Author Contributions

M.H., I.G., J.P. and Z.K., conceptualization, methodology, development, writing original draft, editing; M.H. and I.G., conceptualization, methodology, development, writing original draft, supervision; Z.K., editing, validation, visualization; J.P. and I.G., editing, validation, visualization. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the identification, screening and inclusion of studies.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the identification, screening and inclusion of studies.

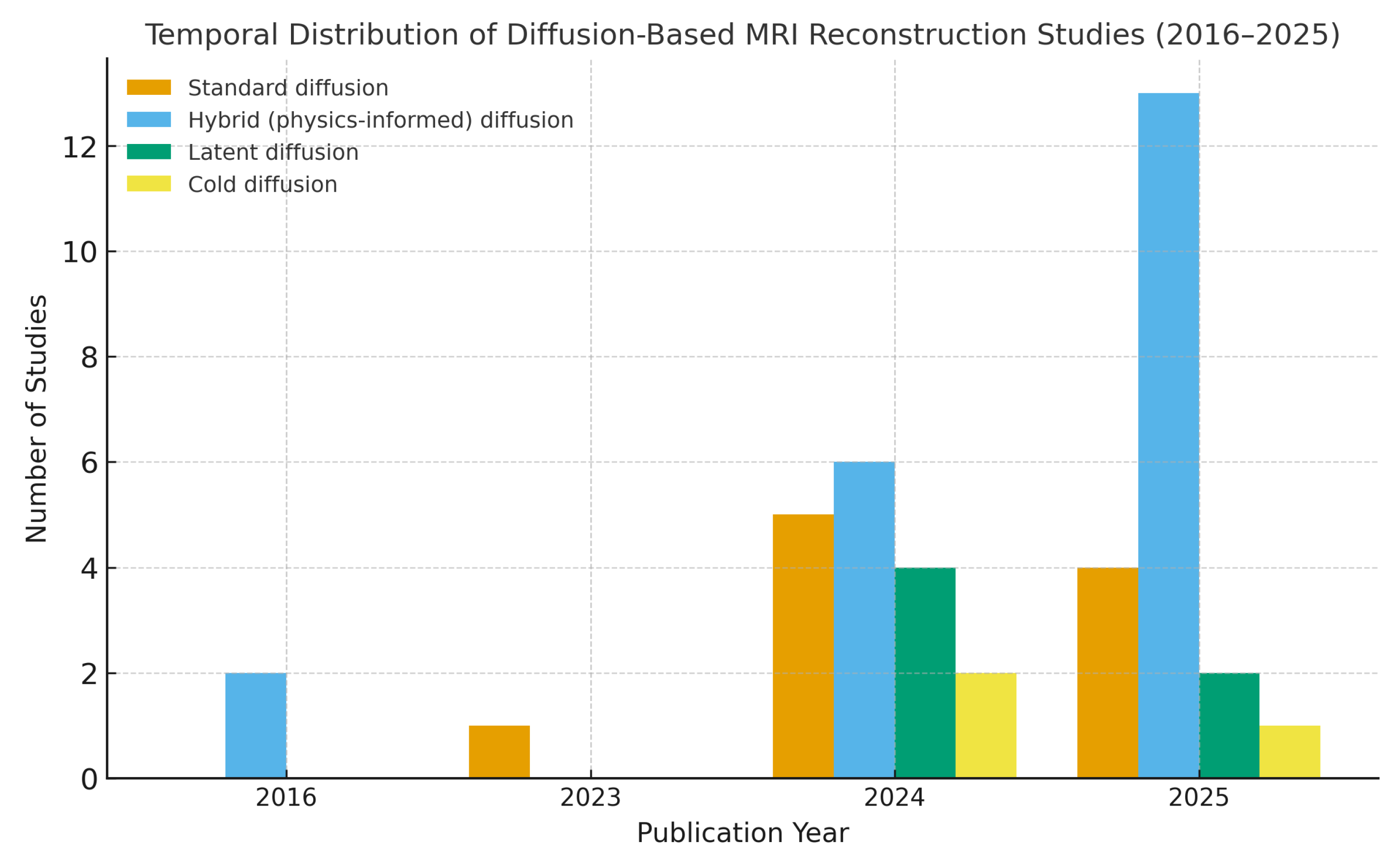

Figure 2.

The temporal distribution of 40 reviewed studies categorized by model type. A clear increase in publications after 2023 highlights the rapid expansion of the field.

Figure 2.

The temporal distribution of 40 reviewed studies categorized by model type. A clear increase in publications after 2023 highlights the rapid expansion of the field.

Figure 3.

Illustration of classification scheme of diffusion-based MRI reconstruction studies. All reviewed studies are systematically categorized along three dimensions: (1) model type (standard, hybrid, latent and cold diffusion), (2) application domain (accelerated MRI, motion-corrected, dynamic, quantitative/multidimensional and cross-modal MRI tasks) and (3) reconstruction domain (image-space, k-space, hybrid and latent-space approaches).

Figure 3.

Illustration of classification scheme of diffusion-based MRI reconstruction studies. All reviewed studies are systematically categorized along three dimensions: (1) model type (standard, hybrid, latent and cold diffusion), (2) application domain (accelerated MRI, motion-corrected, dynamic, quantitative/multidimensional and cross-modal MRI tasks) and (3) reconstruction domain (image-space, k-space, hybrid and latent-space approaches).

Figure 4.

Overview of diffusion-based generative models for MRI reconstruction. The image illustrates four major categories of diffusion approaches: (1) DDPMs, which rely on stochastic forward noising and learned reverse denoising processes; (2) hybrid and physics-informed diffusion models, which incorporate adversarial, attention-based or implicit neural components as well as MRI acquisition physics through data consistency and forward operators; (3) latent diffusion models (LDMs), where diffusion is performed in a compressed latent space obtained via an encoder–decoder architecture; and (4) cold diffusion models, which replace stochastic noise with deterministic domain-specific degradations and learn their inversion.

Figure 4.

Overview of diffusion-based generative models for MRI reconstruction. The image illustrates four major categories of diffusion approaches: (1) DDPMs, which rely on stochastic forward noising and learned reverse denoising processes; (2) hybrid and physics-informed diffusion models, which incorporate adversarial, attention-based or implicit neural components as well as MRI acquisition physics through data consistency and forward operators; (3) latent diffusion models (LDMs), where diffusion is performed in a compressed latent space obtained via an encoder–decoder architecture; and (4) cold diffusion models, which replace stochastic noise with deterministic domain-specific degradations and learn their inversion.

Figure 5.

Illustration of major MRI application domains. The figure highlights five key areas where modern reconstruction and generative modeling techniques are applied: accelerated MRI (varying undersampling factors ), motion-corrected MRI (recovering images degraded by patient motion), quantitative and multidimensional MRI (e.g., ), dynamic MRI (capturing temporal anatomical changes), and cross-multimodal MRI (integrating complementary MRI contrasts or external modalities such as PET).

Figure 5.

Illustration of major MRI application domains. The figure highlights five key areas where modern reconstruction and generative modeling techniques are applied: accelerated MRI (varying undersampling factors ), motion-corrected MRI (recovering images degraded by patient motion), quantitative and multidimensional MRI (e.g., ), dynamic MRI (capturing temporal anatomical changes), and cross-multimodal MRI (integrating complementary MRI contrasts or external modalities such as PET).

Figure 6.

Overview of reconstruction domains in MRI methods. The figure illustrates four primary reconstruction domains: image-space reconstruction (operates directly on spatial MRI images), k-space reconstruction (processes data in the frequency domain), hybrid reconstruction (jointly leverages both image and k-space representations) and latent-space reconstruction (data are mapped into a compressed latent manifold for more efficient or robust reconstruction).

Figure 6.

Overview of reconstruction domains in MRI methods. The figure illustrates four primary reconstruction domains: image-space reconstruction (operates directly on spatial MRI images), k-space reconstruction (processes data in the frequency domain), hybrid reconstruction (jointly leverages both image and k-space representations) and latent-space reconstruction (data are mapped into a compressed latent manifold for more efficient or robust reconstruction).

Figure 7.

Summary of current challenges and corresponding future research directions in diffusion-based MRI reconstruction. The key methodological, computational and clinical obstacles are identified in recent literature, along with proposed strategies aimed at improving generalization, interpretability, efficiency and real-world clinical applicability of diffusion-driven reconstruction frameworks.

Figure 7.

Summary of current challenges and corresponding future research directions in diffusion-based MRI reconstruction. The key methodological, computational and clinical obstacles are identified in recent literature, along with proposed strategies aimed at improving generalization, interpretability, efficiency and real-world clinical applicability of diffusion-driven reconstruction frameworks.

Table 1.

Summary of databases and search terms used in the systematic review.

Table 1.

Summary of databases and search terms used in the systematic review.

| Database | Search Terms |

|---|

| Science Citation Index Expanded | cold diffusion, diffusion model, denoising diffusion,

score-based generative model, score-based diffusion,

cold diffusion model, magnetic resonance imaging,

MRI, k-space, undersampled MRI, accelerated MRI,

reconstruction, image reconstruction, inverse problem,

deep learning reconstruction, compressed sensing,

MRI restoration, MRI reconstruction |

| Emerging Sources Citation Index |

| MEDLINE |

| Data Citation Index |

| Conference Proceedings Citation Index |

| KCI–Korean Journal Database |

| BIOSIS Citation Index |

| Derwent Innovations Index |

| SciELO Citation Index |

| Russian Science Citation Index |

Table 2.

Summary of anatomical targets and MRI datasets used in diffusion-based MRI reconstruction studies reviewed in this work.

Table 2.

Summary of anatomical targets and MRI datasets used in diffusion-based MRI reconstruction studies reviewed in this work.

| Authors (Year) | Anatomy | Dataset Used |

|---|

| Oh et al. (2024) [13] | Brain, liver | Simulated and in vivo brain MRI; in-house abdominal MRI |

| Damudi et al. (2024) [16] | Brain | Public brain MRI datasets |

| Xie et al. (2024) [17] | Brain | ADNI PET–MRI dataset |

| Sarkar et al. (2025) [18] | Brain | Public brain MRI datasets |

| He et al. (2025) [19] | Brain | Public QSM MRI datasets |

| Zhang et al. (2025a) [20] | Heart, lung | Public cardiac cine and dynamic lung MRI datasets |

| Geng et al. (2024) [21] | General anatomy | Public MRI datasets |

| Li et al. (2025) [22] | General anatomy | Public MRI datasets |

| Zhong et al. (2023) [23] | Brain | Public diffusion-weighted MRI datasets |

| Huang et al. (2024) [11] | Brain | Public diffusion MRI datasets (FOD/dMRI) |

| Levac et al. (2024) [10] | General anatomy | Simulated and in-house clinical MRI datasets |

| Zhao et al. (2024) [24] | General anatomy | IXI, MICCAI 2013, MRNet, fastMRI |

| Guan et al. (2024) [25] | Heart | Public dynamic cardiac MRI datasets |

| Chu et al. (2025) [26] | General anatomy | Public MRI datasets |

| Shin et al. (2025) [27] | Brain, knee | fastMRI and SKM-TEA datasets |

| Wang et al. (2025) [28] | General anatomy | Public MRI datasets for super-resolution |

| Ahmed et al. (2025) [29] | General anatomy | Private MRI dataset and fastMRI |

| Qiao et al. (2025) [30] | General anatomy | Public MRI datasets |

| Uh et al. (2025) [31] | Brain | In-house pediatric brain MRI dataset |

| Zhang et al. (2024) [32] | Brain | Public multishell diffusion MRI datasets |

| Zhao et al. (2025) [33] | Brain | Public brain MRI datasets |

| Guan et al. (2025) [34] | Multi-contrast anatomy | Public multi-contrast MRI datasets |

| Aali et al. (2025) [35] | Brain, knee | Multi-coil brain and knee MRI datasets |

| Qiu et al. (2024) [36] | Heart | Public cardiac MRI datasets |

| Hou et al. (2025) [37] | General anatomy | Public MRI datasets |

| Shah et al. (2024) [14] | Heart | Public cardiac MRI datasets |

| Zhang et al. (2025b) [38] | Brain | Public QSM MRI datasets |

| Chen et al. (2025) [39] | General anatomy | Public multi-coil MRI datasets |

| Hu et al. (2016) [40] | Brain | ADNI brain MRI dataset |

| Daducci et al. (2016) [41] | Brain | Synthetic and in vivo diffusion MRI datasets |

| Li et al. (2025) [42] | General anatomy | Public 3D MRI datasets |

| Liu et al. (2024) [43] | Brain | Natural Scenes Dataset (NSD, fMRI) |

| Wang et al. (2024) [44] | Brain | Public fMRI datasets |

| Li et al. (2024) [45] | Brain | Natural Scenes Dataset (NSD, fMRI) |

| Kalantari et al. (2025) [46] | Brain | Public fMRI datasets |

| Shen et al. (2024) [47] | General anatomy | Large open-source MRI datasets (cold diffusion, k-space) |

| Cui et al. (2024) [12] | General anatomy | Public MRI datasets with simulated undersampling |

| Dong et al. (2026) [48] | General anatomy | Public MRI datasets with progressive cold k-space undersampling |

| Lu et al. (2025) [49] | General anatomy | Public MRI datasets with simulated undersampling |

| Zhao et al. (2024) [50] | General anatomy | Public multidimensional MRI datasets |

Table 3.

Classification of standard diffusion-based MRI reconstruction studies.

Table 3.

Classification of standard diffusion-based MRI reconstruction studies.

| Author (Year) | Model Type | Core Contribution |

|---|

| Oh et al. (2024) [13] | Score-based DDPM | Annealed diffusion (CCDF) with forward–reverse sampling for motion artifact correction; unsupervised, physics-aware training. |

| Damudi et al. (2024) [16] | DDPM (single-step) | Single-step simplex-noise diffusion for unsupervised lesion detection; lightweight one-step design. |

| Xie et al. (2024) [17] | Score-based joint diffusion | MC-Diffusion for PET–MRI joint reconstruction using shared score-based priors. |

| Sarkar et al. (2025) [18] | Diffusion posterior sampling | AutoDPS: posterior diffusion sampling for unsupervised MRI restoration; blind corruption estimation. |

| He et al. (2025) [19] | DDPM (QSM) | ACE-QSM: score-based diffusion for quantitative susceptibility mapping with wavelet stabilization. |

| Zhang et al. (2025) [20] | Domain-conditioned DDPM | dDiMo: spatiotemporal priors with CG optimization in reverse diffusion for dynamic MRI. |

| Geng et al. (2024) [21] | Multi-diffusion model | DP-MDM: multiple score networks for detail-preserving MRI reconstruction at multiple scales. |

| Li et al. (2025) [22] | Posterior-sampling DDPM | Efficient diffusion posterior sampling (DPS) via gradient-descent likelihood updates. |

| Zhong et al. (2023) [23] | Spatiotemporal DDPM | Dynamic diffusion (dDiMo) jointly modeling spatial–temporal correlations. |

| Huang et al. (2024) [11] | DDPM (dMRI FOD) | Volume-order-aware encoding and cross-attention for fiber orientation distribution restoration. |

Table 4.

Classification of hybrid- and physics-informed diffusion-based MRI reconstruction studies.

Table 4.

Classification of hybrid- and physics-informed diffusion-based MRI reconstruction studies.

| Author (Year) | Model Type | Core Contribution |

|---|

| Levac et al. (2024) [10] | Hybrid (Bayesian DPS) | Motion-aware hybrid diffusion with joint posterior sampling of image and motion parameters. |

| Zhao et al. (2024) [24] | DiffGAN (Hybrid) | Adversarial–diffusion with local vision transformer (LVT) for perceptual realism. |

| Guan et al. (2024) [25] | GLDM (Hybrid) | Global-to-local diffusion with low-rank and DC regularization for zero-shot MRI. |

| Chu et al. (2025) [26] | DiffINR | Diffusion integrated with implicit neural representations (INR) for stable posterior sampling. |

| Shin et al. (2025) [27] | ELF-Diff | Standard score-based diffusion model enhanced with ensemble and adaptive frequency mixing strategies |

| Wang et al. (2025) [28] | dDiMo | A domain-conditioned and temporal-guided diffusion model that integrates spatial, temporal, and frequency-domain information through 3D CNN-based noise estimation. |

| Ahmed et al. (2025) [29] | PINN-DADif | Physics-informed adaptive diffusion integrating PINNs with stochastic denoising priors. |

| Qiao et al. (2025) [30] | SGP-MDN | Model-driven network guided by pretrained score priors with physics constraints. |

| Uh et al. (2025) [31] | Adaptive Diffusion | Patient-specific adaptive diffusion incorporating individualized priors during inference. |

| Zhang et al. (2024) [32] | Transformer + GAN Hybrid | Local transformer attention within adversarial diffusion for MRI SR. |

| Zhao et al. (2025) [33] | Mamba-Diffusion | Hybrid diffusion–state-space architecture (VSSM + SIF-Mamba) for perception-aware modeling. |

| Guan et al. (2025) [34] | DMSE (Hybrid) | Distribution-matching subset-k-space embedding combining stochastic priors and deterministic physics. |

| Aali et al. (2025) [35] | DPM + MoDL | GSURE-based denoising to enhance hybrid diffusion and MoDL performance on noisy data. |

| Qiu et al. (2024) [36] | DBSR (Hybrid) | Quadratic conditional diffusion with blur-kernel estimation for cardiac MRI SR. |

| Hou et al. (2025) [37] | FRSGM (ADMM Hybrid) | ADMM-integrated diffusion with ensemble denoisers ensuring convergence and stability. |

| Shah et al. (2024) [14] | Quadratic Conditional DDPM | Conditional diffusion guided by blur kernels for controllable cardiac MRI SR. |

| Zhang et al. (2025) [38] | Diffusion-QSM | Physics-informed diffusion for susceptibility mapping with resampling refinement. |

| Chen et al. (2025) [39] | JSMoCo | Joint estimation of motion and coil maps via physics-informed diffusion with Gibbs sampling. |

| Hu et al. (2016) [40] | Physics-Integrated DDPM | Embedded MRI encoding operator in score-based diffusion for data-consistent reconstruction. |

| Daducci et al. (2016) [41] | Bayesian Hybrid Diffusion | Probabilistic–physical model fusion for uncertainty-aware reconstruction. |

| Li et al. (2025) [42] | SNAFusion-MIX | Multi-step teacher–student hybrid diffusion for efficient 3D reconstruction. |

Table 5.

Classification of latent diffusion-based MRI reconstruction studies.

Table 5.

Classification of latent diffusion-based MRI reconstruction studies.

| Author (Year) | Model Type | Core Contribution |

|---|

| Li et al. (2024) [43] | Mind-Bridge LDM | CLIP-guided LDM with structural and semantic alignment for brain decoding. |

| Wang et al. (2024) [44] | MAE-LDM (fMRI) | Multimodal masked autoencoder with conditional LDM for neural decoding. |

| Lu et al. (2025) [49] | LRDM | Latent-k-space refinement diffusion with hierarchical two-stage reconstruction. |

| Zhao et al. (2024) [50] | Disentangled LDM | Dual-encoder LDM separating geometry and contrast for multidimensional MRI. |

| Kalantari et al. (2025) [46] | BLIP-LDM | BLIP-conditioned latent diffusion for visual/semantic decoding from fMRI. |

| Li et al. (2024) [45] | NeuralDiffuser | Latent-guided diffusion integrating top-down semantics and low-level features. |

Table 6.

Classification of cold diffusion-based MRI reconstruction studies.

Table 6.

Classification of cold diffusion-based MRI reconstruction studies.

| Author (Year) | Model Type | Core Contribution |

|---|

| Shen et al. (2024) [47] | CDiff | Deterministic k-space degradation and data-consistent reverse network for MRI. |

| Cui et al. (2024) [12] | Physics-informed CDiff | Reverse heat diffusion modeling of HF–LF interpolation in k-space. |

| Dong et al. (2025) [48] | AMK-CDiffNet | Adaptive multi-scale cold diffusion with progressive undersampling and fusion. |

Table 7.

Classification of reviewed studies by application domain in accelerated MRI.

Table 7.

Classification of reviewed studies by application domain in accelerated MRI.

| Author (Year) | Application Domain | Core Contribution |

|---|

| Zhao et al. (2024) [24] | Accelerated MRI/DiffGAN | Adversarial–diffusion model that restores high-quality MRI from undersampled data. It reduces aliasing artifacts and preserves diagnostic fidelity. |

| Shen et al. (2024) [47] | Accelerated MRI/Cold Diffusion | Deterministic k-space undersampling replacing Gaussian noise. It achieves artifact-free and stable reconstructions. |

| Ahmed et al. (2025) [29] | Accelerated MRI/PINN-DADif | Physics-informed diffusion combining k-space data fidelity with image-space regularization to enhance interpretability and stability. |

| Cui et al. (2024) [12] | Accelerated MRI/Physics-informed cold diffusion | Reverse heat diffusion in k-space interpolating high-frequency details from low-frequency data. Enables deterministic and physically consistent reconstruction. |

| Guan et al. (2024) [25] | Accelerated MRI/GLDM | Global-to-Local Diffusion Model enabling zero-shot generalization across acquisition trajectories. |

| Chu et al. (2025) [26] | Accelerated MRI/DiffINR | Integration of diffusion priors with implicit neural representations for robust reconstruction under high acceleration factors. |

| Shin et al. (2025) [27] | Accelerated MRI/ELF-Diff | Adaptive low-frequency mixing improves reconstruction stability and reduces hallucination artifacts under different sampling masks. |

| Hou et al. (2025) [37] | Accelerated MRI/FRSGM | Combines diffusion and ADMM optimization for faster convergence and high fidelity at high acceleration factors. |

| Aali et al. (2025) [35] | Accelerated MRI/DPM + MoDL | Self-supervised denoising improves diffusion-based reconstruction robustness in noisy multi-coil MRI acquisitions. |

| Li et al. (2025) [42] | 3D Accelerated MRI/SNAFusion-MM | Multi-view hybrid diffusion framework fusing 2D priors into consistent 3D volumes for efficient volumetric reconstruction. |

| Qiu et al. (2024) [36] | Accelerated MRI/DBSR | Quadratic conditional diffusion with blur-kernel estimation achieving high-resolution cardiac MRI reconstruction. |

| Zhao et al. (2025) [33] | Accelerated MRI/Mamba Diffusion | Perception-aware diffusion model with global context modeling for high-resolution brain MRI restoration. |

| Dong et al. (2025) [48] | Accelerated MRI/AMK-CDiffNet | Adaptive multi-scale cold diffusion achieving strong edge preservation and improved numerical stability. |

| Lu et al. (2025) [49] | Accelerated MRI/LRDM | Latent k-space refinement diffusion with hierarchical two-stage reconstruction. It achieves high fidelity with low computational cost. |

| Geng et al. (2024) [21] | Accelerated MRI/DP-MDM | Multi-scale ensemble of diffusion models preserving fine structural details. |

| Li et al. (2025) [22] | Accelerated MRI/DPS | Efficient diffusion posterior sampling that incorporates measurement-guided gradients to enhance reconstruction accuracy. |

| Hu et al. (2016) [40] | Accelerated MRI/Physics-Integrated DDPM | Early embedding of MRI encoding operators into diffusion sampling for data-consistent reconstruction. |

| Daducci et al. (2016) [41] | Accelerated MRI/Bayesian Hybrid Diffusion | Bayesian fusion of probabilistic diffusion and physical modeling for uncertainty-aware MRI reconstruction. |

| Damudi et al. (2024) [16] | Accelerated MRI/Simplex diffusion | Proposes a single-step diffusion method for anomaly localization and artifact suppression in undersampled MRI, emphasizing computational efficiency and stability for rapid reconstruction. |

| Qiao et al. (2024) [30] | Accelerated MRI/SGP-MDN | Integrates pretrained score priors with MRI physics constraints to enhance artifact removal and consistency in highly undersampled k-space reconstruction. |

Table 8.

Classification of reviewed studies by application domain in motion-corrected MRI.

Table 8.

Classification of reviewed studies by application domain in motion-corrected MRI.

| Author (Year) | Application Domain | Core Contribution |

|---|

| Oh et al. (2024) [13] | Artifact suppression | Annealed forward–reverse diffusion for reduced motion blur. |

| Levac et al. (2024) [10] | Motion-corrected MRI | Joint motion trajectory estimation and reconstruction via hybrid diffusion. |

| Sarkar et al. (2025) [18] | Motion artifact correction | AutoDPS: unsupervised posterior sampling with motion parameter estimation. |

| Chen et al. (2025) [39] | Motion-corrected accelerated MRI | JSMoCo: joint estimation of motion and coil sensitivity maps via diffusion priors. |

| Uh et al. (2025) [31] | Motion-corrected accelerated MRI | Adaptive diffusion model |

Table 9.

Classification of reviewed studies by application domain in dynamic MRI.

Table 9.

Classification of reviewed studies by application domain in dynamic MRI.

| Author (Year) | Application Domain | Core Contribution |

|---|

| Guan et al. (2024) [34] | Dynamic cardiac MRI | Global-to-local diffusion with low-rank regularization. |

| Zhang et al. (2025) [20] | Dynamic MRI | Domain-conditioned diffusion (dDiMo) for spatiotemporal coherence. |

| Wang et al. (2025) [28] | Dynamic MRI | Temporal-guided diffusion for motion-resolved reconstruction. |

| Zhong et al. (2023) [23] | Dynamic MRI | Spatiotemporal DDPM with temporal smoothness constraints. |

| Shah et al. (2024) [14] | Dynamic MRI | Temporally conditioned diffusion guided by blur kernels, capturing inter-frame coherence and motion-related detail. |

| Zhang et al. (2025) [20] | Dynamic MRI | Jointly reconstructs accelerated Cartesian and non-Cartesian dynamic data using x-t and k-t priors |

Table 10.

Classification of reviewed studies by application domain in quantitative and multidimensional MRI.

Table 10.

Classification of reviewed studies by application domain in quantitative and multidimensional MRI.

| Author (Year) | Application Domain | Core Contribution |

|---|

| He et al. (2025) [19] | Quantitative MRI | Short-TE diffusion model for QSM with wavelet stabilization. |

| Zhang et al. (2025) [32] | Quantitative MRI | Diffusion-QSM with physics-informed refinement. |

| Zhao et al. (2024) [50] | Quantitative MRI | LDM with disentangled feature spaces. |

| Huang et al. (2024) [11] | Diffusion MRI | FOD-diffusion for fiber orientation restoration with cross-attention. |

Table 11.

Classification of reviewed studies by application domain in cross-multimodal MRI.

Table 11.

Classification of reviewed studies by application domain in cross-multimodal MRI.

| Author (Year) | Application Domain | Core Contribution |

|---|

| Xie et al. (2024) [17] | PET–MRI | Joint score-based diffusion for multi-modal PET–MRI enhancement. |

| Liu et al. (2024) [43] | fMRI decoding | Mind-Bridge: CLIP-guided latent diffusion for fMRI→image translation. |

| Wang et al. (2024) [44] | fMRI decoding | Multimodal MAE–LDM for brain visual scene reconstruction. |

| Li et al. (2025) [45] | fMRI decoding | NeuralDiffuser integrating top-down and bottom-up latent features. |

| Kalantari et al. (2025) [46] | fMRI decoding | BLIP-conditioned latent diffusion for semantic–visual decoding. |

Table 12.

Classification of reviewed studies according to their reconstruction domain, focusing on image-space-based approaches.

Table 12.

Classification of reviewed studies according to their reconstruction domain, focusing on image-space-based approaches.

| Author (Year) | Core Reconstruction Strategy |

|---|

| Oh et al. (2024) [13] | Diffusion denoising in image space with embedded k-space consistency weighting to suppress motion artifacts. |

| Damudi et al. (2024) [16] | One-step simplex diffusion applied directly to image intensities for lesion detection. |

| Zhao et al. (2024) [24] | DiffGAN combines diffusion-based denoising and GAN refinement on image-space representations. |

| Xie et al. (2024) [17] | PET–MRI joint reconstruction using shared diffusion priors across modalities. |

| He et al. (2025) [19] | DDPM restores QSM susceptibility maps using wavelet-stabilized time–frequency priors. |

| Shin et al. (2025) [27] | ELF-Diff denoises undersampled MRI via image-domain diffusion with iterative data consistency optimization. |

| Qiao et al. (2025) [30] | Score-based priors refine undersampled reconstructions via image-domain denoising. |

| Zhang et al. (2024) [32] | Adversarial diffusion with local transformer attention enhances perceptual realism. |

| Zhao et al. (2025) [24] | Mamba-enhanced diffusion model reconstructs images using blur-aware latent conditioning. |

| Aali et al. (2025) [35] | Image-domain denoising and diffusion reconstruction trained on self-supervised denoised data. |

| Qiu et al. (2024) [36] | Conditional blur-kernel diffusion reconstructs cardiac MRI with motion-compensated priors. |

| Shah et al. (2024) [14] | Conditional quadratic diffusion (DBSR) for cardiac MRI super-resolution. |

| Zhang et al. (2025) [38] | Diffusion-QSM reconstructs susceptibility maps via image-domain diffusion and physical priors. |

| Li et al. (2025) [42] | Multi-view 2D priors fused into consistent 3D reconstructions. |

Table 13.

Classification of reviewed studies according to their reconstruction domain, focusing on k-space-based approaches.

Table 13.

Classification of reviewed studies according to their reconstruction domain, focusing on k-space-based approaches.

| Author (Year) | Core Reconstruction Strategy |

|---|

| Cui et al. (2024) [12] | Cold diffusion via deterministic heat-based interpolation restoring missing high-frequency k-space data. |

| Guan et al. (2025) [25] | DMSE operates on subset-k-space embeddings with low-rank regularization for multi-contrast MRI. |

| Geng et al. (2024) [21] | Multi-diffusion ensemble learning in frequency domain for detail-preserving MRI. |

| Dong et al. (2025) [48] | AMK-CDiffNet deterministic cold diffusion directly on k-space with multi-scale fusion. |

Table 14.

Classification of reviewed studies according to their reconstruction domain, focusing on hybrid-space-based approaches.

Table 14.

Classification of reviewed studies according to their reconstruction domain, focusing on hybrid-space-based approaches.

| Author (Year) | Core Reconstruction Strategy |

|---|

| Levac et al. (2024) [10] | Alternates image-domain inference with k-space motion modeling for joint motion and reconstruction. |

| Sarkar et al. (2025) [18] | AutoDPS posterior sampling links diffusion priors to undersampled measurements for artifact-free MRI. |

| Chu et al. (2024) [26] | DiffINR couples image diffusion priors with INR-based physical modeling in k-space. |

| Zhang et al. (2025) [20] | Dynamic diffusion reconstruction integrating k–t and x–t spatiotemporal priors. |

| Wang et al. (2025) [28] | Spatiotemporal dDiMo diffusion with conjugate-gradient refinement for dynamic MRI. |

| Shen et al. (2024) [47] | Cold diffusion using deterministic k-space degradation with image-domain supervision. |

| Ahmed et al. (2025) [29] | PINN-DADif combines image-space denoising and physics-constrained k-space regularization. |

| Uh et al. (2025) [31] | Patient-specific adaptive diffusion integrating k-space conditioning and image-space priors. |

| Hou et al. (2025) [37] | FRSGM alternates diffusion-based image denoising with ADMM k-space updates. |

| Lu et al. (2025) [49] | Latent-k-space diffusion with image refinement to recover high-frequency detail. |

| Li et al. (2025) [22] | Diffusion posterior sampling with measurement-guided gradient descent. |

| Chen et al. (2025) [39] | JSMoCo jointly models motion and coil sensitivity in diffusion-based reconstruction. |

| Hu et al. (2016) [40] | Alternating iterative denoising enforcing k-space fidelity and image-domain consistency. |

| Daducci et al. (2016) [41] | Bayesian reconstruction merging q-space diffusion and spatial-domain regularization. |

| Zhong et al. (2023) [23] | dDiMo learns spatiotemporal diffusion distribution across spatial–temporal axes. |

| Guan et al. (2024) [25] | HyDiffNet alternates between k-space consistency and image-space denoising. |

| Huang et al. (2024) [11] | CD2M integrates k-space and image-space through a shared latent diffusion process with domain-consistency constraints. |

Table 15.

Classification of reviewed studies according to their reconstruction domain, focusing on latent-space-based approaches.

Table 15.

Classification of reviewed studies according to their reconstruction domain, focusing on latent-space-based approaches.

| Author (Year) | Core Reconstruction Strategy/Domain Interaction |

|---|

| Liu et al. (2024) [43] | Mind-Bridge reconstructs visual images from fMRI via latent multimodal diffusion. |

| Wang et al. (2024) [44] | MAE–LDM performs multimodal latent reconstruction from fMRI embeddings. |

| Li et al. (2024) [45] | Stable Diffusion latent decoding guided by fMRI features and CLIP embeddings. |

| Zhao et al. (2024) [50] | Disentangled latent T1/T2 mapping reconstruction with physical consistency. |

| Kalantari et al. (2025) [46] | BLIP-conditioned latent diffusion reconstructs semantic visual content from fMRI. |

Table 16.

Advantages and disadvantages of different diffusion-based model types for MRI reconstruction.

Table 16.

Advantages and disadvantages of different diffusion-based model types for MRI reconstruction.

| Model Type | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|

| Standard Diffusion Models | Strong generative capacity for artifact removal, denoising, and image restoration across MRI modalities. Capable of modeling complex, non-Gaussian noise distributions through iterative sampling. Adapt well to heterogeneous datasets and 3D imaging tasks. | High computational cost due to many sampling steps. Sensitive to sampling schedules and hyperparameters. Limited clinical practicality without integration of acceleration or parallel imaging methods. |

| Hybrid and Physics-Informed Diffusion Models | Combine stochastic generative learning with deterministic MRI physics for improved realism and data fidelity. Reduce hallucination artifacts and improve generalization across sampling patterns and acceleration factors. Enhanced interpretability through explicit data-consistency terms or physics-based constraints. | Added optimization and computational complexity from physical operator integration. Balancing learned and physical priors remains challenging. Risk of longer training or inference times compared to purely data-driven models. |

| Latent Diffusion Models | Operate in compact latent spaces, reducing training and sampling costs. Maintain structural and perceptual fidelity while improving computational efficiency. Effective in multimodal and fMRI-to-image reconstruction tasks. | Dependence on pretrained backbones that may not generalize to medical data. Limited by small and domain-specific medical datasets. Require fine-tuning or domain adaptation to achieve optimal performance. |

| Cold Diffusion Models | Replace stochastic noise with deterministic degradation, improving stability and interpretability. Offer faster convergence and higher fidelity reconstruction. Physically aligned with real MRI acquisition processes. | Applicability to complex scenarios is not yet fully validated. Reduced generative flexibility compared to stochastic methods. May need hybridization with latent or physics-based approaches for broader usability. |