Abstract

The elevated morbidity and mortality of kidney cancer make the precise, automated segmentation of kidneys and tumors essential for supporting clinical diagnosis and guiding surgical interventions. Recently, the segmentation of kidney tumors has been significantly advanced by deep learning. However, persistent challenges include the fuzzy boundaries of kidney tumors, multi-scale problems with kidney and renal tumors regarding location and size, and the strikingly similar textural characteristics of malignant lesions and the surrounding renal parenchyma. To overcome the aforementioned constraints, this study introduces a boundary-enhanced multi-scale feature fusion network (BEMF-Net) for endoscopic image segmentation of kidney tumors. This network incorporates a boundary-selective attention module (BSA) to cope with the renal tumor boundary ambiguity problem and obtain more accurate tumor boundaries. Furthermore, we introduce a multi-scale feature fusion attention module (MFA) designed to handle 4 distinct feature hierarchies captured by the encoder, enabling it to effectively accommodate the diverse size variations observed in kidney tumors. Finally, a hybrid cross-modal attention module (HCA) is introduced to conclude our design. It is designed with a dual-branch structure combining Transformer and CNN, thereby integrating both global contextual relationships and fine-grained local patterns. On the Re-TMRS dataset, our approach achieved mDice and mIoU scores of 91.2% and 85.7%. These results confirm its superior segmentation quality and generalization performance compared to leading existing methods.

1. Introduction

Within the urinary system, renal tumors constitute a significant proportion of malignancies [1], accounting for about 2% to 3% of malignant tumors in adults. If renal tumors are left unchecked, cancer metastasis will form and cause deterioration. Early detection and accurate tumor segmentation is fundamental to both diagnostic and therapeutic decisions, thereby enhancing long-term survival and patient well-being. However, traditional renal tumor segmentation methods often rely on doctors’ personal experience and suffer from subjectivity and inefficiency, thus falling short of the demands of modern precision medicine, so there is a need to develop automated, high-precision computer-aided segmentation algorithms. For the time being, medical image segmentation mainly focuses on polyps and other parts of the body, and the segmentation of renal tumors also focuses only on CT images or MRI images used for pre-surgical diagnosis, and because of the differences between the tumor region and the actual surgery, there are still some problems in using endoscopic images to accurately cut renal tumors, such as, the kidney in endoscopic images tumor boundaries are blurred, the multi-scale problem of kidney and kidney tumor regarding location and size and the similarity in texture feature distribution between the tumors and surrounding renal organ tissues. These factors contribute to the relatively low segmentation accuracy of the algorithms.

Deep learning has emerged as a key driver of advancement in medical image segmentation over the past several years, unlocking substantial improvements in performance and application [2]. U-Net [3] and its variants, including UNet++ [4], ResUNet [5], ResUNet++ [6], and DoubleUNet [7], constitute a family of encoder–decoder networks adept at extracting local features. This capability primarily leverages convolutional kernels to effectively delineate textural patterns and lesion boundaries. As the spatial resolution of feature maps progressively diminishes throughout the encoding pathway, fine-grained information inevitably degrades. Although the decoding stage endeavors to reconstruct this forfeited detail, substantial semantic misalignment persists between the two modules, compounded by extraneous background interference. For kidney tumor segmentation, U-shaped CNN-based models are challenged by their limited receptive fields, which hinder effective global context capture. Consequently, these models often struggle to differentiate tumors from healthy tissue, resulting in suboptimal segmentation accuracy [8,9]. Consequently, Vaswani et al. proposed the Transformer architecture to address these limitations. Motivated by the notable success of Transformers in NLP, the Vision Transformer (ViT) was proposed by Dosovitskiy et al. [10], extending this framework to computer vision and constituting a landmark as the inaugural stand-alone Transformer model designed for image classification. Chen et al. [11] introduced TransUnet, a hybrid architecture integrating CNNs and Transformers. By integrating Transformer-based sequence encoding with a U-shaped CNN architecture, TransUnet achieves a dual enhancement: robust global context modeling and effective utilization of fine-grained local features, leading to record-breaking performance on multi-organ CT segmentation. Wang et al. [12] introduced Pyramid Vision Transformer (PVT), a novel backbone that avoids convolutional layers and targets dense prediction problems. This is realized by achieving pyramid representation through specific modifications to the Transformer, which provides the multi-scale learning capability absent in ViT and enables various pixel-level tasks. Furthermore, PVT demonstrates superior performance to CNNs in detection and segmentation tasks. A fundamental difference between Transformers and CNNs lies in their capacity for modeling long-range dependencies, with Transformers excelling at capturing global context. Transformers achieve this via multi-head self-attention (MHSA), which explicitly models pairwise relationships across the entire image to synthesize a cohesive global representation—a capability inherently limited in standard CNN architectures. By leveraging its ability to model long-range dependencies and global context, the Transformer architecture significantly enhances segmentation tasks, facilitating precise lesion localization [13]. Although existing models represent improvements over earlier approaches, these methods remain limited in capturing fine-grained details within medical images. They lack local information, are modeled within a single-scale context, and neglect certain cross-scale dependencies and consistency. Consequently, Transformers still fall short when confronting the challenges of renal tumor segmentation [14,15,16]. Thus, advancing model development remains imperative. The key objectives are the precise delineation of tumor boundaries and the reliable identification of lesions against similar tissue, which are foundational to automating the segmentation of renal tumors in endoscopic images. Therefore, to realize these objectives, we propose a boundary-enhanced multiscale feature fusion network (BEMF-Net). This network is a medical image segmentation model built upon the PVTv2 backbone network with multi-scale feature fusion and attention mechanism.

This end, we designed the multi-scale feature fusion attention module (MFA) to distill localized details from the hierarchical features produced by the encoder. This module aggregates and enhances features at each stage, integrating information through different receptive fields to accommodate the multi-scale nature of kidney tumors. Following the MFA, a hybrid cross-modal attention module (HCA) is introduced to build the decoder designed to integrate global, long-range contextual relationships with localized appearance details. In addition, a boundary-selective attention module (BSA) is specifically designed to enhance edge features for precise boundary delineation.

In summary, our main contributions include:

- A boundary-enhanced multi-scale feature fusion network called BEMF-Net is proposed to automatically delineate renal tumors in endoscopic images and highlight the lesion regions, thereby achieving effective tumor extraction.

- A multi-scale feature fusion attention module called MFA is proposed. This module refines and enriches backbone features through convolutional branches of different receptive fields, thereby integrating more comprehensive local and global information.

- We propose a hybrid cross-modal attention module called HCA for the dual purpose of modeling long-range interactions and encoding local appearance details, which equips the decoder to represent features more effectively.

- We propose a boundary selective attention module called BSA, which specializes in dealing with boundary regions and heightens the model’s perceptual acuity towards edges, so that different levels of features are boundary-aware.

In conclusion, BEMF-Net serves as a reliable solution for automating renal tumor segmentation from endoscopic imagery, offering precise localization support to enhance clinical decision-making in surgery. This paper is structured into the following sections: Section 2 summarizes related work. Our proposed method is elaborated in Section 3. Section 4 describes the experiments and findings. The discussion and conclusions are provided in Section 5 and Section 6, respectively.

2. Related Works

The field of kidney tumor segmentation has witnessed extensive research efforts, which primarily fall into two categories: one rooted in traditional image processing [17], and the other driven by modern deep learning.

2.1. Traditional Image Segmentation

Before deep learning became prevalent, kidney tumor segmentation mainly relied on traditional image processing techniques, where the core idea was to achieve target region localization and segmentation by manually designing features in conjunction with mathematical modeling. These methods can be broadly categorized into three groups: region-based segmentation methods, segmentation methods based on a priori knowledge models, and segmentation methods with deformable models. Pohle R et al. [18] proposed an autonomously learnable region-growing algorithm for tumor organ segmentation, whose segmentation results are affected by factors such as the target shape and region similarity. Lin DT et al. [19] proposed an adaptive region-growing algorithm, which makes use of a priori knowledge to localize renal tissues before subsequent operations. Yan G et al. proposed a region-growing algorithm, which uses a priori knowledge to localize kidney tissues before subsequent operations. Shim H et al. [20] proposed a semi-automated segmentation of kidneys through user guidance based on graph cut and seed growth techniques. Caselles et al. [21] proposed a Geodesic Active Contours (GAC) model for tumor image processing by using gradients to facilitate learning, which can segment the image with more distinctive tumor regions. The more obvious tumor region in the image. It can be seen that most of the traditional kidney tumor segmentation methods require manual intervention and have poor robustness and bad segmentation results. In addition, the processing of traditional image processing methods is more complicated, thus falling short of actual medical needs. The advancement of deep learning technology has spurred growing interest in developing segmentation algorithms for kidney tumors.

2.2. CNN-Based Methods

Compared with traditional methods, deep learning’s strong adaptability facilitates end-to-end processing, enabling autonomous learning and extraction of target features without human intervention. This has propelled it to become the mainstream technology in image processing more easily and efficiently [22,23,24]. Introduced by Ronneberger et al. [3], U-Net has established itself as the cornerstone of medical image segmentation. Its symmetric encoder–decoder architecture, together with skip connections, effectively mitigates the loss of local details in structures like the kidney. The U-Net architecture has inspired numerous variants widely used in medical image segmentation. For example, Unet++ [4] incorporates deep supervision to enhance segmentation performance. Another key variant, resUnet++ [6], integrates multiple advanced components: residual blocks, squeeze-and-excitation (SE) modules [25], atrous spatial pyramid pooling (ASPP) [26], and attention mechanisms, collectively boosting its multi-scale information processing capability. The PraNet model [27], proposed by Fan et al., is designed to refine segmentation edges through successive stages using a reverse attention module.; however, PraNet largely disregards global information. HardNet-MSEG [28], proposed by Huang et al., utilizes a multi-branch convolutional structure to broaden its effective receptive field, achieving efficient inference speeds for polyp semantic segmentation. Yet, as this network utilizes only high-level features, it overlooks numerous shallow-level detail features. Lou et al.’s CaraNet [29] improved upon PraNet by introducing Axial Reverse Attention and a Channel Feature Pyramid (CFP) module, enhancing segmentation of small objects, yet it disregarded contextual information across different scales. FRBNet [30] first localizes tumor boundaries within breast ultrasound images via a boundary detection module (BD), then integrates this information into coarse predictions using a feedback refinement module (FRM). A key drawback of this approach is its tendency to over-emphasize low-level features that are not pertinent to tumor boundaries. Despite the notable advances traditional CNNs have made in segmentation, they often lack adequate mechanisms to model global context and may lose precise spatial information during feature extraction.

2.3. Transformer-Based Methods

The seminal work of Vaswani et al. [13] introduced the Transformer model, initially applied in NLP and later forming the basis for its widespread adoption across diverse domains. Dosovitskiy et al. made a pivotal contribution with the Vision Transformer [10], which successfully transplanted the Transformer model to the domain of computer vision. It tackles image recognition through multi-head self-attention, demonstrating the framework’s versatility beyond NLP. To adapt the Swin Transformer for medical image segmentation, Liu et al. [31] introduced its sliding window operation, enabling the extraction of multi-level visual features. The Pyramid Visual Transformer (PVT), introduced by Wang et al. [12], is distinguished by its incorporation of a spatial reduction attention mechanism. It maintains positional fidelity through hierarchical aggregation of bottom-up features and top-down propagation, thereby preserving critical spatial information throughout feature extraction. A recognized limitation of these models lies in their self-attention, which often fails to capture fine-grained local contextual relationships. To address this, Wang et al. [32] developed PVT v2, where a key modification is the insertion of convolutional layers within the feedforward blocks for targeted local enhancement. However, the model’s capacity to capture nuanced local context is still limited. Polyp-PVT [33] incorporates a dual-module design for feature integration, comprising a Cascade Fusion Module (CFM) for fusing high-level semantics and a subsequent Similarity Aggregation Module (SAM) that models cross-level feature relationships. Incorporating a Spatial Reverse Attention (SRA) module to refine boundaries, MSRAformer [34] by Wu et al. builds upon a Swin Transformer backbone. High-level features encode semantic context, while low-level features preserve spatial details. Despite their complementary nature, the naive concatenation of high- and low-level features overlooks the inherent semantic gap between them, leading to suboptimal fusion. Although Transformer models excel at establishing long-range connections, they remain deficient in extracting local details. Furthermore, these models neglect the importance of restoring boundary details, necessitating continued design efforts to enhance performance. This paper proposes a novel Transformer architecture (BEMF-Net) to address these limitations.

2.4. Segmentation Methods for Kidney Tumors

Current deep learning-based research on kidney tumor segmentation has predominantly utilized CT or MRI images, while studies on endoscopic image segmentation remain relatively scarce. Cruz et al. [35] demonstrated effective adaptation of the U-Net architecture for kidney segmentation in CT scans. This was achieved through a coarse-to-fine segmentation strategy designed for automatic delineation. Xie et al. [36] presented the SERU model, which integrates ResNeXT modules into the U-Net encoder in place of standard convolutions to achieve better performance. Geethanjali et al. [37] addressed the issue that the standard U-Net may overlook critical features during encoding by integrating an attention gate mechanism into the model. This attention mechanism directs the model’s focus to salient tumor regions (such as tumor boundaries) during decoding and reconstruction while suppressing extraneous background details, leading to improved segmentation accuracy. Due to their inherently local receptive fields, these CNN architectures face fundamental difficulties in integrating the global understanding needed to segment kidney tumors, which are not only multi-scale and amorphous but also often poorly defined, thereby limiting segmentation efficacy. Aiming to advance segmentation performance, Hou et al. [38] proposed DCCTNet, a hybrid architecture that enhances endoscopic kidney tumor analysis by fusing CNN-driven multi-scale insights with Transformer-based global comprehension, leading to marked improvements. Nevertheless, this model achieved only 81.2% average accuracy on the test set, underscoring the untapped potential and necessitating further algorithmic advances in semantic segmentation for renal tumors from endoscopic images. Hou et al. [39] introduced a novel three-stage deep learning model, TSG-Net, which progressively optimizes segmentation results using internally generated guidance information. This approach effectively addresses the inherent difficulties in segmenting renal tumors from CT images, achieving state-of-the-art performance at the time.

3. Proposed Method

3.1. Overview

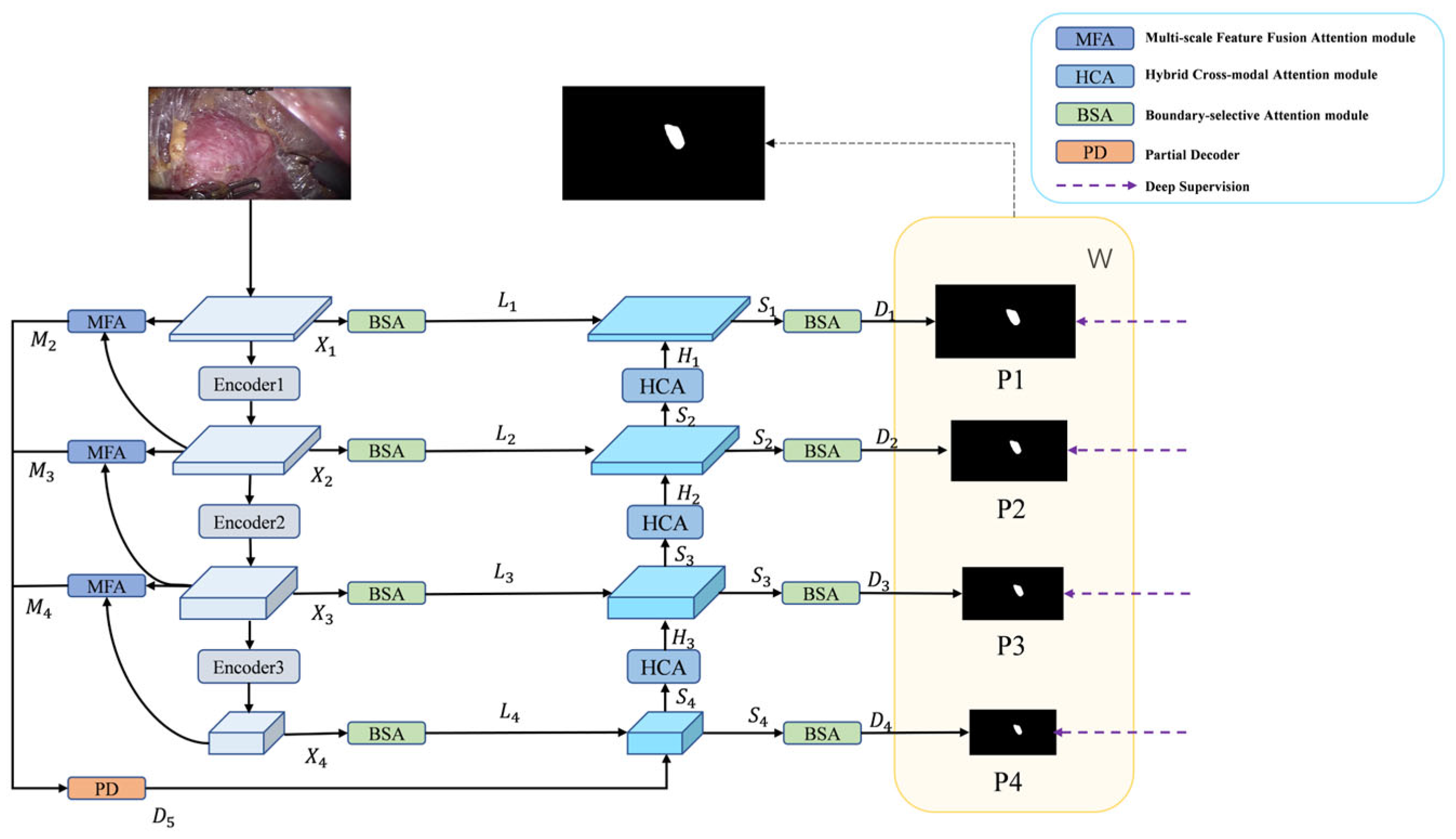

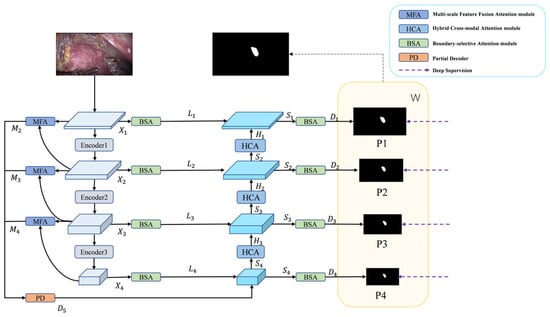

Figure 1 illustrates the overall architecture of BEMF-Net. The network comprises four core components: a Pyramid Vision Transformer encoder, a BSA module, an MFA module, and a HCA module. The Transformer encoder serves as the backbone, extracting hierarchical visual features from the input image. For the encoder, we employ PVTv2 [32] to extract robust backbone features and richer foreground cues for decoding. This choice offers distinct advantages over traditional CNNs, which are more locally focused: PVTv2 exhibits a superior capacity for global information integration and demonstrates greater resilience to input variations. To adapt to tumor multiscale variations, the MFA module aggregates and enhances features at each stage, fusing information from diverse receptive fields to obtain enriched local and global representations. These multi-stage features are then integrated by a Partial Decoder (PD) [40] to produce an initial coarse segmentation. However, the PD output primarily highlights the foreground region and remains inadequate for delineating accurate boundaries in areas of ambiguity. Therefore, by enhancing boundary information through BSA, an interactive mechanism harmonizes low-level detail with high-level semantics to achieve more precise boundaries. The HCA module serves as the fundamental decoder unit, designed to strikes a balance between modeling long-range dependencies and preserving local details. It stepwise reconstructs the prediction mask from low-level features. This output is then refined by a BSA module to produce a more accurate prediction. Finally, learnable weights are applied to the pyramid prediction masks to optimize segmentation performance.

Figure 1.

The architecture of BEMF-Net, based on a PVTv2 encoder and three attention modules: BSA, MFA, and HCA.

3.2. PVTv2 Backbone Network

Given the enhanced ability of Vision Transformers to model long-range context compared to CNNs [41], we adopt PVTv2 as the backbone, which produces a four-level pyramid of features Xi, where i ∈ {1, 2, 3, 4}. The enhanced outputs M2, M3, and M4 are generated by the MFA module, which performs multiscale aggregation and enhancement on consecutive levels of the four input features. Initial rough segmentation result D5 is obtained by PD aggregation of features M2, M3, and M4 from different stages of outputs of the MFA module. D5 is then combined with the detail-enhanced features, L4 multiscale feature fusion output from the BSA, to obtain a sharper boundary Segmentation. The combined features are then up-sampled by the decoder to obtain S4 and delivered to the HCA module to obtain H3, which is multiscale fused with the laterally connected L3 multiscale fusion that has been enhanced by the BSA details to obtain S3 and delivered to the HCA module to obtain H2, and then the step is repeated to obtain S2, H1, and S1. The four pyramid output features Si are obtained, where i ∈ {1, 2, 3, 4}, and then go through the BSA module to get the prediction graph Di, where i ∈ {1, 2, 3, 4}, respectively, to obtain a clearer boundary segmentation. Finally, the decoder outputs Di at each stage are processed through a 1 × 1 convolutional layer followed by upsampling, thereby producing the final binary masks P1, P2, P3, and P4. The predictions from different stages are integrated by weighting Pi with trainable weight coefficients W, preserving semantic information at various scales to ultimately generate the prediction output mask. The complete workflow of BEMF-Net can be described by the following equations:

where i represents the input image, and T, M, PD, B, DC and H denote the PVTv2, MFA, PD, BSA, Decoder and HCA modules, respectively.

3.3. Multi-Scale Feature Fusion Attention Module

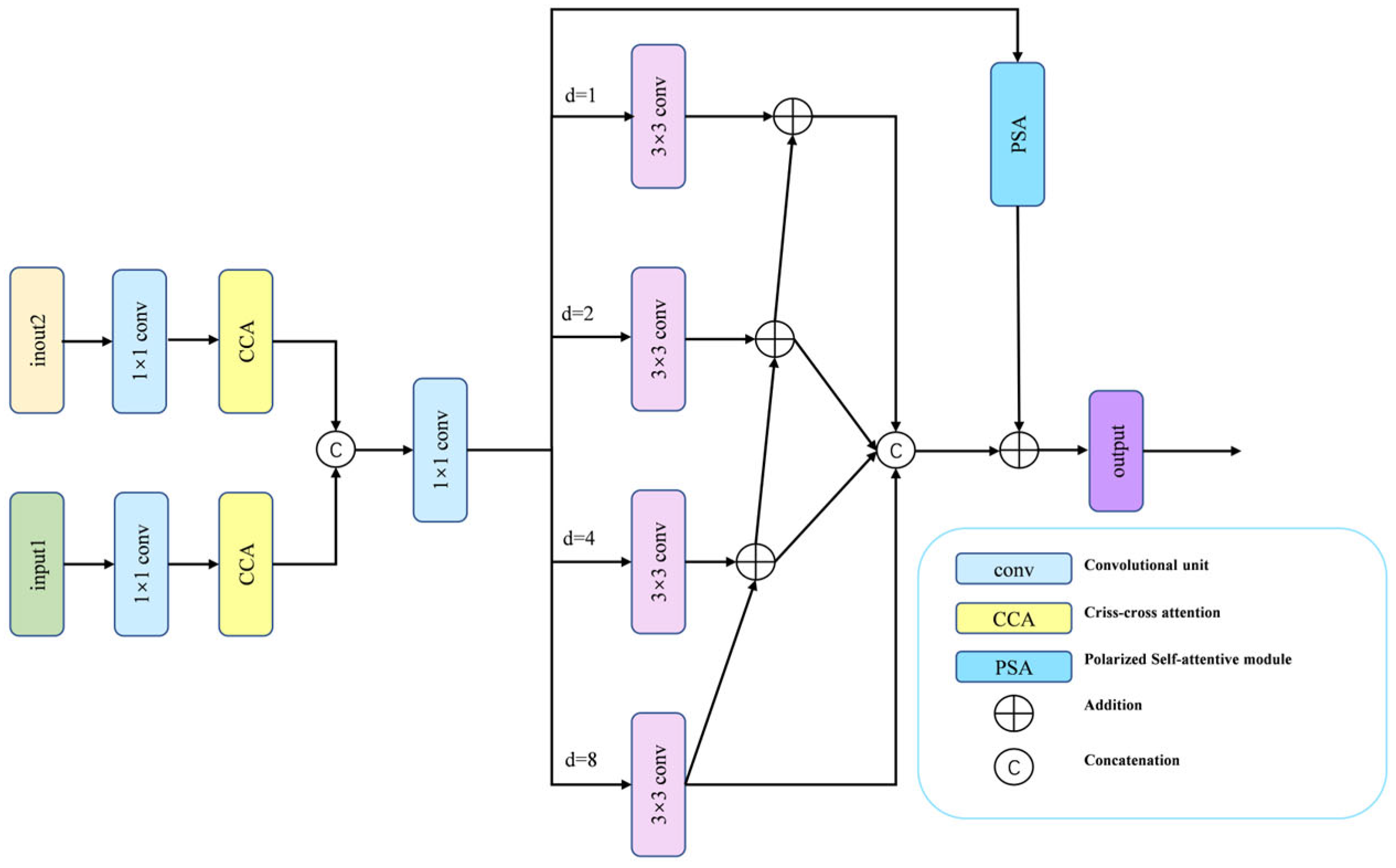

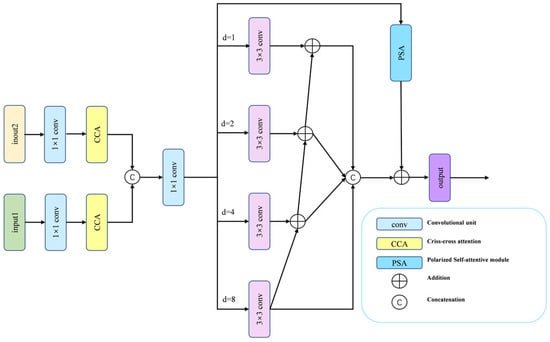

During renal tumor resection surgery, endoscopic views are often obstructed by instruments or surrounding tissue, causing tumors to appear fragmented and highly variable in size and shape. This multi-scale presentation poses a significant segmentation challenge. Conventional approaches—such as naively concatenating multi-level features or relying solely on self-attention—often struggle to simultaneously incorporate the necessary long-range contextual information and precise local details for accurate delineation. To overcome these limitations, we devise the MFA module, which systematically integrates three complementary mechanisms in a hierarchical fusion strategy, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The MFA module includes two CCA modules and a CFP module.

The MFA module first reduces the channel dimensions of two adjacent feature maps via 1 × 1 convolution to lower computational cost. These features then pass through Criss-Cross Attention (CCA) [42], which captures cross-spatial and cross-channel dependencies while suppressing noise and redundant information, thereby establishing long-range contextual relations. A cross-layer feature aggregation is performed by upsampling and concatenating lower-level features with higher-level ones, before the combined features are passed to the Channel Feature Pyramid (CFP) [43] module for further processing. The CFP employs a four-branch architecture of parallel 3 × 3 dilated convolutions with dilation rates (1, 2, 4, 8), explicitly enabling multi-scale context aggregation. To integrate the four branches, we apply hierarchical feature fusion (HFF) [44] to connect the outputs of the four branches, followed by Polarized Self-Attention (PSA) [45] to adaptively recalibrate spatial and channel weights. The final MFA representation is generated by integrating the PSA-recalibrated features with the HFF outputs. This design ensures comprehensive feature coverage across all scales, fosters effective information exchange between receptive fields, and empowers the model to distill richer, more discriminative feature combinations from complex medical images.

While CFP and CCA have been used separately for multi-scale feature extraction and cross-channel attention, our MFA module integrates them within a novel hierarchical fusion framework enhanced by PSA. Unlike prior methods that simply concatenate multi-scale features, we introduce residual connections and HFF to preserve fine-grained details while suppressing noise—a crucial capability for accurately segmenting renal tumor boundaries in endoscopic images.

3.4. Hybrid Cross-Modal Attention Module

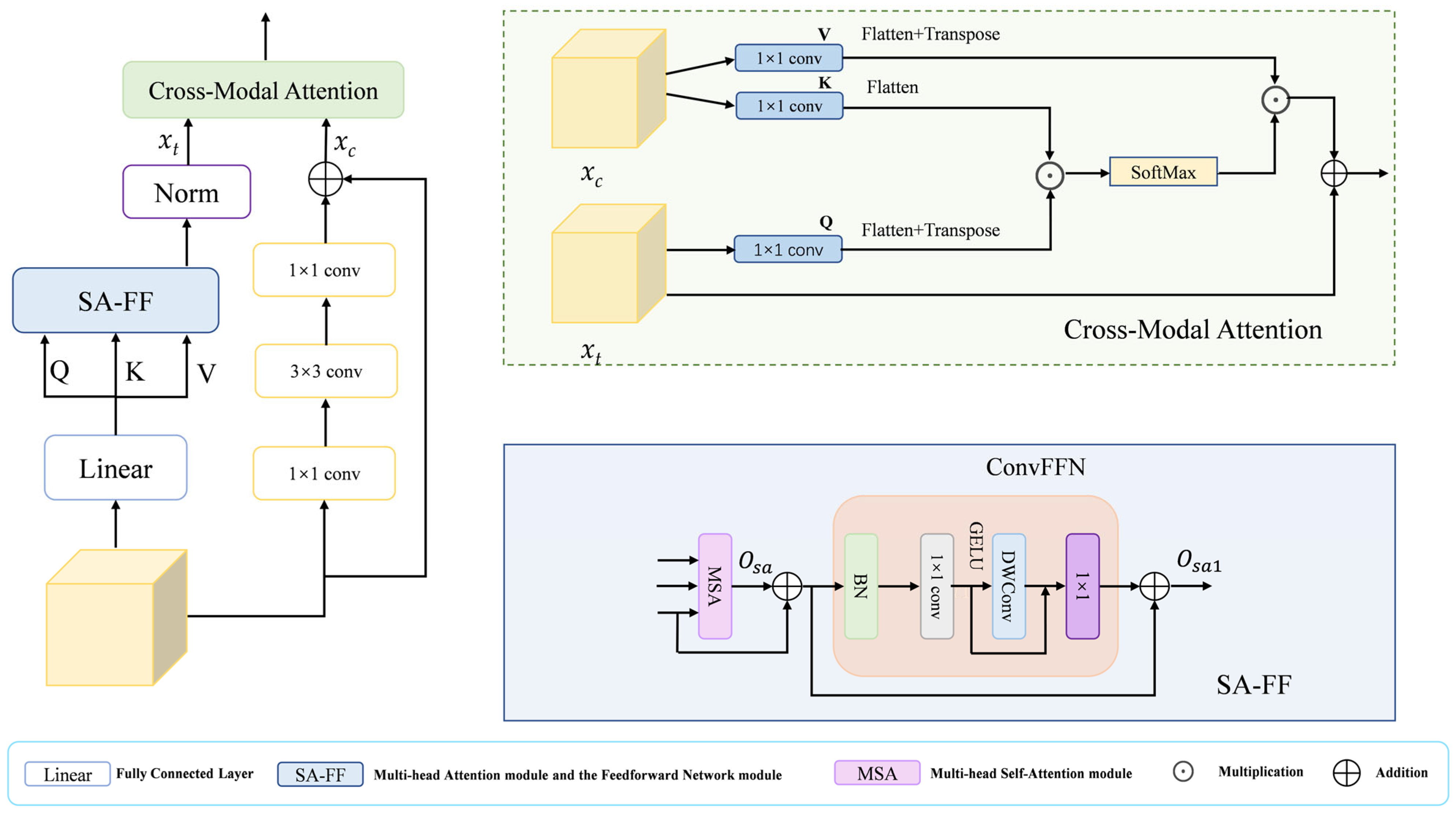

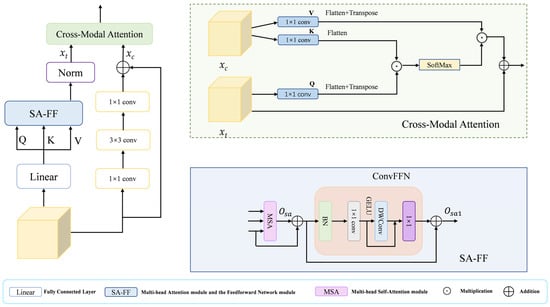

The decoder in a segmentation network must reconstruct high-resolution details from low-resolution, semantically rich features. A direct fusion often leads to a semantic mismatch stemming from the representational discrepancy across feature hierarchies. Pure Transformer decoders excel at modeling global context but may overlook local textures, while pure CNN decoders capture local patterns but lack long-range reasoning. To bridge this gap, we introduce the HCA module, as illustrated in Figure 3, which leverages a dual-branch architecture: one branch employs Transformer-based Multi-head Self-Attention (MSA) for modeling global interactions, thereby achieving long-range contextual understanding, while the other branch uses a lightweight CNN to extract fine-grained local appearances. These two complementary feature streams are then dynamically fused through a novel Cross-Modal Attention (CMA) mechanism, where the semantic-rich “query” from the Transformer branch attends to the detail-preserving “key” and “value” from the CNN branch. This design explicitly aligns global semantics with local details, effectively mitigating the semantic gap and enhancing the recovery of small or boundary-aware structures.

Figure 3.

The HCA module includes a Cross-Modal Attention module and an SA-FF module.

The HCA module synergizes CNN and Transformer architectures, harnessing the former’s proficiency at local feature extraction and the latter’s capacity for global context modeling. Thereby equipping it to effectively handle the intricate structures and background complexities in medical images. Specifically, in the HCA module, the input features are obtained as query Q, key K, and value V through the fully connected layer, and then they are input into the SA-FF module, which mainly consists of the Multi-head Attention Module and the Feedforward Network Module. The Multi-head Self-Attention (MSA) module computes the output as follows:

where D is the key vector dimension. This formulation controls the variance of the attention weights, aiding optimization and efficiency. The value V is then summed with and is then processed by the feed-forward network module (ConvFFN) to obtain , where the formula is

Additionally branch 2 models the local details of the features using purely convolutional operations

where δ(·) denoted by ReLU activation function, () and () denote 1 × 1 convolutional layers and denotes 3 × 3 convolutional layers. Finally, the results of the two branches are fed into the Cross-Modal Attention (CMA) module to dynamically fuse the features of the two branches and improve the detail recovery of small targets. In the CMA module, three independent 1 × 1 convolutional layers are used to process branch 1 and branch 2 to generate Q, K and V, where Q comes from and extracts the semantic information as query vector through channel compression, and K and V both come from but have different roles K and V both come from but have different roles. The K is compressed to align its channel count with that of Q for efficient similarity computation, while the V retains the original feature dimensions to preserve complete detail information. Then the cross-modal spatial attention maps ([B, HW, HW]) of Q and K are computed by matrix multiplication, then normalized by SoftMax, and then weighted and summed with the weight matrix of V, and then fused with by residual linkage. This facilitates feature fusion while preserving original semantic understanding and enhancing perception of local details. Throughout this process, the spatial dimensions remain unchanged, achieving effective cross-modal feature fusion solely through channel transformations and attention mechanisms. By applying the HCA module in the decoder, semantic misalignment issues are resolved and local image details are restored, thereby generating reliable prediction masks.

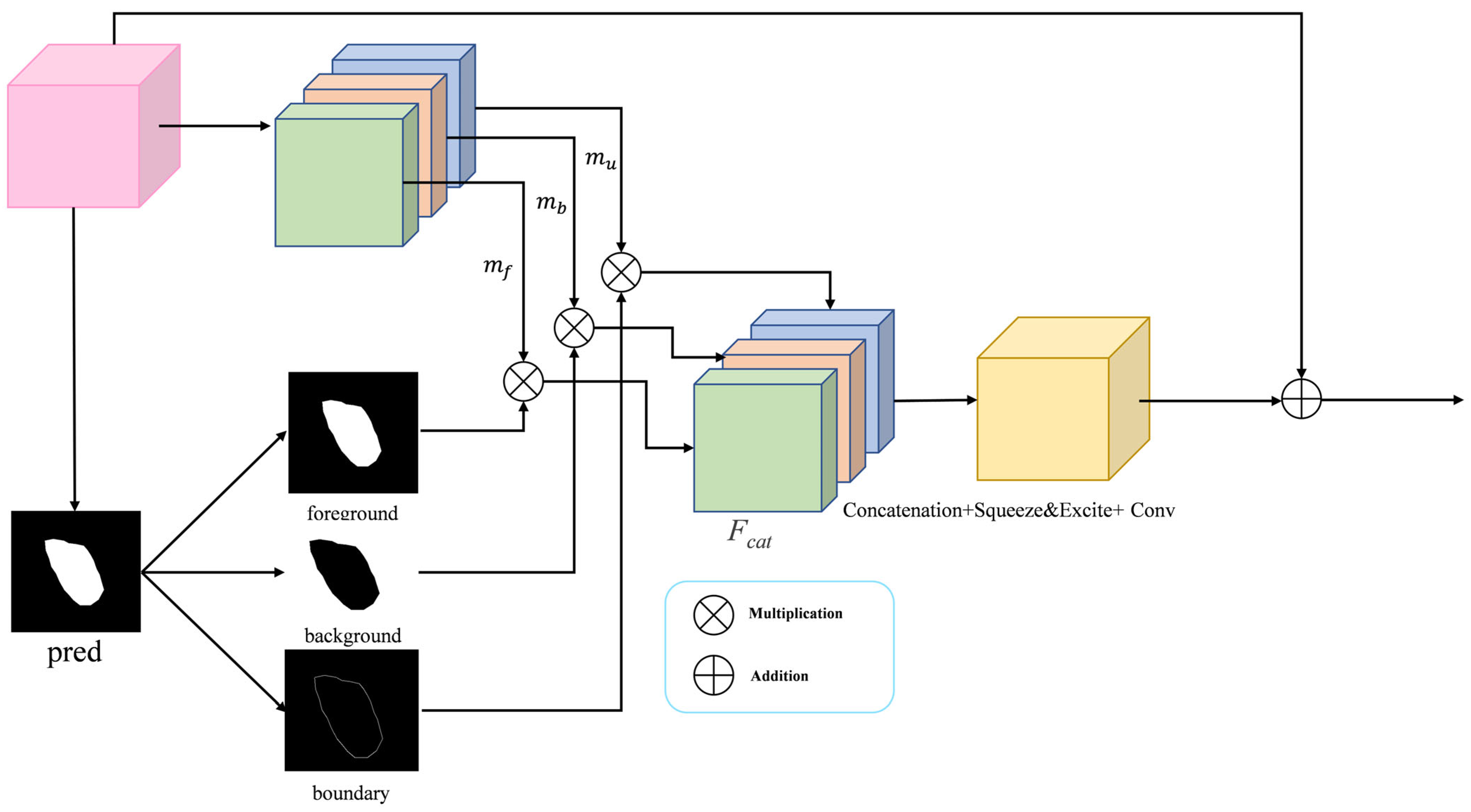

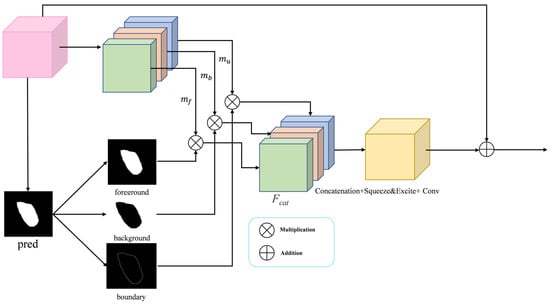

3.5. Boundary-Selective Attention Module

During a clinical procedure, surgeons first locate the tumor mass and then meticulously delineate its margins—a process hindered in endoscopic imaging by motion blur, reflections, and the inherent difficulty of Transformers in modeling fine-grained local context. Aiming to resolve the resulting boundary ambiguity, we propose the BSA module. Its core innovation is to explicitly decompose features into three semantically distinct streams: foreground (tumor core), background (normal tissue), and boundary (the high-uncertainty transitional region). This allows the model to apply targeted enhancement specifically to ambiguous edges, drawing inspiration from salient object detection where inverse features provide complementary local contrast cues. The architecture of the BSA is shown in Figure 4. The BSA receives the multilayered feature maps extracted from the backbone network, and on the one hand, it divides them into three parts, mf, mb, and mu, according to the channels, which correspond to the foreground, the background, and the boundary, respectively. On the other hand, based on the input feature maps, they are averaged over the channel dimension (dim = 1) to produce a rough attention map as the input prediction map (pred) for the BSA module, based on this prediction map, three attention maps are computed: the foreground attention map (pred), the background attention map (1 − pred), and a boundary attention map (). Finally, a weighted fusion is performed by multiplying each feature map with its corresponding attention map, a process that emphasizes relevant and suppresses irrelevant spatial regions prior to aggregation. The merged feature maps are recalibrated by a Squeeze-and-Excite block for channel attention processing, which further enhances tumor-related features while suppressing noise and irrelevant information. Finally, feature fusion is achieved via a convolutional layer for integration, which is then combined with the input feature maps through a residual connection to produce the enhanced output. The BSA module is systematically applied to features at every encoder and decoder level. This design thereby achieves a synergistic fusion: preserving fine-grained boundary details from shallow layers while incorporating semantic edge cues from deep representations. Our method improves the delineation of tumor boundaries, thereby increasing segmentation fidelity within challenging medical imaging contexts.

Figure 4.

The BSA module has the main function of aggregating fine boundary features.

3.6. Loss Function

We train BEMF-Net with deep supervision, where predictions Pi (i = 1, 2, 3, 4) from each stage are incorporated into the supervisory signals. The overall loss function is defined as the sum of binary cross-entropy (BCE) loss [46] and weighted IoU loss [46]:

In this formulation, Pi represents the prediction from the -th stage of the decoder, and G is the corresponding ground-truth mask.

4. Experimental Results

The experimental evaluation is structured in two parts. First, we validate BEMF-Net on a public dataset to establish baseline performance. Subsequently, a comprehensive analysis is conducted on our proprietary endoscopic renal tumor dataset (Re-TMRS), encompassing quantitative, qualitative, and module-wise ablation studies. Our method is compared against eleven state-of-the-art models, including Unet [3], Unet++ [4], CaraNet [29], HarDNet-MSEG [28], Multi-scale-Resnet, MSRAformer [34], Polyp-PVT [33], PraNet [27], HSNet [47], GSNet [48], and NPD-Net [49]. Additionally, generalization testing on polyp datasets is conducted with the official implementations provided by the original authors.

4.1. Datasets

We adopt six datasets: the renal tumor dataset Re-TMRS, and five polyp datasets—Kvasir-SEG [50], CVC-ClinicDB [51], CVC-ColonDB [52], ETIS [53], and CVC-T [54].

The Re-TMRS dataset is constructed from surgical videos of renal tumor resections provided by urologists at Anhui Medical University. It comprises video segments from 10 patients (5 men and 5 women, aged 44–71) across various operative phases, including exposure, resection, and haemostasis. The dataset encompasses multiple renal cell carcinoma subtypes (e.g., clear cell and papillary carcinoma) and tumor stages (T1–T3a), thereby capturing considerable inter-patient variability and ensuring clinical relevance despite the limited sample size.

All videos were acquired using an Olympus CV-190 high-definition endoscopic system under xenon light illumination, with a native resolution of 1920 × 1080 pixels. Some frames exhibit resolution variations due to intraoperative changes in lens distance or viewing angle. Common endoscopic artifacts such as motion blur, specular reflection, and blood occlusion are present, reflecting real-world surgical conditions.

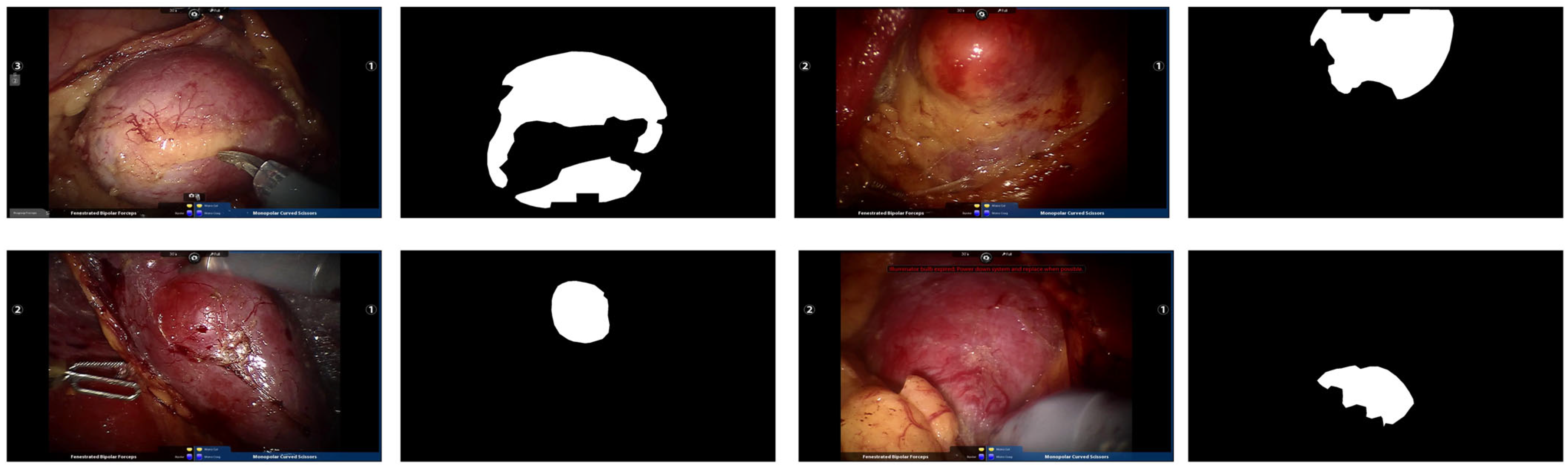

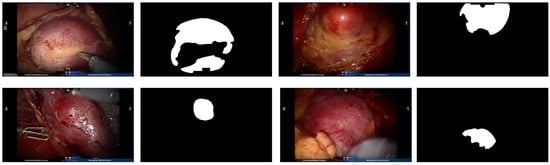

A total of 2823 valid frames were extracted. Keyframe selection and pixel-level annotation were performed independently by two board-certified urologists (>10 years of experience) using ITK-SNAP. To ensure labeling consistency, a third senior surgeon arbitrated discordant regions. Figure 5 presents representative examples of original endoscopic images alongside their manual annotations. With a training-to-test ratio of 8:2, the randomly partitioned dataset contains 2258 images for model training and 565 for testing.

Figure 5.

Example endoscopic images of kidney tumors from the Re-TMRS dataset and their corresponding pixel-level segmentation masks.

To guarantee comparability, the datasets and their split for polyp segmentation were kept consistent with previous work [28,33,48,55]. Specifically, we employed the Kvasir-SEG (1000 images with masks), CVC-ClinicDB (612 images with masks), CVC-ColonDB (380 images with masks), ETIS (192 images with masks), and the CVC-T subset from EndoScene (60 images with masks). The training set was constructed from 900 images of Kvasir-SEG and 550 of CVC-ClinicDB, while the remaining 798 images were allocated to the test set. A detailed breakdown of the datasets is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

The endoscopic datasets used in our experiments.

4.2. Evaluation Metrics

4.2.1. Experimental Set-Up and Evaluation Metrics

The BEMF-Net was developed with the PyTorch 1.7.0 framework on an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3090 GPU. All input images were resized to 352 × 352 pixels. For training, we utilized the Adam optimizer (initial learning rate: 10−4, decay rate: 0.1) over 100 epochs, training with batches of 8 images. To improve generalization, multi-scale training (scaling factors: {0.75, 1.0, 1.25}) and data augmentation—including color jittering, rotations within ±15°, and random horizontal flips—were employed. Gradient clipping was applied with a threshold of 0.5 to ensure training stability.

Our evaluation encompasses five metrics. The mean Dice (mDice) and mean IoU (mIoU) quantify regional segmentation similarity, with higher scores being better. The Mean Absolute Error (MAE) measures pixel-level deviation, where lower values indicate higher accuracy. The weighted F-measure () is derived from a weighted harmonic mean of precision and recall, and is also a higher-is-better metric. Finally, the Hausdorff Distance (HD) assesses boundary precision, with smaller distances preferred. The full kidney tumor assessment uses all five metrics, while generalization to polyp datasets is evaluated using mDice, mIoU, and MAE. Formal definitions are as follows:

The symbols used above are defined accordingly: TP, TN, FP, and FN, respectively, indicate true positive, true negative, false positive, and false negative counts, with N being the test image count. In Equation (16), P and Y are the predicted map and ground truth, while W and H denote width and height. Equation (17) employs β as a balancing parameter, and and represent the weighted precision and recall. For the Hausdorff Distance in Equation (18), A and B are the ground truth and predicted boundary sets, and is defined as a chosen distance metric (e.g., Euclidean).

In addition to the aforementioned metrics, we employ the non-parametric Wilcoxon signed-rank test [56] on the per-image Dice scores to determine whether the superiority of our method over the best-performing baselines is statistically significant. The resulting p-value quantifies the probability of observing such a difference if no true difference existed (the null hypothesis). A p-value below the conventional threshold (e.g., 0.05) leads to the rejection of the null hypothesis, indicating that the observed performance difference is statistically significant.

4.2.2. Quantitative Experiments

Our proposed BEMF-Net demonstrates superior performance on the Re-TMRS dataset, outperforming the eleven benchmark methods across all evaluation metrics, as quantitatively summarized in Table 2. Specifically, it records an mIoU of 85.7% and an mDice of 91.2%. In the table, the best result for each metric is indicated in bold for clarity. Specifically, on the mDice and mIoU metrics, it outperformed the second-best GSNet by 0.3% and 1.9%, respectively, while also achieving a 0.1% improvement in . This demonstrates that BEMF-Net can more effectively distinguish renal tumors from normal tissue backgrounds. Compared to the second-best method GSNet, a reduction of 0.1% in MAE and 0.9% in HD was observed for BEMF-Net. The quantitative reduction in HD attests to BEMF-Net’s enhanced accuracy in boundary localization for renal tumors, concurrently minimizing overall segmentation error. Collectively, these results affirm that BEMF-Net is both effective and superior for the segmentation of renal tumors in endoscopic images. To verify the statistical significance of this observed improvement, a non-parametric Wilcoxon signed-rank test was conducted on the per-image Dice scores between BEMF-Net and the second-best method (GSNet) across the entire test set. The performance gain of BEMF-Net is statistically significant, as evidenced by a p-value of 0.018, which falls below the standard 0.05 significance level.

Table 2.

Experimental results of various methods on the Re-TMRS renal tumor dataset are presented. Bold values denote the best-performing results. indicates higher is better, indicates lower is better, and bold indicates the best-performing result.

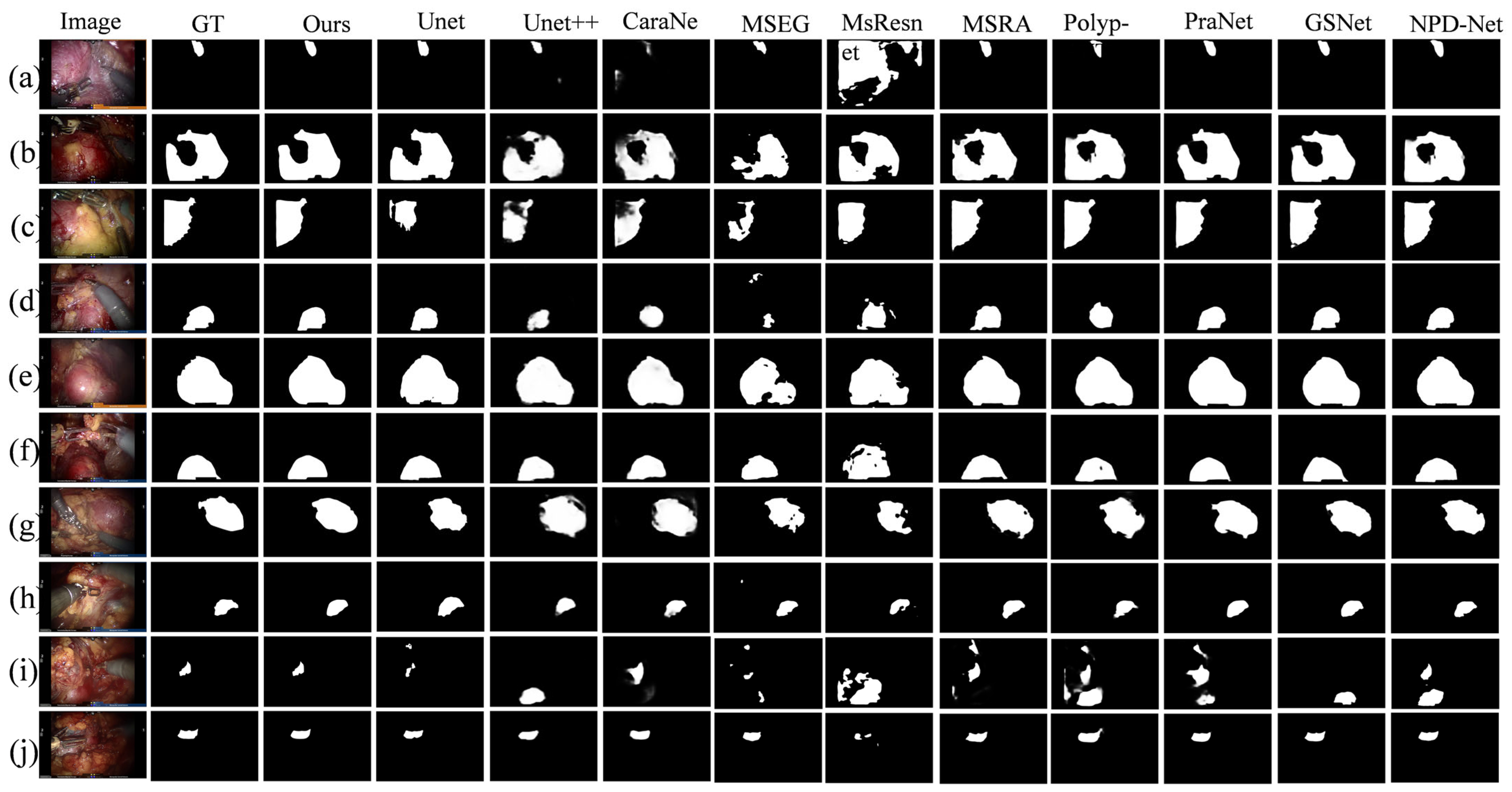

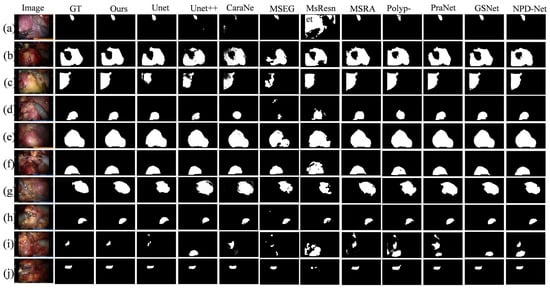

4.2.3. Qualitative Experiments

To intuitively demonstrate the advantages of BEMF-Net, Figure 6 provides a qualitative comparison against several leading methods, including UNet, UNet++, CaraNet, HarDNet-MSEG, Multi-scale-Resnet, MSRAformer, Polyp-PVT, PraNet, GSNet, and NPD-Net, on the renal tumor dataset. The figure is organized as follows: the first column shows the original image, the second column shows the ground truth, and the third column displays the segmentation result of our BEMF-Net. Columns 4 to 14 display segmentation results from various competing methods.

Figure 6.

A qualitative comparison between our BEMF-Net and other state-of-the-art methods on the Re-TMRS dataset. From left to right, they are the original image (a–j), the true value (GT), and our segmentation result, UNet, UNet++, CaraNet, HarDNet-MSEG, Multi-scale-Resnet, MSRAformer, Polyp-PVT, PraNet, GSNet, and NPD-Net.

The model demonstrates the capability to accurately identify and delineate the boundaries of unoccluded tumor regions, even in the presence of specular reflections or surgical tool occlusion. For Figure 6b,c,g, our proposed BEMF-Net possesses a significantly enhanced capability to detect fine boundary features, resulting in sharper tumor contours and cleaner backgrounds. This stems from the BSA module’s effective restoration of local boundary information, complemented by the HCA module’s recovery of image detail, thereby mitigating noise and extraneous data. Compared to other benchmark algorithms, the proposed BSA module empowers the network to dynamically adjust to lesions at various scales, allowing it to accommodate variations in tumor size and shape. In both Figure 6h (small tumor) and 6i (multiple tumors), BEMF-Net faithfully captures the tumor morphology, showing high agreement with the ground truth even in these challenging cases. This advantage over comparative algorithms stems from the proposed MFA module, which enhances the network’s multiscale adaptability to lesions, accommodating diverse renal tumor sizes and morphologies. Qualitative visual comparisons demonstrate BEMF-Net’s superior handling of challenges posed by irregular tumor shapes and sizes with indistinct boundaries. It achieves more precise tumor segmentation without blurred edges, missed detections, misclassifications, or severe deformations.

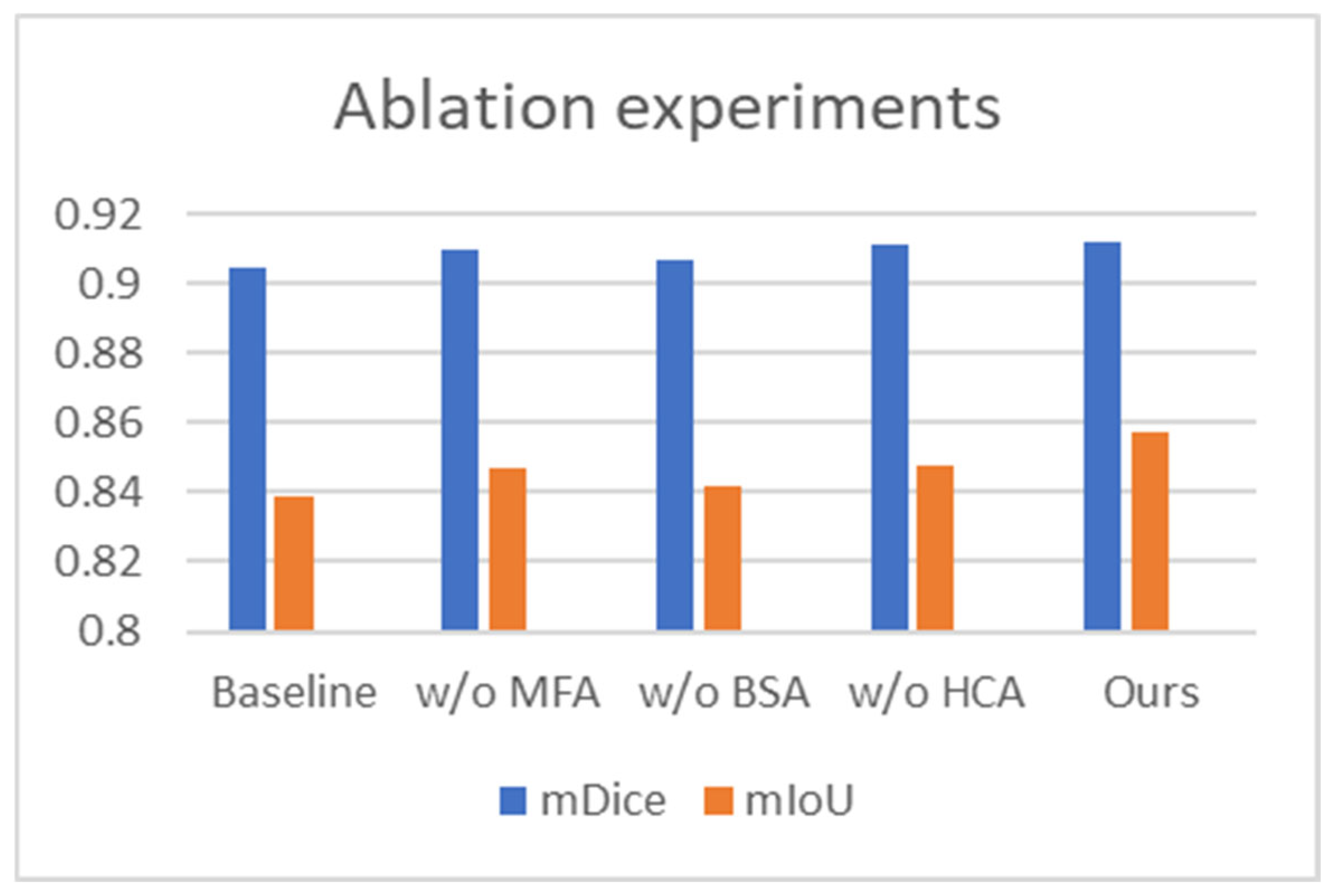

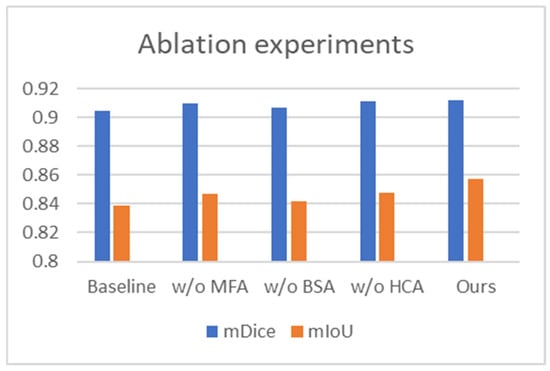

4.2.4. Ablation Experiments

To assess the individual impact of each proposed module, we carried out systematic ablation studies on the renal tumor endoscopic dataset. The experiments focused on the BSA, MFA, and HCA modules. Our baseline model is built on PVTv2 with a static segmentation head. The full model, termed the standard model, integrates all three modules (Baseline + MFA + BSA + HCA). We evaluated module efficacy by systematically removing each one from the standard configuration. The variants are denoted as “w/o MFA”, “w/o BSA”, and “w/o HCA”, respectively.

To assess the MFA module’s effectiveness, we omitted it from BEMF-Net, performing direct multi-scale fusion on backbone features. As shown in Table 3, this ablation led to reductions of 0.2% in mDice and 1% in mIoU, alongside an increase of 0.218 in HD, compared to the full model. These declines suggest that the encoder’s raw features lack the adaptability to tumor shape and size variations that the MFA-processed features possess, confirming the module’s critical role in enhancing multi-scale fusion.

Table 3.

An ablation study comparing the proposed modules on the Re-TMRS dataset. indicates higher is better, indicates lower is better, and bold indicates the best-performing result.

Similarly, to evaluate the BSA module, we trained an ablated model (“w/o BSA”) by completely removing this module. As shown in Table 3, compared to the full BEMF-Net, this variant exhibited clear performance deterioration across most metrics. The mDice and mIou of the model lacking the BSA module decreased by 0.5% and 1.5% respectively, while HD increased by 0.273. This demonstrates that the BSA module significantly enhances segmentation boundary continuity by capturing lesion boundary details, thereby reducing geometric errors caused by boundary discontinuities. This confirms that the BSA module is essential for boosting the model’s overall segmentation capability.

To investigate the specific role of the HCA module, we constructed an ablated model (“w/o HCA”) by replacing it with a standard deconvolution module and accordingly restructuring the decoder to ensure architectural parity. The results in Table 3 indicate a performance decline relative to the full model, with mDice and mIoU decreasing by 0.1% and 0.9%, respectively, and HD increasing by 0.227. This demonstrates that the HCA module resolves semantic misalignment issues and restores local image details, thereby resulting in enhanced segmentation.

The results of the ablation experiments are visualized in Figure 7 (bar charts for mDice/mIoU) and quantified in Table 3. Together, they clearly show that the removal of any proposed module (MFA, BSA, or HCA) is invariably detrimental to segmentation performance on the Re-TMRS dataset, validating each one’s contribution. Furthermore, all three ablated variants still outperform the baseline, underscoring the synergistic effect achieved by the modules when integrated.

Figure 7.

Comparative results of the ablation study for BEMF-Net on the Re-TMRS dataset.

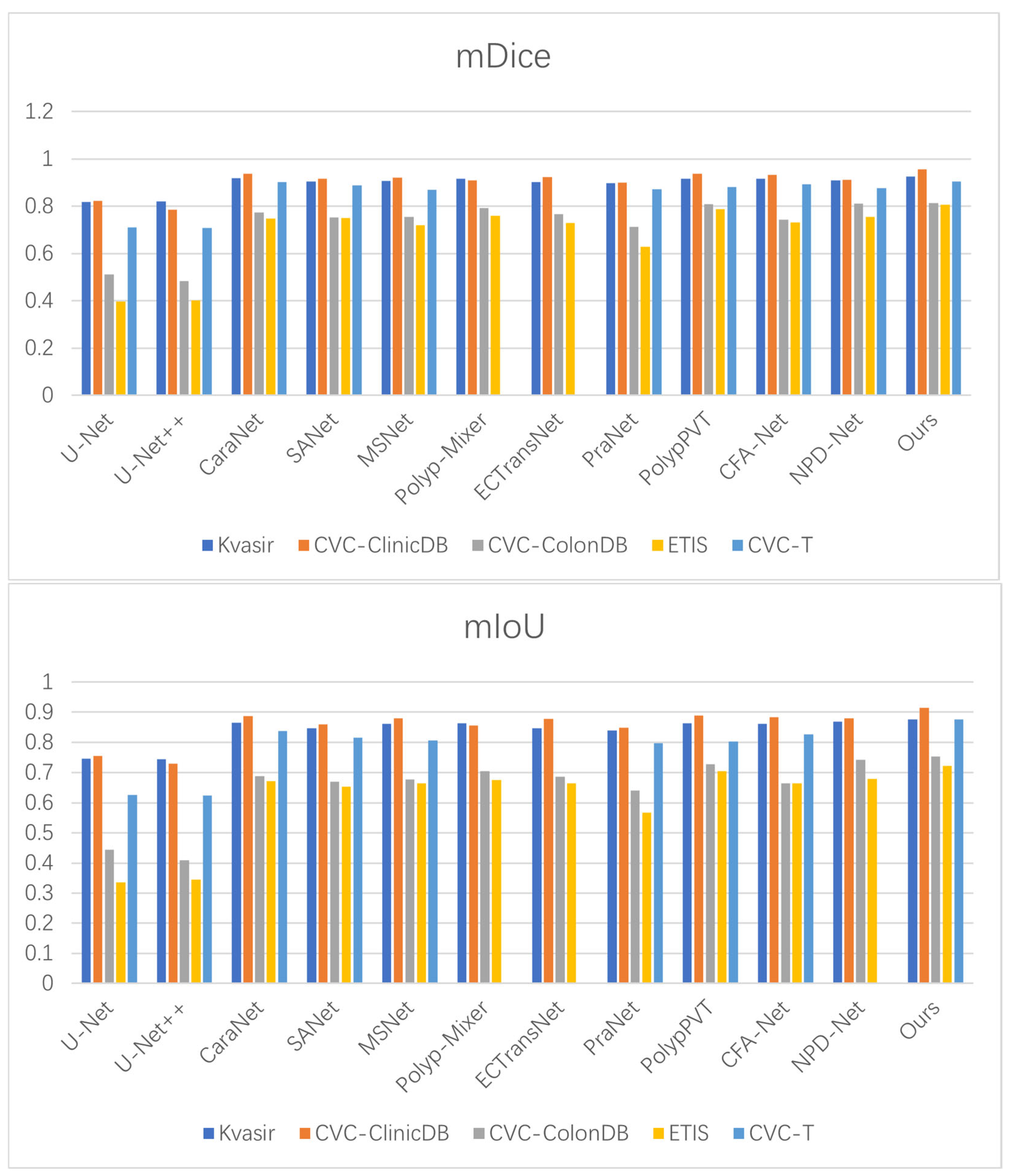

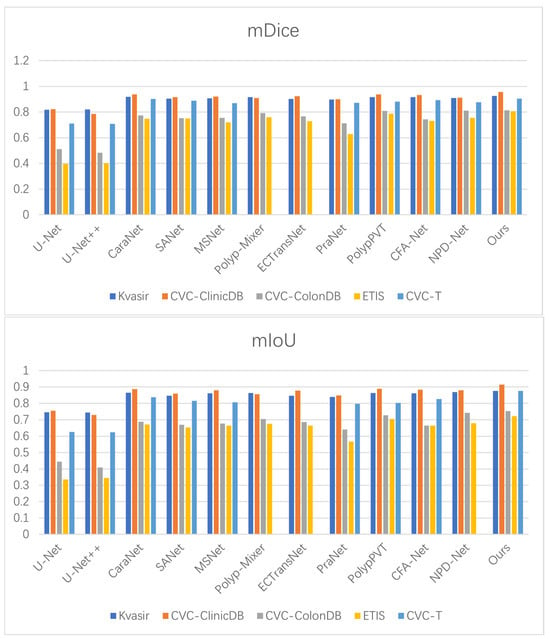

4.2.5. Generalization Experiments

To evaluate the generalization capability of BEMF-Net, we evaluated it on public polyp datasets and benchmarked it against eleven state-of-the-art methods [27,33,57,58,59,60]. The quantitative results (Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6) demonstrate that our method achieves superior performance on most metrics, confirming its robust cross-dataset generalization. For instance, on the Kvasir-SEG dataset (Table 4), BEMF-Net outperforms the second-best method (CARANet) by 0.7% in mDice and 1.1% in mIoU. On the CVC-ClinicDB colonoscopy dataset, our mDice and mIoU results exceeded the second-ranked PolypPVT by 1.8% and 2.6%, respectively. As depicted in Table 5, on the CVC-ColonDB dataset, our mDice and mIoU scores surpassed the second-ranked NPD-Net by 0.3% and 1.1%, respectively. On the ETIS dataset, our mDice and mIoU scores exceeded the second-ranked PolypPVT by 1.8% and 1.6%, respectively. As depicted in Table 6, on the CVC-T imaging dataset, our mDice and mIoU scores surpassed the second-ranked CARANet by 0.1% and 3.8%, respectively. These results indicate that BEMF-Net exhibits superior generalization capabilities across polyp datasets compared to other models. A Wilcoxon signed-rank test was conducted to ascertain the statistical significance of the observed cross-dataset improvements, based on a per-image Dice score comparison between BEMF-Net and the second-best method for each polyp dataset (CaraNet for Kvasir-SEG and CVC-T, PolypPVT for CVC-ClinicDB and ETIS, NPD-Net for CVC-ColonDB). The resulting p-values were all below the 0.05 significance threshold, with those for Kvasir-SEG, CVC-ClinicDB, and CVC-T reaching p < 0.01, thereby confirming that the performance advantages are statistically significant. Figure 8 visually compares the mDice and mIoU scores across five polyp datasets, where our method ranks first, demonstrating its superior performance against other algorithms.

Table 4.

Experimental results on the Kvasir and CVC-ClinicDB datasets; “——” indicates unavailable data. indicates higher is better, indicates lower is better, and bold indicates the best-performing result.

Table 5.

Experimental results on the CVC-ColonDB and ETIS datasets; “——” indicates unavailable data. indicates higher is better, indicates lower is better, and bold indicates the best-performing result.

Table 6.

Experimental results on the CVC-T dataset, with optimal results in bold. indicates higher is better, indicates lower is better, and bold indicates the best-performing result.

Figure 8.

Benchmarking of mDice and mIoU against state-of-the-art methods on five polyp datasets.

4.2.6. Computational Efficiency

We assessed the model complexity of BEMF-Net by calculating its number of trainable parameters (Params) and floating-point operations (FLOPs). Under uniform experimental conditions, a 3 × 352 × 352 tensor simulated a single renal tumor input. As summarized in Table 7, BEMF-Net, PolypPVT, and HSNet employ the same backbone network. Although the Params and FLOPs of BEMF-Net are slightly higher than those of PolypPVT and HSNet, its segmentation accuracy is the highest. BEMF-Net achieves a more favorable balance, demonstrating superior segmentation performance alongside a reduction in parameters compared to GSNet. This indicates that BEMF-Net achieves the optimal balance between excellent segmentation results and computational efficiency, fully demonstrating its high performance and superiority.

Table 7.

Computational complexity comparison with the current popular methods. indicates higher is better, indicates lower is better, and bold indicates the best-performing result.

In biomedical image segmentation, prioritizing higher accuracy under a constrained parameter budget is a key design consideration.

5. Discussion

This work introduces BEMF-Net, a boundary-enhanced multi-scale feature fusion network for segmenting renal tumors from endoscopic images. The model is designed to address three persistent challenges in this domain: ambiguous tumor boundaries, multi-scale variations in tumor morphology, and the similar appearance of tumor and adjacent tissue.

5.1. Effectiveness

Empirical evidence from our evaluations shows that BEMF-Net delivers top-tier performance, ranking it among the state-of-the-art on the Re-TMRS dataset. Consistent improvements in parameters such as mDice and mIoU indicate that this model can segment tumor areas more accurately. This performance stems from the synergistic design of its core modules: the MFA module effectively captures and fuses features across scales, enhancing the model’s adaptability to varying tumor sizes; the BSA module explicitly focuses on boundary regions, refining localization in areas of low contrast; and the HCA module effectively mitigates the disconnect between high-level semantic context and low-level spatial details. Ablation studies confirm the complementary contribution of each component. Furthermore, BEMF-Net’s strong performance on multiple public polyp segmentation datasets underscores its robust generalization capability, suggesting that the proposed architectural innovations are broadly applicable to endoscopic image analysis tasks beyond renal oncology.

5.2. Limitations

While the findings are encouraging, it is important to note several limitations. First, the Re-TMRS dataset, while clinically valuable, is relatively limited in scale (10 patients, 2823 images) and originates from a single institution. This potential limitation could constrain the model’s reliability in cross-center applications, where differences in surgical protocols, endoscopic equipment, and patient demographics are prevalent. Future work will involve multi-center collaborations to build larger, more diverse datasets and explore techniques like semi-supervised learning to leverage unlabeled data. Second, although BEMF-Net handles common artifacts well, we observed performance degradation in particularly challenging scenarios, such as cases with extreme specular reflections that completely saturate the tumor surface, active bleeding that occludes the region of interest, or very small tumors (<5 mm) with minimal boundary cues. In such instances, the model may produce fragmented segmentations. This highlights a fundamental constraint of vision-based methods and suggests the potential utility of integrating multi-modal intraoperative data in future systems. Third, regarding computational efficiency, while BEMF-Net maintains a reasonable parameter count compared to other high-performing models (Table 7), its suitability for real-time, low-latency inference on embedded surgical systems requires further validation. Developing a lightweight variant without significant accuracy loss is an important direction for clinical translation.

In conclusion, BEMF-Net provides an effective and generalizable framework for renal tumor segmentation in endoscopic images. By integrating targeted mechanisms for boundary enhancement, multi-scale fusion, and cross-modal feature alignment, it addresses key difficulties inherent in surgical vision. The acknowledged limitations clearly chart a path for future research, focusing on data scalability, robustness in edge cases, and clinical deployment efficiency. This work contributes a step toward more precise and automated intraoperative navigation in minimally invasive kidney surgery.

6. Conclusions

This work focuses on three core challenges in endoscopic renal tumor segmentation, namely blurred boundaries, multi-scale variations, and high tissue similarity. We introduce BEMF-Net, a Boundary-enhanced Multi-scale Feature Fusion Network. The framework employs a decomposed design strategy, integrating three dedicated modules: the Boundary-Selective Attention (BSA) module to enhance edge features, the Multi-scale Feature Fusion Attention (MFA) module to adapt to tumors of varying sizes, and the Hybrid Cross-modal Attention (HCA) module to synergistically utilize local details and global semantics. This design systematically tackles the aforementioned segmentation difficulties.

The experimental data provide strong evidence that our method surpasses existing mainstream algorithms on the endoscopic renal tumor dataset Re-TMRS by delivering more accurate segmentations with sharper boundaries, as confirmed by both visual and quantitative metrics. Furthermore, validated on multiple public polyp datasets, the framework demonstrates strong generalization, underscoring the versatility and transferability of its design for similar medical image segmentation challenges.

This work not only improves the accuracy of automated tumor region segmentation in endoscopic images, aiding in intraoperative real-time localization and navigation, but also further validates the effectiveness of the collaborative multi-module and feature-decoupling approach in complex medical image analysis. Future research will focus on integrating interpretable decomposition mechanisms with end-to-end deep learning architectures and advancing their integration into lightweight, real-time clinical assistance systems, ultimately providing technical support for the development of intelligent surgical platforms.

Author Contributions

Methodology, J.Z.; software, C.X.; validation, C.X. and J.Z.; resources, J.Z. and C.X.; data curation, Z.L.; writing—original draft preparation, J.Z.; writing—review and editing, C.X.; visualization, J.Z.; supervision, C.X.; project administration, C.X.; funding acquisition, C.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by The National Key Research and Development Program of China (No.2019YFC0117800).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author (accurately indicate status).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Dikshit, R.; Eser, S.; Mathers, C.; Rebelo, M.; Parkin, D.M.; Forman, D.; Bray, F. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: Sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int. J. Cancer 2015, 136, E359–E386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, X.; Li, X.; Shi, C.; Ren, H.; Mumtaz, I. Dual-Feature Fusion Attention Network for Small Object Segmentation. Comput. Biol. Med. 2023, 160, 107065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention—MICCAI 2015, 18th International Conference, Munich, Germany, 5–9 October 2015; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Siddiquee, M.M.R.; Tajbakhsh, N.; Liang, J. UNet++: A Nested U-Net Architecture for Medical Image Segmentation. In Deep Learning in Medical Image Analysis and Multimodal Learning for Clinical Decision Support, Proceedings of the 4th International Workshop, DLMIA 2018, and 8th International Workshop, ML-CDS 2018, Granada, Spain, 20 September 2018; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 11045, pp. 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Lian, S.; Luo, Z.; Li, S. Weighted res-UNet for high-quality retina vessel segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2018 9th International Conference on Information Technology in Medicine and Education (ITME), Hangzhou, China, 19–21 October 2018; pp. 327–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, D.; Smedsrud, P.H.; Riegler, M.A.; Johansen, D.; De Lange, T.; Halvorsen, P.; Johansen, H.D. Resunet++: An advanced architecture for medical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Symposium on Multimedia (ISM), San Diego, CA, USA, 9–11 December 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, D.; Riegler, M.A.; Johansen, D.; Halvorsen, P.; Johansen, H.D. DoubleU-Net: A deep convolutional neural network for medical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 33rd International Symposium on Computer-Based Medical Systems (CBMS), Rochester, MN, USA, 28–30 July 2020; pp. 558–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alom, M.Z.; Yakopcic, C.; Hasan, M.; Taha, T.M.; Asari, V.K. Recurrent Residual U-Net for Medical Image Segmentation. J. Med. Imaging 2019, 6, 014006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iglovikov, V.; Shvets, A. TernausNet: U-Net with VGG11 Encoder Pre-Trained on ImageNet for Image Segmentation. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1801.05746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An Image is Worth 16×16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.11929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Lu, Y.; Yu, Q.; Luo, X.; Adeli, E.; Wang, Y.; Lu, L.; Yuille, A.L.; Zhou, Y. TransUNet: Transformers make strong encoders for medical image segmentation. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2102.04306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Xie, E.; Li, X.; Fan, D.P.; Song, K.; Liang, D.; Lu, T.; Luo, P.; Shao, L. Pyramid Vision Transformer: A Versatile Backbone for Dense Prediction without Convolutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 568–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; pp. 6000–6010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Wei, Y.; Wang, X.; Liu, W.; Huang, T.S.; Shi, H. AlignSeg: Feature-Aligned Segmentation Networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2021, 44, 550–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzini, D. Guided Upsampling Network for Real-Time Semantic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the BMVC 2018: British Machine Vision Conference, Newcastle, UK, 3–6 September 2018; p. 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Peng, C.; Xue, X.; Sun, J. Exfuse: Enhancing Feature Fusion for Semantic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, D.L.; Xu, C.; Prince, J.L. Current methods in medical image segmentation. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2000, 2, 315–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohle, R.; Toennies, K.D. A New Approach for Model-Based Adaptive Region Growing in Medical Image Analysis. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. 2001, 2124, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.T.; Lei, C.C.; Hung, S.W. Computer-aided kidney segmentation on abdominal CT images. IEEE Trans. Inf. Technol. Biomed. 2006, 10, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, H.; Chang, S.; Tao, C.; Wang, J.H.; Kaya, D.; Bae, K.T. Semiautomated segmentation of kidney from high-resolution multidetector computed tomography images using a graph-cuts technique. J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 2009, 33, 893–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caselles, V.; Kimmel, R.; Sapiro, G. Geodesic active contours. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 1997, 22, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman, R.; Kawashima, A.; Takahashi, N.; Silva, A.; Vrtiska, T.; Leng, S.; Fletcher, J.; McCollough, C. Applications of dual energy CT in urologic imaging: An update. Radiol. Clin. N. Am. 2012, 50, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grasso, M. Bladder cancer: A major public health issue. Eur. Urol. Suppl. 2008, 7, 510–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R.L.; Torre, L.A.; Jemal, A. GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 394–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, J.; Ni, J.; Elazab, A.; Wu, J. TA-Net: Triple Attention Network for Medical Image Segmentation. Comput. Biol. Med. 2021, 137, 104836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-C.; Papandreou, G.; Kokkinos, I.; Murphy, K.; Yuille, A.L. Deeplab: Semantic image segmentation with deep convolutional nets, atrous convolution, and fully connected CRFs. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2017, 40, 834–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, D.P.; Ji, G.P.; Zhou, T.; Chen, G.; Fu, H.; Shen, J.; Shao, L. PraNet: Parallel Reverse Attention Network for Polyp Segmentation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, Lima, Peru, 4–8 October 2020; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.H.; Wu, H.-Y.; Lin, Y.L. Hardnet-mseg: A simple encoder-decoder polyp segmentation neural network that achieves over 0.9 mean dice and 86 fps. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2101.07172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, A.; Guan, S.; Ko, H.; Loew, M.H. CaraNet: Context Axial Reverse Attention Network for Segmentation of Small Medical Objects. In Proceedings of the Medical Imaging 2022: Image Processing, San Diego, CA, USA, 20–24 February 2022; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2022; pp. 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zeng, G.; Li, F.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, H. FRBNet: Feedback refinement boundary network for semantic segmentation in breast ultrasound images. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2023, 86, 105194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin Transformer: Hierarchical Vision Transformer Using Shifted Windows. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, BC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 10012–10022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Xie, E.; Li, X.; Fan, D.P.; Song, K.; Liang, D.; Lu, T.; Luo, P.; Shao, L. PVT v2: Improved Baselines with Pyramid Vision Transformer. Comput. Vis. Media 2022, 8, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.; Wang, W.; Fan, D.P.; Li, J.; Fu, H.; Shao, L. Polyp-PVT: Polyp Segmentation with Pyramid Vision Transformers. CAAI Artif. Intell. Res. 2023, 2, 9150015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Long, C.; Li, S.; Yang, J.; Jiang, F.; Zhou, R. MSRAformer: Multiscale Spatial Reverse Attention Network for Polyp Segmentation. Comput. Biol. Med. 2022, 151, 106274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Cruz, L.B.; Araújo, J.D.L.; Ferreira, J.L.; Diniz, J.O.B.; Silva, A.C.; de Almeida, J.D.S.; de Paiva, A.C.; Gattass, M. Kidney segmentation from computed tomography images using deep neural network. Comput. Biol. Med. 2020, 123, 103906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Li, L.; Lian, S.; Chen, S.; Luo, Z. SERU: A cascaded SE-ResNeXT U-Net for kidney and tumor segmentation. Concurr. Comput. Pract. Exp. 2020, 32, e5738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geethanjali, T.M.; Dinesh, M.S. Semantic segmentation of tumors in kidneys using attention U-Net models. In Proceedings of the 2021 5th International Conference on Electrical, Electronics, Communication, Computer Technologies and Optimization Techniques (ICEECCOT), Mysuru, India, 14–15 December 2021; pp. 286–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, B.; Zhang, G.; Liu, H.; Qin, Y.; Chen, Y. DCCTNet: Kidney Tumors Segmentation Based On Dual-Level Combination Of CNN And Transformer. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 27–30 October 2024; pp. 3112–3116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Xie, C.; Li, F.; Wang, J.; Lv, C.; Xie, G.; Nan, Y. A triple-stage self-guided network for kidney tumor segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 17th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI), Iowa City, IA, USA, 3–7 April 2020; pp. 341–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Su, L.; Huang, Q. Cascaded Partial Decoder for Fast and Accurate Salient Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–21 June 2019; pp. 3907–3916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhojanapalli, S.; Chakrabarti, A.; Glasner, D.; Li, D.; Unterthiner, T.; Veit, A. Understanding robustness of transformers for image classification. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 10231–10241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Wang, X.; Wei, Y.; Huang, L.; Huang, T.S. CCNet: Criss-Cross Attention for Semantic Segmentation. arXiv 2020, arXiv:1811.11721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, A.; Loew, M. Cfpnet: Channel-wise Feature Pyramid for Real-time Semantic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Anchorage, AK, USA, 19–22 September 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, S.; Rastegari, M.; Caspi, A.; Shapiro, L.; Hajishirzi, H. ESPNet: Efficient Spatial Pyramid of Dilated Convolutions for Semantic Segmentation. Proc. ECCV 2018, 11212, 552–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Liu, F.; Fan, X.; Huang, D. Polarized Self-Attention: Towards High-quality Pixel-wise Regression. arXiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Wang, S.; Huang, Q. F3Net: Fusion, Feedback and Focus for Salient Object Detection. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, New York, NY, USA, 7–12 February 2020; pp. 12321–12328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.C.; Fu, C.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, F.Y.; Zhao, Y.L.; Sham, C.W. HSNet: A hybrid semantic network for polyp segmentation. Comput. Biol. Med. 2022, 150, 106173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, H.; Zhao, X.; Lv, L.; Zhang, L.; Sun, W.; Lu, H. Growth Simulation Network for Polyp Segmentation. In Proceedings of the Pattern Recognition and Computer Vision Conference, Xiamen, China, 13–15 October 2023; pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Zhao, L.; Liao, T.; Zhang, X.; Chen, G.; Xiao, G. A novel non-pretrained deep supervision network for polyp segmentation. Pattern Recognit. 2024, 154, 110554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, D.; Smedsrud, P.H.; Riegler, M.A.; Halvorsen, P.; de Lange, T.; Johansen, D.; Johansen, H.D. Kvasir-seg: A segmented polyp dataset. In Proceedings of the MultiMedia Modeling: 26th International Conference, MMM 2020, Daejeon, South Korea, 5–7 January 2020; pp. 451–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, J.; Sánchez, F.J.; Fernández-Esparrach, G.; Gil, D.; Rodríguez, C.; Vilariño, F. WM-DOVA maps for accurate polyp highlighting in colonoscopy: Validation vs. saliency maps from physicians. Comput. Med. Imaging Graph. 2015, 43, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajbakhsh, N.; Gurudu, S.R.; Liang, J. Automated Polyp Detection in Colonoscopy Videos Using Shape and Context Information. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2015, 35, 630–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, D.; Bernal, J.; Sánchez, F.J.; Fernández-Esparrach, G.; López, A.M.; Romero, A.; Drozdzal, M.; Courville, A. A benchmark for endoluminal scene segmentation of colonoscopy images. J. Healthc. Eng. 2017, 2017, 4037190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.; Histace, A.; Romain, O.; Dray, X.; Granado, B. Toward Embedded Detection of Polyps in WCE Images for Early Diagnosis of Colorectal Cancer. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 2013, 9, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, H.; Xu, C.; Nie, C.; Han, J.; Li, Y.; Liu, C. DBE-Net: Dual Boundary Guided Attention Exploration Network for Polyp Segmentation. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welsch, D.; Neuhäuser, M. Wilcoxon-Signed-Rank Test. In International Encyclopedia of Statistical Science; Lovric, M., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Fang, X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, E. Polyp Segmentation of Colonoscopy Images by Exploring the Uncertain Areas. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 52971–52981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.K.; Li, Z.G.; Li, C.Y.; Gao, H.Y. ECTransNet: An automatic polyp segmentation network based on multi-scale edge complementary. J. Digit. Imaging 2023, 36, 2427–2440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J.H.; Zhang, Q.; Tang, Y.H.; Zhang, Z.Q. Polyp-Mixer: An efficient context-aware MLP-based paradigm for polyp segmentation. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2023, 33, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Zhou, Y.; He, K.L.; Gong, C.; Yang, J.; Fu, H.Z.; Shen, D.Z. Cross-level Feature Aggregation Network for Polyp Segmentation. Pattern Recognit. 2023, 140, 109555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.