Abstract

Network intrusion behaviors exhibit high concealment and diversity, making intrusion detection methods based on single-behavior modeling unable to accurately characterize such activities. To overcome this limitation, we propose SGMT-IDS, a dual-branch semi-supervised intrusion detection model based on Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) and Transformers. By constructing two views of network attacks, namely structural and behavioral semantics, the model performs collaborative analysis of intrusion behaviors from both perspectives. The model adopts a dual-branch architecture. The SGT branch captures the structural embeddings of network intrusion behaviors, and the GML-Transformer branch extracts the semantic information of intrusion behaviors. In addition, we introduce a two-stage training strategy that optimizes the model through pseudo-labeling and contrastive learning, enabling accurate intrusion detection with only a small amount of labeled data. We conduct experiments on the NF-Bot-IoT-V2, NF-ToN-IoT-V2, and NF-CSE-CIC-IDS2018-V2 datasets. The experimental results demonstrate that SGMT-IDS achieves superior performance across multiple evaluation metrics.

1. Introduction

The communication protocols among IoT devices are highly diverse, and some protocols exhibit weak security designs, making them susceptible to various intrusion attacks such as malware infection, data theft, and denial-of-service attacks. Attackers may even leverage radio-frequency energy harvesting techniques to perform side-channel attacks against devices [1]. Traditional feature-based intrusion detection systems suffer from several limitations, such as low detection rates for zero-day attacks, poor scalability, and limited detection accuracy [2]. Models based on the Transformer architecture [3,4], through their self-attention mechanisms, are able to capture feature representations more effectively and have achieved state-of-the-art performance in many tasks [5]. Nevertheless, each intrusion type exhibits unique behavioral characteristics and propagation patterns. When network intrusions are detected solely based on statistical information, sequential information, or raw packet data, it becomes difficult to identify attack variants [6]. Current intrusion detection methods still face the following two challenges.

The greatest challenge lies in the fact that network traffic exhibits highly structured characteristics [7], making intrusion detection methods based on single-behavior modeling ineffective in capturing these complex relationships. Integrating network topology and behavioral semantics enables a more accurate characterization of intrusion behaviors. Studies [8] have shown that network traffic contains rich behavioral features that can reveal network activities even under encrypted conditions. Transformer-based network intrusion detection models can effectively capture long-range dependencies in network traffic [9], and the occurrence of network behaviors simultaneously depends on the network’s topological structure. Connections, routing paths, subnet partitioning, and dynamic changes in topology impose constraints that influence the manifestation of network behaviors. GNNs, with their unique message-passing mechanism, can aggregate multi-hop information from nodes. GNNs not only capture direct relationships among entities but also uncover higher-order connections, such as multi-hop contextual dependencies [7]. Moreover, during the learning process for labeled nodes, GNNs can influence other unlabeled nodes within their receptive field [10]. For example, when one local host experiences a network attack, other hosts within the same local network are likely to be exposed to similar threats. Therefore, by further analyzing the interaction relationships in network behaviors, intrusion activities can be captured more effectively.

Another key challenge is that current deep learning-based intrusion detection methods are limited by the scarcity and limited timeliness of high-quality labeled data. These methods rely on manually annotated labels to learn data distributions and establish category mappings. However, in real-world network environments, data annotation incurs substantial human labor costs, and typically only a small portion of network traffic can be labeled. Moreover, intrusion behaviors continuously evolve, making it impractical to fully annotate all network activities. Semi-supervised intrusion detection methods, which reduce reliance on labeled data, therefore hold significant promise.

To address the aforementioned challenges, we propose SGMT-IDS, a novel dual-branch semi-supervised intrusion detection model for IoT environments. Unlike traditional deep learning-based approaches, our method does not require large amounts of labeled traffic. It further exploits the network’s topological structure and behavioral semantics, enabling the learning and identification of network traffic characteristics from multiple dimensions. As a result, the model can effectively detect malicious network behaviors using only a very small number of labeled samples. The major contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

- We propose SGMT-IDS, a dual-branch semi-supervised intrusion detection method that integrates Graph Neural Networks and Transformers. By combining the GNN’s capability for extracting local structural features with the Transformer’s ability to capture long-range dependencies, the model learns both the spatial topological structure and behavioral characteristics of network traffic, enabling accurate intrusion detection in IoT environments.

- We propose a two-stage training strategy based on a semi-supervised learning paradigm, which can be applied to real-world network environments without requiring a large number of manually labeled samples from domain experts.

- We evaluate SGMT-IDS on three widely used intrusion detection datasets. Experimental results show that the proposed model outperforms state-of-the-art methods across multiple performance metrics.

2. Related Work

2.1. GNN-Based Intrusion Detection Methods

Most current deep learning methods rely solely on payload information from network traffic and overlook the underlying network topology. Graph neural networks excel at modeling the topological structure of network data and have thus been widely applied in intrusion detection. Hu et al. [11] constructed graph nodes using packet byte sequences and embedded application-layer information into the packet-level graph topology, combining graph convolution with LSTM for classification. Wang et al. [12] proposed a spatiotemporal graph model that constructs neighbor routing tables based on temporal traffic characteristics and spatial topology, followed by message passing using MPNN. Guo et al. [13] developed a dynamic topology algorithm that builds graphs on temporal slices of network behavior and incorporates degree centrality and betweenness centrality to characterize DDoS attacks, integrating GAT and LSTM to extract dynamic behavioral features. Duan et al. [14] introduced a continuous-time graph detection method, which provides finer temporal granularity than discrete dynamic graphs and uses time encoders and GRU to capture temporal information of network flows. Addressing the limitation that packet-level information is often ignored in IoT-based DDoS detection, Lo et al. [15] proposed E-GraphSAGE to extract global traffic patterns and flow-level relationships while utilizing network topology and statistical flow features.

Existing graph-based intrusion detection methods can effectively capture local topological structures and neighborhood dependencies; however, in cross-host and multi-stage intrusion behaviors, feature aggregation is often constrained by the recursive neighborhood aggregation bottleneck. Unlike these approaches, this work introduces a Transformer to establish global dependencies within intrusion behaviors, complementing the expressive limitations of graph-based models and enabling more effective extraction of intrusion behavior features.

2.2. Transformer-Based Intrusion Detection Methods

Graph neural networks have been widely applied to node classification tasks; however, because GNNs rely on neighborhood information aggregation, they are prone to over-smoothing. Transformers, with their capability for long-range dependency modeling, can effectively characterize the global semantic relationships within intrusion behaviors. Liu et al. [16] performed intrusion detection by integrating the spatiotemporal characteristics of network traffic, employing a Vision Transformer (ViT) to capture global traffic features and STFE to extract its spatiotemporal patterns. Wu et al. [17] utilized a stacked encoder–decoder architecture to learn low-dimensional feature representations from high-dimensional raw data, effectively balancing dimensionality reduction and feature preservation in imbalanced datasets and thereby improving intrusion detection performance. Manocchio et al. [18] proposed FlowTransformer, a framework designed to identify long-term behaviors and complex patterns in network traffic; it supports interchangeable input encoding schemes and classification heads, removing the difficulty of selecting encoding formats and output modules. Yu et al. [19] incorporated a multi-head fast attention mechanism into the Transformer encoder and applied a parameter optimization algorithm based on particle swarm mutation, enhancing the adversarial robustness and feature mining capability of generated samples, while improving computational efficiency and real-time detection performance.

Transformer-based intrusion detection methods offer significant advantages in capturing global semantics and long-range dependencies. Integrating Transformers with GNNs further enhances the modeling of behavioral semantics in network traffic. Existing studies [20,21,22] have explored integrating GNNs with Transformers to enhance node representation learning, including converting graph structures into various types of tokens for Transformer-based modeling and combining the local aggregation capability of GNNs with the global context modeling strength of Transformers. Distinct from these approaches, our dual-branch architecture incorporates both cross-branch information interaction and intra-branch feature fusion, enabling a comprehensive representation of network traffic in terms of both topological structure and behavioral semantics. This design provides a notable advantage over previous methods.

2.3. Label-Efficient Intrusion Detection Methods

Most intrusion detection models require large amounts of labeled data for training. Duan et al. [2] proposed a dynamic line-graph neural network that updates edges according to the temporal evolution of traffic. By leveraging spatiotemporal network information, their method effectively captures anomalous traffic patterns even with limited labeled data. Building on E-GraphSAGE, Cao et al. [23] adopted a contrastive learning approach, generating negative samples by perturbing edge features and maximizing the local and global mutual information between positive and negative samples during training. Xu et al. [24] proposed NEGAT, an edge-graph attention model for network flows, which optimizes the model using Wasserstein distance between sampled and generated subgraph edges, as well as Gromov–Wasserstein distance over graph topology, allowing self-supervised training. Mao et al. [25] introduced FeCoGraph, a label-aware joint graph contrastive learning framework that generates two augmented views via perturbations and computes contrastive loss guided by labels along with cross-entropy loss on original features. Wu et al. [26] proposed a time-contrastive intrusion detection model that trains the encoder using temporal, asymmetric, and masked contrastive objectives, followed by a LightGBM classifier for detection.

The above methods have achieved notable progress under limited labeling, but they all rely on a single type of behavioral information and are therefore unable to simultaneously capture both the topological structure and the semantic characteristics of network behaviors. In contrast to existing approaches, the proposed SGT branch captures the interaction patterns inherent in network behaviors, while the designed GML-Transformer effectively models their global semantic relationships. Moreover, the introduction of a contrastive-learning-based two-stage training strategy enables effective learning under semi-supervised constraints.

3. Method

3.1. Architectural Overview

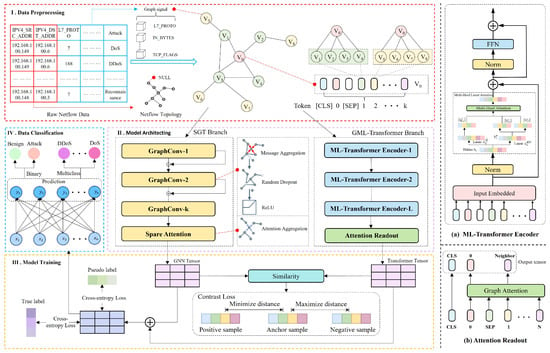

SGMT-IDS consists of four components, and its overall architecture is illustrated in Figure 1. First, we construct a network topology graph G based on the IP communication relationships among network hosts to preserve the topological structure of network behaviors. Then, the SGT branch is used to aggregate node information and obtain the topological representation of network traffic. On this basis, we employ the GML-Transformer to extract the contextual semantic information of network behaviors. After fusing the two different representations of network behaviors, the model is trained in two stages. In the first stage, labeled samples are used to guide supervised learning. In the second stage, pseudo-labels serve as soft supervisory signals, and contrastive learning is applied to maximize the information contained in unlabeled data. Finally, the fused node embeddings generated by the dual branches are fed into a classifier to accomplish the intrusion detection task.

Figure 1.

The model architecture based on SGMT-IDS.

3.2. Graph Construction

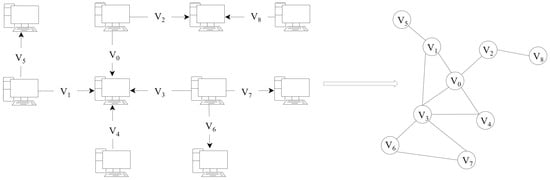

In our study, we represent network traffic as a topology graph , where V denotes the set of nodes, E the set of edges, and X the set of features. We treat the traffic flows between different IP addresses as nodes, and the node features consist of statistical characteristics of the flows, such as protocol type, flow duration, and IP packet length. Unlike the approach [2], which incurs substantial computational overhead by converting data into a line graph, we construct the network traffic as an undirected graph to reduce resource consumption, as illustrated in Figure 2. Two flows are connected if they share the same source or destination IP address. When intrusion activities occur, nodes with similar information propagation patterns are more likely to be compromised. Our graph construction method does not directly rely on IP addresses or ports, allowing the structural relationships among different entities to be represented more intuitively.

Figure 2.

Construction of the Network Topology Graph.

3.3. SGT Model Branch

Network traffic exhibits a highly structured nature, with intrinsic correlations among behavioral features. Many attacks differ significantly from normal traffic in their topological patterns, and their characterization relies on structural information that cannot be effectively captured through discrete statistical features alone. The proposed SGT branch is capable of capturing high-order information interactions within intrusion behaviors and learning structural dependencies among flows. The SGT branch integrates graph convolutional networks with the attention mechanism of Transformers. First, graph convolution aggregates neighborhood information to capture anomalous signals induced by local topological perturbations. Subsequently, sparse attention further aggregates cross-neighborhood structural information, enhancing the representations of critical nodes and producing more discriminative node embeddings. Consequently, SGT can extract network topological information from complex intrusion behaviors.

For the node classification task, graph convolution demonstrates high effectiveness in feature extraction. However, naively stacking multiple graph convolution layers often results in over-smoothing, which reduces the discriminability among different attack types. To mitigate this issue, we incorporate graph convolution with residual connections, which effectively alleviates the over-smoothing phenomenon. The computation process is formulated as follows:

where A denotes the original adjacency matrix, I is the identity matrix, and is the degree matrix of with , representing the sum of the elements in the i-th row. The matrix denotes the node feature representation at layer l. is the learnable weight matrix, and denotes a nonlinear activation function.

In traditional GCNs, deep stacking often leads to excessive smoothing of node features, which weakens the discriminability of node representations. To address this issue, a residual fusion mechanism is introduced after each convolution operation. Specifically, the input features are linearly transformed and fused with the convolution output in a weighted manner, defined as:

where is the residual fusion coefficient used to balance the contributions between convolutional features and original features.

Given the encoded node representation matrix , a sparse attention module is applied. The node features are first projected into the query, key, and value spaces through linear transformations:

where , , and are learnable parameters. The attention coefficient between node i and node j is defined as:

where attention is computed only for node pairs connected by an edge. The sparse attention weights are then obtained through softmax normalization:

where denotes the neighbor set of node i. Each node representation is updated by aggregating information from its neighbors:

The multi-head attention mechanism concatenates the representations from multiple heads and applies a linear projection to obtain the final output:

Finally, residual connection and layer normalization are applied to obtain the SGT module output:

3.4. GML-Transformer Model Branch

We construct the GML-Transformer branch to extract the semantic information of network behaviors. Unlike the SGT branch, which emphasizes the structural characteristics of network behaviors, the GML-Transformer is designed to capture contextual semantic information and complement the local behavioral patterns embedded in the graph structure. Network traffic typically contains rich behavioral characteristics. Semantic-Hoptoken constructs semantically informative sequences from traffic flows that exhibit interaction relationships, and the GML-Transformer subsequently captures global dependencies among these flows. This enhances the semantic representation of network behaviors and enables the model to identify complex attack patterns.

3.4.1. Semantic-Hoptoken

Graph data exhibit complex non-Euclidean structures, whereas Transformer models require one-dimensional token sequences as input. NAGphormer constructs a sequence for each node based on the labels of its multi-hop neighbors [27]. Inspired by this idea, we design the Semantic-HopToken to enhance the semantic representation of nodes. We first define the multi-hop neighborhood representation of a node v. Let the k-hop neighborhood representation of node v be denoted as:

where represents the k-hop representation of node v, A is the normalized adjacency matrix of the graph, and H is the node feature matrix. Specifically, denotes the k-th power of the adjacency matrix, which captures multi-hop relationships between nodes. The k-hop neighborhood of a node v represents structural information at different scales. For example, the 1-hop neighborhood reflects local information from the node’s immediate neighbors, while the 2-hop neighborhood captures indirectly connected relational information. This multi-scale representation enhances the model’s ability to identify continuous propagation patterns in multi-stage attacks.

After obtaining the multi-hop neighborhood representations of each node, we construct them into a sequence of tokens. To further enhance the global expressiveness of the sequence, we adopt a processing strategy similar to the BERT model. A special token [CLS] is inserted at the beginning of the target node’s sequence to aggregate the contextual information of the entire sequence. Meanwhile, a [SEP] token is inserted between the target node and its neighborhood tokens to indicate the boundary within the sequence. The relationships between the target node and its neighboring nodes are thus embedded into a unified token sequence through multi-hop neighborhood aggregation. This design preserves local feature dependencies while providing complete contextual information to the Transformer model.

3.4.2. GML-Transformer

The overall framework of the GML-Transformer is illustrated in Figure 1. Based on the token sequence obtained in the previous subsection, each token is first fed into the Transformer encoder to capture semantic interactions among nodes across different neighborhoods, producing node embeddings under multiple hop-based views.

Multi-head latent attention (MLA). To enhance the model’s capability to capture both global and local dependencies while reducing computational overhead, we adopt the Multi-head Latent Attention mechanism. Unlike traditional multi-head self-attention, MLA models global dependencies and perform feature fusion in a low-dimensional latent space, reducing redundant computation while preserving information integrity. Given an input sequence , the original high-dimensional input is first projected into the latent space by a linear transformation , where . Then, multi-head attention is computed as . All attention heads are concatenated and linearly mapped to obtain the final output . Here, the latent dimension is considerably smaller than d, which substantially improves computational efficiency. Compared with standard multi-head attention, MLA reduces time complexity from to while retaining strong global dependency modeling capability.

Transformer encoder. The detailed structure of the Transformer encoder is shown in Figure 2. We follow the encoder part of the original Transformer while removing the decoder. The obtained k-hop neighborhood representation is first converted into a token sequence using the Semantic-HopToken, and then linearly projected as the input to the Transformer encoder.

where E is a learnable parameter matrix and denotes the input token sequence.

We feed into the Transformer encoder, which consists of a Multi-head Latent Attention layer, a feed-forward network (FFN), and layer normalization.

where l denotes the layer index of the Transformer.

Graph Attention Layer. In intrusion detection tasks, the topological information of nodes plays a critical role in distinguishing attacks. For the feature matrix encoded by the Transformer, we apply a GAT module to perform weighted aggregation of the information from neighboring nodes, thereby enhancing the representation of the target node. The input sequence consists of three parts: the CLS token representing global information, the encoded target node , and the embeddings of the target node’s neighbors . To compute attention weights between nodes, we calculate the attention scores between the target node and all its neighbors, and use the obtained attention coefficients to perform weighted aggregation over neighbor nodes. Specifically, the aggregated representation of neighbor nodes for the target node is given by:

We concatenate the CLS token, the target node, and the aggregated neighbor representation to obtain the final representation of the target node:

Finally, the output represents the target node, encoding both its own features and information from its neighbors. The GAT module dynamically adjusts the weights of neighboring nodes, enabling effective modeling of node relationships in the graph, thus providing strong representational capability for graph-based learning.

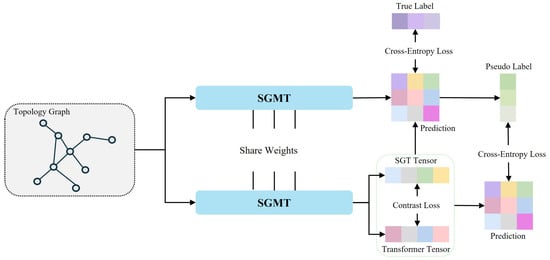

3.5. Semi-Supervised Integrated Optimization

Our model is trained in two stages. In the first stage, a small number of labeled samples are used for supervised training, and the model is optimized using the cross-entropy loss. In the second stage, the trained model is used to assign pseudo-labels to unlabeled samples. Then, based on the pseudo-labels, cross-entropy loss is computed, and contrastive loss is calculated between the representations obtained from the two encoders. By integrating the cross-entropy loss and contrastive loss of both labeled and unlabeled samples, joint optimization is performed. The overall training process is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

SGMT training framework.

Cross-entropy training with labeled samples. In the initial training stage, we use all labeled data to perform supervised training. The objective of this stage is to enable the model to learn effective feature representations from samples with known labels. We adopt the standard cross-entropy loss function, which is defined as follows:

where denotes the ground-truth label of the i-th sample, represents the predicted probability that the sample belongs to class c, N is the total number of samples, and C is the number of classes.

Cross-entropy training with unlabeled samples. After completing the supervised training, the optimized model is used to predict the labels of the unlabeled data, and the predicted results are treated as pseudo labels. These pseudo labels are then used to compute the cross-entropy loss for the unlabeled samples. The cross-entropy loss for unlabeled data is defined as:

where M is the number of unlabeled samples, and denotes the predicted probability that the i-th unlabeled sample belongs to class c.

To reduce the accumulated error caused by noisy pseudo labels during training, we introduce a confidence-based filtering mechanism. Specifically, the model first predicts the class probability distribution of each unlabeled sample, and the confidence of a sample is defined as the maximum predicted probability:

where denotes the prediction confidence of the i-th sample. Only samples whose confidence exceeds a predefined threshold are included in the pseudo-label training process.

Contrastive loss. We adopt the InfoNCE contrastive loss to train the model. The representations of the same node encoded by the two encoders are treated as positive pairs, while representations of different nodes serve as negative samples. The contrastive loss brings together the representations of the same sample across two views in the feature space, while pushing apart representations of different samples. We compute contrastive losses for both the graph view and the Transformer view.

For the contrastive loss between the graph view and the Transformer view:

For the contrastive loss between the Transformer view and the graph view:

We weight the losses of the two views as:

where denotes cosine similarity, is the temperature parameter, and is the balancing coefficient between the two terms.

To fully exploit the limited labeled data and abundant unlabeled data, we jointly optimize the cross-entropy loss for labeled samples, the cross-entropy loss for unlabeled samples, and the contrastive loss. The contrastive loss guides the model to learn more robust feature representations, especially under limited supervision, and helps prevent overfitting to noisy pseudo labels. The overall loss function is defined as:

where , , and are balancing coefficients.

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental Setup

4.1.1. Datasets

In this study, we adopt the v2 versions of the NF-CSE-CIC-IDS2018 [28], NF-Bot-IoT [28], and NF-ToN-IoT [28] datasets. These three datasets are NetFlow-based feature sets transformed from their original raw network traffic, each containing 43 features. The Bot-IoT [29] dataset was developed by the Cyber Range Lab of UNSW Canberra and consists of both normal traffic and botnet-generated malicious traffic. The attack types include DDoS, service scanning, and data exfiltration, covering multiple protocols. The CSE-CIC-IDS2018 [30] dataset was jointly created by the Communications Security Establishment and the Canadian Institute for Cybersecurity. Its attack infrastructure includes 50 attacker machines targeting multiple operating systems such as Windows and Ubuntu, executing persistent attacks over mainstream protocols including HTTP, HTTPS, SSH, and FTP. The ToN-IoT [31] dataset collects various attack techniques targeting web applications, IoT gateways, and computer systems within IoT networks, including DoS, DDoS, and ransomware attacks.

4.1.2. Data Preparation

The data processing procedure consists of the following steps. First, we perform data cleaning on the aforementioned network traffic datasets, and then construct the network topology graph as described in Section 3.2. Since source address spoofing is common in certain types of attacks—such as DoS and DDoS—which makes tracing traffic far from the host meaningless [24], we aggregate the 1-hop and 2-hop neighborhood information of each node. We split the dataset into training and testing sets with a ratio of 6:4. It is important to note that during the training phase, we strictly follow a semi-supervised learning setup: only 30% of the samples in the training set are provided with labels, while the remaining samples are unlabeled from the model’s perspective. In our experiments, due to the large size of the datasets and severe class imbalance—where normal samples dominate—we apply downsampling to reduce bias. Additionally, all relevant network statistical features are normalized before training.

4.1.3. Experimental Implementation

The proposed model is implemented using PyTorch and PyTorch Geometric. The architecture consists of 2 layers of the SGT module and 3 layers of the Transformer module. Dropout and LayerNorm are used between the input layer and the output layer of the model, and the ReLU activation function is used as the activation function. The encoder generates 64-dimensional output embeddings. A two-layer MLP is adopted as the projection head to align features. We employ the Adam optimizer for gradient-based optimization. During training, the confidence threshold for pseudo-label filtering is set to 0.9. The loss weights , , and are set to 1, 0.3, and 1, respectively, and the contrastive loss weight is set to 0.4. The experimental environment consists of an Intel i5-12400 CPU, 16 GB RAM, an RTX 4000 GPU with 8 GB VRAM, and a 64-bit Windows 10 operating system. The software setup includes Python 3.8, PyTorch 2.2.2, CUDA 11.8, and PyTorch Geometric 2.6.1.

4.2. Results Analysis

4.2.1. Binary Classification

We conduct binary classification experiments on the NF-BoT-IoT-V2, NF-ToN-IoT-V2, and NF-CSE-CIC-IDS2018-V2 datasets to evaluate the effectiveness of our method in distinguishing normal traffic from malicious traffic. The proposed model is compared with several state-of-the-art methods, including DLGNN [2], NEGSC [24], E-GRACL [32], and FeCoGraph [25]. The comparison results are presented in Table 1. We evaluate the performance of different models using four metrics: Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1-Score. On both the NF-BoT-IoT-V2 and NF-ToN-IoT-V2 datasets, our model achieves the best performance across all four metrics. On the NF-CSE-CIC-IDS2018-V2 dataset, our model attains an F1-Score of 99.21%, with other metrics remaining very close to those of DLGNN. Moreover, our model consistently achieves the highest Recall across the three datasets, indicating its strong ability to correctly identify attack traffic with minimal missed detections. Compared with other advanced methods, our model demonstrates more balanced and stable detection performance. These results confirm that the proposed approach exhibits strong reliability and robustness in binary classification tasks and can accurately identify network attacks even with limited labeled samples.

Table 1.

Performance comparison of binary classification methods on three datasets.

4.2.2. Multi-Class Classification

Comparison with Other Methods. To further assess the effectiveness of the proposed model in detecting diverse categories of network intrusions, we conduct multi-class classification experiments to evaluate its overall capability in distinguishing among multiple attack types and normal traffic. In these experiments, we compare our method with N-STGAT [33], NEGSC [24], E-GRACL [32], and FeCoGraph [25]. The comparison results are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Performance comparison of multi-class classification methods on three datasets.

Our method demonstrates significant advantages in overall accuracy and class-wise balance. On the NF-ToN-IoT-V2 dataset, both Recall and F1-Score show noticeable improvements, with Recall increasing by 26.03% compared to FeCoGraph. On the NF-BoT-IoT-V2 dataset, our method achieves 99.47% in both Recall and F1-Score, outperforming other state-of-the-art approaches. For the NF-CSE-CIC-IDS2018-V2 dataset, the Recall and F1-Score reached 99.13% and 99.12%, respectively. Despite the dataset containing more fine-grained attack categories, our model maintains consistently high performance. Overall, the experimental results indicate that our model exhibits excellent performance in multi-class classification tasks. It effectively captures the discriminative features among different attack types and demonstrates strong stability when identifying diverse intrusion behaviors.

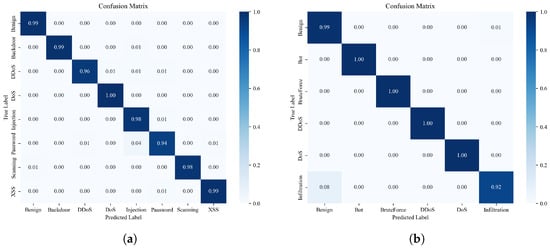

Multi-class Classification Results. In the multi-class classification experiments, we evaluated the performance of the proposed model on three datasets for recognizing various categories of network attacks. Precision, Recall, F1-score, False Positive Rate (FPR), and False Negative Rate (FNR) were used as the evaluation metrics for comprehensive assessment. Table 3 presents the multi-class classification results on the NF-ToN-IoT-V2 dataset, and Figure 4a visualizes the corresponding FPR and FNR. Overall, the model achieves high recognition accuracy across all categories. For lightweight attacks such as Scanning and XSS, the model reaches F1-scores of 0.9865 and 0.9843, respectively, indicating that the joint modeling of network topology features and sequential representations effectively captures the structural anomalies of Scanning and XSS attacks. The Backdoor and DoS attacks achieve F1-scores of 0.9917 and 0.9927, respectively. In particular, the recall for DoS reaches 0.9987 with an FNR of only 0.0012, indicating that the model is able to almost completely detect this type of attack with virtually no missed instances. Meanwhile, for more complex and high-frequency flooding attacks such as DDoS, the model still achieves an F1-score of 0.9748, demonstrating strong discriminative capability. These results show that the combination of graph structural feature modeling and Transformer-based sequence modeling effectively compensates for the limitations of traditional statistical feature methods in capturing relational patterns, allowing the model to remain robust across different attack strategies. In Table 4 and Table 5 and Figure 4b,c, we further provide the results on the other two datasets. The model consistently achieves high classification performance, with the F1-scores of many attack categories approaching or exceeding 0.99. This confirms that the proposed method enhances feature extraction capability and maintains stable discrimination performance even under scenarios with ambiguous class boundaries.

Table 3.

Multi-class classification results on the NF-ToN-IoT-V2 dataset.

Figure 4.

(a) Multiclass FPR and FNR on the NF-ToN-IoT-V2 dataset; (b) Multiclass FPR and FNR on the NF-BoT-IoT-V2 dataset; (c) Multiclass FPR and FNR on the NF-CSE-CIC-IDS2018-V2 dataset.

Table 4.

Multi-class classification results on the NF-BoT-IoT-V2 dataset.

Table 5.

Multi-class classification results on the NF-CSE-CIC-IDS2018-V2 dataset.

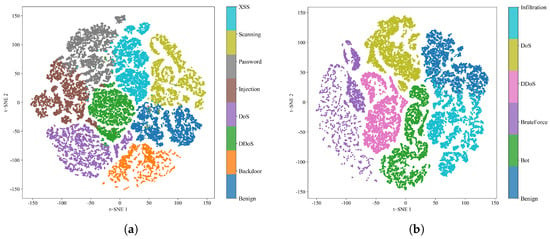

Figure 5 presents the confusion matrices of the two datasets. In the NF-ToN-IoT-V2 dataset, attack detection is relatively accurate, whereas in the NF-CSE-CIC-IDS2018-V2 dataset, a small number of Infiltration attacks tend to be misclassified as normal samples. To further investigate this phenomenon, we visualize the high-dimensional embeddings obtained from the two datasets using t-SNE. As shown in Figure 6a, the NF-ToN-IoT-V2 dataset exhibits clear differences among various attack types, making them easily distinguishable. As illustrated in Figure 6b, the Infiltration attack shows a small region of overlap with normal samples, while the boundaries among the remaining clusters remain well separated. This demonstrates that our model is capable of effectively capturing the intrinsic characteristics of network behaviors.

Figure 5.

(a) Multiclass confusion matrix on the NF-ToN-IoT-V2 dataset; (b) Multiclass confusion matrix on the NF-CSE-CIC-IDS2018-V2 dataset.

Figure 6.

(a) Dimensionality reduction visualization of features in the NF-ToN-IoT-V2 dataset. (b) Dimensionality reduction visualization of features in the NF-CSE-CIC-IDS2018-V2 dataset.

4.2.3. Ablation Study

To evaluate the contribution of each component, we compare the graph-structure model SGT, the global feature extraction model GML-Transformer, and the combined SGMT-IDS model. Table 6 presents the performance comparison of the proposed model under the ablation study. On the NF-BoT-IoT-V2 dataset, SGMT-IDS achieves 99.47% across all four metrics, representing a slight improvement over SGT (99.29%) and a substantial gain compared to GML-Transformer (97.07%). In high-frequency IoT attack scenarios, although global information can capture certain dynamic behaviors, using it alone leads to noticeable performance degradation, while the local structural information provided by graphs compensates for this weakness. By integrating both feature types, the model exhibits enhanced stability and better decision boundary discrimination. On the NF-ToN-IoT-V2 dataset, the F1-scores of SGT and GML-Transformer reach 96.91% and 95.27%, respectively, while SGMT-IDS improves to 98.49%. Since NF-ToN-IoT-V2 contains more lightweight and stealthy attack types, a single feature space is insufficient to represent its diverse behavior patterns. This demonstrates that the proposed feature fusion mechanism effectively improves detection accuracy and robustness. On the NF-CSE-CIC-IDS2018-V2 dataset, the F1-scores of SGT and GML-Transformer are 98.93% and 97.00%, respectively, while the complete model further improves to 99.12%, indicating that incorporating topological features provides significant advantages in identifying complex attacks.

Table 6.

Classification methods on three datasets.

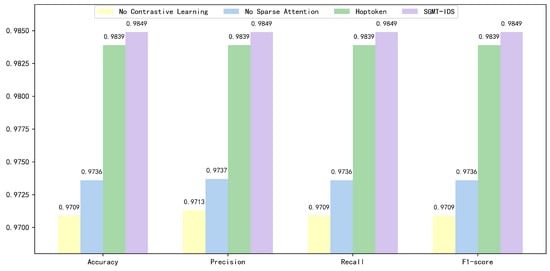

To further examine the contribution of each module to the overall performance, we conducted a more detailed ablation study on the NF-ToN-IoT-V2 dataset, focusing on the sparse attention structure in the SGT branch, the semantic hop aggregation mechanism of the Semantic-HopToken, and the contrastive learning objective. The results are presented in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Ablation study results.

When the SGT branch was replaced with a GCN module containing only residual connections, the model’s Accuracy and F1-score decreased to 0.9736, showing a substantial decline compared with the full model. This finding indicates that the sparse attention structure can reduce redundant neighborhood computation and more effectively focus on key topological dependencies in IoT network scenarios, thereby enhancing the discriminative capability of node representations.

When the Semantic-HopToken was replaced with the HopToken, the overall performance dropped to approximately 0.9839. Compared with the HopToken, which relies solely on structural neighborhood partitioning, the Semantic-HopToken introduces additional global semantics during multi-hop aggregation, enabling clearer differentiation of semantic levels. As network traffic often propagates across multiple nodes in IoT environments, the Semantic-HopToken provides more explicit semantic boundaries and global semantic information, thereby enhancing the model’s ability to capture contextual information related to potential attack behaviors. Due to its limited capacity to extract global semantics, the HopToken results in a slight decline in performance.

When the contrastive learning objective was removed and the model was trained only with pseudo-labeled cross-entropy loss, the performance further decreased to approximately 0.9709. The results demonstrate that contrastive learning improves model performance by enlarging inter-class distance and compressing intra-class variation. Moreover, it can effectively mitigate the impact of pseudo-label errors on model learning and enhance the robustness of the model under noise interference.

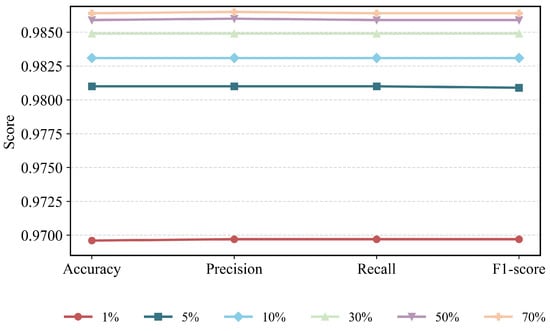

4.2.4. Varying Supervision Ratios

To further investigate the performance of our model, we conduct experiments under different proportions of labeled data. As shown in Figure 8, all evaluation metrics exhibit a consistent upward trend as the proportion of training data increases. When using only 1% of the training data, the model already achieves an average performance of approximately 0.9696. As the training ratio increases to 5% and 10%, the metrics further improve to about 0.9810 and 0.9831, respectively, indicating that even under extremely limited labeled data, our model maintains strong feature-learning and discriminative capabilities. When trained with only 30% of the data, the model already achieves a strong baseline performance, with an average metric value of approximately 0.9849. When the training proportion increases to 50%, all three metrics improve noticeably to around 0.9859, indicating that a sufficient amount of training samples can effectively enhance the model’s generalization capability. As the proportion further increases to 70%, the model performance becomes stable. Overall, the model maintains high and stable performance across different training data proportions, demonstrating strong robustness and generalization ability. Even with limited training samples, it is capable of extracting discriminative features and achieving reliable classification performance.

Figure 8.

Model performance comparison across varying training label ratios (1%, 5%, 10%, 30%, 50%, 70%).

5. Discussion

In this paper, we propose SGMT-IDS, a network intrusion detection model that integrates Graph Neural Networks and Transformer architectures. SGMT-IDS constructs network traffic as a graph structure, leveraging the advantages of GNNs in capturing topological patterns and local structural features, while incorporating the Transformer’s capability to model long-range dependencies and multi-level semantic interactions. Furthermore, the graph structure is transformed into a sequence representation with semantic enhancement, enabling the model to capture communication relationships across multiple hosts. In addition, we employ a semi-supervised learning strategy to train the model, where pseudo labels and contrastive loss are used to exploit the intrinsic structure of unlabeled data. We validate the effectiveness of the proposed approach on multiple real-world datasets. Compared with existing intrusion detection methods, our model requires only a small number of labeled samples for training, while demonstrating superior adaptability and robustness in handling complex attack patterns and identifying potential abnormal traffic. Overall, our model effectively extracts and integrates both local and global characteristics of network traffic, achieving improved detection performance. For future work, we plan to explore incremental learning techniques to further enhance the model’s adaptability to emerging attack types.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.W. and L.W.; methodology, Y.W.; software, Y.W.; validation, Y.W. and L.W.; formal analysis, L.W.; data curation, Y.W.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.W.; writing—review and editing, Y.W.; supervision, L.W.; project administration, L.W.; funding acquisition, L.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 62262004.

Data Availability Statement

NF-ToN-IoT-V2, NF-Bot-IoT-V2 and NF-CSE-CIC-IDS2018-V2 are available at https://staff.itee.uq.edu.au/marius/NIDS_datasets/ (accessed on 18 November 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ni, T.; Lan, G.; Wang, J.; Zhao, Q.; Xu, W. Eavesdropping mobile app activity via Radio-Frequency energy harvesting. In Proceedings of the 32nd USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 23), Anaheim, CA, USA, 9–11 August 2023; pp. 3511–3528. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, G.; Lv, H.; Wang, H.; Feng, G. Application of a dynamic line graph neural network for intrusion detection with semisupervised learning. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2022, 18, 699–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Qiu, X. A survey of transformers. AI Open 2022, 3, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Li, X.; He, L.; Yang, Y.; Cheng, G.; Tong, Y.; Ma, L.; Tao, D. TransVOD: End-to-end video object detection with spatial-temporal transformers. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2022, 45, 7853–7869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Chen, X.; Ge, N.; Feng, W.; Lu, J. Transformer-based device-type identification in heterogeneous IoT traffic. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 10, 5050–5062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Liu, S.; Liu, J.; Jiang, B.; Lu, Z.; Liu, B. ECNet: Robust malicious network traffic detection with multi-view feature and confidence mechanism. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2024, 19, 6871–6885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, M.; Lin, M.; Zhang, C.; Xu, Z. A survey on graph neural networks for intrusion detection systems: Methods, trends and challenges. Comput. Secur. 2024, 141, 103821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhou, H.; Wu, S.; Luo, X.; Wang, T.; Zhan, X.; Ma, X. FOAP: Fine-Grained Open-World android app fingerprinting. In Proceedings of the 31st USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 22), Boston, MA, USA, 10–12 August 2022; pp. 1579–1596. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, X.; Xu, L.; Yu, L.; Fang, X. MFT: A novel memory flow transformer efficient intrusion detection method. Comput. Secur. 2025, 148, 104174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ding, K.; Wang, J.; Lee, V.; Liu, H.; Pan, S. Learning strong graph neural networks with weak information. In Proceedings of the 29th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Long Beach, CA, USA, 6–10 August 2023; pp. 1559–1571. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, G.; Xiao, X.; Shen, M.; Zhang, B.; Yan, X.; Liu, Y. TCGNN: Packet-grained network traffic classification via Graph Neural Networks. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 123, 106531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, X.; He, M.; Zhang, M.; Lu, Z. Spatial-temporal graph model based on attention mechanism for anomalous IoT intrusion detection. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2023, 20, 3497–3509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Qiu, H.; Liu, Z.; Zhu, J.; Wang, Q. GLD-Net: Deep Learning to Detect DDoS Attack via Topological and Traffic Feature Fusion. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2022, 2022, 4611331. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, G.; Lv, H.; Wang, H.; Feng, G.; Li, X. Practical cyber attack detection with continuous temporal graph in dynamic network system. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2024, 19, 4851–4864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, W.W.; Layeghy, S.; Sarhan, M.; Gallagher, M.; Portmann, M. E-GraphSAGE: A Graph Neural Network based Intrusion Detection System for IoT. In Proceedings of the NOMS 2022-2022 IEEE/IFIP Network Operations and Management Symposium, Budapest, Hungary, 25–29 April 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Qu, B.; Zhao, F. ATVITSC: A novel encrypted traffic classification method based on deep learning. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2024, 19, 9374–9389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Wang, P.; Sun, Z. RTIDS: A robust transformer-based approach for intrusion detection system. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 64375–64387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manocchio, L.D.; Layeghy, S.; Lo, W.W.; Kulatilleke, G.K.; Sarhan, M.; Portmann, M. Flowtransformer: A transformer framework for flow-based network intrusion detection systems. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 241, 122564. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Y.; Yang, Y.; Shen, F.; Gao, M.; Gu, Y. Meta learning-based few-shot intrusion detection for 5G-enabled industrial internet. Complex Intell. Syst. 2024, 10, 4589–4608. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Zhu, D.; Wang, Y.; Fu, Y.; Tian, Z. GTC: GNN-transformer co-contrastive learning for self-supervised heterogeneous graph representation. Neural Netw. 2025, 181, 106645. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Lu, Z.; Wei, X.; Chen, R.; Zhang, S.; Ip, P.L. Tokenphormer: Structure-aware Multi-token Graph Transformer for Node Classification. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 25 February–4 March 2025; Volume 39, pp. 13428–13436. [Google Scholar]

- Kuang, W.; Wang, Z.; Wei, Z.; Li, Y.; Ding, B. When transformer meets large graphs: An expressive and efficient two-view architecture. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2024, 36, 5440–5452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caville, E.; Lo, W.W.; Layeghy, S.; Portmann, M. Anomal-E: A self-supervised network intrusion detection system based on graph neural networks. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2022, 258, 110030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Wu, G.; Wang, W.; Gao, X.; He, A.; Zhang, Z. Applying self-supervised learning to network intrusion detection for network flows with graph neural network. Comput. Netw. 2024, 248, 110495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Q.; Lin, X.; Xu, W.; Qi, Y.; Su, X.; Li, G.; Li, J. FeCoGraph: Label-Aware Federated Graph Contrastive Learning for Few-Shot Network Intrusion Detection. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2025, 20, 2266–2280. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.; Sun, J.; Chen, J.; Alazab, M.; Liu, Y.; Xiang, Y. TCG-IDS: Robust network intrusion detection via temporal contrastive graph learning. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2025, 20, 1475–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liu, C.; Gao, K.; Li, G.; He, K. Nagphormer+: A tokenized graph transformer with neighborhood augmentation for node classification in large graphs. IEEE Trans. Big Data 2024, 11, 2085–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarhan, M.; Layeghy, S.; Portmann, M. Towards a standard feature set for network intrusion detection system datasets. Mob. Netw. Appl. 2022, 27, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koroniotis, N.; Moustafa, N.; Sitnikova, E.; Turnbull, B. Towards the development of realistic botnet dataset in the internet of things for network forensic analytics: Bot-iot dataset. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2019, 100, 779–796. [Google Scholar]

- Sharafaldin, I.; Lashkari, A.H.; Ghorbani, A.A. Toward generating a new intrusion detection dataset and intrusion traffic characterization. In Proceedings of the ICISSP 2018-4th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy, Madeira, Portugal, 22–24 January 2018; Volume 1, pp. 108–116. [Google Scholar]

- Booij, T.M.; Chiscop, I.; Meeuwissen, E.; Moustafa, N.; Den Hartog, F.T. ToN_IoT: The role of heterogeneity and the need for standardization of features and attack types in IoT network intrusion data sets. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 9, 485–496. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, L.; Zhong, Q.; Qiu, J.; Liang, Z. E-GRACL: An IoT intrusion detection system based on graph neural networks. J. Supercomput. 2025, 81, 42. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Zhao, W.; Han, Z.; Zhao, H.; Wang, L.; He, X. N-STGAT: Spatio-temporal graph neural network based network intrusion detection for near-earth remote sensing. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3611. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.