1. Introduction

Globally, power systems are rapidly transitioning toward sustainable and low-carbon energy portfolios. As the penetration of renewable energy sources increases, inverter-based resources have become essential components of modern power grids. Unlike synchronous generators, inverter-based resources rely on power electronic interfaces, sensor-based control, and phase-locked loop synchronization, which provide fast dynamic response but reduce physical inertia and complicate voltage and frequency stability, particularly under variable photovoltaic and wind generation conditions [

1].

To ensure reliable interconnection of distributed energy resources, IEEE Std. 1547-2018 specifies technical requirements including voltage and frequency ride through capabilities [

1]. In practice, however, fault ride through performance is strongly influenced by system strength indicators such as the short-circuit ratio, short-circuit capacity, and line impedance characteristics. Weak grids with low short-circuit ratios exhibit amplified voltage deviations and degraded inverter stability, motivating international efforts such as the German FGW guidelines to define minimum system strength criteria for secure operation and harmonic mitigation [

2]. Building on this foundation, several studies have extended short-circuit-based assessment frameworks to distribution systems, including generalized short-circuit ratio monitoring for real-time stability evaluation [

3] and the allocation of synchronous condensers to enhance short-circuit strength [

4]. Complementary research has examined voltage stability mechanisms [

5,

6,

7], reliability challenges in inverter-dominated networks [

8,

9,

10,

11], and the technical and economic implications of distributed energy resource control strategies such as active power curtailment and coordinated operation [

12,

13,

14,

15].

Beyond system strength assessment, increasing attention has been directed toward inverter behavior during grid disturbances. The Electric Power Research Institute has conducted extensive investigations into inverter response under abnormal conditions, including active and reactive current injection, transient overvoltage mitigation, and responses to phase shifts, frequency deviations, and single-phase openings [

16]. In parallel, per-phase reactive power control strategies have been proposed to selectively support faulted phases while suppressing overvoltage in healthy phases during unbalanced fault conditions [

17]. In addition, grid-forming inverter research emphasizes the importance of maintaining operation during severe or asymmetric disturbances to enhance system resilience in low-inertia environments, requiring strengthened real and reactive power control as well as sequence support [

18]. Short-circuit analyses of photovoltaic inverters further indicate that immediate disconnection may forfeit valuable dynamic support capability and can even worsen local voltage depression [

19]. Moreover, analyses of real and reactive power behavior during single-line-to-ground contingencies demonstrate that properly coordinated inverter control can enhance stability when appropriate algorithms are implemented [

20,

21].

Beyond voltage- and protection-oriented studies, advanced control frameworks have been investigated to improve inverter stability under disturbances. While model- and observer-based robust control approaches have shown promising results, their dependence on detailed system models and additional control structures may pose challenges for practical implementation in distribution-level applications [

22]. From a practical distribution system perspective, voltage control algorithms tailored to Korean distribution grids have also been developed using realistic feeder parameters and operating conditions. These studies have demonstrated improved system stability under normal and weak grid conditions; however, their extension to fault ride through enhancement under unbalanced fault scenarios has remained limited [

23].

In parallel, sequence-domain fault control strategies have been actively investigated to address unbalanced fault conditions [

24,

25,

26,

27]. By explicitly regulating positive- and negative-sequence components, these approaches have demonstrated effectiveness in enhancing fault ride through performance and mitigating unbalanced currents in analytical and simulation-based studies [

24,

26,

27].

However, sequence-based control typically requires real-time sequence extraction, additional filtering, and tight coordination with phase-locked loop (PLL) dynamics [

25,

27], which increases the implementation complexity and may introduce delays or stability concerns, particularly in weak distribution networks. As a result, the practical adoption of sequence-based control remains limited at the distribution level [

26], and most deployed distribution inverters continue to rely on locally measured point of common coupling (PCC) voltages for protection and control.

Despite the breadth of existing research, a unified and practically validated control framework for distribution-level inverter-based resources capable of sustaining operation during single-line-to-ground, double-line-to-ground, and three-phase faults under weak grid conditions remains lacking. Many existing studies focus on a limited subset of fault types or do not normalize fault severity, hindering systematic comparison across different contingencies. Consequently, the combined influence of system strength, quantified by the weighted short-circuit ratio and fault ride through performance, has not been sufficiently addressed in distribution networks.

Motivated by these gaps, this study investigated the impact of weighted short-circuit ratio on the fault ride through the capability of smart inverters and evaluated their contribution during single-line-to-ground, double-line-to-ground, and three-phase faults. A detailed MATLAB/Simulink r2021b model of a Korean distribution feeder was developed using actual system parameters. A fault-oriented reactive power compensation strategy is proposed, which selects the minimum phase voltage under unbalanced conditions as the control reference. Fault scenarios were normalized to impose equivalent per-unit voltage depression, enabling fair comparison across fault types. Simulation results demonstrate that the proposed approach mitigates voltage sag in faulted phases, suppresses excessive voltage rise in healthy phases, and maintains stable inverter operation even under extremely weak system strength conditions where conventional approaches may lead to loss of synchronization and inverter tripping after the fault. These findings indicate that actively utilizing the inverter reactive power capability during faults provides a practical pathway to enhance stability in distribution systems with high distributed energy resource penetration.

2. Smart Inverter Functions for Voltage Stability

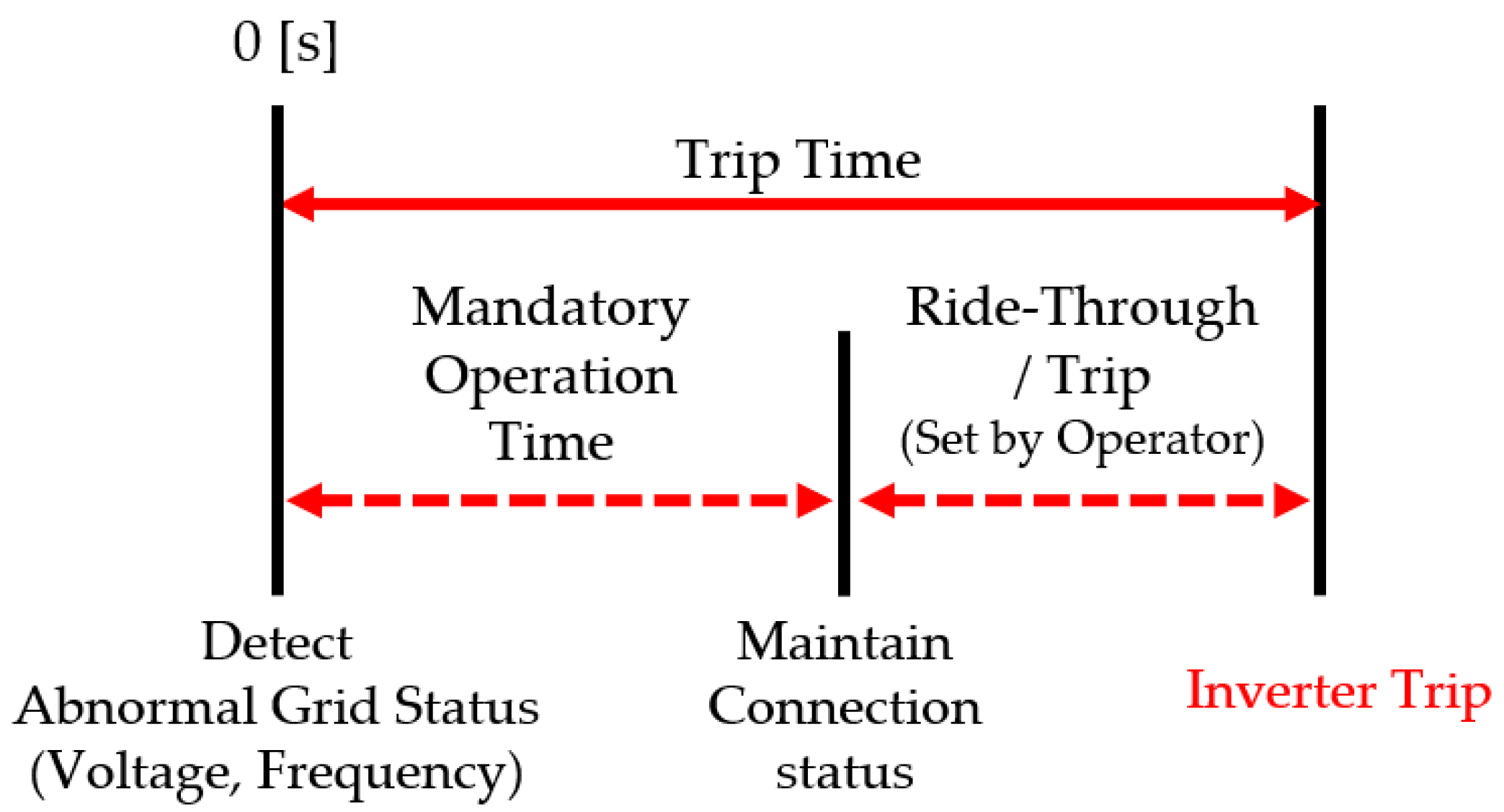

Smart inverters are required to detect abnormal voltage or frequency conditions and determine appropriate actions, including continued operation, temporary ride through, momentary cessation, or grid disconnection. These actions are governed by predefined ride through and disconnection settings established by the grid operator or asset owner.

Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual relationship between abnormal operating conditions and inverter trip time. If the inverter fails to maintain the prescribed operating voltage or frequency ranges beyond the allowable ride through duration, it must cease energization and disconnect from the grid.

2.1. Voltage Ride Through (VRT) Capability

Voltage ride through (VRT) and fault ride through (FRT) functions define the capability of a distributed energy resource to remain connected and operational during abnormal voltage conditions.

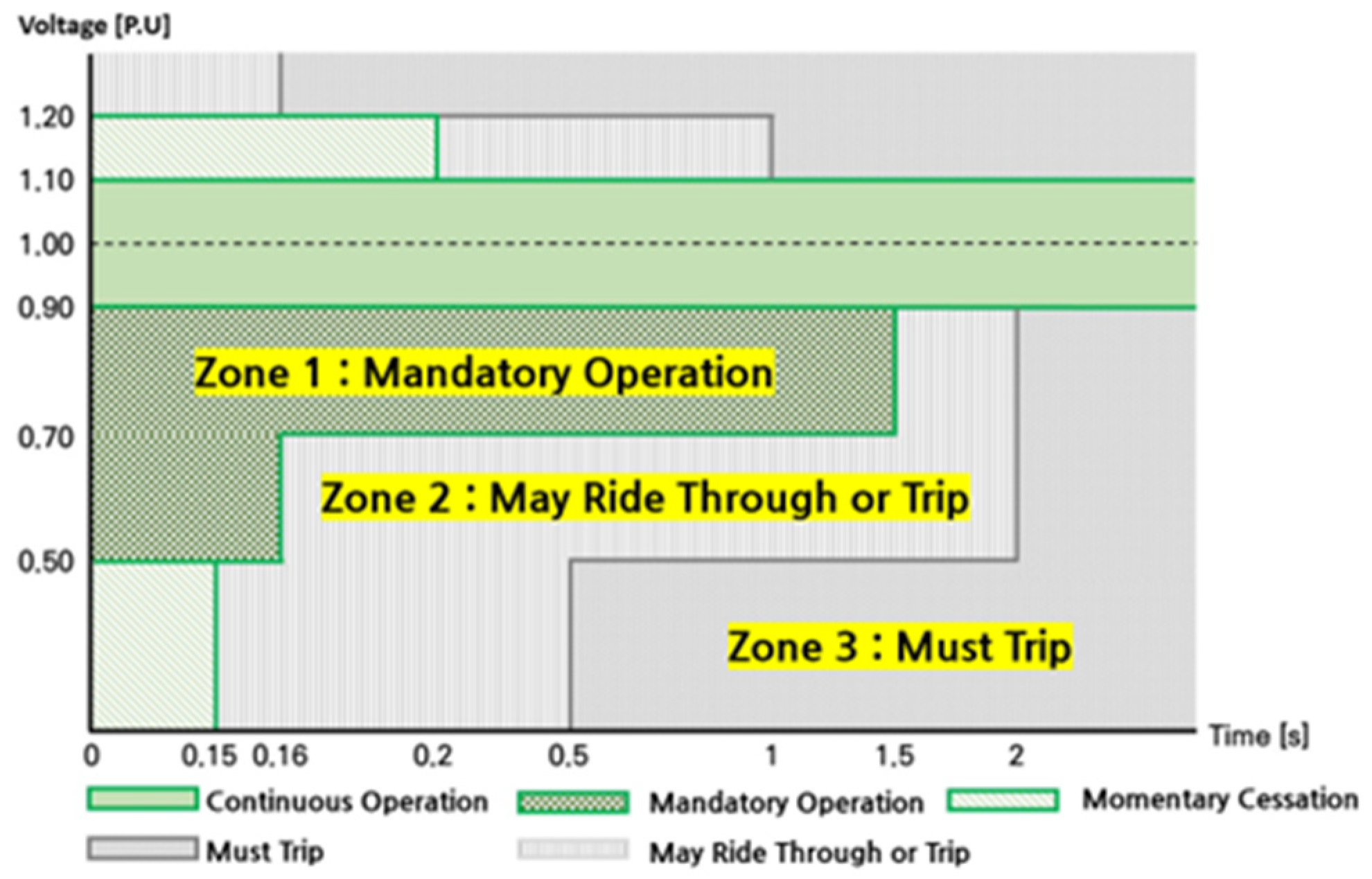

Figure 2 presents the VRT requirements specified by the Korea Smart Grid Association (KSGA), which classifies inverter behavior into continuous operation, ride through, momentary cessation, and trip regions. During continuous operation, the inverter sustains normal output without disconnection. In the ride through region, the inverter remains connected while supplying a specified fraction of its pre-fault current. Momentary cessation permits temporary output reduction, provided that rapid recovery is achieved once the voltage returns to the normal range. If abnormal conditions persist beyond the defined ride through duration, the inverter must disconnect from the grid.

The IEEE Std. 1547-2018 standard further categorizes ride through performance into three categories based on grid reliability requirements. Category I represents minimum ride through capability suitable for low DER penetration, while Categories II and III impose progressively stricter VRT and FRT requirements to support system reliability under higher DER penetration and lower inertia conditions. Category III, in particular, is intended for grids requiring continuous DER operation during severe disturbances and is adopted in regional interconnection rules such as California Rule 21 and Hawaii Rule 14.

In the South Korean context, KSGA guidelines emphasize rapid post-disturbance recovery following temporary voltage events. However, for PLL-based grid-following inverters, reconnection during transient voltage recovery can introduce frequency oscillations and output instability if ride through logic is implemented solely through breaker control without coordinated DC-link management.

2.2. Active and Reactive Power Control and Limitations

Smart inverters regulate their output using locally measured electrical quantities, typically at the point of common coupling or point of interconnection. Communication and supervisory control are supported through standards such as IEC 61850-7-520, enabling both autonomous and coordinated operation. In autonomous mode, the inverter independently determines its output using predefined grid-support parameters, while coordinated operation incorporates remote commands or external signals such as system-level control objectives.

Conventional voltage regulation is commonly achieved through Volt–Var and Volt–Watt control functions. Volt–Var control adjusts reactive power output according to a predefined voltage–reactive power characteristic, supplying capacitive reactive power during undervoltage conditions and absorbing inductive reactive power during overvoltage conditions. Volt–Watt control mitigates overvoltage by reducing active power output once the measured voltage exceeds a specified threshold. These functions are effective for steady-state voltage regulation and slow voltage variations associated with high DER penetration.

However, during fault conditions, conventional Volt–Var and Volt–Watt controls exhibit inherent limitations. Their response is constrained by predefined deadbands, slope settings, and current limits, and they are not explicitly designed to address asymmetric voltage depression or rapidly evolving fault dynamics. As a result, such controls may provide insufficient support during severe or unbalanced faults, particularly in weak distribution networks, motivating the need for fault-oriented control strategies that actively utilize inverter reactive power capability during disturbances.

3. Proposed Methodology

3.1. Weighted Short Circuit Ratio (WSCR) Definition

The short circuit ratio (SCR) has traditionally been used as a fundamental indicator for assessing grid strength and ensuring the stable operation of converter-based resources such as HVDC links and inverter-based resources (IBRs). A high SCR indicates that sufficient short-circuit capacity is available relative to the connected generation, whereas a low SCR implies increased vulnerability to voltage deviations and dynamic instability [

1]. Despite its widespread use, the conventional SCR is defined at a single interconnection point and does not adequately represent distribution systems with multiple distributed energy resources (DERs) of different capacities and locations [

2].

To address this limitation, the weighted short circuit ratio is adopted as a comprehensive system-level strength index. WSCR accounts for both the short-circuit capacity available at each point of common coupling (PCC) and the rated capacity of individual DER units, enabling evaluation of aggregated system robustness under high DER penetration [

3].

In practical implementation, the short-circuit capacity

at the PCC of the

-th inverter is obtained from the Thevenin equivalent of the upstream distribution network. Specifically,

is calculated using the nominal line-to-line voltage

and the equivalent short-circuit impedance

seen from the PCC, expressed as Equation (1):

where

is derived from the network parameters, including feeder impedance, transformer impedance, and upstream grid strength. In this study,

was extracted from the detailed distribution feeder model using actual line resistance and reactance data, and the corresponding

values were computed prior to time-domain simulations. This approach ensures that WSCR reflects realistic site-specific grid conditions rather than assumed or nominal short-circuit levels.

Let

denote the short-circuit capacity [MVA] at the PCC of the

-th inverter and

its rated active power [MW]. The individual short circuit ratio is defined as Equation (2):

The WSCR is then expressed as a capacity-weighted average of individual SCR values as Equation (3):

This formulation shows that WSCR may be interpreted either as a weighted average of individual SCRs or as the ratio of the aggregated short-circuit capacity to the total installed DER capacity. Furthermore, the relative contribution of each DER to the overall WSCR can be quantified as Equation (4):

Therefore, larger DERs connected at electrically strong locations contribute more significantly to system strength, while smaller units or those connected to weak buses have limited impact. This property makes WSCR a practical and scalable extension of the conventional SCR for distribution networks with high renewable penetration [

4].

3.2. WSCR and Voltage Stability Under Fault Conditions

The weighted short circuit ratio provides a direct measure of how robustly a power system can maintain voltage stability under disturbances such as grid faults, load variations, or rapid changes in inverter-based generation. Systems with high WSCR are generally classified as strong grids, in which voltage deviations remain limited during contingencies. Conversely, low WSCR values characterize weak grids, where even moderate disturbances can produce severe voltage sags and prolonged recovery [

1].

As WSCR decreases, the effective Thevenin impedance observed at the PCC increases, amplifying voltage deviations and potentially inducing oscillatory responses. This relationship can be expressed through the conventional SCR formulation as Equation (5):

where

represents the equivalent system capacity or aggregated inverter-based generation connected at the PCC. In practice, planning guidelines often classify systems with WSCR values above 2.0 as sufficiently strong, whereas values below approximately 1.5 are considered weak [

2,

3]. In such weak grids, conventional voltage regulation strategies may become ineffective, necessitating enhanced stabilization measures such as fast reactive current injection, dynamic reactive power control, or supplemental short-circuit support [

4].

3.3. Smart Inverter Model Implementation

This section describes the three-phase grid connected inverter model used in the simulation.

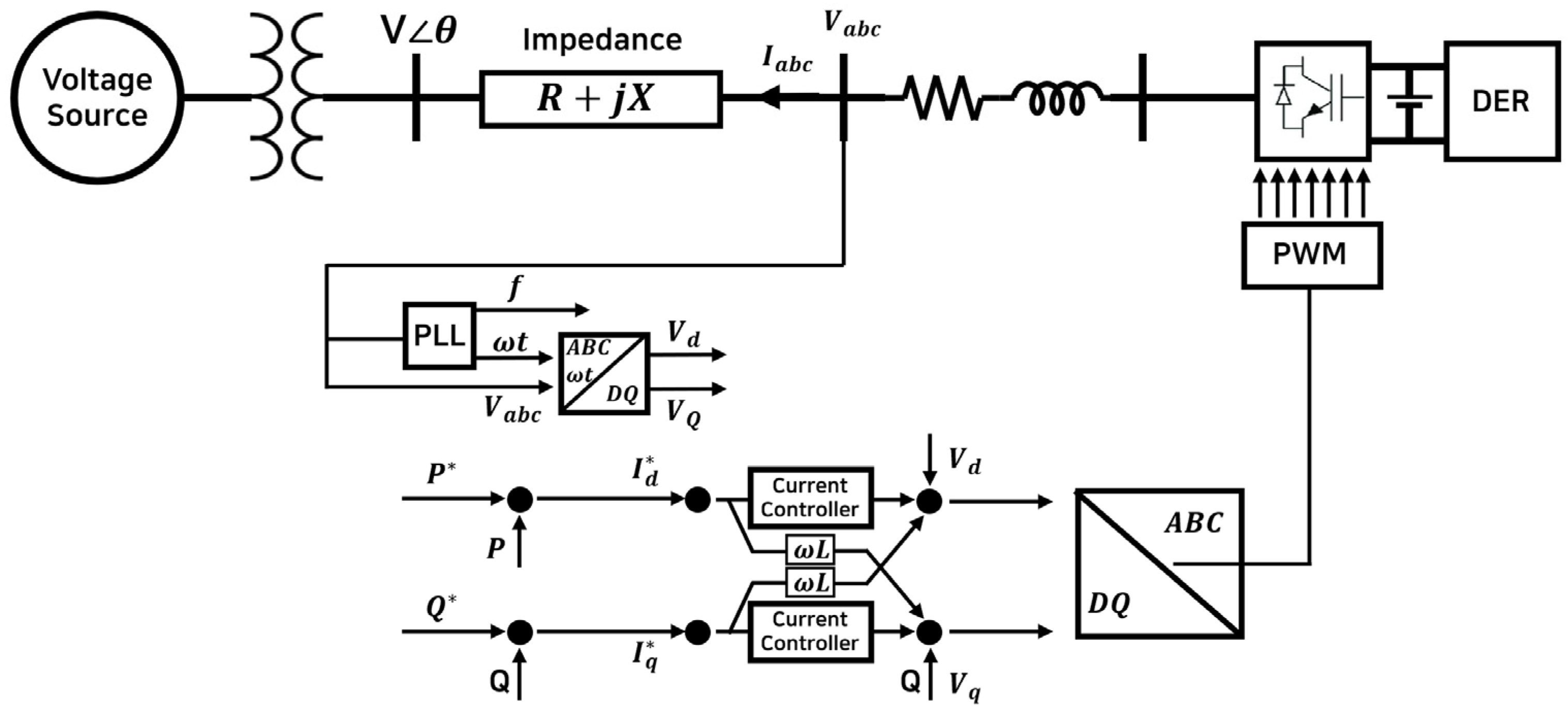

Figure 3 illustrates the overall configuration of the inverter system.

The inverter is composed of six power electronic switches, such as IGBTs or MOSFETs, with two switches allocated per phase. It is supplied by a DC input source such as photovoltaic panels or batteries. To deliver power to the three-phase grid, the inverter converts DC into AC and synchronizes its output with the grid by employing a phase-locked loop (PLL), which extracts the grid frequency and phase angle.

The inverter control system was implemented using a grid-following (GFL) scheme with pulse width modulation (PWM). A triangular carrier wave was compared against a sinusoidal reference waveform, where the reference voltage signal () was derived from the frequency and phase angle () obtained via the phase-locked loop (PLL). Active and reactive power control was achieved using current controllers, in which the reference powers (,) were transformed into current commands tracked by PI controllers.

The resulting currents were converted back to the three-phase ABC frame to generate PWM switching signals, ensuring accurate power delivery to the grid. To guarantee stability under abnormal conditions, the voltage ride through function was incorporated. The controller continuously monitored the per-unit voltages at the PCC, enabling continuous operation within the prescribed limits. During momentary deviations, the inverter entered a temporary cessation state by blocking the PWM signals and disconnected only when the disturbance exceeded the ride through duration.

3.4. Fault-Oriented Reactive Power Compensation Strategy (Q-Compensation)

To enhance fault ride through performance in weak distribution networks, a fault-oriented reactive power compensation strategy is proposed. Unlike conventional Volt–Var control, which is primarily designed for steady-state voltage regulation, the proposed method explicitly targets fault-induced voltage depression and dynamically utilizes the inverter’s reactive power capability.

Let

,

and

denote the RMS voltages of the three phases measured at the point of common coupling (PCC). The control reference voltage is defined as the minimum phase voltage Equation (6):

This selection ensures that reactive power support is directed toward the most severely depressed phase during unbalanced fault conditions, which governs inverter ride through behavior. The reactive power command is determined according to the following piecewise linear characteristic Equation (7):

where

denotes the deadband voltage threshold,

is the lower ride through voltage limit,

is the reactive power gain, and

represents the maximum reactive power capability constrained by the inverter current limits.

In this study, the deadband thresholds were selected to suppress unnecessary reactive power oscillations under normal voltage fluctuations while ensuring prompt activation during fault-induced voltage depression. Specifically, was set to the lower boundary of the deadband , consistent with the Volt–Var deadband adopted in common interconnection practices and with the deadband range used in the implemented Q-V curve . The ride through activation threshold was set to , reflecting the low-voltage region in which reactive support should saturate to its maximum capability during severe sags. With these settings, the controller remains inactive for small voltage variations, initiates proportional reactive power injection once , and reaches when , providing a predictable and bounded response under weak-grid fault conditions.

By relying solely on instantaneous PCC voltage measurements, the proposed strategy does not require fault-type detection or sequence-component decomposition. This avoids the computational burden and potential delays associated with sequence extraction and enhances robustness in weak grids with a low weighted short-circuit ratio. Once the PCC voltage recovers to the normal operating range, the reactive power command is smoothly reset to zero, allowing the inverter to resume normal operation without introducing secondary disturbances.

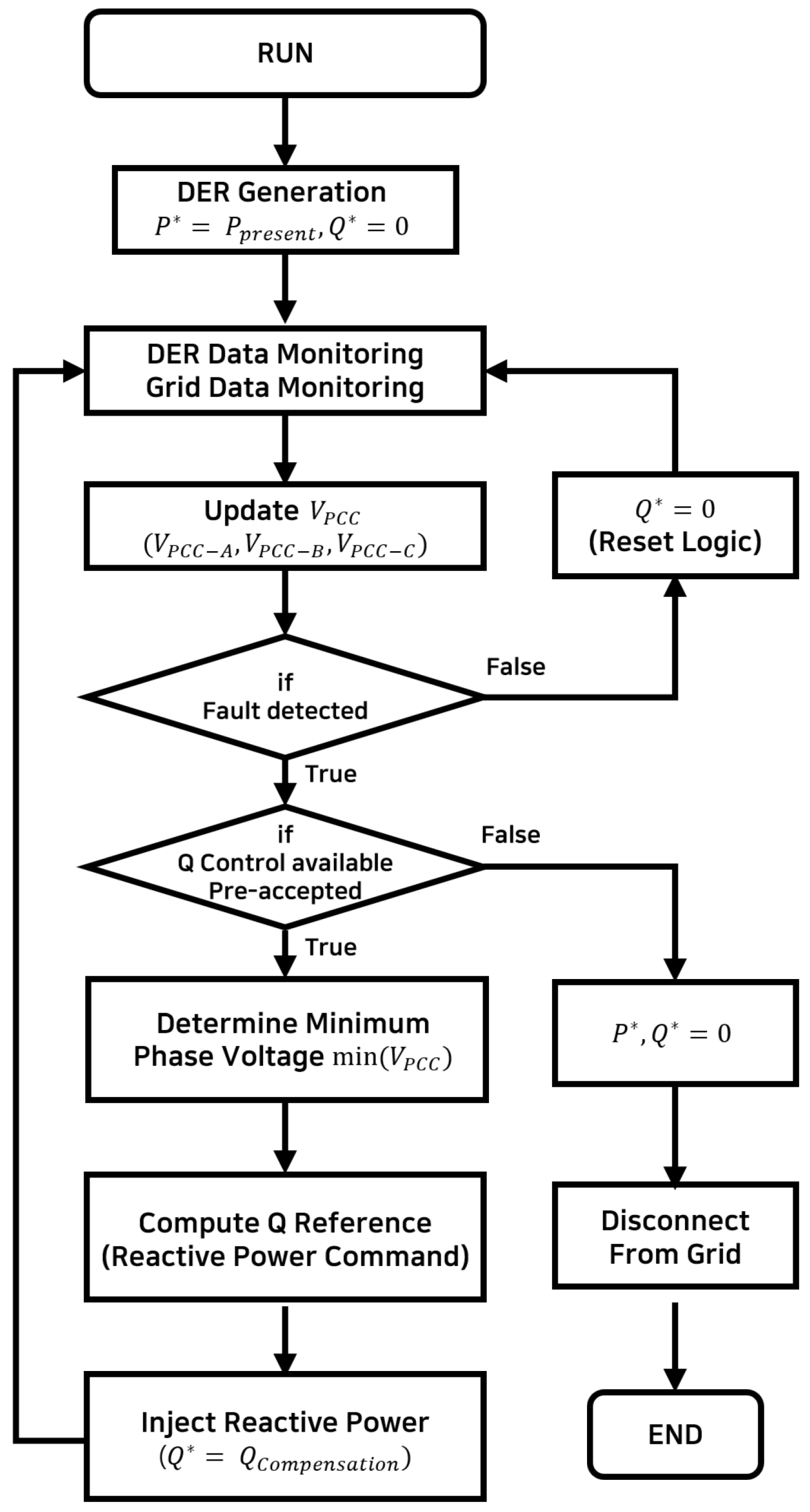

The overall control procedure of the proposed fault-oriented reactive power compensation strategy is summarized in

Figure 4. When a fault is detected based on measured PCC voltages and predefined protection thresholds, the controller first verifies whether the reactive power support is enabled for the inverter. If the reactive support is not permitted, the inverter output is forced to

= 0 and

, and the inverter is disconnected from the grid in accordance with the protection logic. Otherwise, the controller computes

based on the minimum phase voltage and injects reactive power to support voltage recovery during the fault. After voltage recovery, the reset logic smoothly returns

to zero, ensuring a stable transition back to normal operation. Through this process, the inverter provides effective voltage support under both balanced and unbalanced fault conditions while maintaining continuous ride through capability, thereby improving voltage resilience in weak distribution networks.

Figure 4 illustrates the detailed control flow of the proposed fault-oriented reactive power compensation strategy implemented in the smart inverter. The controller initially operates the inverter with the present active power output and zero reactive power. During normal operation, both DER-side and grid-side variables are continuously monitored, and the three-phase PCC voltages are updated in real time.

When an abnormal voltage condition is detected based on predefined protection thresholds, the controller first determines whether the reactive power support is enabled for the inverter. If the reactive support is not permitted, the inverter output is forced to zero and the inverter is disconnected from the grid according to the protection logic. If the reactive power support is available, the controller selects the minimum phase voltage among the three PCC voltages as the reference to capture the most severely depressed phase during the disturbance.

Based on this reference voltage, the reactive power command is computed using the proposed fault-oriented Q-Compensation characteristic and injected to support voltage recovery while remaining within the inverter’s current and power limits. The controller continues this process throughout the fault duration to maintain ride through operation. Once the PCC voltage returns to the normal operating range, or when no fault condition is detected, the reset logic smoothly drives the reactive power command back to zero, allowing the inverter to resume normal operation without introducing secondary transients.

4. Simulation Setup and Results

4.1. Test System Modeling in MATLAB/Simulink

The test system used in this study was implemented in MATLAB/Simulink to evaluate the fault ride through performance of grid-following smart inverters under different system strength conditions.

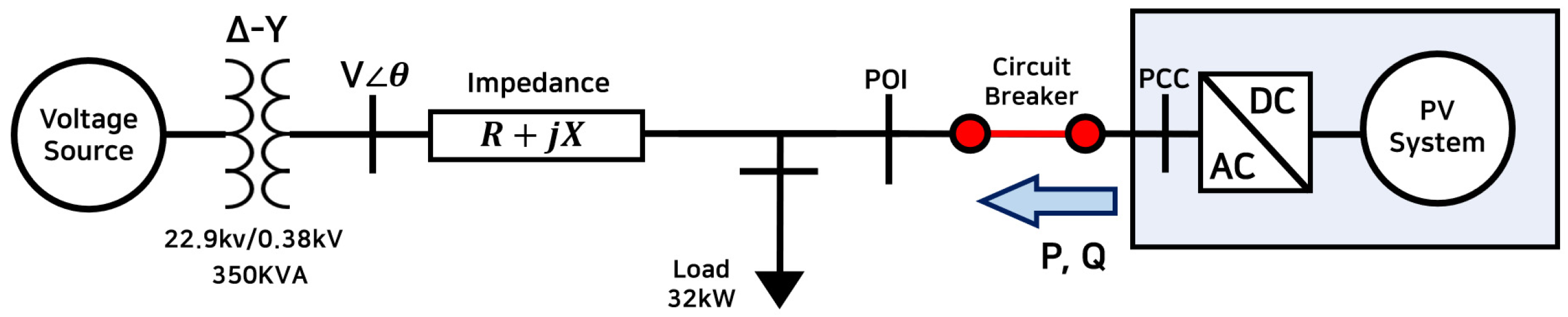

Figure 5 illustrates the simplified single-line diagram of the modeled distribution system, while

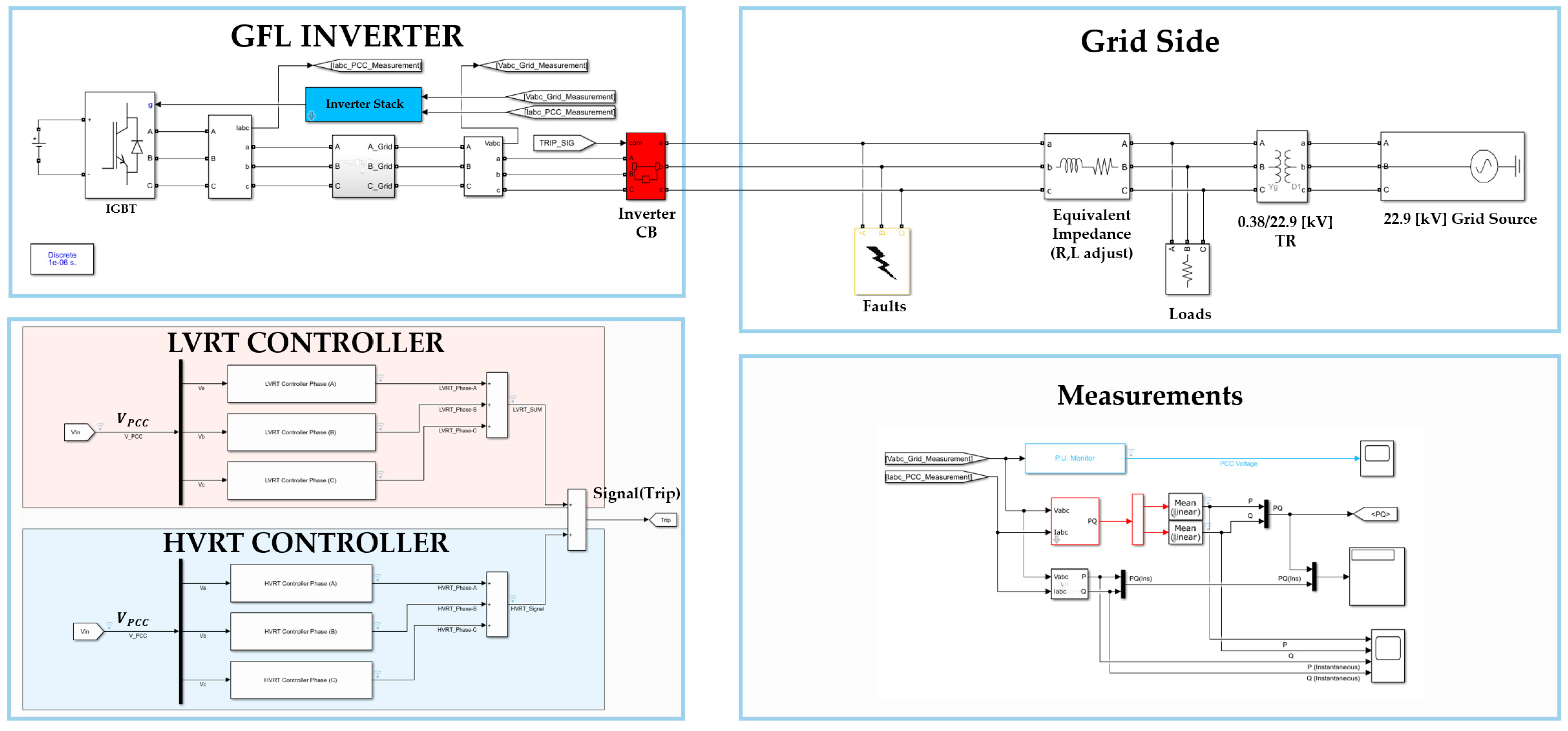

Figure 6 presents the corresponding MATLAB/Simulink implementation used in the simulations.

As shown in

Figure 5, the test system represents a 22.9 kV Korean distribution feeder stepped down to 0.38 kV through a 22.9/0.38 kV transformer. The feeder is modeled using an equivalent Thevenin representation at the point of common coupling (PCC), including lumped line resistance and reactance derived from actual distribution system data. Loads are connected downstream of the PCC, and a grid-following smart inverter interfaced with a photovoltaic (PV) source is connected at the PCC.

Figure 6 shows the detailed MATLAB/Simulink model corresponding to the single-line diagram. The inverter is modeled as a three-phase voltage source converter with a DC-link, PWM switching, and grid-following control based on a phase-locked loop (PLL). Active and reactive power are regulated through d–q current control, and voltage ride through logic is implemented to determine inverter behavior during abnormal voltage conditions. The inverter rating is set to the actual installed capacity of 237.6 kVA, rather than an assumed nominal value, to ensure realistic representation of field conditions.

Using the equivalent feeder parameters and transformer model, the short-circuit capacity (SCC) and X/R ratio at the PCC were calculated. These parameters were then used to determine the weighted short circuit ratio, which serves as the key indicator of system strength throughout the simulation study. By combining the conceptual single-line diagram and the detailed Simulink implementation, the proposed test system provides a consistent and transparent framework for analyzing inverter fault ride through behavior under varying grid robustness levels.

4.2. WSCR-Based Scenario Definition

The Sang-Wol distribution line (D/L) originating from a substation in Jeollabuk-do, South Korea, was selected as the study system for evaluating inverter fault ride through performance under varying grid strength conditions. Based on the MATLAB/Simulink test system described in

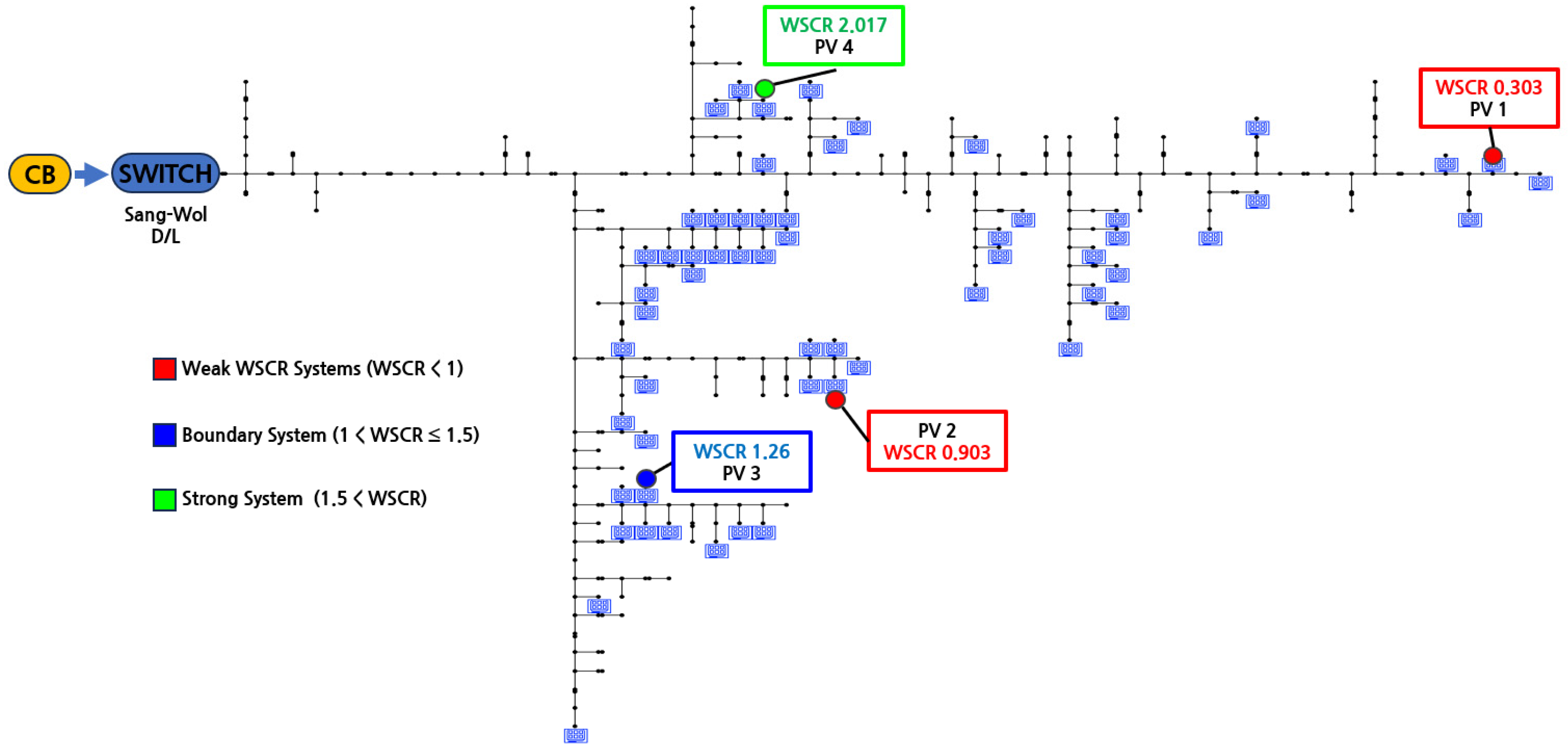

Section 4.1, a set of simulation scenarios was defined by varying the locations of the photovoltaic (PV) systems along the Sang-Wol D/L, as illustrated in

Figure 7, while maintaining the same inverter control structure.

Figure 7 illustrates the single-line diagram of the Sang-Wol D/L together with the selected PV interconnection points. A robustness assessment was first conducted for all candidate buses along the feeder using actual line parameters and load data. For each location, the short-circuit capacity (SCC) and X/R ratio at the point of common coupling were calculated, and the corresponding WSCR was derived. Based on these indices, the feeder was categorized into weak, boundary, and strong grid regions.

Four representative PV locations were selected to span a wide range of WSCR conditions, from extremely weak to relatively strong grid strength. These locations correspond to the cases summarized in

Table 1.

Case 1 represents an extremely weak grid condition with a WSCR of 0.303, while Case 4 corresponds to a strong grid with a WSCR of 2.01. Cases 2 and 3 represent intermediate conditions, capturing the transitional system behavior between weak and strong grids.

The inverter capacity and equivalent network parameters at each location were preserved according to the actual system data. As a result, the changes in WSCR were primarily driven by variations in SCC and feeder impedance rather than the artificial scaling of inverter ratings. This approach ensures that the simulation scenarios reflect realistic deployment conditions in the Korean distribution network.

To evaluate fault ride through performance under comparable stress levels, single-line-to-ground (SLG), double-line-to-ground (DLG), and three-phase-to-ground faults were applied at the PCC. Faults were initiated at 0.2 s and cleared after 0.17 s. The fault resistance and grounding resistance were set to 0.0005 [Ω] and 0.01 [Ω], respectively, which are consistent with typical low-voltage ride through (LVRT) studies in distribution systems. For DLG and three-phase faults, fault parameters were adjusted such that the resulting voltage depression was equivalent, in per-unit terms, to that of the SLG fault, enabling fair comparison across fault types.

Throughout the simulations, PCC voltages, inverter active and reactive power outputs, and ride through behavior were monitored. This WSCR-based scenario design provides a structured framework for isolating the effects of grid strength on inverter stability and voltage support capability under different fault conditions.

In addition to the no-control case, a fixed-capacity reactive power injection scheme was considered as a conservative reference for comparison. This scheme represents a practical operating scenario in which reactive power support is enabled without adaptive fault-oriented control, reflecting a commonly adopted conservative assumption in distribution system operation.

For the fixed-capacity scheme, the reactive power capability was determined based on minimum power factor requirements that are widely specified in grid interconnection practices, typically in the range of 0.95 to 0.98. In this study, the inverter active power rating was 237.6 [kW], and the corresponding reactive power capacities associated with these power factor limits were calculated and summarized in

Table 2. These values represent typical examples of conservatively allocated reactive power support under fixed power factor constraints [

27,

28].

The purpose of introducing this scheme was not to maximize voltage support, but to reflect a conservative operational philosophy commonly applied to grid-following inverters. In practical inverter operation, output control is generally designed to balance two competing objectives: contributing to local voltage stability while simultaneously minimizing voltage fluctuations caused by excessive reactive power injection at individual points of interconnection. Under this philosophy, fixed-capacity reactive power support based on conservative power factor limits provides limited but predictable voltage support, making it suitable as a benchmark for comparison with adaptive fault-oriented control strategies.

4.3. Impact of WSCR on Fault Ride Through

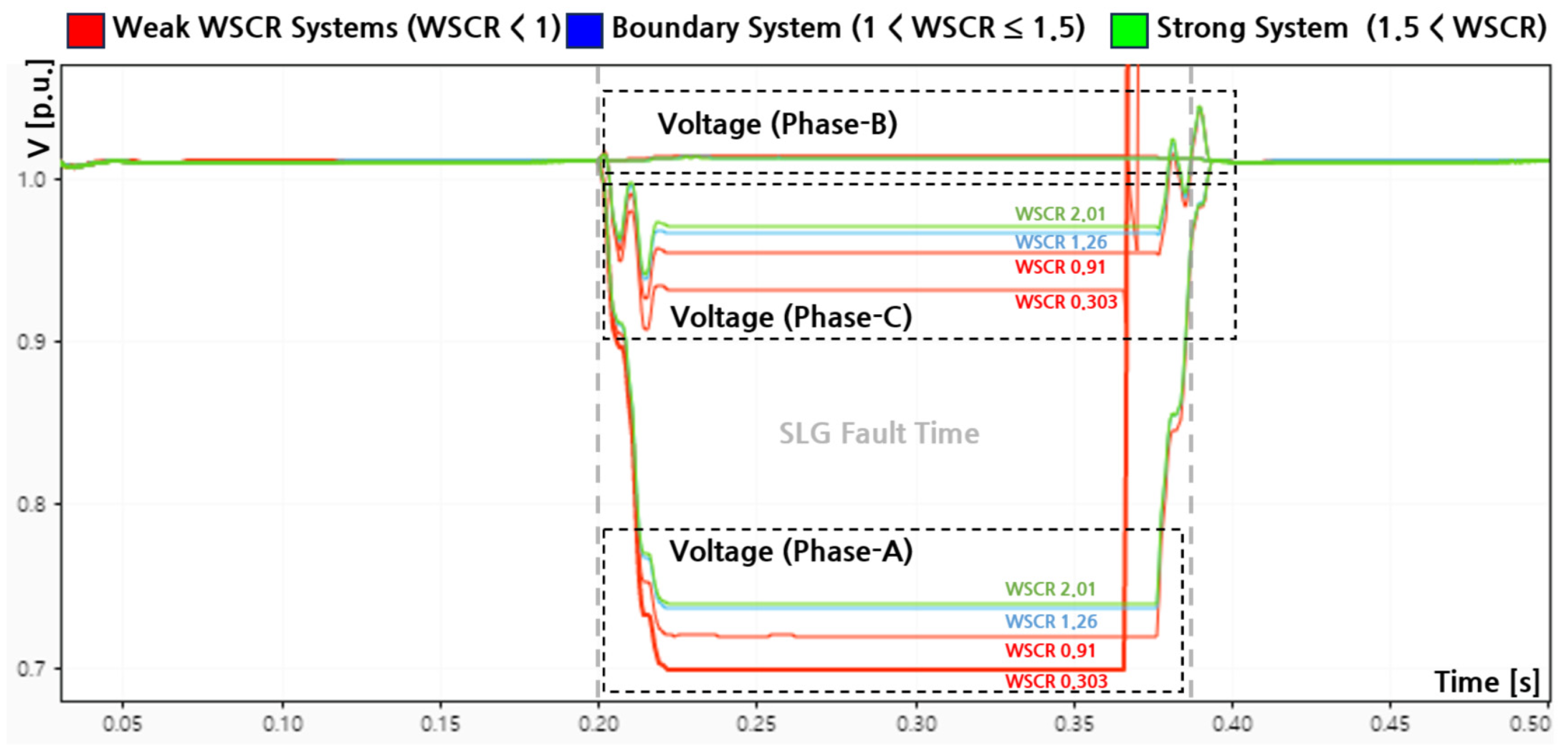

Figure 8 presents the measured PCC voltages of phases A, B, and C during an SLG fault under four different WSCR conditions.

The pre-fault voltage was 1.0101 [p.u.]. In the case of WSCR = 0.303, it failed to sustain stable operation and experienced loss of synchronization and control instability, leading to inverter tripping after the fault. This is attributed to the grid-following (GFL) inverter dynamics, where, in the absence of an explicit IGBT blocking command, the PLL-based synchronization and current control loop become unstable under such weak grid conditions, leading to loss of synchronization and subsequent disconnection and eventual trip. As shown, the faulted phase, Phase A, experienced significant voltage depressions, whereas Phases B and C showed relatively minor deviations. The numerical results are summarized in

Table 3.

Table 3 shows that the minimum voltage of Phase A improved from 0.699 [p.u.] at WSCR = 0.303 to 0.739 [p.u.] at WSCR = 2.01, corresponding to a sag depth reduction from –30.8 [%] to –26.9 [%]. Phase B remained close to the pre-fault level, with a slight voltage increase within the HVRT limit. Phase C showed a sag recovery from 0.932 [p.u.] (–7.8 [%]) to 0.971 [p.u.] (–3.9 [%]) as WSCR increased. These results confirm that higher WSCR values enhance ride through capability by mitigating sag depth on the faulted phase and improving voltage recovery on adjacent phases.

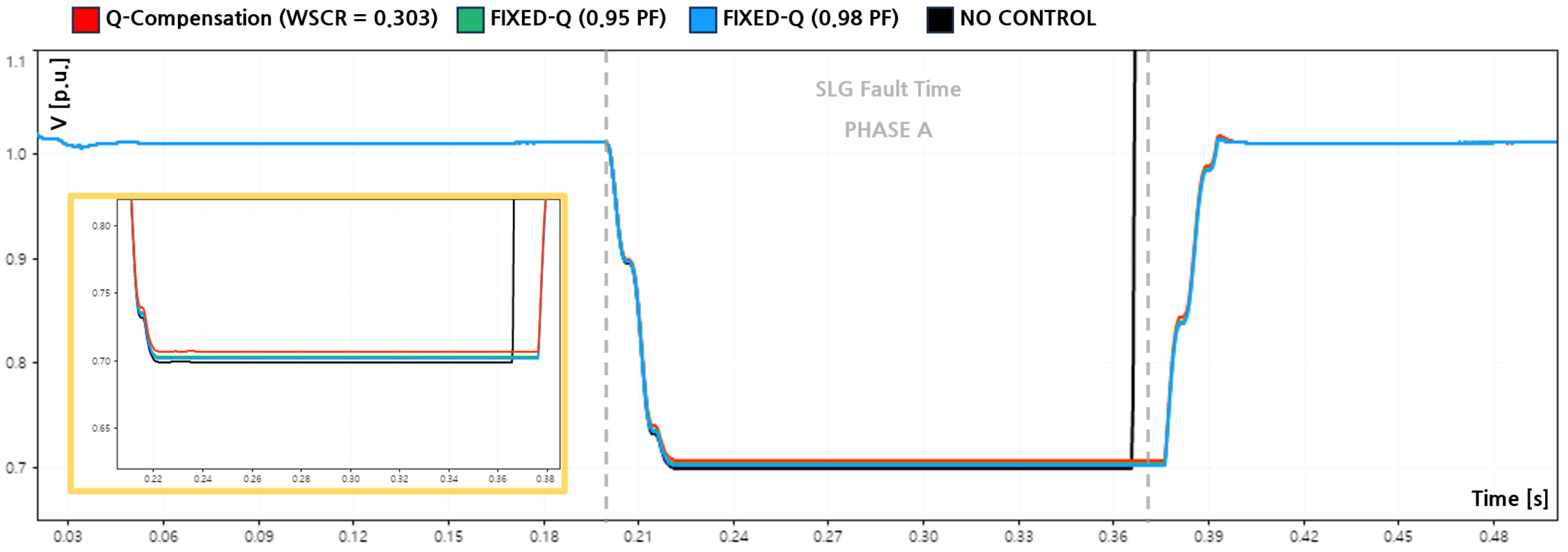

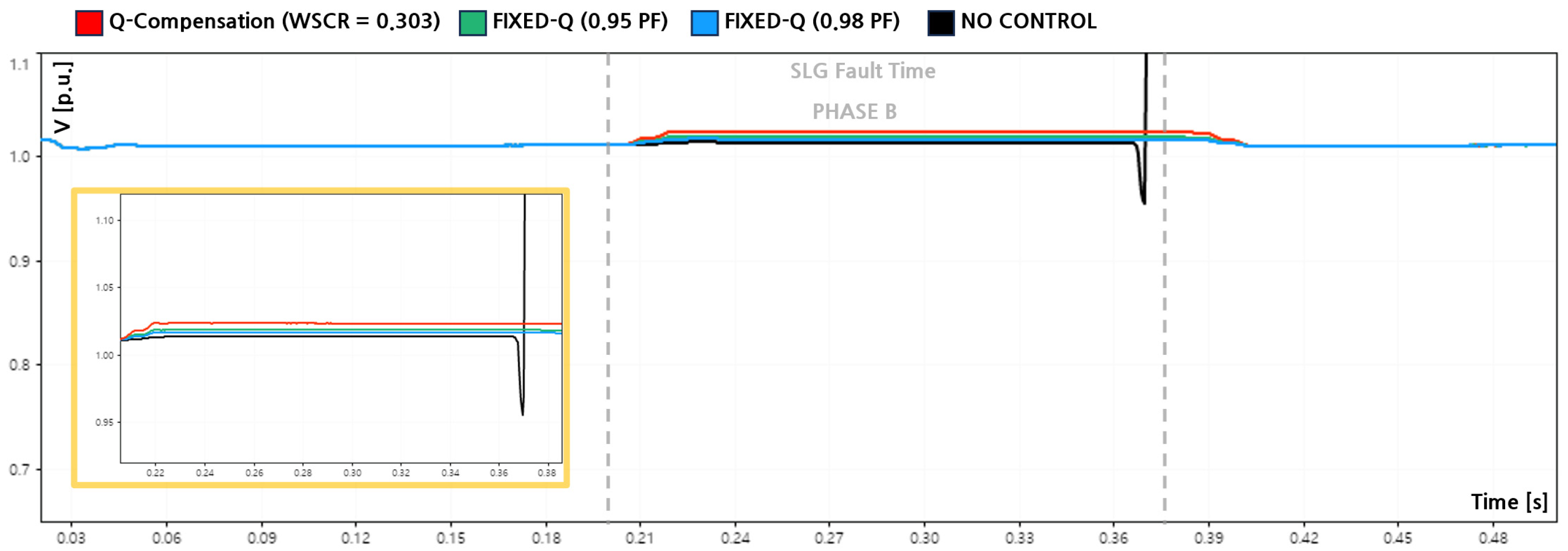

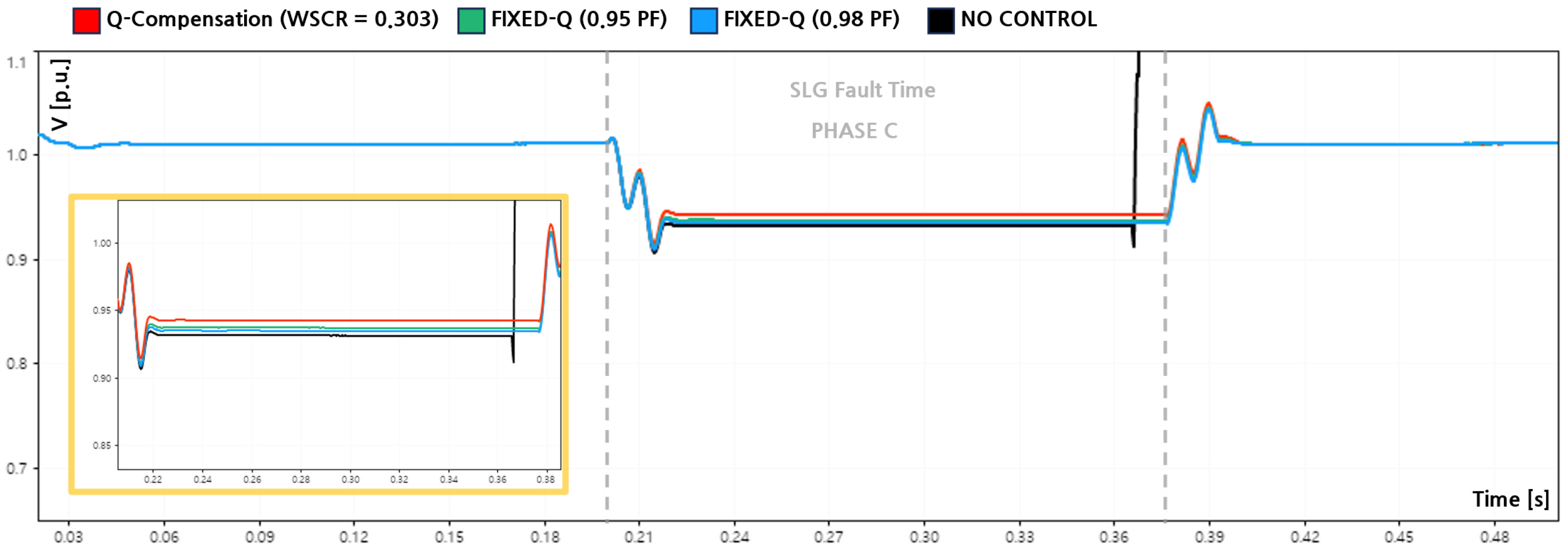

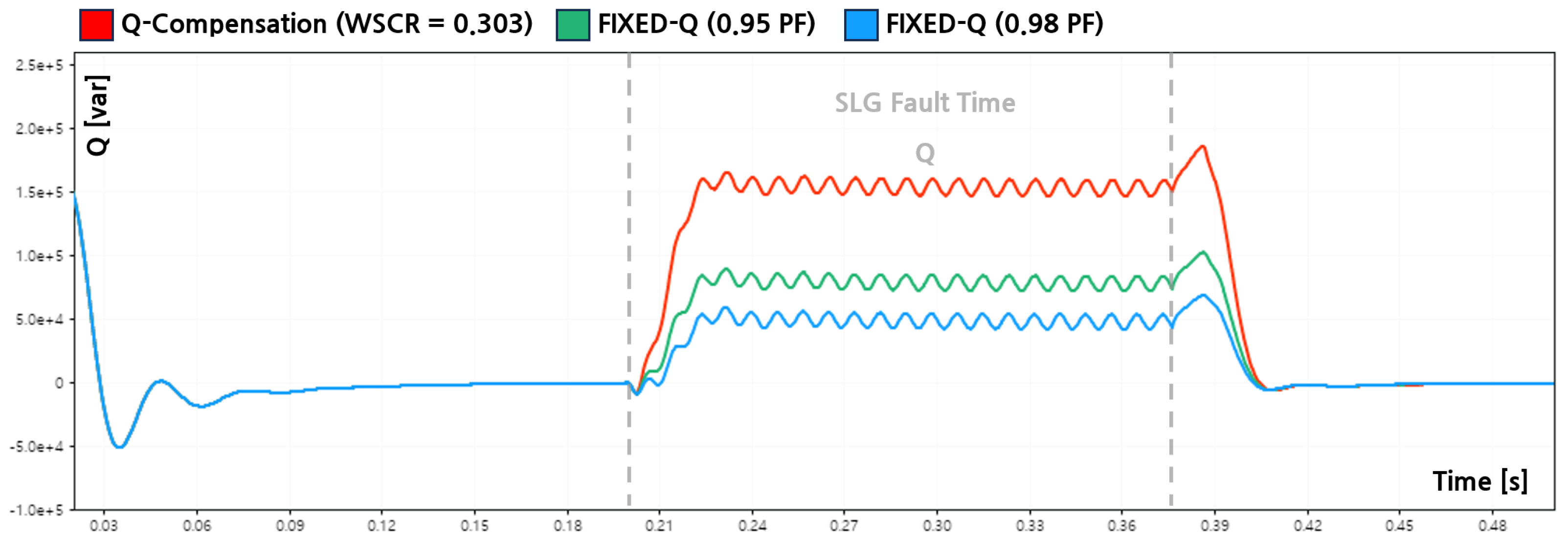

4.4. Effectiveness of Q-Compensation Under SLG Faults

This subsection analyzes the effectiveness of different reactive power control strategies during a single-line-to-ground (SLG) fault under an extremely weak grid condition characterized by a weighted short circuit ratio of 0.303. The comparison focuses on three cases: no reactive power control, the proposed fault-oriented Q-compensation strategy, and fixed-capacity reactive power control based on constant power factor limits (PF = 0.95 and PF = 0.98).

Figure 9,

Figure 10 and

Figure 11 present the measured PCC voltages of phases A, B, and C during the SLG fault, while

Figure 12 shows the corresponding reactive power output. The pre-fault PCC voltage was 1.0107 [p.u.], and the fault was applied at 0.20 [s] and cleared at 0.37 [s].

In the no-control case, the inverter did not provide any reactive support during the disturbance. Consequently, the faulted phase (Phase A) experienced a severe voltage drop to 0.699 [p.u.], corresponding to a sag depth of −30.8 [%]. Phase B showed a slight overvoltage of 1.014 [p.u.], while Phase C dropped to 0.932 [p.u.], resulting in a sag depth of −7.8 [%]. Under this condition, the grid-following inverter exhibited unstable post-fault behavior, which is consistent with the limitations of PLL-based synchronization in very weak grids.

When the proposed Q-compensation strategy was applied, the inverter dynamically injected reactive power according to the minimum phase voltage. As illustrated in

Figure 12, the reactive power output reached a maximum of 118 [kvar], with an average injection of approximately 105 [kvar] during the fault interval. This resulted in an improvement of the minimum Phase A voltage to 0.704 [p.u.], reducing the sag depth to −30.3 [%]. Phase B increased from 1.014 [p.u.] to 1.020 [p.u.], corresponding to a voltage rise of +0.59 [%], while Phase C recovered from 0.932 [p.u.] to 0.939 [p.u.], reducing the sag depth to −7.1 [%]. More importantly, the inverter maintained stable ride through operation without leading to loss of synchronization and inverter tripping after the fault or tripping under WSCR = 0.303.

For comparison, fixed-capacity reactive power control was implemented based on constant power factor limits commonly adopted in conservative grid operation practices. For the 237.6 [kVA] inverter, the fixed reactive power outputs corresponding to PF = 0.95 and PF = 0.98 resulted in an average reactive power injection of approximately 77.1 [kvar] during the fault. Under the PF = 0.95 condition, the minimum voltage of Phase A improved to 0.703 [p.u.], Phase B reached 1.019 [p.u.], and Phase C recovered to 0.937 [p.u.]. Under the PF = 0.98 condition, the corresponding voltages were 0.701 [p.u.], 1.017 [p.u.], and 0.935 [p.u.], respectively.

The quantitative performance indices are summarized in

Table 4, which compares the minimum PCC voltages and sag depths for each phase.

Table 5 further presents the voltage improvement ratios relative to the no-control case. These results demonstrate that while fixed-capacity reactive power control provides partial voltage support, the proposed Q-compensation strategy more effectively enhances voltage recovery and ensures stable fault ride through performance in very weak distribution networks.

Overall, the SLG fault results confirm that adaptive utilization of inverter reactive power capability is more effective than fixed-capacity approaches in supporting voltage stability under extremely weak grid conditions.

4.5. Effectiveness of Q-Compensation Under DLG Faults

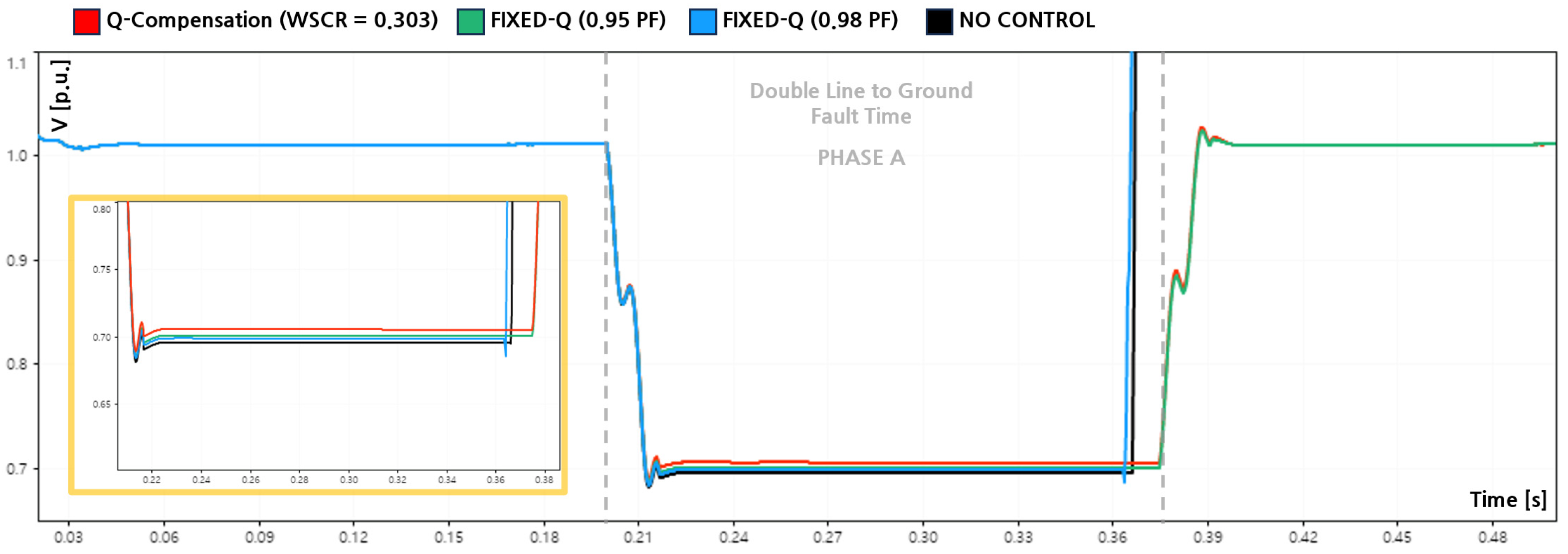

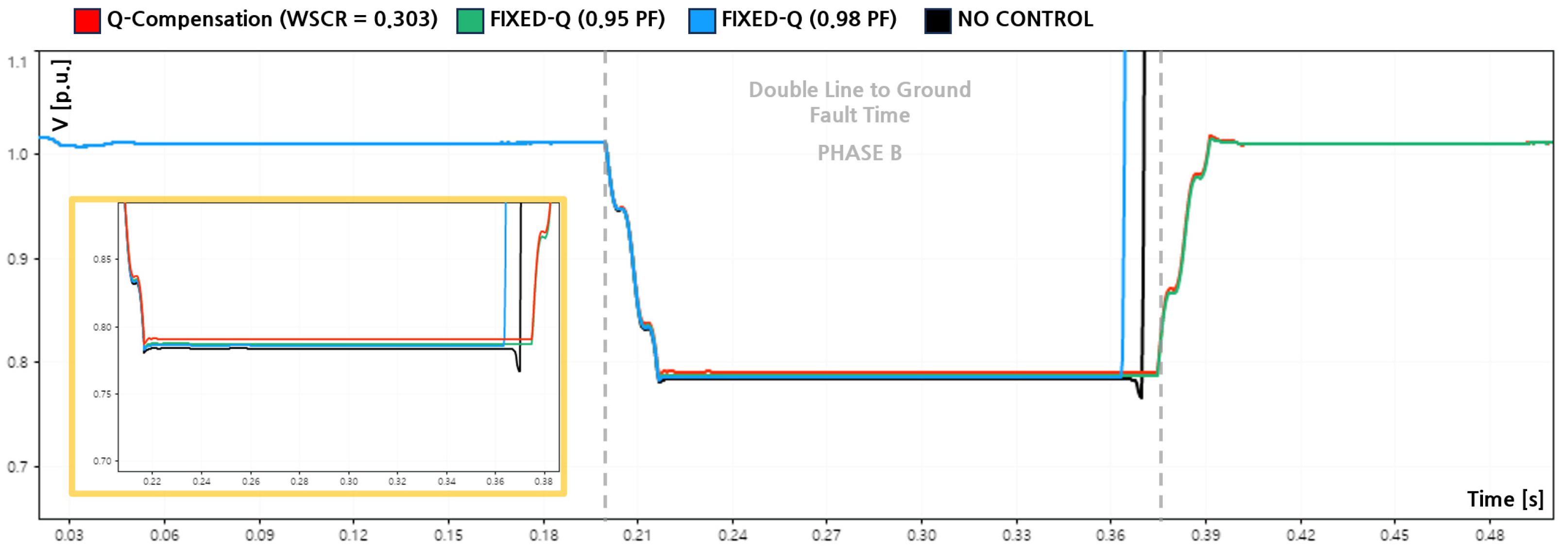

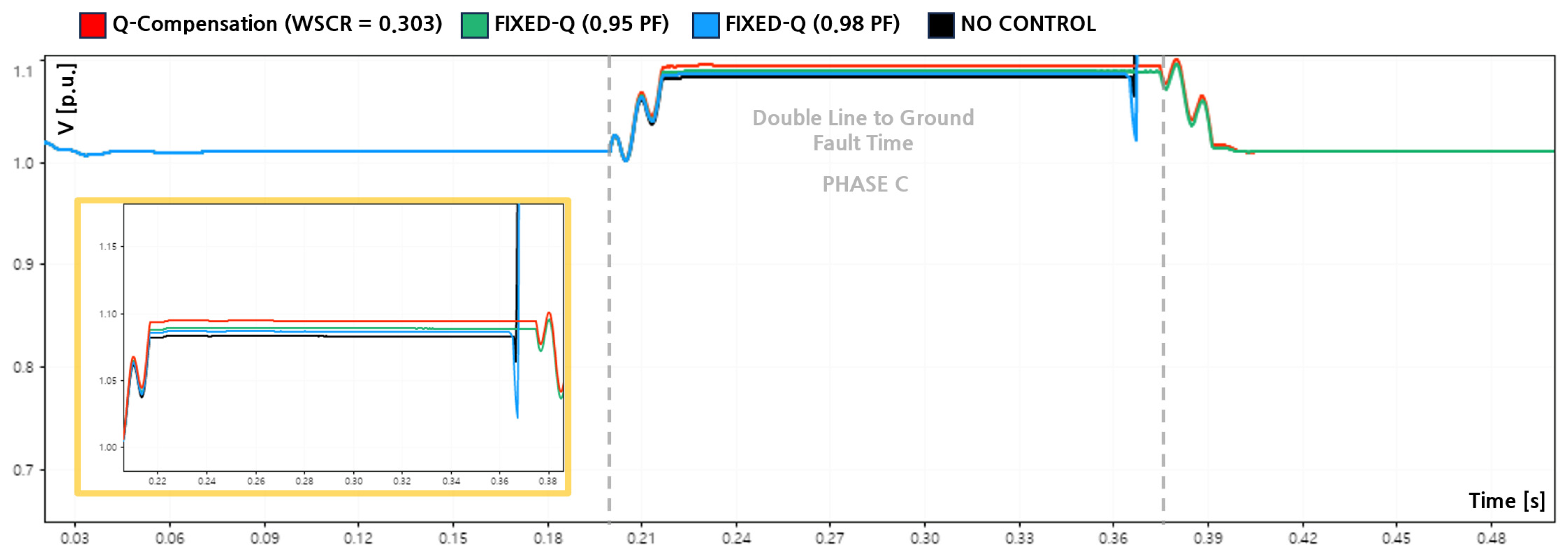

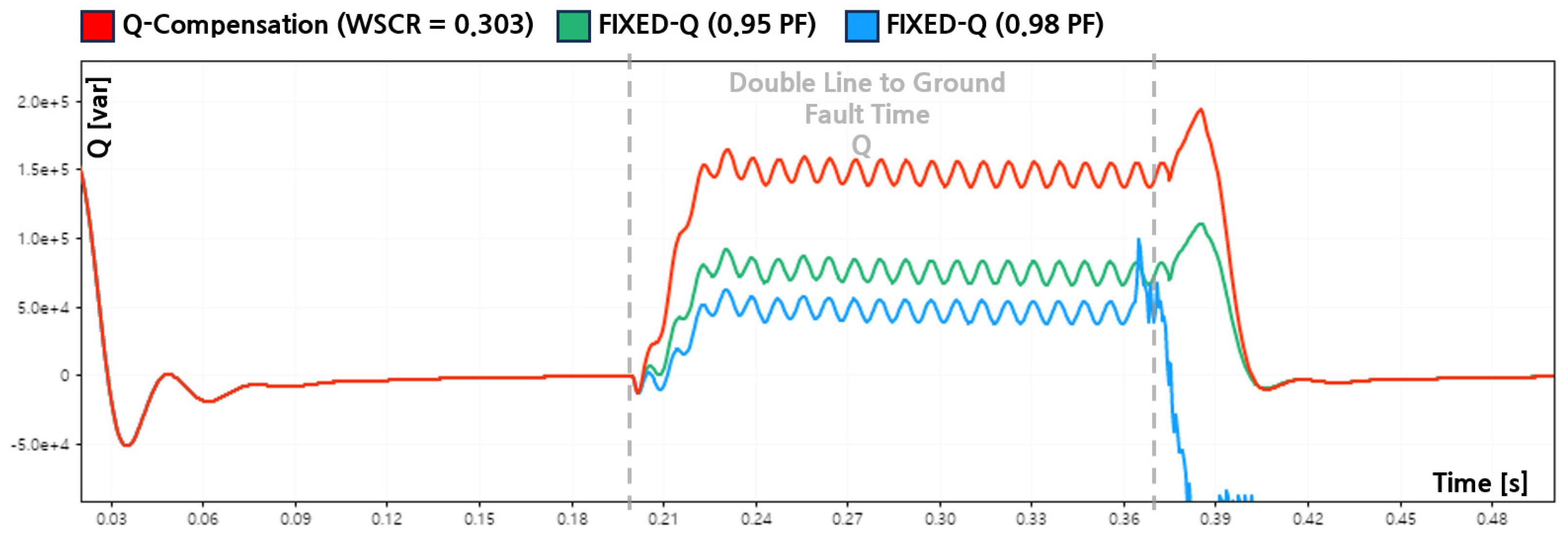

This subsection evaluates the effectiveness of reactive power control strategies during a double-line-to-ground (DLG) fault under an extremely weak grid condition with a weighted short circuit ratio of 0.303. The analysis compares four cases: no reactive power control, the proposed fault-oriented Q-Compensation strategy, and fixed-capacity reactive power control based on constant power factor limits (PF = 0.95 and PF = 0.98).

Figure 13,

Figure 14 and

Figure 15 illustrate the PCC voltages of Phases A, B, and C during the DLG fault, while

Figure 16 presents the corresponding reactive power outputs. The fault was applied at 0.20 [s] and cleared at 0.37 [s], identical to the SLG case, ensuring consistent fault severity across scenarios.

In the no-control case, the inverter did not inject any reactive power during the fault. Consequently, Phases A and B experienced significant voltage depressions, reaching minimum values of 0.695 [p.u.] and 0.783 [p.u.], corresponding to sag depths of −30.5 [%] and −21.7 [%], respectively, as summarized in

Table 6. Meanwhile, the unfaulted Phase C exhibited an overvoltage of 1.083 [p.u.]. Under this condition, the inverter failed to satisfy the LVRT requirements after fault clearance and subsequently disconnected from the grid, reflecting the limited fault tolerance of grid-following inverters operating without reactive power support in extremely weak networks.

When the proposed Q-Compensation strategy was applied, reactive power was dynamically injected based on the minimum phase voltage during the DLG fault. As shown in

Figure 16, the inverter supplied sufficient reactive power throughout the fault duration, resulting in improved voltage profiles across all phases. The minimum voltage of Phase A increased to 0.705 [p.u.], reducing the sag depth to −29.5 [%], while Phase B improved to 0.790 [p.u.] with a sag depth of −21.0 [%]. Phase C increased slightly to 1.094 [p.u.]. Importantly, the inverter maintained stable ride through operation without tripping, demonstrating that adaptive utilization of reactive power based on PCC voltage measurements effectively supports LVRT compliance under unbalanced fault conditions.

For comparison, fixed-capacity reactive power control was implemented using constant power factor limits. Under the PF = 0.95 condition, the inverter injected an average reactive power of approximately 78.1 [kvar] during the fault. This led to minimum voltages of 0.700 [p.u.] for Phase A and 0.787 [p.u.] for Phase B, while Phase C rose to 1.089 [p.u.]. Despite the reduced reactive power magnitude compared to the Q-Compensation case, the inverter successfully remained connected after fault clearance, indicating that moderate fixed-capacity reactive support can still satisfy LVRT requirements under DLG faults.

In contrast, under the PF = 0.98 condition, the average reactive power injection decreased to approximately 47.3 [kvar]. As a result, the post-fault voltage recovery was insufficient to maintain operation within the LVRT boundary. Although the minimum voltages of Phases A and B reached 0.698 [p.u.] and 0.786 [p.u.], respectively, the inverter disconnected after fault clearance, similar to the no-control case. This outcome highlights that overly conservative reactive power allocation can lead to LVRT failure even when some voltage improvement is observed during the fault.

The quantitative performance indices are summarized in

Table 6, and the voltage improvement ratios relative to the no-control case are presented in

Table 7. While fixed-capacity reactive power control yields intermediate voltage recovery between the no-control and Q-Compensation cases, only the proposed Q-Compensation and the PF = 0.95 fixed-Q strategy successfully maintained grid connection under the examined DLG fault. These results demonstrate that sufficient reactive power magnitude, rather than reactive power presence alone, is a decisive factor for LVRT compliance in extremely weak distribution networks.

Overall, the DLG fault results confirm that adaptive, fault-oriented reactive power compensation provides the most robust and reliable voltage support, whereas conservative fixed-capacity approaches may fail to ensure ride through when reactive power margins are insufficient.

4.6. Effectiveness of Q-Compensation Under Balanced Faults

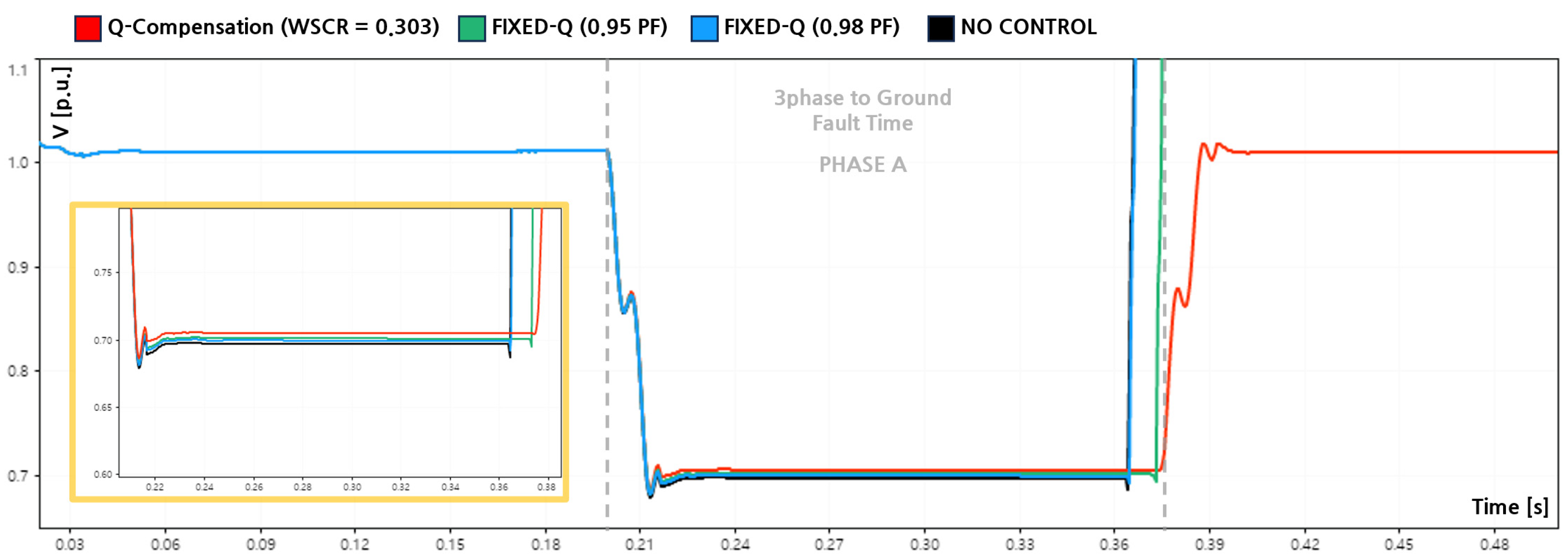

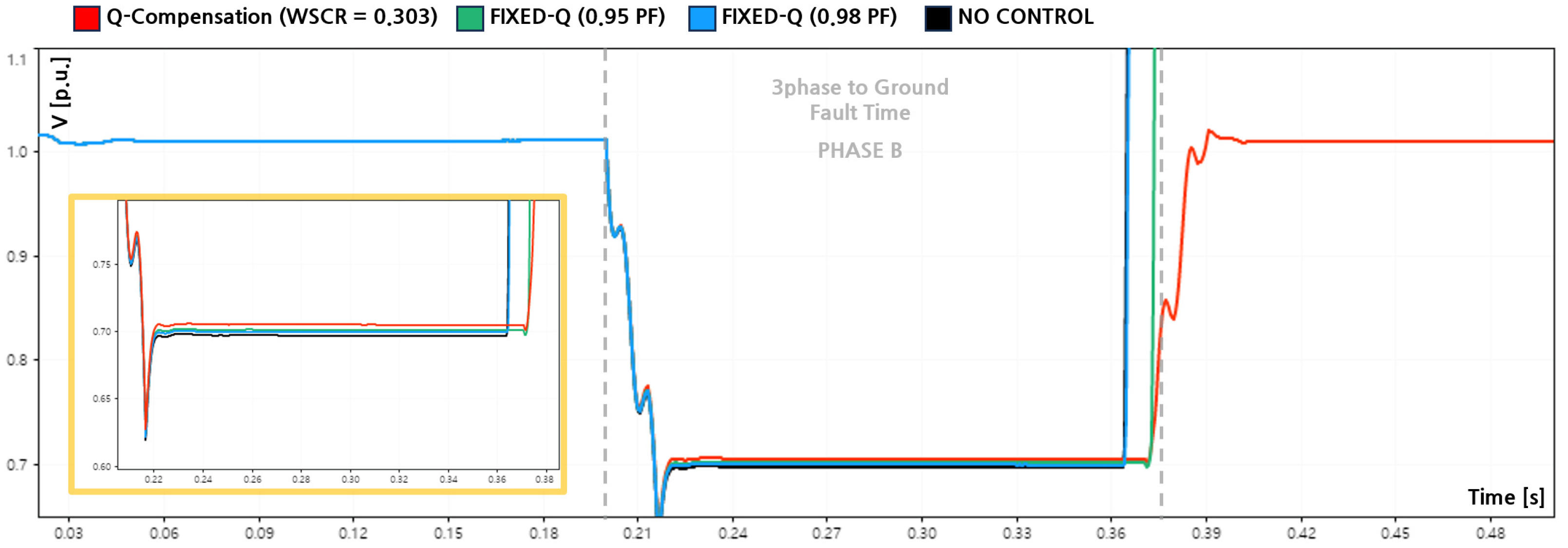

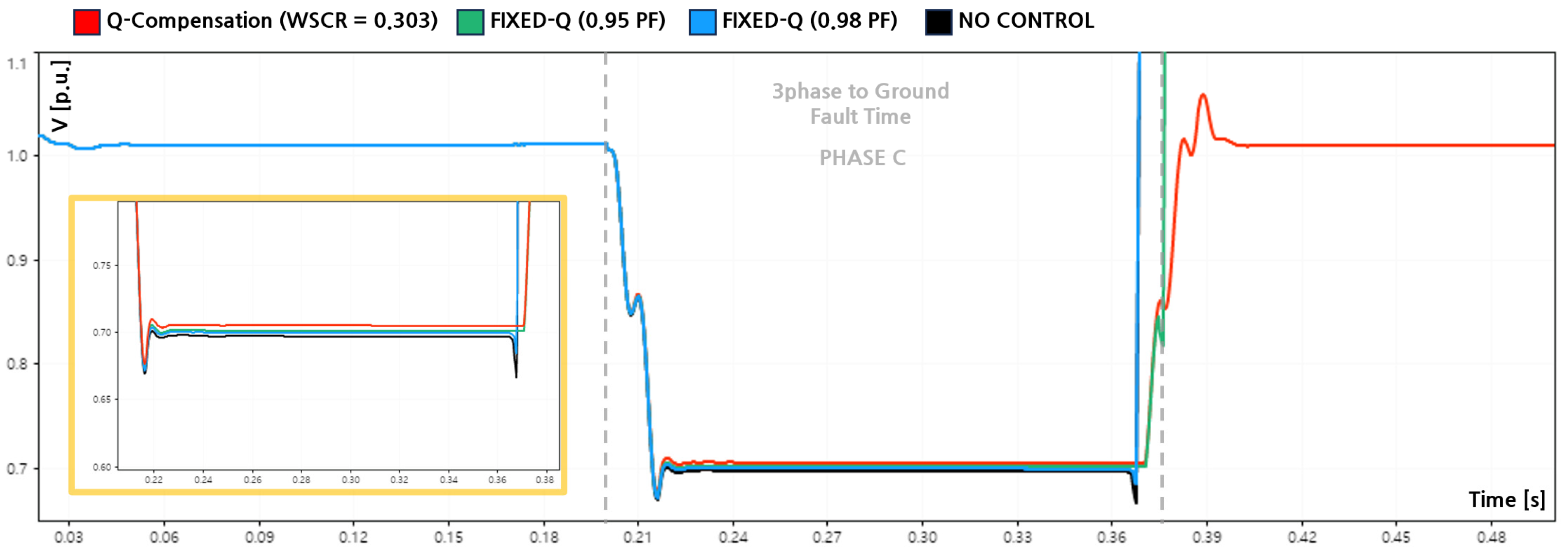

Figure 17,

Figure 18 and

Figure 19 illustrate the PCC voltages of phases A, B, and C during a three-phase-to-ground fault under an extremely weak grid condition (WSCR = 0.303), while

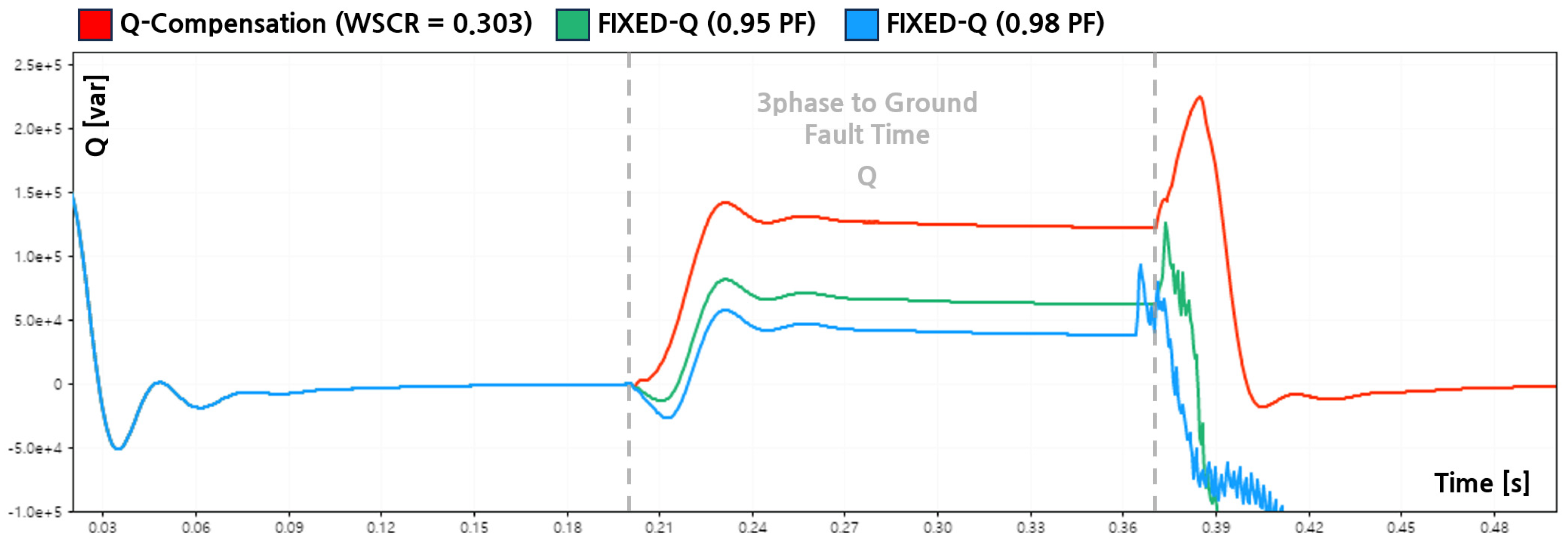

Figure 20 presents the corresponding reactive power outputs for each control strategy. In this fault scenario, all three phase voltages collapsed simultaneously and symmetrically. When the proposed Q-Compensation strategy was applied, the inverter remained connected throughout the fault duration and supplied reactive power in response to the voltage collapse.

As shown in

Figure 20, the inverter injected reactive power at a level comparable to the SLG and DLG fault cases, with an average output of approximately 124 [kvar] and a peak value of about 141 [kvar]. This reactive support increased the PCC voltages of all phases from 0.697 [p.u.] to 0.705 [p.u.], reducing the sag depth to −29.5 [%].

The corresponding voltage improvements are reported in

Table 8 and

Table 9. Although the absolute recovery margin was limited, the improvement was uniform across all phases, indicating stable and continuous ride through operation without leading to loss of synchronization and inverter tripping after the fault. For comparison, fixed-capacity reactive power control strategies based on constant power factor limits were also evaluated. In the PF 0.95 case, the post-fault voltages of Phases A, B, and C converged to approximately 0.700 [p.u.], while in the PF 0.98 case, they reached about 0.699 [p.u.].

The corresponding average reactive power outputs during the fault were approximately 64.1 [kvar] and 40.0 [kvar], respectively, as shown in

Figure 20. Despite using the same reactive power reference logic as in the SLG and DLG cases, the actual reactive current contribution during the three-phase fault was constrained by the severe and symmetric voltage collapse, resulting in limited voltage recovery.

Although the fault initiation time was identical for all control strategies, slight differences were observed in the tripping instants after fault clearance. The PF 0.95 case exhibited earlier disconnection compared to the PF 0.98 case. This behavior is attributed to the voltage-based LVRT protection mechanism rather than differences in control activation or fault severity. Under balanced three-phase faults, the inverter response is governed primarily by voltage magnitude thresholds, and the phase-specific reactive current (Iq) contributions cannot be distinctly reflected. In the balanced fault scenario, both PF 0.95 and PF 0.98 fixed-capacity control cases failed to maintain ride through operation, as the available reactive power support was insufficient to satisfy the LVRT requirements under severe voltage depression, leading to inverter disconnection.

Overall, these results demonstrate that fixed-capacity reactive power control provides limited voltage support and is highly sensitive to LVRT protection boundaries under severe balanced faults. In contrast, the proposed fault-oriented Q-Compensation strategy enables stable ride through operation and consistent voltage improvement even under extremely weak grid conditions.

5. Conclusions

This paper investigated the fault ride through (FRT) performance of inverter-based resources in extremely weak distribution networks and presented a fault-oriented reactive power compensation strategy based solely on point of common coupling (PCC) voltage measurements. Rather than relying on steady-state Volt–Var characteristics or predefined fixed-capacity reactive power injection, the proposed approach directly addresses fault-induced voltage depression and adaptively exploits inverter reactive power capability according to the most severely depressed phase voltage, without requiring fault-type identification or sequence-component analysis.

Simulation studies based on a detailed MATLAB/Simulink model constructed with actual Korean distribution feeder parameters demonstrate that the proposed Q-Compensation strategy improves voltage recovery and maintains stable inverter operation under SLG, DLG, and three-phase-to-ground faults, even at an extremely low WSCR of 0.303. While fixed-capacity reactive power control derived from conservative power factor limits provides partial voltage support, its effectiveness is highly sensitive to the selected reactive power margin and LVRT protection boundaries. In contrast, the proposed strategy consistently prevented inverter tripping by dynamically matching reactive power injection to fault severity, thereby achieving more reliable ride through behavior under weak grid conditions.

The significance of this study lies in demonstrating that grid-following inverters, which are currently dominant in the Korean distribution system, can actively contribute to voltage stability during grid disturbances when equipped with the appropriately designed fault-oriented reactive power control. By relying only on locally measurable PCC voltages, the proposed method remains compatible with existing smart inverter architectures and avoids additional computational burden or communication requirements, making it suitable for practical deployment in real distribution networks.

From the perspective of the Korean distribution system, the results provide quantitative evidence that adaptive reactive power control can serve as an effective alternative to overly conservative fixed-Q requirements that are often considered during interconnection assessment. This suggests a feasible pathway for enhancing system resilience while minimizing unnecessary inverter disconnections during temporary faults, particularly in feeders with low short-circuit capacity.

Future work will extend this study to investigate the combined impact of grid-following (GFL) and grid-forming (GFM) inverter operation in Korean distribution networks. In particular, the interaction mechanisms between GFL and GFM resources under fault conditions will be identified, and systematic parameter optimization will be explored to ensure coordinated voltage and frequency support in mixed-inverter environments.