Abstract

Three-dimensional human pose estimation (3D HPE) aims to recover the three-dimensional coordinates of human joints from 2D images or videos to achieve precise quantification of human movement. In 3D HPE tasks based on multi-class complex human action datasets, the performance of existing Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) and Transformer fusion models is constrained by the fixed physical connections of the skeleton, which impedes the modeling of cross-joint long-range semantic dependencies and hinders further performance gains. To address this issue, this study proposes a semantic prior-based non-Euclidean topology enhancement method for multi-class complex human actions, built upon a GCN–Transformer fusion model. The proposed method retains the original physical connections while introducing semantic prior edges; by constructing a hybrid topology structure, it explicitly models long-range semantic dependencies between non-adjacent joints, thereby facilitating the extraction of cross-joint semantic information. Experimental results on the Human3.6M and HumanEva-I datasets surpass those of SOTA baseline models. On the Human3.6M dataset, MPJPE and P-MPJPE are reduced by 1.25% and 0.63%, respectively. For the Walk and Jog actions on the HumanEva-I dataset, MPJPE is reduced by approximately 6.5%. These results demonstrate that the proposed method offers significant advantages for 3D HPE tasks based on multi-class complex human action data.

1. Introduction

Three-dimensional human pose estimation (3D HPE) is widely used in action recognition, virtual reality, human–computer interaction, and other scenarios [1,2,3]. Various types of deep learning models have made significant progress in pose estimation tasks. Among them, the fusion model of GCN and Transformer is particularly noteworthy [4].

Existing fusion models mostly directly use fixed anatomical physical skeletons as input, making it difficult to perceive cross-joint long-range semantic information. The information transmission of “Euclidean topology” skeleton graphs based on anatomical structures follows local physical connection constraints, while the “non-Euclidean topology” long-range cross-joint connections determined by action semantics rely on long-range semantic functional correlations between non-geometrically adjacent joints. Although the adjacency matrix established based on anatomical skeletons in existing research reasonably represents human structure, it is difficult to represent the long-range semantic functional correlations between non-adjacent joints in human movement. Existing research has broken through the limitations of anatomical skeletons for representing complex human actions through implicit mechanisms, but still faces issues of incomplete semantic information and insufficient structural stability.

Addressing the aforementioned challenges, this study proposes a semantic priors-based non-Euclidean topological enhancement method. This method preserves the physical skeleton structure while introducing semantic prior edges capable of enhancing the representation of multi-class complex human actions. It achieves a unified representation of physical constraints and semantic dependencies through hybrid topological modeling. Unlike existing methods, this study not only retains the anatomical rationality but also explicitly models the cross-joint long-range semantic functional coupling for multi-class complex human actions. By analyzing the motion features of multi-class complex human actions to design semantic prior edges, the model gains more comprehensive cross-joint long-range semantic information. The contributions of this study are summarized as follows:

- This study proposes a non-Euclidean topological enhancement method with semantic priors for multi-class complex human actions. This method explicitly constructs long-range semantic information pathways by introducing semantic prior edges into the input skeleton graph of the fusion model.

- The proposed method is interpretable and portable, and can improve model performance without increasing parameter count or computational overhead.

- Experimental results on the fusion model demonstrate that this method significantly reduces key evaluation metrics such as MPJPE and P-MPJPE, surpassing existing SOTA [4].

2. Related Works

2.1. Monocular 3D HPE

Current research on monocular 3D HPE can be broadly divided into two approaches: two-stage 2D to 3D lifting approaches and end-to-end regression methods. The former uses a 2D detector to obtain high-quality keypoints, followed by regression or temporal models to recover the 3D pose [5]. The latter employs an end-to-end method to directly regress the 3D pose from images or video frames, without relying on explicit 2D keypoint detection [6].

In recent years, GCN, Transformer, and GCN–Transformer fusion models have shown continuous improvement in monocular 3D HPE [7,8]. Based on human anatomical skeleton information, GCNs can typically effectively utilize local connection relationships to implicitly model semantic information. Transformers excel at capturing global dependencies, thereby more comprehensively characterizing human motion patterns across spatio-temporal dimensions [9]. The PoseFormer series of models achieve good performance on the Human3.6M dataset by modeling joint trajectories through stacking spatial and temporal Transformer blocks [7,10]. The Mixed Spatio-Temporal Encoder (MixSTE) and Spatio-Temporal Criss-Cross Transformer (STCFormer) further optimize the interaction of spatio-temporal features, enhancing stability in long sequences [11,12]. GCN–Transformer fusion models combine the advantages of GCN and Transformer, enabling not only the acquisition of rich spatial information but also the effective capture of temporal information. The Graph Convolution Transformer (GraFormer) encodes graph structures into the attention mechanism, equipping the Transformer with graph-aware capabilities [8]. The Kinematics and Trajectory Prior Knowledge-Enhanced Transformer (KTPFormer) explicitly injects kinematic and trajectory priors before attention computation [4].

2.2. Evolution of Skeleton Feature Extraction

Three-dimensional HPE modeling based on traditional anatomical skeletons typically constructs a fixed adjacency matrix in Euclidean space, capable of only representing local physical connection relationships (such as “shoulder–elbow–wrist” and “hip–knee–ankle” connections). While such skeleton structures ensure anatomical rationality, they limit the model’s ability to capture cross-joint long-range semantic functional correlations. A single Euclidean skeleton is often insufficient to achieve the coupling of human joints in multi-class complex human actions.

To overcome the limitations of the Euclidean skeleton in representing multi-class complex human actions, scholars have conducted relevant research based on GCN models. In 2019, Zhao et al. proposed Semantic Graph Convolutional Networks (SemGCN), systematically introducing the concept of semantic edges into 3D pose regression tasks [13]. This method, based on traditional physical skeleton graphs, can implicitly learn the potential partial non-local semantic dependencies between human joints, significantly enhancing the model’s ability to analyze multi-class complex human action data [13]. In 2022, Li et al. [14] further proposed Semantic-Structural Graph Convolutional Networks (SSGCN), combining semantic edge and structural edge information to construct a graph structure that aligns more closely with human movement logic. Through multi-scale graph modeling, they achieved breakthroughs in the accuracy of whole-body human pose estimation [14]. Additionally, both SemGCN and Channel-wise Topology Refinement Graph Convolution Networks (CTR-GCN) introduce learnable semantic modeling mechanisms within the graph convolution framework, by adaptively learning and adjusting semantic edge weights, enhancing the modeling capability of cross-joint long-range semantic dependencies in non-Euclidean topology [13,15].

In addition to semantic modeling-driven topological transformation, multi-scale fusion has become another key direction in skeleton feature extraction. Researchers acquire more comprehensive and effective features by fusing information of different scales (such as local joint details and global pose structure, short-term motion continuity, and long-term action periodicity). The effectiveness of this strategy has been supported by cross-domain verification [16] and specific practical applications in the field of skeleton extraction [4].

Overall, the semantic modeling of GCNs has driven the transformation of 3D HPE from fixed topologies based on Euclidean skeletons to non-Euclidean topologies.

2.3. GCN–Transformer Fusion

Since GCNs are adept at utilizing the local topological structure of the skeleton to establish structural priors, they can follow the physical connection constraints of the human skeleton without learning from scratch. However, the receptive field of GCN-based models is limited, making it difficult to model cross-joint long-range semantic functional correlations. While Transformer-based models can capture global contextual dependencies through self-attention mechanisms, they are insensitive to the inherent topological structure of the skeleton. Therefore, Transformer-based models may fail to learn anatomically logical connection relationships. Consequently, leveraging the complementarity in motion modeling, fusion models of GCN and Transformer have gradually become an important direction in 3D HPE [17]. The Graph-Oriented Transformer (GraFormer) explicitly encodes graph structure priors into attention, enabling self-attention to possess graph-aware capabilities [17]. The KTPFormer introduces kinematic and trajectory priors before multi-head self-attention (MHSA) to unify topological and temporal modeling [4]. The Dynamic Graph Transformer (DGFormer) leverages dynamic graphs and attention jointly to enhance robustness against occlusion and long-range interactions [18]. The Multi-hop Graph Transformer Network captures cross-joint long-range semantic dependencies through multi-hop neighborhoods [19].

2.4. Summary

Existing research enhances the performance of models in monocular 3D HPE tasks by strengthening the extraction capabilities of different models for spatio-temporal features. Some scholars have achieved unified modeling of topology and temporality by injecting prior knowledge into the models, thereby obtaining better performance. Based on skeleton data, existing GCN models have begun to focus on acquiring non-local features by reinforcing the models to capture more non-local semantic dependencies. Fusion models of GCN and Transformer, by constructing local topological modeling and global dependency relationships, can effectively extract cross-joint long-range semantic features from skeleton data, thus performing excellently in 3D HPE tasks.

However, the aforementioned research generally relies on fixed anatomical skeleton adjacency matrices or implicit learning modeling, which suffer from insufficient semantic information extraction capabilities. These issues also make it difficult for fusion models of GCN and Transformer to obtain sufficient explicit cross-joint long-range semantic information in multi-class complex human action datasets. Therefore, there is potential for further improvement in the performance of GCN and Transformer fusion models on multi-class complex human action datasets.

3. Methods

To address the aforementioned limitations, this study proposes a semantic priors-based non-Euclidean topological enhancement method that explicitly constructs cross-joint long-range semantic pathways to overcome the shortcomings of existing models. Based on the state-of-the-art (SOTA) model KTPFormer in the field of 3D human pose estimation, this paper achieves performance surpassing the current SOTA [4].

While existing approaches like SemGCN and CTR-GCN adopt an implicit learning paradigm—dynamically constructing semantic edges through learnable parameters within the network layers—they inevitably introduce additional model complexity and often yield connections lacking clear functional interpretation [13,15]. In contrast, this work is grounded in an explicit priors-based design philosophy. We posit that for structured tasks such as 3D HPE, directly optimizing the input topological representation using domain knowledge offers a more efficient and interpretable inductive bias. Our method manually designs and statically injects semantic prior edges, guided by kinematic analysis, adhering to two core principles: (1) Maximum Interpretability: each added edge corresponds to a describable motion function; (2) Zero-Parameter Overhead: the enhancement occurs at the input level, introducing no extra learnable parameters, thus preserving the baseline model’s complexity.

The method proposed in this paper provides a structural foundation for GCNs to model long-range dependencies by designing semantic prior edges. Meanwhile, this more representative graph structure also provides better input for the attention mechanism in Transformers. After regional segmentation of human skeleton data, the overall performance of the model on multi-class complex human actions is improved by enhancing common features within the core regions and personalized features in non-core regions. After introducing the common features of multi-class human complex human actions and the personalized features of specific classes into the graph structure through prior knowledge, this method achieves non-Euclidean topological enhancement driven by the semantic priors of multi-class human complex human actions on Euclidean skeletons. This method strengthens the modeling foundation of multi-class complex human actions from the source, providing a semantically enhanced input for the fusion model.

3.1. Backbone: KTPFormer

3.1.1. Network Architecture

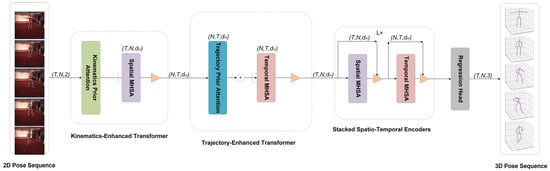

Peng et al. proposed the KTPFormer (Kinematics and Trajectory Prior Knowledge-Enhanced Transformer), which enhances the model’s capacity for modeling human joints by incorporating prior knowledge ahead of the Transformer’s Multi-Head Self-Attention (MHSA) mechanism [4]. The KTPFormer employs two lightweight prior-attention modules: the Kinematics Prior Attention (KPA) and the Trajectory Prior Attention (TPA). As illustrated in Figure 1, the input 2D keypoint sequence is first processed by the Kinematics-Enhanced Transformer. Here, the KPA module injects prior knowledge of the human anatomical structure, and the resulting spatial tokens are then passed to the spatial MHSA to learn spatial dependencies among joints. Subsequently, the feature sequence is reshaped and fed into the Trajectory-Enhanced Transformer, where the TPA module injects prior knowledge of joint motion trajectories. The resulting temporal tokens are then processed by the temporal MHSA to learn temporal dependencies across frames. Finally, the output is fed through Stacked Spatio-Temporal Encoders and a regression head to obtain the final 3D human pose. Figure 1 illustrates the overall framework of the KTPFormer.

Figure 1.

Overview of Kinematics and Trajectory Prior Knowledge-Enhanced Transformer (KTPFormer) [4].

3.1.2. Kinematics Prior Attention (KPA)

Kinematics Prior Attention (KPA) utilizes anatomical structural information of the human body to guide the learning of spatial attention. KPA first constructs spatial local topology, which is an adjacency matrix determined by the physical connection relationships of the skeleton. Additionally, KPA can introduce a learnable fully connected topology (simulated spatial global topology) structure to capture potential correlations between non-directly connected joints. The combination of these two forms a kinematic topology matrix that enables the model to automatically distinguish the constraint relationships between different joints during self-attention computation.

3.1.3. Trajectory Prior Attention (TPA)

This model utilizes the motion trajectory relationship in the time dimension of Trajectory Prior Attention (TPA) modeling. TPA can establish temporal local topology, i.e., by connecting nodes of the same joint in adjacent frames to characterize continuity. Additionally, TPA can also utilize learnable global topology (simulated temporal global topology) to further model periodicity or similarity between distant frames. Combining the two can yield joint motion trajectory topology, enabling the model to capture both continuity and periodicity of motion in the time dimension.

3.2. Semantic Prior-Driven Hybrid Topology Design

Although anatomically based Euclidean skeletal topology (e.g., the “shoulder–elbow–wrist” chain structure) ensures anatomical plausibility, its representational capacity is often constrained by the physical connections of the skeleton. This limitation prevents KTPFormer from learning cross-joint long-range semantic functional relationships. Therefore, this study constructs a hybrid topology for GCN–Transformer fusion models. The hybrid topology consists of the original physical connections together with the designed semantic prior edges. The design philosophy of this hybrid topology is to systematically add semantic prior edges—based on distinguishing between core and non-core regions—while preserving the physical connections. In this way, the proposed topology achieves a unified representation of both physical constraints and semantic relationships. Consequently, when estimating poses for complex multi-class human actions, the proposed topology enables effective feature extraction from cross-joint motion in core regions as well as cross-joint motion in non-core regions.

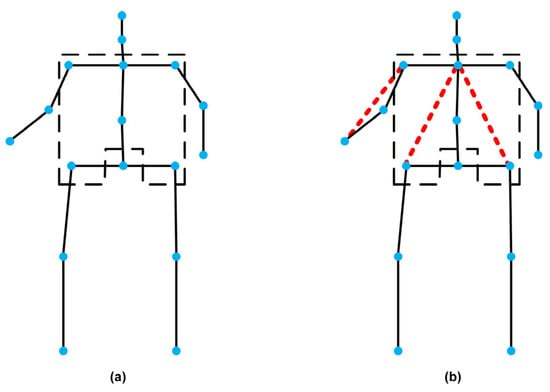

The semantic prior edges proposed in this study are divided into two classes: edges used to enhance common features of core regions and edges used to enhance personalized features of non-core regions. Through visualization of the dataset, this study identified the core regions where common features are present and the non-core regions where personalized features are present for representing the complex human action skeletons of multi-class human actions. This study designed corresponding semantic priors on the Human3.6M dataset (Figure 2) and constructed a hybrid topology with enhanced representational capacity. To validate the generality of this design approach, this study also applied the design to the HumanEva-I dataset, constructing a hybrid topology suitable for this dataset.

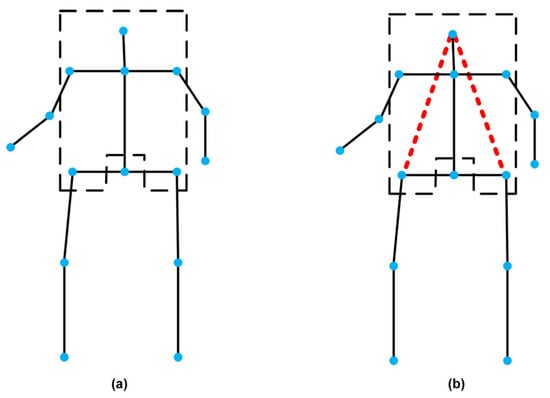

Figure 2.

Illustration of the hybrid topology on Human3.6M. (a) represents original topological skeleton; (b) represents hybrid topological structure. The black solid line and the red dashed line respectively represent physical connections and semantic prior connections, and the blue dots represent joints, dividing the core torso regions with the black dashed line.

3.2.1. Semantic Prior Edges Design for Common Features in Core Regions

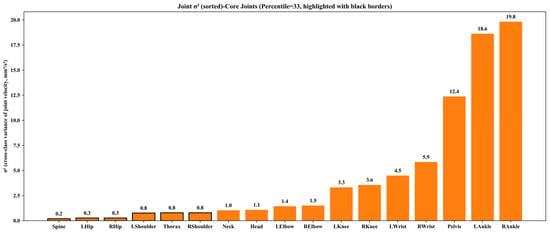

In multi-class complex human actions, core regions should avoid joints with excessive movement amplitude (e.g., lower limbs in Sitting (Sit) and upper limbs in Phoning (Pho), Appendix A), as these lack common features across actions. Instead, joints with moderate and consistent motion (square dashed line region in Figure 3) are selected, and their identification is supported by quantitative analysis using the cross-action joint velocity variance metric .

Figure 3.

Bar chart of cross-class joint velocity variance for 17 joints in the Human3.6M skeleton, sorted in ascending order . The y-axis represents the cross-class variance of joint velocity () with the unit of mm2/s2; the x-axis lists 17 joints of the Human3.6M skeleton. Joints highlighted with black borders are defined as “core-contributing joints”.

The calculation of follows four sequential formulas, forming a rigorous quantitative chain to measure joint motion stability across actions:

Single-sequence average joint velocity:

where is the sequence length, denotes the 3D coordinate of joint at frame , (dataset frame rate), and the result reflects the average motion speed of the joint in a single sequence.

Class-averaged joint velocity:

where is the set of sequences for action class , quantifying the typical motion speed of the joint within the class.

Global-averaged joint velocity:

where is the set of all 15 action classes, serving as the baseline for cross-action comparison.

Cross-action joint velocity variance:

As the core screening metric, a smaller indicates more stable motion patterns across actions. It should be noted that a lower does not imply higher task importance of a joint, but rather reflects greater motion consistency across heterogeneous action categories. Such stability is desirable for modeling common features shared among multiple actions.

Based on the 17-joint skeleton of the Human3.6M dataset, we calculated the cross-action velocity variance for each joint (see Figure 3) and ultimately determined the core joint set through statistical distribution analysis and kinematic function verification. By analyzing the overall distribution of cross-action velocity variance for all joints, we found that these variances do not change continuously or uniformly—instead, some joints exhibit significantly lower variance and thus possess stronger motion stability. While certain other joints also show relatively low variance, they are excluded from the core joint set due to mismatched functional positioning: the head and neck joints are connected to the torso via a single skeletal chain, functioning as distal joints. Their seemingly stable motion states are mainly derived from the passive constraints imposed by the torso, rather than actively participating in maintaining global pose stability, and therefore cannot meet the structural support requirements of the core region. As analyzed above, the core joints identified in this dataset consist of six members: Spine (), LHip (), RHip ), LShoulder (), Thorax (), and RShoulder () (highlighted with black borders in Figure 3).

From a kinematic and structural perspective, these six core joints are all located in the central torso, participate in multi-chain skeletal coupling, and serve as key hubs for force transmission and information propagation within the human skeleton graph. They jointly support the global pose structure, coordinate upper and lower limb movements, and are particularly suitable as the structural backbone for pose representation—laying a stable foundation for the subsequent design of semantic prior edges.

Based on comprehensive considerations of statistical motion stability, multi-chain skeletal coupling characteristics, and functional roles in pose coordination, the core region is formally defined as the set of these six torso joints, which together form a stable and semantically meaningful structural backbone.

Based on the above analysis, we summarize a general modeling principle: joints with low cross-action motion variance exhibit stable and shared motion patterns across actions and are therefore suitable for learning common representations, whereas joints with higher variance tend to encode action-specific or personalized characteristics and are treated as non-core regions.

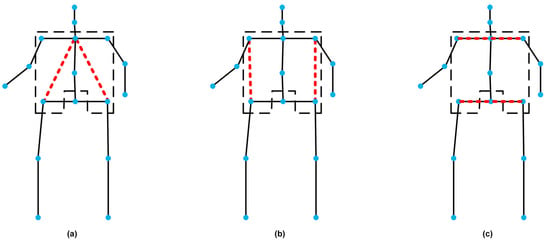

Combining quantitative screening and anatomical constraints, the core region consists of six joints: Spine, Thorax, LShoulder, RShoulder, LHip, RHip (Figure 4, black dashed box). Based on this, this study designed three different semantic prior edge schemes in the region (Figure 4), enhancing the common feature representation of the core region from different dimensions. These three schemes were optimized for two key dimensions: upper and lower limb information transmission and left–right side balance correlation. The first scheme is the “chest-hip” connection (Figure 4a), which simultaneously enhances vertical information transmission and horizontal balance correlation. Vertically, it improves the lengthy path of “chest–spine–hip” making information transmission more direct. Horizontally, it helps the left and right sides of the core regions better coordinate, thereby improving the overall balance correlation of the skeleton. The second scheme is the “shoulder–hip” connection (Figure 4b), which focuses on vertical enhancement by establishing a direct connection between the shoulder and hip, improving the lengthy path of “shoulder–chest–spine–hip” in the original topology and enhancing vertical information transmission. The third scheme is the “shoulder–shoulder” and “hip–hip” connection (Figure 4c), which focuses on horizontal enhancement by explicitly establishing bilateral symmetric connections, enhancing the balance correlation between left and right joints and improving the skeleton’s ability to represent human posture symmetry.

Figure 4.

Topological skeleton diagram of three semantic prior edges in core regions. The black solid line and the red dashed line respectively represent physical connections and semantic prior connections, and the blue dots represent joints, dividing the core torso regions with the black dashed. (a) represents the chest–hip connection; (b) represents the shoulder–hip connection; (c) represents the shoulder–shoulder connection combined with the hip–hip connection.

To verify the generality of this design approach, this study applied it to the HumanEva-I dataset. Following the same principle of cross-action motion stability, we identified a compact torso-centered core region in HumanEva-I and designed semantic prior edges within this region accordingly, rather than introducing dataset-specific heuristic connections. Following the common validation paradigm in related 3D human pose estimation (3D HPE) research [4,20,21], this study selected the Walk and Jog actions to validate cross-dataset effectiveness. We constructed a core region encompassing the head, shoulders, neck, and hips, and added a “head–hip” semantic connection to form a hybrid topology structure (Figure 5b), which strengthens the common feature representation capability of the core region in this dataset. At this point, this study has completed the design of semantic prior edges for the common features of core regions across the two datasets.

Figure 5.

Topological skeleton diagram of semantic prior edges in core regions of HumanEva-I dataset. The black dashed line box indicates the core regions. (a) represents original topological skeleton; (b) represents the head–hip connection. The black solid line and the red dashed line respectively represent physical connections and semantic prior connections, and the blue dots represent joints, dividing the core torso regions with the black dashed line.

3.2.2. Semantic Prior Edges Design for Personalized Features in Non-Core Regions

Introducing semantic prior edges to the common features of core regions enables better representation for the vast majority of action classes in the dataset. However, given the complexity of human actions in the dataset, a small subset of action classes still requires effective expression through the enhancement of personalized features in non-core regions. These personalized features typically exist between limb joints and serve to characterize long-range semantic dependencies among limb endpoints in complex actions of certain classes; such dependencies are particularly prominent only in a limited number of action classes; hence, we define them as personalized features of non-core regions. Therefore, the core goal of designing semantic prior edges for non-core regions is—on the basis of the common framework of core regions—to accurately strengthen the connections between key nodes carrying action-specific characteristics, realizing a two-layer representation structure of “common foundation + personalized differentiation”, and making up for the insufficient representation of fine action details by core regions.

When constructing semantic prior edges in non-core regions, we first excluded the lower limb ankle joints ((LAnkle , RAnkle )). The core reason is that their semantic relevance and feature value do not meet the selection criteria for key nodes in non-core regions, rather than a mere preference for action types. As shown in Figure 3, although the ankle joints exhibit extremely high cross-action velocity variance—far higher than other non-core joints, with distinct action-specific characteristics—an analysis from the perspective of semantic logic and representation requirements reveals significant shortcomings: the movement of ankle joints is mainly strongly bound to lower limb-dominated large-displacement actions (e.g., walking, jumping), and their variance contribution mostly stems from large-amplitude limb displacements rather than fine posture adjustments. In contrast, the core feature of upper limb functional actions (e.g., Phoning, Directions) lies precisely in fine, small-amplitude joint movements. Notably, Figure 3 shows RWrist has the highest cross-action velocity variance ) among all upper limb non-core joints. This means it undertakes the most delicate detail changes in actions, such as rotational pointing in Directions and stable device-holding in Phoning, serving as a key carrier of action-specific details for upper limb movements, which perfectly aligns with the design goal of “enhancing personalized features in non-core regions”. In comparison, the left wrist (LWrist) exhibits significantly smaller variations across different actions (), indicating its limited fine-tuning range and much lower ability to capture action-specific details than the right wrist. Therefore, it does not meet the selection criteria for key nodes in non-core regions.

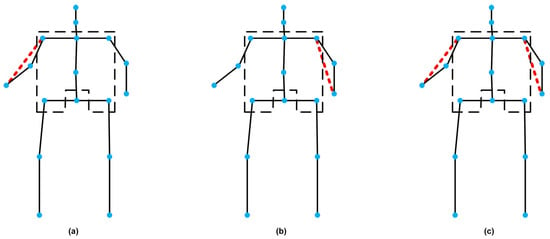

This study designs three personalized semantic prior edge schemes (Figure 6), establishing coordination relationships between upper limb joints for specific actions, enabling the model to better capture cross-joint long-range semantic dependencies in specific actions. The first scheme is the “right shoulder–right wrist” connection (Figure 6a), primarily designed to establish direct information transmission paths for action classes with larger upper limb movement ranges. The second scheme is the “left shoulder–left wrist” connection (Figure 6b), used to verify whether such connections can bring the same effect on the left side, where the action performance is less significant. The scheme is intended to validate the rationality of the first scheme’s design through comparative experiments. The third scheme introduces both bilateral “shoulder–wrist” connections simultaneously (Figure 6c), focusing on introducing bilateral symmetry to evaluate its impact on pose representation capability. The third scheme aims to validate the rationality of the first scheme’s design through comparative experiments with the first two schemes.

Figure 6.

Personalized “shoulder–wrist” semantic prior edge topological skeleton. The black solid line and the red dashed line respectively represent physical connections and semantic prior connections, and the blue dots represent joints, dividing the core torso regions with the black dashed. (a) represents the right shoulder–right wrist connection; (b) represents the left shoulder–left wrist connection; (c) represents the both bilateral shoulder–wrist connections.

The design of personalized semantic prior edges in non-core regions is not independent of core regions, but forms a complementary synergy of “commonality-personalization” with them: the torso joints in core regions provide a stable benchmark for global posture, ensuring the consistency of basic representation across different actions, while the personalized shoulder–wrist connections in non-core regions focus on action-specific details, enabling accurate differentiation of similar actions. This two-layer design not only avoids the “over-generalization” of fine actions by the common representation of core regions but also solves the “representation confusion” of high-variance joints in non-core regions, laying a solid foundation for the subsequent performance improvement of the model in 3D HPE tasks.

3.3. Formalization of the Hybrid Topology

This section formalizes the construction process of the hybrid graph topology, which is realized by integrating predefined semantic prior edges into the physical skeletal structure. Notably, all adjustments are confined solely to the edge set level of the input graph—no modifications are made to any model parameters or the core logic of adjacency matrix generation. The physical skeletal edge set is derived from the anatomical parent–child joint relationships of the target human skeleton, defined as where denotes the total number of joints in the skeleton, and indicates the root joint (e.g., pelvis), which is excluded to retain only valid anatomical connections. The semantic prior edge set consists of a small set of manually predefined long-range edges; these edges are designed to capture kinematically meaningful associations between non-anatomically connected joints, and there is no overlap between and to avoid redundant connections. The final hybrid edge set is obtained by taking the union of the above two sets:

This union operation represents the only modification to the input graph structure; except for the baseline-consistent static joint removal and correction performed during dataset initialization, no adjustments are made to any edge weights or joint parent relationships. The hybrid topological adjacency matrix is generated by a fixed, parameter-free adjacency construction operator —a function that maps an edge set to its corresponding undirected binary adjacency matrix—formalized as:

Specifically, the operator follows two core rules: first, it treats all edges as undirected, meaning if , both entries and are set to 1; second, it adopts binary value assignment, where if and only if there exists a connection between joint and in , and otherwise. Critically, introduces no learnable parameters, edge-specific scaling factors, or adaptive adjustments—it adheres strictly to the same generation logic as the baseline model to ensure fair comparability. It is important to emphasize that all topological enhancement operations are limited to the construction stage of the input edge set (preprocessing stage), rather than the model architecture or computational logic level. While preserving the complexity of the baseline model, this design maintains the sparsity of , avoiding additional computational overhead caused by dense graph structures.

3.4. Summary

This chapter proposes a semantic prior-based non-Euclidean topology enhancement method for multi-class complex human actions. Its core goal is to explicitly enhance the topological structure of the input skeleton, thereby improving the ability of GCN–Transformer fusion models to model cross-joint long-range semantic dependencies. Taking the KTPFormer as the baseline model, the method introduces a semantic prior-driven hybrid topology design, systematically adding long-range connections that can characterize action semantics while retaining the original physical connections. Based on the cross-class stability of joint motions, this design divides the skeleton into core regions and non-core regions, and designs semantic prior edges respectively to enhance the representation of common features and personalized features. The entire enhancement process is achieved by merging the physical edge set and the semantic edge set, formally manifested as the preprocessing optimization of the input adjacency matrix. This process does not introduce any additional learnable parameters, and while maintaining the original complexity of the model, it realizes the structured embedding of action semantics, thus providing a more information-rich and discriminative graph structure input for subsequent pose estimation.

4. Results and Discussion

To scientifically evaluate the performance of the proposed methods, this paper conducts detailed ablation studies and comparative experiments on the KTPFormer framework.

4.1. Datasets

The Human3.6M dataset contains 3.6 million video frames of eleven subjects, with seven of them annotated with 3D poses [22]. Each subject performs 15 actions. These actions were recorded by four synchronized cameras at a frequency of 50 Hz. This study uses a 17-joint skeleton and trains on five subjects (S1, S5, S6, S7, S8) and tests on two subjects (S9 and S11).

To verify the rationality of introducing semantic prior edges, this study also validates on the Walk and Jog actions of the HumanEva-I dataset in addition to using the Human3.6M dataset [23]. HumanEva-I is a smaller dataset containing six predefined actions performed by four subjects, with each action repeated three times. Furthermore, this dataset also includes seven calibrated synchronized video sequences (four grayscale image sequences and three color image sequences), which are synchronized with 3D body poses obtained from a motion capture system. According to relevant research, this study also selected three subjects to evaluate the two actions of Walk and Jog [4].

4.2. Evaluation Metrics

When evaluating the model results, to ensure fair comparisons with baseline models and other relevant research findings, this experiment employs two widely used evaluation metrics [24].

MPJPE (Mean Per Joint Position Error): Measures the Euclidean distance between predicted joints and ground-truth joints, with units in millimeters. The specific calculation formula is as follows

where is the number of joints, is the number of frames, is the real position of the joint in the frame , and is the predicted position of the joint in the frame . The lower the value of MPJPE, the closer the predicted pose is to the real pose.

P-MPJPE (Procrustes-aligned Mean Per Joint Position Error): Before calculating the error, rigid alignment (rotation and translation) is performed on the predicted pose and the ground truth pose, and then the Euclidean distance is calculated. The specific calculation formula is shown as

where is the number of joints, is the predicted joint position after alignment, is the corresponding ground truth joint position, is the optimal rotation matrix, and is the translation vector. A smaller P-MPJPE indicates that the predicted joint positions are closer to the ground truth joint positions under optimal alignment conditions.

4.3. Comparative Experiment on Semantic Prior Edge Design Schemes

4.3.1. Experimental Results of Different Semantic Prior Edge Design Schemes in the Core Regions

To study the optimal semantic prior edge design scheme for core regions, this paper compares three semantic prior edge design schemes for core regions on the Human3.6M dataset: the “chest–hip” connection, the “shoulder–hip” connection, and the “shoulder–shoulder, hip–hip” connection scheme. The experimental results of different design schemes are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Experimental results of different semantic prior edge design schemes in core regions.

The experimental results show that among the semantic prior edge design schemes in three core regions, the “chest–hip” semantic prior edge design reduced the MPJPE index from 40.1 mm to 39.9 mm. The other two design schemes did not produce significant improvements in the index.

Adding the “chest–hip” semantic prior edge in the core regions, MPJPE was reduced by 0.2 mm compared to the baseline model. This result validates the design concept in Section 3.2.1, that the “chest–hip” semantic prior edge not only enhances the information representation of “chest–spine–hip” but also strengthens the longitudinal and lateral information transfer, thereby effectively optimizing the representation of common features in the core regions. The experimental results of the second design scheme show that the “shoulder–hip” semantic prior edge design, which focuses on longitudinal optimization, did not improve model performance. The reason is that this semantic prior edge design only provides a single longitudinal information pathway and lacks lateral information transfer, limiting the ability to represent the overall common features of the core regions. The experimental results of the third design scheme show that the introduction of “shoulder–shoulder, hip–hip” connections led to the deterioration of the MPJPE metric. This indicates that the features represented by the semantic prior edges in the third design scheme weaken the original skeleton features and fail to provide effective new features, interfering with the model’s learning of the original skeleton features. Therefore, in the Human3.6M dataset, the effectiveness of the semantic prior edge design for the core regions highly depends on the ability to represent the “twisting” features of the torso in multi-class complex human actions.

4.3.2. Experimental Results and Discussion of Different Semantic Prior Edge Design Schemes for Non-Core Regions

To further improve model performance and complement the feature representation capability of the optimal semantic edge design scheme for core regions, this paper proposes three non-core regions semantic prior edge schemes based on the Human3.6M dataset. The experiments compare the three design schemes: “right shoulder–right wrist” connection, “left shoulder–left wrist” connection, and the combined scheme. The experimental results are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Experimental results of different semantic prior edge design schemes in non-core regions.

The experimental results show that among the three upper limb connection schemes, the “right shoulder–right wrist” semantic prior edge design achieves the best MPJPE metric (40.0 mm), while the other two schemes did not bring performance improvement. The main reason for the small performance improvement of the model is that this design is a supplement to the optimal semantic prior edge design scheme for the core regions, only enhancing the feature representation of some actions in the dataset. For example, for the two upper limb actions with large amplitude in the dataset, Phoning (Pho) and Directions (Dir), this design establishes a “right shoulder–right wrist” information pathway, effectively enhancing the ability of the input skeleton graph to represent the functional coupling between upper limb joints, thereby verifying the design idea in Section 3.2.2. However, the addition of the “left shoulder–left wrist” connection actually led to performance degradation (MPJPE increased to 40.2 mm), indicating that introducing additional connections without actual semantic support creates structural redundancy, and the coupled topology structure weakens the original bone features to some extent. When adding bilateral “shoulder–wrist” connections, the performance matches the baseline model, indicating that a simple symmetric design cannot improve feature representation for the Pho and Dir action classes. Instead, it weakens the feature representation capability of the original skeleton on one side, which cancels out the effect of enhancing one side through semantic prior edges.

4.4. Results and Discussion of Semantic Prior Edge Ablation Experiments

To verify the effectiveness and universality of the non-Euclidean topology enhancement method based on semantic priors proposed in this paper, Section 4.4 systematically conducted experiments and evaluations using the KTPFormer model on the Human3.6M and HumanEva-I datasets, respectively. The performance of ablation experiments on different datasets can verify the universality of the semantic prior edge design method and its effectiveness under different datasets. Comparative experiments on different semantic prior edge design schemes for core and non-core regions can be used to verify the optimal topology enhancement scheme.

4.4.1. Ablation Experiment Result and Discussion Based on the HumanEva-I Dataset

This experiment uses KTPFormer as the baseline model to verify the effectiveness and universality of the semantic prior edge design method. Based on the original skeleton data from the HumanEva-I dataset, the experiment establishes “head–hip” semantic prior edge connections and evaluates the model on the Walk and Jog action classes.

The ablation experiment results in Table 3 on the HumanEva-I dataset show that after adding “head–hip” semantic prior edges to the core regions (Figure 4), the model’s average MPJPE on Walk and Jog actions decreased from 18.3 mm to 17.1 mm, an improvement of 6.5%. The model achieved better performance on both action classes for all subjects (S1, S2, S3), demonstrating the generalization capability of this method. Additionally, the improvement in Jog actions was slightly higher than in Walk actions. This indicates that the proposed method has better feature extraction capability for actions with larger skeletal motion amplitudes in the core regions. Further analysis reveals that after adding the “head–hip” connection, the MPJPE for subject S1 on Jog actions decreased by 3 mm compared to the original skeleton, which is significantly greater than the metric changes for other subjects in both action classes. The reason may be that the joint motion amplitude in the core regions during S1’s Jog actions was larger than that of other subjects, making the effect of enhancing core regions features more pronounced than for other subjects in these two actions.

Table 3.

Ablation experiment result of “head–hip” semantic prior edges based on the HumanEva-I dataset.

4.4.2. Ablation Experiments and Discussions Based on the Human3.6M Dataset

To further validate the effectiveness and universality of the semantic prior edge design method proposed in this study on multi-class complex human action data, we conducted semantic prior edge ablation experiments on the larger-scale Human3.6M dataset. The ablation experiments verified the “chest–hip” semantic prior edge design that represents common features in core regions, the “right shoulder–right wrist” semantic prior edge design that represents personalized features in non-core regions, as well as the design that simultaneously represents both common and personalized features. The experimental results are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Ablation experiment results of KTPFormer with semantic prior edges on the Human3.6M dataset.

The results show that using the “chest–hip” semantic prior edge reduces MPJPE from the baseline of 40.1 mm to 39.9 mm, demonstrating a significant performance improvement. Using the “right shoulder–right wrist” semantic prior edge reduces MPJPE from the baseline of 40.1 mm to 40.0 mm, resulting in only a slight performance improvement. Meanwhile, the design that simultaneously represents both common and personalized features achieves the best result, reducing MPJPE from the baseline of 40.1 mm to 39.6 mm. Notably, while MPJPE improved, P-MPJPE also showed an overall positive trend, with the combined design reducing P-MPJPE to 31.7 mm.

After individually introducing the “chest–hip” semantic prior edge and the “right shoulder–right wrist” semantic prior edge, the model’s MPJPE metric was slightly lower than on the original skeleton data. This indicates that individually enhancing the representation of common features in core regions and individually enhancing the representation of personalized features in non-core regions both provide slight performance improvements to the baseline model. However, given the complexity of features in multi-class complex human motion data, the model’s performance is difficult to significantly improve through individually enhanced common or personalized features. The semantic prior edge design in the core region can enhance feature representation for most action classes, but the motion amplitude in the core region is small, resulting in limited overall contribution to feature representation across different human action classes. Therefore, this research also considered enhancing personalized features in non-core regions in the semantic prior edge design. Conversely, although the semantic prior edge design for non-core regions can only enhance feature representation for a few action classes, the range of motion in non-core regions is large, making their contribution to feature representation across different human action classes non-negligible. Experimental results also show that the semantic prior edge design that simultaneously represents both common and personalized features significantly reduces the overall MPJPE metric of the dataset and is far superior to designs that individually introduce semantic prior edges representing either common or personalized features.

It should be additionally noted that since the semantic prior edge design proposed in this paper improves model performance by optimizing the skeleton topology structure, it does not increase the number of model parameters (as shown in Table 4).

The experimental results show that while maintaining the physical connections of the human skeleton, it is necessary to enhance the representation of common features in core regions and personalized features in non-core regions to significantly improve the performance of the baseline model on multi-class complex human action data without increasing the number of parameters.

4.4.3. Training Stability and Statistical Analysis on Human3.6M

To verify that the performance gain of adding semantic prior edges is statistically reliable rather than a result of natural fluctuations during training, we performed a comprehensive stability and significance analysis, including multiple independent runs, variance estimation, statistical tests, and training convergence visualization.

The standard deviation across independent runs is extremely small, which confirms that both the baseline KTPFormer model and the KTPFormer model with added semantic prior edges exhibit high stability and low randomness during the training process, with the inherent random fluctuation kept at a negligible level that is far smaller than the observed performance gain.

Importantly, our method consistently outperforms the baseline in all five runs, with a mean improvement of 0.5 mm, which is significantly larger than the natural variance range.

To validate whether the observed performance gain of our KTPFormer model with added semantic prior edges is statistically meaningful (rather than a result of random training fluctuations), we conducted an independent samples t-test on the MPJPE results of the baseline model and our method. This test was chosen because the baseline model and our model with semantic prior edges were run independently (with no one-to-one matching of experimental conditions across individual runs), making the two groups of data statistically independent. The experimental data for the test are derived from five independent runs of each model (Table 5): baseline group: [40.2, 40.1, 40.1, 40.1, 40.1] (MPJPE, mm); our method group: [39.6, 39.7, 39.6, 39.6, 39.7] (MPJPE, mm). Performed on the real experimental outputs of the models, the test yields the following results:

Table 5.

MPJPE Results (Mean ± Std) on Human3.6M.

The resulting p-value (0.0004) is far below the conventional 0.05 significance threshold and even the stricter 0.001 threshold, indicating that the performance improvement of our method is statistically significant at the 0.1% level; this confirms that the 0.5 mm mean performance gain of our model over the baseline is not attributable to random variation in the training process, and such a high level of statistical significance strongly supports the effectiveness of adding semantic prior edges to the KTPFormer framework, aligning with the methodological consensus in the field of 3D human pose estimation for validating reliable performance improvements.

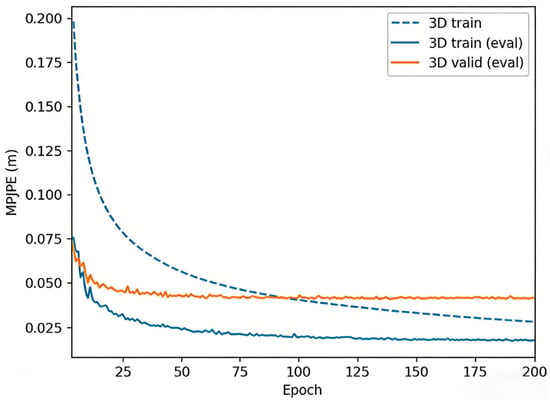

Figure 7 shows the training loss, 3D train MPJPE, and valid MPJPE (on S9 and S11) across 200 epochs for our model with added semantic prior edges—all curves descend smoothly and plateau, indicating stable convergence on unseen data. After ~epoch 50, the valid MPJPE fluctuates within 1 mm, reflecting low optimization noise, and the small train-valid gap throughout training rules out overfitting.

Figure 7.

Training and Test Set MPJPE Convergence Curves of the Semantic Prior Edge Enhanced Model.

4.4.4. Mechanism Analysis

To gain a deeper understanding of the mechanism by which semantic prior edges (thorax–hip edges: Thorax–RHip, Thorax–LHip; right shoulder–right wrist edge: RShoulder–RWrist) enhance model performance, this section conducts an analysis by integrating attention heatmaps and edge weight distribution maps. A key finding is that semantic prior edges explicitly modify the topological structure of the input graph, guiding the model’s attention to focus more on semantically relevant distant joint pairs, thereby enabling efficient capture of long-range semantic dependencies—which is the core reason for the reduction in the model’s pose estimation errors (MPJPE/P-MPJPE)—rather than increasing model parameters.

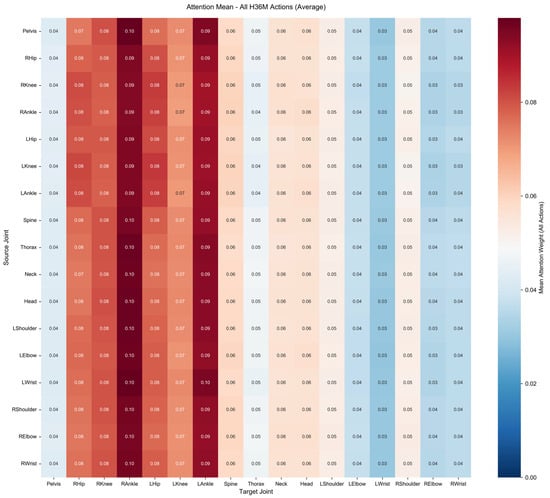

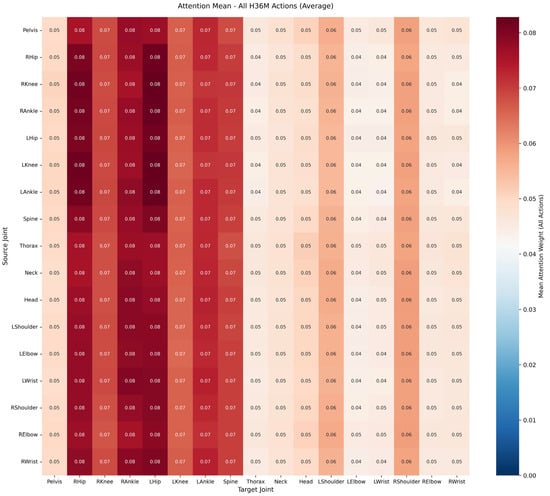

To intuitively reflect the attention allocation limitation of the baseline model, Figure 8 presents the attention weight heatmap of the original KTPFormer model. Analysis shows that, constrained by the original physical skeleton, the attention of the baseline model struggles to effectively associate non-directly connected joint pairs such as “Thorax–Hip” and “Right Shoulder–Right Wrist”—the attention weights of these joint pairs in Figure 8 are significantly lower than those of adjacent physical joints (e.g., shoulder–elbow, hip–knee).

Figure 8.

KTPFormer Model Attention Weight Heatmap. Source joint: Row dimension of the heatmap. Each row represents one joint that actively allocates attention weights to all other joints. Target joint: Column dimension of the heatmap. Each column represents one joint that receives attention weights from all other joints. Color intensity indicates the attention weight value, with higher intensity representing a stronger attention correlation between the source and target joints.

After introducing the semantic prior edges, the attention allocation of the model is significantly optimized, as shown in Figure 9 (Attention Weight Heatmap of the Semantic Prior-Enhanced KTPFormer Model). These corresponding joint pairs (“Thorax–Hip” and “Right Shoulder–Right Wrist”) exhibit a significantly enhanced response in the attention heatmap, forming specific high-attention regions. This confirms that the newly added semantic prior edges provide critical topological guidance for the model, enabling it to actively focus on semantically relevant long-range joint pairs.

Figure 9.

Semantic Prior Edges Enhanced KTPFormer Model Attention Weight Heatmap. Source joint: Row dimension of the heatmap. Each row represents one joint that actively allocates attention weights to all other joints. Target joint: Column dimension of the heatmap. Each column represents one joint that receives attention weights from all other joints. Color intensity indicates the attention weight value, with higher intensity representing a stronger attention correlation between the source and target joints.

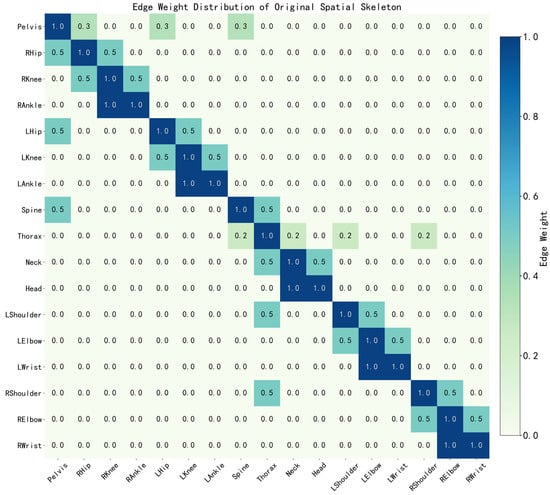

To further verify the structural change brought by semantic prior edges, Figure 10 presents the Edge Weight Distribution Heatmap of the Original Spatial Skeleton. It can be observed that the edge weights of the original skeleton are only concentrated on physical connections (e.g., shoulder–elbow, hip–knee), while non-adjacent joints (such as Thorax–RHip, RShoulder–RWrist) show zero edge weights, indicating no direct topological connection. This structural limitation leads to the baseline model’s inability to capture long-range semantic dependencies.

Figure 10.

Edge Weight Distribution Heatmap of Original Spatial Skeleton. Color intensity indicates the edge weight value, with higher intensity representing a stronger connection relevance between joints.

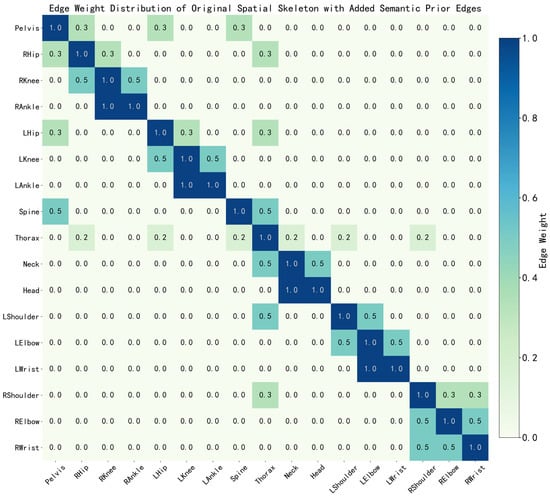

In contrast, Figure 11 (Edge Weight Distribution Heatmap of the Spatial Skeleton with Added Semantic Prior Edges) intuitively demonstrates the structural enhancement: the semantic prior edges (Thorax–RHip, Thorax–LHip, RShoulder–RWrist) are introduced as explicit non-zero weight connections in the hybrid adjacency matrix ()) defined in Section 3.3. These new edges provide direct pathways for modeling long-range dependencies, enabling the model to directly transmit semantic information between non-adjacent joints without relying on indirect physical connections.

Figure 11.

Edge Weight Distribution Heatmap of Spatial Skeleton with Added Semantic Prior Edges. Color intensity indicates the edge weight value, with higher intensity representing a stronger connection relevance between joints.

This improvement stems from topological enhancement at the input representation level, rather than the expansion of model capacity. In summary, the visualization analysis of Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11 forms a complete explanatory chain from “structural change (Figure 10 vs. Figure 11)” to “attention response (Figure 8 vs. Figure 9)”, providing direct mechanistic evidence for the non-Euclidean topology enhancement method proposed in this paper.

4.5. Comparative Results and Discussion

4.5.1. Comparison Experiments and Discussions Based on Random Edges

This paper further validates the scientificity and rationality of the semantic prior edge design proposed in this study through random edge comparison experiments. While maintaining the original physical connections of the human skeleton, this experiment introduces two sets of randomly generated undirected edges in the Human3.6M dataset. Each set contains three undirected edges randomly selected from all non-physical connected joint pairs, with the number of randomly selected undirected edges in each set consistent with the number of semantic prior edges in this design. The experiment compares the addition of Random Edges 1, Random Edges 2, and the semantic prior edge design proposed in this paper, which can represent common and personalized features. The experimental results are shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Experimental results of random edges on Human3.6M.

The experimental results show that compared to the baseline model, the introduction of random edges does not bring reliable performance improvements. Random Edges 1 increased MPJPE to 40.2 mm, while Random Edges 2 slightly decreased MPJPE to 40.0 mm but increased P-MPJPE to 32.1 mm. In contrast, the semantic prior edge design proposed in this paper achieved the best overall performance (MPJPE: 39.6 mm, P-MPJPE: 31.7 mm).

Random edge comparison experiments further validate the necessity of semantic prior edge design. Experimental results show that simply increasing the number of connections does not guarantee performance improvement, indicating that the performance enhancement is not due to the increase in connection quantity but rather the rationality of the connections. In contrast, the semantic prior edge design is based on the analysis of human motion patterns and action features in the dataset, modeling long-range semantic functional associations across joints. This result aligns with the design logic in Section 3.2, indicating that only connections designed based on reasonable prior knowledge can provide valuable supplementary information to the model, thereby enhancing the skeleton’s representation capability for human poses.

4.5.2. Comparison Results and Discussion with Other Models’ Performance

To demonstrate that the method proposed in this paper outperforms existing SOTA models and other mainstream models, this experiment compared the KTPFormer model with semantic edge design against mainstream models on the Human3.6M dataset. The comparison experiment results are shown in Table 7. Additionally, Table 7 provides a more comprehensive evaluation of the proposed method by showing the performance metrics of each model on subclass actions in the Human3.6M dataset.

Table 7.

Quantitative comparison results of MPJPE and P-MPJPE with other models on Human3.6M.

The experimental results in Table 7 show that the method proposed in this paper achieves 39.6 mm on the MPJPE metric based on the KTPFormer, which is not only significantly lower than the GLA-GCN (44.4 mm) and STCFormer (40.5 mm), but also lower than the baseline KTPFormer (40.1 mm). Furthermore, the P-MPJPE metric of 31.7 mm obtained by the proposed method is also the lowest among all models.

From the analysis of results across different action classes, the method proposed in this paper shows more significant performance improvements on complex human actions such as Sit Down (SitD), Photo, Walk Dog (WalkD), and Smoking (Smok) by considering the extraction of personalized features within certain action classes, with MPJPE reduced to 54.5 mm, 47.3 mm, 39 mm, and 40.9 mm, respectively. This indicates that while the proposed method reduces overall MPJPE by enhancing common feature representation, it can further decrease MPJPE for action classes with larger limb movements by strengthening personalized feature representation. The method proposed in this paper, which constructs a non-Euclidean topology capable of balancing common and personalized feature representation, effectively improves the model’s pose estimation capability for multi-class complex human actions.

4.6. Summary

Based on the non-Euclidean topology enhancement method with semantic priors proposed in Section 3, this paper conducts systematic ablation and comparative experiments on the Human3.6M and HumanEva-I datasets to comprehensively evaluate the model’s performance. On the HumanEva-I dataset, the model’s MPJPE metric decreased by approximately 6.5%, verifying the capability of the proposed method to model common features in core regions. On the Human3.6M dataset, experimental results for different semantic prior edge design schemes show a 1.25% reduction in MPJPE, demonstrating that the proposed semantic prior edge design method, which equally emphasizes common features in core regions and personalized features in non-core regions, can significantly improve model performance on multi-class complex human motion datasets. Additionally, random edge comparison experiments confirm that the performance improvement stems from the rationality and scientific nature of the semantic prior edge design rather than a simple increase in cross-joint connections. Comparison results with other mainstream models show that this method achieves the lowest MPJPE (39.6 mm) and P-MPJPE (31.7 mm) on Human3.6M, representing a 1.25% and 0.63% decrease, respectively, compared to the baseline KTPFormer, achieving stable performance improvement without increasing model parameters.

In summary, the experimental results in Section 4 verify that the proposed method further improves upon the existing best GCN–Transformer fusion model for human pose estimation on multi-class complex human action datasets.

5. Conclusions

This paper proposes a semantic prior-based non-Euclidean topology enhancement method to address the modeling challenges of multi-class complex human actions. This method designs semantic prior edges from two aspects: enhancement of common features and enhancement of personalized features, to optimize the representation capability of skeleton graphs. The two types of complementary semantic edges enhance the common features of the core regions of human skeletons in most action classes, while also enhancing the personalized features of non-core regions in action classes with larger limb movement amplitudes. The optimized hybrid topology structure enables the fusion model to better capture cross-joint semantic dependencies and improve the modeling capability for multi-class complex human actions.

In implementation, this method uses KTPFormer as the baseline model to construct a graph topology that combines both anatomical plausibility and semantic consistency. Since the proposed method only modifies the initial adjacency matrix, it achieves performance surpassing the state-of-the-art on multi-class complex human action datasets without increasing the model’s parameter count.

Currently, the design of semantic prior edges has notable limitations: it involves a certain degree of manual analysis and subjective judgment; has not yet been fully automated; and the static, human-prior-based topological structure may fail to adaptively achieve optimal performance for novel scenarios with action patterns significantly different from the training set or semantically ambiguous action categories. Nevertheless, by relying on quantitative and kinematic analysis of multi-class complex actions within specific datasets (e.g., Human3.6M), this design effectively ensures the interpretability of the semantic prior edges—a key advantage in structured tasks like 3D human pose estimation.

Looking ahead, this research can be further advanced in the following aspects:

- Explore using mathematical theories to quantify the feature enhancement effects of semantic prior edges across different types of human actions, reducing reliance on manual priors to further examine the method’s applicability across different datasets;

- Extend this hybrid topology modeling method to other pose estimation tasks based on skeletal data to verify its generalization capability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.F. and X.H.; methodology, C.F. and X.H.; validation, C.F.; investigation, C.F.; resources, C.F.; data curation, C.F. and X.H.; writing—original draft preparation, C.F., X.H. and Y.F.; writing—review and editing, W.S., X.H., C.F., Y.F. and G.Y.; visualization, C.F. and X.H.; supervision, X.H. and G.Y.; project administration, X.H. and G.Y.; funding acquisition, X.H. and G.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by Heilongjiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (No. PL2024F004). This work is also supported by the 2025 Heilongjiang Provincial Postdoctoral Research Startup Foundation (188004).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The Heilongjiang Provincial Key Laboratory of Electronic Commerce and Information Processing and Postdoctoral Research Workstation of Northeast Asia Service Outsourcing Research Center provided academic support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 3D HPE | 3D Human Pose Estimation |

| GCN | Graph Convolutional Network |

| MPJPE | Mean Per Joint Position Error |

| P-MPJPE | Procrustes-Aligned Mean Per Joint Position Error |

| CPN | Cascaded Pyramid Network |

| MHSA | Multi-Head Self-Attention |

| KPA | Kinematics Prior Attention |

| TPA | Trajectory Prior Attention |

| SOTA | State-of-the-Art |

Appendix A

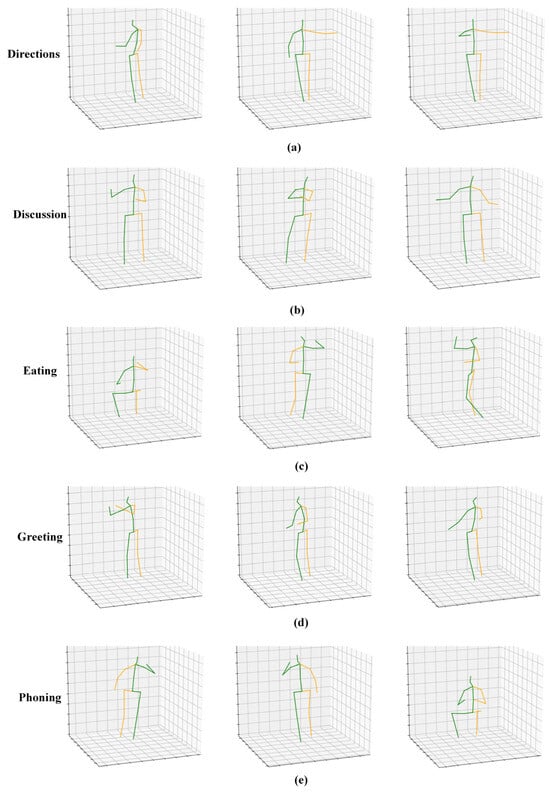

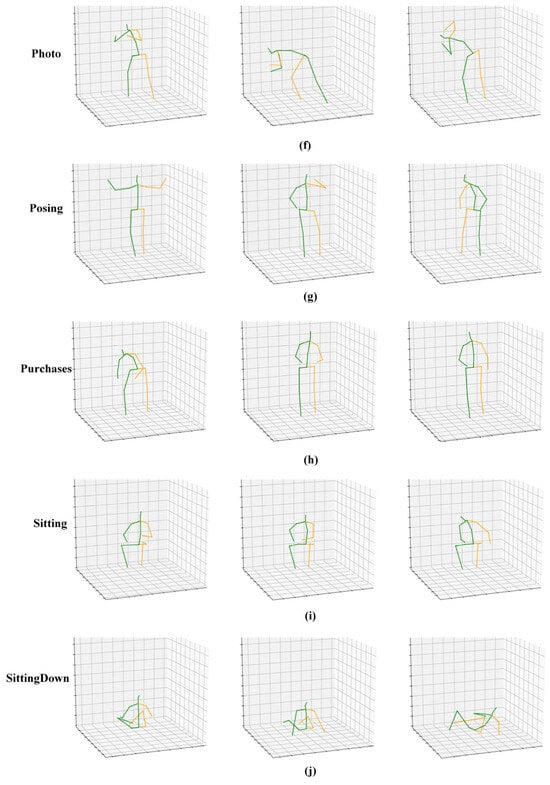

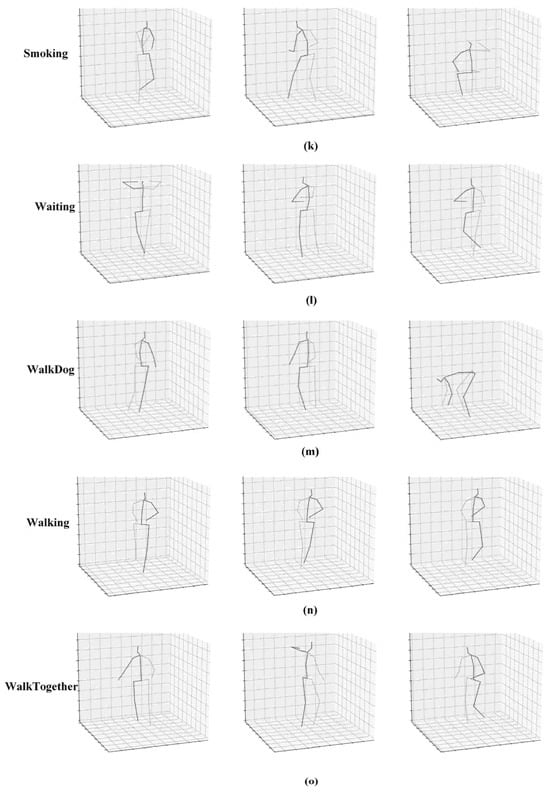

This appendix elaborates on the design basis for the semantic prior edges proposed in Section 3.2. All visualizations in Figure A1 are intended solely to provide qualitative intuition for cross-joint semantic interactions observed across action classes, rather than to serve as a quantitative selection mechanism for semantic prior edges. The design is not merely observational; it is derived from systematic analysis and discussion of 15 action classes in the Human3.6M dataset.

Figure A1.

Human3.6M dataset motion skeleton graphs for 15 action classes. The green lines represent the left half of the body, and the orange lines represent the right half of the body. (a) Corresponds to the “Directions” action; (b) Corresponds to the “Discussion” action; (c) Corresponds to the “Eating” action; (d) Corresponds to the “Greeting” action; (e) Corresponds to the “Phoning” action; (f) Corresponds to the “Photo” action; (g) Corresponds to the “Posing” action; (h) Corresponds to the “Purchases” action; (i) Corresponds to the “Sitting” action; (j) Corresponds to the “SittingDown” action; (k) Corresponds to the “Smoking” action; (l) Corresponds to the “Waiting” action; (m) Corresponds to the “WalkDog” action; (n) Corresponds to the “Walking” action; (o) Corresponds to the “WalkTogether” action.

References

- Yan, S.; Xiong, Y.; Lin, D. Spatial temporal graph convolutional networks for skeleton-based action recognition. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, New Orleans, LA, USA, 2–7 February 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hagbi, N.; Bergig, O.; El-Sana, J.; Billinghurst, M. Shape recognition and pose estimation for mobile augmented reality. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2010, 17, 1369–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svenstrup, M.; Tranberg, S.; Andersen, H.J.; Bak, T. Pose estimation and adaptive robot behaviour for human-robot interaction. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Kobe, Japan, 12–17 May 2009; pp. 3571–3576. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, J.; Zhou, Y.; Mok, P. Ktpformer: Kinematics and trajectory prior knowledge-enhanced transformer for 3d human pose estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 1123–1132. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.-H.; Ramanan, D. 3d human pose estimation = 2d pose estimation+ matching. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 7035–7043. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Zhang, W.; Chan, A.B. Maximum-margin structured learning with deep networks for 3d human pose estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Santiago, Chile, 7–13 December 2015; pp. 2848–2856. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, C.; Zhu, S.; Mendieta, M.; Yang, T.; Chen, C.; Ding, Z. 3d human pose estimation with spatial and temporal transformers. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Virtual, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 11656–11665. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, W.; Tian, Y.; Ye, Q.; Jiao, J.; Wang, W. Graformer: Graph convolution transformer for 3d pose estimation. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2109.08364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1706.03762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Zheng, C.; Liu, M.; Wang, P.; Chen, C. Poseformerv2: Exploring frequency domain for efficient and robust 3d human pose estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023; pp. 8877–8886. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Tu, Z.; Yang, J.; Chen, Y.; Yuan, J. Mixste: Seq2seq mixed spatio-temporal encoder for 3d human pose estimation in video. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 13232–13242. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Z.; Qiu, Z.; Hao, Y.; Hong, R.; Yao, T. 3d human pose estimation with spatio-temporal criss-cross attention. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023; pp. 4790–4799. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L.; Peng, X.; Tian, Y.; Kapadia, M.; Metaxas, D.N. Semantic graph convolutional networks for 3d human pose regression. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 3425–3435. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Du, R.; Chen, S. Semantic–structural graph convolutional networks for whole-body human pose estimation. Information 2022, 13, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Yuan, C.; Li, B.; Deng, Y.; Hu, W. Channel-wise topology refinement graph convolution for skeleton-based action recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Virtual, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 13359–13368. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, H.; Li, Z.; Zhang, D.; He, S.; Tang, J. Divide-and-conquer: Confluent triple-flow network for RGB-T salient object detection. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2024, 47, 1958–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, W.; Wang, W.; Tian, Y. Graformer: Graph-oriented transformer for 3d pose estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 20438–20447. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Dai, J.; Bai, J.; Pan, J. DGFormer: Dynamic graph transformer for 3D human pose estimation. Pattern Recognit. 2024, 152, 110446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, Z.; Hamza, A.B. Multi-hop graph transformer network for 3D human pose estimation. J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent. 2024, 101, 104174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.X.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhong, S.-h.; Liu, Y.; Chen, C.W. Gla-gcn: Global-local adaptive graph convolutional network for 3d human pose estimation from monocular video. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 2–6 October 2023; pp. 8818–8829. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, H.; Xu, S.; Su, C. MSTFormer: Multi-granularity spatial-temporal transformers for 3D human pose estimation. J. King Saud Univ. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2025, 37, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionescu, C.; Papava, D.; Olaru, V.; Sminchisescu, C. Human3. 6m: Large scale datasets and predictive methods for 3d human sensing in natural environments. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2013, 36, 1325–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sigal, L.; Balan, A.O.; Black, M.J. Humaneva: Synchronized video and motion capture dataset and baseline algorithm for evaluation of articulated human motion. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2010, 87, 4–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavllo, D.; Feichtenhofer, C.; Grangier, D.; Auli, M. 3d human pose estimation in video with temporal convolutions and semi-supervised training. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 7753–7762. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, Z.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, G.; Sun, J. Cascaded Pyramid Network for Multi-Person Pose Estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, K.; Lu, F.; Lv, Y.; Zhang, L.; Guo, C.; Wu, J. 3d human pose estimation via non-causal retentive networks. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; pp. 111–128. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Chen, G.; Xue, Y. 3D Human Pose Estimation Transformer based on Spatio-Temporal Augmentation. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Computational Intelligence, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 14–16 February 2025; pp. 164–169. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.