Abstract

Workers with upper-limb disabilities face difficulties in performing manufacturing tasks requiring fine manipulation, stable handling, and multistep procedural understanding. To address these limitations, this paper presents an integrated collaborative workcell designed to support disability-inclusive manufacturing. The system comprises four core modules: a JSON-based collaboration database that structures manufacturing processes into robot–human cooperative units; a projection-based augmented reality (AR) interface that provides spatially aligned task guidance and virtual interaction elements; a multimodal interaction channel combining gesture tracking with speech and language-based communication; and a personalization mechanism that enables users to adjust robot behaviors—such as delivery poses and user-driven task role switching—which are then stored for future operations. The system is implemented using ROS-style modular nodes with an external WPF-based projection module and evaluated through scenario-based experiments involving workers with upper-limb impairments. The experimental scenarios illustrate that the proposed workcell is capable of supporting step transitions, part handover, contextual feedback, and user-preference adaptation within a unified system framework, suggesting its feasibility as an integrated foundation for disability-inclusive human–robot collaboration in manufacturing environments.

1. Introduction

Manufacturing tasks such as assembly, grasping, and component alignment present significant challenges for workers with disabilities due to physical and cognitive limitations. Upper-limb impairments restrict fine manipulation and stable object handling, whereas cognitive or developmental disabilities increase the difficulty of interpreting visual cues and managing multi-step procedures. These constraints often result in reduced productivity, higher error rates, and elevated safety risks, underscoring the need for assistive technologies that aim to support task accessibility and support the effective participation of disabled workers in industrial environments.

Recent advances in collaborative robotics, projection-based AR, object recognition and localization, and multimodal human–robot interaction (HRI) have accelerated the development of human-centered manufacturing systems. Although these technologies individually enhance physical assistance, spatial guidance, or interaction flexibility, most prior work addresses isolated capabilities—such as visual task feedback, gesture control, or robot-assisted manipulation—without offering an integrated workcell explicitly designed for disability-inclusive collaboration.

To address this gap, this study proposes a modular robotic workcell tailored to the needs of workers with disabilities. The system integrates four core components. First, a shared-control framework decomposes manufacturing processes into human–robot cooperative subtasks, formalized within a JSON-based collaboration database that defines ordered robot actions and ensures repeatable execution. Object recognition and spatial localization modules developed in this study provide the perception backbone necessary for stable task execution. Second, a projection-based AR interface delivers real-time spatial guidance—including procedural instructions, component and assembly locations, progress indicators, and user-specific task information—while enabling direct interaction through projection-mapped virtual buttons. Third, a multimodal communication system combining gesture tracking with speech-based interaction supports flexible and accessible command channels suitable for diverse disability profiles. Fourth, a personalization module allows users to adapt robot behaviors such as delivery poses or user-driven task role switching through natural language or gesture inputs, with user-specific modifications stored in the collaboration database for consistent application in subsequent operations.

In this study, shared autonomy is defined at the task and information level, where autonomy is not limited to robot motion generation but is distributed across the robotic workcell, including perception, AR-based information feedback, and interaction modules. This form of shared autonomy aims to compensate for functional limitations of workers with disabilities by allowing the workcell to assume cognitively or physically demanding subtasks, thereby enabling more equitable participation in industrial assembly processes.

This study aims to present an integrated collaborative workcell platform that supports disability-inclusive manufacturing by coherently combining task modeling, projection-based AR guidance, multimodal interaction, and user-driven personalization within a unified system architecture. The focus of this paper is not to advance individual algorithms, but to demonstrate how diverse enabling technologies can be systematically integrated and operated as a single, practical human–robot collaborative workcell. Accordingly, rather than focusing on the clinical evaluation of specific disability groups or on comparative performance benchmarking, the emphasis of this work is placed on demonstrating the system-level feasibility and practical applicability of integrating these heterogeneous element technologies into a single human–robot collaborative framework. For experimental validation, this study focuses on workers with upper-limb impairments, as such impairments directly affect fine manipulation, part stabilization, and human–robot handover operations that frequently arise in manufacturing environments. This selection serves as a representative use case to examine whether the proposed workcell can effectively support collaborative task execution under realistic constraints, rather than as an exhaustive evaluation across all possible disability types.

The contributions of this study are summarized as follows:

- I.

- A unified robotic workcell architecture for disability-inclusive manufacturing is introduced, integrating object recognition and localization, AR visualization, multimodal communication, and shared robot control into a cohesive operational framework. By synchronizing perception, projection, and control within a single execution loop, the proposed architecture supports stable and continuous human–robot collaboration during assembly tasks.

- II.

- A process-level human–robot cooperation model is formalized through a JSON-based collaboration database, providing structured, extensible, and reusable representations of task procedures across diverse disability profiles. This database-driven design facilitates workflow adaptation by providing structured and reusable task representations, supporting reuse across different users and disability profiles.

- III.

- A projection-based AR information feedback system is implemented to provide spatially aligned, real-time task guidance and interactive UI elements, designed to support task comprehension by providing spatially aligned guidance and interactive UI elements. The system maintains a stable visual update rate suitable for human-perceivable feedback, thereby supporting smooth and responsive visual feedback during collaborative operations.

- IV.

- A multimodal interaction framework is developed by combining gesture-based manipulation with speech-driven communication, enabling non-contact and redundant interaction channels. This design allows users to issue task-level commands without reliance on a single input modality, providing redundant interaction channels to accommodate diverse physical and cognitive capabilities

- V.

- A user-driven personalization mechanism is introduced that allows runtime modification of robot behaviors—such as delivery positions or user-driven task role switching—with updates persistently stored in the collaboration database. By persisting user-defined parameters in the collaboration database, the system avoids repeated manual reconfiguration across executions and provides a consistent basis for individualized assistance.

2. Related Works

2.1. Human–Robot Collaboration for Workers with Disabilities

Research on human–robot collaboration (HRC) for supporting workers with disabilities has expanded from rehabilitation and daily assistive contexts into industrial manufacturing environments. As collaborative robots become more prevalent in production settings, recent work has emphasized their potential to reduce the physical and cognitive workload of operators with disabilities.

Mandischer et al. proposed an adaptive HRC approach in which the level of robotic assistance dynamically changes according to the operator’s physical abilities and task demands, highlighting the importance of inclusive workplace design in industrial environments [1]. Similarly, Hüsing et al. investigated task allocation strategies and assistance-level determination for workers with physical impairments, demonstrating that personalized distribution of tasks between humans and robots is central to effective inclusive manufacturing [2]. Beyond task allocation, user acceptance and experience have also been examined. Drolshagen et al. assessed the attitudes and trust of workers with disabilities toward collaborative robots, underscoring the need for user-centered HRC design rather than purely automation-oriented approaches [3]. Complementary to this perspective, Kremer et al. presented a case study in which a collaborative workstation was designed for disabled workers, showing how ergonomic improvements and shared task execution can enhance work quality in manufacturing settings [4]. Furthermore, Cais et al. proposed a line-balancing optimization model for assembly scenarios involving workers with disabilities, demonstrating how collaborative robots can improve productivity while accommodating individual physical constraints [5].

2.2. Process-Level Workflow Modeling for Human–Robot Cooperation

While Section 2.1 focuses on HRC approaches tailored for workers with disabilities, effective collaboration in industrial settings also requires structured process-level representations. Accordingly, recent research has emphasized workflow modeling as a foundation for scalable and adaptable HRC. Process-level workflow modeling has gained increasing attention as a foundation for flexible and scalable HRC in manufacturing environments. Lucci et al. introduced a predicate-logic–based workflow modeling framework capable of representing assembly processes with diverse component geometries, tools, and task sequences, demonstrating its suitability for structuring complex collaborative procedures in industrial settings [6]. Likewise, Lee et al. implemented a model-based HRC system for small-batch assembly and employed a “virtual fence” mechanism that dynamically adapts the control logic to changes in the process plan, thereby enabling flexible and safe cooperative operation [7].

Broader reviews of HRC in smart manufacturing emphasize the need for integrated systems that combine workflow modeling, digital twin technologies, flexible assembly planning, and advanced human–robot interaction methods [8]. Building on this perspective, Lee et al. proposed a framework in which process-model–based collaboration is coupled with AR feedback, illustrating how workflow logic, visual guidance, and collaborative control can be unified within a single system architecture [9]. More recent studies highlight the importance of human modeling in HRC and digital twin environments, noting that variability in human behavior, physical capabilities, and cognitive states must be incorporated into process-level collaboration models to support adaptive interaction [10].

While existing workflow- and process-model-based HRC studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of combining structured task representations with AR feedback and collaborative control, most approaches primarily treat AR as a visualization layer for presenting predefined workflow states to the human operator. In contrast, the present work adopts a database-driven integration architecture in which a shared collaboration database serves as a unified backbone for task representation, robot behavior, multimodal interaction, and user-specific adaptation. This design enables runtime personalization and flexible reuse of task procedures across different users and disability profiles, thereby positioning the proposed system as a system-level integration framework rather than an incremental extension of AR-based process visualization.

2.3. Augmented Reality–Based Information Feedback in Human–Robot Collaboration

Effective HRC in manufacturing requires mechanisms that deliver clear task-relevant information to the operator and support intuitive interaction with the robot. Recent research has highlighted AR as a promising modality for enhancing task comprehension, spatial guidance, and shared situational awareness in collaborative environments. Costa et al. demonstrated that AR can improve human–robot interaction across assembly, inspection, and maintenance tasks by providing context-aware visual cues that reduce cognitive load [11]. Similarly, Hietanen et al. reported that a projection-based AR interface significantly reduced task duration and robot idle time in industrial assembly scenarios, underscoring AR’s potential to streamline collaborative workflows [12].

AR has also been shown to improve transparency and predictability in HRC by visualizing task steps, workspace constraints, and robot states. Loy et al. found that AR enhanced spatial awareness and interaction flexibility in large-scale assembly tasks, particularly where task structures were highly variable [13]. Lunding et al. reported that AR-based visualization increased workspace awareness and supported more synchronized collaboration in parallelized assembly operations [14]. More recent studies that combine AR with eye-gaze interaction have demonstrated the potential to facilitate real-time intention sharing between humans and robots, thereby improving interaction fluency and collaboration efficiency [15].

2.4. Multimodal Interaction for Human–Robot Collaboration

Achieving intuitive and flexible HRC in manufacturing requires interaction modalities beyond traditional interfaces, such as buttons or pendant controllers. Accordingly, recent studies have focused on multimodal interaction frameworks that combine gestures, speech, and other human cues to support more natural communication between operators and robots. Salinas-Martínez et al. demonstrated a dual-modal platform integrating gesture and speech commands to control multiple devices within a PCB manufacturing cell, highlighting its practical scalability for industrial use [16]. Chen et al. further showed that real-time gesture–speech fusion improves interaction efficiency compared to single-modal control, achieving more responsive and robust robot operation in dynamic tasks [17]. Review work by Wang et al. has emphasized that the integration of visual, auditory, tactile, and physiological modalities is becoming a central requirement for human-centric smart manufacturing, as multimodal fusion can reduce cognitive load and improve interaction flexibility [18].

In addition, Thomason et al. proposed a mechanism for recognizing unfamiliar user gestures, demonstrating the potential for gesture-based HRI systems to accommodate inter-user variability and non-standard movement patterns [19]. More recently, Zhao et al. introduced a perception-driven decision-making framework that integrates multimodal sensor inputs to enable adaptive robot behaviors in changing environments, reinforcing the role of multimodal fusion in robust HRC [20].

2.5. Personalized and Adaptive Human–Robot Collaboration

As human-centric manufacturing becomes increasingly important, personalized and adaptive HRC has emerged as a key research direction for improving collaborative task efficiency and safety. Conventional fixed-pattern collaboration workflows, however, often fail to account for differences in user capability, preference, or situational context. These limitations are especially pronounced for workers with disabilities.

To overcome these constraints, recent studies have explored adaptive collaboration strategies that incorporate user-state modeling, history-based behavioral adjustment, and real-time feedback mechanisms. Freire et al. proposed a socially adaptive cognitive architecture for industrial disassembly tasks, enabling robots to adjust collaboration strategies dynamically in response to user behavior, errors, and gestures [21]. Fant-Male et al. further highlighted personalization and adaptive control as essential components of next-generation HRC systems within the Industry 5.0 paradigm [22]. Research on long-term HRC also demonstrates that tailoring robot assistance to user preferences and interaction patterns can improve collaborative performance and user satisfaction [23]. In manufacturing contexts, Jahanmahin et al. emphasized the importance of human behavior modeling for estimating user state and regulating robot support intensity and safety boundaries [24].

Overall, the literature reviewed across Section 2.1, Section 2.2, Section 2.3, Section 2.4 and Section 2.5 demonstrates substantial progress in disability-inclusive HRC, workflow-driven cooperation modeling, AR-based guidance, multimodal interaction, and personalized collaboration. However, these research efforts remain largely fragmented. Most existing studies focus on isolated functionalities or narrow task scenarios rather than providing a comprehensive framework that supports end-to-end manufacturing processes. Furthermore, few systems integrate process-level collaboration logic, real-time AR feedback, multimodal interaction channels, and user-driven personalization within a unified workcell. The variability associated with different types of disabilities—such as differences in physical capability, perceptual constraints, or cognitive workload—also remains insufficiently addressed in current collaborative systems. These limitations underscore the need for an integrated HRC architecture that combines structured workflow modeling, accessible visual feedback, multimodal communication, and adaptive personalization. The modular robotic workcell proposed in this study is designed to provide such an integrated HRC solution for workers with disabilities.

3. Design of the Robotic Workcell for Workers with Disabilities

3.1. Overall System Overview

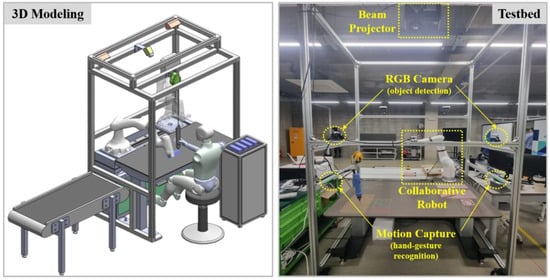

The robotic workcell developed in this study is a modular and integrated platform designed to support manufacturing tasks performed by workers with disabilities. As shown in Figure 1, the system combines a collaborative robot, a projection-based AR interface, multimodal interaction modules, object-recognition sensors, and user input devices within a unified workspace optimized for seated operation. The spatial arrangement is configured to allow seamless collaboration between the worker and the robot while ensuring accessibility and ergonomic operation.

Figure 1.

Overall configuration of the proposed robotic workcell.

A beam projector and an RGB camera are mounted on the upper frame of the workcell. The RGB camera provides environmental perception for component detection and workspace monitoring, while the projector generates real-time AR overlays—including task instructions, component locations, assembly targets, and reactive virtual buttons—directly on the work surface. A motion-capture sensor is installed at the front of the workspace to track hand articulation and fingertip movement, enabling gesture-based selection of projected UI elements and hands-free interaction with the workcell. The collaborative robot is positioned on the side opposite the user’s seating location, facing the worker across the task surface. This layout ensures a clear interaction field for the user while allowing the robot to perform cooperative actions such as component delivery, holding, positioning, and sequential task assistance. Robot actions follow a structured workflow defined in the collaboration database, ensuring consistent execution of process-level cooperative behaviors.

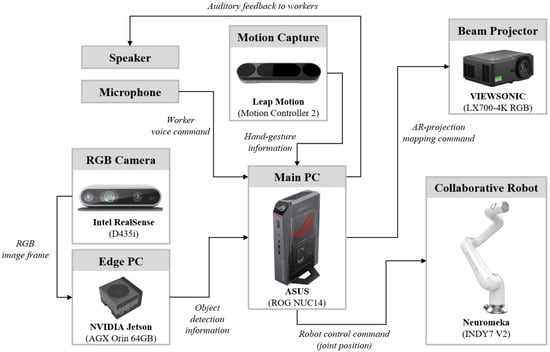

Figure 2 illustrates the system-level data flow and hardware system architecture. Image and motion-capture data are processed on an edge PC and the main workstation to perform object recognition, gesture analysis, and user-state interpretation. A microphone and speaker provide the input/output channels for speech-based interaction, which is handled through a pipeline comprising speech-to-text (STT), a large-language-model reasoning module, and text-to-speech (TTS) for system responses. The collaborative robot controller communicates with the main PC in real time to execute task-level motions, while the projector renders AR guidance and interactive UI elements generated by the central processing unit.

Figure 2.

System-level data flow and hardware/software architecture of the workcell.

Through this integrated configuration, the workcell supports visual, speech-based, and gesture-based multimodal interaction; database-driven collaborative robot control; and adaptive AR feedback within a single architectural framework. The resulting system enhances accessibility for workers with diverse disabilities and enables personalized, user-driven adjustments to the manufacturing workflow.

3.2. Collaborative Task Modeling and Robot Execution Framework

3.2.1. Task Modeling and Collaboration Database Construction

To construct a structured representation of human–robot cooperation tailored to diverse disability profiles, the proposed workcell decomposes each manufacturing procedure into a set of elementary task units. These task units serve as the fundamental building blocks from which cooperative workflows are generated. As shown in Table 1, each task unit is defined using a formal representation model consisting of three components: (1) an action type, (2) an associated object set (primary object and secondary object), and (3) a semantic specification describing the intended operation.

Table 1.

Definition of the task units within the collaboration database.

Using this representation, work instructions from the partner manufacturing company were analyzed and formalized into human task units (H1~Hn) and robot task units (R1~Rm). Task allocation varies according to the operator’s disability characteristics; for example, workers with upper-limb impairments may not be capable of stabilizing a component while performing a secondary manipulation, requiring the robot to assume corresponding stabilization or positioning tasks. The resulting task units are arranged into a cooperative workflow—such as H1 → H2 → R1 → R2 → H3 →…—that specifies the ordered execution of human actions, robot actions, and system-generated assistance.

These formalized task units and workflow sequences are encoded in a JSON-based collaboration database, which contains:

- User profile parameters: disability type, available interaction modalities (speech/gesture), tutorial mode, table-height configuration, and personalized robot parameters.

- Human task list: structured entries specifying action types, object sets, and associated AR feedback requirements.

- Robot task list: parameterized action entries including object information and motion descriptors.

- AR feedback definitions: projection-based visual cues such as component highlighting, positional guidance, and step-transition prompts.

- Integrated workflow sequence: a unified ordered list combining AR prompts, human tasks, and robot tasks.

The collaboration database is stored in a supervisory server and retrieved upon user login, allowing the workcell to execute a workflow tailored to the specific operator. Any adjustments made during task execution—such as modifying robot handover positions or updating preferred assembly locations through voice or gesture commands—are written back to the user-specific database, enabling persistent personalization across sessions. This structured representation framework provides a consistent and extensible foundation for supporting user-driven task role switching, multimodal interaction, AR-guided instruction, and adaptive robotic assistance within the proposed workcell.

3.2.2. Perception-Based Collaborative Robot Control Framework

Reliable perception of workpieces is essential for executing robot-assisted tasks within the collaborative workcell. The proposed system adopts a YOLOv12-based real-time detector trained on a custom dataset comprising approximately 10,000 images collected under realistic manufacturing conditions. The dataset reflects variations in viewpoint, illumination, background, and partial occlusion caused by either the operator’s hands or the robot arm. To enhance robustness under such variability, the dataset was expanded to roughly 100,000 samples through geometric transformations, photometric adjustments, noise injection, and synthetic occlusion augmentation.

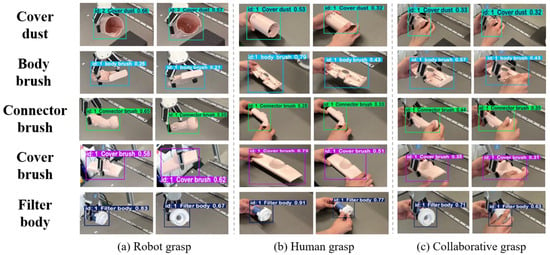

To further improve detection stability in the presence of intermittent occlusions, the pipeline incorporates TCAT (Time-Consistent Adaptive Thresholding), which adjusts confidence thresholds across consecutive frames based on temporal consistency. TCAT effectively suppresses unstable detections and mitigates jitter, yielding temporally coherent outputs even when objects are partially occluded. Representative qualitative results obtained using the YOLOv12 + TCAT pipeline under diverse operational conditions—including hand occlusion, robot-grasp motion, and pose variation—are presented in Figure 3, illustrating the robustness of the adopted perception module across the five target object categories.

Figure 3.

Detection results using the YOLOv12 + TCAT model.

As a quantitative reference, Table 2 summarizes the object detection performance of the YOLOv12 + TCAT pipeline on the target object categories within the collaborative workcell environment. The results indicate consistently high detection accuracy across the considered components, demonstrating that the perception module achieves stable object localization performance within the target collaborative workcell environment.

Table 2.

Detection performance of the YOLOv12 + TCAT perception module.

The evaluation in Table 2 was conducted under a typical industrial collaborative workcell setting with predefined object categories and task configurations. The perception module is intended to support stable task execution within this controlled manufacturing context rather than to address all possible extreme environmental conditions. When detection confidence falls below a task-critical threshold, the system conservatively pauses task progression and requests user confirmation, ensuring safe and predictable robot behavior.

The resulting object positions and orientations are directly mapped to the task units defined in the collaboration database, providing real-time parameters for grasp synthesis, motion planning, and placement adjustment. As the operator manipulates objects or as the workspace geometry changes, updated detection outputs allow the robot to maintain consistent task execution. Voice and gesture inputs may trigger re-detection or pose refinement as required by the collaborative workflow. Overall, the integration of YOLOv12 with TCAT provides a stable perception backbone for perception-driven robot behavior within the proposed modular workcell.

The object detection outputs serve as the primary input to the robot control framework. The detected object coordinates are transformed into the robot reference frame and associated with the task units defined in the collaboration database. Based on these coordinates, the robot generates a motion plan to approach the vicinity of the target component. For the grasping phase, a reinforcement learning–based grasping policy is employed, which utilizes depth information acquired from a sensor mounted at the gripper end-effector. The policy estimates the final grasp pose using local depth features and the relative end-effector configuration, enabling reliable grasp execution despite placement deviations or partial occlusions. The grasping policy is trained in a physics-based simulation environment using PyBullet(v3.2.7), where the CAD (STL) models of the target industrial components are loaded to reflect the actual manufacturing objects. A depth camera model is employed to generate local depth observations at the gripper end-effector, which are used as input to the reinforcement learning policy. This simulation-based training setup enables reliable grasp execution for a predefined set of workpieces, rather than aiming at general-purpose grasping across arbitrary object geometries.

Subsequent manipulation actions—such as transport, placement, and alignment—are executed according to the sequence specified in the collaboration database. When the operator alters the object position or when the workspace configuration changes, updated perception inputs are immediately integrated into the controller, allowing the robot to adjust its motion in real time. It provides the essential capabilities required for the robot to carry out collaborative tasks using object recognition as its operational basis.

In the present implementation, the collaboration database primarily represents task procedures as structured sequences of task units, which is sufficient for validating system-level integration and collaborative task execution within a single workcell. However, this representation does not explicitly capture advanced manufacturing process constructs such as conditional branching, exception handling, or parallel task execution, which may arise in more complex or large-scale production scenarios. This limitation reflects an intentional design choice to prioritize clarity, robustness, and synchronized human–robot collaboration in the target application scope of this study. The proposed JSON-based database is designed to be extensible, and future extensions may incorporate condition descriptors, execution states, or synchronization constraints to support non-linear workflows and adaptive process control. A systematic investigation of such advanced process modeling and execution strategies is considered an important direction for future work.

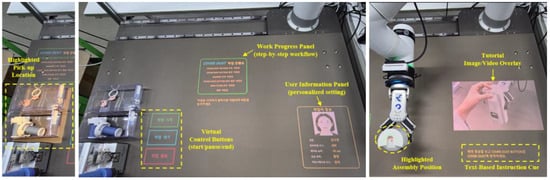

3.3. Projection-Based AR Information-Feedback System

The projection-based information feedback system developed in this study is designed to provide workers with intuitive visual cues directly within their task space, thereby enhancing task comprehension and supporting step-by-step execution of manufacturing procedures. The system is implemented as a WPF-based AR interface, in which all projected UI elements—including highlight effects, task-sequence panels, virtual control buttons, tutorial images and videos, and user-specific information—are developed as independent visualization components. Each component is dynamically updated in real time, and the projected imagery is spatially aligned with the physical work surface through a calibration and projection-mapping process, ensuring accurate geometric correspondence with the workspace. To illustrate the functionality of the AR interface, Figure 4 presents representative examples of the visualization components rendered on the work surface. These include (i) a highlight effect projected onto the target pickup location to guide the worker toward the correct part, (ii) a task-progress panel in which the currently active step is emphasized while completed steps are visually deactivated, (iii) virtual control buttons enabling the worker to initiate, pause, or terminate a task sequence, and (iv) context-specific instructional media such as tutorial images, videos, and textual guidance projected near the relevant assembly region. Together, these projected elements provide immediate, spatially contextualized feedback that supports both procedural understanding and workspace navigation.

Figure 4.

Examples of projection-based AR visual feedback.

Because the AR interface must reflect diverse real-time information—such as robot motion state, process transitions, object detection outcomes, user inputs (gesture and speech), and updates within the collaboration database—it requires synchronized communication with the Linux-based main controller that governs the workcell. To support this cross-platform integration, the system defines lightweight component-level protocols for functions including virtual button generation, highlight rendering, progress-status updates, and tutorial playback. The main controller transmits the corresponding commands via TCP messages, which are received and executed by the Windows-based AR interface. Upon message reception, the interface immediately updates the relevant UI components, allowing changes in task state, environmental configuration, or user-specific preferences to be reflected with negligible latency.

This architecture allows the AR interface to remain a modular and platform-independent visualization layer while maintaining close coupling with the perception and control modules that operate on the Linux host. Furthermore, the component-based design facilitates extensibility—enabling new UI elements, personalized display settings, or updated instructional content to be incorporated with minimal structural modification. Overall, the projection-based feedback system is designed to enhance visual accessibility for workers with different disability profiles and to support task understanding and operational accuracy within the collaborative robotic workcell.

To assess the operational responsiveness of the projection-based AR feedback within the proposed workcell, the update rate of the AR visualization module was experimentally evaluated. The AR system was executed under continuous task guidance conditions, and the update frequency was measured over repeated execution cycles. The results show that the AR module maintains an average update rate of approximately 31 Hz, which is sufficient to provide smooth and human-perceivable visual feedback. This indicates that the proposed AR feedback mechanism can support stable and responsive information presentation during human–robot collaborative tasks without introducing perceptible visual delay.

3.4. Multimodal Communication System

The multimodal communication system developed in this study is designed to accommodate diverse interaction needs arising from different disability types and individual user preferences. By integrating a gesture-based direct manipulation interface with a voice- and language-driven command interface, the system enables users to convey task instructions and regulate the workflow through their preferred modality. This multimodal structure minimizes interaction barriers imposed by physical or cognitive constraints and enhances both the flexibility and accessibility of the collaborative workcell.

3.4.1. Hand Gesture-Based Interaction

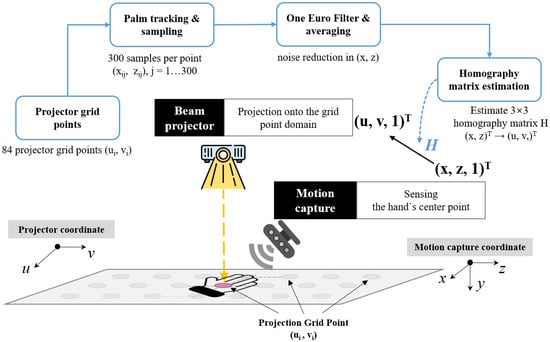

The gesture-based interaction module enables contactless command input by mapping the user’s hand motions onto the projected user interface. Prior to runtime operation, a calibration procedure is performed to align the motion-capture coordinate system with the projector’s pixel coordinate frame. As illustrated in Figure 5, this procedure begins by sampling the palm-center position over 84 predefined grid points on the work surface, with approximately 300 measurements collected per point. The sampled positions are denoised using the One Euro Filter, and the averaged values are used as representative coordinates. These coordinates are paired with the corresponding projector-domain pixel locations to estimate a homography matrix via a least-squares formulation, thereby compensating for scale discrepancies, planar distortions, and perspective effects between the two coordinate systems.

Figure 5.

Homography-based alignment between hand-tracking space and projection space.

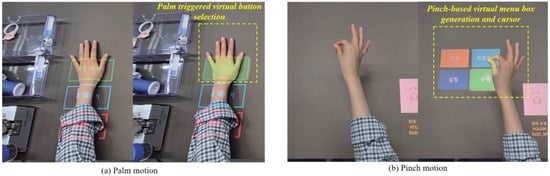

Once calibration is complete, the system interprets gesture inputs in real time. For each incoming frame, the measured palm-center position is transformed into projector coordinates using the estimated homography, enabling accurate mapping of the user’s hand motion onto the projected UI. The palm gesture serves as the primary modality for selecting virtual buttons. A palm input is classified as a valid click when the transformed position resides within the active region of a button, the vertical hand height falls within a predefined click threshold, and the hand remains stable within the region for a minimum dwell duration. This multi-condition criterion reduces false activations and ensures reliable detection of intentional inputs in a fully contactless environment.

Pinch gestures are employed as a higher-level interaction channel for context-aware command invocation. When a pinch gesture is detected, the system defines the fingertip location as a pinch point and dynamically generates a set of virtual command buttons around this point based on the current task context and the collaboration database. Concurrently, the fingertip trajectory functions as a virtual cursor: the user maintains the pinch posture while moving the hand to navigate the cursor toward a desired command. Upon pinch release, the cursor location is registered as the selected candidate, and the corresponding action is finalized through a palm-based confirmation click. This interaction mechanism enables users to issue complex robot-related commands without physical controls, providing high accessibility and operational flexibility—particularly for workers with limited hand function.

Examples of the gesture-based interaction are shown in Figure 6. It illustrates how palm gestures activate projected virtual buttons through region-based highlighting, and how pinch gestures generate contextual virtual menu boxes accompanied by a fingertip-driven cursor. These visualizations demonstrate the system’s ability to deliver clear, immediate spatial cues that support precise, contactless interaction on the work surface.

Figure 6.

Examples of gesture-based interaction using palm and pinch motions.

3.4.2. Speech and Natural Language Interaction

The speech and natural language interaction module provides a hands-free communication channel that enables users to issue verbal instructions to the workcell. The system integrates real-time speech recognition, task-intent inference, and speech synthesis, offering an accessible interaction modality for workers with limited upper-limb mobility.

User speech is transcribed using the Google Speech-to-Text (ko-KR) API in streaming mode. The transcribed text is processed by a domain-specialized Small Language Model (Llama-3-Ko-8B-Instruct), executed on an edge device via the llama.cpp runtime with GGUF Q5_K_M quantization. The model classifies utterances into four intent categories—tool delivery, part delivery, part fixation, and direct teaching—and extracts semantic parameters such as tool, part, or location. These outputs do not directly trigger robot actions; instead, they provide structured information that aligns user speech with the task representation defined in the collaboration database. Direct-teaching intents are used to support personalization. After adjusting the robot manually, the user may confirm the new setting verbally, and the system stores the robot’s configuration as a preferred position or posture for future operations. Thus, personalized task parameters accumulate within the user-specific collaboration database.

At the current stage, the module focuses on intent classification and semantic structuring rather than full conversational task execution. Robot behaviors are not triggered solely through voice commands, and integration with motion-planning modules is left for future work. System feedback is delivered using Google Text-to-Speech, which provides confirmation, clarification, and notification messages, ensuring transparency in the interaction process.

3.5. User-in-the-Loop Personalization for Collaborative Tasks

The personalization module enables the collaborative workcell to adapt its operational parameters to the individual characteristics and preferences of each user. Because workers with disabilities often exhibit diverse functional constraints—such as limited hand mobility, asymmetric limb control, or restricted reach—fixed, pre-defined robot behaviors are insufficient for ensuring ergonomic and efficient collaboration. To address this limitation, the proposed system adopts a user-in-the-loop adaptation framework, allowing users to explicitly modify robot behaviors through multimodal interaction and to store these adjustments as personalized collaboration parameters.

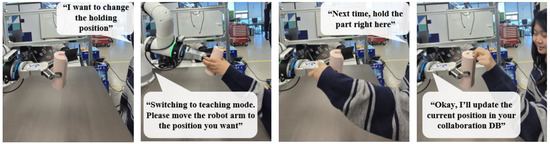

As illustrated in Figure 7, the personalization process is initiated by a spoken request indicating the user’s intent to modify a task parameter (e.g., “I want to change the holding position.”). The intent-inference module classifies such utterances as a request for entering the teaching mode, after which the robot transitions to a compliant, impedance-controlled state and provides auditory feedback (e.g., “Switching to teaching mode. Please move the robot arm to the position you want.”). In this mode, the user physically guides the robot end-effector to the preferred pose for grasping, holding, or delivering the target component. This direct manipulation is interpreted as an explicit expression of user preference.

Figure 7.

Demonstration of user-adaptive personalization through verbal interactions.

Once the user finishes adjusting the pose, a follow-up utterance—such as “Next time, hold the part right here.”—confirms the modification. At that moment, the system records the robot’s end-effector pose, including its 6-DoF position and orientation, gripper orientation, and the relative transformation defined within the task’s object coordinate frame. These parameters are then written to the user-specific collaboration database, ensuring that subsequent executions of the same task intent automatically reflect the user’s personalized configuration.

Through this mechanism, the proposed system departs from rigid, rule-based collaboration and instead supports preference-driven configuration that reflects explicit user adjustments. For users with physical impairments—such as those unable to stabilize components with both hands or those requiring specific delivery positions—the robot consistently executes task actions according to the user-defined parameters stored in the collaboration database. This approach is intended to support task comfort and safety by ensuring stable and repeatable personalized human–robot collaboration across repeated task executions.

4. System Integration of Robotic Workcell Platform

4.1. System Software Architecture

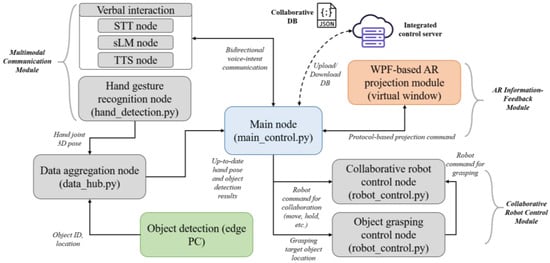

The proposed modular collaborative workcell operates on a Linux-based main control PC, where all core functionalities are deployed as ROS-style Python (v3.6) nodes. These nodes handle gesture recognition, verbal interaction, object perception, robot actuation, and projection-based user interfaces in a distributed yet tightly coordinated manner. The overall software topology is summarized in Figure 8, which delineates the data flow and control hierarchy across the system’s interaction, perception, and execution layers.

Figure 8.

Overview of the software architecture for the modular collaborative workcell.

At the center of the architecture is the Main node (main_control.py), which integrates heterogeneous input streams—gesture events, speech-derived intents, object detection results, and personalized task parameters from the collaborative database—and synthesizes them into executable robot actions and projection commands. The hand gesture recognition node continuously estimates 3D hand-joint positions, while the data aggregation node (data_hub.py) maintains synchronized, up-to-date representations of both gesture states and object detection outputs produced on an edge PC. The Main node queries this aggregated information on demand and incorporates it into the task-level decision process.

The verbal interaction subsystem consists of STT, a small Language Model (SLM), and TTS nodes. User speech is transcribed in real time via STT, and the sLM interprets the resulting text to infer the user’s task intent and argument parameters. These symbolic interaction cues are then relayed to the Main node, which resolves them against the current task context and the collaboration database before generating the corresponding robot or UI action.

Because the projection-based AR interface is implemented using a WPF framework on Windows, the system operates the projection module inside a virtualized Windows environment. Communication between the Linux-based Main node and the WPF module is achieved through a lightweight TCP protocol. The Main node issues protocol-defined rendering commands—for example, virtual button creation, instructional overlays, or progress indicators—which the projection module converts into real-time visual content. This design enables the use of a mature Windows-only visualization framework without compromising the uniformity of the Linux/ROS execution environment. In this architecture, the projection-based AR module implemented on the Windows environment maintains a stable update rate above human-perceivable thresholds, confirming that the separation between the AR interface and the robot control layer does not adversely affect system responsiveness.

Robot control is distributed between two dedicated nodes: a collaborative robot control node that handles motion generation for handover, positioning, and alignment tasks, and an object grasping control node that executes reinforcement learning–based grasping using depth information acquired at the gripper end-effector. Both nodes receive structured task-unit commands from the Main node and provide execution feedback that updates the global task state.

The Main node also manages the synchronization of the personalized collaboration database by downloading user-specific JSON files from the integrated control server during login and uploading modified versions after task completion. This enables persistent accumulation of user preferences—such as part placement positions, preferred grasp orientations, or personalized instruction settings—and ensures continuity across repeated workcell sessions.

Collectively, the architecture shown in Figure 8 supports modularity, extensibility, and robust real-time coordination across perception, interaction, and robot execution modules. Its node-based decomposition reduces coupling, facilitates parallel processing, and enables the seamless integration of heterogeneous modalities within a unified collaborative workflow.

4.2. Execution Scenario of the Integrated Collaborative Workcell

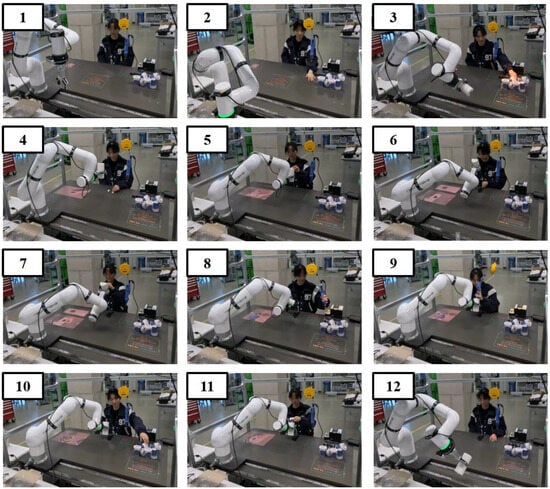

Figure 9 illustrates the end-to-end execution flow of the proposed modular collaborative workcell as experienced by an operator during a manufacturing-relevant task scenario. Once the user logs into the system, the personalized collaboration database associated with that operator is automatically retrieved from the integrated control server. The projection interface then presents the operator’s profile information along with individualized configuration parameters—such as tutorial-mode status, table height, and preferred interaction settings—directly on the work surface (Step 1). Concurrently, the stepwise task progress panel for the designated assembly process is displayed, accompanied by an audio prompt instructing the user to initiate the workflow by selecting the virtual “Start Task” button. Here, the operator refers to an able-bodied author performing the workflow under a simulated one-arm constraint (with one upper limb immobilized) for feasibility verification, rather than a controlled user study with workers with disabilities.

Figure 9.

Step-by-step operational scenario of the integrated collaborative workcell in a scenario-based feasibility demonstration.

When the user performs a palm-based selection gesture on the projected button, the gesture-recognition module evaluates the palm position, vertical height, and dwell stability to determine whether the input constitutes a valid activation (Step 2). Upon successful validation, the main control node transitions the workcell into active operation mode and begins delivering context-appropriate visual and auditory guidance throughout the collaborative task.

Steps 3 through 11 depict the sequential interaction between the operator and the system as the assembly process unfolds. During component retrieval phases, the projection system highlights the exact pick-up locations of the required parts to help the operator identify the correct items. When placement or fastening actions are required, the target assembly regions are emphasized through spatial highlighting, enabling precise execution of human–robot cooperative behaviors. Additionally, the system provides instructional media—including short tutorial videos, reference images, and explanatory text overlays—to assist the operator in understanding each sub-task. Whenever additional clarification is necessary, synthesized voice prompts offer supplementary explanations regarding task intent or safety considerations. All of these cues are updated in real time based on the most recent object-detection outputs and the procedural logic encoded within the personalized collaboration database.

Throughout the workflow, the operator may interact with the system using gesture-based commands to pause the process, resume operation, or request auxiliary functions. The main control node continuously integrates these user inputs with the current task state and generates corresponding action commands for the robot. The collaborative robot then executes transport, holding, or alignment tasks along safe, human-aware trajectories, ensuring seamless progression of the cooperative workflow.

In Step 12, the system notifies the operator of the successful completion of the designated task phase through both AR visualization and auditory feedback. This scenario illustrates how the proposed workcell is designed to support structured and guided collaborative assembly through real-time interaction, adaptive visual guidance, and perception-driven collaborative control. The feasibility demonstration described here was conducted by an able-bodied author under a simulated one-arm constraint.

5. Conclusions

This study presented an integrated human–robot collaboration framework aimed at supporting the accessibility, safety, and operational autonomy of workers with disabilities in industrial assembly environments. The proposed workcell consolidates multimodal interaction—encompassing gesture-, voice-, and language-based communication—with AR-projected task guidance, object-aware robotic assistance, and a structured collaboration database, thereby forming a coherent and operable system architecture.

A scenario-based feasibility demonstration with able-bodied participants under a simulated one-arm constraint indicated that the perception, projection, and control modules can be coherently integrated to support collaborative assembly tasks and are intended to alleviate physical demands associated with fine manipulation and part stabilization. The focus on upper-limb impairments was selected as a representative validation scenario, as such impairments impose direct constraints on fine manipulation and physical collaboration in industrial assembly tasks, rather than aiming to provide a comprehensive evaluation across all disability categories. Moreover, the personalized collaboration database enabled the system to accommodate user-specific preferences, establishing an effective foundation for individualized and disability-aware assistance.

While the present study primarily emphasizes system integration and collaborative task feasibility within a unified workcell framework, controlled baseline comparisons, module-level ablations, and standardized user-study metrics (e.g., task time, error rate, success rate, SUS, NASA-TLX) remain important next steps and will be addressed in future work.

Future work will focus on developing a multimodal intent inference mechanism capable of jointly interpreting gesture trajectories, spoken commands, task context, and robot state. Such a capability is expected to enable autonomous task progression without explicit virtual-button input, thereby further reducing cognitive and operational demands. The personalization framework will also be extended to support real-time adaptation and long-term learning of user habits. Additionally, although the present validation focused on upper-limb disabilities, subsequent studies will broaden the scope to lower-limb mobility impairments, developmental and cognitive disabilities, and users with auditory or speech limitations—enhancing the robustness and generalizability of the proposed system across a wider range of disability profiles.

Collectively, the findings demonstrate that the proposed framework provides a practical and extensible foundation for accessible, adaptive, and operator-oriented collaborative workcells, offering a practical basis for deployment in manufacturing environments seeking to improve productivity while enhancing inclusivity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.K. and M.-G.K.; methodology, Y.K.; software, D.K. (multimodal communication), D.H. (object detection), J.K. (AR projection), Y.K. and E.-J.J. (robot control); validation, Y.K., D.K. and D.H.; formal analysis, Y.K.; investigation, Y.K.; resources, Y.K.; data curation, Y.K.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.K.; writing—review and editing, Y.K.; visualization, Y.K.; supervision, Y.K.; project administration, E.-J.J.; funding acquisition, E.-J.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Technology Innovation Program (RS-2024-00417663) funded by the Ministry of Trade Industry & Energy (MOTIE, Korea).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mandischer, N.; Gürtler, M.; Weidemann, C.; Hüsing, E.; Bezrucav, S.-O.; Gossen, D.; Brünjes, V.; Hüsing, M.; Corves, B. Toward Adaptive Human–Robot Collaboration for the Inclusion of People with Disabilities in Manual Labor Tasks. Electronics 2023, 12, 1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hüsing, E.; Weidemann, C.; Lorenz, M.; Corves, B.; Hüsing, M. Determining Robotic Assistance for Inclusive Workplaces for People with Disabilities. Robotics 2021, 10, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drolshagen, S.; Pfingsthorn, M.; Gliesche, P.; Hein, A. Acceptance of Industrial Collaborative Robots by People with Disabilities in Sheltered Workshops. Front. Robot. AI 2021, 7, 541741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kremer, D.; Hermann, S.; Henkel, C.; Schneider, M. Inclusion through robotics: Designing human–robot collaboration for handicapped workers. In Transdisciplinary Engineering Methods for Social Innovation of Industry 4.0; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cais, M.; Culot, G.; Scalera, L.; Meneghetti, A. Enhancing inclusion of workers with disabilities in manufacturing: A human–robot collaborative assembly line balancing optimization model. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2025, 59, 2604–2609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucci, N.; Monguzzi, A.; Zanchettin, A.M.; Rocco, P. Workflow modelling for human–robot collaborative assembly operations. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2022, 78, 102384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Liau, Y.Y.; Kim, S.; Ryu, K. Model-Based Human–Robot Collaboration System for Small Batch Assembly with a Virtual Fence. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. Green Technol. 2020, 7, 609–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, U.; Yang, E. Human–Robot Collaborations in Smart Manufacturing Environments: Review and Outlook. Sensors 2023, 23, 5663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Liau, Y.; Kim, S.; Ryu, K. A Framework for Process Model Based Human–Robot Collaboration System Using Augmented Reality. In Advances in Production Management Systems. Smart Manufacturing for Industry 4.0; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 482–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, G.; Ghrairi, Z.; Wuest, T.; Hribernik, K.; Heuermann, A.; Liu, F.; Liu, H.; Thoben, K.-D. Towards Human Modeling for Human–Robot Collaboration and Digital Twins in Industrial Environments: Research Status, Prospects, and Challenges. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2025, 95, 103043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, G.M.; Petry, M.R.; Moreira, A.P. Augmented Reality for Human–Robot Collaboration and Cooperation in Industrial Applications: A Systematic Literature Review. Sensors 2022, 22, 2725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hietanen, A.; Pieters, R.; Lanz, M.; Latokartano, J.; Kämäräinen, J.-K. AR-based interaction for human–robot collaborative manufacturing. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2020, 63, 101891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loy, W.W.; Donovan, J.; Rittenbruch, M.; Belek Fialho Teixeira, M. Exploring AR-enabled human–robot collaboration (HRC) system for exploratory collaborative assembly tasks. Constr. Robot. 2025, 9, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunding, R.S.; Lystbæk, M.N.; Feuchtner, T.; Grønbæk, K. AR-supported Human–Robot Collaboration: Facilitating Workspace Awareness and Parallelized Assembly Tasks. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality (ISMAR), Sydney, Australia, 16–20 October 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, W.P.; Crouch, M.; Hoang, K.; Chen, C.; Robinson, N.; Croft, E. Improving Human–Robot Collaboration through Augmented Reality and Eye Gaze. ACM Trans. Hum. Robot. Interact. 2025, 14, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas-Martínez, Á.-G.; Cunillé-Rodríguez, J.; Aquino-López, E.; García-Moreno, Á.-I. Multimodal Human–Robot Interaction Using Gestures and Speech: A Case Study for Printed Circuit Board Manufacturing. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2024, 8, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Leu, M.C.; Yin, Z. Real-Time Multi-Modal Human–Robot Collaboration Using Gestures and Speech. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. 2022, 144, 101007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zheng, P.; Li, S.; Wang, L. Multimodal Human–Robot Interaction for Human-Centric Smart Manufacturing: A Survey. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2024, 6, 2300359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomason, W.; Knepper, R.A. Recognizing Unfamiliar Gestures for Human–Robot Interaction Through Zero-Shot Learning. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Symposium on Experimental Robotics (ISER 2016), Nagasaki, Japan, 3–8 October 2016; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 841–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Gangaraju, K.; Yuan, F. Multimodal perception-driven decision-making for human–robot interaction: A survey. Front. Robot. AI 2025, 12, 1604472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freire, I.T.; Guerrero-Rosado, O.; Amil, A.F.; Verschure, P.F.M.J. Socially adaptive cognitive architecture for human–robot collaboration in industrial settings. Front. Robot. AI 2024, 11, 1248646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fant-Male, J.; Pieters, R. A Review of Personalisation in Human–Robot Collaboration and Future Perspectives Towards Industry 5.0. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.20447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan, B.; Ramachandran, A.; Spaulding, S.; Glas, D.F.; Leite, I.; Koay, K.L. Personalization in Long-Term Human–Robot Interaction. In Proceedings of the 2019 14th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction (HRI), Daegu, Republic of Korea, 11–14 March 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanmahin, R.; Masoud, S.; Rickli, J.; Djuric, A. Human–robot interactions in manufacturing: A survey of human behavior modeling. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2022, 78, 102404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.