A Detection Method for Frequency-Hopping Signals in Complex Environments Using Time–Frequency Cancellation and the Hough Transform

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Signal Model and Time–Frequency Analysis

2.1. Signal Model

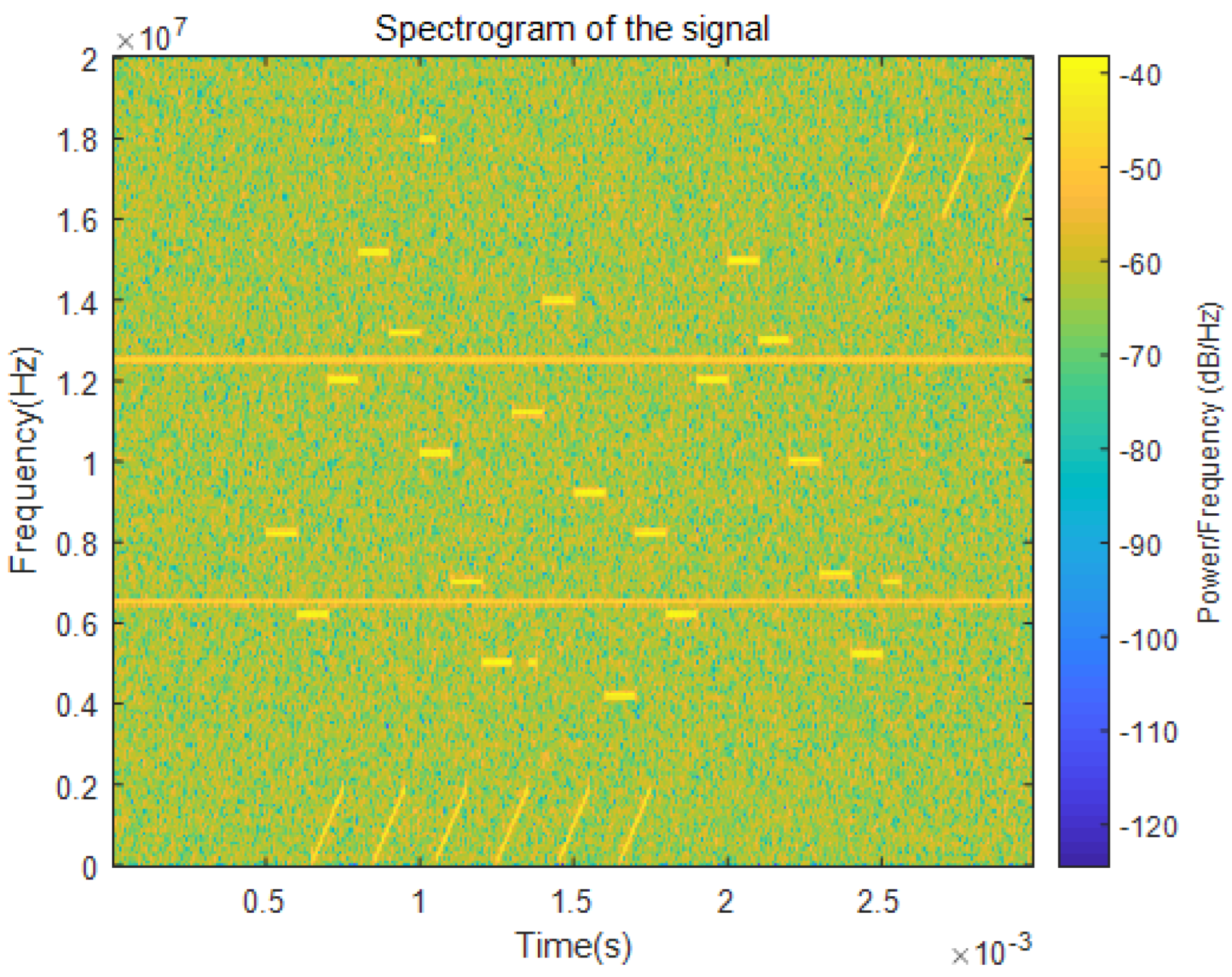

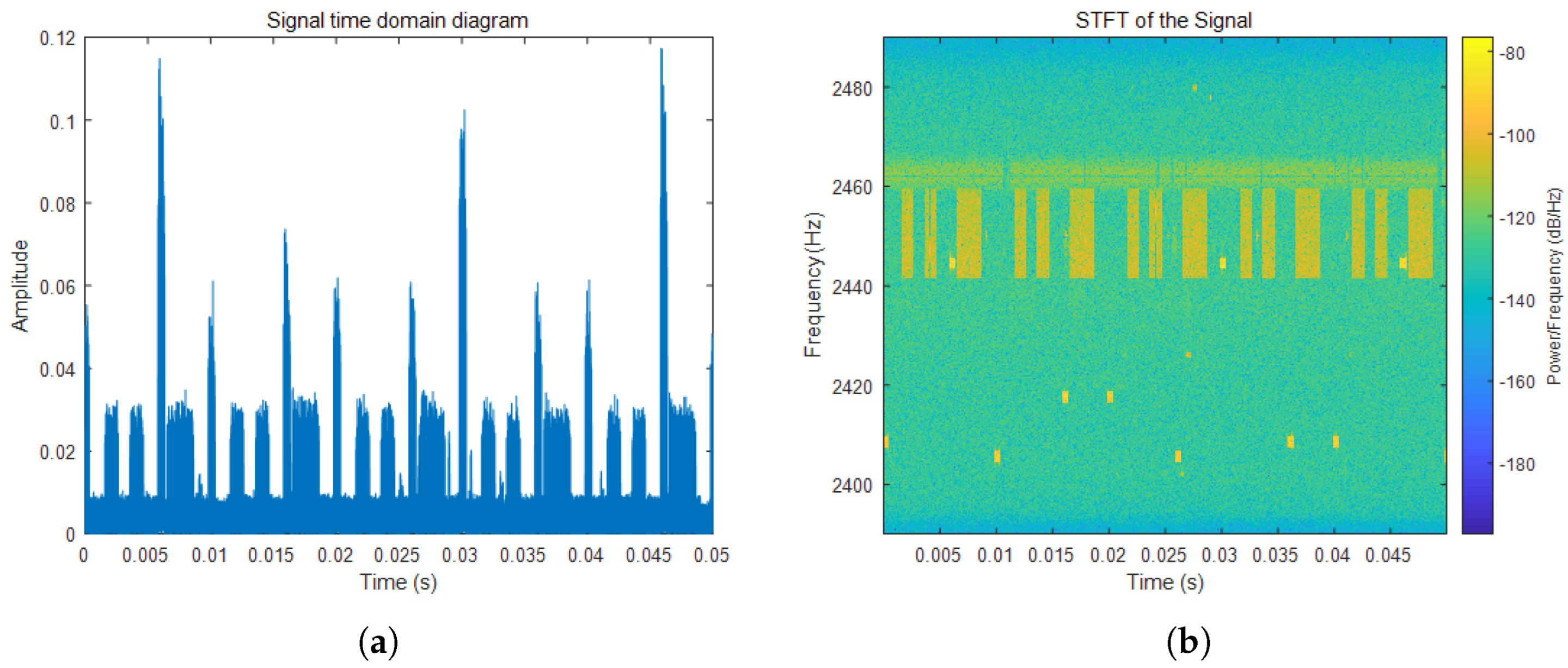

2.2. Signal Time–Frequency Analysis

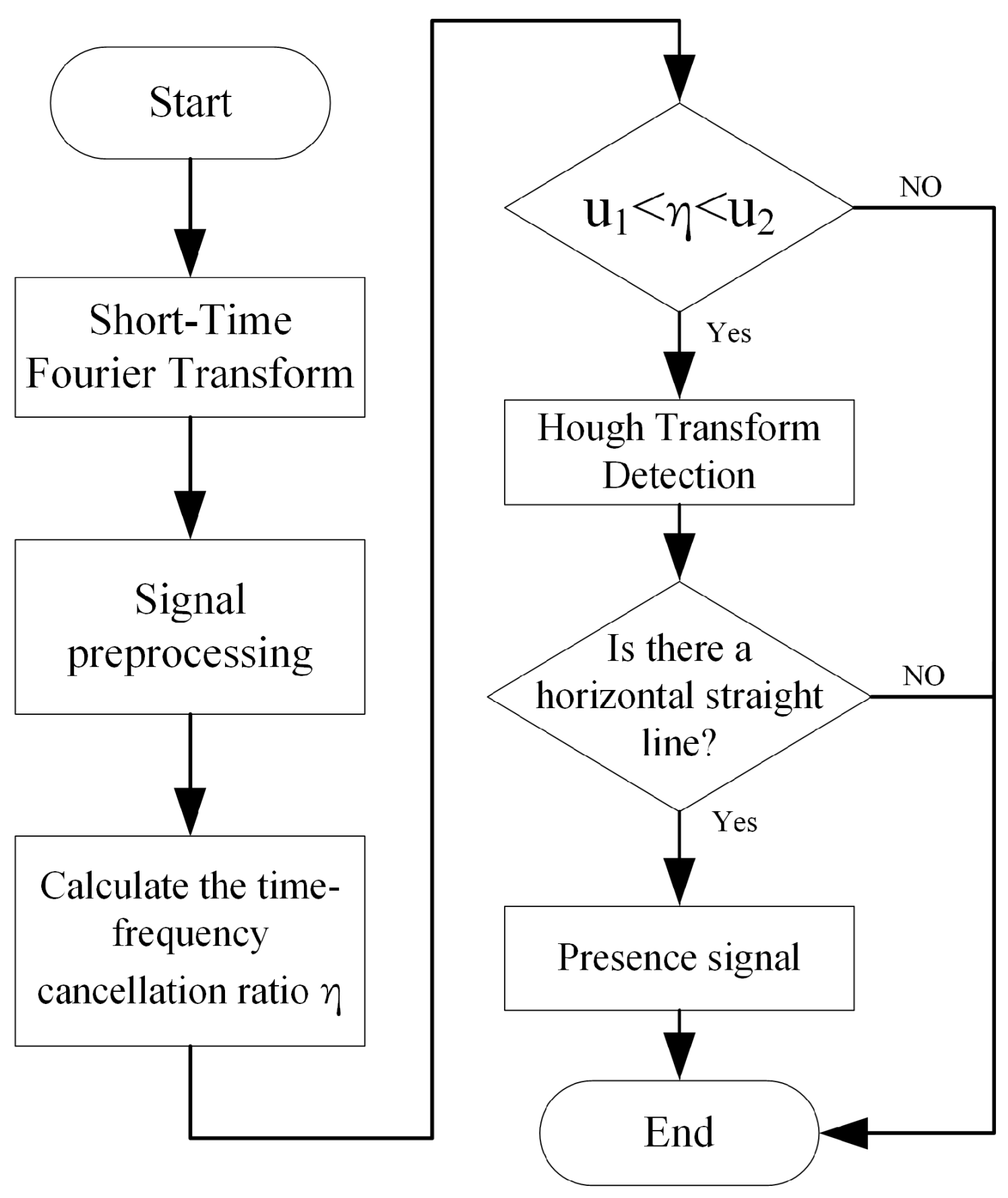

3. Frequency-Hopping Signal Detection Method

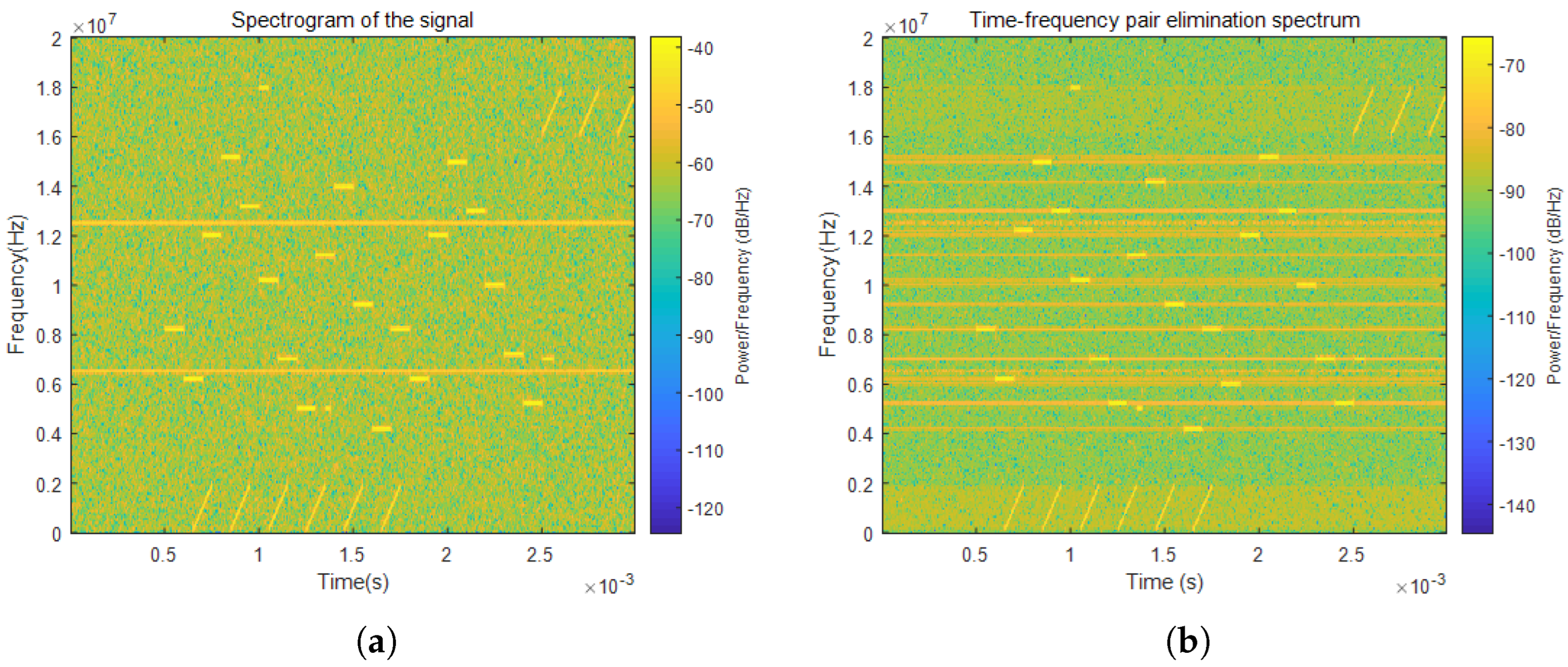

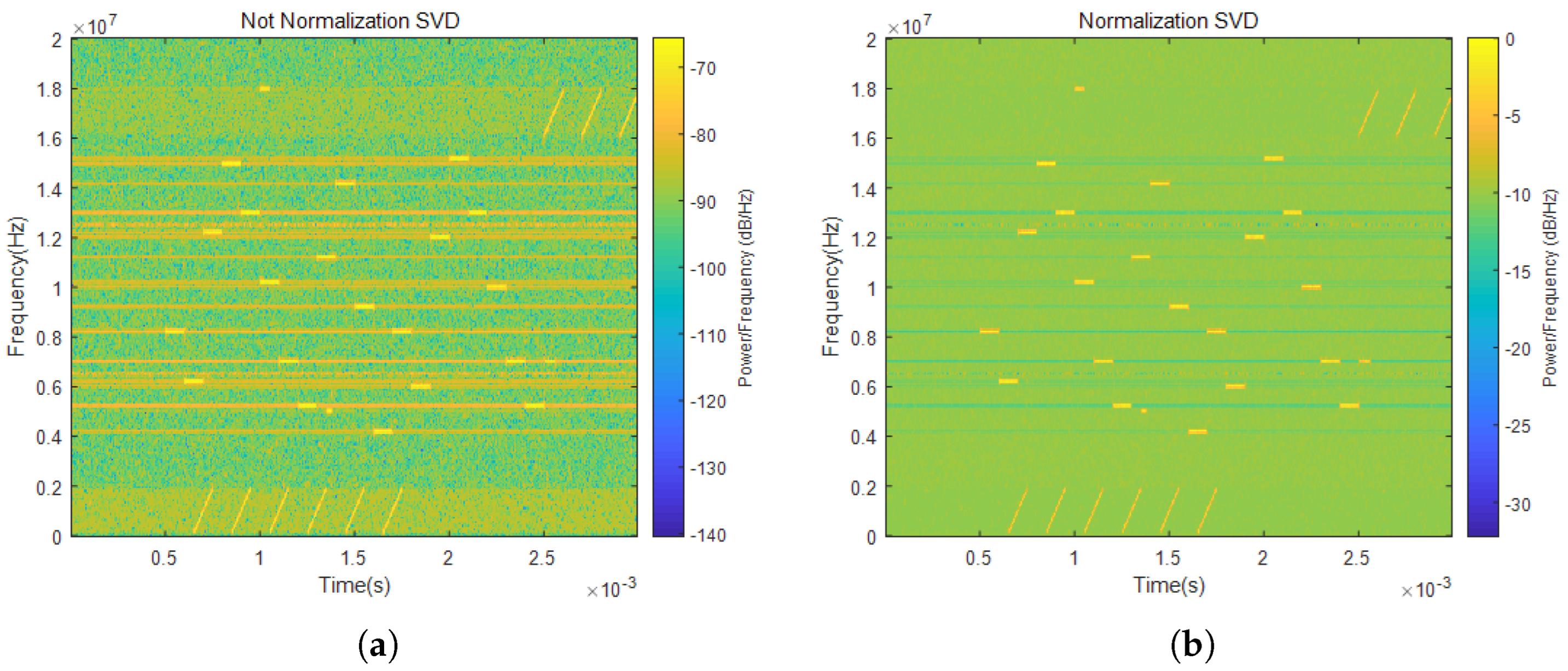

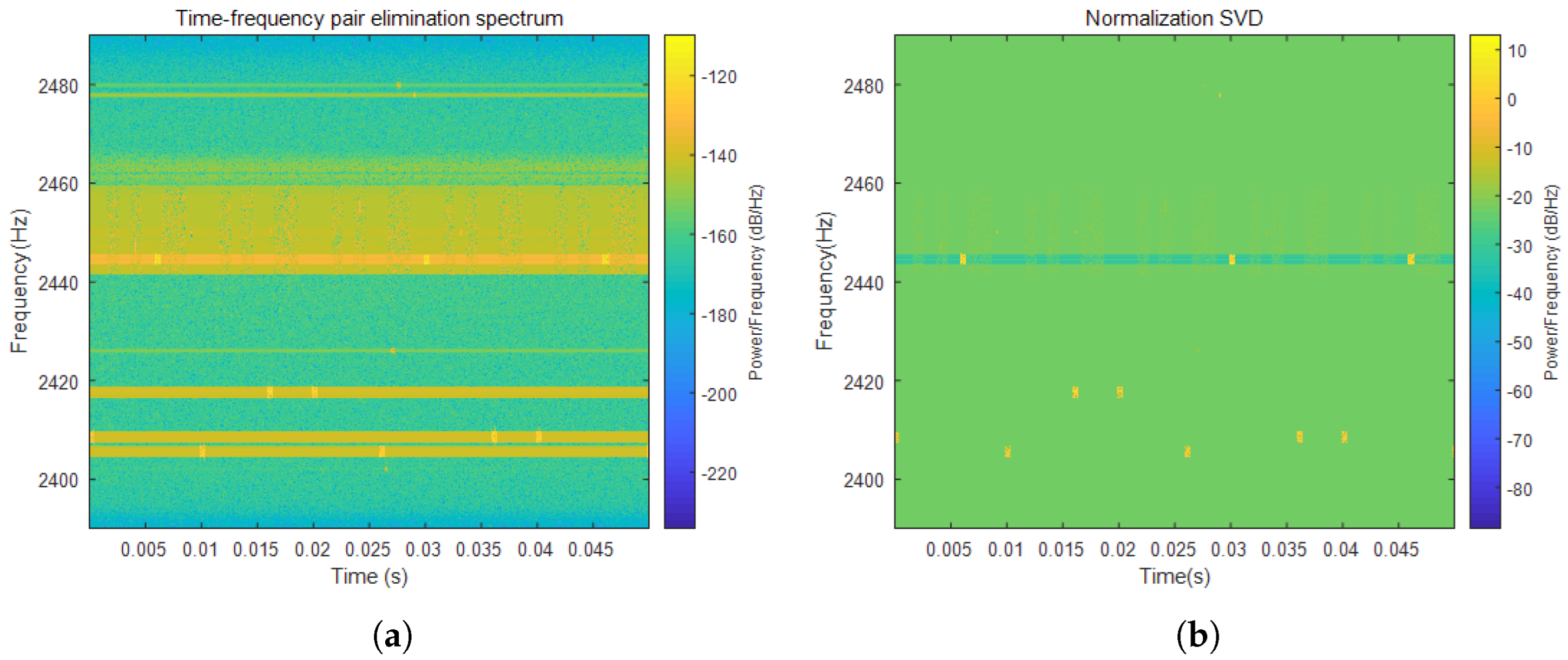

3.1. Signal Preprocessing

- (1)

- Time–frequency cancellation processing

- (2)

- Singular value decomposition for noise reduction.

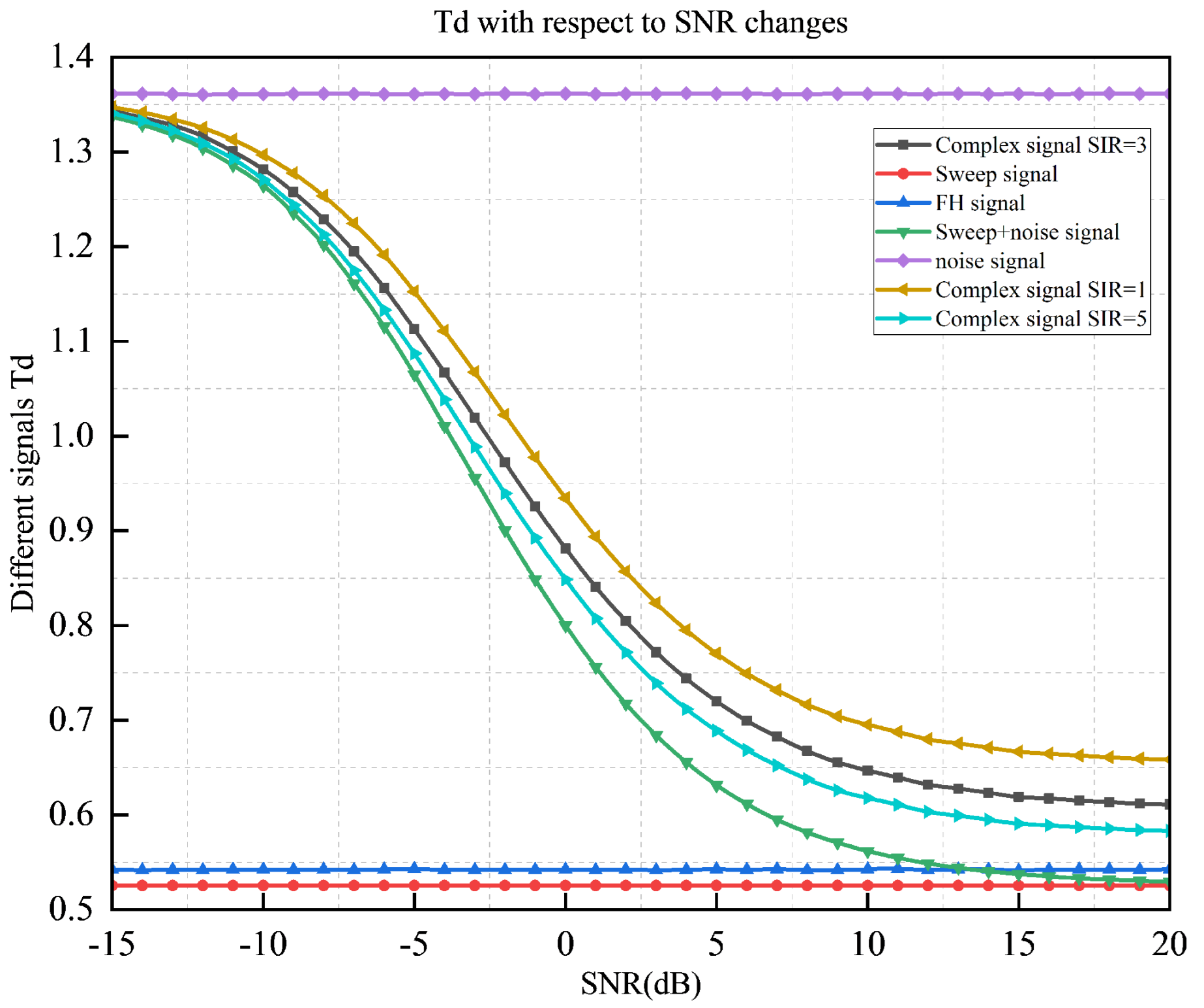

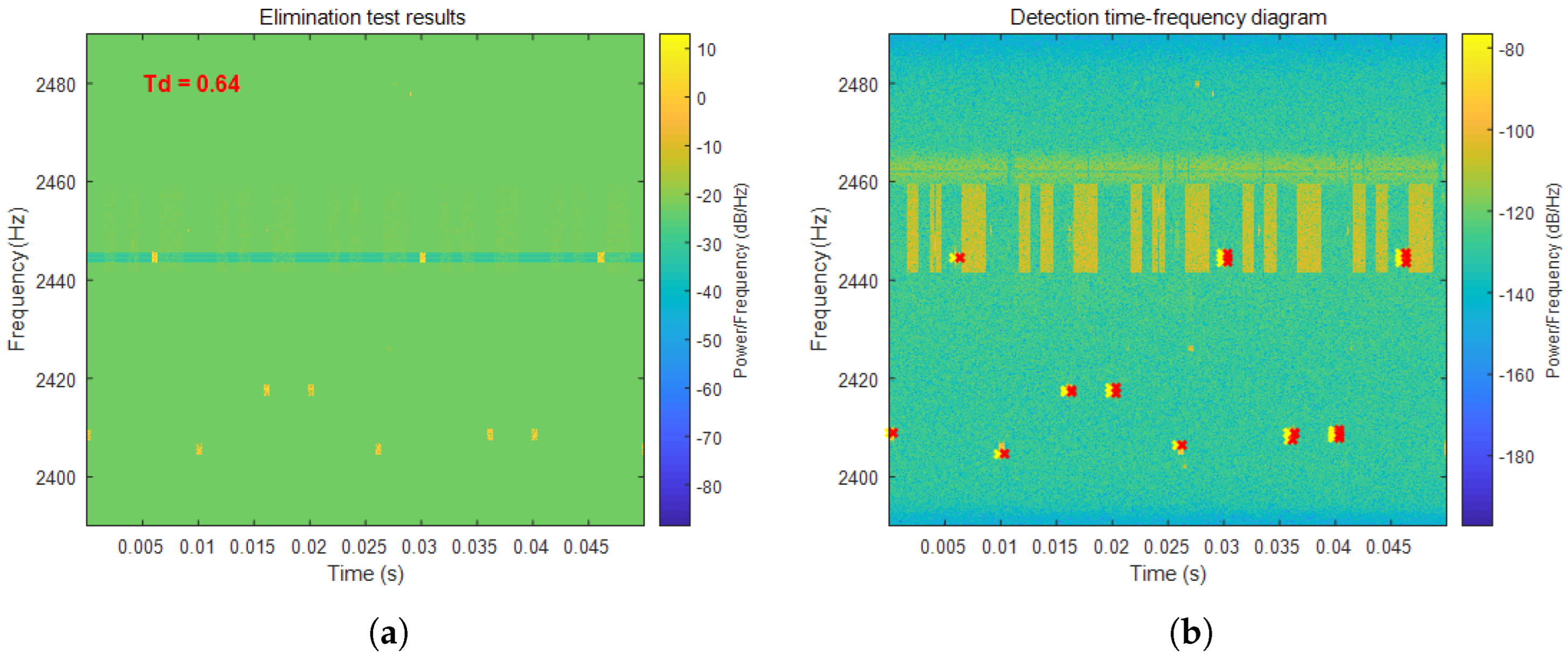

3.2. Signal Feature Analysis Based on Time–Frequency Cancellation

- (1)

- Time–frequency cancellation ratio of frequency-hopping signals

- (2)

- Time–frequency cancellation ratio of fixed-frequency signals

- (3)

- Time–frequency cancellation ratio of Gaussian white noise

- (4)

- Time–frequency cancellation ratio between impulse signals and swept-frequency signals

3.3. Frequency-Hopping Signal Detection Based on the Hough Transform

- Frequency-hopping signals appear as periodic horizontal segments.

- Swept-frequency signals exhibit diagonal traces due to linear frequency variation.

- Burst signals appear as randomly distributed short segments with limited temporal duration.

3.4. Algorithm Summary

3.5. Calculation Complexity Analysis

4. Experimental Results and Analysis

4.1. Data Preprocessing

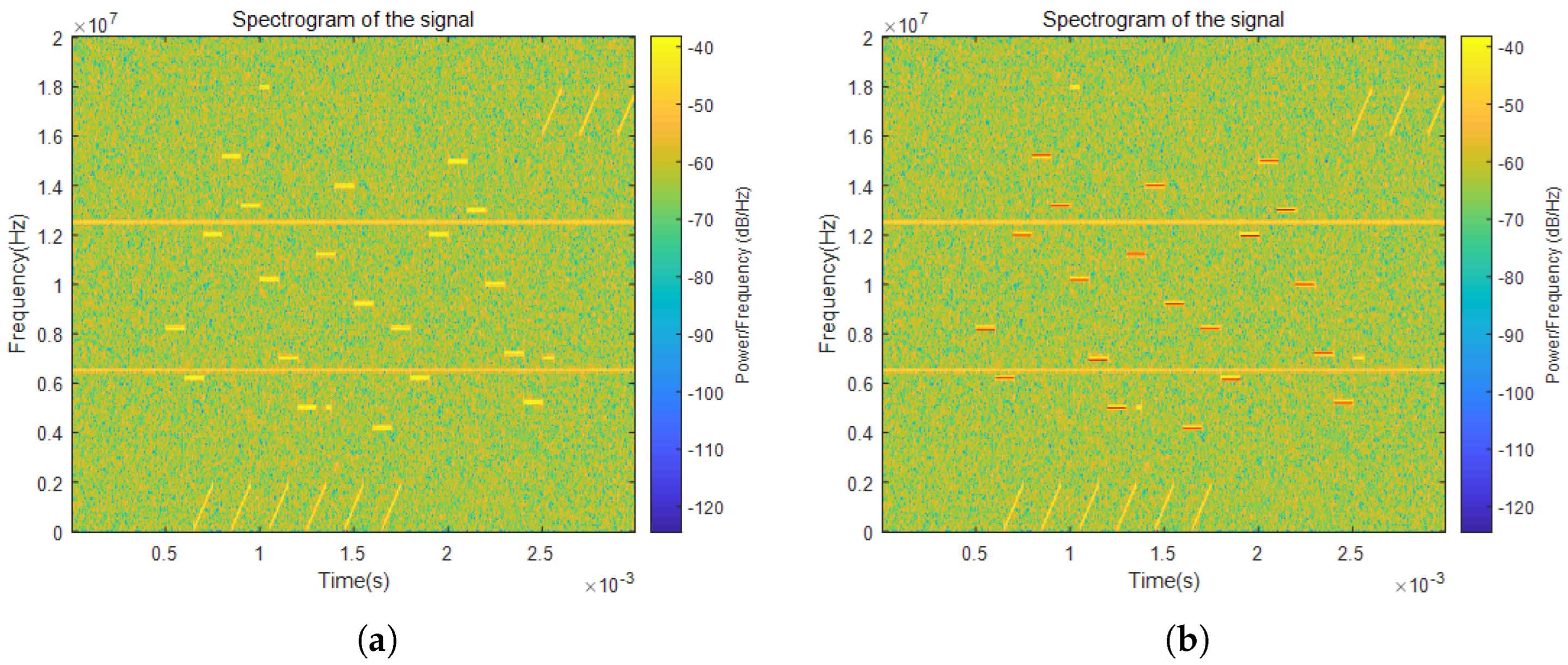

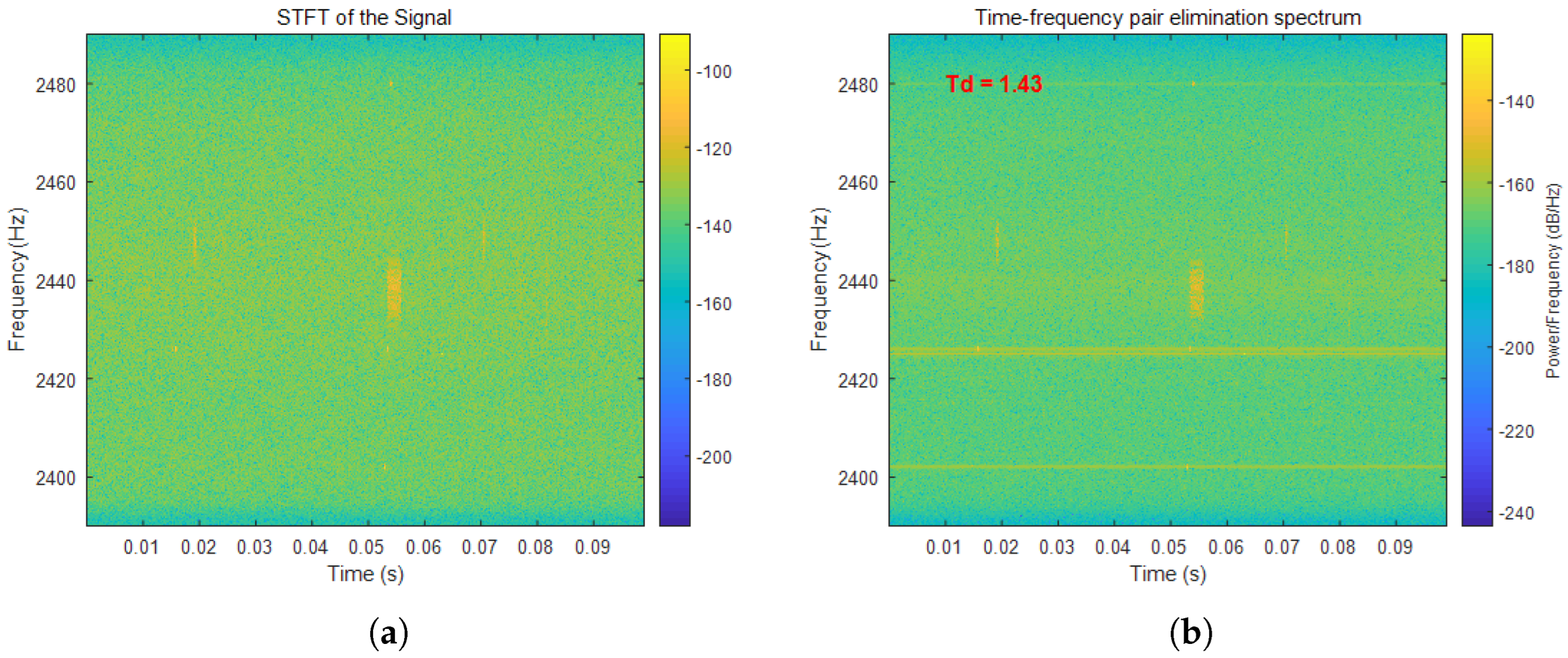

4.2. Analysis of Time–Frequency Cancellation Ratio and Hough Transform Results

4.3. Comparative Analysis of Algorithm Detection Performance

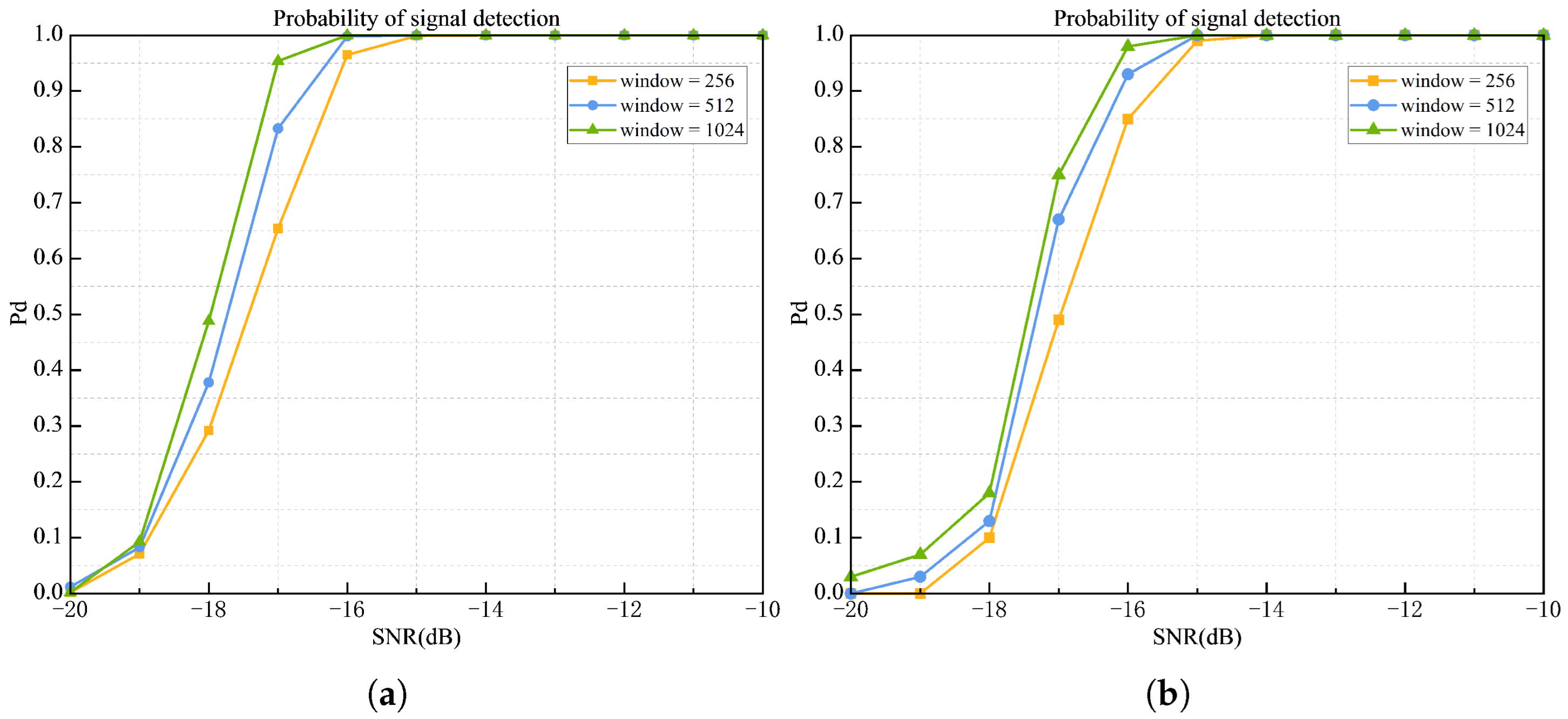

- (1)

- The effect of different STFT window lengths on detection performance

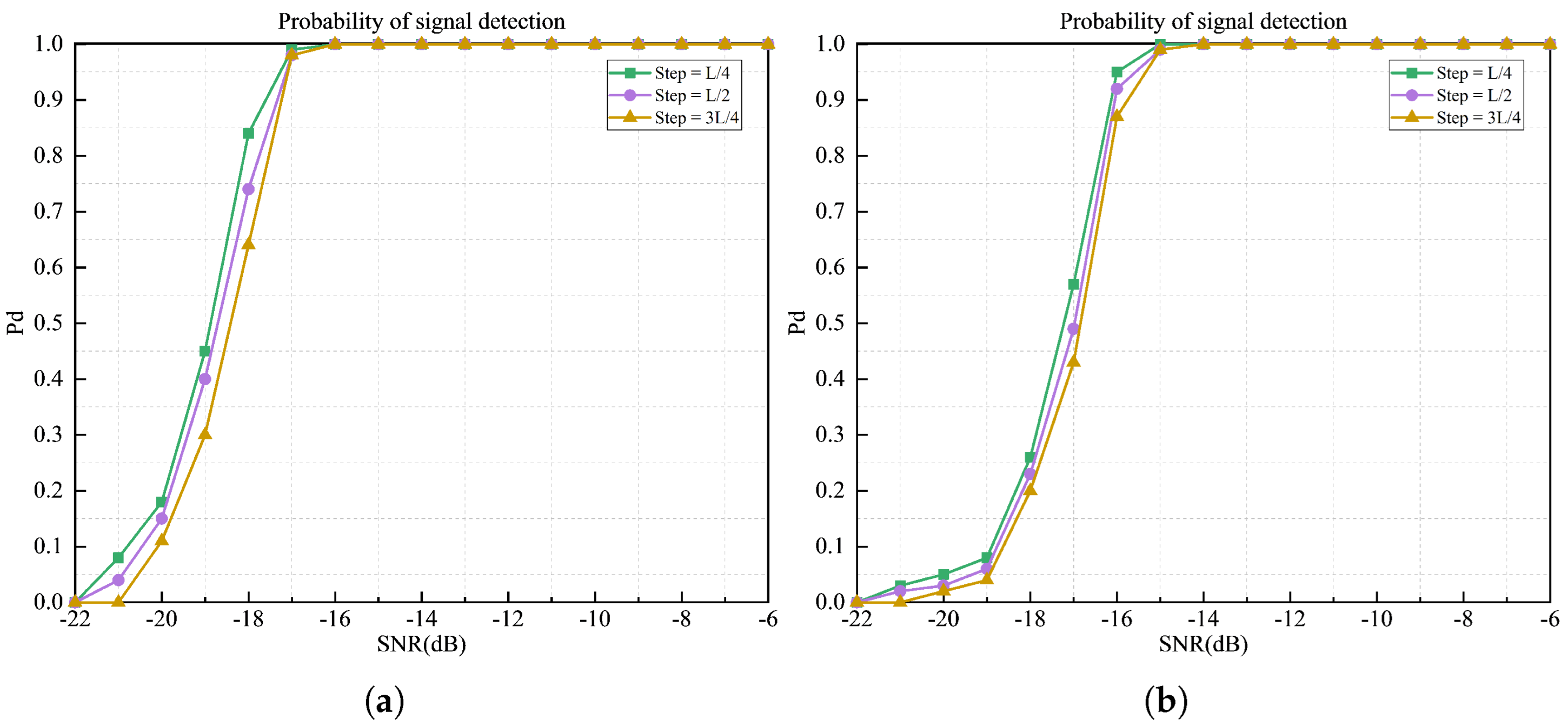

- (2)

- The effect of different STFT window sliding lengths on detection performance

- (3)

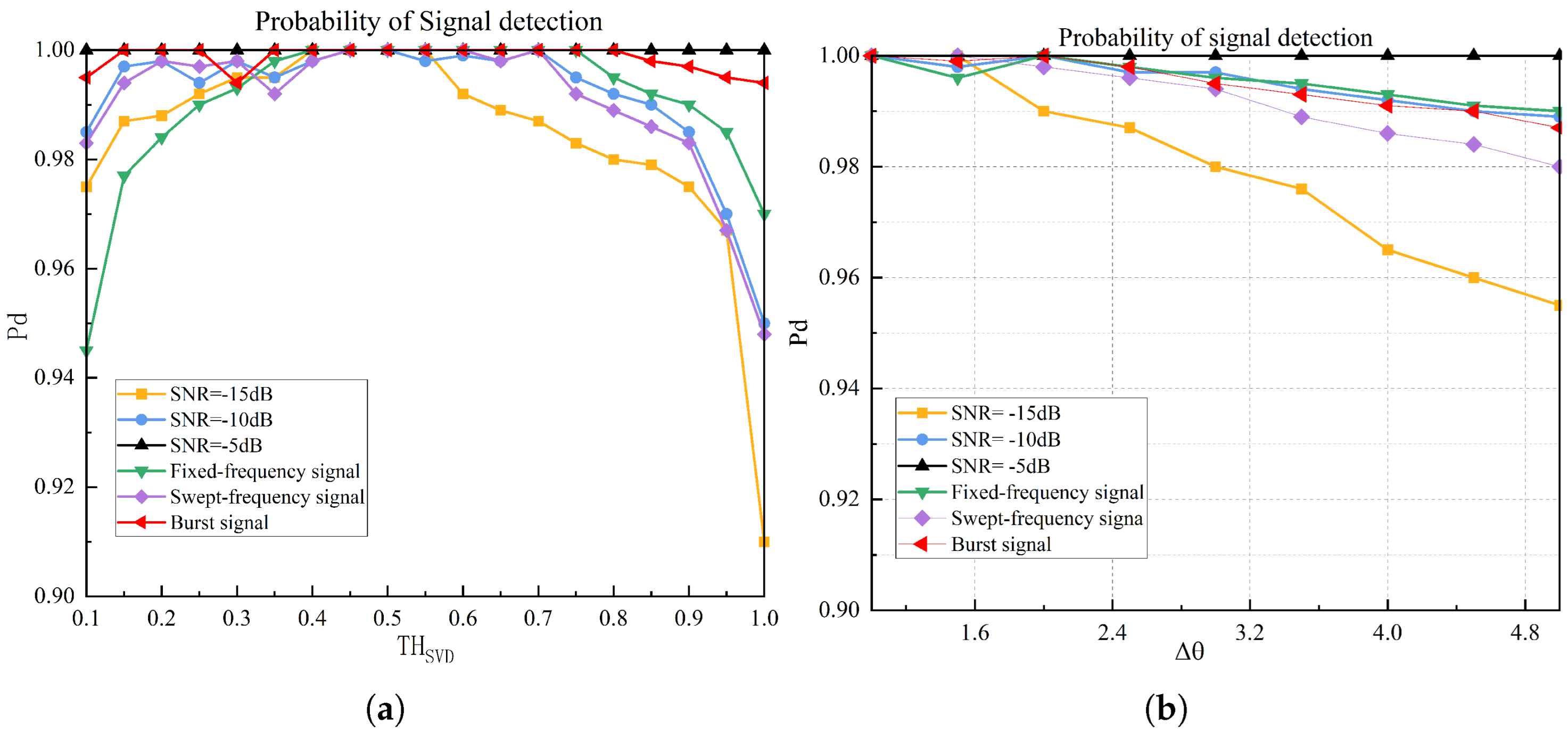

- Effect of singular value threshold and Hough transform quantization interval on detection performance.

- (4)

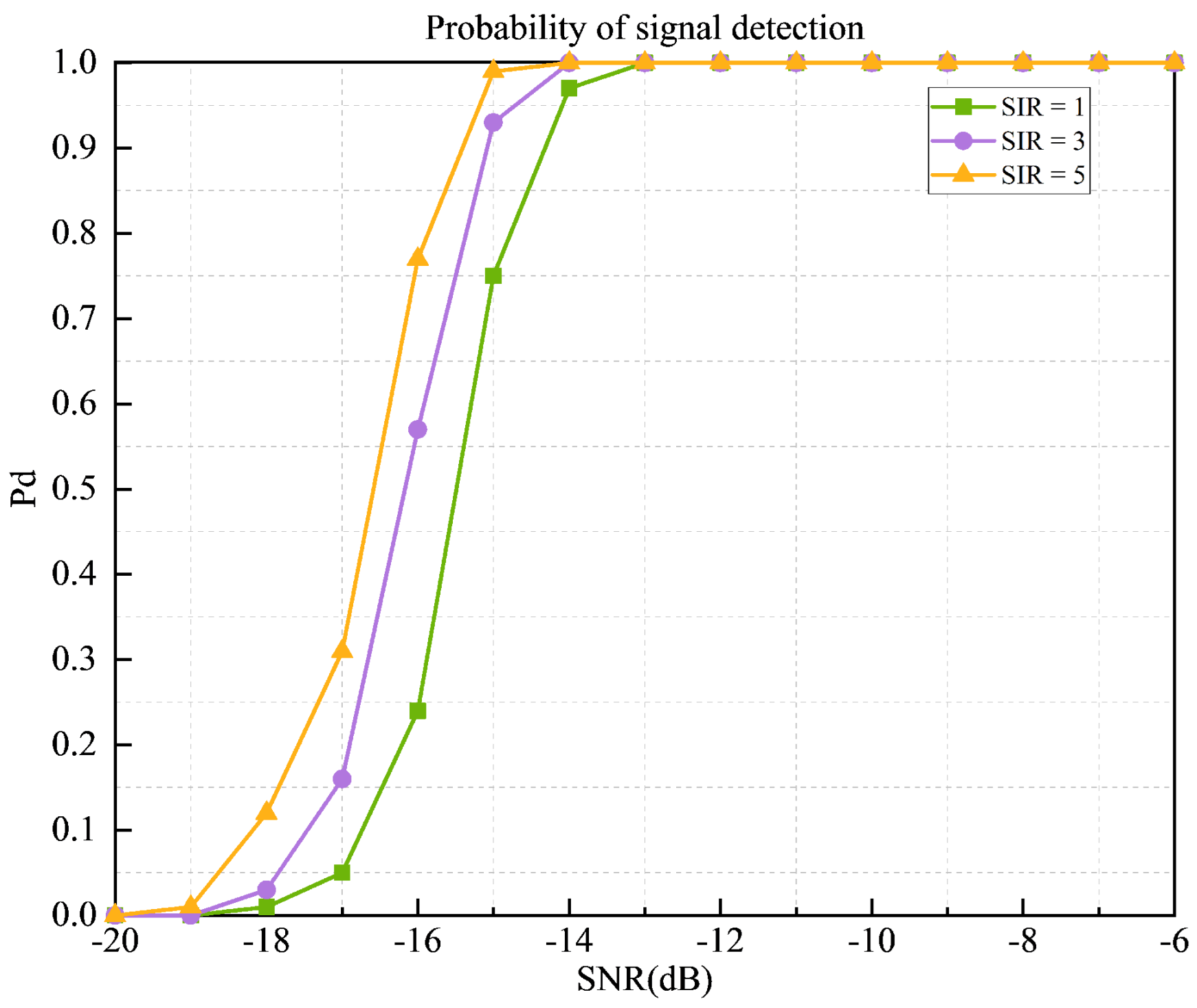

- Signal detection performance under varying interference levels.

- (5)

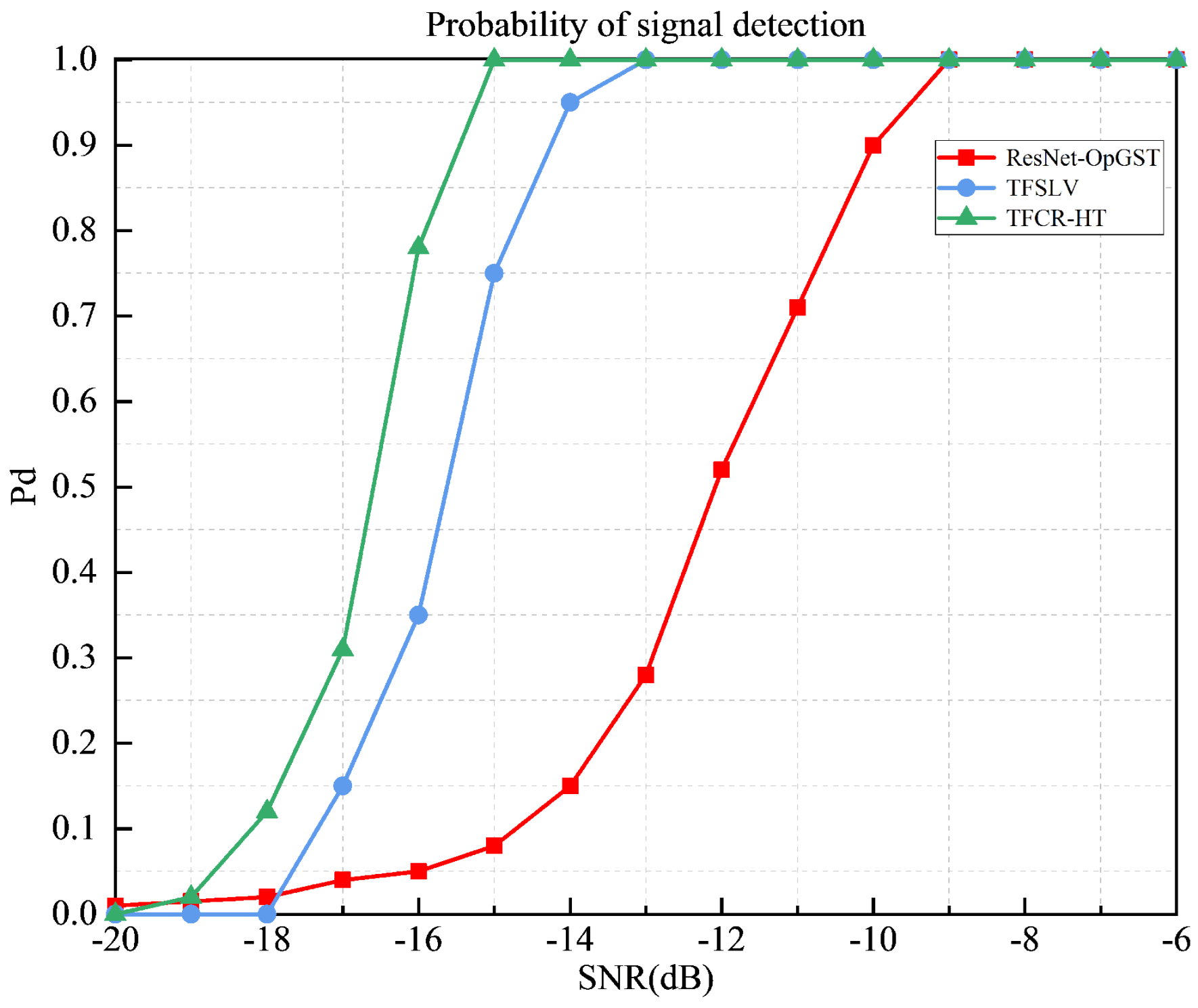

- Performance comparison between different detection algorithms

4.4. Algorithm Validation Based on Measured Signals

5. Discussion and Future Work

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, X.; Zhao, M.M.; Li, M.; Li, L.; Zhao, M.J.; Wang, J. Ambiguity Function Analysis and Optimization of Frequency-Hopping MIMO Radar with Movable Antennas. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 21836–21851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirayesh, H.; Zeng, H. Jamming attacks and anti-jamming strategies in wireless networks: A comprehensive survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2022, 24, 767–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubiak, I. Wireless Communication: Applications Security and Reliability—Present and Future. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, J.; Mohril, R.S.; Lad, B.K.; Kulkarni, M.S. Logistics, Reliability, Availability, Maintainability and Safety (L-RAMS) for Intelligent, Interconnected, Digital and Distributed (I2D2) Empowered Futuristic Military Systems. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2024, 71, 5869–5884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özmen, S.; Hamzaoui, R.; Chen, F. Survey of IP-based air-to-ground data link communication technologies. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2024, 116, 102579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeza, V.M.; Parada, R.; Salor, L.C.; Monzo, C. AI-Driven Tactical Communications and Networking for Defense: A Survey and Emerging Trends. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.05071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Zhang, W.; Li, S.; Zhang, B. CML based parameter estimation of FH signals in alpha stable noise environment. Signal Image Video Process. 2024, 18, 7981–7988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Liao, S.; Wang, L.; Gao, J.; Chu, X.; Luo, A. An adaptive frequency-hopping detection for slowly-varying fading dispersive channels. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2024, 155, 2959–2972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, R.; Li, B. Detection and simulation of quasi random frequency hopping signal based on interference analysis algorithm. Neural Comput. Appl. 2023, 35, 8847–8858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Same, M.H.; Gleeton, G.; Gandubert, G.; Ivanov, P.; Landry, R.J. Multiple narrowband interferences characterization, detection and mitigation using simplified welch algorithm and notch filtering. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Guo, Y.; Meng, Q. Blind parameter estimation of frequency-hopping signals based on atomic decomposition. In Proceedings of the 2009 First International Workshop on Education Technology and Computer Science, Wuhan, China, 7–8 March 2009; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2009; Volume 3, pp. 713–716. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.J.; Liu, R.Y.; Song, H.J. A method of the detection of frequency-hopping signal based on channelized receiver in the complicated electromagnetic environment. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Intelligent Information Hiding and Multimedia Signal Processing (IIH-MSP), Adelaide, SA, Australia, 23–25 September 2015; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 294–297. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, C.; Kim, J.Y.; Na, S.Y.; Kim, H.G.; Choi, S.H. Compressive frequency hopping signal detection using spectral kurtosis and residual signals. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2017, 94, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.G.; Oh, S.J. Detection of fast frequency-hopping signals using dirty template in the frequency domain. IEEE Wirel. Commun. Lett. 2018, 8, 281–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, B.; Wang, H.; Wu, B.; Guo, D. Hopping time estimation of frequency-hopping signals based on HMM-enhanced Bayesian compressive sensing with missing observations. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2022, 26, 2180–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, F.; Fan, G.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y. A fast estimation algorithm for parameters of multiple frequency-hopping signals based on compressed spectrum sensing and maximum likelihood. Electronics 2023, 12, 1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Wang, Y.; Jin, H.; Lei, Y. Parameter Estimation Algorithm of Frequency-Hopping Signal in Compressed Domain Based on Improved Atomic Dictionary. Sensors 2023, 23, 5065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Zheng, H.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, J.; Jiang, Y. Joint Optimization of Carrier Frequency and PRF for Frequency Agile Radar Based on Compressed Sensing. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhu, R. Frequency hopping signal detection based on wavelet decomposition and Hilbert–Huang transform. Mod. Phys. Lett. B 2017, 31, 1740078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yixuan, G.; Zhi, L.; Jian, L.; Jianhua, Z. Parameter estimation of frequency hopping signal based on MWC–MSBL reconstruction. IET Commun. 2020, 14, 1642–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Shin, Y.; Lee, H.; Park, J.; Lee, H. Radio frequency fingerprinting for frequency hopping emitter identification. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 10812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, P. Jamming detection in broadband frequency hopping systems based on multi-segment signals spectrum clustering. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 29980–29992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Jiang, C.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, T. A Time–Frequency Domain Analysis Method for Variable Frequency Hopping Signal. Sensors 2024, 24, 6449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aydin, M.; Dalveren, Y.; Kara, A.; Derawi, M. The Fast and Reliable Detection of Multiple Narrowband FH Signals: A Practical Framework. Sensors 2024, 24, 4812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Sun, Q.; Li, Y. A novel underdetermined blind source separation algorithm of frequency-hopping signals via time-frequency analysis. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2023, 70, 4286–4290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Fan, F.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, W.; Wu, S.; Wang, S. A joint STFT-HOC detection method for FH data link signals. Measurement 2021, 177, 109225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.; Luo, F.; Hu, X. Distributed Passive Positioning and Sorting Method for Multi-Network Frequency-Hopping Time Division Multiple Access Signals. Sensors 2024, 24, 7168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, W.; Jin, H.; Wang, J.; Lei, Y.; Lou, C.; Liu, C. Variable-Speed Frequency-Hopping Signal Sorting: Spectrogram Is Sufficient. Electronics 2023, 12, 4533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.P.; Chang, C.H.; Chen, J.C. Low-False-Alarm-Rate Timing and Duration Estimation of Noisy Frequency Agile Signal by Image Homogeneous Detection and Morphological Signature Matching Schemes. Sensors 2023, 23, 2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xu, C.; Zhao, X.; Li, J.; Dang, X. Joint estimation method for space-time frequency parameters of frequency-hopping network station in the case of low-quality data. Comput. Commun. 2025, 241, 108234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, B.; Wang, H.; Wu, B.; Guo, D. Parameter estimation of multiple frequency-hopping signals based on space-time-frequency analysis by atomic norm soft thresholding with missing observations. China Commun. 2022, 19, 135–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olesiński, A.; Piotrowski, Z. Clustering Method for Signals in the Wideband RF Spectrum Using Semi-Supervised Deep Contrastive Learning. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Zou, J.; Gao, J.; Zhang, G.; Kong, M.; Pei, Z.; Cui, K. A new frequency hopping signal detection of civil UAV based on improved K-means clustering algorithm. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 53190–53204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, H. Frequency hopping signal detection based on optimized generalized S transform and ResNet. Math. Biosci. Eng. MBE 2023, 20, 12843–12863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Shi, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Yu, X.; Shi, Y. Unlocking signal processing with image detection: A frequency hopping detection scheme for complex EMI environments using STFT and CenterNet. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 46004–46014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Jiang, Y. Knowledge-Enhanced Compressed Measurements for Detection of Frequency-Hopping Spread Spectrum Signals Based on Task-Specific Information and Deep Neural Networks. Entropy 2022, 25, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; He, S.; Wang, C.; Li, Z.; Li, J.; Dai, H.; Xie, J. Detection and parameter estimation of frequency hopping signal based on the deep neural network. Int. J. Electron. 2022, 109, 520–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, B.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Gong, K. Signal sorting algorithm of hybrid frequency hopping network station based on neural network. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 35924–35931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Liu, F. Adaptive joint carrier and DOA estimations of FHSS signals based on knowledge-enhanced compressed measurements and deep learning. Entropy 2024, 26, 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Shi, Y.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, L.; Yu, X.; Li, X. A Small-Object Detection Based Scheme for Multiplexed Frequency Hopping Recognition in Complex Electromagnetic Interference. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2024, 28, 902–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, X.; Huang, Y. Parameter estimation of frequency-hopping signal in UCA based on deep learning and spatial time–frequency distribution. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 7460–7474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.G.; Oh, S.J. Detection of frequency-hopping signals with deep learning. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2020, 24, 1042–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Wang, W.; Ding, G.; Wu, Q.; Liu, Z. Frequency-hopping frequency reconnaissance and prediction for non-cooperative communication network. China Commun. 2021, 18, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liao, H.; Yuan, S.; Liu, N. A learning-based signal parameter extraction approach for multi-source frequency-hopping signal sorting. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2023, 30, 1162–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, K.; Qian, Z.; Wang, M.; Wang, D. Few-shot learning based blind parameter estimation for multiple frequency-hopping signals. Multidimens. Syst. Signal Process. 2023, 34, 271–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Hao, D.; Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Zhong, Z.; Zhao, Z. Intelligent identification and classification of small UAV remote control signals based on improved yolov5-7.0. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 41688–41703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, N.; Mao, S.; Zhou, C.; Sun, G.; Shi, Z.; Chen, J. DroneRFa: A large-scale dataset of drone radio frequency signals for detecting low-altitude drones. J. Electron. Inf. Technol. 2023, 45, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

| Signal Type | Parameter Description | Key Parameter Settings |

|---|---|---|

| FH signal | Frequency, period | 4–15 MHz, 0.1 ms |

| Burst signal | Frequency, duration | 5, 7, 18 MHz, 0.03 ms |

| Chirp signal 1 | Frequency, period | 0.1–1 MHz, 0.1 ms |

| Chirp signal 2 | Frequency, period | 16.1–17 MHz, 0.1 ms |

| Fixed-frequency signal | Frequency | 6.5 MHz, 12.5 MHz |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, H.; Yang, L.; Bin, J.; Gou, C.; Hou, B.; Qin, M. A Detection Method for Frequency-Hopping Signals in Complex Environments Using Time–Frequency Cancellation and the Hough Transform. Electronics 2026, 15, 429. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15020429

Wang H, Yang L, Bin J, Gou C, Hou B, Qin M. A Detection Method for Frequency-Hopping Signals in Complex Environments Using Time–Frequency Cancellation and the Hough Transform. Electronics. 2026; 15(2):429. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15020429

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Huan, Lian Yang, Jie Bin, Chunyan Gou, Baolin Hou, and Mingwei Qin. 2026. "A Detection Method for Frequency-Hopping Signals in Complex Environments Using Time–Frequency Cancellation and the Hough Transform" Electronics 15, no. 2: 429. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15020429

APA StyleWang, H., Yang, L., Bin, J., Gou, C., Hou, B., & Qin, M. (2026). A Detection Method for Frequency-Hopping Signals in Complex Environments Using Time–Frequency Cancellation and the Hough Transform. Electronics, 15(2), 429. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15020429