Abstract

Early diagnosis of breast and skin cancers significantly reduces mortality rates, yet manual segmentation remains challenging due to subjective interpretation, radiologist fatigue, and irregular lesion boundaries. This study presents BAS-SegNet, a novel boundary-aware segmentation framework that addresses these limitations through an enhanced deep learning architecture. The proposed method integrates three key innovations: (1) an enhanced CNN-based architecture with a switchable feature pyramid interface, a tunable ASPP module, and consistent dropout regularization; (2) an edge-aware preprocessing pipeline using Sobel-based edge magnitude maps stacked as additional channels with geometric augmentations; (3) a boundary-aware hybrid loss combining Binary Cross-Entropy, Dice, and Focal losses with auxiliary edge supervision from morphological gradients. Experimental validation on the BUSI breast ultrasound and ISIC skin lesion datasets demonstrates superior performance, achieving Dice scores of 0.814 and 0.935, respectively, with IoU improvements of 16.3–22.4% for breast cancer and 8.8–11.5% for skin cancer compared with existing methods. The framework shows particular effectiveness under challenging ultrasound conditions where lesion boundaries are ambiguous, offering significant potential for automated clinical diagnosis support.

1. Introduction

Breast cancer is extremely prevalent and is regarded as the second leading cause of mortality in women worldwide [1]. According to data from the World Health Organization (WHO), it is a common disease and one of the leading causes of death for women internationally [2]. All over the world, there were 685,000 breast cancer-related fatalities and 2.3 million recorded cases in 2020 [3]. With an expected yearly number of more than 3 million instances reported of breast cancer and a projected annual death rate of 1 million worldwide, predictive modeling predicts an impending increase in the year 2040 [4]. It is a condition characterized by the breast cells’ unchecked multiplication and growth. Compared with normal cells, these cells expand and divide more quickly, which causes a mass or cluster to form [5]. Through a process called metastasis, the cells can spread to other areas of the human body, notably the lymph nodes. Breast cancer typically originates from cells in the glandular lobules, the milk-producing ducts, or other tissues and cells within the breast. Breast cancer is a severe health issue that affects one in eight women worldwide [5]. Nonetheless, breast cancer accounts for 19% of all malignancies in women and accounts for 30% of all forms of cancer [6].

Skin cancer, on the other hand, is the fifth most prevalent type of cancer and one of the deadliest of the current decade [7]. One of the most prevalent conditions, skin cancer accounts for almost 40% of all cancer cases and forms [8]. Globally, about 1 million cases were reported in 2018 [9]. There are several reasons why melanoma develops, including UV radiation exposure, solarium usage, and anomalies in melanocyte cells, which make the melanin pigment, which provides hair, skin, and eye color [10]. Skin cancer initially occurs in the epidermis, the upper layer of the skin. This layer can be noticed and can also be seen with the human eye [11,12]. Skin cancer is among the most diagnosed cancer types in both men and women. Classifying skin cancer as benign and malignant using dermoscopic tools is a difficult task. Skin cancer that is most deadly is a malignant tumor. Early diagnosis makes it easier to treat malignant growth. Since melanomas can move quickly from the first stage to an undetected state, they can impact organs like bone, lungs, the brain, and the liver, as well as other tissues and cells [12,13]. These deadly diseases are difficult to diagnose manually due to the lack of set standards, the need for qualified pathologists, and the subjectivity involved. According to the same patient’s diagnosis, different pathologists may come to various conclusions [14]. Hence, an automated approach is required to help radiologists. One important solution is the diagnosis of medical photos. Ultrasound, MRI, mammograms, X-rays, PET, SPCET, sonography, and optical imaging are some of the methods used to obtain medical images [15]. Different deep learning approaches have been devised by researchers over the past few years for assisting diagnosis and categorizing breast and skin cancers.

However, generalizable data with richer patterns are necessary for deep learning-based radiologist expert systems to undertake expert clinical-level work and conduct successful analyses of comparisons. In order to quantify radiographic properties, conventional computer-aided approaches depend on the detection and extraction of several radio-metric features, which are not robust against variations in tissue and location [16]. But in order to properly identify the malignant area, semantic segmentation is necessary. There is now a greater need for more reliable computer vision models and algorithms for precise segmentation due to the growing complexity of breast cancer situations. However, deep learning-based segmentation techniques have lately shown impressive performance gains in the lesion identification field [17,18].

Motivation and Contributions

Early detection can reduce the death rate from skin and breast cancers. A variety of factors, such as radiologist weariness, a lack of expertise, the subtleties of breast cancer in its early stages, and more, can significantly affect the accuracy rate during the actual diagnosis procedure, which is carried out by humans [19]. Manually identifying the attributes of the photos is time-consuming and results in extra financial expenses. Furthermore, manual detection may occasionally be inaccurate. Diagnostic medical imaging may be the most basic strategy to address these issues. To address these limitations in manual breast and skin cancer detection and improve diagnostic reliability, we propose an automated segmentation framework that leverages deep learning with advanced architectural, preprocessing, and loss function enhancements. The following are this study’s main contributions:

- We enhanced a CNN-based architecture with (i) a switchable feature pyramid interface for adaptive multi-scale fusion, (ii) an optional dense representation head for embedding learning, (iii) tunable ASPP for receptive field control, and (iv) consistent dropout regularization across classifier branches, improving modularity, generalization, and extensibility.

- We developed an edge-aware preprocessing pipeline by augmenting grayscale skin images with Sobel-based edge magnitude maps, stacked as additional channels to capture intensity and gradient cues. Applied geometric augmentations to enrich contextual and boundary-level learning.

- We propose a boundary-aware hybrid loss combining Binary Cross-Entropy (BCE), Dice, and Focal losses, with an auxiliary edge-supervision term derived from morphological gradients to enhance boundary accuracy, improving segmentation robustness and precision.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 surveys existing studies on breast and skin cancer segmentation, outlining commonly used approaches and identifying current research gaps. Section 3 illustrates the materials and methods, covering the BUSI and ISIC datasets, the proposed edge-aware preprocessing approach, the BAS-SegNet architecture, and the boundary-aware hybrid loss function. Section 4 represents quantitative results and comparisons with state-of-the-art segmentation methods. Section 5 provides a discussion of the results, with particular emphasis on the performance of the proposed framework across different imaging modalities. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper by summarizing the main findings, acknowledging limitations, and suggesting directions for future work.

2. Related Works

The following section discusses the literature on image segmentation and optimization techniques for breast cancer. Additionally, the research gaps are the basis for the technique that is proposed for this study. One of the hardest image processing challenges to solve is image segmentation, which is crucial to image analysis. Image segmentation is the process of breaking an image up into non-overlapping areas according to its properties, so that these areas appear comparable to each other and clearly different from one another [20]. Furthermore, the improvement of breast cancer pathology picture segmentation has attracted a lot of attention because of the growth of computer-aided diagnostic methods and their necessity for use in image analysis.

A computer-based diagnostic approach for automated identification and evaluation of breast masses was reported by Laishram et al. [21]. The Otsu method-based multi-level image thresholding algorithm is easy to use and efficient for locating worrisome mass lesions. The diagnostic model’s prediction accuracy was shown to be increased. A multi-threshold segmentation technique based on the Otsu approach was employed by Soliman et al. [22] in their proposed framework for processing mammography images. The tumor region segmented using the proposed segmentation technique accounted for 81% of the expert-provided ground-truth region. To extract the regions of breast tumors, Patil et al. [23] combined optimally trained Recurrent Neural Networks with an adaptive fuzzy C-mean clustering segmentation technique for region growth. Based on the Canny edge detection operator, He et al. [24] created a technique for breast image recognition. When the proposed technique was used to diagnose breast MRI pictures of patients, the true positive rate rose dramatically.

All of the existing techniques for segmenting breast images exhibit good results. While the semantic picture segmentation method is widely used, it is computationally straightforward, effective, and does not need a great deal of prior training [25]. Better segmentation was achieved by combining the attention module with the semantic segmentation notion. Zijun Sha et al. [26] proposed a thorough method for identifying the malignant region in a mammography image. Several methods, including noise reduction, CNN-based optimal segmentation, and grasshopper optimization-based feature extraction and selection, were used in the proposed technique to improve accuracy and lower the computing cost. To identify, categorize, and segment the cancerous region on mammograms, Luqman Ahmed et al. [16] primarily concentrated on deep learning-based segmentation. A preprocessing technique has also been proposed to eliminate muscle area, noise, and artifacts, which contribute to a high percentage of false positives. In order to identify and rate each gland and stroma, Zhaoxuan Ma et al. [27] gathered a dataset of 513 HR imaging tiles of primary prostate cancer. Multi-scale U-Net, two SegNet variants, and FCN-8s were evaluated in semantic segmentation of low- and high-grade cancers in this special dataset. In order to treat patients with tumors, it is crucial to diagnose lung cancer. A brand-new database that describes 15 different mediastinal anatomical frames and lymph node sizes was presented by David Bouget et al. [28]. In order to use the loss function when working with unbalanced data, a two-dimensional pipeline that connected U-Net strength to pixel-based segmentation was developed. Samudrala and Mohan [25] proposed a breast cancer image segmentation framework combining Adaptive Local Gamma Correction (ALGC) for contrast enhancement with a hybrid DenseNet-121 and Attention-based Pyramid Scene Parsing Network (Att-PSPNet). Wu et al. [29] used the Boundary-Guided Multiscale Network (BGM-Net), which was intended for breast lesion segmentation in ultrasound images. BGM-Net’s design is based on the Feature Pyramid Network (FPN) framework and includes border guiding techniques.

Agarwal [30] used the RCA-IUnet (residual cross-spatial attention-guided inception U-net) model, which was created for tumor segmentation in breast ultrasound imaging. RCA-IUnet uses the U-Net architecture, which includes aspects such as residual inception depth-wise separable convolution, a combination of pooling layers (max pooling and spectrum pooling), and cross-spatial attention filters. Chen et al. [31] used AAU-net, an adaptive attention U-net developed for the automated and robust segmentation of breast lesions in ultrasound images. They combined AAU-net with the Hybrid Adaptive Attention Module (HAAM), which included both a channel self-attention block and a spatial self-attention block. Yang et al. [32] developed the Cross-task guided network (CTG-Net), a system that merges two basic tasks in computerized breast lesion analysis: lesion segmentation and tumor classification. BO-Net, a specific boundary-oriented network designed to enhance breast tumor segmentation in ultrasound images, was implemented by Zhang et al. [33]. BO-Net uses a two-step procedure: first, a boundary-oriented module (BOM) is used to identify weak tumor borders by obtaining additional boundary maps; next, the Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling (ASPP) module is used to extract features, and finally, InvUNET, a technique for detecting breast tumors in ultrasound images, was created. InvUNET provided location-specific and channel-agnostic representation learning by combining the UNET architecture with involution layers and lightweight kernels.

For the purpose of segmenting breast ultrasound images, Lyu et al. [34] created a pyramid attention network by combining multi-scale characteristics and attention mechanisms. This architecture aggregates incremental small-size convolutions using separable convolutions to create a multi-scale receptive field. The addition of a Spatial and Channel Attention (SCA) module enhanced it much more. To simultaneously tackle breast cancer classification and segmentation problems in a cohesive framework, Zhang et al. [35] deployed SaTransformer, a semantic-aware model. Throughout the feature representation learning process, this unique method allows for useful information sharing and collaboration between the two tasks. Using several remote sensing images with different spatial resolutions, Zhiling Guo et al. [36] investigated the difficult task of semantic segmentation. To enhance the segmentation effectiveness, the super resolution technique was incorporated into the framework. According to the findings, the proposed method was appropriate for semantic segmentation, especially in cases where the resolution was out of alignment. The segmentation techniques used to predict malignancies have several challenges because of their unpredictable appearance, inaccuracy, overlapping intensity ranges, fluctuating sizes, and repeated cancer segmentation algorithms. Several research gaps have been identified by the methods currently used to separate skin cancer from breast cancer. In order to address these issues, we have put forth a novel hybrid convolutional neural network-based semantic segmentation technique for the segmentation of photos of breast and skin cancer.

3. Materials and Methods

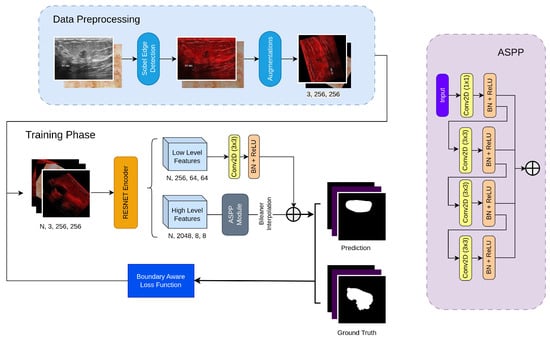

This study presents a unified framework for breast and skin cancer lesion segmentation using the BUSI breast ultrasound dataset and the ISIC skin lesion dataset. An edge-aware preprocessing pipeline was applied, where Sobel-based edge magnitude maps were stacked with the original images, alongside geometric augmentations to enhance contextual and boundary-level learning.

We developed an enhanced BAS-SegNet model featuring adaptive multi-scale fusion, a tunable ASPP module, consistent dropout regularization, and an optional dense representation head. To improve structural accuracy, a boundary-aware hybrid loss was designed by combining BCE, Dice, and Focal losses with auxiliary edge supervision. The proposed model was benchmarked against UNet, UNet++, and ResUNet. The complete methodological framework of this study is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Working methodology of the proposed framework.

3.1. BUSI Dataset

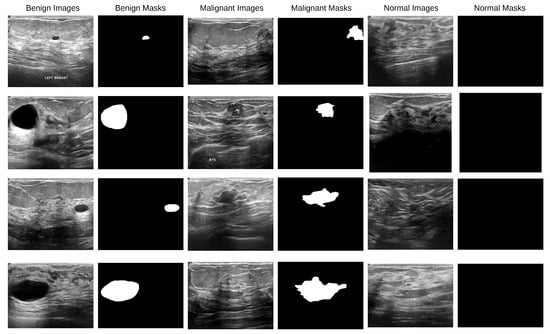

A total of 780 ultrasound images obtained at Baheya Hospital in Cairo, Egypt, using LOGIQ E9 and LOGIQ E9 Agile ultrasound scanners are included in the Breast Cancer Ultrasound Images (BUSI) dataset [37]. Women aged 25 to 75 years old had their breast ultrasound images included in the baseline data. There were 600 female patients. All of the images in the collection, moreover, are saved as PNG files and have an average resolution of 500 × 500 pixels. A binary ground-truth mask that identifies tumor locations is included with each image, and the images have been divided into three categories: normal (133 photos), benign (437 images), and malignant (210 images). With a significant number of ultrasound pictures classified as normal, benign, and malignant cases of various nodule sizes and shapes, the BUSI dataset is a useful and difficult resource for breast lesion segmentation research. Figure 2 displays the data sample.

Figure 2.

BUSI dataset images along with their corresponding binary ground-truth masks.

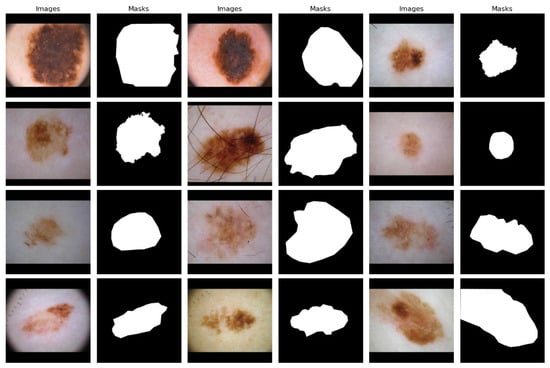

3.2. ISIC 2016 Dataset

A typical combination of photos showing benign and malignant skin lesions can be found in the second dataset [38]. With about 900 photos in the training set and about 350 in the test set, the dataset was divided into training and test sets at random. The JPEG file format is used for every single picture. The initial photo was used as training data for lesion segmentation, together with the expert manual tracing of the lesion boundaries in the form of a binary mask, where pixels with values of 255 are regarded as being inside the lesion area and pixels with values of 0 as being outside. In Figure 3, a data sample is displayed.

Figure 3.

ISIC dataset images along with their corresponding binary ground-truth masks.

3.3. Data Preprocessing

3.3.1. Sobel Edge Augmentation

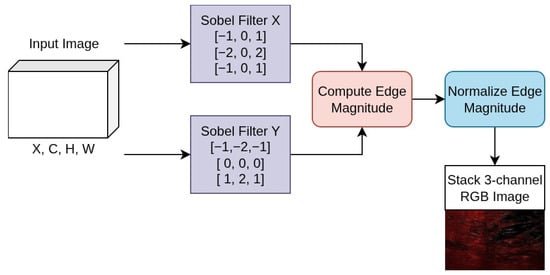

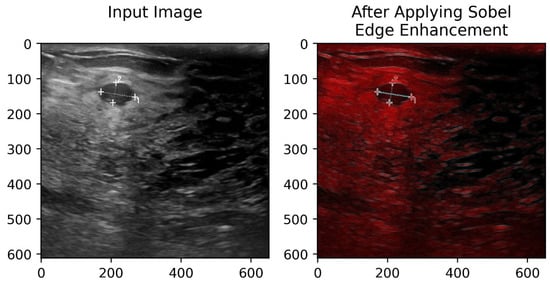

In order to extract important gradient details from the input images, the model starts with a Sobel-based edge enhancement [39] layer. The Sobel operator is applied to emphasize lesion boundaries by detecting prominent intensity changes that are often difficult to distinguish in breast ultrasound and skin lesion images. By incorporating these edge maps as additional input channels, the network is encouraged to focus on boundary-related features, leading to more accurate segmentation, particularly in areas with low contrast and complex or irregular lesion shapes. This step helps the network focus more effectively on key structural details, such as edges and contours, which is particularly important for distinguishing between different types of distractions.

Sobel is a directional differential operator based on an odd-size template; the mathematical formulas of Sobel operation are well described in [40]. The expressions of formula are as follows (Equations (1) and (2)):

Equations (3) and (4) represent the Sobel convolution template:

The first stage in the Sobel calculation process is to partition the edge detection image into matrix form (Equation (5)):

Divide the template’s horizontal and vertical directions by one another, and then divide the vertical and horizontal directions by one another, . Gradient size calculation is shown in Equation (6):

Equation (7) provides the formula for determining the gradient direction:

When is equal to zero, there is a vertical edge on behalf of the image, and the left side is darker than the right side.

Sobel developed the weighted local average, which can further reduce noise in addition to influencing image edge recognition, but the edge is wider. The basic idea of the Sobel operator algorithm is as follows: because the edge of the image is located in a place in which the brightness changes significantly, depending on the precise steps for the edge, the gray value of pixels in the vicinity of the pixel surpasses a predetermined threshold [40].

To better locate edge information from the feature maps, we designed an attention module that enhances edge response. Initially, the module applies horizontal and vertical Sobel operators to the feature map individually to obtain edge gradient maps. Then, it computes edge intensities from these two gradient maps to generate a new feature map representing the edge strength at each pixel. Subsequently, the feature map with edge intensities undergoes a pooling operation. Finally, the weight vector obtained after passing through fully connected layers is applied to the original image via element-wise multiplication. This application of calculated weights across each channel of the feature map amplifies the response of important channels while suppressing that of less important ones, as detailed in Figure 4. The application of Sobel edge enhancement is further illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 4.

Channel attention mechanism for edge-enhanced feature maps.

Figure 5.

Input image and its edge representation obtained using the Sobel operator.

3.3.2. Geometric Augmentation

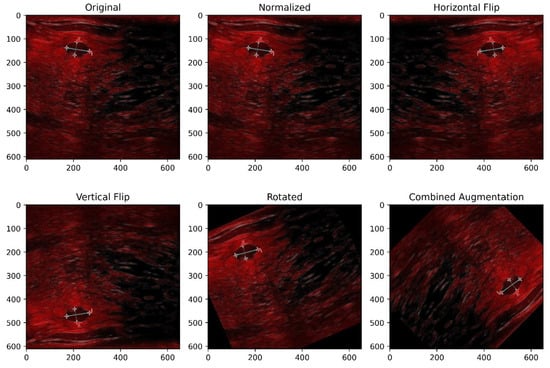

Finally, geometric augmentation works by randomly altering the shape or position of training images. To be effective, each random transformation needs to meet certain conditions [41]: (1) it should be quick enough to run during training without slowing the process; (2) the amount of change should be limited to avoid overly distorting the image; (3) the transformations should be varied enough to add diversity, yet still realistic so that they do not create meaningless or misleading shapes, since the right type of geometric change can depend on the object class. Common examples include adjustments to size and orientation, which help the model adapt to different perspectives.

In this study, we applied normalization, horizontal flipping, vertical flipping, and random rotation as part of our geometric data augmentation strategy. The applied augmentation processes are illustrated in Figure 6. These techniques were selected to increase the model’s resilience by exposing it to variations in image orientation and intensity distribution. Such transformations help the segmentation model generalize better to unseen data, particularly when objects may appear in different positions, alignments, or lighting conditions in real scenarios.

Figure 6.

Illustration of applied geometric augmentation techniques.

3.4. Proposed BAS-SegNet Model

The proposed model, BAS-SegNet (Boundary-Aware Sobel-Enhanced Segmentation Network), is a modified semantic segmentation framework designed to improve lesion boundary delineation in breast ultrasound images. The architecture is based on a convolutional neural network but integrates structural modifications that enhance both contextual feature extraction and multi-scale representation learning. The model follows an encoder–decoder paradigm, where the encoder captures hierarchical semantic information and the decoder reconstructs fine spatial details for accurate segmentation outputs.

The encoder is based on a ResNet-50 backbone pretrained on ImageNet, which enables effective transfer learning for medical imaging tasks. The encoder processes the input image through an initial convolutional stem followed by four residual stages. These layers progressively reduce the spatial resolution while enriching semantic abstraction. Four levels of feature maps are extracted: low-level features from the early residual block (stride 4) and progressively deeper semantic features up to stride 32. Such a hierarchical feature set provides a strong foundation for combining both global and local contextual information.

To ensure robust model performance, a hyperparameter tuning approach was adopted to determine the best training configuration. The network architecture was kept unchanged, while key training parameters such as batch size, learning rate, weight decay, and dropout rate were carefully evaluated through validation experiments. All models were trained using the Adam optimizer, and the final settings were selected based on validation performance and stable convergence during training.

To capture multi-scale semantic context and improve the receptive field, an Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling (ASPP) module is applied to the deepest encoder features. The ASPP consists of five parallel branches: (i) global average pooling followed by a 1 × 1 convolution, (ii) a 1 × 1 convolution for local refinement, and (iii–v) three dilated convolutions with dilation rates of 12, 24, and 36. These branches extract semantic representations at different scales, and their outputs are concatenated to form a rich multi-scale feature map. This aggregated representation is further refined through a 3 × 3 convolutional block with normalization, non-linearity, and dropout regularization to prevent overfitting.

The decoder integrates the multi-scale ASPP features with low-level features from the encoder to improve spatial localization of breast lesions. Specifically, the low-level feature map from the first residual stage is projected through a 1 × 1 convolution and fused with the upsampled ASPP output via bilinear interpolation. The concatenated feature maps are then passed through a sequence of convolutional, normalization, activation, and dropout layers, which progressively refine the feature representation. Finally, a 1 × 1 convolution produces the segmentation logits, which are upsampled to the original input resolution. This design allows the decoder to preserve fine-grained structural details while leveraging the deep semantic context captured by the encoder and ASPP.

The model also includes an optional representation head that can be enabled for auxiliary representation learning. Although not used in this study, this head can facilitate downstream tasks such as feature embedding or contrastive learning.

The overall output of the BAS-SegNet model is a high-resolution segmentation mask of size equal to the input image. This enables precise delineation of malignant lesions and benign in breast ultrasound images, addressing challenges such as low contrast and irregular tumor boundaries. A detailed pseudocode of the model workflow and a comprehensive model summary highlighting the number of parameters, layer configurations, and output dimensions are provided in Algorithm 1 and Table 1 for clarity and reproducibility.

| Algorithm 1: Workflow of the proposed BAS-SegNet model. |

|

Table 1.

Parameter specifications of proposed the BAS-SegNet architecture.

3.5. Proposed Boundary-Aware Hybrid Loss

In medical image segmentation, especially in breast cancer lesion delineation, accurate boundary localization is essential to robust and clinically reliable outcomes. Traditional pixel-wise losses such as Binary Cross-Entropy (BCE) primarily focus on global pixel classification but often fail to emphasize fine structural details at the lesion boundaries. To overcome this limitation, we propose a boundary-aware hybrid loss function that combines BCE, Dice, and Focal losses with an auxiliary edge-supervision term derived from morphological gradients, thereby improving both segmentation robustness and boundary precision. The standard BCE loss is defined as

where denotes the predicted logits, is the ground-truth label, and represents the sigmoid function. While BCE ensures pixel-level classification accuracy, it does not explicitly address class imbalance or structural consistency.

To better handle imbalance between foreground and background regions, we incorporate the Dice loss:

where is a small constant for numerical stability. Dice loss enforces overlap maximization between predicted masks and ground truth, thus improving segmentation quality in small or irregular regions. Additionally, we integrate the Focal loss:

This loss down-weights easy negatives and emphasizes hard-to-classify pixels, making it particularly effective in medical segmentation, where lesions occupy small proportions of the image.

We define an enhanced segmentation loss as a weighted combination:

where , , and are balancing coefficients used to weight the individual components of the enhanced segmentation loss. The loss coefficients were chosen based on standard practices in boundary-aware medical image segmentation. Equal weighting was used for the BCE, Dice, and Focal terms, while the boundary supervision coefficient was fixed to moderately emphasize boundary pixels without dominating the overall loss. This configuration ensured stable convergence and consistent performance across both datasets. To further enhance structural accuracy at lesion boundaries, we introduce an auxiliary boundary supervision term. Using morphological gradient operations on the ground-truth masks, we generate a boundary map and enforce additional BCE loss specifically on boundary pixels:

where B denotes the set of boundary pixels.

Finally, the boundary-aware hybrid loss is formulated as

where controls the relative importance of boundary supervision.

The implementation of the proposed loss integrates morphological edge extraction with enhanced segmentation loss. The boundary mask is computed using morphological erosion and subtraction, and the boundary-specific BCE term is applied to enforce sharp and precise delineations.

3.6. Performance Evaluation Metrics

The models are used to forecast breast cancer segmentation masks for the test set after being trained on the training set. A number of performance indicators, including true positive (TP), false positive (FP), true negative (TN), false positive (FP), and false negative (FN) values, are then used to assess these anticipated masks. Among these assessment metrics are those listed below.

To evaluate how comparable the anticipated and ground-truth masks are, the Dice coefficient is used. This measure provides information on the degree of agreement between the two masks by quantifying the ratio of twice the intersection to the sum of their sizes.

The Jaccard index, commonly known as the Mean Intersection over Union (IoU), measures how much the ground-truth mask and the anticipated segmentation mask overlap. This metric provides a thorough assessment of segmentation accuracy by calculating the ratio of the intersection to the union of the two masks.

The precision metric quantifies the percentage of actual positive instances (breast cancer pixels) that were anticipated to be positive. It measures how well the program can detect breast cancer pixels while avoiding a high number of false positives.

Recall quantifies the fraction of genuine positive instances (breast cancer pixels) that the model correctly identifies.

The F1-score is a composite accuracy metric that considers memory and precision. Both false positives and false negatives are necessary for the calculation.

4. Experimental Results

Details of the implementation of a semantic segmentation system are covered in this part, along with the specifics of the experiments conducted on the BUSI and ISIC datasets. By optimizing the cutting-edge segmentation deep learning frameworks, the two dataset variations are utilized to fully evaluate the proposed preprocessing method.

4.1. Experimental Setup

The complete dataset was split into a training set and a test set in order to train and assess the models’ performance. The models had a batch size of 16 and were trained over 200 epochs. The AdamW optimizer was used to compute the loss. During training, a dropout technique was applied to mitigate the risk of overfitting. The experiment was conducted using the Python (version 3.12) programming language on the Kaggle platform, with the system configuration being Windows 11 Pro, Core(TM) i7-8650U CPU @ 1.90GHz (Intel Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA), NVIDIA Tesla P100 GPU (NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA), and CUDA Version 12.5.

4.2. Results of Breast Cancer Segmentation

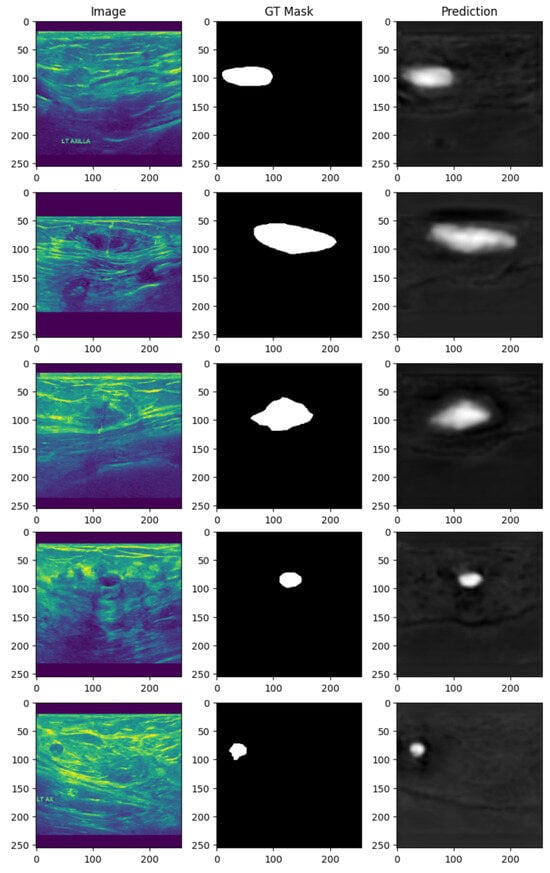

Figure 7 illustrates the results of segmentation on breast cancer ultrasound images using the proposed BAS-SegNet framework. The first column presents the original ultrasound images, while the matching ground-truth (GT) masks, manually annotated by medical professionals, are displayed in the second column. The third column displays the predicted segmentation masks generated by the proposed model.

Figure 7.

Breast cancer ultrasound segmentation results using the proposed BAS-SegNet model.

By visually comparing the predicted masks with the ground-truth annotations, it is evident that the proposed BAS-SegNet effectively delineates tumor boundaries, even in cases where the lesions exhibit irregular shapes or low contrast with surrounding tissues. The model demonstrates strong capability to capture both global structural patterns and fine-grained boundary details, highlighting the contribution of Sobel-based edge augmentation and the boundary-aware hybrid loss to enhancing segmentation precision.

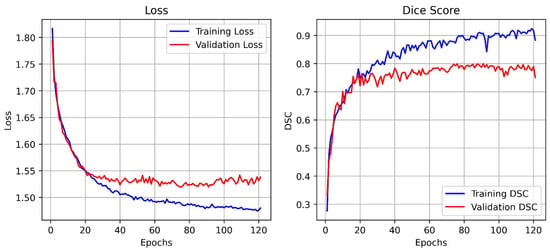

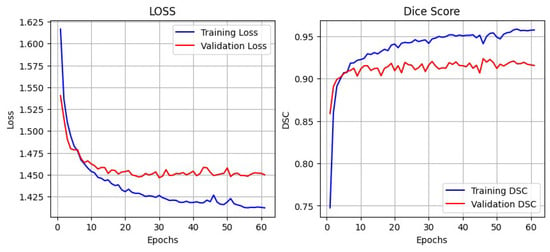

Figure 8 illustrates the training and validation performance curves of the proposed BAS-SegNet model on the BUSI dataset. The left plot depicts the loss curves across training epochs, while the right plot shows the corresponding Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC) scores. As training progresses, both training and validation losses exhibit a steady decline, with the validation loss stabilizing after approximately 40 epochs, indicating effective convergence of the model.

Figure 8.

Training and validation loss and DSC curves of the proposed BAS-SegNet model.

On the other hand, the Dice score curves demonstrate a rapid increase during the early training phase, followed by gradual stabilization. The training DSC consistently improves and reaches values above 0.90, while the validation DSC stabilizes around 0.78–0.80, reflecting the strong generalization capability of the model without significant overfitting. These results validate the contribution of the edge-aware preprocessing and boundary-aware hybrid loss to achieving accurate lesion boundary delineation and robust segmentation performance.

4.3. Results of Skin Cancer Segmentation

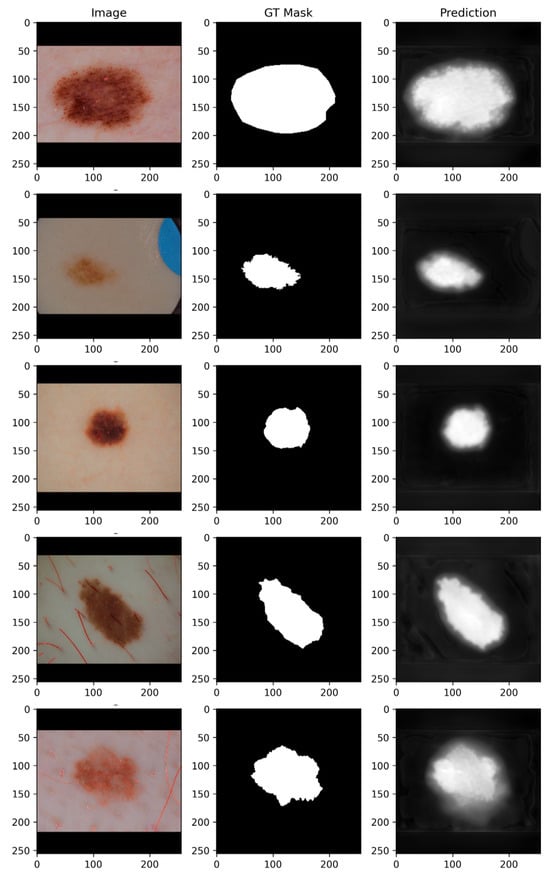

Figure 9 presents the segmentation outcomes for skin cancer lesions from the ISIC dataset. The original dermoscopic images are shown in the first column, while the second column illustrates the corresponding GT masks manually annotated by dermatology experts. The third column shows the predicted segmentation masks produced by the proposed BAS-SegNet model.

Figure 9.

Skin cancer segmentation results using the proposed BAS-SegNet framework.

By comparing the GT masks with the predicted masks, it is evident that the proposed model demonstrates a strong ability to delineate lesion boundaries across diverse lesion types and morphologies. For small, well-localized lesions, the model effectively suppresses background noise and achieves precise localization. In cases of irregular or diffuse lesions, the BAS-SegNet captures both the overall lesion structure and fine-grained boundary details, although minor boundary smoothing can be observed in regions with low contrast against the surrounding skin.

The inclusion of Sobel-based edge augmentation enhances the model’s ability to recognize sharp lesion edges, while the boundary-aware hybrid loss improves robustness in handling ambiguous borders, particularly in lesions with heterogeneous textures. These findings demonstrate the flexibility of the proposed segmentation framework to varying lesion sizes, shapes, and intensity distributions, underscoring its clinical potential for supporting automated melanoma detection and classification tasks.

Figure 10 illustrates the training and validation performance curves of the proposed BAS-SegNet model on the ISIC dataset. The left plot presents the training and validation loss trends across epochs, while the right plot shows the corresponding DSC scores. As training progresses, both training and validation losses demonstrate a consistent decline, with the validation loss stabilizing after approximately 20–25 epochs, indicating effective convergence of the model.

Figure 10.

Training and validation loss and DSC curves of the proposed BAS-SegNet model on the ISIC dataset.

Meanwhile, the Dice score curves show a steep increase during the initial training phase, followed by gradual stabilization. The training DSC continues to improve, reaching values above 0.95, while the validation DSC stabilizes around 0.91–0.92, highlighting strong generalization without evidence of overfitting. These results confirm the effectiveness of the proposed edge-aware preprocessing and boundary-aware hybrid loss in enhancing lesion segmentation robustness and boundary precision.

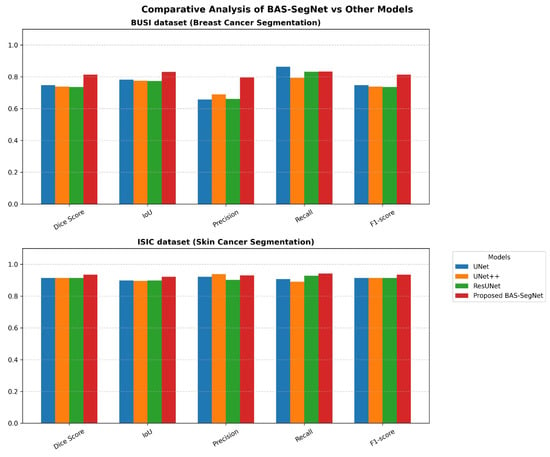

4.4. Comparison with Other Models

The proposed BAS-SegNet model’s various components are analyzed through a systematic series of ablation experiments. The performance was assessed by the study of three widely used traditional segmentation models, UNet, UNet++, and ResUNet, for both breast cancer segmentation and skin cancer segmentation. As shown in Table 2 and illustrated in Figure 11, these studies yielded insightful information on how each component contributed to the overall segmentation performance.

Table 2.

Comparative analysis of BAS-SegNet on both BUSI and ISIC datasets.

Figure 11.

Performance comparison of proposed BAS-SegNet and other applied models on BUSI and ISIC datasets.

The comparative analysis demonstrates the effectiveness of the proposed BAS-SegNet architecture across both datasets. On the BUSI breast cancer dataset, BAS-SegNet achieves a Dice score of 0.814, representing 8.97–10.45% improvements over the baseline models (UNet, UNet++, and ResUNet). The precision metric shows particularly notable gains at 0.796 compared with 0.658–0.689 for baseline models, indicating enhanced ability to minimize false positive predictions while maintaining competitive recall at 0.833.

For the ISIC skin cancer dataset, BAS-SegNet achieves a Dice score of 0.935 vs. 0.914 for all baseline models, with more pronounced Jaccard index improvements (0.922 vs. 0.896–0.898). The performance gap is larger on the BUSI dataset (6.7–7.7 percentage points) compared with ISIC (2.1 percentage points), suggesting that the proposed edge-aware preprocessing and boundary-aware hybrid loss provide greater benefits in challenging ultrasound imaging where boundaries are more ambiguous. The consistent F1-score improvements across both datasets (0.814 vs. 0.737–0.747 for BUSI and 0.935 vs. 0.914 for ISIC) validate the robustness of the proposed architectural modifications and loss function design.

5. Discussion

The segmentation of cancerous lesions in medical images is a complex task due to irregular boundaries, varying contrast levels, and the presence of artifacts in different imaging modalities. The challenge becomes particularly pronounced in breast ultrasound images, where acoustic shadows and speckle noise can obscure lesion boundaries, while dermoscopic images may exhibit similar texture patterns between lesions and surrounding healthy tissue.

For both breast cancer and skin segmentation, Table 3 depicts a thorough comparison of the proposed BAS-SegNet model with several current state-of-the-art techniques. The table offers insightful information on how well various methods separate intricate anatomical features under various imaging scenarios, demonstrating how architectural enhancements and specialized loss functions can address the inherent challenges in medical image analysis.

Table 3.

Comparative analysis between the proposed method and recent state-of-the-art techniques on BUSI (breast cancer) and ISIC 2016 (skin cancer) datasets.

The comparative analysis of Table 3 identifies distinct performance patterns across imaging modalities. For breast ultrasound segmentation, the proposed BAS-SegNet achieves a Dice score of 0.814, with more substantial IoU improvements reaching 0.831 compared with 0.679–0.714 in existing methods (16.3–22.4% relative improvement). While reference [33] shows higher precision (0.852), the proposed method maintains superior recall (0.833), indicating a greater reduction in false negative rates, which is clinically advantageous for screening applications.

On the ISIC dataset, performance gains are more modest but consistent, achieving a 0.935 Dice score versus the range 0.902–0.915 of comparative methods. The IoU metric shows pronounced gains at 0.922 compared with 0.827–0.847 (8.8–11.5% improvement). The balanced precision–recall performance (0.929/0.941) demonstrates the effective handling of both false positive and negative reduction in dermoscopic images.

The differential improvements between the datasets suggest that the proposed enhancements are particularly effective under challenging ultrasound imaging conditions where boundaries are inherently ambiguous due to acoustic properties. The consistent improvements across multiple metrics indicate robust algorithmic advancement rather than metric-specific optimization.

6. Conclusions

This study presents BAS-SegNet, a boundary-aware segmentation framework that addresses critical challenges in automated breast and skin cancer lesion delineation through three key technical contributions. The proposed architecture with a switchable feature pyramid interface and a tunable ASPP module provides adaptive multi-scale feature extraction, effectively handling lesions with varying sizes and morphological characteristics. The edge-aware preprocessing pipeline augments images with Sobel-based edge magnitude maps, capturing both intensity and gradient information essential to accurate boundary delineation. The boundary-aware hybrid loss function combines BCE, Dice, and Focal losses with auxiliary edge supervision, balancing pixel-level accuracy with structural consistency. Experimental validation demonstrates robust performance across two distinct datasets. On the BUSI breast ultrasound dataset, BAS-SegNet achieves a Dice score of 0.814 with IoU improvements of 16.3–22.4% compared with existing methods. The ISIC skin cancer dataset results show a Dice score of 0.935 with IoU enhancements of 8.8–11.5%. The more substantial gains on ultrasound images indicate that the proposed enhancements provide greater benefits under challenging imaging conditions where lesion boundaries are inherently ambiguous. However, comparative evaluation against state-of-the-art models demonstrates consistent performance improvements, confirming the overall effectiveness of the proposed BAS-SegNet framework. However, this study did not include explicit component-wise ablation experiments to individually quantify the contributions of the enhanced CNN architecture, Sobel-based preprocessing, and boundary-aware hybrid loss. This is a limitation of the current work, and future studies will conduct systematic ablation analyses to isolate and measure the impact of each component. Additional future directions include extending the framework to other cancer types and imaging modalities and validating its performance on multi-institutional datasets. Overall, BAS-SegNet shows strong potential as a computer-aided diagnosis tool for improving lesion boundary delineation and supporting clinical decision making.

Author Contributions

Methodology, M.S.H.; Software, M.S.H.; Formal analysis, M.S.H.; Resources, M.S.H.; Data curation, M.S.H.; Writing—original draft, M.S.H.; Writing—review & editing, H.Z.; Supervision, H.Z.; Project administration, H.Z.; Funding acquisition, H.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (62071057 and 62302036), the National Key Research and Development Program of China under Grant (2022YFB3103800), and the Aeronautical Science Foundation of China (2019ZG073001).

Data Availability Statement

The proposed and implemented model code can be found here: https://github.com/sabbirpuspo/BAS-SegNet-for-Cancer-Images-Segmentation, accessed on 29 November 2025.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abunasser, B.S.; Daud, S.M.; Zaqout, I.S.; Abu-Naser, S.S. Convolution neural network for breast cancer detection and classification–final results. J. Theor. Appl. Inf. Technol. 2023, 101, 1. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Breast Cancer. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Islami, F.; Miller, K.D.; Siegel, R.L.; Zheng, Z.; Zhao, J.; Han, X.; Ma, J.; Jemal, A.; Yabroff, K.R. National and state estimates of lost earnings from cancer deaths in the United States. JAMA Oncol. 2019, 5, e191460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Global Breast Cancer Initiative Implementation Framework: Assessing, Strengthening and Scaling-Up of Services for the Early Detection and Management of Breast Cancer; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M.R.; Rahman, M.M.; Ali, M.S.; Nafi, A.A.N.; Alam, M.S.; Godder, T.K.; Miah, M.S.; Islam, M.K. Enhancing breast cancer segmentation and classification: An Ensemble Deep Convolutional Neural Network and U-net approach on ultrasound images. Mach. Learn. Appl. 2024, 16, 100555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferlay, J.; Ervik, M.; Lam, F.; Colombet, M.; Mery, L.; Piñeros, M.; Znaor, A.; Soerjomataram, I.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2019.

- Hasan, N.; Nadaf, A.; Imran, M.; Jiba, U.; Sheikh, A.; Almalki, W.H.; Almujri, S.S.; Mohammed, Y.H.; Kesharwani, P.; Ahmad, F.J. Skin cancer: Understanding the journey of transformation from conventional to advanced treatment approaches. Mol. Cancer 2023, 22, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, N.; Bussmann, E.; Shah, A.; Dean, J.; Papanikolopoulos, N. Computer Aided Diagnosis of Skin Lesions from Morphological Features. University Digital Conservancy, Technical Report 18-014. 2018. Available online: https://conservancy.umn.edu/items/ce811c4c-ce47-4910-86c1-cb47c30bb753 (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- Garg, R.; Maheshwari, S.; Shukla, A. Decision support system for detection and classification of skin cancer using CNN. In Innovations in Computational Intelligence and Computer Vision; Sharma, M.K., Dhaka, V.S., Perumal, T., Dey, N., Tavares, J.M.R.S., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; Volume 1189, pp. 65–75. [Google Scholar]

- Cassano, R.; Cuconato, M.; Calviello, G.; Serini, S.; Trombino, S. Recent advances in nanotechnology for the treatment of melanoma. Molecules 2021, 26, 785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassem, M.A.; Hosny, K.M.; Fouad, M.M. Skin lesions classification into eight classes for ISIC 2019 using deep convolutional neural network and transfer learning. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 114822–114832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, H.C.; Turk, V.; Khoshelham, K.; Kaya, S. InSiNet: A deep convolutional approach to skin cancer detection and segmentation. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 2022, 60, 643–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop, T.D.; Diaconeasa, Z. Recent advances in phenolic metabolites and skin cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umer, M.J.; Sharif, M.; Kadry, S.; Alharbi, A. Multi-class classification of breast cancer using 6B-net with deep feature fusion and selection method. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelrahman, L.; Al Ghamdi, M.; Collado-Mesa, F.; Abdel-Mottaleb, M. Convolutional neural networks for breast cancer detection in mammography: A survey. Comput. Biol. Med. 2021, 131, 104248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, L.; Iqbal, M.M.; Aldabbas, H.; Khalid, S.; Saleem, Y.; Saeed, S. Images data practices for Semantic Segmentation of Breast Cancer using Deep Neural Network. J. Ambient Intell. Humaniz. Computing. 2020, 14, 15227–15243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hekal, A.A.; Elnakib, A.; Moustafa, H.E.-D.; Amer, H.M. Breast Cancer Segmentation from Ultrasound Images Using Deep Dual-Decoder Technology with Attention Network. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 10087–10101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, J.; Sharif, M.; Fernandes, S.L.; Wang, S.; Saba, T.; Khan, A.R. Breast microscopic cancer segmentation and classification using unique 4-qubit-quantum model. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2022, 85, 1926–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajakumari, R.; Kalaivani, L. Breast cancer detection and classification using deep CNN techniques. Intell. Autom. Soft Comput. 2022, 32, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wang, R.; Zhao, D.; Yu, F.; Heidari, A.A.; Xu, Z.; Chen, H.; Algarni, A.D.; Elmannai, H.; Xu, S. Multi-level threshold segmentation framework for breast cancer images using enhanced differential evolution. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2023, 80, 104373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laishram, R.; Rabidas, R. WDO optimized detection for mammographic masses and its diagnosis: A unified CAD system. Appl. Soft Comput. 2021, 110, 107620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, N.F.; Ali, N.S.; Aly, M.I.; Algarni, A.D.; El-Shafai, W.; El-Samie, F.E.A. An Efficient Breast Cancer Detection Framework for Medical Diagnosis Applications. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2022, 70, 1315–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, R.S.; Biradar, N.; Pawar, R. A new automated segmentation and classification of mammogram images. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2022, 81, 7783–7816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Pan, R. Automatic segmentation algorithm for magnetic resonance imaging in prediction of breast tumour histological grading. Expert Syst. 2021, 40, e12846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samudrala, S.; Mohan, C.K. Semantic segmentation of breast cancer images using DenseNet with proposed PSPNet. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2023, 83, 46037–46063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, Z.; Hu, L.; Rouyendegh, B.D. Deep learning and optimization algorithms for automatic breast cancer detection. Int. J. Imaging Syst. Technol. 2020, 30, 495–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Li, J.; Salemi, H.; Arnold, C.; Knudsen, B.S.; Gertych, A.; Ing, N. Semantic segmentation for prostate cancer grading by convolutional neural networks. In Medical Imaging 2018: Digital Pathology; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2018; Volume 10581. [Google Scholar]

- Bouget, D.; Jørgensen, A.; Kiss, G.; Leira, H.O.; Lango, T. Semantic segmentation and detection of mediastinal lymph nodes and anatomical structures in CT data for lung cancer staging. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 2019, 14, 977–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, R.; Zhu, L.; Wang, W.; Wang, S.; Xie, H.; Cheng, G.; Wang, F.L.; He, X.; Zhang, H. BGM-Net: Boundary-guided multiscale network for breast lesion segmentation in ultrasound. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 698334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Punn, N.S.; Agarwal, S. RCA-IUnet: A residual cross-spatial attention-guided inception U-Net model for tumor segmentation in breast ultrasound imaging. Mach. Vis. Appl. 2022, 33, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Li, L.; Dai, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yap, M.H. AAU-Net: An adaptive attention U-Net for breast lesions segmentation in ultrasound images. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2023, 42, 1289–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Suzuki, A.; Ye, J.; Nosato, H.; Izumori, A.; Sakanashi, H. CTG-Net: Cross-task guided network for breast ultrasound diagnosis. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0271106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Huang, A.; Yang, D.; Xu, R. Boundary-oriented network for automatic breast tumor segmentation in ultrasound images. Ultrason. Imaging 2023, 45, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Jiang, X.; Liu, J.; Zhao, X.; Zhu, X. AMS-PAN: Breast ultrasound image segmentation model combining attention mechanism and multi-scale features. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2023, 81, 104425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, H.; Xu, S. SaTransformer: Semantic-aware transformer for breast cancer classification and segmentation. IET Image Process. 2023, 17, 3789–3800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Wu, G.; Song, X.; Yuan, W.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, H.; Shi, X.; Xu, M.; Xu, Y.; Shibasaki, R.; et al. Super-resolution integrated building semantic segmentation for multisource remote sensing imagery. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 99381–99397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dhabyani, W.; Gomaa, M.; Khaled, H.; Fahmy, A. Dataset of breast ultrasound images. Data Brief 2020, 28, 104863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISIC 2016 Original Dataset. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/mahmudulhasantasin/isic-2016-original-dataset (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Geng, J.; Xiong, W.; Yin, H.; Yi, X.; Wang, S.; Li, X. EdgeFlow: Combining Local Feature Enhancement and Sobel-Based Channel Attention for Optical Flow Estimation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Image Processing, Computer Vision and Machine Learning (ICICML), Shenzhen, China, 22–24 November 2024; pp. 1328–1332. [Google Scholar]

- Jin-Yu, Z.; Yan, C.; Xian-Xiang, H. Edge detection of images based on improved Sobel operator and genetic algorithms. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Image Analysis and Signal Processing, Linhai, China, 11–12 April 2009; pp. 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.-C.; Yang, Y.-L.; Hall, P. Geometric and Textural Augmentation for Domain Gap Reduction. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 14320–14330. [Google Scholar]

- Shareef, B.; Vakanski, A.; Freer, P.E.; Xian, M. ESTAN: Enhanced small tumor-aware network for breast ultrasound image segmentation. Healthcare 2022, 10, 2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavan, T.; Prajapati, K. InvUNET: Involuted UNET for breast tumor segmentation from ultrasound. In Artificial Intelligence in Medicine, AIME; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 283–290. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, S.; Zhao, H.; Shi, F.; Cheng, X.; Wang, M.; Ma, Y.; Xiang, D.; Zhu, W.; Chen, X. CPFNet: Context pyramid fusion network for medical image segmentation. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2020, 39, 3008–3018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, D.; Dong, C.; Xu, S.; Yan, Q.; Li, Z.; Zhang, C.; Luo, N. Ms RED: A novel multi-scale residual encoding and decoding network for skin lesion segmentation. Med. Image Anal. 2022, 75, 102293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Chen, S.; Chen, G.; Wang, W.; Lei, B.; Wen, Z. FAT-Net: Feature adaptive transformers for automated skin lesion segmentation. Med. Image Anal. 2022, 76, 102327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Siddiquee, M.M.R.; Tajbakhsh, N.; Liang, J. UNet++: A nested U-Net architecture for medical image segmentation. In Deep Learning in Medical Image Analysis and Multimodal Learning for Clinical Decision Support; Springer: Granada, Spain, 2018; pp. 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, H.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, X.; Tian, Q.; Wang, M. Swin-Unet: U-Net-like pure transformer for medical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2022 Workshops, ECCV 2022, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; pp. 205–218. [Google Scholar]

- Oktay, O.; Schlemper, J.; Folgoc, L.L.; Lee, M.; Heinrich, M.; Misawa, K.; Mori, K.; McDonagh, S.; Hammerla, N.Y.; Kainz, B.; et al. Attention U-Net: Learning where to look for the pancreas. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.03999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.