms, an inference time of less than 1 ms is well within the requirements for real-time deployment. This efficiency is attributable to the reduced capacity of the specialized modular networks. By utilizing smaller hidden layers (128–256 units) for specific tasks, the modular framework compensates for the overhead of executing separate policies, as summarized in the network configuration details (

Table A2 in

Appendix A). These results show that the proposed framework achieves high flexibility and retraining efficiency without compromising runtime performance.

6.3. Performance: Against a Fixed Opponent

To evaluate the baseline performance and training stability of the proposed modular framework, we conducted an experiment against a common enemy that follows a fixed path. Each agent is required to land four attacks within a 100-s time limit to succeed in an episode. We evaluated four agents (, , , and ) over a total of 1000 independent episodes. To ensure statistical reliability, the resulting data are partitioned into 10 blocks of 100 episodes each. The mean and standard deviation (Std) are calculated across these blocks for three key metrics: Success Rate, Accuracy (Hit Rate), and Playtime. This block-based analysis illustrates both the performance consistency and the training stability of each framework.

The experimental results in

Table 10 reveal notable differences in how each architecture incorporates reward signals. Without the miss penalty, the monolithic agent (

) exhibits unstable performance, achieving a success rate of 48.8 ± 4.9%. In contrast, the modular agent (

) maintains a stable baseline under the same conditions, with a success rate of 98.1 ± 1.4%.

The primary objective of introducing the miss penalty is to refine firing precision without disrupting other well-functioning behaviors. While the monolithic agent with the miss penalty () reaches a 100% success rate and improves hit rate (12.3 ± 0.5%), the sharp increase from T1’s baseline suggests a substantial and global shift in its underlying policy rather than a targeted refinement. This indicates that, in a monolithic structure, reward signals associated with firing can easily propagate into and reshape movement strategies, as both behaviors are optimized jointly within a single network.

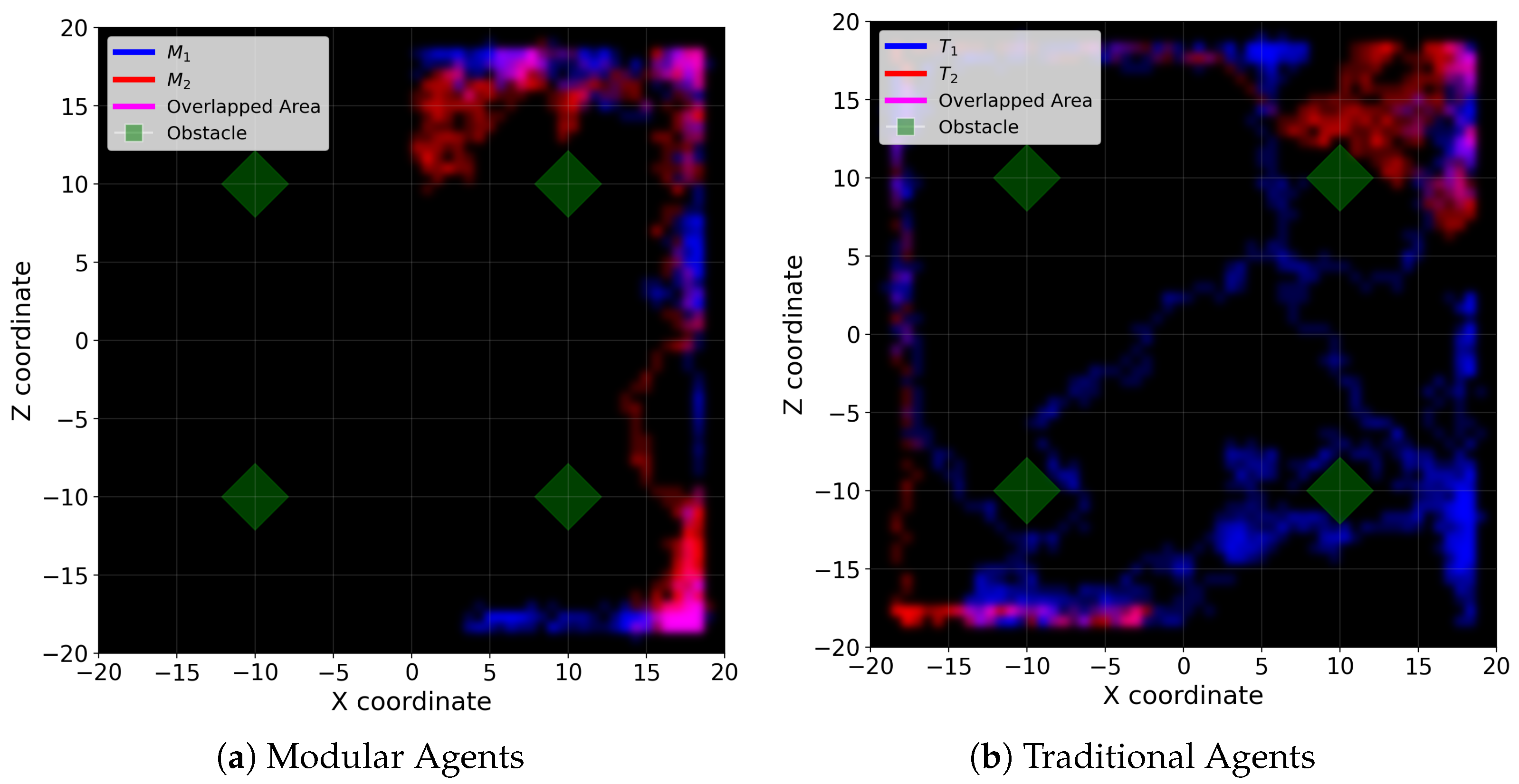

Figure 7 illustrates the movement trajectories of each agent during combat. As shown in

Figure 7b,

exhibits a movement pattern that is substantially different from that of

, indicating that the reward signal associated with hit-rate objective affects not only attack behavior but also other behaviors such as movement. In contrast, as shown in

Figure 7a,

demonstrates a movement pattern similar to that of

.

In practical game development, behaviors such as movement, exploration, and positioning are often carefully tuned to level design, pacing, and gameplay balance, and unintended changes to these behaviors can significantly disrupt the player experience. Accordingly, improvements to firing performance should not come at the cost of altering other established behaviors. From this perspective, the modular agent () demonstrates a more incremental and localized response to the same reward modification. It maintains a consistently high success rate of 99.0 ± 1.1% while increasing firing hit rate from 8.3% () to 9.7% (), closely aligning with the intended effect of the miss penalty. By preventing firing-related reward signals from interfering with movement or search behaviors at the optimization level, the proposed modular framework ensures that the agent’s policy remains consistent with the original design intent. This functional decoupling enables a more predictable and controlled optimization process compared to the monolithic approach.

6.4. Comparative Analysis of Combat Efficiency: Head-to-Head

We evaluated the tactical proficiency and combat efficiency of the Traditional and Modular Agents through head-to-head 1-vs-1 combat experiments. We consider four agent matchups and run 1000 matches for each scenario. Two matchups pair agents trained under identical reward settings (

vs.

,

vs.

), while the others compare agents trained under different reward settings (

vs.

,

vs.

). To ensure statistical reliability, results are analyzed across 10 blocks of 100 episodes each.

Table 11 summarizes combat performance in the 1-vs-1 training map.

The results on the training map show that modular agents consistently achieve higher win rates than traditional agents across all matchups. This demonstrates that the proposed modular architecture provides stable combat performance even in direct engagement scenarios. These findings suggest that reward modifications for firing failures are integrated differently depending on the architecture.

In previous experiments against fixed opponents, both traditional and modular agents demonstrate increased accuracy when a miss penalty was applied. This indicates that in static environments, where the opponent behavior remains constant, such rewards effectively improve firing precision. However, in competitive environments where opponents respond actively (e.g., 1-vs-1), the two architectures exhibit divergent responses to the same reward modification. According to

Table 11,

shows an improvement in hit rate compared to

, whereas

a records lower hit rate than

. This suggests that the impact of a miss penalty varies significantly by architecture in competitive settings.

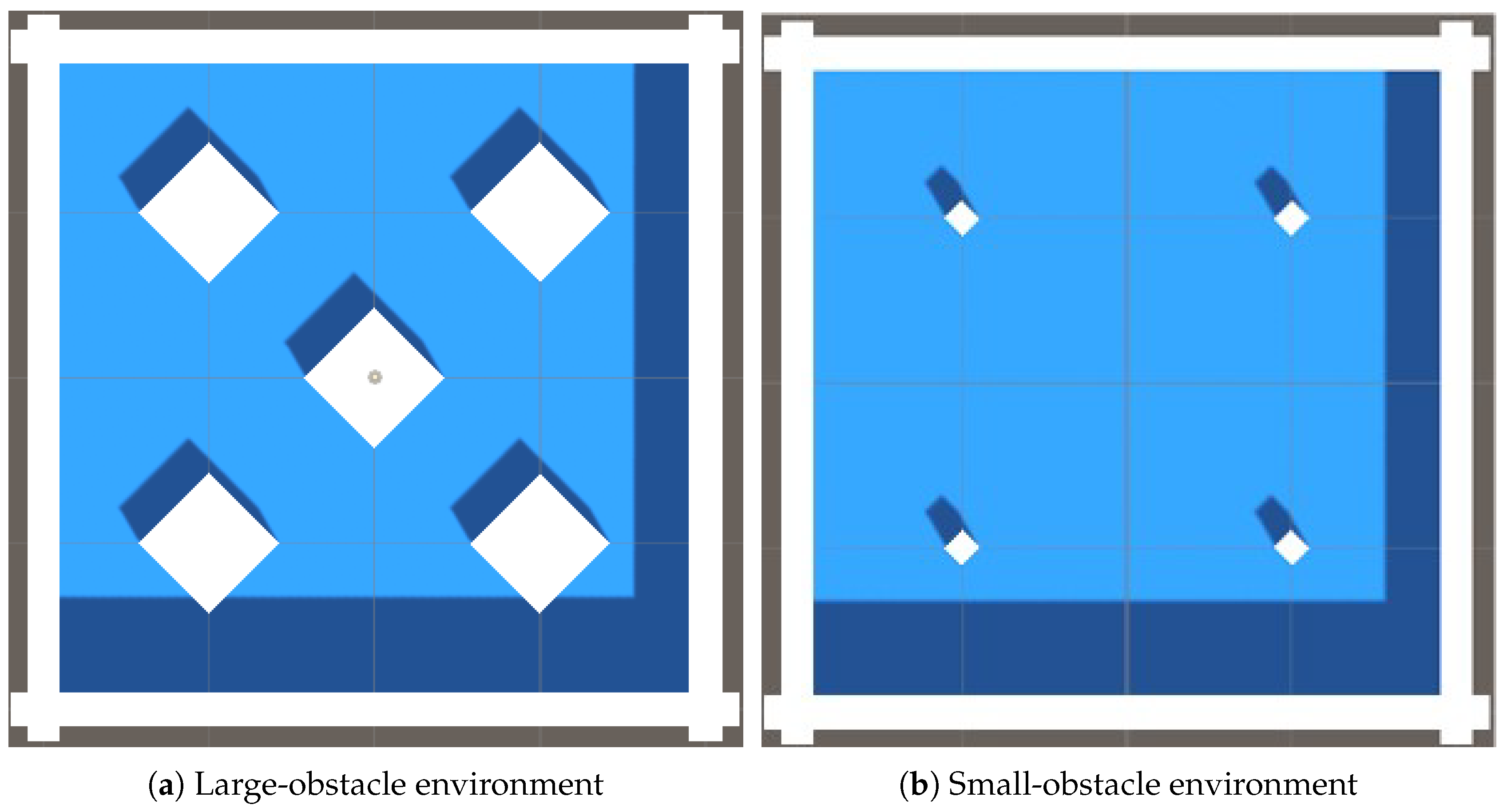

To determine whether these observations are map-specific or intrinsic to the architectural designs, we extend our evaluation to environments with varying obstacle configurations. As illustrated in

Figure 8a, the large-obstacle environment is characterized by increased obstacle dimensions and the addition of an obstacle. In contrast, the small-obstacle environment shown in

Figure 8b retains the same number of obstacles but with reduced sizes.

In the large-obstacle map, the traditional agent exhibits a relative increase in win rate compared to the training map. In particular, as shown in

Table 12 for Case 4 (

vs.

), the win rate of the traditional agent increases noticeably relative to the baseline environment. However, this improvement in win rate is not accompanied by an increase in hit rate; instead, the overall hit rate tends to decrease because visual occlusion is strengthened by the increased obstacle size and the addition of an obstacle. This trend can be further interpreted in conjunction with the movement trajectory analysis shown in

Figure 7. As illustrated in

Figure 7b,

exhibits a preference for movement paths that remain close to obstacles, thereby reducing exposure after the application of the miss penalty. In the large-obstacle environment, this obstacle-adjacent movement pattern aligns with the strengthened cover structure, improving survivability and reducing unfavorable engagements. As a result, even though the hit rate decreases, overall combat performance in terms of win rate improves.

In contrast, in the small-obstacle map, the number of obstacles remains unchanged while their sizes are reduced, leading to weaker visual occlusion and more frequent direct engagements. Under these conditions, the advantage conferred by obstacle-adjacent movement diminishes, and the relative win-rate improvement observed for the traditional agent in the large-obstacle environment correspondingly decreases. As shown in

Table 13, the modular agent regains its overall performance lead in this setting.

Notably, the modular agent maintains consistent movement patterns regardless of changes in obstacle size or placement, and both hit rate and win rate remain relatively stable across environments. This indicates that reward modifications targeting firing accuracy (as reflected by hit rate) do not interfere with movement behavior in the modular architecture. In summary, whereas the combat performance of traditional agents—both win rate and hit rate—varies substantially with environmental configurations, modular agents demonstrate robust behavioral traits and stable performance across diverse obstacle settings. These results provide quantitative evidence that the two architectures respond differently to the same miss-penalty reward under varying environmental conditions.

6.5. Scalability: 2-vs-2 Team Combat

To evaluate the scalability of the learned policies, we conducted 2-vs-2 combat experiments using the models originally trained for 1-vs-1 scenarios. Without dedicated fine-tuning or complex coordination logic, each agent followed a simple heuristic to target the nearest opponent. Similar to the 1-vs-1 setup, four configurations were tested over 1000 independent episodes, partitioned into 10 blocks of 100 episodes for statistical analysis. In this environment, the win rate is determined at the team level, while the hit rate represents the average accuracy of the two agents within the same team. The experimental results are summarized in

Table 14. The modular framework demonstrated a more pronounced advantage in team-based combat compared to the 1-vs-1 scenarios. In Case 3 (

vs.

), the modular team achieved its highest win rate of

, indicating that the specialized attack module effectively exploits the coordination weaknesses of monolithic agents. A critical observation is found in Case 4 (

vs.

), where both teams were trained with the miss penalty. While the win rate gap narrowed (

vs.

), the modular team achieved a significantly higher hit rate of

, compared to

for the traditional team. This suggests that as the number of agents and the complexity of the combat environment increase, the modular architecture’s ability to maintain high-precision fire control becomes a decisive factor in combat quality, even when the final outcomes are relatively balanced.

7. Related Work

Research on developing DRL agents for FPS game environments has been actively studied on various platforms, including ViZDoom, DeepMind Lab, and Unity ML-Agents [

9]. Existing studies are broadly categorized into monolithic end-to-end policies and structured approaches that introduce architectural factorization, temporal abstraction, or explicit modularity.

The monolithic policy approach aims to maximize performance using a single neural network trained end-to-end. In the ViZDoom environment, one study applied the ACKTR algorithm with Kronecker-factored Approximate Curvature (K-FAC) and demonstrated superior sample efficiency, reward maximization, and survival rates compared to A2C [

5]. In DeepMind Lab, population-based deep reinforcement learning in a 3D maze environment enabled large numbers of agents to compete and evolve, achieving human-level behavioral diversity and high win rates, including complex map exploration and defensive strategies beyond simple shooting [

3]. Despite strong benchmark performance, monolithic policies pose practical limitations in iterative game development pipelines. First, the learned policy behaves as a “black box,” making it difficult to interpret behaviors or to incorporate explicit designer intentions. Second, because the output layer is tightly coupled to the action-space specification, adding/removing actions or modifying only part of the behavior typically changes the network interface and often requires full retraining, leading to substantial time and computational overhead during frequent patching and balancing.

To improve training efficiency under monolithic policies, various techniques have been proposed. Curriculum learning [

6] alleviates initial reward sparsity by gradually adjusting task difficulty or goals, and behaviour cloning [

15] stabilizes the initial policy by mimicking expert demonstrations. However, these techniques primarily improve the learning process and do not directly address the maintainability issue of monolithic policies under iterative action/behavior updates.

Structured approaches attempt to mitigate these limitations by introducing decomposition. One direction is to factorize the action representation within a single policy, e.g., multi-head or branching architectures, which decompose the joint action into multiple action components to improve scalability and reduce interference across unrelated control dimensions [

16]. While such factorization is beneficial for large action spaces, substantial parameter sharing often remains, and selective retraining is not guaranteed unless modular boundaries and interfaces are explicitly enforced.

Another direction is temporal abstraction via options or skills. The options framework formalizes temporally extended actions and enables hierarchical decision-making over reusable skills [

17], and end-to-end variants (e.g., Option-Critic) learn option policies and terminations jointly [

18]. These methods are effective for long-horizon problems, yet the discovered skills and latent sub-goals are not always aligned with designer-defined semantic units, making controlled behavior editing and targeted replacement challenging in practical development workflows.

Compositional and modular RL further focuses on building complex behaviors by composing reusable subpolicies. For example, policy sketches provide high-level symbolic structures to guide the reuse of modular subpolicies across tasks [

19], and composable modular RL studies mechanisms for combining learned modules for transfer and generalization [

20]. These approaches share the goal of reusability and interpretability, but often require either explicit task programs/sketches or learned arbitration mechanisms to select among modules.

Hierarchical reinforcement learning (HRL) also decomposes complex tasks using a Manager–Worker structure [

21]. In FPS settings, a study applying an RNN-based DRQN model in ViZDoom separated the agent’s task into navigation and combat phases and trained distinct networks for each [

4]. However, such phase-based decomposition can rely on predefined switching conditions (e.g., enemy detected vs. not), which may limit flexibility when tactics and mechanics evolve. More generally, HRL often defines sub-goals implicitly in latent spaces, which can complicate explicit designer control and make selective reuse of worker behaviors dependent on the high-level goal representation.

In contrast to the temporal decomposition characteristic of options and HRL, where sub-policies are executed sequentially, our framework employs semantic action-space decomposition. Instead of learning when to switch between latent sub-goals, we decompose the agent’s architecture into two explicit semantic modules (Movement and Attack) that operate concurrently. This design explicitly avoids the complexity of termination conditions and aligns with practical game development workflows, enabling independent behavior tuning and selective retraining of only the affected module under iterative updates.

8. Conclusions

In this study, we designed and implemented a Modular Reinforcement Learning (MRL) framework that trains movement and attack behaviors, with the explicit goal of improving development efficiency under frequent and iterative updates in FPS game development, while addressing the training inefficiency and lack of structural flexibility inherent in traditional agents employing a monolithic policy. By decoupling the input spaces according to the specific objectives and roles of each module, we established a structure in which each module selectively processes only the information relevant to its task. This design improves training stability by allowing the Movement and Attack modules to optimize their policies without mutual interference. Furthermore, by integrating the outputs of these specialized modules into a single agent, we achieve a level of flexibility in modification, replacement, and retraining that is difficult to realize with monolithic policy approaches.

Our experimental results demonstrate the superior combat performance of the modular agent, which achieved a maximum win rate of 83.4% against the traditional agent on the 1-vs-1 training map. Moreover, the modular agent maintained consistently high win rates even in novel environments with varying obstacle configurations. Notably, in complex terrains, the traditional agent exhibited unintended shifts in its movement strategy during training—such as failing to close the distance to the opponent and defaulting to overly evasive behavior—whereas the modular agent maintained stable, task-appropriate movement across environments. In addition, owing to the structural advantage that allows selective retraining of specific behavior modules, we observed that retraining time was reduced by up to 30% compared to the traditional agent when modifying reward structures or behavioral logic, directly supporting rapid iteration and maintenance in practical game development workflows.

Future work will extend the framework to include more fine-grained behavioral modules, such as “target visibility maintenance” and “tactical distance control.” We also plan to enhance the expressiveness and controllability of the framework by designing reward structures that explicitly reinforce cooperative mechanisms between modules.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.L. and H.S.; methodology, S.L.; software, S.L.; validation, S.L.; formal analysis, S.L.; investigation, S.L.; resources, H.S.; data curation, S.L.; writing—original draft preparation, S.L.; writing—review and editing, H.S.; visualization, S.L.; supervision, H.S.; project administration, H.S.; funding acquisition, H.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by a 2023 Research Grant from Sangmyung University (2023-A000-0010).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Detailed Training Configurations and Technical Analysis

This appendix provides comprehensive technical details to ensure the reproducibility of our experimental results. It includes PPO hyperparameters, specific neural network architectures, curriculum stages, and a computational efficiency analysis.

Appendix A.1. Hyperparameters and Network Architectures

To maintain training stability and sample efficiency across all agents, we utilized the standard PPO hyperparameters summarized in

Table A1. The architectural complexity of each module was adjusted according to its functional role; the Movement module utilizes a larger capacity to handle spatial navigation, while the Attack module is streamlined for efficient firing logic (

Table A2).

Table A1.

Common PPO hyperparameters for all agents.

Table A1.

Common PPO hyperparameters for all agents.

| Hyperparameter | Value |

|---|

| Trainer Type | PPO |

| Batch Size | 2048 |

| Buffer Size | 20,480 |

| Learning Rate | 0.0003 |

| Beta (Entropy Regularization) | 0.005 |

| Epsilon (Clipping) | 0.2 |

| Lambda (GAE) | 0.95 |

| Number of Epochs | 3 |

| Learning Rate Schedule | Constant |

| Extrinsic Gamma () | 0.999 |

| Time Horizon | 1000 |

| Max Steps | 30,000,000 |

Table A2.

Neural network configuration for each behavior module.

Table A2.

Neural network configuration for each behavior module.

| Behavior Module | Hidden Units | Number of Layers |

|---|

| Movement (Modular) | 256 | 3 |

| Attack (Modular) | 128 | 2 |

| Total (Monolithic) | 512 | 3 |

Appendix A.2. Curriculum Learning and Simulation Settings

Table A3.

Curriculum learning stages and completion criteria.

Table A3.

Curriculum learning stages and completion criteria.

| Stage | Completion Criteria |

|---|

| Stage 0 | Threshold: 0.7, Min Lesson Length: 100 episodes |

| Stage 1 | Threshold: 0.7, Min Lesson Length: 100 episodes |

| Stage 2 | Threshold: 0.7, Min Lesson Length: 100 episodes |

| Stage 3 | Threshold: 0.7, Min Lesson Length: 100 episodes |

| Stage 4 | Threshold: 0.7, Min Lesson Length: 100 episodes |

| Stage 5 | Threshold: 0.7, Min Lesson Length: 100 episodes |

| Stage 6 | Threshold: 0.7, Min Lesson Length: 100 episodes |

| Stage 7 | Final Stage (No transition) |

Table A4.

Self-play and engine simulation settings.

Table A4.

Self-play and engine simulation settings.

| Setting Item | Value |

|---|

| Initial ELO | 1200.0 |

| Self-Play Swap Steps | 200,000 |

| Checkpoint Interval | 2,000,000 |

| Time Scale (Simulation Speed) | 20 |

| Target Frame Rate | −1 (Unlimited) |

| Capture Frame Rate | 60 |

Appendix A.3. Inference Latency Analysis

Table A5.

Comparison of empirical inference latency.

Table A5.

Comparison of empirical inference latency.

| Agent/Module | Inference Latency (ms) |

|---|

| Movement (Modular) | 0.651 |

| Attack (Modular) | 0.225 |

| Modular Agent | 0.876 |

| Monolithic Agent | 0.812 |

References

- Al-Hamadani, M.N.A.; Al-Hudar, H.M.; Allen, T. Reinforcement Learning Algorithms and Applications in Healthcare and Robotics: A Comprehensive and Systematic Review. Sensors 2024, 24, 2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jebessa, E.; Teshale, G.; Lee, K. Analysis of reinforcement learning in autonomous vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 12th Annual Computing and Communication Workshop and Conference (CCWC), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 26–29 January 2022; pp. 496–502. [Google Scholar]

- Jaderberg, M.; Czarnecki, W.M.; Dunning, I.; Marris, L.; Lever, G.; Castañeda, A.G.; Beattie, C.; Rabinowitz, N.C.; Morcos, A.S.; Ruderman, A.; et al. Human-level performance in 3D multiplayer games with population-based reinforcement learning. Science 2019, 364, 859–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lample, G.; Chaplot, D.S. Playing FPS games with deep reinforcement learning. In Proceedings of the 31st AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI), San Francisco, CA, USA, 4–9 February 2017; pp. 2140–2146. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, K.; Zhao, D.; Li, N.; Zhu, Y. Learning battles in ViZDoom via deep reinforcement learning. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Conference on Computational Intelligence and Games (CIG), Maastricht, The Netherlands, 14–17 August 2018; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Tian, Y. Training agent for first-person shooter game with actor-critic curriculum learning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), Toulon, France, 24–26 April 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, P.; Carvalho, V.; Simões, A. Reinforcement Learning as an Approach to Train Multiplayer First-Person Shooter Game Agents. Technologies 2024, 12, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, M.; Devlin, S.; Hofmann, K. “It’s unwieldy and it takes a lot of time”—Challenges and opportunities for creating agents in commercial games. In Proceedings of the 16th AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Interactive Digital Entertainment (AIIDE), Online, 19–23 October 2020; pp. 223–229. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, P.; Carvalho, V.; Simões, A. Reinforcement Learning Applied to AI Bots in First-Person Shooters: A Systematic Review. Algorithms 2023, 16, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- François-Lavet, V.; Henderson, P.; Islam, R.; Bellemare, M.G.; Pineau, J. An introduction to deep reinforcement learning. Found. Trends Mach. Learn. 2018, 11, 219–354. [Google Scholar]

- Unity Team. The ML-Agents GitHub Page. Available online: https://github.com/Unity-Technologies/ml-agents (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Schulman, J.; Wolski, F.; Dhariwal, P.; Radford, A.; Klimov, O. Proximal policy optimization algorithms. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1707.06347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshiekh, M.; Bloem, R.; Ehlers, R.; Könighofer, B.; Niekum, S.; Topcu, U. Safe Reinforcement Learning via Shielding. In Proceedings of the 32nd AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI), New Orleans, LA, USA, 2–7 February 2018; pp. 2669–2678. [Google Scholar]

- Unity Technologies. Training Intelligent Adversaries Using Self-Play with ML-Agents. Available online: https://unity.com/blog/engine-platform/training-intelligent-adversaries-using-self-play-with-ml-agents (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Hagen, J. Agent Participation in First Person Shooter Games Using Reinforcement Learning and Behaviour Cloning. Ph.D. Thesis, Breda University of Applied Sciences, Breda, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Tavakoli, A.; Pardo, F.; Kormushev, P. Action Branching Architectures for Deep Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the 32nd AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI), New Orleans, LA, USA, 2–7 February 2018; pp. 4131–4138. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton, R.S.; Precup, D.; Singh, S. Between MDPs and Semi-MDPs: A Framework for Temporal Abstraction in Reinforcement Learning. Artif. Intell. 1999, 112, 181–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacon, P.L.; Harb, J.; Precup, D. The Option-Critic Architecture. In Proceedings of the 31st AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI), San Francisco, CA, USA, 4–9 February 2017; pp. 1726–1734. [Google Scholar]

- Andreas, J.; Klein, D.; Levine, S. Modular Multitask Reinforcement Learning with Policy Sketches. In Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), Sydney, Australia, 6–11 August 2017; pp. 166–175. [Google Scholar]

- Simpkins, C.; Isbell, C. Composable Modular Reinforcement Learning; Technical Report; Georgia Institute of Technology: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Song, S.; Weng, J.; Su, H.; Dong, D.; Ma, Z.; Zhu, J. Playing FPS Games with Environment-Aware Hierarchical Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the 28th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI), Macao, China, 10–16 August 2019; pp. 3475–3481. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

Deep Reinforcement Learning.

Figure 1.

Deep Reinforcement Learning.

Figure 2.

The ’Black Box’ Model of Monolithic Policy DRL.

Figure 2.

The ’Black Box’ Model of Monolithic Policy DRL.

Figure 3.

Retraining Overhead Caused by Action Space Expansion (Adding ‘Jump’ Action).

Figure 3.

Retraining Overhead Caused by Action Space Expansion (Adding ‘Jump’ Action).

Figure 4.

Architecture of the modular agent.

Figure 4.

Architecture of the modular agent.

Figure 6.

Comparison of agent training. (a) Cumulative reward curves demonstrating the learning stability of initial models (, ). Solid lines represent the mean of 3 runs, and shaded areas indicate the standard deviation. For the retrained models (, ), a single representative run is shown. (b) Comparison of normalized active wall-clock time required to reach 30 million training steps, relative to the monolithic baseline ().

Figure 6.

Comparison of agent training. (a) Cumulative reward curves demonstrating the learning stability of initial models (, ). Solid lines represent the mean of 3 runs, and shaded areas indicate the standard deviation. For the retrained models (, ), a single representative run is shown. (b) Comparison of normalized active wall-clock time required to reach 30 million training steps, relative to the monolithic baseline ().

Figure 7.

Movement trajectories before and after reward modification. (a) Modular agents: M1 and M2 exhibit similar trajectories, indicating that reward modification does not alter the movement policy. (b) Traditional agents: The shift from T1 to T2 shows that reward modification influences the movement policy.

Figure 7.

Movement trajectories before and after reward modification. (a) Modular agents: M1 and M2 exhibit similar trajectories, indicating that reward modification does not alter the movement policy. (b) Traditional agents: The shift from T1 to T2 shows that reward modification influences the movement policy.

Figure 8.

Test environments different from the training map. (a) Large-obstacle environment. (b) Small-obstacle environment.

Figure 8.

Test environments different from the training map. (a) Large-obstacle environment. (b) Small-obstacle environment.

Table 1.

Hardware and software specifications for the experimental setup.

Table 1.

Hardware and software specifications for the experimental setup.

| Hardware/Software | Specification |

|---|

| CPU | Intel(R) Core(TM) i5-10400F CPU @ 2.90 GHz |

| RAM | 16 GB |

| GPU | NVIDIA GeForce GTX 1650 |

| ML-Agents release | Release 22 |

| ML-Agents Unity package | 2.3.0 |

| ML-Agents Python package | 0.30.0 |

| Python | 3.8.0 |

| PyTorch | 2.1.0 |

Table 2.

Agent’s sensor’s settings.

Table 2.

Agent’s sensor’s settings.

| Description | Value |

|---|

| Rays per direction | 6 |

| Max ray degrees | 90 |

| Sphere cast radius | 0.5 |

| Ray length (Unity units) | 60 |

| Stacked raycasts | 1 |

| Start vertical offset | 0 |

| End vertical offset | 0 |

| Num Detectable Tags | 2 |

Table 3.

Observation space for the Movement Module.

Table 3.

Observation space for the Movement Module.

| Type | Description |

|---|

| Agent’s Position (3 floats) | The agent’s current 3D coordinates |

| Agent’s Rotation in degrees (1 float) | The agent’s current y Euler angle |

| Agent’s Velocity (3 floats) | The agent’s current Velocity |

| Direction to Target (3 floats) | The agent’s direction to Target |

| Distance to Target (1 float) | The agent’s distance to Target |

Table 4.

Observation space for the Attack Module.

Table 4.

Observation space for the Attack Module.

| Observation Type | Description |

|---|

| Agent’s Position (3 floats) | The agent’s current 3D coordinates |

| Agent’s Rotation in degrees (1 float) | The agent’s current y Euler angle |

| Direction to Target (3 floats) | The agent’s direction to Target |

| Distance to Target (1 float) | The agent’s distance to Target |

Table 5.

Observation space for the Traditional Agent.

Table 5.

Observation space for the Traditional Agent.

| Observation Type | Description |

|---|

| Agent’s Position (3 floats) | The agent’s current 3D coordinates |

| Agent’s Rotation in degrees (1 float) | The agent’s current y Euler angle |

| Agent’s Velocity (3 floats) | The agent’s current Velocity |

| Direction to Target (3 floats) | The agent’s direction to Target |

| Distance to Target (1 float) | The agent’s distance to Target |

Table 6.

Training reward for the Traditional Agent.

Table 6.

Training reward for the Traditional Agent.

| Type of Reward | Reward Value |

|---|

| Kill the target | |

| Hit the target | |

| Miss the target | |

| Damaged | |

| Death | |

| Time-step penalty | |

| Spot the target | |

Table 7.

Training reward for the Movement Module.

Table 7.

Training reward for the Movement Module.

| Type of Reward | Reward Value |

|---|

| Kill the target | |

| Hit the target | |

| Miss the target | |

| Damaged | |

| Death | |

| Time-step penalty | |

| Spot the target | |

Table 8.

Training reward for the Attack Module.

Table 8.

Training reward for the Attack Module.

| Type of Reward | Reward Value |

|---|

| Kill the target | |

| Hit the target | |

| Miss the target | |

| Death | |

| Time-step penalty | |

Table 9.

Experimental setup.

Table 9.

Experimental setup.

| Element | Details |

|---|

| Combat format | 1-vs-1 combat simulation |

| Match duration | 100-s time limit |

| Agent training steps | 30 million steps |

| Agent positioning | Random start from 8 designated locations |

| Without-Miss-Penalty setting | No penalty for missed shots |

| With-Miss-Penalty setting | Penalty of per missed shot (B: total bullets) |

Table 10.

Comparison of agent performance against a fixed-path opponent. Values represent the mean ± standard deviation calculated over 10 blocks of 100 episodes each (total 1000 episodes).

Table 10.

Comparison of agent performance against a fixed-path opponent. Values represent the mean ± standard deviation calculated over 10 blocks of 100 episodes each (total 1000 episodes).

| Agent | Success Rate (%) | Hit Rate (%) | Avg. Playtime (s) |

|---|

| | | 31.47 |

| | | 34.36 |

| | | 76.35 |

| | | 28.02 |

Table 11.

Combat results for modular (M) and traditional (T) agents on the training map (1-vs-1).

Table 11.

Combat results for modular (M) and traditional (T) agents on the training map (1-vs-1).

| Matchup Case | Agent | Win Rate (%) | Hit Rate (%) | Play Time (s) |

|---|

| Case 1 | | | | |

| ( vs. ) | | | | |

| Case 2 | | | | |

| ( vs. ) | | | | |

| Case 3 | | | | |

| ( vs. ) | | | | |

| Case 4 | | | | |

| ( vs. ) | | | | |

Table 12.

Combat results for modular (

M) and traditional (

T) agents on the

Figure 8a (1-vs-1).

Table 12.

Combat results for modular (

M) and traditional (

T) agents on the

Figure 8a (1-vs-1).

| Matchup Case | Agent | Win Rate (%) | Hit Rate (%) | Play Time (s) |

|---|

| Case 1 | | | | |

| ( vs. ) | | | | |

| Case 2 | | | | |

| ( vs. ) | | | | |

| Case 3 | | | | |

| ( vs. ) | | | | |

| Case 4 | | | | |

| ( vs. ) | | | | |

Table 13.

Combat results for modular (

M) and traditional (

T) agents on the

Figure 8b (1-vs-1).

Table 13.

Combat results for modular (

M) and traditional (

T) agents on the

Figure 8b (1-vs-1).

| Matchup Case | Agent | Win Rate (%) | Hit Rate (%) | Play Time (s) |

|---|

| Case 1 | | | | |

| ( vs. ) | | | | |

| Case 2 | | | | |

| ( vs. ) | | | | |

| Case 3 | | | | |

| ( vs. ) | | | | |

| Case 4 | | | | |

| ( vs. ) | | | | |

Table 14.

Combat results for 2-vs-2 team matchups on the training map. Values represent the Mean ± standard deviation calculated over 10 blocks of 100 episodes each.

Table 14.

Combat results for 2-vs-2 team matchups on the training map. Values represent the Mean ± standard deviation calculated over 10 blocks of 100 episodes each.

| Matchup Case | Team Type | Win Rate (%) | Hit Rate (%) | Play Time (s) |

|---|

| Case 1 | | | | |

| ( vs. ) | | | | |

| Case 2 | | | | |

| ( vs. ) | | | | |

| Case 3 | | | | |

| ( vs. ) | | | | |

| Case 4 | | | | |

| ( vs. ) | | | | |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |